This cohort study analyzes associations of criminal sanctions with mortality among people with psychosis in the criminal legal system of New South Wales, Australia.

Key Points

Question

Are recent criminal sanctions or court diversion associated with mortality in people with psychosis?

Findings

In this cohort study of 83 071 adults with psychosis, compared with no recent criminal sanction, recent mental health court diversion, community sanctions, and prior imprisonment were associated with a statistically significant increase in the hazards of all-cause and external-cause mortality.

Meaning

These findings suggest that mortality is elevated among people with psychosis following receipt of criminal sanctions, indicating a need for effective interventions and models of care to improve the health and safety of this group.

Abstract

Importance

People living with psychosis experience excess premature mortality and are overrepresented in criminal legal systems, but little is known about mortality associated with criminal sanctions or diversion in this population.

Objective

To examine associations of different types of recent (past 2 years) criminal sanction, including court diversion, with mortality among people with psychosis.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based, retrospective, data-linkage cohort study was conducted using 6 routinely collected administrative data collections from New South Wales, Australia, relating to health, court proceedings, imprisonment, and mortality. Participants (adults aged ≥18 years hospitalized for psychotic disorders) entered observation at the time of discharge from their first psychosis-related hospital admission (or their 18th birthday if aged <18 years) between July 2001 and November 2017 and were followed-up until May 2019. Data were analyzed between February 2023 and April 2024.

Exposures

Recent (past 2 years) criminal sanction type, a time-varying variable with 5 categories: no recent criminal sanction, recent mental health court diversion, recent community sanction, current imprisonment, and recent prior imprisonment (ie, recent prison release).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Causes of death were described, and age- and sex-specific mortality rates by recent criminal sanction type were calculated. In those younger than 65 years, Cox regression was used to examine associations of all-cause and external-cause mortality with recent criminal sanction type, adjusting for sociodemographic, health-related, and offense-related confounders.

Results

The cohort included 83 071 persons (35 791 female [43.1%]; 21 208 aged 25-34 years [25.5%]; median [IQR] follow-up, 9.5 [4.8-14.2] years), of whom 25 824 (31.1%) received a criminal sanction. There were 11 355 deaths. In those aged younger than 65 years, recent mental health court diversion, community sanctions, and prior imprisonment were associated with increased hazards of all-cause and external-cause mortality compared with no recent sanction, with the largest adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) observed for recent prior imprisonment (all-cause mortality: aHR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.50-1.91; external-cause mortality: aHR, 2.64; 95% CI, 2.27-3.06).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study of people with psychosis, recent criminal sanctions were associated with increased mortality irrespective of sanction type. These findings suggest that future research should develop strategies to improve health and safety in people with psychosis who have criminal legal system contact.

Introduction

People living with psychosis experience greatly increased premature mortality compared with their peers.1,2 Criminal legal system (CLS) involvement may be one important risk factor, given the overrepresentation of people with psychosis in prisons3 and CLSs worldwide.4 In general population studies, imprisonment5 and community sanctions6 are associated with increased age- and sex-adjusted mortality risks, with particularly elevated risks of fatal overdose and suicide after prison release.5,7 Similarly, North American8 and European9,10,11 studies among cohorts with psychosis or serious mental illness (SMI) report increased risks of all-cause mortality9,12 and suicide8,10,11 associated with either criminal convictions8,9,10,11 or imprisonment,12 although a Danish study13 found no association of criminal sentencing to psychiatric treatment with all-cause mortality.

Globally, many jurisdictions provide alternative CLS pathways for people with SMI, including at trial (eg, fitness considerations and diminished or nonresponsibility findings) and/or disposition (eg, secure placement or sentencing to psychiatric treatment).14,15,16 Numerous jurisdictions, including in North America, the UK, and Australia, have also introduced mechanisms such as court diversion programs and mental health courts to divert people with SMI accused of less serious offenses into alternative pathways, often including psychiatric treatment.17,18 Aims include reducing recidivism and improving health and treatment access.18

With previous studies examining single sanction types12,13 or criminal convictions,8,9,10,11 it is unclear whether mortality risks in people with psychosis vary by sanction type, including diversionary alternatives. To address this, we aimed to investigate associations of different types of recent (past 2 years) criminal sanctions—including mental health court diversion—with mortality among people with psychosis in New South Wales (NSW), Australia between 2001 and 2019. We focused on a 2-year time frame because mortality risks associated with CLS involvement decline beyond this time point,5 with later deaths likely reflecting extraneous factors. Specifically, we aimed to (1) describe rates and causes of mortality by recent criminal sanction type and (2) examine associations of recent criminal sanction type with all-cause and external-cause mortality among people with psychosis.

Methods

Study Design

This population-based, retrospective, data-linkage cohort study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee, and the ethics committees of the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council, Corrective Services NSW (CSNSW), and the NSW Justice Health and Forensic Mental Health Network. The reporting of the study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.19 We used 6 routinely collected administrative data collections from NSW, Australia (July 2001 to May 2019 unless stated): the Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC), recording public and private hospital admissions; the Emergency Department Data Collection (EDDC), recording ED presentations (January 2005 to May 2019); the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research Reoffending Database (RoD), recording criminal charges, convictions, and penalties (minor traffic offenses excluded); the CSNSW Offender Integrated Management System (OIMS), recording imprisonments in adult prisons; and the NSW Register of Births, Deaths, and Marriages death registrations (RBDM-DR) and Australian Coordinating Registry Cause of Death Unit Record File (COD-URF), recording deaths and (COD-URF only) causes of deaths registered in NSW.

