Abstract

Background

This study investigates the role of Delta Neutrophil Index (DNI), an inflammation marker, in late-onset fetal growth restriction (LO-FGR) and its prediction of composite adverse neonatal outcomes.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on 684 pregnant women (456 with normal fetal development and 228 with LO-FGR) who delivered at Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital between January 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. Composite adverse neonatal outcomes were defined as at least one of the following: 5th minute APGAR score < 7, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Results

The FGR group had significantly higher levels of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and DNI compared to controls (p < 0.05, for all). For FGR diagnosis, the DNI demonstrated the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.677, 95% CI: 0.642–0.711) with a cut-off value of > -2.9, yielding a sensitivity of 78.41%, a specificity of 52.97%, a positive likelihood ratio (+ LR) of 1.68, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.37 (p < 0.001). For predicting composite adverse neonatal outcomes in the FGR group, DNI again demonstrated superior performance with an AUC of 0.635 (95% CI: 0.598–0.670), a cut-off value of > -2.2, a sensitivity of 69.90%, a specificity of 55.36%, a + LR of 1.56, and a -LR of 0.51 (p < 0.001). NLR, PLR, and MLR had AUCs below 0.55, indicating poor discriminative ability, with none reaching statistical significance.

Conclusion

This study highlights the potential role of DNI as a promising biomarker for detecting inflammatory processes associated with LO-FGR and its complications.

Keywords: Fetal growth restriction, Delta neutrophil index, Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, Platelet to lymphocyte ratio, Monocyte to lymphocyte ratio, Perinatal outcomes

Introduction

Fetal growth is the combination of complex interactions between the genetic growth potential of the fetus and the intrauterine environment of the mother [1]. Fetal growth restriction (FGR) is diagnosed when the fetal weight estimated by ultrasound is below the 10th percentile of gestational age [2]. Impaired fetal growth not only presents a high risk of short-term complications, including low birth weight, the need for neonatal intensive care and perinatal death, but also significantly increases the likelihood of long-term consequences, such as obesity, neurological disorders, cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes [1, 3]. The causes of FGR are generally classified as maternal, fetal or placental factors. Although some causes and risk factors for FGR are well-documented—such as chromosomal abnormalities (5–20%), maternal and fetal vascular issues, and infections (5–20%)—in 40–50% of cases, a specific cause remains unidentified [4, 5].

The Delta Neutrophil Index (DNI) is a parameter that reflects the proportion of immature granulocytes (IGs) in the blood circulation [6]. These IGs, which include myelocytes, promyelocytes, and metamyelocytes, serve as precursors to neutrophils and are typically not present in circulating blood under normal conditions [7]. Elevated levels of IGs in peripheral blood have been associated with conditions such as rhinosinusitis, sepsis, acute appendicitis, pyelonephritis, pancreatitis, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome [7–9]. DNI is associated with inflammation because the production of immature neutrophils is accelerated during inflammatory conditions, leading to their rapid release from the bone marrow into the peripheral circulation, which increases DNI [7, 9]. Neutrophils have also been recognized as crucial players in chronic inflammation, consistently being recruited to sites of chronic inflammation, where they activate other immune cells, release serine proteases, and form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [10]. An increase in DNI is observed in both acute and chronic conditions characterized by increased neutrophil production [11]. Modern automated hematology analyzers have made it easier to assess IG counts and percentages (IG%) in complete blood counts [12], providing a convenient method to evaluate bone marrow function.

Emerging research has increasingly highlighted a significant link between FGR and inflammation, suggesting that inflammatory processes may play a pivotal role in the onset and progression of FGR [13, 14]. Inflammatory conditions can trigger immune responses that can disrupt placental function and nutrient transfer, leading to restriction of fetal growth [15]. This disruption can lead to restricted fetal growth, with potentially severe consequences for both short-term and long-term neonatal health. DNI, a new marker of inflammation, has shown promise in other inflammatory and infectious conditions, but its role in the context of pregnancy, particularly in cases complicated by FGR, has not been investigated to our knowledge. Understanding the potential of DNI as a diagnostic and prognostic tool, which can now be easily measured with modern automated hematology analyzers, may provide valuable information about the inflammatory mechanisms underlying FGR and offer new avenues for early intervention and management. Therefore, our study investigates the role of DNI, a marker of inflammation, in relation to late-onset FGR (LO-FGR) and its prediction of adverse neonatal outcomes.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study was conducted on pregnant women who gave birth at Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital between January 1, 2015, and June 30, 2018. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, with ethical approval obtained from the Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: 2024-02/05). Given the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital granted a waiver for informed consent. Patient data were collected from medical records and the hospital’s information management system. A total of 456 pregnant women with normal fetal development and 228 pregnant women diagnosed with LO-FGR were included in the study.

