Abstract

The current study aims to explore the efficacy of antifungal photodynamic therapy (PDT) on C. albicans biofilms by combining photosensitizers, bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC), and melatonin (MLT) or acetyl-melatonin (AcO-MLT). Additionally, the relationship between different types of reactive oxygen species and PDT’s antifungal efficacy was investigated. BDMC, MLT and AcO-MLT were applied, alone and in combination, to 48-hour C. albicans biofilm cultures (n = 6/group). Blue and red LED light (250 mW/cm2 with 37.5 J/cm2 for single or 75 J/cm2 for dual photosensitizer groups) were used to irradiate BDMC groups and MLT/AcO-MLT groups, respectively. For combination groups, blue LEDs and subsequently red LEDs were used. Drop plate assays were performed at 0, 1 and 6 h post-treatment. Colony forming units (CFUs) were then counted after 48 h. Hydroxyl radicals and singlet oxygen were measured using fluorescence spectroscopy and electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. Additionally, cell cytotoxicity was tested on human oral keratinocytes. Significant CFU reductions were observed with combinations 20 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT and 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT at 0 and 1 h post-treatment, respectively. Singlet oxygen production increased with the addition of MLT/AcO-MLT and had moderate-substantial correlations with inhibition at all times. Hydroxyl radical production was not significantly different from the control. Additionally, BDMC exhibited subtle cytotoxicity on human oral keratinocytes. PDT using BDMC + MLT or AcO-MLT, with blue and red LED light, effectively inhibits C. albicans biofilm through singlet oxygen generation. Melatonin acts as a photosensitizer in PDT to inhibit fungal infection.

Keywords: Acetyl-melatonin, Antifungal, Bisdemethoxycurcumin, Candida albicans, Melatonin, Photodynamic therapy

Subject terms: Microbiology; Medical research; Lasers, LEDs and light sources

Introduction

Candida albicansis an opportunistic pathogen that causes oral and systemic candidiasis that can increase mortality, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Misuse of antifungal drugs has led to increased incidence of drug resistance1. Thus, other treatment modalities have been explored. One of these is photodynamic therapy (PDT) which has shown potential in antimicrobial treatment. Briefly, the mechanism of photodynamic therapy involves the production of Type I or II reactive oxygen species (ROS). This process occurs when a photosensitizer (PS), which is preferentially absorbed by the target cell, is exposed to light at a wavelength corresponding to the absorption spectrum of the PS2. Each type of PS preferentially generates either Type I or Type II ROS. Type I ROS primarily results in the production of a highly reactive radical, the hydroxyl radical (OH−), which can easily pass through cell membranes. On the other hand, type II reaction produces short-lived and highly reactive singlet oxygen (1O2). These ROS cause oxidative damage in the fungal cellular components such as the cell wall, lipids, proteins, and DNA, disrupting the fungi’s essential cellular processes. The influx of ROS also activates signaling pathways that lead to programmed cell death2,3. ROS are short-lived thus limiting the side effects of PDT to temporary erythema and light sensitivity that resolves soon after the treatment. In contrast to systemic antifungals, PDT is localized thereby limiting the negative effects to treated areas2,3. Both types of ROS can be produced in one reaction, however, the ratio of the types of ROS produced is dependent on the type of PS used, its concentration, and the amount of available oxygen4.

Several photosensitizers have been used to target candida albicans in planktonic and biofilm forms using different light settings. These studies yielded varying results. Therefore, PDT protocols against C. albicanshave not been established5. Given that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can affect distinct components within the target cells, there could be advantages in combining the effects of Type I and Type II ROS, each generated by different photosensitizers.

Bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC) is a natural derivative of curcumin which is also used as a PS in PDT. BDMC has the least antioxidant activity compared to the other natural derivatives of curcumin, reducing the potential for the PS to scavenge its own ROS6. BDMC also has very attractive hydrogen bond acceptor binding sites and thus can produce high amounts of ROS, particularly hydroxyl radicals7. The second PS explored in this study is melatonin, which is known to have antioxidant properties. It also possesses both hydrophilic and lipophilic characteristics that enable it to penetrate biological membranes. Interestingly, Maharaj et al. (2005) found that 100 µM of melatonin could generate singlet oxygen with a quantum yield of 1.41 when exposed to an Nd: YAG laser at a wavelength of 672 nm at a power of 47 mW8. For comparison, a quantum yield of less than 1 has been associated with antifungal properties in plants9. However, it is notable that melatonin has limited bioavailability and undergoes rapid metabolism. Derivatives of melatonin were developed to address some of these constraints. Acetyl-melatonin (AcO-MLT), which is similar to melatonin, exhibits enhanced stability and has been demonstrated to prevent neuronal cell death caused by oxidative stress10. The use of BDMC alone was insufficient to produce significant reductions in C. albicans, particularly at lower concentrations11. The addition of a second photosensitizer exposed to a different wavelength may enhance the anti-fungal ability of the protocol. Melatonin has not been used as a photosensitizer to target fungi. It’s anti-inflammatory properties and ability to produce singlet oxygen may enhance the effects of anti-fungal PDT.

One of the limitations of photodynamic therapy is the availability and cost of the lasers. It is generally accepted that not only lasers, but also light emitting diodes (LEDs) are capable of generating adequate power density and fluency in PDT. Blue LED light is commonly used in the dental field to polymerize dental materials, while red LED light is also used in dermatology to treat various skin conditions as it can penetrate deeper into the tissues12. A study by Dovigo et al. in 2013 and Quishida et al. in 2015 used 20–120 µM of curcumin irradiated blue LED light with an energy density of 37.5 J/cm2 and resulted in significant C. albicans reductions in murine models and in a multispecies biofilm, particularly at higher concentrations of curcumin13,14.

In the current study, the production of ROS was identified and quantified using electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO) as spin trapping agents. DPMO traps several radicals including hydroxyl radicals, superoxides, and carbon-centered radicals. DMPO adducts give unique patterns in the ESR spectrum. For example, an adduct of DMPO with a hydroxyl radical (ŸOH) displays a four-line hyperfine pattern with an intensity of 1:2:2:1. 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl (TEMPO) is a stable nitroxide radical showing a three-line spectrum with an intensity of 1:1:1. TEMPO reacts with free radicals such as carbon-centered radicals and produces non-radical molecules. Therefore, the loss of ESR signal intensity of TEMPO can be used to estimate the total radical production in a reaction15,16.

Fluorescence spectroscopy can quantify relative amounts of ROS. This method utilizes fluorescent probes that exhibit changes in their fluorescence properties upon interaction with ROS17. Fluorescence is measured using a spectrometer at specific excitation and emission wavelengths. 2-(6-(4′amino phynoxyl-3 H-xanthen-3-on-9-yl) benzoic acid (APF) is used to detect hydroxyl radicals. APF is initially non-fluorescent but becomes fluorescent upon oxidation by hydroxyl radicals18. 9,10-dimethylanthracene (DMA) selectively reacts with singlet oxygen. DMA undergoes a reaction to form a non-fluorescent product called 9,10 endoperoxide. Consequently, this leads to a decreased fluorescence intensity17,19. The quantity of ROS is computed based on the proportion of change from the baseline of the probe19.

