Abstract

The introduction of trusted execution environments (TEEs), such as secure enclaves provided by the Intel SGX technology has enabled secure and privacy-preserving computation on the cloud. The stringent resource limitations, such as memory constraints, required by some TEEs necessitates the development of computational approaches with reduced memory usage, such as sketching. One example is the SkSES method for GWAS on a cohort of case and control samples from multiple institutions, which identifies the most significant SNPs in a privacy-preserving manner without disclosing sensitive genotype information to other institutions or the cloud service provider. Here we show how to improve the performance of SkSES on large datasets by augmenting it with a learning-augmented approach. Specifically, we show how individual institutions can perform smaller scale GWAS on their own datasets and identify two sets of variants according to certain criteria, which are then used to guide the sketching process to more accurately identify significant variants over the collective dataset. The new method achieves up to 40% accuracy gain compared to the original SkSES method under the same memory constraints on datasets we tested on. The code is available at https://github.com/alreadydone/sgx-genome-variants-search.

1. Introduction

The ongoing expansion and increasing significance of genomic datasets necessitate the development of privacy-preserving and secure methods to process and analyze them. Genomic data carries sensitive insights into an individual’s predisposition to diseases [1], extending potential privacy implications to their biological relatives [2]. The inherent immutability of genomic information and the potential for unforeseen privacy breaches in the future [3] highlight the criticality of safeguarding this data. As a result, policies or law could severely limit or fully prohibit exchange of genomic data between hospitals, research institutions, government organizations and countries. A number of cryptographic techniques [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11] have been proposed to address privacy concerns related to genomic data, but their high computational overhead means they cannot scale up to offer the performance needed for real-life genomic analysis [12, 13, 14, 15].

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) aims to identify genetic variants associated with a particular trait (e.g. disease), and it does so by computing a certain statistic for each variant over a large cohort of cases and controls. Bringing together such a cohort, especially for rare diseases, may necessitate multiple institutions, possibly from several countries, to share data and collectively develop an accurate model. SkSES (sketching algorithms for secure-enclave-based genomic data analysis) [16] is a computational framework to perform secure collaborative GWAS in an untrusted cloud platform with minimal performance overhead, through the use of Intel’s Software Guard Extensions (SGX) [17], a combined hardware and software platform supported by all current-generation Intel processors, that offers users sensitive data analysis within a protected enclave. Each sample’s genotype vector is encrypted and uploaded independently to the secure enclave, and it is decrypted there, so no institution nor the cloud provider could gain access to the sensitive genomic data, alleviating privacy concerns for such large collaborative genomic analysis.

Unlike software-based techniques such as the garbled-circuit-based FlexSC framework [18] or the homomorphic encryption-based HElib framework [19], the SGX platform does not introduce substantial computational overhead or restrictions on basic operations, and thus is likely to make secure genome-scale data analysis feasible. However, it does come with memory limitations, which SkSES addresses by a “sketching” approach to summarize variant frequencies within the limited memory of the secure enclave and identify the most significant variants across case and control samples (i.e., those that best differentiate the case and control samples) according to the statistic.

One key challenge in GWAS is sorting out systematic differences between different human subpopulations [20]: disease-causing genetic changes may get passed down alongside harmless ones, leading to false hits. This confounding effect is known as population stratification and requires mitigation using methods such as EIGENSTRAT [21], which subtracts off principal components identified through PCA. Due to limited memory of the enclave, sketching is also applied by SkSES to perform PCA.

As the size of the dataset increases, the sketches become more crowded, and the estimation error soars. We hypothesize that “collisions”, i.e., multiple significant (in terms of the statistic used by the GWAS or another quantity used as a proxy for the statistic) SNPs being assigned to the same entry (i.e., “bucket”) in the sketches, might be a main contributing factor to the error. In this paper, we address this issue by introducing a learning-augmented approach to identify the most significant SNPs in a training dataset and assign them to “unique buckets” outside of the sketches; this also reduces their impact on the estimated quantity for SNPs that are non-significant. In addition, we show how to identify another set of representative SNPs that are most useful for accurately identifying principal components during PCA for reducing the impact of population stratification via EIGENSTRAT. These SNPs are identified by running GWAS on a much smaller dataset (say 10% of the size of the full dataset), which can be done much less costly and locally by each or any of the data-holding parties involved. According to our tests, by employing these two sets of SNPs, our learning-augmented version of SkSES significantly improves the accuracy of the original version of SkSES without introducing any overhead with respect to memory usage or speed.

