Abstract

Background:

Loneliness in the elderly is of public health importance as it is a risk factor for adverse consequences. There is lack of data on loneliness among the elderly population of India, especially those residing in a rural community.

Aim:

To estimate loneliness and its association with depression and caregiver abuse.

Materials and Methodology:

A cross-sectional study was conducted in a rural health clinic in North India. 125 elderly persons were evaluated on the UCLA Loneliness Scale, Patient Health Questionnaire-15, Geriatric Depression Rating Scale‑30 (GDS), and Caregiver Abuse Screening (CASE) scale.

Results:

67.6 years was the mean age of the study’s subjects, with a mean number of years of education of 2.9. Most were female, married, and from lower socioeconomic status and belonged to a non-nuclear family. The prevalence of loneliness was 66.4%. Regarding specific features, subjects reported a lack of companionship (64.8%), being left out in life (45.2%), and being isolated from others (52.8%). The severity of depression, somatization, psychological and physical abuse, neglect abuse, and caregiver abuse had a significant positive association with loneliness. Those with a presence of loneliness scored higher on GDS and CASE than those without. Those who were single at the time of the study reported significantly more loneliness than married ones. Those from nuclear families and middle socioeconomic status reported a significantly higher level of loneliness.

Conclusion:

Loneliness among the elderly rural population is significantly high. The severity of loneliness is associated with higher severity of depression, somatization, and caregiver abuse.

Keywords: Loneliness, elderly, rural, caregiver abuse, depression, somatization

Key Messages:

The prevalence of loneliness is very high in elderly people living in rural areas and has a significant association with depression, somatic symptoms, and caregiver abuse. It is essential to address these pertinent issues among rural older adults.

Loneliness among the elderly as a condition is considered to be of major public health and social concern, which may lead to serious health-related consequences such as depression, poor psychological health, poor quality of life, etc. 1 Loneliness can be understood as “an undesirable subjective experience, arising from unfulfilled intimate and social needs”. 2 Many studies across the globe have evaluated loneliness in elderly. A meta-analysis including 39 studies from 29 countries showed a pooled prevalence of loneliness to be 28.5% (95% confidence interval: 23.9–33.2%). 3 In terms of loneliness severity, the pooled prevalence of severe and moderate loneliness was 7.9% (95%CI: 4.8–11.6%) and 0.9% (95%CI: 21.6–30.3%), 3 respectively. In view of the high prevalence of loneliness, countries such as the United Kingdom and Japan have started separate ministries to address this public health crisis. 4 Emerging literature suggests that loneliness has a number of adverse impacts in the form of poor mental well-being, poor quality of life, worsening of existing physical health problems, and increased risk of physical and psychological problems such as frailty, cardiovascular diseases or premature mortality, depression, dementia, anxiety, etc.5–10 In a literature from the rural areas of other countries, loneliness was found to be significantly associated with a poor predictor of outcome of depression 11 and poor quality of life 12 and was related to a poor sense of worth and self-esteem and increased risk of anxiety disorder. 13 However, only a few studies have evaluated the relationships between loneliness and somatic symptoms (SSs). Because of the physical nature of SSs, they are perceived as worrisome or unpleasant and can significantly influence the individual’s feelings, thoughts, and behavior, which can further lead to the occurrence of mental disorders.14,15 The available evidence suggests that the negative impact of loneliness on psychological and physical health is almost comparable with the adverse consequences of smoking, alcohol, or obesity. 16 The recent data also suggests that loneliness among the elderly is associated with more health problems and with more frequent use of health and social care services.17,18 In terms of the factors related to loneliness, data suggest that the elderly living alone tend to experience more loneliness because of inadequate family support, social support, or interaction. 19

Although a large amount of data on loneliness is available from Western countries, there is a scarcity of data on loneliness in India. A multicentric study from India estimated the prevalence of loneliness among patients with depression to be 77.3%. 15 Another study assessed the prevalence of loneliness and its correlates among the elderly attending a rural health clinic (RHC) for a non-communicable disease. In that study, 55.4% of the elderly reported the presence of loneliness, and half had either high (18.6%, N = 55), moderately high (17.6%; N = 52%), or moderate (13.2%, N = 39) levels of loneliness. 20 Though studies from India have evaluated the prevalence of loneliness in the clinical population, there is a lack of data from the general rural population. In addition, no Indian study has evaluated the association of SSs with loneliness. Accordingly, the current study aimed to estimate loneliness and its association with depression and caregiver abuse.

