Abstract

Inorganic scale formation is a common issue in multi-stage flash (MSF) desalination plants, significantly impacting operational efficiency. To address this, acid cleaning is frequently employed, but it can lead to severe corrosion of alloy components if not properly controlled with corrosion inhibitors. This study investigates the effectiveness of toluene-2,4-diisocyanate-4-(1H-imidazole-ly) aniline (TDIA) as a corrosion inhibitor for 304L stainless steel in a simulated acid cleaning solution (1M HCl and 3.5 % NaCl). A range of tests, including electrochemical analysis, weight loss measurements, and surface characterization techniques such as AFM, EDS, and SEM, were used to assess the inhibitor's performance at temperatures of 25, 45, 65, and 90 °C. At a concentration of 50 ppm, TDIA achieved inhibition efficiencies of around 90% at 25 °C and above 80% at 90 °C, demonstrating effective protection across all temperatures studied. The adsorption behavior of TDIA followed the Langmuir adsorption model, and it acted as a mixed-type inhibitor by forming a protective layer on the metal surface, which prevents corrosive agents from accessing the steel. The dual-environment testing method, simulating conditions in desalination plants, offers valuable insights into the inhibitor's practical performance, enhancing the applicability of these findings to real-world industrial scenarios.

Keywords: Scale, Descaling, Stainless steel, Electrochemistry, Weight loss

Highlights

-

•

The performance of TDIA against 304L stainless steel corrosion in a simulated acid-cleaning solution was evaluated.

-

•

TDIA performed admirably at all temperatures tested, exhibiting an efficiency of over 95 % at 50 ppm concentration.

-

•

The PDP study demonstrated that TDIA exhibited a largely mixed-type inhibition behaviour.

-

•

The adsorption behavior of TDIA was shown to conform to the Langmuir adsorption model.

1. Introduction

Approximately 97% of the water on Earth consists of salt water, found mostly in the enormous seas and oceans scattered around the universe. Fresh water accounts for only 3% of all water, of which a negligible 0.0067% is available for direct use [1,2]. Sea and brackish water desalination are among the most important ways to purify the world's water [3]. The two primary methods for desalinating water are thermal and membrane technologies. Thermal desalination methods include Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSF) and Multi-Effect Distillation (MED), while membrane technologies encompass Reverse Osmosis (RO) and Electro-dialysis/Electro-dialysis Reversal [[4], [5], [6]]. There are approximately 16,000 desalination plants worldwide, providing more than 90 million cubic meters of freshwater for daily consumption [3,7]. Multi-stage flash (MSF) distillation is a water desalination process that distills seawater by sending a portion of the water to steam in an integrated countercurrent multistage heat exchanger [8]. Approximately 20–26 % of the world's desalinated water is produced by multistage flash evaporation plants [9,10]. Different components of the MSF desalination plant are made of different alloys such as stainless steel, carbon steel, copper-nickel alloy, and titanium alloy [11,12]. Stainless steel, known for its corrosion resistance, is widely used in all the different desalination technologies. Most components in desalination plants are constructed from austenitic stainless steel from the ASTM 300 series, such as 316, 316L, 317L, 304, 304L, 321, and 347 [13,14]. One of the key operational issues affecting the long-term production performance of the desalination plants is the problem of scales [9,[15], [16], [17]]. Different components of the MSF desalination plant are made of different metals such as stainless steel, carbon steel, copper-nickel alloy, and titanium alloy [11,18]. Inorganic scale accumulation on the alloy parts' surface often decreases plant efficiency and is further intensified by scale corrosion in MSF desalination plants [19,20]. In MSF desalination plants, pickling is routinely employed for descaling purposes. The most common acid employed is hydrochloric acid; additional acids used are citric, sulfuric, and sulfamic, as well as chelating agents like ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Hydrochloric acid is often used over sulfuric acid because it produces more soluble chloride compounds than insoluble sulfates [[19], [20], [21]]. Without a corrosion inhibitor, desalination plants suffer severe corrosion because of the acid cleaning processes. Therefore, acid cleaning solutions must also contain a potent corrosion inhibitor.

It has been reported that organic compounds containing heteroatoms like sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen function as corrosion inhibitors during acid cleaning [2,12,[21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]]. A516 Grade 2 carbon steel and 304L stainless steel were tested in 5% HCl at 25–93 °C using a commercial formulation containing ketoamines, isopropyl alcohol, and propargyl alcohol. [28]. The formulation's optimal concentration at room temperature was 2% by volume, where it inhibited corrosion on carbon steel by 90% and stainless steel by 87.5%. However, the formulation did not provide any protection for carbon steel up to 93 °C. The formulation is not a green inhibitor for acid cleaning because it contains propargyl which is very toxic and harmful [29,30]. The effectiveness of the cationic surfactant benzethonium chloride in inhibiting corrosion of 316L stainless steel in 1 M H2SO4 solution was studied by Deyab [18]. The stainless steel surface's inadequate covering at concentrations below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) was identified as the underlying cause for the inhibitor's lower inhibition efficiency. Despite the effective coverage of the surface by a single monolayer of the inhibitor at concentrations above the CMC, at the CMC, the inhibitor performance was not significantly enhanced. An investigation was conducted by Markhali et al. [31] to determine the effectiveness of benzotriazole and benzothiazole in inhibiting 316 austenitic stainless steel corrosion in a solution of 1M HCl for a duration of 4 h at 25 °C using electrochemical techniques. The inhibitors were reported to exhibit anodic inhibition behavior with high inhibition efficiency. While benzotriazoles are considered to have low toxicity and pose minimal health risks, they can also cause physical changes in various plant species [32], as well as having a harmful impact on aquatic habitats [33]. Furthermore, metabolites of hydroxylamines which have the potential to be carcinogenic and mutagenic, are formed during the metabolism of benzothiazole by a ring-opening process [34].

To be deemed environmentally friendly and green, a corrosion inhibitor must be nontoxic, biodegradable, and/or have an LD50 value larger than 300 mg/kg. This study examined the effectiveness of the organic compound toluene-2,4-diisocyanate-4-(1H-imidazole-ly) aniline (TDIA) produced from the reaction of tolylene-2,4-diisocyanate and 4-(1H-imidazole-ly)aniline in a 1:2 mol ratio. Toluene-2,4-diisocyanate has an oral LD50 of 5800 mg/kg. While 4-(1H-imidazole-ly)aniline is rated under category 4 for oral, dermal and inhalation toxicity, and is said to be practically non-toxic and non-irritant. 4-(1H-imidazole-ly)aniline is also non-persistence and show no bioaccumulation [35]. The performance of the synthesized compound against the corrosion of stainless steel 304L in a mixed solution of 1M HCl - 3.5% NaCl under static condition simulating acid cleaning of MSF desalination plant was evaluated employing the electrochemical and weight loss measurement methods at temperatures of 25, 45, 65 and 90 °C. SEM/EDS and atomic force microscope techniques were also used to analyze the morphology of the immersed steel surface and the effect of adsorbed inhibitor molecules on the steel surface morphology. Existing studies often explore conventional organic inhibitors such as thiols, amines, or benzimidazoles. By introducing a novel matrix based on diisocyanate-imidazole, our manuscript expands the collection of corrosion inhibitors with unique chemical properties that offer improved performance, particularly under the harsh conditions of acid cleaning. Many of the previous studies investigate inhibitors in either acidic or saline environment individually, but our study takes a more realistic approach by mixing the two. This dual-environment technique provides useful insights about the inhibitor's performance under conditions that are more representative of the real issues experienced in desalination plants, providing practical applicability that is frequently lacking in previous experiments.

2. Experimental procedure

2.1. Reagents and materials

Tolylene-2,4-diisocyanate, 4-(1H-imidazole-ly)aniline, acetic acid, acetonitrile, sodium chloride, hydrochloric acid (37 % w/v), stainless steel 304L.

