Abstract

Sterile neuroinflammation is a major driver of multiple neurological diseases. Myelin debris can act as an inflammatory stimulus to promote inflammation and pathologies, but the mechanism is poorly understood. Here, we showed that lysophosphatidylserine (LysoPS)-GPR34 axis played a critical role in microglia-mediated myelin debris sensing and the subsequent neuroinflammation. Myelin debris-induced microglia activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression relied on its lipid component LysoPS. Both myelin debris and LysoPS promoted microglia activation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines via GPR34 and its downstream PI3K-AKT and ERK signaling. In vivo, reducing the content of LysoPS in myelin or inhibition of GPR34 with genetic or pharmacological approaches reduced neuroinflammation and pathologies in the mouse models of multiple sclerosis and stroke. Thus, our results identify GPR34 as a key receptor to sense demyelination and CNS damage and promote neuroinflammation, and suggest it as a potential therapeutic target for demyelination-associated diseases.

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, GPCRs, Microglia

Subject terms: Inflammation, Neuroimmunology

Introduction

The inflammatory response includes infectious inflammation and sterile inflammation. In recent years, great progress has been made in elucidating the mechanisms of pathogen recognition by innate immune cells and many innate immune receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) have been identified [1–3]. Sterile inflammation is a form of pathogen-free inflammation caused by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) produced by tissue injury or cell death. Although the role of sterile inflammation in a variety of human diseases, such as neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular diseases, gout, and type 2 diabetes, is emerging, only a few DAMP-sensing receptors have been identified for now and the mechanism of innate immune recognition in sterile inflammation remains further investigated [4].

Sterile neuroinflammation creates a vicious cycle of uncontrolled inflammation and has been regarded as a major driver in the initiation or secondary injury development of multiple neurological diseases [5, 6]. Myelin debris, which is released from the damaged myelin sheaths during demyelination process of many neurological diseases, such as stroke, spinal cord injury (SCI), multiple sclerosis (MS), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and neurodegenerative diseases, can act as an inflammatory stimulus to activate innate immune cells and then promote inflammatory responses during disease progression [7, 8]. Myelin debris can be phagocytosed by microglia, other CNS macrophages, or endothelial cells and then promote them to produce TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and other inflammatory cytokines in vitro [7, 9–11]. Both myelin debris injection and tissue injury-induced myelin debris accumulation can induce inflammation in vivo by triggering microglia activation and inflammatory gene expression [11–13]. Consequently, the rate and extent of myelin debris clearance is essential for the inflammation resolution and effective tissue repair in MS, SCI, and other diseases [14–16]. Thus, these results indicate that myelin debris contains some DAMPs that can promote sterile inflammation and neurological pathologies, however, the mechanism of how myelin debris triggers innate immunity and neuroinflammation is poorly understood.

Here, we demonstrate that (LysoPS)-GPR34 axis is critical for microglia-mediated myelin debris sensing and the subsequent neuroinflammation. Through this mechanism, LysoPS production and GPR34 signaling play an essential role in microglia activation, neuroinflammation, and neurological pathologies during demyelination-associated animal models, such as MS and stroke.

Results

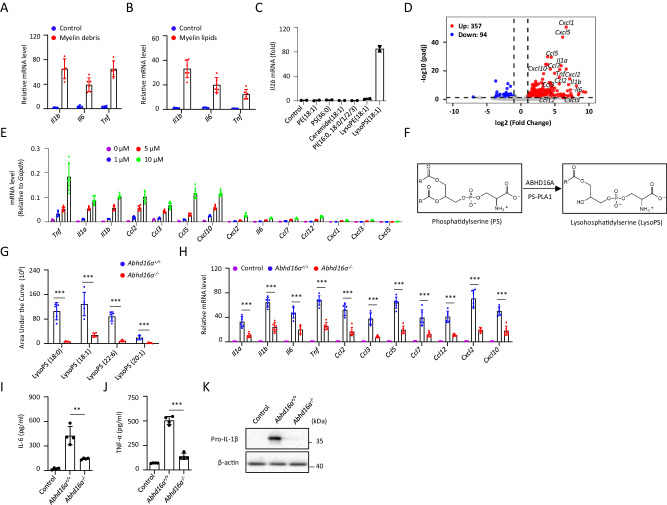

Myelin debris promotes microglia activation via its lipid component LysoPS

Microglia are the brain-resident macrophages and play a central role in regulating central nervous system (CNS) inflammation and homeostasis [17, 18]. Consistent with a previous report [9], treatment of primary cultured microglia (PM) from the brain of newborn mice with myelin debris induced their activation, resulting in the mRNA expression of some inflammatory cytokines or chemokines, including Il1b, Il6, and Tnf (Fig. 1A). Since lipids are the major components of myelin sheath and some lipids have been reported to act as DAMPs to stimulate innate immune response [4], we hypothesized that some lipid components of myelin debris might contribute to its immuno-stimulatory activity. Since lipids extracted from myelin contained some lipids that are not dissolved in culture medium, we coated these lipids on the plates to stimulate microglia. Similar with myelin debris, the crude myelin lipids also increased the mRNA expression of Il1b, Il6, and Tnf in PM (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Myelin debris activates microglia via LysoPS. The indicated genes expression in primary cultured microglia (PM) treated with myelin debris ((A), n = 6) or myelin lipids ((B), n = 6) for 4 h was measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR). C PM were stimulated with various lipids for 4 h and Il1b mRNA level was measured by qPCR (n = 2). D Volcano plot of the differentially expressed cytokines genes between PM treated with LysoPS for 4 h relative to normal PM, mapping the 357 upregulated genes (red circles) and 94 downregulated genes (blue circles). Black vertical lines highlight log fold changes of −2 and 2, and black horizontal line represents a padj of 0.05. E The indicated genes expression in PM treated with various doses of LysoPS for 4 h was determined by qPCR (n = 6). F Schematics of the enzymology of LysoPS production. G LC-MS/MS analysis of the relative amount of various LysoPS species in myelin debris from Abdh16a+/+ or Abhd16a−/− mice (n = 5). H qPCR analysis of the indicated genes in PM treated with myelin debris from Abdh16a+/+ or Abhd16a−/− mice for 4 h (n = 6). ELISA of IL-6 ((I), n = 4) or TNF-α ((J), n = 4) in supernatants and immunoblot analysis of the precursors of IL-β (pro-IL-1β) (K) in lysates from PM treated with myelin debris from Abdh16a+/+ or Abhd16a−/− mice for 18 h. Data are representative of three independent experiments (A–C, E) or two independent experiments (G–K). The P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (G, H) or one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (I, J). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

To identify the responsible lipid components, the crude myelin lipids were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and the top 40 lipids in abundance included 8 categories: dimethylphosphatidylethanolamine (dMePE), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), ceramide (Cer), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LysoPE), monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and LysoPS (Fig. S1A). PE, PS, Cer, LysoPE, PI, and LysoPS can be commercially obtained and we tested their immuno-stimulatory activity in PM. Among of them, LysoPS isoforms exhibited strong stimulatory activity for Il1b mRNA expression at the dose of 10 μM (Figs. 1C and S1B–D). We also found that LysoPS had no significant toxicity in microglia at the same dose (Fig. S1E). Moreover, we found that coated LysoPS showed much higher immuno-stimulatory activity for microglia (Fig. S1F). This might explain why myelin debris can stimulate microglia activation, although they contained low level of LysoPS isoforms (Fig. S1G).

We further used RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) to analyze the global gene expression patterns in LysoPS-stimulated PM. The volcano plot displayed a total of 357 up-regulated genes in LysoPS-treated PM (Fig. 1D). Metascape database analysis revealed that the differentially upregulated genes were markedly enriched in the regulation of cytokine production, regulation of defense response, cell activation, and inflammatory response (Fig. S1H) [19]. Among of them, the mRNA of proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine genes, including Tnf, Il1a, Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl5, Ccl7, Ccl12, Cxcl1, Cxcl3, Cxcl5, Cxcl10 and Cxcl12, were significantly upregulated (Fig. 1D). LysoPS-induced upregulation of proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine genes, including Tnf, Il1a, Il1b, Il6, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl5, Ccl7, Ccl12, Cxcl10 and Cxcl12, were also confirmed by qPCR analysis (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that myelin debris and its lipid component LysoPS can induce microglia to produce chemokines and cytokines.

We further investigated the role of LysoPS in myelin debris-induced microglia activation. PS-PLA1 and ABHD16A are the enzymes responsible for LysoPS generation from PS (Fig. 1F) [20, 21]. We found that Abhd16a was highly expressed in brain tissues, and myelin debris from Abhd16a−/− mice contained much less LysoPS (Figs. 1G and S1I–K). Compared with myelin debris from wild type mice, myelin debris from Abhd16a−/− mice had less activity to induce proinflammatory cytokine or chemokine mRNA expression in PM (Fig. 1H). Myelin debris-induced IL-6 and TNF-α secretion or pro-IL-1β expression in PM were also decreased when it was from Abhd16a−/− mice (Fig. 1I–K). We also found that LysoPS had no effects on myelin debris phagocytosis by PM (Fig. S1L, M). Thus, these results indicate that myelin debris-containing LysoPS is essential for its immuno-stimulatory activity.

