Abstract

Background

Eliminating hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections is a goal set by the World Health Organization. This has become possible with the introduction of highly effective and safe direct-acting antivirals (DAA) but limitations remain due to undiagnosed HCV infections and loss of patients from the cascade of care at various stages, including those lost to follow-up (LTFU) before the assessment of the effectiveness of the therapy. The aim of our study was to determine the extent of this loss and to establish the characteristics of patients experiencing it.

Methods

Patients with chronic HCV infection from the Polish retrospective multicenter EpiTer-2 database who were treated with DAA therapies between 2015 and 2023 were included in the study.

Results

In the study population of 18,968 patients, 106 had died by the end of the 12-week post-treatment follow-up period, and 509 patients did not report for evaluation of therapy effectiveness while alive and were considered LTFU. Among patients with available assessment of sustained virological response (SVR), the effectiveness of therapy was 97.5%. A significantly higher percentage of men (p<0.0001) and a lower median age (p=0.0001) were documented in LTFU compared to the group with available SVR assessment. In LTFU patients, comorbidities such as alcohol (p<0.0001) and drug addiction (p=0.0005), depression (p=0.0449) or other mental disorders (p<0.0001), and co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (p<0.0001) were significantly more common as compared to those with SVR assessment. They were also significantly more often infected with genotype (GT) 3, less likely to be treatment-experienced and more likely to discontinue DAA therapy.

Conclusions

In a real-world population of nearly 19,000 HCV-infected patients, we documented a 2.7% loss to follow-up rate. Independent predictors of this phenomenon were male gender, GT3 infection, HIV co-infection, alcohol addiction, mental illnesses, lack of prior antiviral treatment and discontinuation of DAA therapy.

Keywords: HCV, Lost to follow-up, Treatment, Direct-acting antivirals

Background

The availability for a decade of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs with very high efficacy of more than 95% has theoretically made it possible to eliminate infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat [1]. However, it is already clear that this goal set by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be reached in 2030 will not be achieved by many, even high-income, countries [2]. One of the reasons for this is the lack of universal HCV screening programs, with the result that only one-third of the estimated 50 million infected patients worldwide are aware of the disease [3]. A significant barrier to HCV elimination is also the loss of patients from the care cascade, which, along with factors such as treatment availability, results in only 20% of patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) globally receiving antiviral treatment, with significant regional variation ranging from 3% in the African region to 35% in the Eastern Mediterranean region [4].

This pathway to HCV elimination is hindered especially by those who are lost from the cascade of care before obtaining antiviral treatment [5]. However, we cannot neglect the impact of the loss to follow-up of patients who received therapy and did not present to evaluate its effectiveness [6]. The frequency of this event ranges from less than 1 to 25% depending on the population characteristics, being higher in real-world studies compared to clinical trials with a strategy of retaining patients in follow-up until the last scheduled visit [7]. Moreover, even with a very high HCV eradication rate with currently used DAA drugs, there remains a margin of a few percent ineffectiveness related to the presence of negative predictors of virological response [8]. At the scale of the many millions of CHC patients undergoing antiviral therapy, even these small values adding up can translate into relatively large absolute numbers and represent a real barrier to HCV elimination. Additionally, if a patient lost to follow-up comes from a population presenting high-risk behavior for HCV transmission, the failure to cure, especially unknowingly, may constitute an epidemiological problem. It can be assumed that a patient who does not show up to assess the effectiveness of the therapy is more likely to be non-adherent during treatment. This, in turn, may translate into lower-than-expected effectiveness [9].

Last but not least, the loss of follow-up of a patient with advanced liver disease means a lack of continuity of long-term care and surveillance of possible disease progression and the development of serious, life-threatening complications, such as decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which may occur even after HCV eradication [10, 11].

Therefore, to properly address this issue and limit its impact on the WHO goal achievement, it is important to recognize the patient profile with the likelihood of loss to follow-up after treatment. This knowledge may contribute to the development of effective methods of keeping the patient in care.

To this end, we conducted this analysis in a real-world population (RWE) of patients treated with DAA for HCV infection,which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest population analyzed in this respect. It aimed to determine the scale of the phenomenon of losing patients to follow-up after antiviral treatment and to develop the characteristics of such individuals.

Methods

Patients with chronic HCV infection whose data were collected in the EpiTer-2 database were included in the study. This real-world ongoing Polish multicenter observational project evaluating antiviral treatment since mid-2015, the beginning of the availability of DAA regimens, enrolled 19,020 patients, including 18,968 adults aged 18 years and older from 24 leading hepatology centers, by the end of 2023. EpiTer-2 study is supported by the Polish Society of Epidemiologists and Infectious Diseases. Patients’ data were entered retrospectively into an online questionnaire administered by TIBA based on medical records.

The choice of therapeutic option was made by the attending physician. The selection of the regimen, qualification for treatment, and its monitoring were carried out following the recommendations of the Polish Expert Group for HCV and the rules of drug reimbursement under the drug program of the National Health Fund [12–14]. Informed consent for treatment and processing of personal data was obtained from patients under drug program requirements and national regulations.

Patient data collected in the database included demographic information such as gender, age, body mass index (BMI), and clinical information relating to comorbidities, co-infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and comedications taken. Laboratory results recorded in the database included aminotransferase activity, international normalized ratio, complete blood count, bilirubin, albumin, and creatinine levels.

