Abstract

A common feature of neurodegenerative disorders, in particular Alzheimer's disease (AD), is a chronic neuroinflammation associated with aberrant neuroplasticity. Development of neuroinflammation affects efficacy of stem and progenitor cells proliferation, differentiation, migration, and integration of newborn cells into neural circuitry. However, precise mechanisms of neurogenesis alterations in neuroinflammation are not clear yet. It is well established that expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in glial cells marks neuroinflammatory events, but less is known about contribution of NLRP3 to deregulation of neurogenesis within neurogenic niches and whether neural stem cells (NSCs), neural progenitor cells (NPCs) or immature neuroblasts may express inflammasomes in (patho)physiological conditions. Thus, we studied alterations of neurogenesis in rats with the AD model (intra-hippocampal injection of Aβ1-42). We found that in Aβ-affected brain, number of CD133+ cells was elevated after spatial training in the Morris water maze. The number of PSA-NCAM+ neuroblasts diminished by Aβ injection was completely restored by subsequent spatial learning. Spatial training leads to elevated expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the SGZ (subgranular zones): CD133+ and PSA-NCAM+ cells started to express NLRP3 in sham-operated, but not AD rats. Taken together, our data suggest that expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in CD133+ and PSA-NCAM+ cells may contribute to stimulation of adult neurogenesis in physiological conditions, whereas Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration abolishes stimuli-induced overexpression of NLRP3 within the SGZ neurogenic niche.

Keywords: Neurogenesis, NLRP3 inflammasome, Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroinflammation, Spatial learning

Introduction

It is known that adult neurogenesis continues throughout life and occurs mainly in two neurogenic niches: subventricular (SVZ) and subgranular (SGZ) zones of the brain. One of the most important functions of adult neurogenesis is an endogenous recovery mechanism (Apple et al. 2017). SGZ-generated neurons migrate to a layer of hippocampal granular cells where they differentiate into mature granular neurons and integrate into neuronal circuitry. Since the hippocampus plays a central role in learning and memory, the functional contribution of neurogenesis to these processes is of particular interest.

Microenvironment formed in neurogenic niches maintains the population of neural stem cells (NSCs) and neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs) and regulates the “decision making” of NSCs/NPCs to differentiate to neuronal or glial lineages (neurogenesis and gliogenesis, respectively). Such regulation is provided by complex cell–cell interactions and signals (Conover and Notti 2008; Goldberg and Hirschi 2009). The neurogenic niche is almost completely intertwined with blood vessels; thereby, brain microvessel endothelial cells and pericytes come into close contact with the niche being responsible for the vascular support of neurogenesis. Another important component of pro-neurogenic microenvironment is a population of glial cells (astroglia, microglia) which provide the release of a wide spectrum of regulatory molecules (cytokines, growth factors, gliotransmitters) to NSCs/NPCs (Cope and Gould 2019).

Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration is a well-known phenomenon with neurogenesis-modulating effects; presumably, such effects underlie cognitive deficits and memory dysfunction. There is a growing evidence that accumulation of Aβ oligomers causes suppression of adult neurogenesis. However, some studies suggest that impairment of neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) might be more complex and multiple-valued (Pan et al. 2016; Baglietto-Vargas et al. 2017). It is commonly accepted that neuroinflammation affecting neurogenic microenvironment could play a crucial role in aberrant neurogenesis in AD.

There are many factors contributing to neuroinflammation in AD. The dominant hypothesis is that a vicious loop forms between glial activation and neuron death, that is, the damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs) released from degenerate neurons activate glial cells through toll-like receptors (TLRs), and neuroinflammation further assists the progression of neurodegeneration (Fan and Pang 2017). Activation of these receptors leads to the assembly of the cytosolic multiprotein complex—inflammasome NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3)—that is the molecular machinery responsible for caspase-assisted processing of pro-inflammatory interleukins (IL-1β, IL-18, IL-33 Lee et al. 2013; Shao et al. 2015; Freeman and Ting 2016; Chernykh et al. 2018). It was shown that Aβ oligomers interact with NLRP3 directly, this promoting neuroinflammation in AD (Nakanishi et al. 2018). Concurrently, inhibitors of NLRP3 activity were reported to demonstrate beneficial effects in APP (amyloid precursor protein) transgenic mice (AD model), including decreased levels of Aβ accumulation, suppression of oxidative stress, and reduced activation of microglia (Yin et al. 2018).

Neuroinflammation was proved to alter regenerative potential of NSCs/NPCs (Okano and Sawamoto 2008; Boese et al. 2020). Expression of NLRP3 in glial cells was shown to result in neurogenesis suppression; and many factors inhibiting NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β axis were reported to serve as potent pro-neurogenic agents in neurodegeneration, neuroinfection, and depression (Heneka et al. 2013; Du et al. 2016; Fan et al. 2016; Chan et al. 2019; Ashraf et al. 2019). IL-1β is believed to act as an anti-proliferative and pro-gliogenic stimulus for neurogenesis (Green and Nolan 2012). Therefore, high levels of IL-1β secretion lead to reduction in neurogenesis efficacy (Wu et al. 2013). However, some studies revealed stimulating effect of astroglia-derived cytokines on neurogenesis and synaptogenesis (Chugh et al. 2013). In our previous paper, we demonstrated that pro-inflammatory phenotype of perivascular astroglia and endothelial progenitor cells was positively associated with neurogenesis recovery in neurodegeneration (Chernykh et al. 2018).

Although the role of NLRP3/IL-1β-mediated neuroinflammation in the suppression of neurogenesis is well established, some unresolved questions remain. Specifically, it is not known whether stem or progenitor cells in a neurogenic niche may express NLRP3 inflammasomes, and how expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes contributes to aberrant neurogenesis seen in neurodegeneration. Accordingly, the main goal of this study was to assess an effect of cognitive stimulation on the expression of inflammasomes in cells at the early stages of adult SGZ neurogenesis (NSC/NPCs, neuroblasts) in physiological conditions and in Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration.

Materials and Methods

Animals

In our experiment, we used 7-month-old male Wistar rats weighing 250–300 g. Skeleton growth in male rats stops at the age of about 7–8 months. According to research data, rats are considered adults from this period of life, which corresponds to the adult period in humans (Sengupta 2013). The pathology modeled in this study is associated with age, and the study of adult neurogenesis is valid in mature individuals. Due to these facts, we used 7-month-old rats in the experiment. The animals were kept in cages with free access to water and food at a constant temperature of 21 ± 1 °C and a regular light cycle of 12 h day/12 h night. The experiment was carried out in accordance with the principles of humanity set forth in the European Community Directive (2010/63/EC) and approved by the Bioethical Commission of Professor V. F. Voino-Yasenetsky Krasnoyarsk State Medical University, Krasnoyarsk, Russia.

Groups of Animals and the Experiment Design

During the experiment, the animals were randomly assigned to four groups. Group 1 comprised rats injected with PBS (sham-operated animals) with cognitive training (spatial learning) for 5 days in the Morris water maze (MWM) (n = 7). Group 2 was composed of rats injected with PBS (sham-operated animals) without cognitive training (spatial learning) in the MWM (n = 7). Group 3 included rats injected with soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1–42 with cognitive training (spatial learning) for 5 days in the MWM (n = 7). Group 4 comprised rats injected with soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1–42 without cognitive training (spatial learning) in the MWM (n = 7).

Modeling of Alzheimer’s Type Neurodegeneration

To induce early changes in neurogenesis in the hippocampus soluble amyloid beta were administered to rats according to a previously described procedure (Epelbaum et al. 2015; Komleva et al. 2018). Specifically, rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and supplemented throughout the surgery as required. After reaching the required level of anesthesia, rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame (Neurostar, Germany). The skin overlaying the skull was retracted to drill holes, and injections were made using a Hamilton microsyringe, which was slowly lowered to the place. Beta-amyloid Aβ1-42 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was dissolved in sterile 0.1 MPBS (pH 7.4) and a solution was prepared at a concentration of 50 µM. To obtain soluble forms of beta-amyloid, Aβ1-42 was aggregated by incubation at 37 °C for 7 days prior to administration. To model AD, rats were injected with 5 μl of Aβ1-42. The co-ordinates on both sides of the injection sites were adapted from the Franklin and Paxinos atlas (Paxinos and Franklin 2004): anterior–posterior axis: − 2.0 mm from bregma; medio-lateral axis: + 1.3 mm from midline; and dorso-ventral axis: − 1.9 mm from dura. Aβ1-42 were injected over a 5-min period (1 μl/min), and the needle was left in place for another 5 min after injection (Epelbaum et al. 2015). Control rats were injected with PBS using the same procedure. The animals were taken to the individual cages after the surgery (Cetin and Dincer 2007).