Pregnant women diagnosed with FGR at a gestational age greater than 32 weeks (late-onset FGR) were included in the study. The diagnosis of LO-FGR was based on the Delphi Consensus Criteria [2] and was identified if the abdominal circumference (AC) or estimated fetal weight (EFW) was below the 3rd percentile. Alternatively, the diagnosis was established if at least two of the following criteria were met: (1) An AC or EFW below the 10th percentile, (2) An AC or EFW crossing two quartiles, (3) Abnormal Doppler findings, such as an umbilical artery Doppler pulsatility index above the 95th percentile or a cerebro-placental ratio below the 5th percentile. The gestational age of all participants was confirmed by ultrasound based on the measurement of the crown-rump length taken between 11 and 14 weeks. The study excluded cases involving multiple pregnancies, preterm births (< 37 weeks), fetal anomalies, pregnant women with hypertension or diabetes, liver and kidney pathology, as well as maternal conditions such as cancer, hematologic, and autoimmune diseases.

The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and DNI were determined by laboratory tests at the time of diagnosis in the study group. For each LO-FGR pregnant woman, two control pregnant women with matched by maternal age and gestational age at measurement were selected and included in the analysis. The inflammatory scores were calculated as follows: NLR: neutrophil count/lymphocyte count, PLR: platelet count/lymphocyte count, MLR: monocyte count/lymphocyte count, and DNI was automatically calculated by the automatic cell analyzer. Pregnant women diagnosed with LO-FGR were planned to give birth after 37 weeks’ gestation, unless a pregnancy complication requiring earlier delivery occurred. We defined composite adverse neonatal outcomes as the presence of at least one adverse outcome: 5th minute APGAR score < 7, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.

Biochemical analysis

The DNI value in the serum was determined using an automatic cell analyzer (ADVIA 2120i Hematology System, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany). This system is a flow cytometry-based hematology analyzer that uses two independent methods for counting leukocytes, a myeloperoxidase (MPO) channel, and a lobularity/nuclear density channel. The DNI value was calculated using the following formula: DNI (%) = (the neutrophil subfraction (%) and the eosinophil subfraction (%) measured in the MPO channel by cytochemical reaction) - (the polymorphonuclear neutrophil [PMN] subfraction (%) measured in the nuclear lobularity channel by visible light beam measurements).

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 22.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA) package program was used to analyze the data. Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), while categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Normality analysis was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Independent T-test was used for normally distributed parameters, the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed parameters, and the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Values with a p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The association between hematological parameters and LO-FGR and composite adverse neonatal outcomes was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and cut-off points were calculated.

Results

A total of 228 pregnancies complicated by LO-FGR and 456 control pregnancies were included in the analysis. The maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes of the study population are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between the FGR and control groups regarding maternal age, BMI at during test, gravidity, parity, smoking status, and gestational age at the time of measurement (p > 0.05, for all). However, gestational age at delivery was significantly lower in the FGR group (37 [36–38] weeks vs. 38 [37–39] weeks, p < 0.001). The mode of delivery also differed significantly, with a higher rate of cesarean section in the FGR group (62.2% vs. 41.9%, p < 0.001). Neonatal outcomes were significantly worse in the FGR group, with lower birth weights (2174 ± 47 g vs. 3314 ± 39 g, p < 0.001), higher rates of 5th minute APGAR score (< 7) neonates (7.4% vs. 1.3%, p < 0.001), higher rates of RDS (32.4% vs. 1.1%, p < 0.001), and higher rates of NICU admission (30.7% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.001). Additionally, the composite adverse neonatal outcomes, which included low 5th minute APGAR score (< 7), RDS, and NICU admission, were more prevalent in the FGR group (34.6% vs. 3.7%, p < 0.001). (Table 1)

