Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis is a chronic joint disease that involves degeneration of articular cartilage. Pre‐clinical data suggest that doxycycline might act as a disease‐modifying agent for the treatment of osteoarthritis, with the potential to slow cartilage degeneration. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2009.

Objectives

To examine the effects of doxycycline compared with placebo or no intervention on pain and function in people with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 3), MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL up to 28 July 2008, with an update performed at 16 March 2012. In addition, we checked conference proceedings, reference lists, and contacted authors.

Selection criteria

We included studies if they were randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials that compared doxycycline at any dosage and any formulation with placebo or no intervention in people with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in duplicate. We contacted investigators to obtain missing outcome information. We calculated differences in means at follow‐up between experimental and control groups for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RR) for binary outcomes.

Main results

We identified one additional trial (232 participants) and included two trials (663 participants) in this update. The methodological quality and the quality of reporting were considered moderate. At end of treatment, clinical outcomes were similar between the two treatment groups, with an effect size of ‐0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.22 to 0.13), corresponding to a difference in pain scores between doxycycline and control of ‐0.1 cm (95% CI ‐0.6 to 0.3 cm) on a 10‐cm visual analogue scale, or 32% versus 29% improvement from baseline (difference 3%; 95% CI ‐5% to 10%). The effect size for function was ‐0.07 (95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.10), corresponding to a difference between doxycycline and control of ‐0.2 (95% CI ‐0.5 to 0.2) on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) disability subscale with a range of 0 to 10, or 24% versus 21% improvement (difference 3%; 95% CI ‐3% to 10%). The difference in changes in minimum joint space narrowing assessed in one trial was in favour of doxycycline (‐0.15 mm; 95% CI ‐0.28 to ‐0.02 mm), which corresponds to a small effect size of ‐0.23 standard deviation units (95% CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.02). More participants withdrew from the doxycycline group compared with placebo due to adverse events (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.06 to 4.90). There was no evidence that participants in the doxycycline group experienced more serious adverse events than those in the placebo group, but the estimate was imprecise (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.68).

Authors' conclusions

In this update, the strength of evidence for effectiveness outcomes was improved from low to moderate and we confirmed that the symptomatic benefit of doxycycline is minimal to non‐existent, while the small benefit in terms of joint space narrowing is of questionable clinical relevance and outweighed by safety problems. The CIs of the summary estimates now exclude any clinically relevant difference in improvement of symptoms and the small benefit in terms of joint space narrowing does not outweigh the harms.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Antirheumatic Agents; Antirheumatic Agents/adverse effects; Antirheumatic Agents/therapeutic use; Doxycycline; Doxycycline/adverse effects; Doxycycline/therapeutic use; Osteoarthritis, Hip; Osteoarthritis, Hip/drug therapy; Osteoarthritis, Knee; Osteoarthritis, Knee/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Doxycycline for osteoarthritis

This summary of a Cochrane review presents what we know from research about the effect of doxycycline on osteoarthritis. After searching for all relevant studies, they found two studies with 663 people.

The review shows that in people with osteoarthritis:

‐ doxycycline will not result in clinically important improvement of joint pain or physical function, while the small benefit in terms of joint space narrowing is of questionable clinical relevance;

‐ doxycycline probably causes side effects. We often do not have precise information about side effects and complications. This is particularly true for rare but serious side effects.

What is osteoarthritis and what is doxycycline?

Osteoarthritis is a disease of the joints, such as your knee or hip. When the joint loses cartilage, the bone grows to try and repair the damage. However, instead of making things better the bone grows abnormally and makes things worse. For example, the bone can become misshapen and make the joint painful and unstable. This can affect your physical function or ability to use your knee.

It has been claimed that doxycycline, a type of antibiotic, might stop the process of damage to the joints. It is taken in pill form.

Best estimate of what happens to people with osteoarthritis who take doxycycline:

Pain

‐ The effect of doxycycline in pain symptoms is not clinically important.

‐ People who took doxycycline rated improvement in their pain to be about 1.9 on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain) after 18 months.

‐ People who took a placebo rated improvement in their pain to be about 1.8 on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain) after 18 months.

Another way of saying this is:

‐ 33 people out of 100 who use doxycycline respond to treatment (33%).

‐ 31 people out of 100 who use placebo respond to treatment (31%).

‐ two more people respond to treatment with doxycycline than with placebo (difference of 2%).

Physical function

‐ The effect of doxycycline in physical function is not clinically important.

‐ People who took doxycycline rated improvement in their physical function to be about 1.4 on a scale of 0 (no disability) to 10 (extreme disability) after 18 months.

‐ People who took a placebo rated improvement in their physical function to be about 1.2 on a scale of 0 (no disability) to 10 (extreme disability) after 18 months.

Another way of saying this is:

‐ 29 people out of 100 who use doxycycline respond to treatment (29%).

‐ 26 people out of 100 who use placebo respond to treatment (26%).

‐ three more people respond to treatment with doxycycline than with placebo (difference of 3%).

Side effects

‐ 20 people out of 100 who took doxycycline experienced side effects of any type (20%).

‐ 15 people out of 100 who took a placebo experienced side effects of any type (15%).

‐ five more people who took doxycycline experienced side effects of any type (absolute difference of 5%).

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Doxycycline compared with placebo for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip | ||||||

|

Participant or population: participants with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip Settings: clinical research centres Intervention: doxycycline Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk1 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Doxycycline | |||||

|

Pain 10‐cm VAS scale (median follow‐up: 18 months) |

‐1.8 cm pain1

on 10‐cm VAS2 29% improvement3 |

‐1.9 cm pain (Δ ‐0.1 cm, ‐0.6 to +0.3 cm)2 32% improvement3 (Δ 3%, ‐5% to 10%) |

ES ‐0.05 (‐0.22 to 0.13) | 524 (2) | +++O moderate4 | Little evidence of beneficial effect (NNTB: not statistically significant) |

|

Function WOMAC function (range 0 to 10) (median follow‐up: 18 months) |

‐1.2 units on WOMAC1

(range 0 to 10)5 21% improvement6 |

‐1.4 units on WOMAC5 (Δ ‐0.2, ‐0.5 to +0.2)5 24% improvement6 (Δ 3%, ‐3% to 10%) |

ES ‐0.07 (‐0.25 to 0.1) | 517 (2) | +++O moderate4 | Little evidence of beneficial effect (NNTB: not statistically significant) |

|

Minimum joint space width (follow‐up: 30 months) |

‐45 mm change |

‐30 mm change (Δ 15 mm, 2 to 28 mm) |

361 (1) | +++O moderate7 | No reasonable assumption could be made for the calculation of NNTB | |

|

Number of participants experiencing any adverse event (follow‐up: 6 months) |

150 per 10008 | 204 per 1000 (162 to 258) |

RR 1.36 (1.08 to 1.72) | 232 (1) |

++OO low9 |

NNTH 19 (95% CI 9 to 83) |

|

Number of participants withdrawn due to adverse events (median follow‐up: 18 months) |

17 per 10008 | 39 per 1000 (18 to 83) |

RR 2.28 (1.06 to 4.90) | 663 (2) | ++OO low9 |

NNTH 46 (95% CI 15 to 980) |

|

Number of participants experiencing any serious adverse event (median follow‐up: 18 months) |

4 per 1000 8 | 4 per 1000 (3 to 7) |

RR 1.07 (0.68 to 1.68) | 663 (2) | ++OO low9 |

Little evidence of harmful effect (NNTH: not statistically significant) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). No transformations were performed for minimum joint space width. CI: confidence interval; ES: effect size; RR: risk ratio; GRADE: GRADE Working Group grades of evidence (see explanations); NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality (++++): Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality (+++O): Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality (++OO): Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality (+OOO): We are very uncertain about the estimate.

