Abstract

Oxidative stress plays an important role in the pathogenesis of early brain injury (EBI) following subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The aim of this study was to assess whether cysteamine prevents post-SAH oxidative stress injury via its antioxidative and anti-apoptotic effects. It was observed that intraperitoneal administration of cysteamine (20 mg/kg/day) could significantly alleviate EBI (including neurobehavioral deficits, brain edema, blood–brain barrier permeability, and cortical neuron apoptosis) after SAH in rats. Meanwhile, cysteamine treatment reduced post-SAH elevated the reactive oxygen species level, the concentration of malondialdehyde, 3-nitrotyrosine, and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and increased the glutathione peroxidase enzymatic activity, the concentration of glutathione and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in brain cortex at 48 h after SAH. These results indicated that administration of cysteamine may ameliorate EBI and provide neuroprotection after SAH in rat models.

Keywords: Subarachnoid hemorrhage, Cysteamine, Early brain injury

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is a disastrous stroke subtype with significant morbidity and mortality, and often results in lasting neurological deficits for survivors (van Gijn et al. 2007). Previous studies have indicated that early brain injury (EBI), which refers to the acute injuries to the whole brain within the first 72 h after SAH, including increased intracranial pressure, decreased cerebral perfusion pressure, disturbed microcirculation, brain edema formation, oxidative stress, and delayed cerebral vasospasm and damage to the microvascular system (Barry et al. 2012; Sehba et al. 2012). In particular, consequences of oxidative stress after SAH include damage of vascular smooth muscle and endothelium, disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), production of vasoconstrictors, and induction of pro-apoptotic enzymes (Barry et al. 2012; Sehba et al. 2012). Hence, antioxidants have been used to prevent oxidative stress and decrease brain injury in the experimental SAH model, but have met with little success in improving outcome in human clinical trials (Gomis et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2010).

Cysteamine (β-mercaptoethylamine) is a potential and safe antioxidant compound, in which cysteamine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cystinosis, and is being evaluated for Huntington’s disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Besouw et al. 2013). Cysteamine is a degradation product of coenzyme A and a reduced form of cystamine can enter the brain via crossing the BBB (Pinto et al. 2009). In animal models, cysteamine exhibits antioxidative effect (Kessler et al. 2008a, , b) and exhibits neuroprotective effects in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease (Sun et al. 2010b; Pillai et al. 2008). Cysteamine can inhibit the activity of pro-apoptotic caspase-3 and elevate brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) level (Borrell-Pages et al. 2006; Shieh et al. 2008), and improve spatial memory deficits and BDNF signaling (Kutiyanawalla et al. 2011). Therefore, cysteamine is hypothesized to have neuroprotective role against EBI after SAH.

The present study was designed to explore the effects of cysteamine in preventing oxidative stress and cortical apoptosis in a rat SAH model.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Taishan Medical University. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (weight, 280–350 g; Experimental Animal Center of Shandong University) were used in this study. The rats were housed in cage at a constant temperature (24 ± 1 °C) and humidity (60 ± 5 %) with a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Experimental Protocol

The experimental groups consisted of sham-operated group (n = 24), vehicle-treated SAH group (n = 24), and cysteamine-treated SAH group (n = 24). In cysteamine-treated SAH group, dose (0.1 ml, 20 mg/kg/day) of cysteamine was administered after first blood injection. Rats of vehicle-treated SAH group received equal volumes (0.1 ml 0.9 % saline) at corresponding time points. Both cysteamine and vehicle were administered intraperitoneally. After the neurological assessment, all the rats were killed at 48 h after SAH. Six rats in each group were decollated. The brain sample was removed and rinsed in ice 0.9 % saline to wash way blood and blood clot. The tissue was then frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately for molecular biological and biochemical experiments. Six rats in each group were for detecting BBB impairment. Six rats in each group were for detecting brain water content. Six rats in each group were for immunohistological staining study.

Rat SAH Model

Experimental SAH was induced in rats using Suzuki′s double blood injection model with modification according to our previous study (Sun et al. 2010a; Zhang et al. 2014). Briefly, rats were anesthetized through intraperitoneal administration of chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg). The animal’s core body temperature was at least 37 °C with an electrical pad and a light bulb. The rat’s head was fixed in the stereotactic frame with the head angled down at approximate 30°. A skin incision was made in middle of the back of the neck. Under the surgical microscope, the underlying muscular attachments were separated to expose the atlanto-occipital membrane. The needle was lowered into cisterna magna under direct vision. Then the amount of 0.3 ml non-heparinized fresh autologous arterial whole blood was injected into the cistern for 10 min with a syringe pump. The second injection of blood was achieved after 1 day recovery. The sham-operated group underwent the same procedures except for the cisternal injection of fresh autogenous blood. The rats had free access to food and water after recovery from anesthesia.

