ABSTRACT

The increasing clinical significance of Mycobacterium abscessus is owed to its innate high-level, broad-spectrum resistance to antibiotics and therefore rapidly evolves as an important human pathogen. This warrants the identification of novel targets for aiding the discovery of new drugs or drug combinations to treat M. abscessus infections. This study is inspired by the drug-hypersensitive profile of a mutant M. abscessus (U14) with transposon insertion in MAB_1915. We validated the role of MAB_1915 in intrinsic drug resistance in M. abscessus by constructing a selectable marker-free in-frame deletion in MAB_1915 and complementing the mutant with the same or extended version of the gene and then followed by drug susceptibility testing. Judging by the putative function of MAB_1915, cell envelope permeability was studied by ethidium bromide accumulation assay and susceptibility testing against dyes and detergents. In this study, we established genetic evidence of the role of MAB_1915 in intrinsic resistance to rifampicin, rifabutin, linezolid, clarithromycin, vancomycin, and bedaquiline. Disruption of MAB_1915 has also been observed to cause a significant increase in cell envelope permeability in M. abscessus. Restoration of resistance is observed to depend on at least 27 base pairs upstream of the coding DNA sequence of MAB_1915. MAB_1915 could therefore be associated with cell envelope permeability, and hence its role in intrinsic resistance to multiple drugs in M. abscessus, which presents it as a novel target for future development of effective antimicrobials to overcome intrinsic drug resistance in M. abscessus.

IMPORTANCE

This study reports the role of a putative fadD (MAB_1915) in innate resistance to multiple drugs by M. abscessus, hence identifying MAB_1915 as a valuable target and providing a baseline for further mechanistic studies and development of effective antimicrobials to check the high level of intrinsic resistance in this pathogen.

KEYWORDS: Mycobacterium abscessus, MAB_1915, fatty acid-CoA ligase, cell envelope permeability, intrinsic drug resistance

INTRODUCTION

Mycobacteria can be fast- or slow-growing. The slow growers include members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Mycobacterium abscessus belongs to the fast-growing group and is an opportunistic pathogen that poses a serious public health threat, particularly in the presence of underlying host factors such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, compromised immunity, and co-infection with other bacteria (1). Lipid metabolic genes such as fatty acid-CoA ligases (FACLs/FadDs) are important to mycobacteria in virulence and successful establishment of infection in their hosts (1–6). The importance of FadDs to mycobacteria could be deduced from their sheer numbers in these bacteria. For example, the genomes of each of M. abscessus and M. smegmatis encode no less than 30 FadDs, whereas that of M. tuberculosis encodes 36 (2). This therefore entails possible redundancies or varying roles of these genes (2, 7, 8), which indicates their importance in mycobacterial lipid metabolism.

M. abscessus is a non-tuberculous species that is rapidly evolving as an important human pathogen. Its public health significance cannot be ignored due to its innate high-level, broad-spectrum resistance to available antibiotics (9). This is owed to a plethora of innate, adaptive, and acquired genetic mechanisms of drug resistance in this pathogen (1, 6), including intrinsic impermeability of the mycobacterial cell envelope (1, 10). This is because the mycobacterial cell envelope is heavily guarded by a collection of lipids and mycolic acids (11–15), the biosynthesis of which is influenced by FadDs (6, 16). The apparent importance of lipid metabolic genes warrants investigation to explore whether they could be presented as promising targets in future development of antimicrobials to address the intrinsic high-level, broad-spectrum resistance to drugs by M. abscessus.

This study was inspired by the drug sensitivity profile of a mutant M. abscessus strain with transposon (Tn) insertion in a putative fadD (MAB_1915) that appears to show increased sensitivity to rifampicin. We further established the genetic evidence of the role of this gene, which has previously been implicated in α’-mycolate biosynthesis in M. abscessus ATCC 19977 (6), in intrinsic resistance to multiple drugs. We therefore present MAB_1915 as a novel target for further studies and future development of effective chemotherapeutic regimens against M. abscessus infections.

RESULTS

MAB_1915 mediates drug resistance in M. abscessus

The mutant M. abscessus U14 sustained a Tn insertion in MAB_1915 (Fig. 1A), which encodes a putative FadD. We have reported the details of Tn mutagenesis and library screening elsewhere (17). In the present study, we carried out further genetic evaluation to investigate the possible role of MAB_1915 in intrinsic drug resistance in M. abscessus.

Fig 1.

