Abstract

Obesity in adolescence is increasing in frequency and is associated with elevated proinflammatory cytokines and chronic pain in a sex-dependent manner. Dietary probiotics may mitigate these detrimental effects of obesity. Using a Long-Evans adolescent and adult rat model of overweight (high-fat diet (HFD) – 45% kcal from fat from weaning), we determined the effect of a single-strain dietary probiotic [Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v (Lp299v) from weaning] on the theoretically increased neuropathic injury-induced pain phenotype and inflammatory cytokines. We found that although HFD increased fat mass, it did not markedly affect pain phenotype, particularly in adolescence, but there were subtle differences in pain in adult male versus female rats. The combination of HFD and Lp299v augmented the increase in leptin in adolescent females. There were many noninteracting main effects of age, diet, and probiotic on an array of cytokines and adipokines with adults being higher than adolescents, HFD higher than the control diet, and a decrease with probiotic compared with placebo. Of particular interest were the probiotic-induced increases in IL12p70 in female adolescents on an HFD. We conclude that a more striking pain phenotype could require a higher and longer duration caloric diet or a different etiology of pain. A major strength of our study was that a single-strain probiotic had a wide range of inhibiting effects on most proinflammatory cytokines. The positive effect of the probiotic on leptin in female adolescent rats is intriguing and worthy of exploration.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A single-strain probiotic (Lp299v) had a wide range of inhibiting effects on most proinflammatory cytokines (especially IL12p70) measured in this high-fat diet rat model of mild obesity. The positive effect of probiotic on leptin in female adolescent rats is intriguing and worthy of exploration.

Keywords: age, diet, metabolism, neuropathic pain, probiotic

INTRODUCTION

Adolescent chronic pain is a growing problem with unknown etiology and limited effective treatment options (1) and is more prevalent in females (2). In 80% of cases, chronic pain continues into adulthood, affecting the quality of life and placing a burden on the healthcare system (3). Understanding the mechanisms underlying chronic pain is fundamental to its prevention and treatment. The development of chronic pain is highly variable and has been attributed to biological, psychosocial, environmental, and genetic factors in humans, which are thought to be largely absent or controlled in animal studies (4–6).

Obesity starting in the young is a major concern associated with significant health issues, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (7, 8). Although obesity is also associated with chronic pain in both adults and children, such as musculoskeletal pain, migraines, and osteoarthritis (9–15), the mechanisms underlying this association are unknown. Consumption of unhealthy fats and sugars contributing to obesity has many consequences, including reduced synaptic plasticity and dysfunction of brain regions in central pain pathways that could contribute to chronic pain (16, 17). Obesity-related low back pain may not only be due to increased lumbar spine load but also due to inflammatory adipokines and cytokines released from white fat (18, 19). Obesity-induced inflammation could influence pain through immune system activation (19, 20). Leptin, a metabolic signaling hormone released by adipocytes, is proinflammatory and can enhance pain behaviors (21, 22) as are cytokines that are elevated in obesity (20, 22).

There is compelling evidence that inflammation in the peripheral and central nervous system plays a role in the onset and maintenance of chronic neuropathic pain (23). Proinflammatory mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, and adipokines, can stimulate or sensitize nociceptors and evoke long-term neuroplasticity (23–27). Left unresolved, these potentially negative adaptations could promote chronic neuropathic pain and become refractory to treatment, which could explain the lack of effective pain relief therapies.

Dysregulation of the microbiota-gut-brain axis is linked to visceral, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain, and treatments targeted at this system have been associated with pain reduction (28). The use of probiotics is one such example. Although the data are mixed, multistrain probiotic use has been associated with therapeutic benefits, such as reduced pain intensity, number of days with pain in the past month, and pain-related disability in patients with migraine (29, 30). In contrast, one study did not find that a multistrain probiotic reduced pain intensity or pain days over placebo and did not decrease systemic inflammation (30). However, participants in this study had relatively low baseline levels of inflammation, which may have reduced the opportunity to demonstrate an effect. We have shown that chronic pain and obesity have synergistic effects in human subjects, which are associated with augmented levels of systemic inflammation (31, 32). Given that inflammation may underlie the relationship between chronic pain and obesity, it is plausible that targeting inflammation with probiotics may reduce pain. The difficulty with current studies is the use of multistrain probiotics, which precludes precise identification of mechanisms. However, 6 wk of a single-strain probiotic [Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v (Lp299v)] does result in “strong” anti-inflammatory effects in men with stable coronary vascular disease (33).

This study assessed neuropathic pain behaviors, diet, and a single-strain probiotic on body composition, and an array of serum cytokines and adipokines in adolescent (∼9 wk old) and adult (∼14 wk old) male and female rats. Dietary interventions were started at weaning (∼22 days) and continued throughout the study and included either a control or high-fat diet (HFD) and a placebo or Lp299v (probiotic). We hypothesized that HFD, by increasing body fat content, would alter pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines in association with a change in neuropathic pain. We also hypothesized that oral intake of a specific probiotic (Lp299v) would mitigate these effects.

METHODS

The protocols for the study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at the Zablocki Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Medical College of Wisconsin. Sixty male and 64 female offspring from 14 pregnant Long-Evans dams obtained from Envigo at 14 days gestation (Indianapolis, IN) were weaned at 3 wk of age (28–66 g males, 37–63 g females; RRID:RGD_2308852 (https://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/report/strain/main.html?id=2308852). Long-Evans rats were selected for study as this strain has been shown to develop obesity on an HFD (34, 35). We also chose the Long-Evans rat as the basis for future studies with inbred and sequenced Long-Evans substrains that are available at our institution (https://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/report/strain/main.html?id=39456107).

Rats were maintained and used according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and in compliance with federal, state, and local laws and the ARRIVE guidelines (36). Animals from a single family were housed 2–3 per cage, separated by sex, in a room on a reverse 12-h light/12-h dark cycle from 6 AM/6 PM, maintained at 22 ± 1°C at 35–65% humidity. Animals had free access to food and water, and bedding was Beta Chip (Warrensburg NY). Rats were weighed weekly from the day of weaning.

At weaning, pups were randomly assigned to a diet of regular (4.5%; Purina laboratory rodent diet 5001; Waldschmidt, Milwaukee WI; www.labdiet.com/product/detail/5001-laboratory-rodent -diet) or high-fat content rat chow (45 kcal% from saturated fats; D12451, Research Diets, Inc., New Brunswick. NJ; www.researchdiets.com/formulas/d12451) with either single-strain probiotic (Lp299v; 10 bn CFU/150 mL) or placebo (both from Probi USA, Inc., Redmond WA) in the drinking water (n = 6–9 rats per group; Table 1) for 6 wk (i.e., at 9 wk of age–late adolescence) or 11 wk (i.e., at 14 wk of age-adulthood) (37, 38). Because 2–3 rats were housed per cage, we could not calculate the individual rat’s daily consumption of Lp299v or placebo. Based on the average daily water intake and a previous study, each rat consumed ∼1 billion CFU of Lp299v per 100 g body weight per day (39). Lp299v in the drinking water was made fresh every 3 days. Water bottles were refilled and shaken daily, and intake was qualitatively monitored to ensure adequate and appropriate intake of Lp299v or placebo.

Table 1.

ANOVA test results (P values) for body composition analysis

| Total Body, g | Fat, g | Fat, % | Fat-Free Mass (FFM), g | FFM % | Total Body Water, g | Hydration, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Adol vs. Adult) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Diet (Ctl vs. HFD) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.101 | < 0.001 | 0.101 | < 0.001 |

| Probiotic (Y/N) | 0.502 | 0.158906 | 0.19 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.839 | 0.191 |

| Sex (M/F) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.164 | < 0.001 | 0.164 | < 0.001 | 0.165 |

Data are found in Supplemental File S1. Data were analyzed by four-way ANOVA.

