Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal disease (MSD) is a major cause of disability among older adults, and understanding the role of physical activity (PA) in preventing these conditions is crucial. This study aimed to explore the association between PA levels and MSD risk among adults aged 45 and above, clarify the dose‒response relationship, and provide tailored guidelines.

Methods

Using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a cross-sectional analysis was conducted on 15,909 adults aged 45 and over. The study population was divided into MSD (n = 7014) and nMSD (n = 8895) groups based on musculoskeletal health status. PA levels were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and categorized into low intensity physical activity (LIPA), moderate vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and vigorous physical activity (VPA). Multivariable logistic regression models and restricted cubic spline regression were used to examine the relationship between PA levels and MSD risk in middle-aged and older adults. Sensitivity analyses and stratified analyses were also performed.

Results

The main outcome measures were musculoskeletal diseases prevalence and PA levels. MVPA and VPA reduced MSD risk by 19% [OR = 0.81, 95% CI (0.72, 0.90), P < 0.001] and 12% [OR = 0.88, 95% CI (0.79, 0.98), P < 0.05], respectively. What’s more, after adjusting for confounding factors, VPA increased risk by 32% [OR = 1.32, 95% CI (1.04, 1.66), P < 0.05]. The relationship was nonlinear, showing a U-shaped pattern with age and hypertension status as significant moderators. The optimal PA energy expenditure was identified as approximately 1500 metabolic equivalents of tasks (METs) per week for adults aged 45–74, 1400 METs per week for those aged 75 and above, and 1600 METs per week for hypertensive adults aged 45 and older.

Conclusions

For adults aged 45 years and older, VPA significantly increases the risk of MSD. Adults aged 45 years and older should adjust their weekly METs based on their age. Additionally, those with hypertension should moderately increase their weekly METs to promote optimal musculoskeletal health.

Keywords: Middle-aged and older adults, Musculoskeletal disease, Physical activity, Metabolic equivalents, CHARLS

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disease (MSD) is a leading cause of disability globally, with high prevalence and burden highlighted by Global Burden of Disease studies [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 1.71 billion people globally suffer from musculoskeletal conditions [3–5]. In China, MSD is a top cause of disability and often co-occur with other non-communicable diseases, heightening their risk [6–8]. Symptoms such as chronic lower back pain and severe mobility restrictions lead to early retirement, reduced quality of life, and limited social participation. Factors like work duration, poor posture, repetitive movements, and heavy lifting have been linked to MSD prevalence [9–11], but whether other factors exist still requires further research. In addition, age is also a significant factor influencing MSD. With the increasing aging population in China, exploring the factors affecting MSD in middle-aged and older adults holds substantial social value and significance [12].

Physical activity (PA) is key in preventing and alleviating MSD, yet the dose-response relationship between PA levels and MSD remains unclear. Longitudinal studies have suggested moderate vigorous physical activity (MVPA) to vigorous physical activity (VPA) benefited health more than low intensity physical activity (LIPA), with optimal benefits at recommended activity levels [13, 14]. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported additional benefits from engaging in more than 300 min of MVPA per week [15] and the potential increased risk of musculoskeletal injuries associated with higher levels of PA [16]. According to WHO’s 2020 guidelines, adults can exceed 300 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity per week, or combine both, to gain additional health benefits [17]. For middle-aged and older adults, the most effective intensity of PA to reduce the risk of MSD remains to be explored. Identifying the optimal level of PA is essential for mitigating MSD risk.

This study aimed to quantify the dose-response relationship between PA levels and MSD risk in the adults aged 45 years and older to find the optimal PA level that reduces MSD risk. The hypothesis of this study is that both LIPA and VPA do not provide significant benefits to musculoskeletal health in middle-aged and older adults.

Materials and methods

Study population

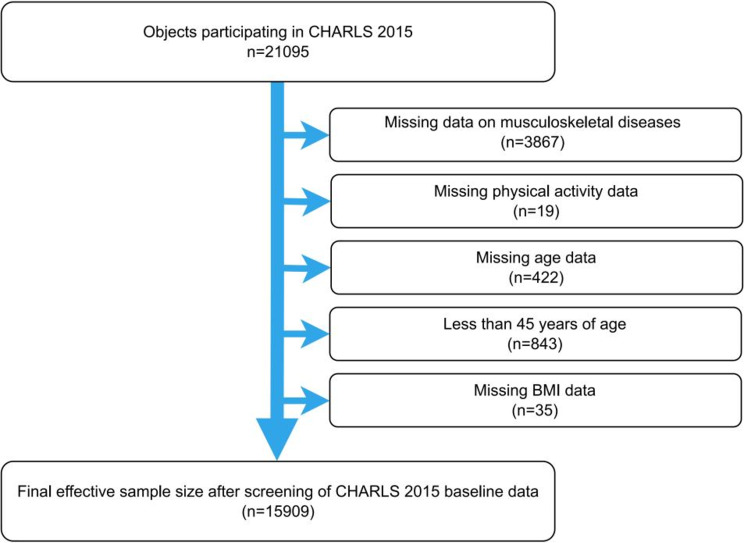

This study utilized data from the 2015 wave of CHARLS, which included participants aged 45 and older from various regions across China. The inclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: (1) aged 45 years and above and (2) provided informed consent before participation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) missing MSD information (2) missing PA data (3) missing age data (4) age below 45 (5) missing body mass index (BMI) data. Ultimately, 15,909 participants were included in the analysis. Figure 1 outlines the selection process.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant selection. Figure 1 presents the selection process for participants from the CHARLS 2015 cohort, starting with 21,095 individuals and detailing the exclusions that led to the final inclusion of 15,909 participants for the cross-sectional analysis. Abbreviations: CHARLS, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; BMI, Body mass index

