Abstract

Recent studies showed that the likelihood of drug approval can be predicted with clinical data and structure information of drug using computational approaches. Predicting the likelihood of drug approval can be innovative and of high impact. However, models that leverage clinical data are applicable only in clinical stages, which is not very practical. Prioritizing drug candidates and early-stage decision-making in the de novo drug development process is crucial in pharmaceutical research to optimize resource allocation. For early-stage decision-making, we need a computational model that uses only chemical structures. This seemingly impossible task may utilize the predictive power with multi-modal features including clinical data. In this work, we introduce ChemAP (Chemical structure-based drug Approval Predictor), a novel deep learning scheme for drug approval prediction in the early-stage drug discovery phase. ChemAP aims to enhance the possibility of early-stage decision-making by enriching semantic knowledge to fill in the gap between multi-modal and single-modal chemical spaces through knowledge distillation techniques. This approach facilitates the effective construction of chemical space solely from chemical structure data, guided by multi-modal knowledge related to efficacy, such as clinical trials and patents of drugs. In this study, ChemAP achieved state-of-the-art performance, outperforming both traditional machine learning and deep learning models in drug approval prediction, with AUROC and AUPRC scores of 0.782 and 0.842 respectively on the drug approval benchmark dataset. Additionally, we demonstrated its generalizability by outperforming baseline models on a recent external dataset, which included drugs from the 2023 FDA-approved list and the 2024 clinical trial failure drug list, achieving AUROC and AUPRC scores of 0.694 and 0.851. These results demonstrate that ChemAP is an effective method in predicting drug approval only with chemical structure information of drug so that decision-making can be done at the early stages of drug development process. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first of its kind to show that prediction of drug approval is possible only with structure information of drug by defining the chemical space of approved and unapproved drugs using deep learning technology.

Subject terms: Preclinical research, Drug development, Cheminformatics

Introduction

The process of de novo drug development requires high cost and massive efforts1 (Table 1). Recently, there has been a notable increase in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and other data-driven techniques in computational drug discovery and development. This trend aims to enhance the efficiency of drug discovery processes. Many of these studies focus on predicting new bioactive compounds for specific targets or diseases, assessing the ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion), toxicological properties2–4, and side effects5 of these compounds, and analyzing the structural and functional characteristics of targets. Despite the recent advances in AI technologies, statistics show that only 10% of drug candidates entering Phase 1 clinical trial are approved as drugs6. The factors contributing to this low approval rate are not well characterized as drug approval involves many issues such as toxicity, off-target effects, dosage-related issues, adherence to FDA guidelines, financial constraints, and difficulties in patient recruitment for clinical trials, thereby adding further complexity to the situation. Given the multifaceted nature of drug approval, predicting drug approval during the drug discovery phase, rather than the clinical phase, would provide significant advantages for strategic decision-making in pharmaceutical companies. These benefits include prioritizing investments, selecting promising drug candidates, and mitigating risks associated with clinical trial failures.

Table 1.

Process of drug development, objective, duration, and outcome for each phase.

| Phase | Drug discovery | Pre-clinical | Clinical | Marketing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Target validation, screening, and lead optimization. | Safety, and efficacy in animals | Efficacy, dose, and toxicity in humans | Approval to launch, and monitoring |

| Duration | 35 years | 1 years | 67 years | 12 years |

| Outcome | 250 candidates | 1020 candidates | 2 candidates | 1 drug |

Existing studies on drug approval prediction using computational methods7–11, rely heavily on clinical trial-related features in the model building and inference stages. These features include clinical study design, human subjects, and testing strategies, which are important for understanding how potential drug candidates perform in human subjects and assessing safety, efficacy, and potential side effects. Andrew et al.7 proposed a machine learning model for predicting drug approval with clinical study Phase 2 or Phase 3 results. Kien et al.8 reported that clinical trial-related features are significant in predicting drug approval through Novartis’ data science challenge (DSAI) collaborated with MIT researchers. Recently, an approach has emerged to increase the predictive power of drug approval by incorporating patent information that legally protects compounds into the characteristics of drugs in addition to clinical trial-related features. Fulya et al.9 introduced DrugApp, a machine learning-based model that, for the first time, incorporates patent-related features along with chemical structural, physico-chemical properties, and clinical trial-related features for drug approval prediction.

Recent studies have shown remarkable potential for computational methodologies to predict the likelihood of successful drug development by learning the semantics between drug approval and multi-modality features such as chemical structure, physico-chemical property, bioactivity, clinical trials, and patents of drug. Nonetheless, the current methodology encounters hurdles when attempting to predict drug approval during the drug discovery phase due to the absence of comprehensive data like clinical trials, and patent information (Table 2). Addressing this challenge calls for computational approaches capable of predicting approval using accessible information during drug discovery. In this context, John et al.12 introduced a machine learning-based methods that predicts the likelihood of clinical success of a drug based on the chemical structural and physico-chemical properties.

Table 2.

Data accessibility of multi-modalities in drug. The number of check marks indicates data accessibility in each phase.

| Data type | Drug discovery phase | Clinical trial phase |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical structure | ||

| Physico-chemical property | ||

| Clinical trial-related | – | |

| Patent-related |

Current drug approval prediction studies encounter a significant challenge: the inclusion of multi-modal features and their semantic information to enhance predictive accuracy comes at the cost of poor usability in the drug discovery process. To improve the usability, drug approval prediction should be done only with chemical structure information. However, chemical structure information does not convey information rich enough to make drug approval prediction at the satisfactory level. Thus, there should be a way to transfer relevant information to a drug approval prediction model only in terms of chemical space configuration. Our study is to show that such knowledge transfer is feasible in terms of chemical space configuration in a transfer learning architecture of a teacher and a student models.

In this context, deep learning, coupled with knowledge distillation (KD), emerges as a promising approach to address this limitation. Deep learning offers a potent algorithm for encoding the intricate knowledge into embedding spaces, while KD facilitates the transfer of semantic insights across models. Leveraging these techniques, we propose ChemAP (Chemical structure-based drug Approval Predictor), a novel deep learning framework designed for predicting drug approval based solely on chemical structure. ChemAP operates in two distinct phases: first, ChemAP constructs a multi-modal embedding space encapsulating key semantic information for drug approval prediction from chemical structure, physico-chemical properties, clinical trial-related features, and patent-related features. Subsequently, employing KD, ChemAP distills invaluable insights from this multi-modal embedding space into a single modal embedding space, focusing solely on chemical structure information. This innovative approach empowers ChemAP to predict drug approval outcomes in drug discovery phase with enhanced accuracy, leveraging the wealth of multi-modal data while retaining usability. Notably, ChemAP demonstrates state-of-the-art performance compared to existing methodologies, as evidenced by rigorous evaluation against the 2023 FDA-approved and the 2024 clinically failed drugs. By bridging the semantic knowledge gap and offering a potent tool for early-stage decision-making, ChemAP heralds a paradigm shift in drug development strategies.

