Abstract

Background

Bloodstream infections are linked to heightened morbidity and mortality rates. The consequences of delayed antibiotic treatment can be detrimental. Effective management of bacteraemia hinges on rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Objectives

This retrospective study examined the influence of the VITEK® REVEAL™ Rapid AST system on positive blood culture (PBC) management in a French tertiary hospital.

Materials and methods

Between November 2021 and March 2022, 79 Gram-negative monomicrobial PBC cases underwent testing with both VITEK®REVEAL™ and VITEK®2 systems.

Results

The study found that VITEK®REVEAL™ yielded better results than the standard of care, significantly shortening the time to result (7.0 h compared to 9.6 h) as well as the turnaround time (15 h compared to 31.1 h) when applied for all isolates.

Conclusions

This study implies that the use of VITEK®REVEAL™ enables swift adaptations of antibiotic treatment strategies. By considerably minimizing the turnaround time, healthcare professionals can promptly make necessary adjustments to therapeutic regimens. Notably, these findings underscore the potential of VITEK®REVEAL™ in expediting appropriate antibiotic interventions, even in less ideal conditions. Further studies in varied laboratory contexts are required to validate these encouraging outcomes.

Introduction

Bloodstream infections particularly those leading to sepsis and septic shock pose a substantial threat to patient health resulting in increased morbidity and mortality rates.1 Timely and appropriate administration of targeted antibiotic therapy is crucial for mitigating the deleterious impact of these infections on clinical outcomes. Delayed initiation of targeted antibiotic treatment has been associated with poorer outcomes.1–4 The importance of rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) in guiding therapy decisions to ensure effective treatment of the causative pathogens is well recognized. Over the last two decades there has been a significant emphasis on shortening the blood culture diagnostic path including pathogen identification and AST to ultimately decrease the time-to-antibiotic adaptation along with improving the management of bloodstream infections.2

Rapid phenotypic AST systems have emerged as a potential solution to expedite the delivery of accurate and actionable AST results enabling clinicians to make timely adjustments to antibiotic treatments. These novel technologies are being pursued to increase the speed of phenotypic testing, aiming to evaluate morphological and/or physiological responses earlier in the course of antimicrobial exposure in vitro than the traditional 16–24 h subculture process. Changes to cell size, mass, membrane integrity, metabolism and DNA transcription are among the responses being examined in detail elsewhere.5,6 Among these cutting-edge technologies, PhenoTest BC (Accelerate Diagnostics, Tucson, AZ, USA) provides AST results in just 7 h. This system utilizes time-lapse imaging of bacterial cells under dark-field microscopy to analyse morphological and kinetic changes and it has been both cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration and approved by Conformité Européenne for in vitro Diagnostics (CE-IVD).7 Among these, the dRAST (QuantaMatrix, Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea)8 and ASTar R (Q-linea, Uppsala, Sweden)9 methods both evaluate morphological changes by time-lapsed microscopic imaging of bacterial cells exposed to antimicrobials. Both yield results in ∼6 h and require off-line identification of the bacteria and both are CE-IVD approved.10 One such phenotypic system is the CE-IVD approved VITEK®REVEAL™ (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). VITEK®REVEAL™ uses Small Molecule Sensors, which detects the volatile organic compounds released by microorganisms as they grow to assess susceptibility to antibiotics. Sensor colour changes report growth monitored every 10 minutes, allowing the rapid phenotypic identification of growth or its absence and the associated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination to be made. The VITEK®REVEAL™ system offers an AST result from positive blood culture (PBC) in average of 5.5 h, significantly reducing the time required for an accurate AST result.11

