Abstract

Highly regulated cardiomyocyte Ca2+ fluxes drive heart contractions. Recent findings from multiple organisms demonstrate that the specific Ca2+ transport mechanism known as store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is essential in cardiomyocytes for proper heart function, and SOCE dysregulation results in cardiomyopathy. Mechanisms that regulate SOCE in cardiomyocytes are poorly understood. Here we tested the role of cytoskeletal septin proteins in cardiomyocyte SOCE regulation. Septins are essential SOCE modulators in other cell types, but septin functions in cardiomyocytes are nearly completely unexplored. We show using targeted genetics and intravital imaging of heart contractility in Drosophila that cardiomyocyte-specific depletion of septins 1, 2, and 4 results in heart dilation that phenocopies the effects of SOCE suppression. Heart dilation caused by septin 2 depletion was suppressed by SOCE upregulation, supporting the hypothesis that septin 2 is required in cardiomyocytes for sufficient SOCE function. A major function of SOCE is to support SERCA-dependent sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (S/ER) Ca2+ stores, and augmenting S/ER store filling by SERCA overexpression also suppressed the septin 2 phenotype. We also ruled out several potential SOCE-independent septin functions, as septin 2 phenotypes were not due to septin function during development and septin 2 was not required for z-disk organization as defined by α-actinin labeling. These results demonstrate, for the first time, an essential role of septins in cardiomyocyte physiology and heart function that is due, at least in part, to septin regulation of SOCE function.

INTRODUCTION:

Contractions of cardiomyocytes, the muscle cells of the heart, are driven by cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients that are generated through a process known as excitation-contraction coupling (ECC). During excitation-contraction coupling, depolarization of the plasma membrane or sarcolemma activates voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels, allowing a small quantity of Ca2+ to enter the cytoplasm. This Ca2+ from L-type channels then directly activates ryanodine receptor (RyR) Ca2+ release channels in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), resulting in a large cytoplasmic Ca2+ signal due to Ca2+ efflux from SR Ca2+ stores. It is the large quantity of Ca2+ that is released from the SR that drives myofilament sliding and cardiomyocyte contraction (Bers, 2002). Proper regulation of SR Ca2+ stores is therefore essential to physiological heart contractility, and several cardiomyopathies and heart failure are strongly associated with SR Ca2+ store dysregulation (Adeniran et al., 2015; Bers, 2002; Eisner et al., 2020; Njegic et al., 2020). Stored Ca2+ that is released by the RyR with each ECC cycle is pumped back into the SR by sarco/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase (SERCA) pumps (Kho, 2023). However, any net loss of Ca2+ from the cell can limit the available Ca2+ for SERCA pumps and result in SR Ca2+ store depletion. Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) is a Ca2+ influx mechanism that is activated specifically in response to SR Ca2+ store depletion, and Ca2+ that enters the cell via SOCE can be pumped into the SR by SERCA to replenish SR Ca2+ stores (Gruszczynska-Biegala et al., 2011; Ong et al., 2019). Recent work from our lab and others has demonstrated an essential role for cardiomyocyte SOCE in normal heart physiology, as cardiomyocyte SOCE suppression results in dilated cardiomyopathy and compromised cardiac output (Collins et al., 2014; Parks et al., 2016; Petersen et al., 2020). However, the mechanisms that regulate SOCE in cardiomyocytes and the specific functions of SOCE that are required for normal heart physiology are still poorly understood.

SOCE is a near-ubiquitous process that is functional in most animal cell types. SOCE is best understood in non-excitable cells such as immune and secretory cells, where it is coupled to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ store release by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) (Emrich et al., 2022). The role of SOCE in excitable cells including muscle is less clear. The SOCE Ca2+ influx mechanism consists of two primary molecular components: stromal interaction molecules, or Stim proteins, which function as SR Ca2+ sensors, and Orai Ca2+ influx channels in the plasma membrane. Stim proteins are located in the E/SR membrane and have an N-terminal EF-hand Ca2+ binding domain within the E/SR lumen. SR Ca2+ store depletion results in Ca2+ dissociation from Stim’s EF-hand domain, causing a conformational change that allows Stim to directly interact with and activate Orai Ca2+ influx channels. This interaction between Stim and Orai occurs at contact sites between the E/SR and plasma membranes (Putney, 2018). Mammals express two Stim molecules, STIM1 and STIM2, and three Orais (Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3), with STIM1 and Orai1 being the most widely expressed isoforms in most tissues. An accumulation of studies from diverse species now clearly demonstrate that SOCE plays a vital role in supporting normal heart function. For example, cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of STIM1 results in left ventricular dilation and reduced cardiac output in mice (Collins et al., 2014; Parks et al., 2016). Orai3 deletion also results in dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure in mice (Gammons et al., 2021), while Orai1 suppression results in reduced cardiomyocyte fractional shortening and heart failure in zebrafish (Volkers et al., 2012). Our own work in Drosophila also demonstrates that cardiomyocyte-specific depletion of the single Stim or Orai isoforms expressed in these animals causes dilated cardiomyopathy and early lethality (Petersen et al., 2020). A key question that remains to be addressed is how is SOCE properly regulated in cardiomyocytes to support physiological heart contractility and function? Mounting evidence from other cell types demonstrates that members of the septin family of cytoskeletal GTPases are essential SOCE regulators (Deb and Hasan, 2016), but the functional role of septins in cardiomyocytes is almost completely unknown.

