Summary

Heterotaxy is a disorder characterized by severe congenital heart defects (CHDs) and abnormal left-right patterning in other thoracic or abdominal organs. Clinical and research-based genetic testing has previously focused on evaluation of coding variants to identify causes of CHDs, leaving non-coding causes of CHDs largely unknown. Variants in the transcription factor zinc finger of the cerebellum 3 (ZIC3) cause X-linked heterotaxy. We identified an X-linked heterotaxy pedigree without a coding variant in ZIC3. Whole-genome sequencing revealed a deep intronic variant (ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G) predicted to alter RNA splicing. An in vitro minigene splicing assay confirmed the variant acts as a cryptic splice acceptor. CRISPR-Cas9 served to introduce the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant into human embryonic stem cells demonstrating pseudoexon inclusion caused by the variant. Surprisingly, Sanger sequencing of the resulting ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G amplicons revealed several isoforms, many of which bypass the normal coding sequence of the third exon of ZIC3, causing a disruption of a DNA-binding domain and a nuclear localization signal. Short- and long-read mRNA sequencing confirmed these initial results and identified additional splicing patterns. Assessment of four isoforms determined abnormal functions in vitro and in vivo while treatment with a splice-blocking morpholino partially rescued ZIC3. These results demonstrate that pseudoexon inclusion in ZIC3 can cause heterotaxy and provide functional validation of non-coding disease causation. Our results suggest the importance of non-coding variants in heterotaxy and the need for improved methods to identify and classify non-coding variation that may contribute to CHDs.

Keywords: alternative splicing, cardiovascular system, intronic variant, left-right patterning, pseudoexon inclusion, X-linked disease

Coding variants in the transcription factor ZIC3 cause X-linked heterotaxy, a laterality defect causing congenital anomalies. Functional genomic analyses of a ZIC3 intronic variant identified in an X-linked heterotaxy pedigree demonstrated pseudoexon inclusion leading to RNA-splicing disruption, highlighting the importance of whole-genome sequencing to identify potential disease-causing variants.

Introduction

Despite being externally symmetrical, internal organs such as the heart, lungs, stomach, liver, spleen, and intestines normally display asymmetries in their overall placement and structure along the left-right (LR) sides of the body. During embryonic development after the formation of the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes, the LR axis is established as a result of signaling generated at a pit-like structure located at the end of the primitive streak known as the left-right organizer (LRO). As demonstrated in a variety of vertebrate model systems (mouse, frog, zebrafish), motile cilia within the LRO generate a leftward fluid flow that ultimately triggers asymmetric gene expression between the left and right side of the developing embryo. This asymmetric gene expression provides the signals necessary for proper LR patterning resulting in the normal, asymmetric placement and structure of the organs within the thoracic and abdominal cavity (termed situs solitis).1

Failure to properly establish and maintain the LR axis results in a spectrum of laterality phenotypes. In situs inversus totalis, a complete mirror image of the internal organs takes place, whereas in heterotaxy (situs ambiguus), congenital heart defects (CHDs) in combination with disrupted LR patterning in at least one other organ occurs with a frequency of 0.8 per 10,000 livebirths.2 Due to the randomization of LR patterning, individuals with heterotaxy display wide phenotypic heterogeneity but often require surgical intervention for their diverse CHDs and have a high mortality (∼40.2%), typically driven by the specific CHD lesion.3 Depending on the complexity of the organs involved, these patients may also present with additional conditions such as frequent infections caused by asplenia, chronic respiratory symptoms caused by defective cilia in the respiratory tract, or bowel obstruction caused by intestinal rotational abnormalities.4

The first gene to be definitively associated with heterotaxy in humans, Zinc finger of the cerebellum 3 (ZIC3), is located on the X chromosome.5 ZIC3 is a member of the GLI superfamily of transcription factors and contains five tandem C2H2 zinc-finger (ZF) DNA-binding domains.6,7 Overlapping the ZF-binding domains are three nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequences and one cryptic exportin-1-dependent nuclear export sequence (NES), which collectively regulate the nuclear import and export of ZIC3.8,9 Despite numerous in vivo and in vitro studies providing evidence for the involvement of ZIC3 in a variety of known LR signaling pathways such as SHH, NODAL, WNT, and planar cell polarity (PCP), the precise mechanism by which variants in ZIC3 cause heterotaxy remains to be elucidated.10

Although autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance patterns in several genes have since been identified in patients with heterotaxy,11 ZIC3 variants are still the most common monogenic cause of heterotaxy identified and are estimated to account for ∼75% of X-linked familial and ∼1%–5% of sporadic heterotaxy cases.12,13 To date, over 40 ZIC3 variants and several structural deletions involving ZIC3 have been reported in individuals with isolated CHDs, heterotaxy, situs inversus, VACTERL association (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defects, tracheo-esophageal fistula, renal anomalies, and limb abnormalities), and X-linked oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum disorder.5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 The majority of the ZIC3 variants are located within the coding region and often disrupt the ZF DNA-binding domains, the NLS sequences, and/or the NES. This information is useful for functional genomics to test the consequence of the ZIC3 variants using well-established in vitro assays. For example, several variants displayed reduced nuclear localization12,13,15,24,27 or abnormal SV40 luciferase reporter activity.12,13,21,27 Currently, only one non-coding ZIC3 variant, which causes the loss of the canonical splice donor immediately after ZIC3’s first coding exon in a male fetus with heterotaxy, has been reported.24

In this study, an X-linked heterotaxy pedigree without a coding variant in ZIC3 was identified. X-exome sequencing analysis detected a rare, missense, hemizygous variant in GPR101 (G protein coupled receptor 101, NM_054021.1:c.1225G>A, NP_473362.1:p.V409M). The potential role of GPR101 in LR patterning has not been explored; however, GPR101’s closest phylogenetic relative, GPR161, localizes to primary cilia and negatively regulates SHH signaling.32 In addition, morpholino oligonucleotide (MO)-induced knockdown of Gpr161 in zebrafish causes LR asymmetry of visceral organs, cardiac defects, and altered left-sided gene expression.33 Thus, GPR101 was investigated as a candidate cause of X-linked heterotaxy. Experiments in Xenopus laevis with gpr101 MO or GPR101 mRNA injections revealed LR patterning defects in tadpoles. However, an exhaustive examination of a global Gpr101 knockin mouse model with an inserted LacZ reporter (Gpr101tm1b(KOMP)Mbp)34 determined that these mice did not display reduced viability or a heterotaxy phenotype. Therefore, the GPR101 variant initially identified was considered not disease causative.

Subsequent whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analysis in two affected males in the same family identified a deep intronic variant in ZIC3 (NC_000023.11(NM_001330661.1):c.1224+3286A>G) segregating with disease phenotype. The intronic variant was highly predicted to alter RNA splicing by generating a 3′ cryptic splice acceptor, which could potentially result in pseudoexon inclusion. A minigene splicing assay confirmed that this nucleotide substitution in ZIC3 acts as a cryptic splice acceptor. CRISPR-Cas9 technology served to introduce the ZIC3 intronic variant into human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) to further study its effect on RNA splicing. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) as well as Sanger sequencing analyses revealed this variant simultaneously triggers multiple abnormal splicing events, multiple non-canonical exons, and multiple unique isoforms not detected in control hESCs. Several of the isoforms bypass the normal coding sequence of the third exon of ZIC3, thereby disrupting a ZF DNA-binding domain and an NLS sequence. Both in vitro and in vivo functional studies provided evidence that these isoforms behave abnormally compared with the control ZIC3 isoform.

The results demonstrate the ZIC3 intronic variant (NC_000023.11(NM_001330661.1):c.1224+3286A>G) is disease causative by severely disrupting ZIC3 RNA splicing, and these findings implicate pseudoexon inclusion in ZIC3 as a cause of X-linked heterotaxy.

Subjects, material, and methods

Human subjects

DNA of available family members was extracted from whole peripheral blood leukocytes following a standard protocol. The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at Baylor College of Medicine (IRB protocol H-1843) and Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) approved this study (IRB protocol 1403871897). Written informed consent for participation in this study and publication of clinical data of the patients was obtained. All medical research involving human subjects in this study conform to World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (1964).