1 Median reduction as observed across placebo groups in large osteoarthritis trials (see Methods section, Nuesch 2009c). 2 Effect sizes were back‐transformed onto a 10‐cm VAS on the basis of a typical pooled SD of 2.5 cm in large trials that assessed pain using a VAS and expressed as change based on an assumed standardised reduction of 0.72 standard deviation units in the control group.

3 Percentage improvement was calculated based on median observed pain at baseline across control groups of large osteoarthritis trials of 6.1 cm on 10 cm VAS (Nuesch 2009c).

4 Downgraded (1 level) because it is unclear whether one of the two studies had a proper concealment of allocation, in both studies the analyses were not done according to the intention‐to‐treat principle, and one of the two studies had a restricted population of obese women, which hampers directness.

5 Effect sizes were back‐transformed onto a standardised WOMAC disability score ranging from 0 to 10 on the basis of a typical pooled SD of 2.1 in trials that assessed function using WOMAC disability scores and expressed as change based on an assumed standardised reduction of 0.58 standard deviation units in the control group.

6 Percentage of improvement was calculated based on median observed WOMAC function scores at baseline across control groups of large osteoarthritis trials of 5.6 units (Nuesch 2009c).

7 Downgraded (1 level) because it is unclear whether the study had a proper concealment of allocation, and because the study had a restricted population of obese women, which hampers directness.

8 Median control risk across placebo groups in large osteoarthritis trials (see Methods section, Nuesch 2009c).

9 Downgraded (2 levels) because it is unclear whether one of the two studies had a proper concealment of allocation, estimates are imprecise with confidence intervals including negligible and appreciable effects, and one of the two studies had a restricted population of obese women, which hampers directness.

Background

Description of the condition

Osteoarthritis is a chronic joint disease that involves structural changes of the joint, leading to pain and functional limitations (Juni 2006; Zhang 2011). It is characterised by focal areas of loss of articular cartilage in synovial joints accompanied by subchondral bone changes, osteophyte formation at the joint margins, thickening of the joint capsule and mild synovitis.

Description of the intervention

Doxycycline is a tetracycline antibiotic that has been shown to induce inhibition of cartilage matrix metallo‐proteinases (MMPs) and to slow down the progression of structural damage to the affected joint (Smith 1996; Shlopov 1999). Doxycycline was therefore suggested as a disease‐modifying agent for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

How the intervention might work

Treatment with oral doxycycline may slow down the rate of joint space narrowing, which is used as a surrogate measure for cartilage loss of the knee in people with knee osteoarthritis (Brandt 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Treatment benefits of putative chondro‐protective disease‐modifying agents are still controversial. Chondroitin and glucosamine are other potentially structure‐modifying pharmacological substances that are widely used to reduce the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. However, some meta‐analyses have questioned their effectiveness because of large heterogeneity between studies and biases introduced by industry‐sponsored, methodologically weak and small trials (Towheed 2005; Reichenbach 2007; Vlad 2007; Wandel 2010). As a tetracycline antibiotic, doxycycline interferes with various biological pathways and has effects on tissues other than cartilage (Rubin 2000). Safety concerns about the long‐term use of doxycycline have also been expressed, especially in elderly patients with co‐morbid conditions (Dieppe 2005). Adverse events commonly associated with the use of tetracycline antibiotics include nausea, vomiting, epigastric burning, vaginal candidiasis and photosensitivity (Shapiro1997).

Objectives

We set out to compare doxycycline with placebo or no specific intervention in people with knee or hip osteoarthritis in terms of effects on pain, function and safety outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials with a control group receiving placebo or no intervention.

Types of participants

Studies including at least 75% of participants with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip confirmed clinically or radiologically, or both.

Types of interventions

Trials investigating doxycycline at any dosage and in any formulation. Eligible control interventions were placebo or no intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Main outcomes were pain and function, as currently recommended for osteoarthritis trials (Altman 1996; Pham 2004). If data on more than one pain scale were provided for a trial, we referred to a previously described hierarchy of pain‐related outcomes (Juni 2006; Reichenbach 2007) and extracted data on the pain scale that was highest on this list. For example, if both the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain subscores and pain on walking on a visual analogue scale (VAS) were reported for a trial, we only extracted and analysed the data on the outcome pain on walking.

Global pain.

Pain on walking.

WOMAC osteoarthritis index pain subscore.

Composite pain scores other than WOMAC.

Pain on activities other than walking.

Rest pain or pain during the night.

WOMAC global algofunctional score.

Lequesne osteoarthritis index global score.

Other algofunctional scale.

Patient's global assessment.

Physician's global assessment.

If data on more than one function scale were provided for a trial, we extracted data according to the hierarchy presented below.

Global disability score.

Walking disability.

WOMAC disability subscore.

Composite disability scores other than WOMAC.

Disability other than walking.

WOMAC global scale.

Lequesne osteoarthritis index global score.

Other algofunctional scale.

Patient's global assessment.

Physician’s global assessment.

If pain or function outcomes were reported at several time points, we extracted the measure at the end of the trial or at a maximum of three months after termination of therapy, whichever came first.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were minimum and mean radiographic joint space width, the number of participants experiencing any adverse event, participants who withdrew because of adverse events, and participants experiencing any serious adverse events. We defined serious adverse events as events resulting in hospitalisation, prolongation of hospitalisation, persistent or significant disability, congenital abnormality/birth defect of offspring, life‐threatening events or death (European Commission 2010).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2008, issue 3), MEDLINE (1966 to July 2008) and EMBASE (1975 to July 2008) through the Ovid platform (www.ovid.com), and CINAHL (1937 to July 2008) through EBSCOhost, using truncated variations of preparation names, including brand names, combined with truncated variations of terms related to osteoarthritis, all as text words. We applied a validated methodological filter for controlled clinical trials (Dickersin 1994). The specific search algorithms are displayed in Appendix 1 for MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, and in Appendix 2 for CENTRAL. We updated the search using CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE up to 16 March 2012.

Searching other sources

We manually searched conference proceedings of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), and Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI), used Science Citation Index to retrieve reports citing relevant articles, contacted content experts and trialists, and screened reference lists of all obtained articles, including related reviews. Finally, we searched several clinical trial registries (www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.controlled‐trials.com, www.actr.org.au and www.umin.ac.jp/ctr) to identify ongoing trials. The last update of the search was performed on 22 March 2012. OARSI conference proceedings were not searched for the update as we no longer had access to this database.

