Abstract

Purpose

Macrophage immune cells play crucial roles in the inflammatory (M1) and regenerative (M2) processes. The extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, including presentation of embedded ligands, governs macrophage function. Laminin concentration is abundant in the basement membrane and is dependent on pathological state: reduced in inflammation and increased during regeneration. Distinct laminin ligands, such as IKVAV and YIGSR, have disparate roles in dictating cell function. For example, IKVAV, derived from the alpha chain of laminin, promotes angiogenesis and metastasis of cancer cells whereas YIGSR, beta chain derived, impedes angiogenesis and tumor progression. Previous work has demonstrated IKVAV’s inflammation inhibiting properties in macrophages. Given the divergent role of IKVAV and YIGSR in interacting with cells through varied integrin receptors, we ask: what role does laminin derived peptide YIGSR play in governing macrophage function?

Methods

We quantified the influence of YIGSR on macrophage phenotype in 2D and 3D via immunostaining assessments for M1 marker inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and M2 marker Arginase−1 (Arg-1). We also analysed the secretome of human and murine macrophage response to YIGSR via a Luminex bead assay.

Results

YIGSR impact on macrophage phenotype occurs in a concentration-dependent manner. At lower concentrations of YIGSR, macrophage inflammation was increased whereas, at higher concentrations of YIGSR the opposite effect was seen within the same time frame. Secretomic assessments also demonstrate that pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines were increased at low YIGSR concentrations in M0, M1, M2 macrophages while pro-inflammatory secretion was reduced at higher concentrations.

Conclusions

YIGSR can be used as a tool to modulate macrophage inflammatory state within M1 and M2 phenotypes depending on the concentration of peptide. YIGSR’s impact on macrophage function can be leveraged for the development of immunoengineering strategies in regenerative medicine and cancer therapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12195-024-00810-5.

Keywords: Laminin, Peptides, YIGSR, Macrophages, Macrophage phenotypes, Inflammation

Introduction

Macrophage innate immune cells are crucial cells for phagocytosis of foreign bodies and inflammation resolution, adopting different functions based on their microenvironment [1–4]. Macrophage function, or phenotypic state, varies across tissues and stimulations [5]. These phenotypes can promote inflammation (M1) or promote inflammation resolution (M2) [6, 7]. Macrophage phenotypes are dictated by the surrounding microenvironment and include response to cytokines, chemokines, and cellular mediators. A more recently acknowledged mediation of macrophage activation includes proteins and glycans in the extracellular matrix (ECM)[ 8, 9]. Serving as a scaffold for cell-matrix interaction, the ECM is a dynamic microenvironment that supports the adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation of macrophages through a combination of proteins including collagen, laminin, fibronectin, elastin, etc. [10–12].1

One way ECM signaling occurs through integrin-ligand pairing between integrin receptors on the cells and the ligand cognates on the ECM protein [13, 14]. Integrins are transmembrane bidirectional signaling adhesion receptors that mediate biochemical cues from the ECM to the cell or vice versa [15–18]. Our prior work and the work of others has demonstrated that the functional state of macrophages is influenced by the interactions between macrophages and ECM ligands found in fibrinogen, fibrin, and collagen I [19–25]. While ECM proteins and integrin receptor-ligand pairs can determine macrophage function, it is not yet fully understood how integrin-ligand interactions of other common proteins like laminin inform macrophage function. This gap in knowledge limits our understanding of macrophage functional regulation in the ECM. Our work focuses on the influence of ECM ligands in governing macrophage activation.

Laminin, one common ECM protein, plays a vital part in cell processes specifically differentiation and migration as they are an abundant component of the basement membranes of the vascular endothelium [26, 27]. Laminins are composed of α-, β-, and γ-chains which exist in various genetically distinct forms [28, 29]. Monocytes and macrophages migrate through the basement membrane to enter tissues, tumors, and wound sites [30]. Laminin deposition in dermal wounds is essential to propagate angiogenesis and regeneration [31]. Defective laminin anchoring and perturbations in basement membranes have also promoted metastasis and tumor growth [32, 33]. Considering the abundance of laminin in the ECM and basement membranes, it is important to investigate how macrophages respond to laminin ligands.

Each laminin chain plays a different role with regard to ECM composition. For example, the peptide derived from the α-chain Ile-Lys-Val-Ala-Val (IKVAV) promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth, while β-chain derived tyrosine-isoleucine-glycine-serine-arginine or Tyr-Ile-Gly-Ser-Arg (YIGSR) inhibits angiogenesis, and prevents tumor growth [34, 35]. Both IKVAV and YIGSR peptides play opposing biological roles. Previous work highlighted IKVAV’s role as a mild M1 inhibitor by reducing expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, M1 marker) and promoting expression of anti-inflammatory markers [25]. YIGSR has been utilized as an inhibitor for tumor metastasis by promoting inflammation in fibroblasts, myocytes, and endothelial cells [36–38]. However, with few studies investigating YIGSR’s effect on macrophage function, this area is not fully explored [39, 40]. In this work, we investigated the role of YIGSR on macrophage phenotype attenuation. This work provides a fundamental understanding of macrophage-laminin interactions, and highlights the future design of peptide therapies to modulate macrophage function.

In general, the regulation of macrophage adhesion to laminin involves specific and dynamic matrix integrin-cytoskeletal interactions. It is speculated that macrophages activated by interferon gamma (IFNγ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to an M1 phenotype is required for adhering to laminin [41]. A previous study provides evidence that macrophage adhesion to laminin is mediated by the α6β1 integrin. Integrin α6β1 is critical for macrophage adhesion, as blocking expression of α6β1 inhibited macrophage adhesion [42]. Since YIGSR is a ligand for α6β1 [43], we hypothesize that YIGSR, either via soluble delivery in 2D or immobilized in 3D poly(ethylene) glycol (PEG) hydrogels, will increase the activation of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages. Because macrophage response in 2D and 3D is disparate, we leverage both platforms to characterize macrophage function, phenotype, and secretomic profile following interaction with YIGSR.

In this work, YIGSR promoted pro-inflammatory/M1 activation in murine and human cells at lower concentrations (2 mM) by increasing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression. Secretomic assessment via Luminex demonstrated an upregulation of pro-inflammatory chemokines such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP-1); and pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and IL-2R, following interaction with YIGSR. In a 3D PEG-YIGSR hydrogel, 5 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels increased M1 activation of encapsulated macrophages. YIGSR had a noteworthy response of affecting macrophage phenotype based on the concentration of exposure, wherein lower concentrations promoted M1 and higher concentrations promoted M2. Hence, we leveraged the PEG-based biomaterial platforms to investigate laminin-derived YIGSR influence on macrophage function, demonstrating that YIGSR promotes macrophage inflammation and that response of macrophages to YIGSR is concentration-dependent. Investigating the roles of ECM ligands on macrophage function will aid in increasing understanding of fundamental immunological processes and designing targeted therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Raw 264.7 macrophages (ATCC; Cat.TIB-71; Lot no. 70046149) cell line and primary C57BL/6 Murine Bone Marrow Macrophages (Cat. C57-6030, Cell Biologics) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Corning, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 100 IU penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Corning, NY). This was referred to as M0 media, and macrophages cultured in this media were M0 macrophages. To stimulate macrophages to attain the M1 like phenotype, 10 ng/mL of interferon gamma (IFNγ) (Prospec, East Brunswick, NJ) along with 100 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) was added to M0 media, making it M1 media. Macrophages cultured in M1 media were referred to as M1 macrophages. To obtain M2 polarized macrophages, 20 ng/mL of interleukin (IL)− 4 (Prospec, East Brunswick, NJ) was added to M0 media, labelling it M2 media. These macrophages were referred as M2 macrophages. All macrophages were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Human pan monocytes from a healthy 41-year old Mexican/American male were purchased from Hemacare, Charles River Laboratory (Cat. PB14-16NC-1; Lot no. 22077073) (#IRB 2055809-1). Monocytes were thawed in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without calcium or magnesium, 10% heath inactivated human (AB) serum, (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA), and Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH). The medium for differentiating monocytes to macrophages consisted of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (20 ng/mL), RPMI 1640, 10% heat inactivated human (AB) serum, 100 IU penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. Monocytes were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 5 days with a media change on day 3. In the presence of M-CSF, monocyte-derived macrophages were polarized to the M1 phenotype on day 5. On day 5, the M1 or classically activated macrophages were stimulated with 100 ng/mL of LPS and 10 ng/mL of IFNγ with the M1 culture media. For stimulation to the M2 phenotype, 20 ng/mL of interleukin (IL)− 4 (Prospec, East Brunswick, NJ) was added the M2 media. Additionally, YIGSR peptide at various concentrations was also added to respective wells. Macrophages were stimulated for 2 days in 37 °C with 5% CO2 and processed for further data generation on day 7 since thawing.

For all 2D experiments, cells were plated at a density of 0.1 × 106 cells/mL or 0.06 × 106 cells/mL on glass bottom 24-well plates. For 3D experiments, macrophages were seeded at 1 × 106 cells per well in a 6-well plate to prepare for encapsulation. Macrophages were cultured in M0, M1, or M2 media with or without YIGSR for 48 h a day after seeding. Macrophages were fixed with 4% formalin for immunostaining and supernatant was collected to perform cytokine/chemokine assessments. Macrophages were gently scraped to lift them off the plates for encapsulations or rinsing steps.

