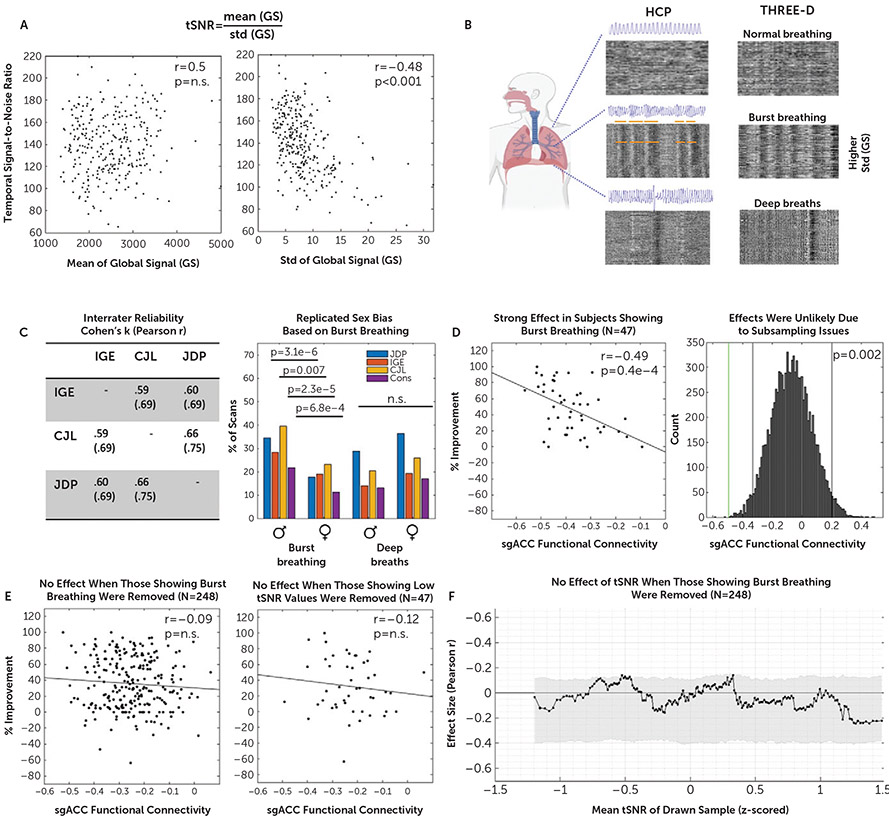

FIGURE 4. Association between functional connectivity of the stimulated site with the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC-StimFC) and clinical improvement is carried by a subpopulation of subjects with high breathing-specific signal variancea.

a As shown in panel A, low temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR) in our sample was explained by differences in signal variance (image at right) as opposed to differences in mean intensity of the fMRI signal (image at left). Panel B shows that a major source of variance in the global fMRI signal stems from breathing (20). Three blinded raters scored all 590 fMRI scans (two per subject) for the presence of two common irregular breathing patterns: burst breathing and deep breaths. Representative examples of carpet plots (rows are voxels, and columns are time points; intensity represents signal strength) are shown for normal breathing, burst breathing, and deep breaths of individuals included in the Human Connectome Project (HCP) data set (used and reproduced from [20]) and the THREE-D data set. Note the strong correspondence of characteristic patterns that are clearly identifiable without a breathing-belt trace. Panel C shows the high interrater reliability that was obtained between each pair of raters for each of the breathing patterns (Cohen’s kappa and r; table at left). A sex bias was found for the occurrence of burst breathing but not deep breaths (figure at right), which exactly replicated a previous study (20). Panel D shows that among the 47 subjects showing signal fluctuations indicative of burst breathing, sgACC-StimFC was highly predictive of clinical improvement (% improvement on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology [QIDS-SR]) (figure at left). The probability of finding an effect of this strength in a random subsample of 47 subjects was p=0.002 in 10,000 bootstrapped subsamples. Gray vertical bars present nominally significant effect sizes, and the green vertical bar marks the actual effect size (figure at right). Panel E shows that when these 47 subjects with signal fluctuations indicative of burst breathing were removed from the total sample, no significant association between sgACC-StimFC and clinical improvement remained (figure at left). The strong association was specific to samples that included those showing burst breathing and not present in a control sample of 47 subjects with equally low tSNR values (105.56 vs. 117.48 in those showing burst breathing) that did not show evidence for burst breathing (figure at right). Conversely, when this control sample was removed from the total sample, the association between sgACC-StimFC and clinical improvement was unchanged (r=−0.14, p=0.03; data not shown). As shown in panel F, the dependency of the association between sgACC-StimFC and clinical improvement on tSNR was removed in the absence of the 47 subjects with evidence for burst breathing, indicating that this phenomenon was driven by the presence of individuals showing burst breathing in the sample rather than being a consequence of nonspecific sources of high signal variance. One subject with a QIDS-SR improvement of −150% was omitted for illustrative purposes; the subject was included in all test statistics.