Spared Nerve Injury

At 6 wk of age, spared nerve injury (SNI) was performed on all rats to induce neuropathic pain as described previously (40, 41). Under full isoflurane anesthesia (5% induction, 2% maintenance), an incision was made through the skin and the biceps femoris muscle on the lateral surface of the right thigh to expose the sciatic nerve and its three terminal branches (tibial, common peroneal, and sural nerves). The tibial and common peroneal nerves were ligated with 6.0 silk suture and transected, while care was taken to avoid trauma to the sural nerve, which remained intact. All injuries were performed by the same experienced surgeon who has performed this surgery regularly (42). The muscle layers were closed with 5-0 absorbable polyglycolic suture, and the skin layer was closed with staples that were removed after 7 days. Carprofen (5 mg/kg sc) was administered at the start of surgery and 24 h postoperatively.

Behavioral Evaluation

Different aspects of pain behavior were evaluated by cold plantar assay, plantar test for thermal stimulation, and noxious mechanical stimulation by pin. Sensory tests were performed before SNI at 6 wk (baseline), at 9 wk (adolescent), and at 14 wk of age (adult). Before the testing, the rats were acclimated to their testing chamber for 15 min to allow the animals to cease exploratory activity. The mechanical stimulation was performed before either cold plantar or Hargreaves tests, and a maximum of two sensory tests were performed in 1 day, separated by at least 2 h. Testing was applied to each hind paw, ipsilateral and contralateral to injury. The apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with soap and water between use.

Cold plantar assay.

Each rat was placed in a plexiglass enclosure (20 × 10 × 15 cm) on a Hargreaves apparatus (Ugo-Basile, Inc., Comerio, Italy). To assess cold allodynia (increased pain from a normally innocuous stimulus), dry ice was ground into a powder, loaded, and compressed into a 60-mL syringe modified with a 30-mm diameter circle cut at the tip end. The dry ice pellet extended 5 mm from the syringe and was gently but firmly pressed to the glass surface targeting the center of the hind paw. The rat was observed for exaggerated lifting, licking, and shaking of the paw, indicative of pain behavior in the rat and not unrelated ambulation. Latency to paw withdrawal was monitored with a cut-off time of 20 s after which the ice pellet was removed to avoid tissue damage. Five applications to each hind paw at 2-min intervals were averaged for each time point for subsequent analysis.

Plantar test for thermal stimulation performed on the Hargreaves apparatus.

To assess thermal sensitivity, a radiant heat stimulus of 48°C was generated by a controlled infrared, focused light source applied through the glass surface, targeting the center of the hind paw. The rat was observed at all times to ensure that paw withdrawal from the light source was a response and not unrelated ambulation. A sensor monitored paw withdrawal latency with a cut-off time was set to 20 s. Five applications to each hind paw at 2-min intervals were averaged for each time point for subsequent analysis.

Noxious mechanical stimulation by pin.

To assess mechanical hyperalgesia (increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain), animals were placed individually in clear plastic enclosures on an elevated one-fourth-inch wire grid. The point of a 22-gauge spinal anesthesia needle was applied to the lateral part of the glabrous plantar surface of the paw with sufficient needle force to indent, but not penetrate, the skin. The behaviors induced by this noxious stimulus were of two types: either a brisk, simple withdrawal with immediate return of the foot to the wire floor, which is typical of normal animals, or a hyperalgesia-type response that consisted of sustained elevation of the paw with shaking, licking, and grooming (41, 43). Although there are numerous measures of an animal’s pain experience, this test was chosen because hyperalgesia induced by a pin touch is a common finding in clinical pain patients, especially those with peripheral neuropathic pain (44, 45). In addition, we have confirmed that positive responses to this test specifically correlate with conditioned place avoidance in plantar skin testing of nerve-injured rats, thus identifying an aversive experience, whereas other tests, such as simple response to calibrated monofilaments to determine withdrawal threshold (von Frey test), are not aversive even at the force that causes withdrawal (46). The frequency of hyperalgesia responses during needle testing was used as the most meaningful measure of pain hypersensitivity. One individual assessed the frequency of hyperalgesia responses for each of five applications to the hind paw. Mechanical stimuli were separated by at least 10 s and repeated after 5 min, for a total of 10 touches to each paw. For each time point, the total number of hyperalgesia responses (a maximum of 10) was converted to a percentage to provide the hyperalgesia response rate for analysis. In agreement with our previous findings (40), there was no exaggerated response on stimulation of the paw contralateral to injury, so only observations on the paw ipsilateral to injury are reported here.

End of study analyses and sample collection.

Body composition was assessed at 9 wk of age for adolescent rats and 14 wk for adult rats that had been fasted for 18 h, using time-domain nuclear magnetic resonance (TD-NMR; LF110, Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA) as described and validated previously (47). After completion of NMR, rats were euthanized by decapitation under full isoflurane anesthesia, and trunk (arterial and mixed venous) blood was collected and processed into serum samples frozen for subsequent analysis.

Cytokine Assays

All assays were performed on coded samples blinded to the experimental condition of the individual rats from which they were derived. A serum cytokine array was performed by Eve Technologies [Rat Cytokine/Chemokine 27-Plex Discovery Assay Array (RD27), Calgary, AB Canada] in duplicate after a twofold dilution of the serum in phosphate-buffered saline. This bead-based array uses validated capture antibodies and a dual-laser/flow cytometry system. It measures Eotaxin, EGF, Fractalkine, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-18, IP-10, GRO/KC, TNFα, G-CSF, GM-CS, MCP-1, Leptin, LIX, MIP-1α, MIP-2, RANTES, and VEGF-A. C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured in duplicate using an ELISA [Invitrogen (ERCRP), Thermo Fisher, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA] (48). We extensively validated this assay against several other methods and by assessing a spiking recovery with pure recombinant rat CRP [Assay Genie (RPPB3264); Dublin 2, Ireland]. Rat adiponectin was measured in duplicate by ELISA (Crystal Chem no. 80570, Elk Grove Village, IL) as we have published previously (49).

Data and Statistical Analysis

The data, power analyses, and statistical analysis comply with current recommendations on experimental design and analysis (50). All of the graphs in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were created using Sigmaplot 15.0 (RRID:SCR_003210; https://scicrunch.org/resolver/SCR_003210; Systat Software, Inc., Inpixon, Palo Alto, CA). For the longitudinal body weight data in Fig. 1, a two-way ANOVA repeated on time was used to compare within males and within females. Multiple pairwise comparisons were performed with the Holm–Sidak method (Sigmaplot). In Figs. 2, 4, and 5, a one-way ANOVA test was used to compare the effect of probiotic (Lp299v and placebo) on NMR fat%, leptin, and IL12 levels among four different subgroups separately: HFD-adolescent male, HFD-adult male, HFD-adolescent female, and HFD-adult female. For Leptin and IL12, pairwise comparison was used to test if Lp299v was different from placebo within diet among four subgroups: adolescent male, adult-male, adolescent female, and adult female. As one outlier that was two SD away from the mean in adult, male, HFD, Lp299v group, it was removed from NMR data. For Fig. 3 (pain data), pairwise comparison test was performed for cold and heat (pain) data for both adult male and female at week 14 between each level of diet (HFD vs. Control) and probiotic (Lp299v vs. placebo). To create Tables 1 and 2, four-way ANOVA tests were conducted for all body composition (NMR) and all rat serum cytokine data. Age (adult vs. adolescent), diet (HFD vs. control), probiotic (Lp299v vs. Placebo), and sex (female vs. male) were included as independent variables in all models. Tukey HSD test was used to confirm the main effect of ANOVA test results. Statistical significance level was set to be P value < 0.05. Statistical software R version 4.2.1 was used to analyze the data in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5). In specific instances indicated in the appropriate figure legends, if a main factor was not significant, the groups within that factor were combined or trimmed, and reanalyzed by an ANOVA with one fewer factor (Sigmaplot).