Setting Conditions for Cognitive Stimulation

MWM is a spatial training test for rodents, which uses additional signals on the pool walls (light sources) for navigation. It has also been previously shown that the MWM is used as cognitive and physical stimulation and can improve or delay cognitive deficits associated with AD or aging (Yeung et al. 2015). The idea is that the animal must learn to use distal cues to navigate a direct path to the hidden platform when launched from different random locations around the pool perimeter. We used four starting locations in the protocol [N (north), S (south), E (east), and W (west)]. Animals were trained and tested in the MWM according to the standard protocol (Vorhees and Williams 2006).

For memory acquisition (Spatial learning stage), the animal was placed in the desired starting position in the maze, facing the pool wall. The animal was released into the water at the water level. The attempt was stopped when the animal reached the platform. For each attempt, a limit of 2 min (120 s) was set. Animals, which did not find the platform during this period, were placed on the platform for memorization. The interval between attempts was 30 s. The purpose of leaving the animal on the platform was to give it an opportunity to orient itself in its position in space and to remember the position of the hidden platform relative to the surrounding cues. Then the animal was placed in the pool from a new point and made four more attempts during the day. In the following days (3 days), training in the maze was repeated. With four attempts per day, 4 days of training were sufficient. To assess long-term memory at the end of the training, a final attempt was given on the fifth day, without hidden platforms.

The experimental and control groups without spatial training were tested in the MWM for one day, but in the absence of a hidden platform. Rats without training allowed us to control the perceived effects of stress and exercise, as well as eliminate defects in motor and visual functions. According to the chronology of the experiment, after a 10-day period following by the operation, rats from groups 1 and 3 were trained in the Morris water maze. Rats of groups 2 and 4 (without training) were tested once in the MWM with subsequent euthanasia and brain sampling.

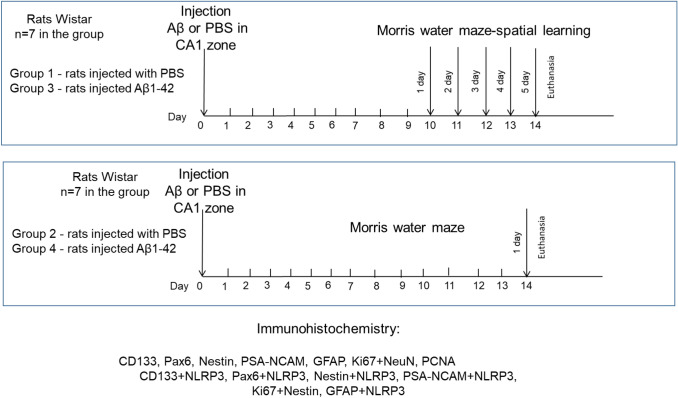

The experiment design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. PBS phosphate-saline buffer, Aβ beta-amyloid

Histological Examination

On day 14th, 30 min later after testing, rats were deeply anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg) with following transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The brains were removed and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and immersed in a 20% sucrose solution fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Using a Thermo Scientific vibratome, sections were made 50 μm thick. The other hemisphere was embedded in paraffin. The brain was cut into 5 μm-thick sections using a section cutter (Leica Biosystems, Germany). The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined under a light microscope (Olympus IX71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

We studied the expression of markers by indirect immunohistochemistry for free-floating sections (Komleva et al. 2015, 2018). In brain sections, the number of cells expressing markers of the early stages of neurogenesis (CD133, Nestin, Pax6, PSA-NCAM), glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP—astrocyte marker) was counted, and the percentage of collocation with NLRP3 in the cells in the dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus was determined.

The following primary antibodies were used as primary antibodies to identify different stages of neurogenesis: CD133—stem cell marker (Anti-CD133 antibody, Abcam ab16518), Pax6—basal progenitor cell marker (Anti-Pax6 antibody, Abcam ab5790), Nestin—neural progenitor cells (Anti-Nestin, Abcam ab 221660), PSA-NCAM—neuroblasts marker (Anti-PSA-NCAM antibody, ThermoFisher Scientific, 14-9118-80), NeuN—marker of neuronal nuclei (Anti-NeuN, Sigma-Aldrich, MAB377), Ki67—cells, proliferating preferentially during late G1, S, G2 and M phases of the cell cycle (Anti-Ki67 antibody, Abcam ab15580), PCNA—a marker of cell proliferation (Anti-PCNA antibody, Abcam ab92552), GFAP—astrocyte marker (Anti-GFAP antibody, Biolegend, 644,701), NLRP3—NLRP3 inflammasome (Anti-NLRP3 antibody, Abcam ab4207). The dilution of primary antibodies for free-floating sections was 1:1000. After incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, the sections were washed in PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The respective secondary antibodies were applied: donkey anti-rabbit IgG AlexaFluor488, donkey anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor488, donkey anti-rabbit IgG AlexaFluor555, donkey anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor555, donkey anti-goat AlexaFluor555 and goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor594 (all 1:1000, Invitrogen). After washing, the sections were placed on glass slides and a mounting fluid (FluoroMount, Invitrogen) was added and covered with a cover glass (Komleva et al. 2015, 2018; Chernykh et al. 2018). Images were taken with a 60× lens on a confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus FluoView) and processed using Olympus FluoView software (Ver.4.0a). We evaluated five fields of view. The results were presented as a relative number of immunopositive cells.

Neurogenesis markers quantifications were performed on one complete DG series per animal considering the subgranular zone (NSCs/NPCs) or the whole thickness of the granular cell layer (immature neurons). The numbers of immunopositive cells/microscope field were quantified for all markers in the DG of the dorsal hippocampus according to Paxinos and Franklin (2004).

Amyloid Histology Procedures—Thioflavin S Staining

To stain the inclusions of beta-amyloid, the dye Thioflavin S was used. First, a 1% solution of Thioflavin S (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in distilled water was prepared, followed by filtration. The free-floating sections were hydrated through a series of ethanol solutions (100%, 95%, 80%, 70%, 1–2 min in each one), placed for a few seconds in water and then stained with 1% Thioflavin S for 30–60 min. Then the sections were subsequently dehydrated through a series of ethyl alcohol solutions (70%, 80%, 95%, 100%, 100%, 1–2 min in each one) and then the sections were placed on a glass slide and mounting fluid was applied (FluoroMount, Invitrogen). Images were taken with a 60× objective on a confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus FluoView) and processed using Olympus FluoView software (Ver.4.0a). Thioflavin S binding to amyloid causes fluorescence emission. Thioflavin S non-selectively binds beta sheet contents of proteins, such as those in amyloid oligomers. Upon binding, Thioflavin undergoes a characteristic blue shift of its emission spectrum. Conversely, Thioflavin S binding to the monomeric forms does not elicit a blue shift and cannot be detected with a florescence microscope. Thioflavin S staining provides a quick alternative to screen for amyloid as the intensity of fluorescence allows good visualization of small amounts of amyloid deposits (Ly et al. 2011).

Statistics

Statistical analysis of the obtained results included descriptive statistics methods using the GraphPad Prism7 program (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Within each sample, the arithmetic mean and the standard error of the mean were determined.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare differences between the two groups when it was not normally distributed. Two-way ANOVA were used to assess the influence of two factors. Subsequent multiple comparisons were performed using a post-hoc Tukey’s criteria. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All results were presented in the form of M ± SEM, where M is the average value, SEM is the standard error of the mean, p is the significance level.

