Abstract

Following improved accessibility to medical services, the phenomenon of polypharmacy in elderly patients with comorbidity has been increasing globally. Polypharmacy patients are prone to drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, and even the risk of death etc. Therefore, there is an urgent need to fully understand the current status and characteristics of drug use in elderly patients with chronic diseases, focusing on polypharmacy factors to ensure that medications for elderly patients are effective and safe. To collect and analyze the characteristics of the current drug use situation in elderly patients with chronic diseases in Chongqing and further explore the influencing factors for polypharmacy, providing references for formulating more effective and safe medication regimens for elderly patients. Most elderly patients affected with chronic diseases in Chongqing were willing to go to hospitals or pharmacies to buy medicines. However, they were not familiar with their disease conditions and drug-related adverse reactions and could not be regularly followed up or monitored. The number of diseases, medications, and adverse drug reactions increased with the increasing age of elderly patients. The problem of irrational use of drugs in elderly patients with chronic diseases was relatively prominent, especially the use of traditional Chinese medicines. The medication situation in elderly patients with chronic diseases was not optimistic, and the problem of polypharmacy was relatively prominent. Further large-scale studies are needed to provide a certain reference for improving the current status of drug use in elderly patients.

Keywords: chronic disease, elderly, polypharmacy

1. Introduction

Chronic diseases are the major public health concerns worldwide. Drugs are 1 of the important therapies for treating, preventing, and controlling chronic diseases. Over recent years, aging of the world’s population has accelerated. The survey results of the National Bureau of Statistics of China have reported that the proportion of the population > 65 years old reaches 13.5%[1] and is expected to exceed 27.9% in 2050,[2] much higher than the world average estimate of 16%.[3] As a result, the elderly have become the most prevalent group affected by chronic diseases, and they usually suffer from 2 or more chronic diseases. About 45.2% of elderly patients with chronic diseases in the United States developed comorbidities is,[4] compared with 43.7% in China.[5] As drug combination therapy is the main modality to control symptoms of chronic diseases and even facilitate secondary prevention, and elderly patients with comorbidity often take multiple drugs. Simultaneous use of 5 or more kinds of drugs is known as polypharmacy.

Following improved accessibility to medical services, the phenomenon of polypharmacy in elderly patients with comorbidity has been rapidly increasing globally. For example, the proportion of elderly patients with comorbidities who receive polypharmacy in the United States has increased from 24% to 39% over 10 years.[6] In this new era, the issue of medication safety was the first to bear the brunt. Previous studies have shown that 70% to 80% of polypharmacy patients are prone to drug accumulation, repeated medication, improper storage, and other behaviors,[7] all of which can increase drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, and even the risk of death,[8] thus significantly reducing the compliance and quality of life of elderly patients.[9]

Current clinical guidelines are based on the evidence proven in younger and healthier adult populations using a single disease model, while their application to older adults with multimorbidity yields a different risk-benefit prospect, which makes inappropriate medication use and polypharmacy inevitable.[10] Previous studies have reported the correlation between chronic diseases of the elderly and the functional status of daily life, but no medication analysis was performed.[11] In addition, existing studies have only conducted polypharmacy surveys and evaluations for the elderly aged > 80 years old or a certain type of chronic disease,[12,13] ignoring the discussion and analysis of the overall drug use in elderly patients with chronic diseases. Therefore, there is an urgent need to fully understand the current status and characteristics of drug use in elderly patients with chronic diseases, focusing on polypharmacy factors to ensure that medications for elderly patients are effective and safe.

In general, how to use drugs rationally to prevent and treat chronic diseases of the elderly, ensure the safety of patients’ medication, and improve their quality of life has become an urgent and important issue for the majority of medical staff. China launched the seventh national census in 2020, where people > 65 years old in Chongqing accounted for 17.08%, ranking second in the country.[14] There have been reports in the literature on the current status and influencing factors of medications used by the elderly in Chongqing care institutions.[15] The results showed that elderly care institutions became a gathering place for the elderly, with more medication and prominent safety issues. Still, there is no investigation and research on drug use among elderly patients with chronic diseases in Chongqing.

The present research for the first time carried out a multicenter study on the use of medications in elderly patients with chronic diseases in Chongqing, collecting medication status, medication needs and combination medication status of elderly patients, focusing on the influencing factors for polypharmacy, and providing certain measures for the rational use of medications for elderly patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

A multicenter cross-sectional survey of the current medication status of elderly patients with chronic diseases was carried out in Chongqing between January and October 2021. Inclusion criteria were the following: age ≥ 60 years old; subjects with at least 1 chronic disease; and subjects voluntarily participating in the study and signing an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria were subjects who could not understand the potential risks and benefits of the research, and could not complete the survey as required; the information collected in the questionnaire was incomplete or invalid; and patients with any more complex medical problems that may interfere with the research behavior or increase the risk, such as malignant tumors, blood diseases, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, viral hepatitis, etc.

2.2. Survey tools and contents

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The contents of the questionnaire included 2 parts: basic demographic information and disease treatment information of patients. Basic demographic information included the patient’s gender, age, height, weight, occupation before retirement, living situations, education background, marriage, education level, medical insurance type, economic status, attention from family members, and religious beliefs. Disease treatment information included all the chronic diseases or symptoms of patients, medications taken due to chronic diseases or symptoms (including drug name, usage and dosage, course of treatment, and adverse drug reactions), drug source, drug storage, medication habits, adverse drug events, and the type of service expected by the pharmacist. The principle of irrational medication evaluation was based on high-level evidence-based materials such as the medicine specification and disease diagnosis and treatment guidelines, including the indications, usage and dosage, administration course and contraindications specified in the medicine specification, as well as the classification and the principle of combined drug treatment recommended by the disease diagnosis and treatment guidelines. Family attention was evaluated by the PAGAR scale,[16] where the scoring standard was as follows: a total score of 10 points, 0 to 3 points indicated low family attention (severe family dysfunction), 4 to 96 points indicated medium family attention (moderate family dysfunction), 7 to 10 points indicated high family attention (good family functioning). The Cronbach α value of this scale was 0.86 in this study. See Appendix 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/N884, for the scoring scale. Through previous literature analysis[17–21] and expert consultation (3 geriatric clinical experts and 3 clinical pharmacy experts), a self-designed questionnaire (Appendix 1, Supplemental Digital Content, http://links.lww.com/MD/N884) was created; the content validity index (CVI) of the questionnaire was 0.95. The CVI for each item was 0.78 to 1.00. A pretest was conducted on 15 elderly patients with chronic diseases, and the Cronbach α value of the scale was 0.89. Before the survey was launched, a 3-d pre-survey was conducted to modify and improve the questionnaire information. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, outpatient or hospitalized elderly patients with chronic diseases were selected, and face-to-face interviews were conducted by using questionnaire surveys. Each patient’s contact information was recorded for detailed investigation when there were questions about the follow-up data verification to ensure the quality of the questionnaire data.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for the normality test of measurement data when the sample size was ≥ 50, and Shapiro–Wilk test was used when the sample size was <50. Counting data were expressed in frequency (percentage). In the correlation analysis, the measurement data conforming to normal distribution were analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis, and the measurement data with non-normal distribution were analyzed with Spearman correlation analysis. The comparison of ordinal categorical variables between the 2 groups was conducted with the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Logistic regression was used for univariate and multivariate regression analysis with polypharmacy as the outcome. SPSS 22.0 was used to conduct the above-listed analyses.