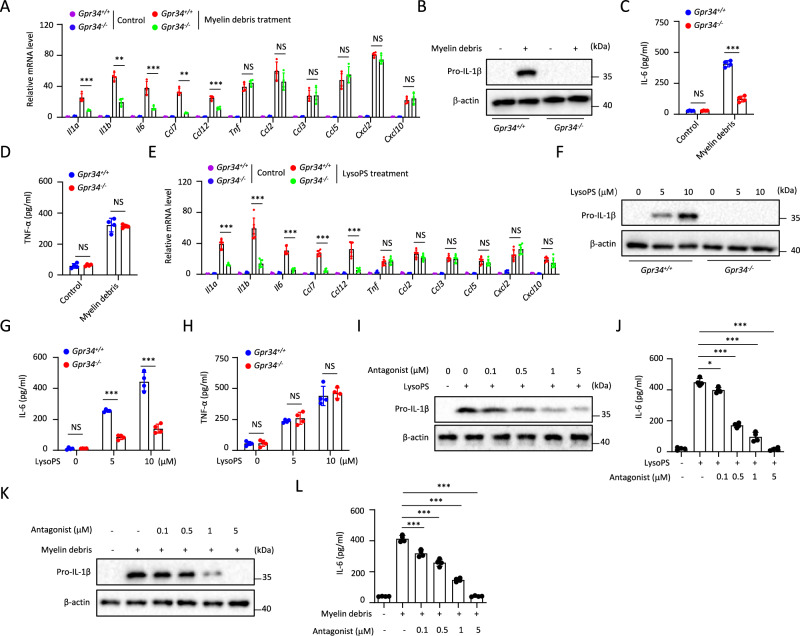

Myelin debris or LysoPS promotes microglia activation via GPR34

We next investigated how myelin debris and LysoPS activate microglia. Since three G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), GPR34, P2RY10, and GPR174 have been known to sense LysoPS [22, 23], we then examined the expression of these receptors in PM and found that Gpr34 was highly expressed, but P2ry10 or Gpr174 was not (Fig. S2A). These results were consistent with previous reports in which GPR34 has been identified as a signature gene in both mouse and human microglia [24–26]. Using a Gpr34 deficiency mice line generated by CRISPR-Cas9 technology [27], we found that myelin debris-induced expression of Il1a, Il1b, Il6, Ccl7, or Ccl12 was impaired in Gpr34−/− PM, but the expression of Tnf, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl5, Cxcl2 or Cxcl10 was not altered (Fig. 2A). The GPR34-dependent IL-1β or IL-6 expression and GPR34-independent TNF-α expression in myelin debris-treated PM were confirmed at protein level by western-blotting or ELISA assay (Fig. 2B–D). Similarly, LysoPS-induced expression of Il1a, Il1b, Il6, Ccl7 or Ccl12, but not the expression of Tnf, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl5, Cxcl2 or Cxcl10 was inhibited in Gpr34−/− PM (Fig. 2E–H). A synthetic GPR34 antagonist, which was reported in a patent by Takeda (US 20100130737), showed potent activity to inhibit myelin debris or LysoPS-induced IL-1β or IL-6 expression, and this activity was specific to GPR34 (Figs. 2I–L and S2B, C).

Fig. 2.

Myelin debris and LysoPS activate microglia via GPR34. A qPCR analysis to determine the indicated genes expression in Gpr34+/+ and Gpr34−/− PM treated with myelin debris for 4 h (n = 4). Immunoblot analysis of the pro-IL-1β in lysates (B) and ELISA of IL-6 ((C), n = 4) or TNF-α ((D), n = 4) in supernatants of Gpr34+/+ and Gpr34−/− PM stimulated with myelin debris for 18 h. E The indicated genes expression in Gpr34+/+ and Gpr34−/− PM treated with LysoPS for 4 h was measured by qPCR (n = 6). Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β in lysates (F) and ELISA of IL-6 ((G), n = 4) or TNF-α ((H), n = 4) in supernatants of Gpr34+/+ and Gpr34−/− PM treated with LysoPS for 18 h. Immunoblot analysis of the pro-IL-1β in lysates (I) and ELISA of IL-6 ((J), n = 4) in supernatants of PM pretreated for 30 min with various doses of GPR34 antagonist and then stimulated with LysoPS for 18 h. Immunoblot analysis of the pro-IL-1β in lysates (K) and ELISA of IL-6 ((L), n = 4) in supernatants of PM pretreated for 30 min with various doses of GPR34 antagonist and then stimulated with myelin debris for 18 h. Data are representative of three independent experiments (A, E) or two independent experiments (B–D, F–L). The P values were determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (A, C–E, G, H) or one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (J, L). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

Moreover, knockdown of GPR34 expression by shRNA in HMC3 cells, which were established through SV40-dependent immortalization of a human fetal brain-derived primary microglia, also suppressed myelin debris or LysoPS-induced Il1b and Il6 expression (Fig. S2D, E). LPS-induced IL-1β and IL-6 expression were not decreased in Gpr34−/− PM, suggesting that this effect is specific to myelin and LysoPS (Fig. S2F). Although a previous study showed that Gpr34−/− microglia had a little bit reduced phagocytosis activity in a fluorescence microscopy-based assay [28], we found that their ability to phagocytose myelin debris was normal in different time points by a quantitative FACS-based Assay (Fig. S2G). Myelin debris or LysoPS-induced expression of cytokines or chemokines were not changed in Gpr174−/− or P2ry10−/− PM (Fig. S2H, I). Thus, these results indicate that GPR34 is essential for microglia to sense myelin debris and the subsequent activation.

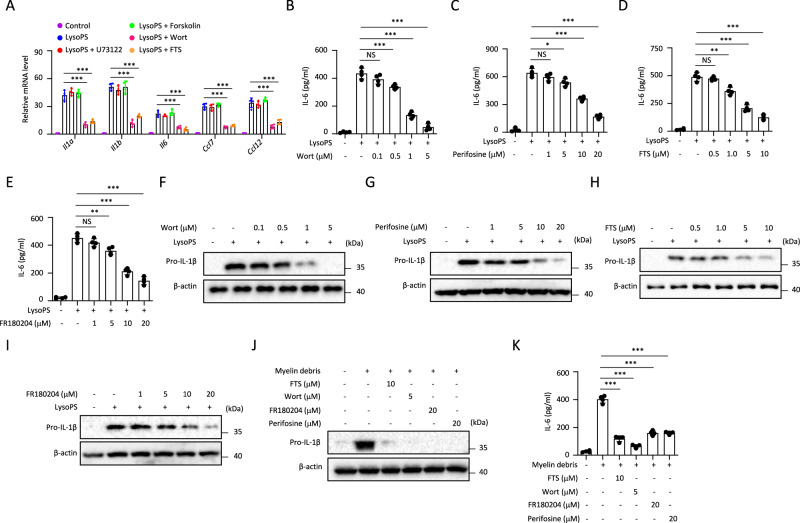

PI3K-AKT and RAS-ERK signaling pathways act the downstream of GPR34 to promote microglia activation

We further investigated GPR34 downstream signaling events involved in myelin debris or LysoPS-induced microglia activation. GPR34 is a Gi/o protein-coupled receptor and its activation results in the inhibition adenylyl cyclases and activation of the PLC-IP3/DAG, PI3K-AKT, and RAS-ERK pathways [29]. Our results showed that LysoPS-induced PM activation was dependent on PI3K-AKT and RAS-ERK pathways, because the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Wort), Ras inhibitor farnesyl thiosalicylic acid (FTS) could inhibit LysoPS-induced Il1a, Il1b, Il6, Ccl7 or Ccl12 expression in PM, but the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122 and adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin could not (Fig. 3A). Wort, AKT inhibitor perifosine, FTS or ERK inhibitor FR180204 also suppressed LysoPS-induced IL-6 and pro-IL-1β expression at the protein level (Figs. 3B–I and S2J–L).

Fig. 3.

Role of GPR34 downstream signaling in microglia activation. A qPCR analysis to determine the indicated genes expression in PM pretreated for 30 min with 5 μM wortmannin, 10 μM FTS, 1 μM U73122, and 10 μM forskolin and then stimulated with LysoPS for 4 h (n = 4). B–E ELISA of IL-6 in supernatants from PM pretreated with various inhibitors for 30 min and then stimulated with LysoPS for 18 h (n = 4). F–I Immunoblot analysis of the pro-IL-1β in lysates from PM pretreated with various inhibitors for 30 min and then stimulated with LysoPS for 18 h. Immunoblot analysis of the pro-IL-1β in lysates (J) and ELISA of IL-6 ((K), n = 4) in supernatants of PM pretreated for 30 min with various inhibitors and then stimulated with myelin debris for 18 h. Data are representative of two independent experiments (A–K). The P values were determined by one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (B–E, K), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

Moreover, myelin debris-induced IL-6 and IL-1β expression also relied on PI3K-AKT and RAS-ERK pathway (Fig. 3J, K). Consistent with this, LysoPS induced expression of p-AKT and p-ERK was GPR34-dependent, and LysoPS-induced expression of p-IκB was not changed in Gpr34−/− PM (Fig. S2L). Additionally, NF-κB inhibitor (BAY11-7082) partially inhibited LysoPS-induced cytokine production (Fig. S2M), suggesting that GPR34 downstream signaling or GPR34-independent NF-kB signaling both contribute LysoPS-induced microglia activation. Thus, these results indicate that PI3K-AKT and RAS-ERK signaling pathways act downstream of LysoPS-GPR34 to promote microglia activation.

Myelin-derived LysoPS is essential for neuroinflammation during EAE and stroke

We next investigated the role of LysoPS production in neuroinflammation and pathology. MS is a demyelinating disease of the CNS leading to the progressive destruction of the myelin sheath surrounding axons. A widely used animal model for MS studies is experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), in which peripheral T helper 1 (Th1) and Th17 cells migrate into the CNS and promote oligodendrocyte damage and demyelination [30, 31]. Although previous reports suggest that EAE is mainly mediated by lymphocytes and monocyte-derived macrophage, especially Th17 cells, increasing evidence has shown that microglia-mediated inflammation is essential for the initiation and progression of EAE [32–35].

