Abstract

The striatum plays a fundamental role in sensorimotor and cognitive functions of the body, and different sub-regions control different physiological functions. The striatal interneurons play important roles in the striatal function, yet their specific functions are not clearly elucidated so far. The present study aimed to investigate the morphological properties of the GABAergic interneurons expressing neuropeptide Y (NPY), calretinin (Cr), and parvalbumin (Parv) as well as the cholinergic interneurons expressing choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) in the striatal dorsolateral (DL) and ventromedial (VM) regions of rats using immunohistochemistry and Western blot. The present results showed that the somatic size of Cr+ was the smallest, while ChAT+ was the largest among the four types of interneurons. There was no regional difference in neuronal somatic size of all types of interneurons. Cr+ and Parv+ neurons were differentially distributed in the striatum. Moreover, Parv+ had the longest primary dendrites in the DL region, while NPY+ had the longest ones in the VM region of striatum. But there was regional difference in the length of primary dendrites of Parv. The numbers of primary dendrites of Parv+ were the largest in both DL and VM regions of striatum. Both Cr+ and Parv+ primary dendrites displayed regional difference in the striatum. Western blot further confirmed the regional differences in the protein expression level of Cr and Parv. Hence, the present study indicates that GABAergic and cholinergic interneurons might be involved in different physiological functions based on their morphological and distributional diversity in different regions of the rat striatum.

Keywords: Striatum, Neuropeptide Y, Calretinin, Parvalbumin, Choline acetyltransferase

Introduction

The striatum, with massive glutamatergic and dopaminergic inputs from the cerebral cortex and thalamus and midbrain regions, respectively, is one of the most important portions of the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical circuitry (Alexander et al. 1986). Different striatal sub-regions receive inputs from distinct cortical areas and thus, control different physiological functions. Roughly in rodents, the dorsolateral (DL) striatum is a component of sensorimotor circuits, while the ventromedial (VM) striatum participates in associative circuits (Kreitzer and Berke 2011). It has been recently proposed that the DL region of striatum plays an important role in the processes of learning and memory (Packard and Knowlton 2002).

The neuronal composition of striatum is diverse—approximately 95 % of the striatal neurons are the medium-sized spiny projection neurons (MSNs), while the other 5 % are the aspiny interneurons. The striatal interneurons are subdivided into two main groups—the cholinergic interneurons expressing choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and the GABAergic interneurons including the parvalbumin (Parv)+, the calretinin (Cr)+, and the neuropeptide Y (NPY)/nitric oxide synthase (NOS)+ interneurons (Kawaguchi et al. 1995; Tepper and Bolam 2004; Vincent and Johansson 1983). On the basis of the stereological unbiased cell counts of the immunostained striatum in rats, the NPY/NOS+ interneurons account for 0.6 % of the striatal neurons, the Cr+ interneurons account for 0.5 %, and the Parv+ interneurons account for 0.7 % (Luk and Sadikot 2001; Rymar et al. 2004).

Despite the extremely small amount, the striatal interneurons have been proved to play key roles in the basal ganglia information processing. Anatomically, the fast-spiking GABAergic Parv+ interneurons are thought to feed forward cortical influences to MSNs (Fino and Venance 2011), while cholinergic neurons receive dopaminergic input from the substantia nigra and mediate reward signaling. In addition, several studies revealed that the Parv+ interneurons presented notably stronger immunoreactive for the glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) than the MSNs did (Cowan et al. 1990; Kita 1993; Kubota et al. 1993). NPY+ interneurons as a persistent and low threshold spike neuron type receive both cholinergic and dopaminergic inputs and play a crucial role in regulating corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Cr+ neurons exert monosynaptic inhibition on MSNs that can delay or block spiking (Tepper and Bolam 2004). It is very likely that the specific morphological features and different spatial distribution of different types of interneurons may underlie the specific physiological functions of different regions of striatum.

The limited experimental techniques owing to the rarity of striatal interneurons make it rather difficult to further study these cells in vivo or in vitro (Fino and Venance 2011). There are very few studies exploring on the difference of striatal interneurons located in different striatal regions. To advance understanding of the functions of striatal interneuron, the most essential task is to elucidate the morphological properties of striatal interneurons in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. By means of a series of immunohistochemical staining and western blot analysis on striatal tissue of rats, the present study reported the morphological features and diversity of the NPY+, Cr+, Parv+, and ChAT+ interneurons.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Eighteen adult male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 250–350 g (obtained from the Center for Experimental Animals of Sun Yat-sen University) were used in the present study. The experimental procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animals, Sun Yat-sen University (Approval ID: 2010 No. 9) and strictly conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals in Research.

