Abstract

Background

Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) is a radioresistance gene in esophageal cancer. This study aimed to investigate the signaling pathways that mediate the regulatory role of AKR1C3 in the radioresistance of esophageal cancer cells.

Methods

The protein levels of AKR1C3 in cancer tissue samples were compared between patients with radiosensitive and radioresistant esophageal cancer using immunohistochemical staining. AKR1C3-silenced stable KYSE170R esophageal cancer cells (KY170R-shAKR1C3) were established. Colony formation assay was employed to evaluate the radiosensitivity of cancer cells, while flow cytometry analysis was utilized to quantify reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in these cells. Additionally, Western blotting was conducted to determine protein expression levels.

Results

AKR1C3 protein exhibited significantly higher expression in radioresistant cancer tissue samples compared to radiosensitive samples. AKR1C3 silencing promoted radiosensitivity and ROS production of KYSE170R cells. At 32 h after X-ray radiation, the levels of total and phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK, and AKT proteins were significantly elevated in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells compared to untransfected KYSE170R cells. The inhibitor of AKR1C3 remarkably enhanced the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells. Conversely, treatment with either a MEK inhibitor or an AKT inhibitor significantly increased the radioresistance of KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that AKR1C3 mediates radioresistance of KYSE170R cells possibly through MAPK and AKT signaling.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13012-z.

Keywords: Radiosensitivity, Esophageal cancer, Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3, ERK, JNK

Background

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 25% [1]. Radiotherapy, in combination with chemotherapy and/or surgery, plays an important role in the management of esophageal cancer, being performed in approximately 55.4% of all patients with esophageal cancer [1, 2]. Radiotherapy activates death signaling in cancer cells via multiple mechanisms, such as DNA damage, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and stress response in the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria [3, 4]. However, radiotherapy may activate compensatory survival signaling, such as ROS scavenging and DNA repair mechanisms, in a small subset of cancer cells. These cancer cells survive radiotherapy and are responsible for radioresistance which represents a major cause of therapy failure and tumor recurrence [5]. Thus, it is essential to understand the signaling cascade in esophageal cancer cells following radiation exposure to improve radiotherapeutic efficacies.

Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) belongs to the Aldo-keto reductase superfamily, catalyzing the NADH- and NADPH-dependent reduction of ketosteroids to hydroxysteroids [6]. AKR1C3 is widely expressed in endocrine organs, playing important roles in steroid biosynthesis as well as cell proliferation and differentiation [7]. High AKR1C3 expression is associated with endocrine disorders, hormone-dependent and -independent malignancies, and chemo-/radioresistance of cancer cells [8–11]. AKR1C3 inhibition represents a promising therapeutic strategy against these disorders [6]. Previous investigations, including ours, have demonstrated that AKR1C3 exhibits a pronounced expression in radioresistant KYSE170R esophageal cancer cells. Knockdown or pharmaceutical inhibition of AKR1C3 resensitizes KYSE170R cells to radiation [2, 12]. However, the signaling pathway through which AKR1C3 contributes to radioresistance has yet to be elucidated.

The protein kinase B (AKT) pathway and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling (including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38) are at the crossroads of cell death and survival, playing critical roles in fundamental cellular processes [13, 14]. Sun et al. have reported that overexpression of AKR1C3 enhances human prostate cancer cell resistance to radiation through activation of the MAPK pathway [11]. Zhong et al. have shown that AKR1C3 mediates doxorubicin resistance in human breast cancer via PTEN loss and AKT activation [15]. Chang et al. have demonstrated that targeting AKT signaling resensitizes prostate cancer to radiotherapy [16]. Thus, we hypothesized that AKR1C3 plays a role in the radioresistance of esophageal cancer cells by modulating the MAPK and AKT signaling pathways.

This study aimed to examine the involvement of MAPK and AKT signaling pathways in AKR1C3-mediated radioresistance of KYSE170R cells. Our results may provide insights into potential therapeutic targets for overcoming AKR1C3-mediated radioresistance in esophageal cancer.

Materials and methods

Subjects and specimen collection

The present study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tangshan People’s Hospital (No. RMYY-LLKS-2021-017; Hebei, China). Prior to their participation, written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Esophageal cancer tissue samples were acquired from 65 patients diagnosed with primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma during endoscopic biopsy at Tangshan People’s Hospital between January 2010 and December 2016. All specimens were promptly processed following the removal through endoscopic biopsy. The histological confirmation of the diagnosis was conducted by two skilled pathologists. The clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with esophageal cancer

| Group | n | Percentage (%) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiosensitive | Radioresistant | Total | ||||