Materials and Methodology

Study Design and Site

The indexed cross-sectional observational study was done at an RHC in a small village, Kheri, in the northern part of Haryana. RHC is the catchment area of the Community Clinic of a tertiary care center in North India. The study’s participants provided a written informed consent. The village has 288 families, with a total population of 2,051 and the male-to-female ratio of 1.29:1. The illiteracy rate in the village was reported to be 37%. Majority of the people are entirely dependent on agriculture.

The study was granted approval by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Participants

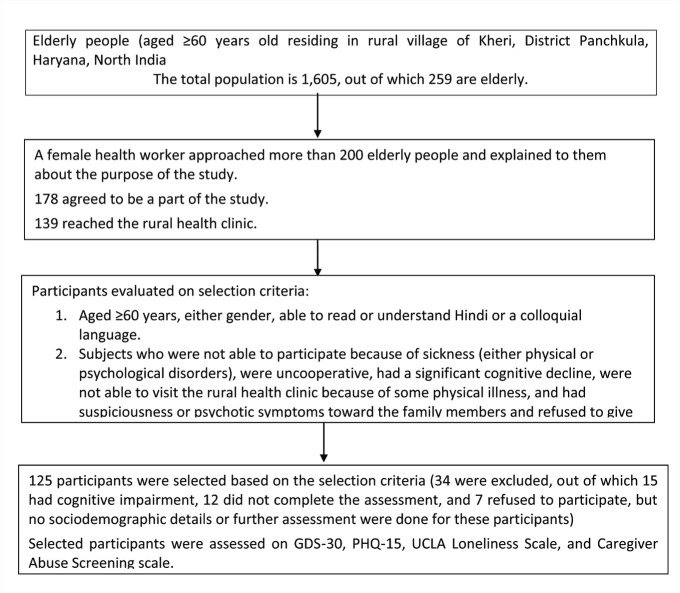

Participants aged ≥60 years were included in the study. However, subjects who were too sick to participate (i.e., not able to answer the questions due to severity of their health condition), were uncooperative, had a significant cognitive decline, were not able to visit the RHC because of some physical illness, had suspiciousness or psychotic symptoms toward their family members, and refused to give consent were excluded from the study. For this study, the participants were identified by a female health worker, who explained the purpose of the research to the participants. Those who agreed were brought to the RHC along with their caregivers or family members (who were aware of the patient’s mental and physical health status). Participants were interviewed in detail at the RHC by a qualified psychiatrist after obtaining consent. Those who were illiterate or had fewer number of years of education were explained in a colloquial language about the aim and objectives of the study. Those who agreed gave a written informed consent, which was obtained from their preference of caregivers. Those who were found to suffer from psychological disorders were offered treatment. Those who reported the presence of caregiver abuse were educated about their right and how they could take legal support. Confidentiality and privacy were ensured for the same. The study sample comprised 125 patients (Figure 1) The study was conducted from January to June 2022.

Figure 1. Depicting the Enrollment of Subjects.

Assessment

Patients were assessed on the Geriatric Depression Rating Scale-30 (GDS), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ), UCLA Loneliness Scale, and Caregiver Abuse Screening (CASE) scale. A paper emerging from this study focused on the prevalence of depression and validation of the geriatric depression scale has already been published. 21

UCLA Loneliness Scale

This 20-item tool assesses each item on a 4-point Likert scale, and it evaluates one’s subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation. For estimating the prevalence, 3 out of the 20 items are used. The three items include “lack of companionship,” “left out in life,” and “being isolated from others.” Each of the three items is rated as “sometimes/often,” indicating the presence of loneliness. Psychometric properties for the scale are good with high coefficient α (0.89–0.94), and test–retest reliability (r = 0.73). The scale has adequate construct and convergent validity.22,23

Caregiver Abuse Screen

This self-rated screening tool has a dichotomous (yes/no) response with 8 items. If caregivers respond, the answer “yes” to any question counts as 1 point. Hence, the score ranges from 0 to 8. Those who scored 4 or more were considered as “abuse likely.” The scale measures the psychological, physical, and financial or neglect abuse. Previous studies have noted excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).24,25 The participants were asked to rate various scales on their own. If they could not do that, these scales were read to them in Hindi (as the scale was translated into Hindi) and a health worker recorded the responses. The caregivers were similarly assessed on CASE, which has been validated and used among elderly people in previous studies.26,27

Statistical Analysis

Frequency and percentage were computed for categorical variables, and mean (SD) was calculated for continuous variables. For comparison, a t-test or Mann-Whitney test and chi-square were used. Correlations were evaluated using the Spearman/Pearson correlation analysis. To examine the relationship of loneliness with other variables such as caregiver abuse, somatization, etc., a regression analysis was done.