Photodynamic therapy using high-powered lasers can cause photothermal damage to adjacent tissues. Ideally, the photosensitizers should also be selective towards pathogens and spare normal tissue from damage. Therefore, cell viability of human oral keratinocytes after photodynamic therapy was also tested using the PrestoBlue® Assay.

Thus, we aimed to examine the antifungal effect of photodynamic therapy using a combination of bisdemethoxycurcumin and melatonin/acetyl melatonin as photosensitizers with blue and red LEDs. We investigated which type of ROS mediated this effect. Additionally, the cytotoxicity of our aPDT protocol was also assessed.

Materials and methods

Candida albicans biofilm preparation

This process was based on Jin et al. (2003) and Thein et al. (2006) with slight modifications20,21. Candida albicans ATCC 10,231 (purchase from the Department of Medical Science, Thailand) was cultured in Sabouraud dextrose agar (HiMedia, PA, USA) for 48 h and 2–3 loop-full of broth were transferred to Sabouraud dextrose broth (HiMedia, PA, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The solution was then homogenized using a high-speed blender and centrifuged at 3000x g for 10 min at 25 °C. Subsequently, the culture was washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). The entire procedure was repeated three times. The optical density was adjusted to 0.380 at a wavelength of 530 nm using an absorbance spectrophotometer, resulting in a solution with 107 cells/ml.

One ml of the prepared cell solution was then dispensed into a 6-well plate containing a sterile glass coverslip. The well plate was then incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C on an orbital shaker at 75 rpm to facilitate yeast adherence. The wells were washed twice with PBS to eliminate loosely attached cells. Then, 2 ml of 1 M yeast nitrogen base (YNB) and a 50 mM glucose solution were added to stimulate biofilm growth. The plates were then further incubated on an orbital shaker under the same conditions for 48 h to allow the biofilm to mature.

Preparation of photosensitizers

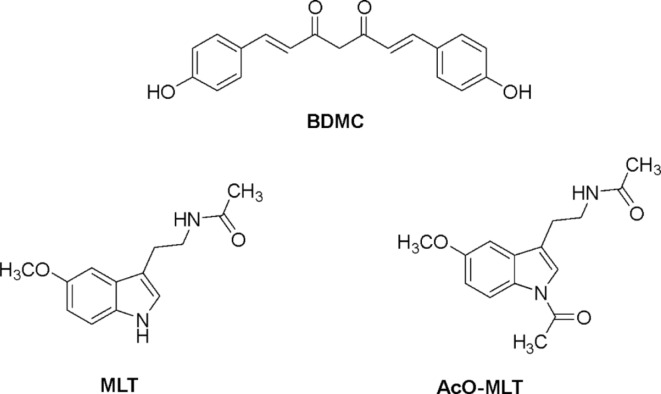

Concentrations of 20, 40 and 60 µM of BDMC (MedChem Express, NJ, USA), 20 and 100 µM MLT (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand), and 20 and 100 µM of AcO-MLT (Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, KKU, Thailand) were prepared in PBS with 1% ethanol and heated at 70 °C for 5 min. Chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Fig. 1. Combinations of BDMC + MLT or BDMC + AcO-MLT were also prepared at various concentrations, resulting in 19 test groups (Table 1). Nystatin and PBS were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of bisdemethoxycurcumin (BDMC), melatonin (MLT), and acetyl-melatonin (AcO-MLT).

Table 1.

Group allocation.

| TEST GROUPS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDMC | MLT | AcO-MLT | MLT + BDMC | AcO-MLT + BDMC | CONTROLS | |||

| 20 µM | 20 µM | 20 µM | 20 µM | 20 µM | 20 µM | 20 µM |

Nystatin (+ control) PBS (-control) |

|

| 40 µM | 100 µM | 100 µM | 40 µM | 40 µM | ||||

| 60 µM | 60 µM | 60 µM | ||||||

| 100 µM | 20 µM | 100 µM | 20 µM | |||||

| 40 µM | 40 µM | |||||||

| 60 µM | 60 µM | |||||||

| LIGHT SOURCE(LIGHT EMITTING DIODE) | BLUELIGHT | REDLIGHT | REDLIGHT | BLUE + RED LIGHT |

BLUE + RED LIGHT |

RED LIGHT ONLY BLUE LIGHT ONLY RED + BLUE LIGHT ONLY |

||

Photodynamic therapy

Following a 48-hour incubation period, the wells were washed thrice with PBS to eliminate the YNB and glucose solution as well as loosely attached cells. Subsequently, 2 ml of PS solution was added to each well, followed by a 20-minute pre-irradiation period at 37 oC in an incubator. Wells treated with BDMC were exposed to blue light (3 M™ Elipar™ DeepCure LED-L Curing Light) at a peak wavelength of 430 nm and a power density of 250 mW/cm2, with a 1 cm tip diameter placed 2.5 cm away from the bottom of the 6-well plate. However, those wells containing MLT or AcO-MLT were subjected to red LED light (Faculty of Engineering, Khon Kaen University, Thailand). The red-light source had a peak wavelength of 630 nm and a power density of 250 mW/cm2. Exposure to light was done for 2.5 min, resulting in an energy density of 37.5 J/cm2. Wells with combined PS were irradiated with blue light followed by red light, each for 2.5 min, resulting in a total energy density of 75 J/cm2. 100,000 U/ml nystatin served as a positive control, while PBS served as the negative control. Additionally, wells subjected to light without a PS were also included. After the process, the wells were incubated for 0, 1 and 6 h.

Following incubation, the wells were prepared for drop plate assays. The wells were washed thrice with PBS. 1.2 ml of PBS was added to each well followed by sonication for 15 min to detach the cells. 1.1 ml of the cell suspension was transferred to sterile microtubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min to pellet the cells. 950 µL supernatant was discarded and 50 µL of the cell pellet underwent serial dilutions up to 10−3. 10 µL of each dilution were plated onto Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Colony-forming units [CFUs/ml] were counted and logarithmic transformation was done.