Tn insertion and construction of an in-frame disruption in MAB_1915. A Position of Tn insertion in U14, a Tn insertion mutant in which the Tn is seen to integrate into M. abscessus chromosome between “T” and “A” dinucleotides at positions 61 and 62 within MAB_1915, respectively. This study was inspired by the drug-sensitivity profile of this mutant. The 272-bp intergenic region between MAB_1915 and MAB_1914c is also shown. B Depiction of the construction of AES, in-frame disruption of MAB_1915 by allelic exchange and unmarking of the gene disruption mutant. C Verification of gene disruption by amplifying the junctions between the chromosome of M. abscessus and the inserted zeoR cassette. Lane M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1 and 2, MabWt and ∆MAB_1915 mutant, respectively (primers a/c, 726 bp); lanes 2 and 4, MabWt and ∆MAB_1915 mutant, respectively (primers d/b, 1154 bp). D Verification of knockout by amplifying (primers e/f) disrupted MAB_1915 in MabWt, ∆MAB_1915 mutant, and unmarked ∆MAB_1915 mutant (Un1915). Lane M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lane 1, MabWt (2672 bp); lane 2, ∆MAB_1915 mutant (2564 bp); lane 3, Un1915 (1964 bp).

An in-frame deletion mutant of M. abscessus for MAB_1915 (∆MAB_1915) was generated using an allelic exchange substrate (AES) comprising a Zeocin (ZEO) resistance cassette (with dif sites at both ends) sandwiched between upstream and downstream arms of MAB_1915, with both arms containing flanking sequences from adjacent genes (Fig. 1B). Gene disruption was verified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing, which reveals that a 708-bp fragment within MAB_1915 was replaced by the ZEO resistance cassette (Fig. 1B). This was further verified by PCR amplification of junctions between the ZEO resistance cassette and M. abscessus chromosome (Fig. 1B and C). PCR products from the ∆MAB_1915 mutant have bands at both junctions, which were absent in MabWt (Fig. 1C), further confirming successful disruption of MAB_1915. The ZEO resistance cassette was excised prior to downstream studies using the Xer/dif excision system (18) to minimize possible polar effects from the ZEO resistance marker on the expression of downstream genes on the M. abscessus chromosome. The resulting strain was verified by PCR and sequencing (Fig. 1B and D), then designated unmarked ∆MAB_1915 mutant (Un1915), and used as the background strain for construction of complemented (CP) strains.

The drug susceptibility profile of the ∆MAB_1915 mutant was checked against rifampicin to validate the phenotype of the Tn insertion mutant. Drug susceptibility testing (DST) reveals that MAB_1915 disruption sensitizes M. abscessus to not only RIF but also to linezolid (LZD), vancomycin (VAN), rifabutin (RFB), clarithromycin (CLA), and bedaquiline (BDQ) when screened by broth microdilution (Table 1). In addition, the strain has also been observed to show some level of susceptibility to clofazimine (CLF) and levofloxacin (LEV) when screened by spot culture growth inhibition (SPOTi) (Fig. 2). Together, this demonstrates the significant impact of MAB_1915 disruption on the drug susceptibility profile of M. abscessus. To verify whether the gene is indeed responsible for resistance to those drugs, the coding DNA sequence (CDS) of MAB_1915 was expressed in Un1915 to construct the CP strain CPMab to check for restoration of the resistance phenotype by broth microdilution. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of all the drugs were consistently lower against MabKO than those against MabWt and remained unchanged after complementation (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibility testing of strains by broth microdilution

| Strains | Characteristics of the strainsa | Drugs/MIC (µg/mL)b | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIF | LZD | RFB | CLA | VAN | BDQ | CLFc | LEVc | IMP | EMB | CFX | TGC | AMK | ||

| MabWt | The wild-type M. abscessus | 128 | 64 | 8 | 4 | 128 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 8 | 16 |

| MabKO | Un1915::pMV261 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | 4 | 16 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 8 | 16 |

| CPMab | Un1915::hsp60-MAB_1915 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0.5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CPPsc1 | Un1915::hsp60-Psc1-MAB_1915 | 128 | 64 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 4 | 4 | 16 | − | − | − | − | − |

| CPPsc2 | Un1915::hsp60-Psc2-MAB_1915 | 128 | 64 | 8 | 4 | 64 | 4 | 4 | 16 | − | − | − | − | − |

Un1915, unmarked MAB_1915 knockout strain. pMV261, the empty extra-chromosomal plasmid. hsp60, the strong mycobacterial promoter. Psc, presumed start codon. Psc1 and Psc2 contain 69 and 27 bp from the upstream region (272 bp) of MAB_1915 (Fig. 3), respectively.

-, not determined (because MabKO was not hyper-susceptible to these drugs); RIF, rifampicin; LZD, linezolid; RFB, rifabutin; CLA, clarithromycin; VAN, vancomycin; BDQ, bedaquiline; CLF, clofazimine; LEV, levofloxacin; IMP, imipenem; EMB, ethambutol; CFX, cefoxitin; TGC, tigecycline; AMK, amikacin.

MabKO was more susceptible to CLF and LEV on the agar plate (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Drug susceptibility testing of the strains by SPOTi. MabKO is susceptible to RIF, RFB, LZD, CLA, VAN, and BDQ by both broth microdilution and SPOTi. However, it is observed to have some levels of susceptibility to CLF and LEV only on agar plates. The shown CP strains appear to partially restore resistance to the drugs.

