ABSTRACT

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infection (BSI) is a serious public health concern. At times, MRSA is isolated from the blood along with other pathogens, the significance and consequences of which are not well described. This study aims to outline the clinical characteristics and outcomes of those with polymicrobial MRSA BSI compared with those with monomicrobial MRSA BSI. We conducted a retrospective case-control study of those with and without polymicrobial MRSA BSI from 2014 to 2022 at a single quaternary care center in New York City. Risk factors and outcomes for polymicrobial MRSA BSI were assessed using logistic regression analyses. Of 559 patients with MRSA BSI during the study period, 49 (9%) had polymicrobial MRSA BSI. Gram-positive Enterococcus (23%) was the most common co-pathogen. The presence of urinary (P = 0.02) and gastrointestinal (P < 0.01) devices was significantly associated with polymicrobial MRSA BSI. Polymicrobial MRSA BSI was associated with intensive care unit (ICU) admission after BSI (P = 0.01). Mortality did not differ. While polymicrobial MRSA BSI is relatively uncommon, it complicates an already complex clinical scenario of MRSA BSI.

IMPORTANCE

Staphylococcus aureus is a common human pathogen associated with severe disease and high mortality rates. Although clinically observed, little is known about the impact of polymicrobial staphylococcal bloodstream infection. This study evaluates polymicrobial methicillin-resistant S. aureus bloodstream infection (BSI), highlighting the increased risk of intensive care unit admission and impact on morbidity. Identifying risk factors for polymicrobial BSI, such as the presence of specific devices, can aid in early recognition and targeted interventions. Clarifying the risks and outcomes of polymicrobial infections can lead to strategies to minimize and manage these infections and explore the potential interactions between pathogens.

KEYWORDS: Staphylococcus aureus, bloodstream infections, bacteremia

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a common pathogen that frequently causes bloodstream infections (BSI) in community and hospital settings (1). The overuse and misuse of antibiotics have led to the global emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which is associated with poor outcomes, including a mortality rate of up to 30% (2). Although most BSI are caused by a single pathogen, polymicrobial BSI occurs when more than one species of pathogen is found in the blood culture. The general incidence of polymicrobial BSI ranges from 6% to 11% (3, 4). Polymicrobial BSI has been associated with worse outcomes when compared to monomicrobial BSI (5). These outcomes have been attributed to an increased likelihood of septic shock, prolonged stays in the intensive care unit and hospital, as well as higher mortality (5). In addition, there is growing awareness of the impact of microbial interactions, and defining the potential of these pathogen interactions in disease severity and outcome may lead to innovative preventative and therapeutic measures for combating infection (6).

Only a small number of studies have focused on clinical characteristics and outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus in the setting of polymicrobial BSI (5, 7). We hypothesized that several risk factors may be associated with polymicrobial MRSA BSI, particularly the source of infection, and presence of invasive devices and that polymicrobial infections may result in worse outcomes. This study aims to outline the clinical characteristics and outcomes of those patients with MRSA polymicrobial BSI and compare them with those with monomicrobial MRSA BSI.