Cysteamine Administration

Cysteamine (Sigma, USA) is available as a sterile concentrated solution in 0.9 % saline at 200 mg/ml.

After first blood injection, rats received cysteamine (0.1 ml, 20 mg/kg/day) or vehicle (0.1 ml, sterile saline) via intraperitoneal injection at 30 min and then once daily for 3 days. The dose of cysteamine (20 mg/kg) is equivalent to that used for the treatment of the patients (Dubinsky and Gray 2006), and exhibit antioxidative effect in cerebral cortex of rats (Kessler et al. 2008a, b).

Neurological Scoring

Three behavioral activity examinations of scoring system (Table 1) were performed at 48 h after SAH according to our previous study (Zhang et al. 2014). Scoring was performed to record appetite, activity, and neurological deficits by two ‘blinded’ investigator, while the sequence of testing for the given tasks was randomized. Neurological deficits of the experimental animals were graded as follows: (i) no neurologic deficit (score = 0); (ii) suspicious or minimum neurologic deficit (score = 1); (iii) mild neurologic deficit (score = 2–3); (iv), severe neurologic deficit (score = 4–6).

Table 1.

Behavior scores

| Category | Behavior | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Appetite | Finished meal | 0 |

| Left meal unfinished | 1 | |

| Scarcely ate | 2 | |

| Activity | Active, walking, barking, or standing | 0 |

| Lying down, walk and stand with some stimulations | 1 | |

| Almost always lying down | 2 | |

| Deficits | No deficits | 0 |

| Unstable walk | 1 | |

| Impossible to walk and stand | 2 |

Brain Water Content

Brain edema was determined according to the wet/dry method where % brain water content = [(wet weight − dry weight)/wet weight] × 100 %. Briefly, each brain sample was removed from the skull and weighed immediately. Then the sample of cerebral hemispheres was dried at 100 °C for 48 h and weighed to determine the dry weight.

Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability

BBB permeability was assessed by Evans blue (EB, Sigma, USA) dye extravasation at 48 h after SAH according to our previous study (Zhang et al. 2014). Briefly, rats were injected intravenously with 3 ml/kg of 2 % (w/v) EB dye. Rats were then re-anesthetized after 1 h with 1,000 mg/kg urethane and perfused with 0.9 % saline solution to remove remaining intravascular EB dye. Afterward, the brains were removed and homogenized in 3 ml phosphate buffered saline. 2 ml 50 % trichloroacetic acid was then added to precipitate protein for 2 min, and the brain samples were centrifuged. The absorbance of EB dye supernatants was measured at 610 nm using a SpectraMax M5e multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA).

Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Level in Brain Homogenate

ROS level of brain homogenate was performed according to our previous study (Zhang et al. 2014). Briefly, ROS level of brain homogenate was measured using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCDHF-DA,Sigma, USA). DCDHF-DA is a cell permeable and non-fluorescent. In presence of ROS, it oxidizes inside the cells and transformed into a fluorescent compound, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF, Exλ = 488 nm, Emλ = 520 nm), which remains trapped within the cell. For detecting the ROS in brain homogenate, homogenates were diluted 1:10 in ice-cold HEPES-Tyrode solution (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6) to obtain a concentration of 5 mg protein/ml. 0.45 ml homogenates and 5 μl of DCDHF-DA (10 μM final concentration) were added to 24-well plates at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, and then the DCF was measured using a SpectraMax M5e multi-mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA). ROS production was quantified from a DCF standard curve and values expressed as pmol DCF formed/mg protein/min.

Measurement of MDA and GSH Concentration, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) and Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) Activities in Brain Cortex

MDA and GSH concentration, LDH and GSH-Px enzyme activities of brain cortex were performed according to our previous study (Zhang et al. 2014). Briefly, the brain cortex was harvested at 48 h post-SAH under deep anesthesia and stored at −80 °C until use. The supernatant of all the samples was collected after homogenate. After determination of the protein concentration, the supernatant was used for detection.

MDA concentration was measured using a commercial MDA assay kit (Nanjing Institute of Jiancheng Biological Engineering, China). The principle of the assay kit depends on the reaction of lipid peroxidation with thiobarbituric acid formation of products named as thiobarbituric acid reacting substances (λ = 530 nm). MDA concentration was determined from a standard absorbance versus concentration curve, and given as nm/g wet tissue.

GSH concentration was measured using a GSH assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Institute of Jiancheng Biological Engineering, China). GSH concentration (μmol/g tissue protein) = (OD sample − OD blank)/(OD standard solution − OD blank standard solution) × standard solution concentration/tissue sample protein concentration.

LDH activity was measured using a LDH assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Institute of Jiancheng Biological Engineering, China). LDH activity (U/g tissue protein) = (OD sample − OD blank)/(OD standard solution − OD blank standard solution) × standard solution concentration/tissue sample protein concentration.