3. Results

3.1. General information of patients

A total of 440 questionnaires were collected in this study, of which 411 were valid questionnaires, with an effective response rate of 93.41%. The age of the patients was 60 to 79 years old (83.46%), and the proportion of male and female patients was basically the same. Workers and farmers (71.05%) were the main occupations before retirement. The education background was generally low (54.26% with primary school education). Most patients were currently retired at home (86.37%), while only 55.72% of subjects had a high degree of family attention; 88.56% of the subjects were married, and low economic status was generally low, with <12,000 yuan/yr (49.39%), or 12,000 to 36,000 yuan/yr (29.68%); the proportion of city and rural residents was basically the same; and the vast majority of patients (95.87%) had no religious beliefs. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

General information of patients.

| Patient information | Number of patients | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||

| 60 to 69 | 165 | 40.15 |

| 70 to 79 | 178 | 43.31 |

| ≥80 | 68 | 16.54 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 206 | 50.12 |

| Female | 205 | 49.88 |

| Pre-retirement occupation | ||

| Worker | 84 | 20.44 |

| Farmer | 208 | 50.61 |

| Administrative worker | 30 | 7.30 |

| Service industry | 24 | 5.84 |

| Intellectuals | 23 | 5.60 |

| others | 42 | 10.21 |

| Fully retire at home | ||

| Yes | 355 | 86.37 |

| No | 56 | 13.63 |

| Living situation | ||

| Living with children | 211 | 51.34 |

| Living alone and other situations | 200 | 48.66 |

| Attention from family members | ||

| High | 229 | 55.72 |

| Medium | 143 | 34.79 |

| Low | 39 | 9.49 |

| Education background | ||

| Illiteracy | 29 | 7.06 |

| Primary school | 223 | 54.26 |

| Junior high school | 102 | 24.82 |

| High school and above | 57 | 13.86 |

| Marital status | ||

| With partner | 364 | 88.56 |

| No partner | 47 | 11.44 |

| Type of household registration | ||

| City | 194 | 47.20 |

| Rural area | 217 | 52.80 |

| Economic status | ||

| <12,000 yuan/yr | 203 | 49.39 |

| 12,000 to 36,000 yuan/yr | 122 | 29.68 |

| >36,000 yuan/yr | 86 | 20.93 |

| Medical insurance type | ||

| Urban residents’ medical insurance | 102 | 24.82 |

| Urban employee medical insurance | 136 | 33.09 |

| Rural cooperative Medical | 173 | 42.09 |

| Religious belief | ||

| Yes | 17 | 4.13 |

| No | 394 | 95.87 |

3.2. Correlation between the number of medications, the number of patients, and the number of disease cases

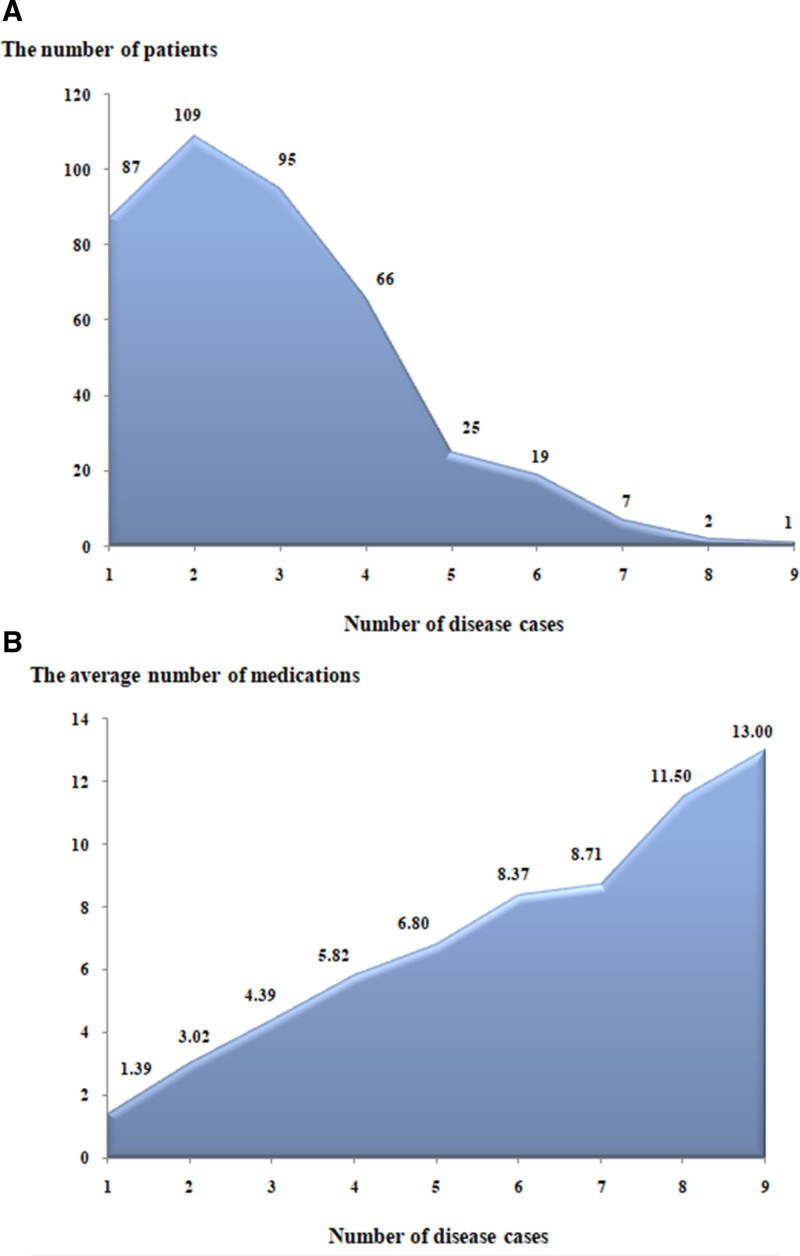

The total number of diseases (the number of cases) for the same patient was at least 1, and the maximum was 9 diseases. The largest proportion, i.e., 109 subjects (26.52%), made up patients with 2 simultaneous diseases. A total of 324 subjects had comorbidity, with a relatively high incidence of 78.83%. The study results showed that with the increase in the number of disease cases, the number of patients gradually decreased, but the average number of medications (species) gradually increased. The number of disease cases was positively correlated with the number of medications, and the number of disease cases was negatively correlated with the number of patients. The results are indicated in Figure 1A and B and Table 2.

Figure 1.

(A) The correlation between the number of disease cases and the number of patients. (B) The correlation between the number of disease cases and the average number of medications.

Table 2.

Analysis of the correlation between the number of medications, the number of patients, and the number of cases.

| Variables | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| Number of medications | 0.751 | <.001* |

| Number of patients | −0.933 | <.001 |

The use of Spearman correlation analysis

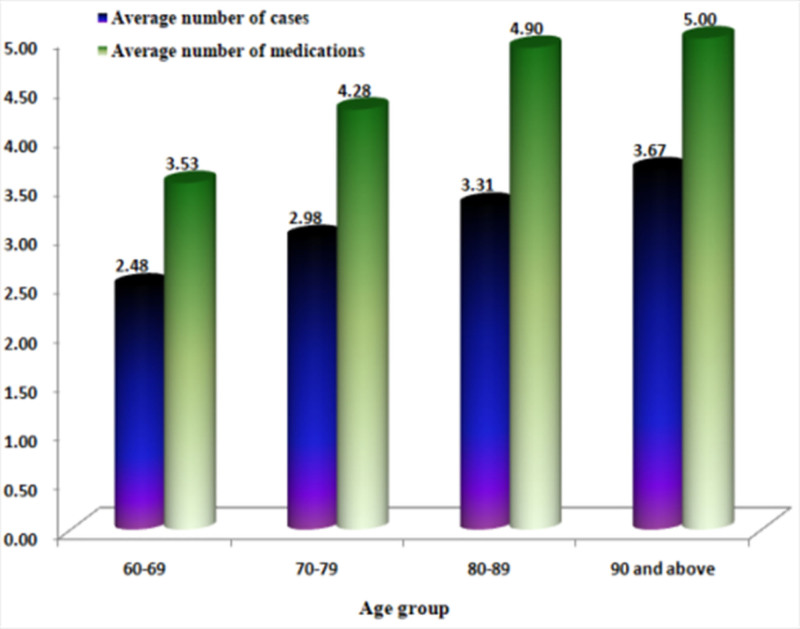