2.2. TDIA synthesis and characterization

2.2.1. TDIA synthesis

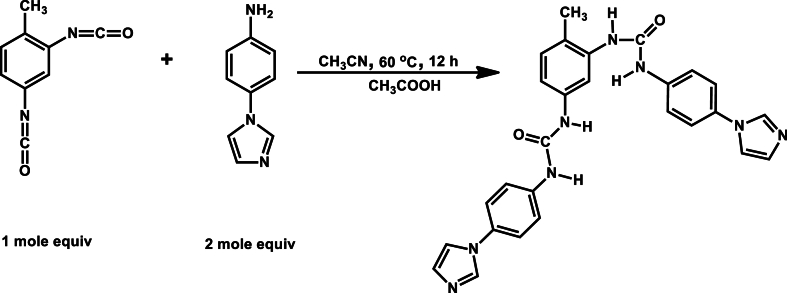

In a typical synthesis (Fig. 1), toluene-2,4-diisocyanate (0.01 mol, 1.742 g) was dissolved in 200 ml acetonitrile, once dissolved 4-(1H-imidazole-1-yl)aniline (0.02 mol, 3.184 g) was added and the reaction mixture was heated to 60 °C and stirred for 12 h [36]. A few drops of acetic acid were added to catalyze the reaction. After the designated time passed, the solid product was filtered and washed several times with acetonitrile and dried at 70 °C overnight to get a white solid powder (yield: 4.567 g, 93 %).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of TDIA synthesis.

2.2.2. Characterization of TDIA

TDIA was characterized using FTIR, 1H-, and 13C NMR characterization techniques. Using a Smart iTR NICOLET iS10 FTIR spectrometer, the FTIR spectrum was acquired at a frequency range of 400–4000 cm−1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1. For the NMR, TDIA was firstly dissolved in deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the 1H and 13C NMR spectra were obtained using a JEOL JNM-LA500 FT NMR spectrometer.

2.3. Coupons and test solutions preparation

The stainless steel coupons used in the weight loss test were made by cutting the stainless steel sample into a dimension of 2.0 cm by 2.0 cm by 0.3 cm, offering a 10.4 cm2 exposed surface area. Whereas the steel specimens utilized in the electrochemical test were reduced in size to precisely 1 cm by 1 cm by 1 cm and secured in a mixture of epoxy and hardener offering an exposed surface area of 1 cm2. This made sure that the coupon utilized for the electrochemical experiments had an exposed surface area of 1 cm2. The test solution was made by dissolving the proper amounts of NaCl in distilled water to create an aqueous solution with a concentration of 3.5% NaCl. Next, the required volumes of concentrated HCl (37%) were diluted in an aqueous NaCl solution to yield the 1M HCl_3.5% NaCl solution. 1 g of the synthesized TDIA was dissolved in a 1000 ml of 3.5 % NaCl_1M HCl solution to yield a 1000 ppm stock solution of the inhibitor, from which six concentrations (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 ppm) of the inhibitor was prepared and their performance evaluated using the weight loss measurement and electrochemical methods.

2.4. Electrochemical measurement

Utilizing the Gamry reference 3000 galvanostat/potentiostat/ZRA, the electrochemical measurement was performed. A three-electrode cell configuration (200 ml volume capacity) was utilized, with the working electrode being a steel coupon affixed in a cold mount, the reference electrode being an Ag/AgCl electrode, and the counter electrode being graphite rod. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), potentiodynamic polarization (PDP), and linear polarization resistance (LPR) were the three distinct electrochemical measurement techniques utilized. To ensure stability prior to performing the PDP, LPR, and EIS investigations, the steel coupon was immersed completely in the test solution and the system was subjected to an open circuit potential (OCP) for 1 h. The EIS measurement was performed within a frequency range of 10 kHz–100 mHz and an amplitude of 10 mV were. For LPR measurement, a 0.125 mVs−1 scan rate and a 10 mV potential deviation from OCP were utilized. The PDP measurement was performed at a scan rate of 0.25 mVs−1 and a potential range of ±250 mV from OCP.

2.5. Weight loss measurement

The weight loss experiment was done in accordance with the established protocol outlined in ASTM G1 – 03 [37]. Pre-measured samples were placed in the test solutions (100 ml) in a glass bottle (250 ml capacity) for a full day at four specific temperatures: 25, 45, 65, and 90 °C. After 24 h, the coupons were taken out, thoroughly cleaned, washed and dried, and then reweighed. The loss in weight was obtained by subtracting the final weight from the initial weight of each specimen.

2.6. Corrosion product characterization and analysis

The surface morphology and roughness of unprotected and protected stainless steel were studied using SEM, EDS, and AFM characterization techniques. Images and energy-dispersive X-ray spectra were taken using a scanning electron microscope from JEOL (JSM-6610LV model). In contact mode, AFM spectra and data were acquired utilizing the fiber-lite MI-150 high-intensity illumination system manufactured by Dolan-Jenner Industries.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of TDIA

3.1.1. NMR analysis

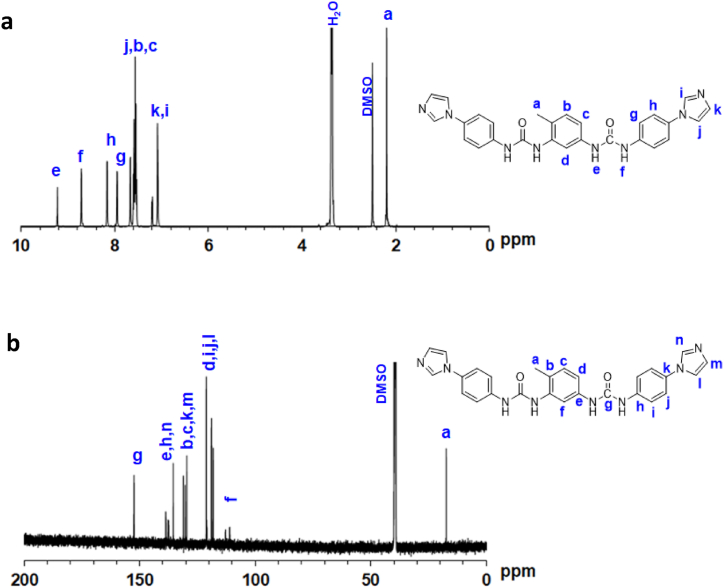

Full detailed assignment of peaks of the 1H NMR and 13C NMR of TDIA are shown in Fig. 2. The 1H NMR spectrum reveals two peaks at δ = 9.2 and 8.7 ppm which are attributed to the amine protons. The peaks found at δ = 7–8.2 ppm are attributed to the aromatic protons. A peak at δ = 2.2 ppm is attributed to the toluene moiety methyl group. The 13C NMR spectrum reveals a peak at δ = 152 ppm which is attributed to carbonyl carbon. The peaks found at δ = 110–140 ppm are attributed to the carbons of the aromatic moiety A peak at δ = 17 ppm is attributed to the carbon of the methyl group of the toluene moiety.

Fig. 2.

(a) 1H and 13C NMR spectra of TDIA.

3.1.2. FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectrum for TDIA is shown in Fig. 3. The N-H stretching vibration is represented by a band in the FTIR spectrum at about 3300 cm−1, and the two faint bands at 3126 and 3102 cm−1 depict the asymmetric and symmetric C-H vibrations, respectively. A strong band associated with the carbonyl C=O stretching vibration at about 1713 cm−1. a medium band with vibrations of C=N stretching and N-H bending at about 1642 cm−1. Two shoulder bands on either side of a very strong band at 1517 cm−1 that is attributed to aromatic C=C stretching vibrations. The vibrational mode associated with the bending of the C-H bonds in the methyl group gives rise to a distinct peak seen at a wavenumber of 1420 cm−1. A prominent spectral band is seen at 1302 cm−1, which is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the = C-N and = C-H functional groups. The presence of a band at 1201 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of the aliphatic C-N atom [38,39]. Aromatic C-H in plane bending vibrations is responsible for the bands at 1112 and 1062 cm−1, while aromatic C-H out of plane bending vibrations are responsible for the bands at 964 and 800 cm−1 [40,41]. The multiple peaks observed between the 500 to 1000 cm−1 (fingerprint region), are attributed to the out-of-plane bending vibrations of C-H bonds, particularly from aromatic rings like the toluene group, representing the C-H wagging from benzene rings and other unsaturated systems including the imidazole ring bending or deformation modes [42].

Fig. 3.