Role of MAB_1915 in drug resistance depends on its upstream 272-bp region

Because CPMab could not restore resistance to the tested drugs, we explored whether the upstream 272-bp region (Fig. 1A) could be a player in the role of MAB_1915 in drug resistance. Therefore, we constructed another CP strain, CPUrMab, by expressing MAB_1915 together with its upstream 272-bp region in Un1915. Interestingly, this resulted in a remarkable restoration of the drug resistance phenotype (data not shown), suggesting that the role of MAB_1915 in resistance to the tested drugs could be dependent on whole or part of the 272-bp intergenic region between MAB_1914c and MAB_1915.

There were insignificant changes in MICs of the tested drugs following complementation of the mutant with the CDS of MAB_1915, demonstrating inadequate restoration of the drug resistance phenotype. However, when MAB_1915 was extended to include its upstream 272-bp region, there was an eightfold increase in the MICs of RIF, LZD, and VAN and a fourfold increase in the case of RFB and CLA (data not shown). This therefore indicates restoration of the drug resistance phenotype by CPUrMab, which expresses a version of MAB_1915 in which the CDS has been extended to include its upstream 272-bp region.

Partial extension of CDS of MAB_1915 into the 272-bp region

Because extension of MAB_1915 to include its upstream 272-bp region (Ur-MAB_1915) enables the mutant strain to restore resistance to drugs, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), malachite green, and crystal violet (Fig. 3 and 4B), we checked whether shortening Ur-MAB_1915 would also exert a similar effect. Thus, we identified two close, potentially alternative “GTG” start positions (19) near the original annotated start codon (ATG) of MAB_1915, which we designated presumed start codons 1 and 2 (Psc1 and Psc2) such that Ur-MAB_1915 Psc1-MAB_1915 Psc2-MAB_1915 MAB_1915 in length (Fig. 3). Both Psc1-MAB_1915 and Psc2-MAB_1915 begin at “GTG” positions some 69 and 27 bp upstream of the annotated “ATG” start codon of MAB_1915, respectively.

Fig 3.

Presumed start codons (Psc) upstream of MAB_1915. Two alternative “GTG” start positions were presumed some 69 and 27 bp upstream of MAB_1915. In contrast to MAB_1915, the expression of either Psc1-MAB_1915 or Psc2-MAB_1915 in the knockout strain enables partial restoration of drug resistance.

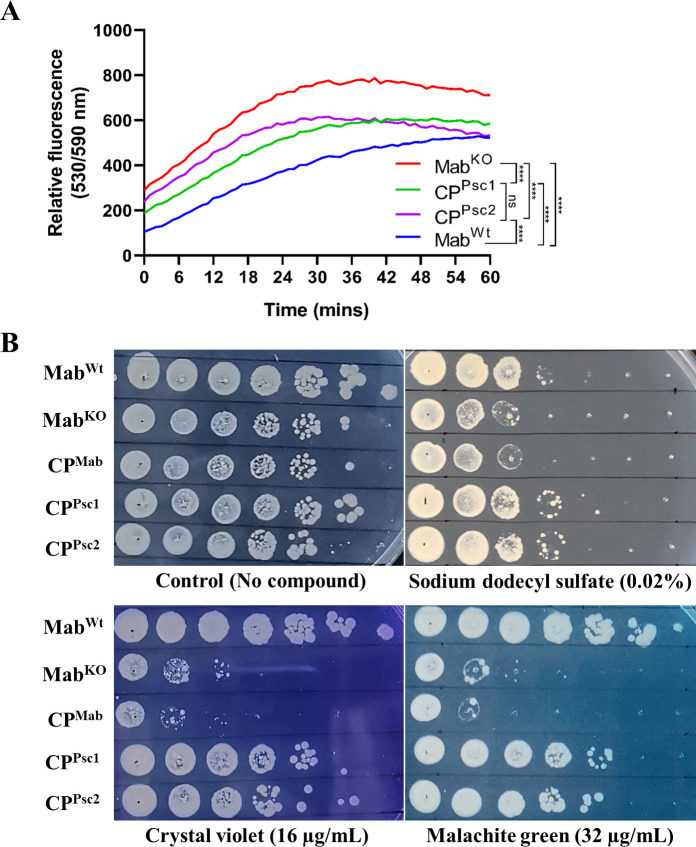

Fig 4.

Assessment of cell envelope permeability. A Accumulation of EtBr in the strains. B Susceptibility testing against dyes and detergents. MabKO accumulated more EtBr and was also observed to be relatively more sensitive to dyes and detergents in contrast to the CP strains, which perhaps results from an increase in the permeability of its cell envelope. ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

We therefore constructed two other complemented strains CPPsc1 and CPPsc2 expressing Psc1-MAB_1915 (1872 bp) and Psc2-MAB_1915 (1830 bp), respectively. We compared the drug susceptibility profiles of these strains to those of MabWt, MabKO, and CPMab and, interestingly, both strains restored resistance to all the tested drugs, as opposed to CPMab (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Drug sensitivity of MabKO could be due to increased cell envelope permeability

MAB_1915 is functionally annotated as a putative FadD, and we could therefore expect it to play an important role in lipid metabolism and perhaps cell envelope permeability. To study the possible role of this protein in determining cell envelope permeability in M. abscessus, we carried out ethidium bromide (EtBr) accumulation assay. As expected, there was an apparent increase in EtBr uptake following MAB_1915 disruption, a phenotype that was partially restored following complementation. MabKO showed a significantly higher rate of EtBr accumulation in contrast to MabWt and the two CP strains CPPsc1 and CPPsc2 (P < 0.05), suggesting a possible increase in cell envelope permeability in the knockout strain (Fig. 4A).