WGS library preparation, variant calling, and filtering

WGS libraries were prepared from males (IV-1 and IV-18; Figure 1A) by the IUSM Center for Medical Genomics (CMG) using the Illumina Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were assessed for quantity and quality using Qubit and Agilent TapeStation analysis and then sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 using S4 flow cell with 2 × 150-bp paired-end reads. Variants were called by the IUSM CMG. Illumina adapter sequences and low-quality base calls were removed with Trim Galore and high-quality reads were aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 using BWA-MEM (v0.7.15).35 Variants were detected using Sentieon, which included duplicated reads marking, indel realignment, base quality score recalibration, genomic variant call format file generation, and joint genotyping of multiple samples. The joint-genotyped variant call file was further processed with variant quality recalibration score and variants that passed filters were functionally annotated with annotate variation (ANNOVAR) using various databases.36 The joint-genotyped variant call file was imported into Golden Helix SNP & Variation Suite version 8.9.0 (Golden Helix to identify potential disease-causing variants. Variants were filtered as shown in Figure S1. After filtering, five exonic variants were identified. Out of the five exonic variants, three were missense variants, including one in FAM236C (NM_001351111.1:c.223C>T; NP_001338040.1:p.R75W) and two in GAGE10 (NM_001098413.3:c.31C>T; NP_001091883.3:p.P11S and NM_001098413.3:c.44G>T; NP_001091883.3:p.R15L). Initial protein predictions analysis using Polyphen-2 and Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT) provided conflicting interpretations. The last two were exonic synonymous variants with one each in FGF16 (NM_003868.2:c.168A>G; NP_003859.1:p.L56=) and GAGE10, NM_001098413.3:c.48C>T, NP_001091883.3:p.Tyr16=). Initial attempts to analyze these synonymous variants using FATHMM-XF were unsuccessful as the program is unable to provide predictions for allosomal chromosomes. Further review in the most updated version of the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v4.0.0) revealed they are more common than the initial filtering analysis suggested. Inspection of the 281 intronic and UTR variants identified three variants located in CHD associated genes: GPC3 (NC_000023.11(NM_004484.3):c.1292+10480T>C), MID1 (NC_000023.11(NM_033290.3):c.-57+62927G>T), and ZIC3 (NC_000023.11(NM_001330661.1):c.1224+3286A>G). The ZIC3 variant was selected as the top candidate because of its known role in heterotaxy.

Figure 1.

Intronic variant in ZIC3 identified by WGS of an X-linked heterotaxy pedigree

(A) A pedigree with four heterotaxy-affected males (black squares) displaying an X-linked recessive inheritance pattern. Generations are labeled I–IV while individuals within each generation are numbered from 1 to 20. Deceased individuals are denoted with a diagonal line with the cause of death indicated as “d.” when available. X-exome sequencing (dashed orange outer frame) performed on two separate trios did not identify a coding variant in ZIC3, while WGS (solid blue outer frame) completed on two males with heterotaxy (IV-1 and IV-18) revealed a ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G intronic variant. A + W, alive and well; CHD, congenital heart defect; CL, cleft lip; CP, cleft palate; E, encephalocele; GA, gestational age; IUFD, intrauterine fetal demise; IVF, in vitro fertilization; MAB, missed abortion; P, pregnancy; SAB, spontaneous abortion; SAB 2/2 PA, spontaneous abortion secondary to placental abruption; VSD; ventricular septal defect; wk, week.

(B) Schematic diagram of IV-1 and IV-18 WGS and variant filtering steps (Figure S1) identifying ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G as a plausible disease-causing variant.

(C) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the predicted 3′ splice acceptor site in III-14, III-15, and IV-18. The sequence at the ZIC3 c.1224+3286 position is denoted as a black arrow for the father (ZIC3 c.1224+3286A), a red arrow for the hemizygous male with heterotaxy (ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G), and a blue arrow for the heterozygous mother.

(D) ZIC3 contains four exons with the untranslated regions (UTRs) shown as checkerboard-colored rectangles. The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant is located within the intronic region between exons 3 and 4 and it is predicted to result in a cryptic 3′ splice acceptor sequence (see also Table S6). Predicted intronic and exonic sequences are shown in lowercase and capital letters, respectively. The mutated “g” in ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G is shown in bold red while the predicted “ag” cryptic splice acceptor caused by the variant is underlined.

Sanger sequencing of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G genomic region

The genomic region containing the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant was amplified as described above using the following primers: ZIC3_SNP1_F51, 5′-TGA ATG CGG TTG AAG CAG TCT-3′ and ZIC3_SNP1_R52, 5′-AAC CCA TGG CTC TAC TTC CAC-3′. Sanger sequencing was performed by ACGT for all individuals with DNA available: III-2, III-1, IV-1, III-14, III-15, IV-18, II-2, III-4, and III-6.

Design and generation of ZIC3 minigene plasmids

Minigene plasmids were designed based on previously published methods.37 High-fidelity gene fragments containing each of the minigene sequences were designed and ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Two ZIC3 exon 2 to pseudoexon 1 (P1) constructs were acquired: (1) ZIC3 c.1224+3286A reference sequence and (2) ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant sequence (Figure S2A). Four additional constructs (controls and tests) were designed to ensure sufficient splice-site recognition sequences were present in the ZIC3 exon 2 to pseudoexon constructs (Figures S2B and S2C). Each of the six gene fragments was inserted into pUCIDT-AMP+ plasmids using the vector’s EcoRI restriction site. Full-length sequences are provided in Excel File S1, and plasmid maps are available upon request.

Each minigene plasmid was transformed as described above and sequences were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (ACGT) with the following primers: M13F, 5′-GTA AAA CGA CGG CCA GT-3′; M13R, 5′-GGA AAC AGC TAT GAC CAT G-3′, N500-RTPCR-F2: 5′-ACG CCA AGT TAT TTA GGT GAC A-3′; and N500-RTPCR-R1, 5′-CAA ATG TGG TAT GGC TGA TTA TG-3′.37

ZIC3 minigene splicing assessment

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells (CRL-1573; ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) (Cytiva) and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) in six-well plates (Corning) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Once cells reached 70%–90% confluence, each well was transfected with 4.5 μg of one of the six minigene plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following vendor’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to merchant’s specifications and purified to select for mRNA with the Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT kit (Thermo Fisher) using published methods.37 cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) with primer N500-RTPCR-R1 (see prior section for sequence). The FastStart PCR master mix (Roche) served to amplify cDNA using primers specific to the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and SV40 poly(A) tail regions of each minigene construct: N500-RTPCR-F2 and N500-RTPCR-R1 (see prior section for sequences) under standard conditions. Assessment of splicing was performed visually via agarose gels and further confirmation of abnormal splicing between exon 2 to P1 of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant sequence from the minigene plasmid amplicons was accomplished by Sanger sequencing (ACGT).

ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G and ZIC3 knockout (KO) H1-OCT4-EGFP cell lines

H1-OCT4-eGFP cells were purchased from WiCell and sent to the Genome Engineering & Stem Cell Center (GESC) at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM; St. Louis, MO) to generate both cell lines: ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G H1-OCT4-EGFP and ZIC3 KO H1-OCT4-EGFP. Karyotyping (performed by WiCell) and short tandem repeat (STR) profiling (performed by GESC) served to confirm cell line identity. The sequence of the guide RNA (gRNA) for the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G cell lines was the following: 5′-TGG CAT TCA GGC TTG GAT ATT GG-3′. The wild-type (WT) ZIC3 c.1224+3286A is located within the seed sequence of the gRNA and is underlined above. The single-stranded oligo DNA nucleotide (ssODN) sequence was the following: 5′-CTT TGG AGG CTA TTT TTT GTT AGT GGA GAA TAA TGG GGT CTT TTG CAT TTT CTT CCA CCA GTA TCC AAG CCT GAA TGC CAT GAA CAG AGA TTG GGA TGA CTA CAC ATG TGA TGA GCA GGT A-3′. The ssODN sequence corresponds to chrX:137,572,291-137,572,411 (GRCh38/hg38) with the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant located at chrX:137,572,351 A>G and underlined in the ssODN sequence above. H1-OCT4-EGFP cells were seeded into a six-well plate and passaged at least twice before nucleofection. For each reaction, 0.2 nmol of gRNA was complexed with 20 μg of Cas9 to form the ribonucleoprotein then mixed with 0.1 nmol of the ssODN and nucleofected into 1–1.5 million cells using a 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza Bioscience). Knockin efficiency was confirmed by next-generation sequencing (NGS), followed by cell sorting into single-cell clones. The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant was screened in each individual clone via NGS with primers MM219.h.ZIC3.F, 5′-ACA TTT TTG TAT TTG GTG CCT GA-3′ and MM219.h.ZIC3.R, 5′-GCA CCC TCA ATG TCA AGG TC-3′. After confirmation, the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G edited clones underwent STR profiling. Two clones were provided: ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 AtoG_C2.

Two ZIC3 KO clones in H1-OCT4-eGFP cells were generated using similar methods to those described above. The gRNA sequence 5′-GCG GCG CAC GAT CTA TCT TCA GG-3′ was located within the first exon of ZIC3. Individual clones were sequenced via NGS with primers MM220.h.ZIC3.F, 5′-CGA GAT GCC CAA CCG TGA G-3′ and MM220.h.ZIC3.R 5′-GCC CGG GAA ACA GCA AGT A-3′. After selection, two KO clones, ZIC3 KO_C1 and ZIC3 KO_C2, underwent STR profiling. Both clones contained frameshift variants (ZIC3 KO_C1: NM_003413.4:c.190_200delinsG, NP_003404.1:p.H64Vfs∗156, chrX:137,566,881_137,566,891delinsG [GRCh38/hg38]; ZIC3 KO_C2: NM_003413.4:c.200_201del, NP_003404.1:p.S67Ffs∗62, chrX:137,566,891_137,566,892del [GRCh38/hg38]) resulting in the loss of all five ZF DNA-binding domains and a premature stop codon within the first exon of ZIC3. The H1-OCT4-eGFP cells are a male cell line and therefore all ZIC3 AtoG and KO cell lines are hemizygous for their respective variants.

hESC cultures

WT, ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G, and ZIC3 KO H1-OCT4-EGFP cells were cultured following the WiCell Feeder Independent Stem Cell Protocols using geneticin (G418 sulfate; Gibco) standard operating procedure 208 version 2.0. Briefly, six-well plates (Corning) were coated with Matrigel Matrix (growth factor reduced) diluted in DMEM/F-12, HEPES media (Invitrogen). After thawing, cell lines were cultured in Matrigel-coated six-well plates with mTeSR1 media (STEMCELL Technologies). Cells were maintained in mTeSR1 medium for an additional 24 h then replaced with mTeSR1 medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL of geneticin (mTeSR1-G). Cells were dissociated using Versene solution (Gibco) and collected for further experiments.

