Abstract

The sorghum inflorescence is consisted of sessile (SS) and pedicellate spikelets (PS). Commonly, only SS could produce seeds and each spikelet produces one single seed. Here, we identified a sorghum mutant, named Double-grain (Dgs), which can produce twin seeds in each pair of glumes. We characterized the developmental process of inflorescence in Dgs and Jinliang 5 (Jin5, a single-seeded variety) using scanning electron microscope (SEM). The results showed that at the stamen and pistil differentiation stage, Dgs could develop two sets of stamens and carpels in one sessile floret, which resulted in twin-seeded phenotype in Dgs. Two F2 mapping populations derived from the cross between Jin5 and Dgs, and BTx622B and Dgs, were constructed, respectively. The genetic analysis showed that Dgs trait was controlled by a single dominant gene. Through bulk segregation analysis with whole-genome sequencing (BSA-seq) and linkage analysis, Dgs locus was delimited into a region of around 210-kb on chromosome 6, between the markers SSR24 and SSR47, which contained 32 putative genes. Further analysis indicated that Sobic.006G249000 or Sobic.006G249100 may be responsible for the twin-seeded phenotype. This result will be useful for map-based cloning of the Dgs gene and for marker-assisted breeding for increased grain number per panicle in sorghum.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11032-024-01511-7.

Keywords: Sorghum, Double-grain, Fine mapping, SEM

Introduction

Grass spikelets are important reproductive organs, consisting of glumes (bract-like organs) and florets. Spikelets affect grain number per panicle (GNP), which is a major determinant of grain yield in cereal crops including sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench] (Foulkes et al. 2011; Sreenivasulu and Schnurbusch 2012). Spikelet morphogenesis therefore plays an important role in determining crop yield. Thus, the genetic control of the inflorescence morphogenesis is very vital in cereal crops because it directly affects grain yield. However, little is known about how GNP of sorghum is determined.

In sorghum, the panicle (inflorescence) contains a main rachis with primary branches, secondary branches and tertiary branches. The secondary branches and tertiary branches grow from the primary branches (Brown et al. 2006). Spikelets on the branches develop in pairs, with the sessile fertile (SS) fertile and perfect and the pedicellate spikelets (PS) sterile. Terminal spikelets, consists of one sessile fertile perfect spikelet and two sterile pedicellate spikelets (Walters and Keil. 1988; Bell 2008; Kellogg 2015). Sessile spikelets were directly attached to branches, including primary, secondary, and tertiary branches, while pedicellate spikelets connected to the branches by a short pedicel. Usually each SS of sorghum could produce single seed enclosed by two glumes and no seed on PS. There were few sorghum grain mutants which were caused by the PS mutation. A novel class of multi-seeded sorghum mutants including msd1, msd2 and msd3, of which PS could produce viable seeds, was reported (Burow et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017; Dampanaboina et al. 2019; Gladman et al. 2019). Based on scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis, the panicle development showed no differences in panicle architecture between wild-type (WT) and msd1 mutant before floral transition stage when ovary and stamen primordia started (Jiao et al. 2018). However, PS arrested in WT at floral stage 1 (when the length of inflorescence is 1–3 mm) and both anthers and pistil were aborted in the PS of WT at floral stage 2 (when the length of inflorescence is 3–5 mm). While the PS continued to develop in msd1 at floral stage 1 and complete floral organs developed in both SS and PS of msd1. It was found that floral organs started to develop in both SS and PS of WT, but that the development of PS sexual organ stopped early on, and this suppression of development of floral organs was relieved in PS of msd1 plants during inflorescence development (Jiao et al. 2018). MSD1 was identified as a TCP (Teosinte branched/Cycloidea/PCF) transcription factor, which regulates mRNA levels of jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthetic genes. JA level in young msd1 panicles decreases 50% compared with WT panicles. Application of exogenous JA at floral development stage 3 (when the length of inflorescence is 5–15 mm) or earlier can rescue the phenotype of msd1 mutant (Jiao et al. 2018).

In addition to multiple seeds derived from PS, abnormal spikelets could produce multiple seeds, such as twin seeds or triplets in one glume. Several twin-seeded and triple-seeded mutants were observed in a milo-feterita hybrid but this abnormalities were not expressed in the following generation (Cron 1916). In twin-seeded spikelet, both grains of the pair in one glume are usually of same size; however, one of them is sometimes slightly larger. Karper (1931) reported twin-seeded and triple-seeded spikelets in White milo and Yellow milo. Additionally, coalesced twin seeds were frequently present in White milo and Yellow milo. Several durra varieties from India also displayed twin seeds and this twin-seeded character was simply inherited dominantly (Karper and Stephens 1936). A twin-seeded accession, P.I.14610 was crossed with Kafir-60, Ks24 and Redlan to develop isogenic inbred lines. The results showed that twin seed decreased seed weight but increased number of seeds per panicle. However no yield advantage was observed in the same study (Casady and Ross 1977).

Mutations in the number of floral organs, especially the number of pistils, resulting in the change of grain numbers, have also been reported in Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.). Several genes controlling meristem function have been identified. The stem cell identity of Arabidopsis in the shoot apical meristem (SAM) is regulated a feedback loop consisting of the CLAVATA (CLV) and WUSCHEL (WUS) genes. WUS, encoding a novel homeodomain transcription factor, is expressed in the organizing center of SAM and maintain the identity of the stem cells (Mayer et al. 1998). Loss-of-function mutants of WUS showed premature termination of both SAM and floral meristems (FM) (Laux et al. 1996). The CLE family is plant-specific gene and named after its founding members CLAVATA3 (CLV3) from Arabidopsis (Fletcher et al. 1999) and EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (ESR) from maize (Opsahi-ferstad et al. 1997). CLE genes encode small secreted proteins containing CLE domain which is plant-specific conserved (Jun et al. 2008). Mutations in CLV (CLV1, CLV2, and CLV3) genes displayed opposite phenotypes to that of wus, which have increased SAM and delayed organ initiation (Clark et al. 1997; Kayes and Clark 1998; Fletcher et al. 1999). It was reported that the expression of CLV3 was regulated by WUS via a negative feedback loop (Brand et al. 2002). The expression of WUS in clv mutants increased, indicating that the CLV proteins negatively regulate WUS expression. Thus, stem cell identity is regulated by the interaction between WUS and CLV.

The CLV signaling pathway for regulating SAM maintenance, FM size and floral organ number is conserved in rice, which is elucidated in a serial of FON (FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER) mutants (fon1-fon4). FON1 encoding a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase, an ortholog of CLV1 in Arabidopsis, has been shown to regulate FM size in rice. Mutation in FON1 results in an increased number of floral organs, such as stamen and pistils (Suzaki et al. 2004). In multi-floret spikelet 3 (mfs3) mutant, the palea was substitute with extra floral organs in some spikelets (Zheng et al. 2019). The expression of REP, OsMADS1 and FON1 genes decreased and OsIDS1 and SNB genes increased in mfs3 mutant, indicating that the MFS3 gene might modulate spikelet meristem determinacy and palea identity through controlling the expression of these related genes (Zheng et al. 2019).