RESULTS

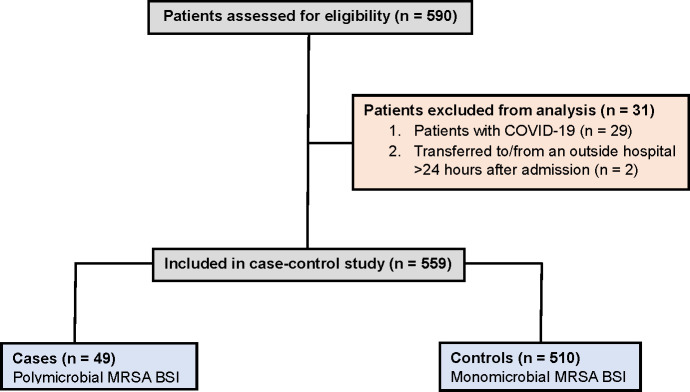

During the 8-year study, 559 adult patients had at least one positive blood culture for MRSA, of which 49 (9%) had polymicrobial MRSA BSI (cases) (Fig. 1). In order to mitigate potential confounding effects attributed to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), 29 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), who required treatment directed at SARS-CoV-2 during the same admission for MRSA BSI, had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test within 2 weeks prior to or after the BSI diagnosis, or were symptomatic due to SARS-CoV-2 per clinical documentation were excluded. Demographics and clinical characteristics of cases of polymicrobial and controls with monomicrobial MRSA BSI are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were males (63%), and aged 55 and above. Skin infections were the main source of MRSA BSI, representing 27% of polymicrobial cases and 30% of monomicrobial cases. Infections related to vascular access constituted 29% of polymicrobial and 25% of monomicrobial cases. In the study, 21 patients (43%) with polymicrobial MRSA BSI had a central line, compared to 185 patients (36%) in the control group. There was no significant association found between the presence of a central line and polymicrobial MRSA BSI. The average Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (8) among patients was 5.7.

Fig 1.

Flowchat outlining the selection of cases and controls with predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and univariate analysis of polymicrobial MRSA BSIl

| Characteristic, n (%) | Cases (n = 49) |

Controls (n = 510) |

OR (95% interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 37 (76) | 313 (61) | 1.94 (0.99–3.81) | 0.05 |

| Female | 12 (24) | 197 (39) | Reference | |

| Age at time of infection | ||||

| 18–54 years | 13 (27) | 162 (32) | Reference | |

| 55–69 years | 18 (37) | 161 (32) | 1.39 (0.66–2.94) | 0.44 |

| ≥70 years | 18 (37) | 187 (37) | 1.99 (0.57–2.52) | 0.96 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 19 (39) | 176 (35) | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14 (29) | 136 (27) | 0.95 (0.46–1.97) | 0.90 |

| Hispanic | 9 (18) | 117 (24) | 0.71 (0.33–1.51) | 0.97 |

| Other | 15 (31) | 154 (30) | 1.02 (0.54–1.93) | 0.95 |

| Missing/unknown | 1 (2) | 27 (5) | ||

| History of IV drug use | ||||

| Yes | 6 (12) | 61 (12) | 1.03 (0.42–2.51) | 0.95 |

| No | 43 (88) | 449 (88) | Reference | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | ||||

| <18.5 | 5 (10) | 57 (11) | 0.74 (0.28–1.95) | 0.80 |

| 18.5–29.9 | 37 (76) | 310 (61) | Reference | |

| ≥30.0 | 7 (14) | 141 (28) | 0.42 (0.18–0.96) | 0.12 |

| HIV diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 4 (8) | 42 (8) | 0.99 (0.34–2.89) | 0.99 |

| No | 45 (92) | 468 (92) | Reference | |

| Admission source | ||||

| Homea | 27 (55) | 308 (61) | Reference | |

| NH/rehab/LTACH | 10 (20) | 65 (13) | 1.76 (0.81–3.80) | 0.15 |

| Outside hospital | 12 (24) | 136 (27) | 1.01 (0.50–2.05) | 0.45 |

| Prior hospital admission (90 days) | ||||

| Yes | 31 (63) | 327 (64) | 1.04 (0.57–1.91) | 0.91 |

| No | 18 (37) | 183 (36) | Reference | |

| Presence of invasive devices | ||||

| Yes | 42 (86) | 360 (71) | 2.5 (1.10–5.69) | 0.03 |

| No | 7 (14) | 150 (29) | Reference | |

| Invasive device | ||||

| Cardiacb | 8 (16) | 53 (10) | 1.68 (0.75–3.78) | 0.21 |

| Vascularc | 22 (45) | 227 (45) | 1.02 (0.56–1.83) | 0.96 |

| Orthopedic | 5 (10) | 58 (11) | 0.89 (0.34–2.32) | 0.81 |

| Urinaryd | 21 (43) | 135 (26) | 2.08 (1.14–3.79) | 0.02 |

| Gastrointestinale | 15 (31) | 73 (14) | 2.64 (1.37–5.09) | <0.01 |

| Otherf | 6 (12) | 31 (6) | 2.16 (0.85–5.46) | 0.10 |

| Clonal complex (CC) | ||||

| CC5 | 23 (47) | 209 (41) | Reference | |

| CC8 | 14 (29) | 206 (40) | 0.62 (0.31–1.23) | 0.17 |

| Other | 11 (22) | 55 (11) | ||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 40 (8) | ||

