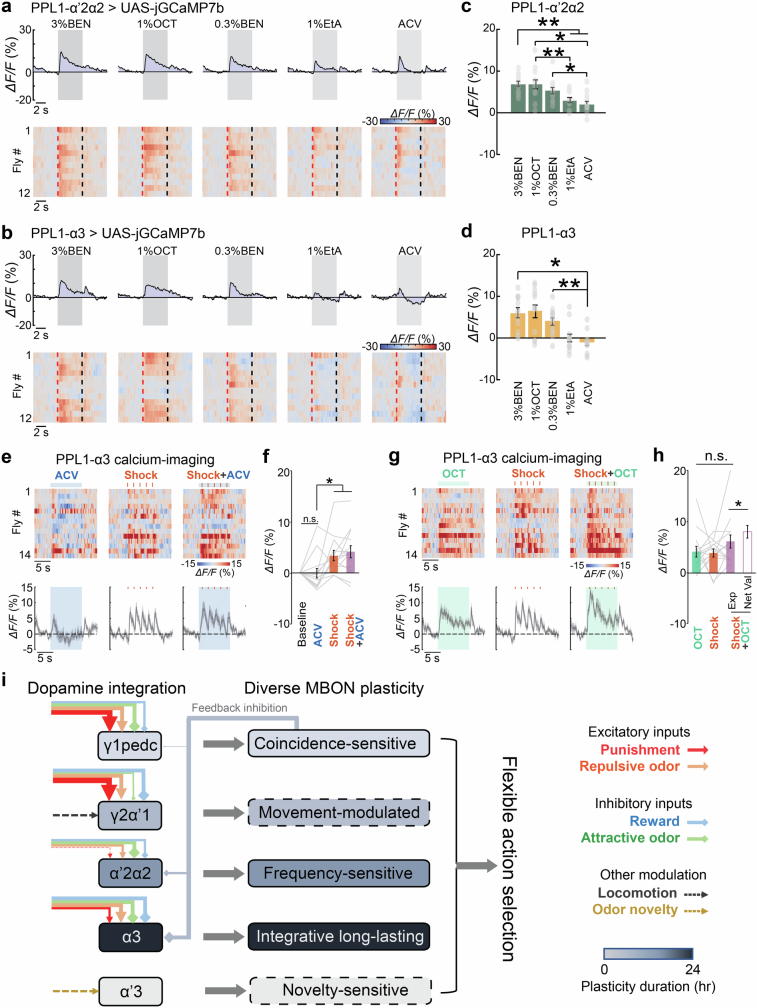

Extended Data Fig. 13. Unlike voltage imaging, Ca2+ imaging does not accurately report decreases in spiking and thereby fails to capture the integration of valences encoded by the spiking of PPL1 dopamine neurons.

a, b) Top plots, Time-dependent mean fluorescence Ca2+ signals (ΔF/F) evoked in the PPL1-α’2α2 (R82C10-LexA > 13×LexAop-jGCaMP7b), a, and PPL1-α3 neurons (MB065B > 20×UAS-jGCaMP7b), b, by 5 different odours (3% BEN, 1% OCT, 0.3% BEN, 1% EtA, and ACV). Gray shading marks the duration of odour presentation. Bottom plots, Odour-evoked changes in Ca2+ activity in 12 individual flies. Each row shows data from a single fly. Vertical dashed lines mark the onset (red) and offset (black) of odour presentation. Comparison to Extended Data Fig. 3f,g shows that Ca2+ imaging poorly captures the bidirectional encoding of innate odour valences. c, d) Mean changes in odour-evoked Ca2+ activity relative to baseline levels in PPL1-α’2α2, c, and PPL1-α3, d, averaged across the 5 s of odour presentation. Error bars: s.e.m. across 12 flies per neuron-type. (*P < 0.05; n = 12 flies; Friedman ANOVA followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction). Gray dots indicate data from individual flies. e) Top, Changes in Ca2+ activity (ΔF/F) in the PPL1-α3 neuron immediately before, during and after 10-s-exposures to apple cider vinegar (ACV; horizontal blue line; left), 5 electric-shock pulses (each 0.2 s in duration with 1.8 s interval between pulses; red ticks mark the times of the individual shock pulses; middle), or the paired presentation of ACV and shocks (right) to n = 14 female flies (MB065B > 20×UAS-jGCaMP7b; 1 trial per fly for each of the 3 stimulation conditions). Bottom, Traces showing the time-dependent, mean Ca2+ activity, averaged over all 14 trials for each stimulus. Horizontal dashed lines: Mean baselines, averaged over the first 5 s of recording. Blue shading covers the periods of odour presentation. Shading on time traces: s.e.m over 14 flies. f) Mean ± s.e.m. odour-evoked changes in the Ca2+ activity of the PPL1-α3 neuron, as measured during 10-s-exposures to ACV (blue bar), 5 electric shocks (red bar), or the paired presentation of ACV and shocks (purple bar). (*P < 0.05; n = 14 flies; Friedman ANOVA followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction). Gray lines: Data from individual flies. Changes in the Ca2+ activity in response to ACV was statistically indistinguishable from the baseline activity before ACV exposure. Changes in the Ca2+ activity in response to shocks alone and joint presentations of ACV and shocks have no significant difference from each other (n = 14 flies; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Comparison