ABSTRACT

Background

Biofilm formation on implant-abutment surfaces can cause inflammatory reactions. Ethical concerns often limit intraoral testing, necessitating preliminary in vitro or animal studies. Here, we propose an in vitro model using human saliva and hypothesize that this model has the potential to closely mimic the dynamics of biofilm formation on implant-abutment material surfaces in vivo.

Methods

A saliva stock was mixed with modified Brain-Heart-Infusion medium to form biofilms on Titanium-Aluminum-Vanadium (Ti6Al4V) and Yttria-partially Stabilized Zirconia (Y-TZP) discs in 24-well plates. Biofilm analyses included crystal violet staining, intact cell quantification with BactoBox, 16S rRNA gene analysis, and short-chain fatty acids measurement. As a control, discs were worn in maxillary splints by four subjects for four days to induce in vivo biofilm formation.

Results

After four days, biofilms fully covered Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP discs both in vivo and in vitro, with similar cell viability. There was a 60.31% overlap of genera between in vitro and in vivo biofilms in the early stages, and 41% in the late stages. Ten key oral bacteria, including Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Veillonella, and Porphyromonas, were still detectable in vitro, representing the common stages of oral biofilm formation.

Conclusion

This in vitro model effectively simulates oral conditions and provides valuable insights into biofilm dynamics.

KEYWORDS: Ti6Al4V, Y-TZP, cell viability, 16S rRNA gene analysis, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Veillonella, Porphyromonas, biofilm dynamics

Background

Biofilm research is essential for understanding how intraoral materials interact with the complex microbial communities in the oral cavity. This knowledge is vital in dentistry [1], where biofilms can, for example, degrade composite fillings [1,2] and cause peri-implant diseases such as peri-implantitis in oral implantology, affecting 22% of patients and leading to implant failure [3]. Given the 12–18 million dental implants placed annually worldwide, peri-implantitis poses significant economic and clinical challenges [4]. The human oral microbiome has become a central focus of research due to its significant implications for overall health [5]. There is growing interest in how short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) influence oral microbiome composition, oral health, and chronic inflammation [5,6]. SCFA production serves as a key metabolic indicator of biofilm dynamics, offering insights into microbial activity and biofilm behavior [5]. Understanding biofilm dynamics is therefore essential for developing dental and implant-abutment materials that minimize biofilm formation, prevent inflammation, and ensure the longevity and safety of oral restorations [2].

Studies on material properties and surface characteristics, including bacterial adhesion, have advanced our understanding of oral biofilm formation [7]. However, many studies use single bacterial species or defined cultures under in vitro conditions, which may not reflect real-world conditions [1,7]. Testing materials with real saliva is recommended [8], as it supports the formation of the acquired enamel pellicle (AEP), a protective layer that also facilitates biofilm development [1,9,10]. In situ studies are considered most useful due to the significant influence of saliva and the AEP on material bioactivity [1,2].

However, in vitro approaches are still needed because animal testing is increasingly avoided and ethical approval for in vivo studies involving novel materials and biofunctionalization (coatings) [11–13], becomes more challenging, due to unknown medium- and long-term side effects [14]. Using Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP platelets, which are known for their biocompatibility, corrosion resistance, and hardness [15,16] and therefore commonly applied in oral implantology especially for superstructures, we propose an in vitro model utilizing standardized human saliva as an inoculum for biofilm formation. We hypothesize that this model can closely reproduce the dynamics of biofilm formation on implant-abutment material surfaces in vivo, and thus provide valuable insights for the development and evaluation of abutment materials and surfaces.

Methods

Sample preparation

Cylindrical Ti6Al4V bars were obtained from EWG E. Wagener (Germany). Ti6Al4V discs (diameter 9 mm, thickness 1.5 mm) were prepared by turning and subjected to a grinding process using silicon carbide grinding paper (No. 80, 800, 1200, 4000, ATM, Germany), sequentially.

Cylindrical Y-TZP (TZ-3YSB-E powder, Tosoh, Japan) discs were manufactured by uniaxial dry pressing using a stainless-steel cylindrical mold with the same dimensions as Ti6Al4V. Subsequently, Y-TZP discs were sintered at 1500°C for 2 h (Therm-Aix, Germany). Afterwards, the discs were ground (No. 40 and 74) and polished using diamond pastes (ATM, Germany). On both specimens a roughness value of Ra ˂ 0.2 µm was adjusted. The surface topography was assessed using a Keyence VK-X100 confocal laser scanning microscope (Keyence Deutschland, Neu-Isenburg, Germany). To remove potential organic residues, ceramic discs were heated up to 450°C for 15 min. Then, the discs were disinfected by sonication in 70% ethanol (Schmittmann GmbH, Germany) and Milli-Q water (Sartorius, Germany).

In vivo experimental setup

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, RWTH Aachen University (EK 165/10). Four healthy, non-smoking donors (two men and two women, average age 42) who had not taken antibiotics in the last three months participated in the study. One week before saliva collection or wearing the splint, each donor underwent a professional tooth cleaning by a specialized dental assistant using an ultrasonic scaler (KaVo PiezoLED, KaVo Dental GmbH, Biberach, Germany). Maxillary splints with embedded specimens were worn by the participants for four days, with a 1 mm distance between the specimens and the palatal surface (Figure 1a).

