Abstract

Ischemia-induced brain damage leads to apoptosis like delayed neuronal death in selectively vulnerable regions, which could further result in irreversible damages. Previous studies have demonstrated that neurons in the CA1 area of hippocampus are particularly sensitive to ischemic damage. Atorvastatin (ATV) has been reported to attenuate cognitive deficits after stroke, but precise mechanism for neuroprotection remains unknown. Therefore, the aims of this study were to investigate the neuroprotective mechanisms of ATV against ischemic brain injury induced by cerebral ischemia reperfusion. In this study, four-vessel occlusion model was established in rats with cerebral ischemia. Rats were divided into five groups: sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, I/R+ATV+LY, and I/R+SP600125 group. Cresyl violet staining was carried out to examine the neuronal death of hippocampal CA1 region. Immunoblotting was used to detect the expression of the related proteins. Results showed that ATV significantly protected hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons against cerebral I/R. ATV could increase the phosphorylation of protein kinase B (Akt1) and nNOS, diminished the phosphorylation of JNK3 and c-Jun, and further inhibited the activation of caspase-3. Whereas, all of the aforementioned effects of ATV were reversed by LY294002 (an inhibitor of Akt1). Furthermore, pretreatment with SP600125 (an inhibitor of JNK) diminished the phosphorylation of JNK3 and c-Jun, and further inhibited the activation of caspase-3 after cerebral I/R. Taken together, our results implied that Akt-mediated phosphorylation of nNOS is involved in the neuroprotection of ATV against ischemic brain injury via suppressing JNK3 signaling pathway that provide a new experimental foundation for stroke therapy.

Keywords: Cerebral ischemia, Akt1, nNOS, JNK3, LY294002

Introduction

Ischemic brain injury is a common and severe pathology with high rates of morbidity, disability, and mortality (Qi et al. 2014; Lehotsky et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2016). Extensive studies have been performed to explore effective strategies and drugs to ameliorate or prevent ischemic injury (Kim et al. 2009; Moran et al. 2016). Statins, the inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-glutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, are not only the principle agents applied to lower serum cholesterol, but also have a wide range of positive effects on ischemic diseases (Song et al. 2014; Meng et al. 2016). Owing to differences in the efficacy and side effects of different statin drugs, some of the drugs have gradually been clinically eliminated (Song et al. 2014; Kong et al. 2016). As a second-generation HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, ATV is currently used in the treatment of ischemic cerebrovascular diseases. However, the mechanism of ATV’s effect is still not completely elucidated.

Ischemic stroke involves in the regulation of multiple survival and death-signaling pathway which lead to several pathophysiological changes (Qi et al. 2012). The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, a major cell survival pathway, serves a key role in mediating anti-apoptotic actions, which is closely correlated with ischemic brain injury (Marz-Weiss et al. 2011; Qu et al. 2015). Akt is a 57 kDa protein serine/threonine kinase and has three family members, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3. Previous studies have shown that Akt1 is widely expressed in the brain and its phosphorylation at Ser473 plays an important role in neuronal protection thus has treatment effects on ischemic disease of the central nervous system (Downward 1998). Furthermore, several targets of Akt1 have been identified to play important roles in the regulation of apoptosis, such as the proapoptotic proteins Bcl-2/Bcl-XL-associated death protein (BAD), caspase-9, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase-3 (JNK3) (Wang et al. 2007; Pilchova et al. 2015).

Nitric oxide (NO), as a reactive free radical gas, is generated by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) and plays a vital role in regulating many physiological and pathophysiological processes (Lipton et al. 1993). NOS has three known isoforms in mammals: neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NOS (iNOS) (Yan et al. 2004). It has been demonstrated that only nNOS is primarily expressed in neurons, and nNOS plays a critical role in neurotoxicity after ischemia (Bredt et al. 1991). In mutant mice deficient in nNOS and subsequent NO production, infarct size becomes smaller and neuronal injury is less than those in normal mice after brain ischemia (Huang et al. 1994). Therefore, nNOS represents one of the most important signaling molecules for adaptive brain plasticity after stroke. It was recently shown that Akt could regulate nNOS activity through phosphorylation (Rameau et al. 2007). Therefore, Akt-mediated phosphorylation of nNOS could be an impartment approach to neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia.

JNKs, members of MAPK family, are extremely important in the process of neuronal death (Meloni et al. 2014). JNKs are encoded by three genes: JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3. JNK1 and JNK2 are expressed in most tissues, while JNK3 is selectively expressed in the brain, heart, and testicles (Junyent et al. 2011; Zhang and Li 2012). Previous studies show that neuronal apoptosis induced by brain ischemia partly depends on the phosphorylation of JNK3 and activated JNK, in turn, phosphorylates c-Jun, which further activates those proteins associated with apoptosis such as Bcl-2 and caspase-3 (Wang et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2013).