Fabrication of the PEG-YIGSR Hydrogel

The laminin-derived cell adhesive peptide sequence YIGSR (MW = 594.67 g/mol) was purchased from Genscript (purity > 98%). To facilitate copolymerization of YIGSR with PEGDA, the peptide was conjugated with acryl-PEG-succinimidyl valerate (acryl-PEG-SVA; MW = 3400 g/mol; Laysan Bio. Inc., Arab, AL) using amine substitution reaction as previously described [44, 45]. A molar ratio of 1.2:1 for IKVAV to PEG-SVA was mixed with 20 mM HEPBS buffer following titrations with 0.5 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) to obtain a pH of 8, and the reaction occurred overnight at 4 °C protected from light. The product acryl-PEG-YIGSR was then dialyzed (MWCO: 3.5 kDa; Spectrum laboratories) against dH2O for 48 h to remove unreacted peptide. The final product was lyophilized and stored at – 80 °C until use. Other components conjugated were Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser (RGDS; MW = 433.42 g/mol) to PEG for cell adhesion at 1.2:1 molar ratio. The conjugated PEG-peptides were reconstituted with sterile HEPES buffered saline and 1.5% TEAO solution.

Encapsulation of Macrophages in PEG-YIGSR Hydrogels

Macrophages were encapsulated in control and experimental (PEG-YIGSR) groups. Two concentrations of PEG-YIGSR were tested, specifically, 5 mM and 10 mM. The control hydrogels constituted 5% PEGDA and 3.5 mM PEG-RGDS. The PEG-YIGSR hydrogels consisted of 5% PEGDA, 3.5 mM PEG-RGDS, and either 5 mM or 10 mM PEG-YIGSR. To understand bidirectional interactions between RGDS and YIGSR, macrophages were encapsulated in varying concentrations of RGDS with or without YIGSR. Specifically, the concentrations chosen were 0 mM, 1 mM, 3.5 mM, 5 mM consistent with prior literature [46, 47]. A scrambled YIGSR peptide (YSRIG) was also included in the study. Human primary macrophages were encapsulated in various groups of RGDS + YIGSR or RGDS + YSRIG combinations wherein PEG-YIGSR concentration was kept constant at 0 or 5 mM (since 5 mM PEG-YIGSR had the most significant impact on iNOS expression of M1 macrophages).

Eosin Y (10 μM), a photoinitiator, and 0.35% N-Vinylpyrrolidone (NVP), an accelerator for gelation, were mixed with the macromer’s solution. Approximately 15,000 cells were added to the mixture for each gel. A 5 μL volume of the cell suspension and polymer solution was pipetted onto a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) slab with two PDMS spacers (385 μm thick) to allow for the 3D hydrogel formation. On white light exposure for 60 s under a methacrylated cover slip, free radicals were generated due to the activation of eosin Y in the solution. Rapid polymerization occurred due to NVP and under white light with macrophages encapsulated inside the hydrogel microenvironment. The hydrogels were then placed in 24-well plates and media was gently pipetted into wells.

YIGSR Dose Response in 2D and 3D

Raw 264.7 macrophages, primary murine bone-marrow derived macrophages, and primary human monocyte-derived macrophages were seeded onto 24-well glass-bottom well plates at 0.06 × 106 cells/mL or 0.1 × 106 cells/mL respectively. Post 24 h of seeding to allow adherence, macrophages were stimulated to the M1 or M2 phenotype and incubated for another 48 h. At the 24 h time point, along with adding polarizing media, various concentrations of YIGSR peptide were also dissolved into the medium to quantify appropriate concentration for macrophage modulation. Specifically, the concentrations of YIGSR used for 2D experiments were 2 mM, 5 mM, and 8 mM (n = 3 for each group with M0, M1, and M2 macrophages). The soluble YIGSR treated macrophages were processed after 48 h of treatment for further analysis.

Human monocyte-derived macrophages were encapsulated at a density of approximately 15,000 cells per gel. The concentrations of PEG-YIGSR tested were 5 mM and 10 mM. Post 24 h of encapsulation, all hydrogels with encapsulated macrophages were stimulated to the M1 and M2 phenotypes. Encapsulated macrophages were exposed to M1, M2 media for another 48 h before fixing for immunostaining. There were 2 biological replicates and 4 technical replicates (n = 4 gels for each group).

Cell Viability Assay

A live/dead assay was performed to assess cell viability with YIGSR treatment. This assay employs a Calcein AM dye, which emits a green fluorescence upon retention within live cells. It also employs an ethidium homodimer-1 dye emitting red fluorescence and indicating loss of plasma membrane integrity. Cells were stained with the Live and Dead reagent (4 µM Calcein AM, 8 µM ethidium homodimer-1) and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. Cells were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2).

Immunostaining

All samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for immunofluorescence staining (20 mins for 2D, 45 mins for 3D). Permeabilization of the cell membrane occurred in the presence of 0.125% Triton-X for 10mins (2D) or 0.25% Triton-X for 45mins (3D) at room temperature (RT), followed by rinses with tris buffered saline (TBS). The samples were blocked by 5% donkey serum (DS) overnight at 4 °C, followed by TBS rinses. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight with the samples diluted with 0.5% DS at 1:400 for 2D and 1:300 for 3D. The primary antibodies utilized in this work are as listed: iNOS (Rabbit Anti-Mouse polyclonal antibody; Cat. PA3-030A; Invitrogen, Waltham, MA); Arg-1 (Mouse Anti-Mouse monoclonal antibody; Cat. 66129-1-1 g; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL). Rinses occurred 6 times in 0.01% Tween in TBS for 20 mins (2D) or 90-120 mins (3D), except the last rinse being in TBS only. All samples were then incubated in secondary antibodies at 1:200 for 2D and 1:100 for 3D, and overnight at 4 °C. The secondary antibodies used were: Alexa Fluor 555 Donkey Anti-Rabbit for iNOS (Cat. PIA32794; Thermofisher, Waltham, MA); Alexa Fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Mouse for Arg-1 (Cat. A-21202; Thermofisher, Waltham, MA). This was followed by a 2 h long rinse in TBS. Finally, cell nuclei were stained with 2 μM DAPI (Cat. 10236276001; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by two rinses with TBS for 5mins each.

Imaging and Image Analysis

Images were captured on the BC43 Benchtop Confocal Microscope (Andor), and inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse Ti2. The same exposure time and gain was used to image samples within the same group. For example, for all YIGSR treated M0 macrophages, the same exposure and gain settings were applied. All images were analyzed to quantify mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of iNOS+ or Arg-1+ cells masked over total DAPI+ cells. The violin charts represent means of the MFI of an entire well for iNOS+ or Arg-1+ cells.

Human 2D and 3D studies were analyzed by DAPI+ cells and iNOS+ cells. The images from 2D human studies were imported as overlays of the blue and red channels. The split channel function was utilized to split each channel for further quantification of DAPI+ cell count and iNOS+ MFI. For 3D PEG-YIGSR, images were captured as Z-stacks with a range of 100 µm and a 20 µm step count. Individual slices of each sample were imported into ImageJ, and a Z-projection image was created combining the slices for each channel. After obtaining a Z-project image, both the red (iNOS) and blue (DAPI) channel images were merged into a single file for overlay representative images. MFI was then quantified by assessing iNOS+ cells per total DAPI+ cells. Finally, all graphs were made with MFI values (considered as means). All experiments had 3 biological replicates and 3 technical replicates.

Cytokines and Chemokines Assessment by Luminex Multiplex Array System

Cell culture supernatants were harvested as described above to assess secreted cytokines/chemokines by macrophages in response to YIGSR treatment. The human cytokine magnetic 25-plex panel (Cat. LHC0009M, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for measuring cytokine/chemokine levels according to manufacturer’s instructions. The panel allowed for quantitative determination of the following analytes: IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-2R, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p40/p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, TNFα, IFNα, IFNγ, GM-CSF, MIP-1α (CCL-3), MIP-1β (CCL-4), IP-10 (CXCL-10), MIG (CXCL-9), Eotaxin (CCL-11), RANTES (CCL-5), and MCP-1 (CCL-2). Additionally, the murine cytokine 26-plex panel (Cat. EPXR260-26088-901) was also used to account for species differences. The analytes in this panel were as follows: GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-18, TNFα, IL-9, IL-10, IL-17A, IL-22, IL-23, IL-27, Eotaxin (CCL11), GRO alpha (CXCL1), IP-10 (CXCL10), MCP-1 (CCL2), MCP-3 (CCL7), MIP-1α (CCL3), MIP-1β (CCL4), MIP-2, and RANTES (CCL5). Analysis and quantification was performed on a Magpix system (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX). The concentration values with respect to the standards were calculated on ThermoFisher’s ProCarta Plex application. The concentration values for each analyte were imported into Graphpad Prism for further statistical quantification. Only the analytes with detected levels have been included in the results and discussion.

Total Protein Release Assay

Total protein secretion of macrophages with YIGSR treatment was assessed by a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA; Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit #23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The groups were M0, M1, and M2 macrophages with 0 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, and 8 mM YIGSR treatment (n = 3 for each group). The cell culture supernatant was collected at 48 h post YIGSR treatment and used as the BCA sample. Cell culture media was used as a calibration standard. Collected supernatant was frozen in – 80 °C until BCA could be conducted. Following manufacturer’s instructions, the absorbance from the 96 well plate was read at 562 nm using a BioTek Synergy HT plate reader.

