Abstract

Organoids have been an exciting advancement in stem cell research. Here we describe a strategy for directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into distal lung organoids. This protocol recapitulates lung development by sequentially specifying human pluripotent stem cells to definitive endoderm, anterior foregut endoderm, ventral anterior foregut endoderm, lung bud organoids and finally lung organoids. The organoids take ~40 d to generate and can be maintained more than 180 d, while progressively maturing up to a stage consistent with the second trimester of human gestation. They are unique because of their branching morphology, the near absence of non-lung endodermal lineages, presence of mesenchyme and capacity to recapitulate interstitial lung diseases. This protocol can be performed by anyone familiar with cell culture techniques, is conducted in serum-free conditions and does not require lineage-specific reporters or enrichment steps. We also provide a protocol for the generation of single-cell suspensions for single-cell RNA sequencing.

Introduction

Organoids are used to study human development and to model disease1,2. Among others, major progress has been made in the generation of lung organoids3,4. The lung epithelium contains multiple cell types, including basal, ciliated, secretory, goblet and neuroendocrine cells in the airways, and alveolar epithelial type 1 (AT1) and surfactant-producing alveolar epithelial type 2 (AT2) cells in the alveoli, where gas exchange takes place4,5. In addition, several novel transitional cell populations have been identified in the human distal lung respiratory airway or terminal respiratory bronchioles, very small airways in which alveoli empty and that contain more extensive alveoli at their distal tips6–8.

The respiratory system originates from buds that arise on the ventral aspect of the anterior foregut endoderm (AFE) during embryonic stage (E9.5–E12.5 in the mouse, 4–7 post-conception weeks (pcw) in humans). These undergo a stereotyped branching process during the pseudoglandular stage (E12.5–E16.5 in the mouse, 5–17 pcw in humans). During the canalicular stage (E16.5–E17.5 in the mouse, 16–26 pcw in humans) cell cycle activity decreases and specialization of the airway epithelium occurs in the stalks, with the emergence of basal, goblet, club, ciliated and other cell types. This stage is followed by the saccular stage, where the canaliculi widen into sacculations that will give rise to primitive alveoli (E17.5 to birth in the mouse, 26–38 pcw in humans)5,9–11. Expansion of alveolar number by further differentiation of immature saccules, alveolar maturation and secondary septation continue predominantly postnatally (alveolar stage, postnatal days 0–21 (d0-21) in mice, 38 pcw to the age of 21 years in humans)11,12. Generating organoids that at least partially model human lung development requires recapitulating this process to the extent possible in vitro.

Since the first reports on their establishment from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs)13,14, several publications showed the generation of lung organoids, either from fetal or adult lung15–18 or from hPSCs19–26. We developed a directed differentiation strategy of hPSCs (both embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)) into three-dimensional (3D) lung organoids that undergo a process similar to branching morphogenesis and that we have used to model fibrotic interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) and viral infection20,27,28.

This protocol (Fig. 1a) begins by replicating early lung development through successive specification of definitive endoderm (DE) and AFE according to protocols we established previously (Fig. 1b, i–iii, d4.3, d6.3)20,29,30. Subsequently, small organoids that are endowed with the expression patterns associated with lung buds in vivo (hence the name ‘lung bud organoids’ or LBOs, Fig. 1b, iv–vi, d8, d9, d15) are generated in suspension culture20. These LBOs can give rise to lung and airway structures after transplantation under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice or can be embedded in Matrigel20, where a process similar to branching morphogenesis ensues and organoids arise that expand more than 6 months (Fig. 1b, vii, viii, d42, d70). Genome-wide expression analysis and benchmarking against the Keygenes database31, which contains tissues from the first and second trimester of human gestation and of adult humans, revealed that organoids at d170 corresponded best to lung in the second trimester of human gestation20. At these later stages of the cultures, AT2 cells arise at the tips. These contain lamellar bodies (LBs) by transmission electron microscopy and can take up and secrete fluorescently labeled surfactant protein B (SFTPB)20, features specific to AT2 cells. Mesenchyme appears during the anteriorization and ventralization stages and becomes scarce after development in Matrigel20. This may correspond to the attrition of mesenchyme during lung development32.

Fig. 1 |. Overview of the protocol.

a, Schematic representation of the distinct stages of the protocol. b, Representative brightfield images at indicated days of the protocol. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Applications of the method

The most unique feature of the organoids described here is the presence of mesenchyme that allows studies of epithelial–mesenchymal interactions and therefore recapitulation and modeling of at least some ILDs. ILDs are a heterogeneous group of entities with diverse or unknown etiologies affecting the lung interstitium33. Development of pulmonary fibrosis (PF), most commonly associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), portends the worst prognosis33,34. Injury to AT2 cells probably plays a critical role in the development of both familial and sporadic IPF, as mutations causing familial IPF specifically affect AT2 function, while depletion of AT2 cells in mouse models is associated with fibrosis35. In addition, a fraction of patients with familial IPF have heterozygous mutations in telomerase components or other genes involved in telomere maintenance36–43. Furthermore, several susceptibility loci have been identified that affect telomere length44. As telomeropathy affects stem cell function and AT2 cells are facultative distal lung stem cells4,45, these associations suggest a role for AT2 cells.

Finding therapeutic targets and novel drug treatments requires models to dissect pathogenetic mechanisms, identify biomarkers, discover drug targets and perform drug testing. It has been challenging to model ILDs in animal models34,35,46–48. A complementary, more malleable, but also more reductionist avenue are lung organoids derived from hPSCs. We showed that PF caused by mutation in Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome (HPS) genes could be modeled28. HPS is a genetic syndrome caused by abnormal biogenesis and trafficking of lysosome-related organelles and characterized by hypopigmentation, bleeding diathesis and in some but not all genotypes, PF, also known as HPS-associated interstitial pneumonia (HPSIP). Fibrosis in HPSIP is most probably linked to the fact that homeostasis of LBs in AT2 cells is abnormal and surfactant secretion is reduced, as LBs are also lysosome-related organelles49. Of the nine genotypes, only three (HPS1, 2 and 4) are clinically associated with HPSIP. Accordingly, we found that only organoids derived from ESCs with mutation in HPS1, 2 or 4 showed fibrotic changes, whereas organoids with a mutation in HPS8, which is clinically not associated with fibrosis, did not28. This model therefore recapitulates the clinical incidence of PF in HPS. By comparing genome-wide expression data from epithelial cells isolated from lung organoids generated from the fibrosis prone (HPS1−/− and HPS2−/−) and non-fibrosis-prone (HPS8−/−) mutants, we furthermore identified interleukin-11 as a therapeutic target critical to fibrosis. This provides proof-of-principle evidence that pathogenetic mechanism and therapeutic targets can be identified using lung organoids with mutations associated with diseases28.

The organoids can also be used to model viral infection. They can be infected by respiratory viruses, such as respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza and measles. We showed that the organoids are authentic infection models that do not promote the emergence of culture-adapted variants in the propagation of parainfluenza27. In the case of respiratory syncytial virus, we could show that infected epithelial cells are dislodged into the lumen, as is observed in bronchiolitis caused by this virus49.

The organoids can also be used for modeling human lung development. As an example, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) and confocal analysis is presented in the ‘Anticipated results’ section, showing progressive loss of other endodermal fates present early in organoid development, and reciprocal acquisition of a distal lung fate. This model can therefore be used to examine relevant signaling pathways as well as transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of the progressive specification of distal lung. The fact that undifferentiated endoderm remains present in organoids early in development suggests that it is possible that by changing the culture conditions, other endodermal fates could be obtained, which may constitute another potential application of this model. The spontaneous formation of branching structures also suggest that this model could be used to study branching morphogenesis in the lung.

Comparison with other methods

Since the first reports on their establishment from hPSCs13,14, several publications showed the generation of lung organoids, either from fetal or adult lung15–18 or from hPSCs19–26. In many cases, the structures are limited in size or contain, often by design, specific cell types (airway23,26,50 or AT2 cells19,24,51). The lung organoids described here present several unique features compared with others as a model of human distal lung development.

Branching morphogenesis

A first feature is that they undergo a process similar to branching morphogenesis and that the full potential to generate lung and airways is present in the early organoids. While differentiation is biased toward distal lung in the conditions we use in vitro (described here in this protocol), the early-stage lung organoids (LBOs in suspension) generate structures containing branching tubules with proximodistal specification when embedded in donor-derived mesenchyme after transplantation under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice20. Another group (the protocol described in Miller et al.22) also reported generation of 3D human lung organoids from hPSCs13,14. While these smaller structures contained cells expressing markers of lung and airway14 and have some airway potential after subcutaneous xenografting in mice13, they did not show branching structures. However, these organoids were similar to our reported organoids, staged as early fetal lung22.