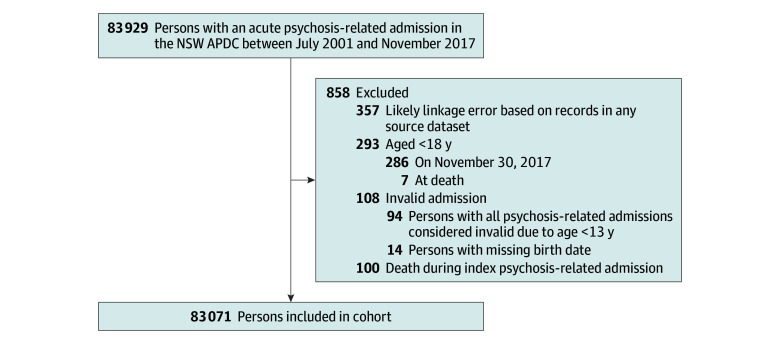

Study Population

Our cohort included all adults (≥18 years) discharged from an acute psychosis-related hospital admission recorded in the APDC from July 1, 2001, to November 30, 2017. Participants entered the study at discharge from their first (index) psychosis-related admission during this period or their 18th birthday if younger than 18 years at discharge (provided this was before November 30, 2017). We analyzed follow-up data to May 31, 2019. Psychosis-related admissions were those with a principal diagnosis (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10]) of organic and puerperal psychoses (F06.0, F06.2, or F53.1), substance-induced psychoses (F1x.5 [x represents a wildcard character]), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (F20, or F22-F29), and/or affective disorders with psychotic symptoms (F30.2, F31.2, F31.5, F32.3, or F33.3). We excluded admissions at younger than 13 years due to potential diagnostic uncertainty. We excluded participants with suspected linkage error (see eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1) or who died during their index admission (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participant Selection Flow Diagram.

APDC indicates Admitted Patient Data Collection; NSW, New South Wales.

Procedures

The NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage performed the data linkage using ChoiceMaker software version 2.7.2 (ChoiceMaker, LLC), employing a probabilistic method with a targeted 0.5% false-positive rate.20 We received only deidentified data. Information on exclusion criteria for individual records is available in eAppendix 2 in Supplement 1.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality (RBDM-DR and COD-URF). The secondary outcome was external-cause mortality (COD-URF; ie, deaths with an underlying cause of psychoactive substance use [ICD-10 codes F11-F19], abuse of nondependence-producing substances [ICD-10 code F55], or external causes of morbidity and mortality [ICD-10 Chapter XX]). We also identified deaths due to accidental drug overdose (ICD-10 codes F11-F16, F18, F19, or X40-X44), suicide including undetermined intent (ICD-10 codes X60-X84, Y10-Y34, Y87.0, or Y87.2), undetermined or unknown cause (ICD-10 code R99 or missing) and disease-related causes (deaths not categorized as external-cause or undetermined or unknown).

Main Exposure

The main exposure was recent (past 2 years) adult criminal sanction type, a time-varying variable with 5 mutually exclusive categories: no recent criminal sanction, recent mental health court diversion, recent community sanction, current imprisonment, and recent prior imprisonment (ie, recent prison release). Participants’ exposure category on any given follow-up date reflected sanctions received in the preceding 2 years. To account for multiple simultaneous sanctions and known differences in mortality risks in prison vs community settings,7,21,22 we applied a hierarchical classification whereby current imprisonment overrode all other categories; prior imprisonment and mental health court diversion overrode community sanctions, and mental health court diversion and prior imprisonment overrode each other depending on which was more recent.

We ascertained adult community sanctions (court-ordered penalties such as fines, community service, and supervision orders) and mental health court diversion (charge dismissal under Sections 32 or 33 of the NSW Mental Health [Forensic Provisions] Act 199023) from the RoD. Sections 32 and 33 enabled the lower courts to dismiss relatively minor (summary) charges against defendants with mental illness and order that they receive assessment, treatment, or support (see eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1). We excluded juvenile-specific sanctions and sanctions or diversions finalized in a juvenile jurisdiction or before the 18th birthday. We ascertained current and prior adult imprisonment (any imprisonment, remand or sentenced, and in an adult prison on or after the 18th birthday, including those commencing before and continuing on this date) from OIMS; prior imprisonment commenced the day after each imprisonment end date. We defined no recent criminal sanction as no community sanction, mental health court diversion, or imprisonment in the preceding 2 years. A small number of participants (616 participants) received not guilty by reason of mental illness verdicts or other or unspecified mental health dismissals; we did not consider these criminal sanctions, except local court dismissals before 2005, which were not differentiated from Section 32 or 33 dismissals. See eAppendix 4 in Supplement 1 for further detail regarding exposure.