Results

ChemAP generates multi-modal and single-modal embedding spaces in two-step process

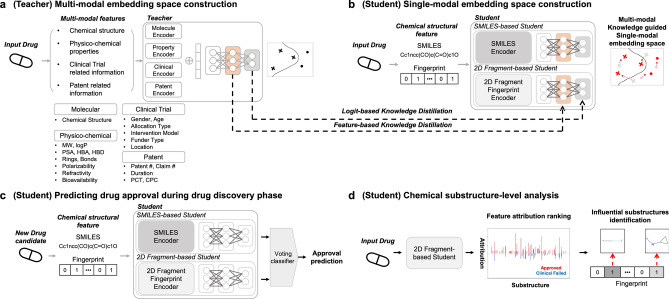

The purpose of ChemAP is to create a chemical space that satisfies semantic knowledge and usability for drug approval. To achieve this goal, ChemAP framework uses a teacher-student learning paradigm in KD. Below, we summarized the two-step process employed by ChemAP framework, illustrated in Fig. 1. Further technical details on the methodologies utilized within ChemAP are elaborated upon in the Methods Section.

The first step of ChemAP is generating a multi-modal embedding space using four types of drug data: chemical structure, physico-chemical properties, clinical trials, and patent features. Through the first step, the teacher model captures invaluable semantic knowledge across multi-modal data and generates an embedding space adapted to drug approval prediction (Fig. 1a).

In the second step, a single-modal embedding space is constructed by using chemical structure information but also learning the semantic knowledge in the teacher’s multi-modal embedding space. During training, the student model of ChemAP reflects this semantic knowledge through knowledge distillation. This student model includes two predictors, each capturing drug chemical structure information from different perspectives. Throughout the training process, the embedding space of each predictor is refined to improve drug approval prediction (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1c illustrates how ChemAP predicts drug approval using only chemical structure information during the drug discovery stage. The final approval probability is determined by ensembling the predicted probabilities of the two predictors of the student model depicted in Fig. 1b using a soft voting method. In the practical use of ChemAP, only chemical structure information is used to predict approval, but the process of forming the embedding space for each predictor was guided through the teacher embedding space. Therefore, the prediction results by the student model reflect semantic knowledge across the chemical structure, physico-chemical properties, clinical trials, and patent features for drug approval. Additionally, ChemAP provides chemical substructure-level interpretation through 2D fragment-based predictive analysis (Fig. 1d). This analysis provides key chemical structural insights for drug approval and unapproval.

Figure 1.

The overview of the ChemAP framework. a The multi-modal embedding space construction. The teacher model of ChemAP generates multi-modal embedding space by capturing the contextual information of drug approval inherent in multi-modal data such as molecular features, physico-chemical features, clinical trial features, and patent features. b Single-modal embedding space construction. The student model of ChemAP generates single-modal embedding space through knowledge distillation technique. Preformed multi-modal embedding space transfers semantic information across multi-modal data and refines the single-modal embedding space. c Drug approval prediction in the drug discovery phase. With ChemAP’s student model, the likelihood of drug approval can be predicted using only chemical structure information during the actual drug discovery stage. d Chemical substructure-level analysis. By analyzing the attributions of individual 2D chemical substructures, we reveal the interpretability of ChemAP’s predictions in relation to chemical structure.

ChemAP enables accurate prediction of drug approval solely on chemical structure

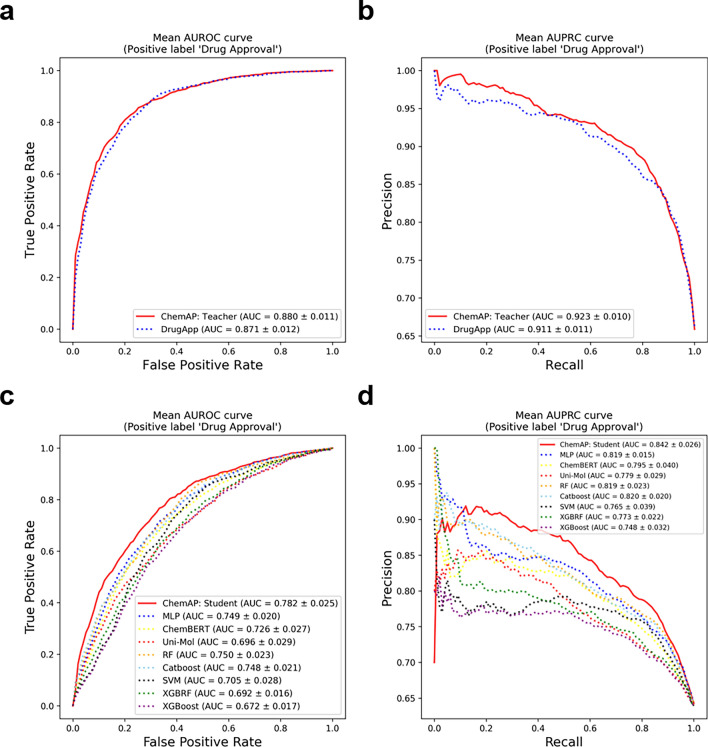

We evaluated both the teacher model and the student model on the drug approval benchmark dataset. Although the good performance of the student model is ultimate goal, the student model will perform better when learning from a more accurate teacher model. Thus, we first evaluated the drug approval prediction performance of the teacher of ChemAP, a multi-modal deep learning-based drug approval prediction model. The prediction performances were measured by two metrics: area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and area under precision-recall curve (AUPRC). The selected comparison model is a DrugApp9, a state-of-the-art (SOTA) drug approval prediction model that utilizes multi-modal information. Through 10 repeated experiments, Fig. 2a and b show that the teacher model of ChemAP achieved an average AUROC of 0.880 and an average AUPRC of 0.923, and DrugApp tested under the same conditions showed an average AUROC of 0.871 and an average AUPRC of 0.911. These results indicate that the ChemAP teacher model has superior predictive power compared to DrugApp.

Figure 2.

The drug approval prediction performances of each model with multi-modal and single-modal data. a, b AUROC and AUPRC for drug approval prediction by ChemAP’s teacher model (solid line) and DrugApp (dashed line). Both models were trained with molecular features, physico-chemical features, clinical trial features, and patent features. c, d AUROC and AUPRC for drug approval prediction by ChemAP’s student model and baseline models. ChemAP’s student model (solid line) and eight baseline models (dashed line) were trained only with chemical structural features. (AUROC; Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics Curve, AUPRC; Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve).

Next, we evaluate a student model of ChemAP that predicts drug approval based on chemical structure alone. Prediction performances were also measured by the two metrics: AUROC, and AUPRC. Due to the absence of existing studies using deep learning techniques to predict drug approval based on chemical structure information, selecting a suitable deep learning-based comparison model was challenging. We chose ChemBERT13, Uni-Mol14, and MLP as baseline models for this task. These models are designed for learning chemical structure representation using various types of chemical data, such as Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES), Morgan fingerprint, and 3D geometric features, and they have shown strong performance in downstream tasks like chemical property prediction.

