Abstract

Schizophrenia is a complex neuro-psychiatric disorder including positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive deficits. A key cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia is a deficit in visual working memory (VWM). VWM involves three distinct stages: encoding, maintenance, and retrieval. The deficit in any one stage would produce the same symptom (i.e., poor VWM), although their causes are not the same. In this study, we used a retro-cue VWM task that provides helpful cues at different stages: early in maintenance (early cue), late in maintenance (late cue), or during retrieval (retrieval cue). This modification would help “tag” or identify the cognitive stage(s) most responsible for impaired VWM performance in schizophrenia. Additionally, we took advantage of this tagging feature and applied 6 Hz transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) over the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and right posterior parietal cortex (PPC)—which has previously been shown to enhance VWM in low-performing healthy individuals—to examine whether tACS would improve a specific stage or all stages of VWM processing in schizophrenia. We observed that cues significantly enhanced performance in low-performing patients, who benefited equally from early and late maintenance cues, but not from retrieval cues. These low-performers also responded well to theta tACS in their overall VWM performance as opposed to a specific VWM stage. No improvement effect was observed in high-performing patients for both retro cue and tACS. Together, our data suggest that 1) low-performing patients’ VWM deficits likely stem from poor memory consolidation rather than retrieval, 2) right frontoparietal theta tACS can improve low-performing patients’ VWM performance, and 3) such facilitatory tACS effect is not selective of a specific VWM stage and thus is likely driven by an improvement in overall visual attention.

Subject terms: Schizophrenia, Working memory

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder that affects between 0.4% and 1% of the global population1. This disease has a significant economic impact on both individual patients and the broader community. It is characterized by a range of clinically distinct positive and negative symptoms2. Although psychosis—manifested through hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized behavior—is the most conspicuous clinical feature of schizophrenia, cognitive impairments are now recognized as a central domain of dysfunction in the disorder3. Among these, impairment in working memory (WM) is a major cognitive deficit observed in SCZ patients4 and persists throughout the course of the illness5. Moreover, deficits in WM have been proposed as a foundational cause of many higher-order cognitive symptoms of SCZ, as such impairments can lead to failures in behavior that rely on internalized representations of mental schemata and ideas6,7. Notably, WM impairments in SCZ patients have been documented across various modalities, including visuospatial, auditory, and haptic8.

Memory stages

The studies mentioned above demonstrate impaired visual working memory (VWM) in patients with SCZ. However, the origins of such WM impairments can be complex, as various cognitive and neurobiological models suggest that WM processing involves three distinct phases: encoding, where subjects memorize a set of items; maintenance, where subjects retain what they have encoded; and retrieval, where subjects recall what was previously memorized9–11. In this context, any single or combination of faulty stages in WM processing can lead to the same symptom—WM impairment—although the underlying causes may vary12. Therefore, studies investigating the neural correlates of WM impairment in healthy individuals may not necessarily be applicable to SCZ.

Previous cognitive research has employed a “retro-cue” task design to examine the role of each VWM stage (encoding, maintenance, retrieval). In this design, retro-cues serve as location indicators for a changed stimulus, allowing participants to use these cues for improved maintenance or facilitated retrieval, depending on the timing of the cue presentation13,14. This approach enables the examination of each stage’s contributions to VWM processing by deploying retro-cues in a time-specific and stage-specific manner. For instance, Yang et al.15 conducted a series of experiments on feature-only and feature-binding tasks, supplementing retro-cues during the early and late maintenance stages. Their findings indicated that an early maintenance cue initiated top-down control, thereby reinforcing the maintenance of individual features and feature combinations15. Similarly, Yang et al.16 explored the effects of retro-cues during the retrieval phase of a VWM color change detection task. They reported that introducing a retro-cue during the retrieval stage reduced the decision load associated with color and spatial relationships, thereby enhancing overall color change detection performance. This was in contrast to no-cue conditions, where a relatively high decision load impaired detection capabilities16. Thus, the strategic inclusion of cues at different VWM stages could provide a method to elucidate the functionalities of these stages, and has not been done in SCZ.

Role of DLPFC and PPC in WM

Neuroimaging studies have reported increased activities in a network of regions such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortices, parietal cortices, premotor cortices, and inferior prefrontal cortex9,17. In particular, the frontoparietal network consisting of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) are involved in distinct processes of VWM processing18–24, and their activity levels seem to correlate with one’s VWM bottleneck and performance25.

In patients with SCZ, Jong et al. (2008) conducted event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) on SCZ patients experiencing first-episode psychosis. The results indicated that these patients exhibited deficits in higher cognitive control conditions due to DLPFC dysfunction, as well as impaired functional connectivity between the DLPFC and other brain regions26. Similarly, Chai et al.27 performed resting-state fMRI on various disease states, including 16 SCZ patients and 15 healthy controls, observing an anti-correlation between the medial and ventral lateral regions of the prefrontal cortex in the healthy group but not in the SCZ group. In another study, Meyer-Lindenberg et al.28 used positron emission tomography (PET) during a WM challenge and sensory motor control task, noting reduced activity in the DLPFC and left cerebellum during the WM task in SCZ patients. More recently, Vera Montecinos et al.29 conducted a proteomic analysis using single-shot liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry on the gray matter of postmortem DLPFC to understand the altered protein networks in SCZ. They found that 43 proteins were significantly altered in the SCZ group compared to healthy controls in the DLPFC region. Additionally, Koch et al.30 utilized a novel twin-coil transcranial magnetic stimulation (tcTMS) approach to study ipsilateral parieto-motor connectivity in SCZ patients, and observed disrupted connectivity between PPC and ipsilateral motor cortex compared to the control group. Hahn et al.31 also combined fMRI with a WM task involving different set sizes of stimuli, and found significantly less WM capacity-dependent signal modulation in the PPC of SCZ patients compared to control subjects. Together, these studies suggest that dysfunctions in both the DLPFC and PPC are likely sources of WM insufficiency in SCZ patients.