Pulmonary mesenchyme

Another notable feature of the distal lung organoids described here is the presence of mesenchyme, the origin of which is unclear. Mesenchyme could already be detected during the AFE stage of the protocol, remains present and relatively abundant during the LBO (suspension) stage, and becomes scarce, but still detectable after development to at least d60 in Matrigel20. The mesenchymal cells can be isolated by cell sorting for EPCAM−THY+ cells28. RNAseq20 as well as scRNAseq (see ‘Anticipated results’) showed that this mesenchyme expresses genes associated with pulmonary mesenchyme (including WTN2B52 and TBX4 (ref. 53)). The presence of mesenchyme is shared with the protocol of Miller et al., although they did not further characterize the mesenchyme22. The presence of mesenchyme in our organoids may explain what is probably the most unique application of these organoids, the capacity to recapitulate at least one ILDs: HPSIP. Together, these findings indicate that these distal lung organoids can represent an integrated model of distal lung development and disease.

Differentiation efficiency

A final distinguishing feature of the organoids described here is that any intervening purification steps are unnecessary. The in vitro generation of NKX2.1+ lung progenitors with high efficiency is a critical but challenging step. To resolve this issue, several groups have developed strategies based on lineage-specific reporters to isolate these before further differentiation and maturation. In two reports from the same laboratory, McCauley et al.54 specified lung progenitors, and isolated NKX2.1GFP+ cells at d15 for further culture in Matrigel 3D medium to yield proximal airway spheroids devoid of distal potential, while Jacob et al.19 resorted to a NKX2.1GFPSFTPCtdTomato reporter cell line to isolate NKX2.1GFP+SFTPCtdTomato+ cells for further culture in Matrigel to generate spheroids containing AT2 cells. While these protocols are advantageous when differentiation efficiency is modest, they only allow for studies using these specific reporter lines. To resolve this problem, surface markers were identified by which NKX2.1+ lung progenitors can be isolated from the cultures. Gotoh et al. reported carboxypeptidase M (CPM) as a specific marker of NKX2.1+ progenitors24, which was then used by Konishi et al.26 to select for NKX2.1+ cells. Hawkins et al. used differential expression of CD47 and CD26 to show that CD47hiCD26lo cells are enriched in NKX2.1+ lung progenitors55. However, a rigorous head-to-head comparison with reporter lines has not been performed.

The reasons why neither reporter cells nor cell sorting are required in our protocol are unclear. We speculate that some differences in our protocol may offer an explanation. We grow hPSCs in the presence of feeders, as we have found that passage in feeder-free conditions compromises future lung potential. Second, although commercial kits to generate DE have been recommended and are widely used56, we found that, while DE generation was indeed efficient, the lung potential of the DE generated was suboptimal. We therefore adhere to a strict protocol to generate DE using reagents that have to be lot tested. We also generate DE in 3D embryoid bodies, and not in two-dimensional (2D) cultures. Finally, the LBO suspension culture step may select for cells specified to pulmonary epithelium and mesenchyme. The same may be true for the Matrigel step. Indeed, scRNAseq analysis suggests progressive acquisition of a distal lung at the expense of other endodermal fates over the first 80 d of the protocol (see ‘Anticipated results’).

A serum-free model

The published protocol that is the most closely related to the protocol described here was by Miller et al.22. However, the factors used in the latter differ from ours. In the specification of AFE they also use, in addition to BMP and TGF-β inhibition, Wnt agonism, FGF4 and Smoothened agonist. They do not include an extended period of suspension culture (which in the protocol described here generates LBOs). Furthermore, and importantly, they use fetal bovine serum (FBS) in their base medium, which we try to avoid as this is an uncharacterized reagent. Miller et al. do obtain proximal and some distal lung specification in the presence of serum, and in conditions similar to ours (but without BMP4 and FGF10) they obtain small spherical ‘bud tip’ organoids. The organoids we describe here do not develop in the presence of serum (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 |. FBS-containing media does not maintain organoid cultures.

Tile scan of brightfield images showing the morphological changes of a d47 organoid switched to FBS-containing media. Scale bars, 1 mm.

Development and disease modeling

As mentioned before, the organoids of Miller et al. are much smaller and do not show branching. Commonalities between both types of organoids are the capacity to generate lung and airway structures after transplantation under the kidney capsule of immunodeficient mice, the presence of mesenchyme and the fact that repeated enrichment steps are not required. In contrast to the current protocol, that of Miller et al. has not been reported to be useful in modeling ILDs, and was not reported to be infectable by the viruses we used20,27. Both models will probably serve complementary goals. The capacity to generate airway cells in the protocol of Miller et al., for example, may allow studies on airway development and proximodistal specification, whereas the organoids reported here will allow investigation of branching morphogenesis and alveolar specification, in addition to modeling ILDs.

We have also previously reported on a protocol in Collagen I (Col I) gels that allows further maturation of lung cells in 3D21,57. This Col I protocol and the resulting organoids are distinct from the protocol described here. Rather than generating 3D LBOs in suspension culture, the Col I protocol continues lung progenitor specification in 2D, followed by plating into Col I gels. The Col I model is, in contrast to the organoids described here, permissive for the specification of all distal and airway lineages after retraction of CHIR99021 (CHIR), including cells compatible with AT1 cells. This finding is consistent with the observations of Kanagaki et al. in fibroblast-dependent alveolar organoids58. However, retraction of CHIR in the distal lung organoids described here results in cell death and disintegration. In vitro, we were therefore not able to achieve induction of AT1 markers in lung organoids generated using the protocol described here. However, we do note that after transplantation under the kidney capsule, LBOs could generate cells expressing AT1 markers20, suggesting that the potential exists, but that the correct in vitro conditions for AT1 generation have not yet been identified for these organoids.

In addition, while in most studies the maturity of the generated cells goes unreported or is equivalent to the second trimester of human gestation21, the cells generated by our Col I protocol exhibit transcriptomic profiles, ultrastructure and an array of lineage-specific markers that also partially match postnatal lungs21. Several mature cell types can be isolated using surface markers. Most notably, the Col I protocol allowed the generation NGFR+ basal cells, the stem cells of the postnatal airway59, which can be isolated and further expanded using established techniques60. On the other hand, and in contrast to the model described here, modeling fibrotic lung disease was not possible, and mesenchymal cells were not present. Both models are therefore complementary. The reason why both protocols behave differently is most likely linked to differences in the early stages of directed differentiation and the different extracellular matrices used to embed the organoids. The underlying mechanisms merit further investigation.

Limitations

Even after 6 months of culture in Matrigel, the organoid model matches the second trimester of human gestation on the basis of genome-wide expression analysis. The expression of SFTPC, a marker of mature AT2 cells occurs late in the culture (d170) and is not universal (Fig. 3a), although all other AT2 markers studied (SFTPB, ABCA3, LPCAT, NAPSA, SLC34A2) reproducibly and progressively increase and are consistently expressed by a majority of the cells by d80 (see ‘Anticipated results’). We have previously shown the presence of LBs and capacity to take up and release SFTPB in organoids >d120 old, indicating long-term maintenance of still immature AT2 cells20. The combination of CHIR, FGF7 and dexamethasone, cAMP and IBMX has been reported to be necessary for the expansion and maintenance of so-called alveolospheres generated from hPSC-derived lung progenitors. Even here, however, maintaining SFTPC expression was challenging and required repeated sorting for a reporter, as well switching the culture conditions between presence and absence of CHIR19,56. We also note that in the organoid protocol of Miller et al.22, SFTPC expression was rare.

Fig. 3 |. Maturation of organoids and selection of suspension organoids for embedding.

a, Induction of select AT2 markers in RNAseq studies (data from ref. 20, mean ± s.e.m.). RPKM, reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. b, Representative images of d20 LBOs. The upper row shows organoids that we prefer not to pick due to the dense center and hollowing structures. The lower row shows ‘good’ organoids with folding epithelial structures and clear and transparent center.

Even though we observed a process reminiscent of branching morphogenesis, the branching is not well organized. The structures branch randomly in every direction and appeared disorganized, probably because neither directional cues nor physical constraints, such as a thoracic cavity, are provided. In addition, the exact nature and patterning of the mesenchyme present is unclear and the proportion declines along the culture time. The mesenchyme does not have the potential to generate endothelial cells in vivo after transplantation under the kidney capsule, although smooth muscle and occasional cartilage were present20. Endothelial cells or blood vessels have also not been observed in vitro in our model. Furthermore, we could not achieve induction of AT1 markers in vitro, although AT1 markers were observed after engraftment in vivo20. Terminal and architecturally fully appropriate maturation of organoids is still a challenge for the field in general. Finally, the use of Matrigel to embed LBOs and serum to inactive enzymatic activities in this model is still a barrier for translational research. The use of Matrigel might be replaced with synthetic hydrogels. However, when LBOs, generated using the protocol described here, were embedded in Col I gels, they did not show branching (Fig. 4). We do not know whether this is due to the molecular composition or the stiffness of Matrigel that allows branching morphogenesis of LBOs. Hence, the choice of 3D medium for embedding should take these two factors into consideration. The use of serum to inactivate enzymes in the protocol can be easily substituted with purified protease inhibitors.

Fig. 4 |. Morphology of lung organoids embedded in Col I gel.