Data collection and analysis

We used a generic protocol with instructions for data extraction, quality assessment and statistical analyses, which was approved by the editorial board of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group. The same protocol was applied in our previous reviews (Nuesch 2009a; Nuesch 2009b; Rutjes 2009a; Rutjes 2009b; Reichenbach 2010; Rutjes 2010).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (originally EN and AR; BdC and AR for the update) independently evaluated all yielded titles and abstracts for eligibility. We resolved disagreements by consensus. No language restrictions were applied. If several reports described the same trial, we chose the most complete report as the main report and checked the remaining reports for complementary data on clinical outcomes, descriptions of study participants or design characteristics.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (originally EN and AR; BdC and AR for the update) extracted trial information independently using a standardised, piloted data extraction form accompanied by a codebook. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involvement of a third review author (SR or PJ). We extracted generic and trade names of the experimental intervention, the type of control used, dosage, frequency and duration of treatment, participant characteristics (average age, gender, mean duration of symptoms, type of joints affected), type of pain‐ and function‐related outcome extracted, trial design, trial size, duration of follow‐up, type and source of financial support, and publication status from trial reports. Whenever possible, we used results from an intention‐to‐treat analysis. If effect sizes could not be calculated, we contacted the authors for additional data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (originally EN and AR; BdC and AR for the update) independently assessed the adequacy of randomisation, blinding and analyses (Juni 2001). We resolved disagreements by consensus or discussion with a third review author (SR or PJ). We assessed two components of randomisation: generation of allocation sequences and concealment of allocation. We considered generation of sequences adequate if it resulted in an unpredictable allocation schedule; mechanisms considered adequate included random‐number tables, computer‐generated random numbers, minimisation, coin tossing, shuffling cards and drawing lots; trials using potentially predictable allocation mechanisms, such as alternation or the allocation of participants according to date of birth, were considered quasi‐randomised. We considered concealment of allocation adequate if the investigators responsible for participant inclusion were unable to suspect before allocation which treatment was next; methods considered adequate included central randomisation, pharmacy‐controlled randomisation using identical pre‐numbered containers, and sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes (Nuesch 2009a; Rutjes 2009a). We considered blinding of the participants adequate if experimental and control preparations were explicitly described as indistinguishable or if a double‐dummy technique was used (Nuesch 2009a). We considered blinding of therapists and outcome assessors adequate if it was explicitly mentioned in the report that they were unaware of the assigned treatment. However, if pain outcomes were participant‐administered we considered participants to be the outcome assessors and rated blinding of outcome assessors adequate if participants were deemed adequately blinded as described above. We considered analyses adequate if all randomised participants were included in the analysis (intention‐to‐treat principle). We considered trials to have a high risk of selective reporting bias if we identified one or more outcome measures in published reports, protocols or trial registries for which results were not reported. Finally, we used GRADE to describe the quality of the overall body of evidence (Guyatt 2008; Higgins 2011), defined as the extent of confidence in the estimated treatment benefits and harms.

Data synthesis

We expressed continuous outcomes as effect sizes in standard deviation units, with the differences in mean values at the end of follow‐up across treatment groups divided by the pooled standard deviation. If differences in mean values at the end of the treatment were unavailable, we used differences in mean changes. If some of the required data were unavailable, we used approximations as previously described (Reichenbach 2007). An effect size of ‐0.20 standard deviation units can be considered a small difference between experimental and control groups, an effect size of ‐0.50 a moderate difference, and ‐0.80 a large difference (Cohen 1988; Juni 2006). We expressed binary outcomes as risk ratios (RR). We pooled treatment effect estimates across trials using a standard inverse‐variance random‐effects model, which fully accounted for between‐study variance. We quantified between‐study variance using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003), which describes the percentage of variation across trials that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than to chance, and the corresponding Chi2 test. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% may be interpreted as low, moderate and high between‐trial heterogeneity, although the size of trials included in the meta‐analysis should be taken into consideration for proper interpretation (Rucker 2008).

We converted effect sizes of pain intensity and function to odds ratios (ORs) (Chinn 2000; da Costa 2012) as the first step to derive numbers needed to treat to cause one additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or treatment response on pain or function as compared with placebo, and numbers needed to treat to cause one additional harmful outcome (NNTH) (as was done for the 'Summary of findings table'). We defined treatment response as a 50% improvement in scores (Clegg 2006). With a median standardised pain intensity at baseline of 2.4 standard deviation units, observed in large osteoarthritis trials (Nuesch 2009c), this corresponds to an average decrease in scores of 1.2 standard deviation units. Based on the median standardised decrease in pain scores of 0.72 standard deviation units (Nuesch 2009c), we calculated that a median of 31% of participants in the placebo group would achieve an improvement of pain scores of 50% or more. This percentage was used as the control group response rate to derive from ORs the response rate in the experimental group. NNTBs for treatment response on pain were derived by calculating the inverse of the difference between experimental and control group response rates. Based on the median standardised WOMAC function score at baseline of 2.7 standard deviation units and the median standardised decrease in function scores of 0.58 standard deviation units (Nuesch 2009c), 26% of participants in the placebo group would achieve a reduction in function of 50% or more. Again, this percentage was used as the control group response rate to derive from ORs the response rate in the experimental group, which were then used to calculate NNTBs for treatment response on function. The median risks of 150 participants with adverse events per 1000 patient‐years, four participants with serious adverse events per 1000 patient‐years, and 17 drop‐outs due to adverse events per 1000 patient‐years as observed in placebo groups in large osteoarthritis trials (Nuesch 2009c) were used to calculate NNTHs for safety outcomes. We performed analyses in RevMan version 5 (RevMan 2011). All P values were two‐sided.

Results

Description of studies

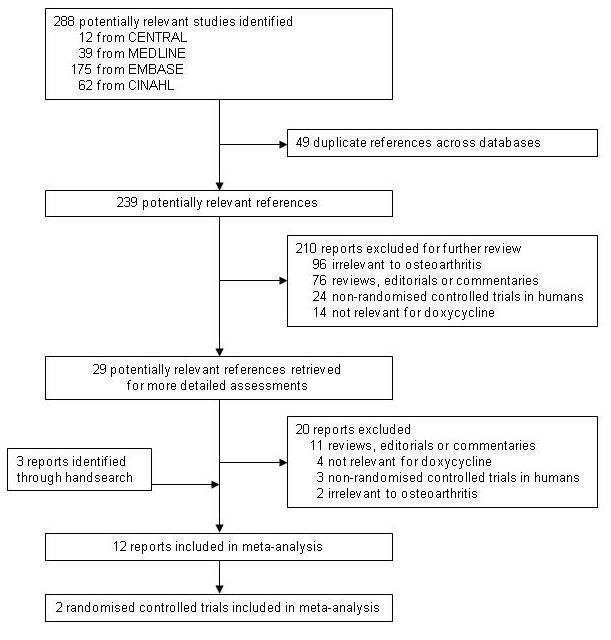

We retrieved 288 potentially relevant reports from our electronic searches (Figure 1). We excluded a randomised placebo‐controlled trial of doxycycline in seronegative arthritis (Smieja 2001) and an animal study that assessed the effects of oral doxycycline in dogs (Brandt 1995). Twelve reports, describing two randomised controlled trials, met our inclusion criteria (Brandt 2005; Snijders 2011). The trial by Snijders 2011 was identified during the update of our literature search. We did not find any additional completed trials in conference proceedings, neither did we identify relevant ongoing trials in trial registers. The trial by Brandt et al. (Brandt 2005) was a multicentre, placebo‐controlled trial in 431 obese women with radiologically confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee. After a single‐blind placebo run‐in of four weeks' duration, which was designed to allow the exclusion of participants unlikely to be compliant with trial procedures, participants were randomly allocated to receive doxycycline 100 mg or placebo twice a day for 30 months. Participants were permitted to take any pain medication throughout the trial. The trial by Snijders et al. (Snijders 2011) was a single‐centre, placebo‐controlled trial in 232 participants with radiologically confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee and a score of ≥ 20 in the WOMAC pain subscale ranging from 0 to 100. Participants were randomly allocated to receive doxycycline 100 mg or placebo twice a day for 24 weeks. Participants were permitted to take pain medication throughout the trial, but opioids other than tramadol were not allowed.

1.

Flow chart.