Statistical Analysis

Images were assessed for statistical quantification using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was obtained using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc comparison tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Considering the differences in cell numbers positively expressing iNOS, and just overall cell count differences between some groups, unequal variances may be assumed. Brown–Forsythe and Welch ANOVA correction tests on all experiments assuming non-equal SDs were performed to account for these differences. The mean of each column was compared to the mean of every other column. Games-Howell post-hoc comparison was used since n > 50 per group. The results for one-way or two-way ANOVAs and Brown-Forsythe and Welch correction tests were the same. Therefore, the statistical results reported in the manuscript are from one-way or two-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons tests.

Results

The ECM’s regulatory roles in orchestrating macrophage cell signaling and function continue to be of interest in determining macrophage-ECM interactions. This work investigates the role of laminin-derived peptide, YIGSR, in governing macrophage function at different concentrations. Studies were performed to assess the impact of YIGSR on murine and human macrophages at various concentrations in 2D and 3D via immunostaining techniques and protein secretion.

YIGSR Dose Response in 2D

Prior to this work, YIGSR was speculated to enhance adhesion on other cell types. YIGSR was also demonstrated to increase inflammation by promoting production of inflammatory cytokines, potentially making macrophages pro-inflammatory [36, 37, 48]. Assessing YIGSR response on macrophages will identify how the laminin-derived sequence affects the inflammatory profile of macrophages.

A dose response experiment was conducted to assess the role of YIGSR across different macrophage activation states or phenotypes using three concentrations of YIGSR. The concentrations were chosen in range of reported concentrations in the literature and included 0 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, and 8 mM [44, 45, 48]. Initially, Raw 264.7 murine macrophage cell line was used to identify if YIGSR causes alterations in macrophages (Fig. 1). The M1 macrophage marker iNOS was used for immunostaining of macrophages and MFI was used to quantify iNOS expression.

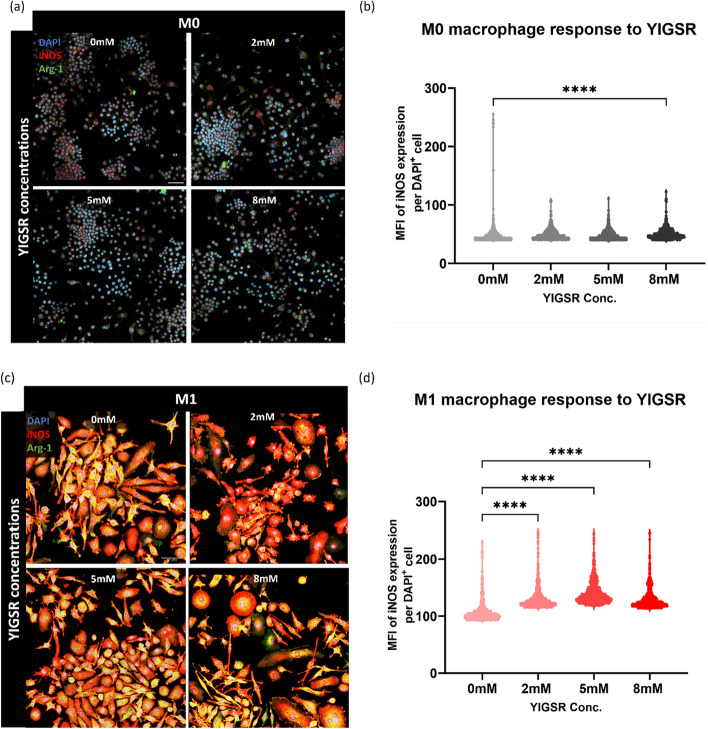

Fig. 1.

YIGSR treatment at 48 h increases iNOS expression in M1 murine macrophages at all concentrations. a Representative images of M0 macrophages exposed to 0 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM, and 8 mM YIGSR. DAPI (blue) is the nuclei marker, iNOS (red) is the M1 marker, and Arg-1 (green) is the M2 marker. b Quantification of iNOS expression via MFI of each cell at various concentrations of YIGSR. Each dot in the volcano plot is a cell that is positively expressing iNOS, therefore number of dots may vary between volcano plots. c Representative images of M1 macrophages treated with various YIGSR concentrations. d MFI for iNOS positive cells at each YIGSR concentration. Images were captured at 40X magnification. (n = 4) (Scale = 50 µm). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests were performed for statistical significance quantification. ****p < 0.0001.

YIGSR treatment induced a significant increase in iNOS expression for both M0 (Fig. 1a, b) and M1 (Fig. 1c, d) macrophages. In M0 macrophages, the highest iNOS expression ws observed with 8 mM YIGSR treatment [Mean (M) = 50.75, Standard deviation (S.D.) = 9.62], with 2 mM YIGSR causing the second largest increase in iNOS (M = 49.21, S.D. = 8.38) compared to control (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, 5 mM YIGSR slightly reduced iNOS expression (M = 48.07, S.D. = 7.68). Although iNOS expression is not expected with M0 macrophages, the trends imply that YIGSR treatment may mildly increase iNOS expression in M0 macrophages. YIGSR treatment displays a concentration-dependent response in M0 macrophages. For the M2 stimulated macrophages, Arginase−1 (Arg-1) expression was low in all treatment groups with YIGSR treatment making no difference in expression levels (Fig. S1).

All concentrations of YIGSR increased iNOS expression for M1 macrophages (Fig. 1c). With no YIGSR treatment, M1 iNOS expression was lowest (M = 106.3, S.D. = 15.40). An incremental increase was observed with 2 mM YIGSR (M = 130, S.D. = 17.52), and 5 mM YIGSR (M = 140.2, S.D. = 18.59). The concentration of 8 mM YIGSR reduced iNOS expression (M = 129.2, S.D. = 16.43) when compared to 2 mM and 5 mM, while still keeping iNOS levels higher than no peptide treatment in M1 macrophages (Fig. 1d). iNOS expression peaked at 5 mM, and dropped at 8 mM for M1 macrophages. This drop in iNOS expression alludes to the sensitivity of the peptide, highlighting a concentration-dependent response of macrophages to YIGSR.

To investigate the effects of YIGSR on human macrophages, we exposed primary human monocyte-derived macrophages to YIGSR at the same concentrations as murine macrophages. The MFI is reported as iNOS+ cells per total DAPI+ cells and each dot in the violin plot is a cell positively expressing iNOS. For both M0 and M1 macrophage phenotypic states, YIGSR treatment caused the highest increase in iNOS expression at 2 mM (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

YIGSR treatment at 48 h increases iNOS expression in M0 and M1 human macrophages. a Representative images of M0 macrophages exposed to 0 mM, 2 mM, 5 mM , and 8 mM YIGSR. DAPI (blue) is the nuclei marker and iNOS (red) is the M1 marker. b Quantification of iNOS expression via MFI of each cell at various concentrations of YIGSR. Each dot in the volcano plot is a cell that is positively expressing iNOS, therefore number of dots may vary between volcano plots. c Representative images of M1 macrophages treated with various YIGSR concentrations. YIGSR affects cell count hence fewer cells are visibile at 8 mM. d MFI for iNOS positive cells at each YIGSR concentration. Images were captured at 20X magnification. (n = 3) (Scale = 150 µm). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests were performed for statistical significance quantification. *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001

For M0 macrophages (Fig. 2a), the lowest iNOS expression was with no YIGSR (M = 49.60, S.D. = 6.15) and the highest iNOS expression was with 2 mM YIGSR (M = 58.64, S.D. = 7.59). There was a spike in YIGSR treatment at 2 mM and 8 mM (M = 57.82, S.D. = 6.62) with a drop observed with 5 mM YIGSR (M = 53.90, S.D. = 6.2) (Fig. 2b).

For M1 macrophages (Fig. 2c), the highest iNOS expression was on exposure to 2 mM YIGSR (M = 122.8, S.D. = 14.19), followed by 8 mM (M = 117.8, S.D. = 16.52). The lowest iNOS expression was induced by the control M1 (M = 111.1, S.D. = 13.15) and 5 mM group (M = 110.9, S.D. = 16.08) with no statistical difference between the two (Fig. 2d). Similar to M0 human macrophages, the largest increase in iNOS expression was with 2 mM YIGSR.

It is noteworthy that the cell counts, as quantified by DAPI+ cells, were reduced with 8 mM YIGSR treatment for both M0 and M1 macrophages (Fig. S2). The lower DAPI counts are emphasized in the violin plots as fewer dots indicate a lower count of iNOS+ cells, despite the same seeding density across all groups. M0 macrophage count reduced from 646 with no YIGSR treatment to 149 with 8 mM YIGSR, and M1 macrophage DAPI count reduced from 338 to 90 with 8 mM YIGSR treatment. Lower DAPI+ cells with 8 mM YIGSR could indicate the peptide’s role in competing with adsorbed protein adhesion in 2D cultures. To investigate viability of cells with increasing YIGSR concentration, a live/dead assay was also performed (Fig. S3). No dead cells were found but 8 mM YIGSR treatment reduced overall numbers of live cells.