Transcardial Fixation and Sectioning

The rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9 % saline followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde in 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 4 °C). Brains were quickly removed and post-fixed overnight at 4 °C and then sectioned into 40 μm in thickness using a vibratome.

Immunohistochemistry Procedure

Half of the brain sections were treated with 0.3 % H2O2 in 0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature for 30 min, and then were incubated at 4 °C for 36 h in one of the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-NPY (1:3,000, Abcam), rabbit anti-Cr (1:2,000, Millipore), mouse anti-Parv (1:1,000, Sigma), and rabbit anti-ChAT (1:1,000, Millipore). Sections were rinsed and incubated in anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG (both 1:100, Sigma) for 3 h, followed by incubation in homologous PAP complex (1:200, Sigma) at room temperature for 2 h. The peroxidase reaction was performed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, 0.05 % in 0.01 M PB, pH 7.4, Sigma) for 2–8 min. Between each procedure, sections were repeatedly rinsed for three times in 0.01 M phosphate buffer for 5 min. Sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated, cleared with xylene, and covered with neutral balsam. The other half of the sections were double-labeled for NeuN, the marker of neurons (mouse anti-NeuN 1:1,000, Millipore), after being labeled with markers of striatal interneurons for simultaneous visualization of different interneuron types and the whole neuron population, using similar methods described above. Notably, the colorations of these interneuron types were visualized using DAB solution containing 0.04 % nickel ammonium sulfate, and those of NeuN were visualized using a conventional DAB solution only as described above. Therefore, different interneuron types were distinctly labeled black with nickel-intensified DAB, while the NeuN+ neurons were immunolabeled with a brown DAB reaction. Brain sections were examined using an Olympus microscope, recorded with the digital camera, and processed with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software.

Western Blot

Western blot was carried out to detect the level of the marker proteins for each type of interneuron in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. Rats were decapitated after being anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital. The striatum was extracted from the brain and immediately separated into the DL and VM regions, and then stored at −80 °C before use. The striatal tissues were homogenized in a freshly prepared lysis buffer with protease inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 30 min, and the protein concentration was determined using BioRad DC protein assay (BioRad, Laboratories). Samples were separated on an SDS–PAGE gel (10 % gradient gel) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5 % skim milk for 2–4 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with one of the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-NPY (1:6,000, Abcam), rabbit anti-Cr (1:5,000, Millipore), mouse anti-Parv (1:1,000, Sigma), rabbit anti-ChAT (1:2,000, Millipore), and mouse anti-β-actin (1:2,000, Millipore). After washed with TBST for 4 times, membranes were incubated with homologous HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3,000, Amersham Biosciences, GE Healthcare) for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed with TBST for 4 times. Blots were visualized in enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solution (Pierce) for 5 min and exposed to hyperfilms (Kodak) for 1–15 min. Western blots were made in triplicate. The optical density of each labeled band was measured using Quantity One analysis software.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

The quantification was carried out on every twelfth section of the brain containing the striatum (2.5 mm anterior and 3.3 mm posterior to bregma, twelve to thirteen sections per animal for each staining method), and the number as well as length of neurons and dendrites were measured throughout the depth of the section. Quantitative analysis of different types of striatal interneuron was detected in the DL and VM regions of striatum using previous relevant methods (Abercrombie 1946; Ma et al. 2013; Mu et al. 2011), respectively. The border between DL and VM regions of striatum were determined by making a demarcation line between the caudate-putamen complex and nucleus accumbens as previously described (Voorn et al. 2004; Zaborszky et al. 1985). For NPY, Cr, Parv, ChAT, and NeuN immunohistochemical stained sections, the neuron and the primary dendritic numbers were determined and averaged after they had randomly been taken from five nonoverlapping regions (0.01 mm2 for each) sampled within the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. The mean value of the longest diameter and the shortest diameter was measured by a 100-μm length scale in the ocular lens and counted as the soma size of neurons. Likewise, the primary dendritic length was measured by a 100-μm length scale in the ocular lens. The final quantification of different types of striatal interneurons was the average of the numbers acquired from the twelve to thirteen equidistantly sampled sections. All experimental data are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation). Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with SPSS 16.0 software, and p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Morphology and Size of Neuronal Somas of Different Interneuron Types in the DL and VM Regions of Striatum

