Abstract

Background/Aims

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) play a crucial role in managing laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), but the optimal dosing regimen remains unclear. We aim to compare the effectiveness of the same total PPI dose administered twice daily versus once daily in LPR patients.

Methods

We conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial at a tertiary referral hospital, enrolling a total of 132 patients aged 19 to 79 with LPR. These patients were randomly assigned to receive either a 10 mg twice daily (BID) or a 20 mg once daily (QD) dose of ilaprazole for 12 weeks. The Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) and Reflux Finding Score (RFS) were assessed at 8 weeks and 16 weeks. The primary endpoint was the RSI response, defined as a reduction of 50% or more in the total RSI score from baseline. We also analyzed the efficacy of the dosing regimens and the impact of dosing and duration on treatment outcomes.

Results

The BID group did not display a higher response rate for RSI than the QD group. The changes in total RSI scores at the 8-week and 16-week visits showed no significant differences between the 2 groups. Total RFS alterations were also comparable between both groups. Each dosing regimen demonstrated significant decreases in RSI and RFS.

Conclusions

Both BID and QD PPI dosing regimens improved subjective symptom scores and objective laryngoscopic findings. There was no significant difference in RSI improvement between the 2 dosing regimens, indicating that either dosing regimen could be considered a viable treatment option.

Keywords: Ilaprazole, Laryngopharyngeal reflux, Proton pump inhibitors, Reflux Finding Score, Reflux Symptom Index

Introduction

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a widespread condition that affects a substantial number of people globally, causing significant discomfort and disruption to their daily lives.1,2 This condition is characterized by non-specific symptoms such as hoarseness, coughing, and dysphagia, which can make LPR difficult to diagnose and treat, as these symptoms can be caused by various underlying conditions.3,4 It is estimated that 40% of people in Western populations experience LPR symptoms, and the prevalence of this condition is likely to increase as a result of population aging and lifestyle factors, such as diet and stress.5

The precise pathogenesis of LPR remains incompletely understood; however, it is thought to result from exposure of the laryngopharynx to both acidic and non-acidic gastric contents.6,7 To treat LPR, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently prescribed. These agents function by reducing gastric acid production in the stomach, thereby alleviating symptoms and minimizing the risk of additional damage to the larynx and pharynx. PPIs are regarded as safe and effective, with a low incidence of adverse events.8,9

Although PPIs are recognized as a promising treatment for LPR, the optimal dosing regimen remains unclear. Numerous studies have investigated the efficacy of PPIs in reducing LPR symptoms, but few have directly compared different dosing regimens. Currently, twice-daily dosing is the recommended approach,3,7 and some studies support the use of a twice-daily regimen over a once-daily regimen.10-12 However, the evidence for the optimal dosing regimen of PPIs in LPR is limited, leading to uncertainty regarding the superiority of one regimen over another.

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of commonly used PPI dosing regimens in treating LPR. We conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial, hypothesizing that a 10-mg twice-daily PPI regimen would show greater efficacy in reducing LPR symptoms and findings than a 20-mg once-daily regimen. We also performed a subset analysis and compared treatment compliance and safety profiles.

Materials and Methods

This trial was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-1705-397-002) and was registered at Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in Korea (Trial registration: No. 31064, date of registration: 2018-03-07). The trial was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

This single-center, open-label, parallel-group, prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted at a tertiary referral hospital. Subjects were enrolled between September 2018 and December 2021. Patients aged 19 to 79 who were referred to the otorhinolaryngology outpatient clinic for chronic LPR symptoms were eligible for the study. All eligible subjects underwent otolaryngologic assessment of the head and neck with consequent laryngeal endoscopic examination. The inclusion criteria were as follows: presence of at least 1 symptom for more than 1 month, such as globus sensation, voice changes, hoarseness, persistent throat discomfort, sore throat, swallowing discomfort, and frequent throat clearing; endoscopic findings of the larynx consistent with LPR, as indicated by a Reflux Finding Score (RFS) over 713; no significant evidence of upper respiratory tract infection or allergies causing laryngitis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: individuals with hypersensitivity to PPIs, laryngeal malignancy, gastric ulcer, chronic liver or kidney disease, ciliary dyskinesia, cystic fibrosis, immune deficiency, uncontrolled thyroid disease, acute or chronic rhinosinusitis, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, or a history of alcoholism or drug abuse; those currently receiving atazanavir or rilpivirine; those who had taken decongestants or PPIs within the past 30 days; those using medications that interact with PPIs (such as theophylline, iron supplements, warfarin, anti-fungal drugs, and digitalis), NSAIDs, or steroids; those who had undergone abdominal surgery; and those who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