| Sex | Male | 25 | 20 | 45 | 69.23 | 0.432 |

| Femal | 9 | 11 | 20 | 30.77 | ||

| Age | ≤ 60 | 5 | 7 | 12 | 18.46 | 0.414 |

| >60 | 29 | 24 | 53 | 81.54 | ||

| Lesion location | Upper | 16 | 19 | 35 | 53.85 | 0.302 |

| Middle | 15 | 8 | 23 | 35.38 | ||

| Lower | 3 | 4 | 7 | 10.77 | ||

| Lesion length | ≥ 5 cm | 24 | 20 | 44 | 67.69 | 0.601 |

| <5 cm | 10 | 11 | 21 | 32.31 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | Yes | 20 | 15 | 35 | 53.85 | 0.399 |

| No | 14 | 16 | 30 | 46.15 | ||

| Stage | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.429 |

| II | 10 | 12 | 22 | 33.85 | ||

| III | 24 | 19 | 43 | 66.15 | ||

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Cell culture and treatment

Radioresistant human esophageal squamous cell line KYSE170R was kindly provided by Professor Joe Y Chang from the Department of Radiology at MD Anderson Cancer Center in TX, USA [17]. Cells were cultured in high glucose RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin. The cell culture was maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 ºC. Irradiation was performed using a 6MV X-ray linear accelerator. To investigate the roles of MAPK and AKT signaling in AKR1C3-regulated radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells, we treated KYSE170R cells with AKR1C3 inhibitor AKR1C3-IN-1 (20 μM; MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA), mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD98059 (20 μM; MedChemExpress), AKT inhibitor MK-2206 (20 μM; MedChemExpress), or JNK inhibitor SP600125 (20 μM; MedChemExpress) for 24 h, followed by exposure to different doses of 6 MV X-rays.

Gene microarray screening for differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

Parental KYSE170 cells and KYSE170R cells in the logarithmic growth phase were irradiated with a 4 Gy dose of 6MV-X-rays using a linear accelerator (Varian Corporation, USA) with a source-to-skin distance of 100 cm. Total RNA was extracted at different time points (0 h, 8 h, 24 h) before and after irradiation. RNA integrity was verified by agarose electrophoresis, and purity was assessed using a UV spectrophotometer. The RNA extracts were sent to Shanghai Biochip Co., Ltd. (China) for gene microarray screening using the Illumine-KYSE170R 6_V3 human whole genome microarray. Differential gene expression was analyzed. Illumine differential values of ≥ 20 were considered upregulated, and values of ≤ -20 were considered downregulated.

Preparation of stable AKR1C3-silenced cells

The small hairpin RNA (shRNA) target sequence for AKR1C3 was 5’-TGGATCCAAGGTCGGGCAGGAAGAG-3’. Double-stranded DNA–coding AKR1C3 shRNAs (shAKR1C3) were cloned into PMAGic1.1 lentiviral vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The vector was packaged in HEK293FT cells and collected at 72 h after transduction. KYSE170R cells were transduced with shRNA lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of 200 for 48 h and selected using 16 μg/mL puromycin. KYSE170R cells stably expressing shAKR1C3 (KYSE170R-shAKR1C3) were cultured in the complete medium supplemented with 0.6 μg/mL puromycin to maintain the stable expression of shAKR1C3.

Colony formation assay

A monolayer of KYSE170R or KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells was irradiated by 6 MV X-ray at 0, 2, 4, or 8 Gy. After irradiation, the cells were collected, seeded in 6-well plates at 500 (0 Gy group), 1,000 (2 and 4 Gy groups), or 2,000 (8 Gy group) cells/well, and cultured for 7–10 days. After fixing the cells with methanol and staining them with crystal violet, we counted the colonies containing more than 50 cells under a microscope at a magnification of ×100. The plating efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the number of colonies formed to the number of cells seeded for the 0 Gy group. The surviving fraction was calculated by dividing the number of colonies in the irradiated groups by the number of colonies in the 0 Gy group, normalized by the plating efficiency.

Flow cytometry assay

The cells were exposed to 6MV X-ray radiation at 4 Gy for 0, 8, 24, 32, or 48 h. After labeling with phosphorylated histone H2AX, the cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis to measure intracellular ROS levels. The FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used for this purpose.

Western blot analysis

The cells were exposed to 6MV X-ray radiation at 4 Gy for 0, 24, 32, or 48 h. Cell lysates were obtained using RIPA buffer. The total proteins were extracted by centrifuging the samples at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and determined using a BCA quantification assay (Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology, China). The protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Following the transfer, the membrane was blocked using 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 ºC with a primary antibody specific to ERK1/2 (Proteintech, Wuhan, Hubei, China), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), JNK (Proteintech), P-JNK (Cell Signaling Technology), AKT (Proteintech), P-AKT (Cell Signaling Technology), GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) or β-actin (Proteintech). This was followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Proteintech) for 1 h at room temperature. The protein bands on the membrane were visualized using the ECL reagent (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to quantify the protein expression levels.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

IHC staining was employed to identify and analyze the expression of AKR1C3 in cancerous tissue samples from patients with esophageal cancer. The 4-μm-thick paraffin-embedded sections underwent dewaxing in xylene and dehydration in ethanol. Subsequently, they were subjected to a 30-minute incubation with 3% H2O2. Following antigen retrieval, the sections were blocked using 10% normal goat serum and then exposed to an AKR1C3-specific primary antibody (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4 °C. The antigen-antibody complex was detected using a secondary antibody and a DAB detection kit (Boster Bio, Pleasanton, CA, USA). The scoring of the results was conducted in a blinded manner, ranging from 0 to 100%, using an Olympus microscope (bx53; Olympus, Japan) by two independent pathologists. For each section, three randomly selected fields with a minimum of 200 cells were assessed.