ATR-FTIR spectrum of TDIA.

3.2. Electrochemical measurement techniques

3.2.1. OCP

The direction of the potential shift may differ based on the way the electrochemical double layer (EDL) conforms to the chemistry of the electrolyte. Metal surfaces conform to the chemistry of the EDL in response to an alteration in the OCP, be it a decrease or increase. An increasing OCP indicates the development of a barrier layer that prevents additional corrosion of the metal, while a decreasing OCP indicates the formation of a permeable membrane that impedes the rate of corrosion [43]. As shown in Fig. 4, the OCP of the blank solution increased with time, whereas the OCP of various inhibited solutions fluctuated between slight increases and decreases over time. Inhibitors of the anodic or cathodic type are indicated by an 85 mV deviation of the inhibited solution OCP value in the cathodic or anodic direction from that of the blank. When the deviation in either the cathodic or anodic direction is below 85 mV, it signifies the presence of a mixed inhibitor [11]. TDIA can be said to exhibit a mixed-type behaviour, as all inhibitor concentrations exhibit cathodic shift in potential of less than 85 mV from that of the blank (Fig. 4). This indicate that the inhibitor can slow down under open circuit circumstances, both the oxidation of oxide-free iron (anodic reaction) and the discharge of hydrogen ions to form hydrogen gas on mild steel surfaces (cathodic reaction) [44].

Fig. 4.

OCP plots of TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions.

3.2.2. EIS

Fig. 5 presents the Bode modulus, Bode phase, and Nyquist plots for the inhibited and uninhibited solutions. Fig. 5a illustrates that the Nyquist curves displayed two semi-circular capacitance loops, with each loop symbolizing a unique time constant, for all solutions. The first time-constant (Rct/CPEdl) at the high-frequency regions signifies the occurrence of double layer at the interface between the steel surface and the solution. Conversely, the second time-constant (Rf/CPEf) at the medium to low frequency regions indicates a porous/passive layer formation of at the film/solution [45]. The Nyquist plots for both the blank and inhibited solutions did not intersect the Zreal axis, indicating a “degradation phenomenon in impedance spectroscopy, likely due to a delay in charge transfer caused by the buildup of corrosion products and the inhibiting film on the metal surface [46]. Two inflection points were observed in the Bode phase plots of all solutions, including the blank, as depicted in Fig. 5c. These points of inflection were consistent with the observed Nyquist loops. The observed similarity in the inhibited and blank solutions impedance curves suggests that the inhibitor acted effectively without changing the corrosion process of steel. Solid metal electrodes are characterized by imperfect Nyquist curves, which demonstrate frequency dispersion in the impedance response [47]. The observed reduction in corrosion rates in the presence of 10 ppm TDIA is indicated by the larger diameter of the Nyquist loop for TDIA in comparison to the blank. The diameter increases following an increase in TDIA concentration from 10 to 50 ppm, however, the diameter of the loop exhibited a brief decrease at 60 ppm. This upward trend indicates that TDIA molecules occupy the electric double layer at the steel–solution interface to protect the steel surface. At concentrations exceeding 50 ppm, the effectiveness of inhibition diminished as optimal concentrations of inhibitor molecules were adsorbed onto the metal surface, leading to inevitable interaction between un-adsorbed and adsorbed TDIA molecules [48]. The Bode phase angle diagram of carbon steel in the absence and presence of different concentrations of TDIA is illustrated in Fig. 5c. As a result of dispersion, phase angles are not exactly 90°. With the addition of TDIA, however, both impedance and phase angle diameter increased, indicating that it inhibits corrosion. The width of the Bode phase for inhibited solutions exhibited an increase with the concentration of TDIA from 10 to 50 ppm, followed by a decrease at 60 ppm, in a manner analogous to the Nyquist plots. The linear segment of the Bode's modulus diagrams for inhibited solutions was more conspicuous in comparison to the blank segment in Fig. 5b. This observation suggests that a shift of /Z/ towards higher values occurred. This indicates that the presence of TDIA provides improved surface coverage and protection [49,50].

Fig. 5.

(a) Nyquist, (b) Bode modulus, (c) Bode phase plots of plots of TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions, (d) employed equivalent circuit model, (e) experimental and simulated impedance plots for the blank solution, and (f) experimental and simulated impedance plots for the inhibited solution.

The impedance curves were fitted using a circuit model (Fig. 5d) comprising the following components: film resistance (Rf), charge transfer resistance (Rct), solution resistance (Rs), phase shift (n1), phase shift (n2), film constant phase element (CPEf), and double-layer constant phase element (CPEdl). The chosen equivalent circuit (EC) was deemed suitable, as evidenced by the low χ2 values shown in Table 1 and the fact that the fitting errors associated with these models are all under 0.08 % (Table 1). Fig. 5(e & f) displays typical fitted blank and TDIA inhibited solutions Nyquist graphs that illustrate the applicability of the selected EC. The comprehensive results of the impedance curve fitting process are presented in Table 1. Eqn (1) [51] was utilized to determine the percentage inhibition efficiency (%IE) of the inhibitor.

| (1) |

where & symbolises the inhibited & blank solutions polarization resistances respectively and Rp is a sum of Rf and Rct.

Table 1.

TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions EIS obtained parameters at 25 °C.

| TDIA Concn (ppm) |

Rs (Ω cm2) |

CPEf |

Rf (Ω cm2) |

CPEdl |

Rct (Ω cm2) |

Rp |

χ2 x 10−3 |

%IE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yo1 (mΩsn cm−2) | n1 | Yo2 (mΩsn cm−2) | n2 | |||||||

| Blank | 1.859 | 0.174 | 0.874 | 70.75 | 46.11 | 0.558 | 22.35 | 93.10 | 0.538 | – |

| 10 | 1.078 | 0.141 | 0.828 | 0.350 | 2.507 | 0.185 | 617.1 | 617.5 | 0.754 | 84.91 |

| 20 | 0.939 | 0.033 | 0.951 | 1.556 | 1.478 | 0.432 | 721.4 | 723.0 | 0.591 | 87.12 |

| 30 | 0.972 | 0.022 | 0.977 | 2.249 | 1.049 | 0.496 | 744.2 | 746.4 | 0.481 | 87.53 |

| 40 | 1.122 | 0.043 | 0.920 | 2.129 | 1.314 | 0.435 | 812.9 | 815.0 | 0.229 | 88.58 |

| 50 | 0.980 | 0.037 | 0.934 | 2.864 | 1.165 | 0.451 | 904.8 | 907.7 | 0.485 | 89.74 |

| 60 | 0.811 | 0.020 | 0.890 | 23.32 | 2.389 | 0.181 | 615.7 | 639.0 | 0.565 | 85.43 |

The behavior of the layer produced by the adsorbed inhibitor or corrosion product is more like that of a constant phase element (CPE) than that of a traditional capacitor. Therefore, CPE is utilized to attain a more precise data fitting [50]. By utilizing Eqn (2), the impedance of the CPE was computed [50].

| (2) |

Yo represents the constant phase element (CPE) magnitude, n signifies the phase shift the, and i stands for −1 square root, and j represents angular frequency.