Data characterizing the severity of liver disease included the assessment of hepatic stiffness using non-invasive elastography with Fibroscan or Aixplorer with correlating METAVIR fibrosis values [15]. Patients diagnosed with a fibrosis (F) 4 value were evaluated for the presence of esophageal varices, and decompensation of liver function in the past and at baseline of antiviral treatment. Data were also collected on the diagnosis of HCC and past liver transplantation.

Information relating to HCV infection reported in the database included genotype and viral load, history of prior therapy, and type of current DAA regimen. Viraemia HCV (ribonucleic acid, RNA) was assessed at baseline, at the end of therapy, and after treatment by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction with a lower limit of detection not higher than 15 IU/mL following national recommendations [12–14].

Patients were treated with genotype-specific or pangenotypic DAA options. Genotype-specific regimens include following combinations: asunaprevir (ASV) + daclatasvir (DCV), ledipasvir (LDV) and sofosbuvir (SOF) ± ribavirin (RBV), ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir+dasabuvir (OBV/PTV/r+DSV) ±RBV, grazoprevir (GZR) and elbasvir (EBR) ±RBV, and SOF with simeprevir (SMV) used with or without RBV. The pangenotypic options comprised the combination of SOF and RBV, SOF with DCV ±RBV, SOF and velpatasvir (VEL), SOF/VEL with voxilaprevir (VOX), glecaprevir (GLE) and pibrentasvir (PIB), and GLE/PIB plus SOF and RBV.

The measure of treatment effectiveness was sustained virologic response (SVR), defined as undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after completion of therapy. Patients with a detectable viral load at this time point were considered virologic nonresponders, while those without this assessment were defined as lost to follow-up (LTFU). Data regarding the status of the patient—living or deceased—who did not attend the SVR appointment was checked in the system of insured persons. For the purpose of this analysis, the patients were divided into two groups: with SVR assessment and without SVR assessment, after excluding cases of deaths.

During therapy and up to 12 weeks after its completion, data were collected on the course of treatment, the incidence of adverse events (AEs) with an assessment of their severity, and deaths.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were analyzed by determining their numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups for these variables were made using either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. For quantitative variables, the analysis involved calculating the median, and interquartile ranges. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of the distribution. Due to the non-normal distribution of quantitative variables, comparisons between the two groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. To examine the independent effects of several variables on a dichotomous outcome, multivariate analysis was conducted using multiple logistic regression. The results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were carried out using Statistica version 13 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 5.1 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

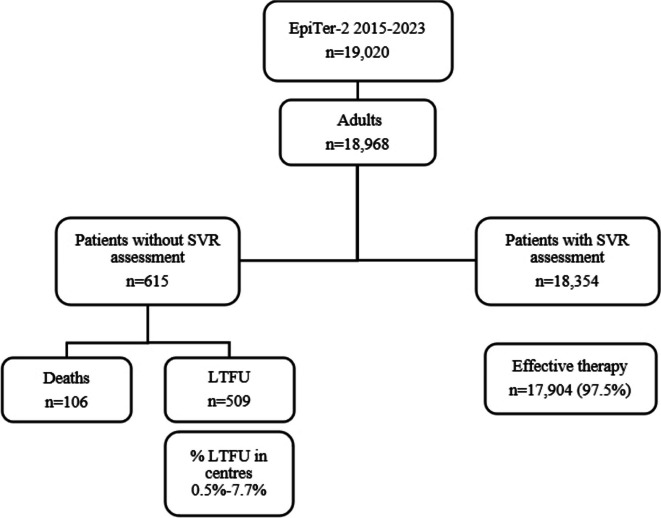

In the studied population, 18,354 patients had an available therapeutic response assessment with an SVR rate of 97.5%. Of the remaining 615 patients, 106 died during the 12-week post-treatment follow-up period, and 509 patients did not report for therapy effectiveness evaluation while alive and they were considered LTFU. Overall, they accounted for 2.7%, but the proportion varied from center to center, ranging from 0.5 to 7.7% of the total number of patients treated at each site (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study population. Abbreviations: LTFU, loss to follow-up; SVR, sustained virological response

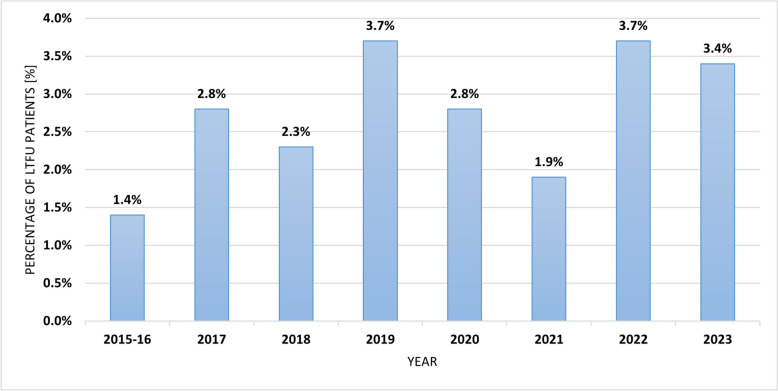

The proportion of LTFU patients also varied between the years of the study (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The percentage of LTFU in the periods of the EpiTer-2 project. Abbreviations: LTFU, loss to follow-up