| Length of hospital stay prior to BSI | ||||

| BSI ≤ 3 days after admission | 28 (57) | 353 (69) | Reference | |

| BSI > 3 days after admission | 21 (43) | 157 (31) | 1.69 (0.93–3.06) | 0.09 |

| Wound presentg | ||||

| Yes | 31 (63) | 299 (59) | 1.22 (0.66–2.23) | 0.53 |

| No | 18 (37) | 211 (41) | Reference | |

| Hemodialysis | ||||

| Yes | 4 (8) | 96 (19) | 2.61 (0.92–7.46) | 0.07 |

| No | 45 (92) | 414 (81) | Reference | |

| Source of infection | ||||

| Skinh | 13 (27) | 153 (30) | 0.84 (0.44–1.63) | 0.61 |

| Pneumonia | 6 (12) | 60 (12) | 1.05 (0.43–2.56) | 0.92 |

| Bonei | 4 (8) | 56 (11) | 0.72 (0.25–2.08) | 0.55 |

| Vascularj | 14 (29) | 130 (25) | 1.17 (0.61–2.24) | 0.64 |

| Otherk | 15 (31) | 142 (28) | 1.14 (0.60–2.16) | 0.68 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| 0–3 | 15 (31) | 141 (28) | Reference | |

| 4–5 | 6 (12) | 110 (22) | 0.51 (0.19–1.37) | 0.13 |

| 6–8 | 17 (35) | 158 (31) | 1.01 (0.49–2.10) | 0.48 |

| >8 | 11 (22) | 101 (20) | 1.02 (0.45–2.32) | 0.51 |

“Home”: included nonmedical residences such as home, group homes, assisted living facilities, and homeless shelters.

“Cardiac (invasive device)”: included pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD), left ventricular-assist devices (LVAD).

“Vascular (invasive device)”: included arteriovenous (AV) grafts and other vascular invasive devices.

“Urinary (invasive device)”: included urinary collection devices (ileal conduits, nephrostomy tubes, suprapubic catheters), and foley catheters.

“Gastrointestinal (invasive device)”: included percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes and ostomies.

“Other (invasive device)”: included chest tubes, wound devices, drains, nasogastric tubes, shunts, tracheostomy, endovascular valves, and stents.

“Wound present”: the presence of a chronic skin wound overlying the sacrum, limb, abdomen, or other body parts.

“Skin (source of infection)”: MRSA infection from peripheral IV, surgical site infection, sacral wound, and midline catheter.

“Bone (source of infection)”: MRSA infection from diabetic foot ulcer and osteomyelitis.

“Vascular (source of infection)”: vascular access devices include a non-tunneled central venous catheter, tunneled catheter (hickman or permacath), implanted port, peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line), and arteriovenous graft (AVG) and fistula (AVF).

“Other (source of infection)”: MRSA infection from a spinal infection, septic arthritis or cardiac device infection, intra-abdominal infection, GU, or an unknown/not reported source.

Abbreviations: BSI, bloodstream infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; HACO, healthcare associated community-onset; ICU, intensive care unit; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

In the univariate analysis (Table 1), the presence of invasive devices demonstrated a significant association with polymicrobial MRSA BSI (odds ratio [OR], 2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–5.69; P = 0.03). Specifically, urinary devices (OR, 2.08; 95% CI, 1.14–3.79; P = 0.02) and gastrointestinal devices (OR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.37–5.09; P < 0.01) were associated with polymicrobial MRSA BSI. Cases were found to have a higher prevalence of MRSA BSI with the clonal complex (CC) 5 compared to the CC8 (47% vs 29%) though 41 patients (7%) had incomplete gene typing data and were, therefore, excluded from the typing analysis. Baseline hemodialysis (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 0.92–7.46; P = 0.07) exhibited a P-value approaching significance (Table 1).