Determination and relative quantification of ROS

Electron spin resonance

DMPO and TEMPO were dissolved in distilled water. The probes were added to the test solutions, achieving concentrations of 20 mM DMPO or 5 µM TEMPO and various concentrations of the test photosensitizers. One hundred µL of the test solutions were added to the individual wells of a dark 96-well plate and subjected to the same irradiation process described above, with higher power and energy densities, at 500 mW/cm2 for 150 s resulting in a 75 J/cm2 energy density. The solutions were then transferred to capillary tubes and fitted into the cavity of ESR spectrometer [Magnettech, ESR 5000, Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany]. ESR spectra were obtained with the following parameters. For DMPO: 351.0 ± 5.0 mT central field, 100 kHz modulation frequency, 0.1 mT modulation amplitude, 5.0 mW power, 13 dB receiver gain, 40 s sweep time, and a 1.28 millisecond time constant. For TEMPO: 336.5 ± 5.0 mT center field, 100 kHz modulation frequency, 0.1 mT modulation amplitude, 1.0 mW power, 20 dB receiver gain, 20 s sweep time, and a 1.28 millisecond time constant.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

To determine relative amounts of OH− radicals, APF (Sigma-Aldrich®, MA, USA) was prepared in dimethylformamide (DMF) and mixed with test photosensitizers achieving a final concentration of 10 µM APF and several desired concentrations of the test photosensitizers. One hundred µL of the test solution was exposed to the light settings described above. Ten µM curcumin in 1% ethanol and PBS were used as a positive control and the probe alone was used as the negative control. The wells were then placed into a spectrophotometer [Varioskan®, Thermofisher®, MA, USA] and subjected to measurements at λexcitation = 490 nm, λemission = 515 nm.

For singlet oxygen, 1 mM DMA in DMSO was used similarly and the final concentration as APF (10 µM), with 10 µM erythrosine was used as the positive control. A probe with distilled water was used as the negative control. The fluorescence intensities were measured at λexcitation = 375 nm, λemission = 436 nm.

Human oral keratinocyte cell viability

Keratinocyte cell culture

Keratinocytes (PCS-200-014, ATCC, VA, USA) were cultured in Dermal Cell Basal Medium (ATCC, VA, USA) mixed with Keratinocyte Growth Kit (ATCC, VA, USA) in a 75 cm2 culture flask and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2, changing to a fresh growth medium every 2–3 days until cells reach 75–80% confluence.

The culture medium was then discarded and the cells were incubated with a 0.25% w/v trypsin-0.53 mM EDTA solution at 37 °C for 10 min to allow the cells to detach. This was confirmed using an inverted microscope (Axiovert A1, Carl Zeiss, NY, USA). A 1 ml aliquot of cell suspension was stained with Tryptan Blue (Thermofisher, MA, USA) and placed in an automated cell counter (TC20, BIO-RAD®, CA, USA). The cell suspension was adjusted to achieve 1 × 105 cells/ml. One hundred µL of this suspension was placed into each well of a 96-well dark plate and exposed to the PDT protocol described above. Subsequently, the wells were incubated for 1, 6 and 24 h.

A PrestoBlue® Assay was performed after rinsing the wells twice with PBS. Ten µL of PrestoBlue® and 90 µL of growth medium were added to the wells and incubated for an hour. The readings were done using a Varioskan® microplate reader (Thermofisher®, MA, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. Cell toxicity was assessed on a 70% cell viability threshold based on ISO standards.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS software version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The groups were compared based on a reduction of colony-forming units. Normality was evaluated using the ShapiroWilk test. Since the data were not normally distributed, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to determine differences among groups. The Mann-Whitney U test with a Bonferroni correction was used for pairwise comparisons, enabling multiple comparisons. The same tests were also conducted to assess differences in the relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals and singlet oxygen produced by each test group.

Generalized linear models were used to determine the contribution of photosensitizer concentrations to the production of ROS and the antifungal effects of the protocol. The mean reductions were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Correlation between the relative amounts of hydroxyl radical or singlet oxygen and the reduction in log10 CFU/ml among the groups was assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test at each time. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Antifungal activity

Inhibition was measured at 0, 1 and 6 h after treatment. At 0 h (Figs. 2), 20 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcOMLT had significantly higher inhibition compared to the negative control, with a median inhibition of 2.10 log10 CFU/ml (interquartile range, IQR = 2.00–2.32, p = 0.03) and 0.9 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 0.85–1.03), respectively.

Fig. 2.

Candidal reduction in Log10 CFU/ml at 0 h after PDT using blue (430 nm) and red LED 630 nm with 250 mW/cm2 (energy density 37.5 J/cm2). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and Nystatin 1:100,000 unit/ml (NYST) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin. *Statistically significant difference when compared with the negative the control at p = 0.05. (n = 6).

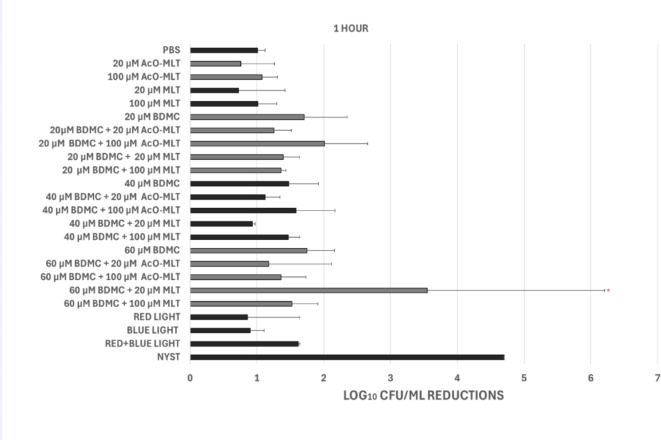

At 1 h (Figs. 3), 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT showed a significantly higher median inhibition of 3.55 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 2.04–4.7, p = 0.048) compared to the negative control with a median inhibition of 1.02 log10 CFU/ml, (IQR = 1.00–1.10).

Fig. 3.

Candidal reduction in Log10 CFU/ml at 1 h after PDT using blue (430 nm) and red LED 630 nm with 250 mW/cm2 (energy density 37.5 J/cm2). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and Nystatin 1:100,000 unit/ml (NYST) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin. *Statistically significant difference when compared with the negative the control at p = 0.05. (n = 6).

At 6 h (Fig. 4), there were no groups that significantly inhibited C. albicans. However, groups with BDMC combined with 100 µM melatonin or acetyl-melatonin tended to show higher reduction at this time, albeit not significantly different from PBS (median = 0.95 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 0.94–1.25). These are 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM MLT, 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT, 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT and 60 µM BDMC + 100 µM MLT with median reductions of 2.40 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 2.40–4.70), 2.40 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 1.87–2.40), 2.40 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 2.10–2.40), and 1.62 log10 CFU/ml (IQR = 0.84–1.70), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Candidal reduction in Log10 CFU/ml at 6 h after PDT using blue (430 nm) and red LED 630 nm with 250 mW/cm2 (energy density 37.5 J/cm2). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and Nystatin 1:100,000 unit/ml (NYST) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin. *Statistically significant difference when compared with the negative the control at p = 0.05. (n = 6).

