Abstract

Background

The global research on pandemics or epidemics and mental health has been growing exponentially recently, which cannot be integrated through traditional systematic review. Our study aims to systematically synthesize the evidence using natural language processing (NLP) techniques.

Methods

Multiple databases were searched using titles, abstracts, and keywords. We systematically identified relevant literature published prior to Dec 31, 2023, using NLP techniques such as text classification, topic modelling and geoparsing methods. Relevant articles were categorized by content, date, and geographic location, outputting evidence heat maps, geographical maps, and narrative synthesis of trends in related publications.

Results

Our NLP analysis identified 77,915 studies in the area of pandemics or epidemics and mental health published before Dec 31, 2023. The Covid pandemic was the most common, followed by SARS and HIV/AIDS; Anxiety and stress were the most frequently studied mental health outcomes; Social support and healthcare were the most common way of coping. Geographically, the evidence base was dominated by studies from high-income countries, with scant evidence from low-income counties. Co-occurrence of pandemics or epidemics and fear, depression, stress was common. Anxiety was one of the three most common topics in all continents except North America.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest the importance and feasibility of using NLP to comprehensively map pandemics or epidemics and mental health in the age of big literature. The review identifies clear themes for future clinical and public health research, and is critical for designing evidence-based approaches to reduce the negative mental health impacts of pandemics or epidemics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s44197-024-00284-8.

Keywords: Pandemics, Epidemics, Mental health, Natural language processing, Systematic mapping

Background

Pandemics or epidemics have profound consequences for mental health [1], a state characterized by the performance of mental functions, resulting from an adjustment of the individual to his environment or society [2]. It encompasses various aspects such as emotional regulation, resilience, and the capacity to adapt to the changing circumstances brought about by global dynamics [2]. The ease of global travel, intensified international exchanges, and shifts in climate patterns have not only accelerated the spread of infectious diseases but also heightened awareness of mental health challenges during such times [3, 4]. COVID-19, first identified in Wuhan, China, in Dec 2019, has affected numerous regions, highlighting the necessity for a mental health perspective in public health strategies [5]. As of Sep 1st, 2023, the substantial figures of over 770 million confirmed cases and over 6.9 million deaths have been reported globally [6]. Extremely strict pandemic prevention measures, such as mandatory school closures and the suspension of nonessential productions and business activities, as well as the spread of emotions through channels like social media, are seriously affecting people’s daily life and emotions [7, 8].

Pandemics or epidemics have resulted in widespread contagion and lockdown, signifying the widespread emotional and mental impacts that require attention [9, 10]. Given the lack of specific treatments for the mental health effects of pandemic [11], some countries are adopting mitigation strategies to reduce the impact of the virus and alleviate the psychosocial distress arising from lockdown measures [12, 13]. However, these strategies, while aimed at protecting the most vulnerable such as the older adults or those with chronic/psychiatric illnesses [14], also introduce additional panic, stress, fear and associating with anxiety, frustration, anger, depression and several other mental disorders among the general public [15, 16]. Furthermore, certain groups such as the children [17], the health-care workers [18], the unemployed and those frequently exposed to social media/news [19] might report certain degrees of mental distress. It requires a targeted approach to address consequent mental health challenges in both clinical settings and among the general public.

Our systematic search of the literature has revealed several detailed and specific reviews that have focused on a specific pandemic, particular at-risk groups or specific aspects of mental health [20–24]. To our knowledge, there has not been an encompassing systematic review that synthesizes the diverse and broader implications of pandemics or epidemics on mental health across various segments of the population. In order to identify the links between pandemics or epidemics and mental health, and to enable health-promoting responses, the scientific evidence base must be updated in a timely and regularly manner. Two factors limit the effectiveness of such evidence reviews. First, research on pandemics or epidemics and mental health cuts across a variety of disciplines and represents a fragmented picture of niche discourses, that impedes efforts to synthesize key insights and identify trends and evidence gaps. Second, the exponential growth of literature means that traditional evidence synthesis methods, which usually require considerable human resources to manually collate and screen literature, may be no longer sufficient or feasible [25]. Therefore, the response of existing evidence is to narrow the scope of literature review, which further reduces the potential for broader insights across disciplines.