Results

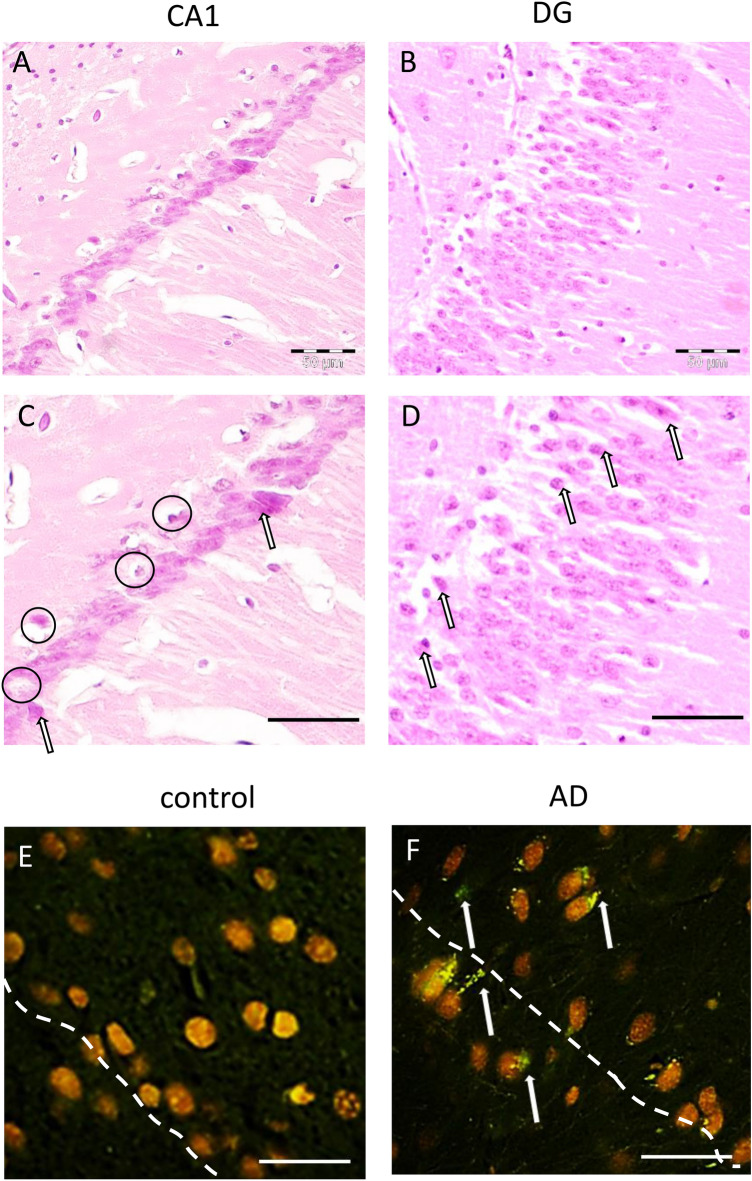

To investigate the effects of Aβ1-42 injection on hippocampal neurons, we examined the neuronal histomorphological changes in the hippocampus (Fig. 2). In the control group rats, no obvious neuronal abnormalities were observed in the hippocampus CA1 region (Fig. 2e). However, in the Aβ-injected rats, more neurons that are degenerative were observed in the hippocampus CA1 and DG region (Fig. 2a–d). A large number of neurons with hyperchromic cytoplasm and nuclear pyknosis were observed. Thioflavin S staining (Fig. 2f) of Aβ illustrates a close Aβ distribution. It was previously confirmed that the presence and amount of toxic oligomers correlate with symptoms in patients with AD, and not with the deposition of amyloid plaques (Lesné et al. 2013).

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of the hippocampus of Aβ-treated and control rats. a–d Hematoxylin–eosin staining of rat hippocampus (×200). In the Aβ-treated group, the majority of CA1 hippocampal neurons (a, c) and DG hippocampal neurons (b, d) exhibited pyknosis and deep staining (arrows). Some neurons and glial cells were significantly swollen and were round, and the space surrounding cells was widened. Scale bar 50 µm. e Thioflavin S staining appearances of normal brain parenchyma in control group. f Thioflavin S staining illustrates inclusions of Aβ, which have green light a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar 30 µm. AD Alzheimer's disease

Aβ1-42 and Spatial Learning Differently Affect Neurogenesis in the SGZ

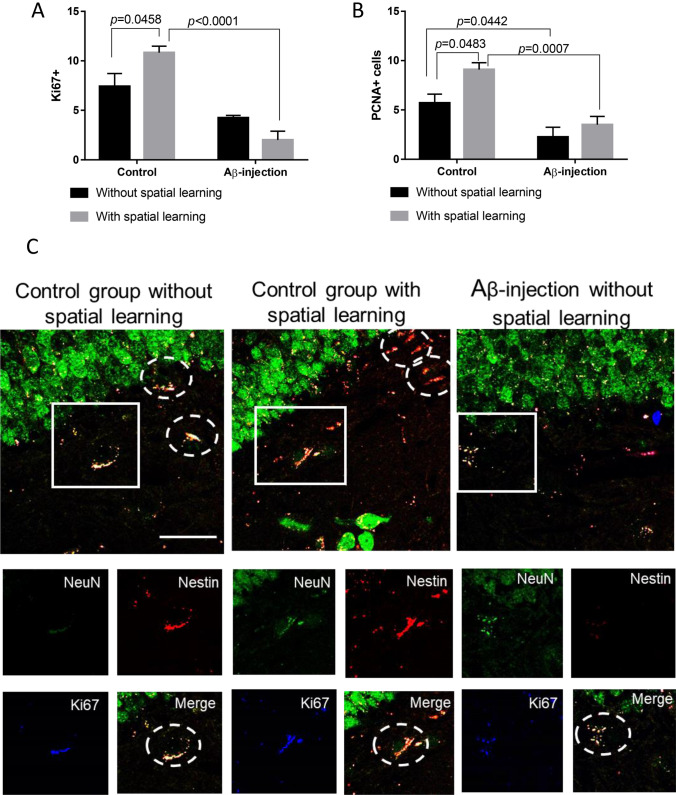

Integral proliferative potential of SGZ cells was assessed with the analysis of Ki67 and PCNA expression. As expected, injection of Aβ1-42 resulted in significant reduction of proliferating cells (PCNA) in the SGZ.

Studying proliferating cells in the SGZ revealed a statistically significant effect of the interaction of two factors (surgery and cognitive training) [F(1.24) = 10.76, p = 0.0032]. In multiple comparisons, we confirmed that cognitive stimulation contributed to an increase in the number of Ki67 proliferating cells in the SGZ in the control group 1 (rats after PBS injection with cognitive training) (10.83 ± 0.65) comparing with animals from the second group without learning in MWM (7.42 ± 1.30) (p = 0.0458). At the same time, cognitive stimulation did not affect the Ki67 expression in the SGZ of the DG in Aβ-induced model (group 3) (2.00 ± 0.89) compared to group 4 (rats after Aβ injection without cognitive training (4.24 ± 0.25) (p = 0.2804) (Fig. 3a). However, a statistically significant difference between control group 1 with cognitive stimulation (10.83 ± 0.65) and experimental group 3 with cognitive stimulation (2 ± 0.89) (p < 0.0001) was observed.

Fig. 3.

Expression of proliferation markers in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. a The number of Ki67 expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. b The number of PCNA expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. c Representative confocal images of proliferating neural progenitor cells and stained for Ki67 (blue), Nestin (red) and NeuN (green), signal overlay (merge). Immunohistochemistry proliferation activity of adult hippocampal Nestin+ progenitor cells confirmed the colocalization of Ki67 and Nestin markers. Scale bar 50 µm. Control—rats with the injection of PBS; the introduction of Aβ—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-42

At the same time, there is another marker of actively proliferating cells. It is PCNA, the nuclear antigen of proliferating cells, which is important for both DNA repair and replication. Expression of PCNA increases during the G1 and S phases and decreases with the transformation of the cell into the G2 and M phases. However, this marker can also be found in the early G0 phase due to the long half-life of eight to twenty hours. This refers to the fact that PCNA is expressed throughout the entire cell cycle process. As a proliferation marker, it is usually used to mark a subgroup of actively dividing cells, which is an indicator of proliferating neuronal stem cells (PCNA-positive cells) in SVZ, SGZ (Zhang and Jiao 2015). Both PCNA and Ki67 can be used to label dividing cells, but PCNA is broader than Ki67 (ibid.).

In this study, the expression of PCNA+ cells in SGZ was also determined. There was a statistically significant effect of the type of intervention (Aβ injection or sham operation) [F(1.24) = 27.28, p < 0.0001], as well as the effect of cognitive training [F(1.24) = 7.201, p = 0.0130]. Multiple comparison of the expression of the PCNA marker depending on cognitive training did not reveal a statistically significant change in PCNA+ cells in the SGZ during Aβ-induced neurodegeneration after training (group 3) (3.50 ± 0.85) compared with animals without training (group 4—rats after Aβ injection without cognitive training) (2.25 ± 0.99) (p = 0.7394) (Fig. 2b). Thus, there was no change in the level of cell proliferation in the DG of the hippocampus when modeling neurodegeneration with and without stimulation of cognitive function. At the same time, learning had a positive effect on a healthy brain, manifested by an increase in the expression of proliferating cells (control group 1—9.1 ± 0.7 vs. control group 2—5.7 ± 0.9) (p = 0.0483, Tukey's criterion) (Fig. 3b).

