Abstract

Background

The typical clinical symptoms of psittacosis pneumonia include fever, dry cough, and chills. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss is a relatively uncommon condition in pneumonia caused by Chlamydia psittaci. In this study, we reported a rare case of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia presented as hearing loss.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old man presented to our hospital with sudden hearing loss, cough with sputum, and fever for the last three days. Chest computed tomography revealed inflammation of the left lung and poor response to broad-spectrum antibiotics. The metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid identified the sequence of Chlamydia psittaci. Subsequently, antibiotic treatment was adjusted to doxycycline hydrochloride and moxifloxacin, resulting in significant improvement in both hearing loss and lung infection.

Conclusions

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss as an extrapulmonary feature of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia is extremely rare. Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, this case report described a patient with sudden bilateral sensorineural hearing loss as a presenting feature of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia, illustrating the importance of the extrapulmonary features of atypical pneumonia. The mNGS test could provide early diagnosis. Many patients had a good prognosis with prompt and effective treatment.

Keywords: Chlamydia psittaci, Pneumonia, Hearing loss, mNGS

Background

Chlamydia psittaci is a zoonotic infectious disease caused by transmission of Chlamydia psittaci from birds to humans. Human infection is mainly manifested as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [1]. Chlamydia psittaci infection in humans mainly involves the lungs and constitutes about 1% of all community-acquired pneumonia [1]. The incubation period of this disease is generally 5–14 days [2]. The typical clinical manifestations are high fever, headache, myalgia, cough, and dyspnea. After infection with Chlamydia psittaci, humans can present with asymptomatic infection and mild, non-specific diseases to systemic multi-organ dysfunction, severe pneumonia, and even death [3–6].

Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia, which presents as hearing loss, is rare. However, in a prospective study, the positive rate of Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA was significantly increased in patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Consequently, we suggest that C. pneumoniae may be a possible cause of sudden sensorineural hearing loss [7]. In this study, we reported a case of Chlamydia psittaci pneumonia with hearing loss as the initial manifestation. Based on relevant literature review, we summarized its clinical characteristics, diagnostic and treatment points, and possible mechanisms.

Case presentation

A 65-year-old farmer presented to our hospital on November 13, 2022, complaining of sudden binaural hearing loss and fever for three days. There was no history of vertigo, otalgia, or trauma. The patient had a fever with a peak temperature of 39–40 ℃, chills, no nasal congestion, no runny nose, no sore throat, a cough without apparent expectoration, and no chest tightness, shortness of breath, or chest pain. He presented with a white blood cell (WBC) count of 3.89 × 109/L (normal 3.5–9.5 × 109/L), an elevated neutrophil percentage of 83.2% (normal 40–75%), and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 101.89 mg/L (normal < 8 mg/L). The initial chest computed tomography (CT) scan (three days after onset) showed air-space consolidation with inflammatory exudation in the lower lobe of the left lung. The patient denied any history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, or other chronic diseases.

Examination revealed normal tympanic membranes, a temperature of 39.5 °C, increased tactile tremor in the affected lung, and a little moist rale in auscultation, which was inconsistent with severe clinical manifestations. After admission, the liver function was abnormal, including glutamic pyruvic transaminase (53 IU/L [9–50 IU/L]), glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (59 IU/L [15–40 IU/L]), hyponatremia (131.5 mmol/L [137–147 mmol/L]).