Although the advantages of administering antibiotics promptly and appropriately are widely recognized, it is crucial to emphasize the harmful consequences of delayed antibiotic treatment for patients with bloodstream infections. Several studies have suggested detrimental consequences associated with late administration of targeted antibiotics. Patients who experience delayed initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy have been shown to have higher mortality rates and increased morbidity.12–14 Applying appropriate antibiotic therapy strategically contributes to preserve the balance of the microbiome and limit potential adverse events at the patient level ultimately lowering the chances of MDR strain emergence at the community level.15 Furthermore, the impact of delayed antibiotic treatment extends beyond the individual patient. In a study conducted by Vasikasin et al., it was observed that delayed initiation or non-initiation of targeted antibiotic therapy in bloodstream infections could be associated with a higher rate of healthcare-associated infections. These infections not only increase the burden on healthcare facilities but also contribute to the spread of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, further exacerbating the challenges of managing bloodstream infections.16

Clinical management of bloodstream infections has also to be considered in link with the associated PBCs workflow that is different between all microbiology laboratories. This retrospective study evaluated the potential impact of the introduction of the BioFire Blood Culture Identification 2 Panel (BCID2, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and the VITEK®REVEAL™ Rapid AST system on the management of PBC workflow and bloodstream infections treatment adaptations in a tertiary hospital in France with single shift laboratory. By examining the implementation of these rapid ID and AST systems, the study sought to assess their potential to improve the turnaround time of AST results and subsequently influence bloodstream infection management.

Objectives

Simulate the potential improvements in time-to-result (TTR), turnaround time (TAT) and time-to-antibiotic adaptation on PBCs with the introduction of the VITEK®REVEAL™ and BCID 2 compared to standard of care (SOC).

Simulate the potential improvements in TTR, TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation by applying the VITEK®REVEAL™ and BCID2 to some PBCs, where there could be a possibility of reading the results on the same day when the Gram stain was available before noon.

Simulate this potential improvement according to the working hours of the laboratory.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

Gram-negative monomicrobial PBCs were tested between November 2021 and March 2022 with BCID 2 and VITEK®REVEAL™ as well as the SOC using MALDI-TOF MS (VITEK®MS, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) for identification and VITEK®2 with N233 AST cards (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) for AST of isolated colonies. The BCID 2 Panel represents a multiplex PCR technology for a rapid identification of 33 pathogens and 10 resistance markers directly from PBC. It covers the most common determinant of bloodstream infections with a turnaround time of ∼1 hour.17 BCID 2 was exclusively used for identification purposes within the study.

This retrospective cohort was selected based on a previous study evaluating the performance and accuracy of VITEK®REVEAL™ compared with SOC.18

SOC laboratory procedures/methods

The laboratory working hours were from 8 AM to 6 PM. PBC’s subcultures was performed by one technician until 12 AM. From 12 AM to 8 AM, PBCs remained in the BACT/ALERT®3D (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), and no subculture procedure was applied.

Data collection

SOC results and clinical data were retrospectively aggregated from electronic patient records, VITEK®REVEAL™ TTR for each patient was used to simulate different time points. Two different scenarios were assessed:

Scenario 1 (REVEAL S1): VITEK®REVEAL™ initiated for PBC when Gram stain was available before 12 PM and SOC initiated otherwise. This scenario hypothesized that although the combination of BCID2 and VITEK®REVEAL™ is not used systematically for the all isolates in a single shift laboratory, their usage even sparsely could potentially affect the average TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation.

Scenario 2 (REVEAL S2): VITEK®REVEAL™ initiated for all PBC.

Description of time points

These scenarios were applied to be able to simulate the routine of the laboratory and then TTR (between run initiation and AST results), TAT (turnaround time from PBC positivity to actionable AST, i.e. validated report) and time-to-antibiotic adaptation (time from PBC to antibiotic adaptation) were collected. While the SOC had real data for the time for PBC, Gram stain, TTR, TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation, the REVEAL (Scenario 1 and 2) arms only had observed times for PBC, Gram stain and TTR; other time points including TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation were simulated using average time points in the institution. TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation were shown in time and calendar days as well (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Observed and simulated time points used to describe the SOC and simulated workflows. T0, blood culture positivity; T1, Gram stain time; T2, time-to ID (VITEK MS or BCID2); T3, AST run initiation; T4, AST report time; T5, validated AST report and T6, time-to antibiotic adaptation.

