Abstract

Two tridentate N,N,O-donor ligands, HL1 = 4-chloro-2-(((2-(methylamino)ethyl)amino)methyl)phenol and HL2 = 4-chloro-2-(((2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)amino)methyl)phenol, have been used to synthesize phenolate-bridged dinuclear complexes [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed their structures. Both complexes form assemblies in the solid state. Moreover, the existence of nonconventional spodium bonds in 1 and tetrel bonds in 2 has been explored using theoretical calculations, including MEP surface plots and QTAIM and NCIplot analyses.

Introduction

A thorough knowledge and deep understanding of noncovalent interactions are essential to work in the field of supramolecular chemistry, crystal engineering, supramolecular catalysis, host–guest chemistry, nanochemistry, etc.1−12 Obviously, H-bonding and π-stacking interactions are the most common among all the supramolecular interactions and are well explored by several researchers.13−20 Investigations on σ-hole interactions are emerging very rapidly in recent times.21−30 These σ-hole interactions are sometimes referred to as a powerful competitor of the hydrogen bonding interactions in crystal engineering and supramolecular chemistry.21,22,31−34 σ-hole interactions in the compounds of Zn, Cd, or Hg are known as spodium bonds (SpB).35−42 Similarly, σ-hole interactions in the compounds of C, Si, Ge, Sn, or Pb are termed tetrel bonds.43−57 The spodium bonds and tetrel bonds have noncovalent contact with negligible covalent character and this is the most important difference between the spodium bonds and tetrel bonds and the normal coordination bonds (with high covalent character).58−61 Tetrel and spodium bonds are significantly weak compared with coordination bonds. The literature indicates that antibonding σ* orbitals participate in this type of interaction.37

In the present study, two tridentate N,N,O-donor ligands, HL1 = 4-chloro-2-(((2-(methylamino)ethyl)amino)methyl)phenol and HL2 = 4-chloro-2-(((2-(dimethylamino)ethyl)amino)methyl)phenol, have been used to synthesize two phenolate-bridged dinuclear complexes [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2). The structures of these complexes were confirmed by SC-XRD analysis. Intricate solid-state assemblies were facilitated by strong H-bonding between the amine groups of the ligands and the anionic halide or pseudohalide coligands. In addition to conventional structural analysis, we delved into the theoretical realm to investigate the presence of nonconventional spodium bonds in complex 1 and tetrel bonds in complex 2. These explorations employed MEP surface plots, QTAIM, and NCI plot to provide a deeper understanding of the electronic factors influencing these nonconventional interactions.

Experimental Section

The experiments and instrumental details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

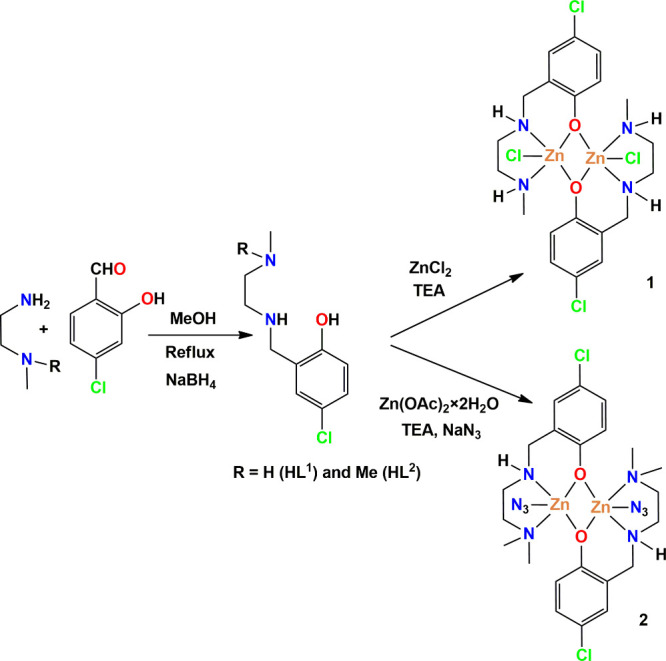

At first, two N,N,O-donor Schiff base ligands, HLa and HLb, were produced by refluxing the respective diamine (N-methyl-1,2-diaminoethane or N,N-dimethyl-1,2-diaminopropane respectively) and 5-chlorosalicylaldehyde in methanol in a 1:1 molar ratio.62−71 These were then reduced with a mild reducing agent, sodium borohydride, to produce the corresponding “reduced Schiff base” ligands HL1 and HL2. It may be noted here that the synthesis of HL2 was already reported in the literature.72 HL1 reacted with zinc chloride in methanol to produce complex 1 on adding a few drops of triethylamine. On the other hand, HL2 on reaction with zinc(II) acetate dihydrate produced complex 2 when sodium azide was added. Synthesis of complexes 1 and 2 is schematically shown in Scheme 1. Suitable single crystals of both complexes, suitable for SC-XRD analysis, were collected after a few days.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Pathways to [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) (TEA = Triethylamine).

1H NMR Spectra

1H NMR spectra have been collected for both the ligands and complexes. The spectra are discussed below.

1H NMR Spectra of the Ligands

The singlet signal at 7.14 ppm and two doublet signals, one at 7.08 ppm and another at 6.70 ppm, in the 1H NMR spectrum of HL1 may be assigned to the aromatic protons of the 5-chlorosalicylaldehyde moiety. J values of both doublet peaks are 7.5 Hz. Two benzylic protons give a singlet signal at 3.76 ppm. Three methyl protons give a signal at 3.17 ppm. The multiplets at 2.51 ppm (J = 7.1 Hz) may be assigned to four methylene protons. Two NH protons give a singlet signal at 2.26 ppm.

The NMR spectrum of HL2 is more or less similar to that of HL1. Three signals, a singlet at 7.13 ppm, two doublets at 7.08 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz), and another at 6.70 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz), correspond to the aromatic protons of the salicylaldehyde moiety. The singlet signal at 3.77 ppm indicates the presence of two benzylic protons. Six methyl protons give a singlet signal at 2.31 ppm. Two methylene protons give a triplet signal at 3.17 ppm. Two methylene protons give a triplet signal at 2.57 ppm. Two NH protons are observed as a singlet at 2.33 ppm. The 1H NMR spectra of HL1 and HL2 are given in Figures S1 and S2 (Supporting Information), respectively.