In the landscape of expansive literature, there is a pressing demand for innovative methodologies that can offer systematic and expeditious synthesis of the existing body of knowledge [26]. Traditional review methods may be constrained by the sheer volume of data, resulting in a less comprehensive understanding of the subject at hand. In stark contrast, natural language processing (NLP) can rapidly screen and encode potentially hundreds of thousands of articles, increasing the breadth and diversity of the literature [27]. Given the devastating impacts of coronavirus, evidence synthesis about mental health outcomes is needed to produce guidance for health care institutions and the public. The purpose of this review is to use NLP methods (supervised and unsupervised) to systematically synthesize evidence on pandemics or epidemics and mental health. We also aim to identify key indicators from our systematic synthesis that can inform the development of targeted preventative interventions. In doing so, we hope to provide the first comprehensive, semi-automated systematic map of the scientific literature on pandemics or epidemics, mental health impacts, and relevant coping strategies, ultimately contributing to timely public health responses and mental health interventions.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

NLP approaches were used to systematically synthesize evidence on the links between pandemics or epidemics and mental health globally [28]. The analysis involved five steps: defining the framework, database searching, screening, supervised and unsupervised machine learning, and generating topic maps and heatmaps.

We focused on literature from different geographical contexts, and assessed the distribution of literature based on country income status, using the 2020 World Bank income classification rankings to define low-income, lower middle-income, upper middle-income, and high-income nations [29].

We included all empirical study designs published and indexed in English between Jan 1, 2014, and Dec 31, 2023. We searched Embase, PubMed, Scopus, PsycInfo, and Web of Science Core Collection using title, abstract, and keywords only. Full texts were not retrieved, screened, or analyzed. Grey literature was not included. The search strings are described in detail is in Supplementary File 1.

Screening

Screening was done based on titles and abstracts using a combination of manual assessment against priori inclusion criteria and machine learning methods. For inclusion, documents had to meet the following criteria: (1) be indexed in English; (2) be published between Jan 1, 2014, and Dec 31, 2023; (3) provide a clear link to the actual, projected, or perceived impacts of pandemics or epidemics, or responses to reduce the impacts of pandemics or epidemics; (4) include substantial focus on a perceived, experienced, or observed eligible mental health outcomes; (5) present empirically driven research or a review of such research. Correspondingly, our exclusion criteria included: (1) Non-English language documents; (2) Documents outside the 2014–2023 publication range; (3) Documents lacking a clear thematic focus on either pandemics or epidemics or mental health outcomes; (4) Non-empirical or non-peer-reviewed documents, such as opinion pieces, editorials, and news articles.

We used a supervised NLP method to accelerate screening. This involves training a computer algorithm on a human-labelled dataset to learn human decisions on screening documents [30]. We did this through two separate classification tasks: one is to predict whether the document is relevant to pandemics or epidemics; the other is to predict whether it is related to mental health. Since the positive data would be sparse (about 5%), we used the most advanced unsupervised learning to filter out more likely positive data for labelling [31]. We manually screened a training sample by title and abstract (500 unique documents), and coded them as relevant to pandemics or epidemics/mental health categories, or any combination of both. This human-screened sample set was used to train the classification models. For the remaining un-labelled documents, the two classification models were employed to filter out the documents related to both natural disasters and health.

To be exact, the task of labelling the dataset was entrusted to a team of experienced research assistants, under the supervision of principal investigators. The labelling process was performed according to pre-established criteria that we had meticulously defined. These criteria include keywords, research focus, and specific terminology associated with pandemics or epidemics and mental health. Training sessions were conducted to homogenize the understanding of these criteria among all labellers. Discrepancies were resolved through group discussions to reach consensual decisions. A consistent approach was ensured by pilot-testing the labelling process with a subset of the whole dataset, refining the criteria and protocols as needed. A common labelling guideline was established based on this pilot test, detailing the precise operational definitions for “pandemics or epidemics” and “mental health” in terms of document relevance.

We used the most advanced language model, the BERT model (uncased base setting) as the backbone of the classification, and evaluated its performance by the f1 score [32]. It is generally recognized within the scientific community that an f1 score in the range of 0.8 to 0.9 is indicative of acceptable performance for classification tasks relating to complex phenomena. Moreover, an f1 score exceeding 0.9 is commonly regarded as reflecting excellent performance. In the pandemics or epidemics classification task, the model achieved a 0.94 f1 score in its test set and a 0.84 f1 score for mental health classification task. These results are above the benchmarks for good performance, suggesting that our model is delivering high-quality and reliable classifications across both domains. For the documents predicted positive by both models, we manually reviewed 100 documents to recheck the overall performance of the model, and 91% of them met our above inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Analysis

We extracted the bibliographic meta-data for all documents retrieved by search strings. To determine where studies were conducted, we used a pre-trained geoparser to identify geographical locations in abstracts and titles [33]. Detailed literature section process is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