Results

Sociodemographic Profile

125 eligible elderly were recruited in the present study. The mean age was 67.6 (SD: 7.7) years, with a mean number of years of education of 2.9 (SD: 4.5). Most of the participants were from lower socioeconomic status (73.6%), married (64.0%), and female (62.4%) and belonged to a non-nuclear family setup (77.6%).

Prevalence of Loneliness

The prevalence of loneliness evaluated based on the three items of the UCLA Loneliness Scale was 66.4%. In terms of specified items of loneliness, 64.8% had a lack of companionship, 45.2% had been left out in life, and 52.8% had been isolated from others. The overall mean UCLA Loneliness Scale score was 30.7 (SD: 15.7) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Loneliness.

| Variables | Frequency (%)/Mean (SD) |

| Lack of companionship | 64.8 |

| Being left out in life | 45.2 |

| Being isolated from others | 52.8 |

| Loneliness | |

| Present* | 66.4 |

| Absent | 33.6 |

| Overall score | 30.7 (15.7) |

*Participants with responses for any of the three items in the form of “sometimes/often” were considered to have loneliness.

Symptom Profile

On GDS-30, the mean total score was 12.9 (SD: 10.3), with 29.6% having severe depression and 17.6% having mild depression. On PHQ-15, the overall mean score was 5.8 (SD: 4.6). On PHQ-15, 4.8% had severe somatization, 16.8% had moderate somatization disorder, and 28.0% had mild somatization disorder (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symptom Profile of Study Participant.

| Variables | Frequency (%)/Mean (SD) |

| Geriatric Depression Scale-30 No depression (≤9) Mild depression (10–19) Severe depression (≥20) Overall score on GDS-30 |

66 (52.8) 22 (17.6) 37 (29.6) 12.9 (10.3) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-15 No somatization (0–4) Mild somatization (5–9) Moderate somatization (10–14) Severe somatization (≥15) Overall score on PHQ-15 |

63 (50.4) 35 (28.0) 21 (16.8) 6 (4.8) 5.8 (4.6) |

In terms of abuse from the caregiver, as assessed on CASE, 43.2% reported the presence of caregiver abuse. On the sub-domain, 37.6% had a presence of physical and psychological abuse, and 35.2% had a presence of neglect from their caregivers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Caregiver Abuse.

| Variables | Frequency (%)/Mean (SD) |

| Caregiver abuse Present (≥4) Absent (1–3) Overall score on CASE |

54 (43.2) 71 (56.8) 2.9 (2.8) |

| Physical and psychological abuse (item numbers 1–4, 6, 8) Presence (score≥3) Mean score on physical and psychological abuse subdomain |

47 (37.6) 1.8 (1.6) |

| Neglect (item numbers 5 and 7) Presence (score >1) Mean score on neglect subdomain |

44 (35.2) 0.5 (0.7) |

Correlates of Loneliness

The overall mean score of the total UCLA LS score was used to assess the correlation. It was found that higher loneliness had a higher severity of depression, caregiver abuse, and a higher severity of somatization. Higher loneliness was associated with participants with lower family income per month (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of Loneliness with Sociodemographic and Symptoms Profile of Patients.