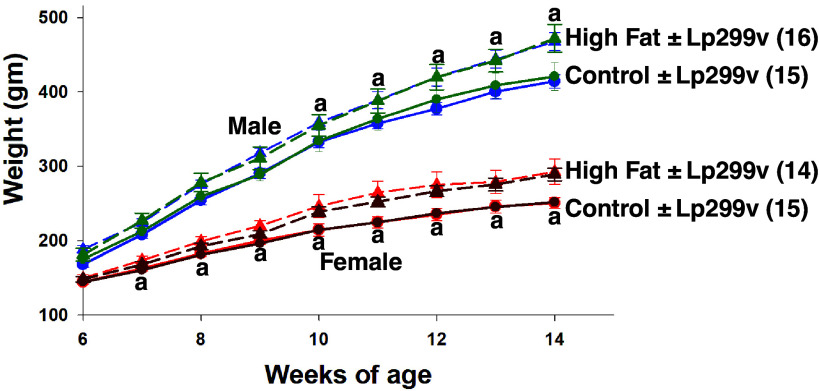

Figure 1.

Body weight over time in rats (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA) studied as adults (to facilitate repeated measures analysis over time). ±Probiotic (Lp299v vs. placebo) data were not different so data within each group were combined for statistical analyses. n values are shown in parentheses. All time points greater than previous time point within the group. “a” indicates high fat different from control: male P values: 10 wk 0.032; 11 wk 0.012; 12 wk 0.002; 13–14 wk <0.001; P values for ANOVA: diet P = 0.048; time P < 0.001; interaction P < 0.001. Female P values: 7 wk 0.023; 8–9 wk 0.002; 10 wk 0.001; 11–14 wk <0.001; P values for ANOVA: diet P = 0.004; time P < 0.001; interaction P < 0.001.

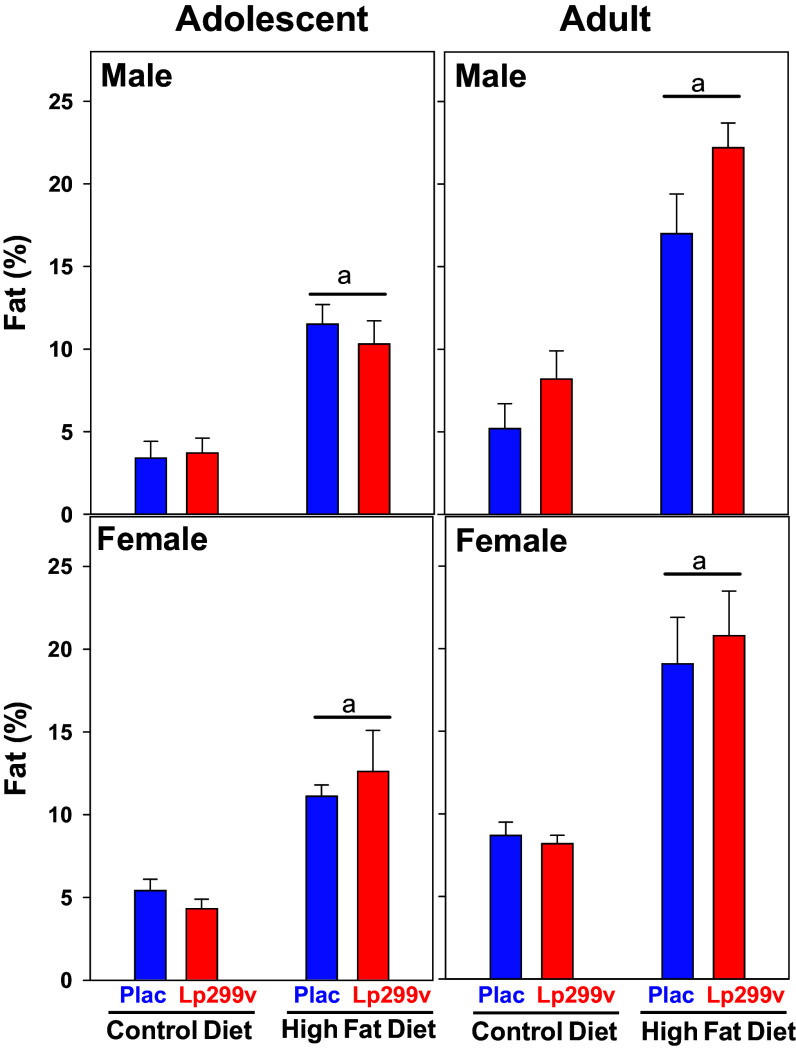

Figure 2.

Percent total body fat measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). There was no effect of Lp299v per se. Therefore, the probiotic (Lp299v) and placebo (Plac) groups were combined for statistical analysis. Underlined “a” indicates high-fat diet (HFD) (Plac and Lp299v data combined) different from control diet (P < 0.001). ANOVA repeated on age P values: age < 0.001, diet < 0.001, probiotic = 0.19, sex = 0.164. NMR data contained 124 observations, as an outlier was found in an adult, male, HFD, Lp299v group rat. Therefore, the sample sizes are the following: male adolescent and adult Ctl diet (13 and 15) and HFD (16 and 15); female adolescent and adult Ctl (17 and 14) and HFD (18 and 15).

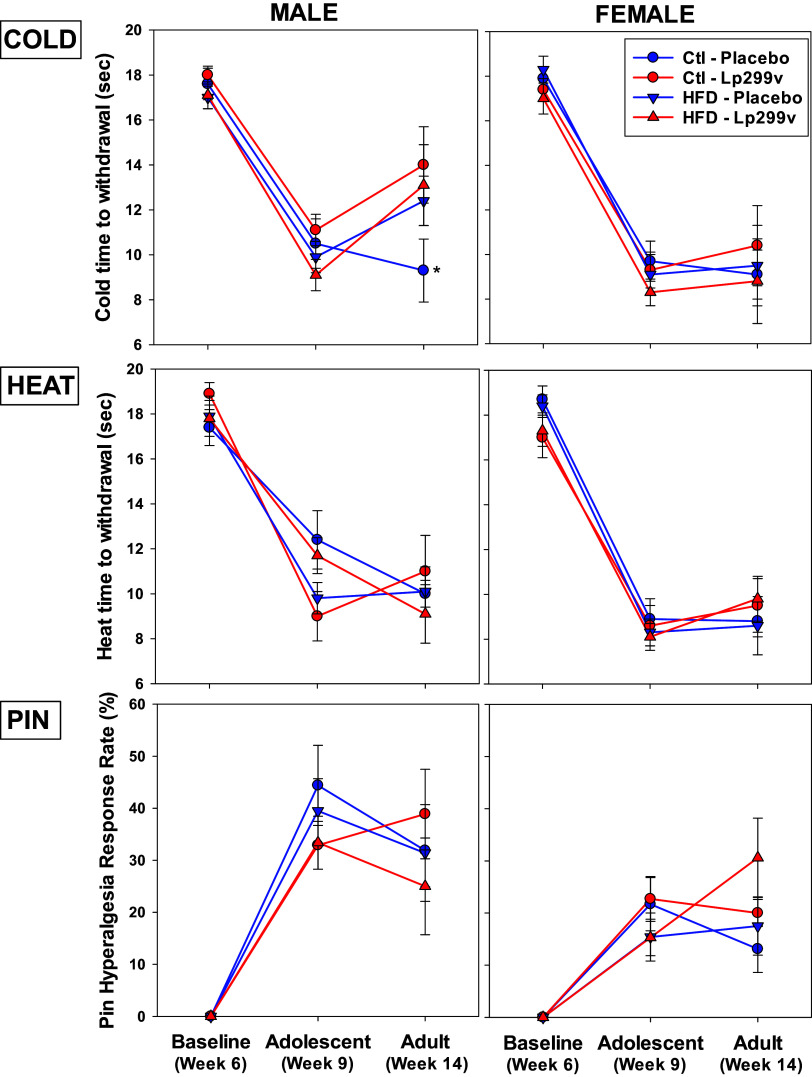

Figure 3.