to the data of Fig. 4e, g shows that Ca2+ imaging poorly captures the ACV-evoked suppression of spiking and the encoding of the net valence of shocks paired with ACV presentation. g) Plots analogous to those of e, except the odour used (1% OCT) was innately repulsive. h) Mean ± s.e.m. odour-evoked changes in the Ca2+ activity of the PPL1-α3 neuron, as measured during 10-s-exposures to 1% OCT (green bar), 5 electric shocks (red bar), or the paired presentation of OCT and shocks (purple solid bar). (n = 14 flies; Friedman ANOVA followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm-Bonferroni correction). Gray lines: Data from individual flies. Changes in Ca2+ activity in response to the joint presentation of OCT and shocks were significantly different from the sum of the changes induced by the two stimulus-types, when each was presented independently (purple hollow bar) (*P < 0.05; n = 14 flies; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Comparison to the data of Fig. 4f,h shows that Ca2+ imaging fails to report the encoding of the net valence of shocks paired with OCT presentation, due to saturation of the Ca2+ indicator response during strong neuronal excitation. i) Schematic showing how the parallel-recurrent circuitry of the mushroom body (MB) may allow the integration of innate and learnt valence signals in a heterogeneous manner across the different learning units. PPL1-DANs innervate different compartmentalized regions on Kenyon cells (KC) axons and form parallel learning units together with their corresponding downstream mushroom body output neurons (MBONs). Sensory stimuli with innate negative valences, such as punishments (red) and repulsive odours (orange), heterogeneously excite PPL1-γ1pedc, PPL1-γ2α’1, PPL1-α’2α2, and PPL1-α3. Whereas sensory stimuli with positive valences, such as rewards (blue) and attractive odours (green), inhibit the 4 PPL1-DANs. During associative conditioning with an aversive US, each individual PPL1-DAN may integrate the valences of stimuli presented concurrently and provide a distinctive teaching signal that drives a depression of KC → MBON synapses. Plasticity in MBON-γ1pedc > α/β lasts for ~1 h and reduces the strength of the inhibitory feedback from MBON-γ1pedc > α/β to PPL1-α’2α2 and PPL1-α3, which in turn facilitates the formation of long-lasting plasticity in those learning units. In addition, the PPL1-γ2α’1 neuron is modulated by the fly’s movement13,29, whereas PPL1-α’3 seems to encode odour novelty21. Owing to the integration of the innate and learnt valences encoded by PPL1-DAN spiking and to the varying durations of MBON plasticity, the MB’s parallel-recurrent circuitry can enact diverse plasticity patterns that shape fly behavior in a flexible manner.