Abstract

The universal sample processing (USP) multipurpose methodology was developed for the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) and other mycobacterial diseases by using smear microscopy, culture, and PCR (S. Chakravorty and J. S. Tyagi, J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2697-2702, 2005). Its performance was evaluated in a blinded study of 571 sputa and compared with that of the direct and N-acetyl l-cysteine (NALC)-NaOH methods of smear microscopy and culture. With culture used as the gold standard, USP smear microscopy demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity of 98.2% and 91.4%, respectively, compared to 68.6% and 92.6%, respectively, for the direct method. For a subset of 325 specimens, the USP method recorded a 97.1% sensitivity and 83.2% specificity compared to the NALC-NaOH method, which had a sensitivity and specificity of 80.0% and 89.7%, respectively, with culture used as the gold standard. Thus, the USP method exhibited a highly significant enhancement in sensitivity (P < 0.0001) compared to the direct and NALC-NaOH methods of smear microscopy. The USP culture sensitivity was 50.1% and was not significantly different from that of conventional methods (53.6%). The sensitivity and specificity of IS6110 PCR were 99.1% and 71.2%, respectively, with culture used as the gold standard, and increased to 99.7% and 78.8%, respectively, when compared with USP smear microscopy. Thus, the USP methodology was highly efficacious in diagnosing TB by smear microscopy, culture, and PCR in a clinical setting.

The identification of infectious cases is a crucial first step for tuberculosis (TB) control programs worldwide. It relies exclusively on the detection of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in sputum by smear microscopy, which continues to be the mainstay of diagnostic laboratories since its introduction in the late nineteenth century. It is estimated that <20% of approximately 8 million predicted annual cases of TB worldwide are identified as smear positive (15). The targets of a 70% case detection rate and 85% treatment success (22) are not likely to be achieved with the existing methods of smear microscopy. Therefore, there is an urgent and definite need to improve the sensitivity of smear microscopy. In different laboratory settings, the sensitivity of the direct smear method has ranged from 40 to 85% (10, 14, 21; this study), and this method often requires an examination of two or three specimens from the same patient. The inclusion of a concentration step enhanced the sensitivity of the direct smear method, from 54 to 57% to 63 to 80% (5, 9). The N-acetyl l-cysteine (NALC)-NaOH concentration method has shown an improved sensitivity of ∼66 to 83% (8, 16). However, a conflicting report suggests that the overall diagnostic sensitivity of smear microscopy did not increase with sputum liquefaction and concentration (21). New methods of smear microscopy, such as those using household bleach (NaOCl) (10), carboxypropylbetaine (20), chitin (8), and phenol ammonium sulfate (17), have shown sensitivities ranging from 70 to 80%. We have recently described the development and standardization of a novel specimen processing technology, called universal sample processing (USP), for TB diagnosis in both pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens (6a). This enabled highly sensitive smear microscopy (with a sensitivity of detection on the order of 300 to 400 AFB/ml of specimen), culturing of the tubercle bacilli, and the isolation of high-quality inhibitor-free mycobacterial DNA/RNA for PCR/reverse transcription-PCR-based diagnostic assays. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the performance of the USP method in a clinical setting with a panel of respiratory specimens. The USP method was compared with the two most commonly used methods of smear microscopy and culture worldwide, namely, direct smear microscopy and the NALC-NaOH method (developed at the Centers for Disease Control [CDC], Atlanta, Ga., by Kent and Kubica [11] and henceforth referred to as the CDC method).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical specimens.

This study involved 571 sputa which were collected over a period of 18 months from patients (n = 571) attending the Microbiology and DOTS Center at New Delhi Tuberculosis Center, New Delhi, the Sunderlal Jain Charitable Trust Hospital, Delhi, and the Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai, India, for diagnosis of pulmonary TB. The patients chosen for this study were evaluated for any of the following clinical symptoms: fever, cough, expectoration of sputum, hemoptysis, pain, dyspnea, weight loss, night sweats, general weakness, positive chest X-ray, Mantoux status, and any past history of TB. Any specimen collected from a subject already on antitubercular therapy (ATT) at the time of specimen collection was excluded from the study. Adequate amounts of all specimens were first taken for routine TB diagnostic tests at the DOTS Center by the hospital personnel, and the leftover portions were utilized for the present study. The study results thus did not have any bearing on the treatment schedule administered to the subjects at the respective centers.