Abhd16a−/− mice showed reduced body weight compared wild type mice at different ages, which was consistent with a previous report [20], but had normal lymphocyte populations in spleen and thymus (Fig. S3A–C). To reduce the impact of the body weight, the 10-week-old Abhd16a−/− mice with body weight closer to wild type mice were chosen to induce EAE using a myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide (MOG35–55) (Fig. S3D). After induction, wild type mice developed severe clinical symptoms that were characterized by a gradual increase in the severity of paralysis (Fig. 4A–C), inflammatory cell infiltration into the CNS (Fig. 4D, E), and demyelination (Fig. S3E–H). However, the Abhd16a−/− mice were highly resistant to EAE induction (Figs. 4A–E and S3E–H). The resistance of the Abhd16a-/- mice was associated with reduced CNS-infiltrating T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) and monocytes (Figs. 4F and S3I). The expansion and activation of microglia (Ly6C−TMEM119+) were also suppressed in the CNS of Abhd16a−/− mice where MHCII expression was used as a marker of microglial activation (Figs. 4F, G, and S3J). Moreover, the accumulation of Th1 and Th17 cells was reduced in the CNS of Abhd16a−/− mice after EAE induction (Fig. 4H). The spinal cord of EAE-induced-Abhd16a−/− mice had much lower expression of various chemokines and inflammatory cytokines known to mediate immune cell recruitment and inflammation (Fig. S3K). These results indicate that ABHD16a-mediated LysoPS production is critical for EAE-induced neuroinflammation.

Fig. 4.

LysoPS production is essential for neuroinflammation during demyelination. Clinical scores (A), day of onset (B), and maximal scores (C) of Abhd16a+/+ (n = 13) or Abhd16a−/− (n = 12) mice after EAE induction. Representative H&E staining of spinal cord sections from Abhd16a+/+ and Abhd16a−/− mice on day 13 after EAE induction. Scale bars, 100 µm (D). Statistical evaluation of histology in terms of inflammatory cells infiltration (E), n = 5 mice per group. The numbers of the indicated subsets (F) and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of microglial MHCII expression (G) in the CNS (brain and spinal cord) of Abhd16a+/+ (n = 9) or Abhd16a−/− (n = 7) mice on day 13 after EAE induction. H CNS infiltrates were stimulated with PMA/ion plus monensin for 4 h, followed by surface staining for CD4+ T cells and intracellular staining for IL-17 and IFN-γ. The numbers of different cell populations were calculated. I Neurological scores after MCAO in Abhd16a+/+ (n = 14) or Abhd16a−/− mice (n = 13). Representative brains sections stained with 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) (J) and cerebral infarct volume was measured as a percentage of corrected infarct volume in Abhd16a+/+ (n = 9) or Abhd16a−/− (n = 8) mice at 48 h after MCAO (K). The percentages of monocytes (L) and MFI of microglial MHCII expression (M) in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere (IL) or contralateral hemisphere (CL) from Abhd16a+/+ (n = 10) or Abhd16a−/− (n = 9) mice at 48 h after MCAO. Clinical scores (N), day of onset (O), and maximal scores (P) of the Cnp-Cre (n = 9), Abhd16afl/fl (n = 10), or Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl (n = 8) mice after EAE induction. Q Neurological scores in Cnp-Cre (n = 10), Abhd16afl/fl (n = 9) or Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl (n = 7) mice after MCAO. Representative brain sections stained with TTC (R) and cerebral infarct volume was measured (S) in Cnp-Cre, Abhd16afl/fl, and Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice. n = 5 mice per group. Data pooled from three independent experiments (A–C, I, L–Q) or two independent experiments (E–H, K, S) are shown. The P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (A, I, N, Q), or determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (B, C, E–H, K–M, O, P). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

Ischemic stroke is a common cause of severe disability and death worldwide and is typically associated with acute sterile inflammation [36]. We then investigated the role of LysoPS in the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model, which is considered to be the closest to human ischemic stroke [37]. We found that MCAO induced severe demyelination (Fig. S3L). Moreover, Abhd16a−/− mice showed improved neurological scores at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after MCAO compared with wild type mice (Figs. 4I and S3M). Infarct volumes were significantly decreased in Abhd16a−/− mice at 48 h after MCAO (Fig. 4J, K). This phenotype was associated with impaired inflammation in ipsilateral ischemic hemispherecharacterized by reduced monocyte infiltration, microglia activation, and lower expression of chemokines and cytokines known to mediate immune cell recruitment and inflammation (Figs. 4L, M and S3N, O). These results indicate that ABHD16a-mediated LysoPS production promotes neuroinflammation during stroke.

Since oligodendrocytes are the myelin-producing cells of the CNS, we then investigated the role of oligodendrocyte-derived LysoPS in neuroinflammation. As ABHD16a was widely expressed on oligodendrocytes, neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and monocytes (Fig. S4A–D), we generated Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice in which Abhd16a expression was ablated in oligodendrocytes (Fig. S4E, F) [38]. Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice showed normal body weight and lymphocyte populations in spleen and thymus (Fig. S4G–I). Similar to Abhd16a−/− mice, Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice were resistant to EAE or MCAO induction compared with control mice (Fig. 4N-S). Cnp promoter has been reported to drive CRE expression in splenic immune populations, including B-cells, monocytes, and T cells [39]. We examined ABHD16a expression in these populations from Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice and found that its expression was reduced in B cells, but not in T cells or myeloid cells (Fig. S5A). Moreover, the percentages of Th1 or Th17 cells and the expression of MHC-II and CD80 on B cells in lymph nodes and spleen were not impaired in EAE-induced Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice (Fig. S5B-E), suggesting that the impaired B cell-expressing ABHD16a in Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice had no effects on EAE-induced periphery B or T cell activation. These results indicate that myelin-producing LysoPS is essential for neuroinflammation during EAE and stroke.

Deletion of GPP34 in microglia inhibits neuroinflammation and pathologies during EAE or stoke

We further investigated the role of GPR34 in neuroinflammation. The Gpr34−/− mice were resistant to EAE induction and showed less severe clinical symptoms, inflammatory cell infiltration into the CNS, and demyelination (Figs. 5A–C and S6A–D).

Fig. 5.

GPR34 is essential for neuroinflammation and pathologies during EAE or stoke. A Clinical scores of Gpr34+/+ (n = 15) and Gpr34−/− (n = 14) mice after EAE induction. Representative H&E staining of spinal cord sections from Gpr34+/+ and Gpr34−/− mice on day 13 after EAE induction. Scale bars, 100 µm (B). Statistical evaluation of histology in terms of inflammatory cells infiltration, n = 6 mice per group (C). Clinical EAE scores (D), day of onset (E), and maximal score (F) of Cx3cr1-Cre (n = 13), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 11), or Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl (n = 12). Clinical scores (G), day of onset (H), and maximal scores (I) of the Cx3cr1-CreER (n = 7), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 8) or Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl (n = 7) mice after EAE induction. The numbers of the indicated subsets (J) or different CD4+ T cell populations (K), MFI of microglia MHCII expression (L) in the CNS of Cx3cr1-Cre (n = 12), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 11) or Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl (n = 9) mice on day 13 after EAE induction. M Neurological scores in the Cx3cr1-Cre (n = 12), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 9) and Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice (n = 11) after MCAO. Representative brain sections stained with TTC (N) and cerebral infarct volume was measured (O) in Cx3cr1-Cre, Gpr34fl/fl, and Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice. n = 4 mice per group. P Neurological scores in the Cx3cr1-CreER (n = 9), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 8) or Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl (n = 7) mice after MCAO. Representative brain sections staining with TTC at 48 h after MCAO (Q) and cerebral infarct volume was measured (R) in Cx3cr1-CreER, Gpr34fl/fl, and Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl mice. n = 4 mice per group. The percentages of monocytes (S) or MFI of microglial MHCII expression (T) in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere (IL) or contralateral hemisphere (CL) from Cx3cr1-Cre (n = 12), Gpr34fl/fl (n = 9) and Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl (n = 11) mice at 48 h after MCAO. Data pooled from three independent experiments (A, D–F, J–M, S, T) or two independent experiments (G–I, P) are shown. The P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (A, D, G, M, and P), unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (C), or one-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (E, F, H, I, K, L, O, R–T). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

We then analyzed the expression of GPR34, and found that Gpr34 mRNA was highly expressed on microglia but not on astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or neurons (Fig. S6E), consistent with previous reports [24–26]. To further confirm this, we generated Gpr34Gfp/+ reporter mice (Fig. S6F). Using these reporter mice, we confirmed that GPR34 was highly expressed on microglia, but not on astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, or neurons of naïve mice (Fig. S6G). The same results were also observed after EAE or MCAO induction (Fig. S6H, I). Moreover, we found that Gpr34 deficiency had no effects on the ramification of microglia and lymphocyte populations in spleen and thymus (Fig. S6J–M).

To study the role of microglia-expressing GPR34 in EAE, we crossed Gpr34fl/fl mice with Cx3cr1-Cre mice to generate Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice in which Gpr34 expression was ablated in microglia (Fig. S7A, B). Similar to Gpr34−/− mice, Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice developed less severe clinical symptoms after EAE induction (Fig. 5D–F). As Cx3cr1 is expressed not only in microglia but also in peripheral myeloid cells and NK cells [40], we also generated microglia-specific Gpr34 deficient mice using Cx3cr1-CreER knock-in mice, which express Cre-ER fusion protein under the control of Cx3cr1 promoter, to cross with Gpr34fl/fl mice [41, 42]. qPCR analysis showed that Gpr34 expression was deleted in microglia but not in peripheral CX3CR1+ myeloid cells of Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl mice on day 30 after a five-day consecutive tamoxifen (TAM) injection (Fig. S7C, D), suggesting the specificity of Cre recombinase activity in microglia. Similar to Gpr34−/− or Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice, Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl mice were resistant to EAE (Fig. 5G-I). Moreover, we found that EAE-induced demyelination, CNS infiltration of inflammatory cells, microglia expansion and activation, or the expression of inflammatory cytokines or chemokines in spinal cord or isolated microglia were also reduced in Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice (Figs. 5J–L and S8A-F).

We also investigated the role of microglia-expressing GPR34 in MCAO model and found that mice with GPR34 deficiency in microglia showed improved neurological scores and significantly decreased infarct volumes after MCAO (Fig. 5M–R). Consistent with this, the reduced monocyte infiltration and microglia activation, and lower expression of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines in tissues or isolated microglia were also observed in the ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere of mice deficient in microglial Gpr34 (Figs. 5S, T and S7G, H). These results indicate that microglia-expressing GPR34 is critical for EAE or stroke-induced neuroinflammation and pathologies.