Using fluorescence confocal microscopy, we detected colocalization of the Ki67+ cells with the early neuronal marker Nestin in the DG (Fig. 3c). The demonstration that Nestin stained processes colocalized with Ki67+ cell in the DG in all groups indicated that these Ki67+ cells exhibited a neuronal phenotype. The Ki67+/Nestin+ cells were located mainly in the SGZ. Therefore, confocal microscopy demonstrated that SGZ of the hippocampus brain contained newly generated cells that coexpressed Ki67 and Nestin.

In this part of the experiment, the expression of early stages markers of neurogenesis in the SGZ and granular zones of the hippocampus was determined in rats. We assessed the expression of the CD133, Nestin, and Pax6 markers. CD133 has previously been shown to be expressed in both hematopoietic and neuropoietic cells. CD133-positive cells are capable of initiating the formation of neurospheres, self-renewal, and multilinear differentiation. In this regard, CD133 is used to identify neuronal stem cells, namely, it marks pluripotent stem cells, while Nestin is a marker of multipotent progenitor cells (Ying et al. 2005).

We evaluated the expression of the CD133 in the SGZ. We found that spatial learning did not induce significant changes of CD133 expression in the SGZ in control groups (after PBS injection). However, it was rather effective in stimulating CD133 expression in Aβ1-42-treated rats (Fig. 4a). We found pronounced effect of cognitive training factor in the study groups [F(1.24) = 5.977, p = 0.0222, two-way ANOVA]. Using multiple comparisons, we confirmed that the number of CD133-immunopositive cells was statistically significantly larger in trained rats 9.0 ± 2.24 compared to untrained Aβ1-42-injected rats 4.9 ± 0.6 (p = 0.0241) (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

Expression of early stages markers of the neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. a The number of CD133 expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. b Immunostaining of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The expression of CD133 (green), scale bar 25 µm. GCL granular cell layer, SGZ subgranular zone. c The number of Nestin-expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. d The number of Pax6 expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. e Immunostaining of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The expression of Nestin (green), scale bar 20 µm. Control—rats with the injection of PBS; the introduction of Aβ—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-42

Next, the marker of multipotent progenitor cells Nestin in the neurogenic niche was determined. It was found that the number of Nestin-expressing cells was changed by AD modeling [F(1.24) = 18.43, p = 0.0003, two-way ANOVA], as well as cognitive stimulation [F(1.24) = 4.532, p = 0.0437]. Multiple comparison test showed that the number of Nestin+ multipotent neuronal precursors was statistically higher in the sham-operated control group without cognitive training in MWM (group 2) (7.3 ± 1.98) than after Aβ1-42 injection without cognitive training (group 4) (1.7 ± 0.2) (p = 0.0494). Similar data were obtained when comparing control and experimental groups after cognitive stimulation in the MLM. Specifically, we compared control rats with training in MWM (10.9 ± 1.6) and rats after Aβ1-42 injection (4.2 ± 1.3) (p = 0.0147) (Fig. 4c, e).

Transcription factor Pax6 is a key regulator of neuronal fate as well as a marker of the proliferation of NSCs (Wen et al. 2008). No significant changes were found in Pax6 expression in the SGZ in all the groups tested; there was no significant influence of the interrelation of training and operation [F(1.24) = 2,398, p = 0.1346, two-way ANOVA] (Fig. 4d).

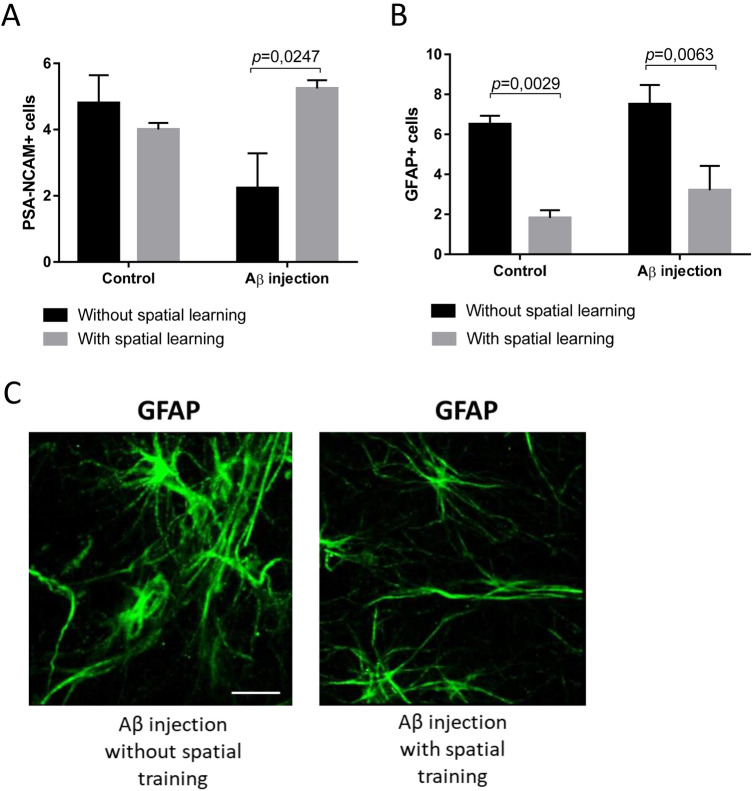

PSA-NCAM expression is a characteristic of neuroblasts, particularly, expression of PSA-NCAM corresponds to specific intervals of neurogenesis when neuronal progenitors migrate and begin to acquire neuronal properties (Zhang and Jiao 2015). We found that the number of neuroblasts was reduced by Aβ1-42 treatment (group 4), but was completely restored by subsequent spatial learning (group 5). No changes in the expression of PSA-NCAM were found in sham-operated animals (Fig. 4a). We identified interaction of two factors (spatial learning in the MWM and operation) in the studied groups [F(1.24) = 7.598, p = 0.0101, two-way ANOVA]. In multiple comparisons, we confirmed that in rats injected with Aβ1-42 and subjected to spatial learning, the number of PSA-NCAM-immunopositive cells was significantly greater (5.24 ± 0.25) compared to untrained rats after Aβ1-42 treatment (2.23 ± 1.05) (p = 0.0247) (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Expression of neuroblasts and astrocytes in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. a The number of PSA-NCAM expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. b The number of GFAP expressing cells pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. c Immunostaining of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. The expression of GFAP (green), scale bar 25 µm. Control—rats with the injection of PBS; the introduction of Aβ—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-42

Next, we determined the expression of GFAP in the cells of the SGZ [F(1.24) = 22.76, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA]. In multiple comparisons using the Tukey’s criterion, significant differences in the expression of GFAP+ cells were detected. In the group with injection of Aβ1-42 and spatial learning, the number of GFAP-immunopositive cells was 3.2 ± 1.22 comparing to untrained rats with a similar injection of a soluble form of Aβ 7.5 ± 0.97 (p = 0.0063). Similar changes were recorded in the group of sham-operated animals: in the group 1, the number of GFAP+ cells in DG was 1.82 ± 0.38 after cognitive training; in the group 2 without cognitive training—6.5 ± 0.43 (p = 0.0029). Thus, in rats subjected to training, the number of GFAP-immunopositive cells within the neurogenic niche was lower than in rats without training (Fig. 5b, c).

Spatial Learning Leads to Diverse Changes in the Expression of Inflammasome NLRP3 Within Neurogenic Niche in Healthy Brain and in Aβ-Affected Brain

In the second series of experiments, we determined expression of NLRP3 inflammasome after spatial learning in a healthy brain (control animals) and in rats after injection of soluble forms of Aβ.