Antibiotic escalation or de-escalation

‘Antibiotic escalation’ was defined as changing to a broader spectrum antibiotic, addition of one or more antibiotics or conversion of oral (PO) to intravenous (IV) route. Antibiotic de-escalation was defined as changing to a narrower spectrum antibiotic, cessation of one or more antibiotics or changing from an IV to PO route of an appropriate drug (i.e. PO ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin).

An antibiotic modification could not be double counted as a change targeting both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms.19

An AST result was considered actionable if the result was obtained during the laboratory working hours. To assess the impact of laboratory working hours on TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation, a simulation of extending the laboratory operations until 10 PM was compared to the current laboratory closing time (6 PM). We hypothesized that extending laboratory working hours until 10 PM could potentially affect the TAT, as more samples could be processed and analysed within the same day of positivity. This could lead to faster actionable results and earlier adjustments in antibiotic therapy, surrogates of better patient outcomes.

The statistical hypothesis was formulated on the basis that VITEK®REVEAL™ has a faster TTR than SOC11 and as it is initiated directly from the PBC, it will have a shorter TAT and faster time-to-antimicrobial adaptation. A paired t-test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Study population

Among 79 patients included in the study, 51% (40) were male and 49% (39) were female. The mean age distribution was 67.2 ± 15.0. The main wards of admission were emergency (32 patients; 40%), inpatient clinics (26 patients; 33%), surgical clinics (11 patients; 15%), ICUs (nine patients; 12%) and outpatient clinic (one patient; 1%) (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). The species distribution was: 47 Escherichia coli (59%), 13 Klebsiella pneumoniae (16%), seven Pseudomonas aeruginosa (9%), six Enterobacter cloacae (8%), four Klebsiella oxytoca (5%), one Klebsiella aerogenes (1.5%) and one Acinetobacter baumannii (1.5%). Sixty-two per cent (49/79) turned positive outside the laboratory operating hours, which led to 65% (51/79) of the PBCs having a Gram stain result before 12 PM.

Time to result and turnaround time following Scenarios 1 and 2

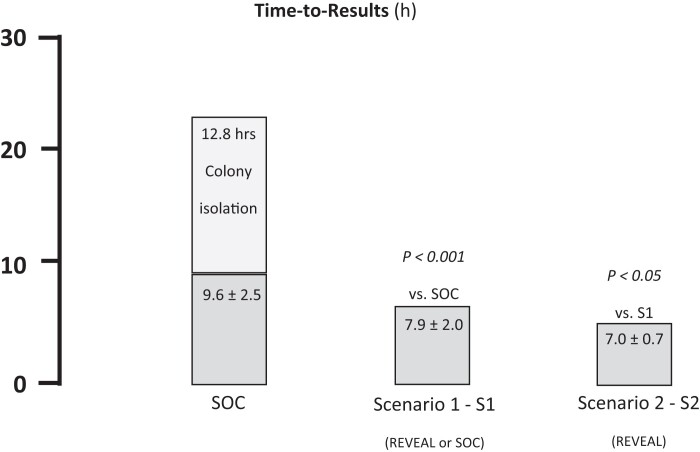

VITEK®REVEAL™ AST TTR was significantly shorter than that observed AST for the SOC (7.0 h ± 0.7 versus 9.6 h ± 2.5 h, P < 0.001, Figure 2, Table S2). Scenario 2 AST TTR was significantly shorter than Scenario 1 (7.0 h ± 0.7 versus 7.9 h ± 2.0 h, P < 0.05, Figure 2, Table S2). On top of SOC AST TTR, an additional 12.8 h average incubation time was observed to obtain isolated colonies to initiate AST using VITEK®2 while VITEK®REVEAL™ could be launched directly from PBCs (Figure 2, Table S2).

