Abstract

Traditional substrate cultivation is now a routine practice in vegetable facility breeding. However, finding renewable substrates that can replace traditional substrates is urgent in today’s production. In this study, we used the ‘Pindstrup’ substrate as control and two types of composite substrates made from fermented corn straw (i.e. 0–3 and 3–5 mm) to identify appropriate substrate conditions for tomato seedling growth under winter greenhouse conditions. Seedling growth potential related data and substrate water content related data were tested to carry out data-oriented support. Since the single physiological data cannot well explain the mechanism of tomato seedlings under winter greenhouse condition, transcriptomic analysis of tomato root and leaf tissues were conducted to provide theoretical basis. The physiological data of tomato seedlings and substrate showed that compared with 0–3 mm and Pindstrup substrate, tomato seedlings planted in 3–5 mm had stronger growth potential and stronger water retention, and were more suitable for planting tomato seedlings. Transcriptome analysis revealed a greater number of DEGs between the Pindstrup and the 3–5 mm. The genes in this group contribute to tomato growth as well as tomato stress response mechanisms, such as ABA-related genes, hormone-related genes and some TFs. The simulation network mechanism diagram adds evidence to the above conclusions. Overall, these results demonstrate the potential benefits of using the fermented corn straw of 3–5 mm for growing tomato seedlings and present a novel method of utilizing corn straw.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-73135-y.

Keywords: Fermented cron straw substrate, Tomato seedlings, Transcriptome analysis, Optimum ratio

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Biotechnology, Physiology

Introduction

The development of soil for vegetable cultivation has undergone a lengthy process, signifying the progression of the vegetable industry and modern biological techniques1. Initially, farmers utilized soil and organic fertilizers primarily composed of farmyard manure mixed with soil to supply nutrients for vegetable roots9. As we entered the 21st century, sphagnum moss combined with biochar has emerged as a popular growth medium due to its exceptional moisture retention and pH balancing properties. These characteristics collectively create an optimal environment for root development39. While for now, it is common practice to use substrate for planting in lieu of conventional soil, and its widespread use has become a standard practice14. Compared with traditional soil, substrate can increase water retention, which is significant for crops requiring large amounts of water during seedling stage28. But it could also increase challenge of tomato growth in winter greenhouse condition. In addition, the component of substrate is more controllable and safer than soil34, which could contain unknown pathogens. Substrates are primarily divided into inorganic, organic, and mixed substrate categories29. However, many traditional inorganic substrates composed of turf, perlite, vermiculite, and a few other substrates are used in production, cultivation, and seedling cultivation17. Compared with other substrates, inorganic substrates may cause adverse effects on the ecological environment and incur higher costs27. Straw cultivation substrate has been widely used in Europe and North America10. But in China, researches on seedling substrate only began to develop since 1970s16. It is crucial to identify alternative substrates that are recyclable and sustainably developed, in order to improve the seedling quality of maize while replacing traditional inorganic substrates.

As a non-recyclable material, the burning of corn straw after harvest has posed a significant environmental burden15. However, in recent years, there has been a new agricultural trend towards using vermiculite and perlite as substitutes for traditional substrates after fermentation, in order to promote environmental protection and sustainable development. Nevertheless, there is currently limited discussion on the pre-fermentation use of corn straw and the size of sieve pores.

As one of the most crucial vegetable crops, it is imperative to enhance tomato yield and growth characteristics2,35. A previous study has indicated that a temperature of 10℃ is critical for tomato growth; below this threshold, tomato plants become stunted or die4,40. Therefore, cultivating tomatoes in greenhouses during winter presents a challenge due to the nighttime temperature and soil moisture requirements for optimal tomato growth.

Studies on the known molecular mechanism of plant growth under winter greenhouse conditions indicated that DEGs were correlated to cold and light adaptability of plants19. As far as we known, hormone-related genes (phenylpropionic acid, abscisic acid, jasmonic acid and salicylic acid, etc.) played a regulatory role in temperature and light stresses8,50. Abscisic acid (ABA) is a plant endogenous hormone which is micro but essential for plant growth. It was important in signal integration and regulation, which was effective in low temperature and light conditions41. After binding with ABA receptors, water was lost in cells to maintain cell membrane stability. ABA continued to reduce the damage synthesis of light, ensured the synthesis of carbohydrate and energy metabolism of plants, enhanced the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes and the activity of antioxidant enzyme to reduce cell damage, and accumulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the membrane system, so as to maintain the normal growth of plants33. Jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) are regarded as participants in plant-defensive signal transduction6. SA mediated low-temperature induction of grape bud dormancy release, alleviating plant growth under low-temperature and light stress45. Zhu47 proved that methyl jasmonate could increase cold stress tolerance by regulating plant hormone content and the expression of temperature tolerance genes in rice.

Besides, transcription factors (TFs) are regulatory proteins with DNA domains, which could control the expression of target genes by directly binding to target genes. From the perspective of combinatorial gene regulation, TFs were able to control varieties of cellular process40. As the second largest family of TFs in plants, bHLH played a significant role in plant growth, development and abiotic stress response18. The domain was composed of two parts, one in the N-terminal basic region and the other in the C-terminal HLH region. The function of the C-terminal HLH region was to enable protein-to-protein interactions to form homologous dimers or heteropolymers. The bHLH family can combine with itself to form homologous dimers, and also combine with other TFs to form heterodimers and trimers to play roles, which was considered to be the role of bHLH in plants under abiotic stress12. In recent studies, the bHLH protein has been found to play a role in plant resistance to low temperature stress through the CBF pathway by enhancing active oxygen scavenging ability and promoting proline accumulation43,44,48.