2. Methods

2.1. Preliminaries

2.1.1. The SGX platform in a nutshell

Intel SGX (Software Guard Extensions) is a commonly-used Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) technology embedded in modern Intel CPU models, which offers hardware-based protection for applications running inside an SGX enclave - an isolated and protected computing environment against adversaries controlling the host operating system. The security model provided by SGX hardware can prevent adversaries from learning private data or modifying the control flow of a protected application without compromising the hardware itself. As such a common use case of SGX is for secure outsourced computation, in which a user with limited computational capabilities sends private data to a remote SGX enclave, controlled by an untrusted party, for secure data processing. This enticing possibility has been gathering increasing attention in the bioinformatics community in recent years [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 16, 28, 29, 30] due to its potential to accelerate scientific discoveries by facilitating the sharing of sensitive biomedical data. For security in the outsourcing scenario, SGX usually employs a cryptographic protocol called remote attestation to provide proof to a remote user that both the enclave environment and the application running inside the enclave would not be tampered with; and that the communication channel for the transfer of sensitive data is secure.

In this work, we focus on the algorithmic improvement on the GWAS protocol but do not address the potential side-channel leaks which refer to externally measurable behaviors of the program (e.g. runtime or memory access patterns) that may be used to infer the underlying sensitive data. Note that side-channel attacks can be usually addressed with an oblivious implementation of the algorithm but at the cost of increased running time.

2.1.2. An overview of the SkSES method for identifying the top SNPs in an SGX enclave

We focus on the most general GWAS protocol introduced by SkSES [16] involving three steps: (i) Population stratification correction using PCA; (ii) Top SNP candidate identification by sketching; and (iii) Top SNP identification among the candidates. The computation process involves a server equipped with Intel SGX hardware, and the client(s) that want to perform collaborative GWAS in a privacy-preserving and secure manner. Each of the three steps requires the client(s) to encrypt and send the VCF files they store in a compressed format by only keeping the SNP IDs and their zygosity status. The server, i.e., the SGX enclave memory maintains a distinct data structure for each step, which is updated online after the server receives each compressed and encrypted VCF file from the clients. In each step, once all incoming data have been processed, the server postprocess the data structure and computes all necessary intermediate results required for the next step (or the final output). The size of these intermediate results is usually small (negligible compared to the data structures) and thus are stored independently (from the data structures) in the enclave memory. Finally, after the last step the results consisting of the top significant SNPs according to the desired association test are sent back to the clients. We describe each of the steps in more detail below.

(i). Population stratification correction using PCA.

In this step the server constructs a sketch genotype matrix which corresponds to a random projection (of the columns) of the underlying genotype matrix given by the input individuals (VCF files). Specifically, denotes the genotype matrix where is the number of VCF files and is the total number of SNPs included in the samples; denotes the sketch matrix of size which can fit in the enclave memory, where is a sparse count-sketch matrix of size with exactly one random ±1 entry in each row. A compressed and encrypted VCF file encodes all non-zero entries in a particular row in . The update of from the -th individual simply involves adding a vector to the -th row of . After all encrypted VCF files are processed, the server first normalize each column of by subtracting the mean and optionally normalizing by the standard deviation. Let the normalized matrix be . Then SVD is performed on to compute the top left singular vectors of size , which will be stored in the enclave memory and used in the following steps of computation. In addition, the phenotype vector (or ) which indicates the underlying phenotype (disease status) for each genotype vector also needs to be stored if the input VCF files are sent from the client in a random order.

(ii). Top SNP candidate identification by sketching.

In this step the server keeps independent sketches, each of size , for approximate queries of , a linear proxy to the statistic defined below. Specifically, let denote the -th column of the genotype matrix , then is given by the dot product of and the phenotype vector with ±1 entries corrected by the top eigenvectors . Let . For updating the sketches the server maintains (i) independent hash functions , where each hash function maps a SNP to one of the buckets; and additionally (ii) sign functions . Let denote the array of size of hash buckets that correspond to hash function . Initially all entries in the sketches are set to 0. To update the sketches, the server first precomputes a corrected phenotype vector with ±1 entries , and then processes each encrypted VCF and adds to , for each SNP and hash function . Once all incoming data has been processed, the client sends the entire list of SNP IDs to the server. For each SNP ID , the server queries the sketches and computes the median . The top SNP IDs according to the absolute value of are kept for the next step. Ideally, these SNPs include all top SNPs according to the actual defined below.

(iii). Top SNP identification among the candidates.