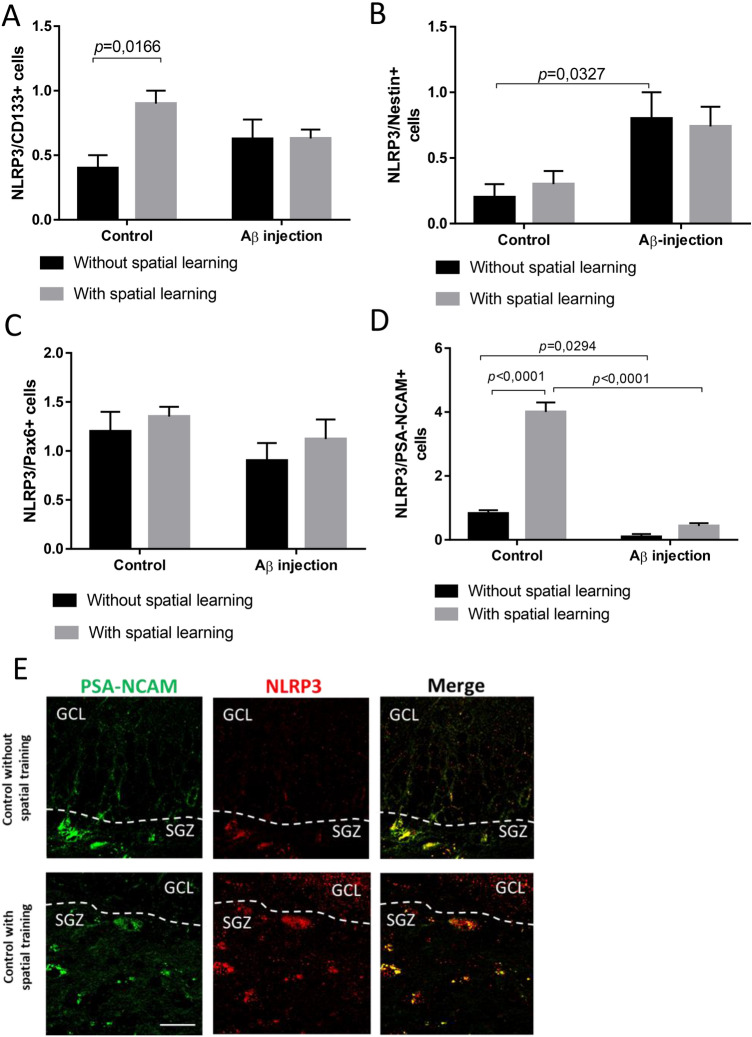

We found that NLRP3 expression within control groups was significantly elevated in CD133+ cells and PSA-NCAM+ cells by the application of spatial learning protocol (Fig. 6a, d), but not in Nestin+ and Pax6+ cells (Fig. 6b, c). Thus, stimulation of neurogenesis in physiological conditions results in overexpression of NLRP3 in NSCs and migrating neuroblasts: spatial learning leads to an increase in the expression of NLRP3 type inflammasomes in neuroblasts in the healthy brain (Fig. 6d), therefore, the number of PSA-NCAM/NLRP3+ cells in rats subjected to Aβ1-42 injection (0.43 ± 0.09) and in a sham-operated rats (4 ± 0.3) were significantly affected by learning (p < 0.0001). Therefore, we observed that Aβ injection resulted in NLRP3 expression reduction in PSA-NCAM+ cells and GFAP+ cells as compared to sham-operated group without spatial learning.

Fig. 6.

Expression of NLRP3 inflammasome at different stages of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. a The number of cells colocalizing CD133 and NLRP3 pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. b The number of cells colocalizing Nestin and NLRP3 pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. c The number of cells colocalizing Pax6 and NLRP3 pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. d The number of cells colocalizing PSA-NCAM and NLRP3 pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. Control—rats with the injection of PBS; Aβ injection—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-42. e Immunohistochemical staining of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Dual immunofluorescent staining: expression of PSA-NCAM (green), expression of NLRP3 (red), signal overlay (merge). Scale bar 25 µm. GCL granular cell layer, SGZ subgranular zone

Expression of NLRP3 in CD133+ cells revealed significant effect of the interaction of two factors (spatial learning and Aβ injection) [F(1.24) = 5.226, p = 0.0314, two-way ANOVA], as well as a significant effect of spatial learning [F(1.24) = 5.353, p = 0.0296, two-way ANOVA] (Fig. 6a). Effect of the interaction of two factors (spatial learning and operation) on NLRP3 inflammasome expression in PSA-NCAM+ neuroblasts was found in the study groups [F(1.24) = 68.18, p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA]. In case of multiple comparison, significant difference was registered in groups without spatial learning (p = 0.0294) (Fig. 6d, e).

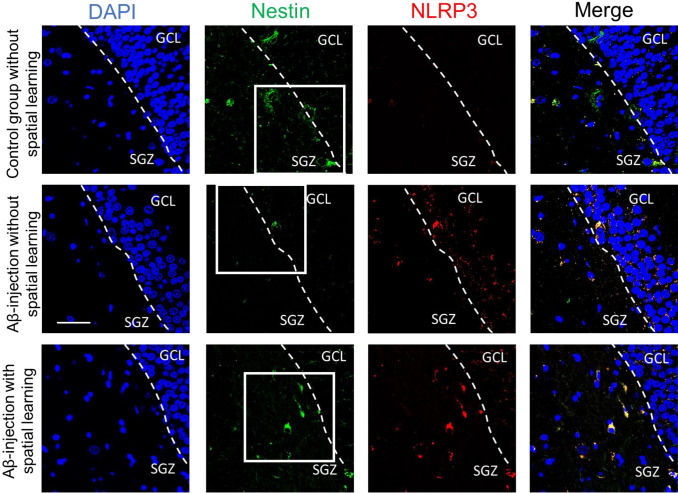

In multipotent progenitor cells expressing Nestin, colocalization with NLRP3 inflammasomes was determined. The type of operation performed (Aβ or PBS injection) has a statistically significant effect [F(1.24) = 13.11, p = 0.0014]. Namely, multiple comparison revealed that colocalization of Nestin/NLRP3 markers was higher in the group after injection of beta-amyloid (0.8 ± 0.2) than in the group of sham-operated mice (0.2 ± 0.1) without cognitive training (p = 0.0327). The cognitive training did not affect the change in inflammasome expression in the compared groups F(1.24) = 0.0193, p = 0.8904 (Figs. 6b, 7).

Fig. 7.

Representative confocal images of proliferating neural progenitor cells expressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and stained for NLRP3 (red), Nestin (green) and DAPI (blue), signal overlay (merge). Scale bar 50 µm. Control—rats with the injection of PBS; the introduction of Aβ—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-42. GCL granular cell layer, SGZ subgranular zone

In basal progenitor cells expressing Pax6, no significant differences were found between groups of animals with and without spatial training in rats with simulated AD and control animals [F(1.24) = 0.04, p = 0.8431, two-way ANOVA] (Fig. 6c).

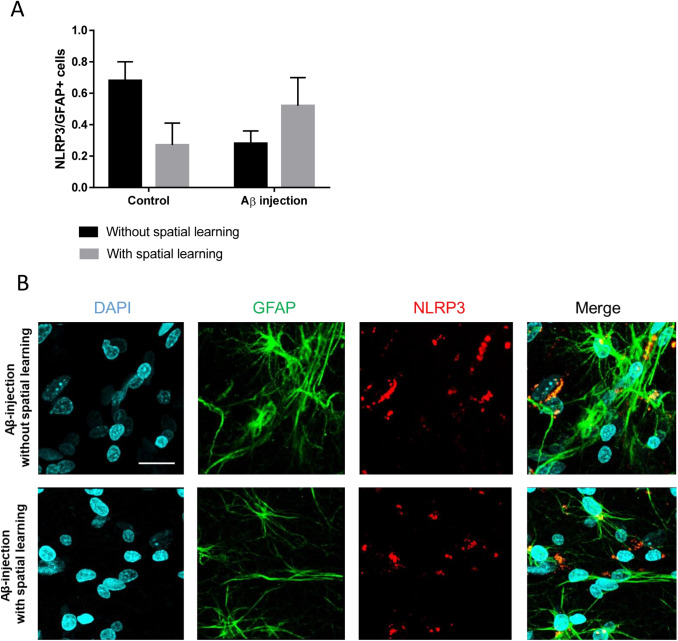

When assessing the expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in GFAP-immunopositive cells, a significant effect of the interaction of two factors (spatial learning in MWM and operation) was recorded [F(1.24) = 5.804, p = 0.024, two-way ANOVA] (Fig. 8a, b).

Fig. 8.

