Abstract

Background and Objective

IcoSema is being developed as a subcutaneous once-weekly fixed-ratio combination of the once-weekly basal insulin icodec and the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist semaglutide. This study investigated the pharmacokinetics of icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema versus separate administration of each component in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

In a randomised, double-blind, three-period crossover study, 31 individuals with T2DM (18–64 years, body weight 80–120 kg, glycosylated haemoglobin 6.0–8.5%) received single subcutaneous injections of IcoSema (175 U icodec, 0.5 mg semaglutide), icodec (175 U) or semaglutide (0.5 mg) with 6–9 weeks’ washout. Pharmacokinetic blood samples were drawn up to 840 h post-dose.

Results

Icodec pharmacokinetics were unaffected by combining icodec with semaglutide. The 90% confidence interval (CI) of IcoSema/icodec was within 0.80–1.25 for total exposure (area under the curve from zero to last quantifiable observation; AUC0-t: ratio [90% CI] 1.06 [1.01; 1.12]) and maximum concentration (Cmax): 1.12 [1.06; 1.18]. Semaglutide AUC0–t was also unaffected by combination with icodec (IcoSema/semaglutide 1.11 [1.05; 1.17]). However, semaglutide Cmax was higher for IcoSema versus semaglutide alone (IcoSema/semaglutide 1.99 [1.84; 2.15]) and occurred earlier for IcoSema (12 versus 84 h). Results of in vitro albumin binding studies and animal pharmacokinetic studies supported that the change in semaglutide absorption pharmacokinetics in IcoSema is owing to competition for albumin binding locally at the injection site with icodec outcompeting semaglutide. IcoSema, icodec and semaglutide were well-tolerated, although more gastrointestinal related adverse events occurred with IcoSema versus icodec or semaglutide alone.

Conclusion

The combination of icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema leads to a higher and earlier maximum semaglutide concentration, which will guide the dose recommendations for IcoSema.

Clinical Trial

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03789578.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40261-024-01405-8.

Key Points

| Combining once-weekly insulin icodec and once-weekly semaglutide in IcoSema did not impact icodec pharmacokinetics or semaglutide total exposure but led to a higher and earlier maximum semaglutide concentration. |

| In vitro and animal studies supported that the faster absorption of semaglutide for IcoSema is owing to icodec outcompeting semaglutide for albumin binding locally at the subcutaneous injection site. |

| Knowledge of the change in semaglutide pharmacokinetics in IcoSema can be used to guide the dose recommendations for IcoSema. |

Introduction

While glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are recommended as the first injectable treatment in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), insulin still remains a cornerstone of therapy, starting with basal-only insulin and continuing to intensification with basal-bolus insulin treatment [1, 2]. An alternative and powerful strategy for treatment intensification in T2DM is combination therapy with basal insulin and GLP-1 RA to harness the different mechanisms and target the various tissues of insulin and GLP-1 RA action [3, 4].

Two subcutaneous fixed-ratio combinations of basal insulin and GLP-1 RA are currently available for once-daily administration: insulin degludec/liraglutide (IDegLira) and insulin glargine/lixisenatide (IGlarLixi) [5]. For subcutaneous GLP-1 RAs, once-weekly administration was associated with improved treatment persistence and adherence compared with once-daily dosing [6]. Therefore, it is likely that a once-weekly fixed-ratio combination of basal insulin and GLP-1 RA could help mitigate the inertia often associated with insulin initiation and relieve the treatment burden of daily injections [7–9].

IcoSema is a subcutaneous once-weekly fixed-ratio combination of insulin icodec and semaglutide and is currently in phase 3 development. Icodec is being developed as a once-weekly basal insulin for the treatment of diabetes in adults and is currently approved in several countries worldwide, such as the European Union, Canada, China and Japan [10–12]. In the phase 3 ONWARDS 1 and 3 trials in insulin-naïve individuals with T2DM, icodec demonstrated superior reduction in glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) compared with once-daily basal insulin degludec or glargine U100 with low rates of hypoglycaemia across treatments (< 1 clinically significant or severe episode per patient-year of exposure) [13, 14]. Once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide is a GLP-1 RA for the treatment of T2DM with proven superior and sustained glycaemic control and weight loss versus all comparators evaluated in the SUSTAIN phase 3 clinical trial programme [15, 16]. IcoSema contains 700 U/mL icodec (4200 nmol/mL) and 2 mg/mL semaglutide (486 nmol/mL).

For any fixed-ratio combination of two or more drugs, it is important to characterise the pharmacokinetics of each component relative to their separate administration. Such knowledge is relevant for efficacy and safety and will guide decisions on dosing strategy for the combination product [17]. Here, we report the results of a clinical study investigating the pharmacokinetics of icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema versus separate injections of icodec and semaglutide. In addition, we provide results of in vitro albumin binding studies and animal pharmacokinetic studies to support a mechanistic explanation for the clinical findings.

Methods

Clinical Study Design and Participants

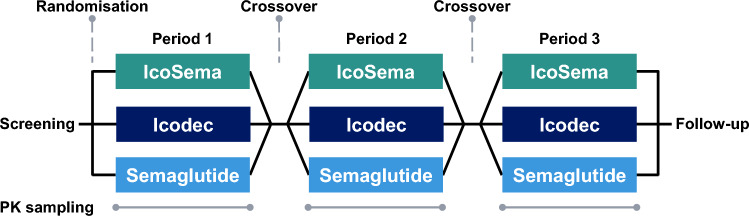

This was a single centre (Profil, Neuss, Germany), randomised, double-blind, three-period crossover study (Fig. 1). The study was approved by an independent ethics committee (Ärztekammer Nordrhein, Düsseldorf, Germany) and by the local health authorities (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Informed consent was provided by all participants prior to any study-related activities. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03789578).

Fig. 1.

Overall study design. Individuals participated in three dose periods, each consisting of single-dose subcutaneous administration of either IcoSema, insulin icodec or semaglutide followed by 5 weeks of pharmacokinetic blood sampling. The dose periods were separated by 1–4 weeks from the end of pharmacokinetic blood sampling until the next single dose (or until follow-up). PK, pharmacokinetic

Eligible participants were men or women aged 18–64 years, diagnosed with T2DM at least 180 days before screening, treated with metformin ± one of the following other oral antidiabetic drugs (OADs): sulphonylurea, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor or sodium-glucose transport protein-2 inhibitor for at least 90 days before screening, and with body weight of 80–120 kg (both inclusive) and HbA1c of 6.0–8.5% (42–69 mmol/mol). Individuals currently or previously treated with insulin on a regular basis, with recurrent severe hypoglycaemia or hypoglycaemia unawareness, blood pressure outside 90–159 mmHg (systolic) or 50–99 mmHg (diastolic), or history of or presence of clinically relevant respiratory, metabolic, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal or endocrinological conditions (except mild complications associated with diabetes), as well as pregnant women, were excluded from participation.