In this step we rank the SNPs according to the Armitage trend statistic and return the largest SNPs. The test statistic is defined for each SNP as

where denotes the entries in a population stratification corrected genotype matrix denotes the entries in a population stratification corrected phenotype vector . Rather than explicitly keeping the corrected genotype matrix which requires memory, SkSES implemented an algorithm which only maintains in the enclave floating point numbers for each SNP with a hash table (so the total memory required is ), and these numbers are updated while processing the next individual . Once all individuals are processed the Armitage trend statistic for each SNP can be computed exactly, and finally the top SNPs according to are returned to the client. We omitted the algorithmic details of how SkSES updates these numbers with as this step is not modified with “learning-augmented” sketches described in the following section.

2.2. Our learning-augmented sketching approach for privacy preserving GWAS

We offer two major improvements over the SkSES method for (i) the PCA step and (ii) the top SNP candidate identification step, by newly using learning-augmented sketches. To achieve this, we introduced a new pre-computing step, for which we assume that there is a small number of publicly available VCF files to be used as a training set; in case such a training set is not publicly available, a “small” proportion of the VCF files in the input is sampled (with a default of ) and used as a training set. From the training set, the pre-computing step “learns” two sets of potentially significant SNPs in distinct phases: in the first phase, it computes for assisting with SkSES’ step (i) and in the second phase, it computes , for assisting with SkSES step (ii). Note that both phases of the pre-computing step can be executed locally and outside a secure enclave. For example, when multiple computation parties are involved in a collaborative GWAS study, the sets and can be pre-computed in advance and locally by one of the computation parties, using the training set. Next, we modified steps (i) and (ii) of the SkSES’ secure GWAS protocol so that the sets and of potentially significant SNPs are sent to the server, along with all input data (i.e. preprocessed and compressed VCF files), for PCA and top SNP candidate identification by sketching.

In the remainder of the paper we denote by be the number of the VCF files in the training set and by the total number of SNP records available in each one of the VCF files in the training set.

(i). Improved PCA with learned SNPs.

The first phase of our new pre-computing step identifies the set of most significant SNPs on the test set, i.e., genotype matrix . For that, we follow the same normalization process as SkSES to compute a mean-centered and standard deviation corrected genotype matrix from . Then we compute the first eigenvector of the covariance matrix exactly. We pick the top SNPs as , according to their cosine similarities betwen each column vector in and the top eigenvector (recall that each SNP corresponds to a column vector in ).

Following the pre-computing step, the set of SNP IDs is encrypted and sent to the server. Our newly modified step (i) of SkSES, now computes the top eigenvectors from the entire samples within the secure enclave. For that, all participating parties send their encrypted VCF files to the server, which filters out all SNPs which are not present in , and performs SVD on the resulting genotype (sub)matrix of dimension . Mean centering and normalization by row standard deviations before SVD (to compute from ) are now done explicitly and in place.

We note that by itself is not sensitive (in fact it is part of the GWAS protocol), and as such, we do not attempt to hide the message length of the encrypted SNP IDs sending to the server.

(ii). Improved top SNP candidate identification with unique buckets.

In the second phase of our new pre-computing step, we identify the set of SNPs by simply picking up SNPs with largest on the training set of individuals among the SNPs. is then sent to the server just like as described above.

Our newly modified step (ii) of SkSES works as follows. First, the size of is determined by the desired size of sketches to be maintained in the enclave memory, namely the product of , the number of buckets in each sketch and , the number of independent sketches: we split the buckets originally assigned for sketches into two parts. The first buckets are allocated to maintain the SNP IDs as well as for each SNP (this time, computed from the entire set of individuals), through a hash table so that can be queried exactly. As such is given by 1. We refer to these buckets as “unique buckets” in the following and denote them as . The remaining buckets are assigned to the sketches , each of size reduced to . By default we set , meaning half of the buckets originally used for maintaining sketches in the enclave memory are assigned as unique buckets . To process an encrypted VCF file that includes a SNP , the server first checks whether the SNP ID is maintained in the unique buckets. If yes, then we add to the unique bucket , otherwise update the sketch entries to for each . After all incoming VCF files has been processed, the client again sends the entire list of SNP IDs to the server. The server modified its querying process for SNP by also first checking whether lies in the unique buckets. If yes, then the query returns the value currently stored in as the exact ; otherwise sketch entries are queried and an approximate is returned. Still the largest SNPs according to the absolute value of (or ) are stored as candidates for the top SNP identification in the next step.

Comparison with existing work on learning augmented algorithms.