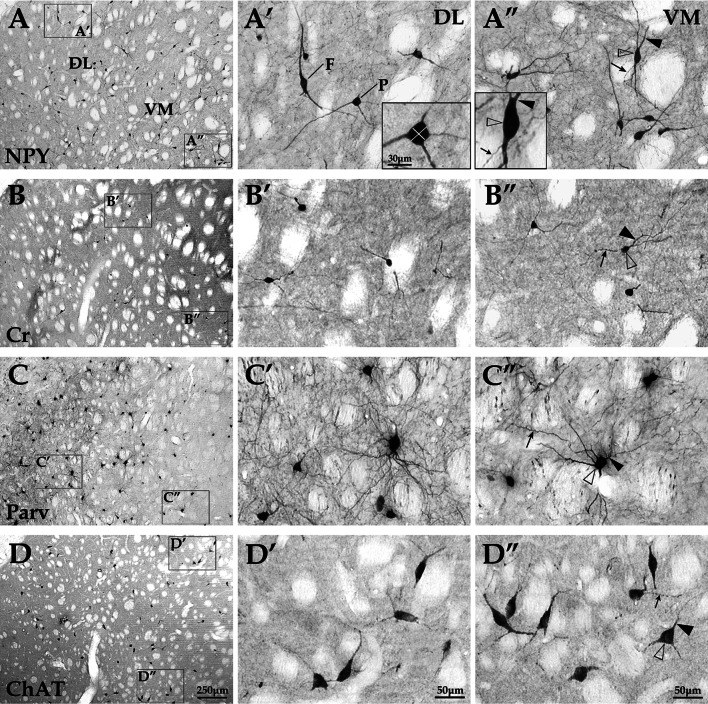

Based on the analysis of brain sections with immunohistochemical staining, the somas of NPY+ interneurons, mostly fusiform or polygonal in shape (Fig. 1a–a″), were medium-sized neurons in the DL and VM regions of striatum (the diameters of somas: 12.52 ± 1.63 μm in DL, 12.72 ± 1.16 μm in VM; Fig. 2). Cr+ interneurons were mainly oval-shaped or triangular (Fig. 1b–b″) with the smallest size (the diameters of somas: 8.72 ± 0.71 μm in DL, 9.22 ± 0.83 μm in VM; Fig. 2) among the four striatal interneuron types. Parv+ interneurons were polygonal or rounded neurons (Fig. 1c–c″), and the diameters of somas were as follows: 13.14 ± 1.46 μm in DL; 11.28 ± 1.24 μm in VM (Fig. 2). Interestingly, in all the brain sections studied here, most of the Parv+ neurons were medium-sized, and a few of them were small-sized. Most of the ChAT+ interneurons were rounded or triangular in shape (Fig. 1d–d″), and were the largest interneurons when compared among different striatal interneuron types of the corresponding regions (F 7,24 = 133.53, F 7,24 = 71.36, both p < 0.05; the diameters of somas of ChAT+ neurons: 16.62 ± 1.51 μm in DL, 15.71 ± 1.03 μm in VM; Fig. 2). The statistical analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the DL and VM regions in the diameters of somas of each interneuron type (all p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Morphology and spatial distribution of different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum. The images showed the distribution pattern and morphology of NPY+, Cr+, Parv+, and ChAT+ interneuron types in normal striatum at low and high magnification. a The two regions (DL and VM) of striatum through the coronal plane of striatal center. a′–d′ (DL) and a″–d″ (VM) were respectively taken from a–d. a″–d″ showed the cell bodies (white arrowheads), axons (arrows), and dendrites (black arrowheads) of interneurons. The marked white lines in a′ stand for the longest and the shortest diameters of somas. F is short for fusiform, and P is short for polygonal in a′. Scale bars a–d, 250 μm; a′–d′, 50 μm; a″–d″, 50 μm; small images in a′and a″, 30 μm

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the soma size among different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum. The histogram showed comparison of the soma size among different interneuron types in DL and VM regions of striatum. Note that the size of ChAT+ soma is the largest among the three interneuron types while that of Cr+ soma is the smallest in the DL and VM regions of striatum. * p < 0.05 when compared among different interneuron types of the same striatal region

Morphological Characteristics of Dendrites of Different Interneuron Types in the DL and VM Regions of Striatum