Clinical Study Procedures

The study consisted of a screening visit, an OAD washout period, three treatment periods of 5 weeks each and a follow-up visit (Fig. 1). The OAD washout period of 2 weeks was included for participants entering the study on OAD other than metformin and served to discontinue the participants’ current non-metformin OAD treatment. Metformin treatment continued throughout the study at a stable dose.

At the start of each treatment period, participants received a single dose of either IcoSema containing 175 U icodec (equivalent to 1050 nmol) and 0.5 mg semaglutide (equivalent to 121.5 nmol), icodec alone (175 U) or semaglutide alone (0.5 mg) in randomised sequence. All three study products were provided in 3 mL cartridges to be inserted in a NovoPen 4 pen-injector (Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) and were injected subcutaneously in the thigh by trained site staff at approximately 08:00 h. The IcoSema study product contained 700 U/mL icodec (equivalent to 4200 nmol/mL) and 2 mg/mL semaglutide (equivalent to 486 nmol/mL) (Novo Nordisk). The icodec study product strength was 700 U/mL (equivalent to 4200 nmol/mL) (Novo Nordisk) and the semaglutide study product strength was 1 mg/mL (equivalent to 243 nmol/mL) (Novo Nordisk). Participants stayed in-house at the clinical site until 72 h after each study product administration. The single-dose injections were separated by 6–9 weeks of washout.

Blood samples for pharmacokinetic assessment (2 mL for analysis of icodec and 2 mL for analysis of semaglutide) were drawn pre-dose and frequently up to 840 h (35 days) after administration of each single dose (Table S1). Blood for icodec analysis was drawn in Vacuette Z serum clot activator tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria), allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature, centrifuged within 1 h of collection at 1500g for 10 min at 4 °C, and serum was then transferred into cryotubes and stored at − 20 °C until analysis. Blood for semaglutide analysis was drawn in BD Vacutainer K3EDTA tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), stored on ice for 10 min, centrifuged at 1500g for 10 min at 4 °C and plasma was then transferred into cryotubes and stored at – 20 °C until analysis. Serum icodec concentrations were measured (following IcoSema and icodec administration) using a validated luminescence oxygen channelling immunoassay (LOCI). Plasma semaglutide concentrations were measured (following IcoSema and semaglutide administration) using a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay. For further details on methodology and specifications of the pharmacokinetic assays, refer to Table S2.

Safety assessments included adverse events, hypoglycaemic episodes, vital signs, electrocardiogram, clinical laboratory assessments, physical examination and anti-icodec and anti-semaglutide antibodies. Adverse events and hypoglycaemic episodes were collected continuously throughout the study and were defined as treatment emergent if they occurred from each single dose until 35 days after each single dose. Hypoglycaemic episodes were classified as blood glucose (BG) confirmed [BG < 2.8 mmol/L corresponding to plasma glucose (PG) < 3.1 mmol/L) or severe (severe cognitive impairment requiring assistance for recovery). Vital signs and electrocardiogram were assessed prior to each single dose and 72 h and 35 days after each single dose. Clinical laboratory assessments and physical examination were carried out prior to each single dose and 35 days after each single dose. Blood samples for assessment of anti-icodec and/or anti-semaglutide antibodies were drawn prior to each single dose and 14, 28 and 35 days after each single dose. Anti-icodec and anti-semaglutide antibodies were measured by validated assays. Anti-icodec antibodies were assessed following IcoSema and icodec administration. Samples positive for anti-icodec antibodies were also analysed for cross-reactivity to human insulin. Anti-semaglutide antibodies were assessed following IcoSema administration.

Statistical Analyses of the Clinical Study

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. The sample size calculation was based on within-participant standard deviations for the logarithmic transformed ratios for icodec alone and for semaglutide alone with respect to total exposure from previous studies with icodec and semaglutide (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01730014 and NCT01766245, respectively). These were 0.283 for icodec and 0.255 for semaglutide. With a sample size of 24 participants, the 90% confidence interval (CI) for the estimated geometric mean ratio of total exposure would range from 88 to 113% of the geometric mean ratio for icodec and from 89 to 112% of the geometric mean ratio for semaglutide with at least 90% probability. The widths of these CIs were assumed to be representative of the CIs for the ratios between IcoSema and icodec alone (for icodec) and between IcoSema and semaglutide alone (for semaglutide) with respect to the primary endpoint in the current study (area under the concentration-time curve from zero to last quantifiable observation after a single dose; AUC0–t,SD). Therefore, 24 completers were considered sufficient for comparison of relative bioavailability between the study products. To achieve the required 24 completers, 31 individuals were randomised.

AUC0-t,SD was calculated as the area under the concentration-time curve using the linear trapezoidal technique on the basis of observed values and actual measurement times from time zero until the time of the last quantifiable concentration.

AUC0-t,SD and the maximum concentration after a single dose (Cmax,SD) for both icodec and semaglutide were analysed using linear normal models based on the logarithmic transformed values. The models included treatment, period and participant as fixed effects and an error term. The estimated treatment differences (IcoSema versus icodec alone for icodec endpoints and IcoSema versus semaglutide alone for semaglutide endpoints) were transformed back to the original scale and presented as ratios with 90% CI. AUC0–t,SD and Cmax,SD were evaluated according to guidelines for bioavailability and bioequivalence studies [18, 19]. Thus, IcoSema and separate administration of a component was considered equivalent with respect to a given endpoint if the 90% CI of their estimated mean treatment ratio was fully contained within the range of 80–125%. The time to maximum concentration after a single dose (tmax,SD) as well as all safety parameters were presented by descriptive statistics.

Pharmacokinetic Modelling in the Clinical Study

To extrapolate the pharmacokinetic results from the current single-dose study to the steady-state situation, pharmacokinetic modelling was applied. The steady-state pharmacokinetic profiles of icodec and semaglutide after IcoSema administration and after separate administration of icodec or semaglutide were simulated.

For icodec, the modelling was conducted as previously described [20], except that the model was a one-compartment model with a bioavailability parameter (F, fixed to 1 for separate administration of icodec), an absorption rate parameter (kA), a clearance parameter (CL/F) and a volume of distribution parameter (V/F). Inter-individual variability and inter-occasion variability were included using the approach described by Plum-Mörschel et al. [20]. Body weight was included as a covariate on CL/F and V/F, and treatment (i.e. IcoSema versus separate administration of icodec) was included as a covariate on F and kA.