We used unsupervised NLP and topic modelling to support analysis of literature included in this review. Topic modelling is a method that automatically identifies clusters of words that frequently occur together based on a pre-specified number of topics [34]. The themes generated by topic modelling are not based on any human labelling or tagging, but on structures found by the algorithm in the data itself. An article is typically associated with more than one topic. To find the most relevant and explicable topic model, we qualitatively compared several alternative topic models, including non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) [35], latent dirichlet allocation (LDA) [36], guided LDA, and BERTopic from 40 to 80 topics and various hyperparameters. Non-negative matrix factorization with 45 topics provided the best balance between detail and interpretability. We then implemented the NMF by the Scikit Learn package [37]. We iteratively reviewed the topics emerging from topic models to identify and label key thematic clusters that were then validated within the study team and with external experts to ensure that final topics were streamlined with the expert’s understanding of the literature. The topics of the final topic model were designated to one of three aggregated meta-topics: pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, coping & responses (Supplementary File 2).

We generated topic maps based on outcomes of the topic model and created heat maps to visualize the relative co-occurrence of topics. The topic map reflects a conceptual space where similar documents are placed closer together and dissimilar documents are farther apart. Thus, clusters of dots represent areas of literature with similar topic scores. We identified the most and least frequent topics from all topics in our topic model by the global region for key meta-topics. We generated geographical maps to visualize locations of studies globally. We used narrative synthesis to assess the frequency of key topics in literature on pandemics or epidemics and mental health, as well as the extent of co-occurrence of topics within the topic and heat maps. We assessed the extent to which trends in the literature differed by country income class.

Results

Literature Growth and Spatial Concentration

Our findings showed that literature on a broad spectrum of pandemics/epidemics and mental health has been growing substantially since 2020 (Fig. 1A). Based on our criteria, we identified 77,915 studies in the field of pandemics or epidemics and mental health published by Dec 31, 2023 and indexed in Embase, Pubmed, Scopus, PsyciInfo, or Web of Science Core Collections. In 2023, 27,831 relevant studies were retrieved and included—around 4.5 times as many as in 2020. However, only less than 100 studies were retrieved per year before 2020.

Fig. 1.

(A) Descriptive summary of included articles in 2014–2023 by publication year. (B) Descriptive summary of included articles by country income group, continent, and country

31,358 (76.56%) of 40,957 studies on pandemics or epidemics and mental health with identified place names focused on high-income and upper middle-income nations (Fig. 1B). Publications on pandemics or epidemics and mental health showed a large gradient by national income group. The number of publications from high-income nations was 1.7 times greater than that in upper middle-income nations, and far exceeded that from low-income nations. When places mentioned were combined by country for each paper, we found that 14,511 (35.43%) of the 40,957 locations were in Asia, followed by 12,274 (29.97%) in Europe and 7,120 (17.38%) documents in North America. In terms of specific countries, 3,827 (11.25%) of the 34,008 locations were in China, 2,581 (7.59%) in the USA, and 2,314 (6.80%) in Great Britain.

Topic Modelling and Topic Distribution

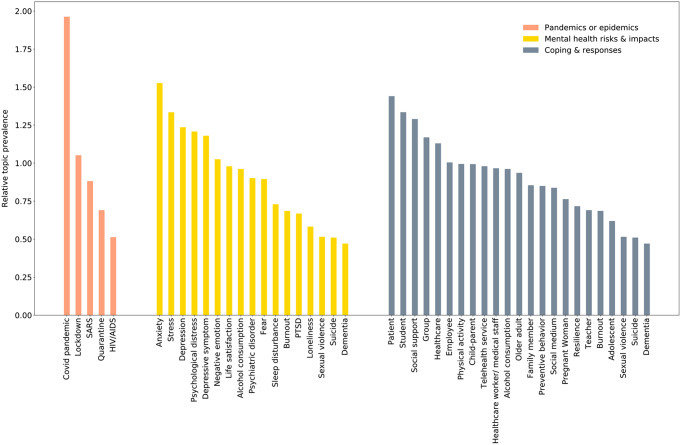

Through topic modelling, we mapped pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, and coping & responses across the global. Topics with their relative prevalence in the literature are shown in Fig. 2, grouped by pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, and coping & responses. The axis is a normalized scale reflecting topic prevalence relative to the mean score (reference = 1). Topics were identified by the words used in titles, keywords, and abstracts, and could thus reflect several meanings. The Covid pandemic and SARS were the most frequently studied pandemics or epidemics, followed by HIV/AIDS. Anxiety and stress were the most frequently studied mental health outcomes. Social support and healthcare were the most common ways of coping. Patients, healthcare workers, students and older adults were the special population that are vulnerable to mental health problems caused by epidemics. Full lists of topics and words associated with these topics are in the Supplementary File 2.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of topics within included articles, organized by meta-topic