The initial analysis involved 21,095 individuals [18]. A total of 15,909 participants aged 45 and above were included, with most in the 45–59 and 60–74 age groups. The sample was fairly balanced by gender, and the majority had a primary education level or below. Key demographic characteristics such as age, gender, cohabitation status, and BMI are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the demographic distribution of participants (N=15909) and univariate logistic regression analyses

| nMSD (n = 8895) |

MSD (n = 7014) |

X2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years | 624.29 | < 0.001 | ||

| 45–59 | 5064 (56.93%) | 2676 (38.15%) | ||

| 60–74 | 3373 (37.92%) | 3528 (50.30%) | ||

| ≥ 75 | 458 (5.15%) | 810 (11.55%) | ||

| Genders | 102.88 | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 4543 (51.07%) | 3015 (42.99%) | ||

| Female | 4352 (48.93%) | 3999 (57.01%) | ||

| Cohabitation status | 174.81 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 914 (10.28%) | 1226 (17.48%) | ||

| Yes | 7981 (89.72%) | 5788 (82.52%) | ||

| Education | 209.71 | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary and below | 2716 (60.92%) | 3389 (74.88%) | ||

| junior high school | 1105 (24.79%) | 784 (17.32%) | ||

| High school and above | 637 (14.29%) | 353 (7.80%) | ||

| BMI/kg/m2 | 42.43 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 18.5 | 458 (5.16%) | 425 (7.40%) | ||

| 18.5–24.9 | 5160 (58.17%) | 3327 (57.91%) | ||

| 25–29.9 | 2794 (31.50%) | 1648 (28.69%) | ||

| ≥ 30 | 458 (5.16%) | 345 (6.01%) | ||

| Smoking | 12.97 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 4885 (54.92%) | 4052 (57.78%) | ||

| Yes | 4009 (45.08%) | 2961 (42.22%) | ||

| Alcohol | 72.35 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 5496 (61.86%) | 4790 (68.35%) | ||

| Yes | 3389 (38.14%) | 2218 (31.65%) | ||

| Sleep/hours | 141.81 | < 0.001 | ||

| < 6 | 4079 (46.94%) | 3658 (56.14%) | ||

| 6–9 | 4190 (48.22%) | 2514 (38.58%) | ||

| ≥ 9 | 420 (4.83%) | 344 (5.28%) | ||

| Hypertension | 245.41 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 7302 (82.09%) | 5025 (71.64%) | ||

| Yes | 1593 (17.91%) | 1989 (28.36%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 38.00 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 8156 (91.69%) | 6228 (88.79%) | ||

| Yes | 739 (8.31%) | 786 (11.21%) | ||

| Diabetes/Hyperglycemia | 49.36 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 8499 (95.55%) | 6521 (92.97%) | ||

| Yes | 396 (4.45%) | 493 (7.03%) | ||

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.0039 | 0.95 | ||

| No | 6779 (92.99%) | 4398 (93.02%) | ||

| Yes | 511 (7.01%) | 330 (6.98%) | ||

| Medicine | 1122.78 | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 6749 (75.87%) | 3527 (50.29%) | ||

| Yes | 2146 (24.13%) | 3487 (49.71%) | ||

| Floors | 29.56 | < 0.001 | ||

| 1 | 3739 (84.44%) | 3111 (88.18%) | ||

| 2 | 132 (2.98%) | 108 (3.06%) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 557 (12.58%) | 309 (8.76%) | ||

| Physical activity | 1.29 | 0.26 | ||

| No | 4499 (50.58%) | 3484 (49.67%) | ||

| Yes | 4396 (49.42%) | 3530 (50.33%) | ||

| Physical activity level | 15.144 | < 0.001 | ||

| LIPA | 1670 (37.99%) | 1482 (41.98%) | ||

| MVPA | 1245 (28.32%) | 892 (25.27%) | ||

| VPA | 1481 (33.69%) | 1156 (32.75%) |

Abbreviation: LIPA, Low intensity physical activity. MVPA, Moderate vigorous physical activity. VPA, Vigorous physical activity

Variable definition

Assessment of PA

Research suggested that a binary classification of PA may obscure specific U-shaped relationships with outcomes [19]. This study used a three-tier classification: (1) VPA such as carrying heavy loads, aerobic exercises; (2) MVPA such as carrying light objects, brisk walking; (3) LIPA such as walking and leisurely strolling.