Tile scan of a brightfield image showing the morphology of d50 organoids grown in the Col I gel. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Experimental design

A schematic of the protocol with examples of the typical morphologies at each stage is shown in Fig. 1. We maintain hPSCs on feeder cells. The protocol begins with mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) depletion (d1, Fig. 1b, i) followed by a stepwise, sequential induction of DE (d0–4, Fig. 1b, ii) and AFE (d5–6, Fig. 1b, iii) as previously described20,61. hPSCs are passaged on Matrigel-coated plates to deplete residual MEFs for ~24 h (Steps 1–13). After MEF depletion, primitive streak and embryoid body induction is performed in embryoid bodies/primitive streak (EB/PS) medium in ultralow-attachment plates for 12–16 h (Steps 14–27). This is followed by switching to DE induction medium for another 76–80 h (d4; Steps 28–42). Essential in this step is exposure to high concentrations of Activin A. DE can be generated both in 2D adherent cultures and or in 3D as EBs in low-attachment plates. We found that lung potential is maintained the best in EBs. DE purity is verified by flow cytometry after staining for EPCAM, cKIT and CXCR4 (Steps 43–66)20,61. It is essential that more than 90% of the cells express high levels of these three markers. Others have recommended the use of commercial kits to generate DE56. We found that while generation of DE was efficient, the potential of these DE cells to generate lung and airway cells was more limited.

High-purity DE (>90%) is directed to AFE via inhibition of TGF-β, BMP and WNT signaling by SB 431542, NOGGIN and IWP2, respectively (Steps 67–89)29,30,61. At the end of AFE induction (d6), cells are treated with ventralization medium in the presence of BMP4, FGF10, FGF7, all-trans retinoic acid (RA) and the glycogen synthase kinase 3β antagonist, CHIR for 48 h (Steps 90–92). At this time, formation of loosely adherent clumps can be observed (Fig. 1b, iv). Next, LBOs are generated (Steps 93–99). This is accomplished by resuspending clumps of cells at d8 and maintaining those in ultra-low-attachment plates in the presence of CHIR, FGF10, FGF7, BMP4 and RA, where they will form spheres consisting of folding epithelial sheets interspersed with mesenchymal cells (Fig. 1b, v, vi and Fig. 3b). The majority of the epithelial cells will express early, but not mature lung markers, and have an expression profile consistent with lung bud epithelium. The mesenchymal cells express markers consistent with pulmonary mesenchyme, and can make up 5–20% of the population by flow cytometry20.

In the final stage (Steps 100–117), the LBOs are plated in Matrigel with CHIR, FGF10, FGF7, BMP4 and RA, where they undergo outward budding followed by a process similar to branching morphogenesis (Fig. 1b, vii, viii). Other alternatives can be used, such as Cultrex (R&D Systems), which in our hands gave similar results. We recommend growth factor-reduced Matrigel, as multiple factors at various concentrations may otherwise be present that could unpredictably affect organoid development, and therefore reproducibility. The mesenchyme is gradually lost after embedding in Matrigel. Approximately 90% of LBOs will yield rapidly expanding branching structures in which the fraction cells expressing a constellation of AT2 markers gradually increases, such that by d80, these form the majority of the cells (see ‘Anticipated results’). The organoids can be maintained in culture for more than 6 months. The entire protocol is conducted serum-free conditions.

We found that several medium constituents need to be lot tested. These include Activin A, N2 and B27 medium, and Knockout Serum Replacement (see ‘Reagents’). Lot testing involves comparative analysis for maximal efficiency of DE generation as evaluated by expression of EPCAM, cKIT and CXCR4 by flow cytometry. We found lot testing of Matrigel for organoid formation not necessary.

The cultures can be analyzed at any step of the differentiation using several approaches, including immunofluorescence (IF; Box 1), reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR; Box 1), electron microscopy, RNAseq and western blot, as we published previously20,27,28. We provide an example of IF (Fig. 5, antibodies in Table 1) and RT–qPCR analysis (Fig. 6, primer sequences in Table 2). Additionally, the cultures can be analyzed by scRNAseq (Boxes 2 and 3). As the quality of the input single-cell suspension is critical to scRNAseq, we provide a protocol to generate single-cell suspension from organoids in Matrigel (Box 2). In the ‘Anticipated results’ section, we provide an example of scRNAseq analysis (Figs. 7 and 8).

Box 1 |. Standard methods to analyze lung organoids.

RT–qPCR ● Timing 4 h (hands on, 2 h)

Reagents

Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep Kit (Zymo, cat. no. R2060)

TRIzol (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 15-596-018)

Ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. E7023-500ML)

qScript XLT cDNA SuperMix (Quantabio, cat. no. 95161–100)

SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 43–687–08)

Nuclease free water (Ambion, cat. no. AM9937)

Disposables

1.5 ml RNase-/DNase-free Microcentrifuge tube (Nest Biotechnology, cat. no. 615601)

0.2 ml PCR tubes (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. NC9989922)

384-well reaction plate with barcode (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. 4309849)

Equipment

Vortex mixer (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 02215365)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf, cat. no. 5424R)

Thermal cycler T100 (Biorad, cat. no. 1861096)

Quant Studio Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. A28567)

Procedure

Aspirate the medium from the insert with lung organoid and add 300 μl of Trizol to the insert using a P1000. Pipette up and down several times to break the Matrigel and collect the content of the insert. Transfer the organoid in trizol into a 1.5 ml tube and vortex until homogenized.

Centrifuge the sample at 16,000g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove the residual Matrigel. Take the supernatant and mix with equal amount of 100% ethanol and vortex thoroughly.

Transfer the mixture into a Zymo-Spin IC Column in a Collection Tube and centrifuge for 30 s at 16,000g. Transfer the column into a new collection tube and discard the flow through.

In an RNase-free tube, add 5 μl DNase I (6 U/μl), 35 μl DNA Digestion Buffer and mix by gentle inversion. Add the mix directly to the column matrix. Incubate at room temperature (20–30 °C) for 15 min.

Add 400 μl Direct-zol RNA PreWash to the column and centrifuge. Discard the flow through and repeat this step.

Add 700 μl RNA Wash Buffer to the column and centrifuge for 1 min to ensure complete removal of the wash buffer. Transfer the column carefully into an RNase-free tube.

To elute RNA, add 15 μl of DNase-/RNase-free water directly to the column matrix and centrifuge.

- Reverse transcribe 100–1,000 ng of total RNA using the qScript XLT cDNA SuperMix. Combine following reagents in 0.2 ml microtubes:

Component Volume for 20 μl reaction qScript XLT cDNA SuperMix 4 μl RNA template Variable RNase-/DNase-free water Variable Total volume 20 μl After sealing each reaction, vortex gently to mix contents. Centrifuge briefly to collect components at the bottom of the reaction tube.

Incubate as follows: 5 min at 25 °C, 60 min at 42 °C, 5 min at 85 °C, hold at 4 °C. Use first-strand product for RT–qPCR amplification.

- For RT–qPCR, prepare technical triplicates of 15 μl reaction:

Component Volume for 15 μl reaction Sybr green 7.5 μl Forward primer (from 10 μM stock) 0.15 μl Reverse primer (from 10 μM stock) 0.15 μl cDNA Variable Water Variable Total volume 15 μl Prepare samples in a 384-well plate and run for 40 cycles. Use primers listed in Table 1. Calculate relative gene expression on the basis of the average cycle (Ct) value, normalized to GAPDH as the internal control and reported as fold change (2(-ddCT)).

IF ● Timing 2 d (hands on, 6–8 h)

Reagents

Paraformaldehyde 16% solution, EM grade (Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat. no. 15710)

Glycine (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G7126-100G)

PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Cellgro, cat. no. MT21031CM)

Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. X100-100ML)

Donkey serum (EMD Milipore, cat. no. S30-100ML)

DAPI (Thermo Fisher, cat. no. D1306)

Mounting reagent (OriGene Technologies, cat. no. E19-18)

Dry ice

Disposables

24-Well insert (Falcon, cat. no. 353095)

24-Well plate (Falcon, cat. no. 353047)

Cryo mold (Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat. no. 62534–15)

Microtome blade MB35 Premier (Thermo Scientific, cat. no. 3050835)

Adhesion microscope slides (Epredia, cat. no. 9991003)

Coverslips (Electron Microscopy Sciences, cat. no. 72290–06)

Equipment

Forceps (Dumont, cat. no. 11251–33)

Cryotome (Leica, cat. no. CM 3050-S)

Reagent setup

0.2% PBST: to make 100 ml of PBST mix 0.2 ml of 100% Triton with 99.8 ml of PBS.

4% paraformaldehyde: to make 40 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde mix 10 ml of 16% paraformaldehyde and 30 ml of PBS.

50 mM glycine: for 2.5 M glycine stock solution mix 93.8 g of glycine powder in 500 ml of water. For 100 ml of 50 mM solution mix 2 ml of 2.5 M stock solution with 98 ml of water.

2% donkey serum in 0.2% PBST: for 100 ml of the solution mix 2 ml of 100% donkey serum with 98 ml of 0.2% PBST.

5% donkey serum in PBS: for 100 ml of the solution mix 5 ml of donkey serum with 95 ml of PBS.

Procedure

Aspirate the medium and remove the insert from the 24-well plate. Invert it and gently peel off the membrane from the insert using forceps.

Excise the lung organoid and embed in a cryo-mold on dry ice.

Cut frozen samples on a cryotome at the thickness of 10–12 μm and collect on adhesion microscope slides and air dry.