In order to solve the damage to the ecological environment caused by traditional corn straw burning and to provide more effective means of heat preservation and water retention for the winter cultivation of vegetable seedlings in facilities, this study was carried out using the composite substrate of corn straw, vermiculite, and perlite instead of the traditional inorganic substrate. Tomato seedlings were cultured in the greenhouse during winter season. The seedling growth characteristics and substrate conditions were determined to visualize the growth of tomato seedlings. In order to more systematically reveal which genes and pathways are changed during the growth of tomato seedlings in winter greenhouse conditions, and more intuitively show the most suitable substrate condition, transcriptome analysis was carried out to, providing a new solution for winter tomato planting. Also opened up a new way for the resource utilization of corn straw.

Materials & methods

Plant materials

In this study, experimental substrate groups included crushed and degreased corn straw mixed with vermiculite and perlite. The control group ‘Pindstrup’ substrate was also mixed with vermiculite and perlite21. The corn straw was fermented after the decomposition of the composite substrate and then screened by 3 and 5 mm, the disposal method of corn straw was base on the method of He20. This study used two types of composite substrates with different particle sizes (represented by treatments 1 for 0–3 mm and 2 for 3–5 mm). ‘Pindstrup’ substrate (0–6 mm) was used as a control. In the present study, the tomato variety ‘Fentailang’ was obtained from the Institute of Vegetable Research of the Liaoning Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shenyang, China. Fentailang is a large, juicy, pink tomato variety with flat or round fruit and a thin skin. It has medium sweet and sour taste, juicy flesh and general quality. It is widely cultivated in Liaoning Province, China. The tomato seeds were heated with 55℃ water for 15 min, disinfected and soaked for 6 h, and incubated in a 20℃ incubator for 24 h25. Following treatment, the seeds were transferred to seedling trays (51 × 32 × 5.5 cm) made of polyethylene foam with 72 mesh. The composite substrates, varying in particle sizes, were distributed among three seedling containers, with each hole in the seedling trays containing a single seed. The seedlings underwent greenhouse cultivation starting from December, with daytime temperatures ranging approximately from 25 to 28℃ and nighttime temperatures ranging from 8 to 10℃, which was low temperature treatment for tomato seedlings. The tomato seedlings were collected in January, approximately 40 days after sowing, for the following experiment.

Measurement of growth parameters of tomato seedlings

The seedling length was calculated from the tip of the adventitious roots to the plant’s apex. The stem diameter was measured using vernier calipers. The number of leaves and their emergence rate were also calculated by counting. Chlorophyll content was measured using a hand-held chlorophyll meter (Digital Hand-held ‘Pocket’ Refractometer, PAL-ɑ, Japan). The above-ground and below-ground parts of 20 seedlings were collected separately, weighed, and dried at 80℃ in an oven for approximately 48 h until the seedlings became brittle. The dry above-ground and below-ground samples were used to calculate the seedlings’ total fresh and dry weights, respectively30.

Changes in the substrate physical properties

Correlation data were collected to identify the relative changes in the substrate properties before and after planting. The correlation values of the substrates before and after cultivation were measured based on the Plug Seedling Substrate of Vegetable (Agricultural industry standard of the People’s Republic of China, NY/T 2018 − 2012).

Total RNA extraction and library construction

Three replicates were used to each group of leaf and root tissues from ‘Pindstrup’, treatments 1 and 2 substrates. Those tissues were collected and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80℃ until the RNA extraction. RNA was extracted according to Zhang46 methods. Following extraction, in order to better understand the changes between those experiment and control groups, a transcriptome library was constructed by the Biomarker Technology Company (Beijing, China).

Functional annotation analysis of candidate genes

The sequencing results were screened and analyzed to filter out low-quality genes. The raw data format for the offline data of Nanopore sequencing was a second-generation fast5 format included all raw sequencing signals6. After those processing, the ReadNum and BaseNum results were obtained. The principal component analysis (PCA) diagram was plotted based on the amount of gene expression (CPM) of each sample. Gene function was annotated based on the KEGG pathway analysis (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/)24, which was used to test the statistical enrichment of DEGs in the KEGG pathways. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DEGs was implemented using the GOseq R packages34, consisting of three parts and aimed to classify and annotate DEG functions.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) validation of DEGs

qRT-PCR was used to verify the accuracy of the DEGs from the transcriptome data, three replicates were used. The reverse transcription RNA samples were obtained using the UltraSYBR Mixture (Low ROX, TIANGEN). The primer sequences used in this study are listed in the Supplementary Table S1.

TF prediction

Related transcription factors were found to support the protective effects of different substrates under low-temperature stress and other stress responses.

Data processing

Origin was used to process the data obtained from the transcriptome and qRT-PCR analyses. All data presented were repeated with three biological replicates (p < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference standard).

Plant material statement

We recommend that authors comply with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Results