Polymicrobial MRSA BSI was associated with poorer outcomes, with increased intensive care unit (ICU) admissions after polymicrobial BSI (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.21–4.24; P = 0.01) (Table 2). Admission to the ICU before bacteremia was not associated with the subsequent development of polymicrobial MRSA BSI. No confounding effect was observed between ICU admission after BSI and the presence of invasive devices. There were no significant differences in 30-day (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.40–1.69; P = 0.98), 60-day (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.51–2,11; P = 0.91), and 90-day mortality (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.52–2.18; P = 0.86).

TABLE 2.

Univariate analysis of patient outcomes with polymicrobial MRSA BSIc

| Characteristic, n (%) | Cases (n = 49) |

Controls (n = 510) |

OR (95% interval) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-day Mortality | ||||

| Yes | 11 (25) | 113 (24) | 1.07 (0.52–2.18) | 0.86 |

| No | 33 (75) | 361 (76) | Reference | |

| Mortality related to MRSA | ||||

| Yes | 13 (72) | 103 (63) | 0.66 (0.22–1.94) | 0.45 |

| No | 5 (28) | 60 (37) | Reference | |

| Recurrent bacteremiaa | ||||

| Yes | 2 (4) | 63 (12) | 0.30 (0.07–1.26) | 0.98 |

| No | 47 (96) | 443 (87) | Reference | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | ||

| Metastatic infectionb | ||||

| Yes | 9 (18) | 99 (19) | 0.92 (0.43–1.97) | 0.98 |

| No | 40 (82) | 406 (80) | Reference | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | ||

| ICU admission after BSI | ||||

| Yes | 17 (35) | 97 (19) | 2.26 (1.21–4.24) | 0.01 |

| No | 32 (65) | 413 (81) | Reference | |

| Intubated after BSI | ||||

| Yes | 6 (12) | 71 (14) | 0.86 (0.35–2.10) | 0.75 |

| No | 43 (88) | 439 (86) | Reference |

“Recurrent bacteremia”: MRSA BSI with a positive blood culture over 30 days after the last positive blood culture.

“Metastatic infection”: distal or secondary infection, anatomically unrelated to the primary site of infection, presenting during index admission of MRSA BSI. Includes infective endocarditis, septic pulmonary emboli, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, iliopsoas abscess.

Abbreviations: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; BSI, bloodstream infection; ICU, intensive care unit.

We evaluated the types of organisms in polymicrobial MRSA BSI, with Table 3 presenting the frequency of microorganisms identified. Enterococcus species was the most frequently detected pathogen, accounting for 23% of cases. Upon further breakdown, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus avium were responsible for 18.3%, 3.3%, and 1.6% of the cases, respectively. Klebsiella, Proteus, and Streptococcus species were also present in 11.7% of cases. Most co-pathogens were gram-positive bacteria with a prevalence of 53%, followed by gram-negative at 43%, and yeast at 3% (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Frequency of organisms classified by gram stain in polymicrobial MRSA BSI

| Organism | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gram positive | 32 | 53 |

| Bacillus spp. | 2 | 3.3 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 14 | 23.3 |

| MSSA | 3 | 5.0 |

| Rhodococcus spp. | 1 | 1.7 |

| Staph coag neg spp. | 5 | 8.3 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 7 | 11.7 |

| Gram negative | 26 | 43 |

| Acinetobacter spp. | 2 | 3.3 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 1 | 1.7 |

| Escherichia spp. | 5 | 8.3 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 7 | 11.7 |

| Proteus spp. | 7 | 11.7 |

| Providencia spp. | 1 | 1.7 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 3 | 5.0 |

| Yeast | 2 | 3 |

| Candida spp. | 2 | 3.3 |

DISCUSSION

Bloodstream infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus is a serious health concern associated with high morbidity and mortality. Despite its occurrence in the clinical setting, little is known about the implications of polymicrobial MRSA BSI syndrome. In this retrospective case-control study, we found polymicrobial BSI to occur in 9% of all MRSA BSI cases and determined the clinical characteristics and outcomes of those with polymicrobial MRSA BSI. The presence of urinary and gastrointestinal invasive devices was significantly associated with the development of polymicrobial MRSA BSI. A significant association was also found between polymicrobial MRSA BSI and ICU admission after BSI, and the most frequent co-pathogen was gram-positive Enterococcus.