FON2 in rice encodes a small secreted protein with a CLE domain. Mutations in FON2 cause the enlargement of the FM and an increased number of floral organs, while the vegetative and inflorescence are basically normal (Suzaki et al. 2006). FON2 can interact with FON1 to regulate the number of floral organs in rice (Suzaki et al. 2006). Another CLV3 protein FON2 SPARE1 (FOS1) has been confirmed to regulate stem-cell proliferation in rice FM and maintenance of the SAM in the vegetative stage (Suzaki et al. 2009). Constitutive expression of FOS1 resulted in termination of the vegetative SAM. Genetic analysis indicated that FOS1 could function without FON1, the putative receptor of FON2, suggesting that FOS1 and FON2 may function in maintaining meristem as signaling molecules in independent regulation pathways (Yoshida and Nagato 2011). fon4 mutant, allelic to fon2, displayed enlarged embryonic and vegetative SAMs, the inflorescence and FMs (Chu et al. 2006; Suzaki et al. 2006). Subsequently, fon4 mutants developed thick culms and increased numbers of both primary rachis branches and floral organs finally twin seeds in the one pair of glumes. Rice twin-grain1 (tg1) mutant, allelic to FON2/FON4, contains more than one pistil in each spikelet and develops multiple seeds in the glumes (Ye et al. 2017).

The rice fon3 mutant showed increased floral organ, especially the number of pistils (Jiang et al. 2005). Due to a paracentric inversion, genetic recombination at the FON3 locus was suppressed with breakpoints corresponding to sequence gaps on rice chromosome 11L (Jiang et al. 2007). The relationship of fon3 with other similar rice mutants such as fon1 and fon2/4 is unclear.

Molecular genetic studies of these mutants with increased floral organ have advanced our understanding of flower development in rice and Arabidopsis (Yoshida and Nagato 2011). We found a spontaneous double-grain mutant Dgs in sorghum and carried out genetic analysis and preliminarily mapped the Dgs gene on chromosome 6 of sorghum in a previous study (Zhou et al. 2022). In this study, we characterized the floral development of double-grain mutant Dgs using SEM; analyzed the inheritance of double-grain mutant Dgs using two biparental mapping populations; further fine mapped the Dgs locus to approximately 210 kb on chromosome 6 using BSA-seq and linkage analysis; and analyzed the 32 predicted genes in the candidate chromosome regions and speculated that Sobic.006G249100 might be responsible for the twin-seeded phenotype.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and genetic analysis

The Dgs mutant was a spontaneous mutant and found accidentally in the germplasm field. The background was unclear. Jin5 was a popular sorghum restorer line in China, whose derived lines account for 20% sorghum restoration lines in China. BTx622B was a single-seeded cultivar introduced from USA to China. To identify the causal gene of double-grain in Dgs, the Dgs was crossed with two common single-seeded sorghum cultivars, Jin5 and BTx622B, respectively, to produce F2 segregating populations. At growing season, data for important agronomic traits from Dgs and Jin5, including heading date, panicle length, grain number per panicle, number of primary branch and secondary branch, grain weight, grain width, and 1000 grain weight were collected from 15 plants, respectively. Individuals with single-seeded phenotype from these two F2 populations were used for validation and fine mapping of the Dgs locus, respectively. Segregation ratio was tested for goodness of fit to a 3:1 ratio using chi-square test using R (R Core Team 2015) in the two F2 segregating populations, respectively. The statistical comparisons of the data for agronomic traits were performed by Student’s t-test using R (R Core Team 2015).

Morphological and histological analysis of Dgs

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis followed Zhu et al.’s (2010) method with slight modification. Briefly, samples at the reproductive growth stage were dissected from 9–11 weeks old, field-growing plants. To obtain the developing inflorescence, which was the shoot apical meristem (SAM) transiting from vegetative growth to reproductive growth stage, the leaves were carefully removed with bare hand one by one. The tender inflorescence, which was ranging from around 0.1 cm to 2 cm in length, was excised from the tip of plants and then immediately fixed in FAA fixative solution with formalin: glacial acetic acid: 70% ethanol at 1:1:18 at 4 °C for 12 h. After dehydrated in each of 70%, 83%, 95%, 100% ethanol and 100% ethanol for 1 h, respectively, the fixed samples were critical-point dried, sputter-coated with gold, and photographed under a SEM (S-4000; Hitachi, Tokyo) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

Library preparation and re-sequencing

The twin-seeded bulk (T bulk) and single-seeded bulk (S bulk) were constructed by pooling 60 plants exhibiting twin-seeded phenotype and single-seeded phenotype from the F2 population derived from the cross of Jin5 × Dgs, respectively. DNA from both parents and two bulks was extracted from fresh leaves at seedling stage using Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit Catalog No.DP305-03 (TIANGEN, China) and were delivered to BioMarker Company (Beijing, China) for library construction and the paired-end 150-bp reads were generated by sequencing the libraries on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform.

Analysis of re-sequencing data and QTL-seq analysis

The paired-end reads of Dgs, Jin5, T bulk and S bulk were aligned to the Sorghum bicolor reference genome version 3.1.1 (McCormick et al. 2018) using BWA software (Li 2013) with the method “mem” (Li 2013). SAMtools (Li et al. 2009) was then applied to call the SNP and InDel variants from the aligned reads of Dgs and Jin5. Low quality (Q < 10, DP < 5), multi-allelic, or heterozygous variants in the VCF files of Dgs and Jin5 were filtered out using BCFtools (Narasimhan et al. 2016). Finally, polymorphic SNP and InDel between Dgs mutant and Jin5 were searched from the datasets. Then, the genotypes of these screened polymorphic loci were called out from the aligned reads of the two bulks, S bulk and T bulk. To perform the SNP/InDel based analysis, windowed scans for Dgs gene were carried out by next generation sequencing bulked segregant analysis (NGS-BSA) (Takagi et al. 2013) using the package QTLseqr in R (Mansfeld and Grumet 2018). Polymorphic SNPs/InDdels from all 10 chromosomes of sorghum were analyzed in each single analysis for both T bulk and S bulk. The window bandwidth size was 1 Mb, and the simulations were bootstrapped 10,000 times. The FDR was set to p < 0.001 based on the method of Benjamini and Hochberg with adjustment (Benjamini and Hochberg 1997). SNP/InDel index at a certain position in a chromosome is obtained by dividing the counts of alternate base by the number of reads aligned. Then Δ(SNP/InDel-index) was obtained by subtracting SNP/InDel index of S bulk from SNP/InDel index of T bulk. The Δ(SNP/InDel-index) index was regarded as the genomic difference between T bulk and S bulk. G’ values and -log10 (p) values were calculated using the tricubeStat function and p.adjust function in the QTLseqr R package, respectively, to determine statistical significance of candidate Dgs gene. Plots were produced with a 1 Mb sliding window using the ΔSNP index, G’ values and -log10 (p) values.