1H NMR Spectra of the Complexes

In the 1H NMR spectrum of complex 1, a singlet signal at 6.98 ppm and two doublet signals at 6.96 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz) and 6.64 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz), corresponding to six aromatic protons, have been detected. These are slightly shielded compared to the free ligand, HL1. Four benzylic protons have been observed as singlets at 4.08 ppm. This signal is slightly deshielded compared to the free ligand. Six methyl protons have been observed as a singlet at 3.17 ppm. Eight methylene protons have been observed as multiplets around 2.54 ppm (J = 7.1 Hz). Four NH protons have been observed as a singlet at 2.22 ppm.

In the 1H NMR spectrum of complex 2, a singlet signal at 6.99 ppm and two doublet signals at 6.96 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz) and 6.54 ppm (J = 7.5 Hz), corresponding to six aromatic protons, have been detected. These are slightly shielded compared to free ligand HL2. Four benzylic protons were observed as singlets at 3.76 ppm. Twelve methyl protons have been observed as a singlet at 2.26 ppm. Four methylene protons were observed at 3.17 ppm. Four methylene protons have been observed as a triplet at 2.84 ppm. Four NH protons have been observed as a singlet at 2.46 ppm. The 1H NMR spectra of complexes 1 and 2 are shown in Figures S3 and S4 (Supporting Information), respectively.

IR and Electronic Spectra

A distinct band in the region of 3382–3175 cm–1 in the infrared spectrum of each of complexes 1 and 2 indicates the presence of N–H stretching vibration.73−75 Bands indicating C–H stretching vibrations are observed in the region of 2995–2814 cm–1.76,77 A strong band at 2049 cm–1 indicates the presence of azide in complex 2.78,79 C–N and C–Cl stretching vibrations are present in the fingerprint region. The IR spectra of complexes 1 and 2 are shown in Figures S5 and S6, respectively (Supporting Information).

Electronic spectra of both complexes were recorded in a 10–4 M acetonitrile solution. The bands at 246 and 296 nm in the electronic spectrum of 1 and at 242 and 294 nm in the electronic spectrum of 2 may be attributed to the intraligand π → π* and n → π* transitions, respectively.80−82 The electronic spectra of both complexes are shown in Figures S7 and S8 (Supporting Information).

Description of Structures

The crystallographic data and refinement details of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) are summarized in Table 1. Important bond lengths and angles of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) are collected in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1. Crystallographic Data and Refinement Details of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2).

| [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) | Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| formula | C20H28Cl4N4O2Zn2 | C22H32Cl2N10O2Zn2 |

| FW | 629.04 | 670.26 |

| temperature (K) | 273 | 273 |

| crystal system | monoclinic | triclinic |

| space group | P21/c | P-1 |

| a (Å) | 12.6502(7) | 8.3747(11) |

| b (Å) | 19.6352(11) | 11.471(2) |

| c (Å) | 11.3654(7) | 16.822(2) |

| α | (90) | 108.781(3) |

| β | 112.281(2) | 102.880(3) |

| γ | (90) | 94.376(4) |

| Z | 4 | 2 |

| V (Å3) | 2612.3(3) | 1472.2(4) |

| dcalc (g cm–3) | 1.599 | 1.512 |

| μ (mm–1) | 2.270 | 1.849 |

| F(000) | 1280 | 688 |

| total reflections | 32413 | 12812 |

| unique reflections | 4630 | 6696 |

| observed data [I > 2σ(I)] | 4625 | 4558 |

| R(int) | 0.0387 | 0.0456 |

| R1, ⧧wR2 (all data) | 0.0621, 0.1236 | 0.0966, 0.1386 |

| R1, ⧧wR2 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0387, 0.1006 | 0.0456, 0.1105 |

| CCDC Number | 2353796 | 2353795 |

Table 2. Important Bond Lengths (Å) in [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2).

| complex | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Zn(1)–O(1) | 2.045(3) | 2.064(4) |

| Zn(1)–O(2) | 2.021(3) | 2.013(3) |

| Zn(1)–N(1) | 2.176(4) | 2.182(5) |

| Zn(1)–N(2) | 2.102(3) | 2.202(5) |

| Zn(1)–Cl(3) | 2.2936(13) | |

| Zn(2)–O(1) | 2.015(3) | 2.038(3) |

| Zn(2)–O(2) | 2.072(3) | 2.092(4) |

| Zn(2)–N(3) | 2.118(4) | 2.123(5) |

| Zn(2)–N(4) | 2.186(5) | 2.206(6) |

| Zn(2)–Cl(4) | 2.2706(16) | |

| Zn(1)–N(5) | 2.018(5) | |

| Zn(2)–N(8) | 2.022(6) |

Table 3. Important Bond Angles (deg) of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2).

| complex | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| O(1)–Zn(1)–O(2) | 78.23(12) | 75.31(14) |

| O(1)–Zn(1)–N(1) | 86.73(13) | 86.65(16) |

| O(1)–Zn(1)–N(2) | 140.61(13) | 149.78(16) |

| O(1)–Zn(1)–N(2) | 107.5(2) | |

| O(2)–Zn(1)–N(1) | 155.54(14) | 141.71(17) |

| O(2)–Zn(1)–N(2) | 97.90(13) | 97.26(16) |

| O(2)–Zn(1)–N(5) | 118.89(18) | |

| N(1)–Zn(1)–N(2) | 81.56(15) | 81.57(18) |

| N(1)–Zn(1)–N(5) | 98.55(18) | |

| N(2)–Zn(1)–N(5) | 101.8(2) | |

| O(1)–Zn(2)–O(2) | 77.74(11) | 74.15(14) |

| O(1)–Zn(2)–N(3) | 145.38(15) | 144.81(18) |

| O(1)–Zn(2)–N(4) | 95.20(15) | 98.78(17) |

| O(1)–Zn(2)–N(8) | 111.72(18) | |

| O(2)–Zn(2)–N(3) | 87.52(14) | 87.12(18) |

| O(2)–Zn(2)–N(4) | 149.77(14) | 148.89(19) |

| O(2)–Zn(2)–N(8) | 108.1(2) | |

| N(3)–Zn(2)–N(4) | 81.95(18) | 81.98(19) |

| N(3)–Zn(2)–N(8) | 102.3(2) | |

| N(4)–Zn(2)–N(8) | 102.7(2) |

[Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1)