Specimen processing. (i) Smear microscopy and culture.

All 571 sputum specimens were subjected to direct smear microscopy and processed by the USP method for smear microscopy and culture on Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) slopes. The samples were held for no longer than 24 h at 4°C prior to processing. A subset of 325 samples (with volumes of >5 ml) were also processed by the CDC method of smear microscopy and culture as described previously (11). The USP and CDC methods of smear microscopy and culture were performed on what were considered to be approximately equal aliquots of the sputum samples. Briefly, the USP method involved homogenization and decontamination of the specimens by a treatment with USP solution (4 to 6 M guanidinium hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% Sarkosyl, 0.1 to 0.2 M β-mercaptoethanol) as described in our companion paper (6a). USP solution (1.5 to 2 volumes) was added to each sputum sample, followed by vortexing for 30 to 40 s (optional) or shaking by hand for 1 to 2 min. The homogenate was incubated for 5 to 10 min at room temperature, after which 10 to 15 ml of sterile water or 68 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, was added and mixed. Bloodstained, highly purulent, and/or tenacious sputa were incubated for an additional 10 min. The sample was centrifuged at 5,000 to 6,000 × g at room temperature for 10 to 15 min, and the supernatant was discarded carefully. If the sediment size did not reduce appreciably (to 5 to 10% of the original sputum volume), the sample was washed once more with 2 to 5 ml of USP solution followed by a wash with 10 ml of sterile triple-distilled water. The sediment was used for smear microscopy, culture, and DNA isolation for PCR as described below.

Ten and fifty percent of the processed sediments were used for smear microscopy and culture, respectively. For the CDC method, specimens were processed using an equal volume of 1% NALC-4 to 6% NaOH in 0.1 M trisodium citrate, and the sediments were used for smear microscopy and culture as described previously (11). Direct smear microscopy was independently performed at the DOTS centers and at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) laboratory as described previously (1), while the CDC and USP methods were performed only at the AIIMS laboratory (except for 38 sputum specimens which were processed by the USP methodology at the Tuberculosis Research Centre [TRC], Chennai, India, during a pilot study). All of the slides were subjected to Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining, except for the 38 specimens at the TRC, which were stained by both auramine O and ZN methods. Slide reading was not limited to 300 fields, but rather 400 to 500 fields were read to ensure maximum smear coverage. The only specimens assessed were those for which both the DOTS and the AIIMS direct smear microscopy results were in complete agreement (positive or negative). Barring 5 specimens out of the total of 571, all of the specimens that were positive by direct smear microscopy at the DOTS center and the AIIMS laboratory were of the same grade (1, 2, or 3+). For the five specimens with discrepant results, the AIIMS lab grade was taken into consideration (all were higher than those from the DOTS center).

Culture at the DOTS center and at the TRC was performed by a modified Petroff method (17). Briefly, each sputum sample was homogenized for 15 min in a shaker in the presence of 2% sodium hydroxide (final concentration). After centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 15 min in a clinical centrifuge, the deposit was neutralized with ∼20 ml of sterile distilled water. The sample was recentrifuged and the deposit was inoculated onto LJ medium. All specimens, regardless of the processing method, were inoculated onto LJ slants, incubated at 37°C, and read at weekly intervals for 10 weeks. Any LJ slope showing contamination was safely disposed of. The culture results for all three methods were compiled to ensure that the maximum number of true positive results was detected and because culture was used as the gold standard. Another reason was that the sputum samples were divided and analyzed in two laboratories, and it was necessary not to miss any sample because of inadvertent nonhomogeneous sampling (dividing into aliquots) and/or contamination. These were critical considerations when evaluating the specificity of the USP smear test. Cultures that were positive in the AIIMS laboratory were considered to be truly positive only after confirmation of their identity by AFB staining and devR PCR (18, 19). Cultures that were positive by the modified Petroff method at the TRC and the DOTS center were confirmed to be Mycobacterium tuberculosis by the niacin test.