Seedling growth characteristics under different substrate treatments

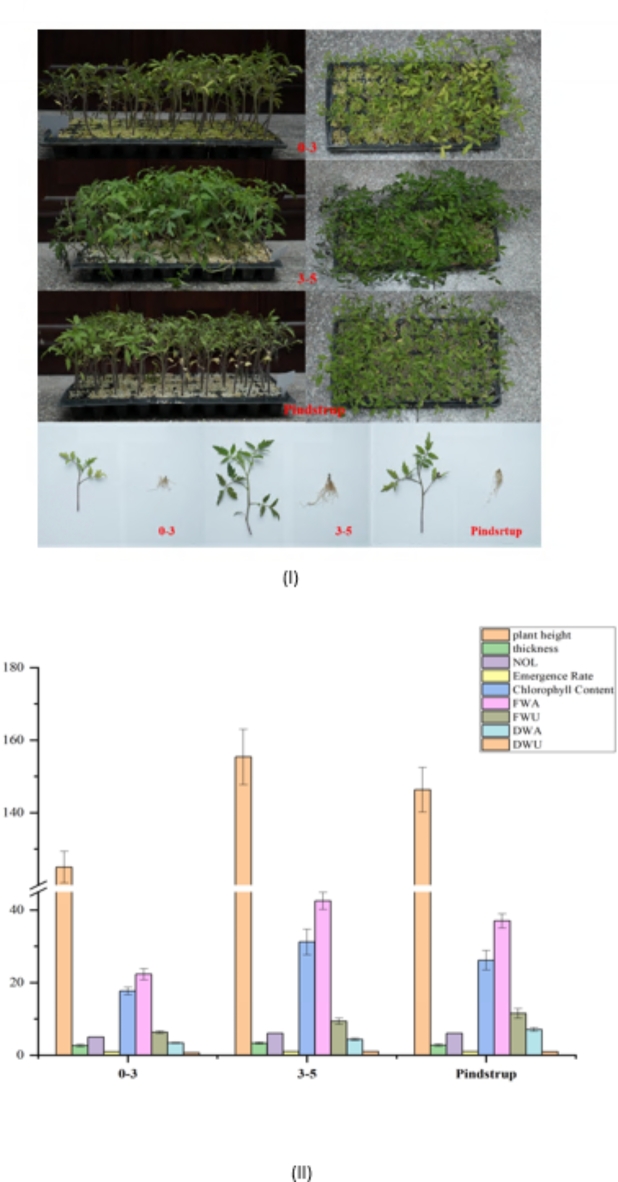

To obtain the differences in the growth characteristics under different substrate treatments, variation tendency of seedlings growth characteristics were examined (Fig. 1II). Seedlings grown with treatment 2 (3–5 mm) substrate had the optimal growth potential among all experimental groups and control group. Photographs of tomato seedlings grown with different substrates were presented in Fig. 1I. In summary, tomato seedlings cultivated under treatment 2 were 24% higher than treatment 1, 6% higher than control group. And treatment 2 was 25% and 19% thicker than treatment 1 and control group, respectively (Supplementary table-S2). By counting the emergence rate, treatment 2 express the same tendency with control group, which was 8% higher than treatment 1. Chlorophyll content showed that treatment 2 was 76% and 19% higher than treatment 1 and control group, respectively. The results of dry and fresh weight above and below ground also explain the advantage of treatment 2 contrast of treatment 1 and control group.

Fig. 1.

(I) Tomato seedlings with different substrates. (II) Analysis of growth parameters of tomato seedlings under different substrate treatments.

Physical properties of substrates changes

In order to get further characterize the changes of different substrates before and after implantation, the physical properties of substrates were measured (Fig. 2). Mean bulk density (%), relative water content of substrate (%), total porosity (%), ventilation porosity (%), and water holding porosity (%) were measured (Supplementary table-S3).Tomato seedlings cultivated with treatment 1 showed the poorest result, the relative water content and ventilation porosity changed double before and after implantation, total porosity after implantation was − 871% higher than before, water holding porosity after implantation was − 1832% higher than before, these indicate that the treatment 1 substrate was not suitable for long-term planting. In the control substrate group, the relative water content (1895%) and porosity of the substrate (540%) changed greatly before and after implantation, but the other indexes tendency were good. The results of the treatment of 2 substrates also verified the reasons for the strong growth of the planted tomatoes, especially the changes in the ventilation porosity of the substrate changed 75% before and after planting, which illustrated the advantage of treatment 2. Relative water content of substrate of treatment 2 changed 465% over the implantation, this experimental result was more ideal than treatment 1 (2056%) and control group (1895%). The soil in the winter greenhouse is moist, and the negative increase in aeration porosity is conducive to the growth of tomato roots and the transport of oxygen and other substances.

Fig. 2.

Substrates changes statistics over the implantation.

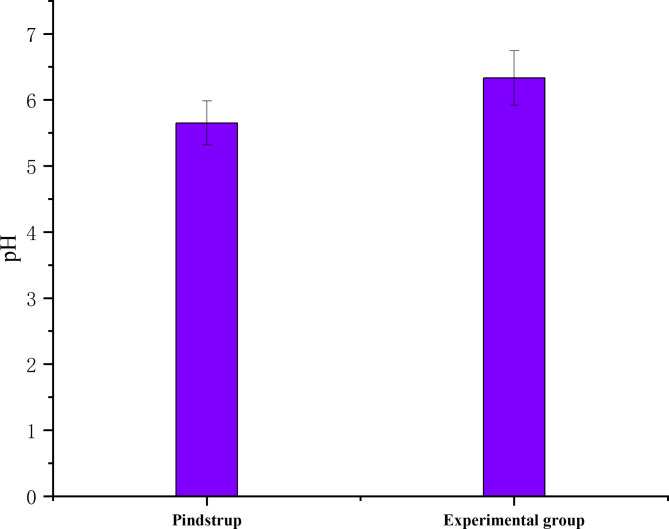

The substrate pH value was measured in triplicate and the mean value was calculated (Fig. 3, Supplementary table-S4). The pH of control group was 5.65 and the experimental group was 6.33. Both substrate pH of control and experimental group showed beneficial to the growth of tomato seedlings.

Fig. 3.

pH value of substrates over the implantation.