GSH-Px assay kit (Northwest Life Science Specialties, USA) was used for the determination of tissue GSH-Px activities. The principle of the assay is as follows: GSH-Px catalyzes the reduction of H2O2, oxidizing reduced GSH to form GSSG. GSSG is then reduced by GSH reductase and β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate forming NADP + (λ = 340 nm) and recycling the GSH. The rate of change in the optical density at 340 nm is directly proportional to the GSH-Px activity. One unit of GSH-Px equals to the amount of enzyme necessary to catalyze the oxidation (by H2O2) of 1.0 μmol GSH to GSSG per minute at 25 °C. GSH-Px activities of the tissue samples were given as U/mg tissue protein.

TUNEL and Immunohistological Staining

TUNEL and Immunohistological staining were performed according to our previous study (Zhang et al. 2014). Rats were anesthetized 48 h after SAH and perfused transcardially with 0.9 % saline followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and kept in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 6 h, then immersed in 30 % sucrose for 3 days at 4 °C. Brain Sections (18 μm) were rinsed three times in PBS, and blocked in 10 % goat serum/PBS/0.1 % Triton X-100 at room temperature for 2 h.

TUNEL staining was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit with Fluorescein (Roche Applied Science, Germany) following the manufacturer′s recommendations. For active caspase-3 and NeuN immunohistological staining, sections were incubated with anti-active caspase-3 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), and anti-NeuN (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) at 4 °C for 12 h. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:1,000, Life technologies, USA) for active caspase-3 and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:1,000, Life technologies, USA) for NeuN. After incubation, sections were cover slipped with anti-fading solution. Slides were viewed under a confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan) and images taken using constant parameters. Three microscope fields (20×) of TUNEL-positive cells or active caspase-3 positive cells in brain cortex were chosen and imaged. The number of TUNEL/DAPI positive cells and active caspase-3/NeuN double positive cells was calculated as the mean of the numbers obtained from the six pictures. Counting was performed in a blinded manner.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot was performed as previously described (Sun et al. 2010a). Briefly, rats were anesthetized, and the brains were then removed and stored at −80 °C until use. The frozen brain cortex was mechanically homogenized in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl (pH7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.25 % sodium deoxycholate, 0.25 % SDS, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM PMSF]. The lysates were sonicated and centrifuged. After determination of the protein concentration using BCA protein assay kit (Tiangen, China), equal amounts of protein were resolved on a 12 % (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS) gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Scientific, USA) by electrophoretic blotting. The membrane was blocked with 5 % skimmed milk, incubated with primary antibody against active cleaved caspase-3 antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology) or β-actin antibody (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Then the membrane was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibody (1:5,000, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), detected by supersignal west pico chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific, USA) and visualized using X-ray film.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The concentration of 3-NT, 8-OHDG, or BDNF was measured with commercial ELISA kit for rats according to the manufacturer’s instructions. (oxiselect TM Nitrotyrosine, oxidative DNA damage ELISA kit for 3-NT or 8-OHDG, Cell Biolabs, Inc, USA; Rat BDNF ELISA kit, BlueGene Biotech, China). Briefly, with 3-NT, 8-OHDG, or BDNF antibody-coated microtiter plate in ELISA, 3-NT, 8-OHDG, or BDNF of standards or samples combined with the antibody pre-coated wells. A standardized preparation of HRP-conjugated antibody was added to each well to bind the immobilized 3-NT, 8-OHDG, or BDNF on the plate. The HRP and substrate were allowed to react, terminated by addition of the substrate fluid acid, and measured OD value (λ = 450 nm). A standard curve is plotted relating the OD value to the concentration of standards. The concentration of each sample was obtained from this standard curve and represented (3-NT, nmol/g tissue protein; 8-OHDG, ng/g tissue protein; BDNF, pg/mg tissue protein).

Statistical Analysis

Data expressed as mean ± SEM were analyzed with GraphPad Software Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego) and comparisons were made by one-way ANOVA analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests. Value of P < 0.05 was indicated statistical significance.