Oscillatory activities in DLPFC and PPC

In addition to the involvement of specific brain regions, brain oscillatory activities such as theta and gamma oscillations play significant roles in VWM processing21,32–37. Several studies have identified theta oscillation abnormalities as a key feature in SCZ patients. For example, Schmiedt et al.38 used electrophysiology with an N-back task in SCZ patients to study changes in post-stimulus theta activity. While the control group exhibited increased post-stimulus theta amplitude at fronto-central locations, the patient group did not show such modulations. Similarly, Hamilton et al.39 conducted an EEG study on SCZ patients during a visual plasticity paradigm and found that visual high-frequency stimulation-induced changes in visual evoked potential in healthy controls but not in SCZ patients. Additionally, visual high-frequency stimulation enhanced overall theta band power in healthy individuals, an effect absents in SCZ patients.

To establish a causal relationship between neural oscillatory activities and WM performance, researchers have employed transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) at either theta or gamma frequencies to target specific oscillatory activities. In healthy individuals, successful attempts have been made, particularly in low-performing participants, where right frontoparietal tACS in the theta range improved VWM performance21,37. In SCZ patients, Kallel et al.40 applied 4.5 Hz tACS over the DLPFC in three clozapine-resistant SCZ patients for 20 min per session across 20 sessions with 2 mA current intensity. They observed a significant decrease in both negative and general symptoms, suggesting beneficial effects of theta tACS in SCZ patients. Furthermore, Sreeraj et al.41 applied 40 Hz gamma and 6 Hz theta tACS over the left DLPFC and left PPC in an SCZ patient, finding that only theta tACS exhibited facilitative effects on a Sternberg test. Therefore, further investigations of theta tACS as a potential therapeutic modality in SCZ are warranted to develop methods for mitigating related symptoms.

The present study

As discussed above, SCZ patients exhibit memory and cognitive deficits that are linked to impaired theta oscillations in the DLPFC and PPC27–39 Vera Montecinos et al.29). Consequently, the application of theta tACS has been shown to improve both negative symptoms and overall cognition40,41. Given that VWM processing involves distinct stages, our study aims to determine whether memory impairment in SCZ patients arises from deficits in a specific stage or from deficiencies across the general domain. To this end, we designed a color change detection task in which we tagged each stage by providing retro-cues during the early and late maintenance stages and the retrieval stage. Additionally, we applied theta tACS to investigate whether such stimulation could ameliorate stage-specific impairments (if any).

In this study, we hypothesize that if SCZ patients have deficits during any specific stage, the respective cue will aid performance in that particular stage. Similarly, if SCZ WM impairment is due to impaired processing across multiple (or all) stages, then retro-cues should enhance performance across all stages. Importantly, this stage-specific cue design is combined with tACS so that if tACS is particularly effective in any one (or more) stages of VWM processing, its impact will be “tagged” by our stage-specific retro-cues and identified in our analysis as a significant interaction between cue timing and active/sham tACS. This tagging design, previously utilized by our team21 in healthy participants, demonstrated that right frontoparietal theta tACS nonselectively enhanced performance at every stage of VWM. Thus, the purpose of the present study is twofold: 1) to investigate which VWM stage is particularly impaired in SCZ patients compared to healthy controls (without tACS), and 2) to determine which, if any, VWM stages are specifically amenable to improvement through our theta tACS in SCZ patients.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled individuals diagnosed with SCZ who were in a chronic and stable condition, aged between 20 and 65 years, recruited from either the day ward or outpatient department. The diagnosis of SCZ was confirmed by two trained psychiatric specialists using structured interviews based on DSM-5 criteria and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Pinninti et al.42). Exclusion criteria included a history of claustrophobia, substance abuse within six months prior to the study, electroconvulsive therapy within the same time frame, coma resulting from previous brain injury, or the presence of metal implants not suitable for brain MRI. Ultimately, 31 participants with normal or corrected-to-normal vision completed the study. Data from three participants were excluded: two due to technical issues and one due to being a statistical outlier. Data from the remaining 28 participants were analyzed. This study was conducted with the approval of the Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to taking part in the study.

Baseline clinical evaluation

Prior to tACS stimulation and the VWM task, we conducted baseline clinical evaluations on the participants. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was employed to assess the severity of symptoms in SCZ (Wu et al.43), while the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) was administered to measure depressive symptoms44. Cognitive function was evaluated using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition (WAIS-IV), which includes assessments of full intelligence quotient (IQ) and working memory (Tsai et al.45; Wechsler et al.46). These measures, namely PANSS, BDI, WAIS-IV, and MoCA, have all exhibited satisfactory reliability, validity, and sensitivity to changes in clinical populations. Additionally, a daily chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalent was calculated for each participant to represent their average daily doses of antipsychotic medication (Woods et al.47).

Stimulation protocol

The stimulation procedures were performed by applying tACS in the form of constant-current stimulation from a StarStim stimulator (Neuroelectric, Barcelona, Spain). For the stimulation, two rounded rubber electrodes covered with saline (NaCl solution)-soaked sponges (5 cm × 5 cm in diameter) were placed over F4 and P4 regions. Further, the stimulation was applied at a frequency of 6 Hz and peak-to-peak current intensity of 1.5 mA for 15 min (with 30 s ramp-up and 30 s ramp-down time). The phase offset between the electrodes was set to 1800 (i.e., anti-phase stimulation). The order of the sham and active tACS sessions was counterbalanced for all participants where the sham and active sessions were separated at least by 2 days.

Tasks and procedures

Participants were arranged to sit 57 cm apart from and in front of a monitor with a chinrest. E-Prime, version 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools Inc., USA) was used to design the experimental task. In the task, each trial was started with a black fixation cross that was appeared for 500 ms followed by a memory array for 1000 ms. Further, a retention interval of 2000 ms was provided and then a test array appeared on the screen till response. The test array was set to match with that of the memory array 50% of the time. The memory and test arrays consisted of six different colors without repetition randomly selected from nine highly distinguishable colors (black, blue, brown, green, orange, purple, pink, red, and yellow). Each color was set to be used only once in each trial. The arrays were shaped as circles filled with respective color as described (1.6° visual angle) and presented in a scattered manner at the center of a square (15 cm × 15 cm) with gray background (Highly distinguishable from the color-filled circles).