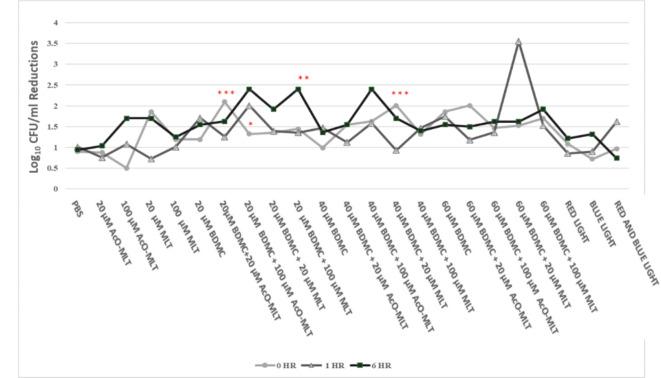

When comparing the results at various times (Fig. 5), 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT had higher median inhibitions at 1 h (2.01 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.76–2.40, p = 0.04) and 6 h (2.40 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.87–2.40, p = 0.008) compared to 0 h (1.33 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.10–1.36). Additionally, 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM MLT at 6 h (2.40 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 2.40–4.7) had significantly higher reductions compared to reductions at 0 h (1.45 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.31–1.54, p = 0.02) and 1 h (1.36 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.32–1.40, p = 0.007). In contrast, 40 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT had a significantly higher reduction at 0 h (2.01 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.57–2.40, p = 0.009) compared to reduction at 1 h (0.93 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 0.91–0.95). Similarly, 20 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT had greater reduction at 0 h (2.10 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.97–2.33) compared to 1 h (1.26 log10 CFU/ml, IQR = 1.10–1.36, p = 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Candidal reduction across time points. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin, PBS = phosphate buffer saline. *Statistically significant difference from 1- and 6- hour reductions, **Statistically significant difference from 0- and 1- hour reductions, ***Statistically significant difference between 0-hour and 1- hour reduction (p = 0.05). (n = 6).

Statistical analyses using Generalized Linear Models were performed to assess the contributions of the different photosensitizers to C. albicans inhibition, controlled for the presence of other photosensitizers.

At 0 h, when AcO-MLT and MLT were controlled for BDMC at concentrations of 20, 40, and 60 µM, they showed increased reductions of 0.41, 0.44, and 0.64 log10 CFU/ml, respectively (95%CI: 0.22 to 0.60, 0.24 to 0.63, 0.45 to 0.84, p < 0.001 each) compared to tests using no BDMC. Neither 100 µM MLT nor 100 µM AcO-MLT significantly affected reductions at 0 h. However, 20 µM MLT and 20 µM AcO-MLT significantly increased reductions by 0.43 log10CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.21 to 0.65, p < 0.001) and 0.32 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.10 to 0.54, p = 0.004), respectively, compared to tests without the respective photosensitizer.

At 1 h, 20, 40, 60 µM BDMC contributed to reductions of 0.55 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI 0.27 to 0.84, p < 0.001), 0.33 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.05 to 0.62, p = 0.02) and 0.91 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.63 to 1.19, p < 0.001), respectively. MLT did not contribute significantly to any reduction. AcO-MLT, however, at 20 µM contributed to decreased reductions of 0.34 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: -0.66 to -0.03, p = 0.03).

At 6 h, 20, 40 and 60 µM BDMC groups contributed to increase reductions of 0.66 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.43 to 0.90, p < 0.001), 0.50 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.27 to 0.74, p < 0.001) and 0.38 log10 CFU/ml (95%CI: 0.15 to 0.62, p = 0.001), respectively. Neither MLT nor AcO-MLT affected reductions at this time.

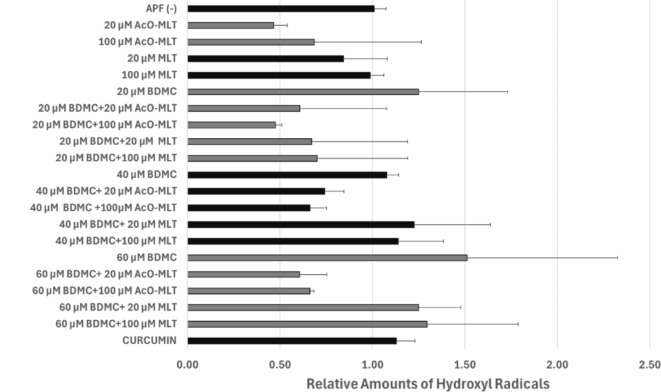

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Hydroxyl radicals

Based on fluorescence spectroscopy, no group produced statistically different hydroxyl radical levels from the probe alone. However, minute amounts of hydroxyl radicals produced by BDMC may be scavenged by either MLT or AcO-MLT (Fig. 6). Generalized linear models showed that 20 µM and 100 µM AcO-MLT significantly decreased the amount of hydroxyl radicals by 63% (CI: -80.5% to -45.2%, p < 0.001) and 62% (CI:-79.6% to -44.2%, p < 0.001), respectively, controlled for the effects of other photosensitizers. Twenty µM MLT also contributed significantly to the decrease of relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals by 20.2% (CI: -37.9% to -2.5%, p < 0.03). Although 100 µM MLT decreased the relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals by 15.9% (CI: -33.6–1.7%), the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08).

Fig. 6.

Relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals determined through fluorescence spectroscopy. Aminophenyl fluorescein probe (APF) and Curcumin were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was evaluated to assess the correlation between the relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals and antifungal effects. There was no correlation between the relative amounts of hydroxyl radicals and log10 CFU/ml reductions at 0 h (r = 0.03, p = 0.76). At 1 h, hydroxyl radicals had a low to moderate correlation with the reductions (r = 0.20, p = 0.03). However, at 6 h, hydroxyl radicals had a low to moderate negative correlation with the reductions (r = -0.23, p = 0.01).

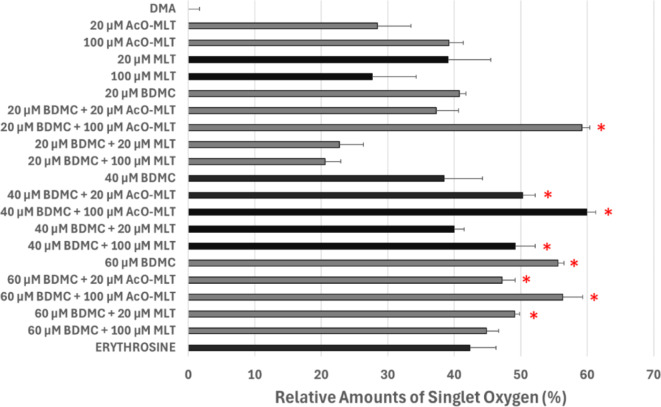

Singlet oxygen

As can be seen in Fig. 7, several groups produced significantly higher relative amounts of singlet oxygen when compared to the probe alone (median = -0.1%, IQR = -0.01–0.002%). These groups include 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT (median = 59%, IQR = 58–60%, p < 0.001), 40 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT (median = 50%, IQR = 49–51%, p = 0.002), 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT (median = 60%, IQR = 59–61%, p < 0.001), 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM MLT (median = 49%, IQR = 48–51%, p = 0.012), 60 µM BDMC (median = 55%, IQR = 55–56%, p < 0.001), 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT (median = 47%, IQR = 47–49%, p = 0.017), 60 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT (median = 56%, IQR = 55–58%, p = 0.001), and 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT (median = 49%, IQR = 49–50%, p = 0.006). Generally, there was a tendency to produce more singlet oxygen when AcO-MLT was combined with BDMC, especially with 20 µM and 40 µM BDMC.