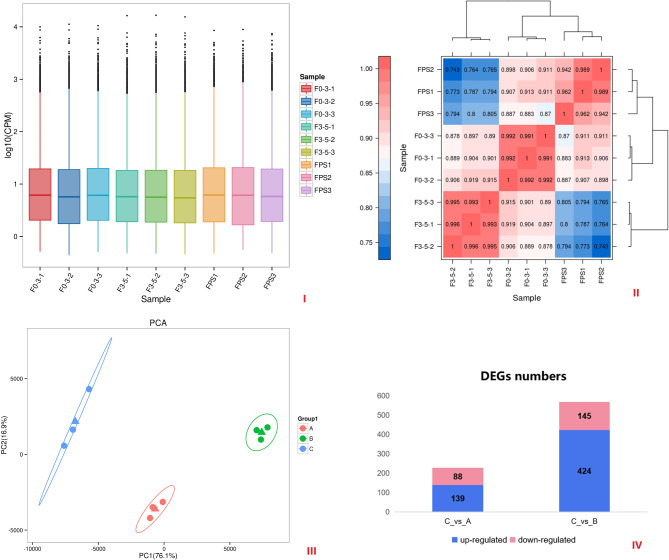

Data analysis and screening of transcriptome

The ReadNum and BaseNum results were presented in Table 1. N50 values of these samples varied from 1250 to 1400 bp and the mean Q score was Q14. The approximate mean lengths of the treatment 1 (0–3 mm), treatment 2 (3–5 mm), and control group (Pindstrup) generated libraries were 1350, 1260, and 1330, respectively. After removing rRNA sequences, the full-length percentage (FL%) was approximately 91% above all the results. The CPM indicated the reliability of the transcriptome results (Fig. 4I). Expression-dependent heatmap of pairwise samples was presented in Fig. 4II, demonstrating a negative correlation between treatment 2 and control group. PCA diagram was demonstrated at Fig. 4III, each dot represented a sample, each color represented a sample grouping, and the ovals represented the confidence intervals of the grouped samples.

Table 1.

Statistics of clean reads in the tomato transcriptomes.

| Sample | ReadNum | BaseNum | N50 | MeanLength | MaxLength | MeanQscore | cleanReadNumers (except rRNA) | flncReadNumbers | flncRatio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F0-3-1 | 5,192,865 | 6,896,513,254 | 1545 | 1328 | 32,336 | Q14 | 4,605,802 | 4,215,591 | 91.53% |

| F0-3-2 | 5,988,515 | 7,986,789,992 | 1541 | 1333 | 33,082 | Q14 | 5,368,842 | 4,925,527 | 91.74% |

| F0-3-3 | 5,052,831 | 6,986,488,653 | 1586 | 1382 | 235,064 | Q14 | 4,582,482 | 4,208,893 | 91.85% |

| F3-5-1 | 5,706,538 | 7,256,438,411 | 1453 | 1271 | 420,471 | Q14 | 5,130,760 | 4,690,040 | 91.41% |

| F3-5-2 | 5,911,237 | 7,399,358,575 | 1447 | 1251 | 104,080 | Q14 | 5,212,857 | 4,774,639 | 91.59% |

| F3-5-3 | 6,129,677 | 7,690,378,994 | 1468 | 1254 | 39,817 | Q14 | 5,345,151 | 4,867,362 | 91.06% |

| FPS1 | 5,763,472 | 7,868,074,800 | 1656 | 1365 | 77,995 | Q14 | 4,974,804 | 4,480,092 | 90.06% |

| FPS2 | 4,785,135 | 6,633,961,362 | 1608 | 1386 | 26,847 | Q14 | 4,255,540 | 3,863,431 | 90.79% |

| FPS3 | 5,582,649 | 7,012,567,561 | 1450 | 1256 | 20,073 | Q14 | 4,995,598 | 4,534,680 | 90.77% |

F0-3=’0–3’; F3-5=’3–5’;FPS=’Pindstrup’.

Fig. 4.

Result of transctriptome.

To identify the differences between all samples and the best ratio of substrates, ‘Pindstrup’ was used as a control to treatment 1 and treatment 2 (Fig. 4IV). A total of 139 and 424 up-regulated and 88 and 145 down-regulated DEGs were identified, respectively.

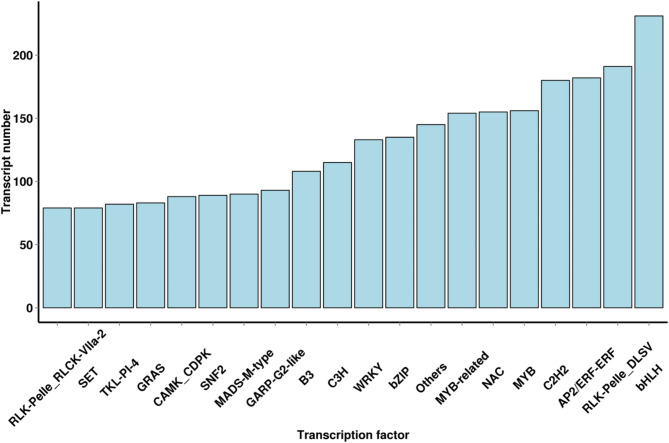

TF predictions

A total of 5,732 TFs were predicted for the new transcripts obtained in this study to identify the regulatory proteins involved in tomato growth in different substrates under winter greenhouse condition, twenty different TFs were identified in this study with the total numbers presented in Fig. 5. In total, 182 AP2/ERF-ERF (APETALA2/ethylene responsive factor) TFs were identified, which were closely related to plant growth and development and stress response. Furthermore, other TFs related to adversity stress were also identified, including MYB (310), NAC (155), WRKY (133), and B3 (108).

Fig. 5.

Prediction of transcription factors.

DEG GO functional enrichment analyses

GO analysis was performed on the filtered DEGs which were grouped into three categories: Cellular Components, Biological Process, and Molecular Function. The GO analysis results of control vs. treatment 1 and control vs. treatment 2 are presented in Fig. 6. In Cellular Components, membrane-related genes were most abundant, followed by genes involved in photosynthesis. In the Molecular Function category, catalytic activity and binding were most abundant, while the metabolic process was most abundant in the Biological Process category. The DEGs from response to stimulus and signaling, which were known to be related to adverse stress response, also were identified by the GO analysis.

Fig. 6.

GO analysis.