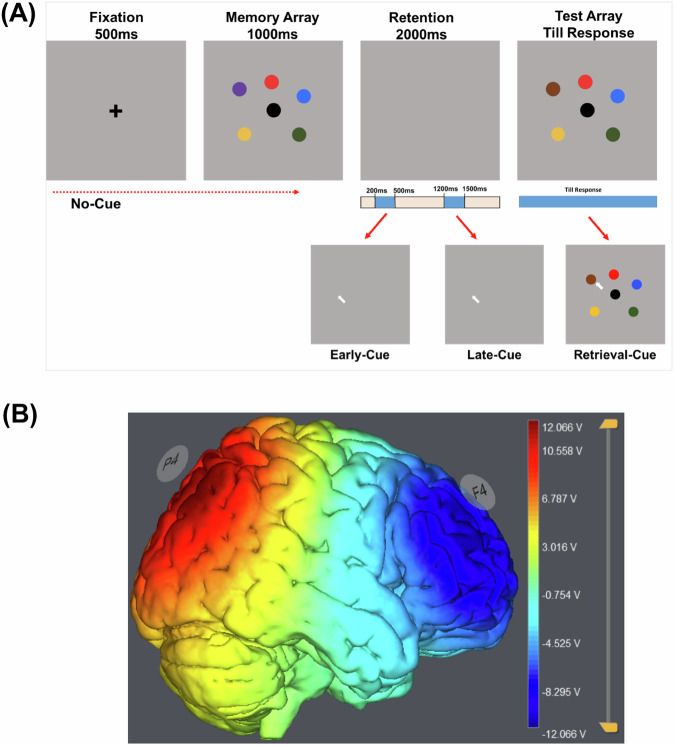

The task was designed including four different conditions such as no-cue, early maintenance cue, late maintenance cue, and retrieval cue. The retro-cue (white arrow, length = 1.6 cm) was set to appear in early and late maintenance and retrieval cue conditions where in the no-cue condition, the test array appeared after the delay period that was devoid of a retro-cue. Therefore, the no-cue condition was involved in a standard change detection task. Further, the retro-cue was set to appear from 200 to 500 ms (duration of 300 ms) under the early cue condition and from 1200 to 1500 ms (duration of 300 ms) under late maintenance cue conditions after the onset of the delay interval. Furthermore, under the retrieval condition, the retro-cue was set to appear with the onset of the test array and lasted till response. Under all conditions, the test array was set to display till response (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Task Design and Electrode Placement.

A Color change detection paradigm. All conditions involved the use of six colored circles, where one circle changed color in 50% of the trials. The retention interval was 2000;ms, during which a retro-cue appeared from 200 to 500 ms (i.e., early maintenance cue) or 1200–1500 ms (i.e., late maintenance cue). The retrieval cue appeared with the onset of the test array and lasted till response. B Electrode montage and estimation of the induced electric fields in StarStim stimulator. Electrodes were placed over F4 and P4 (anti-phase), and stimulation was applied at a frequency of 6 Hz and peak-to-peak current intensity of 1.5 mA for 15 min. Both P4 (red) and F4 (blue) are stimulated in opposite directions. The scale bar represents potential difference between two regions that are equivalent to the applied current intensity.

Participants were instructed to press “Z” on the keyboard if the test array matched the memory array and to press “M” for no match. Each experiment included 80 trials (20 trials per condition and 4 conditions in total) implemented in an interleaved design such that all trials from all conditions were presented in a mixed and randomized order. Nonmatching trials occurred 50% of the time, where only the color of one circle in the test array was changed without changing the shape or position of the array.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. A total of 28 participants were included in this study, comprising 14 men and 14 women, with no significant difference observed in sex distribution. The mean age of the participants was 43.07 ± 11.26 years, with a mean illness duration of 14.10 ± 9.21 years and an onset age of 26.82 ± 9.21 years. On average, participants had 12.82 ± 2.56 years of education and a mean body mass index of 26.62 ± 6.04 kg/m2. The participants were taking antipsychotics at an average dosage of 638.39 ± 313.70 mg per day of CPZ equivalents. Additionally, their PANSS, BDI, full IQ (WAIS-IV), working memory (WAIS-IV), and MoCA scores were 79.32 ± 13.62, 17.78 ± 12.16, 83.64 ± 14.48, 87.46 ± 14.54, and 23.82 ± 3.37, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants.

| All participants | Low-performers | High-performers | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 28) | (n = 17) | (n = 11) | ||

| Age (years) - mean ± SD | 43.07 ± 11.26 | 42.23 ± 11.91 | 44.36 ± 10.61 | 0.634 |

| Sex: male (%) | 14 (50) | 8 (47.05) | 6 (54.54) | 0.713 |

| Education (years) - mean ± SD | 12.82 ± 2.56 | 13.00 ± 2.37 | 12.54 ± 2.94 | 0.656 |

| BMI (kg/m2) - mean ± SD | 26.62 ± 6.04 | 26.74 ± 6.78 | 26.42 ± 5.02 | 0.894 |

| Duration of illness (years) - mean ± SD | 14.10 ± 9.21 | 13.41 ± 9.54 | 15.18 ± 9.03 | 0.629 |

| Onset of illness (years old) - mean ± SD | 26.82 ± 9.21 | 26.52 ± 6.59 | 27.27 ± 12.61 | 0.839 |

| Daily CPZ equivalents (mg/day) - mean ± SD | 638.39 ± 313.70 | 728.98 ± 261.18 | 498.39 ± 347.92 | 0.056 |

| PANSS - mean ± SD | 79.32 ± 13.62 | 78.17 ± 13.27 | 81.09 ± 14.61 | 0.590 |

| BDI - mean ± SD | 17.78 ± 12.16 | 18.58 ± 12.34 | 16.54 ± 12.35 | 0.673 |

| Full IQ (WAIS-IV) - mean ± SD | 83.64 ± 14.48 | 83.76 ± 16.56 | 83.45 ± 11.29 | 0.957 |

| Working memory (WAIS-IV) - mean ± SD | 87.46 ± 14.54 | 86.64 ± 16.72 | 88.72 ± 11.01 | 0.719 |

| MoCA - mean ± SD | 23.82 ± 3.37 | 23.35 ± 3.67 | 24.54 ± 2.87 | 0.372 |

SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, CPZ chlorpromazine, PANSS The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, BDI the Beck Depression Inventory-II, IQ intelligence quotient, WAIS-IV the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition, MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

p-value for two-tailed t-test between low-performers and high-performers.