Fix the samples in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, wash two times for 5 min in 50 mM glycine to inactivate the PFA, followed by washing in PBS.

Permeabilize samples for 10 min in 0.2% PBST (PBS + 0.2% Triton X-100) and block by incubating in PBS containing 5% donkey serum for 1 h, then incubate overnight in primary antibody in 0.2% Triton X-100 and 2% donkey serum (for primary antibodies and suggested dilutions, see Table 1).

The next day, wash the samples three times in PBS and 1% donkey serum and incubate with secondary antibody (1:200) for 1 h at the room temperature (for secondary antibodies, see Table 1). Stain nuclei with DAPI (1:500).

Mount sections with Mounting Reagent and coverslip. Slides are ready for the imaging when the mounting reagent dries properly.

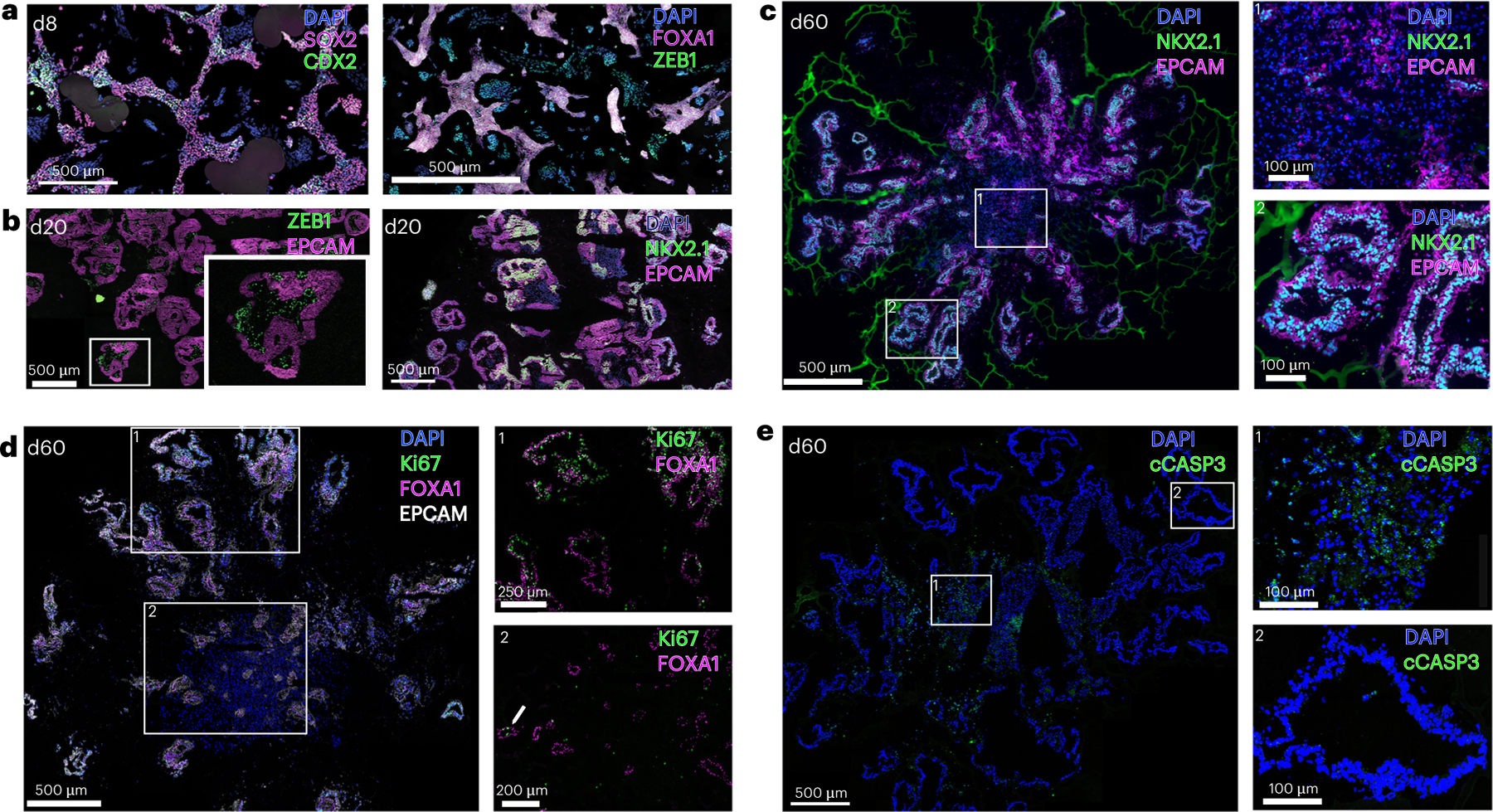

Fig. 5 |. IF analysis of organoids at different stages.

a, Tile scan image at d8 (ventralization) stained for indicated markers. b, Tile scan images and higher magnification fields (insets) of culture LBOs at d20 of the culture protocol. c–e, Confocal tile scans of ~d60 organoids stained for the indicated markers, and higher magnification images (right) corresponding to numbered boxes. All scale bars in a–e, 500 μm, except for the insets of d (250 μm upper, 200 μm lower) and the insets of c and e (100 μm).

Table 1 |.

Antibodies

| Primary antibodies for immunofluorescent staining | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Host species | Clone number | Manufacturer and cat. no. | RRID | Dilution factor |

| CDX2 | Rabbit | EPR2764Y | Abcam (cat. no. ab76541) | AB_1523334 | 1:400 |

| cCASP3 | Rabbit | 5A1E | Cell Signaling (cat. no. 9664S) | AB_2070042 | 1:400 |

| COL4 | Mouse | COL-94 | Abcam (cat. no. ab6311) | AB_305414 | 1:100 |

| EPCAM | Goat | Polyclonal | R&D Systems (cat. no. AF960) | AB_355745 | 1:400 |

| FOXA1 | Mouse | Q-6 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (cat. no. sc-101058) | AB_1124659 | 1:50 |

| HT2-280 | Mouse | TB-27 | Terrace Biotech (cat. no. TB-27AHT2-280) | AB_2832931 | 1:100 |

| hNUCL | Mouse | NM95 | Abcam (cat. no. ab190710) | — | 1:100 |

| KI-67 | Rabbit | D3B5 | Cell Signaling (cat. no. 9129S) | AB_2687446 | 1:200 |

| KRT13 | Rabbit | EPR3671 | Abcam (cat. no. ab92551) | AB_2134681 | 1:400 |

| MUCIN1 | Rabbit | EPR1023 | Abcam (cat. no. ab109185) | AB_10862483 | 1:400 |

| P63Α | Rabbit | D2K8X | Cell Signaling (cat. no. 13109) | AB_2637091 | 1:200 |

| PROSPC | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Millipore Sigma (cat. no. AB3786) | AB_91588 | 1:200 |

| SOX9 | Goat | Polyclonal | R&D Systems (cat. no. AF3075-SP) | — | 1:200 |

| SPB | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Seven Hills Bioreagents (cat. no. WRAB-48604) | — | 1:500 |

| NKX2.1 | Rabbit | Polyclonal | Seven Hills Bioreagents (cat. no. WRAB-1231) | AB_2832953 | 1:200 |

| ZEB1 | Rabbit | EPR17375 | Abcam (cat. no. ab203829) | — | 1:50 |

| Name | Host species | Conjugate | Manufacturer and cat. no. | RRID | Dilution factor |

| Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A21202) | AB_141607 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A32814) | AB_2762838 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 488j | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A21206) | AB_2535792 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Rat IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A21208) | AB_141709 | 1:200 |

| Anti-mouse IgM Heavy Chain | Goat | AF- 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A21042) | AB_141357 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A31570) | AB_2536180 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A32816) | AB_2762839 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 555 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A31572) | AB_162543 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A31571) | AB_162542 | 1:200 |

| Anti-Goat IgG (H+L) | Donkey | AF- 647 | Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. A21447) | AB_141844 | 1:200 |

Fig. 6 |. RT–qPCR analysis of the core and tip areas of a lung organoid.

a, Upper image shows the morphology of organoids before isolation of core (dashed area) and tips. Bottom image shows the punched out core (left) and tip (right) of an organoid. b, RT–qPCR for select lung and non-lung endoderm markers in the centers relative to the periphery of the organoids (n = 3 independent experiments at ~d60, two-way ANOVA).

Table 2 |.

Primers

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| CAPN14 | GCCATGCCTATACTCTCACAG | CTCCAGTCTCCTTTCCATTCC |

| CDX2 | GCCAAGTGAAAACCAGGACG | CAGAGAGCCCCAGCGTG |

| GAPDH | AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG | ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA |

| GATA4 | CTCAGAAGGCAGAGAGTGTGT | CGGGAGGCGGACAGC |

| HHEX | GCGAGAGACAGGTCAAAACC | TTATTGCTTTGAGGGTTCTCCT |

| HNF6 | GAGGATGTGGAAGTGGCTG | ACATCTGTGAAGACCAACCTG |

| HNF1B | CAGTCGGTTTTACAGCAAGTC | TGGATATTCGTCAAGGTGCTG |

| MNX1 | GCACCAGTTCAAGCTCAAC | GCTGCGTTTCCATTTCATCC |

| MUC13 | AGGAAGATGCTAATGGGAACTG | GAATGACAATGCCAGCGATG |

| PDX1 | ATGAACGGCGAGGAGCAGTA | TGGGTCCTTGTAAAGCTGCG |

| PROX | AACATGCACTACAATAAAGCAAATGA | CAGGAATCTCTCTGGAACCTCAAA |

Box 2 |. Preparation of single-cell suspensions for scRNAseq or flow cytometry ● Timing 1.5 h (hands on, 30 min).