In the immuno-stained brain sections, the four different types of interneuron all showed positive somas with several heavily immuno-stained aspiny processes emerging from the somas (Fig. 1). In general, the dendrites displayed dense branches of uniform thickness, with some branches of the dendrites up to the third order ones. The quantitative data about the primary dendrites further showed that Parv+ had the longest primary dendrites (9.75 ± 1.02 μm), followed by ChAT+ , NPY+, and Cr+ (ChAT+: 8.32 ± 1.24 μm; NPY+: 7.51 ± 1.27 μm; Cr+: 5.75 ± 1.03 μm) in sequence in the DL region of striatum. Statistical analyses revealed that there was significant difference in the length of the primary dendrites between Cr+ and Parv+ in the DL region (F 1,10 = 102.16, p < 0.05, Fig. 3). However, in the VM region of striatum, NPY+ had the longest primary dendrites with a length of 8.75 ± 1.28 μm, while Cr+ (6.25 ± 1.03 μm, F 2,15 = 16.72, p < 0.05) and Parv+ (6.25 ± 0.93 μm, F 2,15 = 9.35, p<0.05, Fig. 3) were the shortest. The primary dendritic lengths of Parv+ were of significant difference between the DL and VM regions of striatum (F 1,10 = 87.71, p < 0.05, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the primary dendritic length among different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum. The histogram showed the primary dendritic length among the three interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. * p < 0.05 when compared among different interneuron types of the same striatal region; # p < 0.05 when compared between the DL and VM regions for the same interneuron type

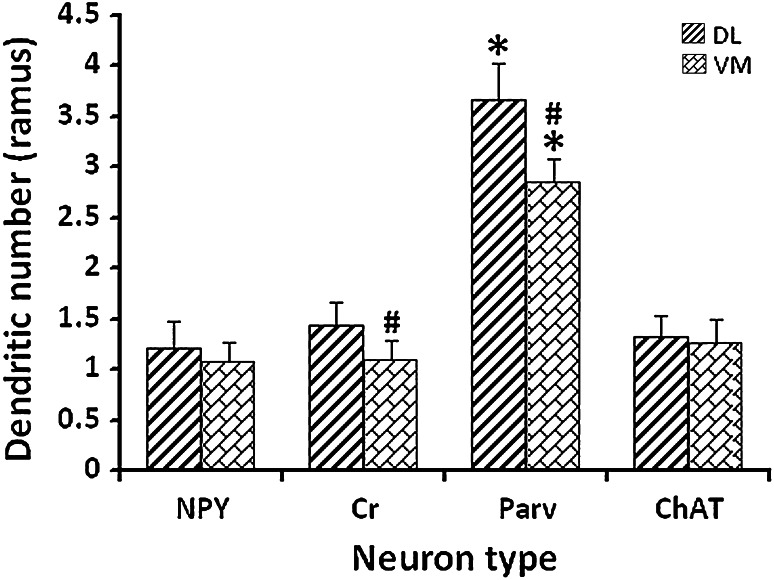

In addition, the numbers of primary dendrites were as follows: NPY+ interneurons having 1.21 ± 0.17 rami in DL and 1.08 ± 0.18 rami in VM; Cr+ interneurons having 1.43 ± 0.24 rami in DL and 1.09 ± 0.20 rami in VM; Parv+ interneurons having 3.67 ± 0.46 rami in DL and 2.85 ± 0.23 rami in VM; ChAT+ interneurons having 1.32 ± 0.21 rami in DL and 1.27 ± 0.22 rami in VM. The numbers of primary dendrites of Parv+ were the largest in comparison to others in both the DL and VM regions of striatum (F 7,39 = 223.24, F 7,39 = 113.64, both p < 0.05, Fig. 4). There was no significant difference between the DL and VM regions in the number of primary dendrites for the NPY+ and ChAT+ interneurons (both p > 0.05). Interestingly, both Cr+ and Parv+ primary dendrites displayed significant difference between the DL and VM regions of striatum (F 1,10 = 22.78, F 1,10 = 54.98, both p < 0.05, Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the primary dendritic number among different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum. The histogram showed the number of primary dendrites among different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. * p < 0.05 when compared among different interneuron types of the same striatal region; # p < 0.05 when compared between the DL and VM regions for the same interneuron type

Spatial Distribution and Quantity of Different Interneuron Types in the DL and VM Regions of Striatum