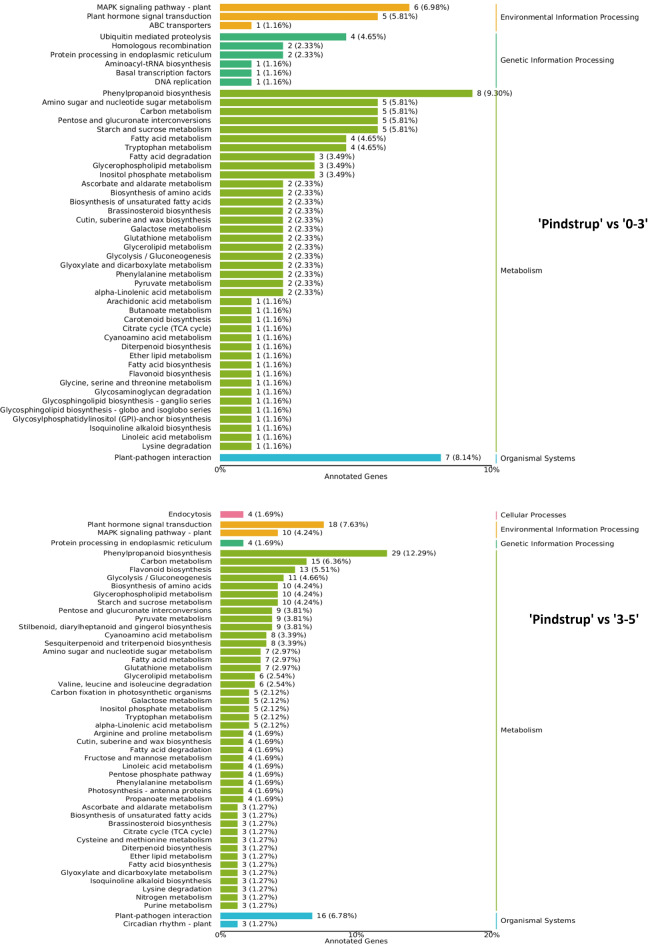

DEG KEGG analyses

KEGG analysis was performed on the filtered DEGs which were grouped into three categories: Metabolism, Organismal System, and Environmental Information Processing. Metabolic Pathway contained most DEGs representing the ‘metabolic pathway’ and ‘biosynthesis of secondary metabolites’, with the specific results presented in Fig. 7. MAPK signaling pathway-plant was most abundant in the Environmental Information Processing category. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis was the most abundant part of Metabolism and plant-pathogen interaction was most abundant in the Organismal System, all of which were known to be related to adverse stress response. Specific functions of these DEGs, however, require further investigation.

Fig. 7.

KEGG analysis.

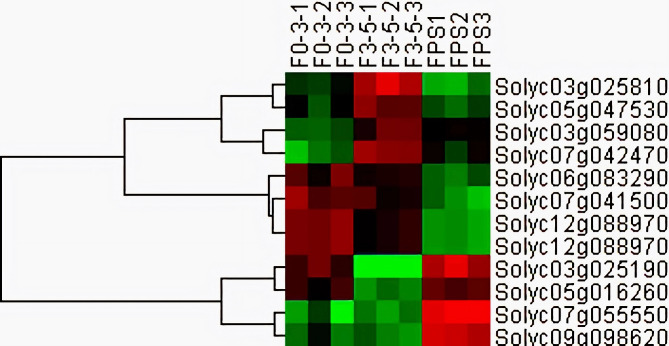

Identification of potential genes associated with low temperature and light

Changes in the tomato transcriptome at winter greenhouse condition were examined by gene expression pattern cluster analysis (Fig. 8). The genes identified in this analysis were related to defense mechanisms, response to abscisic acid, sensory perception of temperature stimulus, and response to light stimulus.

Fig. 8.

Heat-map analysis of potential genes.

Validation of DEGs with qRT-PCR

To validate the accuracy of the RNA-seq data, a total of 13 related DEGs expression levels were verified using qRT-PCR. The results were consistent with transcriptome data (Fig. 9). In total, four genes were down-regulated and nine were up-regulated in the control vs. treatment 2 group.

Fig. 9.

qRT-PCR analysis of DEGs.

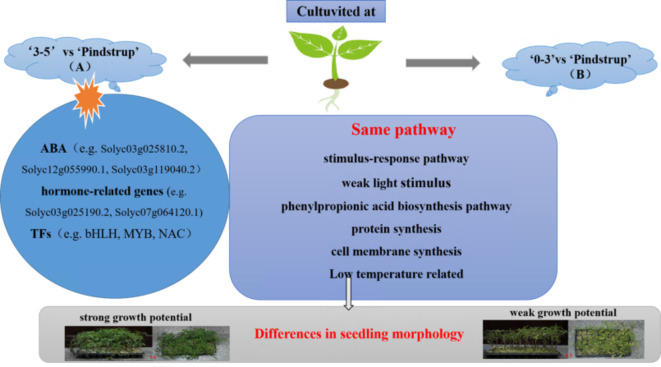

Speculation on the growth mechanism of tomato seedlings treated with different substrates

Network diagram (Fig. 10) was created to enhance the understanding of the growth and development of tomato seedlings under different substrates. The two treatments of tomato seedlings clearly demonstrated the same mechanism of action and specific mechanisms under winter greenhouse conditions, involving DEGs in pathways against low temperature and low light. Specifically, ‘3–5’ vs ‘Pindstrup’ exhibited more DEGs related to ABA and hormone-related genes as well as correlated TFs. These particular genes may be the key factors contributing to the suitability of tomato seedlings cultivated with ‘3–5’ substrate for winter greenhouse conditions.

Fig. 10.

Speculation on the growth mechanism of tomato seedlings treated with different substrates.