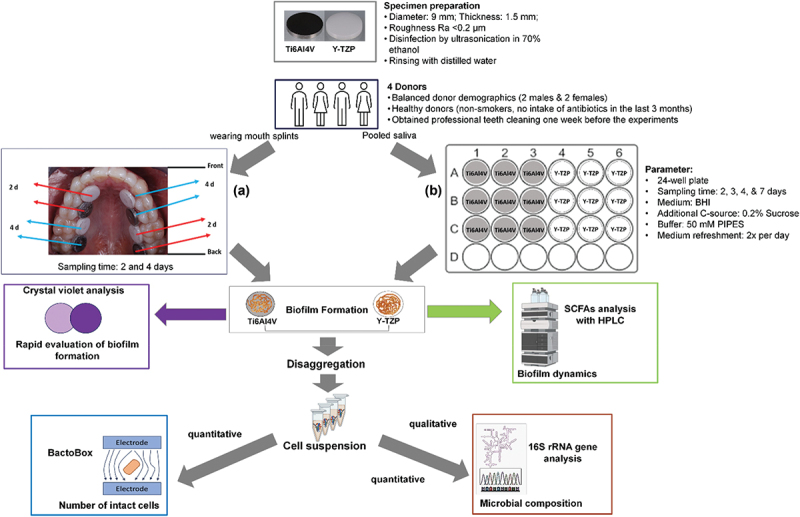

Figure 1.

Experimental scheme of biofilm formation under (a) in vivo condition where four donors wearing mouth splints with embedded specimens (four Ti6Al4V and four Y-TZP discs) (b) and in vitro condition where pooled saliva stock from the same donors used as an inoculum in modified BHI medium to form biofilm on Ti6Al4V and Y-tzp discs in 24-well plates. Biofilm formation was rapidly evaluated using crystal violet analysis. Biofilm-derived cell suspension was analyzed using BactoBox to determine the number of intact cells. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was then extracted to determine microbial composition via 16S rRNA gene analysis. The illustrative figures were partially created using BioRender.

The splints were removed six times a day for meals and oral hygiene, during which participants used an identical toothbrush (Aldi Eurodont Soft, M+C Schiffer GmbH, Germany) and toothpaste containing 1450 ppm sodium fluoride (Aldi Eurodont Active Fresh, Eurodont, MAXIM Markenprodukte GmbH & Co.KG, Germany). During these times, the splints were stored in isotonic saline solution 0.9% (B Braun Melsungen AG, Germany). Partial specimen removal for examination occurred after two and four days.

In vitro experimental setup

Unstimulated saliva was collected simultaneously from the four donors who also participated in the in vivo test. The donors were asked to refrain from brushing their teeth for 24 h and to abstain from consuming food or drink for at least 4 h before providing the saliva in the morning. The saliva samples were pooled and then mixed with anoxic 60% glycerol containing 37 g/L BHI at a 1:1 ratio to achieve a final concentration of glycerol of 30% and stored at −80°C in 2-mL aliquots before use. The standard version of BHI (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was anoxically prepared with 0.2% sucrose, 1 µg/mL resazurin, 0.005 g/L hemin, 0.01 g/L menadione, 0.5 g/L L-cysteine hydrochloride, and 50 mM 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES) buffer.

Sucrose served as an additional substrate to efficiently promote biofilm formation [17,18]. Resazurin was added as a redox indicator to ensure anoxic conditions in the medium [19,20]. Hemin and menadione were included as essential compounds for the growth of fastidious oral bacteria [8,21]. L-cysteine hydrochloride was used to reduce the redox potential of growth medium [20,22]. PIPES buffer was used to maintain a stable pH, essential for studying biofilms and the oral microbiome [17].

The modified medium was adjusted to pH 7.0 and used as a substrate for microcosm biofilm. Saliva stock was diluted in modified BHI medium with ratio of 1:50, added to a 24-well plate containing specimens, and incubated under anaerobic condition at 37°C. The cultures were kept in Oxoid AnaeroGen W-zip bags with Oxoid AnaeroGen to rapidly adsorb oxygen (Oxoid, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Germany). Biofilm formation was observed after 2, 3, 4, and 7 days of incubation (Figure 1b).

Crystal violet analysis

The biofilm-covered discs after 2 and 4 days for in vivo and after 2, 3, 4, and 7 days for in vitro tests were transferred to the new 24-well plate. The developed biofilm layer was fixed with 800 µL of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min, washed with 800 µL distilled water, and stained with 800 µL of 0.1% CV (100 mg crystal violet powder in 10 mL absolute ethanol and 90 mL distilled water) for 20 min. The dye was removed and washed with 800 µL distilled water. The discs were air-dried overnight and applied for rapid determination of biofilm formation.

Biofilm removal and disaggregation

Biofilm on three specimens of each not applied for crystal violet analysis was collected and disaggregated (mechanical removal in anoxic PBS peptone, pipetting, vortexing for 30 s, and ultrasonication for 1 min × 2 in cold water) to obtain single cells for intact cell quantification and DNA extraction.