After subjects were confirmed for the eligibility, patients completed the Korean version of the Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) questionnaire, which evaluates the severity of 9 LPR symptoms.14 Each symptom is assigned a score from 0 to 5, with the total score ranging from 0 to 45 (Supplementary Fig. 1).15 Laryngeal endoscopy was performed for a RFS assessment (Supplementary Fig. 2).13 While patients were advised to undergo 24-hour dual pH probe testing and gastric endoscopy, these examinations were not included in the protocol due to the expected low compliance of the patients.

We assumed that the response rate for each trial group would be at least 50%, and calculated the minimum number of participants based on a one-sided significance level of 5%, and a test power of 80% to detect a difference in the RSI score response rate, utilizing the web-based sample size calculation formula provided by the University of British Columbia (https://www.stat.ubc.ca/~rollin/stats/ssize/). As a result, a minimum of 60 study participants were required for each group. We additionally assumed that 10% of the participants would be lost to follow-up or would discontinue the trial prematurely. This resulted in a final sample size for each group of 66, with the total number of participants to be 132.

The randomization sequence was generated using the RAND function in Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), and patients were allocated at a 1:1 ratio into 2 groups: twice-daily (BID) and once-daily (QD) with respect to the sample size. The BID group received a prescription for ilaprazole (10 mg) to be taken twice daily (before breakfast and at bedtime) for 12 weeks, while the QD group was prescribed ilaprazole (20 mg) to be taken once daily (before breakfast) for the same duration. Patients attended clinic visits for RSI and RFS evaluations at 8 and 16 weeks. While each participant was consulted by the practitioner during their visit, the prescription was conducted by a separate attending staff involved. As an open-label study, neither the subjects nor the attending physician was completely blinded to the study. However, the clinical research coordinator responsible for the survey was only informed of the patient’s name and group code, blinded to the group assignment. Furthermore, all personnel involved in RFS evaluation were blinded to the allocation.

The primary outcome was the response rate at 16 weeks, defined as a decrease in RSI score by more than 50% compared to the baseline RSI. Secondary outcomes included the RSI response rate at the 8-week visit, changes in RSI score and RFS at both 8- and 16-week visits, treatment compliance, and safety.

The RFS was evaluated by 2 independent otolaryngologist raters (J.Y.J. and G.H.). The inter-rater correlation coefficient was 0.755 (P < 0.001). The mean RFS of the 2 raters’ scores was used for statistical analysis.

Analyses were conducted using both the full analysis set (FAS) and the per-protocol set (PPS). The FAS included patients with both baseline and 8-week RSI scores. Missing data were addressed using the last observation carried forward method. The PPS consisted of patients with complete baseline, 8-week, and 16-week RSI and RFS data, and a compliance rate (the ratio of pills taken to pills prescribed) exceeding 70%.

The baseline characteristics were assessed using the Student’s t test and Pearson’s chi-square test. For the analysis of RSI response rates, the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was employed. Baseline RSI scores were categorized as either > 13 or ≤ 13, serving as a stratification factor. To evaluate changes in RSI and RFS, analysis of covariance was conducted. Mixed models for repeated measures (MMRM) were utilized to examine the effects of dosing and time on the RSI and RFS outcomes, adjusting for baseline RSI and RFS values. A subgroup analysis comparing changes in each RSI question was performed using the paired t test. R 4.1.1 and SPSS version 27.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) were used for the analyses. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for analyzing the RSI response rate was one-sided, while all other tests were two-sided.

Results

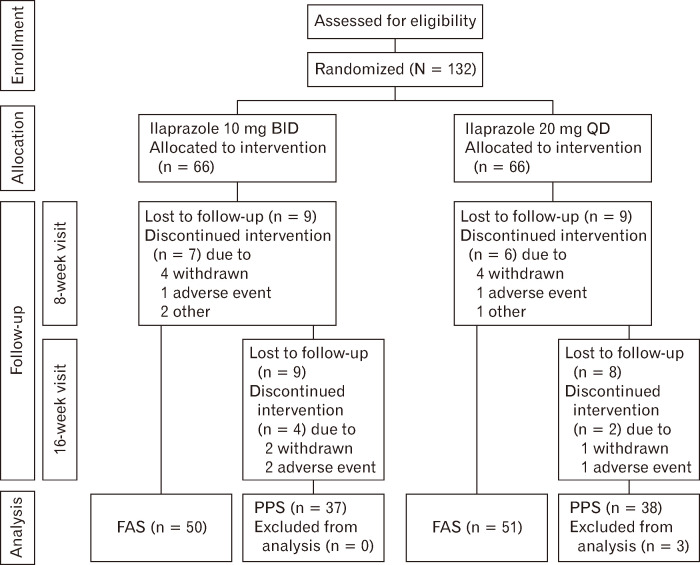

A total of 132 participants were enrolled in the study and were randomly assigned to receive either a 10-mg dose of ilaprazole BID (66 participants) or a 20-mg dose QD (66 participants) (Fig. 1). The 8-week and 16-week follow-up visits were attended by 101 (76.5%) and 78 (59.1%) patients, respectively. The mean compliance rates for those who were present at each visit were 95.2% at the 8-week follow-up and 98.7% at the 16-week follow-up. In total, 101 participants (BID group, n = 50; QD group, n = 51) were analyzed for the FAS. For the PPS analysis, 75 participants (BID group, n = 37; QD group, n = 38) were included.

Figure 1.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. BID, twice daily; QD, once daily; FAS, full analysis set; PPS, per-protocol set.

The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the FAS and PPS populations are displayed in Table 1. In the FAS group, the mean age (± SD) was 54.4 ± 12.2 years. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex distribution, body weight, height, alcohol consumption, or smoking status between the BID and QD groups within the FAS population. However, there were significant differences in baseline RSI and RFS between the BID and QD groups, with the QD group having a higher baseline RSI and the BID group having a higher baseline RFS.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics (According to Full analysis Set/Per-protocol Set Analysis)

| Variable | FAS | PPS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | BID group | QD group | P-value | Total | BID group | QD group | P-value | ||

| (n = 101) | (n = 50) | (n = 51) | (n = 76) | (n = 37) | (n = 38) | ||||

| Age (yr) | 54.4 ± 12.2 | 55.2 ± 11.8 | 53.6 ± 12.7 | 0.505 | 54.4 ± 12.2 | 54.3 ± 12.8 | 54.4 ± 11.7 | 0.973 | |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 54 (53.5) | 30 (60.0) | 24 (47.1) | 0.192 | 39 (52.0) | 23 (62.2) | 16 (42.1) | 0.082 | |

| Female | 47 (46.5) | 20 (40.0) | 27 (52.9) | 36 (48.0) | 14 (37.8) | 22 (57.9) | |||

| Body weight | 65.5 ± 11.4 | 65.3 ± 11.8 | 65.8 ± 11.1 | 0.812 | 65.4 ± 11.6 | 66.1 ± 12.7 | 64.8 ± 10.6 | 0.531 | |

| Height | 163.6 ± 8.9 | 163.1 ± 9.0 | 164.0 ± 8.8 | 0.604 | 163.7 ± 9.1 | 163.7 ± 9.5 | 163.7 ± 8.8 | 0.991 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.4 ± 3.2 | 24.5 ± 3.7 | 24.3 ± 2.7 | 0.818 | 24.4 ± 3.4 | 24.6 ± 4.1 | 24.1 ± 2.6 | 0.491 | |

| Alcohol | |||||||||

| Non drinker | 37 (37.0) | 20 (40.0) | 17 (34.0) | 0.626 | 27 (36.0) | 14 (37.8) | 13 (34.2) | 0.302 | |

| Former drinker | 24 (24.0) | 10 (20.0) | 14 (28.0) | 20 (26.7) | 7 (18.9) | 13 (34.2) | |||

| Current drinker | 39 (39.0) | 20 (40.0) | 19 (38.0) | 28 (37.3) | 16 (43.2) | 12 (31.6) | |||

| Smoking | |||||||||

| Never smoker | 63 (63.0) | 33 (66.0) | 30 (60.0) | 0.664 | 49 (65.3) | 25 (67.6) | 24 (63.2) | 0.694 | |

| Ex-smoker | 30 (30.0) | 13 (26.0) | 17 (34.0) | 23 (30.7) | 10 (27.0) | 13 (34.2) | |||

| Current smoker | 7 (7.0) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | 3 (4.0) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (2.6) | |||

| Baseline RSI | 17.5 ± 9.2 | 14.2 ± 8.4 | 20.8 ± 8.8 | < 0.001 | 17.7 ± 9.0 | 14.6 ± 9.0 | 20.7 ± 8.0 | 0.003 | |

| Baseline RFS | 10.5 ± 2.5 | 11.2 ± 2.4 | 9.8 ± 2.3 | 0.003 | 9.9 ± 3.4 | 11.2 ± 2.5 | 9.7 ± 2.4 | 0.009 | |

FAS, full analysis set; PPS, per-protocol set; BID, twice daily; QD, once daily; RSI, Reflux Symptom Index; RFS, Reflux Finding Score.

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Four adverse events were reported. Two adverse events occurred at the 8-week follow-up, and another 2 at the 16-week follow-up. The reported adverse events included abnormal liver function tests (n = 3) and diarrhea (n = 1).

The response rates for RSI at the 8- and 16-week follow-ups are shown in Table 2. In the FAS analysis, the response rate at the 16-week follow-up for the BID group was not significantly higher than that of the QD group (32.0% vs 37.3%, P = 0.541). Similarly, at the 8-week follow-up, the response rate for the BID group was not significantly higher than that of the QD group (26.0% vs 29.4%, P = 0.433). The PPS analysis also revealed the same trends.

Table 2.

Response Rate (Reflux Symptom Index) at 8-week and 16-week Follow-up

| FAS | BID group (n = 50) | QD group (n = 51) | COR (95% CI) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 16 weeks RSI responder | 16 (32.0) | 19 (37.3) | 1.05 (0.00-2.15) | 0.541 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| 8 weeks RSI responder | 13 (26.0) | 15 (29.4) | 0.92 (0.00-2.01) | 0.433 |

| PPS | BID group (n = 37) | QD group (n = 38) | COR (95% CI) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 16 weeks RSI responder | 13 (35.1) | 14 (36.8) | 0.83 (0.00-1.93) | 0.460 |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| 8 weeks RSI responder | 10 (27.0) | 11 (28.9) | 0.82 (0.00-2.02) | 0.465 |

aLeft tail test for one-sided alpha 0.05.

FAS, full analysis set; BID, twice daily; QD, once daily; COR, common odds ratio; RSI, Reflux Symptom Index; PPS, per-protocol set.

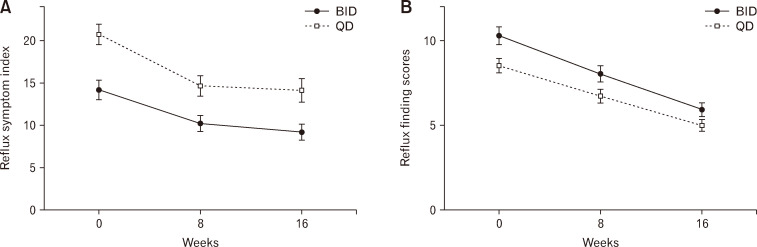

The changes in RSI and RFS according to each visit are presented in Table 3. Figure 2 illustrates the alterations in RSI and RFS within the FAS. The analysis of total RSI score changes at the 8-week and 16-week visits did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Similarly, the total RFS changes were comparable between both groups. The PPS analysis also demonstrated no significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Changes of Reflux Symptom Index and Reflux Symptom Index Scores (Analysis of Covariance)

| Secondary outcome (FAS) | BID group (n = 50) | QD group (n = 51) | AMD (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks change for total RSI score | –4.28 ± 1.05 | –3.96 ± 1.14 | 0.32 (–2.78-3.43) | 0.836 |

| 16 weeks change for total RSI score | –5.31 ± 1.02 | –4.47 ± 1.10 | 0.83 (–2.18-3.85) | 0.584 |

| 8 weeks total RSI score | 10.5 ± 1.07 | 12.9 ± 1.16 | 2.44 (–0.73-5.61) | 0.130 |

| 16 weeks total RSI score | 9.43 ± 1.16 | 12.37 ± 1.25 | 2.95 (–0.47-6.37) | 0.090 |

| 8 weeks change for total RFS score | –3.10 ± 0.26 | –3.39 ± 0.26 | 0.29 (–1.04-0.46) | 0.448 |

| 16 weeks change for total RFS score | –4.89 ± 0.25 | –5.24 ± 0.25 | –0.35 (–1.07-0.37) | 0.339 |

| 8 weeks total RFS score | 7.41 ± 0.26 | 7.12 ± 0.26 | –0.29 (–1.04-0.46) | 0.448 |

| 16 weeks total RFS score | 5.56 ± 0.25 | 5.21 ± 0.25 | –0.35 (–1.07-0.34) | 0.339 |

| Secondary outcome (PPS) | BID group (n = 37) | QD group (n = 38) | AMD (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks change for total RSI score | –4.16 ± 1.34 | –3.63 ± 1.48 | 0.523 (–3.43-4.48) | 0.793 |

| 16 weeks change for total RSI score | –5.53 ± 1.30 | –4.11 ± 1.43 | 1.42 (–2.41-5.25) | 0.463 |

| 8 weeks total RSI score | 10.2 ± 1.21 | 12.7 ± 1.34 | 2.48 (–1.10-6.05) | 0.172 |

| 16 weeks total RSI score | 8.85 ± 1.34 | 12.22 ± 1.48 | 3.37 (–0.60-7.34) | 0.095 |

| 8 weeks change for total RFS score | –3.99 ± 1.52 | –6.26 ± 1.54 | –2.27 (–6.69-2.15) | 0.957 |

| 16 weeks change for total RFS score | –5.07 ± 0.26 | –5.25 ± 0.27 | –0.19 (–0.95-0.57) | 0.623 |

| 8 weeks total RFS score | 6.93 ± 0.27 | 6.91 ± 0.27 | –0.02 (–0.80-0.76) | 0.957 |

| 16 weeks total RFS score | 5.41 ± 0.26 | 5.22 ± 0.27 | –0.19 (–0.95-0.57) | 0.623 |

FAS, full analysis set; BID, twice daily; QD, once daily; AMD, adjusted mean difference; RSI, Reflux Symptom Index; RFS, Reflux Finding Score; PPS, per-protocol set.

Data are presented as marginal mean ± SE.

Figure 2.

Full analysis set of changes in (A) the Reflux Symptom Index and (B) the Reflux Finding Score measured at 8 weeks and 16 weeks. BID, twice daily; QD, once daily.

MMRM analysis revealed significant decreases in RSI and RFS at the 8-week and 16-week visits compared to the baseline (Table 4). The estimated changes in RSI score were –5.04 at the 8-week visit and –6.21 at the 16-week visit, compared to the baseline. The baseline RSI score was found to have a meaningful impact on RSI outcomes; however, there was no significant difference between the BID and QD groups. The estimated changes in RFS at the 8-week and 16-week visits significantly decreased compared to the baseline. The dosing regimen had a considerable effect on RFS outcomes, with the BID group having a 1.17-point higher RFS than the QD group. The baseline RFS did not have a significant impact on RFS outcomes.

Table 4.

Result of Mixed Model for Repeated Measures Analysis

| RSI | Estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BID vs QD | –0.596 | –2.087 to 0.902 | 0.438 |

| 8-week vs baseline | –5.039 | –6.446 to –3.632 | < 0.001 |

| 16-week vs baseline | –6.213 | –7.746 to –4.684 | < 0.001 |

| RSI baseline | 0.710 | 0.626 to 0.795 | < 0.001 |

| RFS | Estimate | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BID vs QD | 1.167 | 0.423 to 1.910 | 0.003 |

| 8-week vs baseline | –3.032 | –3.397 to –2.662 | < 0.001 |

| 16-week vs baseline | –4.752 | –5.147 to –4.355 | < 0.001 |

| RFS baseline | 0.003 | –0.039 to 0.045 | 0.900 |

RSI, Reflux Symptom Index; BID, twice daily; QD, once daily; RFS, Reflux Finding Score.

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Supplementary Table shows the individual scores for each question on the RSI at baseline and the 16-week visit, as well as their differences. In both groups, questions 1, 4, 8, and 9 exhibited significant decreases at the 16-week visit compared to baseline. Questions 2, 3, 6, and 7 demonstrated significant decreases in the QD group, but not in the BID group. Conversely, question 5 showed a significant decrease in the BID group, but not in the QD group. Overall, the most substantial score reductions were observed in questions 1, 8, and 9, which pertain to hoarseness or voice problems, a sensation of something stuck in the throat or a lump in the throat, and heartburn, chest pain, indigestion, or stomach acid coming up, respectively.

Discussion

The primary objective of our study was to demonstrate the superior efficacy of the BID regimen compared to the QD regimen of PPIs in treating LPR. Although our findings did not confirm the superiority of the BID regimen over the QD regimen, they did reveal that both the 10-mg BID and 20-mg QD regimens were effective in alleviating LPR symptoms and improving laryngeal endoscopy results. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted in the efficacy, response rates, and adherence for the 2 regimens during the 8-week and 16-week follow-up periods.

Recent randomized controlled trials and guidelines highlight a growing consensus on the limitations of PPI therapy for LPR symptoms,16,17 Conversely, a recent meta-analysis suggests a mild superiority of PPI therapy over placebos,18 and another research advocates for an empirical trial of PPI therapy in patients with typical LPR symptom.19 Given the heterogeneity among various studies, the benefit of PPI therapy for LPR is still inconclusive. Our results, which demonstrate significant improvements in both RSI and RFS for the QD and BID groups, aligns with the findings above. However, with a response rate of less than 40%, it is difficult to draw a definitive conclusion about the benefits of PPI therapy. Nonetheless, it is worth recognizing that PPI therapy is the dominant primary treatment approach for patients with LPR worldwide.20 Our research aims to provide beneficial insights under this circumstance.

Numerous studies have examined the effectiveness of PPIs in alleviating LPR symptoms, but few have directly compared different dosing regimens of PPIs for LPR treatment. Our study aimed to further investigate this topic by comparing the efficacy of a 10-mg twice-daily regimen of PPIs versus a 20-mg once-daily regimen. Given that ilaprazole demonstrates an elimination half-life of 8.1 to 10.1 hours,21 the additional dosing of BID regimen was administered before bedtime to control nocturnal acid breakthrough, which may significantly influence LPR symptoms. This decision was further reinforced by previous studies that demonstrates the efficacy of additional bedtime dosing of PPI in managing nighttime gastric pH and reducing nocturnal acid breakthrough.22-24 Some studies comparing different dosing regimens found no significant differences between once-daily and twice-daily regimens. For instance, one study comparing dosing regimens of rabeprazole (20 mg once daily versus 10 mg twice daily) found no difference in the reduction of symptoms such as heartburn or regurgitation,25 Another study discovered no significant difference between once-daily and twice-daily regimens of esomeprazole.26 However, other studies reported conflicting results, arguing that the twice-daily regimen was more effective than the once-daily regimen of PPIs. Pharmacological evidence supports the idea that taking PPIs 30 minutes to 60 minutes before breakfast can lead to a 66% steady-state inhibition of maximal acid output with once-daily dosing, based on the assumption that 70% of pumps are activated by breakfast. In contrast, twice-daily dosing can increase this inhibition to 80%, with no additional effects observed at higher doses.27,28 In a prospective study comparing once-daily versus twice-daily PPIs in LPR, the results indicated that twice-daily dosing led to more significant symptom improvement than once-daily dosing.12 Furthermore, a recent systematic review recommends that patients with LPR should undergo twice-daily PPI dosing for 3 to 6 months, as this regimen is expected to significantly improve reflux symptoms.29

The variability in results across previous studies could be attributed to differences in study design, sample size, treatment duration, and patient characteristics. It is worth noting that the dosing regimen used in our study was twice the recommended dose by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service in South Korea, based on prior evidence suggesting the superiority of a twice-daily regimen over a once-daily regimen for treating gastroesophageal reflux disease. However, our study specifically focused on patients with LPR, which has distinct symptom patterns and underlying mechanisms compared to gastroesophageal reflux disease, making it crucial to investigate the optimal dosing regimen for this population. Furthermore, our study was designed to provide the same total daily dosage for both groups, potentially increasing the study’s power to detect differences between the 2 dosing regimens.

The major findings of our study suggest that there is no significant difference in the effectiveness of a 10-mg twice-daily regimen compared to a 20-mg once-daily regimen of PPI in alleviating LPR symptoms and findings. The primary outcome measure of our study was the RSI response rate at 16 weeks. We found no significant difference in the response rate between the 2 dosing regimens in both the FAS and PPS analyses. Additionally, the changes in RSI and RFS were not significantly different between the 2 groups. However, both dosing regimens resulted in significant reductions in RSI and RFS at the 8- and 16-week visits when compared to baseline.

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice, particularly for clinicians managing patients with LPR. This discovery is pertinent for patients who struggle with adhering to a twice-daily regimen, as it necessitates more frequent medication administration and may be associated with increased costs and prolonged treatment duration. While the participants in our study demonstrated similar compliance rates, several other studies have suggested that dosing frequency can influence treatment adherence in various diseases, with the once-daily regimen showing higher compliance rates.30-33 Offering a once-daily dosing regimen may enhance treatment adherence and decrease both treatment duration and costs.

Another meaningful finding from our study, as shown in Supplementary Table, is that various dosing regimens of PPIs can influence different symptoms of LPR. This information may assist clinicians in tailoring treatment for individual patients, taking these differences into consideration when choosing a dosing regimen. However, it is important to note that our findings were derived from a subgroup analysis, so they should be interpreted cautiously and considered in the context of the study’s limitations.

It is also important to note that both dosing regimens were safe and well-tolerated, with a low incidence of adverse events. Only 4 adverse events were reported, including abnormal liver function tests and diarrhea, with no significant difference in the occurrence rate between the 2 dosing regimens. This finding suggests that both once-daily and twice-daily dosing of PPI can be considered safe and effective therapeutic options for LPR. Our study’s results provide clinicians with greater flexibility in prescribing PPIs for LPR treatment. Additionally, the availability of different dosing options may enable personalized treatment based on patient preference and lifestyle.

Our study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. First, we utilized only 1 PPI, ilaprazole, which may render the findings inapplicable to other PPIs. Second, the study was carried out at a single center, potentially restricting the generalizability of our results to different populations. Third, the investigation was confined to a 16-week duration, leaving the long-term effects of different PPI dosing regimens unexplored. Furthermore, the majority of our patients were referred by primary care physicians due to chronic or refractory reflux symptoms. Although these participants underwent a 30-day washout period from previous remedies, this history might have influenced the low response rate. Additionally, the low response rate may be due to the lack of strict control over dietary and lifestyle habits, which are known factors for treatment resistance. Despite these constraints, our study could contribute to the establishment of optimal dosing guidelines for PPIs in the treatment of LPR.

In conclusion, both the BID and QD PPI dosing regimens proved to be equally effective in treating LPR, as they improved subjective symptoms and laryngoscopic findings while maintaining high compliance rates and low adverse events. Consequently, either dosing regimen can be regarded as a viable treatment option.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Division of Statistics in Medical Research Collaborating Center at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for statistical analysis.

Supplementary Materials

Note: To access the supplementary table and figures mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm23118.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by IL-YANG Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. This study as an investigator-initiated trial, and IL-Yang Pharmaceutical was not involved in the trial design, data collection or analysis, or manuscript preparation or review.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Conceptualization and methodology: Jeong-Yeon Ji, Gene Huh, Woo-Jin Jeong, and Young Ho Jung; formal analysis and investigation: Jeong-Yeon Ji, Gene Huh, Eunjeong Ji, Jin Yi Lee, and Seung Heon Kang; writing––original draft preparation: Jeong-Yeon Ji, and Gene Huh; writing––review and editing: Jeong-Yeon Ji, Gene Huh, Wonjae Cha, and Woo-Jin Jeong; and supervision: Woo-Jin Jeong and Young Ho Jung.

References

- 1.Mendelsohn AH. The effects of reflux on the elderly: the problems with medications and interventions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51:779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lechien JR, Akst LM, Hamdan AL, et al. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease: state of the art review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:762–782. doi: 10.1177/0194599819827488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koufman JA, Aviv JE, Casiano RR, Shaw GY. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: position statement of the committee on speech, voice, and swallowing disorders of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:32–35. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.125760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai YC, Wang PC, Lin JC. Laryngopharyngeal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4523–4528. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirti YK. Reflux finding score (RFS) a quantitative guide for diagnosis and treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;70:362–365. doi: 10.1007/s12070-018-1350-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamal AN, Dhar SI, Bock JM, et al. Best practices in treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease: a multidisciplinary modified delphi study. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:1125–1138. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07672-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford CN. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. 2005;294:1534–1540. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.12.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brisebois S, Merati A, Giliberto JP. Proton pump inhibitors: review of reported risks and controversies. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3:457–462. doi: 10.1002/lio2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reimer C, Bytzer P. Management of laryngopharyngeal reflux with proton pump inhibitors. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:225–233. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S6862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Yang Z, Ni Z, Shi Y. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the efficacy of twice daily PPIs versus once daily for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:9865963. doi: 10.1155/2017/9865963.d48916f53dea4d3aa57cf073824c0189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita Y, Hongo M Japan TWICE Study Group, author. Efficacy of twice-daily rabeprazole for reflux esophagitis patients refractory to standard once-daily administration of PPI: the Japan-based TWICE study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:522–530. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park W, Hicks DM, Khandwala F, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: prospective cohort study evaluating optimal dose of proton-pump inhibitor therapy and pretherapy predictors of response. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000163746.81766.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. The validity and reliability of the reflux finding score (RFS) Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1313–1317. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung YH, Chang DY, Jang JH, et al. Reflux symptom index (RSI) and reflux finding score (RFS) of persons taking health checkup and their relationship with gastrofiberscopic findings. Korean Journal of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI) J Voice. 2002;16:274–277. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Hara J, Stocken DD, Watson GC, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;372:m4903. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:27–56. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechien JR, Saussez S, Schindler A, et al. Clinical outcomes of laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:1174–1187. doi: 10.1002/lary.27591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaezi MF, Katzka D, Zerbib F. Extraesophageal symptoms and diseases attributed to GERD: where is the pendulum swinging now? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1018–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lechien JR, Allen JE, Barillari MR, et al. Management of laryngopharyngeal reflux around the world: an international study. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E1589–E1597. doi: 10.1002/lary.29270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bortoli N, Martinucci I, Giacchino M, et al. The pharmacokinetics of ilaprazole for gastro-esophageal reflux treatment. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:1361–1369. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.813018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karyampudi A, Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Verma A, Misra A, Saraswat VA. Esophageal acidification during nocturnal acid-breakthrough with ilaprazole versus omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:208–217. doi: 10.5056/jnm16087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz PO, Koch FK, Ballard ED, et al. Comparison of the effects of immediate-release omeprazole oral suspension, delayed-release lansoprazole capsules and delayed-release esomeprazole capsules on nocturnal gastric acidity after bedtime dosing in patients with night-time GERD symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ours TM, Fackler WK, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. Nocturnal acid breakthrough: clinical significance and correlation with esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:545–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delchier JC, Cohen G, Humphries TJ. Rabeprazole, 20 mg once daily or 10 mg twice daily, is equivalent to omeprazole, 20 mg once daily, in the healing of erosive gastrooesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1245–1250. doi: 10.1080/003655200453566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlando RC, Liu S, Illueca M. Relationship between esomeprazole dose and timing to heartburn resolution in selected patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010:117–125. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin JM, Sachs G. Pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2008;10:528–534. doi: 10.1007/s11894-008-0098-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe MM, Sachs G. Acid suppression: optimizing therapy for gastroduodenal ulcer healing, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and stress-related erosive syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(2 suppl 1):S9–S31. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spantideas N, Drosou E, Bougea A, AlAbdulwahed R. Proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux. A systematic review. J Voice. 2020;34:918–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296–1310. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smits E, Andreotti F, Houben E, et al. Adherence and persistence with once-daily vs twice-daily direct oral anticoagulants among patients with atrial fibrillation: real-world analyses from the Netherlands, Italy and Germany. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022;9:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s40801-021-00289-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McHorney CA, Peterson ED, Ashton V, et al. Modeling the impact of real-world adherence to once-daily (QD) versus twice-daily (BID) non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants on stroke and major bleeding events among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:653–660. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1530205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Challagulla S, Kebede N, Rege S, Volodarsky RR, Osei-Bonsu K, Karve S. Impact of dosing frequency of oral oncolytics on refill adherence among patients with hematological malignancies. Blood. 2021;138:1964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-145070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.