(ii) DNA isolation and PCR.

DNAs were isolated from the remaining 40% of the USP sediments by boiling in the presence of five times the pellet volume of 10% Chelex-100 resin, 0.03% Triton X-100, and 0.3% Tween 20, as described in our companion paper (6a). The isolated DNAs were used for IS6110-specific PCRs (7) at the AIIMS laboratory, which were performed in 40-μl reaction mixtures containing a 0.5 μM concentration (each) of the primers T4 and T5, 1× PCR buffer [PCR buffer containing (NH4)2SO4; MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania], 1.5 mM MgCl2, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GeneTaq; MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), and 10 μl of specimen DNA. The thermal cycling parameters were 10 min at 94°C, 45 cycles of 1 min at 94°C and 1 min 30 seconds at 60°C, and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. The amplified products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical analysis.

The combined culture results from the AIIMS laboratory and the DOTS center were considered the gold standard when calculating the sensitivity and specificity of smear microscopy. A positive LJ slant at any one lab by any one method of processing (modified Petroff, CDC, or USP method) for the same specimen was considered a true positive. LJ slants that were negative in all labs by all methods were considered true negative samples. The diagnostic accuracy and reliability of the tests compared to the gold standard were assessed by their sensitivities, specificities, and 95% confidence intervals. The test results were classified as true positive (Tp), true negative (Tn), false positive (Fp), and false negative (Fn). The sensitivity and specificity of smear microscopy were calculated by using culture (by all methods) as the gold standard. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR were calculated by using two gold standards: (i) culture positivity (by the modified Petroff/CDC/USP methods) (Table 1) and (ii) USP smear positivity (see Discussion). Sensitivities were calculated as Tp/Tp + Fn × 100, and specificities were calculated as Tn/Tn + Fp × 100. McNemar's test was performed to determine the statistical significance of the differences observed between the smear methods.

TABLE 1.

Results of Ziehl-Neelsen staining of sputum smears prepared by USP and direct methods

| Smear method and resulta | No. of smears | Culture resultb (no. of samples)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| USP | |||

| 3+ | 215 | 208 | 7 |

| 2+ | 78 | 75 | 3 |

| 1+ | 33 | 30 | 3 |

| Scantyc | 17 | 9 | 8 |

| Any positive | 343 | 322 | 21 |

| Negative | 228 | 6 | 222 |

| Total | 571 | 328 | 243 |

| Direct | |||

| 3+ | 47 | 46 | 1 |

| 2+ | 70 | 66 | 4 |

| 1+ | 97 | 94 | 3 |

| Scanty | 29 | 19 | 10 |

| Any positive | 243 | 225 | 18 |

| Negative | 328 | 103 | 225 |

| Total | 571 | 328 | 243 |

3+, >10 AFB per oil immersion field (OIF) (at least 20 fields); 2+, 2 to 10 AFB per OIF (at least 50 fields); 1+, 1 to 99 AFB in 100 OIF; scanty, 1 to 9 AFB in 100 OIF (40).

Using USP, CDC, or modified Petroff method.

All were negative by direct smear microscopy.

RESULTS

The USP method was evaluated for its performance on a panel of 571 sputum specimens by the use of smear microscopy, culture, and PCR and was compared with the two most commonly used methods of smear microscopy, namely, the direct and CDC methods. The results are presented in Tables 1 and 2 and described below.

TABLE 2.