Fine-mapping of Dgs

According to the result of BSA-seq analysis, InDel markers were developed based on the polymorphic InDel markers derived from the SNP and InDel calling VCF files. SSR sites were also searched through the Dgs region using the sorghum reference genome version 3.1.1 (McCormick et al. 2018) and SSR markers were developed. All primers were sent to the Shanghai Invitrogen Company (Shanghai, China) for synthesis. The single-seeded individual plants in the F2 populations derived from the cross of Jin5 × Dgs were subjected to genotyping with the polymorphic markers by 4.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

RNA isolation, semi-quantitative analysis and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

RNA was isolated from the root, stem, leaf blade, inflorescence, young inflorescence of sorghum using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The synthesis of cDNA was carried out using 1 μg of total RNA and HiScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). RT-PCR analysis was performed with 1 µl cDNA and gene-specific primers for Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100. SbActin1 was used as an internal control. All primers used in this research are listed in the Supplementary Table S1. RT-qPCR was carried out to validate the expression of Sobic.006G249100 in Dgs mutant and Jin5 using AceQ® qPCR SYBR® Green Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) in 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (ABI, USA) with three replicates. The 2−△△Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001) was used for the analysis of relative gene expression.

Results

The Dgs mutant displays twin-grains phenotype in each pair of glumes

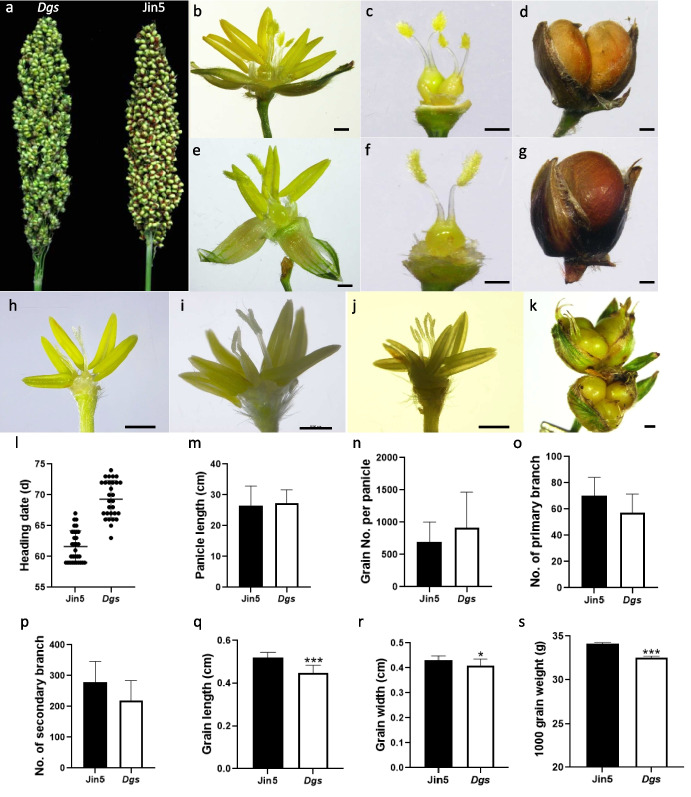

The Dgs germplasm could produce twin kernels in one pair of glumes of the sessile spikelet (Fig. 1a, d). There was no significant difference in the panicle length between Dgs mutant and Jin5 (Fig. 1a, m). The morphology of stamens, carpels and filled grains of Dgs and Jin5 were observed and photographed under a stereoscope (Leica, Germany). It could be clearly seen that there were six stamens and two carpels with plumose stigma in each fertile floret on SS in Dgs (Fig. 1b-c), while three stamens and one carpel in Jin5 (Fig. 1e-f). Both of the two carpels in Dgs are fertile and could develop into full-filled grains with germinating ability, resulting two kernels in one glume (Fig. 1d). The two grains were mostly the same size; however, one of them was sometimes smaller than the other grain. In contrast, there was only one kernel on the SS of Jin5 (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

Morphology and agronomic traits of Dgs mutant. a the morphology of the panicle of Dgs and Jin5; (b) and (e) sessile florets of Dgs mutant and Jin5; (c) and (f) carpels in one floret of Dgs mutant and Jin5; (d) and (g) seeds in each sessile spikelet of Dgs mutant and Jin5; (h) sessile floret with five stamens and two carpels in Dgs mutant; (i) sessile floret with seven stamens and two carpels in Dgs mutant; (j) sessile floret with six stamens and three carpels in Dgs; (k) the triple seeds in one pair of glume in Dgs mutant. Scale bars = 1 mm; (l)-(s) analysis of agronomic traits in Dgs mutant and Jin5. l heading date; (m) panicle length; (n) grain number per panicle; (o) No. of primary branch; (p) No. of secondary branch; (q) grain length; (r) grain width; (s) 1000 grain weight. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 15). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences by Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001)

Occasionally, there were florets with five or seven stamens and two carpels in the SS florets of Dgs mutant (Fig. 1h-i). Florets with three carpels were also observed in SS florets of Dgs mutant (Fig. 1j) and subsequently triple-seeded kernels in one pair of glumes were also observed at grain-filling stage or mature stage (Fig. 1k).

Grain number per panicle and other agronomic traits directly affects grain yield potential. Therefore the agronomic traits of Dgs mutant and Jin5 were collected. The flowering date of Dgs was 5 days later than Jin5 (Fig. 1l). The panicle length was slightly increased in Dgs (Fig. 1m). The grain number per panicle of Dgs was increased by approximately 38% compared with Jin5 (Fig. 1n). There were significant differences in few agronomic traits between the Dgs and Jin5. The number of primary and secondary branch per panicle was significantly lower in Dgs than in Jin5, Which decreased 25% and 27% in Dgs mutant, respectively (Fig. 1o-p). The grain length and width of Dgs were significantly lower than those of Jin5 (Fig. 1q-r), which were reduced by 4.7% and 14.0% in Dgs compared with Jin5. Moreover, the weight of 1000-grain in Dgs was decreased by 3.5% compared with Jin5 (Fig. 1s). Importantly, due to the increased grain number in Dgs mutant, the grain weight per panicle in Dgs was significantly increased compared with Jin5 (by approximately 21.3%).