Fig. 7.

Relative amounts of singlet oxygen determined through fluorescence spectroscopy. Dimethyl anthracene (DMA) and erythrosine were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin, MLT = melatonin, BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin.* Significant difference when compared with the negative control group (p = 0.05).

Generalized linear models showed that 100 µM MLT contributed significantly to the 6% decrease in the relative amounts of singlet oxygen (95%CI: -10.9% to -1.4%, p = 0.01). Interestingly, 100 µM AcO-MLT significantly increased the amount of singlet oxygen by 10.4% (95%CI: 5.6–15.1%, p < 0.001) compared to tests with no AcOMLT.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was evaluated. It appeared that singlet oxygen was the main driver of inhibition at all times, having moderate to substantial correlation to log10 CFU/ml reductions at 0 h (r = 0.43, p < 0.001), 1 h (r = 0.32, p < 0.001) and 6 h (r = 0.33, p < 0.001).

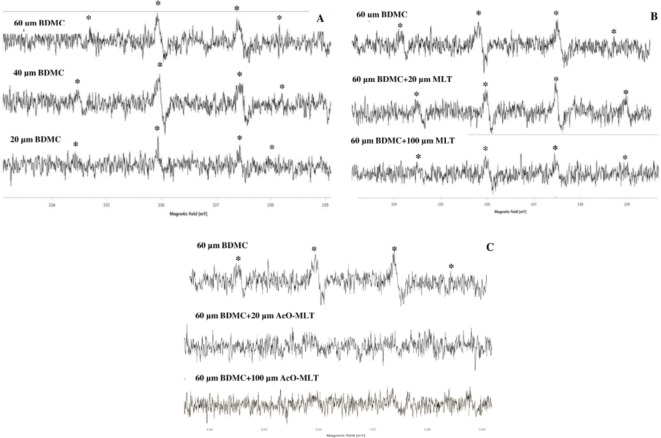

Electron spin resonance

Hydroxyl radicals

Results for hydroxyl radicals were similar to the fluorescence spectroscopy. ESR signals for hydroxyl radicals were observed in groups with BDMC (Fig. 8). As seen from the ESR signals, hydroxyl radicals were detected in groups containing BDMC, with signals becoming more apparent in a dose-dependent manner. However, in the presence of MLT and AcO-MLT, a reduction in the signals for the hydroxyl radical adducts was apparent. This suggests that these compounds have an ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals.

Fig. 8.

Electron Spin Resonance signals for hydroxyl radical. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin, MLT = melatonin, AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin (A) BDMC group. 60 µM BDMC alone compared to 60 µM BDMC combined with MLT (B) and AcO-MLT (C). *ESR signal of DMPO-OH adduct.

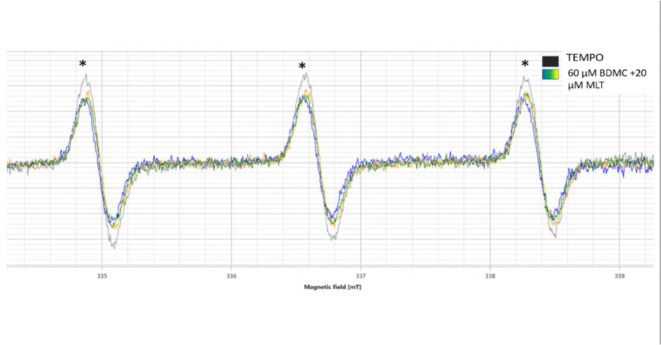

Singlet oxygen

The loss of ESR signal intensity of TEMPO (increased singlet oxygen) was detected only in the rection of 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT. These results confirmed the production of ROS in this reaction (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Electron Spin Resonance signals for singlet oxygen detection for 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT. BDMC = bisdemethoxycurcumin., MLT = melatonin, TEMPO probe, *ESR signal of TEMPO.

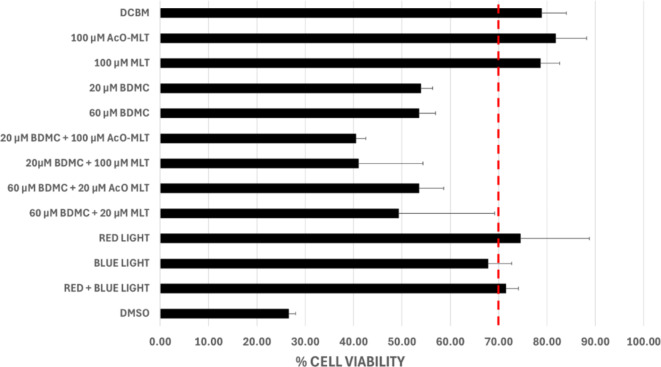

Cell viability tests

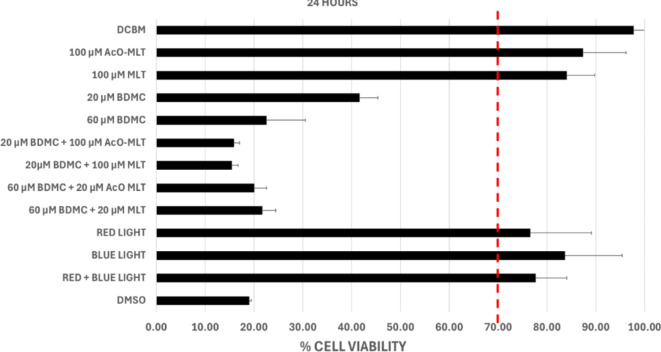

The results indicated that in groups subjected to photodynamic therapy (PDT) with 100 µM acetyl-melatonin and 100 µM melatonin alone, the median percentage viabilities were 81.8% (IQR = 78.3–84.8%), and 78.6% (IQR = 76.2–80.2%) respectively, at 1 h post-treatment (Fig. 10). At 6 h post-treatment (Fig. 11), the median percentage viabilities were 93.7% (IQR = 92.0–98.9%) and 85.0% (IQR = 76.3–90.3%), respectively. At 24 h post-treatment (Fig. 12), percentage viabilities were 87.3% (IQR = 81.2–90.1%) and 84.0% (IQR = 83.6–89.4%). These percentages exceeded the ISO standard 10,993 of 70% viability and were comparable to the samples not exposed to treatment. In contrast, none of the groups treated with either 20 µM or 60 µM bisdemethoxycurcumin alone or in combination with MLT or AcO-MLT reached the percent viability threshold at any time.