The carbon steel surfaces protected by TDIA showed increased values of charge transfer resistance (Rct) compared to the unprotected (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the unprotected carbon steel exhibits the lowest Rct value (22.35 Ωcm2) while displaying the highest value of CPE magnitudes (Yo1 & Yo2). This observation can be attributed to the electrochemical reactions at the steel surface in the blank solution due to the high porosity of the loosely bound corrosion product on the unprotected steel surface. The higher charge transfer resistance of the protected steel surface, suggesting better protection by the inhibitor film [52]. This suggests that safeguarding by TDIA adsorption to the steel surface enhanced its resistance against charge transfer during carbon steel corrosion. As evidenced by the higher Rct values of the inhibited solutions compared to the blank, the adsorption of inhibitor molecules onto the protected steel surface renders it more resistant to corrosion than the unprotected steel surface. Consequently, the steel surface is protected against further mass and charge transfers. The constant phase element's (CPE) personality can be revealed via the phase shift value (n). For value of n = 0 denotes resistance, n = 1 represents capacitance, n = −1 represents inductance, and n = 0.5 represents Warburg impedance [50,53]. The fact that the value of n1 in both the blank and inhibited solutions was close to unity (Table 1) indicates that the CPE at the steel/solution interfaces is predominantly capacitive. Surface irregularity and inhomogeneity are responsible for the departure from unity, which corresponds to ideal capacitive behaviour [54]. Additionally, the ‘n’ value serves as a pointer of surface heterogeneity. A smaller n value signifies higher surface heterogeneity, while a larger value suggests the opposite [55]. Most of the inhibited solution concentrations demonstrated bigger ‘n1’ value compared to the blank, indicating a smoother and more uniform surface coating on the protected steel. On the contrary, the shielded steel demonstrated a diminished ‘n2’ value in comparison to the exposed steel, indicating heightened surface heterogeneity at the adsorbed layer interface in the solutions that were inhibited as opposed to the blank solution. The formation of a more stable inhibitor/oxide layer deposit on the protected steel surface could potentially account for this phenomenon. Furthermore, the characteristics of the metal's surface film are mirrored in the magnitude of the CPE, ‘Yo’. Lower ‘Yo’ values suggest a well adsorbed and compact surface layer [55]. Considering the ‘Yo1’ and ‘Yo2’ values of protected and unprotected steel surfaces, it's evident that the protected steel surface displays a denser and compact film compared to the unprotected steel surface corrosion product film. The random variation of Rs value may be due to variations in the concentration of ions in the electrolyte solution, poor mixing, evaporation, or contamination of the electrolyte over time or due to small temperature fluctuations in the lab, between measurements or variations in the surface condition of the working or counter electrodes, such as surface roughness, corrosion [56,57].

3.2.3. LPR

The linear polarization resistance (LPR) method is a frequently utilized rapid electrochemical technique in the evaluation of metal corrosion rates. By utilizing a potential of ±10 mV from the open circuit potential (OCP), LPR, a non-destructive technique, establishes a direct correlation between potential and current. The LPR curve fitting results for the inhibited and blank solutions are displayed in Table 2. To determine the percentage inhibition efficiency (%IE), Eqn (3) [58] was utilized.

| (3) |

where represents the polarization resistance in the absence of the inhibitor & represent the polarization resistance in the presence of the inhibitor.

Table 2.

TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions LPR obtained parameters at 25 °C.

| TDIA Concn (ppm) | Ecorr (mV vs Ag/AgCl) | Icorr (μA cm−2) | Polarization Resistance (Ω) | CR (mmyear−1) | %IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | −499.2 | 242.3 | 107.5 | 2.508 | – |

| 10 | −472.1 | 37.05 | 703.1 | 0.384 | 84.71 |

| 20 | −492.5 | 35.51 | 733.7 | 0.368 | 85.35 |

| 30 | −499.4 | 34.30 | 759.6 | 0.355 | 85.85 |

| 40 | −454.0 | 31.09 | 837.9 | 0.322 | 87.17 |

| 50 | −437.9 | 29.38 | 886.8 | 0.304 | 87.87 |

| 60 | −490.6 | 38.57 | 675.4 | 0.399 | 84.08 |

The corrosion rate was considerably reduced by the addition of TDIA in comparison to the blank. In accordance with the results obtained from the EIS analysis, it was observed that the corrosion rate exhibited a more significant decrease as the concentration of TDIA rose. The decrease peaked at the optimal concentration of 50 ppm. Furthermore, the polarization resistance of the inhibited solutions was substantially higher than the blank. This suggests that the presence TDIA improves the corrosion resistance of stainless steel.

3.2.4. PDP

The PDP technique, as opposed to the non-destructive LPR method, utilizes a more extensive polarization spectrum spanning from 200 to 400 mV. PDP provides more insights than LPR, notwithstanding its destructive nature. The primary application of PDP is to examine the impact of inhibitors on the cathodic evolution of hydrogen gas reactions and anodic metal dissolution. Fig. 6 depicts the PDP curves of the test solutions. Based on the inhibitor potential displacement from that of the blank, an inhibitor can be categorized as anodic, cathodic, or mixed. A cathodic inhibitor displays a greater than or equal to EQUA 85 mV shift in the cathodic direction, while an anodic inhibitor shows a greater than or equal to 85 mV shift in the anodic direction. A shift in either direction by less than 85 mV suggests a mixed-type inhibitor [59]. The findings from the PDP analysis mirror those of the OCP investigation, indicating that the inhibitor exhibits a mixed-type behavior, given their potential shifts of less than 85 mV in the cathodic direction from that of the blank. The βa and βc values in the presence of TDIA were all far smaller than that of the blank with the inhibitor βc value far smaller (Table 3). This also corroborate that TDIA acted as a mixed-type with cathodic predominance [60,61]. The parameters obtained from fitting the PDP curves are detailed in Table 3. The percentage inhibition efficiency (%IE) was calculated using Eqn (4) [62].

| (4) |

where & represent the current densities in the presence and absence of the inhibitor respectively.

Fig. 6.

PDP plots of TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions.

Table 3.

TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions PDP obtained parameters at 25 °C.

| TDIA Concn (ppm) | Ecorr (mV vs Ag/AgCl) | Icorr (μAcm−2) | βa (mVdec−1) | βc (mVdec−1) | CR (mmyear−1) | %IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | −486.0 | 134.0 | 108.6 | 135.1 | 1.390 | – |

| 10 | −535.0 | 15.80 | 33.20 | 46.10 | 0.163 | 88.27 |

| 20 | 535.0 | 11.00 | 26.70 | 34.80 | 0.113 | 91.87 |

| 30 | −531.0 | 7.810 | 99.15 | 55.98 | 0.081 | 94.17 |

| 40 | −528.0 | 7.580 | 20.40 | 28.90 | 0.079 | 94.32 |

| 50 | −530.0 | 2.590 | 9.400 | 12.80 | 0.027 | 98.06 |

| 60 | −507.0 | 17.80 | 29.50 | 15.10 | 0.206 | 85.18 |

In the presence of the inhibitor, the corrosion rate was significantly reduced as compared to the blank. In accordance with the outcomes of the EIS and LPR analyses, the corrosion rate exhibited a more significant decrease as the inhibitor concentration rose, culminating in its minimum at 50 ppm (optimal concentration). Furthermore, the Icorr values for the inhibitor-containing solutions were significantly lower than the blank. Lower Icorr value indicates a slower corrosion rate, suggesting the restriction of ion movement through the adsorbed inhibitor layer, thereby reducing the corrosion reaction [63]. This finding suggests that the addition of TDIA results in an enhanced resistance to corrosion by stainless steel. At the optimal concentration of 50 ppm, TDIA exhibited a corrosion inhibition efficiency of 98.06%. The significant difference in corrosion current densities of the PDP measurements as compared to the LPR techniques is that while LPR averages the corrosion rate across the whole electrode surface, PDP might offer more details regarding localized corrosion processes. PDP involves dynamic potential scanning, which can result in transitory phenomena including re-passivation and oxide film disintegration. These transitory effects may not be recorded in LPR measurements, resulting in discrepancies in corrosion current densities between the two approaches.

3.3. Weight loss measurement

As a straightforward and highly precise technique, weight loss remains one of the most effective and efficient methods for determining the rate of material corrosion and the efficacy of a corrosion inhibitor [64,65]. This method directly observes corrosion, providing insights into average corrosion rates. Employing this technique, the corrosion of stainless steel was examined at temperatures of 25, 45, 65, and 90 °C in the test solution in the presence and absence of TDIA. The outcomes from the weight loss measurements are detailed in Table 4. The corrosion rates and percentage inhibition efficiency (%IE) were computed by employing Eqns (5), (6) respectively.

| (5) |

where ‘D’ represents the stainless steel density of carbon steel, ‘A’ stands for the total exposed surface area in square centimeters (cm2), ‘W' denotes the weight loss measured in grams, and ‘T' signifies the duration of exposure in hours.

| (6) |

where CRo and CRI are the corrosion rates of the blank and TDIA-inhibited solutions respectively.

Table 4.