Expression of NLRP3 inflammasome in GFAP+ cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. a The number of cells that colocalize GFAP and NLRP3 pro fields of view. Data are presented as a mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA. b Immunohistochemical staining of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Tipple immunofluorescent staining: expression of GFAP (green), expression of NLRP3 (red), DAPI (blue), and signal overlay (merge). Scale bar 25 µm. GCL granular cell layer, SGZ subgranular zone. Scale bar 20 µm. Aβ injection—rats with the injection of soluble forms of beta-amyloid 1-s42

Discussion

Neuroinflammation is always considered as a factor negatively affecting cognitive functions in humans and in laboratory animals. Particularly, inflammations are reported to be linked to cognitive decline and age-related dementia (Sartori et al. 2012; Marsland et al. 2015), post-operative cognitive dysfunction (Alam et al. 2018), and Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration (Nazem et al. 2015; Ardura-Fabregat et al. 2017). However, very recent data suggest that the link between neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity might be much more complex. Even the factors that have been considered as anti-inflammatory and able to restore cognitive functions (Chupel et al. 2017) may demonstrate their pro-inflammatory potential (Sloan et al. 2018).

Spatial learning is a well-known procedure stimulating hippocampal adult neurogenesis by means of preserved survival of immature neurons (Epp et al. 2011). However, some controversial data remain. Spatial training in the MWM affects the formation and further fate of the newborn cells. It was previously described that in healthy rats, training caused an increase in the survival rate of newborn neurons in the DG of the hippocampus (Gould et al. 1999), but stimulation of neurogenesis by spatial learning depends on the type of task (Leuner and Gould 2010), the quality of training, the difficulty of the task, and/or the age of the cells during exposure (Epp et al. 2013). In elderly rats, spatial training in the MWM contributes to the survival of relatively mature neurons, apoptosis of immature cells and, finally, proliferation of neuronal progenitors (Dupret et al. 2007). However, it should be taken into consideration that gradual removal of older proliferating hippocampal new rat neurons following spatial learning occurs due to a competitive interaction with a population of younger proliferating neurons (Epp et al. 2011).

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of spatial learning on SGZ neurogenesis in control rats and in rats with Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration. In sham-operated and Aβ-injected rats, spatial learning resulted in reduction in the number of GFAP-immunopositive cells. Spatial learning-induced suppression GFAP expression might be attributed either to aberrant proliferation of astrocyte progenitors (Sakurai and Osumi 2008) or to reduction of stem cells renewal (Sansom et al. 2009). As it was shown before, reduced expression GFAP could lead to a depletion of stem cells pool due to increased early neurogenesis and loss of self-renewal capacity of stem cells (Sansom et al. 2009). Thus, we may assume that spatial learning stimulates early stages of neurogenesis at the cost of astroglial progenitors’ proliferation and differentiation. We should note that our data do not agree with previously obtained results demonstrating loss of training-induced effects on migrating neuroblasts together with appearance of training-induced action on astrocytes number (Zeng et al. 2016). Such controversy might be explained by differences in the time-course of spatial learning protocol administration.

The number of PSA-NCAM-immunopositive neuroblasts diminished by Aβ injection was completely restored by subsequent spatial learning. The latter was similar to the changes observed in the expression of CD133 in the affected brains (decreased expression in Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration and restored levels in the spatial learning Aβ-treated group). Since CD133 (prominin-1) plays a role in the control of stem cell maintenance (self-renewal) and asymmetric stem cell divisions in neurogenic niches (Okano and Sawamoto 2008), Aβ-affected SGZ is characterized by the loss of stem/progenitor cells, abnormal self-renewal of remaining NSCs associated with suppressed neurogenesis and elevated proliferation of astroglial progenitors. In addition to the effects observed in sham-operated animals, where spatial learning stimulated early neurogenesis and reduced astrogliogenesis, in Aβ-induced neurodegeneration spatial learning was able to restore the NSCs pool. It is known that NSCs in the adult brain can move between the state of quiescence, are able to exit quiescence, rapidly expand and differentiate. The quiescent state of stem cells is defined as the non-proliferating state of cells that carry the potential of progenitor cells. Often corresponding to the state of G0, characterized by the lack of expression of proliferation markers, it is often called non-proliferating, but nonetheless cell-competent for proliferation (Than-Trong et al. 2018). In a healthy brain (in the control group), spatial learning leads to an increase in specifically activated NSCs able to actively divide, thus providing effective neurogenesis in the adult brain.

Reduction in PSA-NCAM+ cells number in Aβ-treated rats was very reasonable and well consistent with data obtained in (Murray et al. 2016), thereby suggesting impairment of newly-formed neurons migration in Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration. It is also consistent with previous data obtained in rats subjected to Aβ1-42 injection when spatial training contributed to the short-term survival of newly-formed cells, increased proliferation, and worsened the long-term cell survival (Zeng et al. 2016). Thus, spatial learning may rescue SGZ neurogenesis impaired by Aβ toxicity by preserving the stem cells pool, promoting predominant proliferation and differentiation of neuronal, but not astroglial, progenitors, thereby facilitating migration of progenitor cells from the SGZ to the granular layer of hippocampus.

Then, we demonstrated for the first time that spatial training increased expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the SGZ in sham-operated, but not in Aβ-treated, rats. Particularly, two pools of cells—CD133+ (stem cells) and PSA-NCAM+ (neuronal-restricted precursors)—started to express NLRP3 in control rats after spatial learning. Another interesting observation was a reduction NLRP3 expression in PSA-NCAM+ cells after Aβ injection compared to sham-operated group without spatial learning. However, these findings come in contrast to other in vivo and in vitro studies which reported that Aβ administration induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Wang et al. 2017). It is well known that Aβ induced microglia activation and mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with ROS accumulation and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Importantly, Aβ induced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release in microglia (Wang et al. 2017). Compelling evidence suggests that neuroinflammation stimulated by microglia, the resident macrophage-like immune cells in the brain, play a contributing role in the pathogenesis of AD. The nuclear factor-kappa B and NLRP3 inflammasome activation by P2X7/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathways are closely linked to AD via neuroinflammation (Thawkar and Kaur 2019). Thus, NLRP3 expression has mainly been studied in microglia, astrocytes and mature neurons (Li et al. 2017). The nature and role of inflammasome expression in NSCs and neuroblasts remains unexplored.

In our study, results were obtained showing a decrease in the expression of NLRP3 by NPCs (Nestin+) and neuroblasts (PSA-NCAM+) after Aβ-injection. Our research proved the role of this NLRP3 protein complex in the proliferation and expansion of hematopoietic stem progenitor cells (Chernykh et al. 2018). On the molecular level, the NLRP3 inflammasome is triggered in cells not only in response to DAMPs-mediated calcium influx or potassium efflux, but, more interestingly and recently proposed in the case of human T lymphocytes, in response to glucose changes and absorption of amino acids. This discovery establishes an additional role for the NLRP3 inflammasome as a sensor of metabolic activity in immune cells and possibly also in hematopoietic stem progenitor cells. Thus, it is logical to assume that, similar to hematopoietic stem cells, in NPCs, inflammasomes act as a sensor for proliferation and differentiation. NLRP3 inflammasome can promote cell differentiation. Accordingly, low expression leads to reduced differentiation of neurons and the glia formation in AD. At the same time, pathological enhancement of inflammasome expression accompanies neuroinflammation associated with neurodegeneration.

NLRP3 inflammasomes are known to be involved in the maturation of pro-inflammatory interleukin-1β (Song et al. 2017). IL-1β plays a critical role in the formation of memory-dependent hippocampus. Thus, the release of IL-1β is activated through the formation of associative memory (Goshen et al. 2007) and LTP (del Rey et al. 2013). Also, the role of IL-1β in neuronal migration during brain development was described recently (Ma et al. 2014). There is a compelling evidence that inflammation-associated cytokines play a key role in stimulating neurite outgrowth and regeneration. Recent studies have provided that IL-1β is able to stimulate the migration of cultured cortical neurons, and the potent neurotropic action of IL-1β leads to rapid neurite growth. In addition, stimulation with IL-1β was found to facilitate neurite outgrowth, as well as increase the expression levels of neuronal factors, such as NT3 and Ngn1. Moreover, IL-1β-induced Wnt5a expression plays a crucial role in neuronal differentiation of NPCs. These results demonstrate a novel physiological function of IL-1β in neuronal differentiation of cortical NPCs (Park et al. 2018).