Fig. 10.

Median % Cell Viability of test groups at 1 h. Dermal Cell Basal Medium (DCBM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin, MLT = melatonin, BDCM = bisdemethoxycurcumin. Red horizontal line = ISO Standard for cell viability (70%).

Fig. 11.

Median % Cell Viability of test groups at 6 h. Dermal Cell Basal Medium (DCBM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin, MLT = melatonin, BDCM = bisdemethoxycurcumin. Red horizontal line = ISO Standard for cell viability (70%).

Fig. 12.

Median % Cell Viability of test groups at 24 h. Dermal Cell Basal Medium (DCBM) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. AcO-MLT = acetyl-melatonin, MLT = melatonin, BDCM = bisdemethoxycurcumin. Red horizontal line = ISO Standard for cell viability (70%).

For the light-only groups, all sample groups remained above the viability threshold, except for the blue-light-only group at 1 h after treatment which showed a median cell viability of 67.8% (IQR = 68.0–70.9%), which was slightly below the standard.

Discussion

This study is among the first to demonstrate that higher concentrations of BDMC produced more singlet oxygen, which was moderately and substantially correlated to candidal inhibition at all time points. Hydroxyl radicals had low-moderate correlation with inhibition after 1 h, while a negative correlation was observed at 6 h. Hence, further studies to elucidate this issue are crucial. This study also observed that addition of AcO-MLT increased singlet oxygen production and resulted in relatively higher inhibition at 0 and 6 h post-treatment, consistent with the results of Maharaj et al. (2005), demonstrating that irradiating melatonin with optimum light can lead to the generation of singlet oxygen8.

For photodynamic therapy to be effective, the PS must be absorbed by the target cells2. The response of C. albicans, unlike bacteria, is less strictly controlled by structural factors22. The pre-irradiation time of 20 min allows for the absorption of the PS by the fungi prior to light exposure. Following the uptake of the photosensitizers and irradiation using the appropriate light source, the structures adjacent to the photosensitizers are exposed to the ROS produced22. Singlet oxygen can cause cell membrane destruction, enzyme inactivation, receptor dysfunction and DNA damage23. Hydroxyl radicals have also been shown to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in C. albicans24. Hypothetically, there should be an increase in C. albicans inhibition when two types of ROS are utilized. In this study, insignificant amounts of hydroxyl radicals were produced. However, it must be noted that the photosensitizers were combined and irradiated with blue and subsequently red light. The unreacted MLT or AcO-MLT might have acted as a scavenger of hydroxyl radicals, especially at higher concentrations. Curcuminoids also have antioxidant capabilities and can scavenge the produced ROS25. Thus, the optimum ratio of light dose to the amount of photosensitizers is crucial to ensure no photosensitizers remain unreacted to achieve effective amounts of ROS. Reactive oxygen species are also short-lived, with half-lives in the microsecond to nanosecond range. Hydroxyl radicals have even shorter halflives in biological systems [26]. This supports immediate action of PDT against C. albicans, which is seen at the 0-hour time point, where the lowest concentrations of BDMC and acetyl-melatonin resulted in greater reduction compared to the other groups with higher concentrations of both PS. As demonstrated in this study, addition of acetyl-melatonin increased singlet oxygen production. Therefore, even though the 20 µM BDMC concentration is relatively low, addition of a low concentration of acetyl-melatonin increased the singlet oxygen production, resulting in greater C. albicans inhibition. It is plausible that using lower concentrations of both PS may result in more effective immediate antifungal effects through minimized ROS scavenging. In future experiments, it might be more effective to begin by introducing one PS, irradiating it, and then promptly adding a second PS and irradiating it with a different wavelength. This approach is expected to enhance ROS production, and thereby possibly enhance candidal inhibition.

Generally, the singlet oxygen produced by this protocol resulted in moderate to substantial correlations with C. albicans inhibition at all time points. Hydroxyl radicals, however, showed a different pattern. There was a positive, low-to-moderate correlation with C. albicans inhibition at 1 h, but a negative, low-to-moderate correlation after 6 h. Effective reduction of C. albicans at 0 h by a combination of 20µM BDMC + 20µM AcO-MLT and 1 h by a combination of 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT could be due to the synergistic effect of both types of ROS, with MLT being a weaker scavenger of hydroxyl radicals.

Interestingly, after 6 h, C. albicans inhibition is still apparent albeit not significantly different from the control. As seen in Figs. 4 and 20 µM BDMC with either 100 µM AcO-MLT or 100 µM MLT had relatively higher inhibition compared to other groups. When comparing within the above-mentioned groups over time, there was relatively higher inhibition at 6 h compared to earlier time points. The same trend can be seen in the groups treated with 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT. With the short half-life of the ROS, the documented immediate effect of the ROS is unlikely the reason for sustained C. albicans inhibition. Moreover, groups with higher PS concentrations, which were expected to yield more singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals, did not consistently result in significantly higher inhibition. Aside from the antioxidant effects of the photosensitizers, the loss of hydroxyl radicals may also be due to the fungi’s capability to detoxify the ROS through catalase and superoxide dismutases, Cta1, SOD1 and SOD527. Singlet oxygen can react with biological molecules through several mechanisms. It can also persist longer than other ROS because they are not broken down by enzymes produced by the target cells and enables it to interact with other compounds within cell systems2. Dissociation of the acetyl group from melatonin, which may have occurred later, might also contribute to singlet oxygen production. Perhaps one of the reasons that relatively higher inhibition was seen in groups treated with BDMC combined with 100 µM AcO-MLT at 6 h of treatment was not by the direct effects of singlet oxygen itself, but rather through the interaction of singlet oxygen with other compounds resulting in sustained C. albicans inhibition.

Other mechanisms unrelated to ROS production may have also contributed to cell reduction. The capability of C. albicans to form biofilms protects it from environmental challenges. This renders C. albicans less susceptible to antifungal therapy28. Even though exposure of microbes to irradiated BDMC alone did not yield sufficient inhibition, the role of BDMC should not be entirely dismissed. A study by Jordão et al. (2021) demonstrated that PDT using curcumin and phenothiazine with red LED light reduced the expression of genes associated with biofilm formation and integrity. When 40 µM curcumin was irradiated with red LED light (37.5 J/cm2), there was a reduction in genes such as Hyphal Wall Protein 1 (HWP1), Candida albicans Protein 1 (CAP1), and Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1), which are involved in adhesion, oxidative stress management, and scavenging of radicals, respectively28. Damaged biofilm integrity may render C. albicans cells more susceptible to PDT. Similar results were reported by Ma et al. (2019), where curcumin-mediated PDT on clinical isolates of C. albicans led to a reduction in genes involved in hyphal growth and virulence factor expression29.