The Dgs mutation induced two carpels during early spikelet development

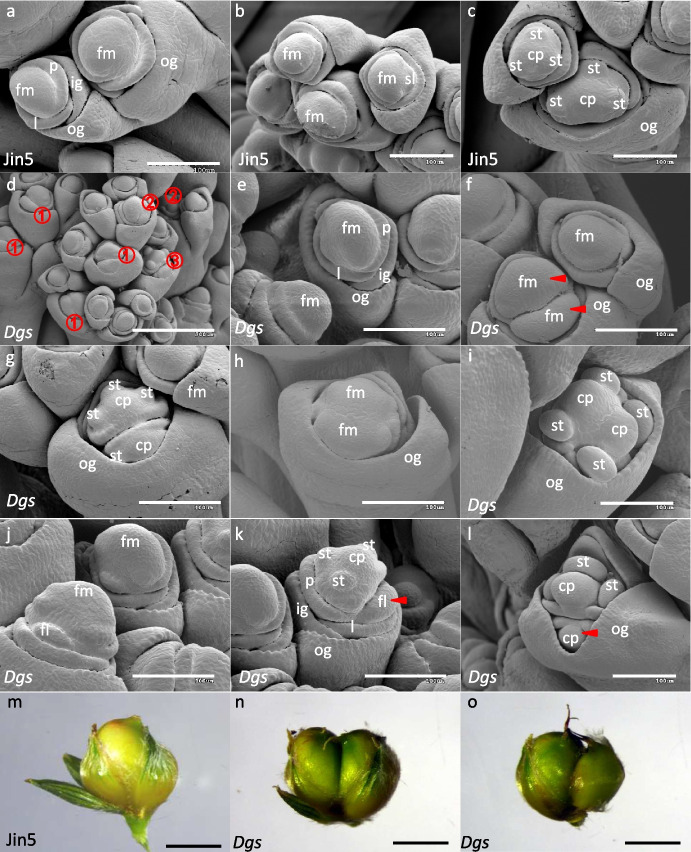

We examined the floral developmental processes of Dgs mutant and Jin5’s panicles using SEM. At early inflorescence developmental stages, the establishment of rachis meristem, the formation of primary, secondary, and tertiary branch primordia and the differentiation of spikelets in Dgs (Fig. S1a-f) were similar to those observed in Jin5 (Fig. S1g-i).

The difference between Dgs and Jin5 which finally determined the twin-seeded trait in Dgs was first observed during the stamen and pistil differentiation stage. Three stamen primordia formed on the edge of floret primordium and carpel primordium formed in the center of floret primordium in Jin5 (Fig. 2a-c), and finally a single grain set in a floret (Fig. 2m). In contrast, the development of the floral organ displayed complicated patterns in Dgs mutant. There were three patterns of stamen and pistil differentiation from the floret meristem in Dgs mutant (Fig. 2d, indicated by ①, ② and ③). The first pattern was that the top of fertile floret primordium (Fig. 2e) was developed into two halves of different sizes in Dgs mutant (Fig. 2f, indicated by arrows). Then each side of the two halves formed three protuberant stamen primordia (st) and the center formed carpel primordium (cp) (Fig. 2g). The second pattern was that the floral primordium expanded (Fig. 2h). Six protuberant stamen primordia differentiated symmetrically on the edge of the floret primordium with three stamen primordia on each side (Fig. 2i). And two carpel primordia formed on the center of each half of floret primordium surrounded by the stamen primordia (Fig. 2i). The third pattern was like that the top of the floret primordium formed three protuberant stamen primordia (Fig. 2j-l), and a new bulge, also called fertile lemma (fl), developed from the base of the floral primordium (Fig. 2k, indicated by arrows). Then another set of three stamen primordia and one carpel primordium was formed on the new bulge (Fig. 2l, indicated by arrows). From the overview images of inflorescence at pistil and stamen differentiation stage, it could be clearly seen that the first and second patterns were the major patterns in Dgs mutant (Fig. 2g, indicated by ① and ②). There was no significant difference in the grain size of the twin seeds in one pair of glumes in Dgs mutant for the first and second patterns (Fig. 2n). However, the grain sizes of the two grains in one pair of glumes differentiated in the third pattern were significantly different, with the first developing grain was significantly larger than the later developing grain (Fig. 2o).

Fig. 2.

Differentiations of stamen and pistil (carpel) and the formation of grains in Dgs mutant and Jin5. a-c Stamen and pistil differentiation of Jin5. d-l Stamen and pistil differentiation of Dgs mutant; m Grain of Jin5; n–o Grains of Dgs mutant. fm, floral meristem; st, stamen primordium; cp, carpel primordium; og, out glume; ig, inner glume; l, lemma; p, palea; fl, fertile lemma; sl, sterile lemma. ①, ② and ③ indicated three patterns of stamen and pistil differentiation in Dgs. Scale bars = 100 μm (a-c, e-l), 300 μm (d) and 1 mm (m–o)

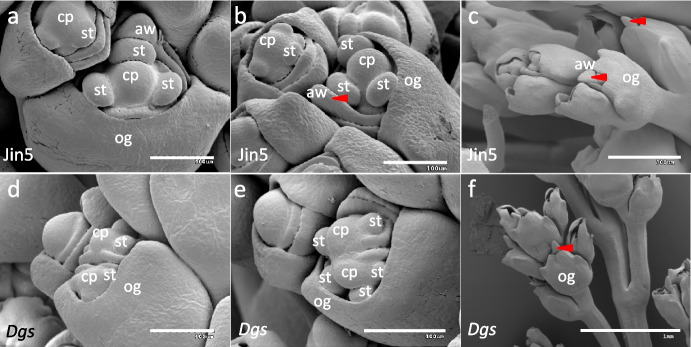

Once the stamen and pistil differentiation finished, the outer glume continues to develop, wrapping the inner glume, lemma and palea, and only the expanded carpels and stamens can be seen in Jin5 (Fig. 3a-c) and in Dgs mutant (Fig. 3d-f). In some floret, the awn primordium, which developed from the tip of lemma, could be seen (Fig. 3c, indicated by red arrow). Henceforth, the process of development of glume, lemma and palea in Jin5 was same as in Dgs mutant until the outer glume enclosed the inner floral organs (Fig. 3c, f).

Fig. 3.

