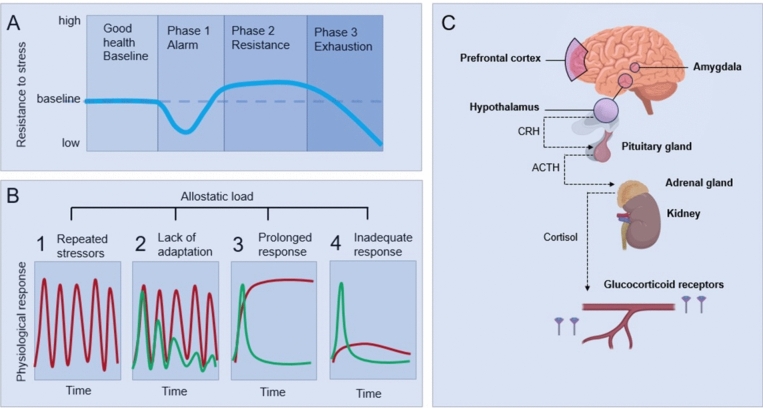

Fig. 2.

The general adaptation syndrome (GAS) (A), allostatic load model (B), and the pathway (C) that connects various stressors with symptoms and pathology. Effective coping to any stressful situation depends on the person’s cognitive appraisal of the stressful event (perceived stress), and the subsequent type of behavioral coping strategy used [167]. The GAS model (A) described how a stress response causes function (represented by the blue line) to decrease initially (phase 1). Adaptation occurs and this helps to resist the continued stress (phase 2). After a while this cannot be sustained anymore and exhaustion occurs (phase 3). The GAS model also explained the role of common neuroendocrine pathways for various challenges (sympathetic nervous systems and HPA axis) (C). The GAS model was further developed into the allostatic model (B) [169, 171]. Allostasis is a response to challenges whereby the setpoint will change. The most well studied allostatic responses to a range of challenges involve the sympathetic nervous systems and HPA axis (C). Activation of these systems, independent of the source of stress, releases catecholamines from nerve endings and adrenal medulla and leads to corticotropin secretion from the pituitary gland. Corticotropin, in turn, will stimulate the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortex and this will exert its effect through binding to glucocorticoid receptors in various target tissues, which can be up or downregulated. This is a fast and effective response. If this response is not immediately turned off, over time this increases the “allostatic load.” Allostatic load or eventually overload will affect many body systems causing wear and tear [169, 171].

Four situations are associated with allostatic load (panels B1–4; the red line represents problematic responses and the green line normal responses). The first and most obvious is frequently repeated stress (B1). A second situation would be inadequate adaptation to repeated stressors of the same type (B2). This can also result in prolonged exposure to stress hormones. The third would be a situation where there is an inability to shut off the stress response after termination of the stress (B3). An example of this is exercise training that induces allostatic load in the form of elevated sympathetic and HPA-axis activity, which may result in weight loss, amenorrhea, and even AN [182]. In the fourth type of allostatic load, there could be an inadequate response by one system and this could trigger a compensatory increase in another (B4). For example, if cortisol secretion fails to increase in response to stress, secretion of inflammatory cytokines (which are counter-regulated by cortisol) increases [183]. A range of challenges that an athlete faces (training load, competition stress, poor nutrition, poor sleep) can increase allostatic load, which can trigger a range of symptoms and clinical conditions