In this subpopulation, a significantly higher percentage of men (61.9% vs. 49.8%, p<0.0001) and a significantly lower median age of patients (46 vs. 51 years, p=0.0001) as compared to those with SVR assessment were documented (Table 1). The prevalence of comorbidities was lower among LTFUs, and the difference was insignificant but depression (p=0.0449), alcohol addiction (p<0.0001), drug addiction (p=0.0005) and other psychiatric disorders (p<0.0001) were significantly more common in this group as compared to patients with SVR assessment (Table 1). HIV co-infection was found almost three times more often in the LTFU group, 15.5% vs. 5.7%, p<0.0001. Among drug addicts, about a quarter in both subpopulations were co-infected with HIV, 26.6% in LTFU, and 23.1% among those with SVR assessment. There were no differences between subpopulations in the proportion of patients using concomitant drugs, including methadone substitution therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of LTFU and patients with SVR assessment

| Parameter | LTFU, n=509 | Patients with SVR assessment, n=18,354 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, females/males, n (%) | 194 (38.1) / 315 (61.9) | 9220 (50.2) / 9134 (49.8) | <0.0001 |

| Age [years], median (IQR) | 46 (38–59) | 51 (39–62) | 0.0001 |

| BMI [kg/m2], median (IQR) | 25.6 (22.7–28.2) | 25.8 (23.1–28.7) | 0.16 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Any comorbidity | 288 (56.6) | 11203 (61) | 0.42 |

| Hypertension | 129 (25.3) | 5897 (32.1) | 0.026 |

| Diabetes | 53 (10.4) | 2130 (11.6) | >0.99 |

| Renal disease | 15 (2.9) | 836 (4.6) | >0.99 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 5 (1) | 376 (2) | >0.99 |

| Non-HCC tumors | 14 (2.8) | 375 (2) | 0.65 |

| Depression | 32 (6.3) | 701 (3.8) | 0.0449 |

| Alcohol addiction | 34 (6.7) | 317 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Drug addiction | 15 (2.9) | 193 (1.1) | 0.0005 |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 19 (3.7) | 232 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Concomitant medications, n (%) | 302 (59.3) | 10924 (59.5) | 0.76 |

| Methadone, n (%) | 6 (1.2) | 113 (0.6) | 0.226 |

| HBV coinfection (HBsAg+), n (%) | 9 (1.8) | 180 (1) | 0.58 |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | 79 (15.5) | 1053 (5.7) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: BMI body mass index, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, IQR interquartile range, HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen, HBV hepatitis B virus, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, LTFU loss to follow-up, SVR sustained virological response

Significant differences in the distribution of HCV genotypes were documented, with lower rates of genotype (GT1) b (56.8% vs. 74.2%) and higher GT3 infections (26.1% vs. 12.0%) in the LTFU subpopulation compared to patients with SVR assessment, p<0.0001, also significantly lower baseline HCV viral loads in LTFU was noted, p=0.009 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of HCV infection, liver disease, and laboratory parameters in LTFU and patients with SVR assessment

| Parameter | LTFU, n=509 | Patients with SVR assessment, n=18,354 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| 1 | 6 (1.2) | 370 (2.0) | |

| 1a | 28 (5.5) | 830 (4.5) | |

| 1b | 289 (56.8) | 13,616 (74.2) | |

| 2 | 4 (0.8) | 49 (0.3) | |

| 3 | 133 (26.1) | 2203 (12.0) | |

| 4 | 34 (6.7) | 880 (4.8) | |

| 5 | 0 | 1 (<0.1) | |

| 6 | 0 | 6 (<0.1) | |

| No data | 15 (2.9) | 399 (2.2) | |

| GT3 / non-GT3, n (%) | 133 (26.1) / 361 (70.9) | 2203 (12.0) / 16,149 (88) | <0.0001 |

| Liver fibrosis n (%) | |||

| F0 | 11 (2.2) | 512 (2.8) | 0.44 |

| F1 | 181 (35.6) | 7195 (39.2) | |

| F2 | 107 (21) | 3430 (18.7) | |

| F3 | 70 (13.7) | 2477 (13.5) | |

| F4 | 120 (23.6) | 4433 (24.2) | |

| No data | 20 (3.9) | 307 (1.7) | |

| F0-3 / F4, n (%) | 369 (72.5) / 120 (23.6) | 13614 (74.2) / 4433 (24.2) | 0.99 |

| History of liver decompensation, n (%) | |||

| Ascites | 17 (3.3) | 483 (2.6) | 0.172 |

| Encephalopathy | 1 (0.2) | 130 (0.7) | 0.542 |

| Documented esophageal varices, n (%) | 34 (6.7) | 1259 (6.9) | 0.92 |

| Liver decompensation at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Ascites | 12 (2.4) | 263 (1.4) | 0.17 |

| Encephalopathy | 2 (0.4) | 102 (0.6) | >0.99 |

| HCC history, n (%) | 12 (2.4) | 260 (1.4) | 0.077 |

| OLTx history, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 143 (0.8) | 0.19 |

| ALT IU/L, median (IQR) | 62 (39–101.8) | 60 (37.5–100) | 0.48 |

| Bilirubin mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.7 (0.5–1) | 0.64 (0.5–0.9) | 0.64 |