Two distorted square pyramidal zinc centers, Zn(1) and Zn(2), are present in complex 1 (Figure 1). These two zinc centers are connected by two phenolate oxygen atoms, {O(1) and O(2)}, of the ligands. The binding mode of the ligand (L1)− is μ2- η2:η1:η1 to form a Zn2O2 core. The Zn(1) center is equatorially coordinated by N(1), N(2), and O(1) of a tridentate ligand and a phenolate oxygen atom, O(2), of a second molecule of the ligand. A chloride ion, Cl(3), coordinates the Zn(1) center in an apical position to complete its square pyramidal geometry. Similarly, the Zn(2) center is coordinated by N(3), N(4), and O(2) of a tridentate ligand, a phenolate oxygen atom, O(1), of a second ligand, and a chloride ion, Cl(4), to complete its square pyramidal geometry. The trigonality index (Addison parameter, τ) values are 0.248 and 0.073 for Zn(1) and Zn(2), respectively.83 The chelate ring, Zn(1)–N(1)–C(8)–C(9)–N(2), represents an envelope conformation (Figure S9a, Supporting Information) with puckering parameters q = 0.459(19) Å and φ = 293.9(5)°.84,85 Another chelate ring, Zn(2)–N(3)–C(18)–C(19)–N(4), represents a half-chair conformation (Figure S9b, Supporting Information) with puckering parameters q = 0.481(6) Å and φ = 272.5(5)°.84,85

Figure 1.

Perspective view of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1).

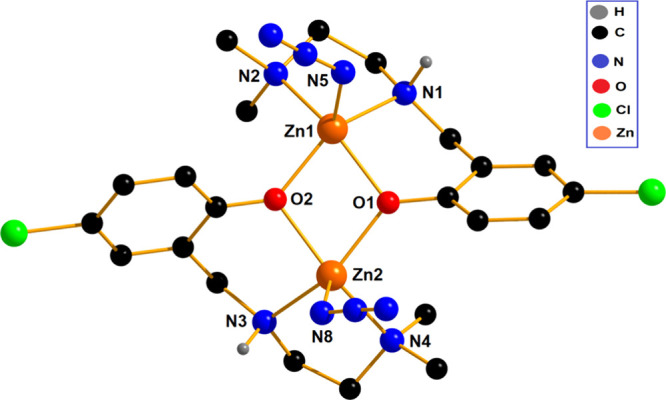

[Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2)

The complex of [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) is very similar to that of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1). The zinc(II) centers in complex 2 are bridged by two phenoxo oxygen atoms {O(1) and O(2)} of the reduced Schiff base ligands (Figure 2). The ligand (L2)− binds the zinc centers in the μ2-η2:η1:η1 mode to form a Zn2O2 core. The Zn(1) center is coordinated by N(1), N(2), and O(1) of a tridentate ligand, a phenolate oxygen atom, O(2), of a second molecule of the ligand, and a nitrogen atom, N(5), of an azide anion, to complete its square pyramidal geometry. Similarly, the Zn(2) center is also showing square pyramidal geometry, being coordinated by N(3), N(4), and O(2) of a tridentate ligand, a phenolate oxygen atom, O(1), of a second ligand, and a nitrogen atom, N(8), of an azide anion. The trigonality index (Addison parameter, τ) values are 0.248 and 0.073 for Zn(1) and Zn(2), respectively. The chelate ring, Zn(1)–N(1)–C(8)–C(9)–N(2), represents an envelope conformation (Figure S10a, Supporting Information) with puckering parameters q = 0.470(6) Å and φ = 99.5(5)°.84,85 Another chelate ring, Zn(2)–N(3)–C(18)–C(19)–N(4), represents an envelope conformation (Figure S10b, Supporting Information) with puckering parameters q = 0.476(7) Å and φ = 98.5(6)°.84,85

Figure 2.

Perspective view of [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2).

Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

The Hirshfeld surfaces of complexes 1 and 2 are shown in Figure S11 (Supporting Information). It is observed that the Cl···H/H···Cl interaction is the leading interaction in complex 1. These interactions are identified as red spots on the dnorm surface in Figure S11 (Supporting Information). The dominant interactions in complex 2 are N···H/H···N interactions. In addition, H···H contacts in the Hirshfeld surfaces of both complexes are indicated by other visible spots.

It is observed that 39.7 and 12.6% of the total Hirshfeld surface of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) are comprised of Cl···H/H···Cl and C···H/H···C interactions, respectively. The interactions are appearing as two distinct spikes in the 2D fingerprint plots (Figure 3).86 Similarly, 28.4, 20.6, and 9.4% of the total Hirshfeld surface of [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) are comprised of N···H/H···N, H···Cl/Cl···H, and C···H/H···C interactions, respectively. Each interaction appears as two distinct spikes in the 2D fingerprint plots (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Fingerprint plot: different contacts contributed to the total Hirshfeld surface area of [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1).

Figure 4.

Fingerprint plot: different contacts contributed to the total Hirshfeld surface area of [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2).

DFT Calculations

The theoretical study focuses on the analysis of self-assembled centrosymmetric dimers, which are stabilized by two N–H···X (X = Cl or N3) hydrogen bonds, referred to as R22(8) synthons (illustrated in Figure 5, top). Beyond these conventional synthons, the research also explores more unconventional interactions, such as Zn···Cl spodium bonds (SpB) in complex 1 and H3C···Cl tetrel bonds in complex 2. These interactions have been energetically evaluated and characterized through a combination of Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM) and Noncovalent Interaction (NCIplot) analyses.

Figure 5.