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics and perinatal outcomes of the study population

| FGR (n = 228) |

Control (n = 456) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 27.3 ± 5.6 | 27.1 ± 5.4 | 0.559 |

| BMI at during test (kg/m 2 ) | 27 (25–30) | 29 (26–32) | 0.054 |

| Graviditiy | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.081 |

| Parity | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–2) | 0.073 |

| Smoking | 20 (8.7) | 28 (6.1) | 0.204 |

| Gestational age at measurement (weeks) | 33.3 ± 2.4 | 34.2 ± 1.6 | 0.237 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 37 (36–38) | 38 (37–39) | < 0.001 |

| Mode of birth | <0.001 | ||

| Vaginal delivery | 86 (37.7) | 265 (58.1) | |

| Cesarean section | 142 (62.2) | 191 (41.9) | |

| Neonatal gender | 0.053 | ||

| Female | 140 (61.4) | 211 (46.5) | |

| Male | 88 (38.6) | 244 (53.5) | |

| Neonatal birth weight (grams) | 2174 ± 47 | 3314 ± 39 | < 0.001 |

| APGAR score at 1st minute | 9 (9–9) | 9 (9–9) | 0.286 |

| APGAR score at 5th minute | 10 (10–10) | 10 (10–10) | 0.170 |

| APGAR score at 5th minute < 7 | 17 (7.4) | 6 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

| RDS | 74 (32.4) | 5 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| NICU admission | 70 (30.7) | 11 (2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Composite adverse neonatal outcomes * | 79 (34.6) | 17 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Perinatal mortality | 1 (0.4) | 0 | N/A |

FGR; fetal growth restriction, BMI; body mass index, kg; kilogram, m2; square meter, RDS; respiratory distress syndrome, NICU; neonatal intensive care unit. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, median and quartiles (Q1-Q3), or number (percentage) where appropriate

* Composite adverse neonatal outcomes include presence of at least one of the adverse outcome; 5th minute APGAR score < 7, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission

The examination of inflammatory parameters is presented in Table 2. The hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and platelet counts were similar between the FGR and control groups (p > 0.05, for all). Additionally, there was no significant differences observed in white blood cell (WBC) count, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, or monocyte count between the groups (p > 0.05, for all). The FGR group had higher levels of NLR (4.59 [3.65–6.13] vs. 4.10 [3.17–5.43], p < 0.001), PLR (137.2 [110-179.7] vs. 126.6 [97.8-171.3], p = 0.006), and MLR (0.286 (0.221–0.357) vs. 0.261 (0.207–0.328), p = 0.004) compared to the control group. Additionally, DNI levels in the FGR group were significantly higher than the control group (-1.10 [-2.55 to 0.20] vs. -3.00 [-4.80 to -1.10], p < 0.001). (Table 2)

Table 2.

Examination of inflammation parameters of the study group

| FGR (n = 228) |

Control (n = 456) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.7 ± 1.5 | 11.6 ± 1.5 | 0.121 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.9 ± 4.1 | 36.5 ± 4.2 | 0.068 |

| Platelet (10 9 /l) | 234.3 ± 62.6 | 242.5 ± 68.1 | 0.102 |

| WBC (10 9 /l) | 10.2 (8.7–12) | 10.4 (8.8–12.5) | 0.157 |

| Neutrophil (10 9 /l) | 7.53 (6.43–9.43) | 7.55 (6.34–9.53) | 0.832 |

| Lymphocyte (10 9 /l) | 1.61 (1.34–1.93) | 1.82 (1.46–2.26) | 0.061 |

| Monocyte (10 9 /l) | 0.48 (0.38–0.57) | 0.49 (0.39–0.61) | 0.257 |

| NLR | 4.59 (3.65–6.13) | 4.10 (3.17–5.43) | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 137.2 (110-179.7) | 126.6 (97.8-171.3) | 0.006 |

| MLR | 0.286 (0.221–0.357) | 0.261 (0.207–0.328) | 0.004 |

| DNI (%) | -1.10 (-2.55 to 0.20) | -3.00 (-4.80 to -1.10) | < 0.001 |

FGR: Fetal growth restriction, WBC; white blood cells, NLR; neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR; platelet to lymphocyte ratio, MLR; monocyte to lymphocyte ratio, DNI, delta neutrophil index. Data are expressed as mean ± SD or median and quartiles (Q1-Q3) where appropriate

