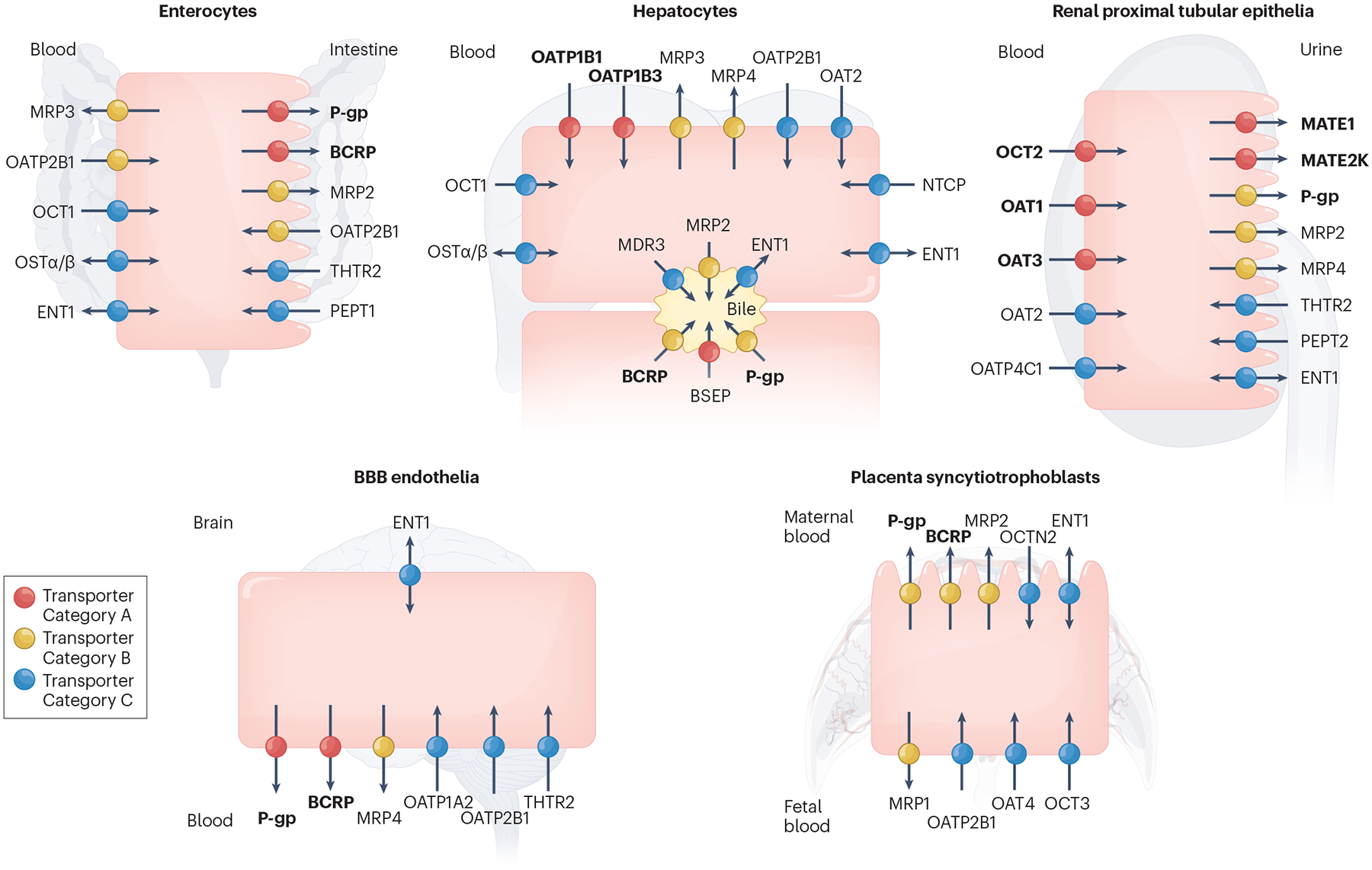

Fig. 1 |. Clinically important uptake and efflux transporters in plasma membranes.