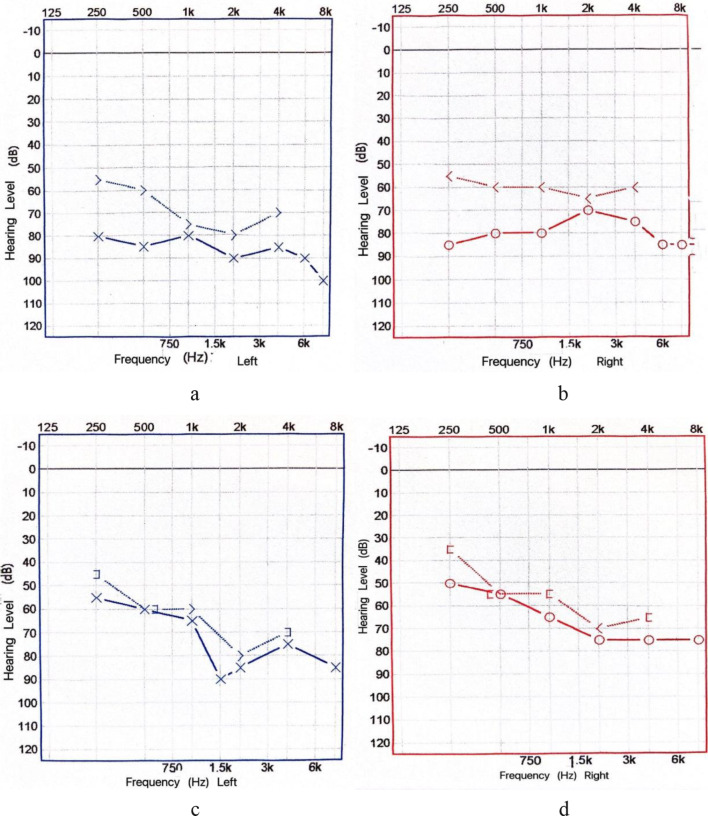

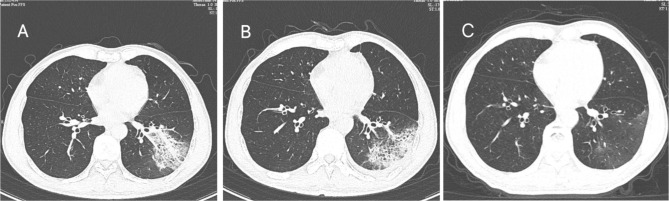

The patient received empirical antibiotic treatment of moxifloxacin following the guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. During hospitalization, audiometry was performed: the hearing threshold of the left ear was 80,85,80,90,85,90 dB and the hearing threshold of the right ear was 85,80,80,70,75,85 dB (Fig. 1a-b). Therefore, Mecobalamin was added to improve hearing. After the above treatment, the patient still had recurrent fever and hearing loss. Consequently, the patient underwent a bronchoscopy examination and BALF mNGS test on the fourth day after admission to the hospital. After confirming that the disease was caused by C. psittaci, antibiotic therapy was changed to tetracycline combined with moxifloxacin. Two days later, the patient’s temperature returned to normal, and his hearing significantly improved. The hearing threshold of the left ear was 55,60,65,90,85,85 dB, and that of the right ear was 50,55,65,75,75,75 dB (Fig. 1c-d). On day 6 post-admission, CRP decreased to 15.5 mg/L, and the lung CT showed improvement in the infection lesions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Pure tone audiogram before treatment (a, b). Pure tone audiogram after treatment (c, d)

Fig. 2.

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans of a 65-year-old man with C. psittaci pneumonia. The initial CT scan (3 days after onset) shows air-space consolidation with inflammatory exudation in the lower lobe of the left lung (A). One week after treatment, the chest CT scan showed the lesions were smaller than before, and most of the lesions were close to the subpleural (9 days after the onset) (B). On follow-up, the consolidation was basically absorbed (30 days after the onset) (C)

Discussion and conclusion

Using “psittacosis” or “Chlamydia psittaci” and “hearing” as search terms, we searched PubMed for case reports before April 27, 2024, and found only two cases. One case was a 61-year-old farmer [8] who was hospitalized with sudden binaural hearing loss and high-profile tinnitus. Physical examination revealed that the patient had a fever and wet rales in the lower lobe of the right lung. The patient had a history of fever, severe headache, and diarrhea for two weeks before his admission to the hospital. A chest X-ray showed consolidation of the right lower lobe. The examination revealed normal tympanic membranes. Pure tone audiometry indicated bilateral sensorineural hearing loss with a hearing threshold of 50–85 dB. After 12 h of prednisolone treatment (initial dose 60 mg/day), the patient’s hearing recovered. The subsequent positive serology of Chlamydia psittaci confirmed that the patient was infected with Chlamydia psittaci. Subsequently, the patient was administered erythromycin combined with amoxicillin. One month later, all symptoms disappeared, and the hearing subjectively returned to normal. The audiogram showed mild high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss, consistent with the patient’s age. Prednisolone was gradually reduced and maintained for 10 weeks. After one year of follow-up, the patient did not experience any symptom recurrence. The other case was a 15-year-old female patient with the Cogan syndrome [9]. The Cogan syndrome is a group of rare and serious disabling diseases, which manifests as ocular inflammation, vestibular, auditory dysfunction, and other systemic symptoms. The patient presented with recurrent interstitial keratitis and uveitis, accompanied by bilateral sensorineural deafness, tinnitus, and vertigo. The ocular symptoms were poorly controlled with steroid eye drops. Laboratory examination revealed that the Chlamydia antibody IgM was repeatedly positive, with the titer fluctuating from 1:32 to 1:64. The Chlamydia psittaci was cultured and isolated from the patient’s conjunctival swab, and she was subsequently treated with doxycycline. The ocular symptoms were controlled, but the patient eventually died due to sudden cardiovascular events.