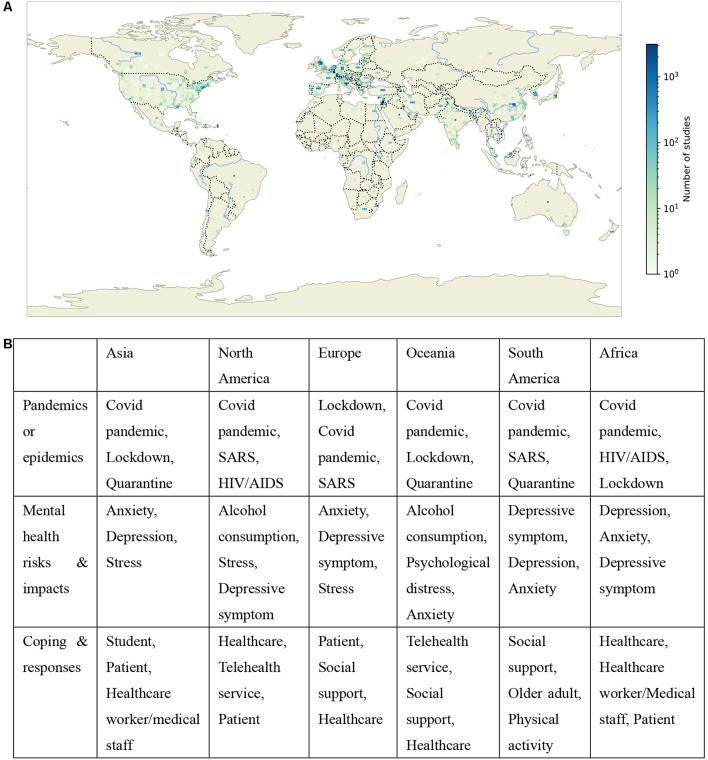

Figure 3A shows global geographical distribution of included studies. For studies conducted at the national level, points appear in the geographic center of the region or country. The topics with the highest frequency by region (top three topics) are shown in Fig. 3B. Most reported pandemics or epidemics included Covid (19,770 [48.27%]), SARS (7,499 [18.31%]), and HIV/AIDS (2,301 [5.62%]). The Covid pandemic was among the top three topics in all continents. Lockdown or quarantine was among the top three topics in continents except North America. Literature published in North America and Africa more frequently reported HIV/AIDS compared with other regions.

Fig. 3.

(A) Global geographical distribution of included studies. (B) Most frequent topics by region and category

Various mental health outcomes were reported—including anxiety (5,431 [13.26%] articles), stress (4,427 [10.81%]), depression (3,236 [7.90%]), and psychological stress (3,510 [8.57%]) (Figs. 2 and 3). Anxiety was one of the three most frequent topics in all continents except North America. Depression was among the top three topics in all continents except Oceania. Alcohol consumption was the most frequent mental health topic in North America and Oceania. Oceania presented a different pattern, in that psychological distress was the most prevalent mental health topic.

In the existing coping & responses literature, patients (3,313 [8.09%] of all 40,957 articles) were the most frequently studied objects. Studies also focused on students (2,502 [6.11%]), child-parent (1,618 [3.95%]), healthcare workers/medical staff (1,311 [3.20%]), etc. Social support was the most common way of coping & responses (2,920 [7.13%] of all 40,957 articles), followed by healthcare (2,552 [6.23%]) and physical activities (1,682 [4.11%]). Patients, healthcare workers/medical staff, students, and older adults were the most common subjects in most continents. Healthcare or telehealth services were common ways of coping in all continents except South America. Social support was a frequent topic in Europe, Oceania, and South America.