There are a number of recent works in using machine learning to augment the performance of classical algorithms [31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]. Unlike the most relevant Learning-enhanced Frequency Estimation Algorithms [32], where the IP addresses carry meaningful features, we cannot extract meaningful features from the SNP IDs (rsid) alone. We do not have enough memory to store auxiliary data inside the enclave, and querying an external database would leak information. So we resort to memorization rather than generalization, i.e. we learn explicit sets of SNPs rather than an oracle to classify the SNPs.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset

We evaluated our approach on a dataset from the UK Biobank consisting of 7,550 GVCF files, with 3,775 from type 2 diabetes patients2 (cases), and the other 3,775 from non-patients (controls). These GVCF files include in total 9.54×105 distinct SNPs, and we performed imputation on each individual with the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 [37] reference panel which includes 7.82 × 107 distinct SNPs in the human genome. We sampled random subsets of 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 and 3200 imputed GVCF files to use them as training sets for our learning augmented approach, and then applied it to test sets composed of, again randomly sampled 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 imputed GVCF files (the training and test sets did not overlap and they were both composed 50% cases and 50% controls) to evaluate the performance of our approach.

Note that each of the original 7,550 GVCF files from the UK Biobank contains ~80k variant records. Before using them as inputs to our approach we processed each GVCF file by first phasing its variants using SHAPEIT4 [38] and then imputed the missing allele specific variants using Minimac [39]. After imputation, each resulting VCF ended up containing genotype information of 7.82 × 107 variants as mentioned above. Interestingly only 2.35 × 107 of the variants were present in at least one of the 7,550 individuals, so the remainder of the variants were removed from the VCFs. Therefore, all training and test sets we used were comprised of 2.35 × 107 (n ≤ 2.35 × 107) variant records. Please see the supplementary materials for further details about how we prepared our datasets.

3.2. Tested methods and parameters

We tested our learning-augmented sketching method against the SkSES baseline on the datasets described below. We report the results from our main fully-learned approach, where we utilize both sets of learned SNPs (for PCA) and (for unique buckets), as well as three different approaches that each uses only part of the full method to study their individual effect: the learned PCA approach where we only utilize , the learned unique approach where we only utilize , and the no sketch approach, where both and are used but the sketch is completely removed in favor of the unique buckets.

For all four learning-augmented sketching methods, we ensured that the training set was evenly split between cases and controls just like the full dataset it was sampled from. The original SkSES method does not use a training set. We set the size of the set of learned SNPs (for PCA) to be , consistent with the sketch matrix dimension used in the original SkSES. We used two principal components for population stratification correction (), the default setting of SkSES. We set the number of candidates to be 220. The size of training set , the size of sketches , and the number of unique buckets vary between different experiment settings.

3.3. Memory and time consumption

We first compared the runtime and memory consumption of the learning-augmented sketching approach (fully-learned) with that of SkSES. We ensured that the fully-learned method uses the same amount of memory as the original SkSES algorithm. Numeric values are stored as 32-bit floating numbers, occupying 4B of memory each. The memory requirements of the three steps described in Section 2.1.2 are as follows. (i) PCA requires memory. (ii) Sketching memory requirements depend on other parameters. For SkSES, we chose the parameters and for the sketching arrays, occupying 64MB memory in total. For our learning-augmented sketching method, we used sketching arrays with parameters and (32MB) together with unique buckets (32MB). (iii) Computing the values accurately for the candidates requires .

Note that, while transitioning from step (ii) to (iii), and before the sketching arrays and unique buckets are cleared, each approach (including SkSES) requires and additional memory. Therefore, during all our tests the memory used by each method at any point of execution was at most 72MB, ignoring a small overhead. This means that the parameters , and could be further increased, but how we should increase them for optimal performance while remaining within 128MB or a higher upper bound would be the subject of future work.

In our tests, our learning augmented method takes 1,978 seconds to complete step (i), 4,419 seconds to complete step (ii) (which are significantly faster than the original SkSES algorithm), and 1,323 seconds to complete step (iii) (see Table 1). These numbers do not include the the time for training and preprocessing (including compression and encryption) the VCF files, which can be done locally by each participating party individually with low cost. The tests were run on a Linux server equipped with an SGX-capable Intel Xeon E3–1280 v5 processor with 4 cores at 3.70 GHz.

Table 1:

Running time performance of learning-augmented sketching method (fully-learned) against SkSES, with identical enclave memory allocated to core data structures. Mean running time ± standard deviation is reported from the results of five runs. In step (i) popstrat correction using PCA, we set = 4096 for both methods. In Step (ii) top l SNP candidate identification by sketching, we set d = 8 and w = 221 for the sketch in the SkSES method; d = 8 and w = 220 for the sketch together with = 222 unique buckets for learning-augmented sketching method, so that both methods use 64MB memory. In step (iii) top-k SNP identification among l we set l = 220 for both methods. In our implementation of the fully-learned method, we replaced the Robin Hood hash table (used in step (iii)) in the original SkSES by a plain array to fix a bug, which results in a slowdown. If the fix is directly applied to the original SkSES, step (iii) slows down to 1255±13s.