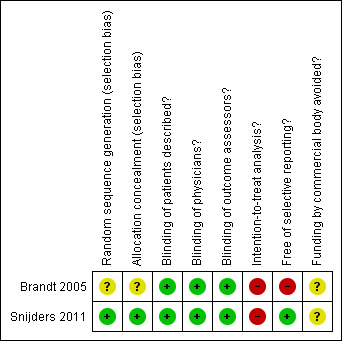

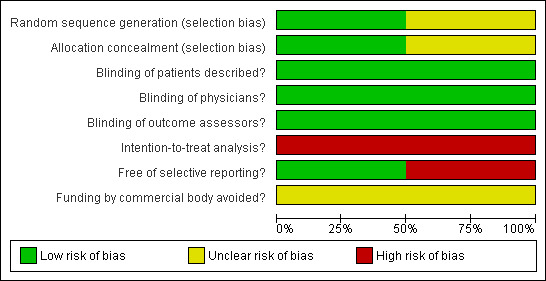

Risk of bias in included studies

An overview of the methodological characteristics of the included trial is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The trial by Brandt et al. (Brandt 2005) was described as randomised in blocks of six, although mechanisms to generate blocks of random sequences and methods used to conceal allocation to treatments were not specified. The trial was reported as double blind after a single‐blind run‐in period. We deemed blinding of participants adequate in view of the use of a matching placebo. Participants were explicitly described as blinded, whereas blinding of treating physicians was not explicitly described. Analyses of clinical outcomes, such as pain and function, were based on 307 participants who completed the 30‐month treatment period as mandated in the protocol (Brandt 2005). Analyses of radiological outcomes included all 361 participants who returned for their radiographic follow‐up irrespective of whether they discontinued the study drug. Safety analyses included all 431 randomised participants according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. The primary outcome of the trial was joint space narrowing on the semiflexed AP view in the tibiofemoral joint (Buckland‐Wright 1995). Measurements were done manually, according to the method of Lequesne (Lequesne 1995), using the points of a screw‐adjustable compass and a graduated magnifying lens. Measurements were made by an observer who was blinded to the treatment group assignment of the subject. The intra‐ and inter‐reader reproducibilities of repeated measurements of joint space width in a random sample of 30 radiographs (on which all identifying information was masked) were excellent (intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.99 and 0.96, respectively). Assessors determining the joint space width were not blinded to the sequence of the radiographs. No sample size calculation was described. The trial was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH); no commercial funding was reported.

2.

Methodological characteristics and source of funding of the included trial. (+) indicates low risk of bias, (?) unclear and (‐) a high risk of bias on a specific item.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

In the trial by Snijders et al. (Snijders 2011), participants were randomised using a computer‐generated randomisation list stratified by pain intensity (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 on the WOMAC pain subscale). Coded drug packs, organised by an independent pharmacist who centrally stored the randomisation list, were used for concealment of allocation. The treating physician had no access to the randomisation schedule. The trial was reported as triple‐blind, with participants, physicians and outcome assessors explicitly described to be blinded. We considered blinding of participants and physicians to be adequate given matching placebo and adequate concealment of allocation. We considered blinding of outcome assessors adequate because all outcomes were assessed either by the participant or physician, who both were deemed adequately blinded. Analyses of pain and function outcomes were based on 218 and 210 participants, respectively, who had non‐missing data at the end of the 24 week treatment period. Safety analyses were based on all 232 participants randomised according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. The primary outcome of the trial was clinical response at the end of treatment as defined by the OMERACT‐OARSI responder criteria (Pham 2004). It remained unclear whether the trial was supported by commercial funding.

For the effectiveness outcomes, we classified the quality of the evidence (Guyatt 2008) as moderate, because two large‐scale trials of moderate quality were available, with one of the trials lacking a description of concealment of allocation and only including obese women (Brandt 2005), and both trials lacking intention‐to‐treat‐analysis (see 'Table 1'). For any adverse event, serious adverse events, and withdrawals due to adverse events outcomes, we classified the quality of the evidence (Guyatt 2008) as low because estimates were imprecise with confidence intervals including negligible and appreciable effects, and because one of the trials lacked a description of concealment of allocation and only included obese women (Brandt 2005) (see 'Table 1').

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

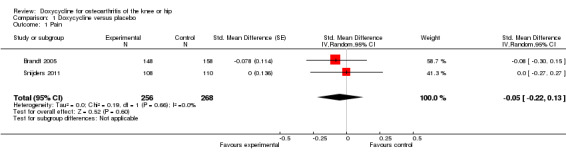

In the trial by Brandt et al. (Brandt 2005) knee pain was measured after a 15.2‐m (50‐feet) walk on a 10‐cm VAS, and in the trial by Snijders et al. (Snijders 2011) pain was measured using the WOMAC pain subscale. The analyses suggested that there is no difference between doxycycline and placebo in pain relief. The effect size was ‐0.05 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.22 to 0.13; P = 0.60; Analysis 1.1), which corresponds with a difference between doxycycline and placebo of ‐0.1 cm on a 10‐cm VAS, favouring doxycycline. Visual inspection of the forest plot and the I2 estimate indicated no relevant heterogeneity of treatment effect estimates across the two trials (I2 = 0%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 1 Pain.

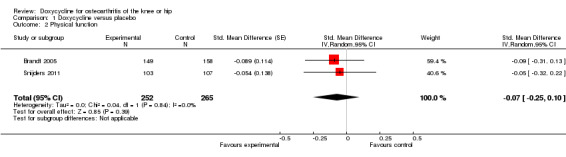

The WOMAC function subscale was used to measure function in both trials. The analyses suggested an effect size of ‐0.07 (95% CI ‐0.25 to 0.10; P = 0.39; Analysis 1.2), corresponding to a difference between doxycycline and control of ‐0.2 (95% CI ‐0.5 to 0.2) on the WOMAC disability subscale with a range of 0 to 10. Visual inspection of the forest plot and the I2 estimate again did not indicate any relevant difference between trial heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 2 Physical function.

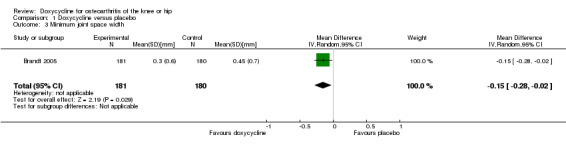

The difference in changes in minimum joint space narrowing was in favour of doxycycline (‐0.15 mm; 95% CI ‐0.28 to ‐0.02 mm; P = 0.03; Analysis 1.3), which corresponds to a small effect size of ‐0.23 standard deviation units (95% CI ‐0.44 to ‐0.02).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 3 Minimum joint space width.

