Abstract

Previous studies have implicated hindbrain oxytocin (OT) receptors in the control of food intake and brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis. We recently demonstrated that hindbrain [fourth ventricle (4V)] administration of oxytocin (OT) could be used as an adjunct to drugs that directly target beta-3 adrenergic receptors (β3-AR) to elicit weight loss in diet-induced obese (DIO) rodents. What remains unclear is whether systemic OT can be used as an adjunct with the β3-AR agonist, CL 316243, to increase BAT thermogenesis and elicit weight loss in DIO rats. We hypothesized that systemic OT and β3-AR agonist (CL 316243) treatment would produce an additive effect to reduce body weight and adiposity in DIO rats by decreasing food intake and stimulating BAT thermogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effects of systemic (subcutaneous) infusions of OT (50 nmol/day) or vehicle (VEH) when combined with daily systemic (intraperitoneal) injections of CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or VEH on body weight, adiposity, food intake and brown adipose tissue temperature (TIBAT). OT and CL 316243 monotherapy decreased body weight by 8.0±0.9% (P<0.05) and 8.6±0.6% (P<0.05), respectively, but OT in combination with CL 316243 produced more substantial weight loss (14.9±1.0%; P<0.05) compared to either treatment alone. These effects were associated with decreased adiposity, energy intake and elevated TIBAT during the treatment period. The findings from the current study suggest that the effects of systemic OT and CL 316243 to elicit weight loss are additive and appear to be driven primarily by OT-elicited changes in food intake and CL 316243-elicited increases in BAT thermogenesis.

Keywords: Obesity, brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, food intake, oxytocin

Introduction

The obesity epidemic and its associated complications, increase the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and COVID-19 [1; 2]. Many of the monotherapies to treat obesity are of limited effectiveness, associated with adverse and/or unwanted side effects (i.e. diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, sleep disturbance and depression) and/or are poorly tolerated. Improvements have been made in monotherapies to treat obesity, particularly within the family of drugs that target the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R). While the FDA recently approved the use of the long-acting and highly effective GLP-1R agonist, semaglutide [3], it can also be associated with mild to moderate gastrointestinal (GI) side effects [3; 4], thus highlighting the need for continued optimization of existing treatments.

Recent studies suggest that combination therapy (co-administration of different compounds) and monomeric therapy (dual or triple agonists in single molecule) are more effective than monotherapy for prolonged weight loss [5; 6]. Marked weight loss has been reported in long-term (20 weeks to ≥ 1 year) clinical studies in humans treated with the amylin analogue, cagrilintide, and semaglutide (≈ 15.6 to 17.1% of initial body weight [7; 8]) and the FDA-approved drug, Qsymia (topiramate + phentermine) (≈ 10.9% of initial body weight; [9]). Alternatively, the monomeric compound, tirzepatide (Zepbound™), targets both GLP-1R and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), and was recently reported to elicit 20.9% and 25.3% weight loss in humans with obesity over 72- [10] and 88-week trials [11]. In addition, retatrutide, a triple-agonist that targets GIP, glucagon receptors (GCGR) and GLP-1R was reported to reduce body weight by 24.2% over a 48-week trial [12]. Despite the considerable improvements that have been made with respect to weight loss, these treatments are still associated with adverse GI side effects [10], leading, in some cases, to the discontinuation of the drug in up to 7.1% of participants [10].

While the hypothalamic neuropeptide, oxytocin (OT) is largely associated with reproductive behavior [13], recent studies implicate an important role for OT in the regulation of body weight [14; 15; 16; 17]. Studies to date indicate that OT elicits weight loss, in part, by reducing food intake and increasing lipolysis [18; 19; 20] and energy expenditure [18; 21; 22; 23]. While OT is effective at evoking prolonged weight loss in DIO rodents [19; 22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27; 28] and nonhuman primates [18], its overall effectiveness as a monotherapy to treat obesity is relatively modest following 4–8 week treatments in DIO mice (≈4.9%) [28], rats (≈8.7%) [28] and rhesus monkeys (≈3.3%) [18] thus making it more suited as a combination therapy with other drugs that work through other mechanisms. Head and colleagues recently reported that systemic OT and the opioid antagonist, naltrexone, resulted in an enhanced reduction of high-fat, high-sugar meal in rats [29]. Recently, we found that hindbrain (fourth ventricle; 4V) OT treatment in combination with systemic treatment with CL-316243, a drug that directly targets beta-3 adrenergic receptors (β3-AR) to increase BAT thermogenesis [28; 30; 31; 32; 33], resulted in greater weight loss (15.5 ± 1.2% weight loss) than either OT (7.8 ± 1.3% weight loss) or CL 316243 (9.1 ± 2.1% weight loss) alone [34].

The goal of the current study was to test if systemic OT treatment could be used as an adjunct with the β3-AR agonist, CL 316243, to increase BAT thermogenesis and elicit weight loss in DIO rats when using a more translational route of administration for OT delivery. We hypothesized that systemic OT and β3-AR agonist (CL 316243) treatment would produce an additive effect to reduce body weight and adiposity in DIO rats by decreasing food intake and stimulating BAT thermogenesis. To test this, we determined the effects of systemic (subcutaneous) infusions of OT (50 nmol/day) or vehicle (VEH) when combined with daily systemic (intraperitoneal) injections of CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or VEH on body weight, adiposity, food intake, brown adipose tissue temperature (TIBAT) and thermogenic gene expression.

Methods

Animals

Adult male Long-Evans rats [~ 8–9 weeks old, 292–349 grams at start of high fat dietary (HFD) intervention/~ 8–10 months old, 526–929 g body weight at study onset] were initially obtained from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained for at least 4 months on a high fat diet (HFD) prior to study onset. All animals were housed individually in Plexiglas cages in a temperature-controlled room (22±2°C) under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. All rats were maintained on a 1 a.m./1 p.m. light cycle. Rats had ad libitum access to water and a HFD providing 60% kcal from fat (approximately 6.8% kcal from sucrose and 8.9% of the diet from sucrose) (Research Diets, D12492, New Brunswick, NJ). The research protocols were approved both by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) and the University of Washington in accordance with NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NAS, 2011) [35].

Drug Preparation

Fresh solutions of OT acetate salt (Bachem Americas, Inc., Torrance, CA) were solubilized in sterile water and subsequently primed in sterile 0.9% saline at 37° C for approximately 40 hours prior to minipump implantation based on manufacturer’s recommended priming instructions for ALZET® model 2004 minipumps. CL 316243 (Tocris/Bio-Techne Corporation, Minneapolis, MN) was solubilized in sterile water each day of each experiment.

Subcutaneous implantations of osmotic minipumps

Animals were implanted with an osmotic minipump (model 2004, DURECT Corporation Cupertino, CA) one week prior to CL 316343 treatment as previously described [34].

Implantation of temperature transponders underneath IBAT

Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane prior to having the dorsal surface along the upper midline of the back shaved and scrubbed with 70% ethanol followed by betadine swabs as previously described [28]. Following an incision (1 “) along the midline of the interscapular area a temperature transponder (14 mm long/2 mm wide) (HTEC IPTT-300; Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc., Seaford, DE) was implanted underneath the left IBAT pad as previously described [28; 36; 37]. The transponder was subsequently secured in place by suturing it to the brown fat pad with sterile silk suture. The interscapular incision was closed with Nylon sutures (5–0), which were removed in awake animals approximately 10–14 days post-surgery. HTEC IPTT-300 transponders were used in place of IPTT-300 transponders to enhance accuracy in our measurements as previously described [28].

Acute IP injections and measurements of TIBAT

CL 316243 (or saline vehicle; 0.1 ml/kg injection volume) was administered immediately prior to the start of the dark cycle following 4 hours of food deprivation. Animals remained without access to food for an additional 1 (Study 2–3) or 4 h (Study 1) during the course of the TIBAT measurements. A handheld reader (DAS-8007-IUS Reader System; Bio Medic Data Systems, Inc.) was used to collect measurements of TIBAT.

Body Composition

Determinations of lean body mass and fat mass were made on un-anesthetized rats by quantitative magnetic resonance using an EchoMRI 4-in-1–700™ instrument (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX) at the VAPSHCS Rodent Metabolic Phenotyping Core. Measurements were taken prior to 4V cannulations and minipump implantations as well as at the end of the infusion period.

Study Protocols

Study 1: Determine the dose-response effects of systemic (SC) infusion of OT (16 and 50 nmol/day) on body weight, adiposity and energy intake in DIO rats.

Rats were fed ad libitum and maintained on HFD for approximately 5.5 months prior to prior to being implanted with a temperature transponder underneath the left IBAT depot. Rats were subsequently maintained on a daily 4-h fast and received minipumps to infuse vehicle or OT (16 or 50 nmol/day) over 29 days. These doses was selected based on a dose of OT found to be effective at reducing body weight when administered subcutaneously [19] or into the 4V [38] of DIO rats. Daily food intake and body weight were also tracked for 29 days.

Study 2: Effect of chronic 4V OT infusions (16 nmol/day) and systemic beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 31643) administration (0.5 mg/kg) on body weight, body adiposity, energy intake and TIBAT in male DIO rats.

Rats (~ 10 mo old; 526–929 g at start of study) were fed ad libitum and maintained on HFD for approximately 7.5 months prior to receiving implantations of temperature transponders underneath the left IBAT pad in addition to 4V cannulas and 28-day minipumps to infuse vehicle or OT (16 nmol/day) over 28 days, respectively. After having matched animals for OT-elicited reductions in body weight (infusion day 7), DIO rats subsequently received 1x daily IP injections of VEH or CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg). We selected this dose because it elevated TIBAT at doses that failed to produce elevations in heart rate in lean rats [39]. In addition, this dose produced comparable weight loss to that of OT alone in Study 2. TIBAT was measured daily at baseline (−4 h; 9:00 a.m.), immediately prior to IP injections (0 h; 12:45–1:00 p.m.), and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 20 and 24-h post-injection. In addition, daily food intake and body weight were also tracked for 28 days. Data from animals that received the single dose of CL-31643 were analyzed over the 28-day infusion period.