Invasive devices in the genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) systems were associated with polymicrobial MRSA BSI. GU devices, such as urinary catheters, can promote the formation of biofilms, enabling the adherence and colonization of microorganisms (9). Similarly, GI devices such as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes can act as pathways for microorganisms from the external environment, leading to biofilm formation and subsequent complications (6). Hence, the presence of biofilms on GU and GI devices may contribute to the development of polymicrobial MRSA BSI. Moreover, S. aureus is well equipped with a host of virulence factors that promote invasion and adherence, such as biofilm formation (1). It is important to note that this study did not establish significant associations between the source of infection and polymicrobial MRSA BSI.

Patients with invasive devices likely have underlying medical conditions that weaken their immune system, making them more susceptible to infection. Healthcare-associated risk factors were prevalent among patients with polymicrobial MRSA BSI. Indeed, this was found in a previous study of polymicrobial bacteremia which demonstrated a correlation between polymicrobial episodes and hospital-acquired infections (10). As devices of the GU and GI tracts are frequently indicative of underlying comorbidities due to their necessity in these comorbidities, this potentially contributes to the observed findings. Our study revealed an average CCI of 5.7 among all patients, exceeding the commonly reported range of 1.5–3 in other studies (5, 8).

In addition to the link between polymicrobial MRSA BSI and healthcare-associated risk factors, the prevalence of specific MRSA clones offers further insights. Our study revealed a higher prevalence of CC5 compared to CC8 genotypes in cases of polymicrobial MRSA BSI. CC5 is historically associated with older individuals with hospital or long-term care facility exposure, whereas CC8 (specifically the USA300 pulsotype) is associated with community settings although studies have found these historical connections are fading (2, 11). Our findings suggest that hospital-adapted clones may lead to the development of polymicrobial MRSA BSI within the hospital setting. Despite the analysis not being able to establish a significant association between polymicrobial MRSA BSI and hospital-onset (HO) MRSA infections, it is crucial to acknowledge that cases of BSI occurring within the first 3 days after admission (community-onset or CO) included mainly those with healthcare-associated community-onset MRSA infection, defined as a positive blood culture within the initial 72 h of admission, but also containing risk factors associated with hospital settings (frequent healthcare interactions, hemodialysis status, hospitalization within the prior 3 months, or residence in long-term acute care facilities). Only three cases of polymicrobial MRSA BSI were identified as truly CO. Characterization of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of clones associated with infections especially in those with invasive devices signal potential areas of intervention in infection control.

We describe an increase in ICU admissions after BSI in polymicrobial MRSA BSI as compared to controls. Infection with multiple pathogens may lead to severe symptoms, complications, and additional therapeutic challenges. The presence of polymicrobial MRSA BSI may also be a marker of underlying comorbidity inherently leading to worse outcomes and the need for ICU care. It is notable that mortality did not differ between the groups. Polymicrobial bacteremia likely increases antibiotic class exposures and may have downstream impacts on the development of microbial drug resistance.

Enterococcus spp. was the most common co-pathogen in polymicrobial MRSA BSI, while a previously published study found Acinetobacter baummanii predominant co-pathogen, followed by Enterococcus spp. (5). Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp. are gram-positive pathogens that cause bacteremia and infective endocarditis. While studies have focused on the mechanisms by which S. aureus acquires the vancomycin resistance gene (vanA, for example) from vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, no other known synergistic or antagonistic interactions exist between Enterococcus spp. and S. aureus (6, 12, 13). Nonetheless, coinfection with these pathogens has led to a notable surge in multidrug-resistant Staphylococci (14). Further clinical and molecular investigations focused on specific pathogen interactions are warranted.

