Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) has been reported to be expressed in spinal astrocytes and is involved in neuropathic pain. In this study, we investigated the role and mechanism of TRAF6 in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA)-evoked chronic inflammatory hypersensitivity and the effect of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) on TRAF6 expression and inflammatory pain. We found that TRAF6 was dominantly increased in microglia at the spinal level after intraplantar injection of CFA. Intrathecal TRAF6 siRNA alleviated CFA-triggered allodynia and reversed the upregulation of IBA-1 (microglia marker). In addition, intrathecal administration of DHA inhibited CFA-induced upregulation of TRAF6 and IBA-1 in the spinal cord and attenuated CFA-evoked mechanical allodynia. Furthermore, DHA prevented lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-caused increase of TRAF6 and IBA-1 in both BV2 cell line and primary cultured microglia. Finally, intrathecal DHA reduced LPS-induced upregulation of spinal TRAF6 and IBA-1, and alleviated LPS-induced mechanical allodynia. Our findings indicate that TRAF6 contributes to pain hypersensitivity via regulating microglial activation in the spinal dorsal horn. Direct inhibition of TRAF6 by siRNA or indirect inhibition by DHA may have therapeutic effects on chronic inflammatory pain.

Keywords: TRAF6, Microglia, CFA, Inflammatory pain, DHA

Introduction

Chronic pain is common clinically and manifested as persistent nociceptive hypersensitivities including an obvious reduction in thresholds required to evoke pain (allodynia) and enhanced responses to noxious stimuli at the site of injury and adjacent tissues (hyperalgesia). Chronic inflammatory pain is often caused by peripheral tissue damage and persistent inflammation (Svensson et al. 2007; Ji et al. 2014; Xiang et al. 2019). Currently, such pain is generally treated with cyclooxygenase inhibitors, anti-depressants, and anti-convulsants. However, these drugs are often accompanied by gastrointestinal discomfort and other side effects (Marret et al. 2005; Nakamoto et al. 2013).

Spinal glial cells (astrocytes and microglia) play a vital role in the initiation and maintenance of pathological pain (Gao and Ji 2010; Watkins et al. 2007; Cao and Zhang 2008; Gosselin et al. 2010; Ji et al. 2013). Nerve injury or tissue inflammation induces the activation of glial cells which release proinflammatory mediators including cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6), chemokines (such as CCL2, CXCL1, and CX3CL1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) to increase neuronal excitability or synaptic transmission (Li et al. 2016; Song et al. 2016; Dou et al. 2018; Zhu et al. 2014; Sukhotnik et al. 2016). Accumulating evidence has shown that intrathecal delivery of microglial inhibitor minocycline exerted anti-nociceptive effect in animal models of chronic pain including inflammatory pain, visceral pain, neuropathic pain, and cancer pain (Mohammadi et al. 2020; Starobova et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2017; Li et al. 2016; Song et al. 2016). However, the mechanisms underlying microglial activation under inflammatory pain conditions are not fully understood.

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor (TRAF) protein family has 6 members (TRAF1-6) in mammals (Arch et al. 1998; Bradley and Pober 2001), of which TRAF6 has special facture and biological function (Dou et al. 2018). TRAF6 plays an essential role in the regulation of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated signaling pathway (Walsh et al. 2015; Xing et al. 2017). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a typical agonist to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and extensively utilized as a microglial activator to evoke a neuroinflammatory response (Zhu et al. 2014). Interaction between LPS and TLR4 leads to the formation of an LPS signaling complex containing some surface molecules, including myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88, toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon β (TRIF), as well as TRAF6, which then cause the activation of the inflammatory response (Wang et al. 2018a; Sukhotnik et al. 2016). Meanwhile, intrathecal or systemic administration of LPS induces microglial activation and pain hypersensitivity (Hsieh et al. 2018; Hashemi-Monfared et al. 2018). Peripheral injection of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) increases TLR4 expression and causes microglial activation in the spinal dorsal horn (Zhao et al. 2015). TRAF6 is distributed widely and abundantly in the CNS and contributes to the inflammatory reactions in stroke (Yan et al. 2020), traumatic brain injury (Chen et al. 2011), neurodegenerative diseases (Zhou et al. 2019), and neuropathic pain (Lu et al. 2014) and visceral pain (Weng et al. 2020). Whether TRAF6 is involved in chronic inflammatory pain and microglial activation remains to be investigated.

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), a predominant n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-3 PUFAs) originating from fish oils, is highly concentrated in the brain and the retina in humans (Nakamoto et al. 2010; Bazinet and Laye 2014). Aside from the guaranteed safety and efficacy as a nutritional supplement, DHA has been found to have many beneficial physiological effects, including anti-oxidant and anti-inflammation properties (Sun et al. 2018). Dietary supplementation with DHA is effective in various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and depression (Ajith 2018; Konigs and Kiliaan 2016; Natacci et al. 2018; Saunders et al. 2016). The role of DHA in neuroinflammation is exerted partially via its direct or indirect effect on microglia (De Smedt-Peyrusse et al. 2008; Orr et al. 2013). Recent studies have delineated that DHA possesses analgesic effect in response to neuropathic pain (Landa-Juarez et al. 2019) and visceral pain (Weng et al. 2020). Whether DHA has a role on chronic inflammatory pain and TRAF6 expression is interesting to be investigated.

In the current study, using a mouse model of CFA-induced inflammatory pain, we investigated the role of TRAF6 in chronic pain and microglial activation. We also evaluated the effects of DHA on chronic inflammatory pain and TRAF6 expression in cultured microglia and spinal cord.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Mouse Models of Inflammatory Pain

The current study used adult ICR mice (male, 8 weeks old) purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Nantong University. The mice were maintained on a 12:12 light–dark cycle with free access to food and water. The ambient environment was kept at a constant temperature (22 ± 2 ℃). The experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nantong University and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain. Inflammatory pain was established in mice by intraplantar administration of CFA (20 μL, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or intrathecal administration of LPS (100 ng, Sigma).