Partial views of the X-ray structures of (a) [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and (b) [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2) with indication of H-bonded dimers (top) and other supramolecular assemblies (bottom) analyzed herein.

We initiated our study by computing the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces of complexes 1 and 2 to identify the most nucleophilic and electrophilic regions of these molecules. Both complexes exhibit a similar distribution, with one-half of each molecule displaying predominantly nucleophilic properties due to the influence of anionic coligands, while the other half appears electrophilic, influenced by NH groups and alkyl linkers. The maximum MEP values are 54 kcal/mol for complex 1 and 46.4 kcal/mol for complex 2. Conversely, the MEP minima for these complexes are −57.5 and −52.7 kcal/mol, respectively, at the chlorido and azido ligands. Notably, the MEP values are also negative around the chlorine substituents, with −15.7 and −17.6 kcal/mol for complexes 1 and 2, respectively, thus being able to participate in noncovalent interactions as electron donors. Each complex features a small electrophilic cavity near the Zn atoms, which aligns well with the dimer formation depicted in Figure 5a (bottom), where the chloro ligand occupies this site. This cavity is smaller in complex 2, thereby preventing the same dimer arrangement. Additionally, in complex 2, the MEP at the methyl group is highlighted (Figure 6b, top), which is involved in forming the H3C···Cl tetrel bond (TtB, illustrated in Figure 5b, bottom). The MEP at this C atom is significantly positive, measured at 32.0 kcal/mol, supporting the establishment of the tetrel bond.

Figure 6.

MEP surfaces of (a) [Zn2(L1)2Cl2] (1) and (b) [Zn2(L2)2(N3)2] (2). The values are given in kcal/mol. Details of some portions of the surfaces are also given in the upper part. Isovalue, 0.001 au.

Figure 7 displays the QTAIM and NCIplot analyses for the two dimers of complex 1, effectively demonstrating how these combined methods can elucidate noncovalent interactions in real space. For the dimer illustrated in Figure 7a, the chlorine atom is linked to adjacent monomers through six bond critical points (BCPs) and corresponding bond paths (dashed bonds), which consist of five CH···Cl and one NH···Cl contacts. Additionally, two more BCPs connect the other chlorido ligand to one C–H group and one N–H group, cumulatively forming a total of eight hydrogen bonds. QTAIM analysis indicates that there are no direct connections between the chlorine atoms and zinc atoms, suggesting the absence of spodium bonds (SpBs). However, the NCIplot reveals a reduced density gradient (RDG) isosurface between the chlorine atom and the Zn2O2 ring, hinting at some level of interaction between the chlorine atoms and the metal centers. The interaction energy of −14.2 kcal/mol is primarily attributed to these eight hydrogen bonds with a possible minor contribution from the Zn···Cl interaction.

Figure 7.

QTAIM and NCIPlot analyses of the SpB (a) and R22(8) (b) dimers of complex 1. The dimerization energies are indicated. Only intermolecular interactions are represented.

The QTAIM/NCIplot analysis of the R22(8) dimer is depicted in Figure 7b, where each NH···Cl contact is characterized by a distinct BCP, a bond path, and a bluish RDG isosurface. This analysis also uncovers the formation of two CH···π and two NH···Cl contacts that further stabilize the dimer. Consequently, the significant dimerization energy of −20.3 kcal/mol rationalizes the formation of these self-assembled dimers in the solid state of complex 1. This analysis highlights the complex interplay of interactions and the robust nature of the dimeric structures facilitated by these noncovalent forces.

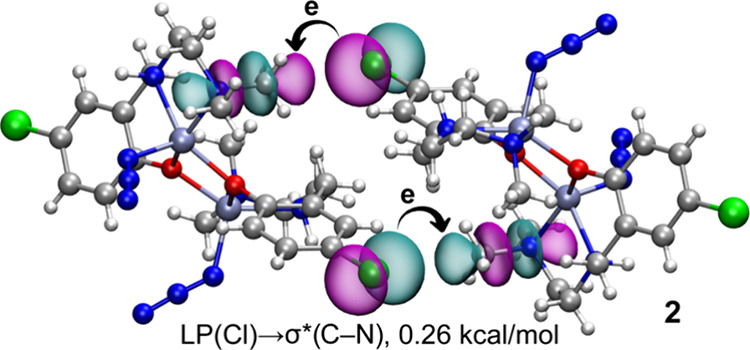

Figure 8 presents the analysis we conducted on the two dimers of complex 2. For the tetrel bonding dimer, QTAIM analysis confirms that the chlorine atom is connected to the carbon atom of the methyl group (instead of the H atoms), thereby validating the presence of the TtBs, shown in Figure 8a. Additionally, a green RDG isosurface is observed at the location of the BCP, supporting the existence of these interactions. The dimers are interconnected by two CH···Cl contacts and a π–π parallel displaced interaction, in which only one carbon atom of the aromatic ring is involved. The dimerization energy is relatively modest (−7.0 kcal/mol), attributed to the lack of strong hydrogen bonding involving the NH groups, as observed in other dimers of complexes 1 and 2.

Figure 8.

QTAIM and NCIPlot analyses of the TtB (a) and R22(8) (b) dimers of complex 2. The dimerization energies are indicated. Only intermolecular interactions are represented.

Furthermore, the analysis of the R22(8) dimer of complex 2, shown in Figure 8b, confirms the formation of NH···N bonds accompanied by CH···π, CH···Cl, and CH···N contacts. The dimerization energy of this configuration is substantial (−19.4 kcal/mol), similar to that observed in the R22(8) dimers of complex 1. This finding underscores the significant stabilizing role of the R22(8) synthon in facilitating the formation of these complex molecular structures in the solid state.