Effects of diet on sensory assessments. Spared nerve injury performed after baseline testing in week 6 induced cold allodynia (COLD), thermal hypersensitivity (HEAT), and mechanical hyperalgesia (PIN) in adolescent (9-wk-old) male and female rats that was maintained in adult (14-wk-old) rats. Regardless of sex, neither high-fat diet (HFD) nor probiotic (Lp299c) influenced COLD, HEAT, or PIN in adolescent or adult rats, except for adult male rats at week 14 in which Lp299v enhanced cold allodynia (*P = 0.045). The ANOVA P values < 0.05 for COLD: sex = 0.001, week = 0.010, probiotic × diet = 0.035, and probiotic × week × diet = 0.018. For heat: sex and week were each < 0.001. For PIN: sex < 0.001 and sex × diet 0.033. Each group’s n values are as follows: low-fat (control diet)/placebo: adolescent male (6) and female (8); adult male (8) and female (8). Low-fat (control diet)/Lp299v: adolescent male (8) and female (9). Adult male (7) and female (7). High-fat diet/placebo: adolescent male (8) and female (9). Adult male (8) and female (7). High-fat diet/Lp299v: adolescent male (7) and female (9). Adult male (8) and female (7).

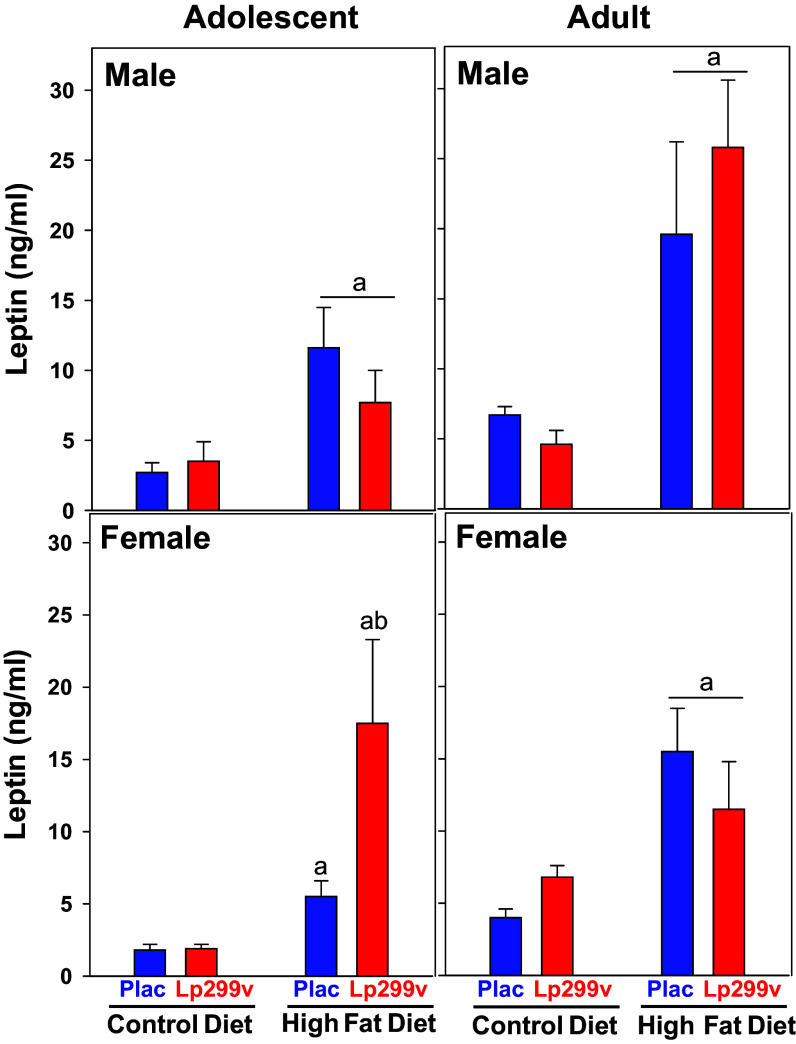

Figure 4.

Effect of diet on serum leptin concentration. There was no effect of probiotic (Lp299v) versus Placebo (Plac) within males so the data were combined for statistical analysis (underlined “a”). ANOVA P values <0.05 are listed below. n values: male adolescent: Ctl diet (13) vs. HFD (16): aP = 0.002, ANOVA P for diet = 0.029; male adult: Ctl diet (15) vs. HFD (16), aP < 0.001. ANOVA P for Diet < 0.001; female adolescent: control diet placebo (8) and Lp299v (9). A. HFD > control diet (P = 0.004). Within HFD Plac (9) vs. Lp299v (9) bP = 0.009. ANOVA P for diet × probi = 0.005; female adult: There was no effect of Lp299v, so data were combined. N values: Ctl diet (13) vs. HFD (13), underlined a P = 0.002. ANOVA P for diet = 0.007. Overall ANOVA P values: age P = 0.014 and diet P < 0.001.

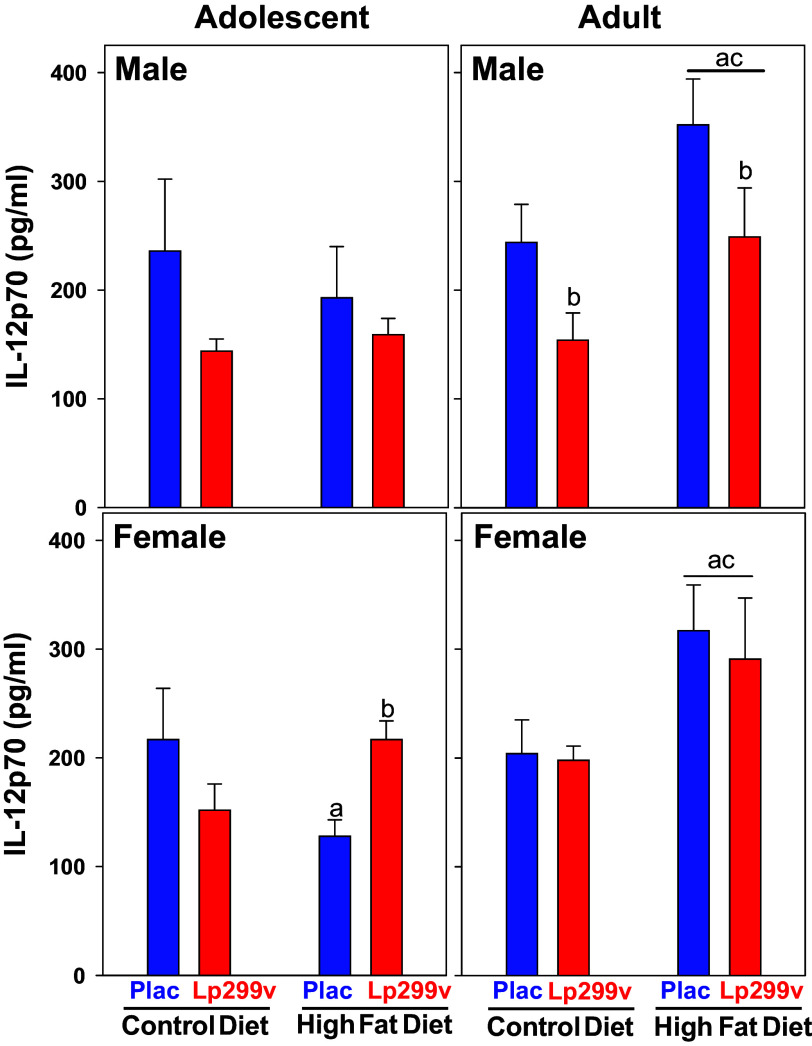

Figure 5.