The patients were divided into 4 groups by age: 60 to 69 years old, 70 to 79 years old, 80 to 89 years old, and over 90 years old. With the increase of age, the average number of disease cases and the average number of medications (species) also gradually increased (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in the average number of cases and the number of medications in different age groups.

There were 19 kinds of diseases with more than 10 kinds of medications. The top 3 diseases by the number of medications were coronary heart disease, hypertension, and type-2 diabetes. The top 3 diseases by the number of patients were hypertension, type-2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease. Excluding patients without taking drugs for disease treatment, the top 5 diseases with corrected patients number were hypertension, type-2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, chronic gastritis, and cerebral infarction, and the top 5 diseases with corrected average medications per person were coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and peptic ulcer, type-2 diabetes, and hypertension (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ranking of the number of patients and the number of medications.

| No. | Disease name | Number of medication (species) | Number of patients | Average number of medications per patient (species) | Number of untreated patients | Corrected number of patients | Corrected average number of medications per patient (species) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coronary artery disease | 396 | 151 | 2.62 | 11 | 140 | 2.83 |

| 2 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 76 | 56 | 1.36 | 21 | 35 | 2.17 |

| 3 | Peptic ulcer | 22 | 16 | 1.38 | 4 | 12 | 1.83 |

| 4 | Type-2 diabetes | 333 | 209 | 1.59 | 20 | 189 | 1.76 |

| 5 | Hypertension | 335 | 255 | 1.31 | 52 | 203 | 1.65 |

| 6 | Asthma | 13 | 9 | 1.44 | 1 | 8 | 1.63 |

| 7 | Pain | 47 | 37 | 1.27 | 7 | 30 | 1.57 |

| 8 | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 16 | 16 | 1.00 | 5 | 11 | 1.45 |

| 9 | Osteoporosis | 42 | 37 | 1.14 | 8 | 29 | 1.45 |

| 10 | Constipate | 11 | 13 | 0.85 | 5 | 8 | 1.38 |

| 11 | Heart failure | 13 | 11 | 1.18 | 0 | 11 | 1.18 |

| 12 | Hypokalemia | 17 | 16 | 1.06 | 0 | 16 | 1.06 |

| 13 | Diabetic neuropathy | 11 | 11 | 1.00 | 0 | 11 | 1.00 |

| 14 | Dyslipidemia | 11 | 11 | 1.00 | 0 | 11 | 1.00 |

| 15 | Tumor | 27 | 28 | 0.96 | 0 | 28 | 0.96 |

| 16 | Cerebral infarction | 40 | 46 | 0.87 | 4 | 42 | 0.95 |

| 17 | Hepatitis B | 15 | 18 | 0.83 | 2 | 16 | 0.94 |

| 18 | Chronic gastritis | 68 | 73 | 0.93 | 0 | 73 | 0.93 |

| 19 | Chronic renal insufficiency | 14 | 18 | 0.78 | 0 | 18 | 0.78 |

3.3. Medication habits and disease treatment

A small number of patients were familiar with their disease status (21.90%), and only 28.71% of patients had regular follow-up visits, while 20.68% regularly monitored blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids, and other related indicators. The medicines used by patients were mainly purchased from pharmacies (99.03%) and were prescribed by doctors (90.27%). Additionally, 74.21% of patients paid attention to the correct preservation of medicines. About 50% of patients preserved oral and external medicines separately, paid attention to the expiry date of medicines, and regularly organized family medicine boxes. About 80% of patients were concerned about or were familiar with the correct usage and dosage of drugs, while 73.48% of patients did not know the adverse reactions of the drugs they were currently using. If there was any discomfort during the medication, patients were more likely to go to the hospital (52.31%) or stop the medication by themselves (39.90%). The patients hoped that the pharmacist could provide information related to lifestyle education (52.31%), usage and dosage (45.01%), and adverse drug reactions (39.66%). The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Medication habits and treatment of disease of patients.