| Step/Method | SkSES | fully-learned |

|---|---|---|

| (i) Popstrat correction using PCA | 3846± 16s | 1610± 10s |

| (ii) Top-l SNP candidate identification by sketching | 8767±100s | 4294±222s |

| (iii) Top-k SNP identification among l candidates | 32± 0s | 1240± 11s |

We additionally tested the running time performance with varying sketch width and depth , and concluded that the time consumed by step (ii) appears to be determined mostly by ; in fact starting from the time roughly doubles as doubles, even though the amount of read/writes remain the same. Decreasing by increasing or introducing unique buckets is therefore beneficial for reducing running times.

3.4. Accuracy of sketches

We performed three sets of experiments to assess our learning augmented sketching approach. In the first set of experiments we assessed the impact of the training set size, in comparison to the test set size. In the second set of experiments we assessed the impact of the size of the sketches and the number of unique buckets. In the third and final set of experiments we assessed how our learning augmented sketching approach compares against the baseline approaches and how individual components of the full approach contribute to its performance for various test set sizes.

The metric we used to evaluate performance of the algorithms is the true positive rate, defined to be the percentage of the top SNPs identified that are actually among the top , according to the Cochran–Armitage trend statistic. We report the percentage for both (with Cochran–Armitage from 1000/2000/4000 individuals) and (with Cochran–Armitage from 1000/2000/4000 individuals).

3.4.1. Impact of training set size

In the first set of experiments we assessed the impact of the training set size on accuracy, given the test set size. We used the following settings in these experiments (which, as per Table 3, provide the best results): the number of unique buckets are 222, the sketch depth is 8 and the sketch width is 220. Note that we used training sets disjoint from the tests sets.3 As demonstrated in Table 2, the impact of training set size on the accuracy is minimal, as long as the training set size is at least 200. In fact, if the whole test set is used as the training set, we do not get much (or any) improvement: for the 1,000-individual test set we get 1.000/0.899; for the 2,000-individual test set we get 0.990/0.824; for the 4,000-individual test set we get 0.940/0.788.

Table 3:

Accuracy of the fully-learned approach under various configurations for the sketch width (rows) and the number of unique buckets (columns) on a test set with 4000 individuals trained on an independent, randomly selected set with 400 individuals (sketch depth: 8). For each number of unique buckets (column) and each sketch width (row), we give the accuracy values for both the top-100 (left) and top-1000 (right) SNPs. The results in the rightmost column are those with no (learned) unique buckets but with learned PCA. The same amount of memory is used for the unique buckets as the sketch for entries along the main diagonal (except for the rightmost column). The entry marked with

| Sketch width | Number of unique buckets () | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (w) | 223 | 222 | 221 | 220 | 0 |

|

| |||||

| 221 | 0.940/0.791 | 0.950/0.784 | 0.790/0.753 | 0.730/0.697 | 0.590/0.653 |

|

| |||||

| 220 | 0.940/0.788 | 0.900/0.770* | 0.650/0.672 | 0.600/0.635 | 0.470/0.555 |

|

| |||||

| 219 | 0.940/0.785 | 0.570/0.668 | 0.540/0.611 | 0.500/0.543 | 0.400/0.440 |

|

| |||||

| 218 | 0.920/0.769 | 0.490/0.580 | 0.440/0.465 | 0.350/0.440 | 0.240/0.318 |

|

| |||||

| 217 | 0.440/0.602 | 0.410/0.484 | 0.260/0.349 | 0.180/0.288 | 0.120/0.205 |

is the configuration used in the (Figures of the) remainder of the paper; it is the first diagonal entry that fits within 128MB SGX enclave memory.

Table 2:

Accuracy of the fully-learned method (with 222 unique buckets and a sketch of depth 8 and width 220) as a function of training set size. Note that the training sets were sampled from 3550 individuals disjoint from test sets with 1000/2000/4000 individuals. With each training set (column) and each test set (row) size, we give the accuracy values for both the top-100 (left) and top-1000 (right) SNPs. The three entries marked withs

| Size of test set | Size of training set | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 200 | 400 | 800 | 1600 | 3200 | |

|

| ||||||

| 1000 | 0.990/0.768* | 1.000/0.913 | 1.000/0.902 | 1.000/0.898 | 0.990/0.895 | 0.990/0.883 |

|

| ||||||

| 2000 | 1.000/0.772 | 0.990/0.806* | 0.990/0.820 | 0.990/0.778 | 0.990/0.796 | 0.990/0.817 |

|

| ||||||

| 4000 | 0.910/0.671 | 0.920/0.782 | 0.860/0.755* | 0.750/0.771 | 0.940/0.783 | 0.910/0.777 |

are the configurations used in the (Figures in the) remainder of the paper.