Reagents

Cell recovery reagent (Corning, cat. no. 354253)

BSA fraction V (7.5%) (Gibco, cat. no. 15260–037

IMDM (Gibco, cat. no. 12440–053)

Dead cell removal kit (Miltenyi Biotec, cat. no. 130–090-101)

Disposables

24-Well insert (Falcon, cat. no. 353095)

24-Well plate (Falcon, cat. no. 353047)

15 ml centrifuge tube (Thermo Scientific, cat. no. 339650)

Equipment

Centrifuge 5810 R (Eppendorf)

Forceps (Dumont, cat. no. 11251–33)

Reagent setup

Base medium: to make 100 ml of base medium, add 0.53 ml of 7.5% BSA to 99.47 ml of IMDM (final concentration of BSA 0.04% vol/vol). Sterile filter through a 0.22 μm filter. Store at 4 °C for 1 month.

Procedure

Remove the insert from the 24-well plate, invert it and gently peel off the membrane from the bottom of the insert using forceps.

Carefully place the insert with the membrane removed over the mouth of an open, empty 15 ml centrifuge tube.

Add 1 ml of cell recovery reagent to the insert such that the embedded organoid with Matrigel falls into the 15 ml centrifuge tube.

Close the 15 ml centrifuge tube and immediately place on ice to depolymerize the Matrigel.

Every 20 min, gently shake the tube to check if the Matrigel has dissolved and place it back on ice.

Once the Matrigel has dissolved, add 10 ml of wash medium to the tube. Time varies from ~45 min to 1 h depending on Matrigel thickness.

Centrifuge at 200g for 5 min.

-

Aspirate the wash medium and cell recovery reagent and add 1 ml of Accutase to the organoid and incubate at 37 °C.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Avoid using trypsin to dissociate the organoid as it is too harsh and the chances of losing fragile cell types is higher.

Gently shake the tube to disturb/dissociate the organoid every 5 min and replace the tube at 37 °C for 10–12 min. Time varies depending on the organoid size and density.

When the organoid is dissociated add 10 ml wash medium and centrifuge at 400g for 4 min.

-

Aspirate the wash medium and resuspend the pellet in base medium.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Check the base medium compatibility with the sequencing technology to be used for scRNAseq.

Remove dead cells from the cell suspension by using the MiltenyiBiotec dead cell removal kit.

-

Dilute the cell suspension to a concentration of 5,000 cells/μl for sequencing. For sequencing and analysis of scRNAseq data, see Box 3.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Cell suspension dilution varies depending on the sequencing vendor requirements.

Box 3. scRNAseq | analysis.

For our scRNAseq analysis (see ‘Anticipated results’ and Figs. 7 and 8) libraries were prepared and sequenced at the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center High-Throughput Screening Center at Columbia University. Sequencing libraries were prepared using 10x Genomics Single Cell Gene Expression 3′ workflow and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000. FASTQ files were processed using cell ranger version 5.0.1 for each sample and the reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome.

Data were analyzed using the standardized Seurat pipeline V4 in R65 and reciprocal principal component analysis-based integration (https://satijalab.org/seurat/articles/integration_rpca.html). The steps involved in the analysis include: quality control analysis, normalization, integration of samples, dimensionality reduction, clustering and visualization of the data65. To begin, the Cell Ranger output count matrix was read into R and a Seurat object was created for each individual dataset. The four datasets were merged into one dataset and filtered on the basis of the number of unique molecular identifiers (nUMI ≥500), number of genes (nGenes ≥250) and mitochondrial abundance (<20%) for further analysis. Following filtering, the datasets were split and to account for batch effects, sequencing depth and to remove technical variability, normalization and variance stabilization was performed using the SCTransform (SCT) function in Seurat66. Cell cycle scoring and mitochondrial abundance was calculated and regressed out along with the normalization process using SCTransform.

Integration is based identification of common features in different datasets that serves as anchors across these datasets, such that batch effects are attenuated65. Merged analysis uses the processed data, but does correct those based on common anchors, and therefore does not correct for batch effects. However, as integration may be prone to overcorrection if differences in cellular composition between samples are large67, as may be these case in the organoids described here at different time points, we present both integrated (Fig. 7) and merged (Fig. 8) analyses. Features to use when integrating the datasets were chosen using SelectIntegrationFeatures function. Principal component analysis for each dataset was done individually before identifying integration anchors. We then set the normalization method to ‘SCT’ and the reduction to robust principal component analysis while using the FindIntegrationAnchors function. The datasets were integrated using the integration anchors identified using IntegrateData function. Principal component analysis was used to identify the number of dimensions (nDims) for dimensionality reduction of the integrated dataset and visualization was performed using RunPCA. nDims was used to compute the shared nearest neighbor graphs using the k-nearest neighbor algorithm, to find relevant clusters and UMAP for visualization of the clusters was performed using RunUMAP function. Clusters were created with resolutions ranging from 0.4 to 0.8. We visualized and analyzed the different clusters on the basis of marker identification using FeaturePlot and found 0.4 resolution to produce the most biologically informative clusters for our study. We performed pseudotime analysis using scVelo63 on the merged datasets.

Fig. 7 |. Integrated scRNAseq analysis.

a, UMAP clusters after integrated analysis of organoids collected at d25, d40, d60 and d80. b, Dot plots of dynamic expression of endodermal (FOXA1), lung (NKX2.1, CPM), distal lung (SFTPB, NAPSA, SLC34A2, LPCAT), distal airway (SCGB3A2), mid and hindgut (GATA4, CDX2), mesenchymal (THY1, COL1A2, ZEB1, TBX4, WNT2B), proliferating cell (Ki67) and housekeeping genes (ACTA2) genes over time. c, UMAP feature plots of genes shown in b.

Fig. 8 |. Merged scRNAseq analysis.

a, UMAP clusters after merged (as opposed to integrated) analysis of organoids collected at d25, d40, d60 and d80, showing expression of each marker on top of each graph. Clusters corresponding to each timepoint are shown in the upper left plot. b, scVelo trajectory analysis. Clusters are identified by colors. Pseudotime analysis was performed using scVelo on the merged datasets63,64.

Expertise needed to implement the protocol

Any scientist with experience in cell culture can apply this protocol. The required equipment, except for the low-oxygen incubator and the picking hood, is standard to most cell culture facilities, and reagents can be purchased from standard scientific vendors.

Materials

Biological materials

hPSCs: this protocol was developed and optimized for differentiation of RUES2 human ESCs (Rockefeller University Embryonic Stem Cell Line 2, National Institutes of Health (NIH) approval number NIHhESC-09-0013, registration number 0013; RRID: CVCL_B810, passages 17–28) and has also been shown to work with two iPSC lines generated using Sendai Virus and modified messenger RNA from human dermal fibroblasts (purchased from Mount Sinai Stem Cell Core facility, passages 17–26). We anticipate that this protocol could also be applied to other hESC and hiPSC lines, although some optimization might be required. This optimization is primarily geared at optimal DE induction as evaluated by flow cytometry for expression of EPCAM, CXCR4 and cKIT (see Steps 28–66) and may require adjusting density of hPSCs and feeders, as well as duration of DE induction (typically ranging from 72 to 96 h) ! CAUTION Research involving human ESCs must comply with state, institutional and funding agency regulations. An approval from the Human Embryonic and Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Committee at the investigator’s home institute is usually required. We obtained approval from the Columbia University Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight committee (H.-W.S.) and Mount Sinai Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight committee (Y.-W.C.). ! CAUTION Karyotyping is required every 6 months. ! CAUTION The cell lines used in your research should be regularly checked to ensure they are authentic and are not infected with mycoplasma.

Pre-irradiated MEFs (GlobalStem, cat. no. GSC-6201G, RRID: CVCL_RB05) ! CAUTION Lot test recommended for best endoderm induction.

Reagents

Growth factors and small molecules

Recombinant Human/Mouse/Rat Activin A protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 338-AC) ▲ CRITICAL Lot test needed for best DE induction.

RA (Tocris, cat. no. 0695) ! CAUTION Light sensitive.

Recombinant Human BMP4 protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 314-BP)

CHIR 99021 (Tocris, cat. no. 4423)

Recombinant Human FGF10 protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 345-FG)

Recombinant Human FGF2 protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 233-FB)

Recombinant Human KGF/FGF7 protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 251-KG)

IWP 2 (Tocris, cat. no. 3533)

Recombinant Human Noggin protein (R&D Systems, cat. no. 6057-NG)

SB 431542 (Tocris, cat. no. 1614)

Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Tocris, cat. no. 1254)

Medium and supplements

Bovine albumin fraction V (BSA) (7.5% solution, Gibco, cat. no. 15260037)

l-Ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A4544)

B27 (Gibco, cat. no. 17504044) ▲ CRITICAL Lot test needed for best DE induction.