ChemBERT is a natural language processing-based model that learns chemical structures at the atom and bond level using the SMILES representation of molecules and self-attention mechanisms. Uni-Mol, on the other hand, is a framework that employs a specialized neural network architecture, the SE(3) Transformer, designed to learn representations of molecules with 3D conformations. In contrast, MLP learns chemical structure information from 2D fragment data represented by molecular fingerprints. Additionally, a comparative experiment was conducted between the latest transformer-based methods, including MolCLR15, MoLFormer16, and MAT17, and graph-based approaches such as Graph Transformer18 and GraphMVP19.

The results for the random drug split setting are presented in Fig. 2c and d, as well as in Table S1. ChemAP outperformed all comparative models across all metrics, with average AUROC and AUPRC values of 0.782 and 0.842, respectively. Among the baseline models, Random Forest (RF) achieved the second-best overall performance and the highest performance among traditional machine learning models. MLP ranked third overall and second among deep learning-based models, following ChemAP. A detailed analysis of Fig. 2d shows that ChemAP’s precision-recall curve exhibits lower precision around a recall of 0.0 compared to other models. This is because ChemAP predicted Goserelin as “approved” with a high probability, but this drug is labelled as “unapproved” in the benchmark dataset. Goserelin is a synthetic hormone that inhibits hormone production in the body. Although it is labeled as a clinical trial failure in the dataset, Goserelin is actually an approved and widely used medication. While it is approved, Goserelin has shown clinical failures in some trials (e.g., NCT02168062 and NCT00217659) for prostate and breast cancer. Thus, ChemAP can be considered to have accurately predicted the approval of Goserelin. As of now, for the fair comparison with existing tools, we stick to the widely benchmark data set as is for performance comparison. Even under the scaffold split setting, ChemAP maintained the top performance across all metrics, with average AUROC and AUPRC values of 0.702 and 0.791, respectively (Table S2).

Enhancing drug approval prediction based solely on chemical structure through semantic knowledge transfer within a multi-modal embedding space

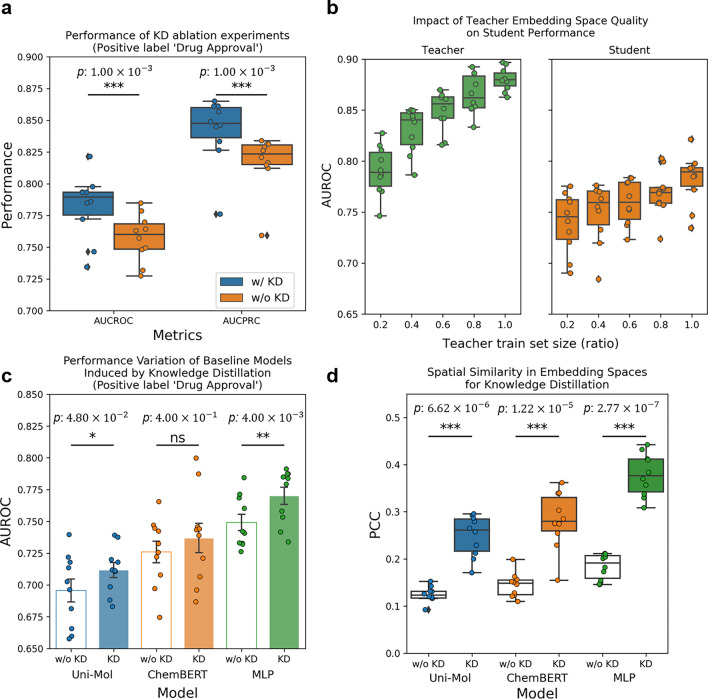

To evaluate the impact of semantic knowledge transfer through knowledge distillation (KD) on the predictive power of the ChemAP student model and its single-modal embedding space, we conducted an ablation experiment. As shown in Fig. 3a, the student model trained solely on chemical structures without KD exhibited a significant reduction in both AUROC and AUPRC metrics. A paired t-test confirmed the statistical significance of this decrease. These findings demonstrate that semantic knowledge extracted from the multi-modal embedding space of the teacher model can enrich the single-modal embedding space of the student model, thereby enhancing drug approval prediction based solely on drug structure.

Figure 3.

Ablation analysis of the knowledge distillation effect. a Performance of knowledge distillation (KD) ablation experiments. The blue boxes represent AUC without KD and the orange boxes represent AUC with KD. b Impact of teacher embedding space quality on student performance. The green boxes in the left panel represent the change in AUROC relative to the training data size of the teacher model. The orange boxes in the right panel show the AUROC of the student model, which distills knowledge from the teacher model trained on different proportions of the training data. c Performance variation of baseline models induced by KD. Empty bars represent baseline models trained without KD, while filled bars represent baseline models trained with KD. d Spatial similarity in embedding spaces for knowledge distillation. The box plot illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) of the relative distance distribution of data points in the embedding space between each reference model and ChemAP’s teacher model. Models trained without KD are represented by white boxes, while models trained with KD are depicted in colored boxes. Statistical significance was verified through paired t-test. *: p, **: p, ***: p.

We investigated the impact of semantic knowledge quality on the predictive capability of the student model. To explore this, we varied the amount of data used to train the teacher model, creating sparser and lower-quality embedding spaces. As the training data decreased, the teacher model acquired less semantic information about drug approval, leading to a decline in the quality of its multi-modal embeddings. Fig. 3b, left panel, shows that the teacher model’s drug approval prediction performance declines with reduced training data, while the right panel illustrates the improvement in the student model’s performance as the quality of transferred knowledge increases. Our findings indicate that as the teacher model’s embedding space quality improves with more training data, the student model’s performance, which inherits this semantic knowledge, also improves (Fig. 3b).

Next, we explored whether implicit semantic knowledge in a multi-modal embedding space can enhance the performance of deep learning-based models. We applied KD to the baseline deep learning models: ChemBERT, Uni-Mol, and MLP. As shown in Fig. 3c, applying KD improved the performance of each model. Statistically significant performance improvements were observed for Uni-Mol and MLP, but not for ChemBERT. Additionally, we examined how receiving semantic knowledge from the teacher model affects the formation of the embedding space by spatial similarity analysis. The results in Fig. 3d show that the distribution of latent representations for test set data points in each baseline model became more similar to the teacher model’s embedding space when semantic knowledge was delivered through KD. Specifically, compared to the results in Fig. 3c, it was confirmed that a closer resemblance to the teacher model’s embedding space corresponds to higher predictive power. Therefore, transferring semantic knowledge in a multi-modal embedding space through KD guides the formation of an embedding space for approved drugs in a model-agnostic manner.