3.4.2. Impact of sketch size and unique bucket count

In the second set of experiments we assessed the impact of the sketch size vs the number of unique buckets on accuracy (training set size: 400, test set size: 4,000). As demonstrated in Table 3, for a given number of unique buckets, there is a sharp drop in accuracy as the sketch width decreases, probably because when the sketch is small, the values accumulated in the sketch and hence the queried values are systematically larger (in absolute value) than the values in the unique buckets, leading to few or none of the SNPs in unique buckets being selected as the top candidates. We leave a more comprehensive study of methods to balance the sketch size and the number of unique buckets to future work.

3.4.3. Comparison with baseline and ablation study

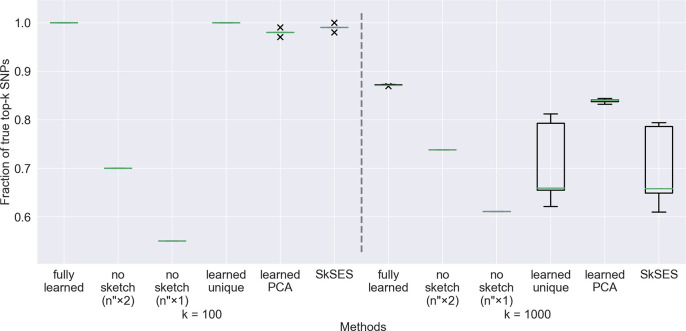

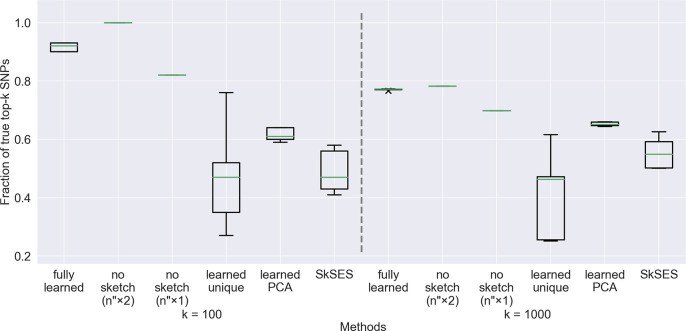

In the next set of experiments, we compared the accuracies of the four learning-augmented approaches with the SkSES baseline. Results from five runs of each method are shown as box plots in Figures 1, 2 and and 3, except for the “no sketch” approach, which is only run once because no randomness is involved. All other methods use random hash functions for the sketch, and the “learned unique” and SkSES methods also use a different random seed for each run to generate the sketch matrix for PCA. The training sets stay the same across five runs.

Figure 1:

Accuracy comparison of the five approaches on a dataset of 1,000 individuals, using a training set of 100 individuals. The percentages of the actual top 100 and top 1,000 SNPs identified are shown. Both the “learned unique” and SkSES methods use a randomly signed sketch matrix generated by a random seed, and we observe that some random seeds lead to exceptionally good results (for example the outliers near 0.8 in with for both methods); these seeds appear roughly 20% of the time when randomly selected.

Figure 2:

Accuracy results on a dataset of 2,000 individuals using a training set of 200 individuals. The large variations in accuracy of the “learned unique” and SkSES approaches are due to the use of a random seed to generate the sketch matrix .

Figure 3:

Accuracy results on a dataset of 4,000 individuals using a training set of 400 individuals. The large variations in accuracy of the “learned unique” and SkSES approaches are due to the use of a random seed to generate the sketch matrix . Notice that the “fully learned” method is not superior to “no sketch” under memory parity () here (while it is superior on the 1,000- and 2,000-individual test sets), but the usefulness of sketching can still be seen when compared with “no sketch” ().

For all four learning-augmented methods, the training set size is fixed to be 10% of the test set size, which can be compared against entries marked with * in Table 2. We ensure all methods use the same amount of memory in step (ii) in order to compare them fairly: the sketch depth and width for the main approach (fully-learned) are respectively fixed at 8 and 220, and the unique bucket count is fixed at 222, which is marked with * in Table 3. For the other approaches, if sketching is not used (“no sketch”) then the unique bucket count is doubled (fixed at 223), while if unique buckets are not used (“learned PCA” and SkSES) then the sketch width is doubled (fixed at 221). Since we also report the performance of the “no sketch” approach without doubling the unique bucket count in the same figures - to assess the accuracy gains that can be attributed to sketching, we distinguish the two setups by their labels: “no sketch ()” v.s. “no sketch () respectively.