| Albumin g/dL, median (IQR) | 4.1 (3.8–4.5) | 4.13 (3.8–4.4) | 0.54 |

| Creatinine mg/dL, median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.09 |

| Hemoglobin g/dL, median (IQR) | 14.3 (13.1–15.5) | 14.5 (13.4–15.5) | 0.0526 |

| Platelets, ×1000/µL, median (IQR) | 194 (138–240) | 197 (146–245) | 0.27 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1 (1–1.1) | 1 (1–1.1) | 0.27 |

| HCV RNA ×105 IU/ml, median (IQR) | 7.97 (2.56–24) | 9.93 (3.21–26.1) | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: ALT alanine transaminase, GT genotype, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV hepatitis C virus, INR international normalized ratio, IQR interquartile range, F fibrosis stage, OLTx orthotopic liver transplantation, LTFU loss to follow-up, SVR sustained virological response

No significant differences in the severity of liver disease were documented between the two subpopulations.

The majority of patients in both groups were treatment-naive, but the percentage was significantly higher among LTFU (85.5% vs. 80.7%, p=0.007) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment characteristics of the population of LTFU and patients with SVR assessment

| Parameter | LTFU, n=509 | Patients with SVR assessment, n=18,354 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment-naïve, n (%) | 435 (85.5) | 14,807 (80.7) | 0.007 |

| Genotype-specific treatment regimens, n (%) | 167 (32.8) | 9646 (52.6) | <0.0001 |

| ASV+DCV | 3 (0.6) | 132 (0.7) | >0.99 |

| OBV/PTV/r+DSV±RBV | 49 (9.6) | 3998 (21.8) | <0.0001 |

| LDV/SOF±RBV | 61 (12) | 2981 (16.2) | 0.0099 |

| GZR/EBR±RBV | 54 (10.6) | 2536 (13.8) | 0.0380 |

| SOF±SMV±RBV | 0 | 10 (0.1) | >0.99 |

| Pangenotypic regimens, n (%) | 342 (67.2) | 8708 (47.4) | <0.0001 |

| SOF+RBV | 30 (5.9) | 311 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| SOF+DCV±RBV | 3 (0.6) | 43 (0.2) | 0.13 |

| GLE/PIB | 140 (27.5) | 4777 (26.0) | 0.45 |

| GLE/PIB+SOF+RBV | 0 | 7 (<0.1) | >0.99 |

| SOF/VEL±RBV | 164 (32.2) | 3476 (18.9) | <0.0001 |

| SOF/VEL/VOX | 5 (1.0) | 83 (0.5) | 0.09 |

| RBV-containing regimens, n (%) | 64 (12.6) | 2579 (14.1) | 0.343 |

Abbreviations: ASV asunaprevir, DCV daclatasvir, DSV dasabuvir, EBR elbasvir, GLE glecaprevir, GT genotype, GZR grazoprevir, LDV ledipasvir, LTFU loss to follow-up, OBV ombitasvir, PIB pibrentasvir, PTV/r paritaprevir boosted with ritonavir, RBV ribavirin, SMV simeprevir, SOF sofosbuvir, SVR sustained virological response, VEL velpatasvir, VOX voxilaprevir

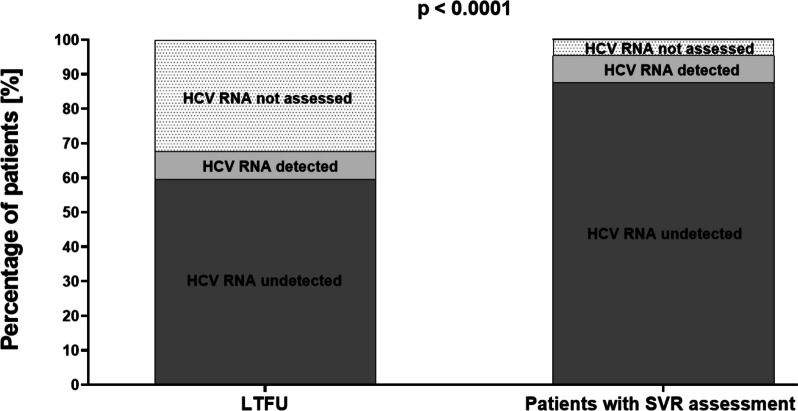

These patients were significantly more often treated with pangenotypic regimens (67.2% vs. 47.4%, p<0.0001), particularly SOF+RBV (p<0.0001) and SOF/VEL±RBV (p<0.0001), while patients with SVR assessment were significantly more likely to receive genotype-specific options (52.6% vs. 32.8%, p<0.0001). Virological response at the end of therapy measured by undetectable HCV RNA at this time point was achieved in 87.6% of patients in patients with SVR assessment and 59.5% in the LTFU group, p<0.0001 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

End-of-treatment response in a population of LTFU and patients with SVR assessment. Abbreviations: HCV, hepatitis C virus; LTFU, loss to follow-up; SVR, sustained virological response

The majority of patients completed therapy as planned but the percentage of patients who discontinued therapy was significantly more common among LTFU (11% vs. 1.2%, p<0.0001), (Table 4). The proportion of patients who experienced at least one adverse event was comparable across the groups, but the LTFU patients had a significantly higher rate of serious AEs compared to the population with SVR assessment, 2.9% vs. 0.8%, p<0.0001. However, considering AE as a cause among patients who discontinued treatment, there was no difference between subpopulations.