Adipose tissue processing for adipocyte size and UCP-1 analysis

IWAT and EWAT depots were collected at the end of the infusion period in rats from Study 2. Rats from each group were euthanized following a 3-h fast. Rats were euthanized with intraperitoneal injections of ketamine cocktail [ketamine hydrochloride (214.3 mg/kg), xylazine (10.71 mg/kg) and acepromazine (3.3 mg/kg) in an injection volume up to 2 mL/rat] and transcardially exsanguinated with PBS followed by perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS. Adipose tissue (IBAT, IWAT, and EWAT) was dissected and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 24 h and then placed in 70% ethanol (EtOH) prior to paraffin embedding. Sections (5 μm) sampled were obtained using a rotary microtome, slide-mounted using a floatation water bath (37°C), and baked for 30 min at 60°C to give approximately 15–16 slides/fat depot with two sections/slide.

Adipocyte size analysis and UCP-1 staining

Adipocyte size analysis was performed on deparaffinized and digitized IWAT and EWAT sections. The average cell area from two randomized photomicrographs was determined using the built-in particle counting method of ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Fixed (4% PFA), paraffin-embedded adipose tissue was sectioned and stained with a primary rabbit anti-UCP-1 antibody (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA (#ab10983/RRID: AB_2241462)] as has been previously described in lean C57BL/6J mice [40] and both lean and DIO C57BL/6 mice after having been screened in both IBAT and IWAT of Ucp1+/− and Ucp1−/− mice [41]. Immunostaining specificity controls included omission of the primary antibody and replacement of the primary antibody with normal rabbit serum at the same dilution as the respective primary antibody. Area quantification for UCP1 staining was performed on digital images of immunostained tissue sections using image analysis software (Image Pro Plus software, Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). Slides were visualized using bright field on an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus Corporation of the Americas; Center Valley, PA) and photographed using a Canon EOS 5D SR DSLR (Canon U.S.A., Inc., Melville, NY) camera at 100X magnification. Values for each tissue within a treatment were averaged to obtain the mean of the treatment group.

Blood collection

Blood was collected from 4-h (Study 1) or 6-h fasted rats (Study 2) within a 2-h window towards the end of the light cycle (10:00 a.m.−12:00 p.m.) as previously described in DIO CD® IGS rats and mice [24; 28]. Animals from Study 2 were euthanized at 2-h post-CL 316243 or VEH treatment. Treatment groups were counterbalanced at time of euthanasia to avoid time of day bias. Blood samples [up to 3 mL] were collected immediately prior to transcardial perfusion by cardiac puncture in chilled K2 EDTA Microtainer Tubes (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Whole blood was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 1.5-min at 4°C; plasma was removed, aliquoted and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis.

Plasma hormone measurements

Plasma leptin and insulin were measured using electrochemiluminescence detection [Meso Scale Discovery (MSD®), Rockville, MD] using established procedures [28; 42]. Intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) for leptin was 2.7% and 3.2% for insulin. The range of detectability for the leptin assay is 0.137–100 ng/mL and 0.069–50 ng/mL for insulin. Plasma fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF-21) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and irisin (AdipoGen, San Diego, CA) levels were determined by ELISA. The intra-assay CV for FGF-21 and irisin were 4.5% and 8.4%, respectively; the ranges of detectability were 31.3–2000 pg/mL (FGF-21) and 0.078–5 μg/mL (irisin). Plasma adiponectin was also measured using electrochemiluminescence detection Meso Scale Discovery (MSD®), Rockville, MD] using established procedures [28; 42]. Intra-assay CV for adiponectin was 1.1%. The range of detectability for the adiponectin assay is 2.8–178 ng/mL. The data were normalized to historical values using a pooled plasma quality control sample that was assayed in each plate.

Blood glucose and lipid measurements

Blood was collected for glucose measurements by tail vein nick following a 4 (Study 1) or 6-h fast (Study 2) and measured with a glucometer using the AlphaTRAK 2 blood glucose monitoring system (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) [43]. Tail vein glucose was measured at 2-h post-CL 316243 or VEH treatment (Study 2). Total cholesterol (TC) [Fisher Diagnostics (Middletown, VA)] and free fatty acids (FFAs) [Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA)] were measured using an enzymatic-based kits. Intra-assay CVs for TC and FFAs were 1.4 and 2.3%, respectively. These assay procedures have been validated for rodents [44].

Tissue collection for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

IBAT and IWAT tissue was collected from 4 (Study 1) or 6-h fasted rats (Study 2). In addition, animals from Study 2 were euthanized at 2-h post-CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or VEH administration. IBAT and IWAT were collected within a 2-h window towards the end of the light cycle (10:00 a.m.−12:00 p.m.) as previously described in DIO CD® IGS/Long-Evans rats and C57BL/6J mice [24; 28; 38]. Tissue was rapidly removed, wrapped in foil and frozen in liquid N2. Samples were stored frozen at −80°C until analysis.

qPCR

RNA extracted from samples of IBAT and IWAT (Studies 1–2) were analyzed using the RNeasy Lipid Mini Kit (Qiagen Sciences Inc, Germantown, MD) followed by reverse transcription into cDNA using a high-capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative analysis for relative levels of mRNA in the RNA extracts was measured in duplicate by qPCR on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and normalized to the cycle threshold value of Nono mRNA in each sample. The TaqMan® probes used in the study were Thermo Fisher Scientific Gene Expression Assay probes. The probe for rat Nono (Rn01418995_g1), UCP-1 (Ucp1; catalog no. Rn00562126_m1), beta 1 adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) (Adrb1; catalog no. Rn00824536_s1), β3-AR (Adrb3; catalog no. Rn01478698_g1), type 2 deiodinase (D2) (Dio2; catalog no. Rn00581867_m1), G-protein coupled receptor 120 (Gpr120; catalog no. Rn01759772_m1), cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor α-like effector A (Cidea; catalog no. Rn04181355_m1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (Ppargc1a; catalog no. Rn00580241_m1) and PR domain containing 16 (Prdm16; catalog no. Rn01516224_m1) were acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Relative amounts of target mRNA were determined using the Comparative CT or 2-ΔΔCT method [45] following adjustment for the housekeeping gene. Specific mRNA levels of all genes of interest were normalized to the cycle threshold value of Nono mRNA in each sample and expressed as changes normalized to controls (vehicle/vehicle treatment).

Transponder placement

All temperature transponders were confirmed to have remained underneath the IBAT depot at the conclusion of the study.

Statistical Analyses

All results are expressed as means ± SE. Comparisons between multiple groups involving between subjects designs were made using one- or two-way ANOVA as appropriate, followed by a post-hoc Fisher’s least significant difference test. Comparisons involving within-subjects designs were made using a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Bonferroni Test. Analyses were performed using the statistical program SYSTAT (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). Differences were considered significant at P<0.05, 2-tailed.

Results

Study 1: Determine the dose-response effects of systemic (SC) infusion of OT (16 and 50 nmol/day) on body weight, adiposity and energy intake in DIO rats

Prior to treatment, groups were matched for body weight and adiposity (vehicle: 749±50 grams; OT (16 nmol/day): 763.6±37.6 grams/42±2.6% fat; OT (50 nmol/day): 759±45.4 grams/39.2±1.6%. There was no difference in body weight [(F(2,17) = 0.027, P=NS)] or percent adiposity [(F(2,17) = 0.003, P=NS)] between groups prior to treatment onset. As expected, body weight of DIO rats remained stable over the month of vehicle treatment relative to pre-treatment [(F(1,5) = 2.865, P=0.151)] (Figure 1A). In contrast to vehicle treatment, systemic OT (16 nmol/day) resulted in a significant reduction of body weight relative to OT pre-treatment [(F(1,6) = 140.799, P<0.01)] (Figure 1A; P<0.05). Furthermore, SC OT, at a 3-fold higher dose (50 nmol/day), also resulted in a significant elevation of body weight relative to pre-treatment [(F(1,6) = 47.271, P<0.01)].

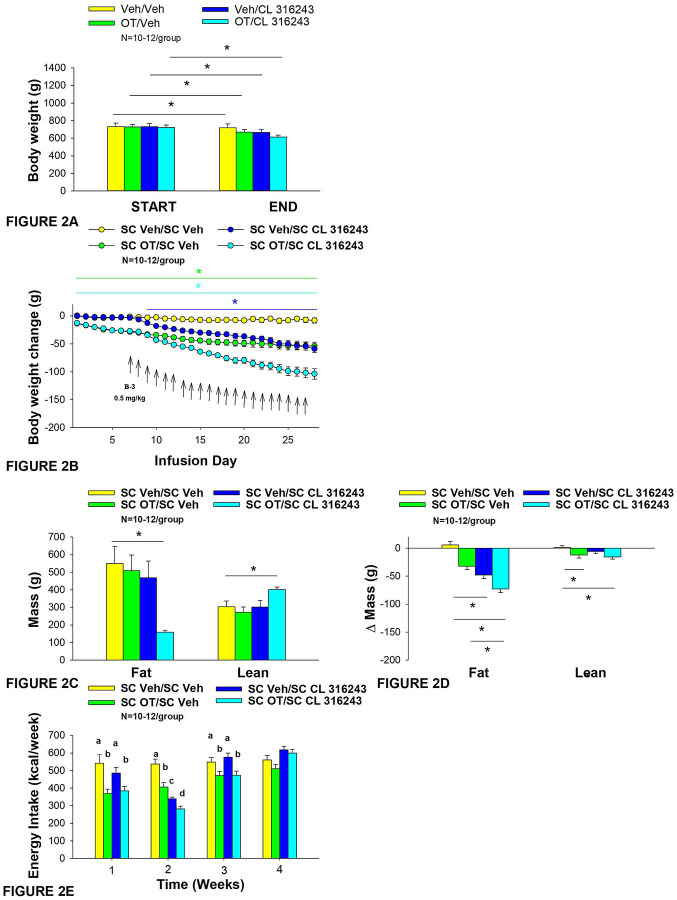

Figure 1A-D: Determine the dose-response effects of systemic (SC) infusion of OT (16 and 50 nmol/day) on body weight, adiposity and energy intake in DIO rats.