N2 (Gibco, cat. no. 17502048) ▲ CRITICAL Lot test needed for best DE induction.

β-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M6250)

GlutaMAX (Gibco, cat. no. 35050061)

Knockout serum replacement (Gibco, cat. no. 10828028) MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution (Gibco, cat. no. 11140050) ▲ CRITICAL Lot test needed for best DE induction.

Monothioglycerol (MTG) (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. M6145)

Penicillin–streptomycin (10,000 U/ml) (Gibco, cat. no. 15140122)

Primocin (InvivoGen, cat. no. ant-pm-2)

Stem cell qualified FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, cat. no. S10250)

Human fibronectin protein, CF (R&D Systems, cat. no. 1918-FN)

Growth factor reduced Matrigel (Corning, cat. no. 354230) or Cultrex 3-D Matrix RFG basement membrane extract (R&D System, cat. no. 344501001)

Ham’s F12 (Cellgro, cat. no. 10-080-CV)

Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, Cellgro, cat. no. 10-016-CV)

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and Ham’s F12, 50/50 mix (Cellgro, cat. no. 10-092-CV)

Gelatin from bovine skin (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. G9391)

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Cellgro, cat. no. MT21031CM)

Cell culture grade water (Corning, cat. no. 25-055-CVC)

Enzymes

0.05% Trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Gibco, cat. no. 25300120)

Accutase/EDTA (Innovative Cell Technologies, cat. no. AT104)

Dispase (Corning, cat. no. 354235)

Other reagents

cKIT-PE antibody (BioLegend, cat. no. 313204)

CXCR4-APC antibody (BioLegend, cat. no. 306510)

CD184 (CXCR4) MicroBead Kit, human (Miltenyi Biotec, cat. no. 130–100–070)

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Fisher, cat. no. BP231-100)

Equipment

10 cm2 tissue-culture dish (BD Falcon, cat. no. 353003)

15 ml conical tube (BD Falcon, cat. no. 352097)

50 ml conical tube (BD Falcon, cat. no. 352098)

Posi-Click 1.7 ml microcentrifuge tube (Denville, cat. no. C2170)

24-Well transwell insert (BD Falcon, cat. no. 8770) ▲ CRITICAL Inserts from BD Falcon hold more medium in the inserts than other brands tested. This will result in better organoid morphology.

24-Well flat-bottom tissue culture-treated plate (Falcon, cat. no. 353047)

24-Well flat-bottom not treated cell culture plate (Falcon, cat. no. 351147)

Six-well ultralow-attachment plate (Costar, cat. no. 3471)

Six-well flat-bottom tissue culture-treated plate (Falcon, cat. no. 353046)

96-Well U-bottom non-tissue culture-treated plate (Corning, cat. no. 351177)

P10 barrier tips (Denville Scientific, cat. no. P1096-FR)

P20 barrier tips (Denville Scientific, cat. no. P1121)

P200 barrier tips (Denville Scientific, cat. no. P1122)

P1000 barrier tips (Denville Scientific, cat. no. P1126)

Serological pipets, individually wrapped, 5 ml (Fisher, cat. no. 13-678-11D)

Serological pipets, individually wrapped, 10 ml (Fisher, cat. no. 13-678-11E)

Serological pipets, individually wrapped, 25 ml (Fisher, cat. no. 13-678-11)

Disposable sterile bottle-top filters (Corning, cat. no. 431118)

Disposable sterile bottles, 250 ml (Corning, cat. no. 430281)

Disposable sterile bottles, 500 ml (Corning, cat. no. 430282)

Disposable sterile bottles, 1,000 ml (Corning, cat. no. 430518)

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) tube (BD Falcon, 352008 or Corning, cat. no. 352008)

Round-bottom polystyrene test tubes with cell strainer snap cap (BD Falcon, cat. no. 352235 or Corning, cat. no. 352235)

Tissue culture hood

Normoxic incubator (95% air/5% CO2/37 °C)

Hypoxic incubator (5% O2/5% CO2/37 °C)

Centrifuge

Hemocytometer

Picking hood

Microscopes: dissecting microscope: Nikon SMZ1500; laser scanning confocal microscope: Leica TCS SP8 Stellaris (40× oil immersion objective); Leica DMi1 Inverted Phase Contrast Microscope (Hi Plan 4×, Phase Contrast Hi Plan 10× Ph1 and 20× Ph1) ▲ CRITICAL Similar microscopes from other manufacturers can be used.

Pipettes

Pipet aid

FlowJo flow cytometry software (https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo (RRID: SCR_008520))

Reagent setup

Growth factors and small molecules

FGF2

Reconstitute at 20 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 100 μl to 500 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

FGF10

Reconstitute at 10 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 500 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

FGF7

Reconstitute at 10 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 500 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

BMP4

Reconstitute at 10 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 500 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

CHIR 99021

Reconstitute at 3 mM in DMSO. Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 6 months.

All-trans RA

Reconstitute at 50 μM in DMSO. Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

IWP2

Reconstitute at 1 mM in DMSO. Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 6 months.

Noggin

Reconstitute at 100 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

SB431542

Reconstitute at 10 mM in DMSO. Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 6 months.

Y-27632

Reconstitute at 10 mM in DMSO. Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 6 months.

Activin A

Reconstitute at 100 μg/ml in sterile 0.1% BSA/DPBS (wt/vol). Aliquot 100 μl in microcentrifuge tubes. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months.

Gelatin

Prepare a 0.1% (wt/vol) solution by dissolving gelatin in tissue culture grade water. Heat the gelatin solution to boiling for 5–10 min. After cooling down, filter the gelatin solution through a 0.22 μm filter to make it sterile. The gelatin solution can be kept at 4 °C for up to 3 months.

Fibronectin

Make 100 μl aliquots and store them at 4 °C for up to 6 months.

l-Ascorbic acid

Reconstitute at 50 mg/ml in sterile cell culture grade water (wt/vol). Filter the solution through a 0.22 μm filter to make it sterile. Make 100 μl aliquots and store at −20 °C to −70 °C for up to 3 months. ! CAUTION Discard unused solution. Always use a freshly thawed aliquot for culture.

Media

MEF medium

Make 500 ml MEF medium by combining the reagents as detailed in the table below. Sterilize by filtering through a 0.22 μm filter. MEF medium can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 month.

| Reagent to add | Stock concentration | Volume to add | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMDM | 415 ml | ||

| Stem cell-qualified FBS | 75 ml | 15% | |

| MTG | 11.5 M | 20 μl | 0.46 mM |

| GlutaMAX | 100× | 5 ml | 1× |

| Penicillin–streptomycin | 100× | 5 ml | 1× |

Stop medium

Make 500 ml Stop medium by combining reagents as detailed in the table below. Sterilize by filtering through a 0.22 μm filter. Stop medium can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 month.

| Reagent to add | Stock concentration | Volume to add | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMDM | 465 ml | ||

| FBS | 25 ml | 5% | |

| GlutaMAX | 100× | 5 ml | 1× |

| Penicillin–streptomycin | 100× | 5 ml | 1× |

hPSC maintenance medium

Make 500 ml of hPSC maintenance medium by combining reagents as detailed in the table below. Sterilize by filtering through a 0.22 μm filter. hPSC maintenance medium can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 month. ▲ CRITICAL Supplement FGF2 to a final concentration of 20 ng/ml right before use.

| Reagent to add | Stock concentration | Volume to add | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 | 389 ml | ||

| Knockout serum | 100 ml | 20% | |

| MEM-nonessential amino acids | 5 ml | ||

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 14.3 M | 3.5 μl | 0.1 mM |

| Primocin | 50 mg/ml | 1 ml | 100 μg/ml |

| GlutaMAX | 5 ml | ||

| Supplement with FGF2 before use | |||

| FGF2 | 10 μg/ml | 2 μl | 20 ng/ml |

Serum-free differentiation (SFD) medium

Make 1,000 ml of SFD medium by combining reagents as detailed in the table below. Sterilize by filtering through a 0.22 μm filter. SFD medium can be store at 4 °C for up to 1 month. On the day of use, supplement SFD medium with L-ascorbic acid and MTG to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml (1 μl/ml) and 0.45 mM (0.039 μl/ml), respectively, to make complete SFD medium.