Mammalian septins are subdivided into four groups of functionally homologous members: SEPT2 (SEPT1, SEPT2, SEPT4, SEPT5), SEPT3 (SEPT3, SEPT9, SEPT12), SEPT6 (SEPT6, SEPT8, SEPT10, SEPT11, SEPT14), and SEPT7 (SEPT7). Mammalian septins hetero-oligomerize to form hexameric or octameric filaments with the subunit group order SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7-SEPT7-SEPT6-SEPT2 for hexamers and SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7-SEPT3-SEPT3-SEPT7-SEPT6-SEPT2 for octamers (Cavini et al., 2021). Septin filaments generally localize to membranes and they are essential for numerous cellular processes including cytokinesis, ciliogenesis, and phagocytosis (Woods and Gladfelter, 2021). A role for septins in SOCE regulation was first demonstrated through a genome-wide siRNA screen in HeLa cells, in which it was shown that depletion of SEPT2 group members SEPT4 and SEPT5 results in suppression of SOCE-mediated Ca2+ influx (Sharma et al., 2013). Subsequent studies have demonstrated that septins modulate SOCE function by regulating ER-plasma membrane contact sites and Stim-Orai interaction at these sites (Katz et al., 2019; Sharma et al., 2013), as well as by regulating specific actin organizations at the plasma membrane that are required for Stim clustering and Orai activation (de Souza et al., 2021). The requirement for septins for proper SOCE activation has also been supported by a number of studies in Drosophila. Drosophila express five highly conserved septin subunits, with Drosophila Sept1 and Sept4 orthologous to mammalian SEPT2 group members, Drosophila Sept2 and Sept5 orthologous to SEPT6 group members, and Drosophila Sept7 or Pnut orthologous to SEPT7 (Shuman and Momany, 2021). The lack of SEPT3 orthologs means that Drosophila septins only form hexamers. Similar to mammalian cells, depletion of Drosophila SEPT2 subunits Sept1 and Sept4 strongly attenuated SOCE in neurons (Deb et al., 2016). This finding in Drosophila was also extended to SEPT6 subunits, as Drosophila Sept2 depletion also resulted in neuronal SOCE attenuation (Deb and Hasan, 2019). Thus, septin subunits from the SEPT2 and SEPT6 groups have essential and highly conserved roles in positive SOCE regulation in both excitable and non-excitable cells.

The goals of this project were to test the role of cardiomyocyte septins in heart function and to determine if there is functional association of septins with the SOCE pathway in these cells. We carried this out using genetic tools in the Drosophila heart. The Drosophila heart is a tube-shaped organ composed of contractile cardiomyocytes, and it circulates a lymph-like fluid called hemolymph throughout the animal’s body in an open circulatory system (Souidi and Jagla, 2021). Importantly, contractile physiology, including excitation-contraction coupling, is highly conserved between Drosophila and mammalian cardiomyocytes (Lin et al., 2011). Cardiomyocyte SOCE suppression in Drosophila results in phenotypes similar to those in mammals (Petersen et al., 2020), suggesting that SOCE function in Drosophila cardiomyocytes is also well-conserved. Thus, the Drosophila heart is a powerful model for testing conserved septin functions in cardiomyocyte SOCE regulation. Our results demonstrate that cardiomyocyte depletion of SEPT2 and SEPT6 group subunits results in dilated cardiomyopathy that phenocopies cardiomyocyte Stim and Orai depletion. We further demonstrate that the septin phenotypes are suppressed by genetic upregulation of SOCE function as well as by SERCA overexpression. These results demonstrate, for the first time, a functional role for SEPT2 and SEPT6 subunits in cardiomyocyte physiology that is due, at least in part, to positive regulation of SOCE.

RESULTS

Silencing Septins 1, 2, or 4 in cardiomyocytes causes cardiac dilation similar to SOCE suppression.