Effect of diet on serum IL12 concentration. There was no effect of probiotic (Lp299v) or high-fat diet (HFD) within adolescent males. HFD increased IL12 in adult males with Lp299v and placebo combined (underlined a P = 0.025). Overall, regardless of diet, Lp299v decreased IL12 in adult males (P = 0.019). In female adolescents, HFD decreased IL12 in placebo group (aP = 0.04) and increased IL12 in Lp299v group (bP = 0.04). In female adults, there was no effect of Lp299v so the groups were combined (underlined statistical letters). HFD increased IL12 in adults (Lp299v and placebo combined. underlined a P = 0.004). Underlined “c” indicates that IL12 within HFD was greater in adults compared with adolescents (P < 0.05). Overall ANOVA P values are age < 0.001, diet = 0.021, and probiotic = 0.056. n values as in Fig. 4 legend.

Table 2.

Rat serum cytokine main ANOVA effects and changes with (P < 0.10) comparisons

| Cytokine | Age: Adult vs. Adolesc |

Diet: HFD vs. Ctl |

Probiotic: Lp299 vs. Plac |

Sex: F vs. M |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGF | ↑ 0.020 | |||

| Eotaxin | ↓ 0.051 | |||

| Fractalkine | ↑ 0.067 | ↓ 0.053 | ||

| G-CSF | ↓ 0.007 | ↓ 0.008 | ||

| IFNγ | ↓ 0.012 | |||

| IL-2 | ↑ <0.001 | ↓ 0.006 | ||

| IL-4 | ↑ 0.023 | ↓ 0.031 | ||

| IL-5 | ↑ 0.002 | ↓ 0.015 | ||

| IL-6 | ↓ 0.029 | |||

| IL-10 | ↓ 0.063 | |||

| IL-12p70 | ↑ <0.001 | ↑ 0.021 | ↓ 0.056 | |

| IL-13 | ↑ 0.010 | ↓ <0.001 | ||

| IL-17A | ↑ 0.001 | ↓ 0.042 | ||

| IL-18 | ↑ 0.059 | |||

| Leptin | ↑ 0.001 | ↑ <0.001 | ||

| LIX | ↓ 0.039 | ↑ 0.028 | ||

| MCP-1 | ↑ <0.001 | |||

| MIP-1α | ↑ <0.001 | ↓ 0.017 | ||

| MIP-2 | ↓ 0.004 | |||

| RANTES | ↓ 0.038 | ↑ 0.024 | ||

| TNFα | ↑ <0.001 | |||

| VEGF | ↓ 0.003 | |||

| CRP | ↓ <0.001 | |||

| Adiponectin | ↑ <0.001 | ↑ <0.001 |

Data analyzed by four-way ANOVA. All P > 0.01: GM-CSF, GRO/KC/CINC1, IL-1α, IL-1β, IP-10, up arrow indicates an increase as a main effect; down arrow indicates a decrease as a main effect. Bold indicates P < 0.05. Cytokine data from eve multiplex array are found in Supplemental File S2.

RESULTS

The increase in body weight with age was augmented by the HFD started at weaning (3 wk of age) (Fig. 1). The rats receiving an HFD from weaning diverged from the control diet at 7 wk of age in females and 10 wk of age in males. There was no effect of a single-strain probiotic (Lp299v) on the augmenting effect of HFD on weight gain, so the ± Lp299v rats within each diet were combined for statistical analysis.

The complete body composition data are presented in Supplemental File S1. The main finding, as expected, was that the percent body fat was significantly increased by the HFD (Fig. 2; Table 1). There was no effect of Lp299v on the increase in percent fat. Considering the increase in percent fat, there were, not surprisingly, also significant effects on fat in grams, percent fat-free mass, and percent hydration (Table 1 and Supplemental File S1).

SNI induced cold allodynia, thermal hypersensitivity, and mechanical hyperalgesia in adolescent (9-wk-old) male and female rats was maintained in adult (14-wk-old) rats (Fig. 3). There were no major effects of HFD or Lp299v from weaning on any pain phenotype in adolescent rats (Fig. 3). There was a tendency in adolescent males on the control (Ctl) diet with Lp299v intake to be more sensitive to heat [red circles; 9.0 ± 1.1 (n = 14), P = 0.056] compared with males on the control diet and placebo [blue circles; 12.4 ± 1.3 (n = 14)]. The only major finding in adults at week 14 was that male rats on a control diet and placebo were more sensitive to cold compared with the Lp299v group. In other words, Lp299v decreased sensitivity to cold.

Serum leptin was increased by HFD in adolescent and adult male and female rats (Fig. 4). Of interest was that Lp299v tended to augment the HFD-induced increase in serum leptin in female adolescents (P = 0.058), but this was not observed in adult females.

To present the comparisons of 29 different cytokines that were measured, Table 2 shows the main effects with P < 0.01 [age, diet, probiotic (Lp299v), sex] from the four-way ANOVA. The arrow indicates whether the main effect was an increase in the measured cytokine (i.e., adult greater or less than adolescent, HFD greater or less than control diet, Lp299v greater or less than placebo, and female greater or less than male). Notice that, for the most part, the adults had higher cytokine levels, HFD increased cytokine levels, Lp299v reduced cytokine levels, and females had higher cytokine levels than males. The complete cytokine datasets and statistical analyses are presented in Supplemental Files S2 and S3.

The most striking effect from Table 2 was the effect of the different treatments on serum IL12p70 (Fig. 5). Although the adolescent males did not show an effect, HFD reduced IL12p70 concentrations in female adolescents, and the addition of Lp299v to the diet reversed the effect. In adult males and females, HFD increased serum IL12p70; Lp299v intake reduced IL-12p70 in adult males independently of HFD (P = 0.019).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine, in Long-Evans rats, if an HFD started at weaning influenced neuropathic pain and altered an array of cytokines and adipokines, and whether probiotic (Lp299v) started at the same time affected this phenotype. First, there was no effect of Lp299v on body weight gain in rats on the control diet or the body weight gain that was subtly augmented by HFD. Second, we did not find major changes in the pain phenotype in adolescents. In adult males, there was an effect of HFD and Lp299v on the time of cold withdrawal. There were no major effects on the pain phenotype in females at either age. Third, as expected, serum leptin was increased by the HFD at both ages. Lp299v started at weaning augmented the leptin response to HFD in adolescent female rats. This effect was lost in adulthood. Fourth, there were a variety of effects of HFD and/or Lp299v on the array of serum cytokines. Overall, an HFD increased serum cytokines, whereas the single-strain probiotic we used (Lp299v) decreased most cytokines measured. Of the few cytokines/adipokines affected by sex, LIX, RANTES, and adiponectin were higher in females, whereas G-CSF was lower in females.

Neuropathic pain can account for 10–30% of patients attending pediatric pain clinics (51), and the prevalence in adults is estimated at 3–17% (52). A spared nerve injury paradigm was specifically selected for this study because neuroinflammation is a feature of neuropathic pain, releasing peripheral inflammatory mediators that sensitize the peripheral and central nervous systems contributing to pain initiation and maintenance (23, 53). Chronic pain, including neuropathic pain, is commonly comorbid with obesity, with inflammatory mediators playing an important role in the pathophysiology of both conditions (19, 32, 54–57). Therefore, we examined the effect of diet on pro- and anti-inflammatory markers in an established rat model of neuropathic pain. For this etiology of pain in adolescent and adult rats, neither HFD nor Lp299v affected cold allodynia, thermal hypersensitivity, or mechanical hyperalgesia. The singular difference was found in adult males that were more sensitive to cold on a control diet with placebo. Others have reported probiotic-induced reductions in cold, and to a lesser extent heat sensitivity, in neuropathic pain in male rats (58). These data suggest not only that a probiotic could be effective in reducing some pain profiles but also that probiotic intervention could be more effective for pain relief in males. We were surprised that an HFD did not consistently lead to an increased pain phenotype as this is an established model of obesity (using HFD) known to develop a pain phenotype in the outbred Long-Evans or Sprague-Dawley rat as previously described and validated (34, 35, 59). The complex pathophysiology of neuropathic pain includes acute, perhaps transient, inflammatory processes (60) that we anticipated would be exacerbated by diet-induced proinflammatory mediators, especially in the acute time frame after SNI. Previous studies primarily addressed inflammatory pain (34, 35, 59), which is fundamentally different from neuropathic pain (23, 61). The present study agrees with the lack of effect of HFD on heat hypersensitivity (35), but observed contrasting effects on cold allodynia (34), and did not address mechanical allodynia (34) but found no effect on mechanical hyperalgesia. Neuropathic pain may have a limited inflammatory component compared with surgical or immune-related pain models, minimizing the compounded insult of HFD. These data suggest that the pain model and assessment may contribute to different outcomes.