A, Rats were maintained on HFD (60% kcal from fat; N=6–7/group) for approximately 5.5 months prior to being implanted with temperature transponders and allowed to recover for 1–2 weeks prior to being implanted with subcutaneous minipumps. A, Effect of chronic subcutaneous OT or vehicle on body weight in DIO rats; B, Effect of chronic subcutaneous OT or vehicle on body weight change in DIO rats; C, Effect of chronic subcutaneous OT or vehicle on adiposity in DIO rats; D, Effect of chronic subcutaneous OT or vehicle on adiposity in DIO rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, †0.05<P<0.1 OT vs. vehicle.

In addition, SC OT (16 and 50 nmol/day) was able to reduce weight gain (Figure 1B) relative to vehicle treatment throughout the 28-day infusion period. SC OT (50 nmol/day), at a dose that was at least 3-fold higher than the centrally effective dose (16 nmol/day), reduced weight gain throughout the entire 28-day infusion period. SC OT (16 nmol/day) treated rats had reduced weight gain between days 2–29 (P<0.05) while SC OT (50 nmol/day) reduced weight gain between days 1–29 (P<0.05). There was an overall effect of OT to reduce relative fat mass (pre- vs post-intervention) [(F(2,17) = 6.052, P=0.010)]. SC OT (50 nmol/day) reduced fat mass (P<0.05) and there was also a tendency for the lower dose (16 nmol/day) to reduce relative fat mass (P=0.066) (Figure 1C; P<0.05).

There was also an overall effect of OT to reduce relative lean mass (pre- vs post-intervention) [(F(2,17) = 5.572, P=0.014)]. Specifically, SC OT (16 nmol/day) reduced relative lean mass at the lower dose (16 nmol/day; P<0.01) while the higher dose (50 nmol/day) tended to reduce relative lean mass (P=0.090). Note that there was no significant reduction in total fat mass or lean mass (P=NS).

The changes in body weight and relative fat mass were not associated with any changes in plasma leptin, insulin, glucose or total cholesterol (Table 1). These effects that were mediated, at least in part, by a modest reduction of energy intake that was apparent during weeks 1 (50 nmol/day) and 2 (16 and 50 nmol/day) of OT treatment (Figure 1D; P<0.05).

Table 1.

Plasma measurements following systemic (SC) infusions of OT (16 and 50 nmol/day) or vehicle DIO rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 OT vs. vehicle (N=6–7/group).

| SC | VEH | OT (16 nmol/day) | OT (50 nmol/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 65.9 ± 7.8a | 71.3 ± 8.2a | 59.6 ± 7.7a |

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 4.7 ± 1.7a | 3.4 ± 0.9a | 4.7 ± 1.3a |

| Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | 137.3± 4.5a | 160.4 ± 8.3b | 157.7 ± 7.3ab |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 194.6 ± 5.7a | 202.2 ± 8.0a | 205 ± 12.5a |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 108.1 ± 10.4a | 118.4 ± 13.4a | 105.5 ± 11.5a |

Different letters denote significant differences between treatments

Shared letters are not significantly different from one another

N=6–7/group

Study 2: Effect of chronic 4V OT infusions (16 nmol/day) and systemic β3-AR agonist (CL 31643) administration (0.5 mg/kg) on body weight, body adiposity and energy intake in male DIO rats.

The goal of this study was to determine the effects of chronic OT treatment in combination with a single dose (identified in Study 1) of the β3-AR agonist, CL 316243, on body weight and adiposity in DIO rats. By design, DIO rats were obese as determined by both body weight (804±14 g) and adiposity (310±11 g fat mass; 38.3±4.7% adiposity) after maintenance on the HFD for approximately 7 months months. Prior to the onset of CL 316243 treatment on infusion day 7, both OT treatment groups were matched for OT-elicited reductions of weight gain.

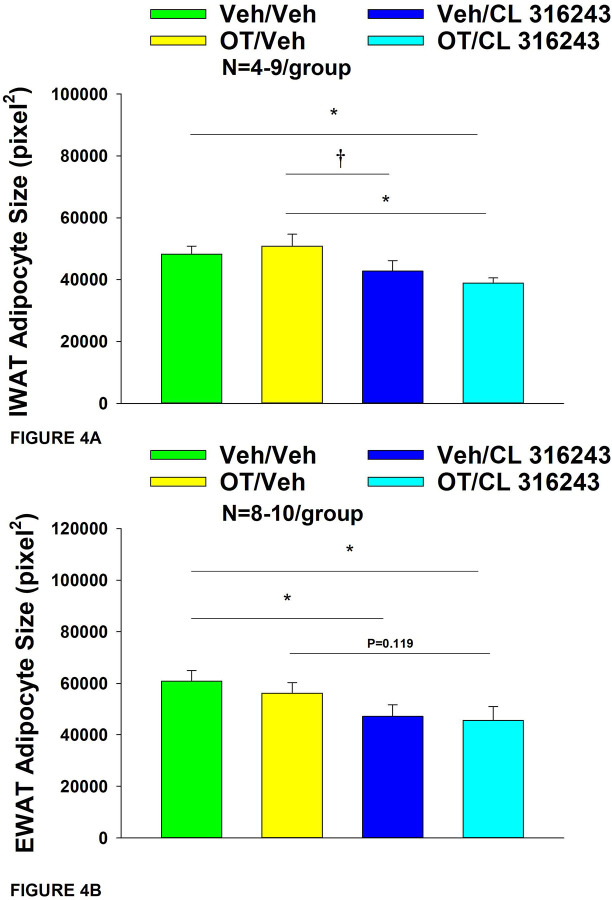

OT and CL 316243 alone reduced body weight by ≈ 7.8±1.3% (P<0.05) and 9.1±2.3% (P<0.05), respectively, but the combined treatment produced more pronounced weight loss (pre- vs post-intervention) (15.5±1.2%; P<0.05) (Figure 2A) than either treatment alone (P<0.05). OT alone tended to reduce weight gain on days 16–28 (0.05<P<0.1) while CL 316243 alone tended to reduce or reduced weight gain on day 24 (0.05<P<0.1), day 25 (P=0.05), and days 26–28 (P<0.05) (Figure 2B). OT and CL 316243 together tended to reduce weight gain on day 9 (0.05<P<0.1) reduced weight gain on days 10–28 (P<0.05). The combination treatment appeared to produce a more pronounced reduction of weight gain relative to OT alone on day 25 (0.05<P<0.1) and this reached significance on days 26–28 (P<0.05).

Figure 2A-E: Effect of chronic 4V OT infusions (16 nmol/day) and systemic beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 31643) administration (0.5 mg/kg) on body weight, body adiposity and energy intake in male DIO rats.

Ad libitum fed rats were either maintained on HFD (60% kcal from fat; N=8–10/group) for approximately 8 months prior to receiving continuous infusions of vehicle or OT (16 nmol/day) in combination with a single dose of CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg). A, Change in body weight in HFD-fed DIO rats; B, Change in body weight gain in HFD-fed DIO rats; C, Change in fat mass and lean mass in HFD-fed DIO rats; D, Change in relative fat mass and lean mass in HFD-fed DIO rats; E, Weekly energy intake (kcal/week) in HFD-fed DIO rats. ↑ indicate 1x daily injections. Different letters denote significant differences between treatments B, Colored bars represent specific group comparisons vs vehicle. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P=0.05, †0.05<P<0.1 vs. vehicle or baseline (pre-treatment; Fig. 3A).

In addition, the combination treatment tended to produce a greater reduction of weight gain relative to CL 316243 alone on days 21–22 and 26–28 (0.05<P<0.1). While OT alone did not significantly reduce fat mass (P=NS), there was a tendency for CL 316243 alone (0.05<P<0.1), and the combination of OT and CL 316243 (P<0.05) to reduce fat mass without impacting lean body mass (Figure 2C; P=NS). However, the combination treatment did not result in a significant reduction of fat mass relative to OT alone or CL 316243 alone (P=NS). Consistent with these effects, OT alone did not produce a reduction in relative fat mass (P=0.108) while CL 316243 alone reduced relative fat mass (pre- vs post-intervention; P<0.05) without changing lean mass (Figure 2D; P=NS). The combination treatment produced a significant reduction of relative fat mass (pre- vs post-intervention; P<0.05) which exceeded that of OT alone (P<0.05) but not CL 316243 alone (P=NS). OT, CL 316243 and the combined treatment were all effective at reducing energy intake at week 2 (Figure 2E; P<0.05) with no difference between treatments (P=NS). All treatments were ineffective at reducing energy intake over weeks 3 and 4 (P=NS).

Two-way ANOVA revealed an overall significant effect of OT [(F(1,39) = 63.434, P<0.01)], CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 74.939, P<0.01)] but no significant interactive effect between OT and CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 0.058, P=NS)] on weight loss. Consistent with this finding, two-way ANOVA revealed consistent overall effects of OT and CL-3162343 on reduction of body weight gain between days 10–29 but no significant overall effect. In addition, two-way ANOVA revealed an overall significant effect of OT [(F(1,39) = 4.989, P=0.031)], CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 7.607, P=0.009)] and a near significant interactive effect between OT and CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 2.945, P=0.094)] on fat mass. There was no significant overall effect of OT [(F(1,39) = 1.351, P=NS)], on lean mass but there was an overall effect of CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 4.829, P=0.034)], and an interactive effect of OT and CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 4.905, P=0.033)] on lean mass.