Staining intensity was quantified on a scale as follows: 0 (no staining), 1 (yellow), 2 (brown), and 3 (dark brown). The percentage of positive cells was categorized as follows: 1 (< 25%), 2 (25–50%), 3 (50–75%), and 4 (> 75%). The IHC score for each specimen was calculated as the product of staining intensity and grade and classified as negative (0–2) or positive (≥ 3) [18, 19].

Statistical analysis

The data were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. SPSS 13.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was utilized to perform the statistical analysis. The comparison between the two groups was accomplished using a one-way analysis of variance, followed by the Student’s t-test. The Statistical significance of the comparison of AKR1C3 expression in cancerous tissue samples between radiosensitive and radioresistant patients was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Chi-square test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

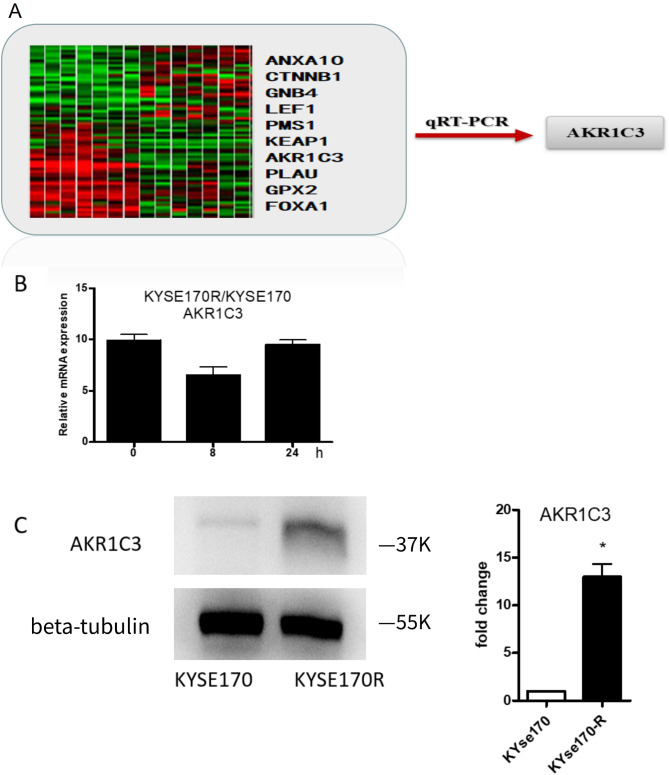

AKR1C3 is highly expressed in radioresistant esophageal cancer cells as well as in cancer tissue samples from patients

Our whole-genome microarray analysis revealed 10 DEGs with |illumine differential values| ≥ 20 in KYSE170R cells compared to parental KYSE170 cells. Among these, AKR1C3 was selected due to its substantial differences in expression across all time points (all illumine differential values ≥ 50). qRT-PCR confirmed that the expression of AKR1C3 was significantly upregulated in KYSE170R cells in comparison to the parental KYSE170 cells (Fig. 1A). By comparing with that in parental KYSE170 cells, we observed downregulation of AKR1C3 mRNA expression at 8 h after irradiation in KYSE170R cells. However, at 24 h after irradiation, the expression of AKR1C3 was restored (Fig. 1B), suggesting that exposure to long-term radiation enhances AKR1C3 expression. The results from Western blot analysis further confirmed a significant increase in the protein level of AKR1C3 in KYSE170R cells when compared to parental KYSE170 cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Aldo-keto reductase family1 member C3 (AKR1C3) was upregulated in radioresistant esophageal cancer cells. (A) Whole-genome microarray analysis was performed to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in KYSE170R cells compared to parental KYSE170 cells. The heatmap displays the expression levels of the 10 DEGs identified with |Illumina differential values| ≥ 20. AKR1C3 was selected for further validation due to its substantial differences in expression across all time points (all Illumina differential values ≥ 50). The red arrow indicates the subsequent verification of AKR1C3 expression using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). (B) KYSE170R and KYSE170 cells were irradiated for 8–24 h. Unirradiated cells were used as a negative control. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to measure the mRNA expression of AKR1C3. (C) Western blot analysis was performed to measure protein expression of AKR1C3 in parental KYSE170 cells and KYSE170R cells. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). *P < 0.05 vs. KYSE170 cells; n = 3

To further explore the clinical significance of AKR1C3 in radioresistance of esophageal cancer, we divided the patients into radiosensitive (13 cases with completed response and 21 with partial response) and radioresistant (3 with progressive disease and 28 with stable disease) groups based on the short-term efficacy of radiotherapy (Table 2). IHC staining analysis revealed a substantial increase in AKR1C3 protein expression in radioresistant cancer tissue samples, in comparison to radiosensitive cancer tissue samples (Tables 3 and 4, Supplementary Fig. 1). However, in our study, we observed no samples falling into the 0–25% positive staining rate category. These findings collectively suggest that the upregulation of AKR1C3 expression may contribute to radioresistance in esophageal cancer.