This study had certain limitations. It was conducted retrospectively and is at risk of chart abstraction errors. Patient characteristics and demographics were obtained through the review of patient records, rather than through a clinical examination at the time of infection. Due to the inability to accurately track outcomes after hospital discharge, deaths that occurred outside of the hospital may not have been considered. While we utilized ID consultant notes to exclude contaminants, we acknowledge that differences in ID provider practices could lead to variability in the classification of organisms as contaminants or pathogens. Furthermore, 7% of infections lacked gene typing data, which may introduce bias and reduce the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the low number of polymicrobial MRSA BSI cases represents a limitation of the study. Further research is required to assess the impact of polymicrobial MRSA BSI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and definitions

This was a retrospective case-control study of patients with MRSA BSI admitted to Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) in New York City between September 2014 and July 2022. Hospitalized adults aged >18 years were included if they had at least one positive blood culture for MRSA. Cases were defined as those with polymicrobial MRSA BSI, and controls were defined as those with monomicrobial MRSA BSI. Polymicrobial MRSA BSI was defined as the isolation of one or more microorganisms within 24 h before or after a positive MRSA blood culture, encompassing a 48-h timeframe. Data from the first positive blood culture event from the admission was included, aside from two individuals who developed polymicrobial BSI only during the second MRSA BSI episode. Patients were excluded if they were transferred to MSH from an outside hospital or from MSH to an outside hospital for more than 24 h after admission. Given the awareness of the contribution of SARS-CoV-2 disease status, especially since the study spanned COVID-19 pandemic, we excluded those with SARS-CoV-2 who required treatment directed at SARS-CoV-2 during the same admission for MRSA BSI, had a positive SARS-CoV-2 test within 2 weeks prior to or after the BSI diagnosis, or were symptomatic due to SARS-CoV-2 per clinical documentation. The protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board (HS #13-00981 and HS# 17-00825). Authorization for the use and disclosure of protected health information (PHI) was obtained through a waiver, and informed consent was waived. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, including later amendments.

Specimen data were collected from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory (CML) of MSH by the Mount Sinai Pathogen Surveillance Program. The CML identified organisms using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Bruker Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics), with use of Vitek 2 (bioMérieux) and/or Microscan (Beckman Coulter) for susceptibilities according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (15) standards.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were retrospectively extracted from the electronic medical record system, and entered into a REDCap (16) database, as previously described (2), with review by at least two infectious diseases (ID) trained investigators. Particular emphasis was placed on reviewing ID notes to identify potential contaminants, defined as organisms isolated from blood culture that are not considered clinically significant (17). As it is standard practice at our institution to have ID consultations on all patients diagnosed with S. aureus BSI, ID clinical notes were reviewed in depth to assist in these determinations. One of the main deciding features was documentation of the ID consultant’s decision-making, especially if the ID consultants decided to provide treatment for the co-pathogens identified. Those deemed to have contaminants were added to the control group. Positive cultures on or after the fourth day following hospital admission were defined as HO MRSA, while BSI occurring during the first 72 h of hospital admission was defined as CO MRSA according to National Healthcare Safety Network definitions (18).

Statistical analysis

For our analysis, we selected established clinical factors related to S. aureus infection, such as demographics, admission sources, presence of invasive devices, and sources of infection. Additionally, we examined patient outcomes and mortality, particularly those related to MRSA BSI. Differences in patient characteristics were assessed by the chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and by the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normal continuous variables. Given the exploratory nature of the study, the association of each risk factor on the development of polymicrobial MRSA BSI and each outcome was assessed using univariate logistic regression. Statistical significance was measured by a P-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Studio (19).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) grant UL1TR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

This research received support from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai under the CTSA/NCATS KL2 Program (grant no. KL2TR001435 to D.R.A.) and from the New York State Department of Health Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (awarded to Judith A. Aberg, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; D.R.A.; and grant no. R01 AI119145 to H.v.B.). Dr. Harm van Bakel received additional institutional funds from ISMMS and the Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, while Dr. Deena Altman received institutional funding from participation in ContraFect corporation clinical trials. The other authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose. Presented in part: IDWeek, Boston, October 2023 (abstract # 191).