Results of Ziehl-Neelsen staining of sputum smears prepared by USP and CDC methods

| Smear method and result | No. of smears | Culture resulta (no. of samples)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| USP | |||

| 3+ | 103 | 100 | 3 |

| 2+ | 37 | 32 | 5 |

| 1+ | 36 | 22 | 14 |

| Scantyb | 15 | 11 | 4 |

| Any positive | 191 | 165 | 26 |

| Negative | 134 | 5 | 129 |

| Total | 325 | 170 | 155 |

| CDC | |||

| 3+ | 67 | 67 | 0 |

| 2+ | 37 | 32 | 5 |

| 1+ | 35 | 32 | 3 |

| Scanty | 13 | 5 | 8 |

| Any positive | 152 | 136 | 16 |

| Negative | 173 | 34 | 139 |

| Total | 325 | 170 | 155 |

Using USP, CDC, or modified Petroff method.

All were negative by CDC smear microscopy.

USP smears have minimal backgrounds.

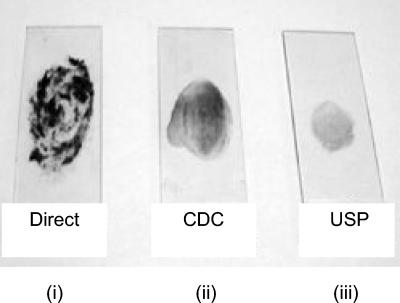

Slides with minimally counterstaining backgrounds were obtained in the case of the USP-treated portions of sputum specimens processed simultaneously by the direct, USP, and CDC methods. This was routinely observed in spite of smearing 10% of the processed material onto slides in the case of USP-treated specimens, in contrast to 2 to 3 loopfuls for the CDC method and only 1 loopful for direct smear microscopy, as prescribed (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Physical appearance of smears. Smears were prepared from equal aliquots of a sputum sample processed by the CDC and USP smear methods. (i) A loopful from the purulent portion of sputum was taken in a 3-mm sterile wire loop and smeared onto a glass slide (direct). (ii) Two loopfuls of specimen processed by the CDC method were smeared onto a glass slide. (iii) Ten percent of the USP sputum was smeared onto a glass slide.

Some negative samples by direct and CDC smear microscopy were positive by the USP smear method.

The sensitivities of the direct and USP smear methods were 68.6% and 98.2%, respectively, and their specificities were 92.6% and 91.4%, respectively (Table 1). All samples diagnosed as positive by the direct method were also positive by USP and CDC smear microscopy. Of the 328 negative samples by the direct smear method (smear-negative samples), the USP method detected 100 additional samples which were also positive by culture, thereby recording an enhancement in sensitivity of 29.6%, which was statistically highly significant (P < 0.0001). Among the additional 100 USP smear-positive and culture-positive samples, 17 were graded as scanty, 29 had a score of 1+, 23 had a score of 2+, and 31 had a score of 3+, proving that the direct smear method sometimes fails to detect specimens with high bacterial loads due to technical errors during smear preparation or faulty reading of slides.

The USP smear method was simultaneously compared with CDC smear microscopy for 325 of the 571 specimens (Table 2). Thirty-nine specimens which were smear negative by the CDC method were detected by the USP method, and all of them were also culture positive. The majority of these 39 specimens which were missed by the CDC method of smear microscopy had small numbers of bacilli, as they predominantly belonged to the scanty or 1+ category. Thus, the USP method showed an enhancement in sensitivity of 17.1% (P < 0.0001) over that of the CDC method (97.1% and 80% sensitivities for USP and CDC smear microscopy, respectively). The specificities of USP and CDC smear microscopy were 83.2% and 89.7%, respectively, and the difference was not significant (P = 0.6; determined by the proportion test with Microstat software).

The differences in specificity among the three methods were not statistically significant, as the values overlapped within their 95% confidence intervals.

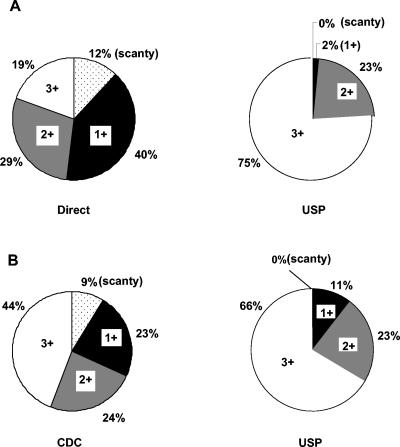

Upgrade in smear status.