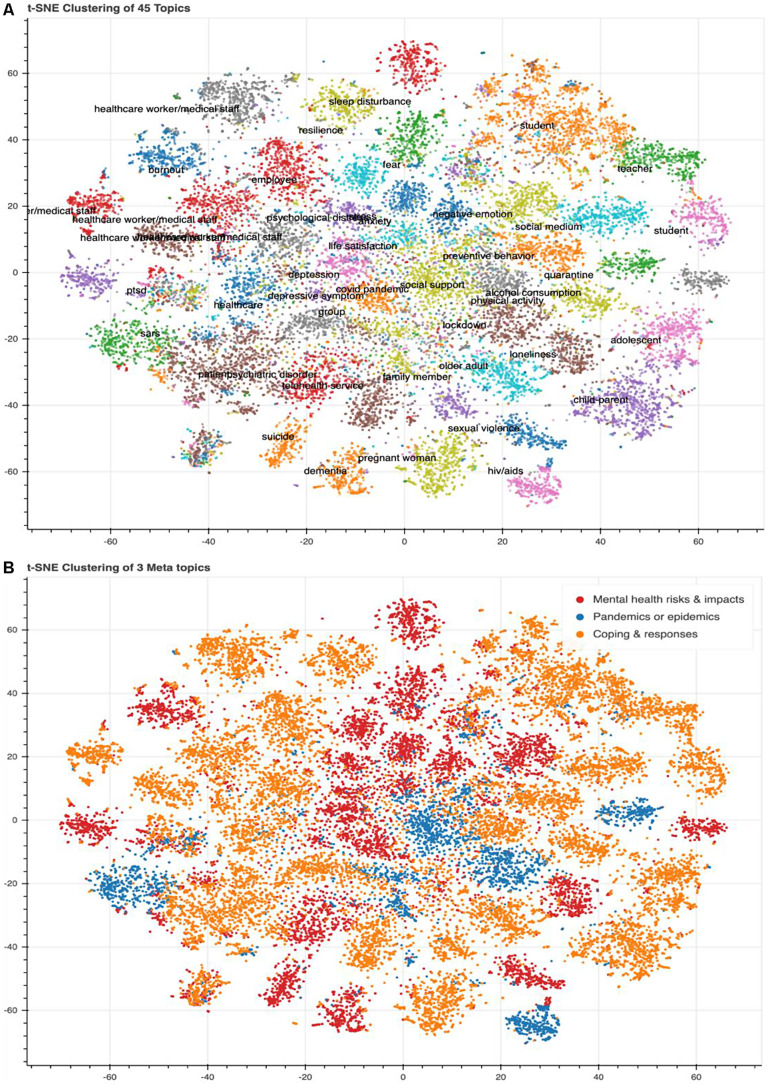

Topic Aggregation and Dimensional Representation

We mapped all articles in the dataset based on the similarity of topics within documents—i.e., distinguishing documents based on their aggregated meta-topic: pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, or coping & responses (Fig. 4). The topic map showed a large number of topic clusters, offering a nuanced view of the complex interactions between pandemics, mental health, and societal coping mechanisms. It included several focusing on specific mental health outcomes (e.g., anxiety, depression, loneliness, and stress) that were highly clustered and separate from other topics, demonstrating the unique and distinct impact of pandemics on these particular mental health outcomes. Pandemics or epidemics-related topics, such as Covid, SARS, and HIV/AIDS, also showed distinctive clustering. Clusters associated with coping and responses, including themes like social support, resilience, and healthcare responses, were also manifested.

Fig. 4.

(A) Visualization of topics in the dataset. The graphic reflects a conceptual space where similar documents are placed closer together, and dissimilar documents are farther apart. Clusters of dots represent areas of literature that have similar topic scores, meaning that they use similar words and are presumed to be about related subjects. Labels show the most frequent topics. (B) Pandemics or epidemics and mental health research categories in the dataset. Topic map in which each dot represents a document, colored according to the categories of pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, or coping & responses

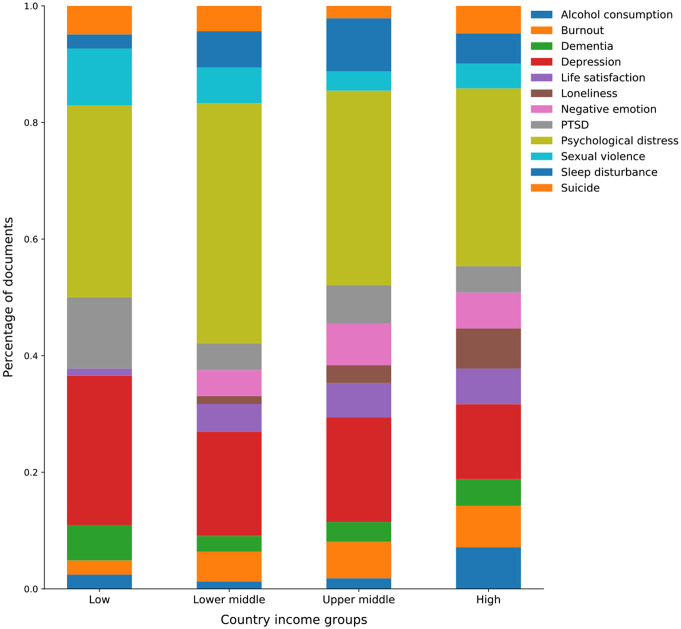

In Fig. 5, with higher national income level, there was a lower frequency for depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and sexual violence, and an increasing frequency for loneliness, negative emotion, life satisfaction, suicide, and sleep disturbance. Literature from high-income regions mostly focused on the effects of pandemics or epidemics on psychological distress, depression, sleep disturbance, suicide, alcohol consumption, and burnout. In low-income regions, the literature on pandemics or epidemics and mental health was dominated by psychological distress and depression, with particular attention paid to research on PTSD, sexual violence and dementia.