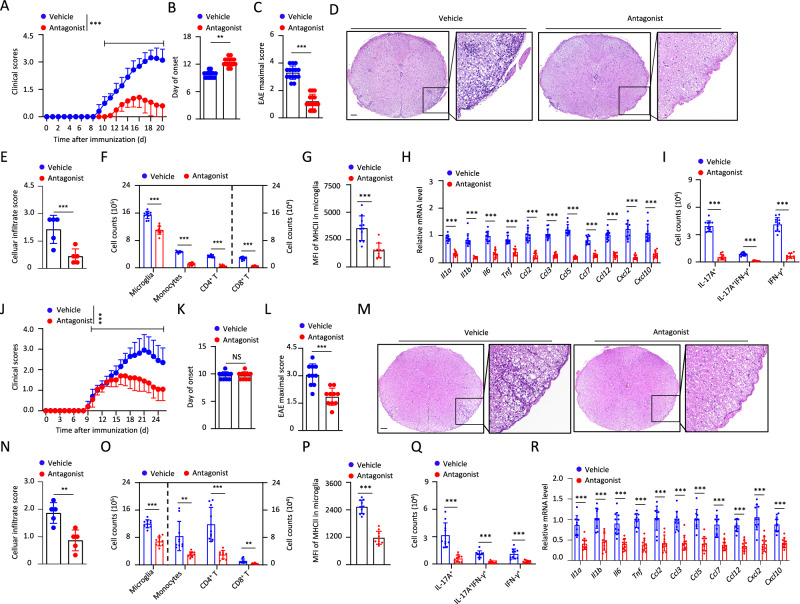

Therapeutic effects of GPR34 antagonist on EAE and stroke

Since LysoPS-GPR34 axis is essential for neuroinflammation and pathology in mice, we then investigated the human relevance of this pathway. We analyzed a published single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) database of human brain samples from patients with MS [43]. The results showed that GPR34 was highly expressed in human microglia of both MS patients and controls and its expression was upregulated in microglia from active MS lesions (Fig. S9A–C).

We then investigated the therapeutic possibility of targeting GPR34. GPR34 antagonist, which was administered on day 0 after EAE induction, significantly delayed the onset of EAE and inhibited the demyelination when compared with vehicle (Figs. 6A–E and S10A–E). This treatment inhibited EAE-induced infiltration of inflammatory cells, expansion and activation of microglia, and expression of various chemokines and inflammatory cytokines in the spinal cord (Fig. 6F–H). Moreover, we found that GPR34 antagonist treatment suppressed EAE-induced accumulation of Th1 and Th17 cells in the CNS, but had no effects on the percentages of Th1 or Th17 cells in lymph nodes and spleen (Figs. 6I and S10F–I), suggesting that this antagonist acts in the CNS. This was supported by the results that GPR34 antagonist could not inhibit MOG-induced IFN-γ or IL-17 production in CD4+ T cells in the presence of DCs (Fig. S10J, K). More importantly, we assessed the therapeutic benefits of GPR34 antagonist after symptom onset during EAE and found that GPR34 antagonist, that was administered on day 10 after EAE induction, still could reduce neuroinflammation and pathologies (Figs. 6J–R and S10L, M).

Fig. 6.

Pharmacologic inhibition of GPR34 has therapeutic effects on EAE. Clinical scores (A), day of onset (B), and maximal scores (C) of mice treated with vehicle (n = 15) or GPR34 antagonist (Antagonist, n = 15) after EAE induction. Representative H&E staining of spinal cord sections from mice treated with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist on day 13 after EAE induction. Scale bars, 100 µm (D). Statistical evaluation of histology in terms of inflammatory cells infiltration, n = 5 mice per group (E). The numbers of the indicated subsets (F) and MFI of microglial MHCII expression (G) in the CNS of mice treated with vehicle (n = 11) or GPR34 antagonist (n = 10). H qPCR analysis to determine the indicated genes expression in cervical spinal cords from mice treated with vehicle (n = 11) or GPR34 antagonist (n = 10) on day 13 after EAE induction. I The numbers of different CD4+ T cell populations in the CNS of mice treated with vehicle (n = 11) or GPR34 antagonist (n = 10). Clinical scores (J), day of onset (K), and maximal scores (L) of mice treated with vehicle (n = 15) or GPR34 antagonist (Antagonist, n = 15) at EAE symptom onset. Representative H&E staining of spinal cord sections from mice treated with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist on day 24 after EAE induction. Scale bars, 100 µm (M). Statistical evaluation of histology in terms of inflammatory cells infiltration, n = 5 mice per group (N). The numbers of the indicated subsets (O), MFI of microglial MHCII expression (P), and different CD4+ T cell populations (Q) on day 24 after EAE induction. n = 10 mice per group. R qPCR analysis to determine the indicated genes expression in cervical spinal cords from mice on day 24 after EAE induction. n = 10 mice per group. Data pooled from three independent experiments A–C) or two independent experiments (F–I, J–L, O–R) are shown. The P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (A and J) or determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (B, C, E–I, K, L, N–R). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

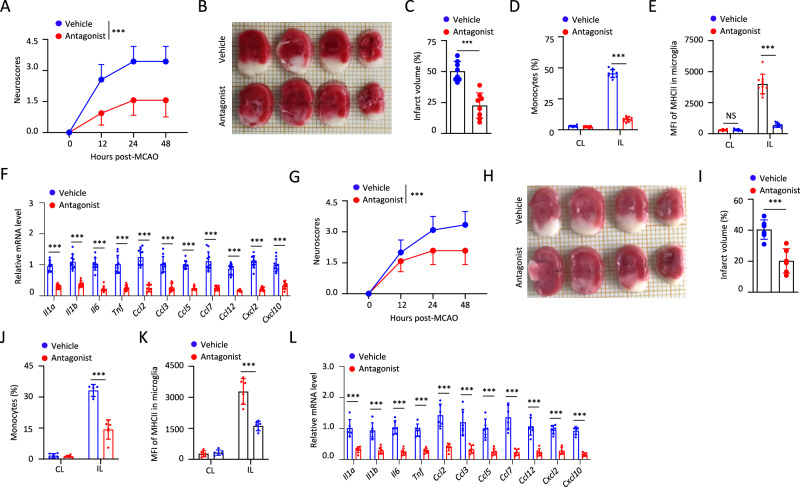

We further showed that GPR34 antagonist had not only preventive but also therapeutic effects on MCAO. Mice were treated with three doses of GPR34 antagonist or vehicle at −12, 0, and 12 h after MCAO, and the results showed that GPR34 antagonist treatment improved neurological scores and decreased infarct volumes significantly after MCAO (Fig. 7A–C). Consistently, this treatment resulted in not only reduced monocyte infiltration and microglia activation but also lower expression of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere during MCAO (Fig. 7D–F). Moreover, we found that the mice displayed reduced neuroinflammation and pathologies when they were administered with GPR34 antagonist at 3 and 12 h after reperfusion (Fig. 7G–L). These results suggest that GPR34 is a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of MS or stroke.

Fig. 7.

Pharmacologic inhibition of GPR34 has therapeutic effects on stroke. A Neurological scores of mice administered with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist at −12, 0, 12 h after MCAO. n = 16 mice per group. Representative brain sections stained with TTC (B) and cerebral infarct volume was measured (C) in mice treated with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist at 48 h after MCAO. n = 8 mice per group. The percentages of monocytes (D) or MFI of microglial MHCII expression (E) in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere (IL) or contralateral hemisphere (CL) from mice treated with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist. n = 10 mice per group. F The indicated genes expression in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere from mice at 48 h after MCAO was measured by qPCR. n = 10 mice per group. G Neurological scores of mice administered with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist at 3 and 12 h after reperfusion. n = 12 mice per group. Representative brain sections stained with TTC (H) and cerebral infarct volume was measured (I) in mice at 48 h after MCAO. n = 6 mice per group. The percentages of monocytes (J) or MFI of microglial MHCII expression (K) in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere (IL) or contralateral hemisphere (CL) from mice treated with vehicle or GPR34 antagonist. n = 6 mice per group. L The indicated genes expression in ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere from mice at 48 h after MCAO was measured by qPCR. n = 6 mice per group. Data pooled from three independent experiments (A) or two independent experiments (B–G) are shown. The P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test (A, G) or determined by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test (C–F, I–L). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, NS not significant

Discussion

Increasing evidence has shown that microglia activation and sterile neuroinflammation play a critical role in the initiation or secondary injury development of multiple neurological diseases [5, 6], but the mechanism of how microglia sense tissue damage and promote inflammation is poorly understood. The results presented here show that, during CNS injury and demyelination, GPR34 can be activated by myelin debris and its lipid component LysoPS and then promotes microglia to produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Moreover, LysoPS-GPR34 mediated microglia activation is essential for EAE or stroke-induced neuroinflammation and pathologies. Thus, our results reveal a new mechanism by which microglia sense CNS injury and demyelination to promote neuroinflammation.

The results presented here identified GPR34 as a new DAMP-sensing receptor for microglia to sense myelin debris and LysoPS. As a member of the GPCR family, GPR34 was first suggested as a receptor for LysoPS in mast cells and then this was confirmed in a reporter assay in HEK-293 T cells [22, 44]. However, a later study found that LysoPS-induced histamine release was not impaired in Gpr34-deficient mast cells [45], suggesting that LysoPS induce histamine release in mast cells via other receptors. In addition to mast cells, GPR34 is highly expressed on microglia [24–26]. A previous study reported that Gpr34 deficiency altered the number and morphology of microglia [45], but this was not confirmed in a later study [46]. Thus, although GPR34 has been identified as a signature gene for microglia, the role of GPR34 in microglia function is still unclear. Here, we showed that GPP34 had no effects on the morphology of microglia in steady state, but it sensed myelin debris and its lipid component LysoPS and then promoted microglia to produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines during brain damage. Consequently, GPR34 played an essential role in the neuroinflammation and progression of demyelination-associated diseases, such as MS or stroke.