We visualized how the embedding space formed with KD more accurately represents chemical structure similarity, using the example of an approved drug that exhibits structural similarity. Fig. 4a summarizes an example of three approved drugs: Dexamethasone (denoted as (a)), Triamcinolone (denoted as (b)), and Prednisolone (denoted as (c)). These drugs belong to the synthetic glucocorticoids class, a group of corticosteroid hormones that mimic the effects of cortisol. Indeed, the three drugs are structurally similar based on the Jaccard index between Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs), with a minimum of 0.337 (Fig. 4a). In Fig. 4b, where the embedding space is visualized using PCA, it is evident that without KD, the three drugs in the example are dispersed across different regions despite their structural similarities. However, with the incorporation of semantic knowledge through KD, all three drugs in the example are closely clustered within the approved drug space within the embedding. The table in Fig. 4c shows that the cosine similarity of latent representations between each drug increased from -0.252 to 0.602, -0.637 to 0.804, and -0.186 to 0.794, respectively, with KD. Additionally, in Fig. 4d, the actual drug status of each case, its predicted probability value, and the prediction results from both the model without and with KD are presented. Despite substantial chemical structural similarities among the three drugs (a), (b), and (c), the chemical structure-based model without KD misclassifies drug (a) as ‘Unapproved’ and predicts drug (c) as ‘Approved’ with a low probability (0.550). Conversely, in the KD-enhanced model, drugs (a), (b), and (c) are predicted as ‘Approved’ with high probability values of 0.717, 0.968, and 0.933, respectively.

Figure 4.

Knowledge Distillation case study. a Summary of drug cases. Each drug analyzed and visualized is denoted as (a), (b), and (c), respectively. Summary table includes name of drugs, chemical structures, descriptions, and pairwise chemical similarity between cases computed with Jaccard index. b Embedding space visualization. Visualizing the distribution of approved drugs (gray) and case drugs (red) in each embedding space for a model trained without knowledge distillation (top panel) and a model trained with knowledge distillation (bottom panel). c The similarity analysis of latent representation. For each case, latent representations were extracted from the model trained without knowledge distillation and the model trained with knowledge distillation, and the cosine similarity between them was calculated. d Prediction outcomes of case drugs. The table shows the actual approval status of each case alongside the predicted status and probability value from each model. Cases with incorrect predictions are highlighted in red.

Comparative assessment of substructure recognition for drug approval prediction

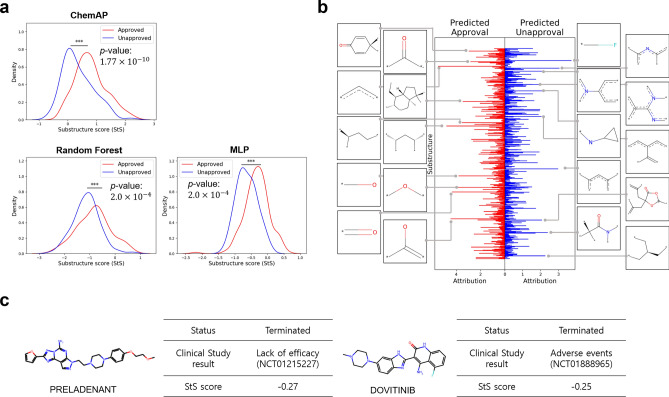

To gain further insight into how ChemAP achieves its promising prediction performance for drug approval, we examined the specific chemical substructures that the model predominantly considers when predicting both approval and disapproval of drugs. To do this, we quantified the substructure-level attribution within the ECFPs of chemical structures. We extracted the top 300 substructures with high attribution for decision-making from ChemAP. Subsequently, these extracted chemical substructures were used as features to calculate the substructure score (StS; detailed in the Methods Section ‘Substructural attribution analysis’) for each drug in the test dataset. A higher StS score indicates the presence of more crucial substructures relevant to predicting approval, whereas lower scores indicate the prominence of substructures pertinent to predicting unapproval. Additionally, we assessed the efficiency of the previously extracted substructures by conducting a t-test to determine whether the distribution of StS scores for approved and unapproved drugs was statistically significantly different. The evaluation was conducted and compared not only on ChemAP but also on the RF model that exhibited the top performance among machine learning models and the MLP model that demonstrated the the second best performance among deep learning models after ChemAP.

As depicted in Fig. 5a, the chemical substructures extracted from ChemAP exhibited the most significant differentiation between approval and unapproval compared to those considered by the RF and MLP models (p-value of ChemAP: , p-value of RF: , and p-value of MLP: ). Fig. 5b illustrates the distinct substructures involved in the prediction for each drug class, with the top 10 highly attributed substructures visualized. Among these, the substructure with the highest attribution to unapproval prediction was identified as the fluorine-containing substructure (*-F), recognized for its potential toxicity and metabolic effects20. Additionally, four nitrogen-substituted aromatic substructures were identified, commonly employed in medicinal chemistry despite potential toxicity concerns21. In Fig. 5c, drugs such as Preladenant and Dovitinib with low StS scores are depicted, correlating with documented clinical study findings on ClinicalTrials.gov. Specifically, Preladenant trials (NCT0121522722 and NCT0122726523) were terminated due to insufficient efficacy, while a Dovitinib study (NCT0188896524) was halted due to adverse events. In summary, ChemAP effectively identified substructures associated with both approved and unapproved drugs more accurately than the baseline models, potentially leading to improved performance.

Figure 5.

Substructure-level attribution and distribution analysis. a StS score distribution in each model. The density plot shows the distribution of StS scores for approved (red) and unapproved (blue) drugs in the test dataset calculated using the feature information each model learned to predict drug approval. b Visualization of ChemAP’s attribution values for predicting approved (red) and unapproved (blue) drugs for each bit position in the ECFP4 (2048 bits). The substructure of the top 10 attribution values of each class was visualized. c Cases with low StS scores. The table shows structural information, name, status, clinical study ID, and a concise summary of study results, in addition to the StS score calculated by ChemAP for PRELADENANT and DOVITINIB. Statistical significance was verified through t-test. ***: p.

External validation with the FDA-approved drugs and Clinical trial failed drugs

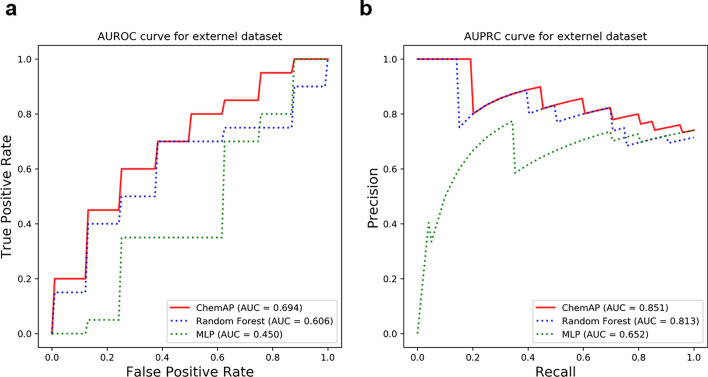

To further support the utility and generalizability of ChemAP, we performed additional evaluation with external dataset retrieved from FDA and Clinical trials.gov database25: The 2023 FDA-approved drugs list and the clinical trial failed in 2024. To ensure a fair evaluation, we compared the prediction performances of the MLP and RF models that demonstrated a high AUROC on the benchmark dataset (0.749±0.020 and 0.750±0.023, respectively) (Fig. 2c and d).