Fig. 5.

Frequency of mental health risk and impact topics for countries in different income classes. Data are from documents on mental health impacts per country income group, subdivided by aggregated topic as a percentage of the group total

Topic Co-occurrence and Demographic Implications

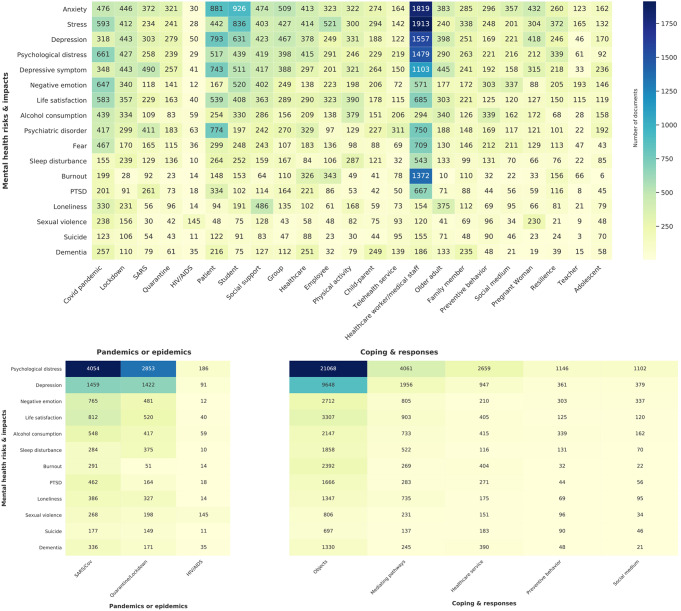

We assessed the co-occurrence of topics by pandemics or epidemics, mental health risks & impacts, and coping & responses categories, with results shown as heat maps (Fig. 6). Co-occurrence of pandemics or epidemics and mental health topics was common, reflecting to a large extent the dominant pathways leading pandemics or epidemics to health risks. Among specific topics, the Covid pandemic was a frequently reported topic in articles on psychological distress, negative emotion, stress, and life satisfaction. SARS most frequently co-occurred with studies of depressive symptoms, psychiatric disorder, and anxiety. HIV/AIDS co-occurred frequently with sexual violence.

Fig. 6.

Co-occurrence of pandemics or epidemics, coping & responses, and mental health risks & impacts. Number of documents with co-occurring topics above threshold 0.015

Healthcare workers or medical staff suffered most from mental health problems, such as stress, anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and burnout. Patients and students frequently suffered from anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and psychiatric disorder during or after pandemics or epidemics. Older adults also suffered much from loneliness, which was often mitigated by social support. Social support, healthcare services and physical activities were common responses to mental health problems, reflecting the potential effects of responses leading to pandemics or epidemics recovery.

Discussion

Infectious diseases such as the SARS and the Covid pandemic have a major impact on global health. Existing evidence must be kept up to date to better respond to future outbreaks of infectious diseases. Available research revealed that 40,957 studies, mainly from high-income countries, explored the relationship between pandemics or epidemics and mental health. The Covid pandemic was the most common topic, followed by SARS and HIV/AIDS. Pandemics or epidemics can lead to mental health problems, such as anxiety, stress, fear, and depression. Social support, healthcare services and physical activities were the most common ways of coping. Patients, healthcare workers, students and older adults were the vulnerable group studied. The findings reflected the overview of existing research on pandemics or epidemics and mental health, and also highlighted their recovery responses.

The Covid pandemic has emerged as a principal theme from our analysis, with its profound and multifaceted reverberations on various societal strata [38]. This is closely followed by SARS and HIV/AIDS. They have not only shaped the global health narrative over the past two decades but also significantly influenced the mental landscape, bridging virulent pathogens with emotional upheaval [39, 40]. These conditions, being marked by their contagious and far-reaching impacts, evoke profound communal and individual anxiety, leading to a spectrum of mental health issues, embattling individuals with anxiety, stress, fear, loneliness, and depression [41]. Especially noteworthy is the precipitous rise in stress and fear, both acute responses to novel and life-threatening situations. However, if unmitigated, can evolve into chronic mental conditions [42]. Simultaneously, the pervasive sense of uncertainty during pandemics often molds the fertile ground in which depression takes root, fertilizing feelings of hopelessness and lethargy [43].