Table 4.

Comparison of safety in LTFU and patients with SVR assessment

| Parameter | LTFU, n=509 | Patients with SVR assessment, n=18,354 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy course, n (%) | |||

| According to schedule | 432 (84.9) | 18,002 (98.1) | <0.0001 |

| Discontinuation | 56 (11) | 227 (1.2) | |

| Modification | 6 (1.2) | 105 (0.6) | |

| No data | 15 (2.9) | 20 (0.1) | |

| Patients with at least one AE, n (%) | 86 (16.9) | 3085 (16.8) | 0.95 |

| Treatment discontinuation due to AE in relation to all cases of discontinuation, n/n (%) | 19/56 (33.9) | 76/227 (33.4) | 0.949 |

| Serious adverse events, n (%) | 15 (2.9) | 144 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: AE adverse event, LTFU loss to follow-up, SVR sustained virological response

Logistic regression analysis showed that loss to follow-up phenomenon was independently associated with male gender (OR 1.362), GT3 infection (OR 2.103), HIV coinfection (OR 2.476), depression (OR 1.655), alcohol addiction (OR 3.153) and other psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, psychotic disorders, dissociative disorders, personality disorders) (OR 2.591) (Table 5). There was no association with age, the history of previous therapy, drug addiction, and the occurrence of severe AEs.

Table 5.

Factors associated with loss to follow-up in multivariate analysis

| Effect | Effect measure | Wald stat | OR | 95% Cl | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 983.944 | 0.011 | 0.008–0.014 | <0.0001 | |

| Age | ≤ 40 years | 3.739 | 1.216 | 0.997–1.483 | 0.0532 |

| Gender | Male | 9.530 | 1.362 | 1.119–1.657 | 0.0020 |

| GT3 infection | Yes | 43.203 | 2.103 | 1.685–2.625 | <0.0001 |

| History of previous therapy | Naive | 4.440 | 1.334 | 1.020–1.744 | 0.0351 |

| HIV-coinfection | Yes | 43.847 | 2.476 | 1.893–3.238 | <0.0001 |

| Depression | Yes | 6.488 | 1.655 | 1.123–2.438 | 0.0109 |

| Drug addiction | Yes | 0.676 | 1.273 | 0.716–2.260 | 0.4110 |

| Alcohol addiction | Yes | 31.652 | 3.153 | 2.114–4.705 | <0.0001 |

| Other psychiatric disordersa | Yes | 13.709 | 2.591 | 1.565–4.289 | 0.0002 |

| Therapy course | Discontinuation | 274.068 | 22.563 | 15.601–32.631 | <0.0001 |

| Serious AEs | Yes | 3.265 | 1.818 | 0.951–3.477 | <0.071 |

Abbreviations: AE adverse event, CI Confidence interval, GT genotype, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, OR Odds ratio, LTFU loss to follow-up, SVR sustained virological response

aSchizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, psychotic disorders, dissociative disorders, personality disorders

Discussion

In a very large HCV-infected population from daily clinical practice of about 19,000 people, we documented a 2.7% rate of patients lost to follow-up after DAA treatment. Despite some year-to-year fluctuations in its frequency due to changes in patient profiles, it ranged from 1.4–3.7% and was relatively low compared to other RWE analyses, most of which reports percentages of 4 to 15%, and the study from Japan even 25% [16–19]. The size of the cohorts analyzed in the aforementioned studies is small, ranging from 138 to 296 patients, while in studies with larger populations, such as the Australian REACH-C (n=3295) and German Hepatitis-C Registry (n=7747), the reported percentage of LTFU was 16 and 9.3%, respectively [20, 21]. In the largest population analyzed so far in this regard consisted of U.S. veterans, a 9% loss to follow-up rate was reported, but it is worth noting that it included 17,487 patients and was also smaller than the group we studied [22]. Not only do the sizes and various characteristics of the study populations seem to be responsible for these differences, but also the patient retention strategies used, including active calling via telephone and email contact [5]. It should be noted that our study also demonstrated differences between centers ranging from 0.5 to 7.7%.

A relatively large proportion of LTFU in our study had no HCV RNA evaluation at the end of therapy. It should be noted that from mid-2023, this test is not mandatory in the Polish reimbursed drug program, because even a positive result does not predict the ineffectiveness of DAA therapy, and the decision is up to the attending physician [23]. However, a comparison with patients with an available SVR assessment (32.7% vs. 4.7%) leads us to believe that the frequent reason was the patient’s failure to present at this time point. This, in turn, raises concerns about adherence during therapy despite patient declarations.

In our analysis, male gender appeared to be an independent predictor of loss to follow-up (OR 1.362, p=0.002), and these results are consistent with the findings of Italian researchers and observations from the German Hepatitis-C Registry [17, 20]. Results from studies originating in Australia are divergent, with analysis from the REACH-C study finding no association with gender whereas the OPERA-C study identified male gender as an independent predictor of the loss to follow-up [24, 25] Another demographic parameter that some studies claim increases the likelihood of LTFU is younger age, but our analysis did not show the significance of age as an independent factor for loss to follow-up, although in univariate analysis the LTFU patients were significantly younger compared to patients with SVR assessment [17, 24, 25].