Susceptibility of the strains to SDS as well as malachite green and crystal violet was determined by SPOTi, in which MabKO was observed to be apparently more susceptible than MabWt, suggesting a possible increase in cell envelope permeability. Interestingly, CPPsc1 and CPPsc2 partially restored the lost phenotype (Fig. 4B). This suggests that just like in drug resistance, the association of MAB_1915 with cell envelope permeability could be dependent on its upstream region.

DISCUSSION

M. abscessus is a rapidly emerging human pathogen, and its infection is largely influenced by the presence of underlying host factors (1). This species stands out among other non-tuberculous mycobacteria for its intrinsic high level of resistance to multiple drugs (9). This certainly warrants the understanding of the genetic basis of inherent drug resistance in this pathogen.

FadDs are adenylate-forming enzymes that play key roles in mycobacterial lipid metabolism and cell envelope biogenesis. Like M. tuberculosis (2), the genomes of M. abscessus and other mycobacteria encode multiple FadDs, some of which have been shown to mediate intrinsic resistance to antibiotics (5, 6). In this study, we identified genes related to drug resistance in M. abscessus by Tn mutagenesis (20, 21) and DST. A mutant, U14, from the Tn mutant library was determined to have sustained a Tn insertion in MAB_1915 (Fig. 1A) and showed increased susceptibility to RIF.

MAB_1915 is one of the over 30 genes that encode putative FadDs in M. abscessus. Here, we established a genetic evidence of the role of MAB_1915 in drug resistance in M. abscessus by constructing a selectable marker-free in-frame deletion mutant for the gene (Fig. 1B and D) and complementing the knockout strain. Disruption of this gene was observed to significantly affect bacterial growth. A Tn insertion mutant for this gene has also been reported to show altered colony sizes and decreased growth in macrophages, suggesting that this gene could play an important role in survival of M. abscessus in macrophages (6, 22). In addition, the gene disruption has also been observed to render M. abscessus more susceptible to RIF, LZD, RFB, CLA, VAN, BDQ, CLF, and LEV (Table 1; Fig. 2). CPMab, which expresses the CDS of MAB_1915, did not restore resistance to tested drugs, SDS, malachite green, and crystal violet, which is not surprising considering previous reports of little to no complementation of phenotypes involving FadDs (7, 10, 23, 24). However, intergenic genome regions could govern gene expression (25), and promoter regions could also be important determinants of drug resistance in mycobacteria (26). This led us to suspect a possible association between the role of MAB_1915 in drug resistance and its upstream 272-bp region. We therefore constructed CPUrMab, a CP strain expressing a version of MAB_1915 in which the CDS has been extended to include the 272-bp region. Interestingly, a remarkable restoration of resistance was observed in CPUrMab (data not shown), suggesting that the role of MAB_1915 in drug resistance could be dependent on this region. This observation could be explained by possible interruption (19, 27–29) and therefore a misannotation in the CDS of MAB_1915. We therefore shortened the length of Ur-MAB_1915 (2,075 bp) to two versions Psc1-MAB_1915 (1,872 bp) and Psc2-MAB_1915 (1,830 bp) relative to the positions of two presumed “GTG” start codons (19) near the original annotated transcription start site (Fig. 3). CP strains expressing either of the shortened versions of Ur-MAB_1915 have restored their drug resistance phenotypes (Table 1; Fig. 2). In addition, a bacterial promoter prediction program (BPROM) (30) identified “gggtaatct” as a potential promoter within this region, which lies some 94 bp and 136 bp upstream of Psc1-MAB_1915 and Psc2-MAB_1915, respectively. Therefore, while the DST data clearly implicate MAB_1915 in resistance to multiple drugs by M. abscessus, the hypothesized interruption in the CDS of MAB_1915 and its relation to the promoter sequence remains to be studied.