Results

Behavior Observation and Physiological Variables

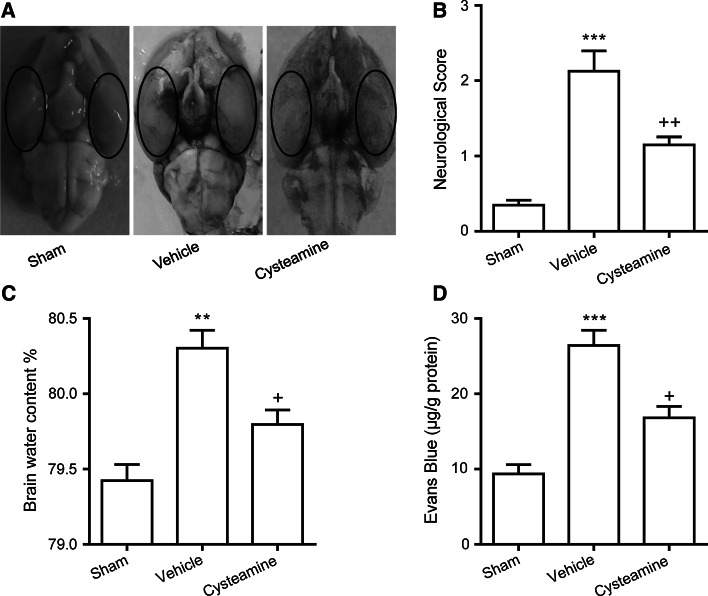

After SAH, extensive arterial hemolysate was found in subarachnoid spaces. The blood clots could be found on the basal surface of the brainstem and around the basilar arteries (Fig. 1a). The mortality rates were not significantly different between the vehicle-treated SAH group (20 % [6 of 30 rats]) and cysteamine-treated SAH group (17.2 % [5 of 29 rats]). No sham-operated rats died.

Fig. 1.

a Schematic representation of the cortex sample area taken for assay (oval). Representative rat brain of sham-operated group (left), vehicle-treated SAH group (middle), or cysteamine-treated SAH group (right). Effect of cysteamine administration on b neurological scores, c brain water content of cerebral cortex, d Evans blue (EB) content as indices for BBB permeability, in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. Values are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, each group). ***p < 0.001 or **p < 0.01 compared to sham-operated group; ++ p < 0.01 or + p < 0.05 compared to vehicle-treated SAH group

Improvements in Neurobehavioral Deficits After SAH with Cysteamine

The average neurobehavioral score recorded at 48 h post-surgery was significantly higher in the vehicle-treated SAH group than in the sham-operated group (2.1 ± 0.4 vs. 0.4 ± 0.1, P < 0.001, Fig. 1b). On the other hand, the average score revealed statistically significant improvement in the cysteamine-treated SAH group compared to the vehicle-treated SAH group (1.2 ± 0.2 vs. 2.1 ± 0.3, P < 0.01, Fig. 1b), but was still higher than that of the sham-operated group.

Attenuation of Brain Edema and BBB Permeability Following SAH by Cysteamine

Using the brain water content as an indicator of brain edema, the water content of the cerebral cortex was significantly increased in the vehicle-treated SAH group as compared with the sham-operated group at 48 h after SAH (80.30 ± 0.11 vs. 79.42 ± 0.10 %, P < 0.01, Fig. 1c). The mean value of brain water content in the brain tissue was decreased by cysteamine administration as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group (79.80 ± 0.09 vs. 80.30 ± 0.11 %, P < 0.05, Fig. 1c).

BBB permeability analysis revealed that the EB of brain cortex was dramatically increased in the vehicle-treated SAH group as compared to those of the sham-operated group (26.42 ± 2.0 vs. 9.37 ± 1.21 μg/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 1d). However, in the cysteamine-treated SAH group, EB content was significantly reduced as compared to the vehicle-treated SAH group (16.82 ± 1.51 vs. 26.42 ± 2.0 μg/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 1d), indicating that cysteamine treatment likely affords BBB permeability protection.

Influence of Cysteamine on Oxidative Stress in the Brain Cortex After SAH

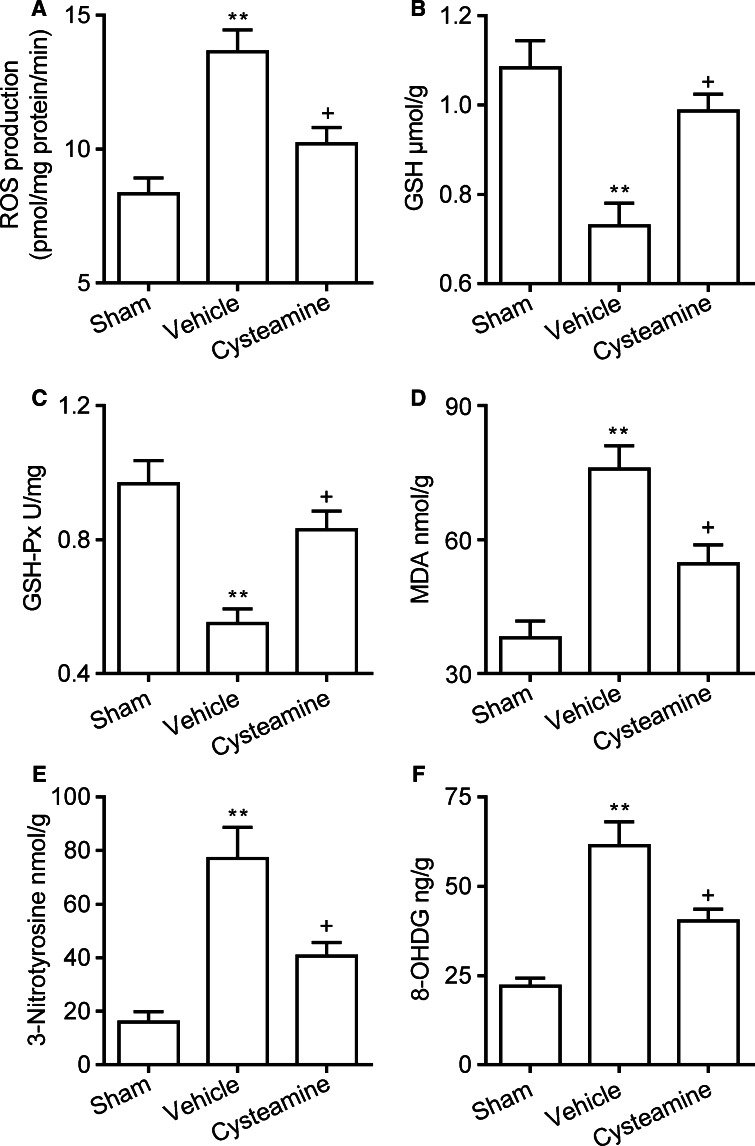

ROS level of brain cortex homogenate was significantly increased in the vehicle-treated SAH group as compared with the sham-operated group at 48 h (13.63 ± 0.81 vs. 8.33 ± 0.58 pmol/mg protein/min, P < 0.01, Fig. 2a). However, ROS production of brain cortex homogenate was decreased by cysteamine treatment as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group at 48 h (10.20 ± 0.61 vs. 13.63 ± 0.81 pmol/mg protein/min, P < 0.05, Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a ROS production of cerebral cortex homogenate, b GSH concentration, c GSH-Px activities, d MDA concentration, e 3-NT concentration, f 8-OHDG concentration of cerebral cortex in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. Values are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, each group). **p < 0.01 compared to sham-operated group; p < 0.05 compared to vehicle-treated SAH group

SAH significantly decreased the GSH concentration (0.73 ± 0.05 vs. 1.08 ± 0.06 μmol/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 2b) and GSH-Px enzyme activity (0.55 ± 0.04 vs. 0.96 ± 0.07 U/mg, P < 0.01, Fig. 2c) in brain cortex as compared with that observed in the sham-operated group at 48 h. In the cysteamine-treated SAH group, GSH concentration (0.98 ± 0.04 vs. 0.73 ± 0.05 μmol/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 2b) and GSH-Px enzyme activity (0.83 ± 0.05 vs. 0.55 ± 0.04 U/mg, P < 0.05, Fig. 2c) were dramatically increased as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group at 48 h.

MDA, 3-NT, and 8-OHDG are oxidative damage markers of lipid, protein, and DNA damage, respectively. SAH significantly increased the concentration of MDA (75.77 ± 5.24 vs. 38.03 ± 3.73 nmol/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 2d), 3-NT (77.03 ± 11.63 vs. 15.87 ± 3.98 nmol/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 2e), and 8-OHDG (61.33 ± 6.69 vs. 22.17 ± 2.30 ng/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 2f) in brain cortex as compared with the sham-operated group at 48 h. In the cysteamine-treated SAH group, the concentration of MDA (54.63 ± 4.22 vs. 75.77 ± 5.24 nmol/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 2d), 3-NT (40.63 ± 5.06 vs. 77.03 ± 11.63 nmol/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 2e), and 8-OHDG (40.31 ± 3.28 vs. 61.33 ± 6.69 ng/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 2f) in brain cortex was significantly reduced as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group in brain cortex at 48 h.

Inhibition of Cortical Apoptosis After SAH by Cysteamine

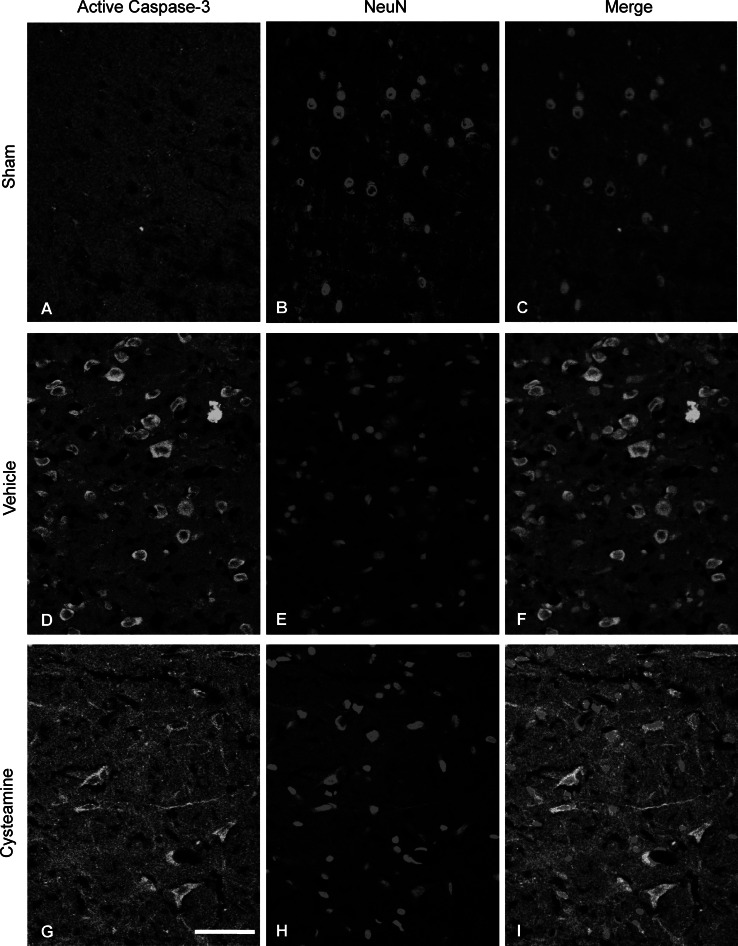

To determine whether cysteamine prevents cortical apoptosis, we assessed brain cortex in each group by TUNEL, active caspase-3/NeuN (a general neuronal marker) staining. Figures 3 and 4 showed that numerous TUNEL-positive cells and active caspase-3/NeuN double positive-stained neurons were observed in brain cortex of vehicle-treated SAH group as compared with sham-operated group (P < 0.001, Figs. 3, 4, 5a, b). However, the numerous TUNEL-positive cells and active caspase-3/NeuN double positive-stained neurons were significantly decreased in cysteamine-treated SAH group as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group (P < 0.001, Figs. 3, 4, 5a, b). Moreover, Western blot analysis revealed that significant up-regulation of cleaved caspase-3 expression in the vehicle-treated SAH group compared with that in the sham-operated (P < 0.01, Fig. 5c). An obvious down-regulation of cleaved caspase-3 expression was found in the cysteamine-treated SAH group compared with that observed in the vehicle-treated SAH group (P < 0.05, Fig. 5c). LDH activity has been widely used to evaluate the presence of damage and toxicity of tissue and cells. Using this assay, LDH activity was measured in brain cortex at 48 h post-SAH in three groups. Figure 5d illustrates that SAH significantly increased the LDH enzyme activity (9,057 ± 459 vs. 5,109 ± 388 U/g, P < 0.01, Fig. 5d) as compared with sham-operated group. However, when treatment with cysteamine, LDH enzyme activity (7,003 ± 402 vs. 9,057 ± 459 U/g, P < 0.05, Fig. 5d) was significantly decreased as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group.

Fig. 3.

Representative confocal images show TUNEL staining of cerebral cortex in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. The sham-operated group shows almost no TUNEL-positive cells (c). There are numerous TUNEL-positive cells in the vehicle-treated SAH group (f) and fewer TUNEL-positive cells in the cysteamine-treated SAH group (i). Scale bar is 100 μm in (a)–(i)

Fig. 4.

Representative confocal images show double immunofluorescent staining of active caspase-3 and NeuN of cerebral cortex in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. The sham-operated group shows almost no active caspase-3/NeuN-positive cells (c). There are numerous active caspase-3/NeuN-positive cells in the vehicle-treated SAH group (f), and fewer active caspase-3/NeuN-positive cells in the cysteamine-treated SAH group (i). Scale bar is 100 μm in (a)–(i)

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis of a TUNEL and b active caspase-3/NeuN-positive cells, c expression of cleaved caspase-3, d LDH activities of brain cortex in cerebral cortex in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. Values are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, each group). ***p < 0.001 or **p < 0.01 compared to sham-operated group; + p<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated SAH group

Cysteamine Increases BDNF Concentration After SAH

To examine whether cysteamine may affect production of BDNF after SAH, the BDNF concentration of brain cortex was measured by ELISA assay. As shown in Fig. 6, in the cysteamine-treated SAH group, BDNF concentration of brain cortex was significantly increased as compared with the vehicle-treated SAH group in brain cortex at 4 h (56.60 ± 3.79 vs. 37.20 ± 3.07 pg/mg protein, P < 0.05, Fig. 6) or 24 h (67.73 ± 4.03 vs. 48.90 ± 3.71 pg/mg protein, P < 0.05, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

BDNF concentration of cerebral cortex in the sham-operated group, vehicle-treated or cysteamine-treated SAH group. Values are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6, each group). *p < 0.05 compared to the vehicle-treated SAH group

Discussion

The present study showed that intraperitoneal administration of cysteamine (20 mg/kg/day) was protective for EBI after SAH at least partly through its antioxidative and anti-apoptotic effects. This conclusion came from the following results: cysteamine significantly improved neurological deficits, ameliorated brain edema and BBB permeability, suppressed oxidative stress, and cortical neuron apoptosis at 48 h after SAH in rat models. Cysteamine evidently decreased the SAH-induced formation of LDH, MDA, and ROS, while increased GSH-Px activities and the concentration GSH and BDNF. These findings suggest that treatment with cysteamine may provide an effective method for protecting the brain against EBI following SAH in rats.

The term EBI refers to the acute injury within the first 72 h follow SAH. The possible mechanisms involving EBI may contain increased intracranial pressure, decreased cerebral perfusion pressure, BBB breakdown, brain edema, oxidative stress, and neuronal cell apoptosis (Ayer and Zhang 2008; Sehba et al. 2012). Oxidative stress-mediated lipid peroxidation, protein breakdown, and DNA damage, which cause the cellular dysfunction and/or apoptosis, arise mostly in endothelial cells and nerve cells. In experimental SAH, the apoptosis of endothelial cells is associated with disruption of BBB and brain edema; Neuronal apoptosis is related to the development of neurological deficits (Ayer and Zhang 2008; Sehba et al. 2012). In our study, SAH lead to neurobehavioral deficits and brain edema, while increasing BBB permeability in rat models. However, cysteamine treatment improves the neurological outcome and alleviates brain edema and BBB permeability after experimental SAH. It is important to clarify that cysteamine attenuates EBI following the blood injection model of mild SAH.

Intrinsic antioxidant systems, such as GSH and GSH-Px, protect brain tissue from the potential harmful effects of ROS, while inhibit intrinsic antioxidant systems and decrease levels of cellular antioxidants are implicated in SAH-induced brain oxidative damage (Ayer and Zhang 2008). In accordance with previous studies, the present study found that SAH increased the ROS level, and decreased the GSH concentration and GSH-Px activity in brain cortex of rat. Cysteamine inhibits the post-SAH elevated ROS production and restore the SAH-induced GSH and GSH-Px reduction. Meanwhile, current results observed the increased expression of MDA, 3-NT, and 8-OHDG in brain cortex after SAH, which are oxidative markers of lipid, protein, and DNA injury. Administration of cysteamine attenuated post-SAH elevated the concentration of MDA, 3-NT, and 8-OHDG. These results indicate the antioxidant activity of cysteamine as a potential mechanism for its protective effect after SAH.

Cell apoptosis occur in neuron, astrocyte, oligodendrocyte, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell after SAH and play a key role in the pathogenesis of EBI (Friedrich et al. 2012). Our results show that cysteamine alleviated post-SAH elevated the number of TUNEL-positive cells and active caspase-3-positive neurons of brain cortex in rat. Administration of cysteamine also attenuated post-SAH elevated the active caspase-3 and LDH activity of brain cortex. These findings indicate that the anti-apoptotic effect of cysteamine as a potential mechanism against SAH-induced EBI. Our result also indicated that treatment of cysteamine could increase the concentration of BDNF in brain cortex after SAH. BDNF is a growth factors and the effect on neuronal survival. Although it is not tested in this study, the mechanism under the up-regulation of BDNF by cysteamine might be similar to that suggested by previous reports (Goggi et al. 2003; Borrell-Pages et al. 2006), where cysteamine can directly enhance BDNF production through a heat shock protein-dependent mechanism.

The mechanisms of action of cysteamine have recently been reviewed by Besouw et al. (2013). Cysteamine can deplete lysosomal cystine in cystinosis, increase cellular GSH levels, change the enzymatic activity by bind to thiol groups, and change various gene expression. It is worthwhile to note that the effects of cysteamine are related to doses of administration. Regarding the dose of cysteamine used in present study, we adopted from L. Sun et al. (2010b); (Kessler et al. 2008a, b). Our results showed that cysteamine (20 mg/kg/day), but not cysteamine (100 mg/kg/day, mortality rate (80 % [8 of 10 rats], the data not shown), confers protection against SAH-induced EBI. This is similar to the previous reports that high dose of cysteamine caused toxicity in mice (Sun et al. 2010b; Hunyady et al. 2001).

Conclusion

The current study shows that intraperitoneal administration of cysteamine (20 mg/kg/day) confers protection against SAH-induced EBI in rats through the inhibition of oxidative stress and the promotion of BDNF production in vivo. Neurobehavioral deficit was improved; brain edema and BBB permeability were attenuated; oxidative stress and cortical apoptosis were reduced after cysteamine treatment. These finding suggest that cysteamine may be a candidate treatment for EBI after SAH.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 81301018 for Z.Z. and No. 81471212 for B.S.).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Footnotes

Zong-yong Zhang, Ming-feng Yang, and Tao Wang have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Zong-yong Zhang, Email: zongyongzhanghust@gmail.com.

Bao-liang Sun, Email: blsun88@163.com.

References

- Ayer RE, Zhang JH (2008) Oxidative stress in subarachnoid haemorrhage: significance in acute brain injury and vasospasm. Acta Neurochir Suppl 104:33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry C, Turner RJ, Corrigan F, Vink R (2012) New therapeutic approaches to subarachnoid hemorrhage. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 21(6):845–859. doi:10.1517/13543784.2012.683113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besouw M, Masereeuw R, van den Heuvel L, Levtchenko E (2013) Cysteamine: an old drug with new potential. Drug Discov Today 18(15–16):785–792. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Pages M, Canals JM, Cordelieres FP, Parker JA, Pineda JR, Grange G, Bryson EA, Guillermier M, Hirsch E, Hantraye P, Cheetham ME, Neri C, Alberch J, Brouillet E, Saudou F, Humbert S (2006) Cystamine and cysteamine increase brain levels of BDNF in Huntington disease via HSJ1b and transglutaminase. J Clin Investig 116(5):1410–1424. doi:10.1172/JCI27607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinsky R, Gray C (2006) CYTE-I-HD: phase I dose finding and tolerability study of cysteamine (Cystagon) in Huntington’s disease. Mov Disord 21(4):530–533. doi:10.1002/mds.20756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich V, Flores R, Sehba FA (2012) Cell death starts early after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci Lett 512(1):6–11. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggi J, Pullar IA, Carney SL, Bradford HF (2003) Signalling pathways involved in the short-term potentiation of dopamine release by BDNF. Brain Res 968(1):156–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis P, Graftieaux JP, Sercombe R, Hettler D, Scherpereel B, Rousseaux P (2010) Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of high-dose methylprednisolone in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 112(3):681–688. doi:10.3171/2009.4.JNS081377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunyady B, Palkovits M, Mozsik G, Molnar J, Feher K, Toth Z, Zolyomi A, Szalayova I, Key S, Sibley DR, Mezey E (2001) Susceptibility of dopamine D5 receptor targeted mice to cysteamine. J Physiol Paris 95(1–6):147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A, Biasibetti M, Da Silva Melo DA, Wajner M, Dutra-Filho CS, De Souza Wyse AT, Wannmacher CM (2008a) Antioxidant effect of cysteamine in brain cortex of young rats. Neurochem Res 33(5):737–744. doi:10.1007/s11064-007-9486-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A, Biasibetti M, Feksa LR, Rech VC, Melo DA, Wajner M, Dutra-Filho CS, Wyse AT, Wannmacher CM (2008b) Effects of cysteamine on oxidative status in cerebral cortex of rats. Metab Brain Dis 23(1):81–93. doi:10.1007/s11011-007-9078-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutiyanawalla A, Terry AV Jr, Pillai A (2011) Cysteamine attenuates the decreases in TrkB protein levels and the anxiety/depression-like behaviors in mice induced by corticosterone treatment. PLoS One 6(10):e26153. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai A, Veeranan-Karmegam R, Dhandapani KM, Mahadik SP (2008) Cystamine prevents haloperidol-induced decrease of BDNF/TrkB signaling in mouse frontal cortex. J Neurochem 107(4):941–951. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05665.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JT, Khomenko T, Szabo S, McLaren GD, Denton TT, Krasnikov BF, Jeitner TM, Cooper AJ (2009) Measurement of sulfur-containing compounds involved in the metabolism and transport of cysteamine and cystamine. Regional differences in cerebral metabolism. J Chromatogr B 877(28):3434–3441. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehba FA, Hou J, Pluta RM, Zhang JH (2012) The importance of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol 97(1):14–37. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh CH, Hong CJ, Huang YH, Tsai SJ (2008) Potential antidepressant properties of cysteamine on hippocampal BDNF levels and behavioral despair in mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32(6):1590–1594. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BL, Shen FP, Wu QJ, Chi SM, Yang MF, Yuan H, Xie FM, Zhang YB, Chen J, Zhang F (2010a) Intranasal delivery of calcitonin gene-related peptide reduces cerebral vasospasm in rats. Front Biosci 2:1502–1513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Xu S, Zhou M, Wang C, Wu Y, Chan P (2010b) Effects of cysteamine on MPTP-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in mice. Brain Res 1335:74–82. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ (2007) Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet 369(9558):306–318. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Wang L, Liu M, Wu B (2010) Tirilazad for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD006778. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006778.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZY, Sun BL, Yang MF, Li DW, Fang J, Zhang S (2014) Carnosine attenuates early brain injury through its antioxidative and anti-apoptotic effects in a rat experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage model. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi:10.1007/s10571-014-0106-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]