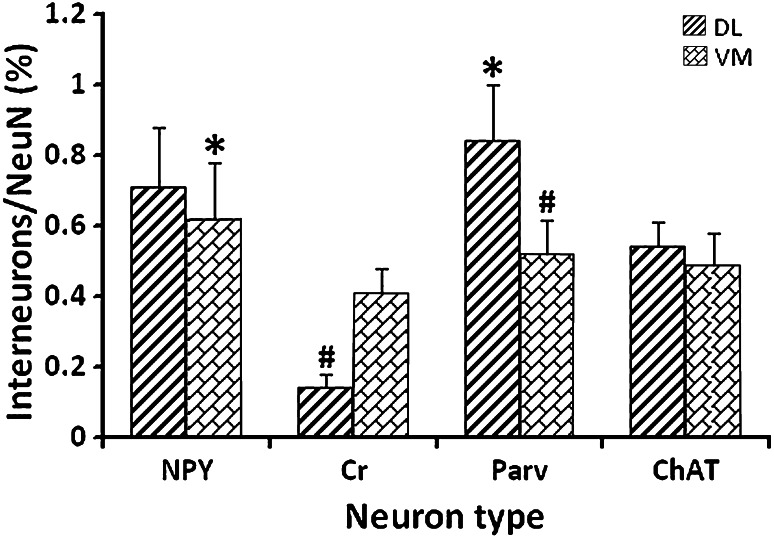

The present results showed that the four different subtypes of interneuron were distributed throughout the rat striatum. Wherein, Cr+ and Parv+ neurons were differentially distributed in the striatum, i.e., Cr+ neurons were more densely distributed in the VM region than in the DL region, while the distribution pattern of Parv+ neurons were opposite from that of Cr+ neurons (Fig. 1). The results from interneurons/NeuN double-labeling showed that simultaneous visualization for different interneurons, and the whole neuron population was detected in different degrees (Fig. 5). In the DL region, quantitative data showed that the percentage of Parv+ interneurons was the highest (0.84 ± 0.16 %, F 3,19 = 76.12, p < 0.05, Fig. 6) among the four types, while the percentage of Cr+ interneurons was the lowest (0.14 ± 0.04 %). However, in the VM region of striatum, the percentage of NPY+ neurons was higher (0.62 ± 0.16 %, F 3,20 = 15.02, p < 0.05, Fig. 6) than other neuron types, while the percentage of Cr+ neurons was the lowest (0.41 ± 0.07 %). There was no significant difference between the DL and VM regions in the percentages of the NPY+ and ChAT+ interneurons (both p > 0.05). In addition, the percentages of Cr+ and Parv+ neurons displayed significant difference between the DL and VM regions of striatum (F 1,10 = 11.67, F 1,10 = 7.88, both p < 0.05, Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Detection of double-labeling of different types of interneurons and NeuN in the striatum. The images showed simultaneous visualization of NPY+, Cr+, Parv+, and ChAT+ interneuron types in the normal striatum at low and high magnification. a′–d′ (DL) and a″–d″ (VM) were taken from a–d, correspondingly. The rectangular boxes at the lower left corner of a′–d′ and a″–d″ were presentation of the neurons (black arrowhead) at higher magnification. a The two regions (DL and VM) of striatum through the coronal plane of striatal center. Scale bars a–d, 300 μm; a′–d′, 150 μm; a″–d″, 150 μm; small images in a′–d′ and a″–d″, 50 μm

Fig. 6.

The percentage of different interneurons in the DL and VM regions of striatum. The histogram showed that the percentage of different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. * p < 0.05 when compared among different interneuron types of the same striatal region; # p < 0.05 when compared between the DL and VM regions for the same interneuron type

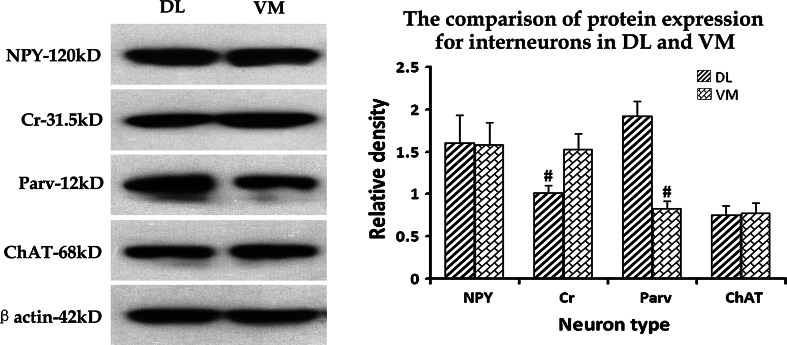

Marker Protein Expression of Different Interneuron Types in the DL and VM Regions of Striatum

Results from Western blot revealed that the expression level of Cr was significantly higher in the VM region than in the DL region (F 1,9 = 79.83, p < 0.05, Fig. 7). In contrast, the expression of Parv was obviously lower in the VM region than in the DL region (F 1,10 = 337.26, p < 0.05, Fig. 7). But there was no significant difference between the two striatal regions in the expression levels of NPY and ChAT (both p > 0.05). These results were consistent with the observation of immuno-labeling (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 7.