Our results demonstrate that LysoPS generated by ABHD16A plays an important role in the progression of EAE and stroke. However, ABHD16A has been reported to be involved in metabolism of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) [47], although these results remain controversial [48]. Moreover, endocannabinoid signaling has been shown to regulate microglial activation, migration, and inflammatory responses [49, 50]. Thus, it is worthy to investigate whether ABHD16A can modulate microglial functions and neuroinflammatory through other mechanism besides LysoPS.

Our results revealed that GPR34 was essential for microglia to sense myelin debris and LysoPS and mediated the production of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, CCL7, and CCL12, but GPR34 was not involved in the production of myelin debris or LysoPS-induced TNF-α, CCL2, CCL3, CCL5 and other chemokines. Actually, we found that deficiency of GPR34 impaired LysoPS-induced PI3K-AKT and RAS-ERK activation, but not NF-κB activation. These results suggest the existence of other LysoPS receptor which can sense myelin debris or LysoPS to mediate NF-κB activation and the production of TNF-α or other chemokine production in microglia. GPR174 and P2RY10 are another two well-accepted LysoPS receptors [22, 23], but our results showed that their expression was extremely low in microglia and deficiency of them in microglia had no effects for myelin debris or LysoPS-induced inflammatory cytokine or chemokine expression. Another possible LysoPS receptor is G2A, which has been reported to promote macrophage to uptake dying neutrophils by sensing LysoPS [51]. In addition, TLR2 has been reported to be activated by schistosomal lysophosphatidylserine, but not by synthetic LysoPS [52]. So, the role of G2A, TLR2, or other unknown receptors in myelin debris or LysoPS-induced microglia activation, especially in NF-κB activation and the production of GPR34-independent cytokines or chemokines, should be further investigated.

Collectively, our results demonstrate LysoPS-GPR34 axis plays a critical role in microglia-mediated myelin debris sensing and the subsequent neuroinflammation. These results not only propose a mechanism of how microglia sense myelin debris, but also reveal GPR34 as a new DAMP-sensing receptor which can sense CNS injury and demyelination to promote innate immune responses and neuroinflammation. Considering demyelination and neuroinflammation are typically associated with many neurological diseases, GPR34 is highly expressed on human microglia [25], and GPCR-targeting drugs currently account for ~34% of all drugs in the USA [53], these results suggest that targeting GPR34 might provide a novel approach for treatment of these diseases, such as MS and stroke.

Methods

Mice

Wild type C57BL/6 J mice were from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Limited Liability Company. Cx3cr1-Cre (stock# 025524) and Cx3cr1-CreERT2-IRES-EYFP (Cx3cr1-CreER, stock# 021160) mice were from the Jackson laboratory. Cnp-Cre mice in C57BL/6 background have been described previously [38] and were kindly provided by Dr. Hui Fu (University of Science&Technology of China). Gpr34−/−, P2ry10−/−, Gpr174−/− and Gpr34fl/fl mice were generated as described previously [27]. Gpr34fl/fl mice were crossed with Cx3cr1-Cre mice to generate Cx3cr1-Cre.Gpr34fl/fl mice, and were crossed with Cx3cr1-CreER mice to generate Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl mice.

For generating Abhd16a−/− mice, we used the web tool CRISPOR (crispor.tefor.net) to identify guide RNA (gRNA) sequence for Abhd16a: GCAGGUCGCAGGGGCUCUGA [54]. pUC57-sgRNA (Addgene, 51132) was used as the template for PCR. The forward primer is GAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCAGGTCGCAGGGGCTCTGAGTTTTAGAGC. The reverse primer is AAAAAAGCACCGACTCGGTG. Then the PCR products were isolated by QIAGEN MinElute PCR Purification Kit (28004). After that, the sgRNAs were transcribed with the MEGA shortscript T7 Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher, AM1354) using the PCR products amplified according to the manufacturer. After transcription, the sgRNAs were purified by MEGA clear Transcription Clean-Up Kit (ThermoFisher, AM1908). The mixtures of gRNA (40 ng/μL) and Cas9 mRNA (40 ng/μL) (TriLink, L7606) were injected into the cytoplasm of pronuclear stage embryos. The founders were genotyped by PCR followed by DNA sequencing analysis. The positive founders were bred to the next generation (F1) and subsequently genotyped by PCR and DNA sequencing analysis. Genotyping primers were as follows: mAbhd16a-F: 5-CGGCTCTACAAGATCTACCG-3; mAbhd16a-R: 5-CCGTAAAGAGAGGCGGCGGC-3.

For generating Abhd16afl/fl mice [55], we designed 2 sgRNAs targeted the sites located in front of exon 8 of Abhd16a (Abhd16a-sg1) and behind exon 9 of Abhd16a (Abhd16a-sg2), respectively. We constructed left homology arm (LHA)-loxp-exon 8 to exon 9-loxp- right homology arm (RHA) into a pcDNA3.1 plasmid. The double strand DNA purified from the plasmid was used for homologous recombination (Takara R045A, Tsingke GE0101). Mixtures of gRNA (40 ng/μL), Cas9 mRNA (40 ng/μL) (TriLink, L7606), and dsDNA (100 ng/μL) were injected into the cytoplasm of pronuclear stage embryos. Abhd16a-sg1: GCUGUGACCCCAUCGCUAAG; Abhd16a-sg2: AGACCCCGCCUUGAAGUCGG. For sequence analysis of the loxp site, the following primer set was used for upstream loxp site: 5′-TGGGACATGACCCTTTGTAA-3′ and 5′-GGGGAACATGGGTTGGT-GAA-3′. The primer set was used for downstream loxp site: 5′-AGAGCTGTAGTCCTAGCTCT-3′ and 5′-TGAACTGCCATCAGGCTGCAT-3′. Abhd16afl/fl mice were crossed with Cnp-Cre mice to generate Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice.

For generating Gpr34gfp/+ mice, we used 2 sgRNAs to make a break near the start codon of Gpr34. SgRNA1 is in front of the start codon and sgRNA2 is behind the start codon. We constructed LHA-Gfp part (containing the sequence before the start codon of Gpr34 and Gfp sequence)-RHA into a pcDNA3.1 plasmid. The double strand DNA purified from the plasmid was used for homologous recombination. Mixtures of gRNA, Cas9 mRNA, and dsDNA were injected into the cytoplasm of pronuclear stage embryos. The Gfp sequence contained the stop codon, so the Gpr34gfp mice did not express GPR34. Gpr34gfp-sg1: GGACUAUCAAUGUCUUCUGC; Gpr34gfp-sg2: GCACCCU-GACCAACCUUUGU. For sequence analysis of the Gfp gene, the following primer set was used to detect the start sequence of Gfp gene: 5′-GGTCTGAAACGAAATCC-TTATCT-3′ and 5′-GCCGTTCTTCTGCTTGTCGG-3′. The primer set was used to detect the end of Gfp gene: 5′-GACCCGCGCCGAGGTGAAGT-3′ and 5′-CGGTGAATGCCCAGAAATAC-3′.

The littermates of mutant mice were used as the control in the present study. The mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility under a strict 12 h light cycle. The protocols of the animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Science and Technology of China.

Reagents

Primary antibodies against β-actin (Proteintech, 60008-1-Ig, 1:5,000), mouse IL-1β (R&D Systems, AF-401-NA, 1:1,000), Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Cell signaling, 9106L, 1:1000), Phospho-Akt (Cell signaling, 9271L, 1:1000), Phospho-p38 MAPK (Cell signaling, 9211S, 1:1000), Phospho-IκBα (Cell signaling, 9246S, 1:1000), mouse ABHD16A (Abcam, ab185549, 1:1000), PE-O4 (Miltenyi, 130-117-357, O4, 1:400), APC-GLAST (Miltenyi Biotec, ACSA-1, 130-098-803, 1:200) were used. FITC-B220 (553088, RA3-6B2, 1:400), FITC-CD3 (553062, 145-2C11, 1:400), PE-CD49a (562115, Ha31/8, 1:400), PE-IFNγ (554412, XMG1.2, 1:100), PerCP/Cy5.5-CD8α (551162, 53-6.7, 1:400), PE/Cy7-CD4 (552775, RM4-5, 1:400), APC/Cy7-CD45 (557659, 30-F11, 1:400), APC/Cy7-CD4 (552051, GK1.5, 1:400) were purchased from BD Pharmingen. FITC-CD4 (11-0041-85, GK1.5, 1:400), FITC-NK1.1 (11-5941-82, PK136, 1:400), FITC-CD11b (11-0112-82, M1/70, 1:400), Alexa Fluor 488-TMEM119 (53-6119-82, V3RT1GOsz, 1:200), PE-TMEM119 (12-6119-82, V3RT1GOsz, 1:400), PE/Cy7-B220 (25-0452-81, RA3-6B2, 1:400), APC-F4/80 (17-4801-82, BM8, 1:200), APC-CD8α (17-0081-82, 53-6.7, 1:400), APC-TCRβ (17-5961-82, H57-597, 1:400), APC-eFluor780-KLRG1 (47-5893-82, 2F1, 1:400) were purchased from ebioscience. The following antibodies were purchased from Biolegend: A488-MAP2 (801805, SMI52, 1:200), PE-CD4 (100408, GK1.5, 1:400), PerCP/Cy5.5-Ly6C (128012, HK1.4, 1:400), PerCP/Cy5.5-CD90.2 (105314, 30-H12, 1:400), PE/Cy7-CD31 (102524, MEC13.3, 1:400), PE/Cy7-CD19 (115520, 6D5, 1:400), APC-Ly6C (128016, HK1.4, 1:400), APC-IL-17A (506916, TC11-18H10.1, 1:100), Alexa Fluor 647-MAP2 (801807, SMI 52, 1:200), BV421-NK1.1 (108732, PK136, 1:400), BV510-CD45 (103137, 30-F11, 1:200) and BV510-CD8α (100752, 53-6.7, 1:200). LysoPS (18:1) (Avanti Polar Lipids, 858143) (Abbreviated as LysoPS), LysoPS (16:0) (Avanti Polar Lipids, 858142), LysoPS (18:0) (Avanti Polar Lipids, 858144), LysoPE (18:1) (Avanti Polar Lipids, 846725), ceramide (Topscience, T22644), phosphatidylethanolamine (18:1) (Topscience, T19080), phosphatidylserine (36:0) (Topscience, T21437), phosphatidylinositol (16:0, 18:0/1/2/3) (Sigma, 79403), wortmannin (Beyotime, S1952), Perifosine (Beyotime, SC0227), FR180204 (Beyotime, SD5978), FTS (Cayman, 162520-00-5), U73122 (TargetMol, T6243), PMA (Sigma, 79346), ionomycin (Sigma, 407952), monensin (Sigma, M5273), Luxol Fast Blue (Sigma, L0294, MCKF3315), DAPI (Sigma, D9542), DNase I (Sigma, DN25), pertussis toxin (List Biological, #181), Freund’s Incomplete Adjuvant (Difico, 263910, 8008624), mycobacterium tuberculosis (Difico, 231141, 9347411) and Tamoxifen (MCE, HY-13757A), OptiPrep (Sigma, D1556), Hibernate A (Thermo fisher, A1247501), L-Glutamine (Thermo fisher, 25030149), HA minus calcium (Thermo fisher, NC0176976), Type 2 collagenase (Worthington, LS004176), Papain (Sangon Biotech, A003118) and corn oil (Sigma, C8267) were used. MOG35-55 peptide was synthesized from Qiangyao Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). GPR34 antagonist (T8848, 907952-06-1) was synthesized from Shanghai Topscience Biological Technology Co., Ltd.