Drugs and Administration

Three small interfering RNAs (siRNA-1, 5′-GCC CAA ATA AAG GCT GTT T-3′; siRNA-2, 5′-TGT CCT CTG GCA AAT ATC A-3′; and siRNA-3, 5′-CTT ACA ATT CTC GAC CAG T-3′) targeting the sequence of mice TRAF6 (Gene Bank Accession, NM 001303273.1) and negative control siRNA (NC siRNA, 5′-TTC TCC GAA CGT GTC ACG T-3′) were synthesized by Guangzhou RiboBio (China). BV2 microglial cells were transfected with different siRNA oligonucleotides and the knockdown efficiency of the siRNAs was tested. The siRNA showed the best knockdown effect was modified with 5′-cholesteryl and 2′-O-methylribonucleotide to enhance its stability and delivery efficiency (RiboBio, China). DHA salt (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in saline. For intrathecal administration, the spinal cord puncture was made with a 30-gauge needle between the L4 and L5 levels to deliver the drug (10 μL) to the cerebral spinal fluid. Immediately after the needle entry into the subarachnoid space, a brisk tail-flick can be observed (Hylden and Wilcox 1980).

Behavioral Analysis

Animals were habituated to the testing environment daily for at least two days before testing the baseline. The temperature and humidity of the room were stable for all experiments. For testing mechanical allodynia, mice were put in the boxes on an elevated metal mesh floor and allowed 30 min for habituation before testing the pain behavior. The plantar surface of the hindpaw was stimulated using a series of von Frey hairs with logarithmically incrementing stiffness (0.02–2.56 g, Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL), presented perpendicular to the plantar surface (2–3 s for each hair, 3 min interval between the tests). The 50% paw withdrawal threshold was checked using the method of Dixon's up-down method (Dixon 1980).

Cell Culture and Treatment

BV2 microglial cells were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. BV2 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of 3 × 105 cells/cm2 and cultured in a medium consisting of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in high glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM). Primary microglial cells were cultured as described previously (Lu et al. 2013). In brief, the cerebral hemispheres (neonatal mice, P2) were isolated and triturated, and then filtered using a 100 μm nylon screen. All cells were plated into 75 cm2 flasks in a medium consisting of 10% FBS in high glucose DMEM. After 2 weeks, microglia were separated from all cells by shaking the flasks at 220 rpm for 4 h and then seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 3 × 105 cells/cm2. The DMEM was replaced with reduced serum medium (Opti-MEM, Invitrogen) before transfection or stimulation. Cells were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h. DHA (10 μM or 30 μM) or vehicle was added into medium 30 min before LPS incubation. One microgram siRNA mixed with 2.5 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) was given 24 h prior to incubation with LPS. After these treatments, the cells were collected for Real-time PCR or Western blot analysis.

Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the spinal cord or cultured cells using Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). The mRNA levels of TRAF6, IBA-1 (ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1), and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were examined. The cDNA was amplified using the following primers, TRAF6 forward, 5′-TCA TTA TGA TCT GGA CTG CCC AAC -3′; TRAF6 reverse, 5′-TGC AAG TGT CGT GCC AAG TG-3′; IBA-1 forward, 5′-ATG AGC CAA AGC AGG GAT T-3′; IBA-1 reverse, 5′-CTT CAA GTT TGG ACG GCA G-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-AAA TGG TGA AGG TCG GTG TGA AC-3′; GAPDH reverse, 5′-CAA CAA TCT CCA CTT TGC CAC TG-3′. PCR reactions were performed using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (Takara) and were run on a Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument (Corbett Life Science). The PCR amplifications were performed at 95 ℃ for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of thermal cycling at 95 ℃ for 5 s and 60℃ for 45 s. The relative expression level for each target gene was normalized via the method of 2−△△Ct.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunocytochemistry

After deeply anesthetized, mice were perfused transcardially with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.16 M phosphate buffer (PB). After the perfusion, the L5 spinal cords were rapidly removed and post-fixed in the same fixative overnight. The sections of the spinal cord (30 μm, free-floating) were blocked with 2% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and then incubated overnight at 4℃ with the following primary antibodies: anti-TRAF6 (rabbit, 1:500, Abcam), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, mouse, 1:5000, Millipore), anti-IBA-1 (goat, 1:3000, Abcam). The sections were incubated for 1 h at RT with Cy3- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). For double immunofluorescence, spinal cord sections were incubated with a mixture of primary antibodies followed by a mixture of FITC- and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies.

For immunocytochemistry, cultured microglial cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min, and processed for immunofluorescence with anti-TRAF6 (rabbit, 1:500, Abcam) primary antibody and anti-IBA-1 (goat, 1:3000, Abcam) primary antibody as shown earlier. After immunostaining, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 0.1 μg/mL, Sigma) was added for 5 min at RT to stain all the cell nuclei.

Western Blot

For preparing protein samples, animals were transcardially perfused with PBS and the L5 spinal cords were dissected. Cells or spinal cords were homogenized in a lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma). BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used to check protein concentrations. Thirty microgram of total proteins were loaded for each lane and separated on SDS-PAGE gel (10% or 12%). After the transfer, the blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-TRAF6 (rabbit, 1:500, Abcam), anti-IBA-1 (goat, 1:500, Abcam). The blots were also incubated with the GAPDH antibody (mouse, 1:20,000, Sigma) for loading control. These blots were further incubated with IRDye 800 CW Donkey-anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) or IRDye 800 CW Donkey-anti-goat IgG (H + L) for 2 h at room temperature. These blots were examined with LI-COR Odyssey CLx Imaging System. Specific bands were evaluated by apparent molecular size.

Quantification and Statistics

All data in the present study were expressed as mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM). Differences between groups were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test or using Student’s t-test if only two groups were applied. For behavioral data, two-way repeated-measures (RM) ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test as the post hoc multiple comparison analysis was used. The analysis of microglia morphology in the spinal cord was performed as described previously (Young and Morrison 2018; Fernandez-Arjona et al. 2017). Five or six cells per animal were used for the quantification. For Western blot data, the density of specific bands was tested using Image J software. TRAF6 and IBA-1 levels were normalized to the loading control (GAPDH). Statistical analyses were done using Prism 8 (Graph Pad, San Diego, California) software. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TRAF6 Protein Level is Elevated in the Spinal Cord of Mice After CFA

Intraplantar administration of CFA leads to rapid and persistent inflammatory pain (Gao et al. 2010). We first investigated the spinal TRAF6 protein level in CFA pain model. At 3 and 7 days after CFA, the spinal cord was collected and TRAF6 protein level was analyzed. Western blot analysis revealed that CFA increased TRAF6 expression at Days 3 and 7, compared to the naive group (Day 3, P < 0.01; Day 7, P < 0.01, Fig. 1a, b). In addition, immunofluorescence staining showed that TRAF6 immunoreactivity (TRAF6-IR) had a very low basal level in naive animals (Fig. 1c), but was increased in the superficial lamina of ipsilateral spinal segments at Day 3 after CFA injection (Fig. 1d). Immunofluorescence intensity analysis showed that CFA significantly increased TRAF6-IR intensity, compared to naïve mice (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