FadDs play redundant (8) or independent roles such as synthesis of mycolic acids (16, 31) or specific lipids (10, 23, 24, 32, 33) of the mycobacterial cell envelope, which perhaps stems from their affinities for different chain lengths of fatty acids (2). We hypothesized therefore that increased drug susceptibility of the mutant strain could have resulted from altered cell envelope integrity, perhaps leading to increased permeability and easy passage of the drugs. This was tested by EtBr accumulation assay and susceptibility testing to SDS, malachite green, and crystal violet, which have been shown to be particularly bactericidal against or accumulate in bacteria with a compromised cell envelope (10, 34, 35). As expected, a higher accumulation of EtBr was observed in MabKO compared to MabWt, CPPsc1, and CPPsc2 (P < 0.0001), a phenotype that was partially restored following complementation (Fig. 4A). In addition, increased susceptibility of the knockout strain to SDS, malachite green, and crystal violet was also observed to be partially reversed following complementation with extended versions of MAB_1915 (Fig. 4B). Increased cell envelope permeability in MabKO could have resulted from defect in biosynthesis of α’-mycolates (6), which possibly caused some level of erosion of the mycobacterial cell envelope and paved the way for easier entry of drugs. α - and α’- mycolates are the two mycolic acid classes produced by M. abscessus, and disruption of MAB_1915 abolishes the biosynthesis of the latter in M. abscessus ATCC 19977. The synthesis of the former class is mediated by FadD32 in M. tuberculosis (16), the M. abscessus ortholog for which is MAB_0179. In fact, structural comparison reveals that MAB_0179 differs from MAB_1915 only in its FadD32-specific insertion SI6 (6), suggesting that development of inhibitors for these two proteins could significantly inhibit the biosynthesis of mycolic acids in M. abscessus and therefore improve the effectiveness of chemotherapy against this pathogen. In the present study, however, thin layer chromatography of mycolate extracts did not indicate a change in the TLC profile of MabKO compared to MabWt (data not shown). It is not clear whether this stems from strain variation between M. abscessus GZ002 (this study) and M. abscessus ATCC 19977 (6). For example, it is suspected that MAB_1915 plays no role in the FASII pathway and therefore is not associated with mycolic acid biosynthesis because MAB_1915 neither lies within the FASII operon of M. abscessus nor does it bear any orthology with the fabD gene (Rv2243) in the FASII operon in M. tuberculosis (36). This, however, appears to be speculative as evidence of such a role has been reported by Di Capua et al. (6). Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether this speculation is true for M. abscessus GZ002, and the potential effect of MAB_1915 disruption on mycolate composition in this strain remains to be investigated. We ruled out the inhibition of lipid biosynthesis as a possible cause for increased cell envelope permeability of the mutant strain (6), which could be explained by various redundancies that abound lipid metabolism in mycobacteria, ranging from abundance of substrate-specific FadDs to alternative means of assimilation and metabolism of fatty acids (8, 37, 38).

The mycobacterial cell envelope represents a serious impediment to chemotherapy against mycobacteria, and drug targeting of its biogenesis could yield a great therapeutic outcome. Here, we highlighted the importance of MAB_1915 to cell envelope permeability and resistance to multiple drugs in M. abscessus, hence presenting it as a novel target for development of effective antimicrobials to check the growing threat of this highly drug-resistant pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Cloning experiments were carried out in Escherichia coli DH5α. E. coli was maintained in liquid or on solid Luria–Bertani medium under selective pressure (where needed) with the following concentrations of antibiotics (µg/mL): apramycin, APR 50; kanamycin, KAN 50; ampicillin, AMP 100; zeocin, ZEO 30. M. abscessus GZ002 (NCBI GenBank accession number CP034181) was maintained in Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) medium supplemented with 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween-80, and 10% OADC or on Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% OADC. M. abscessus GZ002 is a clinical strain with a smooth morphology from Guangzhou Chest Hospital, Guangzhou, Southern China (39). Selective growth of M. abscessus (when needed) was carried out in the presence of the following concentrations of antibiotics (µg/mL): KAN 100 or ZEO 30. All liquid cultures were maintained at 37°C under agitation.

Preparation of competent M. abscessus cells

Electrocompetent cells were prepared as previously described (40–42) by washing three times in 10% glycerol. Briefly, pJV53-harboring M. abscessus cells were subcultured in Middlebrook 7H9 medium containing KAN and 0.2% succinic acid until the mid-log phase. Expression of the gp60/61 recombination proteins on pJV53 was induced by addition of 0.2% acetamide, and electrocompetent cells were prepared 5 hours later.

Construction of ∆MAB_1915

A three-fragment ligation method was used to construct an in-frame deletion of MAB_1915 in M. abscessus by allelic exchange, as described previously (40). The AES was constructed by amplifying upstream (805 bp) and downstream (916 bp) arms of MAB_1915 containing flanking sequences from adjacent genes. The amplified regions were cloned into ClaI/BamHI-linearized pBlueSK(+) by recombination to obtain pBlueSK∆MAB_1915UD. The selective marker sandwiched between two M. abscessus dif sequences (dif:zeoR:dif, 600 bp) was also amplified by PCR. Both pBlueSK∆MAB_1915UD and dif:zeoR:dif were digested by HindIII, recovered, and ligated to construct pBlueSK∆MAB_1915UZD, the final plasmid containing the AES (MAB_1915UZD). MAB_1915UZD was amplified from the vector by PCR using the primer pair a/b (Fig. 1B). About 5 µg of purified AES was transformed into electrocompetent M. abscessus:pJV53 cells by electroporation (voltage, 2,500 V; capacitance, 25 µF; resistance, 1,000 Ω). Integration of the zeoR cassette into M. abscessus chromosome was verified by amplifying the chromosome–zeoR junction using the primer pairs a/c and d/b (Fig. 1B and C), and knockout was verified by PCR using the primer pair e/f (Fig. 1B and D) and sequencing.