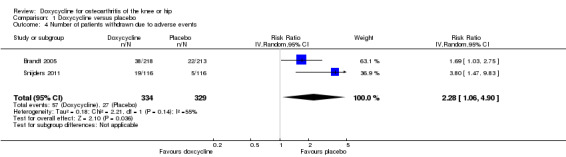

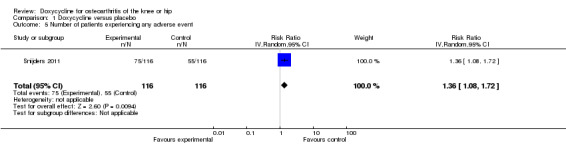

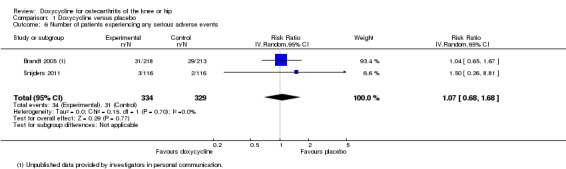

Regarding safety, participants were more than twice as likely to withdraw due to adverse events in the doxycycline group compared to the placebo group (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.06 to 4.90; P = 0.04; I2 = 55%; Analysis 1.4). Data for the number of participants experiencing any type of adverse event was only available for the trial of Snijders et al. (Snijders 2011; data provided in personal communication). Compared to the placebo group, participants in the doxycycline group were more likely to experience any type of adverse event (RR 1.36; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.72; Analysis 1.5). For the trial of Brandt et al. (Brandt 2005), data on serious adverse events were provided by investigators in personal communications. In the combined analysis on serious adverse events, there was no evidence that doxycycline was unsafe, but the estimate was imprecise (RR 1.07; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.68; P = 0.77; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.6). In both trials, there were no fatal events and none of the serious adverse events were deemed to be related to doxycycline (Brandt 2005; Snijders 2011).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 4 Number of patients withdrawn due to adverse events.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 5 Number of patients experiencing any adverse event.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Doxycycline versus placebo, Outcome 6 Number of patients experiencing any serious adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this update, we found that the symptomatic benefit of doxycycline in people with osteoarthritis of the knee was minimal to non‐existent. The small benefit in terms of joint space narrowing was of questionable clinical relevance. The increased risks of experiencing adverse events, and dropping out due to adverse events in the doxycycline group compared to placebo indicates that this benefit is outweighed by safety problems.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence is based on two large randomised trials (Brandt 2005; Snijders 2011). The trial of Brandt et al. included only obese women with mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the knee and was designed to detect differences in joint space narrowing rather than differences in clinical outcomes (Brandt 2005). No threshold for the level of knee pain was used for inclusion and the average level of knee pain was low at baseline, leaving little room for improvement. Radiological and clinical outcomes correlate poorly in people with osteoarthritis and it is not surprising that effects of doxycycline differed for these outcomes. Joint space width in millimetres evaluated on radiographs is currently considered to be the preferred technique to evaluate structural progression in osteoarthritis, and is required by the regulatory agencies (Hellio 2009). The use of semiflexed radiographs instead of anteroposterior (AP) views improves detection of tibiofemoral joint space narrowing, especially in early osteoarthritis (Merle‐Vincent 2007). However, there is a debate about how to define relevant radiographic progression, and a published OARSI‐OMERACT initiative recommends dichotomising the continuous variable of joint space narrowing to distinguish between progressors and non‐progressors, based on the absolute change in joint space width over a pre‐defined threshold (Ornetti 2009). Mazzuca et al. reported that doxycycline did not differ from placebo in the frequency of relevant joint space loss using a range of different cut‐offs to distinguish between the presence or absence of relevant joint space loss (≥ 0.5 mm, ≥ 1.0 mm, ≥ 20%, or ≥ 50% of joint space width at baseline; Mazzuca 2006). No evidence for the effect of doxycycline on joint space narrowing is available for people representing a broader spectrum of osteoarthritis, including males, people with hip osteoarthritis and non‐obese people. In the trial by Snijders et al., participants were included regardless of gender or body weight (Snijders 2011). As opposed to the trial by Brandt et al., this trial had symptom severity as primary outcome measure, requiring a minimum pain severity for inclusion in the trial. Although participants presented a moderate level of knee pain at baseline, on average 49 on a scale from 0 to 100, no effect of doxycycline compared to placebo was observed on pain or disability, confirming the results of the earlier conducted trial by Brandt et al. (Brandt 2005).

According to our 'Risk of bias' assessment, both trials made some suboptimal design choices. Brandt 2005 was potentially biased: it remained unclear whether sequence generation and allocation concealment were adequate and a high number of participants were excluded from analyses, which may have resulted in some overestimation of benefits (Nuesch 2009c). In addition, there are discrepancies in definitions of the primary outcome between the trial protocol (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000403) and the published trial report (Brandt 2005). The single primary outcome of this trial as originally specified in the protocol was joint space narrowing in the tibiofemoral compartment of the contralateral knee with little structural changes, whereas in the published trial report there were two primary outcomes, joint space narrowing in index and in contralateral knee. Although doxycycline slightly decreased joint space narrowing in the index knee, it had no effect in the contralateral knee. In view of the change in the primary outcome definition and the lack of effect found for the original primary outcome, we considered the effects of doxycycline on joint space narrowing in the trial by Brandt 2005 to be unclear. The trial by Snijders 2011 is considerably less prone to bias. Blinding of participants, clinicians and outcome assessors was adequate and adequate methods were used to conceal treatment allocation.

Potential biases in the review process

We based our review on a broad literature search and it seems unlikely that we missed relevant trials (Egger 2003). Two review authors performed selection of trials and data extraction independently and in duplicate to minimise bias and transcription errors (Egger 2001; Gøtzsche 2007). As with any systematic review, our study is limited by the quality of the available evidence. As indicated above, two trials were available, with one of the trials (Brandt 2005) having some methodological shortcomings. However, both trials were large and consistently showed clinical null effects. The biases discussed would on average result in some overestimation of treatment effect and, even if real, would not change any of our conclusions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Doxycycline may reduce the progression of cartilage degeneration in canine osteoarthritis through inhibition of cartilage MMPs (Yu 1992; Brandt 1995). Similar results were obtained in guinea pigs (Greenwald 1994) and rabbits (Golub 1993). In a canine osteoarthritis model, doxycycline reduced disease progression (Yu 1992). This notion supports the observed reduction in joint space narrowing in the randomised trial in humans (Brandt 2005). When studied in people with chronic seronegative arthritis (Smieja 2001), doxycycline had no effect on pain reduction or function improvement compared to placebo after three months of treatment. The trials included in our review included participants with non‐inflammatory symptomatic osteoarthritis and used a longer treatment duration but results were similar (Brandt 2005; Snijders 2011).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The symptomatic benefit of doxycycline is minimal to non‐existent, while the small benefit in terms of joint space narrowing is of questionable clinical relevance and outweighed by safety problems.

Implications for research.

The available evidence of the effectiveness of doxycycline is based on two randomised trials. Despite some methodological shortcomings, and despite the sampling of only obese women in Brandt 2005, it seems unlikely that future trials would detect a clinically relevant benefit of doxycycline. In addition, the number of 663 patients included in our meta‐analysis exceeds the optimal information size (Pogue 1997; Guyatt 2011) of 342 patients, which was defined as the size of a single trial with adequate power of 80% to detect a minimally important difference between groups of 0.37 standard deviation units (Rutjes 2012) for pain, function or joint space width at an alpha level of 0.01. Therefore, we see no need for additional trials.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 June 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Change in authorship |

| 20 March 2012 | New search has been performed | Search updated, one new trial included |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2008 Review first published: Issue 4, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 May 2008 | Amended | CMSG ID C118‐R |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group editorial team for valuable comments and Malcolm Sturdy for database support. The authors are grateful to Kenneth Brandt, Steve Mazzuca and Gijs Snijders for providing unpublished data from their trial. We would like to acknowledge Sven Trelle for his contribution to the original systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL search strategy

| OVID MEDLINE | OVID EMBASE | CINAHL through EBSCOhost |

|

Search terms for design 1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized controlled trial.sh. 4. random allocation.sh. 5. double blind method.sh. 6. single blind method.sh. 7. clinical trial.pt. 8. exp clinical trial/ 9. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 10. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 11. placebos.sh. 12. placebo$.ti,ab. 13. random$.ti,ab. 14. research design.sh. 15. comparative study.sh. 16. exp evaluation studies/ 17. follow up studies.sh. 18. prospective studies.sh. 19. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. |

Search terms for design 1. randomized controlled trial.sh. 2. randomization.sh. 3. double blind procedure.sh. 4. single blind procedure.sh. 5. exp clinical trials/ 6. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 7. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 8. placebo.sh. 9. placebo$.ti,ab. 10. random$.ti,ab. 11. methodology.sh. 12. comparative study.sh. 13. exp evaluation studies/ 14. follow up.sh. 15. prospective study.sh. 16. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. |

Search terms for design 1. (MH "Clinical Trials+") 2. (MH "Random Assignment") 3. (MH "Double‐Blind Studies") or (MH "Single‐Blind Studies") 4. TX (clin$ n25 trial$) 5. TX (sing$ n25 blind$) 6. TX (sing$ n25 mask$) 7. TX (doubl$ n25 blind$) 8. TX (doubl$ n25 mask$) 9. TX (trebl$ n25 blind$) 10. TX (trebl$ n25 mask$) 11. TX (tripl$ n25 blind$) 12. TX (tripl$ n25 mask$) 13. (MH "Placebos") 14. TX placebo$ 15. TX random$ 16. (MH "Study Design+") 17. (MH "Comparative Studies") 18. (MH "Evaluation Research") 19. (MH "Prospective Studies+") 20. TX (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$) 21. S1 or S2 or (…….) or S20 |

|

Search terms for Osteoarthritis 20. exp osteoarthritis/ 21. osteoarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 22. osteoarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 23. gonarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 24. gonarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 25. coxarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 26. coxarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 27. arthros$.ti,ab. 28. arthrot$.ti,ab. 29. ((knee$ or hip$ or joint$) adj3 (pain$ or ach$ or discomfort$)).ti,ab. 30. ((knee$ or hip$ or joint$) adj3 stiff$).ti,ab. |