Because several previous studies have reported that tACS is beneficial only in case of low-performers but not in high-performers in both healthy and patients with cognitive impairments (for a review, see ref. 48), we have also divided our participants based on a median split of VWM accuracy data. To this end, we compared baseline characteristics between low-performers and high-performers using two-tailed t-tests. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age (p = 0.634), sex (p = 0.713), duration of illness (p = 0.629), onset of illness (p = 0.839), education (p = 0.656), BMI (p = 0.894), PANSS scores (p = 0.590), BDI scores (p = 0.673), full IQ scores (p = 0.957), working memory scores (p = 0.719), and MoCA scores (p = 0.372). The lack of difference in working memory scores is likely due to the fact that WAIS-IV assesses working memory via digit span—a task known for probing auditory/verbal working memory—where as our VWM task here is highly specific towards the visuospatial component of working memory. However, there was a marginally significant difference in the CPZ daily equivalent, with low-performers exhibiting higher levels than high-performers (p = 0.056).

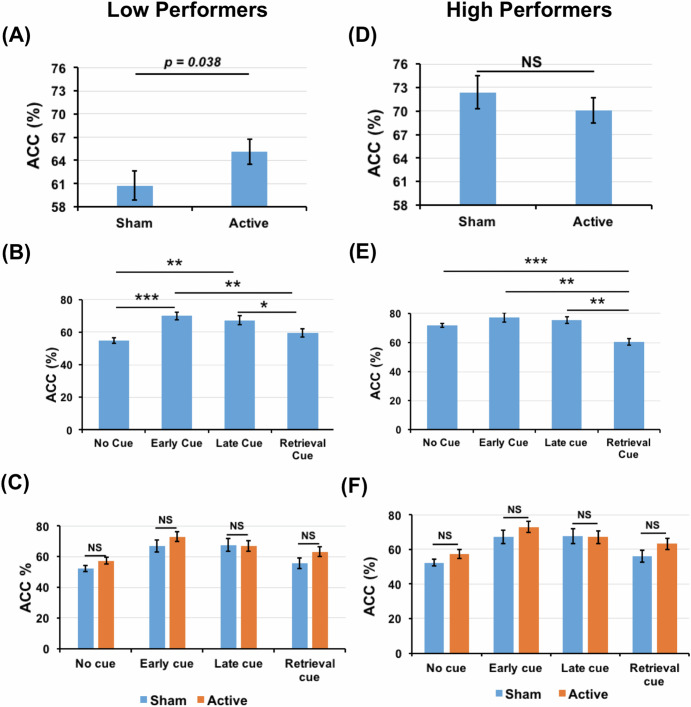

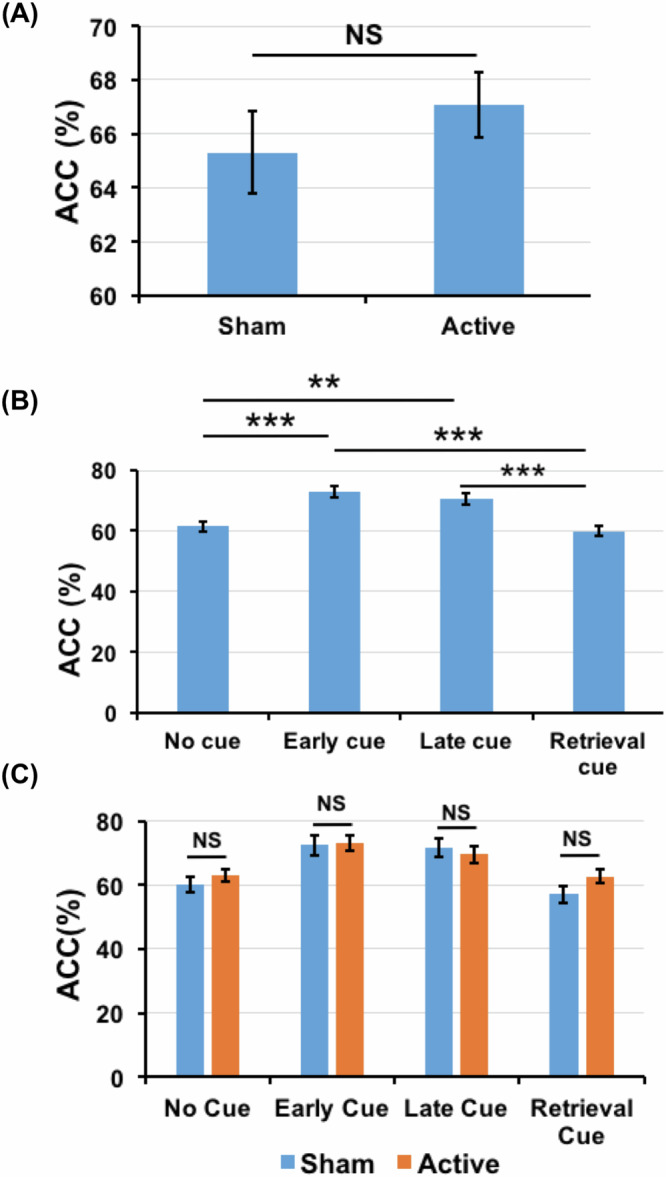

Accuracy

The accuracy (ACC) data of all participants were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA where the factors were included as tACS (sham and active) and cue (retro-cue conditions). The 2-way ANOVA results revealed a non-significant main effect for tACS [F (1,27) = 1.457, p = 0.238, ηp2 = 0.051] (Fig. 2A) but showed a significant main effect for cue conditions [F(3,81) = 17.306, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.391]. In addition, no significant interactions between tACS and cue conditions were observed [F(3,81) = 1.551, p = 0.208, ηp2 = 0.054]. Post-hoc analysis for the cue condition was performed using Holm–Bonferroni correction and showed a significant difference between early-cue and no-cue conditions [t(27) = 4.949, p < 0.001], early-cue and retrieval-cue conditions [t(27) = 6.093, p < 0.001], late-cue and retrieval-cue conditions [t(27) = 5.240, p < 0.001] and late-cue and no-cue conditions [t(27) = 3.536, p = 0.009]. However, no significant differences were observed between early-cue and late-cue [t(27) = 0.427, p = 1.00] and no-cue and retrieval-cue [t(27) = 0.712, p = 1.00] conditions (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Accuracy comparisons in all participants.

A Accuracy (ACC) comparison between the sham and active conditions in all SCZ participants. B ACC comparison between all cue conditions when the active and sham data are collapsed. C ACC of all the cue and tACS combinations. The error bars represent the standard error range of the mean.