It is known that in NLRP3−/− or caspase-1−/− mice carrying mutations associated with familiar AD were largely protected from loss of spatial memory and other AD-associated sequelae and demonstrated reduced brain caspase-1 and IL-1β activation as well as enhanced Aβ clearance (Heneka et al. 2013). Therefore, it would be reasonable to assume that spatial training can lead to a reduction in the expression of inflammasome in the brain. However, we did not record such changes after beta-amyloid injection, which may be due to insufficient training, the severity of brain damage, as well as the other non-developmental neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration functions of inflammasomes. Such assumptions were based on the results obtained in the group of sham-operated animals: an increase in the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroblasts after spatial training. Therefore, increase in the expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the brain of control animals after spatial training may be associated with the participation of this type of inflammasome in processes that are activated during memorizing and searching for a platform in the Morris water maze.

Accordingly, the increase in the expression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the normal brain after spatial training may be associated with the possible role of this multiprotein complex in the processes of neurogenesis, memorization, and learning.

Conclusion

In sum, Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration is characterized by reduced proliferation of SGZ cells, suppressed recruiting of NSCs/NPCs, and diminished number of neuroblasts. Stimulation of neurogenesis in the spatial learning protocol is effective in the complete restoration of stem cells and neuroblasts number in the SGZ affected by Aβ1-42 treatment, as well as in the reduction of GFAP expression.

CD133+, Nestin and PSA-NCAM+ cells of the SGZ are able to express NLRP3 inflammasomes in the conditions of stimulated neurogenesis (spatial learning). At the same time, expression of NLRP3 in the SGZ cells could not serve as a marker of neuroinflammation associated with the progression of Alzheimer’s type neurodegeneration. However, the spatial learning-induced hyperexpression of NLRP3 inflammasomes in PSA-NCAM+ neuroblasts is dramatically reduced in the SGZ affected by Aβ1-42 treatment in vivo.

Therefore, we found for the first time that learning contributes to an increase in the inflammasome expression in neuroblasts in neurogenic niches. Given the evidence that maintaining a pool of neuroblasts and their ability to effectively mobilize are relevant to the memory formation, it is highly likely that spatial training is accompanied by inflammasome expression in the cells of neurogenic niches. Neurodegeneration leads to disruption of this mechanism. Taken together, this suggests that the cell-mediated signaling pathways in neuroblasts mediated by the activity of inflammasome could accompany neurogenesis-supported memory.

Acknowledgements

We thank Assoc. Prof. Oksana Gavrilyuk and Assist. Prof. Ekaterina Andryushkina (International Programs Center, KrasSMU) for their assistance with proofreading. This work was supported by a grant from the President of the Russian Federation for State support of the leading scientific schools of the Russian Federation 6240.2018.7 and 2547.2020.7.

Author Contributions

YK, AS designed the study; YK, OL, YG, AC, LT, EV, EKh, EZh, LS, NM performed the experiments; YK and AS wrote the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the paper.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alam A, Hana Z, Jin Z, Suen KC, Ma D (2018) Surgery, neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment. EBioMedicine 37:547–556. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple DM, Fonseca RS, Kokovay E (2017) The role of adult neurogenesis in psychiatric and cognitive disorders. Brain Res 1655:270–276. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardura-Fabregat A, Boddeke EWGM, Boza-Serrano A, Brioschi S, Castro-Gomez S, Ceyzériat K, Dansokho C, Dierkes T, Gelders G, Heneka MT, Hoeijmakers L, Hoffmann A, Iaccarino L, Jahnert S, Kuhbandner K, Landreth G, Lonnemann N, Löschmann PA, McManus RM, Paulus A, Reemst K, Sanchez-Caro JM, Tiberi A, Van der Perren A, Vautheny A, Venegas C, Webers A, Weydt P, Wijasa TS, Xiang X, Yang Y (2017) Targeting neuroinflammation to treat Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 31(12):1057–1082. 10.1007/s40263-017-0483-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf A, Mahmoud PA, Reda H, Mansour S, Helal MH, Michel HE, Nasr M (2019) Silymarin and silymarin nanoparticles guard against chronic unpredictable mild stress induced depressive-like behavior in mice: involvement of neurogenesis and NLRP3 inflammasome. J Psychopharmacol 33(5):615–631. 10.1177/0269881119836221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglietto-Vargas D, Sánchez-Mejias E, Navarro V, Jimenez S, Trujillo-Estrada L, Gómez-Arboledas A, Sánchez-Mico M, Sánchez-Varo R, Vizuete M, Dávila JC, García-Verdugo JM, Vitorica J, Gutierrez A (2017) Dual roles of Aβ in proliferative processes in an amyloidogenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 7(1):10085. 10.1038/s41598-017-10353-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese AC, Hamblin MH, Lee J-P (2020) Neural stem cell therapy for neurovascular injury in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol 324:113112. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.113112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetin F, Dincer S (2007) The effect of intrahippocampal beta amyloid (1–42) peptide injection on oxidant and antioxidant status in rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1100(1):510–517. 10.1196/annals.1395.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EWL, Krishnansamy S, Wong C, Gan SY (2019) The NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in the neuroprotective mechanism of neural stem cells against microglia-mediated toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells via the attenuation of tau hyperphosphorylation and amyloidogenesis. NeuroToxicol 70:91–98. 10.1016/j.neuro.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernykh AI, Komleva YuK, Gorina Ya.V., Lopatina OL, Pashchenko S.I., Salmina AB, (2018) Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular astroglia and CD133+ endothelial cell precursor cells in Alzheimer’s disease modeling in mice. Fundam Clin Med 3:6–15 [Google Scholar]

- Chugh D, Nilsson P, Afjei S-A, Bakochi A, Ekdahl CT (2013) Brain inflammation induces post-synaptic changes during early synapse formation in adult-born hippocampal neurons. Exp Neurol 250:176–188. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chupel MU, Direito F, Furtado GE, Minuzzi LG, Pedrosa FM, Colado JC, Ferreira JP, Filaire E, Teixeira AM (2017) Strength training decreases inflammation and increases cognition and physical fitness in older women with cognitive impairment. Front Physiol 8:377. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover JC, Notti RQ (2008) The neural stem cell niche. Cell Tissue Res 331(1):211–224. 10.1007/s00441-007-0503-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope EC, Gould E (2019) Adult neurogenesis, glia, and the extracellular matrix. Cell Stem Cell 24(5):690–705. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rey A, Balschun D, Wetzel W, Randolf A, Besedovsky HO (2013) A cytokine network involving brain-borne IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-18, IL-6, and TNFα operates during long-term potentiation and learning. Brain Behav Immun 33:15–23. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R-H, Wu F-F, Lu M, Shu X, Ding J-H, Wu G, Hu G (2016) Uncoupling protein 2 modulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in astrocytes and its implications in depression. Redox Biol 9:178–187. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupret D, Fabre A, Döbrössy MD, Panatier A, Rodríguez JJ, Lamarque S, Lemaire V, Oliet SHR, Piazza P-V, Abrous DN (2007) Spatial learning depends on both the addition and removal of new hippocampal neurons. PLoS Biol 5(8):e214. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelbaum S, Youssef I, Lacor PN, Chaurand P, Duplus E, Brugg B, Duyckaerts C, Delatour B (2015) Acute amnestic encephalopathy in amyloid-β oligomer–injected mice is due to their widespread diffusion in vivo. Neurobiol Aging 36(6):2043–2052. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp JR, Chow C, Galea LAM (2013) Hippocampus-dependent learning influences hippocampal neurogenesis. Front Neurosci. 10.3389/fnins.2013.00057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epp JR, Haack AK, Galea LAM (2011) Activation and survival of immature neurons in the dentate gyrus with spatial memory is dependent on time of exposure to spatial learning and age of cells at examination. Neurobiol Learn Mem 95(3):316–325. 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L-W, Pang Y (2017) Dysregulation of neurogenesis by neuroinflammation: key differences in neurodevelopmental and neurological disorders. Neural Regen Res 12(3):366. 10.4103/1673-5374.202926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Lu M, Qiao C, Zhou Y, Ding J-H, Hu G (2016) MicroRNA-7 enhances subventricular zone neurogenesis by inhibiting NLRP3/caspase-1 axis in adult neural stem cells. Mol Neurobiol 53(10):7057–7069. 10.1007/s12035-015-9620-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Ting JP-Y (2016) The pathogenic role of the inflammasome in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem 136:29–38. 10.1111/jnc.13217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JS, Hirschi KK (2009) Diverse roles of the vasculature within the neural stem cell niche. Regen Med 4(6):879–897. 10.2217/rme.09.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshen I, Kreisel T, Ounallah-Saad H, Renbaum P, Zalzstein Y, Ben-Hur T, Levy-Lahad E, Yirmiya R (2007) A dual role for interleukin-1 in hippocampal-dependent memory processes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32(8–10):1106–1115. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, Reeves A, Shors TJ (1999) Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal formation. Nat Neurosci 2(3):260–265. 10.1038/6365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HF, Nolan YM (2012) Unlocking mechanisms in interleukin-1β-induced changes in hippocampal neurogenesis—a role for GSK-3β and TLX. Transl Psychiatry 2(11):e194–e194. 10.1038/tp.2012.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng T-C, Gelpi E, Halle A, Korte M, Latz E, Golenbock DT (2013) NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493(7434):674–678. 10.1038/nature11729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komleva YK, Malinovskaya GorinaLopatina, Volkova, Salmina NAVYOLVVAB (2015) Expression of CD38 and CD157 molecules in olfactory brain bulbs in experimental Alzheimer’s disease. Sib Med Rev 5:44–49 [Google Scholar]