On the basis of above considerations, it is not clear whether the neuroprotective mechanisms of ATV against cerebral ischemia are related to the Akt-mediated phosphorylation of nNOS signaling pathway. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the relations between neuroprotection of ATV and the Akt-nNOS signaling pathway in the rat brain after stroke. In addition, LY294002 (an inhibitor of Akt1) and SP600125 (an inhibitor of JNK) were used to determine whether Akt-nNOS signaling pathway was necessary to inhibit the phosphorylation of JNK3 and its downstream c-Jun, which is associated with the death effector caspase-3 during I/R in the rat hippocampus.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies were selected: Anti-p-Akt1 (ser473; ab66138) were obtained from Abcam Biotechnology. Anti-cleaved caspase-3 (no. 9664) was obtained from Cell Signaling Biotechnology. Anti-p-JNKs (sc-6254), anti-p–c-jun (sc-16312), and anti-actin (sc-10731) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The secondary antibody, LY294002 used in our experiment was obtained from Sigma. JNK inhibitor (SP600125) used in our experiment was obtained from Abcam.

Animals and Ischemic Model

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g (Shanghai Experimental Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai, China) were given free access to food and water before surgery. All rats were divided into the following groups: sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, I/R+ATV+LY, and I/R+SP600125 group. Each group was composed of 18 rats. Sham controls were performed using the same surgical procedures, with the exception that the occlusion of the carotid arteries was not performed. The surgical procedures were approved by the Shanghai Experimental Animal Center. The surgical procedures were conducted under the guidelines and terms of all relevant local legislations. Our best efforts were made to minimize the number of rats used and the suffering that they experienced. Transient cerebral ischemia (15 min) was induced by four-vessel occlusion (4-VO) as described before (Xu et al. 2010). Briefly, after being anesthetized with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg, i.p.), both of the vertebral arteries were occluded permanently by electrocautery, and the common carotid arteries were exposed. Then, the rats recovered for 24 h and fasted overnight. To induce cerebral ischemia, aneurysm clips were used to occlude both of the carotid arteries. After 15 min of occlusion, the aneurysm clips were removed for reperfusion. In this process, four rats died; therefore, 118 rats were sacrificed in total.

Atorvastatin Administration

ATV (Pfizer Company, USA) that dissolved in 0.9 % normal saline was administered intragastrically once a day at the dose of 5 mg/(kg day) from 2 h after I/R to the day the rats were sacrificed (Tu et al. 2014).

Open-Field Test and Closed-Field Test

Open-field test and closed-field test were used to evaluate the locomotive activity. Each rat was placed in the center of an open-field apparatus or a closed-field apparatus (W50 Χ D50 Χ H30 cm) and acclimated for 3 min. Afterward, their free-moving behavior was monitored for 5 min. Their behavior was analyzed using the ANY-maze video tracking system (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) with a CCD camera; the total distance traveled and the crossing lines were analyzed.

Elevated Plus Maze Test

Elevated plus maze test was performed as described before (Menard and Treit 1998). After treatments, the rat was placed in the center of the elevated plus maze with its head facing an open arm and left undisturbed for 5 min. The total time spent in the open arms [OAT % (the ratio of times spent in the open arms to total times spent in any arms × 100)] was used as a measure of anxiety. The number of body stretching which introduced as criteria for anxiety was determined. Significant changes in OAT % and stretching were indicated as the anxiety phenomenon in this test.

Tissue Preparation

After reperfusion under anesthesia, the rats were decapitated immediately; then, the hippocampi were removed and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. The hippocampi were homogenized in 1:10 (w/v) ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 50 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS; Sigma, St. Louis, MO; pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 320 mM sucrose, 50 mM NaF, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4 (Sigma), 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 20 mM β-phosphoglycerol, 1 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP), 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 5 μg/mL each of leupeptin, aprotinin, and pepstatin A. Then, they were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants, including nuclear parts, were collected, and the protein concentrations were determined by the Lowry method. The samples were stored at −80 °C and were thawed only once.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were separated on polyacrylamide gels and then electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The membranes were blocked for 3 h in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1 % Tween 20 (TBST) and 3 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in TBST containing 1 % BSA. The membranes were then washed and incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies in TBST for 2 h and developed with NBT/BCIP color substrate (Promega, Madison, WI). The densities of the bands on the membrane were scanned and analyzed using an image analyzer (LabWorks Software, Upland, CA).

Histology

In the 4-VO ischemic model, rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and underwent transcardial perfusion with 0.9 % saline, followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. Brains were removed, postfixed overnight in paraformaldehyde, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Coronal brain sections (6 μm thick) were cut on a microtome. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a gradient of ethanol and distilled water. The sections were stained with cresyl violet and examined with a light microscope, and the neuronal density of the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells was expressed as the number of cells per 1 mm length counted under a light microscope (3400). Neuronal survival was quantitatively analyzed by counting the number of the surviving neurons within 0.02 mm2.