PA criteria were based on CHARLS data, recording days per week participants engaged in at least 10 min of PA and the duration of daily activities. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) is one of the most widely used instruments globally for measuring PA levels in adults, and empirical studies in China have demonstrated its good validity and reliability [20]. CHARLS categorized daily activity durations into five levels (0 min, 10–29 min, 30–119 min, 120–239 min, ≥ 240 min) [21]. Following Ainsworth et al. [22], metabolic equivalents of tasks (METs) were assigned: LIPA 3.3 METs, MVPA 4.0 METs, and VPA 8.0 METs. Weekly PA energy expenditure was calculated as METs × daily activity duration (min) × number of active days per week [23].PA levels were classified per the IPAQ standards: LIPA (< 600 METs per week), MVPA (600–3000 METs per week), and VPA (> 3000 METs per week) [24, 25].

Outcome variable

MSD in this study encompassed conditions affecting bones, muscles, joints, and tendons, including hip fractures, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), rheumatic diseases, and sarcopenia. Chronic musculoskeletal pain could be classified as either primary or secondary, with secondary pain stemming from underlying conditions such as osteoarthritis and RA [26, 27]. Sarcopenia, as defined by the 2019 Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) criteria [28], was characterized by grip strength below 28.0 kg for males or 18.0 kg for females, or a time of ≥ 12 s to stand from a chair five times. In this study, participants were classified as having MSD if they reported a physician’s diagnosis of hip fracture, arthritis, rheumatic disease, or were identified as having potential sarcopenia based on the AWGS criteria in the CHARLS dataset.

Covariates

Demographic variables

Demographic variables included gender, age, cohabitation status, and educational level.

Lifestyle variables

Lifestyle variables included smoking, alcohol consumption, BMI, sleep duration, number of floors climbed daily, and medication use. BMI categories were defined as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m²), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²), and obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m²). Sleep duration refered to nightly sleep time. Floor count was based on steps climbed daily. Medication use was noted for conditions such as dyslipidemia, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, kidney disease, gastric diseases, heart disease, memory-related diseases, arthritis, or rheumatism.

Chronic health conditions

Chronic health conditions included hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes/hyperglycaemia, and metabolic syndrome. Hypertension, diabetes/hyperglycaemia were reported through medical diagnosis. If the participants met three or more of the following criteria: central obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, high triglycerides, and low HDL-C—they were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome [29].

Statistical analyses

Data cleaning and statistical analyses were performed using R 4.3.1 and SPSS 27.0. Categorical variables were described as n (%), with group comparisons conducted using Chi-square tests or Chi-square tests for trend. Univariate logistic regression assessed initial associations between exposure factors and MSD. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between PA levels and MSD. To verify the stability of the results, multivariable logistic regression modeling was constructed, with stepwise adjustments for confounding factors: demographic variables, lifestyle variables, and chronic disease conditions. Interaction terms between PA levels and key covariates were tested individually in separate models to assess their significance. For interaction terms that were statistically significant, we conducted stratified analyses to explore these relationships further. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression, fitted with six quantiles of PA levels, explored potential non-linear relationships between PA levels and MSD risk. The significance level was set at p = 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Demographic characteristics and univariate logistic regression analyses

This study included a total of 15,909 participants, with an average age of 60.38 years. There were 7,558 males and 8,351 females. The prevalence of MSD was 44.09%, with 7,014 reported cases. Significant differences were found between participants with and without MSD in terms of age, gender, cohabitation status, education level, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, sleep duration, number of floors climbed, medication use, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes/hyperglycemia, and PA levels (P < 0.001). However, no significant differences were observed regarding metabolic syndrome prevalence or PA engagement between the MSD and non-MSD groups (P > 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 1.

Multivariable logistic regression

Multivariable logistic regression revealed that female participants aged ≥ 60 years with hypertension, diabetes/hyperglycaemia, dyslipidemia, and long-term medication use had a higher risk of MSD (P < 0.001). Conversely, those living with a partner, with higher education, a BMI of 18.5–29.9 kg/m², 6–9 h of sleep, and climbing ≥ 3 floors daily showed a lower MSD risk (P < 0.05). Compared to participants engaged in LIPA, those with MVPA and VPA experienced a 19% [OR = 0.81, 95% CI (0.72, 0.90), P < 0.001] and 12% [OR = 0.88, 95% CI (0.79, 0.98), P < 0.05] reduction in MSD risk, respectively. After adjusting for covariates, no significant differences in MSD risk were found for smoking, alcohol consumption, or a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² (P > 0.05). Detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of a multivariable logistic regression of factors influencing MSD

| Statistics n(%) | OR | 95%CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/years | ||||

| 45–59 | 7740(48.65%) | Ref. | ||

| 60–74 | 6901(43.38%) | 1.98 | 1.85, 2.12 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 75 | 1268(7.97%) | 3.35 | 2.96, 3.79 | < 0.001 |

| Genders | ||||

| male | 7558(47.51%) | Ref. | ||

| female | 8351(52.49%) | 1.38 | 1.30, 1.47 | < 0.001 |

| Cohabitation status | ||||

| No | 2140(13.45%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 13,769(86.55%) | 0.54 | 0.49, 0.59 | < 0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| primary and below | 6105(67.95%) | Ref. | ||