Development of stamen and pistil (carpel) in Jin5 and Dgs mutant. a-c Stamen and carpel enlargement in Jin5. d-f Stamen and carpel enlargement in Dgs mutant. cp, carpel primordium; st, stamen primordium; og, out glume; aw, awn. Scale bars = 100 μm (a-b, d-e), 300 μm (c) and 1 mm (f)

Dgs is a monogenic dominant mutation

To determine the genetic base of the twin-seeded mutation, Jin5 and BTx622B were crossed with Dgs mutant, respectively. All F1 plants from the two crosses showed twin-seeded grain phenotype (Fig. S2), indicating that the mutation is dominant. Among the 1115 F2 individuals of the cross of Jin5 × Dgs, 822 individuals were twin-seeded and 293 individuals were single-seeded. Similarly, 130 were twin-seeded and 58 single seeded among the 188 F2 individuals of the cross of BTx622B × Dgs (Table 1). Both ratios fit single dominant gene inheritance (Table 1), suggesting that twin-seeded phenotype in Dgs is controlled by a single dominant gene.

Table 1.

Segregation of twin-seeded and single-seeded individuals in the F2 populations from Jin5 × Dgs and BTx622B × Dgs

| Combination | No. of twin-seeded plants | No. of single-seeded plants | Total No. of plants | χ2 (3:1) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jin5 × Dgs | 822 | 293 | 1115 | 0.937 | 0.333 |

| BTx622B × Dgs | 130 | 58 | 188 | 3.433 | 0.064 |

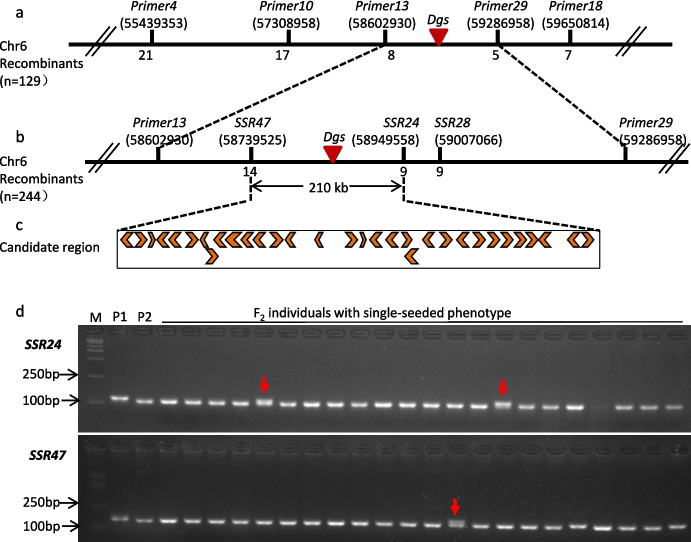

BSA-seq analysis and fine-mapping of the Dgs locus

The genomes of the two parents, Dgs mutant and Jin5, were sequenced to ~ 10 × coverage (~ 11-Gb Illumina re-sequencing data), while the two bulks were sequenced to ~ 40 × coverage for each (~ 44-Gb data). After sequence alignment, SNP/InDel calling and quality control, a total of 3894375 SNPs and 2019113 InDels were used for BSA-Seq analysis. Δ(SNP-index), G’ and -log10 (p) were plotted and used to determine the significant associated regions (Fig. 4). The highest peak region, which was considered as the candidate interval for the Dgs gene, was located on chromosome 6 in theΔ(SNP-index) (Fig. 4a), G’ values (Fig. 4b) and -log10 (p) distribution plots (Fig. 4c) and contained 9.6 Mb, suggesting that Dgs was located on chromosome 6.

Fig. 4.

The preliminary mapping of Dgs using 3 QTL-seq methods. a A Manhattan plot showing the distribution of Δ(SNP-index) on 10 chromosomes of sorghum. b Manhattan plot showing the distribution of G’ values on 10 chromosomes of sorghum. c -log10(p) plots on 10 chromosomes of sorghum. Blue and red lines intervals in (a) and (b) represent 95 and 99% confidence, respectively. Black lines in (a) and (b) represent mean values of the algorithm, extracted from sliding window analysis. The gray solid line and dashed line in (c) represent the threshold line 4 and 6, respectively. The colorful bars at the bottom in (c) along the chromosomes indicate polymorphic markers density

To validate and further delimit the region encompassing the Dgs locus, InDel markers were developed surrounding the genetic region of Dgs on chromosome 6 based on re-sequencing data of Jin5 and Dgs mutant. Five polymorphic markers (Table S1) were used to genotype 129 individuals with single-seeded phenotype from the F2 population derived the cross of Jin5 × Dgs. Through linkage analysis of five InDel markers, Dgs locus was delimited into 684 kb between Primer13 and Primer29 (Fig. 5a). To further narrow down the candidate region of Dgs, three polymorphic SSR markers were developed to genotype total of 244 individuals with single-seeded phenotype. Finally, the Dgs locus was narrowed within a 210-kb region including 32 predicted genes between markers SSR47 and SSR24 (Fig. 5b-d).

Fig. 5.

Fine mapping of the Dgs gene. a Linkage analysis of Dgs and 5 Indel markers on chromosome 6 based on 129 single-seeded individuals (The number under each primer indicated the physical position on chromosome 6); b Fine mapping narrowed the Dgs locus to a 210-kb region between SSR24 and SSR47; c 32 genes are predicted in the 210-kb region in Phytozome database. d Amplification profiles of partial F2 individuals from Jin5 × Dgs by SSR24 and SSR47 markers. M, DNA ladder; P1, Dgs parent; P2, Jin5 parent. Arrows indicate recombinants