Under the same memory constraint, our fully-learned approach scored a 40% absolute improvement (from ~ 50% to > 90%) of the percentage on the 4,000-individual test set when , and a 20% absolute improvement of the percentage when , compared to the original SkSES algorithm (our baseline); see Figure 3. The improvement on the 2,000- and 1,000-individual test sets are less pronounced but still clearly visible, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

It is crucial to utilize the small set of significant SNPs in the PCA step to create the sketch matrix for PCA, which leads to major improvement and stabilization of performance. If we used a randomly signed sketch matrix as in the original SkSES (the “learned unique” approach), the performance is very unstable: for about 10% of such randomly chosen matrices, we get performance matching the performance of “fully learned” approach, but most of the time we get very poor results. It is still an open question why using a subset of SNPs that is order-of-magnitudes smaller than yields more stable eigenvector results than using the whole 23 million SNPs in a sketched form, and we leave this to future work.

3.5. Using a non-representative training set

To show robustness of our method, we tested its performance using training sets that are not representative of the whole test set. Specifically, we selected 400-individual subsets “of different ethnicities” from the 4000-individual test set in the following way: for , we take the -th eigenvector (where corresponds to the top eigenvalue) of the covariance matrix of the normalized genotype matrix , and pick the 400 individuals with (i) the largest, and then (ii) the smallest , and use them to form the training set.4 As shown in the table below, the results are similar to those using a disjoint (§3.4.1) or sampled (§3.4.3) training set. For the 400 individuals with the smallest , the result is quite poor for (corresponding to the top eigenvector, presumably representing the most common ethnic contribution to this cohort), but remains good for .5

Supplementary Material

Table 4:

Accuracy of the fully-learned approach using a non-representative training set. For each k, the training set consists of the individuals j in the cohort, with the largest (middle row) or smallest (bottom row) 400 entries (uk)j in the kth eigenvector. For a given k, the accuracy of the fully-learned approach for the top-100/top-1000 SNPs are given.

| k | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| largest | 0.940/0.788 | 0.910/0.760 | 0.940/0.787 | 0.920/0.790 | 0.940/0.787 |

| smallest | 0.150/0.102 | 0.910/0.771 | 0.940/0.787 | 0.880/0.792 | 0.920/0.788 |

4. Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Computer Science at Indiana University, especially Haixu Tang and Xiaofeng Wang, for providing remote access to SGX-enabled machines on which we run the experiments. We also thank Hongbo Chen and Rob Henderson for providing technical assistance.

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no competing interests related to this work to declare.

we ignore the cases where as the assumption is the total number of SNPs is significantly larger than the size of the sketch, and the samples should include sufficiently large number of SNPs to be tested

the entire set of type 2 diabetes patients with relevant information in the UK Biobank

There is some minimal impact if the training sets were sampled from the test sets: a comparison of the three cells marked with * with the corresponding Figures reveal that only the 1,000 individual case has an increase in accuracy when the training set is indeed sampled from the test set.

Since is an eigenvector of the real symmetric matrix , we have for some nonnegative number , so is proportional to the dot product of th individual’s correlation vector with .

Since the dataset is from the UK Biobank, it is possible that there is a dominant ethnicity in the cohort and the selection of a training subcohort with the lowest contribution from this dominant ethnicity significantly impacted these results, especially because the SNP set , which we use for performing PCA, consists of those SNPs with the highest cosine similarity with the top eigenvector.