Construction of unmarked ∆MAB_1915 and CP strains

The zeoR cassette integrated into the ∆MAB_1915 chromosome after knockout was excised by multiple passages in the absence of selective pressure with the help of the Xer/dif system, as described previously (18). Each of several clones from passaged cells were grown on three separate plates, one containing no drug (plain), one containing ZEO, and the other containing KAN to ensure the shedding of pJV53. A colony that grows on the plain plate but not on the other two plates was selected and verified by PCR and sequencing. This colony was designated the unmarked mutant (Un1915) and was used as the background strain for construction of CP strains.

CP strains were constructed by amplifying either the annotated or extended CDS of MAB_1915 and cloning into EcoRI/HindIII-linearized pMV261 and then transformed into Un1915 by electroporation. Construction of CP strains was verified by PCR and sequencing.

DST

The bacterial strains were grown in 7H9 medium to an OD600 of 0.8–1. The resulting cultures were diluted in the same medium without Tween-80 to cell densities of ~105 CFU/mL. Broth microdilution was used to determine MICs of selected drugs against the diluted cultures in transparent 96-well microplates. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which visible growth was inhibited, and readings were recorded after 5 days of incubation at 37°C and after 14 days for CLA (43).

For DST using the SPOTi method, bacterial strains were grown in the 7H9 medium at 37℃ under agitation until OD600 0.8–1 and then diluted to OD600 0.6 in the same medium. The diluted cells or tenfold serial dilutions were spotted on plain and drug-containing Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 plates. Plates were observed after 5 days of incubation at 37℃. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which at least 99% bacterial growth was inhibited.

Ethidium bromide uptake assay

Cell envelope permeability was studied by EtBr accumulation assay (44–47) in FlexStation 3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, CA, USA) using the following parameters: temperature, 37°C; number of cycles and duration, 61 cycles of 60 seconds each; excitation and detection wavelengths, 530 nm and 595 nm, respectively. This was also studied by testing the bacterial susceptibility to two dyes (malachite green and crystal violet) and a detergent (SDS) by SPOTi (34). The concentration of EtBr used is 2 µg/mL, and susceptibility to dyes and detergents was tested on 7H11 plates and observed after 5 days of incubation at 37°C.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of EtBr accumulation between strains was carried out by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post-test to correct for multiple comparisons, at 95% CI and 0.05 significance level. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (GraphPad, CA, USA), and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1300900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973372 and 21920102003), the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grants (154144KYSB20190005 and YJKYYQ20210026), the Key R&D Program of Sichuan Province (2023YFSY0047), the State Key Laboratory of Respiratory Disease, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (SKLRD-OP-202324, SKLRD-Z-202301, SKLRD-OP-202113, and SKLRD-Z-202412). B.Y is sponsored by the ANSO PhD fellowship for international students.

Contributor Information

Shuai Wang, Email: wang_shuai@gibh.ac.cn.

Jinxing Hu, Email: hujinxing2000@163.com.

Tianyu Zhang, Email: zhang_tianyu@gibh.ac.cn.