Intact cell quantification with impedance flow cytometry

Intact cell quantification was performed using impedance flow cytometry (IFC) with the BactoBox (SBT Instruments, Denmark). Prior to analysis, the instrument was calibrated using calibration beads provided by the manufacturer and the conductivity was set between 1,600 and 2,100 µS/cm in the final samples. Bacterial cell samples were diluted appropriately to achieve a concentration ranging from 10,000 to 5,000,000 intact cells/mL.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction was carried out using the Monarch Genomic DNA Purification Kit (NEB, USA). Saliva or single cell suspensions obtained from biofilm samples were centrifuged at 16,200 × g for 2 min and resuspended in cold PBS. Subsequent steps involved cell lysis using proteinase K and RNase A, followed by the addition of cell lysis buffer and incubation at 56°C for 30 min in a thermal mixer with agitation at 1400 rpm. The resulting gDNA was bound to the column, washed, and finally eluted in preheated elution buffer. Concentration and purity of the extracted gDNA were checked using a nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop One, Thermo Scientific, Germany).

16S rRNA sequencing pipeline

The quality of the isolated DNA samples was checked by the corresponding TapeStation (Agilent) assay for genomic DNA, and all samples were quantified by the Quantus (Promega, Germany) fluorometer. The starting concentrations of all samples were adjusted prior to library construction. Sequencing libraries for the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were prepared with the Quick 16S NGS Library Prep Kit (Zymo Research Europe GmbH, Germany). Sequencing libraries were pooled equimolarly and sequenced with MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycles) (Illumina, USA).

After sequencing, FASTQ files were first generated using bcl2fastq (Illumina, USA). To facilitate reproducible analysis, the 16S rRNA sequencing data was analyzed using a standardized and public available workflow: nf-core/ampliseq pipeline version 2.6.1 [23]. The pipeline was executed with Nextflow v23.04.1 [24] using Docker 20.10.12 [25] with the minimal command. In brief, the quality of sequencing reads was controlled with FastQC and then trimmed with Cutadapt. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were inferred with DADA2 with a low abundance filter of 10 copies. Taxonomic classifications were achieved with DADA2 and QIIME2 with SILVA 138 as reference taxonomy [26]. Downstream analysis and visualizations were achieved with customized scripts and Bioconductor packages under R (version 4.2.2) [27]. The raw reads were deposited in NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1159109.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) production assay under in vitro conditions

The SCFAs production by biofilm during incubation was determined by collecting biofilm spent medium from the last medium refreshment before biofilm harvesting. The analysis was conducted with an Ultimate 3000 HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States) with 5 mM sulfuric acid (H2SO4) as a mobile phase and a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.

Samples were centrifuged and filtered before injection into the HPLC system. A Metab-AAC column (Ion exchange, 300 × 7.8 mm, 10 µm particle size; ISERA GmbH, Düren, Germany) was used for the separation. The column oven was heated to 60°C, and detection was performed with a refractive index detector for acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, and formic acid and UV detector at 210 nm for lactic acid.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicates, and results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test using GraphPad Prism Version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, USA).

Results

Intraoral biofilm (in vivo) and microcosm biofilm (in vitro) formations on Ti6AI4V and Y-TZP

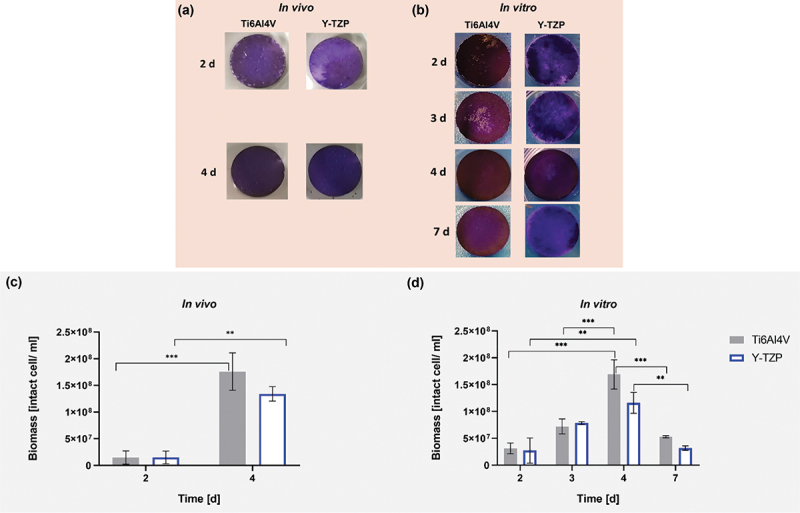

Both specimens, Ti6AI4V and Y-TZP, were entirely covered by biofilm after four days under in vivo and in vitro conditions (Figure 2a,b). On Ti6Al4V, the intact cells after four days under in vitro conditions were comparable (1.69 × 108 cells/mL) to those under in vivo conditions (1.76 × 108 cells/mL). Similarly, on Y-TZP, the intact cells under in vitro conditions were equivalent (1.16 × 108 cells/mL) to those under in vivo conditions (1.34 × 108 cells/mL) (Figure 2c,d). After 7 days of in vitro, the intensity of biofilm formation decreased on Y-TZP (Figure 2b), and the intact cells also reduced on both specimens (Figure 2d). From intact cell quantification, the bacterial growth on Ti6AI4V over the period under in vivo and in vitro was more significantly different with p < 0.001 than on Y-TZP with p < 0.01. However, the growth on both specimens in the same incubation time was not significantly different.