| junior high school | 1889(21.03%) | 0.57 | 0.51, 0.63 | < 0.001 |

| high school and above | 990(11.02%) | 0.44 | 0.39, 0.51 | < 0.001 |

| BMI/kg/m2 | ||||

| < 18.5 | 883(6.04%) | Ref. | ||

| 18.5–24.9 | 8487(58.07%) | 0.69 | 0.60, 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| 25–29.9 | 4442(30.39%) | 0.64 | 0.55, 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 30 | 803(5.49%) | 0.81 | 0.67, 0.98 | 0.034 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 8937(56.18%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 6970(43.82%) | 0.89 | 0.84, 0.95 | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol | ||||

| No | 10,286(64.72%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 5607(35.28%) | 0.75 | 0.70, 0.80 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep/hours | ||||

| < 6 | 7737(50.88%) | Ref. | ||

| 6–9 | 6704(44.09%) | 0.67 | 0.63, 0.72 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 9 | 764(5.02%) | 0.91 | 0.79, 1.06 | 0.234 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 12,327(77.48%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3582(22.52%) | 1.81 | 1.68, 1.96 | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| No | 14,384(90.41%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 1525(9.59%) | 1.39 | 1.25, 1.55 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes/Hyperglycemia | ||||

| No | 15,020(94.41%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 889(5.59%) | 1.62 | 1.42, 1.86 | < 0.001 |

| Medicine | ||||

| No | 10,276(64.59%) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 5633(35.41%) | 3.11 | 2.91, 3.33 | < 0.001 |

| Floors | ||||

| 1 | 6850(86.10%) | Ref. | ||

| 2 | 240(3.02%) | 0.98 | 0.76, 1.27 | 0.899 |

| ≥ 3 | 866(10.88%) | 0.67 | 0.58, 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| PA level | ||||

| LIPA | 3152(39.77%) | Ref. | ||

| MVPA | 2137(26.96%) | 0.81 | 0.72, 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| VPA | 2637(33.27%) | 0.88 | 0.79, 0.98 | 0.016 |

Abbreviation: PA, Physical activity. LIPA, Low intensity physical activity. MVPA, Moderate vigorous physical activity. VPA, Vigorous physical activity

Multivariable logistic regression modeling

Using multivariable logistic regression modeling, Model I: was adjusted for demographic variables (e.g., age, gender); Model II: added lifestyle variables (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption); Model III: incorporated chronic disease conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes). Results showed that adults aged 45 and older engaged in VPA had a 32% increased risk of MSD [OR = 1.32, 95% CI (1.05, 1.67), P < 0.05] compared to those engaged in LIPA. This association persisted even after adjusting for chronic disease conditions, with the same group showing a 32% increased risk [OR = 1.32, 95% CI (1.04, 1.66), P < 0.05]. The consistent results across different covariate adjustments highlight the impact of VPA on MSD risk. Full details are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression modeling of the effect of PA levels on MSD in adults aged 45 years and older

| Exposure | Non-adjustment | Model I | Model II | Model III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | OR(95%CI) | P-value | |

| PA level | ||||||||

| LIPA | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| MVPA | 0.81 (0.72,0.90) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (0.93,1.26) | 0.319 | 1.25 (1.00,1.58) | 0.054 | 1.26 (1.00,1.58) | 0.052 |

| VPA | 0.88(0.79,0.98) | 0.016 | 1.16 (1.00,1.34) | 0.055 | 1.32 (1.05,1.67) | 0.018 | 1.32 (1.04,1.66) | 0.021 |

Model I adjusted for: Age, Gender, Cohabitation status, Education

Model II adjusted for: Age, Gender, Cohabitation status, Education, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol, Medicine, Floors, Sleep

Model III adjusted for: Age, Gender, Cohabitation status, Education, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol, Medicine, Floors, Sleep, Hypertension, Dyslipidaemia, Diabetes/Hyperglycemia

Abbreviation: PA, Physical activity. LIPA, Low intensity physical activity. MVPA, Moderate vigorous physical activity. VPA, Vigorous physical activity

Interaction and stratified analysis of the relationship between PA and MSD

Interaction analysis revealed that age (P = 0.037) and hypertension (P = 0.014) significantly moderated the relationship between PA levels and MSD risk. However, no significant interactions were found for genders, cohabitation status, education, BMI, smoking, alcohol, floors, medicine, dyslipidemia, diabetes/hyperglycaemia (P > 0.05). Results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Interaction analysis of different variables on PA levels and MSD

| Modifier | Min P.terms | P-interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | < 0.0001 | 0.014* |