For semaglutide, the modelling was conducted based on a previously published model [21]. The model was a two-compartment model with a bioavailability parameter (F, fixed to 1 for separate administration of semaglutide), an absorption rate parameter (kA), two clearance parameters (CL/F and Q/F) and two volume of distribution parameters (Vc/F and Vp/F). Inter-individual variability and inter-occasion variability were included using the approach described by Plum-Mörschel et al. [20]; however using a shared random effect for CL/F and Q/F and another shared random effect for Vc/F and Vp/F, assuming a log-normal distribution with correlation between the clearance and volume of distribution parameters. Body weight was included as a covariate on CL/F, Q/F, Vc/F and Vp/F, and treatment (i.e. IcoSema versus separate administration of semaglutide) was included as a covariate on F and kA.

On the basis of the models characterised above, 10 weeks of once-weekly dosing of IcoSema [175 U (1050 nmol) icodec/0.5 mg semaglutide], icodec [175 U (1050 nmol)] or semaglutide (0.5 mg) was simulated for each participant, using the approach previously described [20], and maximum concentration at steady state (Cmax,SS) was derived for icodec and semaglutide as applicable. Cmax,SS for icodec was then compared between IcoSema and icodec alone, while Cmax,SS for semaglutide was compared between IcoSema and semaglutide alone, by statistical analysis as described above for AUC0–t,SD and Cmax,SD.

In Vitro Human Serum Albumin Binding Assays

Competition for albumin binding between icodec and semaglutide was investigated in vitro by measuring the binding of semaglutide to immobilised human serum albumin (HSA) alone or in the presence of icodec. HSA was immobilised to divinyl sulfone-activated sepharose 6B beads (Mini-LeakTM; Kem-En-Tec, Copenhagen, Denmark) as described previously [22, 23]. Semaglutide and icodec were incubated on a HulaMixerTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature with different concentrations of immobilised HSA in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) and a final concentration of 0.005% Tween 20. Incubation without immobilised HSA was used as reference. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 750 g to remove the beads. The resulting supernatants were assayed for semaglutide using a LOCI assay. The unbound fraction of semaglutide was calculated as the semaglutide concentration in the supernatant when incubated with immobilised HSA divided by the same for the reference.

The binding affinity of icodec and semaglutide to HSA was investigated by measuring the displacement of icodec and semaglutide from HSA in vitro at increasing concentrations of a soluble fatty acid derivative (SFAD) consisting of a 20-carbon long fatty acid with a 4× γ-Glu extension, similar to the side chains on icodec and semaglutide. The HSA binding experiments were performed essentially as described previously [15]: Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed in an XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (BeckmanCoulter, Indianapolis, USA) at 20 °C. Solutions of 100 μM ligand, 10 μM HSA and 0–1000 μM SFAD were filled into double-sector, sapphire-capped Epon centrepieces of 12 mm path length. The displacement curves for icodec and semaglutide were described by simple sigmoidal fits, from which the half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were determined. The lower the IC50, the less affinity of the ligand to HSA.

Pharmacokinetic Studies in Pigs

The pharmacokinetics of semaglutide were investigated in female Landrace-Yorkshire-Duroc (LYD) pigs following IcoSema administration or separate injections of icodec and semaglutide. Animals were dosed subcutaneously with either IcoSema (4200 nmol/mL icodec and 490 nmol/mL semaglutide) at a single dose containing 7.5 nmol/kg icodec and 0.875 nmol/kg semaglutide (N = 8) or separate similar injections of icodec and semaglutide (N = 8). Blood was sampled from the jugular vein prior to dosing and frequently until 336 h post-dose. Plasma semaglutide concentrations were measured using a LOCI assay with an analytical range from 1 to 180 nmol/L. In the group of animals receiving separate injections of icodec and semaglutide, one animal was excluded from the semaglutide pharmacokinetic results due to being an outlier with only 10–20% of semaglutide concentrations relative to the rest of the group.

The pharmacokinetics of semaglutide were also investigated in female LYD pigs following IcoSema administration with either porcine serum albumin (PSA) or SFAD added to the IcoSema formulation. Animals were dosed subcutaneously with IcoSema (2100 nmol/mL icodec and 490 nmol/mL semaglutide) at a single dose containing 3.75 nmol/kg icodec and 0.875 nmol/kg semaglutide with addition of either 0.2 mmol/L PSA (N = 8) or 2.1 mmol/L SFAD (N = 8) to the formulation. Blood was sampled from the jugular vein prior to dosing and frequently until 336 h post-dose. Plasma semaglutide concentrations were measured using a LOCI assay with an analytical range from 0.5 to 200 nmol/L.

Results

Participants in the Clinical Study

A total of 42 individuals were screened and 31 were randomised and exposed to at least one of the three study products (Fig. S1). One participant was withdrawn owing to a non-serious adverse event of drug hypersensitivity after IcoSema administration, two participants withdrew consent during the study, and one participant was withdrawn upon decision by the sponsor. In total, 27 participants completed the study. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 31)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.4 ± 6.2 |

| Sex | |

| Female, N (%) | 8 (25.8) |

| Male, N (%) | 23 (74.2) |

| Race | |

| White, N (%) | 31 (100.0) |

| Height, m | 1.76 ± 0.08 |

| Body weight, kg | 96.2 ± 10.6 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.1 ± 3.4 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus duration, years | 9.5 ± 6.9 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 55 ± 6 |

| % | 7.2 ± 0.6 |

| Anti-diabetic medication at screening | |

| Metformin, N (%) | 31 (100.0) |

| DPP-4 inhibitors, N (%) | 5 (16.1) |

| SGLT2 inhibitors, N (%) | 2 (6.5) |

Data are mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated

BMI, body mass index; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; N, number of individuals; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2

Pharmacokinetics in the Clinical Study

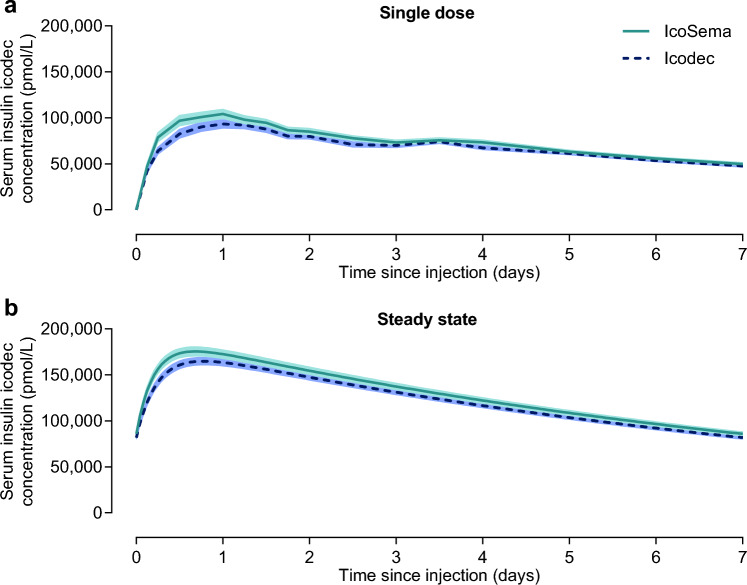

Icodec pharmacokinetic profiles covering a 1-week dosing interval after a single dose and simulated at steady state are presented in Fig. 2 for IcoSema administration and for icodec administration alone. As shown in Table 2, the 90% CI for the ratio of IcoSema/icodec was fully contained within the range of 80–125% for total icodec exposure after single dose (AUC0–t,SD,Icodec), suggesting similar relative bioavailability of icodec following IcoSema administration and icodec administration alone. The same was observed for maximum concentration after single dose (Cmax,SD,Icodec) and at steady state (Cmax,SS,Icodec). The median time to maximum icodec concentration after single dose (tmax,SD,Icodec) was 24 h following both IcoSema administration and icodec administration alone. Thus, icodec pharmacokinetics are not affected by combining icodec with semaglutide in IcoSema.

Fig. 2.

Mean serum insulin icodec concentration-time profiles during a dosing interval of 1 week following subcutaneous injection of IcoSema (175 U [1050 nmol] insulin icodec/0.5 mg [121.5 nmol] semaglutide) or insulin icodec alone (175 U [1050 nmol]). a After a single dose. b Simulation of once-weekly administration at steady state. N = 30 for IcoSema and N = 28 for insulin icodec. Error bands show standard error of the mean

Table 2.

Total exposure and maximum concentration after subcutaneous administration of either IcoSema, insulin icodec or semaglutide

| Parameter | N | LS mean | Treatment ratio [90% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin icodec pharmacokinetics | |||

| Total exposure after single dose (AUC0–t,SD,Icodec) (nmol·h/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 21532 | |

| Icodec | 28 | 20319 | |

| IcoSema/Icodec | 1.06 [1.01; 1.12] | ||

| Maximum concentration after single dose (Cmax,SD,Icodec) (nmol/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 106 | |

| Icodec | 28 | 95 | |

| IcoSema/Icodec | 1.12 [1.06; 1.18] | ||

| Model-predicted maximum concentration at steady state (Cmax,SS,Icodec) (nmol/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 176 | |

| Icodec | 28 | 164 | |

| IcoSema/Icodec | 1.07 [1.02; 1.13] | ||

| Semaglutide pharmacokinetics | |||

| Total exposure after single dose (AUC0–t,SD,Semaglutide) (nmol·h/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 2692 | |

| Semaglutide | 28 | 2418 | |

| IcoSema/Semaglutide | 1.11 [1.05; 1.17] | ||

| Maximum concentration after single dose (Cmax,SD,Semaglutide) (nmol/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 16 | |

| Semaglutide | 28 | 8 | |

| IcoSema/Semaglutide | 1.99 [1.84; 2.15] | ||

| Model-predicted maximum concentration at steady state (Cmax,SS,Semaglutide) (nmol/L) | |||

| IcoSema | 30 | 25 | |

| Semaglutide | 28 | 16 | |

| IcoSema/Semaglutide | 1.53 [1.44; 1.61] | ||

Results for AUC0–t,SD reflect total exposure also at steady state since extrapolation from single dose to steady state does not impact total exposure

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; Cmax, maximum concentration; LS Mean, least square mean; N, number of individuals; SD, single dose; SS, steady state

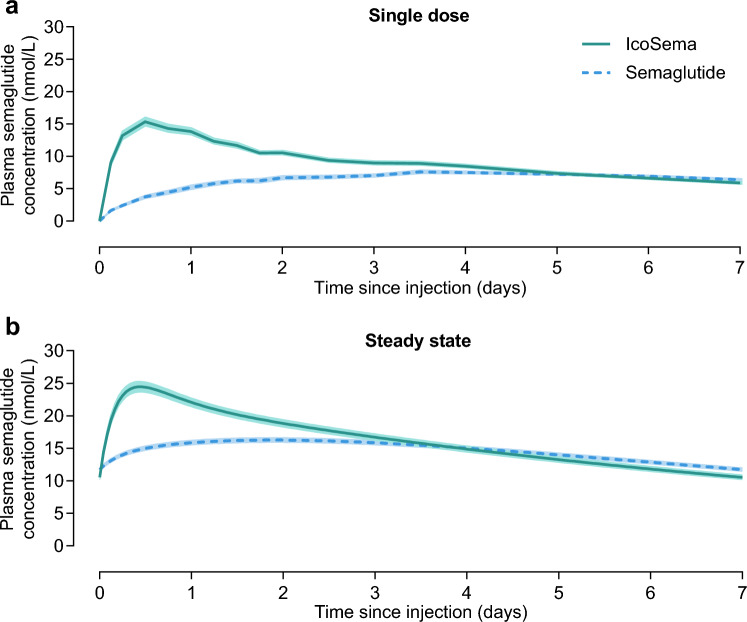

Semaglutide pharmacokinetic profiles covering a 1-week dosing interval after a single dose and simulated at steady state are presented in Fig. 3 for IcoSema administration and for semaglutide administration alone. As presented in Table 2, the 90% CI for the ratio of IcoSema/semaglutide was fully contained within the range of 80%–125% for total exposure after single dose (AUC0–t,SD,Semaglutide), suggesting similar relative bioavailability of semaglutide following IcoSema administration and semaglutide administration alone. However, for both maximum concentration after single dose (Cmax,SD,Semaglutide) and at steady state (Cmax,SS,Semaglutide), the 90% CI for the ratio of IcoSema/semaglutide was above the range of 80% to 125% (Table 2). Furthermore, the median time to maximum semaglutide concentration after single dose (tmax,SD,Semaglutide) was 12 h following IcoSema administration and 84 h following semaglutide administration alone. Altogether, these results show that the pharmacokinetic profile of semaglutide is changed when combining semaglutide with icodec in IcoSema, i.e. maximum concentration is increased and occurs earlier while total exposure remains unchanged.

Fig. 3.

Mean plasma semaglutide concentration-time profiles during a dosing interval of 1 week following subcutaneous injection of IcoSema (175 U [1050 nmol] insulin icodec/0.5 mg [121.5 nmol] semaglutide) or semaglutide alone (0.5 mg [121.5 nmol]). a After a single dose. b Simulation of once-weekly administration at steady state. N = 30 for IcoSema and N = 28 for semaglutide. Error bands show standard error of the mean

Proposed Mechanism for the Difference in the Semaglutide Pharmacokinetic Profile Observed Between IcoSema and Semaglutide Administration

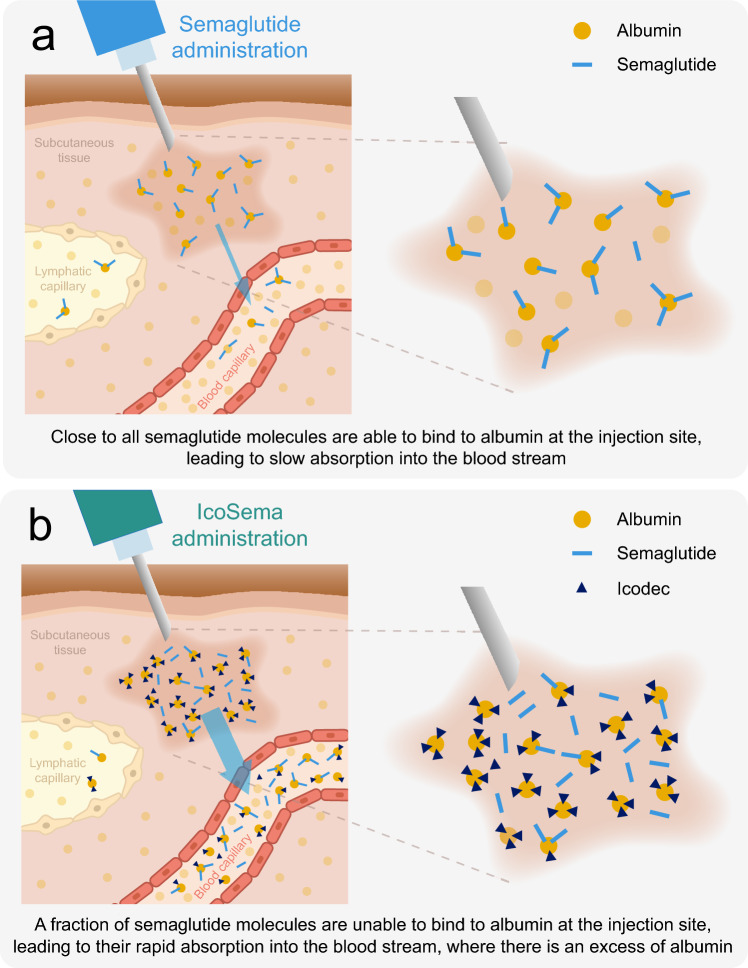

The change in the semaglutide pharmacokinetic profile when semaglutide is combined with icodec in IcoSema gave rise to the hypothesis that there could be an interaction between icodec and semaglutide locally at the injection site in the subcutaneous tissue, since both molecules bind to albumin. It was proposed that since icodec has a longer fatty diacid side chain compared to semaglutide (20-carbon versus 18-carbon long fatty diacid, respectively), icodec would have a relatively higher affinity for albumin and thus could outcompete semaglutide for the fatty acid binding sites on albumin. This would then be expected to result in a larger fraction of free, unbound semaglutide and consequently a faster absorption of semaglutide into the circulation (Fig. 4). This hypothesis was investigated in a series of in vitro albumin binding studies and animal pharmacokinetic studies.

Fig. 4.

Proposed mechanism to explain the increased absorption rate of semaglutide when co-formulated with insulin icodec in IcoSema. a Injection of semaglutide alone. The majority of semaglutide binds to albumin at the injection site resulting in protracted absorption into the circulation (albumin-bound semaglutide is absorbed slowly via the lymph). b Injection of IcoSema. Insulin icodec outcompetes semaglutide for albumin binding at the injection site resulting in a larger fraction of free, unbound semaglutide and consequently a faster absorption into the circulation (and a smaller fraction absorbed slowly via the lymph). Note that absorption of semaglutide and insulin icodec from the injection site into the circulation occurs as free, unbound molecules, after which the vast majority is bound to the excess albumin in the circulation

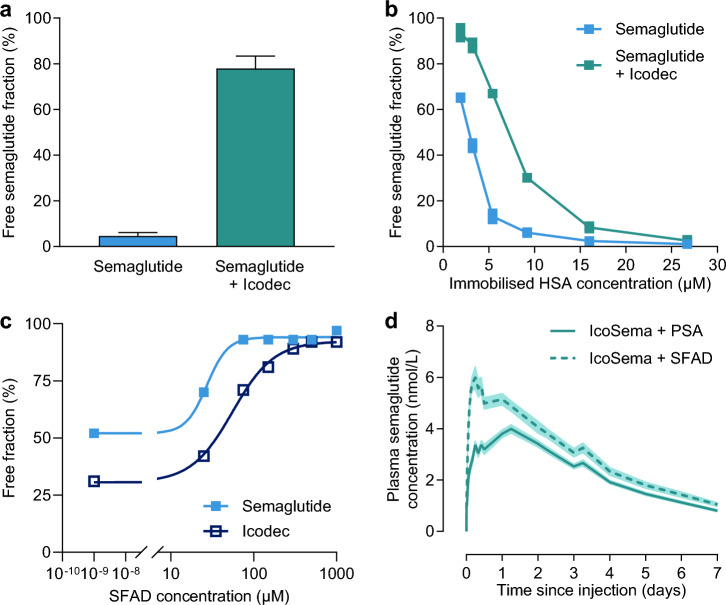

In an in vitro competition HSA-binding assay, semaglutide at a final concentration of 14.8 µM was incubated with immobilised HSA (26 µM) with and without icodec (147 µM). The unbound fraction of semaglutide without icodec was 4.6%, while the presence of icodec increased the unbound fraction of semaglutide to 78% (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

In vitro and animal studies to investigate the hypothesis of competition between insulin icodec and semaglutide for albumin binding at the subcutaneous injection site. a Displacement of semaglutide (14.8 µM) from immobilised HSA (26 µM) in vitro by addition of insulin icodec (147 µM). Data are mean and standard deviation (N = 4 per group). b Displacement of semaglutide (2.5 µM) from immobilised HSA at varying concentrations by addition of insulin icodec (25 µM). Data are mean and replicates (N = 2). c Displacement of semaglutide and insulin icodec from HSA in vitro by increasing concentration of SFAD (N = 1). d Mean plasma semaglutide concentration-time profiles in LYD pigs following subcutaneous injection of IcoSema with PSA or SFAD in the co-formulation. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (N = 8 per group). HSA, human serum albumin; PSA, porcine serum albumin; SFAD, soluble fatty acid derivative

This difference indicates that the addition of icodec displaces or prevents the binding of semaglutide to albumin. Next, the unbound fraction of semaglutide was measured in the presence of varying concentrations of immobilised HSA (from 1.9 to 26.7 µM) either without icodec or with a ten-fold molar excess of icodec relative to semaglutide (i.e. 2.5 µM semaglutide with or without 25 µM icodec). The ability of semaglutide to bind to albumin can be observed by the concentration dependent decrease in the unbound fraction as albumin concentrations increase (Fig. 5b). With the addition of icodec, the curve shifts to the right, indicating that there is competitive binding for albumin between semaglutide and icodec leading to more free semaglutide in the presence of icodec at all HSA concentrations owing to the relatively stronger albumin binding properties of icodec. In another in vitro HSA-binding assay, the effect of increasing concentrations of a soluble fatty acid derivative (SFAD) consisting of a 20-carbon long fatty acid with a 4 × γ-Glu extension was investigated to test the hypothesis that there could be competitive binding for albumin via the fatty diacid containing side chains on icodec and semaglutide (Fig. 5c). The albumin-binding moiety of SFAD resembles those of semaglutide and icodec, except that the fatty acid of semaglutide is 18-carbon long, while the fatty acid of icodec is 20-carbon long. Therefore, SFAD was expected to displace both semaglutide and icodec from their albumin-binding pockets. As can be seen in Fig. 5c, at all SFAD concentrations, the free fraction for semaglutide is greater than for icodec as illustrated by the dose-response curve for semaglutide being to the left of that for icodec. The IC50 was 27 µM for semaglutide and 55 µM for icodec, indicating that semaglutide is more readily displaced from albumin by SFAD, further suggesting that the HSA affinity in vitro is stronger for icodec than for semaglutide.

Finally, to test the proposed mechanism in vivo, a pharmacokinetic study in LYD pigs was conducted to investigate whether semaglutide pharmacokinetics can be affected by the addition of either albumin or SFAD to the IcoSema formulation. Adding porcine albumin to the formulation was expected to increase the albumin pool locally at the injection site. Adding SFAD was expected to add another layer of competition for albumin binding. The LYD pig was qualified as a suitable pharmacokinetic model in that it demonstrated the same difference in the semaglutide pharmacokinetic profile in IcoSema as seen in the clinical study, although the absolute values of the pharmacokinetic parameters differed owing to the species (Fig. S2). Consistent with the hypothesis of competition for albumin binding at the injection site, addition of SFAD to the IcoSema formulation exaggerated the peak in the semaglutide pharmacokinetic profile compared with that obtained when porcine albumin was added to the IcoSema formulation (Fig. 5d).

Safety in the Clinical Study

An overview of treatment emergent adverse events is presented in Table 3. A higher frequency of adverse events was observed following IcoSema administration versus administration of icodec or semaglutide alone. This was mainly driven by gastrointestinal related adverse events. Most adverse events were mild for all three treatments, and all events except one had an outcome of recovered/resolved. One serious adverse event was reported: a severe event of appendicitis with onset 27 days after icodec administration, assessed by the investigator to be possibly related to study product and with an outcome of recovered/resolved on the same day after surgical intervention. One adverse event led to withdrawal from the study: a non-serious drug hypersensitivity event of moderate severity with onset 12 days after IcoSema administration, duration of 5 days, assessed by the investigator to be possibly related to study product and with an outcome of recovered/resolved.

Table 3.

Overview of treatment emergent adverse events

| AE | IcoSema | Insulin icodec | Semaglutide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | E | N | (%) | E | N | (%) | E | |

| Treatment emergent AEs | 27 | (90.0) | 100 | 15 | (53.6) | 30 | 17 | (60.7) | 53 |

| Serious AEs | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 1 | (3.6) | 1 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 |

| Severity | |||||||||

| Severe | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 1 | (3.6) | 1 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 |

| Moderate | 14 | (46.7) | 21 | 5 | (17.9) | 6 | 5 | (17.9) | 7 |

| Mild | 27 | (90.0) | 79 | 12 | (42.9) | 23 | 16 | (57.1) | 46 |

| Relationship to study product | |||||||||

| Probable | 22 | (73.3) | 56 | 3 | (10.7) | 4 | 12 | (42.9) | 29 |

| Possible | 19 | (63.3) | 37 | 8 | (28.6) | 14 | 8 | (28.6) | 15 |

| Unlikely | 5 | (16.7) | 7 | 9 | (32.1) | 12 | 6 | (21.4) | 9 |

| Outcome | |||||||||

| Recovering/resolving | 1 | (3.3) | 1 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 |

| Recovered/resolved | 27 | (90.0) | 99 | 15 | (53.6) | 30 | 17 | (60.7) | 53 |

| Most frequently reported SOCs and PTsa | |||||||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 22 | (73.3) | 51 | 4 | (14.3) | 5 | 12 | (42.9) | 26 |

| Nausea | 14 | (46.7) | 17 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 6 | (21.4) | 6 |

| Vomiting | 11 | (36.7) | 12 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | 2 | (7.1) | 3 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 12 | (40.0) | 12 | 3 | (10.7) | 3 | 6 | (21.4) | 6 |

| Decreased appetite | 12 | (40.0) | 12 | 3 | (10.7) | 3 | 5 | (17.9) | 5 |

| Nervous system disorders | 9 | (30.0) | 10 | 4 | (14.3) | 5 | 5 | (17.9) | 7 |

| Headache | 6 | (20.0) | 7 | 4 | (14.3) | 5 | 2 | (7.1) | 4 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 6 | (20.0) | 6 | 2 | (7.1) | 2 | 4 | (14.3) | 4 |

Treatment emergent: occurring from dosing until 35 days after dosing

AE: adverse event, any untoward medical occurrence in a study participant that is temporally associated with the use of a study product, whether or not considered related to the study product. Can be any unfavourable and unintended sign, including an abnormal laboratory finding, symptom or disease (new or exacerbated)

Serious AE: an AE that results in death, is life-threatening, requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent disability/incapacity, is a congenital anomaly/birth defect or is an important medical event

Severity: severe (prevents normal everyday activities), moderate (causes sufficient discomfort and interferes with normal everyday activities) and mild (easily tolerated, causing minimal discomfort and not interfering with everyday activities)

Relationship to study product: probable (good reason and sufficient documentation to assume a causal relationship), possible (a causal relationship is conceivable and cannot be dismissed) and unlikely (most likely related to aetiology other than the study product)

aReported by ≥ 15% of participants after at least one treatment

AE, adverse event; E, number of events; N, number of individuals; %, percent of individuals; PT, preferred term; SOC, system organ class

Few treatment-emergent BG confirmed hypoglycaemic episodes were reported (BG < 2.8 mmol/L; PG < 3.1 mmol/L): four, three and one episodes for IcoSema, icodec and semaglutide, respectively. None of these were symptomatic. There were no severe hypoglycaemic episodes in the study.

A total of 13 participants (42%) were positive for anti-icodec antibodies at least once during the study. Overall, 12 of these participants were also positive for anti-icodec antibodies cross-reacting to human insulin at least once during the study. No participants were positive for anti-semaglutide antibodies.

No clinically significant findings were reported for clinical laboratory assessments, vital signs, physical examination or electrocardiogram.

Discussion

The main findings of the present studies are the following: (1) the pharmacokinetics of icodec are unchanged when combining icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema, (2) the total exposure of semaglutide in IcoSema is unchanged, but the maximum concentration is higher and earlier compared with semaglutide administration alone, (3) the change in semaglutide pharmacokinetics in IcoSema appears to be owing to competition for albumin binding locally at the injection site, where icodec outcompetes semaglutide and (4) the frequency of gastrointestinal related adverse events is higher for IcoSema versus icodec or semaglutide administration alone.

The higher and earlier maximum concentration of semaglutide in IcoSema compared with semaglutide administration alone will have clinical implications related to the semaglutide doses recommended to be administered for IcoSema. To mitigate the risk of gastrointestinal disorders during the first months of treatment, the initial dose of semaglutide alone is 0.25 mg and may be increased every 4 weeks to 0.5, 1 and finally 2 mg, which is the maximum recommended dose [24]. In the current clinical study, a higher frequency of gastrointestinal disorders was observed with IcoSema versus semaglutide alone, most likely owing to the altered pharmacokinetic profile of semaglutide in IcoSema. Consequently, a more conservative stepwise dose escalation would be required when initiating IcoSema treatment compared with semaglutide treatment alone. Furthermore, the maximum recommended dose of semaglutide when using IcoSema may need to be reduced relative to semaglutide administered alone. It is, however, reassuring that the degree to which the maximum concentration of semaglutide in IcoSema increases was shown by pharmacokinetic modelling to be lessened at steady state relative to the increase seen after a single dose (Fig. 3).

On the basis of this pharmacokinetic difference, in the ongoing phase 3 clinical trial programme for IcoSema, an initial dose of IcoSema corresponding to 0.114 mg semaglutide has been selected, hence lower than the 0.25 mg recommended as starting dose for semaglutide alone [25–27]. Furthermore, the titration steps for IcoSema correspond to ± 0.029 mg semaglutide with a maximum dose corresponding to 1 mg semaglutide. Thus, the selected starting dose and titration algorithm in the IcoSema phase 3 programme account for the higher maximum concentration of semaglutide in IcoSema and are expected to provide an acceptable gastrointestinal adverse event profile.

Overall, IcoSema, icodec and semaglutide were well-tolerated in this study. The only clinically relevant difference between treatments was the higher frequency of gastrointestinal related adverse events with IcoSema versus icodec or semaglutide alone, which can be mitigated by appropriate dosing recommendations for IcoSema, as discussed above. Furthermore, almost half of the participants were positive for anti-icodec antibodies during the study with the vast majority of these participants also being positive for anti-icodec antibodies cross-reacting to human insulin. The clinical relevance of this finding may, however, be limited. In the phase 3 trials with once-weekly icodec in T2DM, glycaemic control was achieved with low risk of hypoglycaemia and the general safety profile was broadly similar to once-daily degludec or once-daily glargine U100, including low incidence of hypersensitivity events in all treatment arms [13, 14, 28, 29].

All results of the in vitro albumin binding studies and animal pharmacokinetic studies described here are consistent with and support the hypothesis of competition between icodec and semaglutide for albumin binding occurring locally at the injection site in the subcutaneous tissue such that icodec outcompetes semaglutide (Fig. 4). The main reason for this competition is that icodec has a greater affinity for HSA than semaglutide does, primarily owing to the characteristics of the longer fatty diacid side chain (20-carbon) in icodec [10] compared with the side chain in semaglutide (18-carbon) [15]. Moreover, the difference is enhanced by the molar ratio of icodec versus semaglutide in the IcoSema co-formulation, where icodec is present in an approximately nine times higher molar concentration than semaglutide (4200 nmol/mL versus 486 nmol/mL).

Most importantly, the limited amount of albumin leading to competition between icodec and semaglutide for albumin binding sites is only a local phenomenon occurring at the injection area. As soon as icodec and semaglutide are absorbed into the circulation, there is a large excess of albumin relative to the icodec and semaglutide concentrations and competition for albumin binding sites does not occur. As a result, patients with conditions leading to low albumin levels are not at risk of additional changes to the semaglutide pharmacokinetics in IcoSema.

One of the strengths of the current study was that the pharmacokinetics of icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema were compared with the pharmacokinetics of the single components when these were administered on separate occasions, in contrast to separate simultaneous injections of icodec and semaglutide. In this manner, any potential interactions between icodec and semaglutide for the single-component pharmacokinetic profiles were eliminated. Another strength is that the in vitro albumin binding studies were conducted at a molar ratio of approximately 10:1 for icodec versus semaglutide, closely resembling the icodec/semaglutide molar ratio in the IcoSema formulation, allowing for comparisons with the clinical situation. It was a limitation of the current study that only single-dose pharmacokinetics were directly measured. As it would have taken three to four half-lives (i.e. 3–4 weeks) to achieve steady state for both icodec and semaglutide, it was not considered feasible for the participants to conduct a three-way crossover study at steady state. The steady-state pharmacokinetics were instead assessed following extrapolation of the single-dose pharmacokinetic profiles using pharmacokinetic modelling.

Conclusions

While icodec pharmacokinetics and semaglutide total exposure were unaffected by the combination of icodec and semaglutide in IcoSema, the maximum concentration of semaglutide was higher and occurred earlier presumably owing to icodec outcompeting semaglutide for albumin binding locally at the injection site. It is important to be aware of this change in semaglutide pharmacokinetics in IcoSema to ensure appropriate dose recommendations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lotte Majbrith Badeby, Henning Gustafsson, Berit Bugge Nielsen, Lisette Gammelgaard Nielsen, Betina Ørtberg Olsen, Lene Von Voss and Pia Von Voss for expert technical assistance. Medical writing support was provided by Carsten Roepstorff, PhD, CR Pharma Consult, Copenhagen, Denmark, funded by Novo Nordisk.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Conflicts of interest

L.W., L.A., S.T.B., T.K., N.R.K., E.N., L.N., T.M.P.R., D.B.S. and A.V. are employees and shareholders of Novo Nordisk. H.V.C. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. L.P.-M. is an employee and shareholder of Profil. Profil received research funds from Adocia, AstraZeneca, Betagenon, Biocon, Bioton, Crinetics, Eli Lilly, Genova, Nanexa, NeoDyne, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Spiden and Zealand Pharma. L.P.-M. received speaker honoraria from Eli Lilly, Gan and Lee Pharmaceuticals and Novo Nordisk.

Availability of data and material

Individual participant data will be shared in data sets in a de-identified/anonymised format. Datasets from Novo Nordisk sponsored clinical research completed after 2001 for product indications approved in both the EU and USA will be shared. Study protocol and redacted clinical study report will be available according to Novo Nordisk data sharing commitments. The data will be available permanently after research completion and approval of product and product use in both EU and USA. There is no end date. Data will be shared with bona fide researchers submitting a research proposal requesting access to data for use as approved by the independent review board according to the independent review board charter (see novonordisk-trials.com). The data will be made available on a specialised SAS data platform. Individual data from animal studies and in vitro studies will be shared upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The clinical study was approved by an independent ethics committee (Ärztekammer Nordrhein, Düsseldorf, Germany; approval ID 2018242; approval date 12 November 2018). Animal studies were performed according to the Danish Act on Experiments on Animals, the Appendix A of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS 123), and European Union Directive 2010/63. The animal studies were performed under licenses granted by the Danish national Animal Experiments Inspectorate (no. 2010/561-1786 and no. 2015-15-0201-00540).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the clinical study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

L.W., N.R.K., L.N. and T.M.P.R. contributed to clinical study data analysis, critical manuscript revision and final manuscript approval; L.A., S.T.B., T.K., E.N., D.B.S. and A.V. contributed to animal and in vitro study design, data analysis, critical manuscript revision and final manuscript approval; H.V.C. and L.P.-M. contributed to clinical study data collection, critical manuscript revision and final manuscript approval.

References

- 1.Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65:1925–66. 10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024;47(Suppl 1):S158–78. 10.2337/dc24-S009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Cariou B. Pleiotropic effects of insulin and GLP-1 receptor agonists: Potential benefits of the association. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41(Suppl 1):S28–35. 10.1016/S1262-3636(16)30006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balena R, Hensley IE, Miller S, Barnett AH. Combination therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonists and basal insulin: a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:485–502. 10.1111/dom.12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perreault L, Rodbard H, Valentine V, Johnson E. Optimizing fixed-ratio combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. Adv Ther. 2019;36:265–77. 10.1007/s12325-018-0868-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polonsky WH, Arora R, Faurby M, Fernandes J, Liebl A. Higher rates of persistence and adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating once-weekly vs daily injectable glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in US clinical practice (STAY Study). Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:175–87. 10.1007/s13300-021-01189-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polonsky WH, Henry RR. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adher. 2016;10:1299–307. 10.2147/PPA.S106821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okemah J, Peng J, Quiñones M. Addressing clinical inertia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1735–45. 10.1007/s12325-018-0819-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Bruhn D, Best JH. Patient perspectives on once-weekly medications for diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:144–9. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjeldsen TB, Hubálek F, Hjørringgaard CU, et al. Molecular engineering of insulin icodec, the first acylated insulin analog for once-weekly administration in humans. J Med Chem. 2021;64:8942–50. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura E, Pridal L, Glendorf T, et al. Molecular and pharmacological characterization of insulin icodec: a new basal insulin analog designed for once-weekly dosing. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9:e002301. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philis-Tsimikas A, Bajaj HS, Begtrup K, et al. Rationale and design of the phase 3a development programme (ONWARDS 1–6 trials) investigating once-weekly insulin icodec in diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25:331–41. 10.1111/dom.14871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstock J, Bain SC, Gowda A, et al. Weekly icodec versus daily glargine U100 in type 2 diabetes without previous insulin. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:297–308. 10.1056/NEJMoa2303208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingvay I, Asong M, Desouza C, et al. Once-weekly insulin icodec vs once-daily insulin degludec in adults with insulin-naive type 2 diabetes: the ONWARDS 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:228–37. 10.1001/jama.2023.11313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau J, Bloch P, Schäffer L, et al. Discovery of the once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogue semaglutide. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7370–80. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aroda VR, Ahmann A, Cariou B, et al. Comparative efficacy, safety, and cardiovascular outcomes with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: insights from the SUSTAIN 1–7 trials. Diabetes Metab. 2019;45:409–18. 10.1016/j.diabet.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dash RP, Rais R, Srinivas NR. Key pharmacokinetic essentials of fixed-dosed combination products: case studies and perspectives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57:419–26. 10.1007/s40262-017-0589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Guideline on the investigation of bioequivalence. CPMP/EWP/QWP/1401/98 Rev. 1/Corr. 20 January 2010. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-investigation-bioequivalence-rev1_en.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 19.Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry. Bioavailability and bioequivalence studies submitted in NDAs or INDs—general considerations. 2014. https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Bioavailability-and-Bioequivalence-Studies-Submitted-in-NDAs-or-INDs-%E2%80%94-General-Considerations.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 20.Plum-Mörschel L, Andersen LR, Hansen S, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of insulin icodec after subcutaneous administration in the thigh, abdomen or upper arm in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Drug Investig. 2023;43:119–27. 10.1007/s40261-022-01243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overgaard RV, Delff PH, Petri KCC, Anderson TW, Flint A, Ingwersen SH. Population pharmacokinetics of semaglutide for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:649–62. 10.1007/s13300-019-0581-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtzhals P, Havelund S, Jonassen I, et al. Albumin binding of insulins acylated with fatty acids: characterization of the ligand-protein interaction and correlation between binding affinity and timing of the insulin effect in vivo. Biochem J. 1995;312:725–31. 10.1042/bj3120725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurtzhals P, Havelund S, Jonassen I, Kiehr B, Ribel U, Markussen J. Albumin binding and time action of acylated insulins in various species. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:304–8. 10.1021/js950412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozempic (semaglutide). European Medicines Agency. Summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ozempic-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 25.ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05352815. A 52 week study comparing the efficacy and safety of once weekly IcoSema and once weekly insulin icodec, both treatment arms with or without oral anti diabetic drugs, in participants with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with daily basal insulin (COMBINE 1). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05352815. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 26.ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05259033. A 52 week study comparing the efficacy and safety of once weekly IcoSema and once weekly semaglutide, both treatment arms with or without oral anti diabetic drugs, in participants with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with a GLP 1 receptor agonist (COMBINE 2). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05259033. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 27.ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05013229. A 52 week study comparing the efficacy and safety of once weekly IcoSema and daily insulin glargine 100 units/mL combined with insulin aspart, both treatment arms with or without oral anti diabetic drugs, in participants with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with daily basal insulin (COMBINE 3). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05013229. Accessed 27 Sept 2024.

- 28.Philis-Tsimikas A, Asong M, Franek E, et al. Switching to once-weekly insulin icodec versus once-daily insulin degludec in individuals with basal insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (ONWARDS 2): a phase 3a, randomised, open label, multicentre, treat-to-target trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:414–25. 10.1016/S2213-8587(23)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathieu C, Ásbjörnsdóttir B, Bajaj HS, et al. Switching to once-weekly insulin icodec versus once-daily insulin glargine U100 in individuals with basal-bolus insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (ONWARDS 4): a phase 3a, randomised, open-label, multicentre, treat-to-target, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1929–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.