Preparation and fluorescent labeling of myelin debris

Myelin debris was isolated as described previously [11]. In order to avoid contamination, the following experiments were carried out in an ultra-clean bench. Mice were anaesthetized by isoflurane and perfused intracardially with 10 ml pre-cooled 1x PBS. CNS tissues (brain and spinal cord) were harvested and homogenized in 0.32 M sucrose dissolved in sterile water. Homogenate were layered on 0.85 M sucrose solution. After a 75,000 × g centrifugation for 30 min at 4 °C, the 0.32/0.85 M sucrose interface (crude myelin membranes) were diluted with ice-cold sterile water and pelleted at 75,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to concentrate the membranes. Myelin fractions were hypo-osmotically shocked by homogenization in 20 volumes of ice-cold sterile water, incubated for 30 min on ice, and rehomogenized. The shocked membranes were pelleted at 75,000 × g for 30 min, resuspended in 0.32 M sucrose solution, layered on 0.85 M sucrose solution, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 75,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The collected membranes were diluted with ice-cold sterile water and pelleted at 75,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to concentrate the membranes further. The 0.32/0.85 M sucrose interface were collected, then freeze-dried and weighed. Sequential ultracentrifugation was performed using a Beckman Coulter Optima L-XP SW 41 Ti 19U13398 Rotor. Endotoxin levels were monitored using a commercial kit (ToxinSensor Chromogenic LAL Endotoxin Assay Kit; GenScript, L00350, C51002001). Endotoxin levels were below 0.03 endotoxin units (EU) per milliliter. The concentration of myelin debris was 1.0 mg/ml for cell culture throughout this study.

Fluorescent labeling of myelin debris was performed using a non-cytotoxic dye, CFSE [56]. The dye enters the myelin debris by passive diffusion, where it covalently couples to free amine groups. Myelin debris (1 mg/ml) was labeled with 50 μM CFSE and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. The labeled myelin debris was washed with PBS containing 100 mM glycine at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, then washed with PBS twice at 14,000 rpm for 15 min each. The myelin debris pellets were collected and refilled to 100 µl with 1x PBS.

Myelin debris uptake assay

1 × 104 microglia were seeded in Ultra-low Attachment Multiple Well Plate (Corning, CLS3474-24EA) with serum-free medium. CFSE-labeled myelin debris was added to the microglia cells cultures at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. Non-ingested myelin debris was washed away from cell surface with EDTA for 30 s. Myelin debris uptake was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Myelin lipids extraction

1.0 mg myelin debris were resuspended in 800 μL of 2:1:1 CHCl3:MeOH: PBS [57]. The mixture was vortexed, then ultrasonicated for 10 min, and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min to separate the two phases. The organic phase (bottom) was removed, 20 μL of formic acid was added to acidify the aqueous homogenate (to enhance extraction of phospholipids), and CHCl3 was added to make up 800 μL volume. The mixture was vortexed and separated using centrifugation described above. Both the organic extracts were pooled, and dried under a stream of N2. The lipids were resolubilized with 100 μL methanol for cell stimulation, or 100 μL of 2:1 CHCl3: MeOH, and 10 μL were used for LC/MS analysis.

Cell culture

Cells were cultured at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries, 04-400-1 A) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells have been tested for mycoplasma contamination routinely using Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Beyotime, C0301S).

Cell stimulation

For the stimulation by myelin or lipids, microglia (2 × 105/mL) were seeded in 24-well plate with serum-free medium for 12 h, then treated for 4 h with 10 µM LysoPS (18:1) (Abbreviated as LysoPS), 10 µM LysoPS (16:0), 10 µM LysoPS (18:0), 10 µM LysoPE (18:1), 10 µM ceramide, 10 µM phosphatidylserine, 10 µM phosphatidylethanolamine, 10 µg/ml phosphatidylinositol (16:0,18:0/1/2/3), 1.0 mg/ml myelin debris. For myelin lipid stimulation, myelin lipids (from 250 µg myelin debris) dissolved in methanol were coated onto 24-well plate and incubated at room temperature for 4 h to allow methanol evaporation. Then microglia suspended in 250 µl medium were added to lipid-coated wells or solvent-treated control wells [13]. In some experiments, microglia were pretreated with PI3K inhibitor Wortmannin, AKT inhibitor Perifosine, ERK inhibitor FR180204, RAS inhibitor FTS, PLC inhibitor U73122, forskolin or GPR34 antagonist for 30 min prior to LysoPS or myelin debris stimulation. For ELISA or Immunoblot analysis, microglia were treated for 18 h.

Preparation and culture of microglia

After removing the meninges, the brains of newborn mice was dissociated using 0.25% trypsin, filtered with a 40 µm cell strainer, and then cultured in complete DMEM medium. After 2 weeks of cultivation (with medium changes at 24 h and then every 3 d), microglia were collected by gently shaking the culture for 1 min. The purity of microglia was >91% by flow cytometry.

Isolation of colon lamina propria cells (LPLs)

Mice were sacrificed and their colons were removed and placed in cold PBS. After removing any remaining fat tissues and Peyer’s patches, samples were flushed by HBSS buffer with 3% FCS, then cut open longitudinally, and cut into about 0.5 cm pieces. Samples were shaken at 37 °C for 40 min in HBSS containing 5 mM EDTA with 3% FBS for three times. Samples were then transferred into 50 ml tubes and digested in HBSS containing 10% FBS with 0.5 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma, C5138) by shaking at 37 °C for 20 min. Digested tissues were homogenized through 40 µm cell strainer and flushed through HBSS containing 3% FCS. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended to 40%/70% Percoll density gradient separation. LPLs at the interphase of the two Percoll solutions were collected for sorting as described previously [27].

Isolation of lymphocytes from thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes

Mice were sacrificed, then tissues were removed. Cells suspensions were prepared by grinding the organs through mesh filters. Erythrocytes in the splenocyte suspensions were hemolyzed by adding NH4Cl-Tris buffer for 5 min at room temperature followed by washing.

Co-culture of APCs and CD4 T+ cells

CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cell (APCs) from spleen of MOG-immunized wild-type mice were purified on day 8 by positive selection with MACS magnetic cell sorting. Briefly, splenocytes were incubated with anti-CD4 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-117-043) or anti-CD11b microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-049-601) for 30 min on ice, then washed and passed through a Type MS column following the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified CD4+ T cells and APCs were mixed at a ratio of 4:1 and pretreated with 5 μM GPR34 antagonist for 30 min and then stimulated with 50 μg/ml MOG35-55 for 48 h. 50 ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 1 μg/ml ionomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml monensin were added during the last 4 h of culture. Following incubation, the cells were harvest and washed for intracellular staining.

Isolation of CNS subsets in adult mice

For the preparation of microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, mice were perfused intracardially with pre-cooled 1x PBS, then brains and spinal cords were excised and homogenized with complete DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Dispersed cells were passed through a 100 μm nylon mesh and collected by centrifugation. Pellet was resuspended with 8 ml of 30% Percoll (GE Healthcare, 17-0891-09, 10260171). The cell suspensions were centrifuged at 2300 rpm for 25 min at 23 °C with low acceleration (acceleration 4) and low deceleration (deceleration 1). After centrifugation, erythrocytes were hemolyzed by adding NH4Cl-Tris buffer for 5 min at room temperature followed by washing. Cells were resuspended in complete DMEM medium for counting, staining, culture and/or sorting. For the preparation of neuron, OptiPrep was used to make fresh working stocks (7.4%/9.9%/12.4%/17.3%) with HABG (Hibernate A medium containing B27 and 0.5 mM Gln). Carefully pipette layer 2 (12.4%) onto the top of layer 1 (17.3%) with minimal disturbance to layer 1. Follow with layer 3 (9.9%) and layer 4 (7.4%) to complete formation of a density gradient. Adult neurons were isolated as described [58]. Briefly, mice were sacrificed, then spinal cords were removed and placed into cold HABG. Samples were cut into 0.1 cm pieces and transferred into 15 ml tubes, then digested in HA minus calcium with 1.0 mg/ml Type 2 collagenase, 0.5 mg/ml papain, and 0.25 mg/ml DNAase by shaking at 37 °C for 20 min. Digested tissues were homogenized and passed through a 100 μm nylon mesh and collected by centrifugation. Carefully apply the cell suspension to the top of the prepared OptiPrep density gradient and centrifuge the gradient at 1900 rpm for 20 min with low acceleration (acceleration 4) and low deceleration (deceleration 1). Aspirate the top supernatant containing cellular debris and collect fraction 2 and 3 into 15 ml tubes containing 5 ml HABG, then centrifuge the cell suspension for 5 min at 1100 rpm. Discard the supernatants and resuspend the cells with 3 ml Neurobasal A/B27.