Melatonin is also used in cancer treatment due to its pro-oxidation abilities. Essentially, melatonin, in certain physiological conditions, can stimulate oxidative stress in cancer cells. Melatonin can disrupt the mitochondrial function of cancer cells by decreasing ATP production, thereby stimulating intracellular production of ROS, which in turn promotes cell death. In some cancer cells, melatonin has been found to increase the expression of pro-apoptotic mediators and proteins30. Acetyl-melatonin is a relatively new derivative. Similar to melatonin, it was effective in protecting neuronal cells from oxidative stress10. One compound with a similar chemical structure as acetyl-melatonin, 4-hydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2- butenyl) acetophenone, was found to have antifungal capabilities and provided synergistic effects with fluconazole. When it was combined with fluconazole, 99.9% inhibition was achieved against C. albicans by inhibiting the transition of this fungi from its yeast to a hyphal form31. The antifungal efficacy of acetyl melatonin in combination with red LED in photodynamic therapy requires further investigation.

A potential explanation for the lower inhibition of C. albicans observed in the present study could be that the energy density used might have been insufficient to significantly produce the desired effects. For instance, Damrongrungruang et al.. (2023) observed a 3.5 log10 CFU/ml reduction when 40 µM BDMC + 100 mM potassium iodide was irradiated with blue LED light at a higher energy density, 90 J/cm211. In contrast, our study found that 40 µM BDMC alone or in combination with MLT or AcO-MLT, irradiated with blue and red light at a relatively lower combined energy density of 75 J/cm2, did not achieve > 3 log10 CFU/ml reduction.

Groups with BDMC, either alone or in combination with MLT or AcO-MLT, exhibited subtle cell cytotoxicity of up to 85%, particularly at longer time points. A dose-dependent cell cytotoxicity was also observed in HaCaT cells when curcumin was used as a photosensitizer and exposed to blue and red LED light with lower energy densities ranging from 1.604 to 6.538 J/cm232. Their study exposed keratinocytes co-cultured with C. albicans to 40 µM curcumin and blue LED light (440–460 nm) with an energy density of 5.28 J/cm², resulting in keratinocyte cell viabilities ranging from 50 to 75%33. The cells were more rounded, with more apoptotic bodies and cell cycle arrests. The authors observed that the protocol inhibited NF-κB activation when cells were exposed to TNF-α, along with caspase-8 and caspase-9 activation. NF-κB regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammatory responses in the skin. Caspases 8 and 9 are involved in programmed cell death. Additionally, extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK) and growth-associated kinase PKB/Akt, crucial for cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, were also downregulated. It must also be noted that the culture of keratinocytes in this study only produced a single cell layer which could explain the cells’ susceptibility to the protocol. Clinical studies using curcumin (in higher concentrations) as the photosensitizer in adjunctive photodynamic therapy for periodontal disease reported no adverse effects after treatment34,35.

While these findings hold promise, several study limitations need consideration. First, this was an in vitro study with a limited sample size, suggesting the need for larger in vitro, and subsequently, in vivo studies. ROS measurements were conducted solely with test photosensitizers, excluding their interactions with fungal cells or other cellular components, which may further explain the protocol’s antifungal properties. Future studies could assess ROS production in a cellular environment. Additionally, single power and energy density levels were used, potentially limiting ROS production. Further research could explore optimal light settings. Experimenting with various concentrations and higher light power and energy densities may yield valuable insights. Melatonin and acetyl-melatonin showed potent hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, suggesting potential benefits from sequential rather than simultaneous use of photosensitizers to maximize ROS production.