Gyanu Lamichhane, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Johansen MD, Herrmann JL, Kremer L. 2020. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria and the rise of Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat Rev Microbiol 18:392–407. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0331-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dubois V, Viljoen A, Laencina L, Le Moigne V, Bernut A, Dubar F, Blaise M, Gaillard JL, Guérardel Y, Kremer L, Herrmann JL. 2018. MmpL8MAB controls Mycobacterium abscessus virulence and production of a previously unknown glycolipid family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E10147–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812984115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hurst-Hess K, Rudra P, Ghosh P. 2017. Mycobacterium abscessus WhiB7 regulates a species-specific repertoire of genes to confer extreme antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:10–128. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01347-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosen BC, Dillon NA, Peterson ND, Minato Y, Baughn AD. 2017. Long-chain fatty acyl coenzyme A ligase FadD2 mediates intrinsic pyrazinamide resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:10–128. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02130-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Capua CB, Belardinelli JM, Carignano HA, Buchieri MV, Suarez CA, Morbidoni HR. 2022. Unveiling the biosynthetic pathway for short mycolic acids in nontuberculous mycobacteria: Mycobacterium smegmatis MSMEG_4301 and its ortholog Mycobacterium abscessus MAB_1915 are essential for the synthesis of α′-mycolic acids. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0128822. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01288-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunphy KY, Senaratne RH, Masuzawa M, Kendall LV, Riley LW. 2010. Attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis functionally disrupted in A fatty acyl-coenzyme A synthetase gene fadD5. J Infect Dis 201:1232–1239. doi: 10.1086/651452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ikeda M, Takahashi K, Ohtake T, Imoto R, Kawakami H, Hayashi M, Takeno S. 2021. A futile metabolic cycle of fatty Acyl-CoA hydrolysis and resynthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum and its disruption leading to fatty acid production. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e02469-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02469-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shen Y, Wang X, Jin J, Wu J, Zhang X, Chen J, Zhang W. 2018. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium abscessus and Mycobacterium fortuitum isolates to 30 antibiotics. Biomed Res Int. doi: 10.1155/2018/4902941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yu J, Tran V, Li M, Huang X, Niu C, Wang D, Zhu J, Wang J, Gao Q, Liu J. 2012. Both phthiocerol dimycocerosates and phenolic glycolipids are required for virulence of Mycobacterium marinum. Infect Immun 80:1381–1389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06370-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bansal-Mutalik R, Nikaido H. 2014. Mycobacterial outer membrane is a lipid bilayer and the inner membrane is unusually rich in diacyl phosphatidylinositol dimannosides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4958–4963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403078111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ojha AK, Baughn AD, Sambandan D, Hsu T, Trivelli X, Guerardel Y, Alahari A, Kremer L, Jacobs WR, Hatfull GF. 2008. Growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis biofilms containing free mycolic acids and harbouring drug-tolerant bacteria. Mol Microbiol 69:164–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06274.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dubnau E, Chan J, Raynaud C, Mohan VP, Lanéelle MA, Yu K, Quémard A, Smith I, Daffé M. 2000. Oxygenated mycolic acids are necessary for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Mol Microbiol 36:630–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01882.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glickman MS, Cox JS, Jacobs WR. 2000. A novel mycolic acid cyclopropane synthetase is required for cording, persistence, and virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Cell 5:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80250-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhatt A, Kremer L, Dai AZ, Sacchettini JC, Jacobs WR. 2005. Conditional depletion of KasA, a key enzyme of mycolic acid biosynthesis, leads to mycobacterial cell lysis. J Bacteriol 187:7596–7606. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7596-7606.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Léger M, Gavalda S, Guillet V, van der Rest B, Slama N, Montrozier H, Mourey L, Quémard A, Daffé M, Marrakchi H. 2009. The dual function of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis FadD32 required for mycolic acid biosynthesis. Chemistry & Biology 16:510–519. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S, Cai X, Yu W, Zeng S, Zhang J, Guo L, Gao Y, Lu Z, Hameed HMA, Fang C, Tian X, Yusuf B, Chhotaray C, Alam MDS, Zhang B, Ge H, Maslov DA, Cook GM, Peng J, Lin Y, Zhong N, Zhang G, Zhang T. 2022. Arabinosyltransferase C mediates multiple drugs intrinsic resistance by altering cell envelope permeability in Mycobacterium abscessus. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0276321. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02763-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cascioferro A, Boldrin F, Serafini A, Provvedi R, Palù G, Manganelli R. 2010. Xer site-specific recombination, an efficient tool to introduce unmarked deletions into mycobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5312–5316. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00382-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rison SCG, Mattow J, Jungblut PR, Stoker NG. 2007. Experimental determination of translational starts using peptide mass mapping and tandem mass spectrometry within the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology (Reading) 153:521–528. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001537-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foreman M, Gershoni M, Barkan D. 2020. A simplified and efficient method for Himar-1 transposon sequencing in bacteria, demonstrated by creation and analysis of a saturated transposon-mutant library in Mycobacterium abscessus. mSystems 5:e00976-20. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00976-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McAdam RA, Quan S, Smith DA, Bardarov S, Betts JC, Cook FC, Hooker EU, Lewis AP, Woollard P, Everett MJ, Lukey PT, Bancroft GJ, Jacobs WR, Duncan K. 2002. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv transposon library reveals insertions in 351 ORFs and mutants with altered virulence. Microbiology (Reading) 148:2975–2986. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laencina L, Dubois V, Le Moigne V, Viljoen A, Majlessi L, Pritchard J, Bernut A, Piel L, Roux A-L, Gaillard J-L, Lombard B, Loew D, Rubin EJ, Brosch R, Kremer L, Herrmann J-L, Girard-Misguich F. 2018. Identification of genes required for Mycobacterium abscessus growth in vivo with a prominent role of the ESX-4 locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E1002–E1011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1713195115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Laneelle MA, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, Daffe M, Guilhot C. 2001. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J Biol Chem 276:19845–19854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100662200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Siméone R, Léger M, Constant P, Malaga W, Marrakchi H, Daffé M, Guilhot C, Chalut C. 2010. Delineation of the roles of FadD22, FadD26 and FadD29 in the biosynthesis of phthiocerol dimycocerosates and related compounds in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 277:2715–2725. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-464X.2010.07688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barnard A, Wolfe A, Busby S. 2004. Regulation at complex bacterial promoters: how bacteria use different promoter organizations to produce different regulatory outcomes. Curr Opin Microbiol 7:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuan CS, Chan CL, Yew SM, Toh YF, Khoo JS, Chong J, Lee KW, Tan YC, Yee WY, Ngeow YF, Ng KP. 2015. Genome analysis of the first extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Malaysia provides insights into the genetic basis of its biology and drug resistance. PLoS One 10:e0131694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perrodou E, Deshayes C, Muller J, Schaeffer C, Van Dorsselaer A, Ripp R, Poch O, Reyrat J-M, Lecompte O. 2006. ICDS database: interrupted CoDing sequences in prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D338–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deshayes C, Perrodou E, Gallien S, Euphrasie D, Schaeffer C, Van-Dorsselaer A, Poch O, Lecompte O, Reyrat JM. 2007. Interrupted coding sequences in Mycobacterium smegmatis: authentic mutations or sequencing errors? Genome Biol. 8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deshayes C, Perrodou E, Euphrasie D, Frapy E, Poch O, Bifani P, Lecompte O, Reyrat JM. 2008. Detecting the molecular scars of evolution in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex by analyzing interrupted coding sequences. BMC Evol Biol 8:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salamov VS, Solovyevand A. 2011. Automatic annotation of microbial genomes and metagenomic sequences. Metagenomics and its applications in agriculture, biomedicine and environmental studies. 10.5220/0003333703460353. [DOI]