To further substantiate the existence and σ-hole nature of the H3C···Cl TtBs in complex 2, natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis was conducted. This computational approach is well suited for dissecting donor–acceptor interactions from an orbital perspective. Intriguingly, our findings indicate an electron donation from a lone pair (LP) orbital on the chlorine atom to the antibonding σ*(C–N) orbital, as depicted in Figure 9. Although the stabilization energy is modest at 0.26 kcal/mol, the involvement of these specific orbitals in the binding mechanism firmly supports the σ-hole nature of the interaction. This relatively small energy likely results from the elongated C···Cl distance of 3.44 Å (referenced in Figure 5), suggesting that this TtB bond is predominantly governed by electrostatic effects, consistent with the MEP values observed for the chlorine and carbon atoms. For the sake of comparison, LP → σ* contributions in similar tetrel bonds (involving carbon) have been reported, varying from 0.07 to 1.99 kcal/mol.87,88 Much larger contributions have been reported for hydrogen,64 halogen,89 and chalcogen bonding90−92 interactions due to the participation of heavier elements as Lewis acids.

Figure 9.

NBOs are involved in the LP(Cl) → σ*(C–N) interaction in complex 2. The second-order stabilization energy is indicated.

Conclusions

Two new zinc complexes have been synthesized using two tridentate-reduced Schiff base ligands, and their structures have been confirmed by SC-XRD analysis. Our comprehensive theoretical study employing QTAIM, NCIplot, and NBO analyses has significantly advanced our understanding of the complex noncovalent interactions present in complexes 1 and 2. We have elucidated the varied nature of these interactions, from conventional hydrogen bonds to less typical tetrel and spodium bonds. Particularly, the analyses validate the presence of tetrel bonds in complex 2, characterized by electron donation from chlorine’s lone pair to the antibonding σ*(C–N) orbital, despite the modest stabilization energy influenced by the long C···Cl distance. This finding emphasizes the predominant role of electrostatic effects in these interactions, as supported by the MEP data. The findings not only expand our understanding of these unconventional interactions but also underscore their potential applications in crystal engineering and materials science. The tetrel and spodium bonds identified here play crucial roles in stabilizing the supramolecular architectures, suggesting that such interactions could be strategically exploited in the design and synthesis of advanced materials with tailored properties.

While this study focuses on the solid-state behavior of these interactions, the implications for practical applications are significant. The insights gained could guide the development of new materials for applications in molecular recognition, catalysis, and the design of functional supramolecular systems. Future work may explore the influence of these interactions under different environmental conditions, such as in solution or under variable temperatures, to further understand their potential utility in real-world applications.

Acknowledgments

P.M. is thankful to UGC, India, for Senior Research Fellowship.

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2353796 and 2353795 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for complexes 1 and 2 respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, U.K.; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c06136.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Muller-Dethlefs K.; Hobza P.. Non-Covalent Interactions: Theory and Experiment. In Theoretical and Computational Chemistry Series, 1st ed; Royal Society of Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J.; Jordan K. D.; Thiel W.; Lim C., Eds.; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudov K. T.; Kopylovich M. N.; Pombeiro A. J. L. (Eds.) Noncovalent Interactions in Catalysis, 1st ed.; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maharramov A. M.; Mahmudov K. T.; Kopylovich M. N.; Guedes da Silva M. F. C.; Pombeiro A. J. L. (Eds.) Non-covalent Interactions in the Synthesis and Design of New Compounds, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.:: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda M.; Aoki T.; Akiyama T.; Nakamuro T.; Yamashita K.; Yanagisawa H.; Nureki O.; Kikkawa M.; Nakamura E.; Aida Aida T.; Itoh Y. Alternating Heterochiral Supramolecular Copolymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (24), 10817–10824. 10.1021/jacs.1c00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssandier J.; Feyter S. D.; Mali K. S. Host–Guest Chemistry in Two-Dimensional Supramolecular Networks. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11465–11487. 10.1039/C6CC05256H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corma A.; Rey F.; Rius J.; Sabater M. J.; Valencia S. Supramolecular Self-Assembled Molecules as Organic Directing Agent for Synthesis of Zeolites. Nature 2004, 431, 287–290. 10.1038/nature02909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X.; Zhao Y. Biomedical Applications of Supramolecular Systems Based on Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7794–7839. 10.1021/cr500392w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steed J. W.; Turner D. R.; Wallace K. J.. Core Concepts in Supramolecular Chemistry and Nanochemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2007; pp 1– 297. [Google Scholar]