Covariates

We ascertained sex from the APDC, EDDC, RoD, and COD-URF. We ascertained Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (hereafter, respectfully, Aboriginal) identity from the APDC, EDDC, RoD, OIMS, and COD-URF using a validated multistage median algorithm.24 We calculated time-updated age using birthdates in the APDC, EDDC, RoD, and RBDM-DR, grouped into year bands (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, and ≥65 years). We ascertained marital status, residential Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD), and residential remoteness at index admission from the APDC, mapping 2011 Statistical Local Area codes to the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 IRSD scores25 and Australian Statistical Geography Standard26 to derive IRSD (reclassified into tertiles within NSW) and remoteness, respectively. We ascertained history of problematic drug use (ICD-10 codes F11-F16, F18-F19, T40, or T43.6; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes 292, 304, or 305.2-305.9) and alcohol use (ICD-10 codes F10, T51, X45, X65, Y15, or Y90-91; or ICD-9 codes 291, 303, or 305.0) at study entry from the APDC and EDDC. Some EDDC diagnoses used Systematized Nomenclature for Medicine–Clinical Terminology (Australian release) codes, which we selected using the US National Library of Medicine Unified Medical Language System map27 and PyMedTermino2 software28 with Python version 3.9 (Python Software Foundation) followed by manual review (see eAppendix 5 in Supplement 1). We ascertained past-year Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),29 a validated physical comorbidity score from 0 to 24, from the APDC (reclassified into 0, 1-2, and ≥2) as a time-varying covariate updated every birthday. We ascertained whether the index admission was voluntary or involuntary (a proxy for psychosis severity) from the APDC. We ascertained offense history at study entry from the RoD using juvenile and adult offenses that received a guilty or not guilty by reason of mental illness verdict or mental health dismissal, categorized as violent (Australian and New Zealand Society of Criminology offense groups 1-630), nonviolent only (offense groups 7-16), and none. Covariates were identified as potential confounders a priori, informed by a directed acyclic graph (see eAppendix 6 in Supplement 1).31 Unknown or missing values were minimal (<3% for all covariates except marital status) and were combined with the most common category.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated age- and sex-specific mortality rates per 1000 person-years with 95% CIs using a Poisson distribution and proportions of deaths by cause, descriptively. For both sexes separately and combined, we modeled associations of recent criminal sanction type with all-cause and external-cause mortality using Cox regression, both unadjusted and adjusted. Model 1 was adjusted for basic sociodemographics including age and sex. Model 2 was adjusted for expanded sociodemographics including age, sex, Aboriginal identity, marital status, IRSD, and remoteness. Model 3 was maximally adjusted using model 2 covariates plus problematic drug use, problematic alcohol use, involuntary index admission, CCI score, and offense history. Model selection was theory-driven (see eAppendix 6 in Supplement 1). The statistical significance level (α) was prespecified at .05. Proportional hazards assumptions for all variables in all models were deemed reasonable by inspecting log-log survival plots and plots of scaled Schoenfeld residuals vs analysis time. Because the age-specific mortality rates indicated that age moderated associations of recent criminal sanction type with mortality, with different patterns in those aged 65 years or older vs younger, we restricted survival analyses to those younger than 65 years; among those 65 years or older, there were insufficient person-years and events in most exposure categories. Data were analyzed between February 2023 and April 2024 using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and STATA version 18 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

We identified 83 071 adults (35 791 female [43.1%]; 21 208 aged 25-34 years [25.5%]; 7984 Aboriginal [9.6%]) with a psychosis-related hospital admission in NSW between July 2001 to November 2017 (median [IQR] follow up, 9.5 [4.8-14.2] years). Table 1 presents further baseline characteristics (see also eTables 1-4 in Supplement 1).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Study Entry.

| Characteristic | Participants by sanction type, No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No sanction (n = 72 236) | Community (n = 5978) | Diversion (n = 1043) | Imprisonment | Total (N = 83 071) | ||

| Current (n = 1136) | Prior (n = 2678) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female or othera | 33 623 (46.5) | 1427 (23.9) | 222 (21.3) | 117 (10.3) | 402 (15.0) | 35 791 (43.1) |

| Male | 38 613 (53.5) | 4551 (76.1) | 821 (78.7) | 1019 (89.7) | 2276 (85.0) | 47 280 (56.9) |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 18-24 | 14 102 (19.5) | 1657 (27.7) | 239 (22.9) | 281 (24.7) | 636 (23.7) | 16 915 (20.4) |

| 25-34 | 17 118 (23.7) | 2096 (35.1) | 354 (33.9) | 474 (41.7) | 1166 (43.5) | 21 208 (25.5) |

| 35-44 | 14 979 (20.7) | 1479 (24.7) | 267 (25.6) | 259 (22.8) | 660 (24.6) | 17 644 (21.2) |

| 45-54 | 10 982 (15.2) | 571 (9.6) | 122 (11.7) | 91 (8.0) | 187 (7.0) | 11 953 (14.4) |

| 55-64 | 6884 (9.5) | 137 (2.3) | 46 (4.4) | 27 (2.4) | 27 (1.0) | 7121 (8.6) |

| ≥65 | 8171 (11.3) | 38 (0.6) | 15 (1.4) | <5 (NS) | <5 (NS) | 8230 (9.9) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity | ||||||

| Yes | 5360 (7.4) | 1226 (20.5) | 175 (16.8) | 356 (31.3) | 867 (32.4) | 7984 (9.6) |

| No | 66 622 (92.2) | 4752 (79.5) | 868 (83.2) | 780 (68.7) | 1811 (67.6) | 74 833 (90.1) |

| Missing or unknown | 254 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 254 (0.3) |

| Residential Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage | ||||||

| Least disadvantaged | 28 399 (39.3) | 1813 (30.3) | 390 (37.4) | 270 (23.8) | 680 (25.4) | 31 552 (38.0) |

| Moderately disadvantaged | 22 145 (30.7) | 1962 (32.8) | 289 (27.7) | 117 (10.3) | 902 (33.7) | 25 415 (30.6) |

| Most disadvantaged | 17 877 (24.7) | 1825 (30.5) | 283 (27.1) | 735 (64.7) | 910 (34.0) | 21 630 (26.0) |

| Interstate resident | 2164 (3.0) | 75 (1.3) | 22 (2.1) | 6 (0.5) | 16 (0.6) | 2283 (2.7) |

| Missing or unknown | 1651 (2.3) | 303 (5.1) | 59 (5.7) | 8 (0.7) | 170 (6.3) | 2191 (2.6) |

| Residential remoteness | ||||||

| Major cities | 51 173 (70.8) | 3854 (64.5) | 781 (74.9) | 1005 (88.5) | 1739 (64.9) | 58 552 (70.5) |

| Inner regional | 13 490 (18.7) | 1279 (21.4) | 149 (14.3) | 100 (8.8) | 551 (20.6) | 15 569 (18.7) |

| Outer regional or remote | 3758 (5.2) | 467 (7.8) | 32 (3.1) | 17 (1.5) | 202 (7.5) | 4476 (5.4) |

| Interstate resident | 2164 (3.0) | 75 (1.3) | 22 (2.1) | 6 (0.5) | 16 (0.6) | 2283 (2.7) |

| Missing or unknown | 1651 (2.3) | 303 (5.1) | 59 (5.7) | 8 (0.7) | 170 (6.3) | 2191 (2.6) |

| Married (including de facto) | ||||||

| Yes | 16 658 (23.1) | 697 (11.7) | 127 (12.2) | 212 (18.7) | 302 (11.3) | 17 996 (21.7) |