We also documented a difference between subpopulations in terms of history of previous antiviral therapy, LTFU patients were more likely to be untreated (p = 0.007) and this factor appeared to be independent in multivariate analysis (OR 1.334, p=0.0351). This observation supported the results of the multicenter prospective OPERA-C study from Australia and retrospective analysis from the German Hepatitis-C Registry [20, 25]. A likely explanation is the greater involvement of patients after unsuccessful treatment in re-therapy, as also highlighted by Australian researchers. In turn, treatment discontinuation, regardless of the reason, was an independent risk factor for loss to follow-up in our study. It is difficult for us to comment on other analyses, as to our knowledge the impact of this parameter has not been studied to date. We can assume that patients who made their own decision to discontinue treatment thereby decided not to pursue further care whereas those in whom treatment was discontinued due to adverse events were lost to follow-up due to disillusionment with the therapy process.

Among virus-related characteristics, we documented an impact of GT3 infection increasing independently the probability of loss to follow-up (OR 2.103, p<0.0001), and these results support data from other RWE studies [20, 26]. It is reasonable to believe that the significantly higher proportion of GT3-infected patients in the LTFU population compared to SVR-assessed patients (26% vs. 12%, p<0.0001) is responsible for the differences in our study in the use of DAA regimens with significantly higher rates of treatment with pangenotypic options.

A factor that has been documented in a number of analyses to affect the loss of a patient from follow-up after treatment is drug addiction, both in the past and ongoing [18, 20, 25–27]. In our study, we documented significantly more frequent drug addiction in the LTFU population compared to patients with SVR assessment (p=0.0005), but we did not confirm the significance of this factor in multivariate analysis (OR 1.273, p=0.411). The population of drug addicts is special in terms of achieving elimination of HCV infection. The opioid epidemic sweeping through many countries in recent years is contributing to an increase in the number of infected, especially at a young age [28]. This increase is observed also in young women of childbearing age and is of particular concern because it translates into a risk of transmission to the child [29]. In this specific population of drug users, developing effective methods to keep the patient under observation, not only for SVR assessment but also for long-term monitoring due to the risk of reinfection resulting from possible continuation of risky behavior [30, 31].

The probability of HCV reinfection associated with risky practices also applies to HIV-positive patients, and it should be noted that there is significant overlap in the populations of these patients, which is true in our analysis as well [32, 33]. Therefore, it is extremely important to supervise this group of patients after antiviral treatment, especially since, according to some reports, HIV co-infection increases the risk of HCV-induced liver disease progression [34]. Our study showed that people living with HIV were significantly more likely to be lost to follow-up (OR 2.476, p<0.0001), while the results obtained by other researchers are divergent. Some reports are consistent with our results, while others do not identify HIV co-infection as a predisposing factor for loss to follow-up [21, 33, 35, 36].

Data from an analysis of U.S. veterans and patients from the German Hepatitis-C Registry, very large RWE cohorts, document a higher rate of LTFU in alcohol-dependent individuals [22, 37]. Our study confirmed these observations by showing alcohol dependence as an independent predictor of loss to follow-up (OR 3.153, p<0.0001).

Another group of comorbidities that negatively affected the presentation of patients for SVR evaluation in our analysis were mental illnesses, depression (OR 1.655, p=0.0109), and other disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, personality and dissociative disorders (OR 2.592, p=0.0002). Similar observations were obtained by Danish researchers in the nationwide HCV retrieval project, CELINE but it should be noted that this study focused on a population that was lost to follow-up before receiving DAA treatment [6]. Therefore, mental illnesses, a contraindication to interferon treatment, have no longer been a barrier to receiving treatment in the era of safe DAA regimens, but they still appear to be a barrier to retention in the cascade of care. It is reasonable to assume that patients with mental illnesses lost from follow-up after treatment for HCV are still under specialized care because of their underlying disease, and the situation is similar for HIV-infected patients. However, due to the fact that this usually takes place in different healthcare facilities, there is a lack of information flow, allowing for continuity of care due to HCV infection.

We did not extend data collection to medical records from other sources, such as psychiatric or HIV treatment centers, to obtain data from there after DAA therapy, and this is one of the limitations of our analysis. Other limitations that we are aware of are due to the retrospective method of data collection with possible bias and underestimation of information on alcohol and drug dependence. In addition, we did not distinguish between former and current alcohol and drug users in the analysis. Data on patient retention strategies that could explain differences between centers were not collected. We did not analyze the impact of socioeconomic conditions, which some researchers identify as important for losing a patient to follow-up [6]. Finally, adherence to therapy was not measured objectively but was based on patient declarations. However, a main strength of our study is the inclusion of a diverse RWE population of from many centers in the country, treated and monitored under the same guidelines, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest population analyzed in this respect so far. This allowed for conclusions that can be generalized.

Conclusions

In the largest to date population of HCV-infected patients evaluated for the phenomenon of loss to follow-up after DAA treatment in a routine clinical practice, we documented its occurrence with a low frequency of 2.7%. Independent factors increasing the probability of loss to follow-up were male gender, GT3 HCV infection, HIV co-infection, alcohol addiction, mental illnesses, no prior antiviral treatment, and therapy discontinuation. Creating a strategy to retain patients with these characteristics in the care cascade may significantly contribute to achieving the WHO goal of eliminating HCV as a public health threat.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Polish Association of Epidemiologists and Infectiologists for the creation and maintenance of the database.