CFA upregulates the protein expression of TRAF6 in the spinal cord. a, b Quantification of Western blot assay showed that TRAF6 protein level was increased in the L5 spinal cord of CFA mice at 3 and 7 days post-injection when compared to naïve mice. **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/group. c, d Immunohistochemistry showed the basal TRAF6-IR in naive mice (c) and increased TRAF6-IR in CFA mice (d). e The immunofluorescence intensity of TRAF6-IR showed that TRAF6 was significantly increased in the ipsilateral spinal cord at 3 days post-CFA when compared to naïve mice. ***P < 0.001. Student’s t-test. n = 3/group

TRAF6 is Primarily Localized in Spinal Microglia After CFA

To examine the cellular distribution of TRAF6 in the dorsal horn, we stained TRAF6 with microglia marker IBA-1 or astrocytic marker GFAP 3 days after CFA. The double staining results showed that TRAF6 was primarily co-localized with IBA-1 (Fig. 2a–c), but rarely with GFAP (Fig. 2d–f). Statistical analysis showed that 92.3% TRAF6-positive cells co-localized with IBA-1, whereas 5.1% TRAF6-positive cells co-localized with GFAP. These data indicate the predominant expression of TRAF6 in spinal microglia after CFA.

Fig. 2.

The cellular distribution of TRAF6 in the spinal cord after CFA. a–c Double staining showed that TRAF6-IR (a) was largely co-localized with microglia marker IBA-1 (b) in the L5 spinal dorsal horn at 3 days after CFA. d–f Double staining showed that few TRAF6-IR (d) was co-localized with astrocytic marker GFAP (e) in the L5 spinal dorsal horn at 3 days after CFA

TRAF6 is Increased by LPS in Primary Cultured Microglia

To further check whether TRAF6 was increased in microglia under inflammatory condition, primary cultured microglial cells were incubated with LPS followed by immunofluorescence staining. Immunostaining indicated a basal expression of TRAF6 (Fig. 3a) in the control microglia. Incubation with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 h increased the expression of TRAF6 (Fig. 3b, c), compared to the control group. LPS changed the morphology of most microglia from fusiform (Fig. 3d) to spherical (Fig. 3e) and increased the IBA-1 intensity (Fig. 3d–f). Double staining showed that the majority of IBA-1-IR cells in cultures expressed TRAF6 (Fig. 3g, h). These in vitro experiments indicate that LPS induces TRAF6 upregulation in microglia.

Fig. 3.

LPS increases TRAF6 and IBA-1 expression in primary microglia. a–c Immunostaining and the intensity analysis of TRAF6 showed that TRAF6 was constitutively expressed in control microglia (a) and increased by LPS incubation (b). **P < 0.01. Student’s t-test. n = 3/treatment. d–f Immunostaining and the intensity analysis of IBA-1 showed that IBA-1 was expressed in control microglia (d) and upregulated by LPS (e). ***P < 0.001. Student’s t-test. n = 3/treatment. g, h Triple staining of TRAF6, IBA-1, and DAPI (nuclear marker) showed that DAPI-positive cells also express TRAF6 and IBA-1 in control microglia (g) and LPS-incubated microglia (h)

Intrathecally Administration of TRAF6 siRNA Ameliorates CFA-Induced Mechanical Allodynia and Microglial Activation

We designed siRNAs targeting TRAF6 to determine the role of TRAF6 in CFA-induced pain hypersensitivity. We first checked the knockdown effect of siRNAs in BV2 cells. The qPCR results showed that, compared to NC siRNA, transfection with TRAF6 siRNA-1, siRNA-2, siRNA-3 reduced LPS-induced TRAF6 upregulation by 62.7%, 60.6%, and 69.5%, respectively (siRNA-1, P < 0.001; siRNA-2, P < 0.001; siRNA-3, P < 0.001, Fig. 4a), suggesting that TRAF6 siRNA-3 had the best knockdown effect. Western blot results also showed that TRAF6 siRNA-3 reduced LPS-induced TRAF6 upregulation by 41.1%, compared to the NC siRNA (P < 0.01, Fig. 4b). In addition, TRAF6 siRNA significantly reduced IBA-1 mRNA level (P < 0.001, vs. NC siRNA, Fig. 4c) as well as protein level (P < 0.05, vs. NC siRNA, Fig. 4d) in LPS-incubated BV2 cells. Based on these in vitro data, the TRAF6 siRNA-3 was then modified with 5′-cholesteryl and 2′-O-methylribonucleotide. The modified TRAF6 siRNA (5 μg/10 μL) or NC siRNA was intrathecally injected into the spinal cord 3 days after CFA when mechanical allodynia was fully developed. As shown in Fig. 4e, compared to the NC siRNA group, TRAF6 siRNA significantly attenuated CFA-induced pain response at 6 h and maintained till 48 h (treatment, F1,50 = 6.08 and P = 0.0334; time, F5,50 = 87.42 and P < 0.0001; interaction, F5,50 = 3.30 and P = 0.0119). Consistent with the behavioral data, qPCR results showed that TRAF6 siRNA reduced spinal TRAF6 mRNA level by 31.0 ± 7.7% at 6 h post-injection in CFA mice (P < 0.01, vs. NC siRNA, Fig. 4f). CFA-induced spinal IBA-1 mRNA upregulation was also reduced by TRAF6 siRNA (P < 0.05, Fig. 4g). Western blot further confirmed the inhibitory effect of TRAF6 siRNA on the protein levels of TRAF6 and IBA-1 in CFA mice (TRAF6, P < 0.05, Fig. 4h; IBA-1, P < 0.05, Fig. 4i). These data indicate that TRAF6 is obligatory for the maintenance of CFA-induced mechanical allodynia and the activation of spinal microglia.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of TRAF6 by TRAF6 siRNA attenuates CFA-induced mechanical allodynia and spinal microglial activation. a QPCR showed that all the three TRAF6 siRNA effectively knocked down the TRAF6 gene in LPS-incubated BV2 cells. TRAF6 siRNA-3 showed the best knockdown effect. ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. b Western blot assay showed that LPS-induced TRAF6 protein upregulation was inhibited by pretreatment with TRAF6 siRNA-3. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. c QPCR showed that TRAF6 siRNA transfection inhibited LPS-induced IBA-1 mRNA expression. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. d Western blot assay showed that TRAF6 siRNA transfection inhibited LPS-induced IBA-1 protein expression. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. e Intrathecal injection of TRAF6 siRNA (5 μg/10 μL) 3 days post-CFA significantly relieved CFA-induced mechanical allodynia, compared to the NC siRNA. NC, negative control siRNA. i.t., intrathecal injection. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Two-way RM ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 6/group. f, g QPCR results showed that intrathecal administration of TRAF6 siRNA significantly decreased the TRAF6 (f) and IBA-1 (g) mRNA levels in the spinal cord of CFA mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 5/group. h, i Western blot assay showed that intrathecal TRAF6 siRNA significantly decreased the TRAF6 (h) and IBA-1 (i) protein levels in the spinal cord of CFA mice. *P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 5/group