Figure 2.

Average TTR obtained with the SOC and the two scenarios using VITEK®REVEAL™. Scenario 1: REVEAL used for PBCs with Gram stain results available before noon, or testing using SOC otherwise. Scenario 2: REVEAL used for all PBCs.

Average TAT was significantly shorter with VITEK®REVEAL™ when compared to SOC for both Scenarios 1 and 2 (Table S2). Indeed, when applying Scenario 1, TAT was 20.1 h ± 6.5 and 31.1 h ± 7.7 h for VITEK®REVEAL™ and SOC, respectively (P < 0.001). It should be noted that Scenario 1 includes 65% of VITEK®REVEAL™ and 35% of SOC. When applying Scenario 2 TAT was 15.0 h ± 4.9 and 31.1 h ± 7.7 h for VITEK®REVEAL™ and SOC, respectively (P < 0.001).

An AST report was considered actionable when the results were obtained during the operation hours, otherwise it was considered that the result could be actionable next day. When assessing TAT by calendar day following BC positivity, implementation of VITEK®REVEAL™ resulted in a shift to the left towards lower values (i.e. faster actionable results) compared to SOC for Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 and the proportion of samples that could be actionable on day 0 for VITEK®REVEAL™ increased with each hour the laboratory extended the closing time from 6 to 10 PM. Following Scenario 1, AST results were actionable at day 1, day 2 and day 3 for 68%, 30% and 2% of the patients, respectively. Using VITEK®REVEAL™ combined to rapid identification using BCID2, actionable AST results could be available for up to 11% and 71% of the patients the same day or the day following BC positivity, respectively. When increasing laboratory working hours to 10 PM, these proportions reached 32% and 67% (Figure 3a). Following Scenario 2, with no conditional initiation of VITEK®REVEAL™ depending on Gram stain result timing during the day, a similar trend was observed for higher proportion of patients. Indeed, with increased laboratory working hours, the proportion of patients with actionable results the day of BC positivity (day 0) reached 51% (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Turnaround time from day of PBC positivity (D0) observed with the SOC or VITEK®REVEAL™ for Scenario 1 when extending laboratory testing hours from 6 PM (current status) to 10 PM. (b) Turnaround time from day of PBC positivity (D0) observed with the SOC or REVEAL for Scenario 2 when extending laboratory testing hours from 6 PM (current status) to 10 PM. D0, Day 0; D1, Day 1; D2, Day 2 and D3, Day 3. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Time-to-antibiotic adaptation

Among the 79 patients included, 49 had antimicrobial adaptation following AST results with SOC: 24 (48.9%), 18 (36.7%) and seven (14.3%) of these adaptations were de-escalation, escalation, and maintenance of the same spectrum of activity, respectively.

The mean time-to-antibiotic adaptation was 51.6 h ± 27.3 h with SOC and was significantly shorter when implementing VITEK®REVEAL™ according to Scenario 1 (34.9 h ± 18.0 h, P < 0.001) or Scenario 2 (26.8 h ± 5.1 h P < 0.001) (Figure 4, Table S2). It is worth noting that while the SOC produces observed data, VITEK®REVEAL™ data are simulated.

Figure 4.

Time-to-antibiotic adaptation from day of BC positivity (D0) observed with the SOC or REVEAL for Scenario 1 (S1) and Scenario 2 (S2). Furthermore, the clinical value of VITEK®REVEAL™ can be effectively used even in centres that process PBCs round the clock. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Discussion

Timely and appropriate administration of antibiotic therapy is crucial in mitigating the deleterious effects of bloodstream infections on clinical outcomes. Delayed initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment has been associated with higher mortality rates and increased morbidity. Therefore, reducing the time between diagnosis of BSI diagnosis and targeted antibiotic administration is of utmost importance.20–24