| No | 49 726 (68.8) | 4792 (80.2) | 805 (77.2) | 830 (73.1) | 2152 (80.4) | 58 305 (70.2) |

| Missing or unknown | 5852 (8.1) | 489 (8.2) | 111 (10.6) | 94 (8.3) | 224 (8.3) | 6770 (8.1) |

| Problematic drug use | 22 216 (30.8) | 4304 (72.0) | 557 (53.4) | 652 (57.4) | 2219 (82.9) | 29 948 (36.1) |

| Problematic alcohol use | 11 670 (16.2) | 2277 (38.1) | 315 (30.2) | 307 (27) | 1155 (43.1) | 15 724 (18.9) |

| Involuntary index admission | 33 388 (46.2) | 3071 (51.4) | 681 (65.3) | 232 (20.4) | 1323 (49.4) | 38 695 (46.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score (past year of age) | ||||||

| 0 | 69 646 (96.4) | 5767 (96.5) | 1008 (96.6) | 1094 (96.3) | 2556 (95.4) | 80 071 (96.4) |

| 1 | 1264 (1.7) | 60 (1.0) | 18 (1.7) | 19 (1.7) | 23 (0.9) | 1384 (1.7) |

| ≥2 | 1326 (1.8) | 151 (2.5) | 17 (1.6) | 23 (2.0) | 99 (3.7) | 1616 (1.9) |

| Offense conviction history | ||||||

| None | 61 668 (85.4) | 0 | 0 | 40 (3.5) | 77 (2.9) | 61 785 (74.4) |

| Nonviolent offenses only | 4725 (6.5) | 2413 (40.4) | 269 (25.8) | 134 (11.8) | 402 (15.0) | 7943 (9.6) |

| Violent offenses | 5826 (8.1) | 3565 (59.6) | 774 (74.2) | 962 (84.7) | 2199 (82.1) | 13 326 (16.0) |

| Unknown offenses only | 17 (<0.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (<0.0) |

| Died | 10 335 (14.3) | 541 (9.0) | 122 (11.7) | 91 (8.0) | 266 (9.9) | 11 355 (13.7) |

Abbreviation: NS, not shown (due to corresponding number of participants being <5).

Other category not reported separately due to having less than 5 participants in the entire cohort; other included intersex.

Of the entire cohort, 25 824 (31.1%) experienced 1 or more recent criminal sanctions or mental health court diversions during follow up. Of all participants, 8953 (10.8%) were imprisoned and 8083 (9.7%) received mental health court diversion. Of those diverted, 5193 (64.3%) received a community sanction and 2595 (32.1%) were imprisoned before or after diversion.

Cause of Death

A total of 11 355 deaths were recorded (Table 2), of which 5790 were among participants aged less than 65 years and 5565 were among those aged 65 years or older. In those 65 years or older, 5241 deaths (94.2%) were disease-related compared with 3041 deaths (52.5%) in those aged younger than 65 years. In people younger than 65 years, disease-related causes were the leading cause of death in those with no recent criminal sanction (2736 of 4692 deaths [58.3%]) and those with a recent community sanction (173 of 550 deaths [31.5%]), while suicide was the leading cause in those with recent mental health court diversion (64 of 189 deaths [33.9%]) and those currently imprisoned (13 of 25 deaths [52.0%]); accidental drug overdose was the leading cause in those with recent prior imprisonment (151 of 334 deaths [45.2%]).

Table 2. Cause of Death Category by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Deatha.

| Cause of death by age group | Participant deaths by sanction type, No./total No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No sanction | Community | Diversion | Imprisonment | Total | ||

| Current | Prior | |||||

| Age <65 y | ||||||

| Disease-related | 2736/4692 (58.3) | 173/550 (31.5) | 52/189 (27.5) | 8/25 (32.0) | 72/334 (21.6) | 3041/5790 (52.5) |

| Suicide | 1030/4692 (22.0) | 131/550 (23.8) | 64/189 (33.9) | 13/25 (52.0) | 66/334 (19.8) | 1304/5790 (22.5) |

| Accidental drug overdose | 509/4692 (10.8) | 157/550 (28.5) | 43/189 (22.8) | <5 (NS) | 151/334 (45.2) | 862/5790 (14.9) |

| Other external causes | 294/4692 (6.3) | 71/550 (12.9) | 20/189 (10.6) | <5 (NS) | 37/334 (11.1) | 424/5790 (7.3) |

| Undefined or unknown | 123/4692 (2.6) | 18/550 (3.3) | 10/189 (5.3) | 0 | 8/334 (2.4) | 159/5790 (2.7) |

| All external causes | 1833/4692 (39.1) | 359/550 (65.3) | 127/189 (67.2) | 17/25 (68.0) | 254/334 (76.0) | 2590/5790 (44.7) |

| Age ≥65 y | ||||||

| Disease-related | 5221/5540 (94.2) | 10/11 (90.9) | 7/11 (63.6) | <5 (NS) | <5 (NS) | 5241/5565 (94.2) |

| Suicide | 82/5540 (1.5) | 0 | <5 (NS) | 0 | 0 | 85/5565 (1.5) |

| Accidental drug overdose | 37/5540 (0.7) | 0 | <5 (NS) | 0 | 0 | 38/5565 (0.7) |

| Other external causes | 155/5540 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 155/5565 (2.8) |

| Undefined or unknown | 45/5540 (0.8) | <5 (NS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46/5565 (0.8) |

| All external causes | 274/5540 (4.9) | 0 | <5 (NS) | 0 | 0 | 278/5565 (5.0) |

| All ages | ||||||

| Disease-related | 7957/10 232 (77.8) | 183/561 (32.6) | 59/200 (29.5) | 9/26 (34.6) | 74/336 (22.0) | 8282/11 355 (72.9) |