The comparison of protein expression among different interneuron types in the DL and VM regions of striatum The Western blot results showed that the express levels of NPY, Cr, Parv, and ChAT proteins in the DL and VM regions of striatum, respectively. The histogram was plotted according to the comparison of the relative density for each interneuron type between the DL and VM striatum. # p < 0.05 when compared between the DL and VM regions for the same interneuron type

Discussion

Previous studies reported that NPY+ interneuron receives both cholinergic and dopaminergic input (Bennett and Bolam 1993) and releases nitric oxide to regulate corticostriatal synaptic plasticity (Centonze et al. 2003). According to existing research, NPY+ interneurons are medium in size and round, polygonal or fusiform in shape with the diameter ranging from 9 to 25 μm. Typical NPY neurons emit 3–5 thick and aspiny dendrites which were mostly non-varicose, branching within 30–50 μm of the soma in the proximal part and taper rapidly, becoming more varicose in the distal regions (Aoki and Pickel 1988; DiFiglia and Aronin 1982; Kawaguchi and Kubota 1993; Vincent et al. 1983). In line with these studies, the present study detected that the somas of NPY+ neurons were mostly fusiform or polygonal and medium-sized in the DL and VM regions of striatum. NPY+ had the longest primary dendrites when compared to the other neuron types in the VM region of striatum. No differences were observed in the dendritic length as well as the number and the percentage of NPY+ between the DL and VM regions of the striatum. Nevertheless, it should be noted that our results merely provided some information about primary dendrites for the four different interneurons in the striatum from rats. Owing to the technical limitation and quality of immunohistochemical method, most of the dendritic trees of these interneurons were not able to be labeled, especially in NPY+, Cr+, and ChAT+ interneurons. In addition, a recent investigation stated that 0.8 % of all neurons were NPY+ interneurons in rat striatum (Oorschot 2013; Rymar et al. 2004). Our current findings further confirmed that the NPY+ interneurons comprised about 0.71 % of the total neurons in the DL region, 0.62 % of the total in the VM region of striatum of rats. The NPY+ interneurons are less than those in the rhesus monkey striatum in which about 1.9 % of the neurons were somatostatin (i.e., NPY) interneurons in the caudate nucleus, and 1.2 % were somatostatin interneurons in the putamen (Deng et al. 2010). The finding is congruent with the viewpoint that interneurons are much more abundant in the striatum of primates such as squirrel monkeys and humans than in that of rodents (Graveland and DiFiglia 1985).

The other GABAergic interneuron expressing the calcium binding protein calretinin is known the least by far. This interneuron type accounts for about 0.6 % of neurons in the whole striatum of rats, evidently less than the abundance of NPY+ and Parv+ neurons, based on cell counts of our immunostained experiment. In contrast, the most abundant interneurons were those expressing Cr+ in primates which implied that Cr+ interneurons play a more important role in the striatal microcircuits in primates than they do in rodents (Wu and Parent 2000). The aforementioned data were supported by these relevant demonstrated observations in the dorsal striatum of rats from Oorschot (2013). Cr+ interneurons are small in size, possessing very few dendrites which are aspiny, and are relatively sparse in the whole striatum. However, early studies in rats described Cr+ interneurons as medium-sized neurons with a diameter of 12–20 μm (Bennett and Bolam 1993). Several subsequent studies reported at least three to four morphologically distinct types of Cr expressing interneurons in the striatum of rats, ranging from small to large in somatic size (Rymar et al. 2004; Schlosser et al. 1999; Wu and Parent 2000). Indeed, the present study merely detected the existence of the small-sized, oval-shaped or triangular Cr+ interneurons in the rat striatum. But our findings about the existence of small-sized morphological type of striatal Cr+ neurons in rat striatum were consistent with the observations in rodent from Tepper et al. (2010). We suspect that these morphological differences in somatic size of Cr+ neurons might be related to age and physical circumstances of subjected animals. It is interesting to note that the proportion of Cr+ interneurons in the VM region is much greater than in the DL region of striatum according to the present study. The finding was consistent with a previously relevant report (Figueredo-Cardenas et al. 1996), which indicates that the Cr+ interneurons may be involved in different physiological functions of the DL and VM striatum. Previous study has reported that the striatal VM region is more involved in cognitive and limbic functions (Voorn et al. 2004). Thus, we presume that Cr+ neurons might be more closely related to aforementioned aspects of the VM region than other striatal interneurons. It has been proposed that the stimulus–response habit learning may selectively involve the dorsal striatum (Packard and Knowlton 2002).