Figure 2.

Crystal violet-stained biofilm under in vivo (a) and in vitro (b) conditions on specimens during incubation. Viability of biofilm grown on Ti6AI4V and Y-TZP under in vivo (c) and in vitro (d) conditions. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, indicating significance with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Experiments were conducted in triplicates (n = 3).

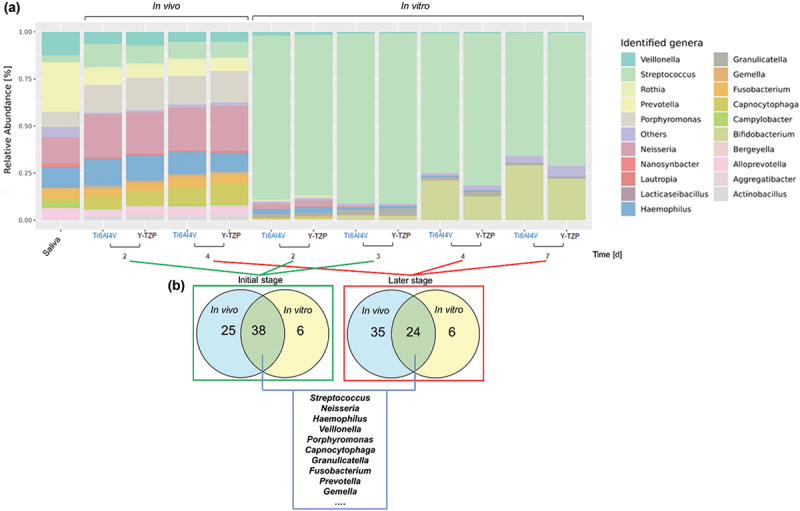

Microbial compositions of biofilm on specimens under in vivo and in vitro conditions

Saliva supports the formation of AEP, which plays a critical role in biofilm development. This is indicated by the large relative diversity of Veillonella, Prevotella, Neisseria, and Haemophilus observed in the saliva inoculum, whose microbial composition closely resembled that found under in vivo conditions (Figure 3a). When comparing in vitro and in vivo results, there was a marked increase in Streptococci under in vitro conditions on each surface (Figure 3a). Based on overlap of genera (Figure 3b), 60.31% of the genera present in vivo were also detected in vitro during the early stage, while 41% of the in vivo genera were found in vitro during the late stage. Despite the increase in Streptococci, the top 10 bacterial strains representative of the mouth were present in both in vivo and in vitro conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) The relative abundance of oral microbial genera in saliva (control) and in biofilms growing under in vivo and in vitro conditions on Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP. (b) The Venn diagrams show the number of overlapping and top −10 genera under in vivo and in vitro conditions with initial (in vivo: after 2 days; in vitro: after 2 and 3 days) and later (in vivo: after 4 days; in vitro: after 4 and 7 days) stages of biofilm formation.

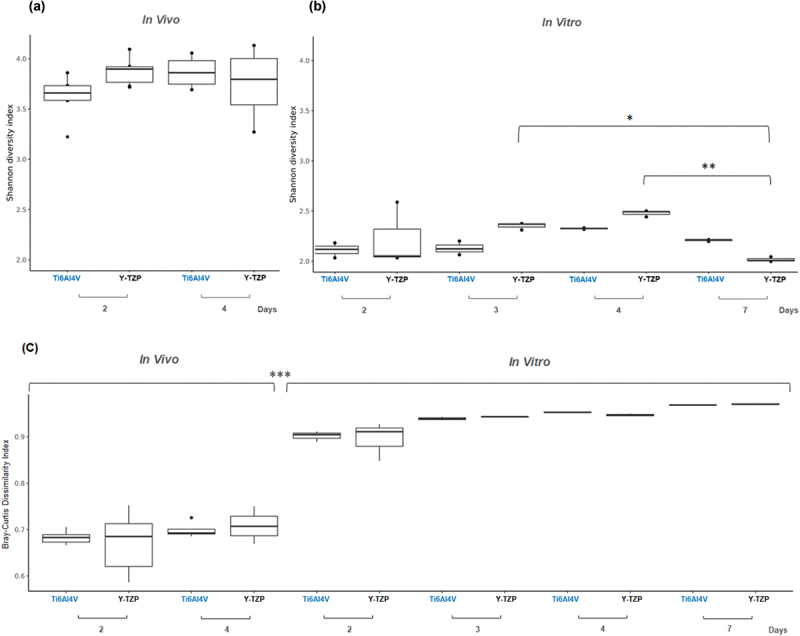

Alpha diversity, measured using the Shannon index, was assessed for each ecosystem, as shown in Figure 4a for the in vivo biofilm and Figure 4b for the in vitro biofilm. The analysis revealed no significant change in the microbial composition of the in vivo biofilm over the observed period. In contrast, a significant difference was observed in the in vitro biofilm on Y-TZP between the 3-day and 7-day biofilms, as well as between the 4-day and 7-day biofilms. Figure 4c shows the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity indexes between the saliva inoculum and both in vivo and in vitro biofilms. The results revealed a significant difference, with in vivo biofilms showing higher similarity to the saliva samples compared to in vitro biofilms.

