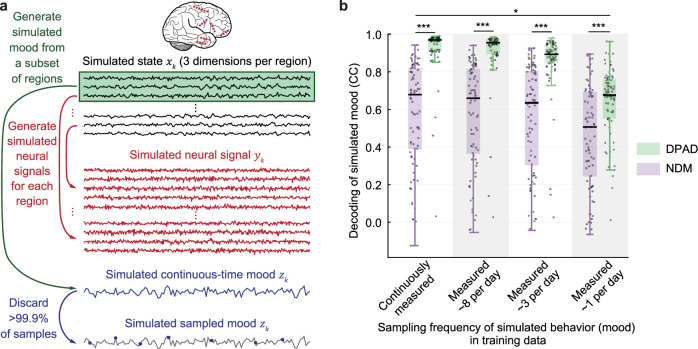

Extended Data Fig. 9. Simulations suggest that DPAD may be applicable with sparse sampling of behavior, for example with behavior being a self-reported mood survey value collected once per day.

a, We simulated the application of decoding self-reported mood variations from neural signals40,41. Neural data is simulated based on linear models fitted to intracranial neural data recorded from epilepsy subjects. Each recorded region in each subject is simulated as a linear state-space model with a 3-dimensional latent state, with the same parameters as those fitted to neural recordings from that region. Simulated latent states from a subset of regions were linearly combined to generate a simulated mood signal (that is, biomarker). As the simulated models were linear, we used the linear versions of DPAD and NDM (NDM used the subspace identification method that we found does similarly to numerical optimization for linear models in Extended Data Fig. 1). We generated the equivalent of 3 weeks of intracranial recordings, which is on the order the time-duration of the real intracranial recordings. We then subsampled the simulated mood signal (behavior) to emulate intermittent behavioral measures such as mood surveys. b, Behavior decoding results in unseen simulated test data, across N = 87 simulated models, for different sampling rates of behavior in the training data. Box edges show the 25th and 75th percentiles, solid horizontal lines show the median, whiskers show the range of data, and dots show all data points (N = 87 simulated models). Asterisks are defined as in Fig. 2b. DPAD consistently outperformed NDM regardless of how sparse behavior measures were, even when these measures were available just once per day (P < 0.0005, one-sided signed-rank, N = 87).