RNA isolation and Sanger sequencing from hESCs

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) followed by column purification with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen). For the initial splicing assessment, mRNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) with either the oligo(dT)20 or random hexamer primers according to manufacturer’s recommendations. The FastStart PCR master mix (Roche) served to amplify the cDNA using the same forward primer ZIC3 exon 1-F1, 5′-GGC AGC CTA TCA AGC AGG AG-3′ combined with one of the following reverse primers: ZIC3 exon 3-R1, 5′-GTT GTG GCT GGT GCT AGT TT-3′; ZIC3 exon NC-R1, 5′-CAG CAC CCT CAA TGT CAA GG-3′; ZIC3 exon NC-R2, 5′-GTT CAT GGC ATT CAG GCT TGG-3′; ZIC3 exon 4-R1, 5′-TGC ACA GTA GGT TCG GCA TT-3′ under standard PCR conditions. Amplicons were purified as previously described and Sanger sequencing (ACGT) performed using the primers listed above.

Short-read RNA-seq of hESCs

Short-read RNA-seq was completed by the IUSM CMG. Total RNA was extracted from WT, ZIC3 AtoG_C1, ZIC3 AtoG_C2, ZIC3 KO_C1, and ZIC3 KO_C2 H1-OCT4-EGFP cells. The RNA integrity number (RIN) was determined using an Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies) followed by an RNA purification step with the KAPA RNA HyperPrep kit (Roche). cDNA libraries were prepared using the NovaSeq 6000 SP Reagent kit v1.5 (300 cycles) and sequenced using the NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) with 2 × 150-bp paired-end reads. Results were aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 reference genome using two passes of the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) aligner, version 2.7.10b,38 and visualized in the Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV).39

Long-read RNA-seq of hESCs

Long-read RNA-seq was performed by the Genome Access Technology Center at WUSM. Total RNA was extracted from control (ZIC3 WT) (n = 3), ZIC3 AtoG_C1 (n = 3), and ZIC3 KO_C1 (n = 3) H1-OCT4-EGFP cells and the RIN determined with an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Sequencing libraries were prepared with the PCR-cDNA Barcoding kit SQK-PCB111.24 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), and the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) served for quality assessment. Cell samples were pooled together on three PromethION R9.4.1 flow cells (50 fM/flow cell) and sequenced in a PromethION 24 A100 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) for 90 h using the following software: MinKNOW v22.12.5, Bream v7.4.8, Configuration v5.4.7, Guppy v6.4.6, and MinKNOW Core v5.4.3. Bases were called using Guppy v6.4.6 running the super-accurate basecalling model, 450 bp setting. Results were aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 reference genome using minimap240 and visualized in IGV.39 Differential expression analysis was conducted using the R package edgeR (version 4.0.2) comparing undifferentiated ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 AtoG_C1, and ZIC3 KO_C1 H1-OCT4-eGFP cells.41 A false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted p-value cutoff of 0.01 was used to denote differentially expressed (DE) genes. Overrepresentation analysis of biological processes (BPs) Gene Ontology (GO) terms was performed using the R package topGO (version 2.54.0) with the weight01 Fisher algorithm with a p-value cutoff of 0.05.42 Full characterization and quantification of the abnormal ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G transcripts was attempted using StringTie with long-reads alone43 and in mixed mode (combining short and long reads).44

N-terminal hemagglutinin-tagged ZIC3 plasmids

The ZIC3 plasmids encoding WT ZIC3 isoform 1 (ZIC3 WT; GenBank: NM_003413.4; NP_003404.1), ZIC3 p.H286R (NM_003413.4:c.857A>G; NP_003404.1:p.H286R), and ZIC3 p.T323M (NM_003413.4: c.968C>T; NP_003404.1:p.T323M) have been previously published and are within pHM6 vectors (Roche) containing an in-frame N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag.12 The ZIC3 WT plasmid served as a backbone vector to synthesize all four ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms (GenScript; Piscataway). GenScript’s standard gene synthesis generated a portion of the coding sequence of three of the four splicing patterns (SPs): ZIC3_SP1 (NP_003404.1:p.V409Mfs∗4), ZIC3_SP2 (NP_003404.1:p.V409Yfs∗61), and ZIC3_SP4 (NP_003404.1:p.W465Cfs∗26). The synthesis began at a SacII site present in the first exon of ZIC3 and concluded with an added BamHI restriction site. Each sequence was then subcloned into the ZIC3 WT plasmid12 using the SacII and BamHI restriction sites. The ZIC3_SP4 (NP_003404.1:p.W465Cfs∗26) vector underwent GenScript’s Express Mutagenesis service to produce a vector containing the coding sequence of the third splicing pattern: ZIC3_SP3 (NP_003404.1:p.W465∗). Vector transformations and DNA purification were performed as described above, and sequences were confirmed via Sanger sequencing (ACGT) with primers T7, 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG-3′; BGH reverse, 5′-TAG AAG GCA CAG TCG AGG-3′; ZIC3_196F, 5′-CTA TCT TCA GGC CAG AGC-3′; and ZIC3_297R, 5′- GCT GGT GTG GTG ATG ATG GTG-3′. Complete vector sequences are provided in Excel File S2, and plasmid maps are available upon request. Plasmids were linearized using the BamHI-HF (ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 p.H286R, ZIC3 p.T323M) and XbaI (four isoforms) restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs), respectively, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Linearized plasmids served to generate mRNA using the mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Invitrogen). Poly(A) tails were added and mRNA concentrations determined as described above.

Western blots

Cells were collected and lysed in Pierce RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technologies). Protein concentration was determined from the supernatant using the Bradford assay45 with bovine serum albumin (BSA; Bio-Rad Laboratories) as standard. The western blot procedure has been described previously46 with minor modifications. Primary antibodies were as follow: anti-HA tag rabbit polyclonal (NB600-363; Novus Biologicals; 1:2,000 dilution) for cells transfected with N-terminal tagged ZIC3 plasmids, and an anti-ZIC3 rabbit polyclonal (ab222124; Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution) for the H1-OCT4-eGFP cell lines. An anti-GAPDH rabbit polyclonal (ab9485; Abcam; 1:10,000 dilution) served as loading control. The chemiluminescent signal was detected using the ChemiDoc Touch Imaging system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and densitometry was performed using the Image Lab software version 6.1.0 build 7 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and graphed with GraphPad Prism, version 10.0.3 (275).

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) HI-FBS (Cytiva) and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) in two-well chamber slides at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transfections were performed when cells reached 80%–90% confluency with 1.5 μg of one of the plasmids described above. After 24 h, cells were fixed and stained as previously described12 with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were first incubated with an anti-HA tag rabbit polyclonal antibody (NB600-3363; Novus Biologicals; 1:250 dilution in PBS). After washes, cells were incubated with an Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (A-11012; Thermo Fisher; 1:500 dilution) and the Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated phalloidin (A12379; Invitrogen; 1× concentration) diluted in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA. VECTASHIELD Vibrance Antifade with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) served as mounting medium. Cells were imaged using a Leica DM4 B upright fluorescence microscope equipped with a Leica DMC2900 digital camera (Leica Microsystems). Three biological replicates were performed as set of transfections and were carried out on different days with at least 100 cells imaged for each transfection. Cell images for each HA-ZIC3 construct were de-identified, randomized, and then scored as having nuclear, cytoplasmic, or mixed (nuclear and cytoplasmic) localization.12,13 After scoring, images were reidentified. Statistical analysis was conducted using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (GraphPad Prism, version 10.0.3 [275]).

Luciferase assay

HEK-293 cells were cultured into 12-well plates (Corning) as described above. Once cells reached 80%–90% confluence, each well was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as follows. The pGL3-SV40 (Promega) reporter plasmid (700 ng) in combination with 700 ng of one of the subsequent expression plasmids: ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 p.H286R, ZIC3 p.T323M, ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4), ZIC3_SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61), ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗), and ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26). Each transfection reaction also received 100 ng of the pGL4.74[Rluc/TK] (Promega) Renilla luciferase as transfection control. The pHM6-empty as well as the pGL3-Basic (without the SV40 promoter) vectors served as controls. Medium was changed 6 h post transfection and cells were re-plated in solid white flat-bottomed 96-well plates (Corning) in three technical replicates. Luciferase activity was assessed 24 h post transfection with the Dual Glo Luciferase assay system (Promega) and luminescence measured in an Agilent BioTek Synergy H4 MicroPlate reader using Agilent BioTek Gen5 version 3.11 software (Agilent Technologies). Firefly luminescence was normalized to Renilla luminescence for each well. Three biological replicates were performed (each condition with three technical replicates) and data analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism, version 10.0.3 [275]).