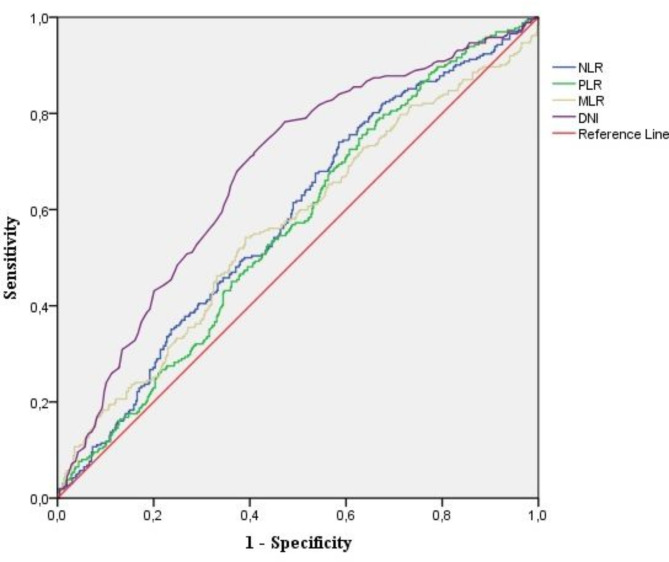

The diagnostic performance of various inflammatory markers for detecting FGR and predicting composite adverse neonatal outcomes was assessed using ROC curve analysis and is shown in Table 3. For FGR diagnosis, the DNI demonstrated the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.677, 95% CI: 0.642–0.711) with a cut-off value of > -2.9, yielding a sensitivity of 78.41%, a specificity of 52.97%, a positive likelihood ratio (+ LR) of 1.68, and a negative likelihood ratio (-LR) of 0.37 (p < 0.001). The NLR showed an AUC of 0.580 (95% CI: 0.537–0.622) with a cut-off value of > 4.31, a sensitivity of 54.20%, a specificity of 54.36%, a + LR of 1.19, and a -LR of 0.84 (p < 0.001). PLR and MLR had similar AUCs (0.562 and 0.564, respectively), indicating limited diagnostic accuracy (p < 0.05, for both). For predicting composite adverse neonatal outcomes in the FGR group, DNI again demonstrated superior performance with an AUC of 0.635 (95% CI: 0.598–0.670), a cut-off of > -2.2, a sensitivity of 69.90%, a specificity of 55.36%, a + LR of 1.56, and a -LR of 0.51 (p < 0.001). NLR, PLR, and MLR had AUCs below 0.55, indicating poor discriminative ability, with none reaching statistical significance. (Table 3; Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Comparative diagnostic performance measures for FGR diagnosis and composite adverse neonatal outcome in the FGR group: evaluation of NLR, PLR, MLR, and DNI

| Study groups |

Parameters | AUC (%95 CI) | Cut-off | p | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | +LR | -LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGR | NLR | 0.580 (0.537–0.622) | > 4.31 | < 0.001 | 54.20 | 54.36 | 1.19 | 0.84 |

| PLR | 0.562 (0.519–0.605) | > 132.5 | 0.006 | 54.60 | 53.09 | 1.16 | 0.86 | |

| MLR | 0.564 (0.520–0.609) | > 0.269 | 0.004 | 56.05 | 56.16 | 1.28 | 0.78 | |

| DNI | 0.677 (0.642–0.711) | >-2.9 | < 0.001 | 78.41 | 52.97 | 1.68 | 0.37 | |

| Composite adverse neonatal outcomes | NLR | 0.543 (0.498–0.589) | > 4.28 | 0.063 | 53.40 | 52.42 | 1.12 | 0.89 |

| PLR | 0.533 (0.486–0.575) | > 131.2 | 0.950 | 51.60 | 51.6 | 1.07 | 0.94 | |

| MLR | 0.526 (0.479–0.573) | > 0.272 | 0.268 | 51.11 | 53.79 | 1.11 | 0.91 | |

| DNI | 0.635 (0.598–0.670) | >-2.2 | < 0.001 | 69.90 | 55.36 | 1.56 | 0.51 |

AUC; area under curve; LR; likelihood ratios, FGR; fetal growth restriction, NLR; neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR; platelet to lymphocyte ratio, MLR; monocyte to lymphocyte ratio, DNI; delta neutrophil index