Figure 4.

The Shannon diversity index of biofilms from in vivo (a) and from in vitro (b) tests. (c) The Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index between in vivo biofilms and in vitro biofilms compared to saliva inoculum samples.

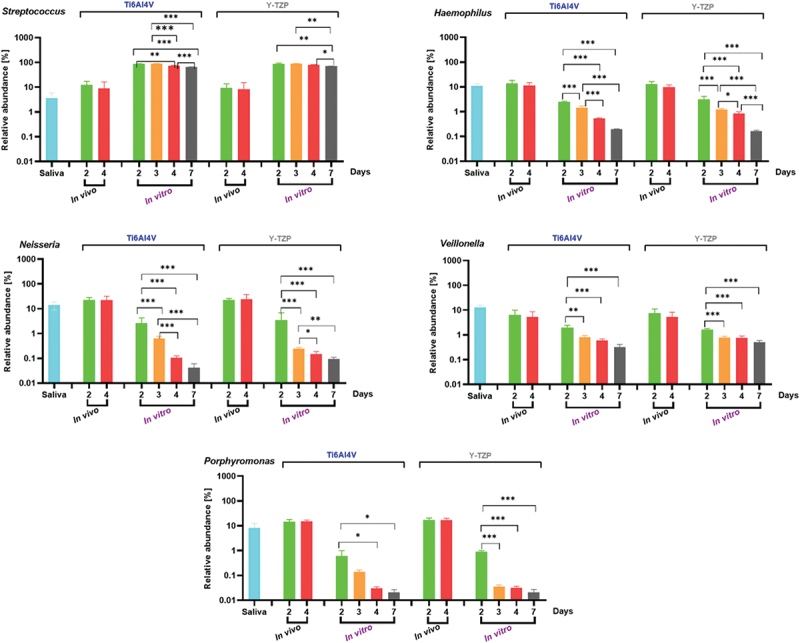

From top 10 overlapping genera in both conditions and stages, Streptococcus, Neisseria, and Haemophilus, were identified as facultative anaerobes and initial colonizers. It was shown in Figure 5 that Streptococcus exhibited relative abundances exceeding 60% of in vitro biofilms on both specimens, contrasting with levels below 13% of in vivo biofilms. Neisseria and Haemophilus maintained similar relative abundances after 2 and 4 days under in vivo condition on both specimens, while gradually declined over time under in vitro condition. Veillonella was present across all conditions and was constantly observed on Y-TZP under in vitro condition. Porphyromonas was consistently observed under in vivo conditions but showed a gradual reduction under in vitro conditions. After 3 days of incubation under in vitro condition, the relative abundance of Porphyromonas was three times higher on Ti6AI4V compared to Y-TZP.

Figure 5.

The relative abundance (%) of individual bacterial genera in saliva as a control, and in intraoral biofilms (in vivo) and microcosm biofilms (in vitro) grown on the surfaces. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, indicating significance with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Experiments were performed at least in triplicates (n = 3) for each condition.

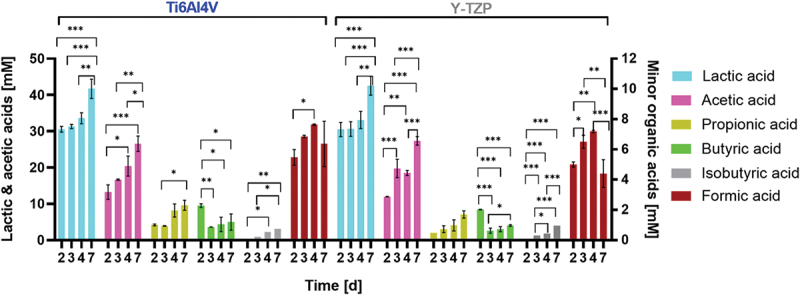

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) production by biofilm during incubation under in vitro conditions

Under in vitro condition, twice refreshments per day of medium could not avoid pH decrease, which was constantly observed on both specimens, Ti6AI4V and Y-TZP, during incubation but not below pH 5.1. Under in vitro conditions, SCFA production over time (Figure 6) demonstrated shifts in oral microbiome metabolism, with lactic and acetic acids as the primary metabolic products. The production of these acids correlated with an increase in biofilm biomass, reflecting active metabolic processes within the biofilm. Notably, the significant rise in lactic and acetic acids from the initial stage (2–3 days) to the final stage (4–7 days) of biofilm incubation corresponded with the increased relative abundance of Bifidobacteria on Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP surfaces (Figures 3). Butyric acid exhibited a unique trend, with a significant decrease in concentration from 2 to 3 days of biofilm formation on both surfaces (p < 0.01 for Ti6AI4V and p < 0.001 for Y-TZP). Based on the significantly different production of acetic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, and formic acid during incubation, the metabolic activity of biofilm was more dynamic on Y-TZP than on Ti6Al4V.

Figure 6.

Production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) during biofilm incubation under in vitro conditions. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was applied for statistical analysis, indicating significance with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

Discussion

While several studies have explored in vitro biofilm models, our study provides valuable insights by uniquely comparing biofilm formation in both in vitro and in vivo settings, using the same materials and standardized saliva from healthy donors. This approach addresses key challenges: ethical restrictions on novel materials, reliance on participant compliance [28], and the reduction of animal experiments.