Table 2.

Classification of esophageal cancer patients based on short-term efficacy of radiotherapy

| Group (short-term efficacy) | n | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiosensitive | complete response | 13 | 20.00 |

| partial response | 21 | 32.31 | |

| Radioresistant | progressive disease | 3 | 4.61 |

| stable disease | 28 | 43.08 | |

| Total | 65 | 100 | |

Table 3.

The association of AKR1C3 expression with short-term efficacy of radiotherapy (U test)

| Group | n | IHC score of AKR1C3 expression | Z | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–50% | 50–75% | > 75% | |||||

| Short-term efficacy | Radiosensitive | 34 | 1.750 | 3.000 | 4.500 | -2.142 | 0.032 |

| Radioresistant | 31 | 2.000 | 6.000 | 8.000 | |||

Table 4.

The association of AKR1C3 expression with short-term efficacy of radiotherapy (Chi-square test)

| Group | n | AKR1C3 expression | χ 2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||||

| Short-term efficacy | Radiosensitive | 34 | 14 | 20 | 0.839 | 0.041 |

| Radioresistant | 31 | 12 | 19 | |||

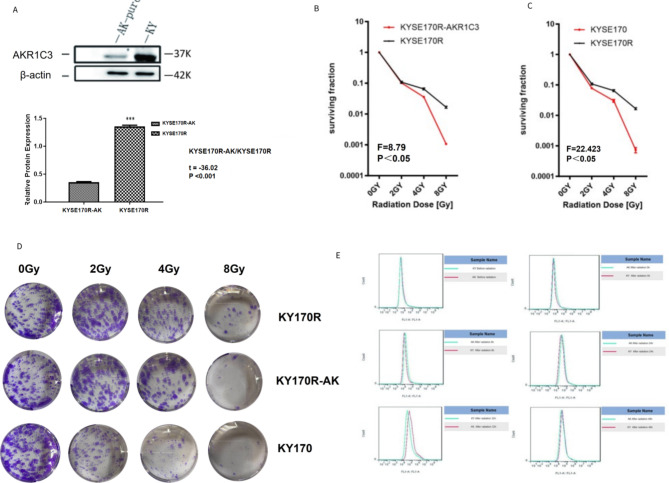

AKR1C3 silencing enhances the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells

To investigate the impact of AKR1C3 on the radioresistance of esophageal cancer, we constructed AKR1C3-silenced KYSE170R stable cells. Western blot analysis was performed to validate the successful silencing of AKR1C3 in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells (Fig. 2A). In a dose-dependent manner, radiation markedly suppressed the colony formation of both KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells. In addition, compared with KYSE170 cells, KYSE170R cells had better cell survival fraction under the same radiation conditions, showing a certain degree of radioresistance. Of note, the survival fractions of KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells were significantly reduced compared to those of KYSE170R cells when exposed to different doses of irradiation (Fig. 2B-D), suggesting that AKR1C3 silencing enhances the sensitivity of KYSE170R cells to radiation. Flow cytometry assay showed that AKR1C3 silencing significantly elevated ROS production in KYSE170R cells (Fig. 2E). ELISA demonstrated the alterations in ROS expression in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells compared to those in KYSE170R cells, especially at 32 h and 48 h following radiation exposure (Supplementary Fig. 2). These data suggest that AKR1C3 silencing resensitizes KYSE170R cells to radiation possibly by inducing oxidative stress.

Fig. 2.

AKR1C3 silencing enhanced the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells. KYSE170R cells were stably transfected with shRNA against AKR1C3 (shAKR1C3). (A) Western blot analysis was performed to measure protein expression of AKR1C3 in KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells. (B-C) Cells were exposed to 6 MV X-rays at 0, 2, 4, or 8 Gy. The irradiated cells were collected, seeded in 6-well plates at 500 (0 Gy group), 1000 (2 and 4 Gy groups), or 2000 (8 Gy group) cells/well, and cultured for 7–10 days. The numbers of colonies were counted. The plating efficiency was calculated as the ratio of the number of colonies formed to the number of cells seeded for the 0 Gy group. The surviving fraction was calculated by dividing the number of colonies in the irradiated groups by the number of colonies in the 0 Gy group, normalized by the plating efficiency. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Representative images are shown in (D). Magnification 100 ×. (E) Cells were irradiated at 4 Gy for 0, 8, 24, 32–48 h. Flow cytometry analysis was performed to measure the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species

ERK, JNK, and AKT signaling are involved in the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells

To investigate the signaling pathway underlying the involvement of AKR1C3 in the radioresistance of esophageal cancer cells, we determined the expression of ERK, JNK, and AKT in KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells in response to radiation. As shown in Fig. 3, the protein levels of both total and phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK, and AKT were significantly increased in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells at 32 h after irradiation, compared to those in KYSE170R cells, suggesting that MAPK and AKT signaling are involved in AKR1C3-mediated radioresistance of KYSE170R cells.