As mentioned earlier, several previous studies have reported that tACS is beneficial only in the case of low-performers but not in high-performers21,36,37. To investigate this possibility here, we performed a median split on the basis of ACC data of the participants and divided them into low and high-performers. Furthermore, 2-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to analyze the data that showed a significant main effect for both tACS [F(1,16) = 5.132, p = 0.038, ηp2 = 0.243] and cue conditions [F(3,48) = 13.238, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.453] in low-performers that however did not exhibit significant interactions between tACS and cue [F(3,48) = 1.107, p = 0.356, ηp2 = 0.065] conditions. Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis using Holm–Bonferroni correction indicated a significant difference in ACC data between sham and active conditions [t(16) = 5.962, p = 0.038] (Figs. 3A and 4A). In addition, significant differences were noted between early-cue and no-cue [t(16) = 2.617, p < 0.001], early-cue and retrieval-cue [t(16) = 4.423, p = 0.002], late-cue and no-cue [t(16) = 3.616, p = 0.009] and late-cue and retrieval-cue [t(16) = 3.042, p = 0.023] conditions. The differences between early-cue and late-cue [t(16) = 1.038, p = 0.315] and no-cue and retrieval-cue [t(16) = −1.764, p = 0.194] conditions were not significant (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Accuracy comparisons within low- and high-performers.

A ACC comparison between sham and active conditions in low-performers. B ACC comparison across all the cue conditions when the active and sham data are collapsed in low performers. C ACC of all the cue and tACS combinations in low-performers. D ACC comparison between sham and active conditions in high-performers. E ACC comparison across all the cue conditions collapsing active and sham data in high performers. F ACC of all the cue and tACS combinations in high-performers.

Fig. 4. Accuracy comparisons between low- and high-performers.

A ACC comparison between sham and active conditions in both low and high-performers. B Comparison of different cue conditions between low and high-performers.

Unlike the low-performers, 2-way ANOVA in high-performers did not show significant main effect for tACS [F(1,10) = 1.751, p = 0.215, ηp2 = 0.149] (Figs. 3D and 4A). There was a significant main effect of cue [F(3,30) = 12.008, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.546], without a significant interactions between cue and tACS [F(3,30) = 1.248, p = 0.310, ηp2 = 0.111]. Furthermore, post-hoc analysis using Holm–Bonferroni correction indicated a significant differences between early-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = 4.374, p = 0.008], late-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = 5.038, p = 0.003] and between no-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = 8.600, p < 0.001], suggesting that the retrieval cue may have somehow distracted these high-performers to lead to impaired performance. However, we did not observe significant differences between early-cue and late-cue [t(10) = 0.702, p = 1.00], early-cue and no-cue [t(10) = 0.544, p = 1.000] and late-cue and no-cue [t(10) = 0.571, p = 1.000] conditions (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, we observed that high-performers showed significantly better performance when compared to low-performers in no cue [t(54) = −7.9, p < 0.0001], early cue [t(54) = −1.8, p = 0.03] and late cue [t(54) = −3.98, p < 0.001] conditions, which is expected due to the median split. There was no significant difference between high and low-performer in retrieval cue condition [t(54) = −0.27, p = 0.39] (Fig. 4B).

Reaction time

A two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the reaction time (RT) in low-performers that indicated tACS had no main effects on RT [F(1, 16) = 3.597, p = 0.076, ηp2 = 0.011] (Fig. 5A). However, the cue conditions displayed significant main effects on RT [F(3,48) = 9.871, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.071], where no significant interactions were noted between tACS and the cue conditions [F(3, 48) = 2.065, p = 0.117, ηp2 = 0.008]. Furthermore, post-hoc analysis corresponding cue conditions with Holm–Bonferroni correction showed significant differences between early-cue and retrieval-cue [t(16) = −4.707, p = 0.001], late cue and retrieval cue [t(16) = −5.139, p = < 0.001] conditions but not between early-cue and late-cue [t(16) = −0.414, p = 1.00], early cue and no cue [t(16) = −2.058, p = 0.337], late-cue and no-cue [t(16) = −2.013, p = 0.367] and no-cue and retrieval-cue [t(16) = −1.967, p = 0.400] conditions (Fig. 5B). Similarly, in high-performer both the main effect for tACS [F(1, 10) = 0.248, p = 0.629, ηp2 = 0.001] (Fig. 5D) and tACS cue interaction [F(3, 30) = 0.388, p = 0.763, ηp2 = 0.002] were non-significant. However, the main effect for cue conditions [F(3, 30) = 7.911, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.117] were significant. Subsequent post-hoc comparison with Holm–Bonferroni correction showed a significant difference between late-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = −3.496, p = 0.035] conditions but not between other cue conditions: early-cue and late-cue [t(10) = 0.078, p = 1.00], early-cue and no-cue [t(10) = −1.857, p = 0.558], early-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = −2.916, p = 0.092], late-cue and no-cue [t(10) = −1.963, p = 0.469] and no-cue and retrieval-cue [t(10) = −3.165, p = 0.060] (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. Reaction time comparisons within low- and high-performers.

A Comparison of mean RT data between sham and active conditions in low-performers. B RT comparison across all the cue conditions collapsing active and sham data in low performers. C RT of all the cue and tACS combinations in low-performers. D Mean RT data comparison between sham and active conditions in high-performers. E RT comparison across all the cue conditions where active and sham data are collapsed in high performers. F RT of all the cue and tACS combinations in high-performers.

General discussion

Our results demonstrate that low-performing SCZ patients could benefit from both retro-cues and right frontoparietal theta tACS to enhance their VWM performance. The facilitatory effect of retro-cue was stage-specific, and shows that low-performing patients improved the most when they were given maintenance-stage cues, both early and late. This suggests that SCZ patients’ VWM impairment is possible caused by WM maintenance difficulties such as fast memory decay time, as opposed to retrieval difficulties such as the search process within internal memory representations. In contrast, the facilitatory effect of tACS was nonspecific as it showed a significant main effect yet did not interact with the retro-cues from any stage. Therefore, the facilitatory effect of tACS is likely a domain general, stage-wise nonselective, improvement in visual attention, which led to downstream processes in VWM. No improvement effect was observed in high-performers.