| Contents of item | Number of patients | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of their own disease status | ||

| Familiar | 90 | 21.90 |

| Basically know | 260 | 63.26 |

| Did not know | 61 | 14.84 |

| Visiting a doctor or follow-up regularly | ||

| Yes | 118 | 28.71 |

| Occasionally | 182 | 44.29 |

| No | 111 | 27.00 |

| Regularly monitoring blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipid indicators, and other related indicators | ||

| Yes | 85 | 20.68 |

| Occasionally | 223 | 54.26 |

| No | 103 | 25.06 |

| Drug source (multiple choice for this item) | ||

| Doctor’s prescription | 371 | 90.27 |

| Pharmacy purchase | 407 | 99.03 |

| Advertising | 4 | 0.97 |

| Introduced by friends | 3 | 0.73 |

| Gifts from children or relatives | 8 | 1.95 |

| Others | 5 | 1.22 |

| Medicine preservation | ||

| Yes | 305 | 74.21 |

| No | 106 | 25.79 |

| Separate storage of oral drugs and external drugs | ||

| Yes | 237 | 57.66 |

| No | 174 | 42.34 |

| Consideration of the expiry date of the drug | ||

| Yes | 207 | 50.36 |

| No | 204 | 49.64 |

| Regularly organizing the family medicine box | ||

| Yes | 166 | 40.39 |

| No | 245 | 59.61 |

| Concerns about the correct use of drugs | ||

| Yes | 331 | 80.54 |

| No | 80 | 19.46 |

| Familiarity with the correct dosage of the medicine | ||

| Yes | 330 | 80.29 |

| No | 81 | 19.71 |

| Familiarity with the main adverse reactions of the medications used | ||

| Yes | 109 | 26.52 |

| No | 302 | 73.48 |

| What will you do if you feel unwell during the medication? | ||

| Self-discontinuation | 164 | 39.90 |

| Continue medication | 32 | 7.79 |

| Go to the hospital | 215 | 52.31 |

| What kind of services do you want pharmacists to provide? (multiple choices for this item) | ||

| formulation or adjustment of drug treatment plan | 122 | 29.68 |

| Usage and dosage | 185 | 45.01 |

| Contraindications | 75 | 18.25 |

| Medication or lifestyle education | 215 | 52.31 |

| Side effects of drugs | 163 | 39.66 |

| Medicine cost | 12 | 2.92 |

| Humanistic care | 1 | 0.24 |

| Drug onset time | 1 | 0.24 |

3.4. Prevalence and gender

The top 20 diseases based on prevalence rates were counted, revealing that the top 3 diseases were hypertension (62.04%), type-2 diabetes (50.85%), and coronary heart disease (36.74%). There were slightly more female patients than males. More female patients developed dyslipidemia, osteoporosis, and hepatitis B and more male patients experienced chronic renal insufficiency. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of the overall prevalence and gender.

| No | Name of the disease | Total number of patients | Proportion to the total number of people (%) | Number of males | Proportion to the total number of patients with this type of disease (%) | Number of females | Proportion to the total number of patients with this type of disease (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hypertension | 255 | 62.04 | 120 | 47.06 | 135 | 52.94 |

| 2 | Type-2 diabetes | 209 | 50.85 | 97 | 46.41 | 112 | 53.59 |

| 3 | Coronary heart disease | 151 | 36.74 | 69 | 45.70 | 82 | 54.30 |

| 4 | Chronic gastritis | 73 | 17.76 | 25 | 34.25 | 48 | 65.75 |

| 5 | COPD | 56 | 13.63 | 34 | 60.71 | 22 | 39.29 |

| 6 | Cerebral infarction | 46 | 11.19 | 19 | 41.30 | 27 | 58.70 |

| 7 | Pain | 37 | 9.00 | 17 | 45.95 | 20 | 54.05 |

| 8 | Osteoporosis | 37 | 9.00 | 6 | 16.22 | 31 | 83.78 |

| 9 | Tumor | 28 | 6.81 | 11 | 39.29 | 17 | 60.71 |

| 10 | Insomnia | 28 | 6.81 | 11 | 39.29 | 17 | 60.71 |

| 11 | Hepatitis B | 18 | 4.38 | 5 | 27.78 | 13 | 72.22 |

| 12 | Chronic renal insufficiency | 18 | 4.38 | 13 | 72.22 | 5 | 27.78 |

| 13 | Peptic ulcer | 16 | 3.89 | 6 | 37.50 | 10 | 62.50 |

| 14 | Hypokalemia | 16 | 3.89 | 6 | 37.50 | 10 | 62.50 |

| 15 | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 16 | 3.89 | 16 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 16 | Constipation | 13 | 3.16 | 8 | 61.54 | 5 | 38.46 |