| Suicide | 1112/10 232 (10.9) | 131/561 (23.4) | 67/200 (33.5) | 13/26 (50.0) | 66/336 (19.6) | 1389/11 355 (12.2) |

| Accidental drug overdose | 546/10 232 (5.3) | 157/561 (28.0) | 44/200 (22.0) | <5 (NS) | 151/336 (44.9) | 900/11 355 (7.9) |

| Other external causes | 449/10 232 (4.4) | 71/561 (12.7) | 20/200 (10.0) | <5 (NS) | 37/336 (11.0) | 579/11 355 (5.1) |

| Undefined or unknown | 168/10 232 (1.6) | 19/561 (3.4) | 10/200 (5.0) | 0 | 8/336 (2.4) | 205/11 355 (1.8) |

| All external causes | 2107/10 232 (20.6) | 359/561 (64.0) | 131/200 (65.5) | 17/26 (65.4) | 254/336 (75.6) | 2868/11 355 (25.3) |

Abbreviation: NS, not shown (due to corresponding number of participants being <5).

Data source: Cause of Death Unit Record File held by the New South Wales Ministry of Health Secure Analytics for Population Health Research and Intelligence.

All-Cause and External-Cause Mortality Rates

Age- and sex-specific all-cause mortality rates by recent criminal sanction type in those aged younger than 65 years are presented in eFigure 1 and eTable 5 in Supplement 1. Mortality rates tended to increase with age and be higher in males. In all age groups older than 24 years and younger than 65 years, all-cause mortality rates were highest in those with recent prior imprisonment. In all age groups younger than 65 years, all-cause mortality rates were lowest in those currently imprisoned, followed by those with no recent criminal sanction.

Age- and sex-specific external-cause mortality rates by recent criminal sanction type in those aged younger than 65 years are presented in eFigure 2 and eTable 6 in Supplement 1. External-cause mortality rates were more similar between age groups. In all age groups younger than 55 years, external-cause mortality rates were lowest in those currently imprisoned, followed by those with no recent criminal sanction. In all age groups older than 24 years and younger than 55 years, external-cause mortality rates were highest in those with recent prior imprisonment.

Associations of Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanctions With Mortality

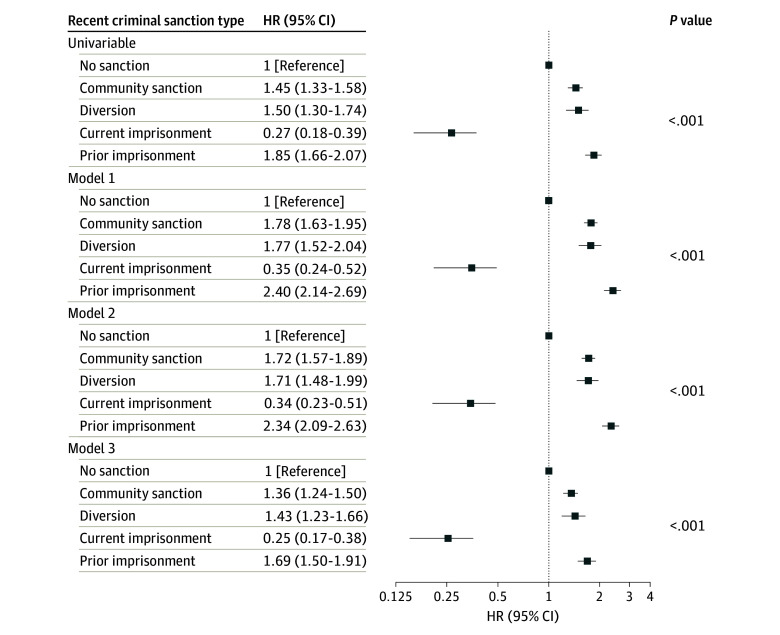

Figure 2 presents hazard ratios (HRs) showing associations of recent criminal sanction type with all-cause mortality in those aged younger than 65 years. In all models, compared with no recent criminal sanction, recent community sanction, mental health court diversion, and prior imprisonment were associated with increased hazards of all-cause mortality, including after adjustment for sociodemographic, health-related, and offense-related confounders. After maximal adjustment, the highest hazard of all-cause mortality was observed for recent prior imprisonment (model 3 adjusted HR [aHR], 1.69; 95% CI, 1.50-1.91), followed by mental health court diversion (aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.23-1.66). Current imprisonment was associated with a lower hazard of all-cause mortality (aHR, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.17-0.38).

Figure 2. All-Cause Mortality by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (N = 74 841).

Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex only. Model 2 was adjusted for model 1 covariates plus Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity, marital status, residential Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage, and residential remoteness. Model 3 was adjusted for model 2 covariates plus history of problematic drug use, history of problematic alcohol use, involuntary index admission, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and offense history. Error bars represent 95% CIs. HR indicates hazard ratio.