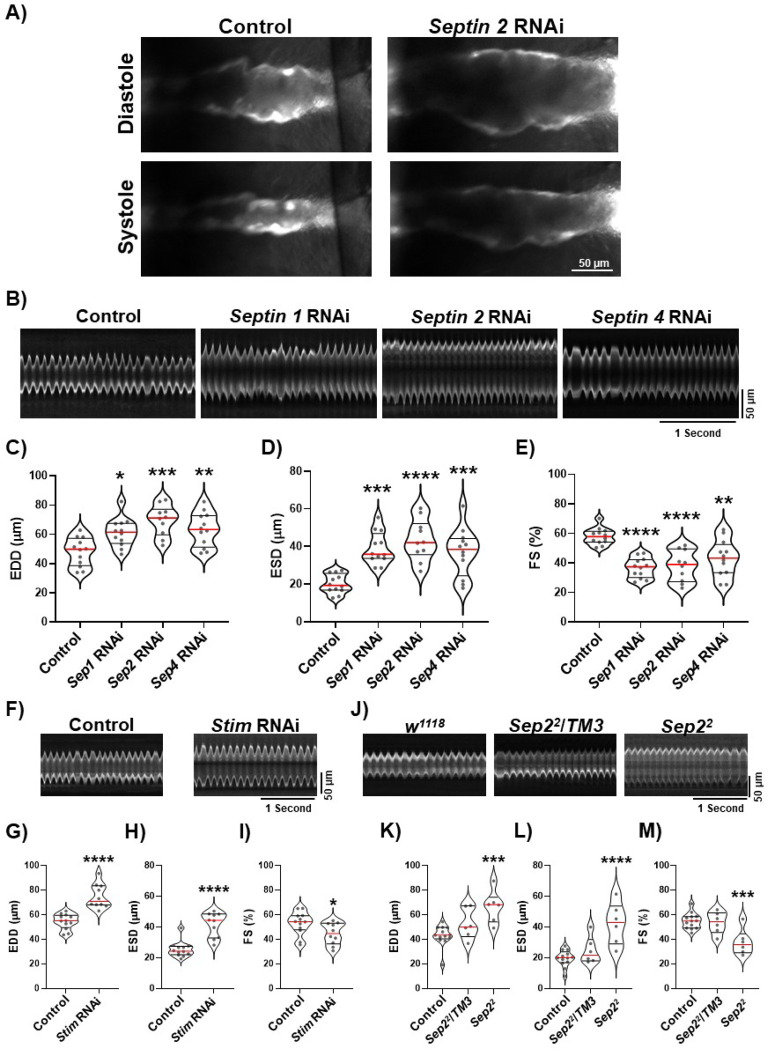

We first tested the effect of septin 1, 2, and 4 suppression on heart function in 3–5 day old adult flies using cardiomyocyte-specific RNAi expression driven by tinC-GAL4 (Ocorr et al., 2014). We used a cardiomyocyte-specific RNAi approach due to availability of reagents and to avoid cardiac-independent effects of whole-animal mutants. These animals also had cardiomyocyte-restricted tdTomato (CM-tdTom) expression for intravital imaging of heart contractility (Klassen et al., 2017; Petersen et al., 2020). We found that individual suppression of septins 1, 2, and 4 all resulted in significant heart dilation, as can be seen in representative still-frame images of diastole and systole and representative M-mode traces (Figure 1A, B). Direct measurements of end-diastolic dimensions (EDD) and end-systolic dimensions (ESD) from the M-mode traces demonstrated significant increases in both EDD and ESD for each of the septin groups, confirming marked dilation caused by septin suppression (Figure 1C, D). Fractional shortening (FS), a quantitative indicator of systolic function and cardiac output, was also significantly decreased by approximately 15–20% in hearts with cardiomyocyte-specific septin suppression (Figure 1E). We observed the significant changes in EDD, ESD, and FS in the septin-suppressed versus control hearts in both male and female animals, though the effects were somewhat more pronounced in females (Supplementary Figure S1). We therefore focused on female animals for the remainder of our studies. Heart rate and rhythmicity were not significantly altered in the septin-suppressed hearts compared to controls (Supplementary Figure S2). We also replicated our results with septin 1, 2, and 4 suppressions by RNAi using a second driver that expresses in cardiomyocytes, hand4.2-GAL4 (Han et al., 2006), suggesting the phenotypes we observed are due to cardiomyocyte-specific septin suppression (Supplementary Figure S3). We next took advantage of an available Drosophila septin 2 loss-of function mutant, septin22. As shown previously, homozygous septin22 animals exhibit significant developmental lethality but it is possible to obtain adult escapers, allowing us to analyze adult heart function in these animals (O’Neill and Clark, 2013; O’Neill and Clark, 2016). Consistent with the RNAi results, EDD and ESD were significantly increased and FS significantly decreased in septin22 compared to septin22/+ or w1118 control hearts (Figure F,-I). This important result confirms the essential requirement for septin 2 for proper heart function and suggests that the RNAi results are specific to septin suppression and not due to off-target effects. Overall, the combination of increased EDD and ESD and decreased FS in septin-suppressed hearts is consistent with the clinical features of dilated cardiomyopathy. And importantly, these results closely phenocopied the effects of cardiomyocyte-specific Stim suppression, which also resulted in increased EDD and ESD and decreased FS (Figure J-M). This is consistent with the hypothesis that the effects of septin suppression on the heart are due to suppression of Stim-dependent SOCE function.

Figure 1. Septin 1, 2, and 4 suppression results in heart dilation.

A) Representative still-frame images of CM-tdTom expressing Drosophila hearts at diastole and systole with tinC-GAL4 driven control or septin 2 RNAi. Images were taken from 5 second timelapse image sequences acquired at 200 frames/second. Note the significant increase in width of the septin 2 RNAi compared to control hearts at both diastole and systole. B) Representative M-mode traces from animals with tinC-GAL4 driven control, septin 1, septin 2, or septin 4 RNAi as indicated. C-E) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated tinC-GAL4 driven RNAi. F) Representative M-modes from animals with tinC-GAL4 driven control or Stim RNAi. G-I) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated tinC-GAL4 driven RNAi. J) Representative M-modes from control (w1118), Sep22 heterozygous (Sep22/TM3), or Sep22 homozygous animals. K-M) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated genotypes. For all plots each symbol represents the average of five measurements from a single animal’s M-mode. Red lines indicate median and black lines indicate quartiles. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 compared to control; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons for C-D and K-M, two-tailed t-test for G-I.