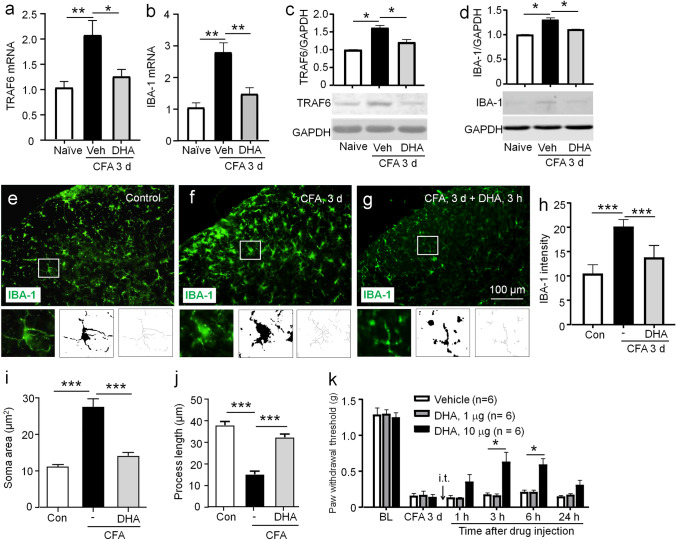

DHA Restrains CFA-Induced TRAF6 Expression, Microglial Activation, and Mechanical Allodynia

As DHA is a safe nutritional supplement, we then investigated whether DHA can reduce TRAF6 expression and attenuate chronic inflammatory pain. We intrathecally injected DHA (10 μg) 3 days after CFA injection and collected the spinal cords 3 h after DHA injection. QPCR showed that the mRNA level of TRAF6 was dramatically decreased by DHA (P < 0.05, Fig. 5a). CFA-induced IBA-1 mRNA upregulation was also reversed by DHA (P < 0.01, Fig. 5b). Western blot showed that the protein levels of TRAF6 and IBA-1 were also increased after CFA injection and decreased by DHA treatment (TRAF6, P < 0.05, Fig. 5c; IBA-1, P < 0.05, Fig. 5d). The role of DHA in CFA-induced microglial activation was further checked using immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5e–g). Compared to the control group (Fig. 5e), the microglia appeared to have extensively branched processes and hypertrophy of the cell body in the CFA group (Fig. 5f). DHA treatment reversed CFA-induced the reactive state of microglia (Fig. 5g). The IBA-1-IF intensity was reduced by 35.3 ± 3.7% in DHA + CFA mice, compared to CFA (P < 0.001, Fig. 5h). Quantification of morphological parameters showed that compared to control, CFA increased the microglia soma area and reduced process length in the spinal cord dorsal horn, which was reversed by intrathecal DHA (P < 0.001, Fig. 5i; P < 0.001, Fig. 5j). We then examined the anti-hyperalgesia effect of DHA on CFA-induced pain. Compared to vehicle, DHA (10 μg) significantly attenuated mechanical allodynia at 3 h and maintained till 6 h, but a lower dose of DHA (1 μg) has no obvious anti-allodynia effect at all the time points (treatment, F1,50 = 16.16 and P = 0.0024; time, F5,50 = 96.78 and P < 0.0001; interaction, F5,50 = 6.685 and P < 0.0001, Fig. 5k). These results indicate that DHA treatment suppresses spinal TRAF6 upregulation and microglial activation, and attenuates pain hypersensitivity induced by CFA.

Fig. 5.

DHA inhibits CFA-induced TRAF6 expression and microglial activation as well as mechanical allodynia. a, b QPCR assay showed that DHA treatment significantly downregulated the mRNA expressions of TRAF6 (a) and IBA-1 (b) in the L5 spinal cord of CFA mice, compared to vehicle. Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 5/group. c, d Western blot assay showed that DHA significantly reduced the protein expressions of TRAF6 (c) and IBA-1 (d) in the spinal cord of CFA mice, compared to vehicle. Veh, vehicle. *P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. e–g The immunohistochemistry showed that DHA treatment significantly decreased IBA-1 expression in the spinal dorsal horn of CFA mice. The insets showed the magnified fluorescent, binary, and skeletonized images of cropped cell corresponding to the white box. h IBA-1 intensity analysis. ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/group. i, j Microglia morphological analysis showed that DHA reversed CFA-induced upregulation of IBA-1-positive cell area (i) and reduction of process length (j). n = 5 or 6 cells/animal. k Intrathecal injection of DHA at the dose of 1 μg 3 days after CFA did not affect the pain threshold, whereas DHA at the dose of 10 μg attenuated mechanical allodynia at 3 h and 6 h post-injection. i.t., intrathecal injection. *P < 0.05. Two-way RM ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 6/group

DHA Inhibits LPS-Induced TRAF6 Expression and Microglial Activation in Cultured Microglia

Next, we investigated the effect of DHA on TRAF6 expression in cultured microglia under inflammatory condition. BV2 microglial cells were pretreated with different concentrations of DHA for 30 min and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for another 6 h. The concentration of DHA was similar to that in our previous study (Lu et al. 2013). QPCR data showed that DHA reduced TRAF6 mRNA expression by 48.0% and 56.0% at the doses of 10 μM and 30 μM, respectively (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, Fig. 6a). DHA also reduced IBA-1 mRNA level by 19.7% and 28.4% at the doses of 10 μM and 30 μM, respectively (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, Fig. 6b). Western blot further confirmed the reduction of TRAF6 and IBA-1 protein level by DHA (TRAF6, P < 0.05, Fig. 6c; IBA-1, P < 0.05, Fig. 6d). As BV2 cells partially model primary microglia (Horvath et al. 2008), we further investigated whether DHA had a similar effect in primary microglia. The primary cultured microglia were pretreated with DHA (30 μM) for 30 min, and then stimulated with LPS for 6 h. Preincubation with DHA significantly inhibited LPS-induced enhancement of TRAF6 mRNA and IBA-1 mRNA by 37.3% and 43.2%, respectively (TRAF6, P < 0.05, Fig. 6e; IBA-1, P < 0.05, Fig. 6f). These data indicate the inhibitory effect of DHA on LPS-triggered TRAF6 expression and microglial activation in vitro.