Chlamydia psittaci (C. psittaci) is a Gram-negative, aerobic, intracellular parasite. These pathogens can infect humans through respiratory secretions or feces from infected birds when humans inhale the pathogen. Even brief contact with birds or their excretions and activities not involving direct exposure to excretions (such as mowing or landscaping) can lead to systemic infection [10, 11]. Human-to-human transmission of psittacosis is rare but possible [12–15]. Before the antibiotic era, mortality from C. psittaci pneumonia was up to 15–20% [16]. However, with the use of targeted antibiotics, mortality rates have significantly decreased. Chlamydia infection typically presents with fever, headache, general malaise, and myalgia. It often presents with a dry cough accompanied by dyspnea or chest tightness, occasionally accompanied by a slow pulse, spleen enlargement, or a non-specific rash [17]. Lung auscultation often reveals no specific findings, which may underestimate the severity of the disease. Imaging often shows infiltration of the lung parenchyma, with rare pleural effusion. Compared to other pneumonia cases, patients often have low white blood cell counts and present with a range of extrapulmonary manifestations, including keratoconjunctivitis, gastrointestinal symptoms (vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea), arthritis, jaundice, myocarditis, endocarditis, spinal neuritis, encephalitis, meningoencephalopathy, optic neuritis, and multi-organ failure [18–23]. These findings are consistent with those observed in this patient.

Sudden hearing loss due to infection is relatively rare, typically resulting from viral infections, including mumps, measles, varicella-zoster, and influenza viruses [24]. Based on a review of the literature, there is no documented mechanism for hearing loss caused by C. psittaci. In contrast, related literature has been published on hearing loss caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae, which is also a member of the Chlamydiae genus [9]. This may offer valuable insights into the hearing loss mechanisms associated with C. psittaci. Among patients with sudden deafness, the incidence of acute and chronic C. pneumoniae infections is significantly higher than in the general population [9]. The C. psittaci infection can lead to vascular damage, with white blood cells, cholesterol, and other substances accumulating at the site of damaged blood vessels, resulting in fat accumulation and vascular obstruction, disrupting the inner ear’s blood microcirculation, and leading to hearing loss [25]. This may account for the hearing loss observed in the case of C. psittaci pneumonia.

C. psittaci infection is fundamentally a systemic infection primarily affecting the lungs, which can also lead to multi-system dysfunction. Patients exhibit various clinical manifestations with varying degrees of severity. If promptly and accurately diagnosed and treated, the overall prognosis is favorable. The patient in this case report presented with sudden sensorineural deafness as the initial symptom and extrapulmonary manifestations, which are rare in clinical practice. In this study, the patient exhibited high fever, lung consolidation, and significantly elevated inflammatory markers. Quinolone antibiotics were initially empirically selected. After confirming C. psittaci pneumonia, sensitive antibiotics were promptly adjusted. There was rapid improvement in hearing loss and respiratory symptoms. Some patients with C. psittaci pneumonia may not have a history of bird exposure. When clinicians do not carefully inquire about the history or patients lack a history of exposure, they are often treated as ordinary community-acquired pneumonia. During the diagnostic process, C. psittaci testing is often not included in routine tests. Furthermore, traditional laboratory methods struggle to diagnose C. psittaci infection, leading to misdiagnoses. If antibiotics are not promptly adjusted, the disease can progress and the prognosis can be poor. Diagnostic tools, including culture, serologic test, and PCR-based methods, are available but prone to false negative results. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has been increasingly used in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, particularly when conventional diagnostic approaches have limitation. Detection of nucleic acid sequence of C. psittaci in respiratory tract samples by metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is effective for early diagnosis of severe C. psittaci pneumonia. Diagnostic tools, including culture, serologic test, and PCR-based methods, are available but prone to false negative results. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has been increasingly used in the diagnosis of infectious diseases, particularly when conventional diagnostic approaches have limitation. Detection of nucleic acid sequence of C. psittaci in respiratory tract samples by metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) is effective for early diagnosis of C. psittaci pneumonia. For patients with sudden sensorineural deafness accompanied by pneumonia, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of C. psittaci infection, promptly perform BALF or sputum mNGS tests, adjust anti-infection regimens, and improve outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient and his family for agreeing to use all the data for research purposes, and specifically, for publication of this report. We thank Home for Researchers editorial team (www.home-for-researchers.com) for language editing service.