Memory stages in VWM

Although our participants altogether showed improved VWM performance with both early and late maintenance cues (Fig. 2B), such pattern was mostly driven by the low-performers. Indeed, a closer look at the data would reveal that low-performers’ data (Fig. 3B) closely mimicked the grand means (Fig. 2B). High-performers, on the other hand, showed no improvement when given retention cues (both early and late retention stage). Perhaps even worse, high-performers showed significantly worse performance when given retrieval cues (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the retrieval cues were perhaps interfering with their pace or retrieval/response strategies.

Together, these data suggest that high-performing patients did not benefit from the cues. Thus, there seems to be a wide range of individual differences in VWM in SCZ that need to be considered in future research. But most importantly, our low-performers data suggest that, in those SCZ who suffer VWM impairment, the source of such impairment is likely the memory retention/maintenance stage as opposed to memory retrieval. This was similar in healthy participants with the same task, where we have previously reported a significant difference between low- and high-performers in the late-retention stage21. In our patients here, it seems that the impairment propagated to early retention as well, which is why our low-performers benefited from both early and late retention cues. In fact, if we directly compare data from low-performers (Fig. 3B) and high-performers (Fig. 3E) as a function of retro-cue (Fig. 4B), it is clear that low-performers benefitted more from maintenance cues, both early and late, so much so that they were able to shrink the gap with their high-performing counterparts in the cued conditions (compared with the no cue condition, Fig. 4B). Thus, when given temporally precise cues that directly target their maintenance/retention difficulties and minimize their processing burden, low-performing SCZ patients can perform quite well.

We have previously observed similar memory deficits in healthy participants. In that study21, low-performing healthy individuals showed significant improvement with a late retention cue, suggesting a mild retention problem. The strikingly similar pattern observed here in SCZ, albeit in an exacerbated form (i.e., both early and late retention), suggests that SCZ low-performers exhibit a qualitatively similar deficit (i.e., memory retention) as healthy low-performers, but with a more severe progression. One potential explanation for such impairment is memory decay, where memory representations fade quickly in low-performers either due to weak representation or strong competition from other distracting representations. Consequently, our results imply that both SCZ and healthy low-performers struggle to maintain memory representations, with SCZ low-performers experiencing an accelerated decay time extending into the early retention window. Indeed, the efficacy of VWM diminishes over time. For instance, Harvey49 investigated VWM for compound gratings using a same-different memory task and regression-like technique to measure the retention of each spatial frequency component. The results indicated a decline in memory performance at longer retention times49. Similarly, Gao and Bentin50 used face stimuli with either low or high broadband spatial frequencies and tested the patterns of frequency decay in VWM performance. They found that memory representations of stimuli in both frequency bands decayed at a similar rate, suggesting no systematic differences in memory decay between different spatial frequencies. In another study, the decay of features in VWM was investigated using signal detection theory methods such as psychophysical classification images and internal noise estimation. A modified version of the same-different memory task was employed, showing that VWM decay was not due to a systematic loss of some stimulus features but was caused by uniformly increasing random internal noise51. Altogether, these studies support the notion that memory decay is critical in VWM performance. This may suggest that faster decay contributes to the poor VWM observed in SCZ patients in this study.

Effect of tACS on SCZ VWM

Concerning tACS, our study found that applying theta tACS to the right frontoparietal cortices led to an enhancement in overall VWM performance in low-performers, but not among high-performers. Furthermore, we observed no interaction between tACS and cues. This suggests that the facilitative effects of theta tACS in low-performers are unlikely to be VWM stage-specific and, thus, not the same as the benefits of retro-cue. It is more likely that tACS induced an overall increase in attention, which consequently enhanced VWM performance. This would imply that the encoding stage, though not deliberately tested in our design, was perhaps also enhanced in our participants and trickled down to subsequent retention and retrieval stages, otherwise a tACS-induced improvement would not have been possible. This is consistent with our previous findings in healthy participants as well21.

The concept that frontoparietal theta tACS enhances visual attention aligns with recent theories suggesting a theta frequency rhythm for visual attention sampling. Specifically, Fiebelkorn and Kastner52 proposed a rhythmic theory of attention, stating that intrinsic theta rhythms help resolve potential functional conflicts by periodically adjusting the operational connections between higher-order brain regions and sensory or motor areas. This rhythmic adjustment alternates between endorsing sensory sampling at a behaviorally relevant location and facilitating shifts to new locations. Given that theta rhythmic activities occur in multiple brain regions, these theta-dependent attentional states are both region-specific and cell-type-specific. In the first state, associated with sensory regions and called “sampling,” enhanced beta oscillatory activities linked to theta from the frontal eye field mitigate attentional shifts, while increased theta-coupled gamma-band activities from the lateral intra-parietal area enhance sensory processing, improving signal detection at relevant locations. In the second state, associated with motor regions and called “shifting,” increased theta-coupled alpha-band activities in parietal areas inhibit visual processing, thus facilitating attentional shifts. This attentional account not only explains our tACS results (i.e., nonselective improvement) well, its highlighted pathway (i.e., frontal eye fields and lateral intra-pareital area) also matches with our stimulated areas (i.e., F4 and P4). Furtherore, this account is also consistent with previous research that has demonstrates the importance of attentional amplification and attentional shifts in VWM (e.g. refs. 36,53–55).

Aside from attention, a more WM-specific account for our data here is the theta-gamma code model originally proposed by Lisman and Jensen34. These authors proposed a theta-gamma coupling hypothesis for WM, where theta envelop is a holistic memory representation that encompasses many features that are neutrally represented in gamma frequency. As such, this idea predicts that the lower the theta, the higher WM capacity. Indeed, Bender et al. found that low theta tACS (~4 Hz) does improve people’s VWM performance better than high theta tACS (~6 Hz). Although we think this idea is too VWM-specific to explain our stage-nonspecific improvement in low-performers, and that it heavily involves regions that we did not stimulate in this study such as the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe, this account is nonetheless consistent with our observed results so far. Overall, these competing hypotheses highlight the importance of understanding the role oscillatory mechanisms in VWM, especially theta oscillations, in both healthy and diseased. To this end, our findings here support the notion of using tACS in improving SCZ patients’ VWM performance, and possibly implicate that it may be possible to tailor cognitive enhancement strategies in therapeutic interventions based on individual baseline performance levels.