Fig. 6.

DHA decreases LPS-induced TRAF6 and IBA-1 expression in cultured microglia. a, b QPCR assay showed that DHA suppressed LPS-induced mRNA upregulations of TRAF6 (a) and IBA-1 (b) in BV2 cells. Cells were pretreated with DHA (3 or 30 μM) for 30 min and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. c, d Western blot assay showed that DHA suppressed LPS-induced protein upregulations of TRAF6 (c) and IBA-1 (d) in BV2 cells. Cells were pretreated with DHA (3 or 30 μM) for 30 min and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h. *P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment. e, f QPCR assay showed that DHA inhibited LPS-induced mRNA upregulations of TRAF6 (e) and IBA-1 (f) in primary microglia. Cells were pretreated with DHA (30 μM) for 30 min and then incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 6 h. *P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 3/treatment

DHA Restrains LPS-Induced Mechanical Allodynia, TRAF6 Expression, and Microglial Activation in the Spinal Cord

We then checked the role of DHA in LPS-induced pain model. Behavioral results showed that pretreatment with intrathecal DHA (10 μg) obviously enhanced the pain thresholds from 1 to 6 h after intrathecal LPS (treatment, F2,60 = 81.25 and P < 0.0001; time, F4,60 = 45.35 and P < 0.0001; interaction, F8,60 = 2.12 and P < 0.0001, Fig. 7a). To determine the role of DHA on the expressions of TRAF6 and IBA-1 in the spinal cord after intrathecal LPS, we did qPCR and Western blot analysis. The data showed that intrathecal LPS enhanced TRAF6 mRNA and IBA-1 mRNA in the spinal cord, which were suppressed by the pretreatment with DHA (TRAF6 mRNA, P < 0.05, Fig. 7b; IBA-1 mRNA, P < 0.05, Fig. 7c). DHA also reduced LPS-induced upregulation of TRAF6 protein and IBA-1 protein level (TRAF6 protein, P < 0.05, Fig. 7d; IBA-1 protein, P < 0.05, Fig. 7e). These results indicate that DHA decreases LPS-induced mechanical allodynia, TRAF6 expression, and microglial activation in the spinal cord.

Fig. 7.

DHA prevents LPS-induced pain hypersensitivity, TRAF6 upregulation, and microglial activation in the spinal cord. a Pretreatment with intrathecal DHA (10 μg) enhanced the pain thresholds at 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h after intrathecal LPS. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Two-way RM ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 6/group. b, c QPCR assay showed that DHA significantly reduced the expressions of TRAF6 mRNA (b) and IBA-1 mRNA (c) in LPS-treated mice. *P < 0.05. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 5/group. d, e Western blot assay showed that DHA significantly reduced the expressions of TRAF6 protein (d) and IBA-1 protein (e) in LPS-treated mice. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. One-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. n = 5/group

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that TRAF6 was significantly increased in the spinal cord and predominantly expressed in microglial cells after CFA injection. Importantly, knockdown of the spinal TRAF6 by siRNA attenuated CFA-induced pain hypersensitivity and spinal microglial activation. In addition, intrathecal administration of DHA markedly reduced pain hypersensitivity and inhibited TRAF6 upregulation as well as microglial activation in the spinal cord. In vitro data showed that DHA inhibited LPS-induced upregulation of TRAF6 and IBA-1 in both BV2 cells and primary microglial cells. In vivo data showed that pretreatment with DHA not only alleviated intrathecal LPS-evoked mechanical allodynia, but also reduced TRAF6 upregulation and the activation of microglia in the spinal cord. These data suggest that TRAF6 plays a vital role in CFA-induced pain. DHA manifests its effects on reducing chronic pain partially through suppression of TRAF6 upregulation and microglial activation.

TRAF6, an important adaptin in TRAFs family, can be activated rapidly and gather together to intracellular areas, and then carry out its physiological function primarily (Dou et al. 2018). Recent studies showed that TRAF6 protein levels were significantly increased in the DRG and spinal dorsal horn in rat models of CCI (chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve) (Wang et al. 2018b). In addition, TRAF6 expression was negatively regulated by miR-146a-5p (Lu et al. 2015), and miR-146a-5p antagomir increased TRAF6 expression and exacerbated the pain-related behavior of CCI rats (Wang et al. 2018b). Our previous data showed that spinal TRAF6 contributed to SNL-induced neuropathic pain (Lu et al. 2014). Weng et al. reported that targeting spinal TRAF6 expression relieved neonatal colonic inflammation-induced chronic visceral pain in adult rats (Weng et al. 2020). In this study, we revealed an increase of TRAF6 in the spinal cord after intraplantar injection of CFA or intrathecal injection of LPS, suggesting a possible role of TRAF6 in inflammatory pain.