The smear grade status was enhanced by the USP smear method; slides graded as scanty, 1+, or 2+ by direct smear microscopy generally were graded as 1+, 2+, or 3+ by USP smear microscopy. Among the 571 specimens, 243 specimens were positive by both the direct and USP methods of smear microscopy. Of these, only 19% belonged to the 3+ category by the direct smear method, in contrast to 75% by the USP method (Fig. 2A). Thus, 56% of the specimens that were positive by the direct smear method were upgraded to the 3+ category by the USP method. The same trend was observed between the USP method and CDC smear microscopy; among 152 specimens positive by both the CDC and USP methods of smear microscopy, 22% were upgraded to the 3+ category by the USP method (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, none of the specimens which were positive by all of the methods of smear microscopy belonged to the scanty category according to USP smear microscopy. Thus, the USP method also fared better than the CDC method in terms of the number of observable bacilli per field.

FIG. 2.

Enhancement of smear grade status of sputum specimens. (A) Percent distribution of different grades of smear positivity by the direct and USP methods of smear microscopy (n = 243). (B). Percent distribution of the different grades of smear positivity by the CDC and USP methods of smear microscopy (n = 152).

USP culture has similar positivity rate but higher decontamination capacity than the conventional methods of culturing.

The USP method of culturing was simultaneously evaluated against the CDC and Petroff methods of culturing. Both the USP and conventional methods showed comparable percentages of positivity; that of the conventional methods (53.6%) was not significantly higher than that of the USP method (50.1%) (the values overlap within their 95% confidence intervals). However, the USP method proved to be very efficient at decontamination and yielded fewer contaminated cultures (n = 5) than conventional methods (n = 21), thereby making it more suitable for use in tropical countries.

The USP method enables the isolation of high-quality, inhibitor-free, PCR-amplifiable mycobacterial DNA.

High-quality, inhibitor-free mycobacterial DNAs for PCR were isolated by the USP method from all 571 sputa. With culture considered the gold standard, IS6110 PCR showed a sensitivity and specificity of 99.1% and 71.2%, respectively (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of IS6110 PCR test on sputum processed by USP method

| PCR result | No. of samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culturea

|

USP smear

|

|||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |

| Positive | 325 | 70 | ||

| Negative | 3 | 173 | ||

| Total (n = 571) | 328 | 243 | ||

| Positive | 342 | 47 | ||

| Negative | 1 | 175 | ||

| Total (n = 565b) | 343 | 222 | ||

Using USP, CDC, or modified Petroff method.

Only 565 of 571 samples were analyzed with USP smear as the gold standard since 6 specimens were USP smear negative but culture positive.

DISCUSSION

The sensitivity of USP smear microscopy was 97 to 98%, in contrast to 68% for the direct smear method and 80% for the CDC method; the 18 to 30% enhancement in sensitivity was highly significant (P < 0.0001). Patients with positive smears are responsible for the maximum transmission of TB through a population. Yet recent studies using molecular tools have indicated that smear-negative TB cases contribute much more to ongoing transmission than was previously believed (3), and this effect is likely larger as smear-negative cases progress. AFB smear-negative cases of pulmonary TB account for about 30% of pulmonary cases and 50% of all cases (22). The extraordinary sensitivity of the USP smear method, coupled with its ability to process all types of pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens, will enable the correct identification of a sizeable population of infected individuals, particularly those with paucibacillary TB, who would otherwise escape detection by conventional methods. Only 6 culture-positive specimens were missed by USP smear microscopy versus 103 by direct smear microscopy. Likewise, only 5 culture-positive specimens were missed by USP smear microscopy versus 34 by CDC smear microscopy. Therefore, the USP method will have widespread utility in national TB control programs in economically vulnerable nations, whose first component is case detection by smear microscopy.