SOCE activation suppresses dilation of septin 2-deficient hearts

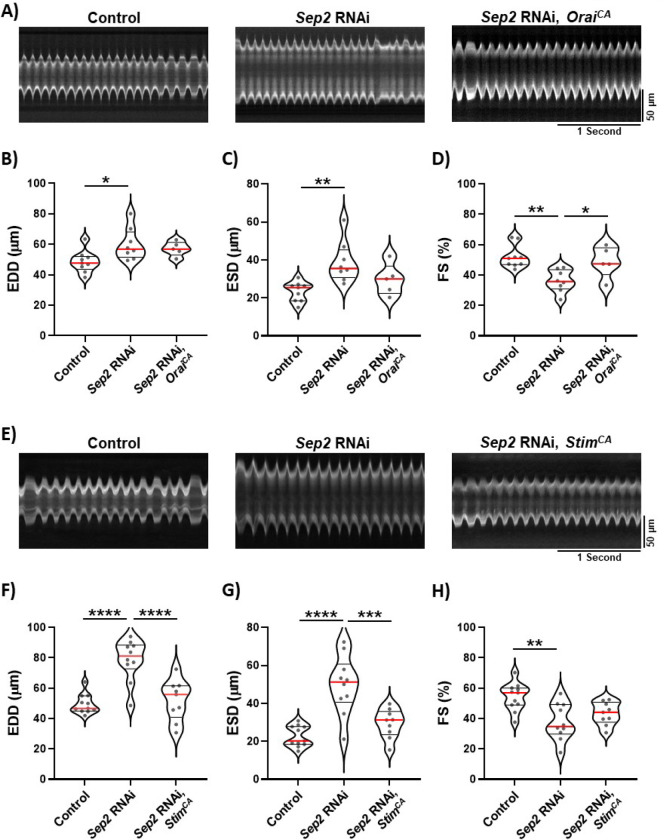

Given the striking similarities of the Septin and Stim suppression phenotypes and the previously defined role for septins in SOCE regulation, we hypothesized that septin suppression may cause heart dilation due to insufficient SOCE activation. We tested this by driving constitutive SOCE in septin 2-depleted hearts using constitutively active Orai and Stim mutant transgenes. We focused on septin 2 for the remainder of our experiments because of the strong phenotypes with septin 2 suppression and the lack of redundancy with other septin subunits that complicates analysis of septins 1 and 4. Constitutively active Orai has a glycine to methionine substitution in the channel hinge that locks the channel in an open conformation (Zheng et al., 2013). We previously demonstrated that this gain-of-function Orai mutant causes hypertrophy of the Drosophila heart (Petersen et al., 2022), consistent with cardiac hypertrophy that results from gain of SOCE function in mammals (Hulot et al., 2011). We found that the enlarged systolic dimensions of septin 2 RNAi hearts were reversed to near-control values when OraiCA was co-expressed, and reduced FS of septin 2 suppressed hearts was also reversed (Figure 2A–D). Enlarged diastolic dimensions of septin 2 suppressed hearts, on the other hand, were not as markedly reversed by OraiCA expression.

Figure 2. Septin 2 phenotypes are suppressed by SOCE upregulation.

A) Representative M-mode traces from animals with tinC-GAL4 driven control RNAi, septin 2 RNAi, or septin 2 RNAi with OraiCA. B-D) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated tinC-GAL4 driven transgenes. E) Representative M-mode traces from animals with tinC-GAL4 driven control RNAi, septin 2 RNAi, or septin 2 RNAi with StimCA. F-H) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated tinC-GAL4 driven transgenes. Each symbol in plots represents the average of five measurements from a single animal’s M-mode. Red lines indicate median and black lines indicate quartiles. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 compared to control; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

We next tested constitutively active Stim, which has two aspartic acid to alanine substitutions in the Ca2+-sensing EF-hand that lock Stim in a Ca2+-depleted, active conformation (Zhang et al., 2005). This StimCA transgene also drives hypertrophy of the Drosophila heart (Petersen et al., 2022). We found that StimCA expression strongly reversed enlargement of both diastolic and systolic dimensions caused by septin 2 depletion, and also restored FS to near control vales (Figure 2E–H). These results demonstrate that gain of SOCE function can largely reverse the effects of septin 2 depletion, supporting the hypothesis that the septin 2 effects are at least partly due to SOCE suppression. Differences in the reversal of septin 2 phenotypes with OraiCA versus StimCA may be due to stronger expression and/or penetrance of the StimCA transgene.

SERCA overexpression suppresses dilation of STIM, septin 2 deficient hearts.

A major function of SOCE is to provide cytoplasmic Ca2+ to SERCA pumps to refill SR Ca2+ stores. Importantly, dysregulation of cardiomyocyte SR Ca2+ uptake is strongly associated with heart failure (Luo and Anderson, 2013). It is therefore possible that the cardiomyocyte septin 2 depletion phenotypes may ultimately be caused by a reduction in SR Ca2+ store content due to suppression of SOCE. We tested this by determining whether SERCA overexpression, which would be expected to increase SR Ca2+ content, can reverse the septin 2 depletion phenotypes. It was first important to determine whether SERCA overexpression can reverse the effects of SOCE suppression. In support of this, we found that the significant increases in EDD and ESD caused by cardiomyocyte Stim depletion were fully reversed by SERCA overexpression (Figure 3A–C). Decreased FS with Stim depletion was also strongly reversed by SERCA overexpression (Figure 3D). SERCA overexpression alone did not significantly affect EDD, ESD, or FS compared to controls (Figure 3B–D). Thus, cardiomyocyte SERCA overexpression is an effective strategy for reversing the deleterious effects of SOCE suppression on heart function. We then found that similar to the results for Stim, increased EDD and ESD and decreased FS caused by septin 2 depletion were also fully reversed by SERCA overexpression (Figure 3A–D). These results strongly support our hypothesis that septin 2 is required in cardiomyocytes to support SOCE function that is essential for maintaining SR Ca2+ store content and proper heart contractility. We attempted to further support these findings by directly measuring both SR Ca2+ store content and contractile Ca2+ transients in Drosophila cardiomyocytes based on imaging of the genetically encoded jRGECO Ca2+ indicator in vivo and in partially dissected preparations. Unfortunately, however, technical challenges prevented us from acquiring reliable data from these experiments.

Figure 3. Septin 2 phenotypes are suppressed by SERCA overexpression.

A) Representative M-mode traces from animals with tinC-GAL4 driven transgenes as indicated. B-D) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals with indicated tinC-GAL4 driven transgenes. Each symbol in plots represents the average of five measurements from a single animal’s M-mode. Red lines indicate median and black lines indicate quartiles. **, P<0.01, ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons.

Septin 2 phenotypes do not involve developmental defects or alterations of z-disc integrity