ZIC3 mRNA injections into X. laevis

General methods regarding the housing and injecting of adult frogs as well as methods for Xenopus embryo collection and scoring are described in the supplemental information. For the ZIC3 experiments, embryos were injected with mRNA encoding ZIC3 isoform 1 (50 pg/cell; 100 pg/embryo), or mRNAs encoding the four ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms (50 pg/cell; 100 pg/embryo). Uninjected embryos served as controls.

In vitro MO experiments

Two vivo-MOs (Gene Tools) that contained an octa-guanidine-dendrimer delivery moiety allowing for uptake in cells without the need for transfection47 were used in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells. The splice-blocking vivo-MO (5′-GGC TTG GAT ACT GGT GGA AGA AAA TGC A-3′) targets the cryptic acceptor site directly caused by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant (location underlined). A scramble vivo-MO (5′-GAG AGA AGA GAC TCG ATG TTC AGG ATT G-3′) served as control. ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells received either splice-blocking or scramble vivo-MOs at a final concentration of 10 μM in mTeSR1-G. ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells were treated for either 24 or 48 h with the vivo-MOs, followed by a 24 h of recovery in fresh mTeSR1-G. For the 48-h treatment, cells received the vivo-MOs in fresh mTeSR1-G for an additional 24 h followed by a 24-h recovery in fresh mTeSR1-G. ZIC3 WT (non-edited cells) and non-treated ZIC3 AtoG_C1 were also included as controls. Cell pellets were collected for western blot analysis.

Results

The GPR101 c.1225G>A; p.V409M variant uncovered by X-exome sequencing does not explain the heterotaxy phenotype

An X-linked heterotaxy pedigree with four affected males of Mexican-American descent with no evidence of consanguinity was identified (Figure 1A). The heterotaxy phenotype of the affected males was determined by the presence of complex CHDs such as dextrocardia and double-outlet right ventricle along with abnormal organ laterality such as asplenia and gut malrotation. Detailed clinical assessment information is provided in the supplemental note: case reports and Table S1. X-exome sequencing conducted in two trios identified a rare, missense, hemizygous variant in GPR101 (NM_054021.1:c.1225G>A, NP_473362.1:p.V409M) segregating with disease phenotype (Figures 1A and S3). Initial functional studies were performed in X. laevis since LR patterning is highly conserved among vertebrate species and X. laevis and Xenopus tropicalis are well-established models to study LR patterning.48 Knockdown of GPR101 by injecting two different morpholinos (MO-1 or MO-2) into X. laevis two-cell embryos showed that a significant number of tadpoles displayed abnormal organ situs when compared to uninjected controls (p < 0.0001 for both MO-1 and MO-2; Figures S4A–S4E; Videos S1, S2, S3, and S4; Table S2). Edema and reduced mobility were also frequently observed in developing tadpoles. As 100 pg/cell of GPR101 mRNA resulted in tadpoles with a heterotaxy phenotype (p < 0.0001; Figure S6F), injection doses of 25 pg/cell and 50 pg/cell of GPR101 mRNA were used for the RNA rescue experiments. However, significant situs defects, edema, reduced mobility, and reduced viability were observed despite the addition of GPR101 mRNA (Figure S4G).

Uninjected control X. laevis embryo presenting normal situs. Embryo shown in Figure S2A.

Two-cell-stage embryo injected with MO-1 at 8.0 ng/cell and scored at stage 47 of development (Figure S2B). The heterotaxy phenotype was based on reversed heart and left-origin gut with clockwise gut coiling toward interior, in addition to edema.

Two-cell-stage embryo injected with MO-2 at 14.6 ng/cell and scored at stage 47 of development (Figure S2C). The isolated situs anomaly was based on left gut origin with clockwise gut coiling but normal heart looping and gallbladder position.

MO-2 injected embryo in Figure S2D, which displays a heterotaxy phenotype (abnormal gut with absence of gallbladder).

Next, a global Gpr101 knockin mouse with an inserted LacZ reporter (Gpr101tm1b(KOMP)Mbp)34 was acquired to corroborate our initial heterotaxy findings in X. laevis. The Gpr101 tm1b allele lacks the entire coding sequence of Gpr101 (Figure S5) and it is expressed in a similar pattern to the WT Gpr101 allele as demonstrated by RT-PCR and X-gal staining (Figure S6), confirming previous findings.49 No potential embryonic lethality for the Gpr101 tm1b null mice was detected by chi-squared power analyses—over 270 Gpr101 tm1b null mice were born without any apparent defects—and genotyping ratios for various crosses do not deviate from the expected Mendelian ratios. Moreover, Gpr101tm1b/Y males can breed with Gpr101tm1b/tm1b females and produce viable, fertile offspring (Tables S3–S5). Finally, dissection of Gpr101 tm1b null mice did not reveal any laterality defects (n = 20 of ∼2–7 months of age) and LacZ expression was absent during time points critical for LR patterning in these mice (unpublished data). Thus, although knockdown of GPR101 results in LR patterning defects in X. laevis, Gpr101 is dispensable for LR patterning in mice.

WGS uncovered a deep intronic variant in ZIC3 (ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G) predicted to alter splicing

Since the loss of function of Gpr101 in mice did not cause embryonic lethality, heterotaxy, or affect LR patterning as seen in Zic3 null mouse models,10 it is unlikely that GPR101 c.1225G>A; p.V409M is the heterotaxy-causing variant in this pedigree. Hence, the phenotype may be explained by a variant in a separate gene not previously associated with X-linked heterotaxy or a non-coding variant in ZIC3 altering its expression or RNA splicing. WGS was performed in the two males with X-linked heterotaxy (IV-1 and IV-18), and after variant filtering a total of five exonic variants on the X chromosome were identified, of which two were synonymous and the remaining three were missense variants. These variants were not well annotated in reference databases during the initial filtering; however, in the most recent version of gnomAD (v4.0.0), they have now been reported either as homozygous or hemizygous in several individuals, indicating their unlikelihood to explain the heterotaxy phenotype of the family (Figures 1B and S1, and data not shown). Variants located in introns and UTRs were then examined with focus on genes previously associated with CHDs. This led to candidate variants in GPC3, MID1, and ZIC3. Variants in GPC3 and MID1 are associated with Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, type 1 (MIM: 312870) and Opitz G/BBB syndrome (MIM: 300000), respectively. Patients with these syndromes can present with CHD but often have other characteristic phenotypes not present in the individuals of this study. For example, the affected individuals in the X-linked heterotaxy pedigree have neither overgrowth nor coarse facial features, common in Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, type 1. Ocular hypertelorism, cleft lip or palate, or laryngo-tracheo-esophageal abnormalities, frequently associated with Optiz G/BBB syndrome, were also not present. RNA-splicing bioinformatic analysis of GPC3 and MID1 variants (NC_000023.11(NM_004484.3):c.1292+10480T>C and NC_000023.11(NM_033290.3):c.-57+62927G>T, respectively) suggest they are unlikely to have a functional impact (data not shown), and gnomAD v4.0.0 showed they are present as hemizygous and homozygous variants in several individuals.

The third and top candidate variant was a deep intronic variant in ZIC3 (NC_000023.11(NM_001330661.1):c.1224+3286A>G, NC_000023.11(NM_003413.4):c.∗2281A>G, NC_000023.11:g.137572351A>G, ClinVar assession SCV005038948) (Figures 1B and S1). To date, this variant remains absent in gnomAD v4.0.0. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the ZIC3 variant and that it segregates with disease phenotype (Figures 1C and S7). The ZIC3 variant (hereafter referred to as ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G) is located between exons 3 and 4 and it was predicted by 10/10 splicing prediction programs including Alternative Splice Site Predictor, Human Splicing Finder, MaxEntScan, NetGene2, NNSPLICE, regSNP-intron, SpliceAI, Spliceator, SVM-BP finder, and varSEAK to result in the formation of a 3′ cryptic splice acceptor site (Figure 1D; Table S6).

Minigene splicing assay confirmed ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G generates a 3′ splice acceptor

Since the variant is predicted to create a 3′ splice site in an intronic region, we hypothesized this could result in the inclusion of a pseudoexon (P1). As patient tissue was unavailable, an in vitro minigene splicing assay37 was used to determine if the variant alters RNA splicing between exon 2 and P1 directly (Figure 2). There are two ZIC3 isoforms: isoform 1 (NM_003413.4), which is the dominant isoform, encoded by exons 1, 2, and 3, and isoform 2 (NM_001330661.1) encoded by exons 1, 2, and 4 (Figures 2A and 2B).50 The ZIC3 isoforms only vary in the alternative splicing occurring at the terminal exons; therefore, the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant would result in a predicted isoform encoded by exons 1, 2, and P1 with a C-terminal amino acid sequence, which causes the disruption of a ZF DNA-binding domain and an NLS sequence. After the predicted stop codon in P1, we identified three potential polyadenylation sites implying that the predicted ZIC3 isoform may be stable in vivo.

Figure 2.

The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant acts as a 3′ splice acceptor between exon 2 and the predicted P1 in a minigene assay

(A) Illustrative representation of ZIC3 showing the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant predicted to result in a 3′ cryptic splice acceptor that causes the inclusion of P1.

(B) ZIC3 encodes two isoforms: isoform 1 formed by exons 1-2-3 (dominant isoform), and isoform 2 encoded by exons 1-2-4. The ZIC3 predicted isoform is expected to be encoded by exons 1-2-P1.

(C) Minigene plasmids contain a 1,289-bp minigene construct composed of a CMV promoter (brown and white checkerboard pattern), exon 2 (final 40-bp portion, green), intron (140 bp, gray), P1 (255 bp, predicted coding region of P1, red; predicted 3′ UTR region of P1, red and white checkerboard pattern), a 2-bp barcode sequence, and an SV40 poly(A) tail signal sequence (dark yellow and white checkerboard pattern). (Ci) The exon 2 to P1 control construct contains the reference ZIC3 c.1224+3286A sequence predicted to not alter splicing resulting in full intron retention. (Cii) The exon 2 to P1 construct containing the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant is predicted to generate a 3′ splice acceptor and remove the intron.

(D) Electrophoretogram of amplicons obtained by RT-PCR from amplified cDNA of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant construct, using primers located on the CMV promoter (brown arrow) and the SV40 poly(A) tail sequence (dark yellow arrow). The top amplicon (∼500 bp) corresponds to full intron retention, while the ∼360-bp amplicon represents intron removal. Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the ∼360-bp amplicon showing that the intronic region between exon 2 and P1 was removed.

Each minigene plasmid included a ∼500-bp exon 2-intron-P1 sequence containing either the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A reference sequence (Figure 2Ci) or the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant sequence (Figure 2Cii). cDNA amplified from cells transfected with the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A reference plasmid produced a ∼500-bp amplicon suggesting full intron retention (Figure 2Ci). In contrast, cDNA amplified from cells transfected with the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant plasmid had both a ∼500-bp and a ∼360-bp amplicon, which corresponds to the removal of the intronic region between exon 2 and P1 (Figure 2Cii). Sanger sequencing results from the ∼360-bp amplicon showed a lack of the 140-bp intronic sequence contained within the variant plasmid (Figure 2D). Thus, the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant created a 3′ splice acceptor site and resulted in abnormal splicing between exon 2 and the predicted P1 in a minigene construct in vitro.

Multiple splice isoforms are generated by the intronic ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant

To provide additional experimental information regarding splicing patterns caused by the variant and predicted ZIC3 pseudoexon isoform creation, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing was utilized in H1-OCT4-eGFP cells to generate two ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G cell lines (ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 AtoG_C2). H1-OCT4-eGFP cells are a normal male karyotype (46 XY) hESC line that contains an eGFP neomycin cassette inserted into the 3′ UTR of the pluripotency marker POU5F1 encoding OCT4,51 which allows for the maintenance of a pluripotent stem cell population by adding geneticin. In addition, two ZIC3 knockout H1-OCT4-eGFP cell lines (ZIC3 KO_C1 and KO_C2) were generated for comparison.

Western blots were performed to assess ZIC3 expression with an anti-ZIC3 antibody targeting amino acids encoded by the end of exon 3 of ZIC3 isoform 1 (amino acids 426–467 of NP_003404.1) (Figures 3A and 3B). The immunoreactive band with the highest intensity corresponds to ZIC3 (∼55 kDa). In both ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G and ZIC3 KO cell lines, ZIC3 expression was severely reduced, suggesting that the variant identified may act via loss of function. Two other immunoreactive bands were detected, which might correspond to ZIC2 (∼60–65 kDa) and ZIC4 (∼45 kDa) according to sequence homology among these proteins.

Figure 3.

ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant reduces level of ZIC3 isoform 1 and disrupts RNA splicing

(A) Illustrative representation of ZIC3 showing the immunogen region of the ZIC3 polyclonal antibody (pAb) used in (B), which corresponds to the terminal 42 amino acids of exon 3 and the location of forward and reverse primers (blue and red arrows, respectively) used for preliminary splicing analysis in (C) and (D). AA, amino acids.

(B) Immunoblotting image of ZIC3 isoform 1 (∼55 kDa) detected in cell lysates from H1-OCT4-eGFP human embryonic stem cells (hESCs). The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G clones (ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and C2, respectively), as well as the ZIC3 knockout clones (ZIC3 KO_C1 and C2, respectively) were generated by CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The ZIC3 WT denotes non-edited H1-OCT4-eGFP hESC. Based on sequence homology, the bands at ∼60–65 kDa and ∼45 kDa might correspond to ZIC2 and ZIC4, respectively. GAPDH served as loading control.

(C) Electrophoretogram of amplicons obtained by RT-PCR from cDNA amplification of ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 AtoG_C1, and ZIC3 AtoG_C2 cells. Forward and reverse primers are in exon 1 and P1, respectively (blue and red arrows in A). NTC, no-template control. The asterisk denotes a 518-bp amplicon of the initially predicted ZIC3 isoform containing exons 1-2-P1. The four other amplicons correspond to the dominant splicing patterns between exon 1 and P1: ZIC3_SP1–ZIC3_SP4 (details in Figure S8).

(D) Sanger sequencing chromatogram of the 518-bp putative ZIC3 isoform containing exons 1, 2, and P1. The black dots interrupting the sequence of exon 2 represent a break so that the sequences of the junctions are displayed.

Based on the minigene results, RT-PCR was performed with primers located on exon 1 and the predicted P1 (Figures 3A and 3C). Surprisingly, five amplicons were visualized in the cDNA from ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G hESCs cells and Sanger sequencing results revealed that the intronic variant generates several isoforms (Figure 3D). The initially hypothesized splicing pattern between exons 1-2-P1 corresponds to the 518-bp amplicon (denoted with an asterisk in Figure 3C). Notably, this amplicon is fainter than the other amplicons visualized, suggesting it is a rare occurrence. The four other amplicons identified were named ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G splicing pattern 1, 2, 3, and 4 (ZIC3_SP1–ZIC3_SP4).

To fully characterize the abnormal splicing caused by the presence of the intronic variant, short- and long-read RNA-seq analysis was conducted in ZIC3 WT and ZIC3 AtoG_C1 H1-OCT4-eGFP cells (Figures 4A and 4B). As expected, the ZIC3 WT cells predominately expressed ZIC3 isoform 1, while isoform 2 is less frequent. Remarkably, RNA-seq analysis of the ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells revealed multiple, abnormal splicing events and additional exons absent in ZIC3 WT cells (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Unique isoforms generated by splicing events in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells

(A and B) Integrative Genomics Viewer image of the chromosome X range 137,566,444–137,578,187 (GRCh38/hg38) showing Sashimi plots for ZIC3 generated from short-read (Ai and Bi) and long-read (Aii and Bii) RNA-seq analysis from ZIC3 WT (green) and ZIC3 AtoG_C1 (red) cells. The junction coverage minimum was set to 20 and 10 for short and long reads, respectively. The ZIC3 c.1224+3286 genomic position is denoted with an arrow.

(C) Illustrative diagram depicting splicing events caused by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant. Exons generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant are illustrated as follows: exon 3T(170) (orange, a 170-bp truncated exon 3), exon 3A(163) (gold, a 163-bp alternative exon located in the 3′ UTR of exon 3), exon 3A(227) (dark blue, a 227-bp alternative exon located in the 3′ UTR of exon 3), P1(57) (red, a 57-bp P1 where the 3′ splice acceptor is caused by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant), P2(151) (pink, a 151-bp pseudoexon 2), and exon 4L(1792) (dark pink, a 1,792-bp longer version of exon 4).

In ZIC3 AtoG_C1, exon 1 can splice to exon 2. Exon 2 can then splice to one of three locations. The first location is the canonical splice acceptor of normal exon 3. However, exon 2 can also splice to one of two cryptic splice acceptors located within the 3′ UTR of exon 3. This results in the formation of two alternative exons in exon 3 of either 163 bp (exon 3A(163)) or 227 bp (exon3A(227)).

The sequence of exon 3A(163) overlaps exon 3A(227), but their difference in length is based on the normally inactive 3′ splice acceptor utilized of which exon 3A(227) uses a further upstream 3′ splice acceptor compared with exon 3A(163). Both 3A(227) and 3A(163) then use the same normally inactive 5′ splice donor to splice to P1(57), a 57-bp P1 located within an intronic region that uses the 3′ splice acceptor site directly generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant.

In ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells after exon 2 splices to the canonical splice acceptor of normal exon 3, abnormal splicing caused by the utilization of a normally inactive splice donor site present before the stop codon of exon 3 can also occur, resulting in the formation of a 170-bp truncated version of exon 3 (exon 3T(170)). The cryptic splice donor for exon 3T(170) can then splice to exon 3A(163) and exon 3A(227). Exon 3A(163) and exon 3A(227) then use a shared 5′ donor splices site, as previously described, to reach the 3′ splice acceptor directly generated by the variant, leading to the inclusion of P1(57).

Intriguingly, while the cDNA amplification showed faint evidence for splicing between exon 2 and P1 directly as initially hypothesized (asterisk in Figure 3C), this splicing pattern was not seen in the RNA-seq analysis (Figures 4B and 4C).

Downstream of the variant, P1(57) utilizes a 5′ donor splice site to reach additional loci within the intronic region between exons 3 and 4. These include a second pseudoexon of 151 bp (P2(151)) and a version of exon 4 (4L(1792)) that is 1792 bp and that utilizes an upstream, cryptic 3′ splice acceptor. P1(57) may also splice directly to the normal 3′ splice acceptor of exon 4.

Surprisingly, the 3′ splice acceptor directly caused by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant is the only additionally created splice site in the ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells. The sequences of the other splice sites utilized by the various additional exons are normally present in ZIC3 WT cells and normally present in the reference genome yet are inactive. Thus, the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant not only directly generates a 3′ splice acceptor but simultaneously triggers multiple cryptic splice sites throughout ZIC3 to become active, resulting in the formation of multiple abnormal isoforms not present in ZIC3 WT cells.

Using the short- and long-read RNA-seq data, we attempted to fully identify and quantify the relative abundance of the various ZIC3 transcripts. However, the long-read sequencing data had a consistent 3′ end coverage bias previously reported for Oxford Nanopore sequencing data52 causing a loss of reads covering exon 1 regardless of cell genotype (ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 AtoG_C1, and ZIC3 KO_C1). In contrast, this truncation was not as prevalent in the short-read data, which suggests the reduced coverage of exon 1 in the long-read data may be a sequencing artifact. Manual review of the splice junctions present in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells suggests that at least 12 abnormal transcripts can occur (Figure 4C).

Further assessment of the four cDNA amplicons ZIC3_SP1–ZIC3_SP4 via Sanger sequencing confirmed these bands were produced by abnormal splicing between exon 1 and P1 by utilizing four exons unique to ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 AtoG_C2 cell lines in several different combinations (Figures 3C and S8; Files S1 and S2).

ZIC3_SP1 (∼681-bp amplicon) contains exons 1-2-3A(163)-P1(57). This splicing pattern results in a premature stop codon 10 bp into exon 3A(163) with a predicted protein sequence NP_003404.1:p.V409Mfs∗4.

ZIC3_ SP2 (∼745 bp amplicon) is created by splicing between exons 1-2-3A(227)-P1(57). This splicing pattern results in a premature stop codon 180 bp into exon 3A(227) with a predicted protein sequence NP_003404.1:p.V409Yfs∗61.

Both ZIC3_SP1 and SP2 completely bypass the normal coding sequence of exon 3, resulting in the loss of an NLS sequence and a ZF DNA-binding domain.

ZIC3_SP3 (∼851-bp amplicon) is composed of exons 1-2-3T(170)-3A(163)-P1(57). This splicing pattern produces a stop codon spanning the junction of exon 3T(170) to 3A(163). The coding sequence of this splicing pattern, NP_003404.1:p.W465∗, is highly similar to ZIC3 isoform 1, only lacking three C-terminal amino acids. All NLS and ZF DNA-binding domains are fully intact.

ZIC3_SP4 (∼915-bp amplicon) is generated by splicing between exons 1-2-3T(170)-3A(227)-P1(57). This splicing pattern contains a premature stop codon 73 bp into 3A(227) encoding NP_003404.1:p.W465Cfs∗26. Given the inclusion of exon 3T(170), the sequence of all NLS and ZF DNA-binding domains remain in frame.

Notably, the four splicing patterns between exon 1 and P1 (Figure 3C) all contain premature stop codons before P1 (Figure S8). Therefore, the inclusion of P2(151), 4L(1792), and/or normal exon 4 are predicted to not have any effect on the coding sequence for any of the abnormal transcripts detected the RNA-seq analysis in the ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells.

Undifferentiated ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 KO_C1 cells have similar gene expression profiles

Long-read RNA-seq analysis served to compare the overall gene expression profile for the undifferentiated ZIC3 WT, ZIC3 AtoG_C1, and ZIC3 KO_C1 cell lines. As shown by the multidimensional scaling plot, there is a modest separation among the cell lines (Figure 5A), suggesting the undifferentiated cells largely have similar gene expression profile regardless of genotype. When comparing the expression profiles of undifferentiated ZIC3 WT and ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells, a total of 88 DE genes were identified, of which 58 were upregulated while 30 were downregulated in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 (Figure 5B; Excel File S3). For ZIC3 WT vs. ZIC3 KO_C1 undifferentiated cells, a total of 74 genes were DE with 39 and 35 upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Figure 5C; Excel File S3).

Figure 5.

Differential expression analysis suggests ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 KO_C1 cells have similar gene profiles

(A) Multidimensional scaling plot of undifferentiated ZIC3 WT (n = 3; blue), ZIC3 AtoG_C1 (n = 3; green), and ZIC3 KO_C1 (n = 3; red) H1-OCT4-eGFP cells. Each data point represents one RNA-seq sample, while the distance between any two samples corresponds to the leading logFC (base 2 logarithm of fold change, the average of the largest absolute logFC).

(B and C) Volcano plots of DE genes between (B) undifferentiated ZIC3 WT vs. ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells and (C) undifferentiated ZIC3 WT vs. ZIC3 KO_C1 cells. Blue and red dots denote downregulated and upregulated genes, respectively. An FDR-adjusted p-value cutoff of 0.01 was used to denote DE genes and the total numbers of downregulated and upregulated genes are shown.

(D) Venn diagram of the total number of DE genes between each comparison.

(E) Heatmap of the 40 genes that were DE in both ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells and ZIC3 KO_C1 cells relative to ZIC3 WT cells.

Of the 88 and 74 DE genes in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 KO_C1 cells, respectively, 40 genes were commonly DE in both cell lines relative to ZIC3 WT cells (Figure 5D). The heatmap shows the expression pattern of these 40 genes follow the same general trend in both mutant genotypes (Figure 5E). Of those 40 genes, the same 30 and 10 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively, in both mutant genotypes. The overlapping expression profiles suggest the abnormal isoforms produced by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant may collectively act via a loss-of-function mechanism in vivo.

GO term overrepresentation analysis in the mutant cell lines implied downregulation of BPs such as PCP signaling (PLEKHA4) (Figures S9A and S9C). ZIC3 AtoG_C1 and ZIC3 KO_C1 cells also displayed an overlap of upregulated BPs (Figure S9B). This includes genes involved in transcription initiation (MED10) as well as genes involved in a variety of metabolic processes (Figure S9C).

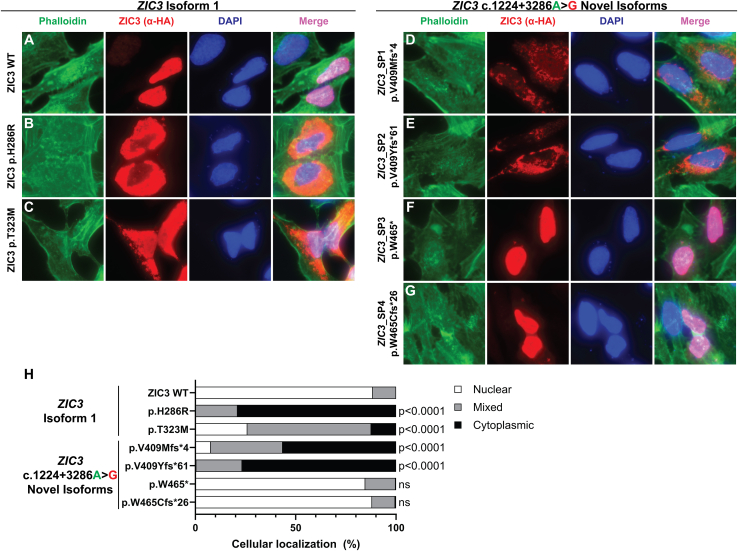

Assessment of cellular localization of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms

Proper nuclear localization as well as protein structure, including intact DNA-binding domains, are crucial for transcription factors to activate transcription. At the cellular level, ZIC3 isoform 1 is mostly localized in the nucleus, while the localization for ZIC3 pathogenic variants varies from either mainly nuclear or cytoplasmic to a combination of both.12,13,15,24,27 To assess the cellular localization of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms, the localization of each HA-tagged ZIC3 construct was tested in HeLa cells. As expected, ZIC3 WT mainly localized to the nucleus (88.3%; Figures 6A and 6H). Two previously published ZIC3 single-nucleotide variants (ZIC3 p.H286R and ZIC3 p.T323M)12 were included to compare their cellular localization to the isoforms identified. The ZIC3 p.H286R variant largely localized to the cytoplasm (78.9%; Figures 6B and 6H), while ZIC3 p.T323M had a more heterogeneous localization, with many of the transfected cells displaying a mixed (nuclear and cytoplasmic) distribution (Figures 6C and 6H). Both single-nucleotide variants were significantly different from ZIC3 WT (p < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

Cellular localization of ZIC3 isoforms

(A–G) Representative images of HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged ZIC3 plasmids encoding either (A) WT, (B and C) previously published single-nucleotide variants (p.H286R and p.T323M), or (D–G) the coding sequence of ZIC3 isoforms generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant. Cells were incubated with phalloidin (cytoplasmic marker, green), a rabbit α-HA tag (anti-HA, red), and DAPI (nuclear marker, blue). Merged images display nuclear localization of the HA-tagged ZIC3 isoforms in light purple color.

(H) The cellular localization was classified as either nuclear (white), cytoplasmic (black), or mixed (gray, both nuclear and cytoplasmic) and the results are presented as percentages. Transfections were performed in n = 3 separate experiments and at least 100 cells were imaged for each transfection each time. Images were randomized and deidentified for unbiased scoring and statistical analysis was conducted using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. ns, not significant.

The ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) and ZIC3_SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61) isoforms were primarily localized to the cytoplasm (p < 0.0001 vs. ZIC3 WT; Figures 6D, 6E, and 6H) with either a small percentage of cells displaying only nuclear localization or no nuclear localization, respectively. Notably, the staining for ZIC3 in the ZIC3_ SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61) transfected cells appeared to be diffuse and weaker when compared to the other isoforms. Both ZIC3_SP1 and ZIC3_SP2 isoforms bypass the normal coding sequence of exon 3, thereby disrupting the third NLS (Figure S8). In contrast, the ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) and ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) isoforms were primarily localized to the nucleus, similar to the ZIC3 WT expression construct. These isoforms retain most of the coding sequence of exon 3; therefore, the third NLS sequence was not disrupted by their splicing patterns (Figure S8).

The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms demonstrate differential protein abundance by western and differential luciferase reporter transactivation

To assess the protein stability of the isoforms, western blots were performed from cell lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with HA-tagged ZIC3 constructs. An antibody against the HA tag (α-HA; Figure 7A) revealed the presence of an intense protein band at ∼57–60 kDa in the ZIC3 WT sample. Moreover, immunoreactive protein bands at similar molecular weight were detected for the ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) isoform as well as for ZIC3 p.T323M and ZIC3 p.H286R single-nucleotide variant expression constructs. Notably, the protein band for isoform ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) was also highly intense. On the other hand, a ∼50-kDa protein band was identified for the ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) isoform, while the ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) isoform displayed an immunoreactive protein band at ∼63 kDa. Interestingly, no immunoreactive protein band was detected for isoform ZIC3_SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61). This is the same isoform with diffuse and weaker immunofluorescence signal in the cellular localization assessment experiments, indicating decreased abundance of this protein and suggesting reduced protein stability of the isoform.

Figure 7.

ZIC3 isoforms display differential expression and SV40 promoter activity

(A) Western blot image of HEK293 cells transfected with HA-tagged ZIC3 plasmids encoding ZIC3 isoform 1 (ZIC3 WT), the coding sequence of four ZIC3 isoforms generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant, or two previously published ZIC3 single-nucleotide missense variants (p.T323M and p.H286R). An untransfected control was also included. HA-tagged ZIC3 was detected using an antibody against the HA tag (α-HA). GAPDH served as a loading control.

(B) pGL3-SV40 firefly (SV40) luciferase reporter activity in HEK293 cells transfected with HA-tagged pHM6 plasmids encoding ZIC3 isoform 1 (WT), the two ZIC3 missense variants described above, or the coding sequence of abnormal ZIC3 isoforms. The pHM6-empty and pGL3-Basic without the SV40 promoter (no SV40) vectors served as controls. Results are presented as the mean of relative luminescence units (Firefly/Renilla) ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was conducted using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

Next, the functionality of each isoform was tested in a transactivation assay to assess their ability to activate the SV40 luciferase promoter in HEK293 cells. It is well known that ZIC3 increases the SV40 luciferase promoter activity.12,13,21,27 Results from our transactivation assay showed that, while ZIC3 WT increased the activation of the SV40 luciferase promoter, the ZIC3 p.H286R and ZIC3 p.T323M single-nucleotide variants reduced the luciferase activity, as expected12 (Figure 7B; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0021, respectively). Likewise, two of the four isoforms, ZIC3_SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61) and ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26), had reduced luciferase activity when compared to ZIC3 WT (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0102, respectively). In contrast, the ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) isoform significantly increased the SV40 promoter luciferase activity when compared to ZIC3 WT (p = 0.0051).

Despite the truncation of several amino acids in ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4), the luciferase activity was not different from ZIC3 WT control. It is important to note that, while some of the isoforms have similar cellular localization, their capability to activate the SV40 luciferase promoter significantly differs among all of them (i.e., ZIC3_SP1 [p.V409Mfs∗4] vs. ZIC3_SP2 [p.V409Yfs∗61]; p = 0.0012 and ZIC3_SP3 [p.W465∗] vs. ZIC3_SP4 [p.W465Cfs∗26]; p < 0.0001), which suggests that alteration of their sequence, and therefore structural configuration, elicits changes in their competence to induce promoter-like responses.

Most of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms cause situs anomalies in vivo

It is well established that overexpression of Zic3 mRNA in Xenopus embryos disrupts the normal situs in stage 47 tadpoles.53 Injections into both cells of two-cell-stage X. laevis embryos were performed and their hearts, guts, and gallbladders were assessed for situs defects to determine the effects of the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms (Figures 8A–8D; Videos S5, S6, S7, and S8).

Figure 8.

Situs abnormalities in X. laevis embryos injected with abnormal ZIC3 isoforms

(A–D) Representative images of X. laevis tadpoles (stage 47) that received at the two-cell stage one of the following: no injection (uninjected control [uninj. ctrl]) (E) in vitro synthesized mRNA encoding the coding sequence of HA-tagged ZIC3 isoform 1 (ZIC3 WT, 50 pg/cell; 100 pg/embryo), in vitro synthesized mRNA encoding the coding sequence of one of the four HA-tagged ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G isoforms (50 pg/cell; 100 pg/embryo). Situs defects were assessed by the position of the heart, gallbladder, and gut and categorized into one of four groups. (A) Normal situs tadpoles display normal heart looping (green dashed line), normal right gut origin and counterclockwise gut coil (yellow dashed line), and normal position of the gallbladder on the right (red dashed line). (B) Situs inversus tadpoles exhibit reversed heart looping, left gut origin with clockwise gut coil, and leftward gallbladder. (C) Isolated situs anomaly tadpoles have one organ defect (right-origin gut coil with clockwise rotation), while (D) heterotaxy tadpoles have two or more organ defects (reversed heart looping, a left gallbladder position, and a left gut origin with counterclockwise gut coil). Scale bars, 0.5 mm. Videos are provided as Videos S5, S6, S7, and S8. The Fisher’s exact test (two sided) served to calculate significance (p < 0.05) by comparing the number of embryos with normal situs to the sum of the number of embryos with abnormal situs (situs inversus, isolated situs anomaly, and heterotaxy). Raw counts used for statistical analysis are included in Table S7. ns, not significant.

Uninjected control X. laevis embryo presenting with normal situs (Figure 8A).

Two-cell-stage embryo injected with mRNA encoding ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) at 50 pg/cell and scored at stage 47 of development (Figure 8B). The situs inversus phenotype is based on a reversed heart looping, a left gallbladder position, and a left gut origin with clockwise gut coiling.

Two-cell-stage embryo injected with mRNA encoding ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) at 50 pg/cell and scored at stage 47 of development (Figure 8C). The isolated situs anomaly phenotype is based on a right-origin gut coil with clockwise rotation (vs. normally counterclockwise) toward the interior with normal heart looping and gallbladder position.

Two-cell-stage embryo injected with mRNA encoding ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) at 50 pg/cell and scored at stage 47 of development (Figure 8D). The heterotaxy phenotype is based on a reversed heart looping, a left gallbladder position, and a left gut origin with counterclockwise gut coil.

Tadpoles displayed abnormal situs (61.2%; p < 0.0001; Figure 8E) after injecting 50 pg/cell (100 pg/embryo) of mRNA encoding ZIC3 isoform 1 (ZIC3 WT). In contrast, embryos injected with 25 pg/cell of ZIC3 WT mRNA did not show significant increase in LR patterning defects at stage 47 of development, while 100 pg/cell resulted in death (data not shown).

Xenopus embryos were injected with mRNA encoding ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4), ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) or ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26). They exhibited significant situs defects relative to their respective uninjected controls (p < 0.0001). On the other hand, ZIC3_SP2 (p.V409Yfs∗61) mRNA injections failed to cause abnormal situs in tadpoles.

Note that, despite the statistical significance, the percentage of tadpoles with heterotaxy is less for the ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) than for ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) or ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) (12.1% vs. 37.1% and 40.9%, respectively). Likewise, the percentage of tadpoles displaying isolated situs anomaly is less for the ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) isoform than for the ZIC3_SP3 (p.W465∗) or ZIC3_SP4 (p.W465Cfs∗26) isoforms (6.6% vs. 16.1% and 13.8%, respectively) (Table S7). This suggests that ZIC3_SP1 (p.V409Mfs∗4) may act as a partial loss of function in vivo, as it maintained 7.65% nuclear localization and did not have a significant reduction in luciferase activity compared to ZIC3 WT (Figures 6H and 7B, respectively). The results for all functional assays using N-terminal HA-tagged ZIC3 plasmids are summarized in Table S8.

Splicing blocking vivo-MO partially rescues ZIC3 expression in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells

To determine whether normal ZIC3 protein levels could be rescued in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells, a ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G splice-blocking vivo-MO was employed, which directly targets the cryptic 3′ acceptor spite (Figure 9A). Untreated ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells showed reduced levels of normal ZIC3 protein (∼4.7%) relative to ZIC3 WT cells (Figures 9B and 9C). When exposing ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells to splice-blocking vivo-MO for 24 h, an increase in ZIC3 expression occurred (∼16.8% relative to ZIC3 WT cells). This partial rescue was further enhanced by increasing the exposure time to 48 h (∼23.9% relative to ZIC3 WT cells). No rescue was observed when ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells were exposed to a scramble vivo-MO control.

Figure 9.

ZIC3 is partially rescued in ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells by splicing blocking vivo-morpholino (MO)

(A) Schematic diagram showing the splice-blocking (SB) vivo-MO sequence and mRNA-binding site overlapping the 3′ splice acceptor generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant. The mutated “g” is shown in bold red, while the “ag” cryptic splice acceptor caused by the variant is underlined.

(B) Immunoblotting image of ZIC3 (∼55 kDa) detected in cell lysates from ZIC3 WT and ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells. ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells received either no treatment (NT), SB vivo-MO, or a scramble (SCR) vivo-MO for 24 or 48 h. Based on sequence homology, the bands at ∼60–65 and ∼45 kDa might correspond to ZIC2 and ZIC4, respectively. GAPDH served as loading control.

(C) Relative levels of ZIC3 from ZIC3 AtoG_C1 cells that received NT (light gray), an SCR vivo-MO (dark gray), or an SB vivo-MO (black) for either 24 or 48 h. compared to ZIC3 from ZIC3 WT cells (white bar). Levels of ZIC3 were normalized to their respective GAPDH levels from n = 1 experiment.

Discussion

In a family of four affected males with X-linked heterotaxy, WGS identified a deep, intronic variant in ZIC3 (ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G). Based on the current American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines,54,55 the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant is pathogenic when assessed in the context of the experimental work performed herein: the family history of X-linked heterotaxy is highly specific for a disease with a single genetic etiology (PP4); the variant co-segregates with the disease in multiple affected individuals in a gene definitively known to cause disease (PP1_strong); it is absent from reference databases (PM2); multiple splicing prediction programs determined this variant would alter RNA splicing (PP3); and numerous in vitro and in vivo functional studies found this variant results in severe dysregulation of RNA splicing in the ZIC3 gene causing multiple isoforms with abnormal function (PS3).

The fact that ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant triggers several abnormal splicing events was striking. Apart from the 3′ splice acceptor directly generated by the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant, the other inactive splice sites utilized by the additional exons found in the ZIC3 AtoG cells are present in the reference genome and were detected in both short- and long-read RNA-seq. Although these two sequencing modalities detected identical splice junctions, there were two noticeable differences. First, the short-read RNA-seq data displayed an evident increase in the number of reads aligning to the intronic region after P1(57) and before exon 4, allowing the detection of additional abnormal splicing patterns. This increment could be the result of an increased number of the total reads in the dataset. Second, the long-read RNA-seq showed a reduction in reads aligning to exon 1, which may reflect an inadequate reverse transcription during library preparation. This 3′ end coverage bias, which has been previously documented in Oxford Nanopore sequencing data,52 resulted in the inability to fully quantify the relative abundance of all abnormal ZIC3 transcripts produced by the variant. In addition, due to the innate splicing complexity, qRT-PCR was not feasible to determine the expression levels of the abnormal splicing patterns (ZIC3_SP1 – ZIC3_SP4) relative to the dominant ZIC3 isoform 1.

Further review of the RNA-splicing prediction analysis suggests the ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant not only creates a 3′ splice acceptor but also results in a net gain of auxiliary splicing sequences by altering the ratio of exonic splicing enhancer and exonic splicing silencer motifs, which could explain why these normally present yet inactive splice sites are utilized in the ZIC3 AtoG cell lines.

It is possible that the splicing pattern observed in H1-OCT4-eGP cells may not completely replicate what happens in the affected subjects. Unfortunately, patient tissue was unavailable for abnormal splicing patterns assessment, and ZIC3 is not highly expressed in clinically accessible tissues such as blood and skin. Furthermore, it is possible ZIC3’s splicing pattern may vary in adult vs. early embryonic tissues, where it is known to regulate laterality. Therefore, splicing assessment utilizing hESCs may provide more relevant results when compared to adult tissue.

While 74 DE genes were detected in undifferentiated ZIC3 KO_C1 cells, a separate study comparing ZIC3 KO and control hESCs differentiated to mesoderm cells identified over 1,000 DE genes, several of which play a known role in LR patterning and heart development.56 The use of a pluripotent stem cell population may account for the limited number of DE genes between the ZIC3 genotypes. It is possible a small number of DE genes identified may be key regulators responsible for the differentiation of pluripotent stem cells into downstream lineages.

Despite the limited gene list, MED10 and PLEKHA4 were significantly DE. MED10 was the most significantly upregulated gene in both mutant cell lines. MED10 is a component of the transcriptional mediator complex, a multi-subunit protein that relays signals from transcription factors to RNA polymerase II to regulate gene expression. Hypomorphic med10 zebrafish present with cardiac cushion defects resulting in pericardial edema, blood pooling, and death.57,58 Using MOs targeting med10 in zebrafish caused enhancement of WNT signaling and inhibition of NODAL signaling. Therefore, Med10 suppresses WNT signaling and activates NODAL signaling, important developmental signaling pathways previously shown to interact with ZIC3.10

In contrast, PLEKHA4 was downregulated in both cell lines. It localizes to the plasma membrane where it sequesters an E3 ubiquitin ligase targeting DVL, decreasing DVL ubiquitination and increasing canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling. The opposite effect is achieved by knocking down PLEKHA4, where canonical and non-canonical WNT signaling are decreased.59 Whether LR patterning defects seen in patients with ZIC3 loss-of-function variants and Zic3 null mice is in part due to alterations in MED10 and PLEKHA4 expression levels is currently unknown.

The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant severely disrupts the protein levels of ZIC3 isoform 1 as revealed by western blot analysis in H1-OCT4-eGFP cells. To further assess the functional impact of the deep intronic variant, in vitro and in vivo functional assays were performed with ZIC3_SP1 – ZIC3_SP4 (Table S8 for summary of results). The coding sequence of the four unique ZIC3 isoforms used in these functional studies assumes the canonical start codon within exon 1 is utilized. Accordingly, the coding sequences within the plasmids maintained the normal reading frame up until the inclusion of the additional exons present in ZIC3 AtoG cells. It is possible these abnormal splicing patterns may utilize a different start codon or an alternative reading frame, or they may not be stable in vivo. Whether that was the case, the various functional domains of ZIC3 would be even further disrupted than what was assessed herein. The studies assessing the functionality of the four ZIC3 isoforms tested them individually; however, RNA-seq analysis suggests these abnormal splicing patterns occur simultaneously. Therefore, it is possible the abnormal isoforms may interact with each other or with the normal ZIC3 isoforms, which was not directly evaluated.

Previous estimates found that 75% of X-linked familial and ∼1%–5% of sporadic heterotaxy cases are caused by variants in ZIC3.12,13 However, these estimates were based on targeted sequencing of the coding regions of ZIC3 in a patient cohort. Furthermore, all previously reported ZIC3 variants associated with a variety of diseases, including isolated CHDs, heterotaxy, situs inversus, VACTERL association, and X-linked oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum disorder, have been identified via assessment for large structural changes (i.e., fluorescence in situ hybridization, microarray), targeted sequencing of coding regions, which can include nearby flanking intronic sequences, or exome sequencing.5,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 Consequently, the majority of known ZIC3 variants associated with disease are located within the coding regions. A non-coding ZIC3 variant has been previously identified in a male fetus with heterotaxy (NM_003413.4:c.1060+1G>A), which was highly predicted to cause the loss of a canonical splice donor immediately after exon 1.24 The variant identified in the current study is also a non-coding variant in ZIC3 that causes pseudoexon inclusion and is associated with heterotaxy. There is a prior study of pseudoexon inclusion also associated with a laterality phenotype. This patient presented with primary ciliary dyskinesia and situs inversus totalis and harbored two variants in CCDC39: a nonsense variant (NM_181426.2:c.2357_2359delinsT; NP_852091.1:p.S786Ifs∗33) and a deep intronic variant (NM_181426.2:c.1167+1261A>G), causing the inclusion of a pseudoexon between exons 9 and 10.60

This study highlights the importance of assessing both coding and non-coding regions to identify potential disease-causing variants. A recent review article suggests the genetic cause of ∼55% of CHDs remains unknown after assessing patients for aneuploidies, copy-number variants, indels, and damaging coding variants.61 Findings from the current study encourage the assessment for non-coding regions in their unsolved CHD cases and consider additional mechanisms of disease, such as variants resulting in irregular RNA splicing, abnormal post-transcriptional modification, or disrupting gene-regulatory networks. This study also highlights the significant complexity of alternative splicing. Experimental analysis of non-coding variants predicted to alter splicing is essential to further understand impact and mechanisms. Additional studies that allow improvements in prediction of pseudoexons and cryptic splice donors and acceptors are important for analysis of the non-coding genetic architecture and variant interpretation in human disease.

Data and code availability

The ZIC3 c.1224+3286A>G variant was submitted to ClinVar under accession SCV005038948. Raw and processed RNA-seq files used in this study are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE263414.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank George Eckert, Biostatistician Supervisor at the Department of Biostatistics at the IUSM, for his assistance with statistical analyses. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Helen Bellchambers and Dr. Justin Couetil for their help with the luciferase assays and image randomization for the nuclear localization studies, respectively. The current work was supported by NHLBI grant P01 HL134599 (S.M.W., PI project 1).

Author contributions