| Age | < 0.0001 | 0.037* |

| Alcohol | < 0.0001 | 0.075 |

| Diabetes/Hyperglycemia | < 0.0001 | 0.193 |

| Cohabitation status | < 0.0001 | 0.204 |

| Medicine | < 0.0001 | 0.276 |

| BMI | < 0.0001 | 0.312 |

| Dyslipidemia | < 0.0001 | 0.448 |

| Education | < 0.0001 | 0.732 |

| Smoking | 0.0001 | 0.789 |

| Floors | 0.0017 | 0.867 |

| Sleep | < 0.0001 | 0.949 |

| Genders | < 0.0001 | 0.965 |

*P < 0.05 Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index

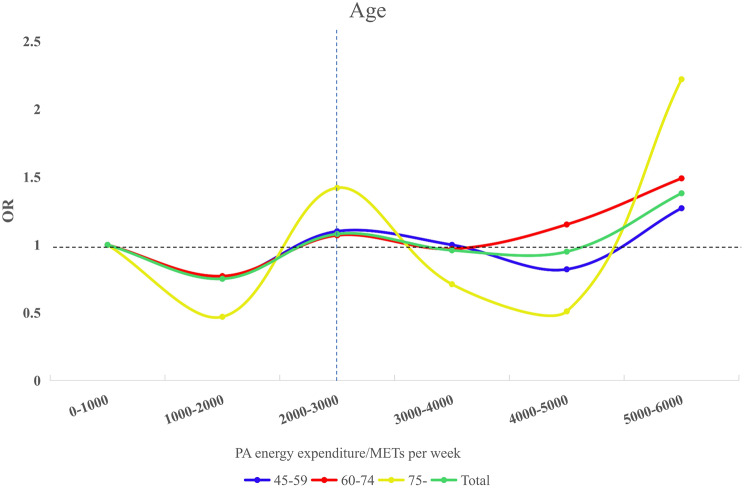

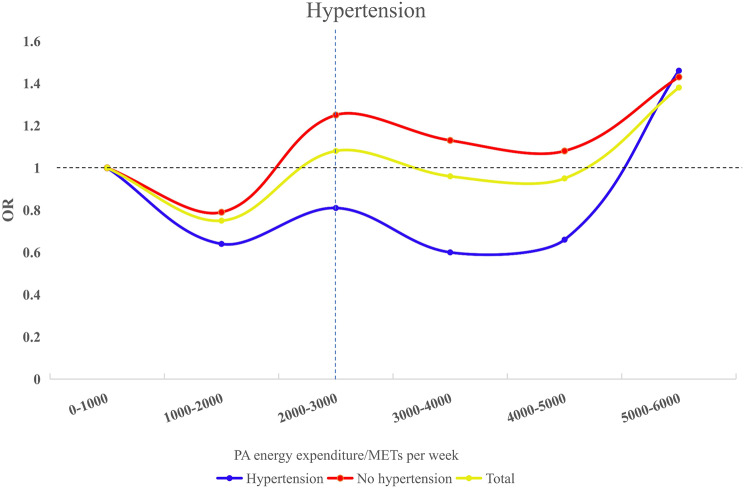

In the stratified age analysis, individuals aged 60–74 engaged in VPA showed a 49% higher risk of MSD compared to those engaged in LIPA [OR = 1.49, 95% CI (1.09, 2.05),P < 0.05]. No significant associations were observed for PA levels and MSD risk in the 45–59 or 75 + age groups (P > 0.05). Among those with normal blood pressure, MVPA and VPA were associated with a 38% [OR = 1.38, 95% CI (1.04, 1.81), P < 0.05] and 35% [OR = 1.35, 95% CI (1.03, 1.76), P < 0.05] increased MSD risk, respectively, compared to LIPA. However, PA levels did not significantly impact MSD risk in hypertensive individuals (P > 0.05). These findings, illustrated in Fig. 2, underscore the complex relationship between PA, age, and blood pressure in MSD risk.

Fig. 2.

Stratified analysis of the effect of age and hypertension on PA levels MSD. Abbreviations: PA, Physical activity; LIPA, Low intensity physical activity; MVPA, Moderate vigorous physical activity; VPA, Vigorous physical activity; OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval; Adjusted for Genders, Cohabitation status, Education, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol, Sleep, Dyslipidemia, Diabetes/Hyperglycemia, Medicine, and Floors

RCS analysis stratified by age and blood pressure status

RCS analysis indicated a nonlinear relationship between PA and MSD risk. Categorizing PA energy expenditure into six quantiles and analyzing age and blood pressure revealed varying effects across age groups.

Adjusting for covariates, RCS analysis showed a nonlinear relationship between PA and MSD risk across 0-6000 METs per week. The 45–59 and 60–74 age groups reached the lowest OR at 1500 METs per week, while those aged 75 and above had their lowest OR at 1400 METs per week. Figure 3 illustrates these interactions between PA and MSD risk.

Fig. 3.

Trends plots of age versus PA energy expenditure and MSD. Adjusted for Genders, Cohabitation status, Education, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol, Sleep, Dyslipidemia, Hypertension, Diabetes/Hyperglycemia, Medicine, and Floors. Abbreviations: OR, Odd ratio; METs: Metabolic equivalents of tasks

After adjusting for covariates, the no hypertension group aged 45 and above reached the lowest OR at 1400 METs per week, while the hypertension group had the lowest OR at 1600 METs per week. Figure 4 illustrates these dynamics between PA and MSD risk by blood pressure status.

Fig. 4.