Analysis of candidate gene for Dgs

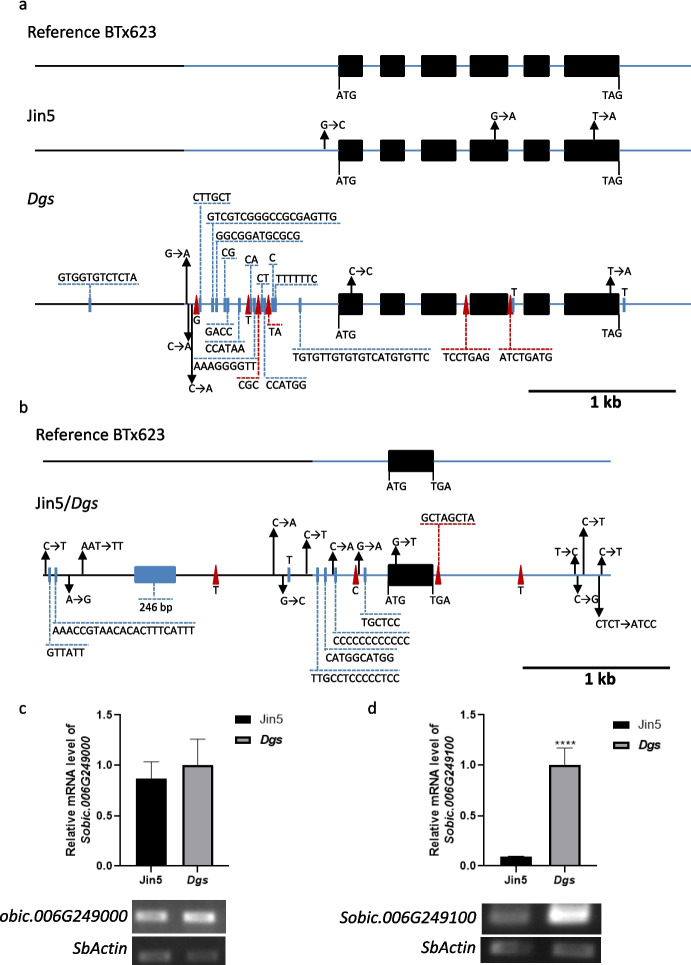

The Dgs was fine-mapped to a region of 210 kb on chromosome 6, which contained 32 putative genes (Fig. 4d and Table S2). Among the 32 predicted genes, 11 genes have unknown functions (Table S2). Two candidate genes Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 attracted our attention. Sobic.006G249000 encodes a receptor protein serine/threonine kinase, similar to Arabidopsis CLV1 gene, which regulates the size of meristem and affects the floral organ number or floral morphology (Clark et al. 1997). Sobic.006G249100 is located around 15 kb downstream of Sobic.006G249000. Sobic.006G249100 was similar to CLV3 in Arabidopsis (Clark et al. 1995) and FON2 and FON4 in rice (Chu et al. 2006; Suzaki et al. 2009). To investigate whether Sobic.006G249000 was the causal gene for twin-seeded mutation, we performed Sanger DNA sequencing on the region of 3249 bp of Sobic.006G249000, containing the promoter, 5’UTR, ORF and 3’UTR of Dgs and Jin5. Compared with the reference genome BTx623 (a single-seeded variety), the sequence of Jin5 contained one base substitution in the 5’UTR, one synonymous mutation in 4th exon and one substitution in the 6th exon (T to A) which caused M to K in amino acid (Fig. 6a). Compared with reference genome BTx623, the sequence of Dgs mutant showed one base synonymous substitution in 1st exon (Fig. 6a). One base substitution (T to A) occurred in the 6th exon, caused M to K in amino acid of peptide (Fig. 6a). Notably this base substitution in the 6th exon also occurred in Jin5, which meant it was not likely the cause of twin-seeded mutation. Two short insertions were found in the 3rd and 4th introns of Sobic.006G249000 in Dgs mutant, which didn’t affect the splicing pattern of introns (Fig. 6a). Dgs had 12 bp deletion in the promoter and multiple insertions and deletions in 5’UTR region of Sobic.006G249000, resulting in a total of 90 bp deletions in 5’UTR of Dgs compared with reference genome BTx623 (Fig. 6a). Multiple single base substitutions were found in the 5’UTR region of Sobic.006G249000 in Dgs mutant (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Sequencing and expression analysis of Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 in Dgs mutant and Jin5. a-b Sequencing analysis of Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 in Jin5 and Dgs mutant, respectively. The black solid boxes indicated the exons; Solid red triangles indicated insertions and solid blue rectangles indicated deletions; Arrows indicated the substitutions. c-d The expression level of Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 in the inflorescence of Jin5 and Dgs mutant, respectively. The histograms were the results of RT-qPCR, while the bottom gels were the semi-quantitative results

We also analyzed the genomic sequence of around 4 kb of Sobic.006G249100 including the promoter, 5’UTR, ORF and 3’UTR regions by Sanger DNA sequencing. Sobic.006G249100 codes a small protein with 94 amino acids, which only contains one exon without introns. The sequencing result of indicated that there was no difference in the promoter, 5’UTR, ORF and 3’UTR regions between Jin5 and Dgs mutant. Compared with the reference genome BTx623, a single base substitution from G to T (the amino acid changed from A to S) in the ORF was present in both Dgs mutant and Jin5. Moreover, multiple substitutions and insertion/deletions were present in the promoter, 5’UTR and 3’UTR of Sobic.006G249100 in both Dgs mutant and Jin5 (Fig. 6b), indicating that these mutations were not the cause to twin-seeded phenotype.

Given that Dgs mutation is controlled by a single dominant gene, the mutations of the upstream region of the candidate gene might result in overexpression in the Dgs mutant. Therefore, to verify whether the deletions in the 5’UTR region of Sobic.006G249000 in Dgs mutant affect its expression, we tested the expression level of Sobic.006G249000 in the inflorescence of Dgs mutant and Jin5 using semi-quantitative RT-PCR and RT-qPCR. The results from both methods showed no significant difference in mRNA level of Sobic.006G249000 between Jin5 and Dgs mutant (Fig. 6c), suggesting that the mutations of the 5’UTR region of Sobic.006G249000 in Dgs mutant didn’t affect the expression level of Sobic.006G249000. We further detected the expression level of Sobic.006G249100 in the inflorescence of Dgs mutant and Jin5. The result showed that mRNA level of Sobic.006G249100 was significantly up-regulated in Dgs mutant (Fig. 6d). The relative mRNA level of Sobic.006G24910 in Dgs mutant was 10 times of that in Jin5 from the RT-qPCR results (Fig. 6d), indicating that Sobic.006G249100 may be the candidate gene for Dgs.

Discussion

Spikelets are the constituent units of various types of inflorescence structures in Poaceae plants. Sorghum spikelets contain PS and SS, which are sterile and fertile, respectively. The molecular mechanisms underlying the development and evolution of the sorghum spikelets are still unclear. In the current study, we found a twin-seeded mutant sorghum, named Dgs, with each floret having two carpels and six stamens in one pair of glumes on the SS, ultimately resulting twin grains on each SS. In previous study, we mapped the Dgs gene to a region of 404 kb on chromosome 6 (Zhou et al. 2022). In the current study, the Dgs was further delimited into a region of 210 kb, which contained 32 predicted genes (Table S2) and the floral organ developmental progress was characterized using SEM method.

The development of stamen and pistil on both sides of floral meristem in Dgs mutant was not always synchronous, which caused the different size of the twin seeds in one glume. Based on the SEM results, three patterns of pistil and stamen differentiation were observed in floral meristem of Dgs mutant (Fig. 2d-l). For pattern 2 (Fig. 2h-i), the two sets of stamen and pistil initiated and developed synchronously, and finally resulted two grains of same size in one pair of glume. Due to the asynchronous development of pistil and stamen for pattern 1 and 3 (Fig. 2d-f, j-l), one of the two grains in one glume was larger than the other one. It could be concluded that pistil and stamen differentiation stage was the key stage, when eventually leaded to the characteristics of two kernels in a pair of glumes in Dgs mutant. Our SEM observation could confirm Karper and Stephens’s (1936) speculation that twin-seed formation was a division of the pistil primordium from which the single ovary normally develops. The SEM observation was also consistent with Cron’s report that both grains of the pair in one glume are usually of same size; however, one of them is sometimes slightly larger (Cron 1916). It can be reasonably inferred that the size difference of the twin seeds is due to asynchrony of pistil and stamen differentiation and development. However, it is still unclear why there were different patterns of pistil and stamen differentiation on one panicle of Dgs mutant. Further study is needed to reveal the underling mechanism.