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic accuracy of NLR, PLR, MLR, and DNI in FGR

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of NLR, PLR, MLR, and DNI in predicting composite adverse neonatal outcomes in fetuses FGR

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of the DNI, a novel marker of inflammation, along with other hematological inflammatory indices such as NLR, PLR, and MLR in the diagnosis of LO-FGR and their potential predictive value for adverse neonatal outcomes. The findings demonstrate that among the evaluated markers, DNI shows the most promising performance in diagnosing LO-FGR and predicting composite adverse neonatal outcomes. NLR, PLR, and MLR could not show significant performance in predicting the composite adverse neonatal outcomes in the FGR group.

The placenta plays a central role in FGR pathogenesis. Placental insufficiency, characterized by poor vascularization and impaired nutrient exchange, is commonly associated with FGR. Inflammation changes the structure and function of the placenta, causing this deficiency or exacerbating the existing deficiency. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β are upregulated in FGR and contribute to the activation of pathways leading to endothelial dysfunction, reduced trophoblast invasion, and altered angiogenesis [16, 17]. The overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the placenta, driven by inflammatory mediators, leads to cellular damage and apoptosis. The NF-κB pathway, a critical regulator of the inflammatory response, is often activated in FGR due to placental hypoxia and oxidative stress [18, 19]. Activation of NF-κB leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, further amplifying the inflammatory response and contributing to the cascade of events that result in FGR. Inflammatory mediators also promote the release of anti-angiogenic factors like soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), which further impairs placental vascular development [20]. Besides all this, studies suggest that women with FGR show elevated levels of Th1 cytokines, which are associated with inflammation, compared to the anti-inflammatory Th2 cytokines that are normally predominant during pregnancy [21]. This dysregulation of the maternal immune system can disrupt placentation. Additionally, systemic inflammation in the mother can directly impact placental health, contributing to the development of FGR [22].

DNI is a relatively novel hematological marker that quantifies inflammation by measuring the proportion of immature granulocytes in the bloodstream. Introduced by Nahm et al. in 2008, the DNI has since gained attention for its utility in diagnosing and monitoring infectious diseases [6]. One of the earliest meta-analyses and systematic reviews of DNI, conducted by Park et al. in 2017, highlighted the diagnostic and prognostic significance of DNI [23]. The study reported a sensitivity of 0.67 (95% CI: 0.62–0.71), and a specificity of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.94–0.95) for detecting infections, affirming its reliability as an early indicator of inflammation. Based on studies showing the relationship between infection and inflammation and DNI in the adult population, the role of DNI in pregnant women has begun to be investigated. Cho et al. demonstrated that maternal serum DNI levels were significantly elevated in cases of severe preeclampsia compared to mild preeclampsia and normotensive pregnancies. Additionally, in their studies, the DNI also showed positive correlation with systolic and diastolic blood pressures, mean arterial pressure, proteinuria during 24 h, proteinuria in dipstick, and ominous symptoms [24]. In subsequent studies, maternal serum DNI levels were found to be a prognostic marker for the presence of chorioamnionitis in cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) [25, 26]. In pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), similar trends were observed, with Uysal et al. reporting higher DNI levels in GDM patients compared to normoglycemic pregnant women [27]. Eroglu et al. reported elevated DNI levels in pregnant women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) compared to the control group [28]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the role of DNI in FGR has not been previously investigated. In our study, we observed elevated DNI levels in pregnancies affected by FGR, suggesting a potential link between inflammatory processes and impaired fetal growth. Furthermore, our results indicate that DNI levels may have predictive value for composite adverse neonatal outcomes. Inflammatory cascades, triggered by factors such as maternal infection, chronic inflammation, or immune dysregulation, are believed to contribute to placental dysfunction, which compromises the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to the fetus [29, 30]. This placental insufficiency ultimately leads to restricted fetal growth. Our findings suggest that DNI may serve as a valuable marker for detecting underlying inflammatory processes in FGR, with potential for early diagnosis of affected pregnancies and prediction of adverse outcomes.