Contributor Information

Deena R. Altman, Email: deena.altman@mssm.edu.

Monika Kumaraswamy, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med 339:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dupper AC, Sullivan MJ, Chacko KI, Mishkin A, Ciferri B, Kumaresh A, Berbel Caban A, Oussenko I, Beckford C, Zeitouni NE, Sebra R, Hamula C, Smith M, Kasarskis A, Patel G, McBride RB, van Bakel H, Altman DR. 2019. Blurred molecular epidemiological lines between the two dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones. Open Forum Infect Dis 6:fz302. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pavlaki M, Poulakou G, Drimousis P, Adamis G, Apostolidou E, Gatselis NK, Kritselis I, Mega A, Mylona V, Papatsoris A, Pappas A, Prekates A, Raftogiannis M, Rigaki K, Sereti K, Sinapidis D, Tsangaris I, Tzanetakou V, Veldekis D, Mandragos K, Giamarellou H, Dimopoulos G. 2013. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections: epidemiology and impact on mortality. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 1:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kiani D, Quinn EL, Burch KH, Madhavan T, Saravolatz LD, Neblett TR. 1979. The increasing importance of polymicrobial bacteremia. JAMA 242:1044–1047. doi: 10.1001/jama.1979.03300100022015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng C, Zhang S, Chen Q, Zhong L, Huang T, Zhang X, Zhang K, Zhou H, Cai J, Du L, Wang C, Cui W, Zhang G. 2020. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of polymicrobial Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9:76. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00741-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, O’May GA, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. 2012. Polymicrobial interactions: impact on pathogenesis and human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:193–213. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00013-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hindy J-R, Quintero-Martinez JA, Lahr BD, DeSimone DC, Baddour LM. 2022. A population-based evaluation of polymicrobial Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Pathogens 11:1499. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11121499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McGregor JC, Kim PW, Perencevich EN, Bradham DD, Furuno JP, Kaye KS, Fink JC, Langenberg P, Roghmann M-C, Harris AD. 2005. Utility of the chronic disease score and charlson comorbidity index as comorbidity measures for use in epidemiologic studies of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Am J Epidemiol 161:483–493. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nicolle LE. 2014. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 3:23. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weinstein MP, Reller LB, Murphy JR. 1986. Clinical importance of polymicrobial bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 5:185–196. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(86)90001-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seybold U, Kourbatova EV, Johnson JG, Halvosa SJ, Wang YF, King MD, Ray SM, Blumberg HM. 2006. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin Infect Dis 42:647–656. doi: 10.1086/499815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nair N, Biswas R, Götz F, Biswas L. 2014. Impact of Staphylococcus aureus on pathogenesis in polymicrobial infections. Infect Immun 82:2162–2169. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00059-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ray AJ, Pultz NJ, Bhalla A, Aron DC, Donskey CJ. 2003. Coexistence of vancomycin-resistant enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus in the intestinal tracts of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 37:875–881. doi: 10.1086/377451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu W, Murray PR, Huskins WC, Jernigan JA, McDonald LC, Clark NC, Anderson KF, McDougal LK, Hageman JC, Olsen-Rasmussen M, Frace M, Alangaden GJ, Chenoweth C, Zervos MJ, Robinson-Dunn B, Schreckenberger PC, Reller LB, Rudrik JT, Patel JB. 2010. Dissemination of an Enterococcus Inc18-Like vanA plasmid associated with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4314–4320. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00185-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. CLSI Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed. guideline M100. 2021. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. 2007. CLSI Principles and Procedures for Blood Cultures: Approved Guideline M47-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [Google Scholar]

- 18. 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multidrug-Resistant Organism & Clostridioides difficile Infection (MDRO/CDI) Module. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 19. 2013. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide: Statistical Procedures: SAS Institute [Google Scholar]