After 4 days of incubation, crystal violet analysis confirmed complete biofilm coverage on both Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP specimens (Figure 2a), with similar cell viability as determined by IFC with the BactoBox (Figure 2b). Although cell viability significantly declined after 7 days in the in vitro setup, indicating that a four-day incubation period was optimal for simulating intraoral biofilm formation, practical constraints also supported this duration. Specifically, ethical considerations limited the duration of in vivo biofilm studies, making direct comparisons beyond 4 days challenging. Thus, the similarity in cell viability between in vivo and in vitro conditions at 4 days reinforced our choice of this time point as a representative model for biofilm formation.

Another in vitro study [28] reported complete biofilm coverage within one day. However, the test specimens in that study were made of resin composite, making a comparison with our results less meaningful since biofilm development depends on various parameters, such as material composition, surface energy, hydrophobicity, and surface roughness [1,2]. In our study, a titanium alloy and zirconia material with a roughness value of Ra < 0.2 µm were used. It is known that surface roughness above Ra = 0.2 µm increases biofilm accumulation, while values below this do not further reduce bacterial adhesion [29]. This roughness value is preferred in oral implantology for surfaces exposed to the oral cavity, where bacterial biofilm adhesion is undesirable. The full coverage of our platelets with biofilm only after 4 days may be related to this surface roughness value.

Regarding microbial composition of biofilm in this study,16S rRNA gene analysis revealed that in vivo biofilm exhibited a more diverse community compared to the in vitro biofilm, which was dominated by Streptococcus. However, dominant oral genera such as Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Veillonella, and Porphyromonas, along with other oral bacteria, which play a crucial role in representing oral conditions, were identified in both settings, albeit with different relative abundances.

Our study supports and extends previous findings regarding the microbial composition of oral biofilms. Specifically, our results were consistent with earlier studies that identified Streptococcus, Neisseria, and Haemophilus as key facultative anaerobes and initial colonizers. As shown in Figure 5a, Streptococcus constituted over 60% of the in vitro biofilms on both Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP specimens, which contrasts with its relative abundance of less than 13% in in vivo biofilms. This finding aligns with previous observations of Streptococcus as a predominant initial colonizer in biofilms [30,31].

Neisseria and Haemophilus, identified in our study as maintaining similar relative abundances after 2 and 4 days under in vivo conditions, were observed to gradually decline in relative abundance over time in in vitro conditions. This trend corroborates the dynamic nature of biofilm composition reported in other studies [32,33].

Veillonella was consistently present across all conditions in this study, underscoring its role as a key member of the biofilm community. This finding is supported by previous research, which observed that Veillonella utilizes lactic acid for growth and facilitates metabolic communication with other colonizers throughout all stages of biofilm development [31].

Porphyromonas, while consistently observed in in vivo conditions, showed a gradual reduction in relative abundance under in vitro conditions. Specifically, after 3 days of incubation, Porphyromonas was relatively more abundant on Ti6Al4V compared to Y-TZP, reflecting its competitive advantage on certain materials. This observation supports prior research on the material-specific effects on bacterial colonization and biofilm development [34].

We recognize the limitations of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in resolving microbial communities at the species level, particularly within complex genera such as Streptococcus. While 16S rRNA sequencing generally provides genus-level resolution, we employed our optimized pipeline, leveraging ASVs, DADA2, and QIIME2 for more accurate taxonomy classification, combined with the comprehensive SILVA reference libraries. Additionally, we employed the Quick-16S NGS Library Prep Kit (Zymo Research) with novel primers to enhance phylogenetic coverage and achieve improved species-level resolution for human microbiome profiling.

Our analysis identified Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus parasanguinis, Streptococcus gordonii, and Streptococcus sanguinis (Appendix Figure 4, Appendix Table 3, and Appendix Table 4). These species are recognized as homeostatic commensals and indicators of good oral health, as they help maintain a balanced host-microbiota equilibrium, inhibit pathogenic species, and reduce inflammatory responses [35–37]. The presence of these species supports the reliability of our healthy donor samples and their saliva for in vitro testing. However, species-level identifications should be interpreted with caution due to the inherent limitations of 16S rRNA gene sequencing in differentiating closely related species within the same genus [38,39].

Sucrose is used in in vitro tests to accelerate biofilm formation and promote exopolysaccharide (EPS) synthesis more effectively than other sugars [18,40]. Although sucrose’s utilization causes a decrease of pH during incubation – even with the medium refreshed twice daily [17], it remains crucial for efficient biofilm formation in the in vitro model. However, we recognize that this does not fully replicate the dietary habits of all individuals, as many people consume varying amounts of sugars [36].

Our study utilized a static model due to its practical advantages, including high reproducibility using a 24-well plate, simplicity, and no requirement for specialized equipment [2]. However, a static model faces challenges with pH control, as sucrose-induced acid production leads to significant pH decrease. To address this, we explored the impact of different PIPES buffer concentrations on pH stabilization. Our results showed that a PIPES concentration of 50 mM improved genera overlap in the in vitro biofilm compared to 10 mM PIPES, as shown in Appendix Figure5. While dynamic systems, such as a bioreactor or BioFlux systems, could offer continuous control over sucrose supply and pH stabilization [28], optimizing static models with improved buffering strategies presents a practical alternative.