| 17 | Diabetic neuropathy | 11 | 1.04 | 5 | 45.45 | 6 | 54.55 |

| 18 | Heart failure | 11 | 1.04 | 5 | 45.45 | 6 | 54.55 |

| 19 | Dyslipidemia | 11 | 1.04 | 1 | 9.09 | 10 | 90.91 |

| 20 | Asthma | 9 | 0.85 | 5 | 55.56 | 4 | 44.44 |

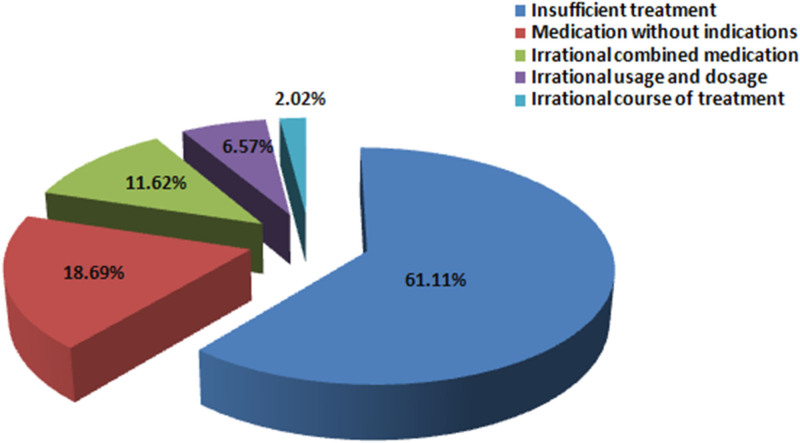

3.5. Irrational use of drugs

Among the 411 cases, 171 patients reported irrational use of drugs (41.61%). There were 198 cases of irrational medications, including 121 cases of (61.11%) insufficient treatment (not treated with medication), 37 cases (18.69%) of medication without indications, 23 cases (11.62%) of irrational combined medication, 13 cases (6.57%) of irrational usage and dosage, and 4 cases (2.02%) of irrational course of treatment (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Overall situation of irrational use of drugs.

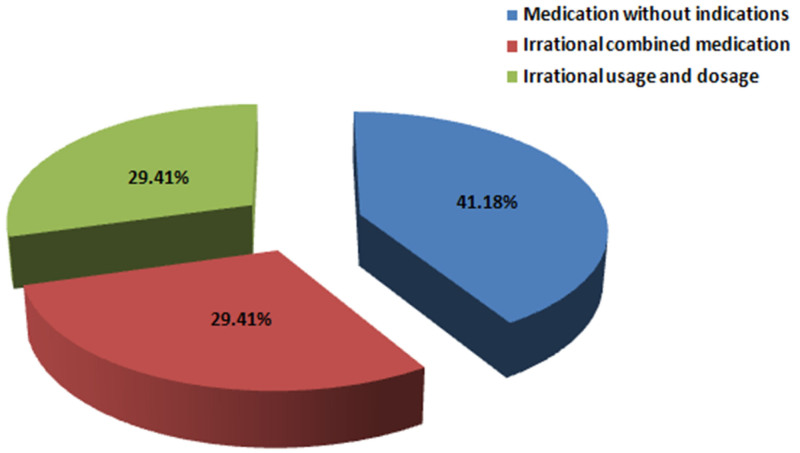

A total of 120 cases used traditional Chinese medicines (29.20%). The total number of traditional Chinese medicines used was 181, with an average of 1.51 species per person. There were 34 cases (28.33%) of irrational use of traditional Chinese medicines, including 14 cases (41.18%) of medication without indications, 10 cases (29.41%) of combined medication, and irrational usage and dosage (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Irrational uses of traditional Chinese medicines.

3.6. Analysis of the incidence and influencing factors for polypharmacy

Four hundred eleven cases were initially enrolled for this study, and 12 cases with no drug treatment were excluded. The total number of corrected subjects was 399 cases. Among them, 159 patients took more than 5 kinds of drugs, and the overall incidence of polypharmacy was 39.85%. The statistical results showed that “a number of cases” and “visiting a doctor or regular follow-up” were the main factors that led to polypharmacy, i.e., the more comorbid diseases and the failure to adhere to regular follow-ups were more likely to lead to the increased number of medications used by patients (Table 6).

Table 6.

Analysis of the incidence of polypharmacy under different influencing factors.

| Influencing factors | Number of patients | Corrected number of patients | Number of patients with polypharmacy | Proportion of polypharmacy (%) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||||||

| Gender | Male | 206 | 197 | 81 | 41.12 | 1.110 (0.743, 1.658) | .610 | ||

| Female | 205 | 202 | 78 | 38.61 | Ref | ||||

| Age | 60 to 69 | 165 | 160 | 50 | 31.25 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 70 to 79 | 178 | 174 | 76 | 43.68 | 1.706 (1.089,2.673) | .020 | 1.200 (0.623, 2.309) | .586 | |

| ≥80 | 68 | 65 | 33 | 50.77 | 2.269 (1.258,4.093) | .007 | 1.105 (0.447, 2.735) | .828 | |

| Occupation | Worker | 84 | 84 | 46 | 54.76 | 1.000 (0.475, 2.105) | 1.000 | 1.044 (0.379, 2.872) | .934 |

| Famer | 208 | 201 | 58 | 28.86 | 0.335 (0.170, 0.661) | .002 | 0.590 (0.185, 1.879) | .372 | |

| Administrative worker | 30 | 28 | 9 | 32.14 | 0.391 (0.144, 1.063) | .066 | 0.528 (0.134, 2.079) | .361 | |

| Service industry | 24 | 24 | 11 | 45.83 | 0.699 (0.255, 1.913) | .486 | 0.698 (0.167, 2.921) | .622 | |

| Intellectuals | 23 | 20 | 12 | 60.00 | 1.239 (0.420, 3.654) | .698 | 0.289 (0.057, 1.457) | .133 | |

| Others | 42 | 42 | 23 | 54.76 | Ref | Ref | |||

| Fully retire at home | Yes | 355 | 343 | 138 | 40.23 | 1.122 (0.627,2.009) | .699 | ||

| No | 56 | 56 | 21 | 37.50 | Ref | ||||

| Living situation | Living with children | 211 | 205 | 69 | 33.66 | 0.586 (0.391, 0.878) | .010 | 0.547 (0.295, 1.013) | .055 |

| Living alone and other situations | 200 | 194 | 89 | 45.88 | Ref | Ref | |||

| Attention from family members | High | 229 | 224 | 82 | 36.61 | 0.611 (0.299, 1.252) | .178 | ||

| Medium | 143 | 140 | 60 | 42.86 | 0.794 (0.378, 1.669) | .543 | |||

| Low | 39 | 35 | 17 | 48.57 | Ref | ||||

| Education background | Illiteracy | 29 | 29 | 10 | 34.48 | 0.436 (0.171, 1.112) | .082 | 0.382 (0.090, 1.619) | .192 |

| Primary school | 223 | 219 | 66 | 30.14 | 0.357 (0.193, 0.659) | .001 | 0.362 (0.128, 1.023) | .055 | |