- Komleva YK, Lopatina OL, YaV G, Chernykh AI, Shuvaev AN, Salmina AB (2018) Early changes in hyppocampal neurogenesis induced by soluble Ab1-42 oligomers. Biomed Khim 64(4):326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-M, Kim J-J, Kim HJ, Shong M, Ku BJ, Jo E-K (2013) Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 62(1):194–204. 10.2337/db12-0420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesné SE, Sherman MA, Grant M, Kuskowski M, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Ashe KH (2013) Brain amyloid-β oligomers in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 136(5):1383–1398. 10.1093/brain/awt062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuner B, Gould E (2010) Structural plasticity and hippocampal function. Annu Rev Psychol 61(1):111–140. 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Wang L, Hu Q, Liu S, Bai X, Xie Y, Zhang T, Bo S, Gao X, Wu S, Li G, Wang Z (2017) Neuroprotective roles of l-cysteine in attenuating early brain injury and improving synaptic density via the CBS/H2S pathway following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Front Neurol 8:176. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly PTT, Cai F, Song W (2011) Detection of neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. JoVE 53:2831. 10.3791/2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Li X, Zhang S, Yang F, Zhu G, Yuan X, Jiang W (2014) Interleukin-1 beta guides the migration of cortical neurons. J Neuroinflam 11(1):114. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsland AL, Gianaros PJ, Kuan DC-H, Sheu LK, Krajina K, Manuck SB (2015) Brain morphology links systemic inflammation to cognitive function in midlife adults. Brain Behav Immun 48:195–204. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray HC, Low VF, Swanson MEV, Dieriks BV, Turner C, Faull RLM, Curtis MA (2016) Distribution of PSA-NCAM in normal, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease human brain. Neuroscience 330:359–375. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi A, Kaneko N, Takeda H, Sawasaki T, Morikawa S, Zhou W, Kurata M, Yamamoto T, Akbar SMF, Zako T, Masumoto J (2018) Amyloid β directly interacts with NLRP3 to initiate inflammasome activation: identification of an intrinsic NLRP3 ligand in a cell-free system. Inflamm Regen 38(1):27. 10.1186/s41232-018-0085-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazem A, Sankowski R, Bacher M, Al-Abed Y (2015) Rodent models of neuroinflammation for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 12(1):74. 10.1186/s12974-015-0291-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Sawamoto K (2008) Neural stem cells: involvement in adult neurogenesis and CNS repair. Philos Trans R Soc B 363(1500):2111–2122. 10.1098/rstb.2008.2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Wang D, Zhang X, Zhou D, Zhang H, Qian Q, He X, Liu Z, Liu Y, Zheng T, Zhang L, Wang M, Sun B (2016) Amyloid β is not the major factor accounting for impaired adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein. Stem Cell Rep 7(4):707–718. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-Y, Kang M-J, Han J-S (2018) Interleukin-1 beta promotes neuronal differentiation through the Wnt5a/RhoA/JNK pathway in cortical neural precursor cells. Mol Brain 11(1):39. 10.1186/s13041-018-0383-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ (2004) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates, compact, 2nd edn. Academic Press , Boston [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai K, Osumi N (2008) The neurogenesis-controlling factor, Pax 6, inhibits proliferation and promotes maturation in murine astrocytes. J Neurosci 28(18):4604–4612. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5074-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom SN, Griffiths DS, Faedo A, Kleinjan D-J, Ruan Y, Smith J, van Heyningen V, Rubenstein JL, Livesey FJ (2009) The level of the transcription factor Pax6 Is essential for controlling the balance between neural stem cell self-renewal and neurogenesis. PLoS Genet 5(6):e1000511. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori AC, Vance DE, Slater LZ, Crowe M (2012) The impact of inflammation on cognitive function in older adults: implications for healthcare practice and research. J Neurosci Nurs 44(4):206–217. 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182527690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P (2013) The laboratory rat: relating its age with human’s. Int J Prevent Med 4(6):624–630 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B-Z, Xu Z-Q, Han B-Z, Su D-F, Liu C (2015) NLRP3 inflammasome and its inhibitors: a review. Front Pharmacol. 10.3389/fphar.2015.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, McKinley PS, Bartels M, Shimbo D, Lauriola V, Karmally W, Pavlicova M, Choi CJ, Choo T, Scodes JM, Flood P, Tracey KJ (2018) Aerobic exercise training and inducible inflammation: results of a randomized controlled trial in healthy. J Am Heart Assoc Young Adults. 10.1161/JAHA.118.010201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Pei L, Yao S, Wu Y, Shang Y (2017) NLRP3 inflammasome in neurological diseases, from functions to therapies. Front Cell Neurosci. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Than-Trong E, Ortica-Gatti S, Mella S, Nepal C, Alunni A, Bally-Cuif L (2018) Neural stem cell quiescence and stemness are molecularly distinct outputs of the Notch3 signalling cascade in the vertebrate adult brain. Development. 10.1242/dev.161034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thawkar BS, Kaur G (2019) Inhibitors of NF-κB and P2X7/NLRP3/caspase 1 pathway in microglia: Novel therapeutic opportunities in neuroinflammation induced early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol 326:62–74. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees CV, Williams MT (2006) Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc 1(2):848–858. 10.1038/nprot.2006.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H-M, Zhang T, Huang J-K, Xiang J-Y, Chen J, Fu J-L, Zhao Y-W (2017) Edaravone attenuates the proinflammatory response in amyloid-β-treated microglia by Inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β secretion. Cell Physiol Biochem 43(3):1113–1125. 10.1159/000481753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Hu Q, Li M, Wang S, Zhang L, Chen Y, Li L (2008) Pax6 directly modulate Sox2 expression in the neural progenitor cells. NeuroReport 19(4):413–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MD, Montgomery SL, Rivera-Escalera F, Olschowka JA, O’Banion MK (2013) Sustained IL-1β expression impairs adult hippocampal neurogenesis independent of IL-1 signaling in nestin+ neural precursor cells. Brain Behav Immun 32:9–18. 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung ST, Martinez-Coria H, Ager RR, Rodriguez-Ortiz CJ, Baglietto-Vargas D, LaFerla FM (2015) Repeated cognitive stimulation alleviates memory impairments in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Brain Res Bull 117:10–15. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J, Zhao F, Chojnacki JE, Fulp J, Klein WL, Zhang S, Zhu X (2018) NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor ameliorates amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 55(3):1977–1987. 10.1007/s12035-017-0467-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z, Gonzalez-Martinez J, Tilelli C, Bingaman W, Najm I (2005) Expression of neural stem cell surface marker CD133 in balloon cells of human focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia 46(11):1716–1723. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00276.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Jiang X, Hu X-F, Ma R-H, Chai G-S, Sun D-S, Xu Z-P, Li L, Bao J, Feng Q, Hu Y, Chu J, Chai D, Hong X-Y, Wang J-Z, Liu G-P (2016) Spatial training promotes short-term survival and neuron-like differentiation of newborn cells in Aβ 1–42 -injected rats. Neurobiol Aging 45:64–75. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Jiao J (2015) Molecular biomarkers for embryonic and adult neural stem cell and neurogenesis. Biomed Res Int 2015:1–14. 10.1155/2015/727542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]