Lastly, two-way ANOVA revealed an overall significant effect of OT [(F(1,39) = 21.464, P<0.01)], CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 62.681, P<0.01)] and a near significant interactive effect between OT and CL 316243 [(F(1,39) = 3.190, P=0.082)] on energy intake (week 2).

Overall, these findings suggest an additive effect of OT and CL 316243 to produce sustained weight loss in DIO rats. The effects of the combination treatment on adiposity and energy intake appear to be driven largely by CL 316243 and OT, respectively.

CL 316243 elevated TIBAT on injection day 1 at 0.5, 0.75 and 1-h post-injection (P<0.05; Table 2A) and tended to elevate TIBAT at 0.25-h post-injection (0.05<P<0.1). Similarly, CL 316243, when given in combination with OT, also increased TIBAT at 0.5, 0.75 and 1-h post-injection and tended to elevate TIBAT at 0.25-h post-injection on injection day 1 (0.05<P<0.1). Both CL 316243 and CL 316243 + OT treatments elevated TIBAT relative to vehicle treated animals when the TIBAT data from injection day 1 were averaged over 1-h post-injection (TIBATP<0.05). There was no significant difference in TIBAT response to CL 316243 CL 316243 + OT treatments when the TIBAT data were averaged over 60 min (P=NS).

Table 2A-C.

TIBAT measurements following acute systemic administration of the beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 316243) or vehicle in male DIO rats. A, injection day 1 (0.5 mg/kg) and B, injection day 22 (0.5 mg/kg). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs VEH; †0.05<P<0.1 vs VEH.

| Table 2A. Changes in TIBAT Following Systemic OT +/− CL 316243 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment in Male DIO Rats (Injection Day 1) | ||||||

| SC | IP | 0 min | 15 min | 30 min | 45 min | 60 min |

| Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | ||

| VEH | VEH | 37.1±.0.4 | 37.3±.0.8 | 37.7±.0.3 | 37.5±.0.3 | 37.4±.0.3 |

| VEH | CL 316243 | 36.8±.0.2 | 38.3±.0.2† | 38.6±.0.2* | 38.5±.0.2* | 38.5±.0.2* |

| OT | VEH | 36.6±.0.3 | 37.7±.0.2 | 37.3±.0.2 | 37.3±.0.2 | 37.0±.0.2 |

| OT | CL 316243 | 36.6±.0.2 | 38.2±.0.2† | 38.4±.02* | 38.3±.0.2* | 38.1±.0.1* |

| *P<0.05 vs VEH | ||||||

| N=8–12/group | ||||||

| Table 2B. Changes in TIBAT Following Systemic OT +/− CL 316243 | ||||||

| Treatment in Male DIO Rats (Injection Dav 22) | ||||||

| SC | IP | 0 min | 15 min | 30 min | 45 min | 60 min |

| Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | ||

| VEH | VEH | 36.5±.0.3 | 37.7±.0.2 | 37.1±.0.3 | 37.0±.0.2 | 37.1±.0.3 |

| VEH | CL 316243 | 36.8±.0.2 | 38.5±.0.2* | 38.3±.0.2* | 38.2±.0.2* | 38.1±.0.2* |

| OT | VEH | 36.2±.0.2 | 37.4±.0.1 | 37.0±.0.2 | 36.9±.0.2 | 37.0±.0.2 |

| OT | CL 316243 | 36.4±.0.1 | 38.1±.0.2† | 37.9±.0.1* | 37.7±.0.2* | 37.7±.0.2† |

| *P<0.05 vs VEH | ||||||

| N=10–12/group | ||||||

CL 316243 also elevated TIBAT on injection day 22 at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1-h post-injection (P<0.05; Table 2B). Similarly, CL 316243, when given in combination with OT, also increased TIBAT at 0.5, 0.75 and 1-h post-injection and tended to elevate TIBAT at 0.25 and 1-h post-injection on injection day 22 (0.05<P<0.1). Both CL 316243 and CL 316243 + OT treatments elevated TIBAT relative to vehicle treated animals when the TIBAT data from injection day 22 were averaged over 1-h post-injection (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in the TIBAT response to CL 316243 and CL 316243 treatments when the TIBAT data were averaged over 60 min (P=NS).

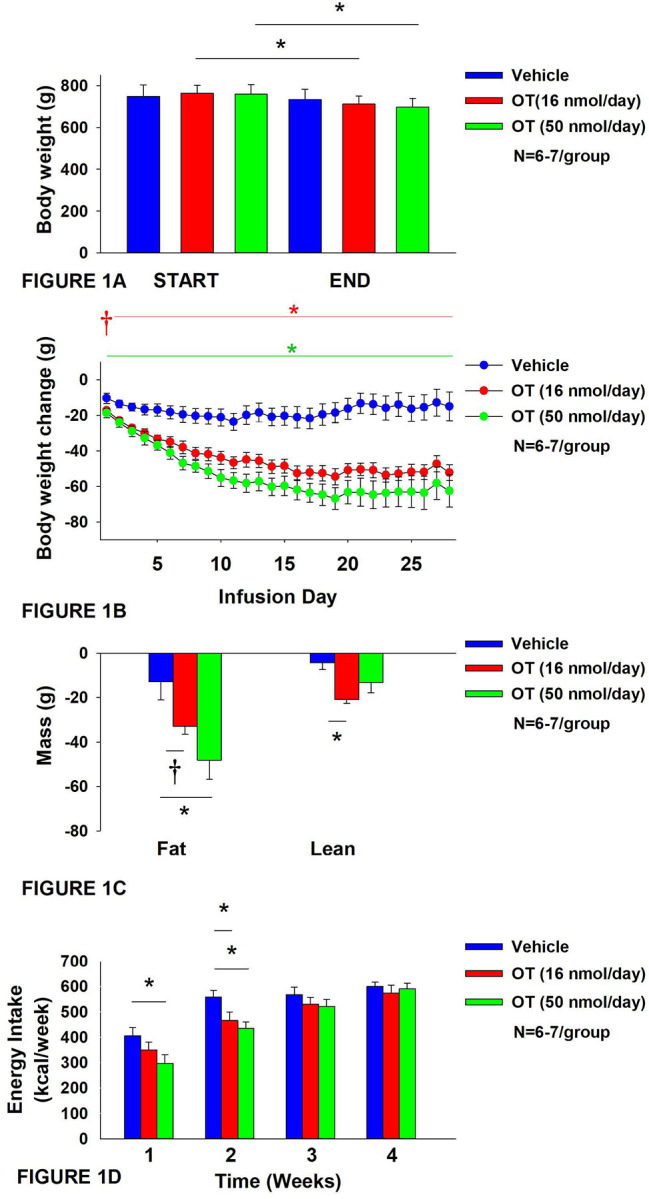

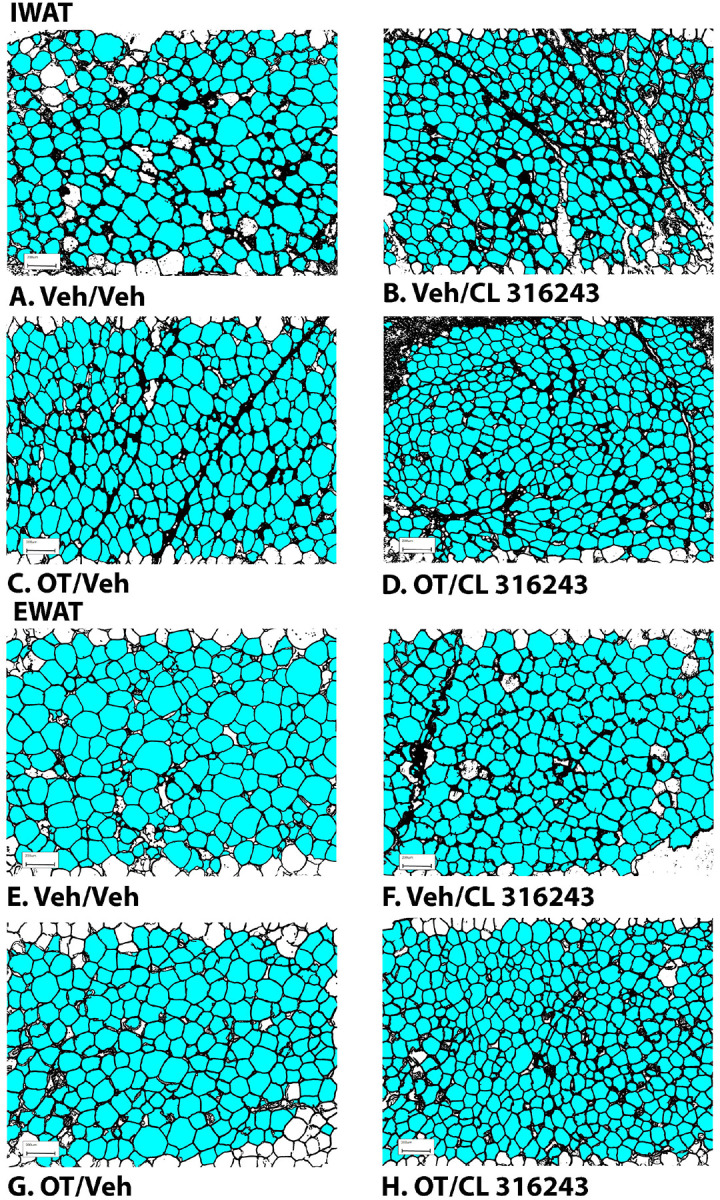

Adipocyte size

OT and CL 316243 given in combination reduced IWAT adipocyte size whereas there was no significant effect of OT or CL 316343 on adipocyte size when given alone (P=NS) (Figure 3A–D; Figure 4A). In contrast, CL 316243 alone (P<0.05) or in combination with OT (P<0.05) reduced EWAT adipocyte size in DIO rats relative to vehicle treatment (Figure 5E-H; Figure 4B). There were no significant differences in the ability of the combined treatment to reduce EWAT adipocyte size relative to OT alone (P=0.119) or CL 316243 alone (P=0.156).