Our previous data showed that TRAF6 was mainly co-localized with the astrocytic marker GFAP on SNL day 10 and partially expressed in microglia on SNL Day 3 (Lu et al. 2014). Wang et al. also reported that TRAF6 was primarily co-localized with astrocytes 10 days after SNL (Wang et al. 2017). In vitro experiments indicated that LPS, via acting on TLR4, resulted in increased TRAF6 in different cell types, including BV2 microglia (Li et al. 2019), RAW 264.7 macrophages (Jakus et al. 2013), and U87 glioblastoma cells (Bedini et al. 2017). Intrathecal injection of LPS induced spinal microglial activation and the upregulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Zhu et al. 2014). CFA increased microglial activation and TLR4 mRNA and protein expression in the spinal cord (Zhao et al. 2015; Qian et al. 2016). Consistently, the present study showed that CFA induced microglial activation and TRAF6 expression in spinal microglia 3 days after CFA. Moreover, LPS elicited TRAF6 upregulation in both BV2 and primary cultured microglial cells. These results indicate the involvement of TRAF6 in inflammatory pain via spinal microglia.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are one of the valuable tools to investigate the functions of genes, and are also used for gene silencing (Selvam et al. 2017). Appropriate chemical modifications can improve the stability, specificity, and potency of siRNA. In this study, a single intrathecal injection of 5′-cholesteryl and 2′-O-methylribonucleotide-modified TRAF6 siRNA significantly enhanced the pain thresholds of CFA mice from 6 to 48 h. Given the high expression of TRAF6 in the spinal microglia and the reversal effect of the behavioral phenotypes by knocking down spinal TRAF6 after CFA, it is therefore suggested that TRAF6 possibly represents a potential strategy for the therapy of chronic inflammatory pain. It has been indicated that TRAF6 promotes microglial inflammatory activation. For example, knocking down TRAF6 suppressed the LPS-induced p38/JNK phosphorylation in microglia (Li et al. 2019). TRAF6 siRNA intravitreal injection inhibited activation of microglia (Ding et al. 2018). In this study, transfection of TRAF6 siRNA in BV2 not only prevented LPS-induced TRAF6 regulation but also decreased IBA-1 expression. Therefore, we hypothesized that LPS-evoked activation of microglia might be associated with the upregulation of TRAF6. Indeed, our in vivo data showed that knocking down TRAF6 by siRNA was sufficient to reverse the changes of the behavioral phenotypes and inhibit the increase of spinal IBA-1 in CFA mice, supporting that TRAF6 exerts nociceptive effects via activating microglia under inflammatory pain condition.

Accumulating evidence has shown that oral administration of DHA significantly reduced formalin-induced inflammatory pain, post-operative pain, and neuropathic pain (Nakamoto et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2018; Landa-Juarez et al. 2019; Manzhulo et al. 2015). Consistent with these results, we showed that DHA reduced inflammatory pain induced by intrathecal injection of LPS or intraplantar injection of CFA, indicating that DHA has extensive analgesic effects. Our results also showed that DHA prevented the upregulation of TRAF6 and microglial activation induced by LPS or CFA. It has been suggested that dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty supplements inhibited high-fat diet-induced hypothalamic protein upregulation of TRAF6 and TLR4 in rats (Pimentel et al. 2013). In LPS-activated human aortic endothelial cells, DHA suppresses the translocation of TLR4 into lipid rafts and inhibited the ubiquitination and translocation of TRAF6 as well as the phosphorylation of transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), p38, and IκBα (Huang et al. 2015). Meanwhile, DHA inactivates TAK1 and inhibits inflammatory responses via a GPR120/β-arrestin2 interaction in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Oh et al. 2010). Thus, DHA may inhibit microglial activation via both TRAF6-dependent and TRAF6-independent way.

Numerous studies have confirmed a vital role of astrocytes in the development of chronic pain (Ji et al. 2019). Manzhulo et al. reported that DHA treatment reduced the number of reactive astrocytes in the spinal cord dorsal horn in CCI-induced neuropathic pain model (Manzhulo et al. 2016). Although the current study characterized that DHA inhibited microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in the spinal cord, DHA may also have a similar effect on astrocytes. Additionally, it was noteworthy that intrathecal delivery of drugs can affect both the spinal cord and DRG (Kawasaki et al. 2008; Lu et al. 2015). Thus, the intrathecal DHA or TRAF6 siRNA may also produce anti-hyperalgesic effects via peripheral mechanisms.