Discussion

This study utilized different substrate conditions to assess the growth characteristics of tomato seedlings and the potential use of corn straw as an alternative to traditional substrates. Transcriptome data analysis was conducted to identify optimal substrate conditions for tomato seedling growth. The traditional ‘Pindstrup’ substrate served as the control, while fermented corn stalks were used in a composite screening test with 3 mm (0–3) and 5 mm (3–5) contrasts. The aim was to identify the most suitable substrate conditions for winter greenhouse cultivation of tomatoes.

Among the three groups, tomato seedlings cultivated with treatment 2 was 20% higher than treatment 1 tomato, similar to the control group. The leaf chlorophyll content of treatment 2 tomato was 81% higher than treatment 1 and 18% higher than control group (Fig. 1). The relative water content of the substrate and the total porosity of the substrate, both before and after cultivation, further supported the validity of using the treatment 2 for tomato cultivation. The relative water content of the substrate over the implantation of treatment 2 changed with minimum amplitude (4.65%) and the least ventilation porosity changes of the treatment 2 substrate (0.75%). These suggest that the ‘3–5 mm’ substrate is more suitable for promoting tomato seedling growth under winter greenhouse conditions (Figs. 2 and 3). These results suggest that the ‘3–5’ substrate water content was optimal, especially under low temperatures, which could supply the plant with energy. Previous research on increasing greenhouse tomato yields was focused on the use of various composts11,13. The relative water content and total porosity of the substrate showed a downward trend before and after seeding, indicating that tomato seedlings could better absorb water in the substrate and could better assist the growth of tomato seedlings under low temperature and low light conditions7. The pH value of substrates showed that control group and the experimental groups were weakly acidic, and suitable for seedlings growth3. Winter greenhouse condition could cause low temperatures and light conditions, which were extremely unfavorable to the growth of tomato7. Transcriptome analysis was performed on the roots and leaves of tomato seedlings since single physiologic data could not accurately explain the growth difference of tomato seedlings under different substrate conditions. The result demonstrated that compared with control vs. treatment 1, control vs. treatment 2 had more DEGs. The GO analysis results showed that both groups had DEGs in the stimulus-response pathway, which are significantly influenced under low-temperature conditions36. Solyc07g042470.2 and Solyc05g041580.1 may be involved in the regulation of low-temperature stimulus and auxin response. Furthermore, 165 DEGs (e.g. Solyc06g083290.1 and Solyc05g016260.2) may be related to weak light stimulus. Previous research has demonstrated that ABA plays an essential role in the weak light condition response42. In the current study, 30 DEGs from control vs. treatment 2 were related to ABA (e.g. Solyc03g025810.2, Solyc12g055990.1, and Solyc03g119040.2) (Supplementary table-S5). These DEGs were all identified from control vs. treatment 2, which also shows that treatment 2 was more beneficial for tomato seedling growth. In the KEGG results, many DEGs were found in the phenylpropionic acid biosynthesis pathway (precursor of SA synthesis) (including Solyc05g047530.2, Solyc07g055550.1, Solyc12g088970.1, Solyc09g098620.2, and Solyc12g088970.1) (Supplementary table-S5) which is considered to be the mechanism of action under stimulus and stress22. Moreover, other plant growth hormone-related genes worked at the root37 such as SA (e.g. Solyc10g086380.1) and JA (e.g. Solyc05g053870.2, Solyc08g044340.1, and Solyc01g005440.2) (Supplementary table-S5) are involved in plant growth.

The KEGG results demonstrated that a greater number of genes related to phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and carbon metabolism were implicated in the growth of tomato seedlings in the ‘3–5’ group compared with the ‘0–3’ group. Phenylpropanoids serve as the precursors of numerous secondary metabolites in plants, such as flavonoids, isoflavones, anthocyanins, and lignin, among others52. Carbon metabolism constitutes an essential step in plant photosynthesis. It can be deduced that these key factors account for the more vigorous growth of tomato seedlings in the ‘3–5’ group. The above DEGs were predicted to take part in phenylpropionic acid, SA and JA metabolism and other metabolic processes, including cell growth. Numerous studies have demonstrated that these plant hormone-related metabolic pathways antagonize low-temperature conditions32,51. Some of these DEGs may be affected during photosynthesis, with 82 DEGs found to be involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Therefore, it is believed that these DEGs are implicated in photosynthesis and related processes, all of which are crucial for tomato seedling growth. These findings provide a basis for further research into the underlying molecular mechanisms of tomato seedling response to low temperature and light, with the potential to identify related genes.

In addition, some DEGs (e.g. Solyc05g014430.1 and Solyc05g014450.1) were part of the MAPK signaling pathway, thought to be related to plant growth under low temperatures23,38. In control vs. treatment 2, more genes related to protein synthesis (e.g. Solyc04g081910.2 and Solyc05g056050.2) (Supplementary table-S5) and cell membrane synthesis (e.g. Solyc01g048590.1 and Solyc09g064400.1) (Supplementary table-S5) were identified, suggesting that these DEGs played a positive role in regulating the growth of tomato seedlings. Furthermore, some DEGs that play a regulatory role under low-temperature stress and weak light conditions were identified including Solyc03g025190.2 (from control vs. treatment 2), which is a bHLH transcription factor that is regulated and induced by low temperature31. Many DEGs were specifically expressed in control vs. treatment 2, providing a theoretical basis for active growth under low temperature and light stimulus conditions. A molecular mechanism of the effect of different substrates on the growth of tomato seedlings under low temperature and low light conditions was predicted. It was suggested that the filtration pore size of ‘3–5’ mm would better induce the synthesis of ABA-related genes, hormone-related genes and some TFs during the growth of tomato seedlings. In the analysis of differential genes within the carbon metabolism pathway, 15 DEGs were identified, among which 13 were up-regulated genes, 2 of them were significantly up-regulated (Solyc07g044710.1, OnT-7038), and 2 were down-regulated genes. Nevertheless, no significant DEGs were discovered in the sugar accumulation pathway, as well as chlorophyll synthesis and degradation pathways. Hence, we hypothesized that the fermentation of corn stalk substrate could enhance the carbon metabolism process and boost the growth of tomato seedlings. In the transcriptome results, several specific transcription factors were found involved in the growth process of tomato seedlings planted in the ‘3–5’ mm substrate, such as bHLH, MYB and NAC, and these transcription factors were involved in the low temperature regulation and promoted the growth of tomato seedlings. MYB and bHLH transcription factor families play important roles in plant growth and development and abiotic stress conditions, and are key components in regulating many biological process signal networks in plants51. NAC transcription factor family plays an important role in plant growth and development, biological and abiotic stress response. It is speculated that these influencing factors lead to stronger growth of tomato seedlings. However, the specific underlying mechanisms require further study.