- Rens Ham C.; Nielsen J.; Pullen S.; Reek J. N. H. Supramolecular Coordination Cages for Artificial Photosynthesis and Synthetic Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123 (9), 5225–5261. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dojin K.; Ayse A.; Nickels J.; Kakishi U.; Mariano L. B.; Vladimir N. B.; Stefan W. H. Supramolecular Complex of Photochromic Diarylethene and Cucurbit[7]uril: Fluorescent Photoswitching System for Biolabeling and Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (31), 14235–14247. 10.1021/jacs.2c05036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia D.; Wang P.; Ji X. D.; Khashab N. M.; Sessler J. L.; Huang F. Functional Supramolecular Polymeric Networks: The Marriage of Covalent Polymers and Macrocycle-Based Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120 (13), 6070–6123. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middya P.; Karmakar M.; Gomila R. M.; Drew M. G. B.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. The importance of spodium bonds, H-bonds and π-stacking interactions in the solid state structures of four zinc complexes with tetradentate secondary diamine ligands. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 9346–9363. 10.1039/D2NJ05490F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Drew M. G. B.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Estimation of conventional C–H···π (arene), unconventional C–H···π (chelate) and C–H···π (thiocyanate) interactions in hetero-nuclear nickel(II)–cadmium(II) complexes with a compartmental Schiff base. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 5384–5397. 10.1039/C6DT04906K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. N.; Hoffman J. T.; Shirin Z.; Carrano C. J. H-Bonding Interactions and Control of Thiolate Nucleophilicity andSpecificity in Model Complexes of Zinc Metalloproteins. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44 (6), 2012–2017. 10.1021/ic048630f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengar S. R.; Miller J. J.; Basu P. Design, syntheses, and characterization of dioxo-molybdenum(vi) complexes with thiolate ligands: effects of intraligand NH···S hydrogen bonding. Dalton Trans. 2008, 91 (19), 2569–2577. 10.1039/b714386a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K.-Y.; Hsieh C.-C.; Horng Y.-C. Mononuclear zinc(II) and mercury(II) complexes of Schiff bases derived from pyrrolealdehyde and cysteamine containing intramolecular NH···S hydrogen bonds. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009, 694 (13), 2085–2091. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M.; Mirzaei M.; Hamid A. S.; Kafshdar Z. H.; Ziaekhodadadian H.; Momenzadeh E.; Mague J. T.; Gil D. M.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A. On the importance of π-stacking interactions in the complexes of copper and zinc bearing pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid N-oxide and N-donor auxiliary ligands. CrystEngComm 2022, 24, 6677–6687. 10.1039/D2CE00656A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z.-F.; Wang J.-Y.; Pei J. Control of π–π Stacking via Crystal Engineering in OrganicConjugated Small Molecule Crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18 (1), 7–15. 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b01385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh S. R.; Gawade R. L.; Kumar D.; Kotmale A.; Gonnade R. G.; Stürzer T. Crystal Engineering for Intramolecular π–π Stacking: Effect of Sequential Substitution of F on Molecular Geometry in Conformationally Flexible Sulfonamides. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19 (10), 5665–5678. 10.1021/acs.cgd.9b00667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J. S.; Lane P.; Politzer P. Expansion of the σ-hole concept. J. Mol. Model. 2009, 15, 723–729. 10.1007/s00894-008-0386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauzá A.; Mooibroek T. J.; Frontera A. The bright future of unconventional σ/π-hole interactions. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16, 2496–2517. 10.1002/cphc.201500314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak T.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Differentiating intramolecular spodium bonds from coordination bonds in two polynuclear zinc(II) Schiff base complexes. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 2703–2710. 10.1039/D1CE00214G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar M.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S.; Mooibroek T. J.; Bauzá A. Intramolecular Spodium Bonds in Zn(II) Complexes: Insights from Theory and Experiment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (19), 7091. 10.3390/ijms21197091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politzer P.; Murray J. S.; Clark T. Halogen bonding and other r-hole interactions: a perspective. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 11178–11189. 10.1039/c3cp00054k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolar M. H.; Hobza P. Comnputer modelling of halogen bonds and other σ-hole interaction. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116 (9), 5155–5187. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politzer P.; Murray J. S.; Clark T.; Resnati G. The σ-hole revisited. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 32166–32178. 10.1039/C7CP06793C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadwaj P. R.; Varadwaj A.; Jin B.-Y. Halogen bonding interaction of chloromethane with several nitrogen donating molecules: addressing the nature of the chlorine surface σ-hole. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 19573. 10.1039/C4CP02663B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski S. J. Hydrogen bonds, and r-hole and σ-hole bonds – mechanisms protecting doublet and octet electron structures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 29742. 10.1039/C7CP06393H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolář M.; Hobza P.; Bronowska A. K. Plugging the explicit σ-holes in molecular docking. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 981–983. 10.1039/C2CC37584B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkorta I.; Elguero J.; Frontera A. Not only hydrogen bonds: other noncovalent interactions. Crystals 2020, 10, 180. 10.3390/cryst10030180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh V.; Mahmoudi G.; Vinokurova A. M.; Pokazeev K. M.; Alekseeva K. A.; Miroslaw B.; Khandar A. A.; Frontera A.; Safin D. A. Spodium bonds and metal–halogen···halogen–metal interactions in propagation of monomeric units to dimeric or polymeric architectures. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1252, 132144 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.132144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar D.; Frontera A.; Gomila R. M.; Das S.; Bankura K. Synthesis, spectroscopic findings and crystal engineering of Pb(II)–Salen coordination polymers, and supramolecular architectures engineered by shole/spodium/tetrel bonds: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 6352–6363. 10.1039/D1RA09346K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal H. S.; Sahu A. K.; Frontera A.; Bauzá A. Spodium Bonds in Biological Systems: Expanding the Role of Zn in Protein Structure and Function. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3945–3954. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy J.; Jemmis E. D. Contrasting behavior of the Z bonds in X–Z···Y weak interactions: Z= main group elements versus the transition metals. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 1132–1143. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b02073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy J.; Jemmis E. D. Designing M-bond (X-M···Y, M 5 = transition metal): σ-hole and radial density distribution. J. Chem. Sci. 2019, 131, 117. 10.1007/s12039-019-1708-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauzá A.; Alkorta I.; Elguero J.; Mooibroek T. J.; Frontera A. Spodium Bonds: Noncovalent interactions involving group 12 elements. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17482–17487. 10.1002/anie.202007814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onn C. S.; Hill A. F.; Ward J. S. Spodium bonding in bis(alkynyl)mecurials. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 2552–2555. 10.1039/D3CC06027F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.; Frontera A.; Pandey S. K. Coordination versus spodium bonds in dinuclear Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes with a dithiophosphate ligand. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 19402–19415. 10.1039/D1NJ03165A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar D.; Frontera A.; Roy S.; Sutradhar D. Experimental and theoretical survey of intramolecular Spodium bonds/σ/π-holes and noncovalent interactions in trinuclear Zn(II)-salen type complex with OCN– ions: A holistic view in crystal engineering. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 1786–1797. 10.1021/acsomega.3c08422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M.; Zhao Q.; Yu H.; Fu M.; Li Q. Insight into Spodium−π bonding characteristics of the MX2· · · π (M = Zn, Cd and Hg; X = Cl, Br and I) Complexes—A theoretical study. Molecules 2022, 27, 2885. 10.3390/molecules27092885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomila R. M.; Bauza A.; Mooibroek T. J.; Frontera A. Spodium bonding in five coordinated Zn(II): a new player in crystal engineering. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 3084–3093. 10.1039/D1CE00221J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiekink E. R. T. Supramolecular assembly based on “emerging” intermolecular interactions of particular interest to coordination chemists. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 345, 209–228. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Drew M. G. B.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Non-covalent tetrel bonding interactions in hemidirectional lead(II) complexes with nickel(II)-salen type metalloligands. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 6062–6076. 10.1039/C7NJ05148D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdya S.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Formation of a tetranuclear supramolecule via non-covalent Pb···Cl tetrel bonding interaction in a hemidirected lea(II) complex with a nicke(II) containing metaloligand. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 6859–6868. 10.1039/C9CE01283D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner S. Origins and properties of the tetrel bond. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 5702–5717. 10.1039/D1CP00242B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal I.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. On the importance of RH3C···N tetrel bonding interactions in the solid state of a dinuclear zinc complex with a tetradentate Schiff base ligand. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 3391–3397. 10.1039/D0CE01864C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li Q.; Scheiner S. Cooperativity between H-bonds and tetrel bonds. Transformation of a noncovalent C···N tetrel bond to a covalent bond. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 29738–29746. 10.1039/D3CP04430K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litle E.; Gabbai F. P. Double axial stabilization of a carbenium ion via convergent P = O → C+ tetrel bonding. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 690–693. 10.1039/D3CC04729F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedeoglu B.; Gürek A. G.; Zorlu Y.; Ayhan M. M. Engineering supramolecular helical assemblies via interplay between carbon(sp) tetrel and halogen bonding interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 11493–11500. 10.1039/D3CP00134B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katlenok E. A.; Kuznetsov M. L.; Cherkasov A. V.; Kryukov D. M.; Bokach N. A.; Kukushkin V. Y. Metal-involved C···dz2-PtII tetrel bonding as a principal component of the stacking interaction between arenes and the platinum(II) square-plane. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2023, 10, 3916–3928. 10.1039/D3QI00555K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Southern S. A.; Nag T.; Kumar V.; Triglav M.; Levin K.; Bryce D. L. NMR response of the tetrel bond donor. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 851–865. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c10121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varadwaj P. R. Tetrel bonding in anionic recognition: A first principles investigation. Molecules 2022, 27, 8449. 10.3390/molecules27238449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang C.–T. P.; Trung N. T. Complexes of carbon dioxide with methanol and its monohalogen-substituted: Beyond the tetrel bond. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 809, 140158 10.1016/j.cplett.2022.140158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.; Firdoos T.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A.; Pandey S. K. Experimental and theoretical study of tetrel bonding and noncovalent interactions in hemidirected lead(II) phosphorodithioates: An implication on crystal engineering. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 2138–2154. 10.1021/acs.cgd.2c01173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roeleveld J. J.; Deprez S. J. L.; Verhoofstad A.; Frontera A.; van der Vlugt J. I.; Mooibroek T. J. Engineering crystals using sp3-C centred tetrel bonding interactions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26, 10126–10132. 10.1002/chem.202002613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legon A. C. Tetrel, pnictogen and chalcogen bonds identified in the gas phase before they had names: A systematic look at non-covalent interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 14884–14896. 10.1039/C7CP02518A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi G.; Lawrence S. E.; Cisterna J.; Cárdenas A.; Brito I.; Frontera A.; Safin D. A. A new spodium bond driven coordination polymer constructed from mercury(II) azide and 1,2-bis(pyridin-2-ylmethylene)hydrazine. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 21100–21107. 10.1039/D0NJ04444J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi G.; Zangrando E.; Miroslaw B.; Gurbanov A. V.; Babashkina M. G.; Frontera A.; Safin D. A. Spodium bonding and other non-covalent interactions assisted supramolecular aggregation in a new mercury(II) complex of a nicotinohydrazide derivative. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 519, 120279 10.1016/j.ica.2021.120279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi G.; Masoudiasl A.; Babashkina M. G.; Frontera A.; Doert T.; White J.; Zangrando E.; Zubkov F. I.; Safin D. On the importance of π-hole spodium bonding in tricoordinated HgII complexes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 17547–17551. 10.1039/D0DT03938A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P.; Banerjee S.; Radha A.; Firdoos T.; Sahoo S. C.; Pandey S. K. Role of non-covalent interactions in the supramolecular architectures of mercury(II) diphenyldithiophosphates: An experimental and theoretical investigation. New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 2249–226. 10.1039/D0NJ05709F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K.; Harms K. Chattopadhyay, Two Cobalt(III) Schiff Base Complexes of the Type[Co(ABC)(DE)X]: Facile Synthesis, Characterization, Catechol Oxidase and Phenoxazinone Synthase Mimicking Activity. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 8207–8220. 10.1002/slct.201701536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj V. K.; Hundal M. S.; Corbella M.; Gomez V.; Hundal G. Salicylaldimine Schiff bases – Generation of self-assembled and chiral complexes with Ni(II) and Zn(II) ions. An unusual antiferromagnetic interaction in a triply bridged Ni(II) dimer. Polyhedron 2012, 38, 224–234. 10.1016/j.poly.2012.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Middya P.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. The crucial role of hydrogen bonding in shaping the structures of zinc-based coordination polymers using tridentate N, N, O donor reduced Schiff base ligands and bridging acetates. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 13905–13914. 10.1039/D4RA00550C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K.; Banerjee A.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. One pot synthesis of two cobalt(III) Schiff base complexes with chelating pyridyltetrazolate and exploration of their bio-relevant catalytic activities. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 28216–28237. 10.1039/C8RA03035A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K.; Banerjee A.; Roy S.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. A combined experimental and theoretical study on supramolecular assemblies in octahedral cobalt(III) salicylaldimine complexes having pendant side arms. Polyhedron 2016, 112, 86–95. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K.; Dutta T.; Drew M. G. B.