Another difference in our study may have been starting the HFD at weaning rather than later in development, as done in most studies. It is possible that this may have allowed the rats sufficient time to adapt to the increase in fat mass and inflammatory cytokines, preventing the development of a more striking pain phenotype. Clearly, HFD started in older rats and for longer periods leads to greater increases in body fat mass and a more consistent pain phenotype (34, 35, 62). The composition of the HFD could also be a factor, but both body weight and percent body fat increased significantly in this study, as expected. That said, it is possible that a diet with added sucrose may have produced a more striking change in pain phenotype (63). This may also account for the lack of an effect of Lp299v on weight gain with HFD. An attenuation of weight gain has been demonstrated in rabbits on a “cafeteria” diet containing Lp299v (64).That the subtly augmented weight gain we demonstrated with HFD was not affected by Lp299v separates out weight and body composition from the calculus and allows us to examine the interaction of Lp299v and fat mass per se without the confounder of Lp299v-induced differences in these variables.

The increase in serum leptin due to HFD was augmented in adolescent female rats consuming Lp299v and HFD. No effects of Lp299v were observed in the other groups. A meta-analysis has found that probiotic (none of which used Lp299v) resulted in a decrease in plasma leptin in overweight children or children with obesity (65); however, no distinction between male and female was apparently made in this meta-analysis. Probiotic LpIMC510 administered to adult male rats on a “cafeteria diet” has been shown to decrease plasma leptin (66). Lp299v has been found to decrease leptin in smokers with increased fibrinogen levels (67). We are unaware of other studies in rats that examined the interaction of HFD and probiotics in adolescent females. There are well-known sexually dimorphic and developmental interactions with leptin in the laboratory rodent that may be mediated by gonadal steroids (68–70) The novel finding of an interaction between HFD and probiotic on leptin in females only is worthy of pursuit considering the far-reaching physiological, pathophysiological, and sexually dimorphic effects of leptin (69, 71–73).

There were many main effects of age, diet, and/or probiotic on the large array of serum cytokines and adipokines we analyzed. In general, adults and HFD-fed rats had higher serum biomarkers, whereas rats with Lp299v in their diet had lower plasma biomarkers. This general finding is consistent with other studies showing decreased systemic inflammation with Lp299v in adult humans (33, 74). We chose to focus on IL-12p70 because of the effect of age (increased), diet (increased), and probiotic (decreased). IL-12 is composed of p35 and p40 subunits, which, when combined, form the bioactive heterodimer IL-12p70 (75, 76). Furthermore, IL12p70 has been shown to be associated with waist circumference in adult humans (77). It was of particular interest that Lp299v resulted in an overall, dietary fat-independent decrease in IL-12p70 in adult males but not females suggesting sexual dimorphisms in the effect of a single-strain probiotic.

Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α (MIP1α) is also a fascinating cytokine that was increased by HFD and decreased by probiotic regardless of age or sex. MIP1α recruits inflammatory cells such as monocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils in the adipose tissue and, therefore, is associated with obesity (78). It has been shown to be decreased by probiotic (79). Furthermore, MIP1α in mice on an HFD shows an interaction with dietary probiotic in a manner similar to our findings in rats (80). Many other biomarkers that we measured showed significant main effects (Table 1). Given the hypothesis that obesity-induced inflammation could influence pain through immune system activation (19, 21), these findings may shed light on mechanisms underlying an obesity-chronic pain link, and IL12p70 and MIP1α seem to be the most intriguing for follow-up considering their changes in response to age, HFD, and probiotic.

Perspectives and Significance

It does not appear that our more subtle model of dietary-induced obesity dramatically altered pain phenotypes associated with neuropathy. This suggests that a more aggressive dietary intervention with higher fat and added sucrose, such as the cafeteria diet described above, or an inflammatory pain model should be considered. That said, the multiple effects of probiotic per se may shed light on the association between obesity and chronic pain. These hypotheses are currently being investigated by our team, including human studies and an analysis of the fecal microbiome.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Files S1–S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25471177.v1.

GRANTS

This project was funded in part by the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment. C.D. is funded by a Merit Review Award RX002747 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation, Research, and Development Service.

DISCLAIMERS

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

DISCLOSURES

H.R. is a consultant for Cerium Pharmaceuticals, Corcept Therapeutics, and Novo-Nordisk. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.R., K.R.H., V.L.W., and C.D. conceived and designed research; H.R., V.L.W., D.W., and C.D. performed experiments; H.R., K.R.H., V.L.W., D.W., X.W., and C.D. analyzed data; H.R., K.R.H., D.W., X.W., and C.D. interpreted results of experiments; H.R., X.W., and C.D. prepared figures; H.R. drafted manuscript; H.R., K.R.H., V.L.W., X.W., and C.D. edited and revised manuscript; H.R., K.R.H., V.L.W., D.W., X.W., and C.D. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Medical College of Wisconsin Department of Medicine Statistical Support Service for performing the complex statistical evaluation of the data. The authors also thank Connie Grobe, John Reho, and Justin Grobe for their advice about the HFD and performing the body composition analysis; Cheryl Stucky and Sam Zorn for their initial input and pilot studies; Michelle Bordas, Grant Broeckel, Jennifer Callison, and Gabby Mraz for their help with sample collection; and Gunilla Önning and Probi AB for supplying the probiotic and its placebo and providing advice about their use.