Our results thus far suggest that a major function of septin 2 in cardiomyocytes is SOCE regulation. We also considered the possibility that septin 2 has additional, SOCE-independent functions in cardiomyocytes that are required for proper heart physiology. Septins are required for cytokinesis and because cardiomyocytes in the adult heart are post-mitotic, cytokinesis dysfunction due to septin 2 depletion in cardiomyocytes would most likely occur during heart development. We therefore tested whether septin 2 depletion phenotypes in the adult heart are due to developmental dysfunctions by initiating cardiomyocyte septin 2 depletion post-developmentally in adults using the GAL4/GAL80[ts] inducible expression system. GAL80 is a competitive GAL4 inhibitor that blocks transcriptional activation when active. Temperature sensitive GAL80 (GAL80[ts]) is active at the permissive temperature of 18° C but is inactive at temperatures above 27° C. Thus, animals co-expressing GAL80[ts] and GAL4 are reared at 18° C to prevent UAS gene expression by GAL4, but moved to 27° C to induce expression. We generated animals that co-express ubiquitous tubP-GAL80[ts] with tinC-GAL4, together with either septin 2 or control RNAi. These animals also expressed CM-tdTom for heart contractility analysis. We first tested animals that were maintained at 18° C throughout development as well as adulthood until the time of analysis as a control to verify GAL80[ts] efficacy, as this temperature paradigm should suppress RNAi expression for the entire experiment. As expected, EDD, ESD, and FS values were no different for septin 2 versus control RNAi animals maintained at 18° C throughout the experiment (Figure 4A–D). We then tested animals that were maintained at 18° C throughout development but were then shifted to 27° C as one or two day-old adults to initiate RNAi expression. Heart contractility was then analyzed in these animals 3–5 days after the shift to 27° C. Remarkably, EDD and ESD values of temperature-shifted septin 2 RNAi animals were significantly increased compared to control RNAi animals (Figure 4E–G), similar to results in Figure 1 with RNAi expression throughout development. FS was slightly decreased in septin 2 versus control RNAi animals but this was not statistically significant (Figure 4H). These results essentially recapitulate the effects of septin 2 depletion throughout development, suggesting that any cardiomyocyte septin 2 functions during development do not contribute significantly to the contractility phenotypes we observe in the adult heart.

Figure 4. Post-developmental septin 2 depletion is sufficient to drive the heart dilation phenotype.

A) Representative M-mode traces for animals expressing TubP-GAL8[ts] and tinC-GAL4 with either control or septin 2 RNAi. These animals were maintained at 18° C to suppress RNAi expression from the time of egg laying until intravital imaging was carried out as adults. B-D) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals expressing TubP-GAL80[ts] and tinC-GAL4 and indicated RNAi and maintained continuously at 18° C until intravital imaging as adults as described in A. E) Representative M-mode traces for animals expressing TubP-GAL80[ts] and tinC-GAL4 with either control or septin 2 RNAi. These animals were first maintained at 18° C from the time of egg laying until adults were one day old to suppress RNAi expression throughout development. One day adults were then moved to 27° C to activate RNAi expression, and were maintained at 27° C for 3–5 days until intravital imaging was carried out. F-H) Plots of EDD, ESD, and FS, respectively, calculated from M-modes for animals expressing TubP-GAL80[ts] and tinC-GAL4 and indicated RNAi and moved from 18° C to 27° C as one day old adults as described in E. Each symbol in plots represents the average of five measurements from a single animal’s M-mode. Red lines indicate median and black lines indicate quartiles. **, P<0.01 compared to control, two-tailed t-test.

It has previously been shown that septin 7 localizes to z-disks in mouse skeletal myofibers (Gönczi et al., 2022), and that septin 7 depletion in zebrafish results in z-disk disruption in cardiac muscle (Dash et al., 2017). We therefore analyzed z-disks in septin 2-depleted cardiomyocytes to determine if septin 2 is similarly required for Drosophila cardiomyocyte z-disc integrity. As shown in Figure 5A, z-discs labeled with an anti-α-actinin antibody in septin22 homozygous mutant cardiomyocytes were nearly identical to those from w1118 controls, with no differences in α-actinin labeling intensity or localization pattern. We did note, however, an approximately 25% increase in spacing between z-disks indicative of longer sarcomeres in septin22 compared to w1118 cardiomyocytes (Figure 5A,B). This increase in sarcomere length may underlie the overall dilation of septin 2 as well as Stim depleted hearts, and is therefore consistent with SOCE suppression resulting from loss of septin 2.

Figure 5. Septin 2 suppression results in increased z-disk spacing but does not alter z-disk integrity.

A) Left: representative images of segments of hearts from w1118 (control) or Sep22 animals labeled with anti-α-actinin antibody (green). Also shown is CM-tdTom fluorescence (red) to label cardiomyocytes. Images are z-projections encompassing approximately the dorsal half of the heart. Thick dashed lines indicate the lateral boundaries of the heart and the dashed boxed indicate the magnified regions shown on the right. Right: Magnified images of labeled α-actinin from boxed regions indicated in merged images on the left. Yellow lines indicate the spacing between adjacent z-disks. B) Plot of measured distance between α-actinin labeled z-disks from w1118 control or Sep22 hearts. Each symbol represents the average of measurements from a single heart. Red lines indicate median and black lines indicate quartiles. **, P<0.01 compared to w1118 control, two-tailed t-test.

DISCUSSION

Collectively, our data demonstrate for the first time that cardiomyocyte expression of group 2 and group 6 septin monomers is required for proper heart function. We further show that the effects of septin suppression on heart function are likely due, at least in part, to suppression of cardiomyocyte SOCE. Cardiomyocyte-specific suppression of Drosophila group 2 septins 1 and 4 and group 6 septin 2 resulted in marked heart dilation and reduced fractional shortening, nearly identical to the effects of cardiomyocyte Stim and Orai suppression that we previously showed (Petersen et al., 2020). Direct genetic evidence of the functional association of septins with the SOCE machinery is provided by our data demonstrating that the effects of septin depletion are suppressed by SOCE upregulation through StimCA or OraiCA expression. We also show that SERCA overexpression suppresses dilation associated with both STIM and Septin 2 depletion, further suggesting that both STIM and Septin 2 functions converge on the regulation of SR Ca2+ stores. Lastly we show that heart dilation due to Septin 2 depletion is not due solely to possible roles for septin 2 in heart development, and that septin 2 depletion does not result in disruption of α-actinin localization or organization at z-disks that anchor actin within thin filaments. While these latter experiments do not rule out all possible SOCE-independent functions of septins in heart physiology, they do reinforce our overall findings that SOCE regulation is an essential function of septins in cardiomyocytes.

The mechanisms by which septins regulate SOCE function in cardiomyocytes or other cell types are still not entirely clear. Data from mammalian cells demonstrate that septins do not directly interact with Stim or Orai proteins, but instead may regulate the microenvironment at E/SR-plasma membrane junctions to facilitate Stim-Orai interactions, as well as the number and size of the junctions themselves (Katz et al., 2019). Septins directly interact with membrane phospholipids (Bridges and Gladfelter, 2015; Szuba et al., 2021), and septin-dependent reorganization of PIP2 is required for Stim-Orai association and optimal Orai channel gating (de Souza et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2013). Septins and PIP2 also coordinately regulate actin remodeling within ER-plasma membrane junctions in human HEK293 cells, and disruption of this remodeling through depletion of human SEPT4, PIP2, or the actin regulatory factors CDC42 and ARP2 disrupted STIM1 clustering at junctions and SOCE activation (de Souza et al., 2021). We attempted to analyze SR-plasma membrane junctions as well as Stim clustering at these junctions in Drosophila cardiomyocytes within the intact heart, but the complex architecture of the heart made imaging these structures extremely challenging. Thus it remains to be determined whether the phenotypes we observed with septin depletion in Drosophila cardiomyocytes similarly reflect a requirement for septins in regulating the membrane architecture required for Stim-Orai association. An interesting extension of this is whether septins in cardiomyocytes also regulate the SR – t-tubule dyad junctions that are required for functional coupling between L-type Ca2+ channels and RyRs for EC coupling. We did not observe any severe deficits in overall contractility of the heart as would be expected if EC coupling were compromised, suggesting that dyad junctions remain intact in septin-depleted cardiomyocytes. One possibility is that Stim and Orai interact at SR-plasma membrane junctions in cardiomyocytes that are distinct from the dyad junctions that bring RyR and L-type Ca2+ channels in close proximity, as has been suggested in mammalian skeletal muscle (Michelucci et al., 2018).

Interestingly, while depletion of group 2 and 6 septins consistently results in SOCE suppression in multiple cell types from flies to mammals, septin 7 depletion results in gain of SOCE function in Drosophila neurons and human neural progenitor cells (Deb et al., 2020; Deb and Hasan, 2019; Deb et al., 2016). We did not test septin 7 in this current study, but these prior findings suggest that SOCE regulation by septins is subunit specific. One possible explanation for this subunit specificity is that it is related to the position of the septin subunits within the hexameric septin filament (Deb and Hasan, 2016). For example, it is possible that loss of group 2 or 6 subunits results in shortened but not fully disassembled filaments, and that these truncated filaments interfere with PIP2 and actin regulation at membrane contact sites. Septin 7 depletion, on the other hand, may result in complete disassembly of filaments due to septin 7 occupying the central core positions within the filament. A complete lack of septin filaments may then allow dysregulated formation of ectopic membrane contact sites. Another possibility is that septin subunits may have functions that are independent of their assembly into filaments. This possibility is supported by the demonstration that septin 7 dimerization, which is required for filament assembly, is dispensable for septin 7 function in cytokinesis (Abbey et al., 2016).

Our evidence in support of septin regulation of SOCE in Drosophila cardiomyocytes would be further reinforced by direct measurements of SOCE using Ca2+ imaging in this system. Unfortunately, multiple attempts at these measurements in Drosophila cardiomyocytes from both intact and dissociated hearts were unsuccessful. However, direct SOCE measurements in isolated Drosophila neurons demonstrated that depletion of septin 2 or combined depletion of septins 1 and 4 resulted in near-complete suppression of SOCE-mediated Ca2+ influx (Deb and Hasan, 2019). Thus, septin regulation of SOCE is clearly conserved between Drosophila and mammalian cells. Direct SOCE measurements in isolated mammalian cardiomyocytes may offer further insight into the specific effects of septin depletion on cardiomyocyte Ca2+ transport and homeostasis.

In conclusion our results clearly demonstrate an essential role for septins in cardiomyocyte physiology and overall heart function. Our genetic data strongly support a specific role for septins in regulating the SOCE Ca2+ transport pathway. These findings further add to our understanding of the essential role that SOCE plays in regulating heart physiology, and suggest a novel functional association between cytoskeletal regulation and Ca2+ transport mechanisms in cardiomyocytes. Important future directions of this work include determining if septin regulation of SOCE is conserved in mammalian cardiomyocytes and directly analyzing the effects of septin disruption on cardiomyocyte Ca2+ transport and homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila Stocks and Husbandry

The following fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: GAL4 control RNAi (35783), STIM RNAi (27263) Septin 1 RNAi (27709) Septin 2 RNAi (28004), Septin 4 RNAi (31119), SEP22/TM6 (91003), UAS-SERCA (63228), and TubP-GAL80[ts] (7019). The tinC-GAL4 stock was provided by Dr. Manfred Frausch (Freidrich Alexander University), and the CM-tdTom flies were obtained from Dr. Rolf Bodmer (Sanford Burnham Prebys Institute). UAS-StimCA was generated by our lab as previously described (Petersen et al., 2022) and UAS-OraiCA was obtained from Dr. Gaiti Hassan (National Center for Biological Sciences, Bangalore, India). Flies were maintained on standard cornmeal fly food and crosses were at 25° C unless otherwise indicated.

Heart dissection, Immunofluorescence labeling, and confocal imaging

Adult female flies were anesthetized with CO2 and adhered to a 20 mm petri dish dorsal side down with petroleum jelly. The flies were then bathed in an artificial Drosophila hemolymph solution (ADH) (108 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2mM CaCl2, 8mM MgCl2, 1mM NaH2PO4, 4 mM NaHCO3, 10mM sucrose, 5mM trehalose, and 5mM HEPES pH 7.1). The dissection proceeded by removing the head, the ventral section of the abdomen, and internal organs that obstructed the view of the heart. Once the heart was exposed, the ADH solution was replaced with new ADH containing 10 mM EGTA to stop heart contractions. Once the heart no longer exhibited visible contractions, the ADH with EGTA was removed and hearts were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 15 minutes. Fixed hearts were then washed three times for 10 minutes each with gentle rotation in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T). The samples were then moved to a single well of a 96 well plate and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4° C. The primary antibody used was mouse monoclonal anti-α-actinin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank 2G3–3D7) at 1:1000. Samples were then washed three times in PBS-T for 10 minutes, and incubated in Alexa fluor 488 goat anti-mouse secondary at 1:500 for 1 hour at room temperature. After three 10 minute washes in PBS-T samples were mounted onto a glass microscope slide in Vectashield (Vectashield laboratories), with the dorsal exoskeleton facing the glass slide and the heart facing the coverslip. The samples were then imaged on a Nikon A1R confocal microscope using a 40X, 1.3 NA objective. Image stacks were acquired with a z-spacing of 1 μm to encompass approximately the dorsal half of the heart, and image stacks are presented as maximum intensity z-projections to show α-actinin labeling within single cardiomyocytes. Images were processed using ImageJ. α-actinin-labeled z-disk spacing was calculated by measuring the distance between adjacent z-disks using ImageJ.

Intravital contractility imaging:

Intravital imaging was conducted as previously described (Petersen et al., 2020). Briefly 3–7 day old female animals expressing CM-tdTom were anesthetized with CO2 and their dorsal abdomens were adhered to glass coverslips using Norland Optical Adhesive cured with a 48-watt UV LED light source for 60 seconds. Animals were allowed to recover for several minutes prior to imaging until they exhibited visible leg movements. CM-tdTom-labeled hearts were imaged through the dorsal cuticle on a Nikon Ti2 inverted microscope controlled with Nikon Elements software. Images were acquired at a rate of 200 frames per second using an ORCA-Flash4.0 V3 sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu) and excitation of CM-tdTom by 550 nm light from a Spectra-X illuminator (Lumencor). M-mode traces were generated using ImageJ by drawing a 1-pixel wide line through the A-1 chamber of the heart, and fluorescence intensity along this line was plotted over time using the MultiKymograph function of ImageJ. EDD and ESD were manually measured directly from the M-mode traces at points of full relaxation or contraction, respectively. The average of 5 measurements for EDD and ESD was reported for each animal and FS was calculated as [(EDD-ESD)/EDD] x 100. Heart rate was calculated from the M-mode traces by counting the number of contractions over the full timecourse.

Conditional expression with TubP-GAL80[ts]:

Fly crosses were carried out to obtain animals that carried tinC-GAL4, TubP-GAL480[ts], and UAS-RNAi transgenes. Crosses were maintained at 18° C until the time of eclosion of new progeny. Progeny with the appropriate genotypes were maintained at 18° C for an additional two days, and were then either kept at 18° C or transferred to 27° C for an additional 3–5 days. Animals were then analyzed by intravital heart imaging as previously described.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism software. Data sets with two conditions were analyzed with two-tailed t-tests and datasets with three or more conditions were analyzed by one way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparisons. Statistical significance for all tests was considered at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Uniformed Services University intramural grant I80VP000404 and NIH grant R21 NS121821 to J.T.S. Reagents obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537).