Figure 3A-H: Effect of chronic 4V OT infusions (16 nmol/day) and systemic beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 31643) administration (0.5 mg/kg) on adipocyte size in IWAT and EWAT in male DIO rats.

Adipocyte size was analyzed using ImageJ. Images were taken from fixed (4% PFA) paraffin embedded sections (5 μm) containing IWAT (A-D) or EWAT (E-H) in HFD-fed rats treated with 4V OT (16 nmol/day) or 4V vehicle in combination with IP CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or IP vehicle. A/E, Veh/Veh. B/F, OT/Veh. C/G, Veh/CL 316243. D/H, OT-CL 316243; (A–H) all visualized at 100X magnification.

Figure 4A-B: Effect of chronic 4V OT infusions (16 nmol/day) and systemic beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 31643) administration (0.5 mg/kg) on adipocyte size in IWAT and EWAT in male DIO rats.

A, Adipocyte size (pixel2) was measured in IWAT from rats that received chronic 4V infusion of OT (16 nmol/day) or vehicle in combination with daily CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or vehicle treatment (N=4–9/group). B, Adipocyte size was measured in EWAT from rats that received chronic 4V infusion of OT (16 nmol/day) or vehicle in combination with daily CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or vehicle treatment (N=5–9/group). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 OT vs. vehicle.

Plasma hormone concentrations

To characterize the endocrine and metabolic effects of 4V OT (16 nmol/day) and systemic beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 316243) in DIO rats in a chronic study using as single dose of CL 316243 (Study 2; Table 3), we measured blood glucose levels and plasma concentrations of leptin, insulin, FGF-21, irisin, adiponectin, TC, triglycerides, and FFAs. CL 316243 alone or in combination with OT resulted in a reduction of plasma leptin relative to OT (P<0.05) or vehicle alone (P<0.05). The combination treatment was also associated with a reduction of blood glucose and insulin relative to vehicle (P<0.05) and OT treatment (P<0.05) but it was not statistically different from CL 316243 (P=NS). We also found that FGF-21 was reduced in response to CL 316243 and CL 316243 in combination with OT relative to vehicle and OT treatment (P<0.05). In addition, the combination treatment was associated with an elevation of adiponectin relative to vehicle (P<0.05) and OT treatment (P<0.05) but it was not statistically different from CL 316243 (P=NS).

Table 3.

Plasma measurements following 4V infusions of OT (16 nmol/day), CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or OT (16 nmol/day) + CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) in DIO rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters denote significant differences between treatments (P<0.05).

| SC | VEH/VEH | OTA/VEH | VEH/CL 316243 | OT/CL 316243 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 47.2 ± 6.0a | 45.9 ± 4.9a | 25.8 ± 3.4b | 22.0 ± 2.4b |

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 10.9 ± 2.3ac | 11.7 ± 1.5a | 6.6 ± 1.2bc | 4.3 ± 0.8b |

| FGF-21 (pg/mL) | 187.3 ± 22.5a | 163.9 ± 9.1a | 87.7 ± 8.0b | 101.5 ± 11.6c |

| Irisin (μg/mL) | 3.9 ± 0.3a | 4.5 ± 0.6a | 4.6 ± 0.4a | 4.4 ± 0.4a |

| Adiponectin (μg/mL) | 6.4 ± 0.6ac | 6.3 ± 0.6ac | 7.3 ± 0.6bc | 8.7 ± 0.5b |

| Blood Glucose (mg/dL) | 179.3 ± 24.5a | 174.9 ± 9.3a | 150 ± 3.7ab | 138 ± 4.5b |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 206.2 ± 10.7a | 213.1 ± 12.2a | 173.2 ± 7.7b | 180.9 ± 6.3b |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 81.5 ± 13.7ab | 97.5 ± 33.1a | 39.8 ± 3.9b | 47.8 ± 3.3ab |

| FFA (mEq/L) | 0.5 ± 0.1a | 0.5 ± 0.1a | 0.2 ± 0.02b | 0.3 ± 0.03ab |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 100.0 ± 6.0a | 108.1 ± 9.7a | 94.5 ± 5.1a | 107.0 ± 10.2a |

Different letters denote significant differences between treatments

Shared letters are not significantly different from one another

N=10–12/group

Gene expression data

We next determined the extent to which CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg), OT (16 nmol/day), or the combination treatment increased thermogenic gene expression in IBAT relative to vehicle at 2-hour post-CL 316243/vehicle injections.

IBAT:

Consistent with published findings in mice and rats, chronic CL 316243 administration elevated relative levels of the thermogenic markers Ucp1 [46; 47; 48], Dio2 [34; 49], Ppargc1a [47] and Gpr120 [34; 47] (Table 4A; P<0.05). CL 316243 in combination with OT also elevated Ucp1, Dio2, Ppargc1a and Gpr120 (P<0.05). In addition, chronic CL 316243 alone and in combination with OT reduced Adrb3 (β3-AR) mRNA expression in IBAT (Table 4A; P<0.05).

Table 4.

Changes in IBAT mRNA expression following chronic 4V OT (16 nmol/day) and systemic CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) treatment in male DIO rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Different letters denote significant differences between treatments (P<0.05).

| Table 4A. Changes in IEAT mRNA Expression Following SC OT and CL 316243 Treatment in Male | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIO Rats | ||||

| SC Treatment | VEH/VEH | OT/VEH | VEH/CL 316243 | OT/CL 316243 |

| IBAT | ||||

| Adrb1 | 1.0 ± 0.3a | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.8 ± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.4a |

| Adrb3 | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.2a | 0.5 ± 0.1b | 0.5 ± 0.04b |

| Ucp1 | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 1.6 ± 0.1b | 1.6 ± 0.1b |

| Cidea | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 1.0± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.1a |

| Dio2 | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 1.5 ± 0.2a | 3.3 ± 0.4b | 3.5 ± 0.3b |

| Gpr120 | 1.0 ± 0.2a | 0.9 ± 0.2a | 19.8 ± 2.4b | 15.9 ± 2.1b |

| Prdm16 | 1.0 ± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.1a | 0.8 ± 0.1a | 0.9 ± 0.1a |

| Ppargc1a | 1.0 ± 0.05a | 1.0 ± 0.2a | 4.8 ± 0.4b | 5.9 ± 0.5c |

| Different letters denote significant differences between treatments | ||||

| Shared letters are not significantly different from one another | ||||

| N=10–12/group | ||||

| Table 4B. Changes in IWAT mRNA Expression Following SC OT and CL 316243 Treatment in Male | ||||

| DIO Rats | ||||

| SC Treatment | VEH/VEH | OTA/VEH | VEH/CL 316243 | OT/CL 316243 |

| IWAT | ||||

| Adrb3 | 1.0 ± 0.4a | 1.1 ± 0.6a | 1.0 ± 0.3a | 0.5 ± 0.2a |

| Ucp1 | 1.0 ± 0.4a | 0.3 ± 0.1a | 0.5 ± 0.2a | 1.7 ± 0.8a |

| Dio2 | 1.0 ± 0.3a | 1.0 ± 0.2a | 0.6 ± 0.2a | 0.9 ± 0.3a |

| Ppargc1a | 1.0 ± 0.7a | 0.5 ± 0.4a | 1.5 ± 1.0a | 0.04 ± 0.02a |

| Different letters denote significant differences between treatments | ||||

| Shared letters are not significantly different from one another | ||||

| N =9–12/group | ||||

IWAT:

There were no significant differences in the thermogenic markers Ucp1, Dio2, Ppargc1a or Adrb3 in response to chronic CL 316243 alone or in combination with OT (Table 4B; P=NS).

As a functional readout of BAT thermogenesis for the gene expression analyses, we measured TIBAT in response to CL 316243 alone or CL 316243 + OT during the time period that preceded tissue collection. CL 316243 alone resulted in an increase in TIBAT at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1-h post-injection (Table 5; P<0.05). Similarly, CL 316243 + OT resulted in an increase in TIBAT at 0.25, 0.5 and 1-h post-injection (Table 5; P<0.05) and it also tended to increase TIBAT at 0.75-h post-injection (Table 5; 0.05<P<0.1).

Table 5.

TIBAT measurements following acute systemic administration of the beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 316243) or vehicle in male DIO rats. A, injection day 23 prior to euthanasia (0.5 mg/kg), euthanasia day. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 vs VEH; †0.05<P<0.1 vs VEH.

| SC | IP | 0 min | 15 min | 30 min | 45 min | 60 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | Temp (C°) | ||

| VEH | VEH | 36.7±.0.3 | 37.5±.0.2 | 37.4±.0.2 | 37.5±.0.2 | 37.2±.0.7 |

| VEH | CL 316243 | 36.7±.0.1 | 38.3±.0.3* | 38.5±.0.2* | 38.5±.0.2* | 38.3±.0.2* |

| OT | VEH | 36.3±.0.1 | 37.1±.0.3 | 37.5±.0.2 | 37.5±.0.2 | 37.1±.0.3 |

| OT | CL 316243 | 36.7±.0.2 | 37.8±.0.2* | 38.1±.0.2* | 38.0±.0.2† | 37.8±.0.2* |

P<0.05 vs VEH

0.05<P<0.1

N=9–12/group

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to determine the extent to which systemic OT could be used as an adjunct with the β3-AR agonist, CL 316243, to increase BAT thermogenesis and elicit weight loss in DIO rats. We hypothesized that systemic OT and beta-3 agonist (CL 316243) treatment would produce an additive effect to reduce body weight and adiposity in DIO rats by decreasing food intake and stimulating BAT thermogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we determined the effects of systemic (subcutaneous) infusions of OT (50 nmol/day) or vehicle (VEH) when combined with daily systemic (intraperitoneal) injections of CL 316243 (0.5 mg/kg) or VEH on body weight, adiposity, food intake and brown adipose tissue temperature (TIBAT). OT and CL 316243 monotherapy decreased body weight by 8.0±0.9% (P<0.05) and 8.6±0.6% (P<0.05), respectively, but OT in combination with CL 316243 produced more substantial weight loss (14.9±1.0%; P<0.05) compared to either treatment alone. These effects were associated with decreased adiposity, energy intake and elevated TIBAT during the treatment period. In addition, systemic OT and CL 316243 combination therapy increased IBAT thermogenic gene expression suggesting that increased BAT thermogenesis may also contribute to these effects. The findings from the current study suggest that the effects of systemic OT and CL 316243 to reduce body weight and adiposity are additive and appear to be driven primarily by OT-elicited changes in food intake and CL 316243-elicited increases in BAT thermogenesis.