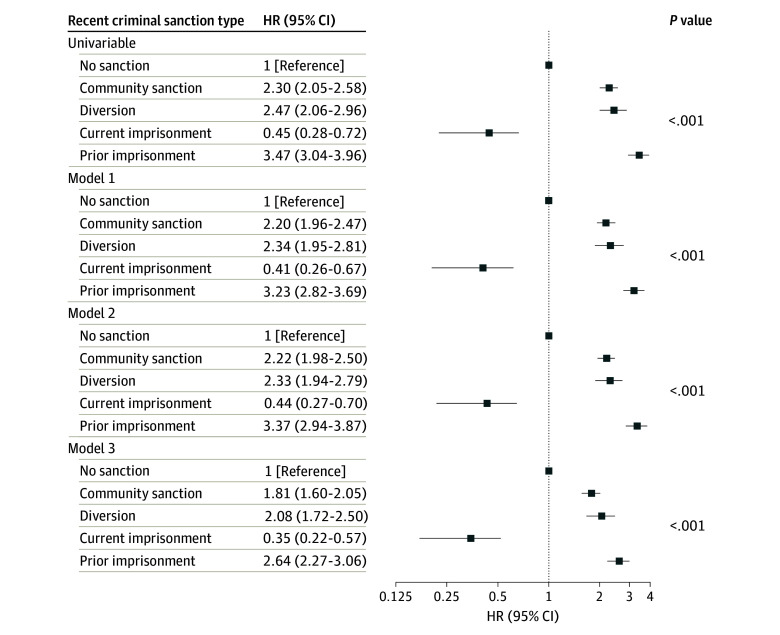

Figure 3 presents HRs for associations of recent criminal sanction types with external-cause mortality in those younger than 65 years. Results were similar to those of all cause mortality, but generally of higher magnitude; all recent criminal sanction types other than current imprisonment were associated with increased hazards of external-cause mortality compared with no recent criminal sanction in all models, while current imprisonment was associated with a reduced hazard. Again, recent prior imprisonment was associated with the highest hazard of external-cause mortality (model 3 aHR, 2.64; 95% CI, 2.27-3.06), followed by mental health court diversion (aHR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.72-2.50). Sex-stratified results were similar to those for both sexes combined (see eTables 7-10 in Supplement 1).

Figure 3. External-Cause Mortality by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (N = 74 841).

Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex only. Model 2 was adjusted for model 1 covariates plus Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity, marital status, residential Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage, and residential remoteness. Model 3 was adjusted for model 2 covariates plus history of problematic drug use, history of problematic alcohol use, involuntary index admission, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, offense history. Error bars represent 95% CIs. HR indicates hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this cohort study of adults hospitalized for psychosis in NSW, almost one-third received a criminal sanction or diversion (excluding for minor traffic offenses), and 1 in 10 were imprisoned. While there is no directly comparable data, this finding appears elevated compared with the NSW community.32 Whereas most deaths in those with no recent criminal sanction were disease-related, external causes—primarily suicide and accidental drug overdose—caused the majority of deaths in those with recent criminal sanctions. Among those aged younger than 65 years, compared with no recent criminal sanction, we found consistent associations of recent (past 2 years) mental health court diversion, community sanctions, and prior imprisonment with increased all-cause and external-cause mortality, independent of sociodemographic and health-related confounders and baseline offense history. To our knowledge, our study is the first among people with psychosis or SMI examining variation in mortality by criminal sanction type, including diversion.

Our findings concur with associations of CLS involvement with mortality documented in broader populations,5,6,21 including NSW,7 and several SMI cohorts.8,9,10,11,12 Unlike some Nordic studies,9,10,11,12,33 our results did not differ by sex, and our findings diverge from a Danish study13 reporting no association of forensic sentencing with mortality; this could be explained by differing mental health and legal systems,14 varying confounder adjustment, and/or baseline mortality differences within each study population. A novel finding of our study is that elevated mortality hazards extended to those receiving mental health court diversion, highlighting the need to consider this group in mortality prevention efforts. The reduced hazard of mortality associated with current imprisonment in our study has been documented in mainstream prison populations,21,22,34 likely reflecting the highly controlled prison environment; however, preventable deaths continue. Most were due to suicide in our study, reinforcing the importance of addressing factors contributing to prison suicide and avoiding imprisonment of people with psychosis.35

Pathways between psychosis, criminalized behavior, criminal sanctions, and mortality are complex and likely influenced by pre-existing factors such as psychosis severity, co-occurring substance use, treatment engagement, and socioeconomic exclusion.36,37 Criminal sanctions can also cause material and psychological harms,36,38,39,40 which may be exacerbated for people with psychosis,3,41 particularly those with intersecting experiences of multilayered discrimination and trauma, including Aboriginal and other racialized people39,41,42,43 and women.39,42 Aboriginal people were overrepresented in our cohort (9.6% vs 3.4% of NSW adults44), and within all criminal sanction categories, reflecting the nexus between adverse mental health outcomes and extreme overincarceration of Aboriginal people in Australia.45 These are recognized as being associated with systemic and institutional racism and colonial policies and practices, including land dispossession, frontier policing, cultural destruction, and forced child removals,45,46 highlighting the need to decolonize service systems and support Aboriginal-controlled responses.47

Despite its therapeutic intent, there are several reasons that mortality may remain elevated following CLS diversion, including the aforementioned pre-existing factors; reliance on mainstream community mental health services, private psychiatrists, and/or primary care clinicians,18 which may have limited resources or experience managing complex forensically involved patients; treatment disengagement48; and failure to address wider health determinants. Diversion may also be perceived punitively49 and engender similar stressors to traditional sanctions, including stigma and fear of imprisonment.36,38

Our results suggest a need for comprehensive cross-sectoral approaches to address overlapping clinical, social, and systemic determinants of CLS involvement and mortality in people with psychosis, particularly due to accidental overdose and suicide, and reduce harms of criminal sanctions. Increased resourcing of general community and specialist forensic mental health services, clarification of optimal models of integration between the two,50 and integrated treatment for co-occurring harmful substance use51 would likely assist. Future research should evaluate mortality, health, and person-centered outcomes associated with different forensic mental health service and legislative approaches and develop effective interventions and care models to optimize health and safety in people with psychosis involved in CLSs. More profoundly, abolition advocates propose a radical reconsideration of justice,39,42 a challenge the medical field must engage with.37,40

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the large population-based sample, time-varying assessment of criminal sanctions, and robust adjustment for confounders including sociodemographic factors, problematic drug and alcohol use, physical comorbidity, and offense history. Limitations include the observational design preventing causal inference and our inability to adjust for all potential confounders, such as individual socioeconomic status and pharmacotherapy. Our exposure classification simplified complex CLS interactions, and we did not examine police contacts, juvenile sanctions, or non–mental health diversion (eg, drug courts). We could not identify exposures, covariates, or deaths occurring interstate, overseas, or before the study period, although we expect these are minor. Finally, linkage and clerical errors may affect any probabilistic data-linkage study; however, the linkage method had a low (<0.5%) false-positive rate, and we excluded participants with suspected linkage error.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of adults with psychosis, CLS involvement was common, with almost 1 in 3 individuals receiving a criminal sanction or diversion. Recent (past 2 years) criminal sanctions, including mental health court diversion, were associated with increased hazards of all-cause and external-cause mortality among those who were not currently imprisoned, compared with no recent sanction. Effective approaches to improving health outcomes among people with psychosis following CLS involvement should be developed.