Assessing Macrophage Response to YIGSR in 3D PEG Hydrogels

Two hydrogels were used in this work: a control hydrogel with PEGDA and PEG-RGDS, and an experimental hydrogel with either 5 mM PEG-YIGSR or 10 mM PEG-YIGSR included with the aforementioned PEG macromers. Human macrophages were encapsulated in both the control hydrogels and the experimental hydrogels (Fig. 3). Based on the 2D results, we expect PEG-YIGSR to increase iNOS expression due to increased exposure time of macrophages encapsulated in the hydrogel.

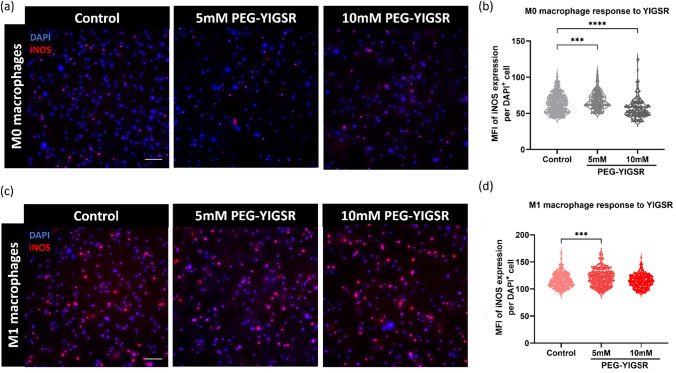

Fig. 3.

PEG-YIGSR (5 mM) increases iNOS expression in M0 and M1 human macrophages. a Representative images of encapsulated M0 macrophages in 5 mM PEG-YIGSR and 10 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels. b Quantification of iNOS expression demonstrated an increase with 5 mM and 10 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels compared to control hydrogels. c Representative images of encapsulated M1 macrophages in control, 5 mM, and 10 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels. d MFI for iNOS positive cells for each hydrogel demonstrates that 5 mM PEG-YIGSR increased iNOS compared to control. Images were captured at 20X magnification. (n = 4) (Scale = 150 µm). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc tests were performed for statistical significance quantification. ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

In M0 encapsulated macrophages (Fig. 3a, b), iNOS expression was higher in PEG-YIGSR hydrogels compared to control. Specifically, PEG-YIGSR hydrogels at 5 mM caused the largest increase in expression of iNOS for M0 macrophages (M = 30.76, S.D. = 2.23) compared to 10 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels exhibiting only a slight increase (M = 29.51, S.D. = 1.52). The control hydrogels demonstrated the lowest iNOS expression (M = 28.58, S.D. = 0.51) (Fig. 3b). The presence of immobilized YIGSR trended to increase iNOS expression in M0 macrophages.

For M1 stimulated macrophages encapsulated within the hydrogels (Fig. 3c), 5 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels caused the largest increase in iNOS for M1 (M = 120.2, S.D. = 15). There were no statistically significant differences observed for M1 macrophages encapsulated in control and 10 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels (Fig. 3d). Because higher iNOS levels were demonstrated in 5 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels than 10 mM PEG-YIGSR, these results bolster the findings from our 2D studies in which there is a concentration-dependent response of macrophages to YIGSR. Higher iNOS expression is seen at lower concentrations of YIGSR whereas the opposite is observed at higher concentrations of YIGSR.

Encapsulation in YIGSR hydrogels did cause differences in DAPI+ cell counts (Fig. S4). In M1 macrophages, both 5 mM and 10 mM PEG-YIGSR reduced cell counts compared to control hydrogels, but in M0 macrophages, the differences were not statistically significant.

To understand the bidirectional interactions between adhesive peptide RGDS and YIGSR on human M1 macrophages, an experiment was conducted with varying RGDS concentrations (0 mM, 1 mM, 3.5 mM, 5 mM) (Fig. S5). Without YIGSR, varying RGDS concentrations demonstrated no statistical differences in iNOS expression of M1 macrophages (Fig. S5a, b). With the addition of 5 mM PEG-YIGSR to the hydrogel, iNOS concentration in M1 macrophages changed depending on RGDS concentration (Fig. S5c, d). The highest iNOS levels were observed in 3.5 mM RGDS + 5 mM YIGSR hydrogels (M = 151.6, S.D. = 57.47). This finding is consistent with Fig. 3d where the experimental 3.5 mM RGDS + 5 mM YIGSR hydrogel induced the highest iNOS expression. iNOS expression fluctuated at other concentrations of RGDS. No significant differences were seen when a scrambled form of YIGSR was used regardless of RGDS concentration (Fig. S5e, f).

The number of DAPI+ cells on the other hand did not follow the same trends seen in iNOS expression (Fig. S6). DAPI+ cells represent cells attached in hydrogels [49]. The highest number of DAPI+ cells was with 3.5 mM RGDS (78), affirming that this is an apt concentration for macrophage adhesion. However, DAPI+ cells decreased (29) with 5 mM RGDS and 5 mM YIGSR (Fig. S6a). Using the YIGSR scramble peptide (YSRIG) significantly reduced DAPI+ cells with 5 mM RGDS (Fig. S6b). This reduction is consistent within both YIGSR and YSRIG peptides.

YIGSR Increases Secretion of Inflammatory Chemokines and Cytokines in Human Macrophages

To understand the secretomic profile of human macrophages in response to different concentrations of YIGSR, a Luminex assay was performed that included several chemokines and cytokines (Figs. 4, 5). Changes in total cell count did not affect total protein secreted across all groups as verified by a BCA assay (Fig. S7). Additionally, to account for species differences, secreted cytokines and chemokines were also assessed for murine macrophages (Fig. S8, S9) (discussed in the Supplement and later in the Discussion).

Fig. 4.

YIGSR treatment caused a significant change in chemokine production in human macrophages. The chemokines demonstrated are for each macrophage phenotypic state, and for all concentrations of YIGSR tested. The chemokines displayed are as follows: a IL-1RA, b MIP-1α, c MIP-1β, d IL-8, e RANTES, and f MCP-1. Statistical significance was quantified by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

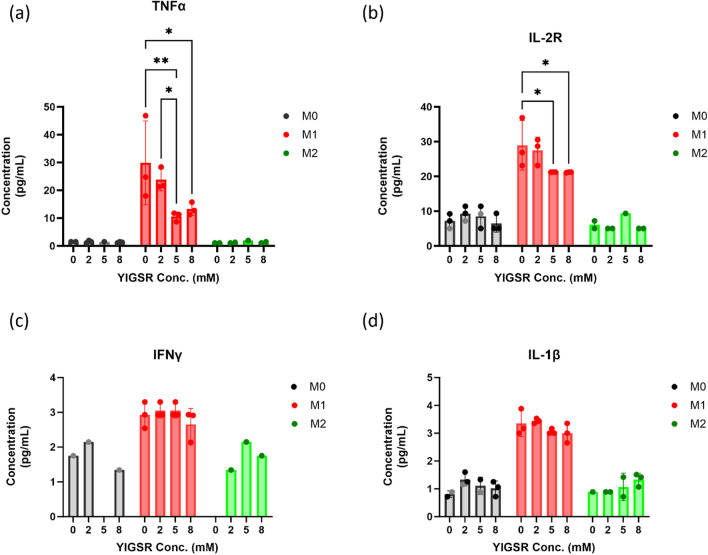

Fig. 5.

YIGSR treatment affected cytokine production in human macrophages. The cytokines demonstrated are for each macrophage phenotypic state, and for all concentrations of YIGSR tested. The cytokines displayed are as follows: a TNFα, b IL-2R, c IFNγ, d IL-1β. Statistical significance was quantified by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. (n = 3). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Concentrations of IL-1RA decreased with increasing YIGSR concentration in all macrophage phenotypes (Fig. 4a). In M0 macrophages, IL-1RA secretion reduced significantly from 2074 pg/mL (S.D. = 827.8) with no peptide treatment to 892.9 pg/mL (S.D. = 30.10) with 8 mM YIGSR. For M1 macrophages, IL-1RA concentration reduced from 2332 pg/mL (S.D. = 392) to 1710 pg/mL (S.D. = 359.6) with 2 mM, 1671 pg/mL (S.D. = 107.9) with 8 mM YIGSR, and lowest concentrations were 1167 pg/mL (S.D. = 243) with 5 mM YIGSR treatment. The concentration-dependent response as seen with iNOS quantification was also observed with chemokine secretion with YIGSR treatment in M1 macrophages. M2 macrophages demonstrate a similar consistent decline of IL-1RA secretion as M1 macrophages, the highest concentration being with no peptide treatment (M = 2997 pg/mL, S.D. = 596) to the lowest concentrations being similar between 5 mM (M = 1295 pg/mL, S.D. = 191.7) and 8 mM (M = 1340 pg/mL, S.D. = 227) treatment groups. Overall, YIGSR treatment did not posit any significant differences between the 2 mM and 0 mM concentrations. Across all macrophage phenotypes, the trends between 0 and 2 mM YIGSR were comparable while the trends between 5 and 8 mM YIGSR were comparable.

Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)− 1α and MIP-1β had significantly different concentration levels across various YIGSR concentrations as well. MIP-1α and MIP-1β are diverging chemokines with the same receptor. MIP-1α stimulates the production of TNFα in inflammatory environments, for example in breast cancer patients [50]. The overall secretion of MIP-1α was higher than that of MIP-1β following YIGSR treatment. The lowest MIP-1α secretion was with 5 mM YIGSR (M = 1576 pg/mL, S.D. = 177.3) (Fig. 4b). The untreated M1 (M = 3562 pg/mL, S.D. = 1875) and 2 mM M1 (M = 2838 pg/mL, S.D. = 480.4) concentrations were similar in having the highest MIP-1α secretion levels. While 8 mM YIGSR was slightly higher than 5 mM although there was no statistical difference.

Trends observed in MIP-1β levels are similar to MIP-1α. At lower concentrations of YIGSR, secretion of both MIP-1α and MIP-1β is higher than at higher concentrations of YIGSR. For MIP-1β, the lowest production is with 5 mM YIGSR (M = 1182 pg/mL, S.D. = 194.8) and similar to MIP-1α, the untreated (M = 1940 pg/mL, S.D. = 787.3) and 2 mM (M = 1806 pg/mL, S.D. = 315) groups have similar levels secreted (Fig. 4c). For both MIP-1α and MIP-1β, secretion levels at 8 mM YIGSR were slightly higher than 5 mM YIGSR treatment. This could indicate a plateau phase after exceeding a certain threshold for a biological change in MIP-1 α, β production. The concentration-dependent response with YIGSR treatment is evident through all chemokine secretions.

IL-8 secretion was absent in M1 macrophages while being abundant with YIGSR treatment in M0 and M2 macrophages (Fig. 4d). IL-8 or CXCL8 is a major chemokine for the migration of monocytes/macrophages into inflammation sites. IL-8 production was absent in M1 macrophages. IL-8 production by both M0 and M2 macrophages was highest with 8 mM YIGSR treatment. For M0, IL-8 levels increased from 255.4 pg/mL (S.D. = 237.2) to 3883 pg/mL (S.D. = 1558). For M2, no peptide treatment caused a secretion of 339.6 pg/mL for IL-8 whereas, 8 mM YIGSR treatment led to 4705 pg/mL secretion of IL-8 in M2 macrophages. At 5 mM YIGSR concentration, the chemokine levels reduced when compared to 2 mM and 8 mM YIGSR The lowest IL-8 levels were with the no peptide treated M0, M1, and M2 macrophages.

Regulated upon activation in normal T cells expressed and secreted (RANTES) chemokine also demonstrated the same concentration-dependent distribution wherein secretion levels were high with 2 mM (M = 84.16 pg/mL, S.D. = 19.87) and 8 mM (M = 79.57 pg/mL, S.D. = 11.48) YIGSR but lower with 5 mM YIGSR (M = 37.18 pg/mL, S.D. = 5.09) (Fig. 4e). In general, YIGSR reduced RANTES levels compared to no peptide treatment (M = 90.06 pg/mL, S.D. = 36.59) in M1. MCP-1 and RANTES share the same receptor and are critical mediators in the evolution of inflammatory reactions. Even though YIGSR treatment did not significantly alter MCP-1 levels, the trends demonstrate that 2 mM YIGSR caused the highest secretion and 8 mM YIGSR caused the lowest secretion (Fig. 4f).

Cytokine levels were drastically lower than chemokine concentrations in the supernatant with YIGSR treatment across all macrophage phenotypes. All cytokines displayed in Fig. 5 have pro-inflammatory functions.

Although overall TNFα production was low, the 2 mM (M = 23.81 pg/mL, S.D. = 3.97) YIGSR concentration was similar to M1 with no peptide treatment (M = 29.89 pg/mL, S.D. = 15.08) (Fig. 5a). The lower levels secreted at higher YIGSR concentrations further bolster the concentration-dependence as seen previously with chemokines.

IL-2R is a receptor for IL-2 and promotes the biological function of IL-2. IL-2R secretion with no peptide treatment (28.96 pg/mL, S.D. = 7.12) was similar to 2 mM YIGSR (M = 27.47 pg/mL, S.D. = 3.87) (Fig. 5b). Albeit significantly reduced, similar levels were demonstrated with 5 mM (21.23 pg/mL, S.D. = 0.02) and 8 mM (M = 21.19, S.D. = 0.09) YIGSR treatment.

IFNγ and IL-1β levels were very low across all human macrophage phenotypes compared to other cytokines (Fig. 5c, d). M1 macrophages had the highest overall secretion of both cytokines compared to M0 or M2 although YIGSR treatment did not cause statistically significant differences between different concentrations. However, the lowest concentration of IFNγ was in the 8 mM YIGSR in the M1 group. These trends are consistent with chemokine secretions where lower concentrations of YIGSR increase their production and higher concentrations of YIGSR hinder the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

Discussion

Laminin is essential to the functioning of the basement membrane including acting as a mechanosensitive cellular anchorage site, a physical barrier, and a reservoir of cytokines and chemokines [51]. Varied sequences or fragments derived from laminin have been shown to direct biological functions. For example, our previous work demonstrated that laminin-derived peptide, IKVAV, had a mild reduction in iNOS expression in M1 macrophages [25]. IKVAV treatment also reduced expression of pro-inflammatory markers via gene expression studies. When it was first identified, the laminin β-chain derived peptide YIGSR was presented as an anti-tumorigenic peptide [36, 51, 52]. However, YIGSR’s impact on macrophage phenotype modulation has been less investigated. Monocytes/Macrophages interact with the ECM and traverse the basement membrane to enter or exit blood vessels and the interstitial matrix, thereby migrating to sites of inflammation or injuries [53–55]. Understanding laminin-derived peptide YIGSR and macrophage interactions is important to bridge the gap between fundamental biological learnings of ECM ligands and macrophage regulation by the ECM.

Rationale for YIGSR Concentration

Several studies utilized YIGSR in innovative ways such as by surface modification of drug-loaded nanospheres, conjugation with polymers, and encapsulating in nanoparticles [56–58]. For example, YIGSR was used as a potent chemotherapeutic in the context of tumor prevention and inhibition of metastases in cancers of lung and breast. Common YIGSR concentrations noted were from 10 µM to 25 mM [44, 45, 48, 44–45, 59]. We discerned an optimal range to be 0–8 mM for 2D; and 0–10 mM for 3D based on YIGSR modulation in in vitro platforms of other cell types.

2D Effects of YISGR

To decipher the effect of YIGSR on macrophage function, we investigate Raw 264.7 response to YIGSR in 2D. For M0 macrophages, 8 mM YIGSR increases iNOS inflammatory skewing the most. For M1 macrophages, 5 mM YIGSR causes the largest increase in iNOS expression. M0 macrophages present a concentration-dependent response to YIGSR as there was a reduction in iNOS MFI at 5 mM but iNOS was higher at 8 and 2 mM. A concentration-dependent effect can also be noted with M1 iNOS expression in murine macrophages with the largest iNOS MFI being at 5 mM YIGSR. Similarly, human monocyte-derived macrophages present a concentration-dependent response to YIGSR treatment for both M0 and M1 macrophages. A spike in iNOS MFI is noted at 2 mM followed by 8 mM YIGSR, whereas a drop is observed with 5 mM YIGSR. YIGSR increasing iNOS expression in M1 but reducing it in M0 highlights the importance of concentration and phenotypic state.

Owing to the differences in the immunological profile of mice and humans, a trivial difference in response with varied YIGSR concentrations was expected [60]. For both M0 and M1 human macrophages, 2 mM YIGSR causes the largest iNOS expression, and 5 mM has the least effect on iNOS. Whereas for M1 murine macrophages, 5 mM YIGSR has the largest number of iNOS+ cells and this is comparable with 2 mM YIGSR. The responses recorded through immunostaining are not significantly different between murine and human macrophages. Sensitivity varies between YIGSR concentration and macrophage phenotype between the two species [61].

Via secretome analysis we found that YIGSR regulates chemokine and cytokine secretion of human monocyte-derived macrophages. The interactions between macrophages and YIGSR are divergent and based on concentrations. Specifically, the chemokines affected with YIGSR treatment are IL-1RA, IL-8, RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β. These chemokine responses suggest that YIGSR influences the chemotaxis and migratory behavior of macrophages. YIGSR is potentially affecting the signaling for recruitment of immune cells by altering chemokines secreted by macrophages.

Specifically, elevated levels of chemokines such as RANTES and MCP-1 are involved in the recruitment of immune cells to sites of inflammation [62, 63]. RANTES and MCP-1 attract mainly T lymphocytes and mononuclear phagocytes, respectively [64]. RANTES (CCL5) can contribute to the activation of monocytes during inflammatory responses resulting in greater cell aggregation, activation, and the release of specific pro-inflammatory products [62, 65]. RANTES is most reduced by 5 mM YIGSR. Reduced levels of RANTES indicate reduced leukocyte infiltration. The 2 mM and 8 mM YIGSR imbue higher levels of RANTES than 5 mM, showcasing the impact of YIGSR on dictating migration signaling in human macrophages.

MCP-1 is a critical mediator in the evolution of inflammatory reaction [63, 64, 66]. MCP-1 (CCL2) has been shown to induce tumoricidal macrophages on LPS activation using the monocytic cell line THP-1 [67]. Blood-derived monocytes secrete MCP-1 to regulate tumor progression [67]. Previous studies have highlighted how overexpression of MCP-1 induces cell invasion of tumor-associated macrophages and metastasis in breast cancer [60–62, 68]. We surmise that lower levels of MCP-1 indicate lower recruitment of macrophages. In our data, the 5 mM YIGSR treatment in M1 macrophages reduces MCP-1 levels similar to that of M0 and M2 macrophages.