The GABAergic Parv-expressing interneurons are categorized as medium-sized neurons with round and polygonal somas of which the diameter ranging from 16 to 18 μm. They play a fundamental role in the feed forward striatal circuit and the striatal output (Tepper and Bolam 2004). Typical Parv+ neurons emit 5–8 aspiny dendrites that range from almost smooth in the proximal regions to extremely varicose in the distal regions (Kawaguchi and Kubota, 1993). Parv+ neurons in the rat striatum appeared medium in size, with a few primary dendrites (3–4) branching close to the soma in the present study. Although our data revealed that Parv+ neurons were on average the second-largest striatal interneurons among the four types of interneurons, it is interesting to note that most Parv+ neurons in rats exhibited two distinct appearances—mostly medium in size and a few small-sized. Thus, we suppose that Parv+ interneurons might not represent a simple homogenous cell type. In addition, the number of Parv+ interneurons in the present study was in good agree with several relevant studies that these neurons accounted for about 0.7 % of the total in the neostriatum of rats (Luk and Sadikot 2001; Oorschot 2013; Rymar et al. 2004). Furthermore, our results confirmed that Parv+ interneurons were more abundant in the DL region than in the VM region in the striatum of rats. The percentages of Parv+ interneurons in the monkey striatum were 1.0 % (caudate) and 2.4 % (putamen) (Deng et al. 2010), which are higher than those in rat striatum in the present study. A previous study suggested that the DL region of striatum could not only modulate the function of sensorimotor but also play an important role in learning and memory (Packard and Knowlton 2002). We thus suspect that this preferential distribution of Parv+ interneurons in the striatum of rats might be involved in these forementioned aspects.

As previously mentioned, the striatal cholinergic interneuron is also known as the choline acetyltransferase immunolabeled neurons (Bolam et al. 1984). The ChAT+ interneuron is a non-GABAergic interneuron type of the striatum, accounting for about 1 % of the striatal neurons in rats (Oorschot 2013), and presenting similar abundance to be around 1 % of the striatal neuron population in human (Fino and Venance 2011; Graveland et al. 1985; Oorschot 2013; Rymar et al. 2004) and other primates such as Rhesus monkey (Deng et al. 2010). In accordance with previous research, our results showed that they were the largest striatal neurons with a big somatic diameter, and emitted 3–5 thick, smooth, or sparsely primary dendrites. Some studies confirmed that the cholinergic interneurons received inhibitory GABAergic inputs from spiny neurons as well as dopaminergic inputs from the substantia nigra (Bennett and Bolam 1993). Thus, the ChAT+ interneurons as an important component in regulating striatal output may be closely linked with the modulation of local inhibitory circuits.

Our data further revealed the morphologic diversity and properties of different interneuron types including NPY+, Cr+, Parv+, and ChAT+ neurons in the DL and VM regions of the striatum of rats. It provides valuable information for understanding and investigation of the functioning of the striatal interneuron populations. However, it should be noted that the observations of rats may not represent the situations of other mammals or human due to the variations of neuronal morphology and distribution among different species. In general, the distinct spatial distribution of various types of interneurons may underlie the specific functions of different regions of striatum. Furthermore, recently relevant studies focused on the physiological features and functional connections of these interneurons. For instance, Parv+ interneurons and NPY+ interneurons form synaptic connections with MSNs and regulate the firing activity of MSNs (Chuhma et al. 2011), which may exert different effects on MSNs due to their distinct firing patterns as well as connections. The regional characteristics of these striatal interneurons provide facilitations for clarifying synaptic contacts between MSNs and interneurons and for understanding the striatal microcircuit function in rats.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Science Foundations of China (Nos. 31070941, 30770679, 20831006) and the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program, No. 2010CB530004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Yuxin Ma and Qiqi Feng have contributed equally to this article.