Conclusions

This study highlights the immediate antifungal effect of 20 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT and a relatively prolonged effect of 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT at 1 h post-treatment against C. albicans. Combining lower concentrations of BDMC with MLT or AcOMLT tended to yield higher inhibition. Groups with 20 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT, 40 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcO-MLT, 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT, 40 µM BDMC + 100 µM MLT, 60 µM BDMC, 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM AcOMLT, 60 µM BDMC + 100 µM AcO-MLT and 60 µM BDMC + 20 µM MLT, produced significant amounts of singlet oxygen, suggesting that addition of melatonin or acetyl-melatonin enhanced singlet oxygen production. Singlet oxygen correlated positively with C. albicans inhibition at all times. Although the test groups did not significantly produce hydroxyl radicals, they showed low to moderate positive correlation with C. albicans inhibition at 1 h and low to moderate negative correlation after 6 h. Additionally, bisdemethoxycurcumin, alone or in combination with melatonin or acetyl-melatonin, exhibited some cytotoxic effects on oral keratinocytes. Overall, this research suggests that antifungal photodynamic therapy using a combination of bisdemethoxycurcumin with melatonin or acetyl-melatonin holds promise for PS treatments against C. albicans. Nonetheless, further investigations are needed to comprehensively understand the underlying mechanisms and optimize the therapeutic potential of these photosensitizers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our gratitude to Mr. Piboon Ngaonee of the Cytogenic Unit, Ms. Porada Petsuk of the Microbiology Unit of the Faculty of Dentistry and Ms. Juthamat Ratha of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, for their technical support. This research was funded by the Fundamental Fund to Melatonin Research Group, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MMD, DH, NPM, TD; Data curation: MMD, TD, NPM; Formal analysis: MMD, DH, WP, NPM, TD; Funding acquisition: TD, PP; Investigation: MMD, DH, TD, NPM; Methodology: MMD, TD, NPM; Project administration: TD; Resources: TD, PP; Supervision: TD, NPM; Validation: TD, NPM, WP; Visualization: TD, NPM: original draft: MMD, TD, PP.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundamental Fund to Melatonin Research Program, Grant number FF67 from the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund of NSRF and Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vila, T., Sultan, A. S., Montelongo-Jauregui, D. & Jabra-Rizk, M. A. Oral candidiasis: a disease of opportunity. J. Fungus. 6(1), 15 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai, T. et al. Concepts and principles of photodynamic therapy as an alternative antifungal discovery platform. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3. 10.3389/2Ffmicb.2012.00120 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calzavara-Pinton, P., Rossi, M. T., Sala, R. & Venturini, M. Photodynamic antifungal chemotherapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 3, 512–522. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01107 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castano, A. P., Demidova, T. N. & Hamblin, M. R. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part one—photosensitizers, photochemistry and cellular localization. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 4, 279–93 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C. et al. New applications of photodynamic therapy in the management of candidiasis. J. Fungus. 7(12), 1025 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayaprakasha, G. K., Jaganmohan Rao, L. & Sakariah, K. K. Antioxidant activities of curcumin, demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin. Food Chem. 98(4), 720–4. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.06.037 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanpittaya, K. et al. Inhibitory effects of erythrosine/curcumin derivatives/nano-titanium dioxide-mediated photodynamic therapy on candida albicans. Molecules. 26(9), 2405 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maharaj, D. S. et al. Melatonin generates singlet oxygen on laser irradiation but acts as a quencher when irradiated by lamp photolysis. J. Pineal Res. 38(3), 153–6. 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2004.00185.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye, E. G., Kailass, K., Sadovski, O., Beharry, A. A. A. & Green-Absorbing,. Red-fluorescent phenalenone-based photosensitizer as a theranostic agent for photodynamic therapy. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.12(8), 1295–301. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00284 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panyatip, P., Puthongking, P. & Tadtong, S. Neuroprotective and neuritogenic activities of melatonin and n-acetyl substituent derivative. Isan. J. Pharm. Sci. 11, 14–19 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damrongrungruang, T., Panutyothin, N., Kongjun, S., Thanabat, K., & Ratha, J. Combined bisdemethoxycurcumin and potassium iodide-mediated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy. Heliyon. 9(7), e17490. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17490 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szeimies RM, Matheson RT, Davis SA, Bhatia AC, Frambach Y, Klövekorn W, et al. Topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy using red light-emitting diode light for multiple actinic keratoses. Dermatol. Surg. 35(4):586–92. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01096.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dovigo, L. N., Carmello, J. C., De Souza Costa, C. A., Vergani, C. E., Brunetti, I. L., Bagnato, V. S., & Pavarina, A. C. Curcumin-mediated photodynamic inactivation of Candida albicans in a murine model of oral candidiasis. Med. Mycol. 51(3), 243–251. 10.3109/13693786.2012.714081 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quishida, C. C. C. et al. Photodynamic inactivation of a multispecies biofilm using curcumin and LED light. Lasers. Med. Sci. 31, 997–1009. 10.1007/s10103-016-1942-7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, W., Liu, Y., Wamer, W. G. & Yin, J. J. Electron spin resonance spectroscopy for the study of nanomaterial-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species. J. Food. Drug. Anal. 22(1), 49–63. 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.01.004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin, J. J., Zhao, B., Xia, Q. & Fu, P. P. Nanopharmaceutics. In Electron spin resonance spectroscopy for studying the generation and scavenging of reactive Oxygen Species by Nanomaterials (ed. Yin, J. J.) 375–400 (World Scientific, 2012). 10.1142/9789814368674_0014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes, A., Fernandes, E. & Lima, J. L. F. C. Fluorescence probes used for detection of reactive oxygen species. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 65(2–3), 45–80. 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.10.003 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price, M., Reiners, J. J., Santiago, A. M. & Kessel, D. Monitoring singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radical formation with fluorescent probes during photodynamic therapy. Photochem. Photobiol. 85(5), 1177–81. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00555.x (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao, Y. et al. Determination of singlet oxygen quantum yield of a porphyrinic metal–organic framework. J. Phys. Chem.125(13), 7392–400. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c00310 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin, Y., Yip, H. K., Samaranayake, Y. H., Yau, J. Y. & Samaranayake, L. P. Biofilm-forming ability of candida albicans is unlikely to contribute to high levels of oral yeast carriage in cases of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41(7), 2961–7. 10.1128/jcm.41.7.2961-2967.2003 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thein, Z. M., Samaranayake, Y. H. & Samaranayake, L. P. Effect of oral bacteria on growth and survival of candida albicans biofilms. Arch. Oral Biol. 51(8), 672–80. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.02.005 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donnelly, R. F., McCarron, P. A. & Tunney, M. M. Antifungal photodynamic therapy. Microbiol. Res. 163(1), 1–12. 10.1016/j.micres.2007.08.001 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C. et al. New applications of photodynamic therapy in the management of candidiasis. J. Fungus 7(12), 1025. 10.3390/jof7121025 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang, I., Lee, J., Hwang, J. H., Kim, K. & Lee, D. G. Silver nanoparticles induce apoptotic cell death in Candida albicans through the increase of hydroxyl radicals. FEBS J. 279(7), 1327–38. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08527.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nardo, L., Andreoni, A., Masson, M., Haukvik, T. & Tønnesen, H. H. Studies on curcumin and curcuminoids. XXXIX. Photophysical properties of bisdemethoxycurcumin. J. Fluoresc. 21(2), 627–635. 10.1007/s10895-010-0750-x (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tain, R. W., Scotti, A. M., Li, W., Zhou, X. J. & Cai, K. Imaging short-lived reactive oxygen species (ROS) with endogenous contrast MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 47(1), 222–9. 10.1002/jmri.25763 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer, F. L., Wilson, D. & Hube, B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 4(2), 119–128. 10.4161/viru.22913 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordão, C. C., Klein, M. I., Carmello, J. C., Dias, L. M. & Pavarina, A. C. Consecutive treatments with photodynamic therapy and nystatin altered the expression of virulence and ergosterol biosynthesis genes of a fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans in vivo. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 33, 102155. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102155 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma, J., Shi, H., Sun, H., Li, J. & Bai, Y. Antifungal effect of photodynamic therapy mediated by curcumin on Candida albicans biofilms in vitro. Photodiagnosis. Photodyn. Ther. 27, 280–7. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.015 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talib, W. H., Alsayed, A. R., Abuawad, A., Daoud, S. & Mahmod, A. I. Melatonin in cancer treatment: current knowledge and future opportunities. Molecules. 26(9), 2506 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soberón, J. R. et al. Antifungal activity of 4-hydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)acetophenone against Candida albicans: evidence for the antifungal mode of action. Antonie. Van. Leeuwenhoek. 108(5), 1047–57. 10.1007/s10482-015-0559-3 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu, T., Tian, Y., Cai, Q., Ren, Q. & Wei, L. Red light combined with blue light irradiation regulates proliferation and apoptosis in skin keratinocytes in combination with low concentrations of curcumin. PLoS. One. 10(9), e0138754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138754 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellissari CVG, Pavarina AC, Bagnato VS, Mima EGDO, Vergani CE, Jorge JH. Cytotoxicity of antimicrobial photodynamic inactivation on epithelial cells when co-cultured with Candida albicans. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 15(5), 682–90. 10.1039/c5pp00387c (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanaga, C. et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (APD) with curcumin and LED, as an enhancement to scaling and root planing in the treatment of residual pockets in diabetic patients: A randomized and controlled split-mouth clinical trial. Photodiagnosis. Photodyn. Ther. 27, 388–395. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.07.005 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hormdee, D., Rinsathorn, W., Puasiri, S. & Jitprasertwong, P. Anti-early stage of bacterial recolonization effect of Curcuma longa extract as photodynamic adjunctive treatment. Int. Dent. J. 8, 2020:8823708. 10.1155/2020/8823708 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.