This retrospective study evaluated the potential impact of the introduction of BCID2 genotypic ID and VITEK®REVEAL™ rapid phenotypic AST systems on the management of PBC workflow and the potential treatment adaptations. The results of the study suggested that the use of the VITEK®REVEAL™ rapid AST system led to significantly shorter TTR and TAT compared to the SOC using VITEK®2. The TTR for VITEK®REVEAL™ was 7.1 h, while SOC had a TTR of 9.6 h without including the required subculture time that was 12.8 h in average. Similarly, the TAT from BC positivity for VITEK®REVEAL™ was 15.0 h, whereas the SOC had a TAT of 31.1 h. These findings highlight the potential of rapid phenotypic AST systems in expediting the delivery of rapid AST results enabling clinicians to initiate appropriate antibiotic therapy sooner.

The importance of shorter TTR, TAT and time-to-antibiotic adaptation is evident when considering the deleterious effects of delayed antibiotic treatment on patients with bloodstream infections. Numerous studies have demonstrated the association between delayed initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy and higher mortality rates and increased morbidity. The findings of this study align with previous research and emphasize the need for rapid AST systems to improve patient outcomes.12–14,20,21

The implementation of rapid ID and AST systems such as BCID2 and VITEK®REVEAL™ can potentially support addressing these challenges by reducing the time required for obtaining accurate AST results. The shorter TTR and TAT provided by the VITEK®REVEAL™ system could enable clinicians to make timely adjustments to antimicrobial therapy, improving patient outcomes and reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections.16

This study presents a monocentric study featuring a retrospective analysis coupled with associated assumptions. The core assumption revolves around the equivalence between the antimicrobial adjustments that could have been enacted using VITEK®REVEAL™ results achieved through the SOC. The potential for categorical discrepancies between the VITEK®REVEAL™ and SOC pathways to yield divergent decisions is acknowledged. This potential bias is, however, mitigated by the fact that the SOC’s AST relied on VITEK®2, which incorporated a panel of 18 drugs, 15 of which (over 80%) overlapped with the antibiotic panel used in tandem with the VITEK®REVEAL™ system during this study. Additionally, recent work by Tibbets et al. underscores a robust agreement exceeding 95% between these methodologies, both categorically and essentially.11

This study is a retrospective analysis focused on a specific subset of monomicrobial samples that were previously subject to an evaluation of VITEK®REVEAL™ AST performance.18 As a result, only bacterial species claimed on the VITEK®REVEAL™ system were included in the analysis. In a practical context, the immediate integration of the VITEK®REVEAL™ system into routine clinical practice post-Gram stain results could lead to tests being discarded if bacteria fell outside the VITEK®REVEAL™ system’s intended use. This scenario would necessitate the use of alternative AST methods potentially causing delays in obtaining AST results and skewing the distribution of time required. However, it is noteworthy that the species recognized by the version of the VITEK®REVEAL™ system used in this study—namely, P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, K. aerogenes, E. cloacae, C. freundii and C. koseri—reflect ∼90% of the species commonly isolated from Gram-negative blood culture samples.25 Hospital-acquired infections contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality among critically ill patients, with >50% of these infections attributed to commonly isolated Gram-negative bacteria. Among this demographic, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa are frequently encountered. The clinical important drug–bug combinations for Gram-positive pathogens are mostly predicted by bacterial identification, e. g. Enterococcus faecalis versus E. faecium or Staphylococcus aureus versus coagulase-negative staphylococci, as well as by limited resistance markers, such as mecA/mecC for meticillino-resistant staphylococci and vanA/vanB for vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Therefore, molecular tests can be sufficient to drive clinical decision. On the other hand, resistance among Gram-negative pathogens can be driven by numerous different resistance mechanisms (ESBL, carbapenemases and a combination of expression levels of enzymes, porins and efflux pumps), so there is no handful of resistance markers able to confidently predict susceptibility, therefore, clinicians need the entire phenotypic antibiogram to confidently decide on the appropriate target therapy.26–28 Thus, the limitation stemming from this restricted species coverage is unlikely to significantly affect the observations drawn from this study.