| Variables | Overall Loneliness Score | Overall Loneliness Scale# |

| Age | 0.060 (0.506) | 0.060 (0.506) |

| No. of years of education | 0.024 (0.793) | 0.024 (0.793) |

| Income of family | –0.206 (0.021)* | –0.206 (0.021) |

| GDS score | 0.399 (<0.001)*** | 0.399 (<0.001)*** |

| PHQ-15 score | 0.198 (0.027)* | 0.198 (0.027) |

| CASE psychological and physical abuse score | 0.337 (<0.001)*** | 0.337 (<0.001)*** |

| CASE neglect score | 0.318 (<0.001)*** | 0.318 (<0.001)*** |

| CASE overall score | 0.356 (<0.001)*** | 0.356 (<0.001)*** |

#Adjusted p value: .00714 (Bonferroni correction). *p < .05; ***p < .001

Comparison of Prevalence of Loneliness with Sociodemographic and Clinic Profile

In the present study, those with a presence of loneliness significantly scored a higher score on the GDS (t: 2.584; p: .011) and CASE (t: 3.779; p <.001). In the study, those who were single at the time of the study reported significantly more loneliness (x2: 7.890; p: .005) than married ones. Those from nuclear families significantly reported a higher level of loneliness (x2: 18.259; p < .001) than those from joint/extended families. Those from middle socioeconomic status significantly reported a higher severity of loneliness than those who were from higher socioeconomic status (x2: 6.45; p < .001).

Predictors of Loneliness Among the Elderly Population

To evaluate the effect of independent variables on loneliness, linear regression analysis was done with both stepwise and enter methods. As evident from Table 5, with the enter method, 20.8% of the variance was explained by the overall score of GDS, the overall score of PHQ-15, the overall score of CASE, and the mean income of the patient. The maximum variance of loneliness was affected by caregiver abuse, followed by the income of the family and an overall score of depression on GDS and somatization (overall score on PHQ-15).

Table 5.

Predictors of Loneliness Among the Elderly Population.

| Variables | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Standard Error of Estimates | df1–df2 (F Change) |

| Income of family, GDS score, PHQ-15 score, CASE psychological and physical abuse score, CASE neglect score, and CASE overall score | 0.496 | 0.246 | 0.208 | 13.93911 | 6–118 (0.000) |

| CASE overall score | 0.356 | 0.127 | 0.120 | 14.69680 | 1–123 (0.000) |

| Income of family | 0.439 | 0.193 | 0.180 | 14.18813 | 1–122 (0.002) |

| GDS overall score | 0.482 | 0.233 | 0.214 | 13.890173 | 1–122 (0.014) |

Discussion

The present study evaluated loneliness among the elderly living in a rural community. In the present study, about two-thirds (66.4%) had loneliness. The available literature from different countries has reported “the prevalence of loneliness to vary from 11.5% to 77.3%.”15,28,29 The present study’s finding of the prevalence of loneliness is also in the reported range of 55–77.3% in the clinic population in India.15,20 In terms of specific features of loneliness, 64.8% reported a “lack of companionship,” 45.2% “being left out in life,” and 52.8% “being isolated from others.” These findings are similar to those of a previous study in India. 20 The present study’s findings are in the reported range and suggest that loneliness is highly prevalent among the elderly living in rural communities. When we compare the findings with a systematic review conducted by Chawla et al., 3 loneliness is much higher in the present study. The reasons could be many; for example, in the systemic review, most studies evaluated loneliness based on a single questionnaire from developed countries and urban cities, noted geographical differences, and used different cut-off scores. This high prevalence suggests an urgent need to carry out large-scale studies to evaluate the prevalence of loneliness and develop measures to address loneliness.30,31

In terms of correlates of loneliness, the current study suggests that the severity of loneliness had a significant positive association with depression severity. A large number of studies have reported a positive association between loneliness and depression.15,20,30,31 Also, there is a lot of evidence that heightened feelings of loneliness can predict an increased future risk of depressive symptoms or depressive disorders.32,33 A longitudinal study reported that greater loneliness at baseline predicted poorer health-related QOL and poor outcomes of depressive disorder at follow-up. 11 However, the association between depression and loneliness should not be interpreted as cause and effect. There may be a bidirectional relationship between these two conditions. There is a need for more longitudinal studies to see the associations.

The present study’s findings also suggest that the severity of loneliness is associated with a higher level of caregiver abuse. Previous studies from developed countries have also reported a similar association. A study from the USA has shown that those elderly who felt lonely were prone to be victims of any elder abuse (odds ratio [OR]: 2.06; confidence interval: 1.68–2.53]). Precisely, it was reported that loneliness was associated with increased risks of financial exploitation (CI: 1.11–1.92; OR: 1.46), psychological abuse (CI: 2.0–3.39; OR: 2.61), and caregiver neglect (CI: 1.12–2.50; OR: 1.67). 34 However, for a better understanding of the association of elder abuse with loneliness, there is a need for a more longitudinal prospective study to evaluate the change in symptoms of loneliness and the subsequent risk for elderly mistreatment.