Statistical Evaluation

Nine rats were independently selected as samples in all groups for immunoblotting and histology assays. Image J (Version 1.30 v) analysis software was used to conduct quantitative analysis of the bands. Values were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis of the results was carried out by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls test. P-values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The Effects of ATV on I/R-Induced Behavior Impairment

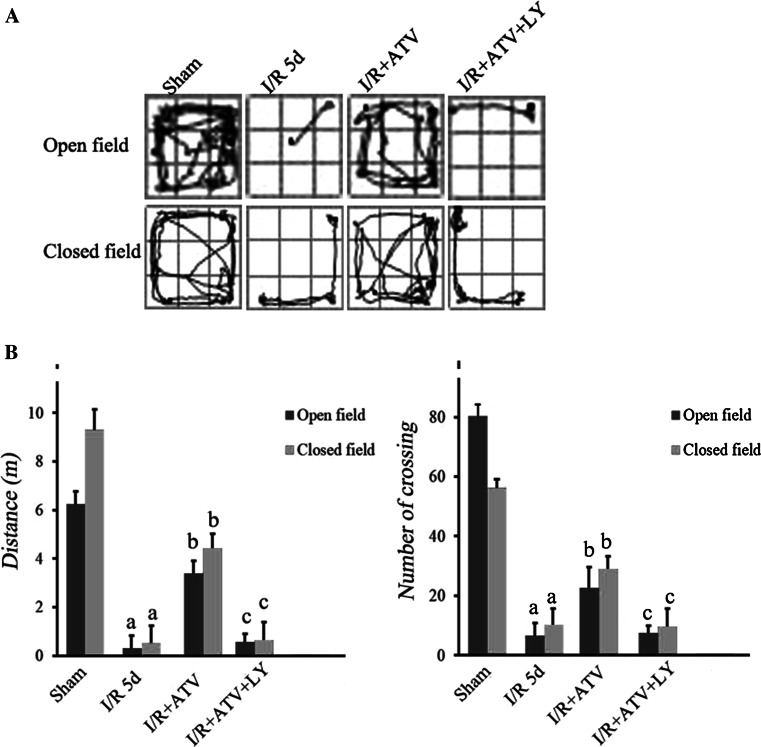

Ischemic stroke results from a temporary or permanent reduction of cerebral blood flow that leads to behavior impairment. In order to explore the effect of ATV on cerebral I/R-induced behavioral impairment, open-field test and elevated plus maze test were used (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Performance of rats in the open-field test and closed-field test. a The track maps of different groups. b Total distance traveled during 5 min and crossing lines during 5 min. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (a) P < 0.05 relative to sham group. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 12 for each group

Fig. 2.

Performance of rats in elevated plus maze test. a OAT % of each group was measured. b Stretching of each group was measured. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (a) P < 0.05 relative to sham group. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 12 for each group

In order to evaluate locomotor activity and exploratory behavior of ATV-treated rats, open-field test was used (Fig. 1a). The results indicated that compared with the sham group, I/R rats had decreased traveling distance and the crossing frequency (Fig. 1b), suggesting the impairment of motor and exploration activities in I/R rats (Fig. 1). After ATV treatment, the traveling distance and the crossing frequency were significantly increased, which were reversed by LY294002 treatments (Fig. 1a, b).

Furthermore, in order to investigate anxiety-like behavior of ATV-treated rats, elevated plus maze test experiments were further used (Fig. 2). The results indicated that compared with the sham group, I/R rats had decreased the percentage of OAT and number of stretching (Fig. 2a, b). After ATV treatment, the percentage of OAT and number of stretching were also significantly increased (Fig. 2a, b). However, pretreatment with LY294002 reversed the anxiolytic effect of ATV in ischemic group in all measured parameters.

The Neuroprotective Effects of ATV Against I/R-Induced Neuronal Loss

To determine whether ATV has a neuroprotective effect against I/R-induced neuronal injury, cresyl violet staining was performed to investigate the effect of ATV on the survival of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the rat hippocampus (Fig. 3a, b), where neurons were particularly vulnerable to ischemic injury, at 5 days of reperfusion. Normal cells presented with round and pale-stained nuclei, while the normal morphological structure disappeared in the dead cells. As shown in Fig. 1a, b, surviving cells in the sham group showed round and pale-stained, nuclei in the hippocampus, whereas the I/R group showed severe cell death (P < 0.05; Fig. 3a, b). I/R rats receiving ATV treatment showed a significant decrease in neuronal degeneration in the hippocampus compared to the I/R group, whereas LY294002 reversed these results (P < 0.05; Fig. 3a, b). The results suggest that ATV can increase nerve cellular survival in the hippocampus in experimental I/R rats through Akt pathway.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ATV and LY294002 on the survival of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Rats were divided to sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, and I/R+ATV+LY group. a Cresyl violet staining was performed on sections from the hippocampi of rats. Representative hippocampal photomicrographs of cresyl violet staining. b The numbers of staining-positive neurons were quantitatively analyzed. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (a) P < 0.05 relative to sham group. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 9 for each group