Figure 6 illustrates that ChemAP outperformed MLP and RF on the external dataset, achieving AUROC and AUPRC values of 0.694 and 0.851, respectively. Table 3 presents the actual drug status and predicted label by ChemAP for each drug in the external dataset. ChemAP accurately predicted 11 out of 20 FDA-approved drugs (55% accuracy) and 6 out of 8 clinical trial failed drugs (75% accuracy). Notably, it demonstrated significant predictive power for drugs that failed clinical trials. Although the performance of all models declined compared to results from experiments with the benchmark dataset, we showcased ChemAP’s generalizable capacity even for the latest unseen drugs. This promising result suggests that ChemAP’s knowledge distillation-based drug approval prediction method might be practically applicable in the drug discovery phase.

Figure 6.

The drug approval prediction performances for the external dataset. a, b AUROC and AUPRC for the external dataset. ChemAP’s student model (solid line) and baseline models (dashed line) were trained with train dataset and evaluated with the external dataset.

Table 3.

Evaluation of ChemAP’s approval prediction performance using drugs listed in an external dataset. ‘A’ denotes an ‘Approval’ and ‘U’ denotes an ‘Unapproval’.

| Name | Status | FDA-approved use or reason for clinical failure | ChemAP prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ogsiveo | A | Adults with progressing desmoid tumors who require systemic treatment. | A |

| Agamree | A | To treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy. | A |

| Velsipity | A | Moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in adults. | A |

| Exxua | A | To treat major depressive disorder. | A |

| Litfulo | A | Severe alopecia areata in both adults and adolescents as young as 12. | A |

| Miebo | A | Signs and symptoms of dry eye disease. | A |

| Veozah | A | Moderate to severe hot flashes caused by menopause. | A |

| Daybue | A | To treat Rett syndrome. | A |

| Zavzpret | A | To treat migraine. | A |

| Filspari | A | Proteinuria in adults with primary immunoglobulin A nephropathy at risk of rapid disease progression. | A |

| Orserdu | A | ER-positive, HER2-negative, ESR1-mutated, advanced/metastatic breast cancer with disease progression following at least one line of endocrine therapy. | A |

| Fabhalta | A | To treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. | U |

| Truqap | A | Breast cancer that meets certain disease criteria. | U |

| Augtyro | A | ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer. | U |

| Vanflyta | A | Regimen for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia that meets criteria. | U |

| Posluma | A | Positron emission tomography imaging in patients with prostate cancer. | U |

| Paxlovid | A | Mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adults at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19. | U |

| Joenja | A | Activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta syndrome. | U |

| Skyclarys | A | To treat Friedrich’s ataxia. | U |

| Jaypirca | A | Relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma in adults who have had at least two lines of systemic therapy, including a BTK inhibitor. | U |

| Lufotrelvir | U | Clinical failure due to adverse events (NCT05780541). | U |

| Zandelisib | U | Clinical failure due to adverse events (NCT03768505). | U |

| Alpelisib | U | Clinical failure due to adverse events (NCT03601507). | U |

| AMG 337 | U | Clinical failure due to lack of efficacy (NCT03132155). | U |

| Evobrutinib | U | Clinical failure due to lack of efficacy (NCT02975349). | U |

| Linperlisib | U | Clinical failure due to lack of efficacy (NCT05676697). | U |

| H3B-8800 | U | Clinical failure due to lack of efficacy (NCT02841540). | A |

| Gamcemetinib | U | Clinical failure due to lack of efficacy (NCT04947579). | A |

Discussion

We developed a novel deep learning framework called ChemAP, designed to improve the drug approval likelihood prediction with enhanced usability. The ultimate design goal of ChemAP is to make prediction about the likeliness of approval only with chemical structure information. Our approach addresses the limitations of existing drug approval prediction studies, particularly their poor applicability requiring clinical feature data which is not available at the early stage of drug discovery. However, this is a challenging task that can hardly be achieved without additional information including clinical trial features. Thus, ChemAP is designed as a teacher-student architecture where chemical space of molecular features can be configured with physico-chemical features, clinical features and patent features. Then, the chemical space configuration learned by the teacher model is used to guide the shaping of chemical space configuration by the student model. In other words, the student model tries to shape its own chemical space configuration that is similar to the chemical space configuration learned by the teacher model. In the end, prediction of drug approval is made by the student model only with chemical structure information.

ChemAP is the first of its kind to predict the likelihood of drug approval solely with chemical structure information. ChemAP achieves state-of-the-art prediction performance on the drug approval benchmark dataset, and also on the latest external dataset. ChemAP’s success is largely attributed to its innovative use of knowledge distillation, which transfers relevant information to the drug approval prediction model by focusing on chemical space configuration. Our ablation study confirms that transferring semantic information is crucial for ChemAP’s improved performance. For instance, the case of glucocorticoid drugs demonstrates how ChemAP integrates multi-modal semantic knowledge into a single-modal embedding space, refining single-modal predictors to more accurately capture structural similarities.

Moreover, we demonstrate that ChemAP more effectively captures chemical substructures associated with both drug approval and unapproval compared to baseline models. Specifically, chemical substructures known to be potentially toxic, such as fluorine-containing and nitrogen-substituted aromatic substructures, exhibit high attribution to approval predictions. Fluorine, for instance, can act as a leaving group in chemical reactions, but doses exceeding 10 mg per day can lead to health risks, including dental and skeletal fluorosis as well as gastrointestinal complications20. Additionally, certain fluorinated compounds, like fluoroacetic acid, can disrupt metabolic processes such as the Krebs cycle by reacting with acetyl coenzyme A and entering the pathway21. Furthermore, among the substructures showing significant attribution for unapproved drugs, four nitrogen-substituted aromatic substructures were identified. Nitrogen-containing aromatic rings, or heteroaromatic rings, are prevalent in medicinal chemistry and drug design, offering unique properties contributing to drug efficacy. However, it is essential to acknowledge potential toxicity associated with these moieties, including metabolic activation, genotoxicity, and off-target interactions26,27. Additionally, nitrogen-containing aromatic rings may undergo metabolic transformations, such as oxidation or reduction, influencing the compound’s pharmacokinetic properties and toxicity profile.

However, ChemAP’s current drug approval prediction framework may have some limitations. The primary concern is the comparatively lower predictive power of the student model in contrast to the teacher model within ChemAP. Addressing this issue requires the development of more robust knowledge distillation methods tailored to the chemical domain. While advancements in knowledge distillation techniques have been notable in image and audio domains, it is essential to devise methodologies specifically attuned to chemistry. We intend to create a comprehensive multi-perspective framework for more precise drug approval prediction with dependable decision boundaries in forthcoming research endeavors.