Fig. 3.

Alterations of ERK1/2, JNK, and AKT expression in KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells exposed to radiation. KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells were irradiated for 0, 24, 32, or 48 h. Western blot analysis was performed to measure protein levels of total and phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2, JNK, and AKT. β-actin was used as an internal reference. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. 1, 3, 5, 7: KYSE170R cells irradiated for 0, 24, 32, or 48 h; 2, 4, 6, 8: KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells irradiated for 0, 24, 32, or 48 h. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. ns, non-significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

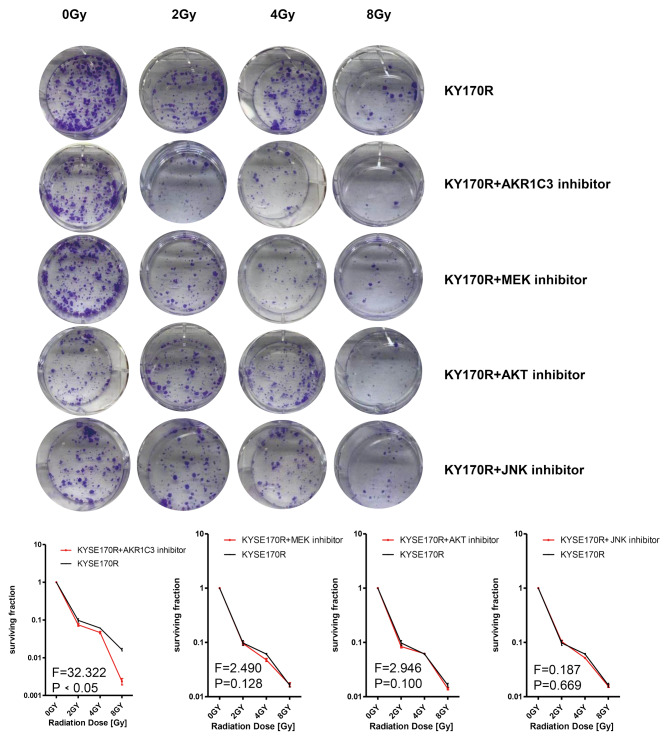

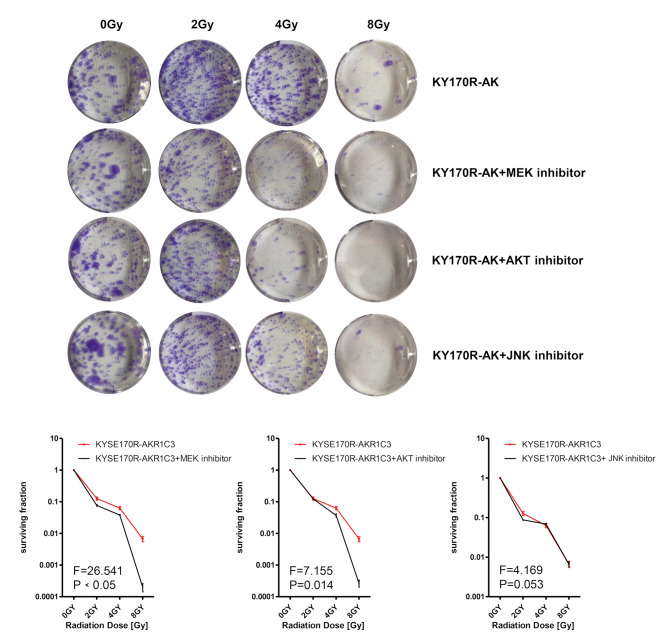

AKR1C3 regulates the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells by suppressing MEK and AKT signaling

To further investigate the roles of MAPK and AKT signaling in AKR1C3-regulated radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells, we treated KYSE170R cells with the inhibitor of AKR1C3, MEK, AKT, or JNK. The MEK inhibitor was used to selectively block the MEK-ERK pathway, as MEK is an essential kinase in the MAPK signaling pathway, acting upstream to phosphorylate and activate MAPKs such as ERK [20]. We found that only AKR1C3 inhibitor significantly resensitized KYSE170R to radiation (Fig. 4). However, in the absence of AKR1C3 expression, MEK inhibitor or AKT inhibitor significantly increased the surviving fraction of KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells (Fig. 5), suggesting that AKR1C3 regulates radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells possibly through suppressing MEK and AKT.

Fig. 4.