Along with this, it is important to assess all the lonely elderly for any abuse and also highlight the need to further explore the relationship between loneliness and elderly abuse in contributing to the global understanding of these important associations. In addition, a combination of loneliness, depression, or caregiver abuse might have an adverse impact on the well-being of the elderly. Therefore, it is recommended to perform a comprehensive geriatric assessment of the elderly, availing medical or psychological services for early identification of and intervention for loneliness.

In the present study, loneliness was associated with a higher severity of somatization. Previous studies have not evaluated this association. This association can be understood from the point that somatization is a manifestation or an epiphenomenon of depression. Further, SSs may be the manifestation of loneliness. Hence, clinicians should routinely assess all the elderly presenting with unexplained medical symptoms for the presence of loneliness and abuse.

Loneliness was found to be significantly more in single (widowed/divorced/unmarried), from a nuclear family setup and middle socioeconomic status. These findings can be understood as a reflection of social isolation, also associated with loneliness. The existing literature15,35,36 also supports the association of loneliness with these demographic variables. Even a study conducted by Jiang et al. 37 reported that elderly widows residing in rural areas were more prone to loneliness. Having a spouse is the strongest connection in rural areas in family-related social networks. 38 Widowed or separated women as a group were found to be lonelier than others, which might be because they could not overcome the trauma of the loss of their spouses. Hence, it becomes almost impossible to develop new connections as they lose interest in their environment or surroundings for an extended period. In the present study, having a nuclear family setup increases loneliness, which is also evident in the existing literature. It has been reported in a large epidemiological study that those living with their children in a joint family setup or having a strong family relationship have a lesser prevalence of loneliness. 39 Hence, the emphasis should be on strengthening family relationships and social participation to enhance social connectedness.

The present study has certain limitations. These include cross-sectional assessment and small sample size. The elderly participants were not assessed in detail for other correlates of loneliness such as physical comorbidity, non-communicable diseases, etc. Other factors, such as social support, coping, personality traits, and physical disabilities, were not assessed. Future longitudinal multicentric studies should more comprehensively evaluate the prevalence and correlates of loneliness.

Conclusion

The present study suggests that the prevalence of loneliness in the rural community sample is 66.4%. The severity of loneliness is associated with higher severity of depression, somatization, and caregiver abuse. There is a need to carry out more research in different communities at the national level. The research should be a multicentric study, including different geographical facilities, a uniform definition of loneliness and cut-off score, and the inclusion of qualitative data. Findings also suggest that the Government of India should initiate some measures and policies to deal with the presence of high levels of loneliness and associated psychological problems. Policies such as promoting ageing in one’s own home by providing income security and access to healthcare facilities and services to facilitate and sustain dignity in old age.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the participants for their contribution and completion of studies.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Declaration Regarding the Use of Generative AI: None used.