TDIA-inhibited and blank solutions weight loss obtained parameters at 25, 45, 65, and 90 °C temperatures.

| Temperature | TDIA Concn (ppm) | Weight Loss (g) ± standard deviation | CR (mmyear−1) | %IE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C |

Blank | 0.0269 ± 0.0007 | 1.189 | – |

| 10 | 0.0039 ± 0.0001 | 0.173 | 85.45 | |

| 20 | 0.0034 ± 0.0001 | 0.150 | 87.38 | |

| 30 | 0.0032 ± 0.0001 | 0.141 | 88.14 | |

| 40 | 0.0030 ± 0.0001 | 0.133 | 88.81 | |

| 50 | 0.0027 ± 0.0001 | 0.119 | 89.99 | |

| 60 |

0.0046 ± 0.0004 |

0.203 |

82.92 |

|

| Blank | 0.0490 ± 0.0004 | 2.166 | – | |

| 45 °C |

50 |

0.0062 ± 0.0001 |

0.274 |

87.35 |

| Blank | 0.1728 ± 0.0007 | 7.638 | – | |

| 65 °C |

50 |

0.0268 ± 0.0001 |

1.186 |

84.47 |

| Blank | 0.5868 ± 0.0062 | 32.26 | – | |

| 90 °C | 50 | 0.1124 ± 0.0006 | 4.975 | 80.82 |

The findings demonstrated a significant reduction in both the rate of weight loss and corrosion of stainless steel in the presence of TDIA. At a concentration as low as 10 parts per million (ppm), the addition of TDIA significantly reduced the corrosion rate of the steel sample from 1.189 mmyear−1 to 0.173 mmyear−1 at 25 °C. This emphasized the exceptional efficacy of TDIA as a corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel. The corrosion rate exhibited a steady decrease as the concentration of TDIA rose, eventually attaining a minimum value of 0.119 mmyear−1 at a concentration of 50 ppm. The significant inhibitory effects of TDIA can be attributed to its robust interaction with the steel surface. TDIA has several possible binding sites, including oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and aromatic rings. These sites can build strong interactions with the steel surface, effectively avoiding corrosion. This demonstrated that TDIA is an effective acid cleaning corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel component for MSF desalination plant.

Further weight loss studies at greater temperatures of 45, 65 and 90 °C were carried out to evaluate the effect of temperature on the anti-corrosion action of the optimal TDIA concentration (50 ppm). Materials corroded more quickly overall when temperature rose because the average kinetic energy of the corrosive species increased with temperature [66]. The corrosion rate of the stainless steel sample exhibited an upward trend as the temperature rose, as expected, under both the inhibited and uninhibited conditions. However, as compared to the corrosion rate observed in the absence of the inhibitor, the stainless steel sample immersed in the TDIA-inhibited solution corrosion rate was significantly lower (Table 4). This finding suggests that TDIA was successful in mitigating the corrosion of the stainless steel corrosion at the tested temperatures where TDIA exhibiting an efficiency of over 80 % at 90 °C. Nonetheless, the inhibition impact of TDIA reduced as temperature increased. The inhibition efficiency decreases from 89.99% at 25 °C to 87.35% at 45 °C to 84.47% at 65 °C to 80.82% at 90 °C. This trend aligns with a physical adsorption mechanism, which was the primary mode of TDIA adsorption onto the steel surface. Higher temperatures can eliminate these forces because they are weaker than chemical bonds. This causes some inhibitor molecules to separate from the steel surface, thus, lowering the inhibition efficacy.

3.4. Adsorption study

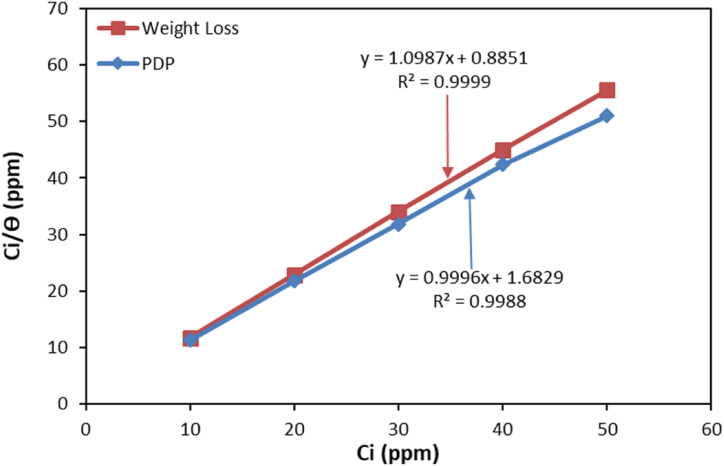

Inhibitor molecules prevent corrosion of metal surfaces through the formation of protective barriers. These barriers are generated by the adsorption of inhibitor molecules onto the metal surface created either physically, chemically, or through a mix of both, generating one or more layers of molecules. Out of all the isotherms studied, the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model was found to be the most precise. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm assumes a monolayer adsorption of inhibitor molecules that is independent and homogeneous [67]. The Langmuir adsorption hypothesis is articulated in Eqn (7). As per the Langmuir theory, a plot C/θ against C should give a linear graph with aL/KL as the slope and 1/Kad as the intercept. Weight, and PDP measurement data were utilized to plot the linear graphs (Fig. 7). Table 5 displays the derived parameters from the analysis of the plot.

| (7) |

where Kad is the adsorption equilibrium constant, and C is the inhibitor concentration; The Langmuir isotherm constants are KL and aL. The parameters KL and aL denote the maximal absorbable inhibitory concentration and the inhibitor's affinity for the metal surface, respectively, and θ, which is determined by dividing the %IE by 100, denotes the extent of surface coverage.

Fig. 7.

TDIA Langmuir adsorption isotherm plots.

Table 5.

Obtained parameters from adsorption study for TDIA adsorption.

| Compound | Technique | (kJmol−1) | Kads (Lmg−1) | Slope | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDIA | Weight Loss | −34.55 | 1.130 | 1.0987 | 0.9999 |

| PDP | −32.95 | 0.594 | 0.9996 | 0.9988 |

As shown in Eqn (8) [67], Kad is correlated to Gibbs free adsorption energy .

| (8) |

where T is temperature expressed in Kelvin (25 °C = 298.15 K) and R is molar gas constant.

When the value of value is lower than or equal to −20 kJmol-1, whereas a physiosorption adsorption process is hypothesized to take place. However, a chemisorption adsorption mechanism is assumed to operate within the range of −80 to −400 kJmol-1. A chemically enhanced physisorption mechanism is postulated for between −20 and −80 kJmol-1 [68]. The examination of the weight loss and PDP data yielded values of −34.55 and −32.95 kJmol-1 respectively. This indicates that TDIA adhered to the surface of the steel through a process of physisorption adsorption that was chemically enhanced, which is a combination of physical and chemical adsorption mechanisms. The adsorption processes are characterized by their spontaneity and stability, as denoted by negative values of .

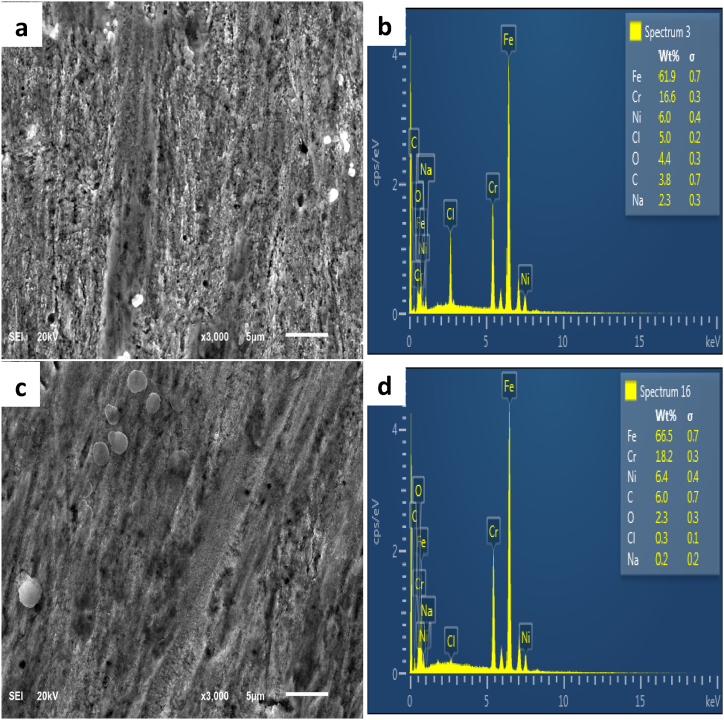

3.5. Surface analysis

SEM images of steel surfaces submerged in both inhibited and blank solutions are shown in Fig. 8 for comparison. The surface of the unprotected steel is rough, uneven, and dotted with numerous cracks and pits (Fig. 8a). In contrast, the surface of the protected steel is more even, smoother, and devoid of cracks (Fig. 8c). The observed behavior can be attributed to the development of an inhibitor coating, which successfully protects the steel surface from corrosive substances and produces a substantially smoother surface.