Additionally, MIP-1α and MCP-1 are considered pro-inflammatory and anti-wound healing chemokines for their roles are predominantly recruiting macrophages and inducing other pro-inflammatory cytokines [50, 69–71]. In our work, we found that MIP-1α and MIP-1β exhibit similar trends to IL-1RA and MCP-1, reduced with 5 mM and 8 mM YIGSR, whilst increasing with 2 mM YIGSR. Higher levels of MIP-1α and MIP-1β also indicate a more inflammatory environment [72]. MIP-1α and MIP-1β exposed to 5 mM YIGSR see the lowest secretion of both chemokines and 2 mM YIGSR secretes the largest amounts.

Interestingly, the trends seen in secreted factors for human macrophages are different than trends presented by murine macrophages, owing to species differences. For example, RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were also significantly affected with YIGSR treatment in murine macrophages but displayed different trends. Instead of a concentration-dependent response, murine macrophages reduced RANTES levels with increasing YIGSR concentration in macrophages. Similarly, both MIP-1α and MIP-1β, retain inflammatory function at 2 mM YIGSR in human macrophages. However, in murine macrophages, both chemokines consistently reduce with increasing YIGSR concentrations. MIP-1α and MIP-1β are also implicated in generating tumoricidal monocytes [50]. The overall increased secretion of both analytes compared to others bolsters YIGSR’s role as a peptide impeding tumor growth.

Species differences are also evident in other cytokines. YIGSR treatment caused no significant differences for TNFα secretion in murine M1 macrophages. However, TNFα secretion was significantly impacted by YIGSR treatment in human macrophages. Similarly, in human macrophages, some secretion levels of IL-1β were observed in M1 and M2 macrophages, whereas in murine macrophages overall secretion is reduced. Conversely, for IFNγ human macrophages exhibit lower secretion levels while primary murine macrophages display higher secretion levels. The results for murine cytokines and chemokines are discussed further in the Supplementary information (Figs. S8, S9).

IL-1RA clinically occurs post-injury during inflammation to improve healing. Elevated levels of IL-1RA are associated with reducing inflammatory cytokine levels in humans [73]. Administration of IL-1RA stimulates M2 activation. M2 activation can in turn promote inflammatory cytokine secretion (IL-1β, IL-6) and angiogenesis. Lower levels of IL-1RA with YIGSR could indicate increased inflammatory cytokine production. At higher concentrations (5 mM, 8 mM) of YIGSR, IL-1RA secreted levels are lower than at lower concentrations (0 mM, 2 mM) of YIGSR. Therefore, it can be implied that at 2 mM and 5 mM, YIGSR is increasing inflammation in M0, M1, and M2 macrophages.

On the contrary, IL-8 or CXCL8 is an inflammatory chemokine that is mainly produced by tumor-associated macrophages [74, 75]. The absence of IL-8 production in M1 macrophages is in line with previous studies [76]. However, the increase in IL-8 production in M0 and M2 macrophages indicates skewing them towards a more inflammatory phenotype. These results suggest multiple functions of YIGSR in combination with macrophages. One function is the promotion of angiogenesis in inflammatory environments, the others are increasing inflammation, and governing chemokine production. YIGSR seems to be preventing chemotaxis while also promoting the release of inflammatory cytokines. This is bolstered by literature of YIGSR having an inhibitory effect on tumor growth [51, 52, 57, 59].

TNFα and IL-8 are complementary in the induction of angiogenesis [76]. The complementary nature of IL-8 and TNFα is exhibited in Figs. 4 and 5 where IL-8 secretion is present in M0 and M2 macrophages, while TNFα secretion is only present in M1 macrophages. At 2 mM YIGSR both IL-8 and TNFα concentrations are increased. A study showed that upon LPS activation, IL-8 expression was reduced, in line with our findings. However, IL-8 traditionally expressed after phagocytosis, favours pro-inflammatory activity of human macrophages [75]. Therefore, increased levels of IL-8 in M0 and M2 macrophages with YIGSR treatment indicates a more inflammatory phenotype.

IL-2R, a receptor for IL-2, governs the activation state of immune cells and is expressed by activated lymphoid cells [77, 78]. Increased IL-2R secretion in M0 macrophages suggests a skew from inactivated macrophages to activated states. IL-2R progresses cancer by increasing inflammation and infiltration of immune cells [79]. Higher levels of IL-2R in YIGSR treated M1 macrophages indicates increased inflammation. Conversely, IL-2R is also involved in promoting angiogenesis in tumors. M2 macrophages are known to be pro-angiogenic [45]. Even though production is slightly increased, YIGSR treatment does not have a significant effect on IL-2R secretion in M2 macrophages.

Immunostaining experiments for M2 marker Arg-1 were inconclusive, however, through Luminex we can comment on the M2 macrophage response. The M2 macrophage phenotype is characterized by a secreted cytokine profile as follows: IL-12low, IL-10high, IL-1RAhigh, and IL-1βlow [73, 80, 81]. In human macrophages, IL-12 is lowest in the control M2 group. IL-12 secretion increases with increasing concentration of YIGSR. Similarly, IL-1RA in the YIGSR treated groups is not higher than control M2. There was no secretion of IL-10 with YIGSR treatment. Lastly, IL-1β secretion increased with YIGSR treatment. These data may imply that YIGSR treatment prevents the activation of M2 macrophages. Additionally, M2 macrophages from mice exhibit high IL-12(p70) secretion regardless of YIGSR concentration (Fig. S8). IL-12(p70) is usually induced by inflammatory stimulation [82]. The trends seen in human and murine M2 macrophages may indicate that YIGSR is promoting a pro-inflammatory function in a concentration-dependent manner. On the other hand, IL-27 induces anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects [83]. With increasing YIGSR concentration, M1 murine macrophages display incrementally lower secretion levels of IL-27, likely increasing their pro-inflammatory function. With M2 macrophages, the concentration-dependent response is highlighted as 2 mM YIGSR has the highest IL-27 secretion while the other concentrations are comparable to control. These trends indicate YIGSR’s ability to reduce anti-inflammatory function in macrophages.

YIGSR has been shown to have no changes in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) expression for macrophages [40]. MMP-9, a tissue remodelling enzyme, is considered an indicator of the M2 phenotype. Our results are in line with findings in literature, wherein YIGSR does not have a significant impact on M2 macrophages. Additionally, M2 associated cytokines, including IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, are minimally detected in the secretome with YIGSR treatment. This further indicates an inflammatory phenotypic skewing. The increase of inflammatory markers with YIGSR emphasizes the role of YIGSR in promoting the M1 phenotype.

Our results demonstrate that YIGSR has a larger impact on chemokine production than cytokines for macrophages. For chemokines including RANTES and IL-1RA, production is increased in 2 mM YIGSR for all macrophage phenotypes, and reduced with 5 mM and 8 mM YIGSR. Cytokines like TNFα and IL-2R also display similar trends. For most chemokines and cytokines, 2 mM YIGSR is increasing or maintaining the levels of M1 secretion compared to control. While 5 mM and 8 mM YIGSR are reducing chemokine production in M1 group. YIGSR has disparate responses depending on the concentration of peptide, as well as phenotypic state of macrophages. Species differences between murine and human macrophages are also observed in cytokine and chemokine secretion in response to YIGSR treatment. These differences could further be attributed to the sources of macrophages. Since human macrophages were from peripheral blood and mouse macrophages were from bone marrow (precursors that upon maturation migrate out of the bone marrow and enter blood circulation), the secreted protein levels could be different [84–86].

3D Effects of YIGSR

Engineered hydrogel systems can advance understanding of cell-matrix interactions by allowing precise tuning of the biochemical and biophysical properties [87–90]. For example, Brown et al. used YIGSR with another laminin-derived peptide A99 in a fibrinogen hydrogel and saw no changes in M1 macrophages of male mice [39]. Herein, the presence of whole fibrinogen and A99 are likely affecting macrophage function. Another study utilized PEG-YIGSR vascular grafts to generate nitric oxide that allowed for the transition of macrophages to the M2 phenotype [91].

In our efforts to isolate and understand the role of YIGSR on macrophages, we conjugated YIGSR with PEG to design hydrogels. The PEG-YIGSR hydrogels can house macrophages and enable assessment of macrophage response to immobilized YIGSR. The 5 mM PEG-YIGSR hydrogels elicited the largest increase in iNOS MFI for both M0 and M1 macrophages. Conversely, 10 mM PEG-YIGSR reduced iNOS MFI, aligning with the trend seen in the 2D studies. Despite the differences in macrophage response depending on the concentration, there is still a concentration-dependent effect of YIGSR where lower concentrations increase iNOS, and higher concentrations reduce iNOS.