In summary, our findings highlight the applicability of a chemical structure-based framework for predicting drug approval in practical drug development processes, further augmented through multi-modal semantic knowledge transfer. Our work illustrates how integrating multi-modal drug information, including insights from clinical trials, can effectively guide decision-making in early-stage drug development. Furthermore, our research offers insights into chemical structure indicators linked to clinical failures, thereby aiding in the identification of compounds that pass pre-clinical evaluation but stumble during clinical trials.

Methods

Data preparation

To evaluate the predictive power of ChemAP and baseline models for drug approvals, we used a drug approval benchmark dataset, along with an external dataset that includes the 2023 FDA-approved drug list and the 2024 clinical trial failed drug list.

Benchmark dataset

The benchmark dataset of approved and unapproved drugs, initially introduced in the previous study, DrugApp9. The benchmark dataset contains 1,995 approved drugs and 1,127 unapproved drugs from DrugBank28 and ClinicalTrials.gov25 databases. The unapproved drugs are selected from clinical trial records with ‘suspended’, ‘terminated’, or ‘withdrawn’ outcomes. Molecular features, physico-chemical features, clinical trial-related features, and patent-related features are collected as follows:

ClinicalTrials.gov25: The largest database containing clinical trial study information.

DrugBank28: A database containing information on the molecular and pharmacological aspects of drugs.

ChEMBL29: A bioactivity database that focuses on the chemical compounds and their associated biological activities for drug discovery and pharmacological research.

SureChEMBL30: A freely accessible resource that extracts and curates chemical patent information.

PatentsView31: A comprehensive database that providing users with insights into patent information.

The vectorization for physico-chemical features, clinical trial-related features, and patent-related features was done with the same process as introduced in DrugApp9. For the chemical structure, a 128-dimensional ECFP4 binary vector was utilized for training both DrugApp and the teacher model of ChemAP, while a 2048-dimensional ECFP4 binary vector was utilized for training the 2D fragment-based student model. The RDKit32 package was used to convert the chemical structures to ECFP4 binary vector. During preprocessing, we excluded compounds with SMILES sequences of over 256 in length to fit our model. The final processed dataset contains 1,941 approved drugs and 1,100 unapproved drugs, total 3,041 unique drugs.

To rigorously evaluate predictive performance, we employ two methods to split the benchmark dataset: random drug split and scaffold split. In a random drug split, the dataset is divided into training, validation and testing subsets by randomly selecting drugs from the entire dataset. Each drug has an equal chance of being placed in either the training, validation or testing set, regardless of its chemical structure or properties. In a scaffold split, the dataset is divided based on the chemical scaffolds, which are the core structures or backbones of the molecules. For both splitting methods, the dataset is further divided into training, validation, and testing subsets with a ratio of 8:1:1.

External dataset

To demonstrate the performance of ChemAP in predicting drug approval for unseen drugs, we constructed an additional external dataset. We collected 28 small molecule drugs from the 2023 FDA-approved drug list (accessed on January 17, 2024) and 12 small molecule drugs from ClinicalTrials.gov25 (accessed on May 31, 2024). From ClinicalTrials.gov, we gathered small molecule drugs reported as terminated, suspended, or withdrawn between January 1, 2024, and May 31, 2024, focusing on those with reported adverse events or lack of efficacy. The structural information for each drug was sourced from the PubChem database33. To ensure a rigorous evaluation of generalizability, we excluded drugs with structural similarities to those used in the ChemAP training set, defined by a Jaccard index of ECFPs above 0.7. Consequently, 28 drugs remained for the final evaluation.

Model development

In this section, we introduce the details of the proposed method. The key idea of ChemAP is employing a knowledge distillation from a teacher model based on multi-modality to refine a student model based on chemical structure. This method aims to guide the chemical structure based latent space to emulate the characteristics of the multi-modality-based latent space. The overview of the ChemAP is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Multi-modal teacher network

The teacher model learns the multi-modality features of the drug to form a comprehensive latent space, and then transfers latent space and probabilistic decisions about the drug to the student model in the form of knowledge learned by the teacher. Structurally, the teacher model consists of three main parts. The first part is an individual encoder for each modality feature, the second part is a projection layer that integrates each modality latent space, and the last part is a classifier that performs binary classification of drug approval. Formally, given a drug , where i is an index of drug. cs, ct, pc, and pt denote chemical structure, physico-chemical property, clinical trial-related, and patent-related features, respectively.

We first implemented modal-specific encoders to generate latent representations , .

| 1 |

where is a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) based encoder.

Next, we implemented a MLP-based projection layer, which combines the latent representations from each modality into a refined representation , effectively combining multi-modal information for the drug.

| 2 |

where is a concatenation operator. is a MLP-based projection layer.

Then, we implemented a MLP-based classifier that produces log-odds (logit) for each drug, allowing us to convert these log-odds into probabilities indicating the likelihood of approval.

| 3 |

where is a MLP-based classifier, denotes the logit of i-th drug produces from the teacher classifier.

Chemical structure-based student network

Chemical structure-based student network is a key part that allows ChemAP to predict drug approval solely based on the chemical structure of a drug candidate at the inference step. Structurally, student network consist of two predictors, and each predictor adopts the form of a molecular encoder-classifier.

| 4 |

| 5 |

where denotes the molecular encoder, denotes the latent representation of i-th drug from the molecular encoder within the student model, denotes the classifier, and denotes the logit of i-th drug produces from student classifier.

To explain the student in more detail, one of the two predictors is the SMILES-based predictor, denoted as Smi, while the other predictor is the 2D fragment-based predictor, denoted as Frag. The SMILES-based predictor is a large language model specifically designed to handle SMILES string for the field of chemistry. In this study, we applied ChemBERT13, which is pre-trained on a massive chemical dataset, as a molecular encoder of SMILES-based predictor. The 2D fragment-based predictor is an MLP-based model utilizing ECFP, providing insights into relationships between 2D structure and drug approval. The classifiers within each model are all MLP-based classifiers, denoted as .

Knowledge distillation

Knowledge distillation is a method of knowledge transfer from a larger model (teacher) to a smaller model (student), encouraging the student to match the behavior of the teacher. This approach is also adapted for the specific challenges posed by multi-modal data. Existing studies34–36 applied knowledge distillation in the context of transitioning from a multi-modal model to a uni-modal model.

Hinton et al.37 proposed a weighted combination of two objectives as a logit-based knowledge distillation method , where .

| 6 |

| 7 |

is the supervised cross-entropy between the student logits and the ground truth labels y. is the knowledge distillation term that promotes the student to match the final output probabilities with those of the teacher. It presents the cross-entropy between the scaled predictive distribution of the teacher and the student and , where the is a temperature constant for logits.

Romero et al.38 proposed a feature-based knowledge distillation approach, incorporating ‘hints’ in the form of intermediate representation activations from the hidden layers of the teacher. The suggested objective is . term, aligns intermediate representations from the student to the teacher. While the term serves as a regularization loss, preventing overfitting.

| 8 |

where denotes the latent representation at layer j of the teacher, denotes the latent representation at layer j of the student.

The fundamental problem is how to transfer knowledge of teacher trained by multi-modality of drugs to a student model that uses the chemical structure information only. Drug , Label , set of multi-modality features for i-th drug . Teacher model and . Meanwhile, Student model . where T denotes teacher model and S denotes student model, and are model parameters, cs denotes chemical structure features, pc denotes physico-chemical property-features, ct denotes clinical trial-related features, and pt denotes patent-related features.

Learning objective

We designed the multi-level knowledge distillation objective to transfer knowledge of the teacher trained by multi-modality of drugs to a chemical structure-based student model. During training the student, multi-modality information of drugs implicitly utilizes through knowledge transfer from the pre-trained teacher. In pre-training the multi-modality teacher model, only the cross-entropy objective was utilized.

| 9 |

To train the student model, a multi-level knowledge distillation objective was employed, a combination of logit-based knowledge distillation and feature-based knowledge distillation which are depicted in Eqs. 7 and 8, respectively. The final objective function is a weighted combination of three objective terms depicted in Eqs. 6, 7, and 8.

| 10 |

where , , and are hyperparameters controlling the relative importance of each loss term.

In Eq. 10, and are knowledge distillation terms that encourage the chemical structure-based student logits and latent representations to match logits and latent representations from the multi-modality teacher.

Ensemble learning

To enhance the performance of drug approval prediction, we employed an ensemble technique, a general method that aggregates predictions from multiple base models by calculating the average of the probability outputs.

| 11 |

where Smi denotes the SMILES-based student model, and Frag denotes the 2D Fragment-based student model.

Baseline models

For a fair and comprehensive evaluation, we compared ChemAP to five traditional machine learning algorithms previously used in drug approval prediction studies8,9,12: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, XGBRF, CatBoost, and Support Vector Machine (SVM), along with three deep learning-based models that show good performance in predicting chemical compound properties: ChemBERT13, Uni-Mol14, and MLP. Random Forest is an ensemble learning algorithm by building multiple decision trees. XGBoost is a gradient boosting ensemble learning algorithm by building multiple decision trees and refining the model by correcting errors of the previous trees. In the DSAI challenge8, XGBoost achieved a top performance for predicting drug approval. XGBRF is an ensemble model merging XGBoost and RF. CatBoost is a gradient boosting principle based machine learning algorithm that specializes in handling categorical data. SVM is a supervised machine learning algorithm primarily used to find a hyperplane that best separates different classes in the feature space. ChemBERT is a large-scale language model specifically trained for the field of chemistry and is a representation learning method that learns chemical structures at the atom and bond level. Uni-Mol is a deep learning-based framework for drug design. It tackles 3D structures of molecules, learning to represent them effectively, and ultimately aiming to improve drug discovery. MLP, a type of artificial neural network consisting of multiple layers and non-linear activation functions, offers a solid baseline for developing more complex models.

In our study, we adopted the hyperparameters of each baseline model as proposed in previous researches. For instance, RF utilized the hyperparameters suggested by Fulya et al.9, while XGBoost, XGBRF, CatBoost, and SVM were trained using the hyperparameters outlined in the study by John et al.12. In contrast, the three deep learning models, ChemBERT, Uni-Mol, and MLP, had not been previously explored in the drug approval prediction task. ChemBERT was fine-tuned from pre-trained model weights to adapt to the drug approval prediction task. For Uni-Mol training, we froze the pre-trained weights and trained only the classifier to adapt to the drug approval prediction task. Meanwhile, the MLP model, sharing the same architecture as ChemAP’s 2D fragment-based predictor, was trained from scratch. The RF and SVM models were implemented using the scikit-learn Python open-source library39, XGBoost and XGBRF using the XGBoost Python open-source library40, and CatBoost using the CatBoost Python open-source library41. ChemBERT, Uni-Mol, and MLP were implemented using the PyTorch package in Python42.

Model training and evaluation

Training ChemAP consists of two stages. The first step is the process of learning a multi-modal embedding space that can predict drug approval through information on the four modalities of the drug (chemical structure, physico-chemical properties, clinical trials-related, and patent-related feature). In this process, the teacher model was trained through 500 epochs and the AdamW optimizer was used. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01, and before 300 epochs, the learning rate was adjusted by the cosine scheduler, and after 300 epochs, the stochastic weight averaging technique was used as the learning rate scheduler. Batch size was set to 256.

In the second step, ChemAP’s student model is trained. At this time, the two predictors that make up ChemAP, a SMILES-based predictor and a 2D fragment-based predictor, are trained separately. The first predictor, SMILES-based predictor, was fine-tuned through 100 epoch iterations and AdamW optimizer based on pretrained ChemBERT. Additionally, the , , , and of the objective function of the SMILES-based predictor were set to 1.04, 0.69, 1.34, and 2, respectively, and the initial learning rate was set to . The second predictor, a 2D fragment-based predictor, updated the xavier initialized weights through iteration of the 2000 epoch and the AdamW optimizer. The , , , and of the objective function of the 2D fragment-based predictor were set to 0.33, 2.21, 1.21, and 10, respectively, and the initial learning rate was set to . Batch size of both predictors are fixed to 128. Each hyperparameter of ChemAP was optimized based on its performance on the validation set via the optuna framework43.

To evaluate the performance of ChemAP and baseline models, we utilized two metrics such as area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC).

Spatial similarity analysis

To compare the similarity between embedding spaces in different models, we examined the distribution of relative distances of data points within each model’s embedding space. Initially, we computed these relative distances using cosine similarity between latent representations. Subsequently, we quantified the similarity between the embedding spaces by correlating the distributions of these overall cosine similarities. The correlation is computed as Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC).

Substructural attribution analysis

To evaluate the significance of substructures in predicting the approval or unapproval status of a chemical compound using ChemAP, we computed the attribution of substructures within ECFP4 by using the Captum package44 in Python. Captum provides a gradient-based model interpretation method to compute the attribution of input features. The RDKit package32 was employed for the visualization of attributed substructures. We extracted the top 100 substructures relevant to the prediction of approval and unapproval, respectively. To analyze whether the identified significant substructures are associated with the actual approval status of drugs, we defined a structure score StS, which is calculated as follows.

| 12 |

where cs denotes chemical structure features, is k-th bit of fingerprint of drug i. denotes an indicator function that yields 1 if fp is in S, and 0 otherwise. and denote the top-100 substructures for prediction of approval and unapproval, respectively. To avoid division by zero, a pseudo count was added to both the denominator and numerator.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (NRF-2022M3E5F3085677). This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT (2022M3E5F3085681). The ICT at Seoul National University provides research facilities for this study. This research was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science & ICT(RS-2023-00257479). This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) [RS-2021-II211343, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (Seoul National University)]. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00246586). This work was funded by AIGENDRUG CO., LTD.

Author contributions

C.C., S.L. and S.K. conceived the experiments, C.C. conducted the experiments, C.C., S.L. and S.K. analysed the results, C.C., and S.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data used for training and evaluation in this article curated from https://github.com/HUBioDataLab/DrugApp. The external data used for evaluation in this article curated from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda/novel-drug-approvals-2023 and https://clinicaltrials.gov/. All data is available at our repository https://github.com/ChangyunCho/ChemAP.

Code availability

The source code for ChemAP is available at the following repository https://github.com/ChangyunCho/ChemAP.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Changyun Cho and Sangseon Lee.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72868-0.

References

- 1.Scannell, J. W., Blanckley, A., Boldon, H. & Warrington, B. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical r &d efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.11, 191–200 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu, W. et al. Geodili: A robust and interpretable model for drug-induced liver injury prediction using graph neural network-based molecular geometric representation. Chem. Res. Toxicol.36, 1717–1730 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, J. et al. Predicting drug-induced liver injury using graph attention mechanism and molecular fingerprints. Methods221, 18–26 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim, S. et al. Supervised chemical graph mining improves drug-induced liver injury prediction. iScience[SPACE]10.1016/j.isci.2022.105677 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park, S., Lee, S., Pak, M. & Kim, S. Dual representation learning for predicting drug-side effect frequency using protein target information. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf.[SPACE]10.1109/JBHI.2024.3350083 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park, K. A review of computational drug repurposing. Trans. Clin. Pharmacol.27, 59–63 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo, A. W., Siah, K. W. & Wong, C. H. Machine learning with statistical imputation for predicting drug approvals, vol. 60 (SSRN, 2019).

- 8.Siah, K. W. et al. Predicting drug approvals: The novartis data science and artificial intelligence challenge. Patterns[SPACE]10.1016/j.patter.2021.100312 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciray, F. & Doğan, T. Machine learning-based prediction of drug approvals using molecular, physicochemical, clinical trial, and patent-related features. Expert Opin. Drug Discov.17, 1425–1441 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park, M., Kim, D., Kim, I., Im, S.-H. & Kim, S. Drug approval prediction based on the discrepancy in gene perturbation effects between cells and humans. EBioMedicine94, 104705 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamijo, K., Mitsumori, Y., Kato, H. & Kato, A. Drug approval prediction using patents. In 2023 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering and Technology (PICMET), 1–12 (IEEE, 2023).

- 12.John, L., Mahanta, H. J., Soujanya, Y. & Sastry, G. N. Assessing machine learning approaches for predicting failures of investigational drug candidates during clinical trials. Comput. Biol. Med.153, 106494 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, H., Lee, J., Ahn, S. & Lee, J. R. A merged molecular representation learning for molecular properties prediction with a web-based service. Sci. Rep.11, 11028 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou, G. et al. Uni-mol: A universal 3d molecular representation learning framework. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

- 15.Wang, Y., Wang, J., Cao, Z. & Barati Farimani, A. Molecular contrastive learning of representations via graph neural networks. Nat. Mach. Intell.4, 279–287 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross, J. et al. Large-scale chemical language representations capture molecular structure and properties. Nat. Mach. Intell.4, 1256–1264 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maziarka, Ł. et al. Molecule attention transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.08264 (2020).

- 18.Yun, S., Jeong, M., Kim, R., Kang, J. & Kim, H. J. Graph transformer networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.32 (2019).

- 19.Liu, S. et al. Pre-training molecular graph representation with 3d geometry. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.07728 (2021).

- 20.Johnson, B. M., Shu, Y.-Z., Zhuo, X. & Meanwell, N. A. Metabolic and pharmaceutical aspects of fluorinated compounds. J. Med. Chem.63, 6315–6386 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyzer, J. L. & Martens, M. Metabolism and toxicity of fluorine compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol.34, 678–680 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LLC, M. S. D. An active-controlled extension study to nct01155466 [p04938] and nct01227265 [p07037] (p06153) (2018). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01215227.

- 23.LLC, M. S. D. Placebo controlled study of preladenant in participants with moderate to severe parkinson’s disease (p07037) (2018). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01227265.

- 24.University, G. Maintenance dovitinib for colorectal and pancreas cancer (2016). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01888965.

- 25.Zarin, D. A., Tse, T., Williams, R. J., Califf, R. M. & Ide, N. C. The clinicaltrials. gov results database-update and key issues. N. Engl. J. Med.364, 852–860 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schultz, T. W. & Applehans, F. M. Correlations for the acute toxicity of multiple nitrogen substituted aromatic molecules. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.10, 75–85 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobetičová, K., Bezchlebová, J., Lána, J., Sochová, I. & Hofman, J. Toxicity of four nitrogen-heterocyclic polyaromatic hydrocarbons (npahs) to soil organisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.71, 650–660 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wishart, D. S. et al. Drugbank 5.0: a major update to the drugbank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res.46, D1074–D1082 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaulton, A. et al. Chembl: A large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res.40, D1100–D1107 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papadatos, G. et al. Surechembl: A large-scale, chemically annotated patent document database. Nucleic Acids Res.44, D1220–D1228 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toole, A., Jones, C. & Madhavan, S. Patentsview: An open data platform to advance science and technology policy (Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landrum, G. et al. Rdkit: Open-source cheminformatics software (2016).

- 33.Kim, S. et al. Pubchem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res.51, D1373–D1380 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, L., Chen, Z. & Qian, Y. Knowledge distillation from multi-modality to single-modality for person verification. Proc. Interspeech2021, 1897–1901 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi, Y. et al. A single stage knowledge distillation network for brain tumor segmentation on limited mr image modalities. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed.240, 107644 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong, F., Shen, C. & Wang, X. Generalized knowledge distillation for unimodal glioma segmentation from multimodal models. Electronics12, 1516 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hinton, G., Vinyals, O. & Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

- 38.RomeroA, B., Kahou, S. et al. Fitnets: hintsforthindeepnets (2014).

- 39.Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.12, 2825–2830 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 785–794 (2016).

- 41.Prokhorenkova, L., Gusev, G., Vorobev, A., Dorogush, A. V. & Gulin, A. Catboost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.31 (2018).

- 42.Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.32 (2019).

- 43.Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2623–2631 (2019).

- 44.Kokhlikyan, N. et al. Captum: A unified and generic model interpretability library for pytorch (2020). 2009.07896.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used for training and evaluation in this article curated from https://github.com/HUBioDataLab/DrugApp. The external data used for evaluation in this article curated from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/novel-drug-approvals-fda/novel-drug-approvals-2023 and https://clinicaltrials.gov/. All data is available at our repository https://github.com/ChangyunCho/ChemAP.

The source code for ChemAP is available at the following repository https://github.com/ChangyunCho/ChemAP.