Fig. 8.

SEM image of (a) unprotected, (c) TDIA-protected and EDS spectra of (b) unprotected & (d) TDIA-protected 304L stainless steel.

Using EDS spectra, the elemental makeup of the steels' surface was identified. Fig. 8b and d, respectively, display the steel surface without protection and the steel surface protected by TDIA EDS spectra. Fig. 8b demonstrates that there was a significant concentration of chloride ions on the surface of the unshielded steel, 5.0 wt%, as well as a content of 61.9 wt% iron. On the protected steel surface, the iron concentration was greater (66.5 wt%) with a noticeably lower chloride amount (0.3 wt%). (Fig. 8b). The higher concentration of chloride ions on the exposed steel surface can be attributed to the porous corrosion product layer's ineffectiveness in preventing corrosion. The observed decrease in chloride concentration on the surface of the steel protected steel may be credited to the formation of an adsorbed layer of inhibitors. This layer effectively acts as a barrier, preventing the corrosive medium from meeting the steel.

An alternative technique for investigating the surface characteristics of materials at the nanoscale level from two- and three-dimensional perspectives is the use of atomic force microscopy (AFM) technology. The AFM technique has been employed to investigate the impact of inhibitor compounds on the surface characteristics of substrates when exposed to corrosive environments [[69], [70], [71], [72], [73]]. Both the 2D and 3D AFM micrographs of the steel surface submerged in the absence and presence of TDIA are shown in Fig. 9. The data for the unprotected and shielded steel surfaces' average roughness (Ra), maximum profile valley depth (Rv), and root mean square roughness (Rq) are listed in Table 6. Stainless steel submerged in the blank solution exhibited surface values of 59.2, 70.8, and 286 nm, respectively, much greater than the stainless steel submerged in the inhibited solution, which had surface values of Ra = 50.5, Rq = 70.5, and Rv = 182 nm. Comparing the unprotected stainless steel surface to the protected steel surface, the exposed steel surface suffered a severe attack from the corrosive, which is why the unprotected surface had considerably higher amplitude roughness parameter values. The unprotected steel shows a higher degree of surface roughness (Fig. 9), which makes this quite evident. The reason behind this is because the corrosive medium attacks the unprotected steel surface aggressively, while in the case of shielded steel, the adsorbed protective TDIA molecules block the medium from reaching the steel surface.

Fig. 9.

AFM 2D & 3D images of (a) unprotected and (b) TDIA-protected 304L stainless steel.

Table 6.

Unprotected and TDIA-protected carbon steel surfaces AFM roughness parameters.

| Sample |

Ra |

Rq |

Rv |

|---|---|---|---|

| (nm) | (nm) | (nm) | |

| Unprotected steel surface | 59.2 | 70.8 | 286 |

| TDIA-protected steel surface | 50.5 | 70.5 | 182 |

4. Inhibition mechanism

Physisorption and chemisorption are the two main methods by which inhibitor compounds adhere to metal surfaces. Physisorption refers to the process when inhibitor molecules are attracted to the metal surface due to electrostatic forces. Here, the protonated inhibitor molecules adsorbed on the steel surface by interacting with chloride ions initially adsorbed on the steel surface. Chemisorption, in contrast, entails the establishment of chemical interactions between the metal surface and inhibitor molecules. This phenomenon arises when delocalized orbitals and/or heteroatoms delocalized electrons are donated to the unoccupied d-orbitals of the metal. Additionally, inhibitor molecules may be adsorbed on metal surfaces by the retro-donation method, in which the orbital electrons of metal atoms are transferred to the inhibitor molecules' antibonding molecular orbitals. Considering the PDP measurements and findings from the adsorption study, it can be suggested that TDIA molecules adhere to the steel surface through a combination of physisorption and chemisorption mechanisms.

5. Conclusion

The study successfully established tolylene-2,4-diisocyanate-4-(1H-imidazole-ly)aniline (TDIA) as a highly effective corrosion inhibitor for 304L stainless steel in a simulated acid cleaning solution (1 M HCl and 3.5 % NaCl), which is of critical importance for maintaining the operational efficiency and longevity of multi-stage flash (MSF) desalination plants. The experimental results highlighted TDIA's excellent inhibition performance, achieving more than 80 % efficiency at a concentration of 50 ppm, even under challenging conditions, such as elevated temperatures of 45 °C, 65 °C, and 90 °C. The PDP studies showed that TDIA acts as a mixed-type inhibitor, affecting both the anodic and cathodic processes of the corrosion reaction. Additionally, TDIA's adsorption behavior was found to follow the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, confirming a strong interaction between the inhibitor molecules and the steel surface, leading to the formation of a stable protective layer. Surface analysis techniques such as SEM, EDS, and AFM provided clear evidence that TDIA formed a compact, uniform protective film on the stainless steel surface, which effectively blocked the access of corrosive species to the metal substrate. The EIS results further confirmed this, showing an increase in charge transfer resistance due to the presence of the protective inhibitor layer. Although our study focuses on a mixture of two corrosive environments (1M HCl and 3.5 % NaCl), the findings compare well with results from similar studies (mostly on single corrosive environment) in the literature (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison table of performance of TDIA with some compounds reported in the literature.

| Compound (Concn) |

Technique |

Coupon Type |

Corrosive Medium |

Corrosion Rate (mmyear−1) |

% IE |

Ref |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 °C | 45 °C | 65 °C | 25 °C | 45 °C | 65 °C | |||||

| Equisetum arvense extract (300 ppm) | Wt Loss | Carbon Steel | 2M HCl | 0.58 | 1.45 | – | 95.2 | 91.7 | – | [26] |

| PDP | – | – | – | 97.4 | – | – | ||||

| Ammonium-based ionic liquid (120 ppm) | Wt Loss | CuNi alloy | 3.5 % NaCl + 100 Sulfide | 1.69 | – | – | – | – | – | [24] |

| PDP | – | – | 98.4 | – | – | |||||

| Bladder wrack extract (600 ppm) | Wt Loss | C1020 CS | 1M HCl | 0.149 | – | – | 94.6 | – | – | [25] |

| PDP | – | – | – | 92.2 | – | – | ||||

| Triazole | Wt Loss | C1020 CS | 2 % HCl | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| PDP | 36.42 | – | – | 85.9 | – | – | [27] | |||

| Thiabendazole (10 mM) | Wt Loss | C1020 CS | 1 M HCl | – | – | – | – | – | – | [74] |

| PDP | 0.234 | – | – | 87.86 | – | – | ||||

| Benzethonium chloride ((0.35 mM) | Wt Loss | 316L SS | 1 M H2SO4 | – | – | – | 92.3 | – | – | [18] |

| PDP | – | – | – | 95.9 | – | – | ||||

| 4-nitro-o-phenylenediamine (600 ppm) | Wt Loss | Titanium | 1 M H2SO4 | – | – | – | 73.0 | – | – | [12] |

| PDP | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| TDIA (60 ppm) | Wt Loss | 304L SS | 1M HCl-3.5 % NaCl mix | 0.119 | 0.274 | 1.186 | 89.99 | 87.35 | 84.47 | This Work |

| PDP | 0.027 | – | – | 98.06 | – | – | ||||

NB: CS= Carbon steel; SS = Stainless steel; Wt Loss = Weight loss.

These findings have significant industrial implications, particularly for MSF desalination plants, where acid cleaning solutions are commonly used for removing scale and other deposits from equipment. The high efficiency and thermal stability of TDIA make it a promising solution for enhancing the corrosion protection of stainless steel in such harsh environments, reducing maintenance costs, equipment downtime, and extending the service life of critical components. Future work could explore the scalability of TDIA for large-scale industrial applications and its effectiveness in other corrosive environments. Also, considering the TDIA ability to prevent corrosion under static conditions, other studies could examine how well it works under dynamic conditions like the flowing environments found in oil refineries and desalination plants. This would offer more practical perspectives on its industrial use. Advanced techniques such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) can offer valuable insights into the interactions between the inhibitor and the steel surface.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kabiru Haruna: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Othman Charles S. Al Hamouz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization. Tawfik A. Saleh: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Kabiru Haruna, Email: kabiru.haruna@kfupm.edu.sa.

Othman Charles S. Al Hamouz, Email: othmanc@kfupm.edu.sa.

Tawfik A. Saleh, Email: tawfik@kfupm.edu.sa.

References

- 1.Allan Daniel J., F.A S. Biodiversity conservation in running waters, Identifying the major factors that threaten destruction of riverine species and ecosystems. Bioscience. 1993;43:32–43. doi: 10.2307/1312104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obot I.B., Meroufel A., Onyeachu I.B., Alenazi A., Sorour A.A. Corrosion inhibitors for acid cleaning of desalination heat exchangers: progress, challenges and future perspectives. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;296 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sopper W.E. Irrigation with treated sewage effluent. 1992. [DOI]

- 4.Oldfield J.W., Todd B. Technical and economic aspects of stainless steels in MSF desalination plants. Desalination. 1999;124:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0011-9164(99)00090-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Iron and Steel Institute . Nickel Institute; 2020. Role of Stainless Steels in Desalinaton - A Designers' Handbook Series No9029.www.nickelinstitute.org [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desalination in Stainless Steel A sustainable solution for the purification of salt water. 2010. www.worldstainless.org

- 7.Voutchkov N., Awerbuch L., Kaiser G., Stover R., Lienhart J. The International Desalination Association World Congress on Desalination and Water Reuse 2019. 2019. Sustainable management of desalination plant concentrate - desalination industry position paper - energy and environment committee of the international desa. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maia C.B., Silva F.V.M., Oliveira V.L.C., Kazmerski L.L. An overview of the use of solar chimneys for desalination. Sol. Energy. 2019;183:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2019.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nannarone A., Toro C., Sciubba E. Multi-stage flash desalination process: modeling and simulation. 30th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, ECOS 2017. 2017:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghaffour N., Missimer T.M., Amy G.L. Technical review and evaluation of the economics of water desalination: current and future challenges for better water supply sustainability. Desalination. 2013;309:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2012.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obot I.B., Solomon M.M., Onyeachu I.B., Umoren S.A., Meroufel A., Alenazi A., Sorour A.A. Development of a green corrosion inhibitor for use in acid cleaning of MSF desalination plant. Desalination. 2020;495 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2020.114675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyab M.A. Corrosion inhibition of heat exchanger tubing material (titanium) in MSF desalination plants in acid cleaning solution using aromatic nitro compounds. Desalination. 2018;439:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2018.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.J.O. Olsson, S.G.E. Alfonsson, Stainless Steel for Desalination Plants, Encyclopedia of Desalination and Water Resources (DESWARE) Vol.vol. II (n.d.) 170–203. https://www.eolss.net/ebooklib/sc_cart.aspx?File=D14-014 (accessed September 16, 2024).

- 14.Olsson J. Stainless steels for desalination plants. Desalination. 2005;183:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2005.02.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y., Gao Y., Li H., Yan M., Zhao J., Liu Z. Chitosan-acrylic acid-polysuccinimide terpolymer as environmentally friendly scale and corrosion inhibitor in artificial seawater. Desalination. 2021;520 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2021.115367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deyab M.A., Mohsen Q., Guo L. Aesculus hippocastanum seeds extract as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for desalination plants: experimental and theoretical studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;361 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tareemi A.A., Sharshir S.W. A state-of-art overview of multi-stage flash desalination and water treatment: principles, challenges, and heat recovery in hybrid systems. Sol. Energy. 2023;266 doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2023.112157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deyab M.A. Enhancement of corrosion resistance in MSF desalination plants during acid cleaning operation by cationic surfactant. Desalination. 2019;456:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2019.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill J.S. A novel inhibitor for scale control in water desalination. Desalination. 1999;124:43–50. doi: 10.1016/S0011-9164(99)00087-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J., Wang M., Lababidi H.M.S., Al-Adwani H., Gleason K.K. A review of heterogeneous nucleation of calcium carbonate and control strategies for scale formation in multi-stage flash (MSF) desalination plants. Desalination. 2018;442:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2018.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sona R. Moharir, Narkar B.M., Raveendran R., Patil V.A. Corrosion inhibitors in thermal desalination process: a review. JETIR. 2022;9:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Onyeachu I.B., Solomon M.M., Umoren S.A., Obot I.B., Sorour A.A. Corrosion inhibition effect of a benzimidazole derivative on heat exchanger tubing materials during acid cleaning of multistage flash desalination plants. Desalination. 2020;479 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2019.114283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saji V.S., Meroufel A.A., Sorour A.A. Corrosion and fouling control in desalination industry. 2020 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-34284-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyab M.A., Mohsen Q. Corrosion mitigation in desalination plants by ammonium-based ionic liquid. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00925-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deyab M.A., Al-Qhatani M.M. Eco-friendly Bladder wrack extract as a corrosion inhibitor for thermal desalination units during acid cleaning process. Z. Phys. Chem. 2021;235:1455–1465. doi: 10.1515/zpch-2020-1772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deyab M.A., Mohsen Q., Guo L. Theoretical, chemical, and electrochemical studies of Equisetum arvense extract as an impactful inhibitor of steel corrosion in 2 M HCl electrolyte. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06215-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wazzan N., Obot I.B., Fagieh T.M. The role of some triazoles on the corrosion inhibition of C1020 steel and copper in a desalination descaling solution. Desalination. 2022;527 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2022.115551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perdomo J.J., Conde P.R., Mahmood J., Singh P.M. Corrosion prevention during acid cleaning in digesters and evaporators. Corrosion. 2004;60:1–26. https://onepetro.org/NACECORR/proceedings-abstract/CORR04/All-CORR04/NACE-04246/115645 [Google Scholar]

- 29.OSPAR commision OSPAR Protocols on Methods for the Testing of Chemicals Used in the Offshore Oil. Offshore Industrial Series, Part B. 2006:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaussemier M., Pourmohtasham E., Gelus D., Pécoul N., Perrot H., Lédion J., Cheap-Charpentier H., Horner O. State of art of natural inhibitors of calcium carbonate scaling. A review article. Desalination. 2015;356:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2014.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markhali B.P., Naderi R., Mahdavian M., Sayebani M., Arman S.Y. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and electrochemical noise measurements as tools to evaluate corrosion inhibition of azole compounds on stainless steel in acidic media. Corrosion Sci. 2013;75:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2013.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davis David. Benzotriazole, a plant-growth regulator. Science. 1979;120(1954):989. doi: 10.1126/science.120.3128.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartwell S.I., Jordahl D.M., Evans J.E., May E.B. Toxicity of aircraft de‐icer and anti‐icer solutions to aquatic organisms. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1995;14:1375–1386. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620140813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cascioferro S., Parrino B., Carbone D., Schillaci D., Giovannetti E., Cirrincione G., Diana P. Thiazoles, their benzofused systems, and thiazolidinone derivatives: versatile and promising tools to combat antibiotic resistance. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:7923–7956. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The OSHA Hazard Communication Standard 29 CFR 1910.1200, Safety Data Sheet - the. Dow Chemical Company; 2016. https://shrinkwrapcontainments.com/Images/media/SDSShrinkFilm.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Six C., Richter F. Isocyanates, organic. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14356007.a14_611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ASTM International . vol. 90. ASTM International; 2011. pp. 1–9. (Standard Practice for Preparing , Cleaning , and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sultan M., Zia K.M., Bhatti H.N., Jamil T., Hussain R., Zuber M. Modification of cellulosic fiber with polyurethane acrylate copolymers. Part I: physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012;87:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamoussi B., Chakroun R., Timoumi A., Essalah K. Synthesis and characterization of new imidazole phthalocyanine for photodegradation of micro-organic pollutants from sea water. Catalysts. 2020;10:1–21. doi: 10.3390/catal10080906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coates J. Interpretation of infrared spectra, A practical approach. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. 2000:10815–10837. doi: 10.1002/9780470027318.a5606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chikamatsu T., Shahiduzzaman M., Yamamoto K., Karakawa M., Kuwabara T., Takahashi K., Taima T. Identifying molecular orientation in a bulk heterojunction film by infrared reflection absorption spectroscopy. ACS Omega. 2018;3:5678–5684. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith B.C. second ed. CRC Press; 2011. Fundamentals of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haruna K., Saleh T.A. Graphene oxide with dopamine functionalization as corrosion inhibitor against sweet corrosion of X60 carbon steel under static and hydrodynamic flow systems. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry Journal. 2022;920 doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2022.116589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khadom A.A. Kinetics and synergistic effect of iodide ion and naphthylamine for the inhibition of corrosion reaction of mild steel in hydrochloric acid. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2015;115:463–481. doi: 10.1007/s11144-015-0873-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haruna K., Saleh T.A. The inhibition performance of diaminoalkanes functionalized GOs against carbon steel corrosion in 15% HCl environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;448 doi: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2022.137402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haruna K., Saleh T.A., Lawal A. Acrylic acid modified indapamide-based polymer as an effective inhibitor against carbon steel corrosion in CO2-saturated NaCl with variable H2S levels: an electrochemical, weight loss and machine learning study. Surface. Interfac. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2024.105065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammed A.-R.I., Solomon M.M., Haruna K., Umoren S.A., Saleh T.A. Evaluation of the corrosion inhibition efficacy of Cola acuminata extract for low carbon steel in simulated acid pickling environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Control Ser. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-09636-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solomon M.M., Umoren S.A., Quraishi M.A., Salman M. Myristic acid based imidazoline derivative as effective corrosion inhibitor for steel in 15% HCl medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;551:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Douadi T., Hamani H., Daoud D., Al-Noaimi M., Chafaa S. Effect of temperature and hydrodynamic conditions on corrosion inhibition of an azomethine compounds for mild steel in 1 M HCl solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017;71:388–404. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2016.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazanas A.C., Prodromidis M.I. Electrochemical impedance Spectroscopy─A tutorial. ACS Measurement Science Au. 2023;3:162–193. doi: 10.1021/acsmeasuresciau.2c00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rashid K.H., Khadom A.A., Abbas S.H., Al-azawi K.F., Mahood H.B. Optimization studies of expired mouthwash drugs on the corrosion of aluminum 7475 in 1 M hydrochloric acid: gravimetrical, electrochemical, morphological and theoretical investigations. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces. 2023;13 doi: 10.1016/j.rsurfi.2023.100165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rajur S.H., Chikkatti B.S., Barnawi A.B., Bhutto J.K., Khan T.M.Y., Sajjan A.M., Banapurmath N.R., Raju A.B. Unleashing the electrochemical performance of zirconia nanoparticles on valve-regulated lead acid battery. Heliyon. 2024;10 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gerengi H., Sen N., Uygur I., Solomon M.M. Corrosion response of ultra-high strength steels used for automotive applications. Mater. Res. Express. 2019;6 doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab2178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fouda A.S., El-Desoky H.S., Abdel-Galeil M.A., Mansour D. Niclosamide and dichlorphenamide: new and effective corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in 1M HCl solution. SN Appl. Sci. 2021;3:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s42452-021-04155-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Solomon M.M., Umoren S.A., Quraishi M.A., Tripathy D.B., Abai E.J. Effect of akyl chain length, flow, and temperature on the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in a simulated acidizing environment by an imidazoline-based inhibitor. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020;187 doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Rooij D.M.R. vol. 50. 2003. (Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, Anti-corrosion Methods and Materials). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aikens D.A. Electrochemical methods, fundamentals and applications. J. Chem. Educ. 1983;60 doi: 10.1021/ed060pa25.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haruna K., Saleh T.A. The inhibition performance of diaminoalkanes functionalized GOs against carbon steel corrosion in 15% HCl environment. Chem. Eng. J. 2022;448 doi: 10.1016/J.CEJ.2022.137402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saleh T.A., Haruna K., Alharbi B. Diaminoalkanes functionalized graphene oxide as corrosion inhibitors against carbon steel corrosion in simulated oil/gas well acidizing environment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;630:591–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Z., Fadhil A.A., Chen T., Khadom A.A., Fu C., Fadhil N.A. Green synthesis of corrosion inhibitor with biomass platform molecule: gravimetrical, electrochemical, morphological, and theoretical investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;332 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Souza F.S., Spinelli A. Caffeic acid as a green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel. Corrosion Sci. 2009;51:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jasim Z.I., Rashid K.H., Al-Azawi K.F., Khadom A.A. Optimization of the corrosion inhibition performance of novel oxadiazole thione-based Schiff base for mild steel in HCl media using Doehlert experimental design. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024;160 doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chikkatti B.S., Sajjan A.M., Banapurmath N.R. The state of understanding of the electrochemical behaviours of a valve-regulated lead-acid battery comprising manganese dioxide-impregnated gel polymer electrolyte. Mater Adv. 2023;4:6192–6198. doi: 10.1039/d3ma00563a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aslam R., Mobin M., Zehra S., Aslam J. A comprehensive review of corrosion inhibitors employed to mitigate stainless steel corrosion in different environments. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;364 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.119992. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaszilcsin N., Kellenberger A., Dan M.L., Duca D.A., Ordodi V.L. Efficiency of expired drugs used as corrosion inhibitors: a review. Materials. 2023;16 doi: 10.3390/ma16165555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Afia L., Salghi R., Benali O., Jodeh S., Warad I., Ebenso E., Hammouti B. Electrochemical evaluation of linseed oil as environment friendly inhibitor for corrosion of steel in HCl solution. Port. Electrochim. Acta. 2015;33:137–152. doi: 10.4152/pea.201503137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haruna K., Saleh T.A., Quraishi M.A. Expired metformin drug as green corrosion inhibitor for simulated oil/gas well acidizing environment. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;315 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gereli G., Seki Y., Murat Kuşoǧlu I., Yurdakoç K. Equilibrium and kinetics for the sorption of promethazine hydrochloride onto K10 montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006;299:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gowri S., Umasankareswari T., Joseph Rathish R., Santhana Prabha S., Rajendran S., Al-Hashem A., Singh G., Verma C. Atomic force microscopy technique for corrosion measurement. Electrochemical and Analytical Techniques for Sustainable Corrosion Monitoring. 2023:121–140. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-15783-7.00001-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang H., Brown B., Nesic S., Pailleret A. AMPP Annual Conference & Expo. 2022. In situ atomic force microscopy study of microstructure dependent inhibitor adsorption mechanism on carbon steel; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yasakau K. Application of AFM-based techniques in studies of corrosion and corrosion inhibition of metallic alloys. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2020;1:345–372. doi: 10.3390/cmd1030017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haldhar R., Prasad D., Kamboj D., Kaya S., Dagdag O., Guo L. Corrosion inhibition, surface adsorption and computational studies of Momordica charantia extract: a sustainable and green approach. SN Appl. Sci. 2021;3:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s42452-020-04079-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fouda A.E.A.S., Abd El-Maksoud S.A., El-Sayed E.H., Elbaz H.A., Abousalem A.S. Experimental and surface morphological studies of corrosion inhibition on carbon steel in HCl solution using some new hydrazide derivatives. RSC Adv. 2021;11:13497–13512. doi: 10.1039/d1ra01405f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 74.Alamri A.H., Obot I.B. Highly efficient corrosion inhibitor for C1020 carbon steel during acid cleaning in multistage flash (MSF) desalination plant. Desalination. 2019;470 doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2019.114100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]