Trends in blood pressure versus PA energy expenditure and MSD. Adjusted for Age, Genders, Cohabitation status, Education, BMI, Smoking, Alcohol, Sleep, Dyslipidemia, Diabetes/Hyperglycaemia, Medicine, and Floors. Abbreviations: OR, Odd ratio; METs: Metabolic equivalents of tasks

Discussion

The findings of this study generally supported the proposed hypothesis. For adults aged 45 years and older, engaging in VPA was associated with an increased risk of MSD, particularly in certain age groups. Therefore, individuals may consider adjusting their weekly METs according to their age. In addition, those with hypertension might benefit from moderately increasing their weekly METs to promote optimal musculoskeletal health, though further studies are needed to confirm this recommendation. The large, nationally representative sample in this study enhanced the reliability of our findings. This study using restricted cubic spline analysis allowed us to explore nonlinear relationships between PA and MSD, offering deeper insights into the data. The results of this study could serve as a reference guide for preventing MSD among the older population in China, providing a basis for selecting appropriate levels of physical activity.

In this study, data from the 2015 wave of CHARLS included a total of 15,909 participants aged 45 and above, with an MSD prevalence of 44.09%. This rate was slightly higher than the 40.6% reported by Feng Yang et al. among manufacturing workers [9] and the 37.9% reported by Bukhari Putsa et al. among office staff [11]. The MSD prevalence of 44.09% in this study may be attributed to the relatively older age of the participants, which could explain the difference. Studies have demonstrated that even minor changes, such as replacing sedentary time with MVPA, or VPA, can yield significant health benefits, with the greatest impact observed when VPA replaces sedentary behavior [30–32].

Our findings indicated that VPA significantly increases the risk of MSD. Previous research also suggested that both VPA and MVPA are associated with a higher risk of lumbar pain [33]. Bukhari Putsa et al. identified MVPA ≥ 150 min/week and working ≥ 4 h/day as risk factors for MSD [11]. Conversely, frequent transitions from sitting to standing can reduce MSD risk by over 30%. Moderate PA levels have also been shown to reduce non-specific low back pain [34]. However, some studies have also found that MVPA could improve health-related quality of life in older adults with MSD [35]. The observed discrepancies may be attributed to variations in the definitions of MVPA and VPA across different studies. Niederstrasser et al. highlighted inconsistencies in time accounting for MVPA [13]. Additionally, other variables in this study may have influenced the MSD risk factors.

This study identified significant interactions between age (P = 0.037) and hypertension (P = 0.014) with PA levels affecting MSD risk. Subgroup analysis showed that compared to LIPA, MVPA and VPA significantly increased MSD risk in adults aged 60–74. This counterintuitive finding may be attributed to several factors. First, the aging process is associated with decreased muscle mass, bone density, and recovery capacity, potentially amplifying the stress of VPA on the musculoskeletal system [36]. Second, older adults may lack proper exercise techniques or guidance, leading to improper form and increased injury risk [37]. Third, pre-existing health conditions common in this age group, may predispose individuals to MSD when engaging in VPA [38]. Finally, insufficient rest and recovery time between VPA may contribute to overuse injuries in this population [39]. No significant associations were found between PA levels and MSD risk in the 45–59 or 75 + age groups. This may be because the 45–59 group retains better physical function, reducing the differential impact of varying PA intensities on the musculoskeletal system [40, 41]. For individuals aged 75 and older, the impact of PA on health outcomes may differ due to age-related changes in physical function [42]. In this age group, PA’s primary effects might shift towards other physiological systems as physical function declines [43]. Concurrently, underlying health conditions often associated with advanced age can reduce tolerance for VPA. This decreased capacity for VPA may further modulate the relationship between PA intensity and health outcomes in this population [44–46]. Therefore, we suspected that the relationship between PA and MSD was not linear.

Evidence suggests a U-shaped relationship between PA levels and MSD risk in adults aged 45 years and older. In normotensive individuals, MVPA and VPA were associated with increased MSD risk [30–32]. Similarly, Hans Heneweer et al. observed a U-shaped correlation between PA and chronic low back pain [47]. Optimal PA levels appear to vary with age and health status: approximately 1500 METs per week for adults aged 45–74, 1400 METs per week for those 75 and older, and 1600 METs per week for adults aged 45 and older with hypertension. In both age and hypertension groups, the results indicated a similar decreasing trend in OR within the range of 3000–5000 METs. However, these levels significantly exceeded the WHO recommendations. Engaging in such high METs per week may increase the health burden on other systems, making it less feasible. This U-shaped trend suggested that PA exerted a threshold effect on MSD risk, with benefits peaking within a specific range but potentially increasing risk when these levels were exceeded [9, 46, 48–50].

This study explored the varying effects of different PA levels on MSD risk. MVPA can reduce the risk of MSD and improve the general health status of the population, whereas excessive PA heightens the risk of muscle and joint injuries. The findings of this study could serve as a supplement to some extent to the WHO guidelines and help fill gaps in the existing research on MSD. According to the WHO’s 2020 guidelines, adults could engage in more than 300 min of MVPA or 150 min of VPA per week, or an equivalent combination of both, to attain additional health benefits [17]. While PA generally benefits overall health, excessive levels may increase the risk of MSD, especially in certain populations [51–53]. Therefore, appropriate activity selection was crucial for optimizing musculoskeletal health outcomes.To address this, stakeholders should promote a balanced approach to exercise. Healthcare providers and fitness professionals can develop personalized, MVPA plans with regular assessments of joint health.