In terms of its usefulness for cell culture, the USP method was not significantly different from the conventional methods; 50.1% and 53.6% positivity rates were noted for the USP and conventional methods of culturing, respectively. However, owing to the fact that the USP solution is at a neutral pH, the cumbersome step of neutralizing decontaminated specimens before culturing is avoided. Another positive feature of USP processing is the reduced rate of contamination (0.88%) compared to that of NALC-NaOH processing, which yielded a contamination rate of 3.68% in the present study.

None of the USP specimens inhibited PCR, and with culture as the gold standard, the sensitivity of IS6110 PCR was 99.1%. However, the specificity was only a modest 71.2%. We found the culture positivity rate of ∼56% (322/571) to be lower than that of USP smears, at 60% (343/571), which highlights the limitation of using culture as a gold standard. In a high-incidence setting such as India, where the yield of atypical mycobacteria is negligible, smear positivity is a far more useful criterion for diagnosing active TB. For the present study, since (i) USP smear microscopy was highly specific and showed a better diagnostic yield than culture and (ii) a consensus was reached by an American Thoracic Society workshop on direct amplification tests stating that when an AFB smear and a direct amplification test are positive, the diagnosis of TB can be considered established (2), the diagnostic yield by PCR was also evaluated against that by USP smear microscopy (as the gold standard). Only 565 of 571 samples were analyzed, as six specimens were USP smear negative but culture positive. For smear-positive specimens, the specificity of PCR increased to 78.8% (7.6% increment), while the sensitivity showed a marginal change to 99.7%. Forty-seven specimens were culture negative and USP smear negative but PCR positive. From a clinical standpoint, they seemed to be false positive, and the clinical relevance of positive PCR results to this group is questionable. These specimens undoubtedly belonged to the paucibacillary category, if they were truly positive at all, since the detection limit of USP smear microscopy may be safely estimated to be ∼300 to 500 bacilli/ml of specimen.

Suspected false-positive PCR results must be analyzed in various ways. First, in a country where the disease is endemic, such as India, a significant number of persons are infected with M. tuberculosis but do not have clinical signs. PCR has been reported to identify as positive repeatedly culture-negative specimens obtained from patients not diagnosed with TB because they were asymptomatic (4). Furthermore, PCR has been reported to identify noncultivable bacteria from patients already under therapy until a period of 5 to 11 months after the first evaluation (4). In our study, we excluded all specimens from patients on ATT at the time of specimen collection. However, the 47 “false-positive” specimens were all direct smear negative and were obtained from patients with cough and chest pain but without any strong clinical index of suspicion suggestive of TB. Per the norms set by the Revised National TB Control Programme, this group of patients (direct smear negative and with a nonacute clinical presentation) were not evaluated further, and therefore information regarding their previous TB history or ATT status, if any, was not available to us. Thus, the apparent false positivity may be a reflection of noncultivable bacteria in the specimens or of the high sensitivity of the PCR assay, which can even identify asymptomatic individuals infected with tubercle bacilli. For these reasons, a relatively low specificity has been considered acceptable in countries where the disease is endemic due to the small numbers of noninfected patients being screened, provided the sensitivity is not compromised (9a).

Second, technical factors that could have restricted the specificity to ∼79% include the following. (i) Since the sputum specimens were procured from a routine microbiological laboratory handling a large number of specimens on a daily basis, cross-contamination at the sample level could not be ruled out, as such settings could be a frequent source of contamination (6). (ii) Possible cross-contamination could have occurred during specimen processing, although we followed guidelines for molecular diagnostic methods, including a unidirectional workflow comprising the physical separation of specimen processing, reagent preparation, and use of positive and negative controls during PCR amplification (12, 13). Moreover, specimen processing using the USP methodology is very simplified and involves minimal tube-to-tube transfer and no organic extraction or precipitation steps, which frequently contribute to cross-contamination. However, the possible occurrence of carryover contamination during PCR cannot be excluded since a uracil DNA glycosylase-dUTP system was not used. (iii) Every effort was made to minimize the uneven distribution of bacilli during sample processing. However, due to the inherent nature of mycobacteria to form clumps, this could still have occurred among the aliquots processed for smear microscopy, culture, and PCR and may have resulted in an insufficient number of bacilli which were suitable only for detection by IS6110 PCR but not by smear microscopy and culture.