YIGSR also affects adhesion of human macrophages in 2D and 3D. YIGSR’s role in adhesion is weaker compared to whole laminin. For example, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) protein was reduced by 50% in cardiac cells cultured on YIGSR peptide compared to whole laminin [92]. The combination of RGD and YIGSR also lowered expression of FAKs which is a downstream effector of integrin signaling. The difference in macrophage response depending on YIGSR concentration levels could be attributed to limited adhesion sites in the hydrogel (3D) as compared to tissue-culture plastic (2D). Macrophages have been shown to adhere normally to fibronectin and tissue culture plastic, but not as well with laminin or laminin-derived peptides. YIGSR’s impact on reducing cell count with increasing concentration is observed through DAPI quantification as well as the live/dead assay (Figs. S2, S3, S6). While all cells were alive with each YIGSR concentration, 8 mM causing the lowest live cells could insinuate YIGSR’s role in impacting macrophage adhesion. The live/dead assay assesses adherent cells only. Since we are targeting integrins, cell adhesion is impacted and can be commented on through the live/dead assay. Additionally, YIGSR is known to be a common binding site for integrins α5β1 and α4β1, both of which are also RGDS binding integrins [43, 52, 93–95]. Hence, the reduction in DAPI counts and live cells could insinuate competitive integrin-ligand binding employed by macrophages altering their adhesion [44]. Macrophages can bind and migrate on the endogenous laminin protein in vitro [42, 96]. Several studies have also demonstrated the use of YIGSR as a cell-adhesive ligand [92, 94, 97]. However, our results showcase a concentration-dependent response with YIGSR led adhesion across macrophage phenotypes.

To tease out the bidirectional interactions of RGDS and YIGSR on encapsulated M1 macrophages, a study with varying RGDS concentrations was conducted (Fig. S5). Without YIGSR, no differences in iNOS expression were observed despite the RGDS concentration. Adding YIGSR caused alterations in iNOS expression indicating the pro-inflammatory effect of YIGSR. Specifically, the hydrogel combination that elicited the iNOS expression (3.5 mM RGDS + 5 mM YIGSR) (Fig. 3) was also true with the competitive binding study in Fig. S5. This could indicate that at 3.5 mM RGDS, the integrins binding with RGDS play crucial roles in M1 polarization mechanisms. Since no significant differences in iNOS expression were observed without YIGSR peptide or with YIGSR scramble, the contribution to iNOS expression can be attributed to YIGSR.

Through our experiments, we see a concentration-dependent response to YIGSR. Depending on the concentration of YIGSR and method of exposure, i.e. 2D or 3D, YIGSR also dictates macrophage inflammation profile. In 2D and 3D lower levels of YIGSR cause the largest increase in iNOS expression. For 2D studies in human macrophages, 2 mM YIGSR has the largest iNOS expression whereas for 3D studies, 5 mM PEG-YIGSR has the most impactful iNOS expression in M1 macrophages. Similar trends of concentration-dependence are also noted in secreted proteins including IL-1RA, IL-8, RANTES, TNFα. At 2 mM YIGSR treatment, macrophages promote human inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. These results highlight the distinct biological roles of YIGSR with a concentration-dependent influence on macrophage phenotype. Previous work has established that the effects of laminin on macrophages are time- and dose-dependent [40, 41]. Considering these effects, YIGSR displaying a threshold for inducing a pro-inflammatory phenotype is within the literature available. To understand these mechanisms in greater detail, we suggest blocking specific integrins (α4β1, α5β1, α6β1) as well as performing a study for a longer time duration. It may be that macrophage phenotype shifts with increasing time and depending on YIGSR concentration.

Conclusion

Our study establishes YIGSR as a macrophage manipulating peptide by enhancing inflammation and inflammatory chemokines at lower concentrations. YIGSR plays the opposite role at higher concentrations in all macrophage phenotypic states. YIGSR acts in a concentration-dependent manner on macrophage phenotypes. Not only do peptides from the same ECM protein (laminin) have distinct biological functions like IKVAV reducing inflammation, and YIGSR promoting inflammation, the concentration of each peptide also alters macrophage function based on phenotype. Lower concentrations of YIGSR promoted inflammation in M1 macrophages by both increasing iNOS levels and inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. However, at higher concentrations of YIGSR, the inflammatory effects are muted resulting in reduced iNOS levels and reduced production of inflammatory chemokines/cytokines. While trends of concentration-dependence are retained in murine and human macrophages, some species differences in cytokine/chemokine response were observed with YIGSR. These alterations in macrophage function with varied YIGSR concentrations can be used to better understand laminin’s influence on macrophages clinically. Our work demonstrates the usage of YIGSR peptide to modulate macrophage inflammation profile.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the NSF Career Grant #2237741. Under #IRB 2055809-1 through the University of Maryland, College Park Institutional Review Board, the authors purchased human pan monocytes to profile the human macrophage response to YIGSR peptide.

Biographies

Aakanksha Jha

is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Fishcell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. Dr. Jha obtained a Bachelor of Engineering (2018) and Master of Science (2020) degree in biomedical engineering. Being a BME loyal, Dr. Jha received her Ph.D. in biomedical engineering from the University of Florida in 2023. Dr. Jha's work focuses on investigating ECM ligands for their impact on modulating macrophage function. Early in her Ph.D., Dr. Jha also obtained an international patent for her work on designing a biomaterial to reduce macrophage inflammation. Dr. Jha’s Ph.D. work also supported preliminary data for her PI's (Dr. Erika Moore) NSF CAREER award. She has authored multiple papers, and attended several conferences delivering oral presentations and posters. Dr. Jha is passionate about equity in science, translational research, and science communication. Dr. Jha has been recognized for her contributions in science as an international student by the Alec Courtelis International Student Achievement Award at the University of Florida.

Erika Moore

is an Assistant Professor in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland, College Park. She defended her Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering from Duke University in May 2018. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Biomedical Engineering from the Johns Hopkins University in 2013. Her work focuses on understanding the role of macrophage immune cells in tissue repair and regeneration through the design of in vitro preclinical models, spanning age-associated macrophage function, macrophage-vasculitis mediation in lupus, and macrophage integrin ligand interactions within the extracellular matrix. The mission of the Moore lab is to engineer biomaterial models that leverage the regenerative potential of the immune system across health inequities. To execute on this mission, Dr. Moore develops compassionate innovators equipped to transform biomedical research. Recently acknowledged as Forbes 30 Under 30 in the Healthcare category, Dr. Moore’s notable awards include the N.I.H. R35 Maximizing Investigators Research Award, the Lupus Research Alliance Career Development Award, the BMES Rita Schaffer Award, the 3M Non-Tenured Faculty Award and the NSF CAREER Award.

Author Contributions

Aakanksha Jha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Experimental design, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Visualization. Erika Moore: Methodology, Experimental design, Resources, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors Aakanksha Jha, and Erika Moore declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

Cyropreserved human cells were purchased from vendors. No animal subjects were used for this study.

Footnotes

We acknowledge that the polarization state of macrophages is in fact a continuous spectrum as various heterogeneous populations respond to a variety of physiological roles. Due to the multi-spectrum of phenotypes being a niche area of immunological research, we acknowledge and utilize the M1/M2 paradigm to encompass the in vitro states of macrophage activation used in our work, in line with the historical context of the M1/M2 nomenclature for in vitro studies.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kumar, V. Macrophages: The potent immunoregulatory innate immune cells, In: Macrophage Activation, edited by K. H. Bhat, Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2019, 10.5772/intechopen.88013.

- 2.Epelman, S., K. J. Lavine, and G. J. Randolph. Origin and functions of tissue macrophages. Immunity. 41(1):21–35, 2014. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirayama, D., T. Iida, and H. Nakase. The phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017. 10.3390/ijms19010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sreejit, G., A. J. Fleetwood, A. J. Murphy, and P. R. Nagareddy. Origins and diversity of macrophages in health and disease. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 9(12):e1222–e1222, 2020. 10.1002/cti2.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez, F. O., and S. Gordon. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014. 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray, P. J., et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, M. J., et al. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization dynamically adapts to changes in cytokine microenvironments in Cryptococcus neoformans infection. mBio. 2013. 10.1128/mBio.00264-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witherel, C. E., et al. Regulation of extracellular matrix assembly and structure by hybrid M1/M2 macrophages. Biomaterials. 269:120667, 2021. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yue, B. Biology of the extracellular matrix: an overview. J. Glaucoma. 23:S20-23, 2014. 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valentin, J. E., A. M. Stewart-Akers, T. W. Gilbert, and S. F. Badylak. Macrophage participation in the degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A. 15(7):1687–1694, 2009. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huleihel, L., et al. Macrophage phenotype in response to ECM bioscaffolds. Semin. Immunol. 29:2–13, 2017. 10.1016/j.smim.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hynes, R. O., and A. Naba. Overview of the matrisome–an inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4(1):a004903–a004903, 2012. 10.1101/cshperspect.a004903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plow, E. F., T. A. Haas, L. Zhang, J. Loftus, and J. W. Smith. Ligand binding to integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 275(29):21785–21788, 2000. 10.1074/jbc.R000003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes, C. D., T. A. Petrie, and A. J. García. Mixed extracellular matrix ligands synergistically modulate integrin adhesion and signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 217(2):450–458, 2008. 10.1002/jcp.21512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takada, Y., X. Ye, and S. Simon. The integrins. Genome Biol. 8(5):215–215, 2007. 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.J. A. Alberts B Lewis J, et al., Integrins, In Molecular biology of the cell, 4th edition, New York: Garland Science, 2002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26867/

- 17.Danen EHJ, Integrins: An overview of structural and functional aspects, In Madame Curie Bioscience Database, Austin.