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. A combined experimental and theoretical study on an ionic cobalt(III/II) complex with a Schiff base ligand. Polyhedron 2020, 182, 114432 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bera S.; Bhunia S.; Gomila R. M.; Drew Michael G. B.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Structure-directing role of CH···X (X = C, N, S, Cl) interactions in three ionic cobalt complexes: X-ray investigation and DFT study using QTAIM Vr predictor to eliminate the effect of pure Coulombic forces. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 29568–29583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middya P.; Roy D.; Chattopadhyay S. Synthesis, structures and magnetic properties of end-on pseudo-halide bridged dinuclear copper(II) complexes with N,O-donor salicylaldimine Schiff base blocking ligands: A review. Inorg, Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 121377 10.1016/j.ica.2023.121377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Middya P.; Chowdhury D.; Chattopadhyay S. An overview of the synthesis, structures and magnetic properties of end-on pseudo-halide bridged dinuclear nickel(II) complexes with N,O-donor salicylaldimine Schiff base blocking ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 552, 121489 10.1016/j.ica.2023.121489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik P.; Chattopadhyay S.; Ghosh A. Synthesis and structure of mono-, di- and tri-nuclear copper(II) benzoate complexes with a tridentate N2O donor Schiff base ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2013, 396, 66–71. 10.1016/j.ica.2012.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo L. E.; Hu H. J.; Hazell A. 4-Chloro-2-[2-(dimethylamino)ethylamino- methyl]phenol and 2-[2-(dimethylamino)- ethylaminomethyl]-6-methoxyphenol, Acta Cryst. Sect. C. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1999, C55, 245–248. 10.1107/S0108270198012050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S.; Ray M. S.; Chaudhuri S.; Mukhopadhyay G.; Bocelli G.; Cantoni A.; Ghosh A. Nickel(II) and copper(II) complexes of tetradentate unsymmetrical Schiff base ligands: First evidence of positional isomerism in such system. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2006, 359, 1367–1375. 10.1016/j.ica.2005.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazari A.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A.; Drew M. G. B.; Ghosh A. Change in molecular shapes of the trinuclear CuII2ZnII complexes on Schiff base reduction: structural and theoretical investigations. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 4848–4856. 10.1039/D1CE00490E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pellico D.; Gomez-Gallego M.; Escudero R.; Ramirez-Lopez P.; Olivan M.; Sierra M. A. C-Branched chiral (racemic) macrocyclic anino acids: structure of their Ni(II), Zn(II) and Cu(II) complexes. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 9145–9153. 10.1039/c1dt10539f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar M.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Insight into the formation of H-bonds propagating the monomeric zinc complexes of a tridentate reduced Schiff base to form an infinite chain. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 1918–1928. 10.1039/D0CE01840F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh K.; Roy S.; Ghosh A.; Banerjee A.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Three mononuclear octahedral cobalt(III) complexes with salicylaldimine Schiff bases: Synthesis, characterization, phenoxazinone synthase mimicking activity and DFT study on supramolecular interactions. Polyhedron 2016, 112, 6–17. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.02.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Harms K.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Exploration of photocatalytic activity of an end-on azide bridged one-dimensional cadmium(II) Schiff base complex for the degradation of organic dye in visible light. Polyhedron 2017, 121, 199–205. 10.1016/j.poly.2016.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das M.; Chatterjee S.; Chattopadhyay S. Synthesis and characterization of two new nickel(II) complexes with azide: Formation of a two-dimensional coordination polymer with 63-hcb topology. Polyhedron 2014, 68, 205–211. 10.1016/j.poly.2013.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazari A.; Das L. K.; Kadam R. M.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Ghosh A. Unprecedented structural variations in trinuclear mixed valence Co(II/III) complexes: theoretical studies, pnicogen bonding interactions and catecholase-like activities. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3862–3876. 10.1039/C4DT03446E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvaganesan K.; Mayilmurugan R.; Suresh E.; Palaniandavar M. Iron(III) Complexes of Tridentate 3N Ligands as Functional Models forCatechol Dioxygenases: The Role of Ligand N-alkyl Substitution and Solvent on Reaction Rate and Product Selectivity. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 10294–10306. 10.1021/ic700822y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak T.; Bhattacharyya A.; Das M.; Harms K.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Chattopadhyay S. Phosphatase Mimicking Activity of Two Zinc(II) Schiff Base Complexes with Zn2O2 Cores: NBO Analysis and MEP Calculation to Estimate Non-Covalent Interactions. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 6286–6295. 10.1002/slct.201701246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Addison A. W.; Rao T. N.; Reedijk J.; van Rijn J.; Verschoor G. C.. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. 10.1039/DT9840001349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D.; Pople J. A. General definition of ring puckering coordinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 1354–1358. 10.1021/ja00839a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D. On the correct usage of the Cremer-Pople puckering parameters as quantitative descriptors of ring shapes- a reply to recent criticism by petit. Dillen and Geise. Acta Cryst. 1984, B40, 498–500. 10.1107/S0108768184002548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman M. A.; Byrom P. G. A novel definition of a molecule in a crystal. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1997, 267, 215–220. 10.1016/S0009-2614(97)00100-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese M.; Pizzi A.; Daolio A.; Ursini M.; Frontera A.; Demitri N.; Lenczyk C.; Wojciechowski J.; Resnati G. Geminal Charge-Assisted Tetrel Bonds in Bis-Pyridinium Methylene Salts. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 1898–1902. 10.1021/acs.cgd.2c01386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daolio A.; Calabrese M.; Pizzi A.; Lo Iacono C.; Demitri N.; Beccaria R.; Gomila R. M.; Frontera A.; Resnati G. Tetrel bond affects the self-assembly of acetylcholine and its analogues and is an ancillary interaction in protein binding. Chem. - Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202401824 10.1002/chem.202401824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatova N. S.; Radzhabov A. D.; Ivanov A. M.; Burguera S.; Frontera A.; Abramov P. A.; Postnikov P. S.; Kukushkin V. Yu. Key-to-lock halogen bond-based tetragonal pyramidal association of iodonium cations with the lacune rims of beta-octamolybdate. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 12459–12472. 10.1039/D4SC01695E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomila R. M.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A. Enhancing chalcogen bonding by metal coordination. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 5977–5982. 10.1039/D2DT00796G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burguera S.; Gomila R. M.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A. Chalcogen Bonds, Halogen Bonds and Halogen···Halogen Contacts in Di- and Tri-iododiorganyltellurium(IV) Derivatives. Inorganics 2023, 11, 209. 10.3390/inorganics11050209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña M. N.; Frontera A.; Bauza A. Charge Assisted S/Se Chalcogen Bonds in SAM Riboswitches: A Combined PDB and ab Initio Study. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 1701–1708. 10.1021/acschembio.1c00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2353796 and 2353795 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for complexes 1 and 2 respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, U.K.; fax: +44 1223 336033.