Third, another aspect that may have contributed to the occurrence of false-positive specimens is the inherent sensitivity of the PCR assay that targets the multicopy IS6110 sequence. In our hands, apart from the M. tuberculosis complex organisms, this assay could amplify only the DNA of M. phlei from among several MOTT bacilli examined. Furthermore, IS6110 PCR was negative for a panel of extrapulmonary and pulmonary specimens obtained from patients with diseases diagnosed to be other than TB (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, malignancy, etc.), thereby establishing the specificity of the assay in a clinical setting. We do not therefore believe that the choice of IS6110 as a target contributed to the detection of smear-negative and culture-negative specimens that made up the “false-positive” group of subjects. Rather, many, if not all, of these samples could be paucibacillary in nature, from asymptomatic subjects, and/or comprised of noncultivable bacteria from patients previously on ATT.

In summary, the utility of the USP method as a robust, versatile, and superior alternative to the conventional methods of TB diagnosis by smear microscopy and culture has been validated in the present study. The USP technology enables processing of the entire sample for use in all conventional and nucleic acid amplification-based tests without resorting to using portions for individual tests, thereby minimizing unequal distributions of mycobacteria and equivocal interpretations of test results. Combining the three diagnostic modalities of smear microscopy, culture, and PCR within a single sample-processing platform by USP will enable a definitive identification of individuals afflicted with TB and other mycobacterial diseases in a variety of clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. R. Narayanan and N. Selvakumar, Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai, India, for their encouragement and support. The technical assistance of Divya Pathak, Sanjay Kumar, and Neelu Malhotra and the assistance with statistical analysis of Rajvir Singh and M. Kalaivani are duly acknowledged. A. B. Dey is acknowledged for his critical comments and suggestions during the course of this study. J.S.T. is thankful to P. K. Dave for encouragement and timely support.

S.C. is thankful to I.C.M.R. for a senior research fellowship. M.D. is thankful to Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for a fellowship under the post-MD/MS training program at Department of Biotechnology, AIIMS, during which period part of the validation on sputum samples was performed. Financial support to J.S.T. from AIIMS is acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhtar, M., G. Bretzel, F. Boulahbal, D. Dawson, L. Fattorini, K. Feldmann, T. Frieden, M. Havelková, I. N. de Kantor, S. J. Kim, R. Küchler, F. Lamothe, A. Laszlo, N. M. Casabona, A. C. McDougall, H. Miörner, G. Orefici, C. N. Paramasivan, S. R. Pattyn, A. Reniero, H. L. Rieder, J. Ridderhof, S. Rüsch-Gerdes, S. H. Siddiqi, S. Spinaci, R. Urbanczik, V. Vincent, and K. Weyer. 2000. Technical guide: sputum examination for tuberculosis by direct microscopy in low income countries, 5th ed. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France.