References

- Abercrombie M (1946) Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat Rec 94:239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL (1986) Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 9:357–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Pickel VM (1988) Neuropeptide Y-containing neurons in the rat striatum: ultrastructure and cellular relations with tyrosine hydroxylase-containing terminals and with astrocytes. Brain Res 459:205–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Bolam JP (1993) Characterization of calretinin-immunoreactive structures in the striatum of the rat. Brain Res 609:137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam JP, Wainer BH, Smith AD (1984) Characterization of cholinergic neurons in the rat neostriatum. A combination of choline acetyltransferase immunocytochemistry, Golgi-impregnation and electron microscopy. Neuroscience 12:711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Gubellini P, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P (2003) Dopamine, acetylcholine and nitric oxide systems interact to induce corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Rev Neurosci 14:207–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuhma N, Tanaka KF, Hen R, Rayport S (2011) Functional connectome of the striatal medium spiny neuron. J Neurosci 31:1183–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan RL, Wilson CJ, Emson PC, Heizmann CW (1990) Parvalbumin-containing GABAergic interneurons in the rat neostriatum. J Comp Neurol 302:197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng YP, Shelby E, Reiner AJ (2010) Immunohistochemical localization of AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits in the striatum of rhesus monkey. Brain Res 1344:104–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Aronin N (1982) Ultrastructural features of immunoreactive somatostatin neurons in the rat caudate nucleus. J Neurosci 2:1267–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo-Cardenas G, Morello M, Sancesario G, Bernardi G, Reiner A (1996) Colocalization of somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, neuronal nitric oxide synthase and NADPH-diaphorase in striatal interneurons in rats. Brain Res 735:317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fino E, Venance L (2011) Spike-timing dependent plasticity in striatal interneurons. Neuropharmacology 60:780–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveland GA, DiFiglia M (1985) The frequency and distribution of medium-sized neurons with indented nuclei in the primate and rodent neostriatum. Brain Res 327:307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveland GA, Williams RS, DiFiglia M (1985) A Golgi study of the human neostriatum: neurons and afferent fibers. J Comp Neurol 234:317–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y (1993) Correlation of physiological subgroupings of nonpyramidal cells with parvalbumin- and calbindinD28k-immunoreactive neurons in layer V of rat frontal cortex. J Neurophysiol 70:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC (1995) Striatal interneurones: chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci 18:527–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H (1993) GABAergic circuits of the striatum. Prog Brain Res 99:51–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Berke JD (2011) Investigating striatal function through cell-type-specific manipulations. Neuroscience 198:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Mikawa S, Kawaguchi Y (1993) Neostriatal GABAergic interneurones contain NOS, calretinin or parvalbumin. NeuroReport 5:205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk KC, Sadikot AF (2001) GABA promotes survival but not proliferation of parvalbumin-immunoreactive interneurons in rodent neostriatum: an in vivo study with stereology. Neuroscience 104:93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Feng Q, Ma J, Feng Z, Zhan M, Ouyang L, Mu S, Liu B, Jiang Z, Jia Y, Li Y, Lei W (2013) Melatonin ameliorates injury and specific responses of ischemic striatal neurons in rats. J Histochem Cytochem 61:591–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu S, OuYang L, Liu B, Zhu Y, Li K, Zhan M, Liu Z, Jia Y, Lei W, Reiner A (2011) Preferential interneuron survival in the transition zone of 3-NP-induced striatal injury in rats. J Neurosci Res 89:744–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot DE (2013) The percentage of interneurons in the dorsal striatum of the rat, cat, monkey and human: a critique of the evidence. Basal Ganglia 3:19–24 [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG, Knowlton BJ (2002) Learning and memory functions of the Basal Ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci 25:563–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rymar VV, Sasseville R, Luk KC, Sadikot AF (2004) Neurogenesis and stereological morphometry of calretinin-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons of the neostriatum. J Comp Neurol 469:325–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser B, Klausa G, Prime G, Ten BG (1999) Postnatal development of calretinin- and parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the rat neostriatum: an immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 405:185–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Bolam JP (2004) Functional diversity and specificity of neostriatal interneurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14:685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper JM, Tecuapetla F, Koos T, Ibanez-Sandoval O (2010) Heterogeneity and diversity of striatal GABAergic interneurons. Front Neuroanat 4:150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SR, Johansson O (1983) Striatal neurons containing both somatostatin- and avian pancreatic polypeptide (APP)-like immunoreactivities and NADPH-diaphorase activity: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol 217:264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SR, Johansson O, Hokfelt T, Skirboll L, Elde RP, Terenius L, Kimmel J, Goldstein M (1983) NADPH-diaphorase: a selective histochemical marker for striatal neurons containing both somatostatin- and avian pancreatic polypeptide (APP)-like immunoreactivities. J Comp Neurol 217:252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM (2004) Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci 27:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Parent A (2000) Striatal interneurons expressing calretinin, parvalbumin or NADPH-diaphorase: a comparative study in the rat, monkey and human. Brain Res 863:182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaborszky L, Alheid GF, Beinfeld MC, Eiden LE, Heimer L, Palkovits M (1985) Cholecystokinin innervation of the ventral striatum: a morphological and radioimmunological study. Neuroscience 14:427–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]