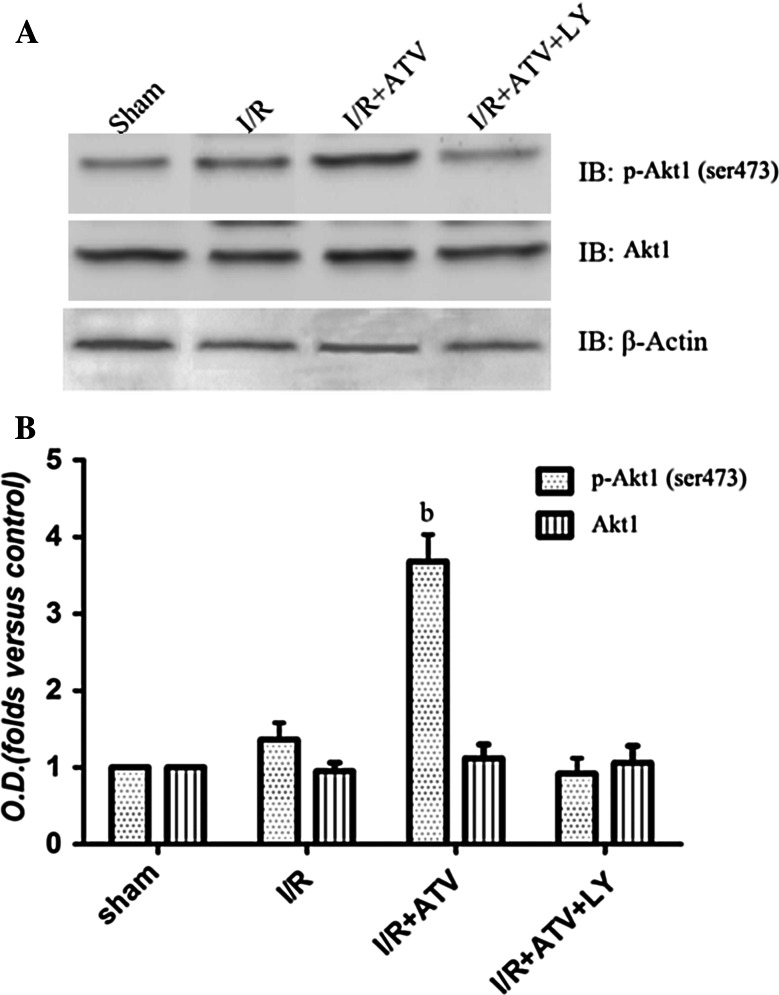

Effects of ATV on the Phosphorylation of Akt1 (Ser473) during cerebral I/R in the brain of rats

The above results indicated that the neuroprotective effects of ATV might be related to Akt signaling pathway. To explore the possible role of Akt1 pathway mediated by ATV, Akt1 (ser473) phosphorylation was detected 6 h after I/R (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4, in the hippocampus, ATV treatment strengthened Akt1 (ser473) phosphorylation at 6 h of reperfusion, while LY294002 blocked the elevation of ATV-induced Akt1 activation (P < 0.05; Fig. 4, b). These data conclusively suggested that ATV could increase the phosphorylation of Akt1 (ser473) during the process of cerebral I/R.

Fig. 4.

Effects of ATV and LY294002 on the phosphorylation of Akt1 (ser473). Rats were divided to sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, and I/R+ATV+LY group. The phosphorylation of Akt1 (ser473) in hippocampus by immunoblot analysis at 6 h after I/R. a Immunoblot bands were scanned. b The intensity of the bands was expressed as optical density (O.D.) analysis. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. N = 9 for each group

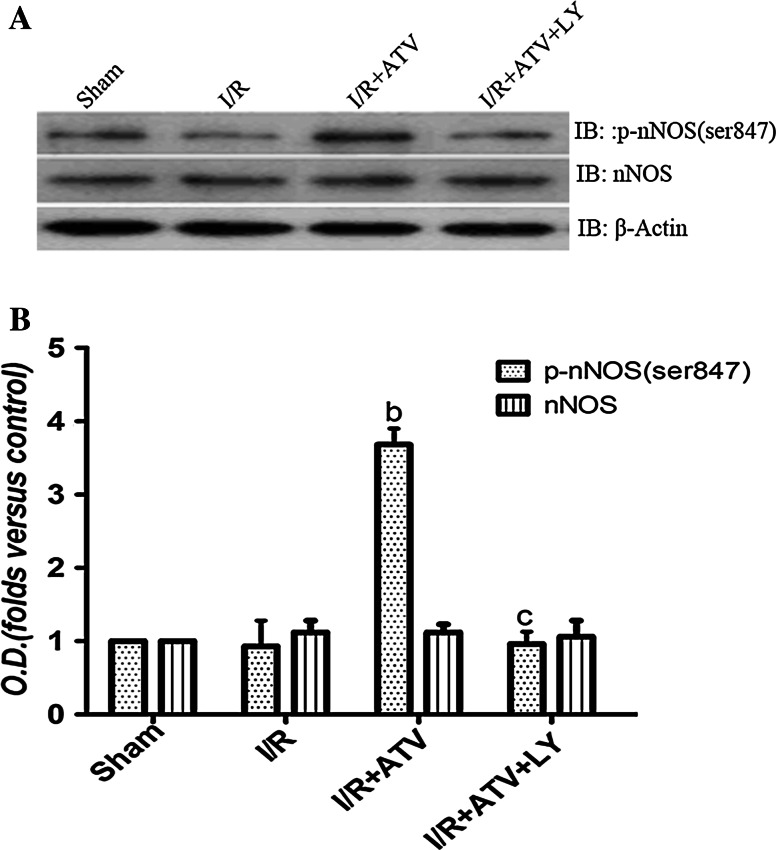

Effects of ATV on the Phosphorylation of nNOS (Ser847) During Cerebral I/R in the Brain of Rats

It has been established that nNOS could be phosphorylated by Akt. To demonstrate whether nNOS Ser847 phosphorylation was affected via ATV-induced phosphorylation of Akt1 (Ser473) during cerebral I/R, we analyzed the variation of Ser847 phosphorylation of nNOS. As shown in Fig. 5, the phosphorylation of nNos (Ser847) was decreased to control level at 6 h of reperfusion, but increased significantly in ATV group, however, pretreatment with ATV-combined LY294002 prevented the increased phosphorylation of nNOS (Ser847) induced by ATV. These results suggested that ATV could up-regulate nNOS Ser847 phosphorylation via Akt pathway.