According to previous reports (Singh et al. 1997; Madhusudhana et al. 2015), the flower of the sessile spikelet of sorghum consists of out glume, inner glume, lemma, palea and sterile lemma. In our observation, the sterile lemma in Dgs mutant could fully develop another set of reproductive organs, three stamens and one carpel, which could set a second grain with germinating ability within the same glume. Since Dgs is dominant mutation it means the ancestral sterile lemma should be fertile and could produce a full-filled grain. We also observed sessile floret with three carpels and six stamens (Fig. 1j) and triple grains of same size in one pair of glumes in Dgs mutant (Fig. 1k). Since the size of three grains are same, it is reasonable speculated that the three carpels were differentiated from the top of floret primordium synchronously, similar to the second pattern of stamen and carpel differentiation in a typical twin-seeded floret.

As far as we know, there is no report on the observation of inflorescence differentiation progress of multiple-seeded sorghum using SEM analysis. Using the traditional paraffin section method, the ovary and anther development processes of double grain sorghum ISD-1 were observed (Wang et al. 2016). Through cytology study on the female and male gametophyte development of double grain sorghum ISD-1, it was found that the pistil base of fertile flowers of SS grew into two different sized cavities. The development of ovules, megasporogenesis, anther and microsporogenesis were out of synchronization in two cavities (Wang et al. 2016). The asynchronous development of double grain in Dgs mutant observed in the current study was in agreement with the result observed in double grain sorghum ISD-1 (Wang et al. 2016).

Among the 32 predicted genes in the Dgs candidate region, Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 were considered as the most likely the candidate gene since they contain the key domain which caused floral organ mutation in Arabidopsis and rice. Sobic.006G249000 contains a serine/threonine kinase domain, similar to CLV1 gene in Arabidopsis (Clark et al. 1997). Sobic.006G249100 contains a CLE domain, which is similar to CLV3 in Arabidopsis (Clark et al. 1995) and FON2 and FON4 in rice (Chu et al. 2006; Suzaki et al. 2009). Although there is no difference in the coding sequence of the Sobic.006G249000 between Dgs mutant and Jin5, multiple insertions and deletions were present in the upstream of the start codon of Dgs mutant which resulted in a total of 90 bp deletions. However, these mutations did not change the expression level of Sobic.006G249000 in Dgs mutant, suggesting that Sobic.006G249000 may not be the causal gene of Dgs because dominant mutation (Dgs mutant was a dominant mutant) usually results in the overexpression of target gene. For Sobic.006G249100, the genomic sequence of Sobic.006G249100 including coding region, and the downstream region didn’t show any difference between Dgs mutant and Jin5 (Fig. 6b). Interestingly and surprisingly, the expression level of Sobic.006G249100 was extremely up-regulated in Dgs mutant compared with Jin5 (Fig. 6d-e). This result was consistent with the genetic analysis of Dgs mutant which showed Dgs is dominant inheritance, indicating Sobic.006G249100 may be the causal gene of Dgs. Recent study showed that slclv3 mutants in tomato, a gain of function mutant with upregulated expression, developed enlarged meristems, increased floral organ and fruit locule number (Rodriguez-Leal et al. 2019). RT-qPCR analysis showed that both SlCLV3 and SlCLE9 were upregulated more than 40-fold in slclv3 meristems. The result was in agreement with our result, in which the CLV3/LCE related gene Sobic.006G249100 was significantly upregulated in the Dgs mutant. We speculated that extremely upregulated expression of Sobic.006G249100 in Dgs mutant may be resulted from the following reasons. Firstly, the methylation levels of the promoter region of Sobic.006G249100 between Dgs mutant and Jin5 may be different and results in the difference of expression levels. For example, CpG island in genomic DNA sequence or the methylation of histone on the chromatin (such as the inhibited histone methylations with H3K9 and H3K27, or the active methylations with H3K4 and H3K36) could cause the up-regulation or down-regulation of target genes in plants (Xiao et al. 2016; Cheng et al. 2020; Hu and Du 2022). Secondly, there may be unknown regulator to bind the promoter of Dgs mutant, upregulating the expression of Sobic.006G249100 in Dgs mutant. Thirdly, there may be an enhancer of Sobic.006G249100 in Dgs mutant. Based on these cases and the results provided in this study, further functional complementary experiments of Sobic.006G249000 and Sobic.006G249100 in sorghum, measurement of methylation levels and the activity of promoter will provide effective evidences to verify the function of Dgs in the future work.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (32001513).

Author contributions

SL and WL designed the research. SL, SZ, ZY, YT, YH, JW, DL and SZ performed experiments. SL, SZ, MQ, YL, and XM analyzed the data. SL and WL wrote the manuscript with inputs of other authors.

Data availability

The data matrixes produced during the current investigation are only accessible from the corresponding authors on a justifiable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shanshan Liang, Email: skylss@tjnu.edu.cn.

Yunhai Li, Email: yhli@genetics.ac.cn.

Weijiang Luan, Email: lwjzsq@163.com.

References

- Bell AD (2008) Plant form: an illustrated guide to flowering plant morphology. Timber Press Inc., Portland [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1997) Multiple hypotheses testing with weights. Scand J Stat 24:407–418 [Google Scholar]

- Brand U, Gru M, Hobe M, Simon R (2002) Regulation of CLV3 expression by two homeobox genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiolgoy 129:565–575. 10.1104/pp.001867.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Klein PE, Bortiri E et al (2006) Inheritance of inflorescence architecture in sorghum. Theor Appl Genet 113:931–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burow G, Xin Z, Hayes C, Burke J (2014) Characterization of a multiseeded (msd1) mutant of sorghum for increasing grain yield. Crop Sci 54:2030–2037. 10.2135/cropsci2013.08.0566 [Google Scholar]

- Casady AJ, Ross WM (1977) Effect of the twin-seeded character on sorghum performance. Crop Sci 17:117–120. 10.2135/cropsci1977.0011183x001700010032x [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K, Xu Y, Yang C et al (2020) Histone tales: Lysine methylation, a protagonist in Arabidopsis development. J Exp Bot 71:793–807. 10.1093/jxb/erz435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H, Qian Q, Liang W et al (2006) The floral organ number4 gene encoding a putative ortholog of arabidopsis CLAVATA3 regulates apical meristem size in rice. Plant Physiol 142:1039–1052. 10.1104/pp.106.086736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM (1995) CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development 2067:2057–2067 [Google Scholar]