Search terms for Osteoarthritis 17. exp osteoarthritis/ 18. osteoarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 19. osteoarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 20. gonarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 21. gonarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 22. coxarthriti$.ti,ab,sh. 23. coxarthro$.ti,ab,sh. 24. arthros$.ti,ab. 25. arthrot$.ti,ab. 26. ((knee$ or hip$ or joint$) adj3 (pain$ or ach$ or discomfort$)).ti,ab. 27. ((knee$ or hip$ or joint$) adj3 stiff$).ti,ab. |

Search terms for Osteoarthritis 22. osteoarthriti$ 23. (MH "Osteoarthritis") 24. TX osteoarthro$ 25. TX gonarthriti$ 26. TX gonarthro$ 27. TX coxarthriti$ 28. TX coxarthro$ 29. TX arthros$ 30. TX arthrot$ 31. TX knee$ n3 pain$ 32. TX hip$ n3 pain$ 33. TX joint$ n3 pain$ 34. TX knee$ n3 ach$ 35. TX hip$ n3 ach$ 36. TX joint$ n3 ach$ 37. TX knee$ n3 discomfort$ 38. TX hip$ n3 discomfort$ 39. TX joint$ n3 discomfort$ 40. TX knee$ n3 stiff$ 41. TX hip$ n3 stiff$ 42. TX joint$ n3 stiff$ 43. S22 or S23 or S24….or S42 |

|

Search terms for Doxycycline 31. exp doxycycline/ 32. doxycycline.tw. 33. deoxyoxytetracycline.tw. 34. hydramycin.tw. 35. vibramycin.tw. 36. vibravenos.tw. 37. oracea.tw. 38. adoxa.tw. 39. doryx.tw. 40. doxy$.tw. 41. monodox$.tw. 42. periostat.tw. 43. atridox.tw. 44. vibrox$.tw. |

Search terms for Doxycycline 28. exp doxycycline/ 29. doxycycline.tw. 30. deoxyoxytetracycline.tw. 31. hydramycin.tw. 32. vibramycin.tw. 33. vibravenos.tw. 34. oracea.tw. 35. adoxa.tw. 36. doryx.tw. 37. doxy$.tw. 38. monodox$.tw. 39. periostat.tw. 40. atridox.tw. 41. vibrox$.tw. |

Search terms for Doxycycline 44. (MH " Doxycycline ") 45. TX doxycycline 46. TX deoxyoxytetracycline 47. TX hydramycin 48. TX vibramycin 49. TX vibravenos 50. TX oracea 51. TX adoxa 52. TX doryx 53. TX doxy$ 54. TX monodox$ 55. TX periostat 56. TX atridox 57. TX vibrox$ 58. S44 or S45 or …. S57 |

|

Combining terms 45. or/1‐19 46. or/20‐30 47. or/31‐44 48. and/45‐47 49. animal/ 50. animal/ and human/ 51. 49 not 50 52. 48 not 51 53. remove duplicates from 52 |

Combining terms 42. or/1‐16 43. or/17‐27 44. or/28‐41 45. and/42‐44 46. animal/ 47. animal/ and human/ 48. 46 not 47 49. 45 not 48 50. remove duplicates from 49 |

Combining terms 59. S21 and S43 and S58 |

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

| CENTRAL |

|

Search terms for osteoarthritis #1. MeSH descriptor Osteoarthritis explode all trees #2. (osteoarthritis* OR osteoarthro* OR gonarthriti* OR gonarthro* OR coxarthriti* OR coxarthro* OR arthros* OR arthrot* OR ((knee* OR hip* OR joint*) near/3 (pain* OR ach* OR discomfort*)) OR ((knee* OR hip* OR joint*) near/3 stiff*)) in Clinical Trials Search terms for doxycycline #3. MeSH descriptor Doxycycline explode all trees #4. doxycycline in Clinical Trials #5. deoxyoxytetracycline in Clinical Trials #6. hydramycin in Clinical Trials #7. vibramycin in Clinical Trials #8. vibravenos in Clinical Trials #9. oracea in Clinical Trials #10. adoxa in Clinical Trials #11. doryx in Clinical Trials #12. doxy* in Clinical Trials #13. monodox* in Clinical Trials #14. periostat in Clinical Trials #15. atridox in Clinical Trials #16. vibrox* in Clinical Trials Combining terms #17. (#1 OR #2) #18. (#3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16) #19. (#17 AND #18) in Clinical Trials |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Doxycycline versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 2 | 524 | Std. Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.22, 0.13] |

| 2 Physical function | 2 | 517 | Std. Mean Difference (Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.07 [‐0.25, 0.10] |

| 3 Minimum joint space width | 1 | 361 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.15 [‐0.28, ‐0.02] |

| 4 Number of patients withdrawn due to adverse events | 2 | 663 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.28 [1.06, 4.90] |

| 5 Number of patients experiencing any adverse event | 1 | 232 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.36 [1.08, 1.72] |

| 6 Number of patients experiencing any serious adverse events | 2 | 663 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.68, 1.68] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Brandt 2005.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with 2 parallel groups Randomisation stratified by centre Trial duration: 30 months Multicentre trial including 6 centres No power calculation reported | |

| Participants | 431 participants with radiologically confirmed knee osteoarthritis were randomised Number of females: 431 (100%) Average age: 54.9 years Average BMI: 36.7 kg/m2 Severity of knee osteoarthritis: 59% with Kellgren/Lawrence grade 2 and 41% with Kellgren/Lawrence grade 3 Duration of knee complaints: not reported | |

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily Control intervention: placebo, twice daily Treatment duration: 30 months Analgesics other than study drugs allowed and intake was similar between groups | |

| Outcomes | Extracted pain outcome: 15.2 m (50‐feet) walking pain after 30 months

Extracted function outcome: WOMAC disability subscore after 30 months Primary outcome: joint space narrowing in the tibiofemoral compartment of the contralateral knee |

|

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00000403 The trial was supported by the a non‐profit organisation (NIH grants R01‐AR‐43348, P60‐AR‐20582 and R01‐AR‐44370). It is unclear whether this trial received funding from a commercial body |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Subjects (...) were randomly assigned" Comment: no mention of the mechanism used for sequence generation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were allocated randomly to treatment groups in blocks of 6" Comment: no mention of concealment of allocation |

| Blinding of patients described? | Low risk | Quote: "matched placebo" Comment: indistinguishable interventions and the description of a double‐blind phase implies blinding of participants |

| Blinding of physicians? | Low risk | Comment: clearly distinguished between single blind run‐in period and double‐blind phase. Blinding of physicians probable |

| Blinding of outcome assessors? | Low risk | Comment: depending on the outcome, participants or physicians were the assessors, both of which were blinded |

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis? All outcomes | High risk | Pain outcome: 69 of 218 participants (32%) excluded in experimental group and 55 of 213 participants (26%) excluded in control group Function outcome: 69 of 218 participants (32%) excluded in experimental group and 55 of 213 participants (26%) excluded in control group |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: there were 2 instruments (SF‐36 and Pain at rest) assessed during the trial but that results were not available in any of the trial reports. These instruments were identified in the trial registration and a multiple trial report (Mazzuca et al. 2004). Trial registration occurred after trial main report (Brandt et al. 2005) was published |

| Funding by commercial body avoided? | Unclear risk | No information provided regarding funding from commercial body |