Abbreviations

- AEs

Adverse events

- ASV

Asunaprevir

- BMI

Body mass index

- CHC

Chronic hepatitis C

- Cl

Confidence interval

- DAA

Direct-acting antiviral

- DCV

Daclatasvir

- DSV

Dasabuvir

- EBR

Elbasvir

- F

Fibrosis

- GLE

Glecaprevir

- GT

Genotype

- GZR

Grazoprevir

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B virus surface antigen

- HBV

Hepatitis B

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- INR

International normalized ratio

- LDV

Ledipasvir

- LTFU

Lost to follow-up

- OBV

Ombitasvir

- OLTx

Orthotopic liver transplantation

- OR

Odds ratios

- PIB

Pibrentasvir

- PTV

Paritaprevir

- PTV/r

Ritonavir-boosted paritaprevir

- RBV

Ribavirin

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- RWE

Real-world evidence

- SMV

Simeprevir

- SOF

Sofosbuvir

- SVR

Sustained virological response

- VEL

Velpatasvir

- VOX

Voxilaprevir

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z.M., M.B., R.F.; methodology, D.Z-M., M.B., R.F.; software, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B., investigation, M.B.; data curation, D.Z-M., O.T., J.J-L., M.S., A.P., J.K., A.P-K., B. S.-S., M.T-Z, Ł.L., R.F.; writing-original draft preparation M.B., D.Z-M., R.F.; writing-review and editing D.Z-M., M.B., O.T., J.J-L., M.S., A.P., J.K., A.P-K., B. S.-S., M.T-Z, Ł.L., R.F. visualization, M.B.; supervision, D.Z-M., R.F.; project administration, D.Z-M., R.F.; funding acquisition, R.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All Authors Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted after the approval of the Bioethics Committee of the Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce by resolution No. 57/2024 of 25.07.2024 r.

Patients provided consent to participate in the therapeutic program according to regulations of National Health Fund.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Zarębska-Michaluk D has acted as a speaker for AbbVie and Gilead, Brzdęk M has no conflict of interest to declare. Tronina O has no conflict of interest to declare. Janocha-Litwin J has no conflict of interest to declare. Sitko M has acted as a speaker for Gilead and AbbVie. Piekarska A has acted as a speaker and/or advisor for AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and Roche. Klapaczyński J has acted as a speaker for Gilead and AbbVie. Parfieniuk-Kowerda A has no conflict of interest to declare. Barbara Sobala-Szczygieł has been a speaker for AbbVie and Gilead. Tudrujek-Zdunek M has no conflict of interest to declare. Lorenc B has no conflict of interest to declare. Flisiak R has acted as a speaker and/or advisor, and has received funding for clinical research from AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and Roche.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zarębska-Michaluk Dorota and Brzdęk Michał contributed equally to this work.

Change history

11/8/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1186/s12916-024-03753-w

References

- 1.Brzdęk M, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Invernizzi F, Cilla M, Dobrowolska K, Flisiak R. Decade of optimizing therapy with direct-acting antiviral drugs and the changing profile of patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:949–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razavi H, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Yuen C, Cornberg M. Global timing of hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries. Liver Int. 2020;40:522–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hepatitis C. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c. Accessed 26 Aug 2024.