REFERENCES

- 1. Finley G, MacLaren Chorney J, Campbell L. Not small adults: the emerging role of pediatric pain services. Can J Anaesth 61: 180–187, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 152: 2729–2738, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hassett AL, Hilliard PE, Goesling J, Clauw DJ, Harte SE, Brummett CM. Reports of chronic pain in childhood and adolescence among patients at a tertiary care pain clinic. J Pain 14: 1390–1397, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bushnell MC, Case LK, Ceko M, Cotton V, Gracely J, Low L, Pitcher M, Villemure C. Effect of environment on the long-term consequences of chronic pain. Pain 156, Suppl 1: S42–S49, 2015. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460347.77341.bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Main C. The importance of psychosocial influences on chronic pain. Pain Manag 3: 455–466, 2013. doi: 10.2217/pmt.13.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mogil JS. Pain genetics: past, present and future. Trends Genet 28: 258–266, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Freeman L, Haley-Zitlin V, Rosenberger D, Granholm A. Damaging effects of a high-fat diet to the brain and cognition: a review of proposed mechanisms. Nutr Neurosci 17: 241–251, 2014. doi: 10.1179/1476830513Y.0000000092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morales Camacho WJ, Molina Diaz JM, Plata Ortiz S, Plata Ortiz JE, Morales Camacho MA, Calderon BP. Childhood obesity: aetiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 35: e3203, 2019. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farello G, Ferrara P, Antenucci A, Basti C, Verrotti A. The link between obesity and migraine in childhood: a systematic review. Ital J Pediatr 43: 27, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13052-017-0344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Widhalm HK, Marlovits S, Welsch GH, Dirisamer A, Neuhold A, van Griensven M, Seemann R, Vécsei V, Widhalm K. Obesity-related juvenile form of cartilage lesions: a new affliction in the knees of morbidly obese children and adolescents. Eur Radiol 22: 672–681, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Widhalm HK, Seemann R, Hamboeck M, Mittlboeck M, Neuhold A, Friedrich K, Hajdu S, Widhalm K. Osteoarthritis in morbidly obese children and adolescents, an age-matched controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24: 644–652, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dasari VR, Clark AJ, Boorigie ME, Gerson T, Connelly MA, Bickel JL. The influence of lifestyle factors on the burden of pediatric migraine. J Pediatr Nurs 57: 79–83, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Nelson TD, Kabbouche MA, Winner P, Yonker M, Linder SL, Bicknese A, Sowel MK, McClintock W; American Headache Society Pediatric Adolescent Section. Obesity in the pediatric headache population: a multicenter study. Headache 49: 170–177, 2009. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arranz L, Rafecas M, Alegre C. Effects of obesity on function and quality of life in chronic pain conditions. Curr Rheumatol Rep 16: 390, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paulis W, Silva S, Koes B, van Middelkoop M. Overweight and obesity are associated with musculoskeletal complaints as early as childhood: a systematic review. Obes Rev 15: 52–67, 2014. doi: 10.1111/obr.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reichelt A, Gibson G, Abbott K, Hare D. A high-fat high-sugar diet in adolescent rats impairs social memory and alters chemical markers characteristic of atypical neuro- plasticity and parvalbumin interneuron depletion in the medial prefrontal cortex. Food Funct 10: 1985–1998, 2019. doi: 10.1039/c8fo02118j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boitard C, Maroun M, Tantot F, Cavaroc A, Sauvant J, Marchand A, Layé S, Capuron L, Darnaudery M, Castanon N, Coutureau E, Vouimba R-M, Ferreira G. Juvenile obesity enhances emotional memory and amygdala plasticity through glucocorticoids. J Neurosci 35: 4092–4103, 2015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3122-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Großschädl F, Freidl W, Rásky E, Burkert N, Muckenhuber J, Stronegger W. A 35-year trend analysis for back pain in Austria: the role of obesity. PLoS One 9: e107436, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okifuji A, Hare B. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J Pain Res 8: 399–408, 2015. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S55598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lumeng C. Innate immune activation in obesity. Mol Aspects Med 34: 12–29, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paz-Filho G, Mastronardi C, Franco C, Wang K, Wong M, Licinio J. Leptin: molecular mechanisms, systemic pro-inflammatory effects, and clinical implications. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 56: 597–607, 2012. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302012000900001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tian Y, Wang S, Ma Y, Lim G, Kim H, Mao J. Leptin enhances NMDA-induced spinal excitation in rats: a functional link between adipocytokine and neuropathic pain. Pain 152: 1263–1271, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ellis A, Bennett D. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br J Anaesth 111: 26–37, 2013. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Jongh RF, Vissers KC, Meert TF, Booij LH, De Deyne CS, Heylen RJ. The role of interleukin-6 in nociception and pain. Anesth Analg 96: 1096–1103, 2003. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000055362.56604.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tal M. A role for inflammation in chronic pain. Curr Rev Pain 3: 440–446, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s11916-999-0071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gupta S, Viotti A, Eichwald T, Roger A, Kaufmann E, Othman R, Ghasemlou N, Rafei M, Foster SL, Talbot S. Navigating the blurred path of mixed neuro-immune signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol 153: 924–938, 2024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wood MJ, Miller RE, Malfait AM. The genesis of pain in osteoarthritis: inflammation as a mediator of osteoarthritis pain. Clin Geriatr Med 38: 221–238, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo R, Chen LH, Xing C, Liu T. Pain regulation by gut microbiota: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Br J Anaesth 123: 637–654, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Roos NM, van Hemert S, Rovers JMP, Smits MG, Witteman BJM. The effects of a multispecies probiotic on migraine and markers of intestinal permeability-results of a randomized placebo-controlled study. Eur J Clin Nutr 71: 1455–1462, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Roos NM, Giezenaar CG, Rovers JM, Witteman BJ, Smits MG, van Hemert S. The effects of the multispecies probiotic mixture Ecologic(R)Barrier on migraine: results of an open-label pilot study. Benef Microbes 6: 641–646, 2015. doi: 10.3920/BM2015.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raff H, Phillips JM, Simpson PM, Weisman SJ, Hainsworth KR. Serum soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in adolescents: interaction of chronic pain and obesity. Pain Rep 5: e836, 2020. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hainsworth KR, Simpson PM, Raff H, Grayson MH, Zhang L, Weisman SJ. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers in adolescents: evidence of interactions between chronic pain and obesity. Pain Rep 6: e916, 2021. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Malik M, Suboc TM, Tyagi S, Salzman N, Wang J, Ying R, Tanner MJ, Kakarla M, Baker JE, Widlansky ME. Lactobacillus plantarum 299v supplementation improves vascular endothelial function and reduces inflammatory biomarkers in men with stable coronary artery disease. Circ Res 123: 1091–1102, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Song Z, Xie W, Chen S, Strong JA, Print MS, Wang JI, Shareef AF, Ulrich-Lai YM, Zhang JM. High-fat diet increases pain behaviors in rats with or without obesity. Sci Rep 7: 10350, 2017. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10458-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Song Z, Xie W, Strong JA, Berta T, Ulrich-Lai YM, Guo Q, Zhang JM. High-fat diet exacerbates postoperative pain and inflammation in a sex-dependent manner. Pain 159: 1731–1741, 2018. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Percie Du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, Emerson M, Garner P, Holgate ST, Howells DW, Karp NA, Lazic SE, Lidster K, MacCallum CJ, Macleod M, Pearl EJ, Petersen OH, Rawle F, Reynolds P, Rooney K, Sena ES, Silberberg SD, Steckler T, Würbel H. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. BMJ Open Sci 4: e100115, 2020. doi: 10.1136/bmjos-2020-100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sengupta P. The laboratory rat: relating its age with human's. Int J Prev Med 4: 624–630, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schneider M. Adolescence as a vulnerable period to alter rodent behavior. Cell Tissue Res 354: 99–106, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Green PG, Alvarez P, Levine JD. A role for gut microbiota in early-life stress-induced widespread muscle pain in the adult rat. Mol Pain 17: 17448069211022952, 2021. doi: 10.1177/17448069211022952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dean C, Hillard CJ, Seagard JL, Hopp FA, Hogan QH. Upregulation of fatty acid amide hydrolase in the dorsal periaqueductal gray is associated with neuropathic pain and reduced heart rate in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 312: R585–R596, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00481.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology 101: 476–487, 2004. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sherman K, Woyach V, Eisenach JC, Hopp FA, Cao F, Hogan QH, Dean C. Heterogeneity in patterns of pain development after nerve injury in rats and the influence of sex. Neurobiol Pain 10: 100069, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2021.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gemes G, Rigaud M, Dean C, Hopp F, Hogan Q, Seagard J. Baroreceptor reflex is suppressed in rats that develop hyperalgesia behavior after nerve injury. Pain 146: 293–300, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bennett M. The LANSS pain scale: the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain 92: 147–157, 2001. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scholz J, Mannion RJ, Hord DE, Griffin RS, Rawal B, Zheng H, Scoffings D, Phillips A, Guo J, Laing RJ, Abdi S, Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. A novel tool for the assessment of pain: validation in low back pain. PLoS Med 6: e1000047, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu HE, Gemes G, Zoga V, Kawano T, Hogan QH. Learned avoidance from noxious mechanical simulation but not threshold semmes weinstein filament stimulation after nerve injury in rats. J Pain 11: 280–286, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reho JJ, Nakagawa P, Mouradian GC Jr, Grobe CC, Saravia FL, Burnett CML, Kwitek AE, Kirby JR, Segar JL, Hodges MR, Sigmund CD, Grobe JL. Methods for the comprehensive in vivo analysis of energy flux, fluid homeostasis, blood pressure, and ventilatory function in rodents. Front Physiol 13: 855054, 2022. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.855054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miller ES, Apple CG, Kannan KB, Funk ZM, Plazas JM, Efron PA, Mohr AM. Chronic stress induces persistent low-grade inflammation. Am J Surg 218: 677–683, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Raff H, Hoeynck B, Jablonski M, Leonovicz C, Phillips JM, Gehrand AL. Insulin sensitivity, leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and testosterone in adult male and female rats after maternal-neonatal separation and environmental stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314: R12–R21, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00271.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Curtis MJ, Alexander S, Cirino G, Docherty JR, George CH, Giembycz MA, Hoyer D, Insel PA, Izzo AA, Ji Y, MacEwan DJ, Sobey CG, Stanford SC, Teixeira MM, Wonnacott S, Ahluwalia A. Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. Br J Pharmacol 175: 987–993, 2018. doi: 10.1111/bph.14153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Walker SM. Neuropathic pain in children: Steps towards improved recognition and management. EBioMedicine 62: 103124, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cavalli E, Mammana S, Nicoletti F, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. The neuropathic pain: an overview of the current treatment and future therapeutic approaches. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 33: 2058738419838383, 2019. doi: 10.1177/2058738419838383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moalem G, Tracey DJ. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Rev 51: 240–264, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kraychete DC, Sakata RK, Issy AM, Bacellar O, Jesus RS, Carvalho EM. Proinflammatory cytokines in patients with neuropathic pain treated with Tramadol. Rev Bras Anestesiol 59: 297–303, 2009. doi: 10.1590/s0034-70942009000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pedersen LM, Schistad E, Jacobsen LM, Roe C, Gjerstad J. Serum levels of the pro-inflammatory interleukins 6 (IL-6) and -8 (IL-8) in patients with lumbar radicular pain due to disc herniation: a 12-month prospective study. Brain Behav Immun 46: 132–136, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stürmer T, Raum E, Buchner M, Gebhardt K, Schiltenwolf M, Richter W, Brenner H. Pain and high sensitivity C reactive protein in patients with chronic low back pain and acute sciatic pain. Ann Rheum Dis 64: 921–925, 2005. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.027045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Austin PJ, Berglund AM, Siu S, Fiore NT, Gerke-Duncan MB, Ollerenshaw SL, Leigh SJ, Kunjan PA, Kang JW, Keay KA. Evidence for a distinct neuro-immune signature in rats that develop behavioural disability after nerve injury. J Neuroinflammation 12: 96, 2015. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shabani M, Hasanpour E, Mohammadifar M, Bahmani F, Talaei SA, Aghighi F. Evaluating the effects of probiotic supplementation on neuropathic pain and oxidative stress factors in an animal model of chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. Basic Clin Neurosci 14: 375–384, 2023. doi: 10.32598/bcn.2022.3772.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Totsch SK, Quinn TL, Strath LJ, McMeekin LJ, Cowell RM, Gower BA, Sorge RE. The impact of the standard American diet in rats: effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury. Scand J Pain 17: 316–324, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Safieh-Garabedian B, Nomikos M, Saadé N. Targeting inflammatory components in neuropathic pain: the analgesic effect of thymulin related peptide. Neurosci Lett 702: 61–65, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu Q, Yaksh TL. A brief comparison of the pathophysiology of inflammatory versus neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 24: 400–407, 2011. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834871df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fu CN, Wei H, Gao WS, Song SS, Yue SW, Qu YJ. Obesity increases neuropathic pain via the AMPK-ERK-NOX4 pathway in rats. Aging (Albany NY) 13: 18606–18619, 2021. doi: 10.18632/aging.203305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Collins KH, MacDonald GZ, Hart DA, Seerattan RA, Rios JL, Reimer RA, Herzog W. Impact of age on host responses to diet-induced obesity: development of joint damage and metabolic set points. J Sport Health Sci 9: 132–139, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bouaziz A, Dib AL, Lakhdara N, Kadja L, Espigares E, Moreno E, Bouaziz O, Gagaoua M. Study of probiotic effects of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 and Lactobacillus plantarum 299v strains on biochemical and morphometric parameters of rabbits after obesity induction. Biology (Basel) 10: 131, 2021. doi: 10.3390/biology10020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li Y, Liu T, Qin L, Wu L. Effects of probiotic administration on overweight or obese children: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Transl Med 21: 525, 2023. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04319-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Micioni D, Bonaventura MV, Coman MM, Tomassoni D, Micioni D, Bonaventura E, Botticelli L, Gabrielli MG, Rossolini GM, Di Pilato V, Cecchini C, Amedei A, Silvi S, Verdenelli MC, Cifani C. Supplementation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum IMC 510 modifies microbiota composition and prevents body weight gain induced by cafeteria diet in rats. Int J Mol Sci 22: 11171, 2021. doi: 10.3390/ijms222011171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Naruszewicz M, Johansson ML, Zapolska-Downar D, Bukowska H. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum 299v on cardiovascular disease risk factors in smokers. Am J Clin Nutr 76: 1249–1255, 2002. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutr Res Rev 23: 270–299, 2010. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Asarian L, Geary N. Sex differences in the physiology of eating. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R1215–R1267, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00446.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shi Z, Wong J, Brooks VL. Obesity: sex and sympathetics. Biol Sex Differ 11: 10, 2020. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00286-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bloomgarden ZT. Adiposity and diabetes. Diabetes Care 25: 2342–2349, 2002. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dyck DJ, Heigenhauser GJ, Bruce CR. The role of adipokines as regulators of skeletal muscle fatty acid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 186: 5–16, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2005.01502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lutz TA. An overview of rodent models of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Methods Mol Biol 2128: 11–24, 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0385-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hofeld BC, Puppala VK, Tyagi S, Ahn KW, Anger A, Jia S, Salzman NH, Hessner MJ, Widlansky ME. Lactobacillus plantarum 299v probiotic supplementation in men with stable coronary artery disease suppresses systemic inflammation. Sci Rep 11: 3972, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gee K, Guzzo C, Che Mat NF, Ma W, Kumar A. The IL-12 family of cytokines in infection, inflammation and autoimmune disorders. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 8: 40–52, 2009. doi: 10.2174/187152809787582507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ullrich KA, Schulze LL, Paap EM, Muller TM, Neurath MF, Zundler S. Immunology of IL-12: an update on functional activities and implications for disease. EXCLI J 19: 1563–1589, 2020. doi: 10.17179/excli2020-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Valmorbida A, Longo GZ, Nascimento GM, de Oliveira LL, de Moraes Trindade EBS. Association between cytokine levels and anthropometric measurements: a population-based study. Br J Nutr 129: 1119–1126, 2023. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522002148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sindhu S, Akhter N, Wilson A, Thomas R, Arefanian H, Al Madhoun A, Al-Mulla F, Ahmad R. MIP-1alpha expression induced by co-stimulation of human monocytic cells with palmitate and TNF-α involves the TLR4-IRF3 pathway and is amplified by oxidative stress. Cells 9: 1799, 2020. doi: 10.3390/cells9081799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Salvesi C, Silvi S, Fiorini D, Alessandroni L, Sagratini G, Palermo FA, De Leone R, Egidi N, Cifani C, Micioni Di Bonaventura MV, Amedei A, Niccolai E, Scocchera F, Mannucci F, Valeriani V, Malavasi M, Servili S, Casula A, Cresci A, Corradetti I, Coman MM, Verdenelli MC. Six-month Synbio((R)) administration affects nutritional and inflammatory parameters of older adults included in the PROBIOSENIOR project. Microorganisms 11: 801, 2023. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11030801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Jiang S, Su Y, Wang Q, Lv L, Xue C, Xu L, Li L. Multi-omics analysis of the effects of dietary changes and probiotics on diet-induced obesity. Curr Res Food Sci 6: 100435, 2023. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2023.100435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Files S1–S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25471177.v1.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.