- Clark SE, Williams RW, Meyerowitz EM (1997) The CLAVATA1 gene encodes a putative receptor kinase that controls shoot and floral meristem size in Arabidopsis. Cell 89:575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cron AB (1916) Triple seeded spikelets in sorghum. J Amerrican Soc Agron 8:237–238 [Google Scholar]

- Dampanaboina L, Jiao Y, Chen J et al (2019) Sorghum MSD3 encodes an ω-3 fatty acid desaturase that increases grain number by reducing jasmonic acid levels. Int J Mol Sci 20:5359. 10.3390/ijms20215359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JC, Brand U, Running MP et al (1999) Signaling of cell fate decisions by CLAVATA3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems. Science 283:1911–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes MJ, Slafer GA, Davies WJ et al (2011) Raising yield potential of wheat. III. Optimizing partitioning to grain while maintaining lodging resistance. J Exp Bot 62:469–486. 10.1093/jxb/erq300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladman N, Jiao Y, Lee YK et al (2019) Fertility of pedicellate spikelets in sorghum is controlled by a jasmonic acid regulatory module. Int J Mol Sci 20:4951. 10.3390/ijms20194951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Du J (2022) Structure and mechanism of histone methylation dynamics in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 67:102211. 10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Qian Q, Mao L et al (2005) Characterization of the rice floral organ number mutant fon3. J Integr Plant Biol 47:100–106. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2005.00017.x [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Zhang W, Xia Z et al (2007) A paracentric inversion suppresses genetic recombination at the FON3 locus with breakpoints corresponding to sequence gaps on rice chromosome 11L. Mol Genet Genomics 277:263–272. 10.1007/s00438-006-0196-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Lee YK, Gladman N et al (2018) MSD1 regulates pedicellate spikelet fertility in sorghum through the jasmonic acid pathway. Nat Commun 9:822. 10.1038/s41467-018-03238-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JH, Fiume E, Fletcher JC (2008) The CLE family of plant polypeptide signaling molecules. Cell Mol Life Sci 65:743–755. 10.1007/s00018-007-7411-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karper RE (1931) Multiple seeded spikelets in sorghum. Ameriacna J Bot 18:189–194 [Google Scholar]

- Karper RE, Stephens JC (1936) Floral abnormalities in sorghum. J Hered 27:183–194. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a104204 [Google Scholar]

- Kayes JM, Clark SE (1998) CLAVATA2, a regulator of meristem and organ development in Arabidopsis. Development 125:3843–3851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA (2015) Poaceae. In Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Springer, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- Laux T, Mayer KFX, Berger J, Jürgens G (1996) The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 122:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H (2013) Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. Quantitative Biol 00:1–3 [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al (2009) The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhana R, Rajendrakumar P, Patil JV (2015) Sorghum molecular breeding. Springer, India [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld BN, Grumet R (2018) QTLseqr: An R package for bulk segregant analysis with next-generation sequencing. Plant Genome 11:2. 10.3835/plantgenome2018.01.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KFX, Schoof H, Haecker A et al (1998) Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. J Microsc 109:805–815. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1977.tb01111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick RF, Truong SK, Sreedasyam A et al (2018) The Sorghum bicolor reference genome: improved assembly, gene annotations, a transcriptome atlas, and signatures of genome organization. Plant J 93:338–354. 10.1111/tpj.13781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan V, Danecek P, Scally A et al (2016) Genetics and population analysis BCFtools/RoH : a hidden Markov model approach for detecting autozygosity from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 32:1749–1751. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsahi-ferstad H, Le DE, Dumas C, Rogowsky PM (1997) ZmEsr, a novel endosperm-specific gene expressed in a restricted region around the maize embryo. Plant J 12:235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/

- Rodriguez-Leal D, Xu C, Kwon CT et al (2019) Evolution of buffering in a genetic circuit controlling plant stem cell proliferation. Nat Genet 51:786–792. 10.1038/s41588-019-0389-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh F, Rai KN, Reddy BVS, Diwakar B (1997) Development of cultivars and seed production techniques in sorghum and pearl millet-training manual. In: Training manual. Training and Fellowships Program and Genetic Enhancement Division, ICRISAT Asia Center, India, Patancheru 502 324, Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institue for the Semi-Arid Tropics. p 118

- Sreenivasulu N, Schnurbusch T (2012) A genetic playground for enhancing grain number in cereals. Trends Plant Sci 17:91–101. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Sato M, Ashikari M et al (2004) The gene FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER1 regulates floral meristem size in rice and encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase orthologous to Arabidopsis CLAVATA1. Development 131:5649–5657. 10.1242/dev.01441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Toriba T, Fujimoto M et al (2006) Conservation and diversification of meristem maintenance mechanism in Oryza sativa: Function of the FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 gene. Plant Cell Physiol 47:1591–1602. 10.1093/pcp/pcl025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzaki T, Ohneda M, Toriba T et al (2009) FON2 SPARE1 redundantly regulates floral meristem maintenance with FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER2 in rice. PLoS Genet 5:e1000693. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi H, Abe A, Yoshida K et al (2013) QTL-seq: rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant J 74:174–183. 10.1111/tpj.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters DR, Keil DJ (1988) Vascular Plant Taxonomy, 4th edit. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Companty, Dubuque [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang Y, Cheng Y et al (2016) Cytology characteristics of double grain sorghum development. J Agric 6:61–68 [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Lee US, Wagner D (2016) Tug of war: adding and removing histone lysine methylation in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Plant Biol 34:41–53. 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S, Yang W, Zhai R et al (2017) Mapping and application of the twin-grain1 gene in rice. Planta 245:707–716. 10.1007/s00425-016-2627-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Nagato Y (2011) Flower development in rice. J Exp Bot 62:4719–4730. 10.1093/jxb/err272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Zheng G, Saul K et al (2017) Evaluation of the multi-seeded (msd) mutant of sorghum for ethanol production. Ind Crops Prod 97:345–353. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.12.015 [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Zhang J, Zhuang H et al (2019) Gene mapping and candidate gene analysis of multi-floret spikelet 3 (mfs3) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Integr Agric 18:2673–2681. 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62652-3 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Yi Z, Wang X et al (2022) Genetic analysis and gene mapping of sorghum Double-grain mutant Dgs. Biotechnol Bull 38:171–177 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu K, Tang D, Yan C et al (2010) Erect panicle2 encodes a novel protein that regulates panicle erectness in indica rice. Genetics 184:343–350. 10.1534/genetics.109.112045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data matrixes produced during the current investigation are only accessible from the corresponding authors on a justifiable request.