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

REFERENCES

- Abbey M., Hakim C., Anand R., Lafera J., Schambach A., Kispert A., Taft M.H., Kaever V., Kotlyarov A., Gaestel M., and Menon M.B.. 2016. GTPase domain driven dimerization of SEPT7 is dispensable for the critical role of septins in fibroblast cytokinesis. Sci Rep. 6:20007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeniran I., MacIver D.H., Hancox J.C., and Zhang H.. 2015. Abnormal calcium homeostasis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is related to both reduced contractile function and incomplete relaxation: an electromechanically detailed biophysical modeling study. Front Physiol. 6:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers D.M. 2002. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 415:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges A.A., and Gladfelter A.S.. 2015. Septin Form and Function at the Cell Cortex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 290:17173–17180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavini I.A., Leonardo D.A., Rosa H.V.D., Castro D., D’Muniz Pereira H., Valadares N.F., Araujo A.P.U., and Garratt R.C.. 2021. The Structural Biology of Septins and Their Filaments: An Update. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:765085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins H.E., He L., Zou L., Qu J., Zhou L., Litovsky S.H., Yang Q., Young M.E., Marchase R.B., and Chatham J.C.. 2014. Stromal interaction molecule 1 is essential for normal cardiac homeostasis through modulation of ER and mitochondrial function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 306:H1231–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash S.N., Narumanchi S., Paavola J., Perttunen S., Wang H., Lakkisto P., Tikkanen I., and Lehtonen S.. 2017. Sept7b is required for the subcellular organization of cardiomyocytes and cardiac function in zebrafish. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 312:H1085–h1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza L.B., Ong H.L., Liu X., and Ambudkar I.S.. 2021. PIP(2) and septin control STIM1/Orai1 assembly by regulating cytoskeletal remodeling via a CDC42-WASP/WAVE-ARP2/3 protein complex. Cell calcium. 99:102475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B.K., Chakraborty P., Gopurappilly R., and Hasan G.. 2020. SEPT7 regulates Ca(2+) entry through Orai channels in human neural progenitor cells and neurons. Cell calcium. 90:102252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B.K., and Hasan G.. 2016. Regulation of Store-Operated Ca(2+) Entry by Septins. Front Cell Dev Biol. 4:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B.K., and Hasan G.. 2019. SEPT7-mediated regulation of Ca(2+) entry through Orai channels requires other septin subunits. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken). 76:104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B.K., Pathak T., and Hasan G.. 2016. Store-independent modulation of Ca(2+) entry through Orai by Septin 7. Nat Commun. 7:11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner D.A., Caldwell J.L., Trafford A.W., and Hutchings D.C.. 2020. The Control of Diastolic Calcium in the Heart: Basic Mechanisms and Functional Implications. Circ Res. 126:395–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrich S.M., Yoast R.E., and Trebak M.. 2022. Physiological Functions of CRAC Channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 84:355–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammons J., Trebak M., and Mancarella S.. 2021. Cardiac-Specific Deletion of Orai3 Leads to Severe Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Heart Failure in Mice. J Am Heart Assoc. 10:e019486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczi M., Ráduly Z., Szabó L., Fodor J., Telek A., Dobrosi N., Balogh N., Szentesi P., Kis G., Antal M., Trencsenyi G., Dienes B., and Csernoch L.. 2022. Septin7 is indispensable for proper skeletal muscle architecture and function. Elife. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruszczynska-Biegala J., Pomorski P., Wisniewska M.B., and Kuznicki J.. 2011. Differential roles for STIM1 and STIM2 in store-operated calcium entry in rat neurons. PLoS One. 6:e19285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Yi P., Li X., and Olson E.N.. 2006. Hand, an evolutionarily conserved bHLH transcription factor required for Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development (Cambridge, England). 133:1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulot J.S., Fauconnier J., Ramanujam D., Chaanine A., Aubart F., Sassi Y., Merkle S., Cazorla O., Ouille A., Dupuis M., Hadri L., Jeong D., Muhlstedt S., Schmitt J., Braun A., Benard L., Saliba Y., Laggerbauer B., Nieswandt B., Lacampagne A., Hajjar R.J., Lompre A.M., and Engelhardt S.. 2011. Critical role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 124:796–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Z.B., Zhang C., Quintana A., Lillemeier B.F., and Hogan P.G.. 2019. Septins organize endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions for STIM1-ORAI1 calcium signalling. Scientific reports. 9:10839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho C. 2023. Targeting calcium regulators as therapy for heart failure: focus on the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase pump. Front Cardiovasc Med. 10:1185261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen M.P., Peters C.J., Zhou S., Williams H.H., Jan L.Y., and Jan Y.N.. 2017. Age-dependent diastolic heart failure in an in vivo Drosophila model. eLife. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N., Badie N., Yu L., Abraham D., Cheng H., Bursac N., Rockman H.A., and Wolf M.J.. 2011. A method to measure myocardial calcium handling in adult Drosophila. Circulation research. 108:1306–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M., and Anderson M.E.. 2013. Mechanisms of altered Ca²⁺ handling in heart failure. Circ Res. 113:690–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelucci A., García-Castañeda M., Boncompagni S., and Dirksen R.T.. 2018. Role of STIM1/ORAI1-mediated store-operated Ca(2+) entry in skeletal muscle physiology and disease. Cell Calcium. 76:101–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njegic A., Wilson C., and Cartwright E.J.. 2020. Targeting Ca(2 +) Handling Proteins for the Treatment of Heart Failure and Arrhythmias. Front Physiol. 11:1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill R.S., and Clark D.V.. 2013. The Drosophila melanogaster septin gene Sep2 has a redundant function with the retrogene Sep5 in imaginal cell proliferation but is essential for oogenesis. Genome. 56:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill R.S., and Clark D.V.. 2016. Partial Functional Diversification of Drosophila melanogaster Septin Genes Sep2 and Sep5. G3 (Bethesda). 6:1947–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocorr K., Vogler G., and Bodmer R.. 2014. Methods to assess Drosophila heart development, function and aging. Methods (San Diego, Calif.). 68:265–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong H.L., Subedi K.P., Son G.Y., Liu X., and Ambudkar I.S.. 2019. Tuning store-operated calcium entry to modulate Ca(2+)-dependent physiological processes. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1866:1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks C., Alam M.A., Sullivan R., and Mancarella S.. 2016. STIM1-dependent Ca(2+) microdomains are required for myofilament remodeling and signaling in the heart. Scientific reports. 6:25372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C.E., Tripoli B.A., Schoborg T.A., and Smyth J.T.. 2022. Analysis of Drosophila cardiac hypertrophy by microcomputerized tomography for genetic dissection of heart growth mechanisms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 322:H296–h309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C.E., Wolf M.J., and Smyth J.T.. 2020. Suppression of store-operated calcium entry causes dilated cardiomyopathy of the Drosophila heart. Biol Open. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J.W. 2018. Forms and functions of store-operated calcium entry mediators, STIM and Orai. Adv Biol Regul. 68:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Quintana A., Findlay G.M., Mettlen M., Baust B., Jain M., Nilsson R., Rao A., and Hogan P.G.. 2013. An siRNA screen for NFAT activation identifies septins as coordinators of store-operated Ca2+ entry. Nature. 499:238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman B., and Momany M.. 2021. Septins From Protists to People. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:824850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souidi A., and Jagla K.. 2021. Drosophila Heart as a Model for Cardiac Development and Diseases. Cells. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szuba A., Bano F., Castro-Linares G., Iv F., Mavrakis M., Richter R.P., Bertin A., and Koenderink G.H.. 2021. Membrane binding controls ordered self-assembly of animal septins. Elife. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkers M., Dolatabadi N., Gude N., Most P., Sussman M.A., and Hassel D.. 2012. Orai1 deficiency leads to heart failure and skeletal myopathy in zebrafish. Journal of cell science. 125:287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods B.L., and Gladfelter A.S.. 2021. The state of the septin cytoskeleton from assembly to function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 68:105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.L., Yu Y., Roos J., Kozak J.A., Deerinck T.J., Ellisman M.H., Stauderman K.A., and Cahalan M.D.. 2005. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature. 437:902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H., Zhou M.H., Hu C., Kuo E., Peng X., Hu J., Kuo L., and Zhang S.L.. 2013. Differential roles of the C and N termini of Orai1 protein in interacting with stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) for Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 288:11263–11272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.