Furthermore, the significant decrease in pH due to sucrose metabolism indicates elevated SCFA production over time, providing insights particularly into lactic acid production kinetics by the oral biofilm [41], which was mainly produced by common genera of oral lactic acid bacteria (LAB), namely Streptococcus and Lactobacillus. Besides primarily producing lactic acid, LAB can also convert carbohydrates into moderate amounts of acetic acid and formic acid. The high relative abundance of Bifidobacterium after 4 days in vitro was a consequence of pH drop-triggered biofilm, where the environment became dominated by increasingly acidogenic and aciduric, including Bifidobacteria and Scardovia [36,42]. Those two genera primarily produced acetic acid [43], as evidenced by the elevated acetic acid production over the period shown in Figure 6. On the other hand, the elevated concentration of propionic and butyric acids was reported to be associated with aggressive periodontitis [44]. While butyric acid was linked to periodontal pathogens [5,45], formic acid showed an antagonistic relationship with butyric acid, indicating their potential as markers for biofilm development and periodontitis treatment [46].

Conclusion

This study demonstrated comparable biofilm coverage and cell viability on Ti6Al4V and Y-TZP surfaces under both in vivo and in vitro conditions after four days. Although in vivo biofilm had a more diverse bacterial community than in vitro, the ten most representative oral cavity bacteria were still detectable in vitro. These findings underscore the potential of this efficient methodological approach using a static model to simulate natural oral biofilm formation, providing valuable insights into biofilm dynamics and serving as a valuable tool for future research on innovative implant-abutment material surfaces. Moreover, this saliva model appears suitable for in vitro studies with other restorative materials, warranting further investigation in future research.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study is funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) with project number 418670251 (WO 1576/6-1 and FI 975/30-2).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

R.N.C. Utomo, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised manuscript; A.L. Palkowitz, contributed to conception, design, interpretation, and critically revised manuscript. L. Gan, contributed to data analysis, interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. A. Rudzinski, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and critically revised the manuscript. J. Franzen, contributed to design and critically revised the manuscript. H. Ballerstedt, contributed to interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. M. Zimmermann, contributed to design and critically revised the manuscript. L.M. Blank, contributed to design, interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. S. Wolfart and H. Fischer contributed to conception, design, and critically revised the manuscript; T. Tuna, contributed to conception and design, interpretation, drafted and critically revised manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2024.2424227