Recent findings also indicate that other agents, namely the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, liraglutide, and the fat signal, oleoylethanolamide (OEA), act in an additive fashion with CL 316243 to reduce body weight or body weight gain. Oliveira recently reported that the combination of liraglutide and CL 316243 produce additive effects to reduce the change in body weight in a mouse model [50]. These effects appeared to be attributed to additive effects on energy intake and increased oxygen consumption in IBAT and IWAT. In addition, the combined treatment increased expression of UCP-1 in IWAT (indicative of browning). Similarly, Suarez and colleagues demonstrated that the peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor-α (PPARα) agonist and fat signal, oleoylethanolamide (OEA), act in an additive fashion with CL 316243 produced to reduce food intake and weight gain in rats [32]. These effects were associated with pronounced reductions in fat mass and increases in expression of thermogenic genes (PPARα and Ucp1) in EWAT [32]. Of interest is the finding that systemic OT and central OT can increase OEA expression in EWAT [19]. Furthermore, Deblon reported that the effectiveness of OT to decrease body weight was partially blocked in PPARα null mice [19], indicating that PPARα may partially mediate OT’s thermogenic effects in EWAT. OEA has also been found to stimulate 1) hypothalamic expression of OT mRNA [51], 2) PVN OT neurons [52], and 3) OT release within the PVN [52]. In addition, OEA also decreases food intake, in part, through OT receptor signaling [51]. Thus, it is possible that high fat diet-elicited stimulation of OEA [53] may reduce food intake, in part, through an OTR signaling and that the effects of OT to stimulate WAT thermogenesis might occur through PPARα. Additional studies that utilize adipose depot knockdown of PPARα will enable us to determine if PPARα in specific adipose depots may contribute to the ability of OT and CL 316243 to reduce body weight and adiposity.

Our findings and others raise the possibility that systemic OT could be reducing food intake and adiposity, in part, through a direct effect on peripheral OT receptors. Asker reported that OT-B12, a BBB-impermeable OT analogue, reduced food intake in rats, thus providing evidence that peripheral OTR signaling is important in the control of food intake [54]. Consistent with these findings, Iwasaki found that the ability of peripheral administration of OT to reduce food intake was attenuated in vagotomized mice [55; 56]. In addition, Brierley extended these findings and found that the effect of systemic administration of OT to suppress food intake required NTS preproglucagon neurons that receive direct synaptic input OTR-expressing vagal afferent neurons [57]. We also found that systemic administration of a non-BBB penetrant OTR antagonist, L-371257, stimulated food intake and body weight gain in [58]. Several studies have also found that subcutaneous infusion of OT reduced adipocyte size in 1) visceral fat in female Wistar rats that were peri- and postmenopausal [59] and 2) visceral fat in a dihydrotestosterone-elicited model of polycystic ovary syndrome in female Wistar rats [60], 3) subcutaneous fat in female ovariectomized Wistar rats [61], and 4) EWAT in male Zucker fatty rats [62]. More recent studies have confirmed that peripheral administration of long-acting OT analogues (including ASK2131 and ASK1476) also reduced both food intake and body weight [63; 64]. Together, these findings suggest that OT may also act in the periphery to decrease adipocyte size by a direct effect on OTRs found on adipose tissue [19; 20; 65]. Of translational importance is the finding that subcutaneous [19; 24; 25; 26; 27; 66] or intraperitoneal [27] administration of OT or long-acting OT analogues can recapitulate the effects of chronic CNS administration of OT on reductions of food intake and body weight.

The combination treatment and CL 316243 monotherapy reduced body weight and adiposity, in part, through increased BAT thermogenesis. Both CL 316243 alone and in combination with OT elevated TIBAT throughout the course of the injection study and increased IBAT thermogenic genes (UCP-1, DIO2 and Ppargc1a) and UCP-1 content in IBAT. These findings coincided with CL- 316243-elicited increases in TIBAT from the same animals during the time that preceded tissue collection. These findings are consistent with our previously published findings in rats [34] and other studies mice and rats that found chronic CL 316243 administration to increase the thermogenic markers DIO2 [49] and Gpr120 [46; 47; 48]. Similar to our findings, others also reported that systemic CL 316243 increased UCP-1 mRNA expression in mice [67]. We also found that the combination treatment and CL 316243 alone caused a downregulation of the β3-AR @ 2-h post-injection. This finding is consistent with we have previously reported [34] and others who have reported that both cold exposure and norepinephrine reduced β3-AR mRNA expression in mouse IBAT [68; 69] and.mouse brown adipocytes [70].

In summary, our results indicate that systemic administration of OT in combination with systemic CL 316243 treatment results in more profound reductions of body weight compared to either OT or CL 316243 alone. Moreover, the combined treatment of OT and CL 316243 stimulated BAT thermogenesis as determined by increased TIBAT and thermogenic gene expression in IBAT. Together, our data support the hypothesis that systemic OT and β3-AR agonist (CL 316243) treatment produce an additive effect to reduce body weight and adiposity in DIO rats. The effects of the combined treatment on body weight and adiposity appeared to be additive and driven predominantly by OT-elicited reductions of food intake and CL-316243-elicited increases in BAT thermogenesis.

Collectively, these findings suggest that systemic OT treatment could be a viable adjunct to other anti-obesity treatment strategies. While intranasal OT has been found to reduce body weight by approximately 9.3% in a small study with limited subjects (≈9.3%) [71], it was not found, however, to have any effect on body weight in a larger scale clinical study (N=subjects) in which subjects were matched well for body weight, adiposity and gender [72]. Importantly, Plessow, Lawson and colleagues did find a significant effect of intranasal OT to reduce energy intake at 6-weeks post-treatment, which served as an important control. It is possible that a more extended length of treatment might have been required to take advantage of the reductions of energy intake that were not observed until the 6-week post-treatment time point. In addition, changes in dose, dosing frequency, or co-administration with Mg2+ [73; 74] might need to be taken into consideration in order to maximize the effects of intranasal OT on body weight in humans who are overweight or obese. Given that OT can be an effective delivery approach to reduce energy intake and elicit weight loss in several rodent models (see [15; 75; 76] for review) and obese nonhuman primates [18], it will also be important to determine if chronic systemic OT treatment can elicit weight loss when given in combination with CL 316243 at doses that are sub-threshold for producing adverse effects on heart rate or blood pressure [77]. Recent findings indicate that OT can be effective at reducing food intake and/or body weight in female rats [78] and DIO male mice [25], respectively. Thus, it will be important to examine if this combination treatment produces an additive effect to reduce body weight and adiposity in female DIO rodents and nonhuman primates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the technical support of Nishi Ivanov.

This material was based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Rodent Metabolic Phenotyping Core and the Cellular and Molecular Imaging Core of the Diabetes Research Center at the University of Washington and supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P30DK017047. This work was also supported by the VA Merit Review Award 5 I01BX004102, from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service and NIH 5R01DK115976 grant to James Blevins. PJH’s research program also received research support during the project period from NIH grants DK-095980, HL-091333, HL-107256 and a Multi-campus grant from the University of California Office of the President.

Footnotes

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Disclosures: JEB had a financial interest in OXT Therapeutics, Inc., a company that developed highly specific and stable analogs of oxytocin to treat obesity and metabolic disease but this is no longer the case. The authors’ interests were reviewed and were managed by their local institutions in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. The other authors have nothing to report.