| Junior high school | 102 | 98 | 53 | 54.08 | 1.016 (0.519, 1.988) | .964 | 0.676 (0.246, 1.861) | .449 | |

| High school and above | 57 | 53 | 29 | 54.72 | Ref | Ref | |||

| Marital status | With partner | 364 | 353 | 137 | 38.81 | 0.692 (0.373,1.282) | .242 | ||

| No partner | 47 | 46 | 22 | 47.83 | Ref | ||||

| Household registration | City | 194 | 189 | 95 | 50.26 | 2.207 (1.467,3.321) | <.001 | 1.104 (0.367, 3.325) | .860 |

| Rural area | 217 | 210 | 65 | 30.95 | Ref | Ref | |||

| Economic status | <12,000 yuan/yr | 203 | 197 | 64 | 32.49 | 0.369 (0.218, 0.624) | <.001 | 0.878 (0.295, 2.613) | .815 |

| 12,000 to 36,000 yuan/yr | 122 | 119 | 48 | 40.34 | 0.518 (0.293, 0.914) | .023 | 0.413 (0.165, 1.033) | .059 | |

| >36,000 yuan/yr | 86 | 83 | 47 | 56.63 | Ref | Ref | |||

| Medical insurance type | Urban residents’ medical insurance | 102 | 97 | 33 | 34.02 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Urban employee medical insurance | 136 | 133 | 71 | 53.38 | 2.221 (1.293, 3.814) | .004 | 1.387 (0.587, 3.273) | .456 | |

| Rural cooperative medical | 173 | 169 | 55 | 32.54 | 0.936 (0.551, 1.588) | .805 | 1.140 (0.439, 2.958) | .788 | |

| Religious belief | Yes | 17 | 15 | 4 | 26.67 | 0.537 (0.168, 1.718) | .295 | ||

| No | 394 | 384 | 155 | 40.36 | Ref | ||||

| Knowing of own disease status | Familiar | 90 | 88 | 40 | 45.45 | 1.625 (0.821, 3.218) | .164 | ||

| Basically know | 260 | 252 | 100 | 39.68 | 1.262 (0.696, 2.288) | .444 | |||

| Did not know | 61 | 59 | 30 | 50.85 | Ref | ||||

| Visiting a doctor or follow-up regularly | Yes | 118 | 115 | 65 | 56.52 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Occasionally | 182 | 178 | 61 | 34.27 | 0.401 (0.248, 0.649) | <.001 | 0.433 (0.205, 0.917) | .029 | |

| No | 111 | 106 | 33 | 31.13 | 0.348 (0.200, 0.604) | <.001 | 0.377 (0.150, 0.944) | .037 | |

| Regularly monitor disease indicators | Yes | 85 | 83 | 44 | 53.01 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Occasionally | 223 | 217 | 84 | 38.71 | 0.560 (0.336, 0.933) | .026 | 1.424 (0.642, 3.157) | .385 | |

| No | 103 | 99 | 31 | 31.31 | 0.404 (0.221, 0.740) | .003 | 0.846 (0.309, 2.314) | .745 | |

| Number of cases | 411 | 399 | 159 | 39.85 | 4.191 (3.158, 5.562) | <.001 | 4.453 (3.227, 6.147) | <.001 | |

3.7. Adverse drug reactions

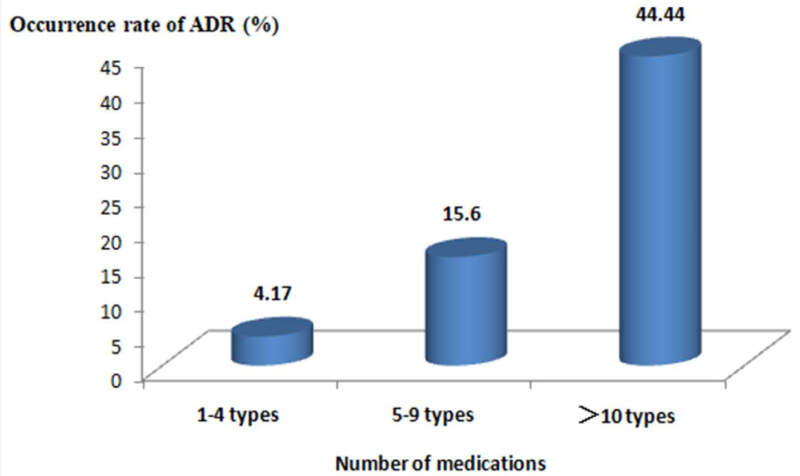

The incidence of adverse reactions in patients taking 1 to 4 drugs was 4.17%; the incidence of adverse reactions in patients taking 5 to 9 drugs was 15.60%, and the incidence of adverse reactions in patients taking more than 10 drugs was 44.44%. The statistical results showed that with the increase in the number of drugs, the incidence of adverse drug reactions increased, and the incidence of adverse reactions in patients with more than 5 kinds of drugs reached 60.04%, as shown in Figure 5. The incidence of ADR in patients receiving ≥ 5 kinds of drugs was higher than that of patients receiving 1 to 4 kinds of drugs. The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test showed a difference in the number of medications between the 2 groups in relation to whether there was ADR (χ2 = 28.459, P < .001, α = 0.05), as shown in Table 7.

Figure 5.

Changes in the number of drugs and the incidence of adverse reactions.

Table 7.

Analysis of the correlation between the number of medications and adverse drug reactions.

| Number of medications | Occurrence of ADR | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| 1 to 4 types | 10 (25.00%) | 230 (64.07%) | 28.459 | <.001 |

| 5 to 9 types | 22 (55.00%) | 119 (33.15%) | ||

| >10 types | 8 (20.00%) | 10 (2.79%) | ||

4. Discussion

The elderly patients included in the present survey were mainly 60 to 80 years old. Most of the older patients were retired, married, had low educational backgrounds (primarily elementary and junior high schools), and their economic income was in the middle and low range, which was basically in line with the current living conditions of elderly patients in Southwest China. The overall statistical results showed that increased age in elderly patients was associated with the increases in the number of diseases, the number of medications, and adverse drug reactions. Consequently, it is necessary to pay special attention to monitoring, promoting effective, safe and economical medication for the elderly subjects.