To explore potential contributors to the varying cognitive deficits and facilitative effects observed between low-performers and high-performers, we conducted analyses on several confounding factors, including age, sex, age of onset, duration of illness, education, BMI, daily CPZ equivalent, PANSS scores, BDI scores, full IQ scores, working memory scores, and MoCA scores. However, none of these factors exhibited statistically significant differences in distribution between the two groups. It’s noteworthy that antipsychotics with anticholinergic and/or antihistamine effects may impair cognitive function in SCZ patients56, potentially associated with a higher daily CPZ equivalent in low-performers, albeit with marginal significance. Nevertheless, low-performers did not display differences from high-performers in other cognitive assessments, including full IQ scores, working memory scores, and MoCA scores. Consequently, the underlying factor or mechanism contributing to the disparity in baseline performance between these two groups remains unclear based on the findings of this study.

Limitations

There are some limitations in the present study. First, given the nature of this study as a one-time crossover with a double-blind design, the duration of the cognitive facilitative effects of tACS among low-performers remains uncertain. Determining the optimal intensity, frequency, and duration of stimulation for cognitive enhancement requires further investigation. Additionally, while maintenance stimulation may sustain augmented VWM performance, its impact on daily functioning and life satisfaction of patients remains unclear. Therefore, prospective studies employing maintenance tACS stimulation are warranted to address these questions and provide more comprehensive insights into the potential benefits of tACS in improving cognitive function and overall well-being in SCZ patients. Second, the small sample size and single-hospital recruitment restrict the generalizability of the findings, as the participants were solely chronic and stable SCZ patients from psychiatric outpatient and rehabilitation wards. Consequently, the results may not apply to other SCZ patient populations, including those with acute-onset, untreated cases, or community patients not under hospital follow-up. Third, although we have specifically stimulated areas that are notably associated with VWM, it is possible that tACS may have enhanced other cognitive processes (e.g., inhibitory control) that are crucial to VWM (e.g., distractor suppression) but are not in and of themselves VWM processes. Lastly, the inclusion of SCZ patients who were not drug-naive introduces the potential influence of medication on cognitive deficits and the modulatory effects of tACS, despite efforts to control for this through calculating daily CPZ equivalents. Future studies should aim to address these limitations by expanding the sample size, diversifying participant sources, and considering the influence of medication more comprehensively in the study design and analysis.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the mechanisms underlying the impact of theta tACS applied to the right DLPFC and PPC on VWM processing. Our findings reveal that low-performing SCZ patients’ VWM performance significantly benefited from both retro-cues and right frontoparietal theta tACS. Specifically, maintenance-stage cues—both early and late—substantially improved outcomes, suggesting that these patients’ VWM impairments are primarily due to difficulties in memory maintenance, such as rapid decay, rather than retrieval issues. Conversely, the broad efficacy of tACS, independent of the cue stage, indicates a domain-general enhancement of visual attention that supports overall VWM processes. Future research is necessary to elucidate the underlying factors or mechanisms contributing to baseline performance disparities, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of cognitive deficits in SCZ patients and the potential therapeutic benefits of tACS.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by research grants provided by Taipei Medical University-Shuang Ho Hospital (111TMU-SHH-30), National Taiwan University (NTU-RPG-113L7324, NTU-CDP-113L7775), Ministry of Education (Higher Education Sprout Project) and National Sciences and Technology Council of Taiwan (112-2410-H-002-252, 109-2423-H-002-004-MY4, 113-2628-H-002-013-MY3).

Author contributions

J.K.W.: experiment design, methods, data collection, data analysis, writing – original draft, writing – revision, and funding; P.P.S.: experiment design, methods, data collection, data analysis, and writing – original draft; H.L.K.: methods and data collection; Y.H.L.: experiment design, methods, data analysis, writing – revision, and funding; Y.R.C.: methods and data collection; C.Y.L.: methods and data collection; P.T.: experiment design, methods, writing – original draft, writing – revision, and funding.

Data availability

Data are not publicly shared as our consent form did not ask for patients’ permission to share their data online or with other researchers.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jiunn-Kae Wang, Prangya Parimita Sahu.

References

- 1.Insel, T. R. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature468, 187–193 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saha, S. et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med.2, e141 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keefe, R. S. & Fenton, W. S. How should DSM-V criteria for schizophrenia include cognitive impairment? Schizophr. Bull.33, 912–920 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lett, T. A. et al. Treating working memory deficits in schizophrenia: a review of the neurobiology. Biol. Psychiatry75, 361–370 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyson, P. J., Laws, K. R., Roberts, K. H. & Mortimer, A. M. A longitudinal analysis of memory in patients with schizophrenia. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol.27, 718–734 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, J. D., Braver, T. S. & O’Reilly, R. C. A computational approach to prefrontal cortex, cognitive control and schizophrenia: recent developments and current challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond.351, 1515–1527 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman-Rakic, P. S. Psychopathology and the Brain. (eds. Carroll, B. J., Barrett, J. E.). pp. 1–23 (Raven Press, 1991).