Transporters in the plasma membrane of enterocytes, hepatocytes, renal proximal tubular epithelia, blood–brain barrier (BBB) endothelia and placenta syncytiotrophoblasts are shown. Transporters are only included in Fig. 1 if there is clinical evidence for their involvement in transporter-mediated drug–drug interactions (DDIs) and/or drug toxicity in the specific tissue and are categorized accordingly in each tissue. Thus, the designated colour (categorization) for a transporter may differ across tissues. In some cases, precise transporter categorization is confounded by the absence of specific in vivo inhibitors, the presence of redundant transporters and/or a lack of evidence from knockout models or human polymorphisms. Differences in transporter categorization compared with earlier assessments by the International Transporter Consortium3 are based on our current understanding of the literature, as summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Transporters recommended by regulatory agencies for screening during drug development are highlighted in bold in Fig. 1 (BCRP, MATE1, MATE2K, OAT1, OAT3, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OCT2, P-gp). Current ICH M12 guidelines recommend evaluation of OCT1, OATP2B1, MRP2 and BSEP on a case-by-case basis. Transporter Category A: Transporters coloured in red transport a wide range of pharmacological drug classes, are critical in drug and/or endogenous substrate disposition in the specific tissue and are the site of clinical DDIs and/or drug-mediated toxicity. Transporter Category B: Transporters coloured in yellow primarily transport a wide range of pharmacological drug classes, but clinical evidence supporting their involvement in the specific tissue in DDIs and/or drug toxicity is limited. Transporter Category C: Transporters coloured in blue primarily transport endogenous substrates and/or fewer drug classes, and there is weak clinical evidence demonstrating their involvement in the specific tissue in DDIs and/or drug toxicity. Transporter Category D: Transporters in this category transport endogenous substrates and a narrow range of drug classes. The significance of these transporters as a target for clinical DDIs in the specific tissue is not well-established, and/or there is limited published data showing that the inhibition of these transporters by a perpetrator leads to abnormal levels of endogenous substrate resulting in negative clinical outcomes. Therefore, these transporters (CNT1–3, ENT2–3, MCT1, MRP5–6, OAT4, OAT7, OCTN1–2, PCFT, PMAT, RFC, THTR1) are not included in Fig. 1. BCRP, breast cancer resistance protein (gene name, ABCG2); BSEP, bile salt export pump (ABCB11); CNT1–3, concentrative nucleoside transporter 1–3 (SLC28A1–3); ENT1–3, equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (SLC29A1–3); MATE1, MATE2K, multidrug and toxin extrusion protein (SLC47A1, 2); MCT1, monocarboxylate transporter 1 (SLC16A1); MDR3, multidrug resistance protein 3 (ABCB4); MRP1–6, multidrug resistance-associated protein (ABCC1–6); NTCP, sodium-taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (SLC10A1); OAT1–3, organic anion transporter 1–3 (SLC22A6–8); OAT4, organic anion transporter 4 (SLC22A11); OAT7, organic anion transporter 7 (SLC22A9); OATP1A2, organic anion transporting polypeptide 1A2 (SLCO1A2); OATP1B1, organic anion transporting polypeptide (SLCO1B1); OATP1B3, organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 (SLCO1B3); OATP2B1, organic anion transporting polypeptide 2B1 (SLCO2B1); OATP4C1, organic anion transporting polypeptide 4C1 (SLCO4C1); OCT1–3, organic cation transporter (SLC22A1–3); OCTN1–2, organic cation transporter novel 1–2 (SLC22A4–5); OSTα/β, organic solute transporter alpha/beta (SLC51A/B); PCFT, proton-coupled folate transporter (SLC46A1); PEPT1–2, peptide transporter 1–2 (SLC15A1–2); P-gp, P-glycoprotein (ABCB1); PMAT, plasma membrane monoamine transporter (SLC29A4); RFC, reduced folate carrier (SLC19A1); THTR1–2, thiamine transporter 1–2 (SLC19A2–3).