The present study results showed that more than 90% of patients chose drugs prescribed in formal ways, such as by hospitals or pharmacies. Still, there was still a small number of patients who obtained drugs in other ways. Considering that elderly patients had a strong awareness of safe drug purchase, which is basically consistent with the results reported in the literature in China,[22] this may be related to multiple factors such as the population’s educational background, medical insurance type, and economic levels. In addition, only about 20% of elderly patients were familiar with their disease status, and <30% of patients could be regularly followed up or monitored. However, most patients were not aware of adverse drug reactions. Therefore, drug safety issues in elderly patients with chronic diseases should be paid greater attention.[23] It was hoped that pharmacists could provide multiple pharmaceutical services such as medication education, usage, and dosage, as well as information on adverse reactions. This suggested that elderly patients were more and more care about safe medication. Yet, they knew very little about adverse drug reactions, so pharmacists were urgently needed to provide them with comprehensive safe medication guidance.

The increase in age was also associated with the increase in the number of disease cases and the number of medications. Among the participants included in the present study, 324 patients had 2 or more simultaneous diseases, the incidence of comorbidity was 78.83%, 159 patients took 5 kinds of drugs, and the incidence of polypharmacy was 39.85%. An earlier study showed that 29% of the elderly used at least 5 drugs.[24] However, over recent years, this proportion has increased to 44%[25] and 49.5%.[26] This study showed that the incidence of polypharmacy in elderly patients was close to the level reported in the recent literature, suggesting that the increase in the aging population might be associated with serious polypharmacy. This, in turn, calls for greater efforts to be paid to effectively manage polypharmacy in elderly patients with chronic diseases.

Previous literature studies have shown that factors such as the number of disease cases,[27,28] age,[29,30] and educational level[30] may lead to polypharmacy in elderly patients. However, our results showed that only “the number of disease cases” and “failure to participate in regular follow-up” were significant influencing factors for polypharmacy. Thus, the comorbidity may cause polypharmacy, which is consistent with existing literature.[27,28] To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study that found how “failure to participate in the regular follow-up” might lead to polypharmacy, which should be further investigated. Therefore, elderly patients with multiple chronic diseases were very likely to have polypharmacy problems, and regular follow-ups were required for such patients, as they might help reduce the number of medications.

The present study showed that the incidence of adverse drug reactions also significantly increased with the increase in the number of medications. The incidence of adverse reactions in patients with more than 5 types of medications exceeded 60%, which can easily lead to the occurrence of the prescription cascade that is basically consistent with the existing literature reports.[31] Therefore, it was recommended to educate the patients, actively promote the knowledge on adverse reactions, and strengthen drug safety monitoring.[29]

In this study, 198 (48.18%) patients had irrational medication problems, among whom 121 (29.44%) patients had no drug treatment (insufficient treatment) for irrational medication, which was basically consistent with the results reported in the existing studies.[32,33] The reasons for insufficient treatment in the previous literature may be related to the nature of medical institutions and the doctors’ ability to reach patients,[32] while our research was carried out in Southwest China that had relatively backward economic levels, which might be related to low income of the included population, low educational level, family attention and other factors leading to the corresponding decrease in the ability to treat diseases. This, in turn, suggests that in the future management of chronic diseases in the elderly, special attention should be paid to the problem of insufficient treatment or missed treatment.

A total of 120 cases (29.20%) used traditional Chinese medicines, with an average of 1.51 kinds per person. The current drug-related problems of the elderly include polypharmacy, irrational drug use, and complementary and alternative medicine (traditional Chinese medicine, vitamins, etc),[26] while a significant correlation was reported between complementary drugs and polypharmacy.[34,35] A systematic review of 22 studies (including 18,399 participants) in the United States and European countries showed that the proportion of adjuvant medications in elderly patients was very high (5.3%–88.3%).[36,37] Traditional Chinese medicine is an important part of treatment regimen in China. Therefore, the elderly in China were more inclined to choose traditional Chinese medicine as adjuvant therapy.[32,38] However, our results revealed that the problem of irrational use of traditional Chinese medicines was relatively prominent, including medication without indications, combined medication, and irrational usage and dosage, which suggested that more attention should be paid to the rationality of the use of traditional Chinese medicines among the elderly.

This study had certain limitations. First, the time for conducting this experiment was short, and the sample size was small. Second, the number of medications and adverse reactions were mainly collected, but the information on drug costs was not collected, and there was a lack of statistical analysis of pharmacoeconomics. Thirdly, our results revealed that the problem of irrational use of drugs was relatively prominent, and patients showed the need for information on drug use and pharmaceutical services. However, pharmacists did not provide intervention measures, which should be addressed in future work. Fourthly, the subjects included in this study were mainly between 60 and 80 years old, and the proportion of patients > 80 years old was only accounted for 16%. As limited data were collected for the super-old age group, future studies should expand the sample size of this population.

5. Conclusion

A survey of medications for elderly patients with chronic diseases in Chongqing revealed that with the increase in age, the number of disease cases, the number of medications, and adverse drug reactions increased. Moreover, the problem of irrational medication became more prominent, especially the use of traditional Chinese medicines, which should be considered more thoroughly. However, the study time was short, the sample size was small, and the drug use data of the super-elderly was relatively limited. Therefore, future multicenter large-sample long-term studies are warranted.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Xiaolei Hu.

Data curation: Xiaolei Hu, Min Tang, Jie Feng, Weiqiong Chen, Ling Ding, Jia Liu.

Formal analysis: Xiaolei Hu, Ling Ding, Mengying Liu, Xiaofei Liu, Jia Liu.

Investigation: Guangcan Li, Jun Zhou.

Methodology: Xiaolei Hu, Mo Cheng.

Project administration: Xiaolei Hu, Min Tang, Weiqiong Chen.

Resources: Jie Feng.

Software: Guangcan Li, Xiaofei Liu.

Supervision: Min Tang, Weiqiong Chen, Mengying Liu.

Validation: Jie Feng, Mo Cheng, Jun Zhou.

Visualization: Mo Cheng.

Writing – original draft: Xiaolei Hu, Xiaofei Liu.

Writing – review & editing: Xiaolei Hu.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviation:

- CVI

- content validity index.

This work was supported by the Chongqing Science and Health Joint medical research Project: establishment of multidrug evaluation system for chronic diseases in the elderly based on PCNE system Current and Empirical Research (2022MSXM057).