This study has certain limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of this study limits causal inference between PA levels and MSD. Second, self-reported PA estimates and MSD diagnoses may introduce bias, although the IPAQ is considered reliable [54–57]. Potential recall bias or misreporting could affect data accuracy, highlighting the need for future studies to incorporate objective clinical assessments. Moreover, our study did not differentiate between types of VPA, which may have varying impacts on musculoskeletal health [58]. Finally, the findings may be generalizable to similar populations of adults aged 45 years and older. In the future, more research could be conducted on different age groups.

Conclusions

Based on these findings, adults aged 45 years and older with MSD should generally avoid VPA and opt for MVPA instead. The optimal dosage of weekly METs for improving MSD may vary for different age groups. Individuals aged 45–74 should aim for approximately 1500 METs per week, while those aged 75 and older should target around 1400 METs per week, taking into account their potentially decreased tolerance for higher activity levels. For adults aged 45 years and older with hypertension, slightly higher activity levels of around 1600 METs per week may be the most appropriate threshold. These MSD-specific recommendations are designed to optimize health benefits while minimizing the risk of exacerbating musculoskeletal conditions. It is important to note that these guidelines are tailored for individuals with MSD and may not be applicable to the general population with other diseases.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the National School of Development at Peking University and the China Social Science Survey Center of Peking University for providing the CHARLS data utilized in this study.

Abbreviations

- CHARLS

China health and retirement longitudinal study

- MSD

Musculoskeletal disease

- WHO

World Health Organization

- PA

Physical activity

- LIPA

Low intensity physical activity

- MVPA

Moderate vigorous physical activity

- VPA

Vigorous physical activity

- IPAQ

International physical activity questionnaire

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- AWGS

Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia

- BMI

Body mass index

- RCS

Restricted cubic spline

- OR

Odds ratio

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- CLBP

Chronic low back pain

- METs

Metabolic equivalents of tasks

Author contributions

ZJP and ZT are co-first authors responsible for the study concept, design, and writing of this manuscript. SLQ, LZX, and LKL were responsible for the study concept, design, oversight, and revision. HCY, LCY, and other team members contributed to the concept, design, and editing of the manuscript. All authors participated in the conduct of the study and have approved the final version of the manuscript. SLQ is the guarantor.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

This study used data from the 2015 wave of the CHARLS. The dataset is publicly available through the CHARLS project website (https://charls.charlsdata.com/pages/Data/2015-charls-wave4/zh-cn.html).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The original CHARLS survey data were approved by the Peking University Institutional Review Board (No. IRB00001052-11015), with all participants having provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jieping Zhu and Ting Zhu co-first author.

References

- 1.Collaborators GBDM. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1684–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Disease GBD, Injury I, Prevalence C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N, Fong DYT, Wong JYH. Secular trends in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation needs in 191 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2144198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, Yin P, Zhu J, Chen W, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1145–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gebreyesus T, Nigussie K, Gashaw M, Janakiraman B. The prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among adults in Ethiopia: a study protocol for extending a systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams A, Kamper SJ, Wiggers JH, O’Brien KM, Lee H, Wolfenden L, et al. Musculoskeletal conditions may increase the risk of chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang F, Di N, Guo WW, Ding WB, Jia N, Zhang H, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of work related musculoskeletal disorders among electronics manufacturing workers: a cross-sectional analytical study in China. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zohair HMA, Girish S, Hazari A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among United Arab Emirates schoolteachers: an examination of physical activity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Putsa B, Jalayondeja W, Mekhora K, Bhuanantanondh P, Jalayondeja C. Factors associated with reduced risk of musculoskeletal disorders among office workers: a cross-sectional study 2017 to 2020. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo Y, Su B, Zheng X. Trends and challenges for Population and Health during Population Aging - China, 2015–2050. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(28):593–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niederstrasser NG, Attridge N. Associations between pain and physical activity among older adults. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0263356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatakis E, Straker L, Hamer M, Gebel K. The 2018 physical activity guidelines for americans: what’s new? Implications for clinicians and the public. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy. 2019;49(7):487–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Services USDHH. 2008 physical activity guidelines for americans. Volume 2008. Hyattsville, MD: Author, Washington, DC.; 2008. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrow JR Jr., Defina LF, Leonard D, Trudelle-Jackson E, Custodio MA. Meeting physical activity guidelines and musculoskeletal injury: the WIN study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(10):1986–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Strauss J, Yang G, Giles J, Hu P, Hu Y et al. China health and retirement longitudinal study–2011–2012 national baseline users’ guide. Beijing: National School of Development, Peking University. 2013;2:1–56.