eAppendix 1. Criteria for Identifying Cases of False-Positive Linkage Error

eAppendix 2. Criteria for Excluding Individual Records due to Administrative Error

eAppendix 3. Further Detail Regarding Section 32 and Section 33 Dismissals

eAppendix 4. Further Detail Regarding Exposure Classification

eAppendix 5. Systematized Nomenclature for Medicine: Clinical Terminology, Australian Release (SNOMED-CT-AU) Codes Used to Identify Problematic Drug and Alcohol Use

eAppendix 6. Further Detail Regarding Covariate and Model Selection

eTable 1. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Study Entry for Participants Aged <65 Years at Entry

eTable 2. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Study Entry for Participants Aged ≥65 Years at Entry

eTable 3. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Last Observation Aged <65 Years

eTable 4. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Last Observation Aged ≥65 Years

eFigure 1. Age- and Sex-Specific All-Cause Mortality Rates Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years by Recent (Past 2-Years) Criminal Sanction Type (n=74,841)

eTable 5. Age- and Sex-Specific All-Cause Mortality Rates by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type

eFigure 2. Age- and Sex-Specific External-Cause Mortality Rates Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type (n=74,841)

eTable 6. Age- and Sex-Specific External-Cause Mortality Rates by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type

eTable 7. All-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Men With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=44,287)

eTable 8. All-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Women With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=30,554)

eTable 9. External-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Men With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=44,287)

eTable 10. External-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Women With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=30,554)

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hjorthøj C, Stürup AE, McGrath JJ, Nordentoft M. Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):295-301. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan JKN, Tong CHY, Wong CSM, Chen EYH, Chang WC. Life expectancy and years of potential life lost in bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;221(3):567-576. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2022.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazel S, Hayes AJ, Bartellas K, Clerici M, Trestman R. Mental health of prisoners: prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(9):871-881. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30142-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee N, Matheson S, Korobanova D, et al. A meta-analysis of the relationship between psychosis and any type of criminal offending, in both men and women. Schizophr Res. 2020;220:16-24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinner SA, Forsyth S, Williams G. Systematic review of record linkage studies of mortality in ex-prisoners: why (good) methods matter. Addiction. 2013;108(1):38-49. doi: 10.1111/add.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrett SE, Craddock C, Gray BJ. Dying whilst on probation: a scoping review of mortality amongst those under community justice supervision. Perspect Public Health. Published online January 31, 2024. doi: 10.1177/17579139231223714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kariminia A, Butler T, Corben S, et al. Extreme cause-specific mortality in a cohort of adult prisoners—1988 to 2002: a data-linkage study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):310-316. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US army soldiers: the army study to assess risk and resilience in service members (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):49-57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazel S, Wolf A, Palm C, Lichtenstein P. Violent crime, suicide, and premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a 38-year total population study in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(1):44-54. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70223-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb RT, Långström N, Runeson B, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S. Violent offending and IQ level as predictors of suicide in schizophrenia: national cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):143-147. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson C, Joas E, Pålsson E, Hawton K, Runeson B, Landén M. Risk factors for suicide in bipolar disorder: a cohort study of 12 850 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):456-463. doi: 10.1111/acps.12946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steingrimsson S, Sigurdsson MI, Gudmundsdottir H, Aspelund T, Magnusson A. Mental disorder, imprisonment and reduced life expectancy—a nationwide psychiatric inpatient cohort study. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2016;26(1):6-17. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhrskov Sørensen L, Bengtson S, Lund J, Ibsen M, Långström N. Mortality among male forensic and non-forensic psychiatric patients: matched cohort study of rates, predictors and causes-of-death. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(7):489-496. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2020.1743753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crocker A, Livingston J, Leclair M. Forensic mental health systems internationally. In: Roesch R, Cook A, eds. Handbook of Forensic Mental Health Services. Routledge; 2017:3-76. doi: 10.4324/9781315627823-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houidi A, Paruk S. A narrative review of international legislation regulating fitness to stand trial and criminal responsibility: is there a perfect system? Int J Law Psychiatry. 2021;74:101666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grøndahl P. Scandinavian forensic psychiatric practices—an overview and evaluation. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(2):92-102. doi: 10.1080/08039480510022927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider RD. Mental health courts and diversion programs: A global survey. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2010;33(4):201-206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.New South Wales Law Reform Commission . Report 135: people with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system—diversion. Published June 2012. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://lawreform.nsw.gov.au/documents/Publications/Reports/Report-135.pdf

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.New South Wales Health Centre for Health Record Linkage . Quality assurance. NSW Health. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.cherel.org.au/quality-assurance

- 21.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK. Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(5):479-487. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham L, Fischbacher CM, Stockton D, Fraser A, Fleming M, Greig K. Understanding extreme mortality among prisoners: a national cohort study in Scotland using data linkage. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(5):879-885. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New South Wales Government . Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 No. 10 (NSW) pt 3. Updated April 3, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2024. https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/html/repealed/current/act-1990-010

- 24.Nelson MA, Lim K, Boyd J, et al. Accuracy of reporting of Aboriginality on administrative health data collections using linked data in NSW, Australia. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):267. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01152-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Technical paper 2033.0.55.001: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), 2011. March 28, 2013. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/22CEDA8038AF7A0DCA257B3B00116E34/$File/2033.0.55.001%20seifa%202011%20technical%20paper.pdf

- 26.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 1270055006C104-statistical local area 2011 to remoteness area 2011. January 21, 2013. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&1270055006_cg_sa2_2011_ra_2011.zip&1270.0.55.006&Data%20Cubes&DD6F47368D7AD64FCA257B03000D95F3&0&July%202011&31.01.2013&Latest