| Reagent to add | Stock concentration | Volume to add | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMDM | 725 ml | ||

| Ham’s F12 | 242.5 ml | ||

| N2 | 5 ml | ||

| B27 | 10 ml | ||

| 7.5% BSA | 7.5% | 7.5 ml | |

| Penicillin–streptomycin | 100× | 10 ml | 1× |

| To make complete SFD medium, add the following to SFD | |||

| Reagent to add | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

| GlutaMAX | 100× | 10 μl | 1× |

| Ascorbic acid | 50 mg/ml | 1 μl | 50 μg/ml |

| MTG | 11.5M | 0.039 μl | 0.45 mM |

EB/PS medium

Make 12 ml of EB/PS medium, sufficient for a six-well plate, by adding reagents as detailed in the table below to complete SFD medium. Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

| Complete SFD medium supplemented with | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-27632 | 10 mM | 1 μl | 10 μM |

| BMP4 | 10 μg/ml | 0.3 μl | 3 ng/ml |

Endoderm induction medium

Make 13 ml of endoderm induction medium, sufficient for a six-well plate, by adding reagents as detailed in the table below to complete SFD medium. Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

| Complete SFD medium supplemented with | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y-27632 | 10 mM | 1 μl | 10 μM |

| BMP4 | 10 μg/ml | 0.05 μl | 0.5 ng/ml |

| FGF2 | 10 μg/ml | 0.25 μl | 2.5 ng/ml |

| Activin A | 100 μg/ml | 1 μl | 100 ng/ml |

Anteriorization medium-1

Make 13 ml of anteriorization medium-1, sufficient for a six-well plate, by adding reagents as detailed in the table below to complete SFD medium. Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

| Complete SFD medium supplemented with | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noggin | 100 μg/ml | 1 μl | 100 ng/ml |

| SB431542 | 10 mM | 1 μl | 10 μM |

Anteriorization medium-2

Make 12 ml of anteriorization medium-2, sufficient for a six-well plate, by supplementing reagents as detailed in the table below to complete SFD medium. Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

| Complete SFD medium supplemented with | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| SB431542 | 10 mM | 1 μl | 10 μM |

| IWP2 | 1 mM | 1 μl | 1 μM |

Ventralization/branching medium

Make 12 ml of ventralization/branching medium, sufficient for a six-well plate, by adding reagents as detailed in the table below to complete SFD medium. The prepared medium can be stored at 4 °C up to 3 d.

| Complete SFD medium supplemented with | Stock concentration | Volume to add per ml | Final concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | 3 mM | 1 μl | 3 μM |

| FGF10 | 10 μg/ml | 1 μl | 10 ng/ml |

| FGF7 (KGF) | 10 μg/ml | 1 μl | 10 ng/ml |

| BMP4 | 10 μg/ml | 1 μl | 10 ng/ml |

| All-trans RA | 0.5 mM | 0.1 μl | 50 nM |

Plating irradiated MEFs for hPSC culture

Precoat six-well flat bottom tissue culture-treated plates with 2 ml 0.1% gelatin made with cell culture grade water for 15 min at room temperature (20–25 °C). Thaw a frozen vial of pre-irradiated MEFs containing ~2 × 106 cells in a water bath at 37 °C. Add the thawed MEFs to 10 ml wash medium and centrifuge at 400g for 4 min. Aspirate the wash medium and add 1 ml of MEF medium. Count the MEFs and seed at a density of 17,000–25,000 cells/cm2 in 2 ml of MEF media in a normoxic incubator overnight. The irradiated MEFs should be plated 1 d before plating of hPSCs to allow attachment and spreading of the MEFs producing sufficient extracellular matrix to prevent premature differentiation.

hPSC culture

Maintain hPSCs on irradiated MEFs. Culture cells in hPSC maintenance medium. Change medium daily. Passage hPSCs with Accutase/EDTA and replate at a dilution of 1:48. Maintain cultures in a humidified normoxic incubator. Further details covering how to properly maintain an hPSC culture can be found in ‘ES Cell International Pte Ltd: Methodology Manual Human Embryonic Stem Cell Culture 2005’ and ‘Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) StemBook Protocols for pluripotent cells, URL: http://www.stembook.org/protocols/pluripotent-cells’ and in our previously published protocols57,61. Lines are karyotyped and verified for mycoplasma contamination using PCR every 6 months.

Thawing and aliquoting Matrigel

Thaw growth factor-reduced Matrigel on ice at 4 °C overnight. For aliquots used for organoid embedding, prechill Posi-Click 1.7 ml microcentrifuge tubes on ice for 15 min and aliquot 0.5 ml of thawed Matrigel to each tube on ice. For aliquots used for coating of culture plates, prechill 15 ml conical tubes on ice for 15 min and aliquot 1 ml of thawed Matrigel to each tube on ice. Aliquots can be stored at −20 °C for up to 6 months. CRITICAL Keep all parts contacting Matrigel cold to avoid polymerization.

Coating dishes with Matrigel for MEF depletion

Thaw 1 ml Matrigel and add to 29 ml of cold IMDM to a 50 ml prechilled conical tube to obtain a final concentration of 3.3% (vol/vol) and keep on ice. Make sure the diluted Matrigel is mixed well. Immediately transfer the 10 ml diluted Matrigel/IMDM solution to the 10 cm2 tissue culture dish. Matrigel-coated dishes can be used after 3 h of incubation at room temperature or stored at 4 °C for up to 2 weeks. Keep the dishes flat in the refrigerator and avoid drying out of the Matrigel coating solution.

Fibronectin plates

Prepare fibronectin-coated six-well plates by diluting fibronectin to 4 μg/ml in DPBS. Add 2 ml fibronectin/DPBS solution to each well and incubate the plates in a normoxic incubator for at least 30 min or 4 °C overnight. Make sure the fibronectin coating covers the entire plate (~12 ml of a six-well plate).

Procedure

▲ CRITICAL The following procedures describe how to generate one six-well plate EBs from hPSCs.

MEF depletion on Matrigel (d1) ● Timing 18–24 h (hands on, 20 min)

-

1

Prepare one Matrigel-coated dish as described in ‘Reagent setup.’

-

2

Dissociate two wells of hPSCs (from a six-well plate, 90–95% confluent, corresponding to 5–7 × 106 cells; see ‘Reagent setup’) by aspirating the hPSC maintenance medium from the wells, followed by adding 1 ml per well Accutase and incubate in a normoxic incubator for 2–3 min.

-

3

Verify under a microscope that MEFs have detached from the plate, then aspirate the Accutase.

-

4

Neutralize the enzyme by adding 2 ml Stop medium to each well.

-

5

Gently flush the cells off the well by pipetting up and down.

-

6

Transfer the cell mixture to a 15 ml conical tube.

-

7

Pellet the dissociated cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

8

Aspirate as much of the supernatant containing enzyme and Stop medium as possible.

-

9

Resuspend the cells with 10–12 ml hPSC maintenance medium.

-

10

Aspirate the Matrigel-coating solution from the dish (from Step 1).

-

11

Plate the cells in the Matrigel-coated dish.

-

12

Gently rock the dish with a side-to-side motion a few times to ensure the cells are evenly distributed.

-

13

Incubate the cells in a normoxic incubator overnight.

Embryoid body formation/primitive streak induction (d0) ● Timing 12–16 h (hands on, 15 min)

-

14

On d0, prepare the EB/PS medium as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

-

15

Remove the hPSC maintenance medium from the Matrigel-coated dish.

-

16

Add 3 ml of cold (4 °C) trypsin/EDTA to the dish.

-

17

Incubate the dish for 1–1.5 min in a normoxic incubator.

-

18

Aspirate the trypsin/EDTA solution.

-

19

Neutralize the enzymes by adding 10 ml wash medium.

-

20

Gently flush the cells off the dish by pipetting up and down using a 10 ml serological pipet.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

21

Transfer the cell mixture to a 15 ml conical tube.

-

22

Pellet the dissociated cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

23

Aspirate as much of the supernatant containing enzyme and Stop medium as possible.

-

24

Resuspend the cells with 12.5 ml EB/PS medium.

-

25

Distribute 2 ml per well of the cell mixture to a six-well ultralow-attachment plate.

-

26

Gently rock the plate with a side-to-side motion a few times to ensure even distribution of cells and avoid aggregation of cells before placing the plate back in an incubator.

-

27

Place the ultralow-attachment plate in a hypoxic incubator for 12–16 h to allow EB formation.

Endoderm induction (d1-4) ● Timing ~3 d (hands on, 20 min)

-

28

Prepare the endoderm induction medium as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

-

29

After 12–16 h of EB formation, gently collect all EBs from the ultralow-attachment plate to a 15 ml conical tube.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

30

After EB collection, add 1 ml per well of the endoderm induction medium to the ultralow-attachment plate that previously contained the EBs.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Endoderm induction medium is added to the empty wells to prevent them from drying out, which promotes cellular attachment.

-

31

Allow the EBs to settle down for 5 min or centrifuge the conical tube at 130g for 1 min to pellet down the EBs.

-

32

Aspirate the EB/PS medium.

-

33

Gently resuspend the EBs with 6.5 ml endoderm induction medium using a 5 ml serological pipet.

-

34

Distribute them 1 ml per well of the EB mixture equally back to the low-attachment plate.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Only take 1ml of the EB mixture each time. Gently resuspend the EBs each time before taking the EB mixture for each well to ensure similar EB numbers are distributed to each well.

-

35

Rock the plate with a side-to-side motion to ensure that EBs are evenly distributed.

-

36

Return the plate to a 5% CO2/5% O2 incubator.

-

37

On d2, add 1 ml fresh Endoderm induction medium to each well (in total 3 ml per well).

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

-

38

Rock the plate with a side-to-side motion to ensure that EBs are evenly distributed.

-

39

Return the plate to a 5% CO2/5% O2 incubator.

-

40

On d3, add 2 ml fresh Endoderm induction medium to each well (in total: 5 ml medium per well).

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

-

41

Rock the plate in a side-to-side motion to ensure that EBs are evenly distributed.

-

42

Return the plate to a 5% CO2/5% O2 incubator.

DE yield examination (d4.1-4.3) ● Timing hands on, 1.5 h

▲ CRITICAL On d4.1-4.3 (74.5–79.5 h after exposure of EBs to Activin A), verify DE yield by flow cytometric analysis of CXCR4 and cKIT expression. Always verify the DE yield is >90% before continuing to the anteriorization stage. Different hPSC lines might have different optimal DE induction times.

-

43

Prepare 25 ml of complete SFD medium as described in the ‘Reagent setup’.

-

44

Swirl the plate slowly to make the EBs concentrate in the middle of the wells.

-

45

Gently collect half of a single well of EBs (EBs are typically concentrated in the middle of the well) to a 15 ml conical tube by a P1000 pipette. Return the plates (containing 5.5 wells of EBs) back to a hypoxic incubator until later use.

-

46

Allow the collected EBs to settle down for 5 min or centrifuge the conical tube at 130g for 1 min to pellet down the EBs.

-

47

Aspirate the medium.

-

48

Add 1 ml of cold trypsin/EDTA to the conical tube.

-

49

Gently tap the tube to swirl the EBs in the trypsin/EDTA solution.

▲ CRITICAL STEP EBs with good endoderm yield usually start to dissociate after 2–2.5 min. Do not digest the EBs for more than 4 min.

-

50

When EBs are completely dissociated (no visible clumps) or after 4 min, neutralize the enzymes with 10 ml stop medium.

-

51

Take 25 μl of cell mixture and mix with Trypan Blue, then count the cell number using a hemocytometer.

-

52

Pellet the dissociated cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

53

Aspirate the Stop medium.

-

54

Resuspend the cells in complete SFD medium on the basis of the cell counts: 100 μl of complete SFD medium per million cells.

-

55

Add CXCR4 (1:100) and cKIT (1:100) antibodies that have been verified to be suitable for flow cytometric analysis.

-

56

Stain the cells on the basis of the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend, for example, in this protocol).

-

57

After the staining procedure is done, add 5–10 ml of complete SFD medium to the conical tube.

-

58

Pellet down the dissociated cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

59

Aspirate the supernatant.

-

60

Resuspend the cells in 500 μl of complete SFD medium.

-

61

Filter the cell mixture through a cell strainer cap (mesh size: 35 μm) attached to a FACS tube.

-

62

Add 4 ml of complete SFD medium to the FACS tube.

-

63

Pellet down the filtered cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

64

Aspirate the supernatant.

-

65

Resuspend the cells in 300 μl of complete SFD medium.

-

66

Determine the endoderm yield by determining the CXCR4 and cKIT double positive population via a flow cytometric analyzer. Continue differentiation only with EBs that have an endoderm yield that is >90%.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Anteriorization (d5-6) ● Timing ~2 d (hands on, 2 h)

-

67

Prepare fibronectin-coated six-well plates as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

-

68

Prepare 15 ml of complete SFD medium as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

-

69

Prepare 50 ml of Anteriorization medium-1 as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

-

70

Swirl the ultralow-attachment plate of EBs (from Step 45) slowly to make the EBs concentrate in the middle of the wells.

-

71

Gently collect all the remaining EBs from the plate and pool in a 15 ml conical tube by a P1000 pipette.

-

72

Allow the EBs to settle down for 5 min or centrifuge the conical tube at 130g for 1 min to pellet down the EBs.

-

73

Aspirate the medium.

-

74

Dissociate the EBs into single cells with 3 ml of trypsin.

-

75

Gently tap the tube to swirl the EBs in the trypsin/EDTA solution.

-

76

Neutralize the enzymes with 10 ml Stop medium.

-

77

Pellet the dissociated cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

78

Aspirate the Stop medium.

-

79

Resuspend the cells in 10 ml of complete SFD medium.

-

80

Take 25 μl of cell mixture and mix with Trypan Blue and count the cell number using a hemocytometer.

-

81

Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 400g for 4 min.

-

82

Aspirate the complete SFD medium.

-

83

Resuspend the cells in Anteriorization medium-1 (7.5 × 105 cells per 2 ml of Anteriorization medium-1).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

84

Add 2 ml of cell mixture to each well of the fibronectin-coated six-well plate (from Step 67).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

85

Rock the plate in a side-to-side motion to ensure that cells are evenly distributed.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

86

Return the plate to a normoxic incubator.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

87

On d6, after 24 h (±2 h) after adding the Anteriorization medium-1, prepare an appropriate amount of the Anteriorization medium-2 (2 ml per well) as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

88

Aspirate Anteriorization medium-1 and replace with Anteriorization medium-2.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

89

Return the plates to a normoxic incubator.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Ventralization and LBO formation (d6-20/25) ● Timing ~14–20 d (hands on, 30 min)

-

90

On d6, 24 h (± 2 h) after adding the Anteriorization medium-2, prepare an appropriate amount of the ventralization medium/branching medium (2 ml per well) as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Prepare the medium fresh on the day of use.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

91

Replace the Anteriorization medium-2 with ventralization medium/branching medium (2 ml per well).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

92

Return the plates to a normoxic incubator.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

93

On d8, 48 h later, prepare an appropriate amount of the ventralization medium/branching medium (2 ml per well) as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

94

Aspirate all the old ventralization medium/branching medium and add 2 ml fresh ventralization medium/branching medium to each well.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

95

Suspend the organoids by gently pipetting up and down with P1000 tips.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

96

Transfer the suspended organoids to six-well ultralow-attachment plates (one well to one well).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

97

Rock the plate with a side-to-side motion to ensure that cells are evenly distributed.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

98

Return the plate to a normoxic incubator.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

99

On d10, feed the organoids by tilting the plate and allowing the organoids to sink to the bottom edge. Remove the old medium while avoiding touching the organoids. Add 2 ml freshly prepared ventralization medium/branching medium to each well. Feed the organoids with freshly prepared medium on the day of use every other day.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

Branching organoid (d20/25–end of experiment) ● Timing ~25–150 d (hands on, 2 h)

-

100

Examine organoids daily under a microscope between d20 and d25. When the desired stage is reached, proceed with embedding.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

101

One night before embedding, thaw the desired amount of Matrigel (150 μl/insert) as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Keep Matrigel on ice during the entire procedure to avoid polymerization.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

102

On the day of use, prepare 50 ml of the ventralization medium/branching medium as described in ‘Reagent setup’.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

103

Add 100 μl per well of the ventralization medium/branching medium to a 96-well U-bottom non-tissue culture-treated plate.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

104

Select the organoids with folding structures under a microscope in a picking hood. One six-well plate should contain hundreds to thousands of organoids. Organoids with folding epithelial structures will gradually form and the majority should adopt this morphology after d15 (Figs. 1b, vi and 3b).

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

105

Typically, one to four organoids will go on to be plated in each 24-well insert. First, put this desired number of organoids per insert into each well of a 96-well U-bottom non-tissue culture-treated plate and set aside.

CRITICAL STEP Putting too many organoids in the same insert will inhibit their growth in the long run.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

106

Place 24-well inserts into non-tissue culture-treated plates.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

107

Layer 50 μl of 100% cold Matrigel into the bottom of each insert.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The Matrigel should be distributed evenly to cover the entire surface of the insert. If not, tap the plate to spread the Matrigel before it polymerizes.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

108

Wait 5 min or until the Matrigel has solidified.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

109

Gently remove as much of the ventralization medium/branching medium as possible from the 96-well plate (from Step 105), one well at a time.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

110

Use a P1000 tip to quickly take ~30–50 μl of 100% cold Matrigel.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

111

Mix the organoids with the cold Matrigel gently to avoid creating bubbles.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

112

Pick up the organoids and immediately but slowly put the organoid–Matrigel mixture in the center of an insert.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

113

Wait 5 min for the Matrigel to solidify to secure the organoids in the center of the insert.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

114

Add another 50 μl of 100% cold Matrigel to the insert to create a Matrigel sandwich.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

115

Put the plates in a normoxic incubator for 10 min to make sure all Matrigel has solidified.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

116

Add 500 μl/insert of ventralization medium/branching medium to the inserts.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

117

Add another 500 μl per well of ventralization medium/branching medium into the wells.

? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

118

Return the plate to a normoxic incubator.

-

119

Replace the medium every 2–3 d until the cultures reach the desired timepoints of experiments. Medium is replaced both in the insert and in the well. To aspirate medium from the top (insert), tilt the plate so that one can aspirate without disturbing the Matrigel.

-

120

When the desired timepoint is reached, standard analyses can be performed (see Box 1 for RT–qPCR and IF and Boxes 2 and 3 for scRNAseq).

Timing

Steps 1–13, MEF depletion (d1): 18–24 h (hands on, 20 min)

Steps 14–27, EB formation (d0): 12–16 h (hands on, 15 min)

Steps 28–42, DE induction (d1-4): ~3 d (hands on, 20 min)

Steps 43–66, DE yield test (d4.1-4.3): 1.5 h (hands on, 1.5 h)