- 31. Portevin D, de Sousa-D’Auria C, Montrozier H, Houssin C, Stella A, Lanéelle M-A, Bardou F, Guilhot C, Daffé M. 2005. The acyl-AMP ligase FadD32 and AccD4-containing acyl-CoA carboxylase are required for the synthesis of mycolic acids and essential for mycobacterial growth: identification of the carboxylation product and determination of the acyl-CoA carboxylase components. J Biol Chem 280:8862–8874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408578200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sirakova TD, Fitzmaurice AM, Kolattukudy P. 2002. Regulation of expression of mas and fadD28, two genes involved in production of dimycocerosyl phthiocerol, a virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 184:6796–6802. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.24.6796-6802.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lynett J, Stokes RW. 2007. Selection of transposon mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with increased macrophage infectivity identifies fadD23 to be involved in sulfolipid production and association with macrophages. Microbiology (Reading) 153:3133–3140. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007864-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Banaei N, Kincaid EZ, Lin S-Y, Desmond E, Jacobs WR, Ernst JD. 2009. Lipoprotein processing is essential for resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to malachite green. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3799–3802. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00647-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Halder S, Yadav KK, Sarkar R, Mukherjee S, Saha P, Haldar S, Karmakar S, Sen T. 2015. Alteration of Zeta potential and membrane permeability in bacteria: a study with cationic agents. Springerplus 4:672. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1476-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Everall I. Evolutionary genomics of cystic fibrosis and nosocomial pathogens of the Mycobacterium abscessus species complex (Doctoral dissertation). https://www.sanger.ac.uk/theses/bryant-thesis.pdf

- 37. Cabruja M, Mondino S, Tsai YT, Lara J, Gramajo H, Gago G. 2017. A conditional mutant of the fatty acid synthase unveils unexpected cross talks in mycobacterial lipid metabolism. Open Biol 7:160277. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beld J, Finzel K, Burkart MD. 2014. Versatility of acyl-acyl carrier protein synthetases. Chem Biol 21:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chhotaray C, Wang S, Tan Y, Ali A, Shehroz M, Fang C, Liu Y, Lu Z, Cai X, Hameed HMA, Islam MM, Surineni G, Tan S, Liu J, Zhang T. 2020. Comparative analysis of whole-genome and methylome profiles of a smooth and a rough Mycobacterium abscessus clinical strain. G3:(Bethesda) 10:13–22. doi: 10.1534/g3.119.400737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Kessel JC, Hatfull GF. 2007. Recombineering in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Methods 4:147–152. doi: 10.1038/nmeth996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bibb LA, Hatfull GF. 2002. Integration and excision of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis prophage-like element, phiRv1. Mol Microbiol 45:1515–1526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tanya P, Stoker NG, eds. 1998. Mycobacteria protocols. Vol. 101. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nie W, Duan H, Huang H, Lu Y, Chu N. 2015. Species identification and clarithromycin susceptibility testing of 278 clinical nontuberculosis mycobacteria isolates. Biomed Res Int 2015:506598. doi: 10.1155/2015/506598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gröblacher B, Kunert O, Bucar F. 2012. Compounds of Alpinia katsumadai as potential efflux inhibitors in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Bioorg Med Chem 20:2701–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rodrigues L, Wagner D, Viveiros M, Sampaio D, Couto I, Vavra M, Kern WV, Amaral L. 2008. Thioridazine and chlorpromazine inhibition of ethidium bromide efflux in Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:1076–1082. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rodrigues L, Ramos J, Couto I, Amaral L, Viveiros M. 2011. Ethidium bromide transport across Mycobacterium smegmatis cell-wall: correlation with antibiotic resistance. BMC Microbiol. 11:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tran HT, Solnier J, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Kunert O, Martin L, Bhakta S, Huynh L, Le TM, Bauer R, Bucar F. 2020. Antimicrobial and efflux pump inhibitory activity of carvotacetones from Sphaeranthus africanus against mycobacteria. Antibiotics (Basel) 9:390. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9070390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]