References

- [1].Hao Y, Huang X, Zhou X, et al. Influence of dental prosthesis and restorative materials interface on oral biofilms. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3157. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kreth J, Merritt J, Pfeifer CS, et al. Interaction between the oral microbiome and dental composite biomaterials: where we are and where we should go. J Dent Res. 2020;99(10):1140–11. doi: 10.1177/0022034520927690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Derks J, Tomasi C.. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(16):S158–171. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Klinge B, Lundstrom M, Rosen M, et al. Dental implant quality register—a possible tool to further improve implant treatment and outcome. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(18):145–151. doi: 10.1111/clr.13268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Leonov GE, Varaeva YR, Livantsova EN, et al. The complicated relationship of short-chain fatty acids and oral microbiome: a narrative review. Biomedicines. 2023;11(10):2749. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11102749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mann ER, Lam YK, Uhlig HH. Short-chain fatty acids: linking diet, the microbiome and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24(8):577–595. doi: 10.1038/s41577-024-01014-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Subramani K, Jung RE, Molenberg A, et al. Biofilm on dental implants: a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24(4):616–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Li X, Shang L, Brandt BW, et al. Saliva-derived microcosm biofilms grown on different oral surfaces in vitro. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2021;7(1):74. doi: 10.1038/s41522-021-00246-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chawhuaveang DD, Yu OY, Yin IX, et al. Acquired salivary pellicle and oral diseases: a literature review. J Dent Sci. 2021;16(1):523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sang T, Ye Z, Fischer NG, et al. Physical-chemical interactions between dental materials surface, salivary pellicle and streptococcus gordonii. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2020;190:110938. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kunrath MF, Gerhardt MDN. Trans-mucosal platforms for dental implants: strategies to induce muco-integration and shield peri-implant diseases. Dent Mater. 2023;39(9):846–859. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2023.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Palkowitz AL, Tuna T, Bishti S, et al. Biofunctionalization of dental abutment surfaces by crosslinked ecm proteins strongly enhances adhesion and proliferation of gingival fibroblasts. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(10):e2100132. doi: 10.1002/adhm.202100132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yang Z, Liu M, Yang Y, et al. Biofunctionalization of zirconia with cell-adhesion peptides via polydopamine crosslinking for soft tissue engineering: effects on the biological behaviors of human gingival fibroblasts and oral bacteria. RSC Adv. 2020;10(11):6200–6212. doi: 10.1039/C9RA08575K [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Holban AM, Farcasiu C, Andrei OC, et al. Surface modification to modulate microbial biofilms—applications in dental medicine. Materials (Basel). 2021;14(22):6994. doi: 10.3390/ma14226994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Herraez-Galindo C, Rizo-Gorrita M, Maza-Solano S, et al. A review on cad/cam yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal (y-tzp) and polymethyl methacrylate (pmma) and their biological behavior. Polym (Basel). 2022;14(5):906. doi: 10.3390/polym14050906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hoque ME, Showva NN, Ahmed M, et al. RETRACTED: titanium and titanium alloys in dentistry: current trends, recent developments, and future prospects. Heliyon. 2022;8(11):e11300. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [17].Exterkate RA, Crielaard W, Ten Cate JM. Different response to amine fluoride by streptococcus mutans and polymicrobial biofilms in a novel high-throughput active attachment model. Caries Res. 2010;44(4):372–379. doi: 10.1159/000316541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Koo H, Falsetta ML, Klein MI. The exopolysaccharide matrix: A virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J Dent Res. 2013;92(12):1065–1073. doi: 10.1177/0022034513504218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Njoku DI, Guo Q, Dai W, et al. The multipurpose application of resazurin in micro-analytical techniques: trends from the microbial, catalysis and single molecule detection assays. TrAC Trends In Analytical Chem. 2023;167:117288. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2023.117288 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wagner AO, Markt R, Mutschlechner M, et al. Medium preparation for the cultivation of microorganisms under strictly Anaerobic/Anoxic conditions. JoVE. 2019;150(150):60155. doi: 10.3791/60155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Martin B, Chathoth K, Ouali S, et al. New growth media for oral bacteria. J Microbiol Meth. 2018;153:10–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Göbbels L, Poehlein A, Dumnitch A, et al. Cysteine: an overlooked energy and carbon source. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81103-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Straub D, Blackwell N, Langarica-Fuentes A, et al. Interpretations of environmental microbial community studies are biased by the selected 16s rrna (gene) amplicon sequencing pipeline. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:550420. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.550420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Di Tommaso P, Chatzou M, Floden EW, et al. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):316–319. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Merkel D. Docker: lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux J. 2014;2014(239):2. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The silva ribosomal rna gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Team RC. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. MSOR connections; 2014. p. 1. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/R%3A-A-language-and-environment-for-statistical-Team/659408b243cec55de8d0a3bc51b81173007aa89b. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kohno T, Kitagawa H, Tsuboi R, et al. Establishment of novel in vitro culture system with the ability to reproduce oral biofilm formation on dental materials. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21188. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00803-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bollen CM, Papaioanno W, Van Eldere J, et al. The influence of abutment surface roughness on plaque accumulation and peri-implant mucositis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;7(3):201–211. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mager DL, Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Haffajee AD, et al. Distribution of selected bacterial species on intraoral surfaces. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(7):644–654. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.2003.00376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. Central role of the early colonizer veillonella sp. in establishing multispecies biofilm communities with initial, middle, and late colonizers of enamel. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(12):2965–2972. doi: 10.1128/JB.01631-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Simon-Soro A, Ren Z, Krom BP, et al. Polymicrobial aggregates in human saliva build the oral biofilm. MBio. 2022;13(1):e0013122. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00131-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Teles FR, Teles RP, Uzel NG, et al. Early microbial succession in redeveloping dental biofilms in periodontal health and disease. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47(1):95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2011.01409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Naginyte M, Do T, Meade J, et al. Enrichment of periodontal pathogens from the biofilms of healthy adults. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5491. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41882-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Devine DA, Marsh PD, Meade J. Modulation of host responses by oral commensal bacteria. J Oral Microbiol. 2015;7(1):26941. doi: 10.3402/jom.v7.26941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lamont RJ, Koo H, Hajishengallis G. The oral microbiota: dynamic communities and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(12):745–759. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0089-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Whitmore SE, Lamont RJ. The pathogenic persona of community‐associated oral streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81(2):305–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07707.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong B-Y, et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5029. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13036-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Odom AR, Faits T, Castro-Nallar E, et al. Metagenomic profiling pipelines improve taxonomic classification for 16S amplicon sequencing data. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13957. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40799-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Du Q, Fu M, Zhou Y, et al. Sucrose promotes caries progression by disrupting the microecological balance in oral biofilms: an in vitro study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2961. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59733-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cuny L, Pfaff D, Luther J, et al. Evaluation of productive biofilms for continuous lactic acid production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2019;116(10):2687–2697. doi: 10.1002/bit.27080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Beighton D, Gilbert SC, Clark D, et al. Isolation and identification of bifidobacteriaceae from human saliva. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(20):6457–6460. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00895-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Barbour A, Elebyary O, Fine N, et al. Metabolites of the oral microbiome: important mediators of multikingdom interactions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2022;46(1). doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuab039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lu R, Meng H, Gao X, et al. Analysis of short chain fatty acids in gingival crevicular fluid of patients with aggressive periodontitis. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;43(11):664–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jiang Y, Brandt BW, Buijs MJ, et al. Manipulation of saliva-derived microcosm biofilms to resemble dysbiotic subgingival microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87(3). doi: 10.1128/AEM.02371-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Qiqiang L, Huanxin M, Xuejun G. Longitudinal study of volatile fatty acids in the gingival crevicular fluid of patients with periodontitis before and after nonsurgical therapy. J Periodontal Res. 2012;47(6):740–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.