In this study, NLR, PLR and MLR were examined in pregnancies affected by FGR, and all three were found to be significantly higher in the FGR group compared to the control group. There is limited research in the literature investigating these parameters in FGR. Tolunay et al. evaluated NLR and PLR in FGR versus control groups, finding that while NLR was significantly elevated in the FGR group, no significant difference in PLR was observed between the groups [31]. In contrast, Koroglu et al. reported that both NLR and PLR were significantly lower in the FGR group [32]. Additionally, Salomon et al. found no significant difference in NLR between small-for-gestational-age (SGA) and appropriate-for-gestational-age (AGA) fetuses [33]. The variability in these findings across studies highlights the inconsistency in the reliability of these parameters. In our study, the AUC values for NLR, PLR, and MLR in diagnosing FGR were low, and none of these markers significantly predicted composite adverse outcomes in FGR cases.

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, its retrospective design limits the ability to establish causal relationships, as the data were collected after the fact, which can introduce biases such as incomplete records or unmeasured confounding factors. Second, the study was conducted at a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations with diverse clinical settings and demographics. To address these limitations and enhance the clinical applicability of DNI, future studies should adopt multi-center, prospective designs.

Conclusion

This study highlights the potential role of DNI as a promising biomarker for detecting inflammatory processes associated with LO-FGR and its complications. Among the hematological parameters studied, DNI demonstrated the strongest predictive performance for diagnosing LO-FGR and may serve as a valuable tool in identifying pregnancies at risk for adverse neonatal outcomes.