Surface and intracellular staining

For surface staining, cells were first stained with DAPI on ice for 30 min to exclude dead cells. After wash, cells were stained on ice for another 30 min with the indicated Abs. For intracellular staining of IFN-γ and IL-17A, lymphocytes were cultured in 50 ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 1 μg/ml ionomycin and 2.5 μg/ml monensin for 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After staining with the Live/Dead fixable aqua dead cell stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and surface markers, cells were fixed by Fixation/Permeabilization buffer (eBioscience, 00-5523-00, 4318608) for 30 min and then stained with anti-mouse IFN-γ and IL-17A antibodies in the Permeabilization Buffer on ice for 1 h. Flow cytometry was performed on the BD FACSVerse (BD Bioscience) and analyzed by FlowJo v.10.0.7.

FACS sorting

Cells obtained from CNS tissues were stained with Ly6C, TMEM119, GLAST, O4, CD45, and DAPI on ice for 30 min. For neurons, cells were first stained with CD45 on ice for 30 min. Then cells were fixed by Fixation/Permeabilization buffer for 30 min and stained with MAP2 in the Permeabilization Buffer on ice for 1 h. Alive TMEM119+Ly6C− microglia, TMEM119−Ly6C+ monocytes, O4+CD45− oligodendrocytes, GLAST+CD45−TMEM119−Ly6C− astrocytes, and CD45−MAP2+ were sorted by FACSAria III (BD Bioscience). Cells isolated from CNS, spleen, or blood of Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl were stained with CX3CR1, DAPI, CD45 on ice for 30 min, then the CD45+CX3CR1+ were sorted and used to detect Gpr34 expression by qPCR. Cells isolated from spleen of Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl were stained with CD45, CD19, CD11b, CD4, CD8α, and DAPI on ice for 30 min, then alive CD45+CD4+ subset (CD4+), alive CD45+CD8α+ subset (CD8+), alive CD45+CD4−CD8α−CD19+ subset (CD19+) and alive CD45+CD4−CD8α−CD19−CD11b+ (CD11b+) subset were sorted and used to analyzed ABHD16A expression by western blooting. The purity of sorting cells was >95% by flow cytometry.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For detection of cytokines in supernatants of cell cultures, commercial ELISA kits were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ELISA kits for mouse TNF-α and IL-6 were purchased from R&D Systems.

Western blotting analysis

To investigate the expressions of relative proteins, western blot analysis was performed. Equal amounts of protein samples were loaded on gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) for electrophoresing and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk, washed with PBST buffer three times, and then followed by incubation overnight with anti-IL-1β antibody, anti-β-actin antibody, anti-phospho-IκB antibody, anti-phospho-Erk1/2 antibody, anti-phospho-p38 antibody and anti-phospho-Akt antibody at 4 °C. After the incubation and washing with PBST buffer three times, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h. Then, the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were employed to detect chemiluminescence signals.

Generation of conditional microglia-specific Gpr34 knockout

To obtain microglia-specific Gpr34-null mice, Cx3cr1-CreER mice were bred with Gpr34fl/fl mice for two generations to obtain Cx3cr1-CreER.Gpr34fl/fl mice. Tamoxifen (MCE, HY-13757A) was prepared at a concentration of 20 mg/ml in a mixture of ethanol and corn oil (1:9, v/v). All study mice including littermate control at postnatal day 30 were received tamoxifen at a dose of 75 mg/kg body weight/day for five consecutive days. A 30-day post-injection waiting period was used for clearance of Tam and for replenishing of Cxcr1+ monocytes prior to induction of animal models [41].

EAE induction and treatment

The EAE was induced as described [32]. All mice used here were 8-week-old males except Abhd16a−/− and Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice, which were 10-week-old males. Mice were s.c. injected in the flank with 300 μg myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) in 2.5 mg/ml complete Freund’s adjuvant. Pertussis toxin was given intraperitoneally at a dose of 6 μg/kg body weight on day 0 and day 2 after immunization. Mice were scored daily by a single observer and graded as follows: 0, no disease; 1, limp tail; 1.5, impaired gait; 2, tail paralysis and hind limb weakness; 2.5, one hind limb paralysis. 3, hind limb paralysis; 3.5, one forelimb paralysis; 4, hind and forelimb paralysis; 5, death of euthanasia for humane reasons. To prevent EAE, the age-matched male mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups, and GPR34 antagonist (10 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally to mice on day 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 of EAE induction. The GPR34 antagonist was dissolved in 10% DMSO + 40% PEG300 + 5% Tween-80 + 45% normal saline at a concentration of 2.5 mg/ml for use in the mouse models. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with GPR34-antagonist solution as-prepared above at a daily dose of 10 mg/kg or antagonist-free solution at the same volume based on body weight. Furthermore, the therapeutic effect of GPR34 antagonist was also evaluated by treatment from day 10 after EAE induction and every other day.

Transient focal ischemia model

All mice used here were 8-week-old males except Abhd16a−/− and Cnp-Cre.Abhd16afl/fl mice, which were 10-week-old males. All middle cerebral artery occlusion reperfusion (abbreviated MCAO) experiments were performed by an experimenter blinded to genotype or pharmacological treatment as described previously [59, 60]. Body temperature was maintained at 37 °C ± 1.0 using a heating pad. The mice were randomized and subjected to either sham surgery or 60 min of MCAO followed by reperfusion. Neuroscores were assessed as follows: 0, no deficit; 1, forelimb weakness and torso turning to the ipsilateral side when held by the tail; 2, circling to affected side; 3, unable to bear weight on affected side; 4, no spontaneous locomotor activity or barrel rolling. To prevent MCAO-induced brain injury, the age-matched male mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups and GPR34 (10 mg/kg) antagonist was administered intraperitoneally to mice at −12, 0, 12 h of MCAO. Control mice were treated with vehicle at the same time points. In addition, GPR34 antagonist administered at 3 and 12 h after reperfusion was used to evaluate the therapeutic effect.

Quantification of infarct volume

Measurement of infarct volume was carried out by an examiner blinded to genotype or treatment. Mice were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and perfused with 10 ml pre-cooling 1x PBS and then brains were removed immediately and cut into 4 × 2 mm coronal sections using tissue chopper. To quantify the infarct volume, slices were rapidly immersed into a 0.5% 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma-Aldrich, T8877) solution for 15 min at 37 °C, and carefully flipped every 5 min. The brain slices were scanned and the area of damaged unstained brain tissues was measured on the posterior surface of each section using ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). To correct for brain swelling, the infarct volume of each mouse was multiplied by the ratio of the volume of intact contralateral hemisphere to ischemic ipsilateral hemisphere at the same level.

Histological analysis

Thoracic spinal cords (T1–T3) dissected from mice transcardially were perfused with 4% formalin and then were postfixed overnight. Three sections from each tissue were obtained. Each section is 4 µm thickness and 100 µm apart. Sections were stained with H&E or Luxol Fast Blue (LFB) according to manufacturer’s instructions to analyze the inflammation and demyelination, respectively. The scoring method used has been previously described [61]. A 0–3 scale was used to assess the H&E-stained sections for inflammation: 0, no inflammatory cells; 1, a few scattered inflammatory cells; 2, organization of perivascular inflammatory infiltrates; and 3, extensive perivascular cuffing with extension into adjacent parenchyma or parenchymal infiltration without obvious cuffing. Demyelination in the LFB stained spinal cords was scored according to the following: 1, traces of subpial demyelination; 2, marked subpial and perivascular demyelination; 3, confluent perivascular or subpial demyelination; 4, massive perivascular and subpial demyelination involving one half of the spinal cord with presence of cellular infiltrates in the CNS parenchyma; and 5, extensive perivascular and subpial demyelination involving the whole cord section with presence of cellular infiltrates in the CNS parenchyma. Sections were imaged using TissueFAXS PLUS (TissueGnostics GmbH, Vienna, Austria, www.tissuegnostics.com). Histological score was evaluated in a double-blinded manner, and the average of three section scores for each tissue was used for statistics.

Transmission electron microscopy

TEM was performed as described [62]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with PBS. Spinal tissues were post-fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde plus 2% PFA in PBS at 4 °C for at least a week. Dissected tissues (1 mm in thickness) were postfixed in buffered OsO4, dehydrated in graded alcohol solutions, embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections (70 nm in thickness) were cut using a Leica Ultracut microtome (Leica, UC-7), stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate were examined and recorded with a JEOL 1400 electron microscope. Digital imaged were obtained using Morada G3. Percentage of axons with damaged myelin sheaths were determined using image analysis software (Image J). Percent damaged myelin was quantified as (number of axons with decompacted/loosened myelin/total number of myelinated axons) × 100. 3 to 4 high powered field (HPF) of each tissue were evaluated.

Immunofluorescent staining

Mice were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and transcardially perfused with cooled 1x PBS (pH 7.4), followed by ice-cold 4% PFA. Brains were cryo-protected with 30% sucrose after an overnight post-fixation in 4% PFA. Sections (30 μm in thickness) were selected and processed for immunofluorescent staining. The sections were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min, blocked in 10% normal goat serum for 2 h, and incubated with rabbit antibody against Iba-1 (Wako Chemicals, 019-19741, 1:400) in the blocking solution for overnight at 4 °C. After washing in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 3 × 10 min, the sections were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 546 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A10040, 1:400) in the blocking solution for 1 h. For negative controls, brain sections were stained with the secondary antibodies only. Sections were imaged using a Nikon A1H D25.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Lipidomic analysis was conducted on an VanquishTM Flex UPLC coupled to a Q Exactive hybrid quadrupole‐Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using a 100 × 2.1 mm hypersil GOLD 1.9 μm C18 column (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The temperature of column oven was set at 35 °C. The LC solvents were: buffer A: 95:5 = H2O: MeOH + 0.1% NH4OH, and buffer B: 60:35:5 = iPrOH: MeOH: H2O + 0.1% NH4OH. A typical run consisted of 33 min, with the following solvent run sequence post injection: 0.1 ml/min 0% buffer B for 5 min, 0.4 ml/min linear gradient of buffer B from 0–100% over 15 min, 0.5 ml/min of 100% buffer B for 8 min, and re-equilibration with 0% buffer B for 5 min. MS spectra were obtained in the negative ion mode, with high mass accuracy MS analysis and data‐dependent MS analysis. The MS spray voltages were 3.5 kV in the ESI-mode. The MS was operated at a resolving power of 70,000 in full‐scan mode (automatic gain control target: 1e5) and of 17,500 in the Top10 data‐dependent MS mode [stepped normalized collision energy: 35 in negative ion mode; automatic gain control target: 1e5 (neg)] with dynamic exclusion setting of 10 s. Lipid species were quantified by measuring areas under the curve. All MS raw data were acquired using the software Xcalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific, version 4.2). Lipid Search (Thermo Fisher Scientific, version 4.0) was used for identification and quantification.