The effect of AKR1C3, MEK, or AKT inhibition on colony formation of KYSE170R cells. KYSE170R cells were treated with the inhibitor of AKR1C3 (AKR1C3-IN-1, 20 μM), MEK (PD98059, 20 μM), AKT (MK-2206, 20 μM), or JNK (SP600125, 20 μM) for 24 h, followed by exposure to different doses of 6 MV X-rays (0, 2, 4, and 8 Gy). The irradiated cells were collected, seeded in 6-well plates at 500 (0 Gy group), 1000 (2 and 4 Gy groups), or 2000 (8 Gy group) cells/well, and cultured for 7–10 days. The numbers of colonies were counted. The surviving fraction was calculated. Representative images are shown. Magnification 100 ×. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD

Fig. 5.

The effect of MEK or AKT inhibition on colony formation of KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells. KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells were treated with the inhibitor of MEK (PD98059, 20 μM), AKT (MK-2206, 20 μM), or JNK (SP600125, 20 μM) for 24 h, followed by exposure to different doses of 6 MV X-rays (0, 2, 4, and 8 Gy). The irradiated cells were collected, seeded in 6-well plates at 500 (0 Gy group), 1000 (2 and 4 Gy groups), or 2000 (8 Gy group) cells/well, and cultured for 7–10 days. The numbers of colonies were counted. The surviving fraction was calculated. Representative images are shown. Magnification 100×. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD

Discussion

In this study, we provided evidence of the significantly increased expression of AKR1C3 in cancer tissue samples obtained from radioresistant patients when compared to samples from radiosensitive patients. AKR1C3 silencing resensitized KYSE170R cells to radiation. Mechanistically, MAPK and AKT signaling were significantly enhanced in AKR1C3-silenced KYSE170R cells at 32 h after irradiation, compared to those in untransfected KYSE170R cells. Furthermore, inhibition of MEK, AKT, or JNK exhibited no effect on the radiosensitivity of parental KYSE170R cells. However, in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells, MEK or AKT inhibitors significantly enhanced the radioresistance of the cells. These results suggest that AKR1C3 regulates radioresensitivity of KYSE170R cells possibly through suppressing MAPK and AKT signaling. Targeting AKR1C3/MAPK/AKT signaling is a promising strategy to prevent radioresistance and restore the radiosensitivity of esophageal cancer cells.

Multiple studies have reported an association between the upregulation of AKR1C3 expression and radioresistance in various cancer types. In non-small cell lung cancer, AKR1C3 is overexpressed in radioresistant cancer cells as well as in cancerous tissue samples from patients. Knockdown of AKR1C3 restores the radiosensitivity of radioresistant lung cancer cells [21, 22]. In prostate cancer, overexpression of AKR1C3 promotes radioresistance of cancer cells through the accumulation of prostaglandin F2α and activation of the MAPK pathway [11]. Previous studies, including ours, have identified AKR1C3 as a radioresistant gene in esophageal cancer [2, 12]. In this study, our findings indicate that AKR1C3 protein expression was significantly upregulated in radioresistant esophageal cancer tissue samples compared to radiosensitive samples, further confirming that upregulation of AKR1C3 contributes to radioresistance of esophageal cancer.

Although the exact mechanisms of cancer radioresistance remain largely unknown, accumulating evidence has shown that different signaling pathways contribute to radioresistance, including PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK pathways [16]. It has been reported that irradiation activates AKT signaling in A549 lung cancer cells and that inhibition of AKT signaling overcomes the radioresistance in lung cancer cells [23, 24]. Skvortsova et al. have reported that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is activated in radioresistant prostate cancer [25]. Mehta et al. have demonstrated that AKT inhibitor promotes radiosensitivity of primary human glioblastoma stem-like cells [26]. Liu et al. have reported that AKT and ERK inhibition reverses the radioresistance of KYSE-150R esophageal cancer cells [27]. ERK pathway is involved in the radioresistance of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells [28]. Inactivation of ERK, p38, and JNK sensitizes A375 human melanoma cells to radiotherapy [29].

In our study, protein levels of P-AKT, P-JNK, and P-ERK1/2 appeared to increase in KYSE170R cells over time, peaking at 48 h post-irradiation. In contrast, in KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells, only P-ERK1/2 levels continued to rise at 48 h post-irradiation, while P-AKT levels peaked at 24 h post-irradiation, declined by 32 h, and stabilized between 32 and 48 h. Additionally, P-JNK peaked at 32 h and significantly declined by 48 h. Except for P-ERK1/2, the protein levels of all other molecules in both KYSE170R and KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells showed inverse patterns between 32 and 48 h after irradiation. The results indicate a time-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of AKT, JNK, and ERK1/2 in KYSE170R cells after radiation exposure, suggesting that these cells activate their signaling pathways as a stress response to radiation, with a peak in activation occurring at 48 h post-irradiation. In contrast, in the KYSE170R-shAKR1C3 cells, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 continues to increase even at 48 h, indicating an ongoing response to radiation. The comparable levels of P-AKT between 32 and 48 h and the decreased levels of P-JNK at 48 h suggest that AKR1C3 silencing alters cell response to radiation, particularly affecting the AKT and JNK pathways. Additionally, the observed opposite trends between the two time points for most proteins in both cell lines suggest a complex regulatory mechanism that is influenced by AKR1C3. This could reflect a temporal shift in the cellular reliance on different signaling pathways for dealing with radiation-induced damage or stress, which seems to be modulated by the presence or absence of AKR1C3. Moreover, our analysis indicated that AKR1C3 did not affect baseline levels of total AKT, JNK, ERK, and P-ERK1/2 in the cell lines studied; however, it significantly altered the phosphorylation states of AKT and JNK. This suggests that at baseline, AKR1C3 selectively modulates the phosphorylation of AKT and JNK without affecting the total protein levels in these cells.