- 4.World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization; 2024. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376461/9789240091672-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- 5.Ferraz MLG, de Andrade ARCF, Pereira GHS, Codes L, Bittencourt PL. Retrieval of HCV patients lost to follow-up as a strategy for Hepatitis C Microelimination: results of a Brazilian multicentre study. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dijk M, Boyd A, Brakenhoff SM, Isfordink CJ, van Zoest RA, Verhagen MD, et al. Socio-economic factors associated with loss to follow-up among individuals with HCV: a Dutch nationwide cross-sectional study. Liver Int. 2024;44:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dijk M, Drenth JPH, HepNed study group. Loss to follow-up in the hepatitis C care cascade: a substantial problem but opportunity for micro-elimination. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:1270–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pabjan P, Brzdęk M, Chrapek M, Dziedzic K, Dobrowolska K, Paluch K, et al. Are there still difficult-to-treat patients with chronic hepatitis C in the era of direct-acting antivirals? Viruses. 2022;14:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark PJ, Valery PC, Strasser SI, Weltman M, Thompson AJ, Levy M, et al. Liver disease and poor adherence limit hepatitis C cure: a real-world Australian treatment cohort. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muzica CM, Stanciu C, Huiban L, Singeap A-M, Sfarti C, Zenovia S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma after direct-acting antiviral hepatitis C virus therapy: a debate near the end. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:6770–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flisiak R, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Janczewska E, Łapiński T, Rogalska M, Karpińska E, et al. Five-year follow-up of cured HCV patients under real-world interferon-free therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halota W, Flisiak R, Juszczyk J, Małkowski P, Pawłowska M, Simon K, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of hepatitis C in 2017. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2017;2:47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halota W, Flisiak R, Juszczyk J, Małkowski P, Pawłowska M, Simon K, et al. Recommendations of the Polish Group of Experts for HCV for the treatment of hepatitis C in 2020. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;6:163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomasiewicz K, Flisiak R, Jaroszewicz J, Małkowski P, Pawłowska M, Piekarska A, et al. Recommendations of the Polish Group of Experts for HCV for the treatment of hepatitis C in 2023. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;9:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferraioli G, Tinelli C, Dal Bello B, Zicchetti M, Filice G, Filice C, et al. Accuracy of real-time shear wave elastography for assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: a pilot study. Hepatology. 2012;56:2125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flisiak R, Zarębska-Michaluk D, Jaroszewicz J, Lorenc B, Klapaczyński J, Tudrujek-Zdunek M, et al. Changes in patient profile, treatment effectiveness, and safety during 4 years of access to interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020;130:163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scaglione V, Mazzitelli M, Costa C, Pisani V, Greco G, Serapide F, et al. Virological and clinical outcome of DAA containing regimens in a cohort of patients in Calabria region (Southern Italy). Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nouch S, Gallagher L, Erickson M, Elbaharia R, Zhang W, Wang L, et al. Factors associated with lost to follow-up after hepatitis C treatment delivered by primary care teams in an inner-city multi-site program, Vancouver. Canada Int J Drug Policy. 2018;59:76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuwano A, Yada M, Kurosaka K, Tanaka K, Masumoto A, Motomura K. Risk factors for loss to follow-up after the start of direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. JGH Open. 2023;7:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christensen S, Buggisch P, Mauss S, Böker KHW, Schott E, Klinker H, et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment of chronic HCV-infected patients on opioid substitution therapy: still a concern in clinical practice? Addiction. 2018;113:868–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark PJ, Valery PC, Ward J, Strasser SI, Weltman M, Thompson A, et al. Hepatitis C treatment outcomes for Australian First Nations Peoples: equivalent SVR rate but higher rates of loss to follow-up. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsui JI, Williams EC, Green PK, Berry K, Su F, Ioannou GN. Alcohol use and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes among patients receiving direct antiviral agents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarębska-Michaluk D, Flisiak R, Janczewska E, Berak H, Mazur W, Janocha-Litwin J, et al. Does a detectable HCV RNA at the end of DAA therapy herald treatment failure? Antiviral Res. 2023;220:105742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee J, Carson JM, Hajarizadeh B, Hanson J, O’Beirne J, Iser D, et al. High Effectiveness of broad access direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in an Australian real-world cohort: the REACH-C study. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:496–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark PJ, Valery PC, Strasser SI, Weltman M, Thompson A, Levy MT, et al. Broadening and strengthening the health providers caring for patients with chronic hepatitis C may improve continuity of care. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;39:568–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darvishian M, Wong S, Binka M, Yu A, Ramji A, Yoshida EM, et al. Loss to follow-up: a significant barrier in the treatment cascade with direct-acting therapies. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macías J, Morano LE, Téllez F, Granados R, Rivero-Juárez A, Palacios R, et al. Response to direct-acting antiviral therapy among ongoing drug users and people receiving opioid substitution therapy. J Hepatol. 2019;71:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateu-Gelabert P, Sabounchi NS, Guarino H, Ciervo C, Joseph K, Eckhardt BJ, et al. Hepatitis C virus risk among young people who inject drugs. Front Public Health. 2022;10:835836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kushner T, Reau N. Changing epidemiology, implications, and recommendations for hepatitis C in women of childbearing age and during pregnancy. J Hepatol. 2021;74:734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frankova S, Jandova Z, Jinochova G, Kreidlova M, Merta D, Sperl J. Therapy of chronic hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: focus on adherence. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heo M, Norton BL, Pericot-Valverde I, Mehta SH, Tsui JI, Taylor LE, et al. Optimal hepatitis C treatment adherence patterns and sustained virologic response among people who inject drugs: the HERO study. J Hepatol. 2024;80:702–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacks-Davis R, van Santen DK, Boyd A, Young J, Stewart A, Doyle JS, et al. Changes in incidence of hepatitis C virus reinfection and access to direct-acting antiviral therapies in people with HIV from six countries, 2010–19: an analysis of data from a consortium of prospective cohort studies. Lancet HIV. 2024;11:e106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lodi S, Klein M, Rauch A, Epstein R, Wittkop L, Logan R, et al. Sustained virological response after treatment with direct antiviral agents in individuals with HIV and hepatitis C co-infection. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25:e26048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernandez MD, Sherman KE. HIV/hepatitis C coinfection natural history and disease progression. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:478–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruno G, Saracino A, Scudeller L, Fabrizio C, Dell’Acqua R, Milano E, et al. HCV mono-infected and HIV/HCV co-infected individuals treated with direct-acting antivirals: to what extent do they differ? Int J Infect Dis. 2017;62:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sikavi C, Chen PH, Lee AD, Saab EG, Choi G, Saab S. Hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus coinfection in the era of direct-acting antiviral agents: no longer a difficult-to-treat population. Hepatology. 2018;67:847–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christensen S, Buggisch P, Mauss S, Böker KH, Müller T, Klinker H, et al. Alcohol and cannabis consumption does not diminish cure rates in a real-world cohort of chronic hepatitis C virus infected patients on opioid substitution therapy-data from the German Hepatitis C-registry (DHC-R). Subst Abuse. 2019;13:1178221819835847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.