Conclusions

Physiological data indicated that the growth potential of tomato seedlings in treatment 2 was significantly higher than that in treatment 1 and control group. Specifically, the plant height in treatment 2 (155.37 mm) was 20% greater than in treatment 1 (125.01 mm), similar to the control group (146.31 mm). Furthermore, the leaf chlorophyll content of treatment 2 (31.22 mg/L) was 81% higher than treatment 1 (17.7 mg/L) and 18% higher than the control group (26.18 mg/L). The relative water content of the substrate for treatment 2 showed minimal changes during implantation with a minimum amplitude of only 4.65%, as well as exhibiting the least ventilation porosity changes at just 0.75%. It also provided a new idea for the resource utilization of corn straw. Transcriptome analysis was conducted on the roots and leaves of tomato seedlings in order to elucidate the growth disparity of tomato seedlings under different substrate in winter greenhouse conditions. A total of 227 DEGs were identified from the comparison between control and treatment 1, and 569 DEGs from the comparison between control and treatment 2. In addition, 13 antagonistic genes were identified during seedling growth. Eleven of these were found from control vs treatment 2, and together with the plant growth mechanism, played a regulatory role in tomato growth. The prediction mechanism diagram show that tomato seedlings in ‘3–5’ induced more antagonistic genes in the stimulus-related pathway ( such as ABA-related genes, hormone-related genes and some TFs) and growth-related pathway. The combination of all genes made the substrate of treatment 2 more suitable for planting tomato seedlings in winter greenhouse conditions than that of treatment 1 and control group. This study also presents a novel approach to utilizing corn straw resources and provides a theoretical foundation for substituting traditional turf with corn straw in substrates.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Foundation of Liaoning Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2023-XCZX-A2-044 and 22-319-2-29) and Transfer of the Right to use Technology for Harmless Treatment and Resource Utilization of Poultry Manure (2020210101001511).

Author contributions

Yilian Wang wrote the main manuscript text , Xinyu Zhang、Xuejing Du and Zhigang He participated in the design of experiment content and Zhibo Zhang prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Informatin with the primary accession code PRJNA979958. The KEGG license document has been obtained and uploaded to ‘Related Files’.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmed, N. et al. Advancing horizons in vegetable cultivation: a journey from ageold practices to high-tech greenhouse cultivation-a review. Front. Plant Sci.15, 1357153 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ainsworth, E. A. & Ort, D. R. How do we improve crop production in a warming world? Plant Physiol.154(2), 526–530 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aklima, J. et al. Effects of Matrix pH on spontaneous transient depolarization and reactive oxygen species production in Mitochondria. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 692776 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alhaithloul, H. A. S., Galal, F. H. & Seufi, A. M. Effect of extreme temperature changes on phenolic, flavonoid contents and antioxidant activity of tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L). PeerJ 9, e11193 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilal, S. et al. Silicon-induced morphological, biochemical and molecular regulation in Phoenix dactylifera L. under low-temperature stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24(7), 6036 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolognini, D., Bartalucci, N., Mingrino, A., Vannucchi, A. M. & Magi, A. NanoR: a user-friendly R package to analyze and compare nanopore sequencing data. PLoS One 14(5), e0216471 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, H. et al. A comparison of the low temperature transcriptomes of two tomato genotypes that differ in freezing tolerance: Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum habrochaites. BMC Plant. Biol.15, 132 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng, F. et al. Redox signaling and CBF-responsive pathway are involved in salicylic acid-improved photo synthesis and growth under chilling stress in watermelon. Front. Plant Sci.7, 1519 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbineau, F., Taskiran-Özbingöl, N. & El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. Improvement of seed quality by priming: Concept and biological basis. Seeds 2, 101–115 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuevas, J. C. et al. Putrescine is involved in Arabidopsis freezing tolerance and cold acclimation by regulating abscisic acid levels in response to low temperature. Plant Physiol.148(2), 1094–1105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diver, S. Organic greenhouse vegetable production. J. Am. Assoc. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 14(1), e32 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong, H. et al. Genome-wide identification of PbrbHLH family genes, and expression analysis in response to drought and cold stresses in pear (Pyrus Bretschneideri). BMC Plant Biol.21(1), 86 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrell, M. & Jones, D. Food waste composting: its use as a peat replacement. Waste Manag.30, 1495–1501 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frerichs, C., Daum, D. & Pacholski, A. S. Ammonia and ammonium exposure of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) growing in an organically fertilized peat substrate and strategies to mitigate related harmful impacts on plant growth. Front. Plant Sci.10, 1696 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong, X. et al. Characterizing corn-straw-degrading actinomycetes and evaluating application efficiency in straw-returning experiments. Front. Microbiol.13, 1003157 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong, Z., Xiong, L., Shi, H., Yang, S. & Zhu, J. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci.63(5) (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Gruda Schnitz1er, Roeber. The influence of organic substrate on growth and physiological parameters of vegetable seedlings. Actahort 450, 487–494 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao, Y., Zong, X., Ren, P., Qian, Y. & Fu, A. Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors regulate a wide range of functions in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22(13), 7152 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He, X. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis revealing the potential mechanism of low-temperature stress in Machilus microcarpa. Front. Plant Sci.13, 900870 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, Z. et al. Screening and isolation of cold-adapted cellulose degrading bacterium: a candidate for straw degradation and De novo genome sequencing analysis. Front. Microbiol.13, 1098723 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honfi, P. et al. Salt tolerance of Limonium Gmelinii subsp. Hungaricum as a potential ornamental plant for secondary salinized soils. Plants (Basel)12(9), 1807 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaglo, K. et al. Components of the Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration-responsive element binding factor cold-response pathway are conserved in Brassica napus and other plant species. Plant Physiol.127(3), 910–917 (2001). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin, R. et al. Comparative transcriptome and interaction protein analysis reveals the mechanism of IbMPK3-overexpressing transgenic sweet potato response to low-temperature stress. Genes (Basel) 13(7), 1247 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28(1), 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, C., You, Q. & Zhao, P. Genome-wide identification and characterization of SPX-domain-containing protein gene family in Solanum lycopersicum. PeerJ 9, e12689 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu, Q. et al. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10(8), 1391–1406 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Könönen, J. Straková, Heinonsalo, Laiho, Kusin, Limin,Vasander. Deforested and drained tropical peatland sites show poorer peat substrate quality and lower microbial biomass and activity than unmanaged swamp forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 123 (2018).