- 19.Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW, et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:l4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macfarlane DJ, Lee CC, Ho EY, Chan KL, Chan DT. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7 days). J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng Z, Bian Y, Cui Y, Yang D, Wang Y, Yu C. Physical activity dimensions and its association with risk of diabetes in Middle and older aged Chinese people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai A, Tao L, Huang J, Tao J, Liu J. Effects of physical activity on cognitive function among patients with diabetes in China: a nationally longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu AH, Ng SH, Koh D, Müller-Riemenschneider F. Reliability and validity of the self-and interviewer-administered versions of the global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ). PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0136944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Sayer AA, Sarcopenia. Lancet. 2019;393(10191):2636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petermann-Rocha F, Balntzi V, Gray SR, Lara J, Ho FK, Pell JP, et al. Global prevalence of Sarcopenia and severe Sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(1):86–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–7. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Men P, Xiao Y, Gao P, Lv M, Yuan Q, et al. Hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strain T, Wijndaele K, Dempsey PC, Sharp SJ, Pearce M, Jeon J, et al. Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nat Med. 2020;26(9):1385–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmid D, Ricci C, Baumeister SE, Leitzmann MF. Replacing sedentary time with physical activity in relation to Mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(7):1312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chastin SFM, De Craemer M, De Cocker K, Powell L, Van Cauwenberg J, Dall P, et al. How does light-intensity physical activity associate with adult cardiometabolic health and mortality? Systematic review with meta-analysis of experimental and observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(6):370–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim W, Jin YS, Lee CS, Hwang CJ, Lee SY, Chung SG, et al. Relationship between the type and amount of physical activity and low back pain in koreans aged 50 years and older. PM R. 2014;6(10):893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alzahrani H, Mackey M, Stamatakis E, Zadro JR, Shirley D. The association between physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JH, Yun I, Nam CM, Jang SY, Park EC. Association between physical activity and health-related quality of life in middle-aged and elderly individuals with musculoskeletal disorders: findings from a national cross-sectional study in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(11):e0294602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherrington C, Fairhall NJ, Wallbank GK, Tiedemann A, Michaleff ZA, Howard K et al. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2019;(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, Thevenot O, Fransen M, Wells GA, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):596–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H. Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology. 2016;17:567–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams M, Gordt-Oesterwind K, Bongartz M, Zimmermann S, Seide S, Braun V, et al. Effects of Physical Activity interventions on Strength, Balance and Falls in Middle-aged adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med Open. 2023;9(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrow DR, Abbate LM, Paquette MR, Driban JB, Vincent HK, Newman C, et al. Exercise prescription for weight management in obese adults at risk for osteoarthritis: synthesis from a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez-Lastra MA, Ding D, Del Pozo Cruz B, Dalene KE, Ayan C, Ekelund U, et al. Joint associations of device-measured physical activity and abdominal obesity with incident cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2024;58(4):196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical activity, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Marriott CFS, Petrella AFM, Marriott ECS, Boa Sorte Silva NC, Petrella RJ. High-intensity interval training in older adults: a scoping review. Sports Med Open. 2021;7(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atakan MM, Li Y, Kosar SN, Turnagol HH, Yan X. Evidence-based effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity and Health: a review with historical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Juopperi S, Sund R, Rikkonen T, Kröger H, Sirola J. Cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health disorders associate with greater decreases in physical capability in older women. BMC Med. 2021;22:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heneweer H, Vanhees L, Picavet HS. Physical activity and low back pain: a U-shaped relation? Pain. 2009;143(1–2):21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagen KB, Dagfinrud H, Moe RH, Østerås N, Kjeken I, Grotle M, et al. Exercise therapy for bone and muscle health: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2012;10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weyh C, Pilat C, Krüger K. Musculoskeletal disorders and level of physical activity in welders. Occup Med. 2020;70(8):586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atakan MM, Li Y, Kosar SN, Turnagol HH, Yan X. Evidence-based effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity and Health: a review with historical perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13):7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rhim HC, Tenforde A, Mohr L, Hollander K, Vogt L, Groneberg DA, et al. Association between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain: an analysis of international data from the ASAP survey. BMJ open. 2022;12(9):e059525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alzahrani H, Shirley D, Cheng SWM, Mackey M, Stamatakis E. Physical activity and chronic back conditions: a population-based pooled study of 60,134 adults. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(4):386–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Molen HF, Visser S, Alfonso JH, Curti S, Mattioli S, Rempel D, et al. Diagnostic criteria for musculoskeletal disorders for use in occupational healthcare or research: a scoping review of consensus- and synthesised-based case definitions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J Public Health. 2006;14(2):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomioka K, Iwamoto J, Saeki K, Okamoto N. Reliability and validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in elderly adults: the Fujiwara-Kyo Study. J Epidemiol. 2011;21(6):459–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):755–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sember V, Meh K, Soric M, Starc G, Rocha P, Jurak G. Validity and reliability of International Physical Activity questionnaires for adults across EU countries: systematic review and Meta Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alentorn-Geli E, Samuelsson K, Musahl V, Green CL, Bhandari M, Karlsson J. The Association of Recreational and competitive running with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(6):373–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study used data from the 2015 wave of the CHARLS. The dataset is publicly available through the CHARLS project website (https://charls.charlsdata.com/pages/Data/2015-charls-wave4/zh-cn.html).