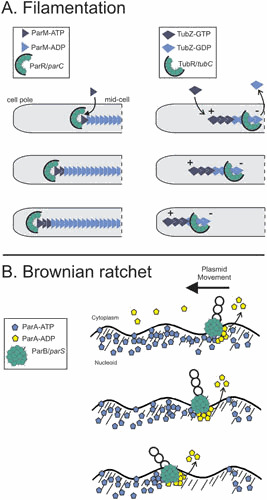

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of partition NTPase-driven plasmid movement. (A) Filamentation. (Left) Filament growth and catastrophe. Plasmid R1, the paradigm for type II plasmid partition, uses ATP-dependent polymerization of the actin-like ParM ATPase to push plasmids towards the poles. Plasmids (via their ParR/parC partition complexes) are inserted at the growing end of the filaments, which are polar, by associating with the barbed end of a ParM molecule. Filaments are capped by partition complexes and ATP subunits, while individual monomers within the filaments hydrolyze ATP to ADP. The other “pointed” end of the filament is proposed to be capped by association with an antiparallel ParM filament (not shown), which itself associates with another plasmid via ParR/parC complexes for bidirectional plasmid movement (111). Loss of the cap results in “catastrophe,” or rapid filament disassembly (not shown). (Right) Treadmilling. In type III partition systems such as that of pBtoxis, the tubulin-like TubZ GTPase polymerizes by addition of TubZ-GTP to the plus end and depolymerizes by loss of TubZ-GDP from the minus end, a behavior known as treadmilling. The plasmid (via its TubR/tubC partition complex) tracks with the minus end, so it is pulled from midcell to the cell pole. (B) Brownian ratchet partition systems rely on the ATP-dependent nonspecific DNA binding activity of the partition ATPase (ParA), which binds to the bacterial nucleoid. The plasmid (via the ParB/parS partition complex) attaches to ParA on the nucleoid and then stimulates ParA release from DNA by ATP hydrolysis or conformational change. Because ParA rebinding to the nucleoid is slow (40), a void of ParA is created on the bacterial chromosome, which serves as a barrier to motion so that the ParB/parS/plasmid complex moves towards the remaining ParA on the nucleoid. Further details and variations of this mechanism are described in the main text.