In this study, it is important to note that the BCID2 system was used solely for the purpose of bacterial identification and was not employed for detecting resistance markers. However, it is worth mentioning that in healthcare facilities where a high prevalence of MDR organisms is observed, the potential of BCID2 for resistance marker detection could be harnessed effectively.

Despite these limitations, results from this retrospective modelling study support the notion that the VITEK®REVEAL™ has the potential to positively influence the management of patients with bacteraemia. By reducing the turnaround time by 16.1 h, prompt escalations and de-escalations could be made. Furthermore, the clinical value of VITEK®REVEAL™ can be effectively used even in centres that do not process PBCs round the clock. The use of VITEK®REVEAL™ in this supposed unfavourable context could considerably decrease the turnaround time empowering clinicians to initiate appropriate antibiotic therapy faster. Further interventional studies in various laboratory settings are needed to confirm these observations.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Ismail Yuceel-Timur, Global Medical Affairs, bioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France.

Elise Thierry, Clinical Investigation Center CIC1435, Inserm, CHU Limoges, Limoges, France.

Delphine Chainier, Inserm, University of Limoges, CHU Limoges, Limoges UMR 1092, France.

Ibrahima Ndao, Clinical Investigation Center CIC1435, Inserm, CHU Limoges, Limoges, France.

Maud Labrousse, Clinical Investigation Center CIC1435, Inserm, CHU Limoges, Limoges, France.

Carole Grélaud, Inserm, University of Limoges, CHU Limoges, Limoges UMR 1092, France.

Yohann Bala, Global Medical Affairs, bioMérieux, Marcy L’Etoile, France.

Olivier Barraud, Clinical Investigation Center CIC1435, Inserm, CHU Limoges, Limoges, France; Inserm, University of Limoges, CHU Limoges, Limoges UMR 1092, France.

Funding

This paper was published as part of a supplement financially supported by bioMérieux.

Transparency declarations

I.Y.T. and Y.B. are employees at bioMérieux. O.B. holds a position within bioMérieux’s scientific round table. E.T., D.C., I.N., M.L. and C.G. have not made any transparency declarations.

Author contributions

All authors attest that they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. I.Y.T., Y.B. and O.B. conceived the idea, and I.Y.T. and Y.B. drafted the paper. E.T., D.C., I.N., M.L. and C.G. collected the study data. All authors contributed to critically revise the manuscript and approved the final article.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022; 399: 629–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verway M, Brown KA, Marchand-Austin A et al. Prevalence and mortality associated with bloodstream organisms: a population-wide retrospective cohort study. J Clin Microbiol 2022; 60: e0242921. 10.1128/jcm.02429-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 1589–96. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Im Y, Kang D, Ko RE et al. Time-to-antibiotics and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis and septic shock: a prospective nationwide multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 19. 10.1186/s13054-021-03883-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Humphries RM. Update on susceptibility testing: genotypic and phenotypic methods. Clin Lab Med 2020; 40: 433–46. 10.1016/j.cll.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Behera B, Anil Vishnu GK, Chatterjee S et al. Emerging technologies for antibiotic susceptibility testing. Biosens Bioelectron 2019; 142: 111552. 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pancholi P, Carroll KC, Buchan BW et al. Multicenter evaluation of the accelerate PhenoTest BC kit for rapid identification and phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing using morphokinetic cellular analysis. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56: e01329-17. 10.1128/JCM.01329-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grohs P, Rondinaud E, Fourar M et al. Comparative evaluation of the QMAC-dRAST V2.0 system for rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing of Gram-negative blood culture isolates. J Microbiol Methods 2020; 172: 105902. 10.1016/j.mimet.2020.105902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klintstedt M, Molin Y, Sandow M et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility test system delivering phenotypic MICs in hours from positive blood cultures for fastidious- and non-fastidious pathogens. 2018; ASM Poster 218.