- 27.National Library of Medicine . Unified medical language system: SNOMED CT to ICD-10-CM map. National Institutes of Health. Updated March 1, 2021. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/mapping_projects/snomedct_to_icd10cm.html

- 28.Lamy JB, Venot A, Duclos C. PyMedTermino: an open-source generic API for advanced terminology services. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;210:924-928. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-512-8-924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian and New Zealand standard offence classification (ANZSOC). Published June 2, 2011. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/classifications/australian-and-new-zealand-standard-offence-classification-anzsoc/2011

- 31.VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(3):211-219. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weatherburn D, Ramsey S; Offending over the life course: contact with the NSW criminal justice system between age 10 and age 33. Issue paper no. 132. NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. Published April 2018. Accessed February 21, 2024. https://www.bocsar.nsw.gov.au/Publications/BB/2018-Report-Offending-over-the-life-course-BB132.pdf

- 33.Steingrimsson S, Sigurdsson MI, Gudmundsdottir H, Aspelund T, Magnusson A. A total population-based cohort study of female psychiatric inpatients who have served a prison sentence. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2015;25(3):220-225. doi: 10.1002/cbm.1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen DL, Wohl DA, Schoenbach VJ. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among Black and White North Carolina state prisoners, 1995-2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(10):719-726. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe . Trenčín statement on prisons and mental health. World Health Organization. Published October 18, 2007. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/108575/Intl-mtg-prison-health-Tren%c4%8d%c3%adn-statm-2008-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 36.Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health Justice. Published online October 24, 2013. doi: 10.1186/2194-7899-1-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conner C, Mitchell C, Jahn J; End Police Violence Collective . Advancing public health interventions to address the harms of the carceral system: a policy statement adopted by the American Public Health Association, October 2021. Med Care. 2022;60(9):645-647. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durnescu I. Pains of probation: effective practice and human rights. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2011;55(4):530-545. doi: 10.1177/0306624X10369489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilroy D, Lean T. Making visible the invisibalised voices of criminalised women in Australia. In: Masson I, Booth N, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Women’s Experiences of Criminal Justice. Routledge; 2022:149-161. doi: 10.4324/9781003202295-14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reinhart E. Reconstructive justice—public health policy to end mass incarceration. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(6):559-564. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2208239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra S, Etkins OS, Yang LH, Williams DR. Structural racism and inequities in incidence, course of illness, and treatment of psychotic disorders among Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(4):624-632. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis A. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ware S, Ruzsa J, Dias G. It can’t be fixed because it’s not broken: racism and disability in the prison industrial complex. In: Ben-Moshe L, Chapman C, Carey AC, eds. Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada. Springer; 2014:163-184. doi: 10.1057/9781137388476_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Census of population and housing—counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Published August 31, 2022. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/census-population-and-housing-counts-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/latest-release

- 45.Milroy H, Watson M, Kashyap S, Dudgeon P. First Nations peoples and the law. Australian Bar Review. Published 2021. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.lexisnexis.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/513604/037fefea242f92e933c6e8a226895f0a81c28ee4.pdf

- 46.Johnston E. Royal commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody: national report volume 1. Government of Australia. April 15, 1991. Accessed May 31, 2024. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic/national/vol1/

- 47.Kendall S, Lighton S, Sherwood J, Baldry E, Sullivan EA. Incarcerated Aboriginal women’s experiences of accessing healthcare and the limitations of the ‘equal treatment’ principle. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1155-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marr C, Singh S, Gaskin C, Kasinathan J, Lloyd T, Dean K. Patterns of mental health service contacts for young people deemed eligible for court diversion. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2024;23(3):204-216. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2023.2276961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preston AG, Rosenberg A, Schlesinger P, Blankenship KM. “I was reaching out for help and they did not help me”: Mental healthcare in the carceral state. Health Justice. 2022;10(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s40352-022-00183-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malik N, Mohan R, Fahy T. Community forensic psychiatry. Psychiatry. 2007;6(10):415-419. doi: 10.1016/j.mppsy.2007.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fantuzzi C, Mezzina R. Dual diagnosis: a systematic review of the organization of community health services. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(3):300-310. doi: 10.1177/0020764019899975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Criteria for Identifying Cases of False-Positive Linkage Error

eAppendix 2. Criteria for Excluding Individual Records due to Administrative Error

eAppendix 3. Further Detail Regarding Section 32 and Section 33 Dismissals

eAppendix 4. Further Detail Regarding Exposure Classification

eAppendix 5. Systematized Nomenclature for Medicine: Clinical Terminology, Australian Release (SNOMED-CT-AU) Codes Used to Identify Problematic Drug and Alcohol Use

eAppendix 6. Further Detail Regarding Covariate and Model Selection

eTable 1. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Study Entry for Participants Aged <65 Years at Entry

eTable 2. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Study Entry for Participants Aged ≥65 Years at Entry

eTable 3. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Last Observation Aged <65 Years

eTable 4. Participant Characteristics by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type at Last Observation Aged ≥65 Years

eFigure 1. Age- and Sex-Specific All-Cause Mortality Rates Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years by Recent (Past 2-Years) Criminal Sanction Type (n=74,841)

eTable 5. Age- and Sex-Specific All-Cause Mortality Rates by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type

eFigure 2. Age- and Sex-Specific External-Cause Mortality Rates Among People With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type (n=74,841)

eTable 6. Age- and Sex-Specific External-Cause Mortality Rates by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type

eTable 7. All-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Men With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=44,287)

eTable 8. All-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Women With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=30,554)

eTable 9. External-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Men With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=44,287)

eTable 10. External-Cause Mortality Hazard Ratios by Recent (Past 2 Years) Criminal Sanction Type Among Women With Psychosis Aged 18 to 64 Years (n=30,554)

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement