Abstract

Background

Endovascular embolization is an adjunct to meningioma resection. Isolating the effectiveness of embolization is difficult as MR imaging is typically performed before embolization and after resection, and volumetric assessment of embolization on 2D angiographic imaging is challenging. We investigated the correlation between 2D angiographic and 3D MR measurements of meningioma devascularization following embolization.

Methods

We implemented a protocol for postembolization, preresection MRI. Angiographic devascularization was graded according to reduction of tumor blush from 1 (partial embolization) to 4 (complete embolization with no residual circulation supply). Volumetric extent of embolization was quantified as the percent of tumor contrast enhancement lost following embolization. Tumor embolization was analyzed according to tumor location and vascular supply.

Results

Thirty consecutive patients met inclusionary criteria. Grade 1 devascularization was achieved in 7% of patients, grade 2 in 43%, grade 3 in 20%, and grade 4 in 30%. Average extent of embolization was 37 ± 6%. Extent of tumor embolization was low (<25%) in 40%, moderate (25%–75%) in 40%, and high (>75%) in 20% of patients. Convexity, parasagittal/falcine and sphenoid wing tumors were found to have distinct vascular supply patterns and extent of embolization. Angiographic devascularization grade was significantly correlated with volumetric extent of tumor embolization (p < 0.001, r = 0.758).

Conclusion

This is the first study to implement postembolization, preoperative MRI to assess extent of embolization prior to meningioma resection. The study demonstrates that volumetric assessment of contrast reduction following embolization provides a quantitative and spatially resolved framework for assessing extent of tumor embolization.

Keywords: Tumor embolization, meningioma, volumetric analysis, image segmentation

Introduction

Surgical resection remains the standard treatment for large or symptomatic meningiomas, with radiosurgery used as an alternative for small, recurrent, or residual tumors.1–3 Preoperative embolization, using catheter-directed delivery of embolic agents, has been used as an adjunct to surgical tumor resection for decades.4,5 The rationale for preoperative embolization has traditionally focused on minimizing surgical blood loss in the setting of large or highly vascular tumors.6–10 Several systematic reviews have attempted to assess the efficacy of preoperative tumor embolization from the standpoint of intraoperative blood loss, with inconclusive results.6–9 There are several challenges to using this parameter as the sole measure of embolization efficacy. Firstly, intraoperative blood loss is notoriously difficult to quantify and, using this parameter as the sole measure of embolization efficacy has several drawbacks. Total intraoperative blood loss, even if accurately measured, is not always a reflection of tumor-related bleeding, as a significant proportion of total blood loss (and variability in blood loss) is often associated with the exposure. Second, and importantly, many surgeons have noted changes in the character of embolized tumors beyond the degree of vascularity. In particular, extensively embolized tumors have been observed to necrose and soften in ways that facilitate resection, and these changes have not typically been captured in systematic reviews.3,11–14

Standard clinical imaging paradigms typically involve obtaining diagnostic MRI in each patient before and after tumor resection.12,15 In most practices, tumor embolization occurs in the days preceding resection, and it has until now been rare for patients to undergo additional volumetric imaging after embolization and prior to surgical resection. As a result, the postoperative MRI most often represents the combined effects of tumor embolization and surgical resection, making it impossible to decouple the effects of tumor embolizations from those of tumor resection. 3

Previous studies have investigated the direct physiological effects of tumor embolization on meningiomas and other intracranial tumors supplied by the external carotid artery. However, none have used direct image analysis from volumetric data.14,16 Direct effects of intratumoral and branch occlusion on tumor physiology and patient outcomes have been investigated; however, many of these studies either rely on imprecise approximations of tumor volume or only record preoperative imaging data.17–19

As a step toward a more detailed understanding of the effects of embolization on tumor behavior and the impact of embolization on the surgical management of meningiomas, we developed an imaging protocol and quantitative assessment methods for overcoming these limitations. We introduced a uniform protocol for patients undergoing preoperative tumor embolization to obtain an additional brain MRI scan following embolization, prior to surgery. This additional study makes it possible to disambiguate the effects of preoperative embolization from those of resection.

Here, we present a retrospective case series of consecutive patients managed using this imaging and analysis protocol. We describe our approach to quantifying tumor devascularization using angiographic parameters alone using a new grading system. We also describe a quantitative approach to measuring the extent of tumor devascularization on the basis of volumetric analysis of postembolization, preresection MRI and explore the correspondence between 2D angiographic and 3D MR-based techniques.

Methods

Ethics statement

This retrospective case series was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Mount Sinai Hospital (IRB Serial Number: 23–1539). Written consent was waived for this series, which involved only retrospective record review. All patient records were anonymized and deidentified prior to analysis.

Protocol implementation

A protocol was implemented at Mount Sinai Hospital beginning in 2021, under which every patient undergoing preoperative embolization prior to tumor resection obtains a volumetric-quality MRI of the brain with and without contrast after tumor embolization (within 48 h) and prior to surgical resection. The present study retrospectively analyzes the treatment results of the first 30 consecutive patients enrolled under this protocol. An example is shown in Figure 1. We collected the following data: patient age, sex, tumor location, and tumor vascular supply. These are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Preparation embolization and resection of a right frontal convexity meningioma. Far Left Column: Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images in the axial (a), sagittal (b), and coronal (c) planes demonstrate an avidly and homogeneously enhancing right frontal convexity meningioma at the time of presentation. Middle-Left Column: A lateral angiogram demonstrated that the tumor was supplied entirely by the right middle meningeal artery (d). The tumor was completely embolized with n-BCA glue via the right middle meningeal artery, and the postembolization angiogram demonstrated no residual tumor blush (e). Middle-Right Column: Postembolization contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images in the axial (g), sagittal (h), and coronal (i) planes demonstrate near-complete loss of contrast enhancement relative to the corresponding preembolization images. At the time of resection, one day after embolization, the tumor was found to be completely devascularized, necrotic, and soft (f). The tumor was removed with minimal blood loss. Far Right Column: The immediate postoperative images corresponding to those in the other columns are shown in the axial (g), sagittal (h), and coronal (i) planes. These contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images demonstrate gross total resection.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and tumor angiographic anatomy.

| Patient characteristics | (N = 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean ± SEM | 61.50 ± 2.66 | |

| Female | 21 [70.00%] | |

| Laterality | ||

| Left side | 13 [43.33%] | |

| Right side | 13 [43.33%] | |

| Bilateral | 4 [13.33%] | |

| Feeder artery | ||

| External carotid | 9 [30.00%] | |

| Internal carotid | 3 [10.00%] | |

| External and internal carotid | 14 [46.67%] | |

| External carotid and vertebrobasilar circulation | 2 [6.67%] | |

| External and internal carotid and vertebrobasilar circulation | 2 [6.67%] | |

| Feeder artery embolized | ||

| External carotid | 23 [76.67%] | |

| Internal carotid | 2 [6.67%] | |

| External and internal carotid | 5 [16.67%] | |

| Vertebrobasilar circulation | 0 [0.00%] | |

| Tumor location | ||

| Anterior fossa lateral | 1 [3.33%] | |

| Anterior midline | 1 [3.33%] | |

| Clinoidal/Clival | 1 [3.33%] | |

| Convexity | 9 [30.00%] | |

| Cerebellopontine angle | 1 [3.33%] | |

| Foramen magnum | 2 [6.67%] | |

| Parasagittal/Falcine | 2 [6.67%] | |

| Petrous apex | 2 [6.67%] | |

| Sphenoid wing | 9 [30.00%] | |

| Spine/Other | 0 [0.00%] | |

| Tentorial | 2 [6.67%] | |

| Imaging characteristics | ||

| Extent of embolization | 36.7% ± 5.9% | |

Summary data from the cohort of (n = 30) consecutive patients who underwent postembolization MR imaging, including patient demographics, tumor anatomic locations, and tumor vascular supply as determined angiographically.

Catheter angiography and tumor embolization

Catheter-based cerebral angiography and microcatheter-directed embolization were performed at the discretion of the treating proceduralists. Average time between embolization and postembolization MRI in this study was 1 day, and the average time between embolization and resection was 2 days. All patients were treated by attending surgeons and interventionalists in the Neurosurgery Department at Mount Sinai Hospital. Feeding arteries were embolized as distally and completely as safely possible. Proximal occlusion without distal occlusion was only performed when distal access or penetration was determined to not be feasible or sage, or when a dangerous anastomosis was identified. Embolic agents were selected at the discretion of the interventionalists and included Onyx (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN), n-BCA glue (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ), and particles (including Embospheres; Merit Medical, South Jordan, UT). The use of n-BCA glue for tumor embolization was off-label and investigational as of the time of this study.

Patient imaging

MR images were acquired on a 1.5T scanner. Data were captured in all three cardinal planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal) in the following configuration: T1-weighted imaging, fast spin echo T2-weighted imaging, and axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery. Gadavist (Bayer, Berlin, Germany), a gadolinium-based agent, was used as a contrast agent. Axial T1-weighted volumetric images were used for quantitative analysis.

MR image data analysis

Tumor volumes were calculated using 3D Slicer (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts), an open-source software package. 20 MR images from two key time points were analyzed: before treatment (“preembolization”) and after treatment but before resection (“postembolization”). Semiautomated segmentations of contrast-enhancing regions were used to determine preoperative tumor volume, as well as nonembolized tumor volume after embolization, and total tumor volume after embolization. A new metric, extent of tumor embolization, ε, was defined as the percentage of tumor enhancement lost following embolization, relative to total tumor volume (equation (1)):

| (1) |

An exemplary image segmentation is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tumor segmentation for volumetric analysis before and after embolization. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the brain in a patient with a left lateral sphenoid wing meningioma before and after embolization (a–f), and with color-coding of the tumor segmentation used for volumetric analysis (g–l). All images are derived from contrast-enhanced T1 sequences. Far Left Column: Preembolization (a) axial, (b) sagittal, and (c) coronal images. Middle-Left Column: Postembolization, preresection (d) axial, (e) sagittal, and (f) coronal images. Middle-Right Column: Color-coded preembolization (g) axial, (h) sagittal, and (i) coronal images. Far Right Column: Color-coded postembolization (j) axial, (k) sagittal, and (l) coronal images. The magenta volumes reflect regions of contrast enhancement within the tumor at each time point. The green volumes represent regions of nonenhancing tumor. Extent of tumor embolization in this case was ε = 82%.

Varying parameters such as tumor location and vascular pedicles were recorded and analyzed for their relationship with resulting extent of tumor embolization. Resulting extent of tumor embolization was further discretized into three categories: low (ε < 25%), moderate (25% > ε > 75%), and high (ε > 75%) extent of tumor embolization.

Digital subtraction angiography image data analysis

In order to quantify angiographic outcomes following embolization, we developed a grading system for meningioma devascularization on the basis of angiographic findings alone. This grading system is described in a conference proceeding and is currently under review for publication. 21 This system is based on evaluation of the angiographic tumor blush. Devascularization was graded as 1 for partial (<50%) embolization, 2 for near-complete (50–99%) embolization, 3 for complete external carotid artery embolization, and 4 for complete embolization with no residual external, internal, or posterior circulation supply. The angiographic data from the patients in this cohort were reviewed, and embolization outcomes were graded according to this scale.

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among preoperative tumor volume, change in tumor size, and embolization extent. All demographic variables are presented descriptively. Change in tumor tissue volume following embolization is tested for significant difference from zero by a paired t-test. Multiple linear regression was used to estimate the change in tumor volume from preoperative tumor volume, controlling for the extent of tumor embolization. Chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables to determine if a nonrandom distribution of outcomes had emerged when examining the relationship between tumor locations, vascular supply, extent of tumor embolization, and angiographic devascularization grading. A single factor analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate the extent of tumor embolization across all tumor locations. Two sample t-tests were conducted to investigate whether the key tumor locations’ extent of tumor embolization were significantly different. The correspondence between volumetric extent of tumor embolization and angiographic devascularization grading was analyzed via a linear regression in which the categories of “low,” “moderate,” and “high” extent of tumor embolization were indexed as discrete numbers. All analyses were performed using Google Sheets (Alphabet Inc., Mountain View, California), XLMiner Analysis ToolPak (Frontline Systems Inc., Incline Village, Nevada), and RStudio (RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, Massachusetts).

Results

Patient summary

Thirty patients were included in this analysis. Of these, 21 (70%) were female with a mean age of 61.50 years (SE 2.66). Mean initial tumor volume was 61.24 cm³ (SE 9.59). Mean nonembolized tumor volume was 38.69 cm³ (SE 6.15). Total tumor volume after embolization treatment was 63.83 cm³ (SE 9.23). Patient baseline demographics are reported in Table 1.

Summary of extent of tumor embolization

The extent of tumor embolization was rated low (<25%) in 40% (12), moderate (25–75%) in 40% (12), and high (>75%) in 20% (6) of patients. Mean embolization extent was 36.7% (SE 5.9%).

Summary of tumor location

The locations of the tumor were identified as follows: 1 (3.33%) in the anterior fossa, 1 (3.33%) in the anterior midline, 1 (3.33%) in the clinoid/clival region, 9 (30.00%) over the convexities, 1 (3.33%) in the cerebellopontine angle, 2 (6.67%) at the foramen magnum, 2 (6.67%) in the parasagittal/falcine region, 2 (6.67%) at the petrous apex, 9 (30.00%) on the sphenoid wing, 0 (0.00%) in the spine or other regions, and 2 (6.67%) along the tentorium. General tumor location and vascular supply are reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Tumor locations and associated feeding arteries.

| External carotid artery | Internal carotid artery | p-value * | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All locations | Meningeal | Internal maxillary | Occipital | Ascending pharyngeal | Other ECA | Ophthalmic | ACA | MCA | Extradural ICA | Vertebrobasilar circulation | |

| Anterior fossa – lateral | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.64 |

| Anterior midline | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.64 |

| Clinoidal/Clival | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.44 |

| Convexity | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | <<0.01 |

| Cerebellopontine angle | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.64 |

| Foramen magnum | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.44 |

| Parasagittal/Falcine | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Petrous apex | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.44 |

| Sphenoid wing | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | << 0.01 |

| Spine/Other | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tentorial | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.16 |

MMA: middle meningeal and accessory meningeal artery; IMAX: internal maxillary artery; ECA: external carotid artery; ACA: anterior cerebral artery; MCA: middle cerebral artery; extradural ICA: meningohypophyseal and inferolateral trunks.

Tumor location is tabulated here with respect to arterial supply. The p values reported represent significance from the chi-squared test statistic for categorical groups. Statistically meaningful vascular supplies identified through chi-squared test highlighted in gray.

Threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Table 3.

Tumor locations and resulting devascularization.

| Angiography | MRI | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Low extent of embolization | Moderate extent of embolization | High extent of embolization | Average extent of embolization | |

| All locations | 30 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 36.69% |

| Anterior fossa – lateral | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29.49% |

| Anterior midline | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.67% |

| Clinoidal/Clival | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6.22% |

| Convexity | 9 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 54.77%* |

| Cerebellopontine angle | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5.88% |

| Foramen magnum | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 21.12% |

| Parasagittal/Falcine | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 69.60%* |

| Petrous apex | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 21.11% |

| Sphenoid wing | 9 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 27.73%* |

| Spine/Other | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tentorial | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 45.59% |

Occurrences of tumor location with respect to devascularization by feeding vessels and volumetric extent of embolization are tabulated here. The p values reported represent significance from the chi-squared test statistic for categorical groups. The key tumor locations (parasagittal, convexity, and sphenoid wing) are further investigated and compared against the rest of the patient group.

Threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 and the asterisk denotes statistical significance.

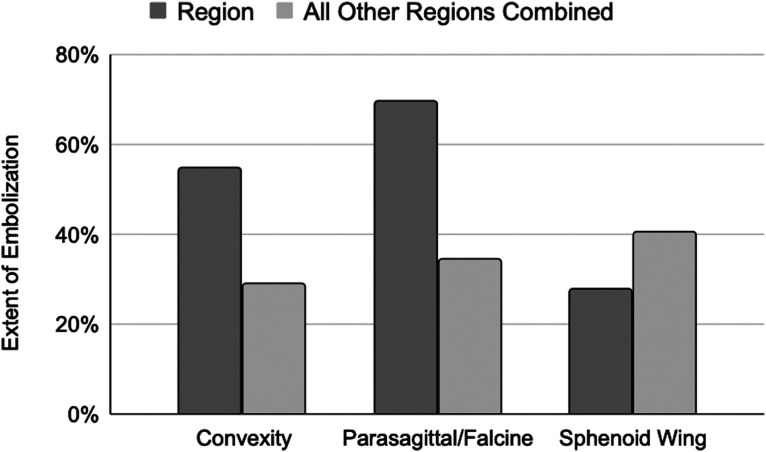

Three tumor locations were found to have statistically distinct distributions of extent of tumor embolization: parasagittal, convexity, and sphenoid wing regions. Further comparisons of the extent of embolization from these key groups against the rest of the patient group were conducted using two-sided t-tests. Convexity and parasagittal meningiomas trended toward greater extent of embolization, whereas sphenoid wing meningiomas trended toward lesser extent of embolization, but this study was not powered to detect statistical significance in these subgroup analyses. These results are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Extent of tumor embolization in key locations in contrast to all other tumor locations. Extent of tumor embolization is compared for the key tumor locations discussed in the text (parasagittal, convexity, and sphenoid wing). These are contrasted with the average extent of tumor embolization of all other groups and a two sample t-test was conducted for all pairs. Tumors in the parasagittal/falcine and convexity location had higher likelihood of having a high and moderate extent of embolization, respectively, whereas sphenoid wing tumors were likely to have lower extent of embolization as compared to other regions. ** The p value for these trends was greater than 0.05.

Summary of vessels supplying tumors

In this study, nine tumors were fed exclusively from the ECA with a mean extent of embolization of 55.9% (SE 11.3%) and three tumors were fed exclusively from the ICA with a mean extent of embolization of 32.6% (SE 29.5%). Additionally, 14 tumors were fed both the internal and external carotid arteries with a mean extent of embolization 27.8% (7.6%). Two tumors were fed by the external carotid artery and the vertebrobasilar circulation with a mean extent of embolization of 13.1% (SE 13.1%), and two tumors were fed by the internal and external carotid arteries and vertebrobasilar circulation with a mean extent of embolization 27.7% (14.6%). These results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Extent of meningioma embolization stratified by vascular pedicle grouping.

| Vascular pedicle groupings | N | Mean extent of tumor embolization ± SE |

|---|---|---|

| ECA | 9 | 56% ± 11% |

| ICA | 3 | 33% ± 30% |

| ECA + ICA | 14 | 28% ± 8% |

| ECA + Vertebrobasilar | 2 | 13% ± 13% |

| ECA + ICA + Vertebrobasilar | 2 | 28% ± 15% |

Extent of tumor embolization is tabulated with respect to vascular pedicle groups supplying each tumor.

The vessels feeding the tumors were identified as follows. Meningeal arteries (including the middle meningeal and accessory meningeal arteries) supplied 25 of the 30 meningiomas in this series. Tumors were supplied by the internal maxillary artery in five cases, by the occipital artery in five cases, by the ascending pharyngeal artery in one case, and by other external carotid artery branches (including the superficial temporal artery) in two cases. A number of tumors also received arterial supply from internal carotid artery branches: there was supply from the ophthalmic artery in eight cases, the anterior cerebral artery in two cases, the middle cerebral artery in three cases, and by the extradural internal carotid arteries (meningohypophyseal trunk or inferolateral trunk) in eight cases. There were four cases in our series in which the tumor was supplied at least in part from the vertebrobasilar circulation. These data are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Extent of meningioma embolization stratified by vascular pedicle.

| Angiography | MRI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial feeders | N | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | p-value* | Average extent of embolization | Low extent of embolization | Moderate extent of embolization | High extent of embolization | p-value* | |

| External carotid artery | Meningeal | 25 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 0.20 | 38.27% | 9 | 11 | 5 | 0.33 |

| Internal maxillary | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.90 | 25.91% | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.45 | |

| Occipital | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0.04 | 36.85% | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0.07 | |

| Ascending pharyngeal | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.39 | 0.00% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.37 | |

| Other ECA | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 34.74% | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.61 | |

| Internal carotid artery | Ophthalmic | 8 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0.26 | 11.22% | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0.03 |

| ACA | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.30 | 23.71% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.37 | |

| MCA | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.30 | 9.81% | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.37 | |

| Extradural ICA | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0.03 | 13.58% | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0.03 | |

| Vertebrobasilar circulation | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0.11 | 20.40% | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.37 | |

Extent of tumor embolization is tabulated with respect to vascular pedicles supplying each tumor and to the angiographic devascularization grade and volumetric extent of embolization achieved. Threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and vascular pedicles meeting this threshold across devascularization grades are highlighted in gray.

Correlations among preoperative tumor volume, change in tumor size, and extent of tumor embolization

There was no evidence of significant change in tumor tissue volume following embolization over the time frame used in this study (p = 0.590). No significant statistical correlations were found between preoperative tumor volume and extent of tumor embolization (p = 0.382, r = 0.165), preoperative tumor volume and relative change in tumor size (p = 0.643, r = −0.088), or extent of tumor embolization and relative change in tumor size (p = 0.693, r = −0.066). Additionally, a multiple linear regression concluded that embolization extent was not statistically associated with change in tumor size while controlling for preoperative tumor volume (p = 0.867).

Correspondence between extent of tumor embolization and angiographic devascularization grading

The results of the angiography-based devascularization grading were as follows: Grade 1 devascularization was achieved in 2 (6.67%) patients, Grade 2 devascularization in 13 (43.33%) patients, Grade 3 devascularization in 6 (20.00%) patients, and Grade 4 devascularization in 9 (30.00%) patients. Angiographic devascularization grade was significantly and strongly correlated with volumetric extent of tumor embolization as measured on MRI (p << 0.001, r = 0.75). Overall, an adjusted r-squared value of 0.59 indicates that approximately 59% of the variance in extent of tumor embolization as quantified by MRI can be explained by the angiographic devascularization grading. On average, an increase of angiographic grade of 1 corresponds to an increase in the extent of tumor embolization by 60%. This correlation is significant, with a p-value of significantly less than 0.01. These data are reported in Table 6 and Figure 4.

Table 6.

Relationship between devascularization grade and extent of tumor embolization.

| MRI extent of tumor embolization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiographic grading | Low | Moderate | High | p-value* |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.14 |

| 2 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0.02 |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0.14 |

| 4 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0.05 |

| Total | 12 | 12 | 6 | 0.30 |

This table illustrates the correspondence between tumor devascularization grade as determined using purely angiographic methods, and volumetric extent of embolization as measured using MRI. Overall, an adjusted r-squared value of 0.59 indicates that approximately 59% of the variance in extent of tumor embolization as assessed by MRI can be explained by the angiographic devascularization grading. On average, an increase of angiographic grade of 1 increases the extent of tumor embolization category (from low to high) by 60% within that category. This correlation was statistically significant under logistic regression, with a p-value of significantly less than 0.01.

Figure 4.

Relationship between extent of embolization and devascularization grading. Extent of tumor embolization as assessed by MRI using the methods described here corresponds closely to the devascularization grade obtained through angiographic assessment.

Complications

There were no large or symptomatic ischemic events detected on postembolization, preoperative imaging in this study cohort. One patient experienced an oculomotor nerve palsy after embolization of meningohypophyseal and inferolateral trunk branches to a medial sphenoid wing meningioma.

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the agreement between the 2D angiographic and 3D MR-based measurements of meningioma devascularization following embolization. Moreover, this work defines a new parameter, “extent of embolization,” which is defined in analogy to the more familiar “extent of resection,” and is intended to facilitate objective, quantitative, and increasingly automated assessment of preoperatively embolized tumors. As the parameter is derived from periprocedural volumetric images, it is spatially resolved in nature. The data presented in this study confirm that the extent of tumor embolization, as defined here, is strongly correlated with the degree of tumor devascularization observed angiographically. This correlation suggests that there is consistency in our approaches to assessing tumor embolization across imaging modalities.

Intracranial tumor location influences the relationship with regional vascular feeders. Therefore, each tumor location is expected to have a characteristic distribution of vascular feeders that is nonrandom, with anatomically “near” arteries having higher likelihood of feeding a given tumor. In turn, the specific vascular feeder and number of vascular branches recruited to supply a specific tumor informs the likely extent of embolization that can be achieved for a given tumor without causing adverse events. Table 2 demonstrates that nonrandom distributions of vascular feeding networks have emerged for convexity, parasagittal/falcine, and sphenoid wing meningiomas. Convexity and parasagittal/falcine tumors are reliably supplied by the meningeal branch of the ECA. Sphenoid wing tumors are frequently supplied via meningeal arteries, as well as commonly supplied by the internal maxillary branch of the ECA and ophthalmic, extradural ICA, and MCA. Extent of tumor embolization was found to vary according to tumor location and the vascular pedicle supplying the tumor. In particular, we show in Table 3 that parasagittal, convexity, and tentorial meningiomas, tumors that are primarily fed by the external carotid artery branches, have the highest extents of embolization. External carotid artery branches are typically better candidates for tumor embolization since embolization is not expected to cause neurologic deficits.22–25 By contrast, embolization of intradural internal carotid artery branches is undertaken less commonly, due to elevated risks of causing significant neurologic deficits. These effects are seen in Table 4 in which vascular supply from internal carotid branches, primarily the ophthalmic artery and extradural ICA branches, is associated with lower extent of tumor embolization via volumetric assessment. A more conservative approach to embolization of tumors receiving partial supply from the ophthalmic artery (such as medial sphenoid wing meningiomas) explains the trend toward less extensive tumor embolization in such tumors. While the differences in extent of embolization among parasagittal, convexity, and tentorial meningiomas and nonparasagittal, nonconvexity, and nontentorial meningiomas, respectively, did not reach the p < 0.05 threshold for statistical significance in this study, we suspect that this is in part due to underpowering of subgroup analyses in this small initial cohort. As we expand our protocol beyond these 30 patients, we expect to be able to reach more definitive conclusions regarding extent of embolization achievable in tumors in these locations. Table 5 demonstrates the nonrandom distributions of angiographic grades for occipital feeders and extradural ICA feeders, as well as nonrandom distributions of extent of meningioma embolizations for ophthalmic and extradural ICA feeders. The angiographic grading distribution for occipital feeders indicates typical Grade 2 results. Both the angiographic grading distribution and extent of embolization class indicate noncomplete embolization of tumors fed by the extradural ICA (Grade 2 & 3 angiographic grades and low to moderate extent of embolization classes). This finding is expected given that embolization of internal carotid artery branches is typically avoided due to the potential severity of complications arising from distal embolization in intracranial branches supplying the brain. Ophthalmic-fed tumors are typically associated with low to moderate extent of embolization since interventionists commonly avoid ophthalmic artery embolization due to the risk of ischemic visual compromise. Table 6 demonstrates nonrandom distributions of extent of tumor embolization class for angiographic grades 2 and 4. Angiographic grade 2 corresponds with low and moderate extent of embolization indicating that a subjective angiographic assessment of 50%–99% tumor embolization achieves an MRI-derived 0%–75% tumor embolization. Angiographic grade 4 corresponds with moderate and high extent of embolization indicating that a subjective anagraphic assessment of 100% embolization archives an MRI-derived 25%–100% tumor embolization. The variation between scales is the result of imperfect agreement between classifications, greater subjective variability in observer measurements for angiographic grades and increased information provided via 3-dimensional MRI compared to 2-dimensional angiography. Angiographic grades 1 and 3 did not reach significance as the p < 0.05 threshold, however, we suspect that this is a result of subgroup analysis underpowered and will trend toward significance as more patients are enrolled in our protocol. These findings may inform future clinical decision-making in the comprehensive treatment of meningiomas by helping to quantify the degree to which a given meningioma may benefit from preoperative embolization.

The average time between embolization and postembolization MRI in this study was 1 day, and the average time between embolization and resection was 2 days. Over these time scales, no statistically significant changes in tumor size following embolization were observed, even among extensively embolized tumors. Previous studies have shown that there is a reduction in tumor volume postembolization, with the most pronounced change in volume noted in the first six months. However, in this study, given the small time scale (1–2 days), no significant differences were noted.15,26,27

Intraoperative blood loss remains an unreliable parameter to use in quantifying the efficacy of meningioma embolization. Other advantages to embolization have been identified including softer textures and liquefactive necrosis. However, the precise nature of such changes has not been characterized with rigor in a quantifiable manner. Volumetric analysis of angiographic and MR imaging methods as demonstrated here may represent initial steps toward a more complete understanding of the intratumoral changes induced by extensive embolization.

Our protocol calling for postembolization, preoperative MRI of meningiomas offers clinicians the unique opportunity to objectively assess the degree to which preoperative embolization affected the tumor, and to quantify that contribution of successful embolization to patient outcomes. Up to this point, there has been no parameter to complement “extent of resection,” a term typically used to define operative success of tumor resection. The ability to study how “extent of embolization” and “extent of resection” interact in terms of overall patient outcomes will help further guide clinician decision-making on the use of meningioma embolization.

Limitations

This remains the first case series to use quantitative analysis of additional postembolization preresection MRI to characterize the extent of tumor embolization in an unbiased fashion, after endovascular embolization and before surgical resection. The findings in this case series remain limited due to the limited sample size and the retrospective nature of the study, as well as by the selection bias intrinsic to the decision to refer some but not other patients for preoperative embolization. Further detailed and quantitative studies will also be required to characterize changes in tumor morphology due to intratumoral or peritumoral edema (expansion) or necrosis and involution (shrinking).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility and utility of additional MR imaging prior to the resection of embolized tumors, enabling precise quantification of embolization extent prior to tumor removal. This study found an average extent of embolization of 37% in tumors selected for preoperative embolization and demonstrates a strong correlation between extent of tumor embolization as assessed postprocedurally using MRI, on the one hand, and intraprocedurally using angiography, on the other hand. Additionally, we have demonstrated that the extent of embolization of a meningioma depends on both tumor location and on the associated vascular pedicles, with convexity and lateral sphenoid wing meningiomas supplied by the middle meningeal artery tending to yield most extensively to preoperative embolization. Assessment of the extent of embolization using volumetric imaging and quantitative methods, such as those demonstrated here, may yield additional insights into the intratumoral effects of embolization beyond devascularization, including the induction of tumor necrosis and other changes facilitating tumor resection or improved overall outcomes in the comprehensive treatment of meningiomas. A more detailed understanding of the quantitative correspondences among tumor location, vascular supply, and extent of embolization will emerge as these techniques are applied to a growing patient cohort.

Footnotes

Ethics statement: This retrospective case series was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (IRB Serial Number: 10708–005). Written consent was waived for this series, which involved only retrospective record review. All patient records were anonymized and deidentified prior to analysis.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Denzel E. Faulkner https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7760-5030

Rui Feng https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3052-035X

Stavros Matsoukas https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5902-0637

Fred Kwon https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0893-9472

Tomoyoshi Shigematsu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3463-0222

References

- 1.Wei Z, Mallela AN, Faramand A, et al. Long-term survival in patients with long-segment complex meningiomas occluding the dural venous sinuses: illustrative cases. J Neurosurg Case Lessons Epub ahead of print 17 May 2021; 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huntoon K, Toland AMS, Dahiya S. Meningioma: a review of clinicopathological and molecular aspects. Front Oncol 2020; 10: 579599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber P, Schwyzer L, Klinger E, et al. Longitudinal imaging of tumor volume, diffusivity, and perfusion after preoperative endovascular embolization in supratentorial hemispheric meningiomas. World Neurosurg 2018; 120: e357–e364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsoukas S, Feng R, Gilligan J, et al. Combined transarterial and percutaneous preoperative embolization of transosseous meningioma. Interv Neuroradiol 2023; 29: 618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schartz D, Manganaro M, Szekeres D, et al. Direct percutaneous puncture versus transarterial embolization for head and neck paragangliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Interv Neuroradiol 2023; 29: 15910199231188859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jumah F, AbuRmilah A, Raju B, et al. Does preoperative embolization improve outcomes of meningioma resection? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev 2021; 44: 3151–3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah AH, Patel N, Raper DMS, et al. The role of preoperative embolization for intracranial meningiomas: a review. J Neurosurg 2013; 119: 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Li D-H, Lu Y-H, et al. Preoperative embolization versus direct surgery of meningiomas: a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg 2019; 128: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ilyas A, Przybylowski C, Chen C-J, et al. Preoperative embolization of skull base meningiomas: a systematic review. J Clin Neurosci 2019; 59: 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, et al. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 1997; 21: 1455–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara H, Ishihara S, Niimi J, et al. The safety and efficacy of preoperative embolization of meningioma with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Interv Neuroradiol 2015; 21: 624–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean BL, Flom RA, Wallace RC, et al. Efficacy of endovascular treatment of meningiomas: evaluation with matched samples. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 1675–1680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis JA, D’Amico R, Sisti MB, et al. Pre-operative intracranial meningioma embolization. Expert Rev Neurother 2011; 11: 545–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubel GJ, Ahn SH, Soares GM. Contemporary endovascular embolotherapy for meningioma. Semin Intervent Radiol 2013; 30: 263–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman BT, Lin E, Pile-Spellman J. Definitive embolization of meningiomas. A review. Interv Neuroradiol 2005; 11: 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grand C, Bank WO, Balériaux D, et al. Gadolinium-enhanced MR in the evaluation of preoperative meningioma embolization. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993; 14: 563–569. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teasdale E, Patterson J, McLellan D, et al. Subselective preoperative embolization for meningiomas: a radiological and pathological assessment. J Neurosurg 1984; 60: 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asai K, Nakamura H, Kinoshita M, et al. Preoperative Embolization of Lateral Ventricular Tumors. World Neurosurg 2022; 161: 123–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aihara M, Naito I, Shimizu T, et al. Preoperative embolization of intracranial meningiomas using n-butyl cyanoacrylate. Neuroradiology 2015; 57: 713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn Reson Imaging 2012; 30: 1323–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsoukas S, et al. “Introduction and Validation of a New Meningioma Embolization-Efficacy Grading Scale: A Retrospective Study of 80 Patients,” in 32nd Annual Meeting North American Skull Base Society, Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Feb. 2023, p. S030.

- 22.Ban SP, Hwang G, Byoun HS, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma. Radiology 2018; 286: 992–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Link TW, Boddu S, Paine SM, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: a series of 60 cases. Neurosurgery 2019; 85: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joyce E, Bounajem MT, Scoville J, et al. Middle meningeal artery embolization treatment of nonacute subdural hematomas in the elderly: a multiinstitutional experience of 151 cases. Neurosurg Focus 2020; 49: E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TP. Embolization in the external carotid artery. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17: 1897–1912; quiz 1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bendszus M, Martin-Schrader I, Schlake HP, et al. Embolisation of intracranial meningiomas without subsequent surgery. Neuroradiology 2003; 45: 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendszus M, Martin-Schrader I, Warmuth-Metz M, et al. MR imaging- and MR spectroscopy-revealed changes in meningiomas for which embolization was performed without subsequent surgery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000; 21: 666–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]