Our findings underscore the importance of social support, healthcare services, and physical activities as fundamental coping mechanisms against mental health adversities arising during pandemics. These elements were found to be key to recovery responses, providing significant support to the affected population. Specifically, social support stands out as a critical factor, not only in mitigating immediate distress but in fostering a sense of community and resilience among individuals [44]. Social connections provide an essential platform for sharing experiences and solutions, crucial for mental health [45]. Furthermore, healthcare services, in traditional and telehealth formats, play an indispensable role in ensuring continuous care and monitoring for individuals’ mental health, especially for those in isolation or quarantine [46]. Physical activities are also come to the forefront as a supportive element in combating mental health issues. By promoting physical health, these activities inherently contribute to mental health by reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and enhancing mood [47].

The multifaceted approach to addressing mental health challenges highlights the need for a collaborative and community-oriented strategy, particularly during times of crisis. For general population affected by epidemics or pandemics, a comprehensive assessment of risk factors leading to mental problems is needed, such as pre-crisis mental health status, trauma, or bereavement [10]. Moreover, tailoring support to different population segments, especially mental interventions for vulnerable and exposed groups, is imperative [48]. For patients and healthcare workers who are dealing with the direct health impacts of a pandemic, the focus might lean towards medical support integrated with mental care [49, 50]. For students, disruptions in education and the loss of routine can be mitigated through online platforms and mental health support systems provided by educational institutions [51]. The older adults, who might face isolation more acutely, require specific attention physically and emotionally [52]. The synthesis of our research points towards the necessity of a robust, adaptable, and inclusive framework for mental health support during times of pandemic.

Compared with existing work, our NLP-automated mapping study provided more comprehensive evidence on the pandemics or epidemics and mental health. Traditional reviews face challenges in processing the sheer volume of literature as efficiently as NLP methods, which can systematically and swiftly integrate the existing large number of studies, especially considering the advancements in supervised algorithms for enhanced accuracy and relevance [53]. Merging the precision of human expertise with the scalability of machine learning algorithms is an essential step in training robust machine learning models to accurately reflect human decision-making [54]. At the same time, the automated procedure vastly outpaces traditional manual methods, leading to a more efficient identification of trends, patterns, and relationships across diverse studies [55]. Moreover, NLP can automate and improve the classification and theme extraction process, allowing the exploration of broader research scopes, thus facilitating a more comprehensive and precise synthesis of evidence [56]. It also mitigates the variability inherent in individual human assessments, especially over large datasets.

However, given the magnitude of the literature and the constraints of a high-level systematic synthesis using NLP, we only relied on abstracts, titles, and keywords for analyses. Not retrieving full texts may potentially lead to the exclusion of nuanced details and context-specific findings present in the full texts. In addition, we did not include grey literature because it is still difficult to integrate systematically using NLP methods. Finally, we limited our search to English-indexed studies. The resulting evidence map, for example, had little evidence in Oceania and South America, which may be partly related to language bias. Similarly, the over-representation of evidence in high-income and middle-income countries may be due to the focus on peer-reviewed publications.

Conclusions

Taken together, evidence accumulated so far confirms that pandemics or epidemics are having a significant mental impact on individuals. Our NLP-driven insights offer an opportunity to inform and guide clinicians and mental health professionals that potential risk and protective factors, as well as appropriate strategies are required to cope with public health emergencies such as pandemics. On the other hand, our reliance on meta-data highlights a growing need for NLP techniques in research synthesis. Integrating methodological rigor from systematic reviews with advanced NLP can accelerate the identification of cross-study patterns and relationships, a necessity in a rapidly growing literature space, and thus is essential for preparing for and mitigating the mental health impacts of pandemics or epidemics.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

XY conceptualized the study, collected and analyzed the data. XY and XW wrote and edited the manuscript. HL performed the experiments, supervised the project and helped in data curation and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This article is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72304070) and the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72234001).