- 2.American Thoracic Society. 1997. Rapid diagnostic tests for tuberculosis: what is the appropriate use? American Thoracic Society Workshop. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155:1804-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr, M. A., S. A. Warren, H. Salamon, P. C. Hopewell, A. Ponce de Leon, C. L. Daley, and P. M. Small. 1999. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients smear-negative for acid-fast bacilli. Lancet 353:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beige, J., J. Lokies, T. Schaberg, U. Finckh, M. Fischer, H. Mauch, H. Lode, B. Kohler, and A. Rolfs. 1995. Clinical evaluation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:90-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruchfeld, J., G. Aderaye, I. B. Palme, B. Bjorvatn, G. Kallenius, and L. Lindquist. 2000. Sputum concentration improves diagnosis of tuberculosis in a setting with a high prevalence of HIV. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94:677-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugière, O., M. Vokurka, D. Lecossier, G. Mangiapan, A. Amrane, B. Milleron, C. Mayaud, J. Cadranel, and A. J. Hance. 1997. Diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary tuberculosis using sequence capture polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 155:1478-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Chakravorty, S., and J. S. Tyagi. 2005. Novel multipurpose methodology for detection of mycobacteria in pulmonary and extrapulmonary specimens by smear microscopy, culture, and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2697-2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenach, K. D., M. D. Cave, J. H. Bates, and J. T. Crawford. 1990. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of repetitive DNA sequence specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 161:977-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farnia, P., F. Mohammadi, Z. Zarifi, D. J. Tabatabee, J. Ganavi, K. Ghazisaeedi, P. K. Farnia, M. Gheydi, M. Bahadori, M. R. Masjedi, and A. A. Velayati. 2002. Improving sensitivity of direct microscopy for detection of acid-fast bacilli in sputum: use of chitin in mucus digestion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:508-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garay, J. E. 2000. Analysis of a simplified concentration sputum smear technique for pulmonary tuberculosis diagnosis in rural hospitals. Trop. Doct. 30:70-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Goldberger, M. 1997. Regulatory issues for new devices. WHO Tuberculosis Diagnostics Workshop, Cleveland, Ohio.

- 10.Habeenzu, C., D. Lubasi, and A. F. Fleming. 1998. Improved sensitivity of direct microscopy for detection of acid-fast bacilli in sputum in developing countries. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92:415-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent, P. T., and G. P. Kubica. 1985. Public health mycobacteriology. A guide to the level III laboratory. Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga.

- 12.Kwok, S., and R. Higuchi. 1989. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature 339:237-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCreedy, B. J., and T. H. Callaway. 1993. Laboratory design and work flow, p. 149-159. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 14.Perera, J., and D. M. Arachchi. 1999. The optimum relative centrifugal force and centrifugation time for improved sensitivity of smear and culture for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from sputum. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93:405-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins, M. D. 2000. New diagnostic tools for tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 12:S182-S188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott, C. P., L. Dos Anjos Filho, F. C. De Queiroz Mello, C. G. Thornton, W. R. Bishai, L. S. Fonseca, A. L. Kritski, R. E. Chaisson, and Y. C. Manabe. 2002. Comparison of C(18)-carboxypropylbetaine and standard N-acetyl-l-cysteine-NaOH processing of respiratory specimens for increasing tuberculosis smear sensitivity in Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 9:3219-3222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selvakumar, N., F. Rahman, R. Garg, S. Rajasekaran, N. S. Mohan, K. Thyagarajan, V. Sundaram, T. Santha, T. R. Frieden, and P. R. Narayanan. 2002. Evaluation of the phenol ammonium sulfate sedimentation smear microscopy method for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3017-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh, K. K., M. Muralidhar, A. Kumar, T. K. Chattopadhyaya, K. Kapila, M. K. Singh, S. K. Sharma, N. K. Jain, and J. S. Tyagi. 2000. Comparison of in house polymerase chain reaction with conventional techniques for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in granulomatous lymphadenopathy. J. Clin. Pathol. 53:355-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh, K. K., M. D. Nair, K. Radhakrishnan, and J. S. Tyagi. 1999. Utility of PCR assay in diagnosis of en-plaque tuberculoma of the brain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:467-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornton, C. G., K. M. MacLellan, T. L. Brink, Jr., D. E. Lockwood, M. Romagnoli, J. Turner, W. G. Merz, R. S. Schwalbe, M. Moody, Y. Lue, and S. Passen. 1998. Novel method for processing respiratory specimens for detection of mycobacteria by using C18-carboxypropylbetaine: blinded study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1996-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson, D., and A. W. Sturm. 1997. Diagnosing tuberculosis in a resource-poor setting: the value of sputum concentration. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91:420-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. W.H.O. Report 2002. W.H.O./CDS/TB/2002.295. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Online.] http://www.who.int/gtb/publications/globrep02/index.html.