References

- [1].McGuire A. L. et al. Confidentiality, privacy, and security of genetic and genomic test information in electronic health records: points to consider. Genetics in Medicine 10, 495–499 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bloss C. S. Does family always matter? public genomes and their effect on relatives. Genome Medicine 5, 107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shringarpure S. S. & Bustamante C. D. Privacy risks from genomic data-sharing beacons. American Journal of Human Genetics 97, 631–646 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ayday E., Raisaro J. L., Hengartner U., Molyneaux A. & Hubaux J.-P. Privacy-preserving processing of raw genomic data. In Data Privacy Management and Autonomous Spontaneous Security, 133–147 (Springer, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- [5].He D. et al. Identifying genetic relatives without compromising privacy. Genome Research 24, 664–672 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kamm L., Bogdanov D., Laur S. & Vilo J. A new way to protect privacy in large-scale genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 29, 886–893 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McLaren P. J. et al. Privacy-preserving genomic testing in the clinic: a model using hiv treatment. Genetics in Medicine 18, 814–822 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shimizu K., Nuida K. & Rätsch G. Efficient privacy-preserving string search and an application in genomics. Bioinformatics 32, 1652–1661 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Xie W. et al. Securema: protecting participant privacy in genetic association meta-analysis. Bioinformatics 30, 3334–3341 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhao Y., Wang X., Jiang X., Ohno-Machado L. & Tang H. Choosing blindly but wisely: differentially private solicitation of dna datasets for disease marker discovery. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 22, 100–108 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shahbazi A., Bayatbabolghani F. & Blanton M. Private computation with genomic data for genome-wide association and linkage studies. In Proc. 3rd International Workshop Genome Privacy Security (2016). URL https://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~mblanton/publications/genopri16.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen F. et al. Premix: privacy-preserving estimation of individual admixture. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2016, 1747–1755 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lauter K., López-Alt A. & Naehrig M. Private computation on encrypted genomic data. In Aranha D. F. & Menezes A. (eds.) International Conference on Cryptology and Information Security in Latin America, 3–27 (Springer, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang S. et al. Healer: homomorphic computation of exact logistic regression for secure rare disease variants analysis in gwas. Bioinformatics 32, 211–218 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang Y., Blanton M. & Almashaqbeh G. Secure distributed genome analysis for gwas & sequence comparison computation. BMC medical informatics and decision making 15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kockan C. et al. Sketching algorithms for genomic data analysis and querying in a secure enclave. Nature Methods 17, 295–301 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Anati I., Gueron S., Johnson S. P. & Scarlata V. R. Innovative technology for cpu based attestation and sealing (2013). URL https://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/innovative-technology-for-cpu-based-attestation-and-sealing. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang X. S., Chan T.-H. H. & Shi E. Circuit oram: on tightness of the goldreich-ostrovsky lower bound. In Ray I., Li N. & Kruegel C. (eds.) Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 850–861 (ACM, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- [19].Halevi S. & Shoup V. Algorithms in helib. In Garay J. A. & Gennaro R. (eds.) International Cryptology Conference, 554–571 (Springer, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yang J., Zaitlen N. A., Goddard M. E., Visscher P. M. & Price A. L. Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods. Nature genetics 46, 100 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Price A. L. et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nature genetics 38, 904–909 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen F. et al. Presage: Privacy-preserving genetic testing via software guard extension. BMC medical genomics 10, 77–85 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chen F. et al. Princess: Privacy-protecting rare disease international network collaboration via encryption through software guard extensions. Bioinformatics 33, 871–878 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mandal A., Mitchell J. C., Montgomery H. & Roy A. Data oblivious genome variants search on intel sgx. In International Workshop on Data Privacy Management, 296–310 (Springer, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Carpov S. & Tortech T. Secure top most significant genome variants search: idash 2017 competition. BMC medical genomics 11, 47–55 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lambert C., Fernandes M., Decouchant J. & Esteves-Verissimo P. Maskal: Privacy preserving masked reads alignment using intel sgx . In 2018 IEEE 37th Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems (SRDS), 113–122 (IEEE, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sadat M. N., Jiang X., Al Aziz M. M., Wang S. & Mohammed N. Secure and efficient regression analysis using a hybrid cryptographic framework: Development and evaluation. JMIR medical informatics 6, e8286 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mainardi N., Sampietro D., Barenghi A. & Pelosi G. Efficient oblivious substring search via architectural support. In Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, 526–541 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dokmai N. et al. Privacy-preserving genotype imputation in a trusted execution environment. Cell Systems 12, 983–993.e7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Widanage C. et al. Hysec-flow: privacy-preserving genomic computing with sgx-based big-data analytics framework. In 2021 IEEE 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), 733–743 (IEEE, 2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dong Y., Indyk P., Razenshteyn I. & Wagner T. Learning space partitions for nearest neighbor search. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.08544 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hsu C.-Y., Indyk P., Katabi D. & Vakilian A. Learning-based frequency estimation algorithms. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [33].Indyk P., Vakilian A. & Yuan Y. Learning-based low-rank approximations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [34].Eden T. et al. Learning-based support estimation in sublinear time. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020). [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ergun J. C., Feng Z., Silwal S., Woodruff D. & Zhou S. Learning-augmented k-means clustering. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021). [Google Scholar]

- [36].Grigorescu E., Lin Y.-S., Silwal S., Song M. & Zhou S. Learning-augmented algorithms for online linear and semidefinite programming. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35, 38643–38654 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- [37].Consortium G. P. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Delaneau O., Zagury J.-F., Robinson M. R., Marchini J. L. & Dermitzakis E. T. Accurate, scalable and integrative haplotype estimation. Nature communications 10, 5436 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Das S. et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nature genetics 48, 1284–1287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Danecek P. et al. The variant call format and vcftools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.