- 10. Banerjee R, Humphries R. Rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods for blood cultures and their clinical impact. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 635831. 10.3389/fmed.2021.635831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tibbetts R, George S, Burwell R et al. Performance of the reveal rapid antibiotic susceptibility testing system on gram-negative blood cultures at a large urban hospital. J Clin Microbiol 2022; 60: e0009822. 10.1128/jcm.00098-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Balamuth F et al. Delayed antimicrobial therapy increases mortality and organ dysfunction duration in pediatric sepsis. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: 2409–17. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savage RD, Fowler RA, Rishu AH et al. The effect of inadequate initial empiric antimicrobial treatment on mortality in critically ill patients with bloodstream infections: a multi-centre retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2016; 11: e0154944. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Han M, Fitzgerald JC, Balamuth F et al. Association of delayed antimicrobial therapy with one-year mortality in pediatric sepsis. Shock 2017; 48: 29–35. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ruppé E, Burdet C, Grall N et al. Impact of antibiotics on the intestinal microbiota needs to be re-defined to optimize antibiotic usage. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 3–5. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vasikasin V, Rawson TM, Holmes AH et al. Can precision antibiotic prescribing help prevent the spread of carbapenem-resistant organisms in the hospital setting? JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023; 5: dlad036. 10.1093/jacamr/dlad036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Banerjee R, Teng CB, Cunningham SA et al. Randomized trial of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based blood culture identification and susceptibility testing. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 1071–80. 10.1093/cid/civ447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parmeland L, Chainier D, Pontvianne A et al. Performance of VITEK®REVEAL™ system for rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing of gram-negative bacteremia: results from a multicenter study in France. 2023; ECCMID 2023 Poster 0343.

- 19. Banerjee R, Komarow L, Virk A et al. Randomized trial evaluating clinical impact of RAPid IDentification and susceptibility testing for gram-negative bacteremia: RAPIDS-GN. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73: e39–46. 10.1093/cid/ciaa528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest 2009; 136: 1237–48. 10.1378/chest.09-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beuving J, Wolffs PF, Hansen WL et al. Impact of same-day antibiotic susceptibility testing on time to appropriate antibiotic treatment of patients with bacteraemia: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2015; 34: 831–8. 10.1007/s10096-014-2299-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mizrahi A, Amzalag J, Couzigou C et al. Clinical impact of rapid bacterial identification by MALDI-TOF MS combined with the bêta-LACTA™ test on early antibiotic adaptation by an antimicrobial stewardship team in bloodstream infections. Infect Dis (Lond) 2018; 50: 668–77. 10.1080/23744235.2018.1458147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dubourg G, Lamy B, Ruimy R. Rapid phenotypic methods to improve the diagnosis of bacterial bloodstream infections: meeting the challenge to reduce the time to result. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 935–43. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Briggs N, Campbell S, Gupta S. Advances in rapid diagnostics for bloodstream infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021; 99: 115219. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006; 34: 344–53. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194725.48928.3A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fiori B, D'Inzeo T, Giaquinto A et al. Optimized use of the MALDI BioTyper system and the FilmArray BCID panel for direct identification of microbial pathogens from positive blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54: 576–84. 10.1128/JCM.02590-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Culshaw N, Glover G, Whiteley C et al. Healthcare-associated bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: descriptive cross-sectional database study evaluating concordance with clinical site isolates. Ann Intensive Care 2014; 4: 34. 10.1186/s13613-014-0034-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buetti N, Tabah A, Loiodice A et al. Different epidemiology of bloodstream infections in COVID-19 compared to non-COVID-19 critically ill patients: a descriptive analysis of the Eurobact II study. Crit Care 2022; 26: 319. 10.1186/s13054-022-04166-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.