Author contributions

NVT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. KS and BB: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. NCK: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. STK: Formal Analysis, Resources. GA, BTC, ZS and GK: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. AC: Resources. YU: Supervision.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, with ethical approval obtained from the Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (approval number: 2024-02/05). Given the retrospective nature of the study, the Ethics Committee of Health Sciences University Etlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Training and Research Hospital granted a waiver for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sankilampi U, Hannila M-L, Saari A, Gissler M, Dunkel L. New population-based references for birth weight, length, and head circumference in singletons and twins from 23 to 43 gestation weeks. Ann Med. 2013;45:446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordijn SJ, Beune IM, Thilaganathan B, Papageorghiou A, Baschat AA, Baker PN, et al. Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudley NJ. A systematic review of the ultrasound estimation of fetal weight. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:80–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee, Berkley E, Chauhan SP, Abuhamad A. Doppler assessment of the fetus with intrauterine growth restriction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagdeviren G, Cevher F, Cendek B, Erkaya S. Histopathological examination of the curettage material in nonviable pregnancies and evaluation of the frequency of hydatidiform mole. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:2745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahm CH, Choi JW, Lee J. Delta neutrophil index in automated immature granulocyte counts for assessing disease severity of patients with sepsis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park BH, Kang YA, Park MS, Jung WJ, Lee SH, Lee SK, et al. Delta neutrophil index as an early marker of disease severity in critically ill patients with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisi K, Gungor S, Ispiroglu M, Kantarceken B. Could an increased percentage of Immature Granulocytes Accompanying Dyspepsia Predict COVID-19? Medicina. (Mex). 2022;58:1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansari-Lari MA, Kickler TS, Borowitz MJ. Immature granulocyte measurement using the Sysmex XE-2100. Relationship to infection and sepsis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardoel BW, Kenny EF, Sollberger G, Zychlinsky A. The Balancing Act of neutrophils. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:526–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrero-Cervera A, Soehnlein O, Kenne E. Neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19:177–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgakopoulou VE, Makrodimitri S, Triantafyllou M, Samara S, Voutsinas PM, Anastasopoulou A, et al. Immature granulocytes: innovative biomarker for SARS–CoV–2 infection. Mol Med Rep. 2022;26:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sauder MW, Lee SE, Schulze KJ, Christian P, Wu LSF, Khatry SK, et al. Inflammation throughout pregnancy and fetal growth restriction in rural Nepal. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee AC, Cherkerzian S, Tofail F, Folger LV, Ahmed S, Rahman S et al. Perinatal inflammation, fetal growth restriction, and long-term neurodevelopmental impairment in Bangladesh. Pediatr Res. 2024;:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Goldstein JA, Gallagher K, Beck C, Kumar R, Gernand AD. Maternal-fetal inflammation in the Placenta and the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Front Immunol. 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hauguel-de Mouzon S, Guerre-Millo M. The placenta cytokine network and inflammatory signals. Placenta. 2006;27:794–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilotić A, Nacka-Aleksić M, Pirković A, Bojić-Trbojević Ž, Dekanski D, Jovanović Krivokuća M. IL-6 and IL-8: an overview of their roles in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:14574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qu L, Yin Y, Yin T, Zhang X, Zhou X, Sun L. NCOA2-induced secretion of leptin leads to fetal growth restriction via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armistead B, Kadam L, Drewlo S, Kohan-Ghadr H-R. The role of NFκB in Healthy and Preeclamptic Placenta: trophoblasts in the spotlight. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jena MK, Sharma NR, Petitt M, Maulik D, Nayak NR. Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia and therapeutic approaches targeting the Placenta. Biomolecules. 2020;10:953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raghupathy R, Al-Azemi M, Azizieh F. Intrauterine growth restriction: Cytokine profiles of Trophoblast Antigen-stimulated maternal lymphocytes. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:734865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dumolt JH, Powell TL, Jansson T. Placental function and the development of fetal overgrowth and fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021;48:247–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JH, Byeon HJ, Lee KH, Lee JW, Kronbichler A, Eisenhut M, et al. Delta neutrophil index (DNI) as a novel diagnostic and prognostic marker of infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Res off J Eur Histamine Res Soc Al. 2017;66:863–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho HY, Jung I, Kim SJ, Park YW, Kim YH, Kwon J-Y. Increased delta neutrophil index in women with severe preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N. 1989. 2017;78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Cho HY, Jung I, Kwon J-Y, Kim SJ, Park YW, Kim Y-H. The Delta Neutrophil Index as a predictive marker of histological chorioamnionitis in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes: a retrospective study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0173382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dal Y, Karagün Ş, Akkuş F, Çolak H, Aytan H, Coşkun A. In premature rupture of membranes, maternal serum delta neutrophil index may be a predictive factor for histological chorioamnionitis and affect fetal inflammatory markers: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Am J Reprod Immunol N Y N. 1989. 2024;91:e13823. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Şahin Uysal N, Eroğlu H, Özcan Ç, Şahin D, Yücel A. Is the serum delta neutrophil index level different in gestational diabetic women? J Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2020;33:3349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eroğlu H, Şahin Uysal N, Sarsmaz K, Tonyalı NV, Codal B, Yücel A. Increased serum delta neutrophil index levels are associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47:4189–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ragsdale HB, Kuzawa CW, Borja JB, Avila JL, McDade TW. Regulation of inflammation during gestation and birth outcomes: inflammatory cytokine balance predicts birth weight and length. Am J Hum Biol off J Hum Biol Counc. 2019;31:e23245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geldenhuys J, Rossouw TM, Lombaard HA, Ehlers MM, Kock MM. Disruption in the regulation of Immune responses in the placental subtype of Preeclampsia. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolunay HE, Eroğlu H, Varlı EN, Akşar M, Şahin D, Yücel A. Evaluation of first-trimester neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio values in pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth retardation. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;17:98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koroglu N, Tayyar A, Tola EN, Cetin BA, Ozkan BO, Bahat PY, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, mean platelet volume and plateletcrit in isolated intrauterine growth restriction and prediction of being born small for gestational age. Arch Med Sci – Civiliz Dis. 2017;2:139–44. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salomon D, Fruscalzo A, Boulvain M, Feki A, Ben Ali N. Can the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio be used as an early marker of small fetuses for gestational age? A prospective study. Front Med. 2024;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.