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahmed N, et al. Mental health in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10(7):537–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fusar-Poli P, et al. What is good mental health? A scoping review. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenseth NC, et al. How to avoid a local epidemic becoming a global pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2023;120(10):e2220080120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Destoumieux-Garzón D, et al. Getting out of crises: Environmental, social-ecological and evolutionary research is needed to avoid future risks of pandemics. Environ Int. 2022;158:106915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, et al. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):568–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19–1 September 2023. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 6th]; https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---1-september-2023

- 7.Ayittey FK, et al. Economic impacts of Wuhan 2019-nCoV on China and the world. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crocamo C, et al. Surveilling COVID-19 emotional contagion on Twitter by sentiment analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ, 2020. 368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):300–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan Rains L, et al. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56:13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RM, et al. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parodi SM, Liu VX. From containment to mitigation of COVID-19 in the US. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1441–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedford J, et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blakey SM, et al. Posttraumatic safety behaviors: characteristics and associations with symptom severity in two samples. Traumatology. 2020;26(1):74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy E, et al. The effects of the pandemic on mental health in persons with and without a psychiatric history. Psychol Med. 2023;53(6):2476–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauhanen L, et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Volume 32. European child & adolescent psychiatry; 2023. pp. 995–1013. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Rana W, Mukhtar S, Mukhtar S. Mental health of medical workers in Pakistan during the pandemic COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020;51:102080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crocamo C, et al. Some of us are most at risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of depressive symptoms among healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Neurosci Biobehavioral Reviews. 2021;131:912–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau J, et al. Understanding the mental health impact of COVID-19 in the elderly general population: a scoping review of global literature from the first year of the pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2023;329:115516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäfer SK, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2023;52(9):afad170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao R, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2023;340:914–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee B et al. Impact of COVID-19 mitigations on anxiety and depression amongst university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Global Health, 2023. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Haddaway NR, et al. On the use of computer-assistance to facilitate systematic mapping. Campbell Syst Reviews. 2020;16(4):e1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hase V. Automated content analysis. Standardisierte Inhaltsanalyse in Der Kommunikationswissenschaft–standardized content analysis in Communication Research: Ein Handbuch-A Handbook. Fachmedien Wiesbaden Wiesbaden: Springer; 2022. pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakagawa S, et al. Research weaving: visualizing the future of research synthesis. Trends Ecol Evol. 2019;34(3):224–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garousi V, Bauer S, Felderer M. NLP-assisted software testing: a systematic mapping of the literature. Inf Softw Technol. 2020;126:106321. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2021 [cited 2022 April 14 th]; https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 30.Wang LL, Lo K. Text mining approaches for dealing with the rapidly expanding literature on COVID-19. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(2):781–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endert A, et al. The state of the art in integrating machine learning into visual analytics. In Computer Graphics Forum. Wiley Online Library; 2017.

- 32.Lee J-S, Hsiang J. Patent classification by fine-tuning BERT language model. World Patent Inf. 2020;61:101965. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halterman A. Mordecai: full text Geoparsing and Event Geocoding. J Open Source Softw. 2017;2(9):91. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesnikowski A, et al. Frontiers in data analytics for adaptation research: topic modeling. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Clim Change. 2019;10(3):e576. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nebgen BT, et al. A neural network for determination of latent dimensionality in non-negative matrix factorization. Mach Learning: Sci Technol. 2021;2(2):025012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasan M et al. Normalized approach to find optimal number of topics in Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). in Proceedings of International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering: Proceedings of TCCE 2020. 2021. Springer.

- 37.Géron A. Hands-on machine learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow. O’Reilly Media, Inc.; 2022.

- 38.Sohrabi C, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsieh K-Y, et al. Mental health in biological disasters: from SARS to COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(5):576–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Remien RH, et al. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. Aids. 2019;33(9):1411–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cénat JM, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins V, et al. COVID-19: from an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2021;58(5):297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allan NP, et al. Lonely, anxious, and uncertain: critical risk factors for suicidal desire during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021;304:114144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labrague LJ. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2021;29(7):1893–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saeri AK, et al. Social connectedness improves public mental health: investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Australian New Z J Psychiatry. 2018;52(4):365–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myers CR. Using telehealth to remediate rural mental health and healthcare disparities. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40(3):233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell SL, et al. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: a cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2019;16:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiang Y-T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(3):228–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuijfzand S, et al. Psychological impact of an epidemic/pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals: a rapid review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talevi D, et al. Mental health outcomes of the CoViD-19 pandemic. Rivista Di Psichiatria. 2020;55(3):137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaturvedi K, Vishwakarma DK, Singh N. COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: a survey. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;121:105866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lábadi B, et al. Psychological well-being and coping strategies of elderly people during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(3):570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qin X, et al. Natural language processing was effective in assisting rapid title and abstract screening when updating systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;133:121–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng C et al. Integrating machine learning with human knowledge. Iscience, 2020. 23(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Dornick C, et al. Analysis of patterns and trends in COVID-19 research. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;185:302–10. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benkassioui B et al. NLP methods’ information extraction for textual data: an analytical study. in International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development. 2022. Springer.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.