- 28.Ngo, H. T. T. & Cavagnaro, T. R. Interactive effects of compost and pre-planting soil moisture on plant biomass, nutrition and formation of mycorrhizas: a context dependent response. Sci. Rep.8(1), 1509 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozawa, K., Yamamura, M. & Okada, M. Rice-chaff and soil composite as a culture medium for vegetable seedlings. Acta Hortc. 407–412 (1992).

- 30.Paradza, V. M. et al. Endophytic colonisation of Solanum lycopersicum and Phaseolus vulgaris by fungal endophytes promotes seedlings growth and hampers the reproductive traits, development, and survival of the greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum. Front. Plant. Sci.12, 771534 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu, Z. et al. The tomato Hoffman’s anthocyaninless gene encodes a bHLH transcription factor involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis that is developmentally regulated and induced by low temperatures. PLoS One 11(3), e0151067 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma, M., Laxmi, A. & Jasmonates Emerging players in controlling temperature stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci.6, 1129 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen, J. et al. The mechanism of abscisic acid regulation of wild fragaria species in response to cold stress. BMC Genom.23(1), 1–17 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steven, V. Nathan, Deppe, Debra, Berhow. Extracted sweet corn tassels as a renewable alternative to peat in greenhouse substrates. Ind. Crops Prod.33(2) (2011).

- 35.Tamburino, R. et al. Cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) suffered a severe cytoplasmic bottleneck during domestication: implications from chloroplast genomes. Plants (Basel) 9(11), 1443 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas, P. D. et al. Gene ontology causal activity modeling (GO-CAM) moves beyond GO annotations to structured descriptions of biological functions and systems. Nat. Genet.51(10), 1429–1433 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traw, M. B. & Bergelson, J. Interactive effects of jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, and gibberellin on induction of trichomes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol.133(3), 1367–1375 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van-Buskirk, H. A. & Thomashow, M. F. Arabidopsis transcription factors regulating cold acclimation. Physiol. Plant 126, 72–80 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaughn, S., Byars, J. & Jackson, M. Tomato seed germination and transplant growth in a commercial potting substrate amended with nutrient-preconditioned eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana L.) wood biochar. Sci. Hortic.280, 280 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaughn, S., Deppe, A., Palmquist, E. & Berhow, A. Extracted sweet corn tassels as a renewable alternative to peat in greenhouse substrates. Ind. Crops Prod.33(2), 514–517 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wai, A., Cho, L., Waseem, M., Lee, D. & Chung, M. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of Alba gene family members in response to abiotic stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L). BMC Plant. Biol.21(1) (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Wang, F. et al. Crosstalk of PIF4 and DELLA modulates CBF transcript and hormone homeostasis in cold response in tomato. Plant Biotechnol. J.18(4), 1041–1055 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, M., Hao, J., Chen, X. & Zhang, X. SlMYB102 expression enhances low-temperature stress resistance in tomato plants. PeerJ 8, e10059 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wersebe, M. et al. The effects of different cold-temperature regimes on development, growth, and susceptibility to an abiotic and biotic stressor. Ecol. Evol.9(6), 3355–3366 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu, D. et al. Light and abscisic acid coordinately regulate greening of seedlings. Plant Physiol.183(3), 1281–1294 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, W. et al. The grapevine basic helix -loop -helix (bHLH) transcription factor positively modulates CBF -pathway and confers tolerance to cold -stress in Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Rep.41(8), 5329–5342 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, X. et al. DlICE1, a stress-responsive gene from Dimocarpus longan, enhances cold tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem.142, 490–499 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, J. et al. Salicylic acid-induced antioxidant protection against low temperature in cold-hardy winter wheat. Acta Physiol. Plant 38, 261 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, C. et al. Regulation effects of seedling raising by melatonin and methyl jasmonate substrate on low temperature stress tolerance in rice. Acta Agron. Sin.48(8), 2016–2027 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuo, Z. et al. Zoysia japonica MYC type transcription factor ZjICE1 regulates cold tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Sci.289, 110254–111102 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang An, L. et al. Ping Zheng, Research progress of bHLH gene family in plants and its application prospects in medical plants. Biotechnol. Bull.39(10), 1–16 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geng, D. et al. Regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis by MdMYB88 and MdMYB124 contributes to pathogen and drought resistance in apple. Hortic. Res.7, 102 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Informatin with the primary accession code PRJNA979958. The KEGG license document has been obtained and uploaded to ‘Related Files’.