In summary, the current findings support the idea that TRAF6 in the spinal cord takes part in CFA-induced hypersensitivity of mice through activating microglia. TRAF6 expression and microglial activation can also be regulated by DHA. These results might provide valuable information regarding a novel therapeutic approach for chronic inflammatory pain control in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31871064, 32030048, and 31700899) and Nantong Science and Technology Planning Project (Nos. JC2020073 and JC2020038).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajith TA (2018) A recent update on the effects of omega-3 fatty acids in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Clin Pharmacol 13(4):252–260. 10.2174/1574884713666180807145648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch RH, Gedrich RW, Thompson CB (1998) Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs): a family of adapter proteins that regulates life and death. Genes Dev 12(18):2821–2830. 10.1101/gad.12.18.2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet RP, Laye S (2014) Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 15(12):771–785. 10.1038/nrn3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedini A, Baiula M, Vincelli G, Formaggio F, Lombardi S, Caprini M, Spampinato S (2017) Nociceptin/orphanin FQ antagonizes lipopolysaccharide-stimulated proliferation, migration and inflammatory signaling in human glioblastoma U87 cells. Biochem Pharmacol 140:89–104. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley JR, Pober JS (2001) Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs). Oncogene 20(44):6482–6491. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Zhang YQ (2008) Spinal glial activation contributes to pathological pain states. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 32(5):972–983. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wu X, Shao B, Zhao W, Shi W, Zhang S, Ni L, Shen A (2011) Increased expression of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 after rat traumatic brain injury. Cell Mol Neurobiol 31(2):269–275. 10.1007/s10571-010-9617-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt-Peyrusse V, Sargueil F, Moranis A, Harizi H, Mongrand S, Laye S (2008) Docosahexaenoic acid prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in microglial cells by inhibiting lipopolysaccharide receptor presentation but not its membrane subdomain localization. J Neurochem 105(2):296–307. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Zhu M, Liu X, Jiang L, Xu J, Chen L, Liang J, Li L, Zhou T, Wang Y, Shi H, Yuan Y, Song E (2018) Inhibition of TRAF6 alleviates choroidal neovascularization in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 503(4):2742–2748. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ (1980) Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 20:441–462. 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Tian X, Zhang J, Wang Z, Chen G (2018) Roles of TRAF6 in central nervous system. Curr Neuropharmacol 16(9):1306–1313. 10.2174/1570159X16666180412094655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Arjona MDM, Grondona JM, Granados-Duran P, Fernandez-Llebrez P, Lopez-Avalos MD (2017) Microglia morphological categorization in a rat model of neuroinflammation by hierarchical cluster and principal components analysis. Front Cell Neurosci 11:235. 10.3389/fncel.2017.00235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YJ, Ji RR (2010) Targeting astrocyte signaling for chronic pain. Neurotherapeutics 7(4):482–493. 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YJ, Xu ZZ, Liu YC, Wen YR, Decosterd I, Ji RR (2010) The c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) in spinal astrocytes is required for the maintenance of bilateral mechanical allodynia under a persistent inflammatory pain condition. Pain 148(2):309–319. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RD, Suter MR, Ji RR, Decosterd I (2010) Glial cells and chronic pain. Neuroscientist 16(5):519–531. 10.1177/1073858409360822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi-Monfared A, Firouzi M, Bahrami Z, Zahednasab H, Harirchian MH (2018) Minocycline decreases CD36 and increases CD44 in LPS-induced microglia. J Neuroimmunol 317:95–99. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath RJ, Nutile-McMenemy N, Alkaitis MS, Deleo JA (2008) Differential migration, LPS-induced cytokine, chemokine, and NO expression in immortalized BV-2 and HAPI cell lines and primary microglial cultures. J Neurochem 107(2):557–569. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CT, Lee YJ, Dai X, Ojeda NB, Lee HJ, Tien LT, Fan LW (2018) Systemic lipopolysaccharide-induced pain sensitivity and spinal inflammation were reduced by minocycline in neonatal rats. Int J Mol Sci 19(10):2947. 10.3390/ijms19102947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Sheu WH, Chiang AN (2015) Docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid suppress adhesion molecule expression in human aortic endothelial cells via differential mechanisms. Mol Nutr Food Res 59(4):751–762. 10.1002/mnfr.201400687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylden JL, Wilcox GL (1980) Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol 67(2–3):313–316. 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakus PB, Kalman N, Antus C, Radnai B, Tucsek Z, Gallyas F Jr, Sumegi B, Veres B (2013) TRAF6 is functional in inhibition of TLR4-mediated NF-kappaB activation by resveratrol. J Nutr Biochem 24(5):819–823. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Berta T, Nedergaard M (2013) Glia and pain: is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain 154(Suppl 1):S10-28. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Xu ZZ, Gao YJ (2014) Emerging targets in neuroinflammation-driven chronic pain. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13(7):533–548. 10.1038/nrd4334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Donnelly CR, Nedergaard M (2019) Astrocytes in chronic pain and itch. Nat Rev Neurosci 20(11):667–685. 10.1038/s41583-019-0218-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR (2008) Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci 28(20):5189–5194. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konigs A, Kiliaan AJ (2016) Critical appraisal of omega-3 fatty acids in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 12:1869–1882. 10.2147/NDT.S68652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa-Juarez AY, Perez-Severiano F, Castaneda-Hernandez G, Ortiz MI, Chavez-Pina AE (2019) The antihyperalgesic effect of docosahexaenoic acid in streptozotocin-induced neuropathic pain in the rat involves the opioidergic system. Eur J Pharmacol 845:32–39. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wei H, Piirainen S, Chen Z, Kalso E, Pertovaara A, Tian L (2016) Spinal versus brain microglial and macrophage activation traits determine the differential neuroinflammatory responses and analgesic effect of minocycline in chronic neuropathic pain. Brain Behav Immun 58:107–117. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Zhang D, Ge X, Zhu X, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Peng X, Shen A (2019) TRAF6-p38/JNK-ATF2 axis promotes microglial inflammatory activation. Exp Cell Res 376(2):133–148. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Zhao LX, Cao DL, Gao YJ (2013) Spinal injection of docosahexaenoic acid attenuates carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain through inhibition of microglia-mediated neuroinflammation in the spinal cord. Neuroscience 241:22–31. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Jiang BC, Cao DL, Zhang ZJ, Zhang X, Ji RR, Gao YJ (2014) TRAF6 upregulation in spinal astrocytes maintains neuropathic pain by integrating TNF-alpha and IL-1beta signaling. Pain 155(12):2618–2629. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Cao DL, Jiang BC, Yang T, Gao YJ (2015) MicroRNA-146a-5p attenuates neuropathic pain via suppressing TRAF6 signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav Immun 49:119–129. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzhulo IV, Ogurtsova OS, Lamash NE, Latyshev NA, Kasyanov SP, Dyuizen IV (2015) Analgetic effect of docosahexaenoic acid is mediated by modulating the microglia activity in the dorsal root ganglia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Acta Histochem 117(7):659–666. 10.1016/j.acthis.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzhulo IV, Ogurtsova OS, Kipryushina YO, Latyshev NA, Kasyanov SP, Dyuizen IV, Tyrtyshnaia AA (2016) Neuron-astrocyte interactions in spinal cord dorsal horn in neuropathic pain development and docosahexaenoic acid therapy. J Neuroimmunol 298:90–97. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marret E, Kurdi O, Zufferey P, Bonnet F (2005) Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on patient-controlled analgesia morphine side effects: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 102(6):1249–1260. 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M, Manaheji H, Maghsoudi N, Danyali S, Baniasadi M, Zaringhalam J (2020) Microglia dependent BDNF and proBDNF can impair spatial memory performance during persistent inflammatory pain. Behav Brain Res 390:112683. 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto K, Nishinaka T, Mankura M, Fujita-Hamabe W, Tokuyama S (2010) Antinociceptive effects of docosahexaenoic acid against various pain stimuli in mice. Biol Pharm Bull 33(6):1070–1072. 10.1248/bpb.33.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto K, Nishinaka T, Sato N, Mankura M, Koyama Y, Kasuya F, Tokuyama S (2013) Hypothalamic GPR40 signaling activated by free long chain fatty acids suppresses CFA-induced inflammatory chronic pain. PLoS ONE 8(12):e81563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natacci L, D MM, A CG, Nunes MA, A BM, L OC, Giatti L, MDC BM, I SS, Brunoni AR, P AL, I MB (2018) Omega 3 Consumption and anxiety disorders: a cross-sectional analysis of the Brazilian longitudinal study of adult health (ELSA-Brasil). Nutrients 10 (6). 10.3390/nu10060663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oh DY, Talukdar S, Bae EJ, Imamura T, Morinaga H, Fan W, Li P, Lu WJ, Watkins SM, Olefsky JM (2010) GPR120 is an omega-3 fatty acid receptor mediating potent anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects. Cell 142(5):687–698. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr SK, Palumbo S, Bosetti F, Mount HT, Kang JX, Greenwood CE, Ma DW, Serhan CN, Bazinet RP (2013) Unesterified docosahexaenoic acid is protective in neuroinflammation. J Neurochem 127(3):378–393. 10.1111/jnc.12392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel GD, Lira FS, Rosa JC, Oller do Nascimento CM, Oyama LM, Harumi Watanabe RL, Ribeiro EB, (2013) High-fat fish oil diet prevents hypothalamic inflammatory profile in rats. ISRN Inflam 2013:419823. 10.1155/2013/419823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian B, Li F, Zhao LX, Dong YL, Gao YJ, Zhang ZJ (2016) Ligustilide ameliorates inflammatory pain and inhibits TLR4 upregulation in spinal astrocytes following complete Freund’s adjuvant peripheral injection. Cell Mol Neurobiol 36(1):143–149. 10.1007/s10571-015-0228-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders EF, Ramsden CE, Sherazy MS, Gelenberg AJ, Davis JM, Rapoport SI (2016) Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in bipolar disorder: a review of biomarker and treatment studies. J Clin Psychiatry 77(10):e1301–e1308. 10.4088/JCP.15r09925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvam C, Mutisya D, Prakash S, Ranganna K, Thilagavathi R (2017) Therapeutic potential of chemically modified siRNA: recent trends. Chem Biol Drug Des 90(5):665–678. 10.1111/cbdd.12993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song ZP, Xiong BR, Guan XH, Cao F, Manyande A, Zhou YQ, Zheng H, Tian YK (2016) Minocycline attenuates bone cancer pain in rats by inhibiting NF-kappaB in spinal astrocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin 37(6):753–762. 10.1038/aps.2016.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starobova H, Mueller A, Allavena R, Lohman RJ, Sweet MJ, Vetter I (2019) Minocycline prevents the development of mechanical allodynia in mouse models of vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy. Front Neurosci 13:653. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhotnik I, Haj B, Pollak Y, Dorfman T, Bejar J, Matter I (2016) Effect of bowel resection on TLR signaling during intestinal adaptation in a rat model. Surg Endosc 30(10):4416–4424. 10.1007/s00464-016-4760-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun GY, Simonyi A, Fritsche KL, Chuang DY, Hannink M, Gu Z, Greenlief CM, Yao JK, Lee JC, Beversdorf DQ (2018) Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): an essential nutrient and a nutraceutical for brain health and diseases. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 136:3–13. 10.1016/j.plefa.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson CI, Zattoni M, Serhan CN (2007) Lipoxins and aspirin-triggered lipoxin inhibit inflammatory pain processing. J Exp Med 204(2):245–252. 10.1084/jem.20061826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh MC, Lee J, Choi Y (2015) Tumor necrosis factor receptor- associated factor 6 (TRAF6) regulation of development, function, and homeostasis of the immune system. Immunol Rev 266(1):72–92. 10.1111/imr.12302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Kong X, Zhu C, Liu C, Sun D, Xu Q, Mao Z, Qin Q, Su H, Wang D, Zhao X, Lin N (2017) Wu-tou decoction attenuates neuropathic pain via suppressing spinal astrocytic IL-1R1/TRAF6/JNK signaling. Oncotarget 8(54):92864–92879. 10.18632/oncotarget.21638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen H, Chen Q, Jiao FZ, Zhang WB, Gong ZJ (2018a) The protective mechanism of CAY10683 on intestinal mucosal barrier in acute liver failure through LPS/TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Mediators Inflamm 2018:7859601. 10.1155/2018/7859601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Liu F, Wei M, Qiu Y, Ma C, Shen L, Huang Y (2018b) Chronic constriction injury-induced microRNA-146a-5p alleviates neuropathic pain through suppression of IRAK1/TRAF6 signaling pathway. J Neuroinflamm 15(1):179. 10.1186/s12974-018-1215-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Milligan ED, Maier SF (2007) “Listening” and “talking” to neurons: implications of immune activation for pain control and increasing the efficacy of opioids. Brain Res Rev 56(1):148–169. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng RX, Chen W, Tang JN, Sun Q, Li M, Xu X, Zhang PA, Zhang Y, Hu CY, Xu GY (2020) Targeting spinal TRAF6 expression attenuates chronic visceral pain in adult rats with neonatal colonic inflammation. Mol Pain 16:1744806920918059. 10.1177/1744806920918059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X, Wang S, Shao F, Fang J, Xu Y, Wang W, Sun H, Liu X, Du J (2019) Electroacupuncture stimulation alleviates CFA-induced inflammatory pain via suppressing P2X3 expression. Int J Mol Sci 20(13):3248. 10.3390/ijms20133248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Yao X, Li H, Xue G, Guo Q, Yang G, An L, Zhang Y, Meng G (2017) Cutting edge: TRAF6 mediates TLR/IL-1R signaling-induced nontranscriptional priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Immunol 199(5):1561–1566. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Sun W, Fan J, Wang H, Han S, Li J, Yin Y (2020) Sirt1-ROS-TRAF6 signaling-induced pyroptosis contributes to early injury in ischemic mice. Neurosci Bull 36(8):845–859. 10.1007/s12264-020-00489-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Gao J, Wu B, Yan N, Li H, Ren Y, Kan Y, Liang J, Jiao Y, Yu Y (2017) Minocycline attenuates the development of diabetic neuropathy by inhibiting spinal cord Notch signaling in rat. Biomed Pharm 94:380–385. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K, Morrison H (2018) Quantifying microglia morphology from photomicrographs of immunohistochemistry prepared tissue using ImageJ. JoVE. 10.3791/57648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Terrando N, Xu ZZ, Bang S, Jordt SE, Maixner W, Serhan CN, Ji RR (2018) Distinct analgesic actions of DHA and DHA-derived specialized pro-resolving mediators on post-operative pain after bone fracture in mice. Front Pharmacol 9:412. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XH, Zhang T, Li YQ (2015) The up-regulation of spinal Toll-like receptor 4 in rats with inflammatory pain induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant. Brain Res Bull 111:97–103. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2015.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Deng Y, Li F, Yin C, Shi J, Gong Q (2019) Icariside II attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation through inhibiting TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB pathway in rats. Biomed Pharm 111:315–324. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MD, Zhao LX, Wang XT, Gao YJ, Zhang ZJ (2014) Ligustilide inhibits microglia-mediated proinflammatory cytokines production and inflammatory pain. Brain Res Bull 109:54–60. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.