References

- [1].Smyth S., and Heron A., Diabetes and obesity: the twin epidemics. Nature medicine 12 (2006) 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Targher G., Mantovani A., Wang X.B., Yan H.D., Sun Q.F., Pan K.H., Byrne C.D., Zheng K.I., Chen Y.P., Eslam M., George J., and Zheng M.H., Patients with diabetes are at higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19. Diabetes & metabolism (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wilding J.P.H., Batterham R.L., Calanna S., Davies M., Van Gaal L.F., Lingvay I., McGowan B.M., Rosenstock J., Tran M.T.D., Wadden T.A., Wharton S., Yokote K., Zeuthen N., Kushner R.F., and Group S.S., Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. The New England journal of medicine 384 (2021) 989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Frias J.P., Davies M.J., Rosenstock J., Perez Manghi F.C., Fernandez Lando L., Bergman B.K., Liu B., Cui X., Brown K., and S.−. Investigators, Tirzepatide versus Semaglutide Once Weekly in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. The New England journal of medicine 385 (2021) 503–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chepurny O.G., Bonaccorso R.L., Leech C.A., Wollert T., Langford G.M., Schwede F., Roth C.L., Doyle R.P., and Holz G.G., Chimeric peptide EP45 as a dual agonist at GLP-1 and NPY2R receptors. Scientific reports 8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Frias J.P., Bastyr E.J., Vignati L., Tschop M.H., Schmitt C., Owen K., Christensen R.H., and DiMarchi R.D., The Sustained Effects of a Dual GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonist, NNC0090-2746, in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metabolism 26 (2017) 343–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Enebo L.B., Berthelsen K.K., Kankam M., Lund M.T., Rubino D.M., Satylganova A., and Lau D.C.W., Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of concomitant administration of multiple doses of cagrilintide with semaglutide 2.4 mg for weight management: a randomised, controlled, phase 1b trial. Lancet 397 (2021) 1736–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Frias J.P., Deenadayalan S., Erichsen L., Knop F.K., Lingvay I., Macura S., Mathieu C., Pedersen S.D., and Davies M., Efficacy and safety of co-administered once-weekly cagrilintide 2.4 mg with once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg in type 2 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 402 (2023) 720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Allison D.B., Gadde K.M., Garvey W.T., Peterson C.A., Schwiers M.L., Najarian T., Tam P.Y., Troupin B., and Day W.W., Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity 20 (2012) 330–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jastreboff A.M., Aronne L.J., Ahmad N.N., Wharton S., Connery L., Alves B., Kiyosue A., Zhang S., Liu B., Bunck M.C., Stefanski A., and S.−. Investigators, Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. The New England journal of medicine 387 (2022) 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Aronne L.J., Sattar N., Horn D.B., Bays H.E., Wharton S., Lin W.Y., Ahmad N.N., Zhang S., Liao R., Bunck M.C., Jouravskaya I., Murphy M.A., and S.-. Investigators, Continued Treatment With Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults With Obesity: The SURMOUNT-4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jastreboff A.M., Kaplan L.M., and Hartman M.L., Triple-Hormone-Receptor Agonist Retatrutide for Obesity. Reply. The New England journal of medicine 389 (2023) 1629–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gimpl G., and Fahrenholz F., The oxytocin receptor system: structure, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev 81 (2001) 629–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Blevins J.E., and Baskin D.G., Translational and therapeutic potential of oxytocin as an anti-obesity strategy: Insights from rodents, nonhuman primates and humans. Physiol Behav (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lawson E.A., The effects of oxytocin on eating behaviour and metabolism in humans. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 13 (2017) 700–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lawson E.A., Olszewski P.K., Weller A., and Blevins J.E., The role of oxytocin in regulation of appetitive behaviour, body weight and glucose homeostasis. J Neuroendocrinol 32 (2020) e12805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McCormack S.E., Blevins J.E., and Lawson E.A., Metabolic Effects of Oxytocin. Endocrine reviews 41 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blevins J.E., Graham J.L., Morton G.J., Bales K.L., Schwartz M.W., Baskin D.G., and Havel P.J., Chronic oxytocin administration inhibits food intake, increases energy expenditure, and produces weight loss in fructose-fed obese rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308 (2015) R431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Deblon N., Veyrat-Durebex C., Bourgoin L., Caillon A., Bussier A.L., Petrosino S., Piscitelli F., Legros J.J., Geenen V., Foti M., Wahli W., Di Marzo V., and Rohner-Jeanrenaud F., Mechanisms of the anti-obesity effects of oxytocin in diet-induced obese rats. PloS one 6 (2011) e25565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yi K.J., So K.H., Hata Y., Suzuki Y., Kato D., Watanabe K., Aso H., Kasahara Y., Nishimori K., Chen C., Katoh K., and Roh S.G., The regulation of oxytocin receptor gene expression during adipogenesis. J Neuroendocrinol 27 (2015) 335–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Noble E.E., Billington C.J., Kotz C.M., and Wang C., Oxytocin in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus reduces feeding and acutely increases energy expenditure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 307 (2014) R737–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang G., Bai H., Zhang H., Dean C., Wu Q., Li J., Guariglia S., Meng Q., and Cai D., Neuropeptide exocytosis involving synaptotagmin-4 and oxytocin in hypothalamic programming of body weight and energy balance. Neuron 69 (2011) 523–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang G., and Cai D., Circadian intervention of obesity development via resting-stage feeding manipulation or oxytocin treatment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 301 (2011) E1004–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Blevins J.E., Thompson B.W., Anekonda V.T., Ho J.M., Graham J.L., Roberts Z.S., Hwang B.H., Ogimoto K., Wolden-hanson T.H., Nelson J.O., Kaiyala K.J., Havel P.J., Bales K.L., Morton G.J., Schwartz M.W., and Baskin D.G., Chronic CNS oxytocin signaling preferentially induces fat loss in high fat diet-fed rats by enhancing satiety responses and increasing lipid utilization. Am J Physiol-Reg I (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maejima Y., Aoyama M., Sakamoto K., Jojima T., Aso Y., Takasu K., Takenosihita S., and Shimomura K., Impact of sex, fat distribution and initial body weight on oxytocin’s body weight regulation. Scientific reports 7 (2017) 8599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Maejima Y., Iwasaki Y., Yamahara Y., Kodaira M., Sedbazar U., and Yada T., Peripheral oxytocin treatment ameliorates obesity by reducing food intake and visceral fat mass. Aging 3 (2011) 1169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Morton G.J., Thatcher B.S., Reidelberger R.D., Ogimoto K., Wolden-Hanson T., Baskin D.G., Schwartz M.W., and Blevins J.E., Peripheral oxytocin suppresses food intake and causes weight loss in diet-induced obese rats. Am J Physiol-Endoc M 302 (2012) E134–E144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Roberts Z.S., Wolden-Hanson T.H., Matsen M.E., Ryu V., Vaughan C.H., Graham J.L., Havel P.J., Chukri D.W., Schwartz M.W., Morton G.J., and Blevins J.E., Chronic Hindbrain Administration of Oxytocin is Sufficient to Elicit Weight Loss in Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (2017) ajpregu 00169 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Head M.A., Levine A.S., Christian D.G., Klockars A., and Olszewski P.K., Effect of combination of peripheral oxytocin and naltrexone at subthreshold doses on food intake, body weight and feeding-related brain gene expression in male rats. Physiol Behav 238 (2021) 113464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Enriori P.J., Sinnayah P., Simonds S.E., Garcia Rudaz C., and Cowley M.A., Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance. J Neurosci 31 (2011) 12189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mirbolooki M.R., Upadhyay S.K., Constantinescu C.C., Pan M.L., and Mukherjee J., Adrenergic pathway activation enhances brown adipose tissue metabolism: A [F-18]FDG PET/CT study in mice. Nucl Med Biol 41 (2014) 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Suarez J., Rivera P., Arrabal S., Crespillo A., Serrano A., Baixeras E., Pavon F.J., Cifuentes M., Nogueiras R., Ballesteros J., Dieguez C., and de Fonseca F.R., Oleoylethanolamide enhances beta-adrenergic-mediated thermogenesis and white-to-brown adipocyte phenotype in epididymal white adipose tissue in rat. Disease models & mechanisms 7 (2014) 129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xiao C., Goldgof M., Gavrilova O., and Reitman M.L., Anti-obesity and metabolic efficacy of the beta3-adrenergic agonist, CL316243, in mice at thermoneutrality compared to 22 degrees C. Obesity 23 (2015) 1450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Edwards M.M., Nguyen H.K., Dodson A.D., Herbertson A.J., Wietecha T.A., Wolden-Hanson T., Graham J.L., Honeycutt M.K., Slattery J.D., O’Brien K.D., Havel P.J., and Blevins J.E., Effects of combined oxytocin and beta-3 receptor agonist (CL 316243) treatment on body weight and adiposity in male diet-induced obese rats. Frontiers in physiology (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Brito M.N., Brito N.A., Baro D.J., Song C.K., and Bartness T.J., Differential activation of the sympathetic innervation of adipose tissues by melanocortin receptor stimulation. Endocrinology 148 (2007) 5339–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vaughan C.H., Shrestha Y.B., and Bartness T.J., Characterization of a novel melanocortin receptor-containing node in the SNS outflow circuitry to brown adipose tissue involved in thermogenesis. Brain Res 1411 (2011) 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Edwards M.M., Nguyen H.K., Herbertson A.J., Dodson A.D., Wietecha T., Wolden-Hanson T., Graham J.L., O’Brien K.D., Havel P.J., and Blevins J.E., Chronic Hindbrain Administration of Oxytocin Elicits Weight Loss in Male Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Malinowska B., and Schlicker E., Further evidence for differences between cardiac atypical beta-adrenoceptors and brown adipose tissue beta3-adrenoceptors in the pithed rat. British journal of pharmacology 122 (1997) 1307–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cao Q., Jing J., Cui X., Shi H., and Xue B., Sympathetic nerve innervation is required for beigeing in white fat. Physiological reports 7 (2019) e14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Veniant M.M., Sivits G., Helmering J., Komorowski R., Lee J., Fan W., Moyer C., and Lloyd D.J., Pharmacologic Effects of FGF21 Are Independent of the “Browning” of White Adipose Tissue. Cell Metab 21 (2015) 731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Bremer A.A., Stanhope K.L., Graham J.L., Cummings B.P., Wang W., Saville B.R., and Havel P.J., Fructose-fed rhesus monkeys: a nonhuman primate model of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Clinical and translational science 4 (2011) 243–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Blevins J.E., Moralejo D.H., Wolden-Hanson T.H., Thatcher B.S., Ho J.M., Kaiyala K.J., and Matsumoto K., Alterations in activity and energy expenditure contribute to lean phenotype in Fischer 344 rats lacking the cholecystokinin-1 receptor gene. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303 (2012) R1231–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cummings B.P., Digitale E.K., Stanhope K.L., Graham J.L., Baskin D.G., Reed B.J., Sweet I.R., Griffen S.C., and Havel P.J., Development and characterization of a novel rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the UC Davis type 2 diabetes mellitus UCD-T2DM rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295 (2008) R1782–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Livak K.J., and Schmittgen T.D., Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25 (2001) 402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Gonzalez-Hurtado E., Lee J., Choi J., and Wolfgang M.J., Fatty acid oxidation is required for active and quiescent brown adipose tissue maintenance and thermogenic programing. Molecular metabolism 7 (2018) 45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rosell M., Kaforou M., Frontini A., Okolo A., Chan Y.W., Nikolopoulou E., Millership S., Fenech M.E., MacIntyre D., Turner J.O., Moore J.D., Blackburn E., Gullick W.J., Cinti S., Montana G., Parker M.G., and Christian M., Brown and white adipose tissues: intrinsic differences in gene expression and response to cold exposure in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306 (2014) E945–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Suarez J., Rivera P., Arrabal S., Crespillo A., Serrano A., Baixeras E., Pavon F.J., Cifuentes M., Nogueiras R., Ballesteros J., Dieguez C., and Rodriguez de Fonseca F., Oleoylethanolamide enhances beta-adrenergic-mediated thermogenesis and white-to-brown adipocyte phenotype in epididymal white adipose tissue in rat. Disease models & mechanisms 7 (2014) 129–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].de Jong J.M.A., Wouters R.T.F., Boulet N., Cannon B., Nedergaard J., and Petrovic N., The beta3-adrenergic receptor is dispensable for browning of adipose tissues. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 312 (2017) E508–E518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Oliveira F.C.B., Bauer E.J., Ribeiro C.M., Pereira S.A., Beserra B.T.S., Wajner S.M., Maia A.L., Neves F.A.R., Coelho M.S., and Amato A.A., Liraglutide Activates Type 2 Deiodinase and Enhances beta3-Adrenergic-Induced Thermogenesis in Mouse Adipose Tissue. Frontiers in endocrinology 12 (2021) 803363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gaetani S., Fu J., Cassano T., Dipasquale P., Romano A., Righetti L., Cianci S., Laconca L., Giannini E., Scaccianoce S., Mairesse J., Cuomo V., and Piomelli D., The fat-induced satiety factor oleoylethanolamide suppresses feeding through central release of oxytocin. J Neurosci 30 (2010) 8096–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Romano A., Cassano T., Tempesta B., Cianci S., Dipasquale P., Coccurello R., Cuomo V., and Gaetani S., The satiety signal oleoylethanolamide stimulates oxytocin neurosecretion from rat hypothalamic neurons. Peptides 49 (2013) 21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sospedra I., Moral R., Escrich R., Solanas M., Vela E., and Escrich E., Effect of High Fat Diets on Body Mass, Oleylethanolamide Plasma Levels and Oxytocin Expression in Growing Rats. J Food Sci 80 (2015) H1425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Asker M., Krieger J.P., Liles A., Tinsley I.C., Borner T., Maric I., Doebley S., Furst C.D., Borchers S., Longo F., Bhat Y.R., De Jonghe B.C., Hayes M.R., Doyle R.P., and Skibicka K.P., Peripherally restricted oxytocin is sufficient to reduce food intake and motivation, while CNS entry is required for locomotor and taste avoidance effects. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 25 (2023) 856–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Iwasaki Y., Kumari P., Wang L., Hidema S., Nishimori K., and Yada T., Relay of peripheral oxytocin to central oxytocin neurons via vagal afferents for regulating feeding. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 519 (2019) 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Iwasaki Y., Maejima Y., Suyama S., Yoshida M., Arai T., Katsurada K., Kumari P., Nakabayashi H., Kakei M., and Yada T., Peripheral oxytocin activates vagal afferent neurons to suppress feeding in normal and leptin-resistant mice: a route for ameliorating hyperphagia and obesity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308 (2015) R360–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Brierley D.I., Holt M.K., Singh A., de Araujo A., McDougle M., Vergara M., Afaghani M.H., Lee S.J., Scott K., Maske C., Langhans W., Krause E., de Kloet A., Gribble F.M., Reimann F., Rinaman L., de Lartigue G., and Trapp S., Central and peripheral GLP-1 systems independently suppress eating. Nat Metab 3 (2021) 258–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ho J.M., Anekonda V.T., Thompson B.W., Zhu M., Curry R.W., Hwang B.H., Morton G.J., Schwartz M.W., Baskin D.G., Appleyard S.M., and Blevins J.E., Hindbrain oxytocin receptors contribute to the effects of circulating oxytocin on food intake in male rats. Endocrinology 155 (2014) 2845–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Erdenebayar O., Kato T., Kawakita T., Kasai K., Kadota Y., Yoshida K., Iwasa T., and Irahara M., Effects of peripheral oxytocin administration on body weight, food intake, adipocytes, and biochemical parameters in peri- and postmenopausal female rats. Endocrine journal (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Iwasa T., Matsuzaki T., Mayila Y., Kawakita T., Yanagihara R., and Irahara M., The effects of chronic oxytocin administration on body weight and food intake in DHT-induced PCOS model rats. Gynecological endocrinology : the official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Endocrinology 36 (2020) 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Iwasa T., Matsuzaki T., Mayila Y., Yanagihara R., Yamamoto Y., Kawakita T., Kuwahara A., and Irahara M., Oxytocin treatment reduced food intake and body fat and ameliorated obesity in ovariectomized female rats. Neuropeptides 75 (2019) 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Balazova L., Krskova K., Suski M., Sisovsky V., Hlavacova N., Olszanecki R., Jezova D., and Zorad S., Metabolic effects of subchronic peripheral oxytocin administration in lean and obese zucker rats. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society 67 (2016) 531–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Elfers C.T., Blevins J.E., Salameh T.S., Lawson E.A., Silva D., Kiselyov A., and Roth C.L., Novel Long-Acting Oxytocin Analog with Increased Efficacy in Reducing Food Intake and Body Weight. International journal of molecular sciences 23 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Elfers C.T., Blevins J.E., Lawson E.A., Pittner R., Silva D., Kiselyov A., and Roth C.L., Robust Reductions of Body Weight and Food Intake by an Oxytocin Analog in Rats. Frontiers in physiology 12 (2021) 726411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Schaffler A., Binart N., Scholmerich J., and Buchler C., Hypothesis paper Brain talks with fat--evidence for a hypothalamic-pituitary-adipose axis? Neuropeptides 39 (2005) 363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Altirriba J., Poher A.L., Caillon A., Arsenijevic D., Veyrat-Durebex C., Lyautey J., Dulloo A., and Rohner-Jeanrenaud F., Divergent effects of oxytocin treatment of obese diabetic mice on adiposity and diabetes. Endocrinology 155 (2014) 4189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Yoshitomi H., Yamazaki K., Abe S., and Tanaka I., Differential regulation of mouse uncoupling proteins among brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle in chronic beta 3 adrenergic receptor agonist treatment. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 253 (1998) 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Kasahara Y., Sato K., Takayanagi Y., Mizukami H., Ozawa K., Hidema S., So K.H., Kawada T., Inoue N., Ikeda I., Roh S.G., Itoi K., and Nishimori K., Oxytocin receptor in the hypothalamus is sufficient to rescue normal thermoregulatory function in male oxytocin receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology 154 (2013) 4305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kasahara Y., Tateishi Y., Hiraoka Y., Otsuka A., Mizukami H., Ozawa K., Sato K., Hidema S., and Nishimori K., Role of the Oxytocin Receptor Expressed in the Rostral Medullary Raphe in Thermoregulation During Cold Conditions. Frontiers in endocrinology 6 (2015) 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bengtsson T., Cannon B., and Nedergaard J., Differential adrenergic regulation of the gene expression of the beta-adrenoceptor subtypes beta1, beta2 and beta3 in brown adipocytes. The Biochemical journal 347 Pt 3 (2000) 643–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zhang H., Wu C., Chen Q., Chen X., Xu Z., Wu J., and Cai D., Treatment of obesity and diabetes using oxytocin or analogs in patients and mouse models. PloS one 8 (2013) e61477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Plessow F., Kerem L., Wronski M.L., Asanza E., O’Donoghue M.L., Stanford F.C., Eddy K.T., Holmes T.M., Misra M., Thomas J.J., Galbiati F., Muhammed M., Sella A.C., Hauser K., Smith S.E., Holman K., Gydus J., Aulinas A., Vangel M., Healy B., Kheterpal A., Torriani M., Holsen L.M., Bredella M.A., and Lawson E.A., Intranasal Oxytocin for Obesity. NEJM Evid 3 (2024) EVIDoa2300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Bharadwaj V.N., Meyerowitz J., Zou B., Klukinov M., Yan N., Sharma K., Clark D.J., Xie X., and Yeomans D.C., Impact of Magnesium on Oxytocin Receptor Function. Pharmaceutics 14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Antoni F.A., and Chadio S.E., Essential role of magnesium in oxytocin-receptor affinity and ligand specificity. The Biochemical journal 257 (1989) 611–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Niu J., Tong J., and Blevins J.E., Oxytocin as an Anti-obesity Treatment. Front Neurosci 15 (2021) 743546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Olszewski P.K., Noble E.E., Paiva L., Ueta Y., and Blevins J.E., Oxytocin as a Potential Pharmacological Tool to Combat Obesity. Journal of Neuroendocrinology In press (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Cypess A.M., Weiner L.S., Roberts-Toler C., Franquet Elia E., Kessler S.H., Kahn P.A., English J., Chatman K., Trauger S.A., Doria A., and Kolodny G.M., Activation of human brown adipose tissue by a beta3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Cell Metab 21 (2015) 33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Liu C.M., Davis E.A., Suarez A.N., Wood R.I., Noble E.E., and Kanoski S.E., Sex Differences and Estrous Influences on Oxytocin Control of Food Intake. Neuroscience 447 (2020) 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]