- 8.Park, S. & Gooding, D. C. Working memory impairment as an endophenotypic marker of a schizophrenia diathesis. Schizophr. Res.: Cogn.1, 127–136 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baddeley, A. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory? Trends Cogn. Sci.4, 417–423 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazzaley, A. & Nobre, A. Top-down modulation: bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci.16, 129–135 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, H. Neural activity during working memory encoding, maintenance, and retrieval: A network‐based model and meta‐analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp.40, 4912–4933 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons, D. J. & Rensink, R. A. Change blindness: past, present, and future. Trends Cogn. Sci.9, 16–20 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nobre, A. & Oreilly, J. Time is of the essence. Trends Cogn. Sci.8, 387–389 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin, I. C. & Nobre, A. C. Orienting attention to locations in internal representations. J. Cogn. Neurosci.15, 1176–1194 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang, C., Tseng, P., Huang, K. & Yeh, Y. Prepared or not prepared: top-down modulation on memory of features and feature bindings. Acta Psychol.141, 327–335 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang, C., Tseng, P. & Wu, Y. Effect of decision load on whole-display superiority in change detection. Atten. Percept. Psychophys.77, 749–758 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gathercole, S. Cognitive approaches to the development of short-term memory. Trends Cogn. Sci.3, 410–419 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbey, A., Koenigs, M. & Grafman, J. Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex49, 1195–1205 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis, C. & D’Esposito, M. Persistent activity in the prefrontal cortex during working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci.7, 415–423 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feredoes, E., Heinen, K., Weiskopf, N., Ruff, C. & Driver, J. Causal evidence for frontal involvement in memory target maintenance by posterior brain areas during distracter interference of visual working memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA108, 17510–17515 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahu, P. P. & Tseng, P. Frontoparietal Theta tacs nonselectively enhances encoding, maintenance, and retrieval stages in visuospatial working memory. Neurosci. Res.172, 41–50 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng, P. et al. Posterior parietal cortex mediates encoding and maintenance processes in change blindness. Neuropsychologia48, 1063–1070 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, M. et al. Evaluating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and PPC in memory-guided attention with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Front. Hum. Neurosci.10.3389/fnhum.2018.00236 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Yan, Y., Wei, R., Zhang, Q., Jin, Z., & Li, L. Differential roles of the dorsal prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in visual search: a TMS study. Sci. Rep. 10.1038/srep30300 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Todd, J. & Marois, R. Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human PPC. Nature428, 751–754 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon, J. H. et al. Association of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dysfunction with disrupted coordinated brain activity in schizophrenia: relationship with impaired cognition, behavioral disorganization, and global function. Am. J. Psychiatry165, 1006–1014 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chai, X. J. et al. Abnormal medial prefrontal cortex resting-state connectivity in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology36, 2009–2017 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer-Lindenberg, A. S. et al. Regionally specific disturbance of dorsolateral prefrontal–hippocampal functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry62, 379 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vera-Montecinos, A. et al. Analysis of networks in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in chronic schizophrenia: relevance of altered immune response. Front. Pharmacol.10.3389/fphar.2023.1003557 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Koch, G. et al. Connectivity between posterior parietal cortex and ipsilateral motor cortex is altered in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry64, 815–819 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hahn, B. et al. Posterior parietal cortex dysfunction is central to working memory storage and broad cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci.38, 8378–8387 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alekseichuk, I., Turi, Z., Amador de Lara, G., Antal, A. & Paulus, W. Spatial working memory in humans depends on theta and high gamma synchronization in the prefrontal cortex. Curr. Biol.26, 1513–1521 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Canolty, R. et al. High gamma power is phase-locked to theta oscillations in human neocortex. Science313, 1626–1628 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lisman, J. & Jensen, O. The theta-gamma neural code. Neuron77, 1002–1016 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riddle, J., Scimeca, J., Cellier, D., Dhanani, S. & D’Esposito, M. Causal evidence for a role of theta and alpha oscillations in the control of working memory. Curr. Biol.30, 1748–1754.e4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tseng, P. et al. The critical role of phase difference in gamma oscillation within the temporoparietal network for binding visual working memory. Sci. Rep.10.1038/srep32138 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Tseng, P., Iu, K.-C. & Juan, C.-H. The critical role of phase difference in theta oscillation between bilateral parietal cortices for visuospatial working memory. Sci. Rep. 10.1038/s41598-017-18449-w (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Schmiedt, C. et al. Event-related theta oscillations during working memory tasks in patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Cogn. Brain Res.25, 936–947 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton, H. K. et al. Impaired potentiation of theta oscillations during a visual cortical plasticity paradigm in individuals with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590567. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Kallel, L., Mondino, M. & Brunelin, J. Effects of theta-rhythm transcranial alternating current stimulation (4.5 Hz-tacs) in patients with clozapine-resistant negative symptoms of schizophrenia: A case series. J. Neural Transm.123, 1213–1217 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sreeraj, V. S. et al. Feasibility of online neuromodulation using transcranial alternating current stimulation in schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychol. Med.39, 92–95 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pinninti, N. R., Madison, H., Musser, E. & Rissmiller, D. MINI International Neuropsychiatric Schedule: clinical utility and patient acceptance. Eur. Psychiatry18, 361–364 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, B. J., Lan, T. H., Hu, T. M., Lee, S. M. & Liou, J. Y. Validation of a five-factor model of a Chinese Mandarin version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (CMV-PANSS) in a sample of 813 schizophrenia patients. Schizophr. Res.169, 489–490 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu, M. L., Che, H. H., Chang, S. W. & Shen, W. W. Reliability and validity of the chinese version of the beck depression inventory‑II. Chin. Ment. Health J.25, 476–480 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai, C. F. et al. Psychometrics of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and its subscales: validation of the Taiwanese version of the MoCA and an item response theory analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr.24, 651–658 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–fourth Edition (Pearson, 2008).

- 47.Woods, S. W. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychiatry64, 663–667 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juan, C.-H. et al. Elucidating the interactions between individual differences and noninvasive brain stimulation effects in visual working memory by using tDCS, tacs and EEG. Brain Stimul. 10.1016/j.brs.2017.04.019. (2017).

- 49.Harvey L. D. Human Memory And Cognitive Capabilities (eds. Klix F. & Hagendorf H.). Vol. 1, p. 173–187. (Elsevier Science, 1986).

- 50.Gao, Z. & Bentin, S. Coarse-to-fine encoding of spatial frequency information into visual short-term memory for faces but impartial decay. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform.37, 1051–1064 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuuramo, C., Saarinen, J. & Kurki, I. Forgetting in visual working memory: Internal noise explains decay of feature representations. J. Vis.22, 8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiebelkorn, I. C. & Kastner, S. A rhythmic theory of attention. Trends Cogn. Sci.23, 87–101 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tas, A. C., Luck, S. J. & Hollingworth, A. The relationship between visual attention and visual working memory encoding: a dissociation between covert and overt orienting. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform.42, 1121 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Theeuwes, J., Kramer, A. F. & Irwin, D. E. Attention on our mind: the role of spatial attention in visual working memory. Acta Psychol.137, 248–251 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tseng, P. et al. Unleashing potential: transcranial direct current stimulation over the right posterior parietal cortex improves change detection in low-performing individuals. J. Neurosci.32, 10554–10561 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haddad, C., Salameh, P., Sacre, H., Clément, J. P. & Calvet, B. Effects of antipsychotic and anticholinergic medications on cognition in chronic patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry23, 61 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are not publicly shared as our consent form did not ask for patients’ permission to share their data online or with other researchers.