Fig. 5.

Effects of ATV and LY294002 on the phosphorylation of nNOS (ser847). Rats were divided to sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, and I/R+ATV+LY group. The phosphorylation of nNOS (ser847) in hippocampus by immunoblot analysis at 6 h after I/R. a Immunoblot bands were scanned. b The intensity of the bands was expressed as optical density (O.D.) analysis. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 9 for each group

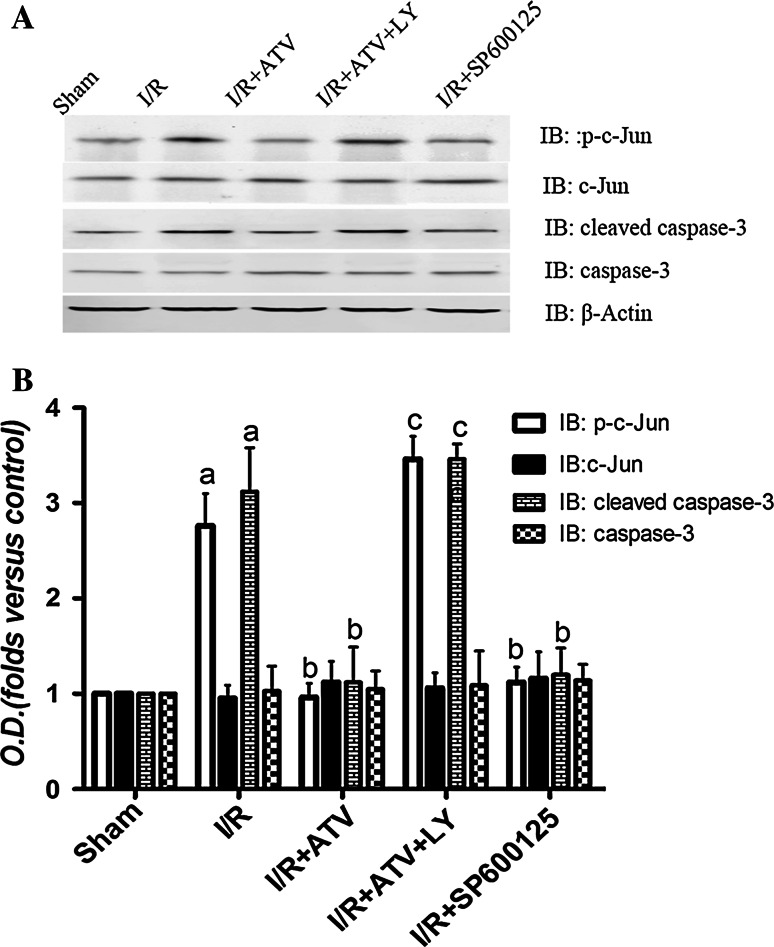

Effects of ATV on the Activation of JNK3 and c-Jun

Previous researches indicate that the activation of JNK3 accounts for delayed neuronal death at 3 days of reperfusion following 15 min of ischemia in hippocampal CA1 regions (Pan et al. 2005). We examined the effect of ATV on JNK3 at 6 h after I/R in each group. As shown in Fig. 6, ATV and SP600125 reduced the phosphorylation of JNK3 induced by I/R, whereas LY294002 removed the above effect of ATV (P < 0.05). Moreover, studies demonstrate that c-Jun is a nuclear substrate of JNK3, which is activated after reperfusion and reaches its activation peak at 6 h of reperfusion. Thereby, it is essential to address the effect of ATV on the phosphorylation of c-Jun. We found that ATV and SP600125 prevented the increased c-Jun phosphorylation at 6 h of reperfusion. On the contrary, LY294002 significantly reversed this effect (P < 0.05; Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 6.

Effects of ATV, SP600125, and LY294002 on the phosphorylation of JNK3 in I/R rats. Rats were divided to sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, I/R+ATV+LY group, and I/R+SP600125 group. a, c Immunoblot bands were scanned. b, d The intensity of the bands was expressed as optical density (O.D.) analysis. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (a) P < 0.05 relative to sham group. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 9 for each group

Effects of ATV on the Expression of Apoptosis Related Protein: Caspase-3

Apoptosis after cerebral ischemia is one of the major pathways that lead to the process of cell death. Therefore, we examined cleaved caspase-3 levels by WB. It has been shown that caspase-3 has only one activated peak at 6 h of reperfusion in our previous studies (Pan et al. 2005). So here, we examined the expression changes of caspase-3 at 6 h after I/R in each group (P < 0.05; Fig. 7a, b). The data showed that treatment with ATV and SP600125 significantly decreased the protein expression of cleaved caspase-3, while treatment with ATV+LY blocked the effect of ATV on the caspase-3 (P < 0.05; Fig. 7a–d).

Fig. 7.