We further found that MEK, AKT, or JNK inhibitors showed no effects on the radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells, possibly due to the weak expression of MEK, AKT, or JNK in the presence of AKR1C3. On the other hand, in AKR1C3-silenced KYSE170R cells that were sensitive to radiotherapy, MEK, AKT, or JNK inhibitor significantly enhanced the radioresistance of the cells, suggesting that AKR1C3 regulates radiosensitivity of KYSE170R cells at least partly through suppressing AKT and MEK. The AKR1C3 inhibitor significantly resensitized KYSE170R cells to radiation, indicating its potential as a therapeutic strategy to overcome radioresistance in esophageal cancer. AKR1C3 inhibitors have been investigated for their potential in treating diseases where AKR1C3 is known to be overexpressed, such as various hormone-dependent and independent cancers, including prostate and breast cancer, and metabolic disorders [30–33]. The inhibitors vary in structure and origin, including synthetic small molecules, natural products, and derivatives of existing drugs repurposed for their ability to inhibit AKR1C3 [7, 34]. Their effects in disease treatment involve modulating hormone activity, reducing tumor proliferation, and overcoming drug resistance in cancer therapies [10, 35, 36]. Our results suggest that AKR1C3 inhibitors offer a promising strategy to sensitize radioresistant esophageal cancer cells to radiation therapy.

To address potential concerns about differentiating the effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, we wish to clarify that our study specifically focused on radiation resistance. Although all patients in our cohort received concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the term “radiosensitive” describes those who responded primarily to the radiation therapy component. Previous research supports that chemotherapy can enhance radiation effects but does not necessarily change the intrinsic radiosensitivity of tumors [37, 38]. Our findings, which show high AKR1C3 expression in radioresistant tumors, further support the notion that intrinsic tumor factors play a significant role in radiation resistance, independent of concurrent chemotherapy.

In conclusion, AKR1C3 upregulation is associated with radioresistance in esophageal cancer, as evidenced by increased AKR1C3 protein levels in radioresistant KYSE170R cells and cancerous tissue samples of patients with radioresistant disease. AKR1C3 mediates the radioresistance of KYSE170R cells at least partly through MAPK, AKT, and JNK pathways. Our study demonstrated that AKR1C3 silencing altered the phosphorylation dynamics of AKT, ERK1/2, and JNK, suggesting that AKR1C3 regulates these signaling pathways in response to radiation. Specifically, JNK phosphorylation showed distinct temporal changes in AKR1C3-silenced cells, indicating its role in modulating the cellular response to radiation. Targeting AKR1C3/MAPK/AKT/JNK signaling is a promising strategy to prevent radioresistance and restore the radiosensitivity of esophageal cancer cells, offering potential therapeutic benefits in overcoming treatment resistance.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- AKR1C3

Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- JNK

C-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- shRNA

Small hairpin RNA

Author contributions

W X contributed to the conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as to drafting and critically revising the manuscript. Y X, D W, XZ H, XH H contributed to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, as well as the drafting of the manuscript. JM L and XH L contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. JW L contributed to the conception and design. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81502127], “Study on the mechanism of silencing Akr1C3 gene to reverse radiation resistance of esophageal carcinoma”. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the PUBMED repository, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Tangshan People’s Hospital (No. RMYY-LLKS-2021-017; Hebei, China). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. All methods were performed in accordance with the appropriate guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wei Xiong, Ya Xie, Dong Wang and Xiaozhi Huang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Then EO, Lopez M, Saleem S, et al. Esophageal cancer: an updated surveillance epidemiology and end results database analysis. World J Oncol. 2020;11:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng W, Lin SH. Advances in radiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang JS, Wang HJ, Qian HL. Biological effects of radiation on cancer cells. Mil Med Res. 2018;5:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA, et al. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. 2019;25:101084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim W, Lee S, Seo D et al. Cellular stress responses in radiotherapy. Cells. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Liu Y, He S, Chen Y, et al. Overview of AKR1C3: inhibitor achievements and disease insights. J Med Chem. 2020;63:11305–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeng CM, Chang LL, Ying MD, et al. Aldo-Keto reductase AKR1C1-AKR1C4: functions, regulation, and intervention for anti-cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagvekar P, Kumar P, Mangoli V, et al. DNA methylome profiling of granulosa cells reveals altered methylation in genes regulating vital ovarian functions in polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu C, Yang JC, Armstrong CM, et al. AKR1C3 promotes AR-V7 protein stabilization and confers resistance to AR-targeted therapies in advanced prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1875–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Armstrong CM, Lou W, et al. Inhibition of AKR1C3 activation overcomes resistance to abiraterone in advanced prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun SQ, Gu X, Gao XS, et al. Overexpression of AKR1C3 significantly enhances human prostate cancer cells resistance to radiation. Oncotarget. 2016;7:48050–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiong W, Zhao J, Yu H, et al. Elevated expression of AKR1C3 increases resistance of cancer cells to ionizing radiation via modulation of oxidative stress. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C et al. A comprehensive review on MAPK: a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Nitulescu GM, Van De Venter M, Nitulescu G, et al. The akt pathway in oncology therapy and beyond (review). Int J Oncol. 2018;53:2319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong T, Xu F, Xu J, et al. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) is associated with the doxorubicin resistance in human breast cancer via PTEN loss. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;69:317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang L, Graham P, Hao J, et al. Cancer stem cells and signaling pathways in radioresistance. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11002–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Komaki R, Wang L, et al. Treatment of radioresistant stem-like esophageal cancer cells by an apoptotic gene-armed, telomerase-specific oncolytic adenovirus. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanova M, Porta FM, D’Ercole M, et al. Standardized pathology report for HER2 testing in compliance with 2023 ASCO/CAP updates and 2023 ESMO consensus statements on HER2-low breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2024;484:3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad Fauzi MF, Wan Ahmad WSHM, Jamaluddin MF, et al. Allred scoring of ER-IHC stained whole-slide images for hormone receptor status in breast carcinoma. Diagnostics. 2022;12:3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo YJ, Pan WW, Liu SB, et al. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Experimental Therapeutic Med. 2020;19:1997–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie L, Song X, Yu J, et al. Solute carrier protein family may involve in radiation-induced radioresistance of non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1739–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie L, Yu J, Guo W, et al. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 may be a new radioresistance marker in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:260–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YH, Pan SL, Wang JC, et al. Radiation-induced VEGF-C expression and endothelial cell proliferation in lung cancer. Strahlenther Onkol. 2014;190:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heavey S, O’Byrne KJ, Gately K. Strategies for co-targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in NSCLC. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:445–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skvortsova I, Skvortsov S, Stasyk T, et al. Intracellular signaling pathways regulating radioresistance of human prostate carcinoma cells. Proteomics. 2008;8:4521–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta M, Khan A, Danish S, et al. Radiosensitization of primary human glioblastoma stem-like cells with low-dose AKT inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14:1171–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Yang W, Gao H, et al. Nimotuzumab abrogates acquired radioresistance of KYSE-150R esophageal cancer cells by inhibiting EGFR signaling and cellular DNA repair. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candas D, Lu CL, Fan M, et al. Mitochondrial MKP1 is a target for therapy-resistant HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:7498–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Q, Zhou Y, Lan G, et al. Sensitization of cancer cells to radiation by selenadiazole derivatives by regulation of ROS-mediated DNA damage and ERK and AKT pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pippione AC, Kovachka S, Vigato C, Bertarini L, Mannella I, Sainas S, et al. Structure-guided optimization of 3-hydroxybenzoisoxazole derivatives as inhibitors of Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) to target prostate cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2024:268:116193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Endo S, Oguri H, Segawa J, et al. Development of novel AKR1C3 inhibitors as new potential treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2020;63:10396–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Chen Y, Jiang J, et al. Development of highly potent and specific AKR1C3 inhibitors to restore the chemosensitivity of drug-resistant breast cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;247:115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rižner TL, Penning TM. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3—assessment as a new target for the treatment of endometriosis. Pharmacol Res. 2020;152:104446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kljun J, Anko M, Traven K, et al. Pyrithione-based ruthenium complexes as inhibitors of aldo–keto reductase 1 C enzymes and anticancer agents. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:11791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savić MP, Ajduković JJ, Plavša JJ, et al. Evaluation of A-ring fused pyridine D-modified androstane derivatives for antiproliferative and aldo–keto reductase 1C3 inhibitory activity. MedChemComm. 2018;9:969–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian Y, Zhao L, Wang Y, et al. Berberine inhibits androgen synthesis by interaction with aldo-keto reductase 1C3 in 22Rv1 prostate cancer cells. Asian J Androl. 2016;18:607–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu YP, Zheng CC, Huang YN et al. Molecular mechanisms of chemo- and radiotherapy resistance and the potential implications for cancer treatment. MedComm (2020). 2021;2:315–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Wang L, Correa CR, Zhao L, et al. The effect of radiation dose and chemotherapy on overall survival in 237 patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:1383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the PUBMED repository, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]