Snijders 2011.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial with 2 parallel groups, using an allocation ratio of 1:1 Randomisation stratified by pain intensity at screening visit, using stratified block randomisation Trial duration: 6.1 months Single‐centre trial Power calculation reported | |

| Participants | 232 participants with radiologically confirmed knee osteoarthritis were randomised Number of females: 154 (66%) Average age: 59 years Average BMI: 30 kg/m2 Severity of knee osteoarthritis: 65% with Kellgren/Lawrence grade 2 and 35% with Kellgren/Lawrence grade 3 Duration of knee complaints: 6 years | |

| Interventions | Experimental intervention: doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily Control intervention: placebo twice daily Treatment duration: 5.6 months (24 weeks) Analgesics other than study drugs allowed up to 48 hours or four times the drug's half‐life, or both, before study visits for outcome assessment. Opioids other than tramadol were not allowed. Analgesics intake was similar between groups |

|

| Outcomes | Extracted pain outcome: WOMAC pain subscore after 5.6 months Extracted function outcome: WOMAC disability subscore after 5.6 months Primary outcome: proportion responders according to the OMERACT‐OARSI response criteria |

|

| Notes | Dutch Trial Register identifier (www.trialregister.nl): NTR1111

All statistical analyses were performed blinded for treatment allocation It is unclear whether this trial received funding from a commercial body |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "an independent pharmacist used a computer‐generated, blinded randomisation list to assign patients randomly to doxycycline or placebo" Comment: randomisation list was computer generated |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "an independent pharmacist used a computer‐generated, blinded randomisation list to assign patients randomly to doxycycline or placebo" and "allocation data were stored at the hospital pharmacy in sealed envelopes that could be opened in the case of medical need" Comment: allocation conducted by independent pharmacist using blinded randomisation list, the list was stored centrally, the treating physician had no access do the randomisation list |

| Blinding of patients described? | Low risk | Quote: "the allocation was blinded for patient and study physician using placebo medication capsules, blue and white, with the same appearance as verum" and "triple‐blind, placebo controlled trial" Comment: indistinguishable interventions, the description of a triple‐blind phase implies blinding of participants, participants explicitly reported as blinded |

| Blinding of physicians? | Low risk | Quote: "the allocation was blinded for patient and study physician using placebo medication capsules, blue and white, with the same appearance as verum" and "triple‐blind, placebo controlled trial" Comment: indistinguishable interventions, study physician explicitly reported as blinded, and trial reported as triple‐blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessors? | Low risk | Comment: depending on the outcome, participants or physicians were the assessors, both of which were blinded |

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis? All outcomes | High risk | Pain outcome: 8 of 116 participants (7%) excluded in experimental group and 6 of 116 participants (5%) excluded in the control group Function outcome: 13 of 116 participants (11%) excluded in experimental group and 9 of 116 participants (8%) excluded in control group The authors considered lost to follow‐up to be "missing not at random" owing to selective lost to follow‐up in the doxycycline trial arm, owing to adverse events |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | Comment: all outcomes mentioned in the methods section are addressed in the results section, no discrepancies were detected between entrees for NTR1111 at www.trialregister.nl, the full‐text publication, and the published abstract in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases |

| Funding by commercial body avoided? | Unclear risk | Quote: "the authors thank Dr BJF van den Bemt for study medication supply" Comment: no information provided regarding financial support |

BMI: body mass index; SF‐36: 36‐item short form; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by year of study]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Brandt 1995 | Animal study |

| Smieja 2001 | No participants in osteoarthritis |

Differences between protocol and review

Because only two studies were included in our review, we did not perform stratified analyses or funnel plot evaluation to investigate whether potential variation between trials could be explained by biases affecting individual trials or by publication bias. We did not include the electronic database CINAHL in our search update since, in our previous search, this database did not identify any additional hits. Finally, we did not include the OARSI database in our search update as we no longer had access to this database.

Contributions of authors

Protocol completion: Nüesch, Rutjes, Reichenbach, Jüni Acquisition of data: da Costa, Nüesch, Rutjes Analysis and interpretation of data: da Costa, Nüesch, Reichenbach, Jüni, Rutjes Manuscript preparation: da Costa, Nüesch, Reichenbach, Jüni, Rutjes Statistical analysis. da Costa, Nüesch, Rutjes

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University or Bern, Switzerland.

Intramural grants

External sources

-

Swiss National Science Foundation, Switzerland.

National Research Program 53 on musculoskeletal health (grant numbers 4053‐40‐104762/3 and 3200‐066378)

-

ARCO Foundation, Switzerland.

Research program on knee and hip osteoarthritis

Declarations of interest

None.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Brandt 2005 {published and unpublished data}

- Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA. Experience with a placebo‐controlled randomized clinical trial of a disease‐modifying drug for osteoarthritis: the doxycycline trial. Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America 2006;32(1):217‐34, xi‐xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Katz BP, Lane KA, Buckwalter KA, Yocum DE, et al. Effects of doxycycline on progression of osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2005;52(7):2015‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakr R, Brandt KD, Ang DC, Mazzuca SA. Varus malalignment diminishes the structure‐modifying effects of doxycycline (doxy) in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2009;60(Suppl 10):829. [Google Scholar]

- Hellio Le Graverand MP, Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Katz BP, Buck R, Lane KA, et al. Association between concentrations of urinary type II collagen neoepitope (uTIINE) and joint space narrowing in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006;14(11):1189‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Chakr R, Lane KA. Varus malalignment negates the structure‐modifying benefits of doxycycline in obese women with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2010;18(8):1008‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Lane KA, Bradley JD, Heck LW, et al. Subject retention and adherence in a randomized placebo‐controlled trial of a disease‐modifying osteoarthritis drug. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2004;51(6):933‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Lane KA, Buckwalter KA. Comparison of quantitative and semiquantitative indicators of joint space narrowing in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2006;65(1):64‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Lane KA, Chakr R. Malalignment and subchondral bone turnover in contralateral knees of overweight/obese women with unilateral osteoarthritis: implications for bilateral disease. Arthritis Care & Research 2011;63(11):1528‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Schauwecker DS, Katz BP, Meyer JM, Lane KA, et al. Severity of joint pain and Kellgren‐Lawrence grade at baseline are better predictors of joint space narrowing than bone scintigraphy in obese women with knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Rheumatology 2005;32(8):1540‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Snijders 2011 {published data only}

- Snijders GF, Ende CH, Riel PL, Hoogen FH, Broeder AA. Doxycycline has no symptom modifying effects in knee osteoarthritis: results from a randomized placebo controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2011; Vol. 70, issue Suppl 3:140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Snijders GF, Ende CH, Riel PL, Hoogen FH, Broeder AA. The effects of doxycycline on reducing symptoms in knee osteoarthritis: results from a triple‐blinded randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2011;70(7):1191‐6. [PUBMED: 21551510] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissel JT. Placebo controlled study on the effect of 6 months treatment with doxycycline on pain and function in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee [Placebo gecontroleerd onderzoek naar het effect van 6 maanden behandeling met doxycycline op pijn en functie in patiënten met artrose van de knie]. Nederlands Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/index.asp) 2007.

References to studies excluded from this review

Brandt 1995 {published data only}

- Brandt KD. Modification by oral doxycycline administration of articular cartilage breakdown in osteoarthritis. Journal of Rheumatology 1995;22(Suppl 43):149‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smieja 2001 {published data only}

- Smieja M, MacPherson DW, Kean W, Schmuck ML, Goldsmith CH, Buchanan W, et al. Randomised, blinded, placebo controlled trial of doxycycline for chronic seronegative arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2001;60(12):1088‐94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Altman 1996

- Altman R, Brandt K, Hochberg M, Moskowitz R, Bellamy N, Bloch DA, et al. Design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with osteoarthritis: recommendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. Results from a workshop. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1996;4(4):217‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buckland‐Wright 1995

- Buckland‐Wright JC, Macfarlane DG, Williams SA, Ward RJ. Accuracy and precision of joint space width measurements in standard and macroradiographs of osteoarthritic knees. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1995;54(11):872‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chinn 2000

- Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta‐analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2000;19(22):3127‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clegg 2006

- Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, Klein MA, O'Dell JR, Hooper MM, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;354(8):795‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cohen 1988

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Edition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

da Costa 2012

- Costa BR, Rutjes AWS, Johnston BC, Reichenbach S, Nüesch E, Tonia T, Gemperli A, Guyatt G, Jüni P. Methods to convert continuous outcomes into odds ratios of treatment response and numbers needed to treat: meta‐epidemiological study. International Journal of Epidemiology 2012; Vol. 41, issue 5:1445‐59. [DOI] [PubMed]

Dickersin 1994

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. BMJ 1994;309(6964):1286‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dieppe 2005

- Dieppe P. Disease modification in osteoarthritis: are drugs the answer?. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2005;52(7):1956‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 2001

- Egger M, Smith GD. Principles of and procedures for systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG editor(s). Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta‐Analysis in Context. London: BMJ Books, 2001:23‐42. [Google Scholar]

Egger 2003

- Egger M, Juni P, Bartlett C, Holenstein F, Sterne J. How important are comprehensive literature searches and the assessment of trial quality in systematic reviews? Empirical study. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2003;7(1):1‐76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

European Commission 2010

- European Commission. Guidelines on Medical Devices. Clinical Investigations: Serious Adverse Event Reporting Under Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC, 2010. ec.europa.eu/health/medical‐devices/files/meddev/2_7_3_en.pdf. (accessed 7 October 2012).

Golub 1993

- Golub LM, Ramamurthy NS, McNamara TF, Greenwald RA, Kawai T, Hamasaki T, et al. inventors, Kuraray Co, Ltd. assignee. Method to reduce connective tissue destruction. United States patent 5,258,371 Nov 3, 1993.

Greenwald 1994

- Greenwald RA. Treatment of destructive arthritis disorders with MMP inhibitors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1994;731:181‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck‐Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. GRADE: what is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians?. BMJ 2008;336:995‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2011

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso‐Coello P, Rind D, et al. GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence ‐ imprecision. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011;64:1283‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gøtzsche 2007

- Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A, Maric K, Tendal B. Data extraction errors in meta‐analyses that use standardized mean differences. JAMA 2007;298(4):430‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hellio 2009

- Hellio Le Graverand‐Gastineau MP. OA clinical trials: current targets and trials for OA. Choosing molecular targets: what have we learned and where we are headed?. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17(11):1393‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Juni 2001

- Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001;323(7303):42‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Juni 2006

- Juni P, Reichenbach S, Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: rational approach to treating the individual. Best Practice and Research. Clinical Rheumatology 2006;20(4):721‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lequesne 1995

- Lequesne M. Quantitative measurements of joint space during progression of osteoarthritis: chondrometry. In: Kuettner K, Goldberg V editor(s). Osteoarthritic Disorders. Rosemont (IL): American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1995:427‐44. [Google Scholar]

Mazzuca 2006

- Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Lane KA, Buckwalter KA. Comparison of quantitative and semiquantitative indicators of joint space narrowing in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2006;65(1):64‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Merle‐Vincent 2007

- Merle‐Vincent F, Vignon E, Brandt K, Piperno M, Coury‐Lucas F, Conrozier T, et al. Superiority of the Lyon schuss view over the standing anteroposterior view for detecting joint space narrowing, especially in the lateral tibiofemoral compartment, in early knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2007;66(6):747‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nuesch 2009a

- Nuesch E, Rutjes AW, Husni E, Welch V, Juni P. Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;7(4):CD003115. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub3; PUBMED: 19821302] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nuesch 2009c

- Nuesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Rutjes AWS, Burgi E, Scherer M, et al. The effects of the exclusion of patients from the analysis in randomised controlled trials: meta‐epidemiological study. BMJ 2009;339:b3244. [DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b3244; PUBMED: 19736281] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ornetti 2009

- Ornetti P, Brandt K, Hellio‐Le Graverand MP, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kloppenburg M, et al. OARSI‐OMERACT definition of relevant radiological progression in hip/knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2009;17(7):842‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pham 2004

- Pham T, Heijde D, Altman RD, Anderson JJ, Bellamy N, Hochberg M, et al. OMERACT‐OARSI initiative: Osteoarthritis Research Society International set of responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12(5):389‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pogue 1997

- Pogue JM, Yusuf S. Cumulating evidence from randomized trials: utilizing sequential monitoring boundaries for cumulative meta‐Analysis. Controlled Clinical Trials 1997;18:580‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reichenbach 2007

- Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M, Trelle S, Burgi E, Burgi U, et al. Meta‐analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Annals of Internal Medicine 2007;146(8):580‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reichenbach 2010

- Reichenbach S, Rutjes AW, Nuesch E, Trelle S, Juni P. Joint lavage for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;12(5):CD007320. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007320.pub2; PUBMED: 20464751] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2011 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre. The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Rubin 2000

- Rubin BK, Tamaoki J. Macrolide antibiotics as biological response modifiers. Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs 2000;1(2):169‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rucker 2008

- Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I(2) in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2008;8(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutjes 2009a

- Rutjes AW, Nuesch E, Sterchi R, Kalichman L, Hendriks E, Osiri M, et al. Transcutaneous electrostimulation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;7(4):CD002823. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002823.pub2; PUBMED: 19821296] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutjes 2009b

- Rutjes AW, Nuesch E, Reichenbach S, Juni P. S‐Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;7(4):CD007321. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007321.pub2; PUBMED: 19821403] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutjes 2010

- Rutjes AW, Nuesch E, Sterchi R, Juni P. Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;20(1):CD003132. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003132.pub2; PUBMED: 20091539] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rutjes 2012

- Rutjes AW, Jüni P, Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine 2012;157(3):180‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shapiro1997

- Shapiro LE, Knowles SR, Shear NH. Comparative safety of tetracycline, minocycline, and doxycycline. Archives of Dermatology 1997;133(10):1224‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shlopov 1999

- Shlopov BV, Smith GN Jr, Cole AA, Hasty KA. Differential patterns of response to doxycycline and transforming growth factor beta1 in the down‐regulation of collagenases in osteoarthritic and normal human chondrocytes. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1999;42(4):719‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1996

- Smith GN Jr, Brandt KD, Hasty KA. Activation of recombinant human neutrophil procollagenase in the presence of doxycycline results in fragmentation of the enzyme and loss of enzyme activity. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1996;39(2):235‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Towheed 2005

- Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Anastassiades TP, Shea B, Houpt J, Robinson V, et al. Glucosamine therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005;18(2):CD002946. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002946.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vlad 2007

- Vlad SC, LaValley MP, McAlindon TE, Felson DT. Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: why do trial results differ?. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2007;56(7):2267‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wandel 2010

- Wandel S, Juni P, Tendal B, Nuesch E, Villiger PM, Welton NJ, et al. Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta‐analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2010;341:c4675. [PUBMED: 20847017] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yu 1992

- Yu LP Jr, Smith GN Jr, Brandt KD, Myers SL, O'Connor BL, Brandt DA. Reduction of the severity of canine osteoarthritis by prophylactic treatment with oral doxycycline. Arthritis and Rheumatism 1992;35(10):1150‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2011

- Zhang Y, Nevitt M, Niu J, Lewis C, Torner J, Guermazi A, Roemer F, McCulloch C, Felson DT. Fluctuation of knee pain and changes in bone marrow lesions, effusions, and synovitis on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2011;63(3):691‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Nuesch 2009b

- Nuesch E, Rutjes AW, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Juni P. Doxycycline for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009;7(4):CD007323. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007323.pub2; PUBMED: 19821404] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]