RNA-sequencing and data analysis

RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) library preparation and sequencing for microglia samples were performed by the Illumina Hiseq 2500 sequencer (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). RNA-Seq fastq files were first processed by Trimmomatic (v0.36) to remove adapter and low-quality reads, and then aligned to the GRCm38 mouse genome assembly by HISAT2 (v2.1.0), followed by quantification with StringTie (v1.3.3b). The resultant gene count data were normalized by DESeq2 (v1.30.1), then used for downstream analysis. The differentially expressed genes between the experimental groups were identified by DESeq2. The Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) were used to perform pathway and process enrichment analysis using Metascope (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html), and an adjusted p-value of <0.05 was considered as a significant event.

Analysis of GPR34 expression in MS patients

We analyzed a published single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) database including 26992 single cells isolated from 9 controls and 4 chronic inactive cortex (Controls) and 21927 single cells isolated from 8 acute chronic-active MS patient’s cortex (MS active patients) [43]. The raw expression matrix and cell meta-annotations including the cell type, disease stage, and t-SNE position information were downloaded from website (https://ms.cells.ucsc.edu/). Then the unique molecular identifier (UMI) was normalized and log-transformed by Seurat (4.10), and the processed data was used for the following plot.

Gene knockdown in HMC3 cells with shRNA

Lentiviral pLKO.1 plasmids targeting GPR34 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The shRNA sequences were as follows: CCGGGCCTCTTAATTCTTTGAAGAACTCGAGTTCTTCAAAGAATTAAGAGGCTTTTT. The pLKO.1 scramble (Addgene, 1864) was used as a negative control. Gene knockdown in HMC3 cells (ATCC; CRL-3304™) was performed as described previously [63].

qPCR analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and complementary DNA was synthesized with an M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (TransGen) by a Step One Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The target genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene (Gapdh). The used primers are as follows:

Gapdh-forward, 5′-GGTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACG-3′

Gapdh-reverse, 5′-CTCGCTCCTGGAAGATGGTG-3′

Il1a-forward, 5′- AGCTCTCCGTACATTCCTGC-3′

Il1a-reverse, 5′- AGCTTTAAGGACGGGAGGGA-3′

Il1b-forward, 5′-TGCCACCTTTTGACAGTGATG-3′

Il1b-reverse, 5′-AAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC-3′

Il6-forward, 5′-GTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC-3′

Il6-reverse, 5′-GCACTAGGTTTGCCGAGTAGA-3′

Tnf-forward, 5′-CGATGGGTTGTACCTTGTC-3′

Tnf-reverse, 5′-CGGACTCCGCAAAGTCTAAG-3′

Ccl2-forward, 5′-GATGCAGTTAACGCCCCACT-3′

Ccl2-reverse, 5′-ACCCATTCCTTCTTGGGGTC-3′

Ccl3-forward, 5′-CAGCGAGTACCAGTCCCTTT-3′

Ccl3-reverse, 5′-GCAGTGGTGGAGACCTTCAT-3′

Ccl5-forward, 5′-TTGTCACTCGAAGGAACCGC-3′

Ccl5-reverse, 5′-AGAGCAAGCAATGACAGGGAA-3′

Ccl7-forward, 5′- TGCCTGAACAGAAACCAACCT-3′

Ccl7-reverse, 5′- GGCGTGACCATTTCACATTCC-3′

Ccl12-forward, 5′-AGACACTGGTTCCTGACTCC-3′

Ccl12-reverse, 5′-ACACTGGCTGCTTGTGATTCT-3′

Cxcl1-forward, 5′-CCTATCGCCAATGAGCTGCG-3′

Cxcl1-reverse, 5′-GAACCAAGGGAGCTTCAGGG-3′

Cxcl2-forward, 5′-ATCCAGAGCTTGAGTGTGACG-3′

Cxcl2-reverse, 5′- AGGTACGATCCAGGCTTCCC-3′

Cxcl3-forward, 5′-GGAAAGGAGGAAGCCCCTCA-3′

Cxcl3-reverse, 5′-ACAAGCAGGTAAAGACACATCCA-3′

Cxcl5-forward, 5′-TAAAAGGGGTGCAGTGGGTT-3′

Cxcl5-reverse, 5′-GAGCTGGAGGCTCATTGTGG-3′

Cxcl10-forward, 5′-TGAGAGACATCCCGAGCCAA-3′

Cxcl10-reverse, 5′-TCCCTATGGCCCTCATTCTCA-3′

Gpr34-forward, 5′-AGGAAAGCTTCAACTCAGTTCCT-3′

Gpr34-reverse, 5′-GAGCAAAGCCAGCTGTCAAC-3′

Abhd16a-forward, 5′-ATGTTTGTGGACCGACGG-3′

Abhd16a-reverse, 5′-CTTCTAGGGGTGTGGAGACA-3′

Pla1a -forward, 5′-TCCTAAGTCCCAAGTGGGTG-3′

Pla1a-reverse, 5′-AAAGTGGTCCCCACAACCAG-3′

Statistical analyses

All values are expressed as the mean ± s.d. of individual samples. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8. Statistical analyses were performed with the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons, or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test. P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Zhi Zhang and Dr. Hui Fu for providing mice and reagents. This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2020YFA0509101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81821001, 82130107, U20A20359), the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (YSBR-074).

Author contributions

BL, YZ, XW, ZH, MM, YX, and JY performed the experiments of this work; BL, XW, ZH, DW, WJ, and RZ designed the research. BL, WJ, and RZ wrote the manuscript. WJ and RZ supervised the project.

Data availability

Raw sequencing data will be made publicly available on the GEO database pending peer-reviewed publication. Additional data supporting the presented findings are available in the manuscript and upon request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. RZ is Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Cellular & Molecular Immunology, but he has not been involved in the peer review or the decision-making of the article. RZ, WJ, and BL are named as inventors on China National Intellectual Property Administration Application Serial CN202110355421.6 related to GPR34.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Bolong Lin, Yubo Zhou, Zonghui Huang.

Contributor Information

Xiaqiong Wang, Email: wxq1989@ustc.edu.cn.

Wei Jiang, Email: ustcjw@ustc.edu.cn.

Rongbin Zhou, Email: zrb1980@ustc.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-024-01204-3.

References

- 1.Janeway CA Jr., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen G, Shaw MH, Kim YG, Nunez G. NOD-like receptors: role in innate immunity and inflammatory disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:365–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong T, Liu L, Jiang W, Zhou R. DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;20:95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becher B, Spath S, Goverman J. Cytokine networks in neuroinflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colonna M, Butovsky O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:441–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou T, Zheng Y, Sun L, Badea SR, Jin Y, Liu Y, et al. Microvascular endothelial cells engulf myelin debris and promote macrophage recruitment and fibrosis after neural injury. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:421–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopper TJ, Gensel JC. Myelin as an inflammatory mediator: myelin interactions with complement, macrophages, and microglia in spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res. 2018;96:969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams K, Ulvestad E, Waage A, Antel JP, McLaurin J. Activation of adult human derived microglia by myelin phagocytosis in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 1994;38:433–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Cao K, Sun X, Chen Y, Duan Z, Sun L, et al. Macrophages in spinal cord injury: phenotypic and functional change from exposure to myelin debris. Glia. 2015;63:635–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun X, Wang X, Chen T, Li T, Cao K, Lu A, et al. Myelin activates FAK/Akt/NF-kappaB pathways and provokes CR3-dependent inflammatory response in murine system. PloS one. 2010;5:e9380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarner T, Diederichs F, Berger K, Denecke B, Gan L, van der Valk P, et al. Myelin debris regulates inflammatory responses in an experimental demyelination animal model and multiple sclerosis lesions. Glia. 2012;60:1468–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poliani PL, Wang Y, Fontana E, Robinette ML, Yamanishi Y, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. TREM2 sustains microglial expansion during aging and response to demyelination. J Clin Investig. 2015;125:2161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neumann H, Kotter MR, Franklin RJ. Debris clearance by microglia: an essential link between degeneration and regeneration. Brain. 2009;132:288–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doyle KP, Buckwalter MS. Immunological mechanisms in poststroke dementia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2020;33:30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q, Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:225–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohlen CJ, Friedman BA, Dejanovic B, Sheng M. Microglia in brain development, homeostasis, and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Genet. 2019;53:263–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, et al. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamat SS, Camara K, Parsons WH, Chen DH, Dix MM, Bird TD, et al. Immunomodulatory lysophosphatidylserines are regulated by ABHD16A and ABHD12 interplay. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki J, Nagai Y, Hosono H, Inoue K, Arai H. Structure and function of phosphatidylserine-specific phospholipase A1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugo T, Tachimoto H, Chikatsu T, Murakami Y, Kikukawa Y, Sato S, et al. Identification of a lysophosphatidylserine receptor on mast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:1078–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue A, Ishiguro J, Kitamura H, Arima N, Okutani M, Shuto A, et al. TGFalpha shedding assay: an accurate and versatile method for detecting GPCR activation. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1021–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang LC, Means TK, El Khoury J. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1896–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, et al. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedard A, Tremblay P, Chernomoretz A, Vallieres L. Identification of genes preferentially expressed by microglia and upregulated during cuprizone-induced inflammation. Glia. 2007;55:777–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]