The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Army Medical University (KY2021025), and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The author(s) of this work have nothing to disclose.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Hu X, Tang M, Feng J, Chen W, Li G, Ding L, Cheng M, Liu M, Zhou J, Liu X, Liu J. Characteristics of the current situation of drug use in elderly patients with chronic diseases in Chongqing: A cross-sectional survey. Medicine 2024;103:46(e40470).

Contributor Information

Min Tang, Email: tangmin1007@163.com.

Jie Feng, Email: nanbufc@hotmail.com.

Weiqiong Chen, Email: 335827466@qq.com.

Guangcan Li, Email: 179368757@qq.com.

Ling Ding, Email: 626654306@qq.com.

Mo Cheng, Email: 184196499@qq.com.

Mengying Liu, Email: 719654934@qq.com.

Jun Zhou, Email: 287360402@qq.com.

Xiaofei Liu, Email: 719654934@qq.com.

Jia Liu, Email: 719654934@qq.com.

References

- [1].National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. China Statistical Yearbook, 2020. China Statistics Press. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [2].China Development Research Foundation. China development report, 2020: development trends and policies of China’s population aging. 2020. https://www.cdrf.org.cn/llhyjcg/5787.htm. Accessed November 6, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- [3].The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019. 2019. http://health.people.com.cn/n1/2019/0619/c14739-31168811.html. Accessed November 6, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ornstein SM, Nietert PJ, Jenkins RG, Litvin CB. The prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity in primary care practice: a PPRNet report. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yan W, Lu Y, Zhang R. Multimorbidity status of the elderly in China-research based on CHARLS data. Chin J Disease Control Prev. 2019;23:426–30. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1818–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shrestha S, Poudel RS, Pradhan S, Adhikari A, Giri A, Poudel A. Factors predicting home medication management practices among chronically ill older population of selected districts of Nepal. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Leelakanok N, Holcombe AL, Lund BC, Gu X, Schweizer ML. Association between polypharmacy and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57:729–38.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pérez-Jover V, Mira JJ, Carratala-Munuera C, et al. Inappropriate use of medication by elderly, polymedicated, or multipathological patients with chronic diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mangin D, Bahat G, Golomb BA, et al. International Group for Reducing Inappropriate Medication Use & Polypharmacy (IGRIMUP): position statement and 10 recommendations for action. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:575–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Maresova P, Javanmardi E, Barakovic S, et al. Consequences of chronic diseases and other limitations associated with old age – a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lai X, Zhu H, Huo X, Li Z. Polypharmacy in the oldest old (≥80 years of age) patients in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sutaria A, Liu L, Ahmed Z. Multiple medication (polypharmacy) and chronic kidney disease in patients aged 60 and older: a pharmacoepidemiologic perspective. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;10:242–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].de Souza FI, Di Ferreira RB, Labres D, Elias R, de Sousa AP, Pereira RE. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in students of the public schools in Goiânia-GO. Acta Ortop Bras. 2013;21:223–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Peng YH, Xie LL, Chen JJ. Status quo and influencing factors of drug use for the elderly in nursing institutions in Chongqing. Chin Nurs Res. 2019;33:3836–42. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Smilkstein G. The cycle of family function: a conceptual model for family medicine. J Fam Pract. 1980;11:223–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Luo L, Zhang M, Chen HF, et al. Validity, reliability, and application of the electronic version of a chronic kidney disease patient awareness questionnaire: a pilot study. Postgrad Med. 2021;133:48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kitamura S, Igarashi A, Yamauchi Y, Senjyu H, Horie T, Yamamoto-Mitani N. Self-management activities of older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by types of healthcare services utilised: a cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int J Older People Nurs. 2020;15:e12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Postma SAE, van Boven K, Ten Napel H, et al. The development of an ICF-based questionnaire for patients with chronic conditions in primary care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;103:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kido-Nakahara M, Nakahara T, Furusyo N, et al. Pruritus in chronic liver disease: a questionnaire survey on 216 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:220–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Harley C, Pini S, Kenyon L, Daffu-O’Reilly A, Velikova G. Evaluating the experiences and support needs of people living with chronic cancer: development and initial validation of the Chronic Cancer Experiences Questionnaire (CCEQ). BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9:e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yuan Y, Li YL. Drug use of elderly patients in southern Sichuan. Chin J Gerontol. 2019;39:203–6. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee EH, Park JO, Cho JP, Lee CA. Prioritising risk factors for prescription drug overdose among older adults in South Korea: a multi-method study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:2867–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Morin L, Johnell K, Laroche ML, Fastbom J, Wastesson JW. The epidemiology of polypharmacy in older adults: register-based prospective cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chang CT, Ang JY, Islam MA, Chan HK, Cheah WK, Gan SH. Prevalence of drug-related problems and complementary and alternative medicine use in Malaysia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 37,249 older adults. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Toback M, Clark N. Strategies to improve self-management in heart failure patients. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53:105–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Levin PA, Wei W, Zhou S, Xie L, Baser O. Outcomes and treatment patterns of adding a third agent to 2 OADs in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20:501–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kratz T, Diefenbacher A. Psychopharmacological treatment in older people: avoiding drug interactions and polypharmacy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116:508–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A, Malakouti SK, Bazargan M, Assari S. Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Parameswaran Nair N, Chalmers L, Peterson GM, Bereznicki BJ, Castelino RL, Bereznicki LR. Hospitalization in older patients due to adverse drug reactions -the need for a prediction tool. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yang J, Meng L, Liu Y, et al. Drug-related problems among community-dwelling older adults in mainland China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Tulner LR, van Campen JP, Frankfort SV, et al. Changes in under-treatment after comprehensive geriatric assessment: an observational study. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:831–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lim LM, McStea M, Chung WW, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and health outcomes associated with polypharmacy among urban community-dwelling older adults in multi-ethnic Malaysia. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gahche JJ, Bailey RL, Potischman N, Dwyer JT. Dietary supplement use was very high among older adults in the United States in 2011-2014. J Nutr. 2017;147:1968–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Agbabiaka TB, Wider B, Watson LK, Goodman C. Concurrent use of prescription drugs and herbal medicinal products in older adults: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34:891–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, Wardle J, Adams J. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xiong X, Wang P, Zhang Y, Li X. Effects of traditional Chinese patent medicine on essential hypertension: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]