- 18.Hynes, R. O. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 110(6):673–687, 2002. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha, A., and E. Moore. Collagen-derived peptide, DGEA, inhibits pro-inflammatory macrophages in biofunctional hydrogels. J. Mater. Res. 37(1):77–87, 2022. 10.1557/s43578-021-00423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha, A., J. Larkin III., and E. Moore. SOCS1-KIR peptide in PEGDA hydrogels reduces pro-inflammatory macrophage activation. Macromol. Biosci. 23(9):2300237, 2023. 10.1002/mabi.202300237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, Y., and T. Segura. Biomaterials-mediated regulation of macrophage cell fate. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.609297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cha, B. H., et al. Integrin-mediated interactions control macrophage polarization in 3D hydrogels. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017. 10.1002/adhm.201700289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh, J. Y., T. D. Smith, V. S. Meli, T. N. Trans, E. L. Botvinick, and W. F. Liu. Differential regulation of macrophage inflammatory activation by fibrin and fibrinogen. Acta Biomater. 47:14–24, 2017. 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreejalekshmi, K. G., and P. D. Nair. Biomimeticity in tissue engineering scaffolds through synthetic peptide modifications—altering chemistry for enhanced biological response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 96A(2):477–491, 2011. 10.1002/jbm.a.32980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jha, A., and E. Moore. Laminin-derived peptide, IKVAV, modulates macrophage phenotype through integrin mediation. Matrix Biol. Plus. 22:100143, 2024. 10.1016/j.mbplus.2024.100143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durbeej, M. Laminins. Cell Tissue Res. 339(1):259–268, 2010. 10.1007/s00441-009-0838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timpl, R., H. Rohde, P. G. Robey, S. I. Rennard, J. M. Foidart, and G. R. Martin. Laminin–a glycoprotein from basement membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 254(19):9933–9937, 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malinda, K. M., and H. K. Kleinman. The laminins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 28(9):957–959, 1996. 10.1016/1357-2725(96)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kular, J. K., S. Basu, and R. I. Sharma. The extracellular matrix: structure, composition, age-related differences, tools for analysis and applications for tissue engineering. J. Tissue Eng. 5:2041731414557112, 2014. 10.1177/2041731414557112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.“Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes | Nature Reviews Immunology.” Accessed Feb. 05, 2024. [Online]. https://www.nature.com/articles/nri1375 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Iorio, V., L. D. Troughton, and K. J. Hamill. Laminins: roles and utility in wound repair. Adv. Wound Care. 4(4):250–263, 2015. 10.1089/wound.2014.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt, G. The role of laminin in cancer invasion and metastasis. Exp. Cell Biol. 57(3):165–176, 1989. 10.1159/000163521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akhavan, A., et al. Loss of cell surface laminin anchoring promotes tumor growth and is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Cancer Res. 72(10):2578–2588, 2012. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura, M., K. Yamaguchi, M. Mie, M. Nakamura, K. Akita, and E. Kobatake. Promotion of angiogenesis by an artificial extracellular matrix protein containing the laminin-1-derived IKVAV sequence. Bioconjug. Chem. 20(9):1759–1764, 2009. 10.1021/bc900126b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kikkawa, Y., K. Hozumi, F. Katagiri, M. Nomizu, H. K. Kleinman, and J. E. Koblinski. Laminin-111-derived peptides and cancer. Cell Adhes. Migr. 7(1):150–159, 2013. 10.4161/cam.22827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massia, S. P., S. S. Rao, and J. A. Hubbell. Covalently immobilized laminin peptide Tyr-Ile-Gly-Ser-Arg (YIGSR) supports cell spreading and co-localization of the 67-kilodalton laminin receptor with alpha-actinin and vinculin. J. Biol. Chem. 268(11):8053–8059, 1993. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53062-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graf, J., et al. Identification of an amino acid sequence in laminin mediating cell attachment, chemotaxis, and receptor binding. Cell. 48(6):989–996, 1987. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim, Y.-Y., et al. Laminin peptide YIGSR enhances epidermal development of skin equivalents. J. Tissue Viability. 27(2):117–121, 2018. 10.1016/j.jtv.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown, C. T., et al. Sex-dependent regeneration patterns in mouse submandibular glands. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 68(5):305, 2020. 10.1369/0022155420922948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan, K. M. F., and D. J. Falcone. Role of laminin in matrix induction of macrophage urokinase-type plasminogen activator and 92-kDa metalloproteinase expression. J. Biol. Chem. 272(13):8270–8275, 1997. 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huard, T. K., H. L. Malinoff, and M. S. Wicha. Macrophages express a plasma membrane receptor for basement membrane laminin. Am. J. Pathol. 123(2):365–370, 1986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.L. Li et al., Endothelial basement membrane laminins as an environmental cue in monocyte differentiation to macrophages, Front. Immunol., vol. 11, 2020, Accessed Feb. 07, 2024. [Online]. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.584229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Frith, J. E., R. J. Mills, J. E. Hudson, and J. J. Cooper-White. Tailored integrin-extracellular matrix interactions to direct human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 21(13):2442–2456, 2012. 10.1089/scd.2011.0615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, Y., K. J. Grande-Allen, and J. L. West. Adhesive peptide sequences regulate valve interstitial cell adhesion, phenotype and extracellular matrix deposition. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 9(4):479–479, 2016. 10.1007/S12195-016-0451-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore, E. M., G. Ying, J. L. West, E. M. Moore, G. Ying, and J. L. West. Macrophages influence vessel formation in 3D bioactive hydrogels. Adv. Biosyst. 1(3):1600021–1600021, 2017. 10.1002/ADBI.201600021. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz, R. R., and J. L. West. Tunable PEG hydrogels for discerning differential tumor cell response to biomechanical cues. Adv. Biol. 6(12):e2200084, 2022. 10.1002/adbi.202200084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burdick, J. A., and K. S. Anseth. Photoencapsulation of osteoblasts in injectable RGD-modified PEG hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 23(22):4315–4323, 2002. 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maeda, T., K. Titani, and K. Sekiguchi. Cell-adhesive activity and receptor-binding specificity of the laminin-derived YIGSR sequence grafted onto Staphylococcal protein A. J. Biochem. (Tokyo). 115(2):182–189, 1994. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quantification of fixed adherent cells using a strong enhancer of the fluorescence of DNA dyes | Scientific Reports. Accessed May 10, 2024. [Online]. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-45217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Nath, A., S. Chattopadhya, U. Chattopadhyay, and N. K. Sharma. Macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)1α and MIP1β differentially regulate release of inflammatory cytokines and generation of tumoricidal monocytes in malignancy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 55(12):1534–1541, 2006. 10.1007/s00262-006-0149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakae, Y., H. Takada, S. Ichinose, M. Nakajima, A. Sakai, and R. Ogawa. Treatment with YIGSR peptide ameliorates mouse tail lymphedema by 67 kDa laminin receptor (67LR)-dependent cell-cell adhesion. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 35:101514, 2023. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwamoto, Y., et al. YIGSR, a synthetic laminin pentapeptide, inhibits experimental metastasis formation. Science. 238(4830):1132–1134, 1987. 10.1126/science.2961059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lech, M., and H.-J. Anders. Macrophages and fibrosis: how resident and infiltrating mononuclear phagocytes orchestrate all phases of tissue injury and repair. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA–Mol. Basis Dis. 1832:989–997, 2013. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bahr, J. C., X.-Y. Li, T. Y. Feinberg, L. Jiang, and S. J. Weiss. Divergent regulation of basement membrane trafficking by human macrophages and cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2022. 10.1038/s41467-022-34087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danella Polli, C., et al. Monocyte migration driven by galectin-3 occurs through distinct mechanisms involving selective interactions with the extracellular matrix. ISRN Inflamm. 2013. 10.1155/2013/259256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Full article: Polymeric nanospheres modified with YIGSR peptide for tumor targeting. Accessed Feb. 07, 2024. [Online]. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/10717544.2010.490249

- 57.Sarfati, G., T. Dvir, M. Elkabets, R. N. Apte, and S. Cohen. Targeting of polymeric nanoparticles to lung metastases by surface-attachment of YIGSR peptide from laminin. Biomaterials. 32(1):152–161, 2011. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chausse, V., et al. Functionalization of 3D printed polymeric bioresorbable stents with a dual cell-adhesive peptidic platform combining RGDS and YIGSR sequences. Biomater. Sci. 11(13):4602–4615, 2023. 10.1039/D3BM00458A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoshida, N., et al. The laminin-derived peptide YIGSR (Tyr–Ile–Gly–Ser–Arg) inhibits human pre-B leukaemic cell growth and dissemination to organs in SCID mice. Br. J. Cancer. 80:12, 1999. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mestas, J., and C. C. W. Hughes. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J. Immunol. 172(5):2731–2738, 2004. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spiller, K. L., et al. Differential gene expression in human, murine, and cell line-derived macrophages upon polarization. Exp. Cell Res. 347(1):1–13, 2016. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shanmugham, L. N., et al. Rantes potentiates human macrophage aggregation and activation responses to calcium ionophore (A23187) and activates arachidonic acid pathways. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 20(1–2):15–23, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rollins, B. J., T. Yoshimura, E. J. Leonard, and J. S. Pober. Cytokine-activated human endothelial cells synthesize and secrete a monocyte chemoattractant, MCP-1/JE. Am. J. Pathol. 136(6):1229–1233, 1990. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]