Effects of ATV, SP600125, and LY294002 on the phosphorylation of c-Jun and the protein expression of cleaved caspase-3 in I/R rats. Rats were divided to sham group, I/R group, I/R+ATV group, I/R+ATV+LY group, and I/R+SP600125 group. a, b Immunoblot bands were scanned. b, d The intensity of the bands was expressed as optical density (O.D.) analysis. Data were presented as mean ± SD. (a) P < 0.05 relative to sham group. (b) P < 0.05 relative to I/R. (c) P < 0.05 relative to I/R+ATV group. N = 9 for each group

Discussion

A local or global reduction in cerebral blood can lead to an extensive range of neurological impairments, including motor disabilities, autonomic dysfunction, epilepsy, memory, and attention disorders (Carty et al. 2011; Viggiano et al. 2014; Ciftci et al. 2014; Lalkovicova et al. 2015). Clinical evidences support that the death of CA1 pyramidal neurons is a major characteristic of I/R injury, which is a common cause of neurological deficits and cognitive impairment in survivors of birth (Qi et al. 2014). In this study, we showed that ATV remarkably improved CA1 pyramidal neuron survival in the context of I/R-induced brain injury through Akt1-nNos-JNK3 signaling pathway.

ATV has multiple biological directional functions (Amarenco et al. 2006). The neuroprotection effects of ATV have been paid increasing attention, in particular. Hong et al. (2006) found that pretreatment with ATV could protect the ischemic penumbra of neuron cells and reduce the infarct volume in I/R injury rats (Hong et al. 2006). Moreover, Song et al. (2014) found that the neuroprotective effects of ATV was related to cell apoptosis inhibition (Song et al. 2014). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of ATV were not completely understood. What is the upstream messenger transducing signal after ATV-mediated cell apoptosis inhibition? Substantial evidence indicated that Akt was a crucial mediator of neuronal survival to disable components of the apoptotic machinery by phosphorylating itself, which plays an important role in brain ischemia (Datta et al. 1997). Therefore, to examine whether Akt1 is involved in the neuroprotective effect of ATV, LY294002, an Akt inhibitor, was performed. Our results show that ATV treatment significantly increased the level of phosphorylation of Akt1 (ser473), and the level changes can be reversed by LY294002.

It has been reported that an excess of NO associates with the development of cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s psychosis nervous system diseases, whereas, nNOS activity could be regulated by Akt (Watanabe et al. 2003). Therefore, there may be a functional interaction between Akt and nNOS underling the discrepancy in ATV-induced neuroprotection. In addition, it is well established that phosphorylation of NOS at Ser847 reduces its activity to approximately 70 % of unphosphorylated enzyme (Hayashi et al. 1999). Hence, we further investigated the effects of ATV on the phosphorylation of nNOS in the present studies. The results showed that ATV increased the phosphorylation of nNOS. Moreover, we have currently shown that pretreatment of LY294002 blocked the above results induced by ATV, which suggested that ATV increases phosphorylation of nNOS by activating Akt1.

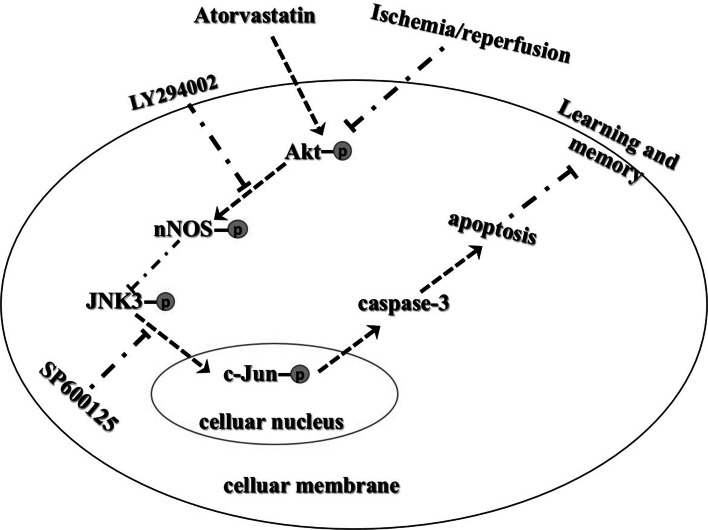

The intrinsic mitochondrion-dependent pathway, the extrinsic death receptor pathway, and the intrinsic endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway are three different death-signaling pathways leading to apoptosis (Majewski et al. 2004; Sharifi et al. 2010). Among these three different death-signaling pathways, mitochondrion-dependent pathway-mediated apoptosis represents the dominant cause of programed cell death, which is well known to be involved in I/R-induced cellular damage. Furthermore, neuronal apoptosis induced by brain ischemia partly depends on the phosphorylation of JNK3 and activated JNK, in turn, phosphorylates c-Jun, which further activates those proteins associated with apoptosis (Wang et al. 2007). Therefore, we investigated that ATV inhibits CA1 pyramidal neurons apoptosis through inhibiting JNK3/c-Jun/Caspase-3 by enhancing Akt1 signaling pathway. The present results showed that I/R dramatically increased p-JNK3, p–c-Jun, and cleaved caspase-3 expression levels. ATV significantly decreased p-JNK3, p–c-Jun, and cleaved caspase-3 expression activations. These results suggest that ATV can inhibit JNK3-c-Jun-caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. However, these results were reversed in the presence of the Akt1 antagonist LY294002. Thereby, we confirmed that preconditioning with ATV could remarkably inhibit the activation of JNK3/c-Jun/caspase-3 pathway during reperfusion after lethal ischemia through ATV-mediated activation of Akt signaling pathway (Fig. 8). These results might provide some clues to understand the mechanism underlying ischemia and to find clinical therapies for stroke using ATV neuroprotection.

Fig. 8.

I/R could suppress Akt1 activation and activates JNK3/c-Jun/caspase-3 signaling pathway and then lead to neuronal apoptosis. If Akt1 activation was induced, activated Akt1 could negatively regulate JNK3 and finally block neuronal apoptosis. Pretreatment with ATV improves neuronal survival through inhibiting JNK3 signaling pathway by inducing Akt1-nNOS signaling pathway

In summary, this work demonstrated, for the first time, that ATV could protect neurons against brain ischemia followed by reperfusion through inhibiting JNK3/c-Jun/caspase-3 by enhancing Akt-nNOS signaling pathway (Fig. 8). We investigated the neural protective effect of ATV and sheds light on the underlying signaling mechanism. However, the exact mechanism of the activation of Akt1 mediated by ATV needs further explorement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Brain Disease Bioinformation (JSBL1505), Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Anesthesiology (KJS1502), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271296).

Author Contributions

S.S. designed the study. M.X., J.Z., X.G., G.C., L.G., L.L., and K.L. performed the experiments and collected the data. S.S. and Z.Z. analyzed and interpreted the experimental data. S.S., M.X., and J.Z. prepared the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Sen Shao, Phone: +86 571 86481561, Email: hzsxxyy2015@sohu.com.

Fayong Zhang, Phone: +86 571 86481561, Email: hsfayongzhang@163.com.

References

- Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, Goldstein LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE, Sillesen H, Simunovic L, Szarek M, Welch KM, Zivin JA, SPARCL (2006) High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 355(6):549–559. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredt DS, Hwang PM, Glatt CE, Lowenstein C, Reed RR, Snyder SH (1991) Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P-450 reductase. Nature 351(6329):714–718. doi:10.1038/351714a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty ML, Wixey JA, Reinebrant HE, Gobe G, Colditz PB, Buller KM (2011) Ibuprofen inhibits neuroinflammation and attenuates white matter damage following hypoxia-ischemia in the immature rodent brain. Brain Res 1402:9–19. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciftci O, Oztanir MN, Cetin A (2014) Neuroprotective effects of beta-myrcene following global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-mediated oxidative and neuronal damage in a C57BL/J6 mouse. Neurochem Res 39(9):1717–1723. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1365-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME (1997) Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell 91(2):231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J (1998) Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr Opin Cell Biol 10(2):262–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Nishio M, Naito Y, Yokokura H, Nimura Y, Hidaka H, Watanabe Y (1999) Regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calmodulin kinases. J Biol Chem 274(29):20597–20602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H, Zeng JS, Kreulen DL, Kaufman DI, Chen AF (2006) Atorvastatin protects against cerebral infarction via inhibition of NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291(5):H2210–H2215. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.01270.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Huang PL, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA (1994) Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science 265(5180):1883–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junyent F, de Lemos L, Verdaguer E, Folch J, Ferrer I, Ortuno-Sahagun D, Beas-Zarate C, Romero R, Pallas M, Auladell C, Camins A (2011) Gene expression profile in JNK3 null mice: a novel specific activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. J Neurochem 117(2):244–252. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07195.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kim S, Jung WY, Park SJ, Park DH, Kim JM, Cheong JH, Ryu JH (2009) The neuroprotective effects of the seeds of Cassia obtusifolia on transient cerebral global ischemia in mice. Food Chem Toxicol 47(7):1473–1479. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, Zhu J, Liu Q, Jiang Y, Xu L, Luo N, Zhao Z, Zhai Q, Zhang H, Zhu M, Liu X (2016) Mesenchymal stem cells protect neurons against hypoxic-ischemic injury via inhibiting parthanatos, necroptosis, and apoptosis, but not autophagy. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s10571-016-0370-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalkovicova M, Bonova P, Burda J, Danielisova V (2015) Effect of bradykinin postconditioning on ischemic and toxic brain damage. Neurochem Res 40(8):1728–1738. doi:10.1007/s11064-015-1675-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehotsky J, Petras M, Kovalska M, Tothova B, Drgova A, Kaplan P (2015) Mechanisms involved in the ischemic tolerance in brain: effect of the homocysteine. Cell Mol Neurobiol 35(1):7–15. doi:10.1007/s10571-014-0112-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA, Choi YB, Pan ZH, Lei SZ, Chen HS, Sucher NJ, Loscalzo J, Singel DJ, Stamler JS (1993) A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature 364(6438):626–632. doi:10.1038/364626a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Zhao J, Chang Z, Guo G (2013) CaMKII activates ASK1 to induce apoptosis of spinal astrocytes under oxygen-glucose deprivation. Cell Mol Neurobiol 33(4):543–549. doi:10.1007/s10571-013-9920-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski N, Nogueira V, Robey RB, Hay N (2004) Akt inhibits apoptosis downstream of BID cleavage via a glucose-dependent mechanism involving mitochondrial hexokinases. Mol Cell Biol 24(2):730–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz-Weiss P, Kunz D, Bimmler D, Berkemeier C, Ozbek S, Dimitriades-Schmutz B, Haybaeck J, Otten U, Graf R (2011) Expression of pancreatitis-associated protein after traumatic brain injury: a mechanism potentially contributing to neuroprotection in human brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 31(8):1141–1149. doi:10.1007/s10571-011-9715-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloni BP, Craig AJ, Milech N, Hopkins RM, Watt PM, Knuckey NW (2014) The neuroprotective efficacy of cell-penetrating peptides TAT, penetratin, Arg-9, and Pep-1 in glutamic acid, kainic acid, and in vitro ischemia injury models using primary cortical neuronal cultures. Cell Mol Neurobiol 34(2):173–181. doi:10.1007/s10571-013-9999-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard J, Treit D (1998) The septum and the hippocampus differentially mediate anxiolytic effects of R(+)-8-OH-DPAT. Behav Pharmacol 9(2):93–101 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Tan J, Li M, Song S, Miao Y, Zhang Q (2016) Sirt1: role under the condition of ischemia/hypoxia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s10571-016-0355-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran J, Perez-Basterrechea M, Garrido P, Diaz E, Alonso A, Otero J, Colado E, Gonzalez C (2016) Effects of estrogen and phytoestrogen treatment on an in vitro model of recurrent stroke on HT22 neuronal cell line. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s10571-016-0372-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Zhang QG, Zhang GY (2005) The neuroprotective effects of K252a through inhibiting MLK3/MKK7/JNK3 signaling pathway on ischemic brain injury in rat hippocampal CA1 region. Neuroscience 131(1):147–159. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilchova I, Klacanova K, Chomova M, Tatarkova Z, Dobrota D, Racay P (2015) Possible contribution of proteins of Bcl-2 family in neuronal death following transient global brain ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol 35(1):23–31. doi:10.1007/s10571-014-0104-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D, Liu H, Niu J, Fan X, Wen X, Du Y, Mou J, Pei D, Liu Z, Zong Z, Wei X, Song Y (2012) Heat shock protein 72 inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 signaling pathway via Akt1 during cerebral ischemia. J Neurol Sci 317(1–2):123–129. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2012.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D, Ouyang C, Wang Y, Zhang S, Ma X, Song Y, Yu H, Tang J, Fu W, Sheng L, Yang L, Wang M, Zhang W, Miao L, Li T, Huang X, Dong H (2014) HO-1 attenuates hippocampal neurons injury via the activation of BDNF-TrkB-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in stroke. Brain Res 1577:69–76. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2014.06.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu YY, Yuan MY, Liu Y, Xiao XJ, Zhu YL (2015) The protective effect of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury is associated with PI3K/Akt pathway and ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Neurochem Res 40(1):1–14. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1456-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rameau GA, Tukey DS, Garcin-Hosfield ED, Titcombe RF, Misra C, Khatri L, Getzoff ED, Ziff EB (2007) Biphasic coupling of neuronal nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation to the NMDA receptor regulates AMPA receptor trafficking and neuronal cell death. J Neurosci 27(13):3445–3455. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4799-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi AM, Mousavi SH, Jorjani M (2010) Effect of chronic lead exposure on pro-apoptotic Bax and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein expression in rat hippocampus in vivo. Cell Mol Neurobiol 30(5):769–774. doi:10.1007/s10571-010-9504-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T, Liu J, Tao X, Deng JG (2014) Protection effect of atorvastatin in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury rats by blocking the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Genet Mol Res 13(4):10632–10642. doi:10.4238/2014.December.18.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Q, Cao H, Zhong W, Ding B, Tang X (2014) Atorvastatin protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Neural Regen Res 9(3):268–275. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.128220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viggiano E, Viggiano D, Viggiano A, De Luca B, Monda M (2014) Cortical spreading depression increases the phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the cerebral cortex. Neurochem Res 39(12):2431–2439. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1447-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XT, Pei DS, Xu J, Guan QH, Sun YF, Liu XM, Zhang GY (2007) Opposing effects of Bad phosphorylation at two distinct sites by Akt1 and JNK1/2 on ischemic brain injury. Cell Signal 19(9):1844–1856. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Song T, Sugimoto K, Horii M, Araki N, Tokumitsu H, Tezuka T, Yamamoto T, Tokuda M (2003) Post-synaptic density-95 promotes calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-mediated Ser847 phosphorylation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Biochem J 372(Pt 2):465–471. doi:10.1042/BJ20030380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Liu ZA, Pei DS, Xu TJ (2010) Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II facilitated GluR6 subunit serine phosphorylation through GluR6-PSD95-CaMKII signaling module assembly in cerebral ischemia injury. Brain Res 1366:197–203. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan XB, Meng FJ, Song B, Zhang GY (2004) Brain ischemia induces serine phosphorylation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in rat hippocampus. Acta Pharmacol Sin 25(5):617–622 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZB, Li ZG (2012) Cathepsin B and phospo-JNK in relation to ongoing apoptosis after transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neurochem Res 37(5):948–957. doi:10.1007/s11064-011-0687-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LL, Zhang HT, Cai YQ, Han YJ, Yao F, Yuan ZH, Wu BY (2016) Anti-inflammatory effect of mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation and quercetin treatment in a rat model of experimental cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s10571-015-0291-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]