Abbreviations

- BALF

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CT

Computed tomography

- mNGS

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing

- WBC

White blood cell

- CAP

Community acquired pneumonia

Author contributions

HHW participated in manuscript drafting. PPZ and SYF collected and analyzed clinical data. YYR and XMW prepared all the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscipt.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongyang Hospital affiliated to Wenzhou Medical University (Number 2024-YX-065). An informed consent was signed by the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hogerwerf L, DE Gier B, Baan B, Hoek VANDER. Chlamydia psittaci (psittacosis) as a cause of community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(15):3096–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balsamo G, Maxted AM, Midla JW, et al. Compendium of measures to Control Chlamydia psittaci infection among humans (psittacosis) and Pet Birds (Avian Chlamydiosis), 2017. J Avian Med Surg. 2017;31(3):262–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heddema ER, van Hannen EJ, Dium B, et al. An outbreak of psittacosis due to Chlamydophila psittaci genotype A in a veterinary teaching hospital. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(11):1571–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewardson AJ, Grayson ML, Psittacosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:7–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovácová E, Majtán J, Botek R, Bokor T, Blaskovicová H, Solavová M, Ondicová M, Kazár J. A fatal case of psittacosis in Slovakia, January 2006. Euro Surveill. 2007;12(8):E0708021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yilmazlar A, Ozcan B, Kaplan N, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome caused by psittacosis. Turk J Med Sci. 2000;30:199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dünne AA, Wiegand A, Prinz H, Slenczka W, Werner JA. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA seropositivity and sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Pol. 2004;58(3):427–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewis C, McFerran DJ. Farmer’s ear’: sudden sensorineural hearing loss due to Chlamydia psittaci infection. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111(9):855–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darougar S, John AC, Viswalingam M, Cornell L, Jones BR. Isolation of Chlamydia psittaci from a patient with interstitial keratitis and uveitis associated with otological and cardiovascular lesions. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978 Oct;62(10):709–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Williams J, Tallis G, Dalton C, et al. Community outbreak of psittacosis in a rural Australian town. Lancet. 1998;351(9117):1697–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telfer BL, Moberley SA, Hort KP, et al. Probable psittacosis outbreak linked to wild birds. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(3):391–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes C, Maharg P, Rosario P, et al. Possible nosocomial transmission of psittacosis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18(3):165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallensten A, Fredlund H, Runehagen A. Multiple human-to-human transmission from a severe case of psittacosis, Sweden, January-February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(42):20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito I, Ishida T, Mishima M, et al. Familial cases of psittacosis: possible person-to person transmission. Intern Med. 2002;41(7):580–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuigan CC, McIntyre PG, Templeton K. Psittacosis outbreak in Tayside, Scotland, December 2011 to February 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(22):20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunnahoo GL, Hampton BC. Psittacosis: occurrence in the United States and report of 97% mortality in a shipment of birds while under quarantine. Public Health Rep. 1945;60(13):354–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vande Weygaerde Y, Versteele C, Thijs E, et al. An unusual presentation of a case of human psittacosis. Respir Med Case Rep. 2018;23:138–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanham JG, Doyle DV. Reactive arthritis following psittacosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1984;23(3):225–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean D, Oudens E, Bolan G, Padian N, Schachter J. Major outer membrane protein variants of Chlamydia trachomatis are associated with severe upper genital tract infections and histopathology in San Francisco. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(4):1013–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schinkel AF, Bax JJ, van der Wall EE, et al. Echocardiographic follow-up of Chlamydia psittaci myocarditis. Chest. 2000;117:1203–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devlin RK, Andrews MM, von Reyn CF. Recent trends in infective endocarditis: influence of case definitions. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19(2):134–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walder G, Gritsch W, Wiedermann CJ, et al. Co-infection with two Chlamydophila species in a case of fulminant myocarditis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):623–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punter MNM, Varma AR. Myeloradiculitis with meningoencephalopathy and optic neuritis in a case of previous Chlamydia psittaci infection. BMJ Case Rep; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Booth JB. (1987) Sudden and fluctuant sensorineural hearing loss. In Scott-Brown’s Otolaryngology. 5th Edition. (Kerr, A. G., ed.), Butler and Tanner, Frome, Somerset, pp 387–434.

- 25.Ao Hua-fei. Mao Xiao-hui, Guo Zhu-ying. Correlation between Chlamydia pneumoniae and sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ (Medical Science). 2009;29(12):1487–90. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.