Ethical Approval and Patient Consent Statements: The study was approved by the ethics committee of the institute and all the participants were enrolled after obtaining written informed consent.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Forbes A. Caring for older people: loneliness. BMJ, 1996; 313(7053): 352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peplau LA and Perlman D. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and practice, perspectives on loneliness. New York: John Wiley, 1982, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla K, Kunonga TP, Stow D, et al. Prevalence of loneliness amongst older people in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 2021; 16(7): e0255088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang TJ, Rabheru K, Peisah C, et al. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Psychogeriatr, 2020. Oct; 32(10): 1217–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearns A, Whitley E, Tannahill C, et al. Loneliness, social relations and health and well-being in deprived communities. Psychol Health Med, 2015; 20(3): 332–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJH, Beekman ATF, et al. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2014; 85(2): 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale CR, Westbury L and Cooper C.. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing, 2018; 47(3): 392–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valtorta NK, Moore DC, Barron L, et al. Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: a systematic review. Am J Pub Health, 2018; 8(4): e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci, 2015; 10(2): 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Just SA, Seethaler M, Sarpeah R, et al. Loneliness in elderly inpatients. Psychiatr Q, 2022. Dec; 93(4): 1017–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Marston L, et al. Loneliness as a predictor of outcomes in mental disorders among people who have experienced a mental health crisis: a 4-month prospective study. BMC Psychiatry, 2020. May 20; 20(1): 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Çam C, Atay E, Aygar H, et al. Elderly people’s quality of life in rural areas of Turkey and its relationship with loneliness and sociodemographic characteristics. Psychogeriatrics, 2021. Sep; 21(5): 795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain B, Mirza M, Baines R, et al. Loneliness and social networks of older adults in rural communities: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Front Public Health, 2023. May 15; 11: 1113864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimsdale JE, Creed F, Escobar J, et al. Somatic symptom disorder: an important change in DSM. J Psychosom Res, 2013; 75(3): 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grover S, Avasthi A, Sahoo S, et al. Relationship of loneliness and social connectedness with depression in elderly: a multicentric study under the aegis of Indian Association for Geriatric Mental Health. J Geriatr Ment Health, 2018; 5(2): 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB and Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med, 2010; 7(7): e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taube E, Kristensson J, Jakobsson U, et al. Loneliness and health care consumption among older people. Scand J Caring Sci, 2015; 29(3): 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valtorta NK, Kanaan MGS, Ronzi S, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 2016; 102(13): 1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Hicks A, While AE. Loneliness and social support of older people in China: a systematic literature review. Health Soc Care Community, 2014; 22(2): 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover S, Verma M, Singh T, et al. Loneliness and its correlates amongst elderly attending non-communicable disease rural clinic attached to a tertiary care centre of North India. Asian J Psychiatry, 2019; 43: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehra A, Agarwal A, Bashar M, et al. Evaluation of psychometric properties of Hindi versions of Geriatric Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire in older adults. Indian J Psychol Med, 2021. Jul; 43(4): 319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell D, Peplau LA and Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA loneliness scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1980; 39(3): 472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell DW. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess, 1996; 66(1):20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reis M and Nahmiash D.. Validation of the Caregiver Abuse Screen (CASE). Can J Aging, 1995; 14(Suppl 2): 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reis M and Nahmiash D. When seniors are abused: a guide to intervention. North York, ON: Captus Press Inc, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakar H, Mahtab AK, Farshad S, et al. Validation study: the Iranian Version of Caregiver Abuse Screen (CASE) among family caregivers of elderly with dementia. J Gerontol Soc Work, 2019. Aug–Sep; 62(6): 649–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan A, Adil A, Ameer S, et al. Caregiver abuse screen for older adults: Urdu translation, validation, factorial equivalence, and measurement invariance. Curr Psychol, 2022; 41(6): 3816. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang K and Victor C.. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc, 2011; 31(8): 1368–1388. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loboprabhu S and Molinari V.. Severe loneliness in community‑dwelling ageing adults with mental illness. J Psychiatr Pract, 2012; 18(1): 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peerenboom L, Collard RM, Naarding P, et al. The association between depression and emotional and social loneliness in older persons and the influence of social support, cognitive functioning and personality: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord, 2015; 182: 26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A and Misra N. Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Ind Psychiatry J, 2009. Jan; 18(1): 51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuyen J, Tuithof M, de Graaf R, et al. The bidirectional relationship between loneliness and common mental disorders in adults: findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 2020. Oct; 55(10): 1297–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee SL, Pearce E, Ajnakina O, et al. The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms among adults aged 50 years and older: a 12-year population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry, 2021. Jan; 8(1): 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang B and Dong X.. The association between loneliness and elder abuse: findings from a community-dwelling Chinese ageing population. Innov Aging, 2018. Nov 11; 2(Suppl 1): 282. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu LJ and Guo Q.. Loneliness and health-related quality of life for the empty nest elderly in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res, 2007; 16(8): 1275–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newsom JT and Schulz R.. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychol Aging, 1996; 11(1): 34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang D, Hou Y, Hao J, et al. Association between personal social capital and loneliness among widowed older people. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020; 17(16): 57–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Hu M, Xiao S-Y, et al. Loneliness and depression among rural empty-nest elderly adults in Liuyang, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 2017; 7(10): e016091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Awang H, Rashid NFA, et al. Determinants of loneliness among mid-aged and older adults. IJCWED, 2022; 15(1): 33–41. [Google Scholar]