Abstract

Mutations in LRRK2 are the most common genetic cause of Parkinson’s disease (PD). LRRK2 protein contains two enzymatic domains: a GTPase (Roc-COR) and a kinase domain. Disease-causing mutations are found in both domains. Now, studies have focused largely on LRRK2 kinase activity, while attention to its GTPase function is limited. LRRK2 is a guanine nucleotide–binding protein, but the mechanism of direct regulation of its GTPase activity remains unclear and its physiological GEF is not known. Here, we identified CalDAG-GEFI (CDGI) as a physiological GEF for LRRK2. CDGI interacts with LRRK2 and increases its GDP to GTP exchange activity. CDGI modulates LRRK2 cellular functions and LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration in both LRRK2 Drosophila and mouse models. Together, this study identified the physiological GEF for LRRK2 and provides strong evidence that LRRK2 GTPase is regulated by GAPs and GEFs. The LRRK2 GTPase, GAP, or GEF activities have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets, which is distinct from the direct LRRK2 kinase inhibition.

CalDAG-GEFI was identified as a GEF and a key regulator for the most common Parkinson’s disease protein, LRRK2.

INTRODUCTION

Mutations in the Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene have been causally linked to both sporadic and autosomal dominant forms of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (1–3). LRRK2-mediated disease is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from sporadic PD (1). Given its strong genetic link to PD, LRRK2 represents a clear and compelling target for therapeutic development for PD. However, the mechanisms to regulate LRRK2 function and the pathologic actions responsible for the LRRK2-linked disease remain unclear. LRRK2 is a large multifunctional protein that contains two important enzymatic domains: a guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) domain [Roc and a C terminus of Ras of the complex domain (COR)], a kinase domain, and multiple protein-protein interacting domains (3–7). Disease-causing mutations are found in both enzymatic domains, indicating their importance in pathogenesis. Accumulating studies have focused largely on the kinase activity of LRRK2 (8–24), while attention to regulation of the GTPase domain is limited (5, 7, 25–27). However, recent findings indicate that kinase modulators of LRRK2 have off-target effects or on-target side effects (9, 28–32). Alternatively, regulation of LRRK2’s GTPase activity may provide previously unknown insight into the pathogenesis of PD and ultimately open up alternative therapeutic opportunities for PD treatment (6, 33).

LRRK2 is a guanine nucleotide–binding protein (G-protein). The mechanism of direct regulation of its GTPase function is unclear. G-proteins are molecular switches in which the “on” state involves guanosine triphosphate (GTP) binding and the “off” state involves guanosine diphosphate (GDP) binding following GTP hydrolysis. This process is typically regulated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) and guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) (34). In addition, some G-proteins can be activated by nucleotide-dependent dimerization (GAD) (35). Whether LRRK2 is regulated by GAPs and GEFs or is a GAD has been debated. Studies using the bacteria Chlorobium tepidum protein with a Roc-COR structure suggest that LRRK2 has the capacity to function as a GAD (36). However, this study used a prokaryote LRRK2 homolog protein, and the structure requires intermolecular exchange of an arginine residue in trans to constitute an active site, but the required arginine does not exist in human LRRK2 (37). Recent studies using human LRRK2 proteins suggest that LRRK2’s GTPase activity requires both GAPs and GEFs due to the low intrinsic catalytic activity but high-affinity binding of GTP/GDP (37, 38).

Our previous work identified ArfGAP1 as a GAP candidate for LRRK2 (7, 27), and another study identified ARHGEF7 as an interacting protein for LRRK2 that did not function as a GEF for LRRK2 (25). Thus, the physiological GEF for LRRK2 has remained unknown. Here, we report that striatum-enriched CalDAG-GEFI (CDGI) (39) interacts with LRRK2 and that CDGI acts as a GEF for LRRK2 to increase LRRK2 GDP to GTP exchange activity and modulates LRRK2 cellular functions and LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration in both LRRK2 Drosophila and mouse models.

RESULTS

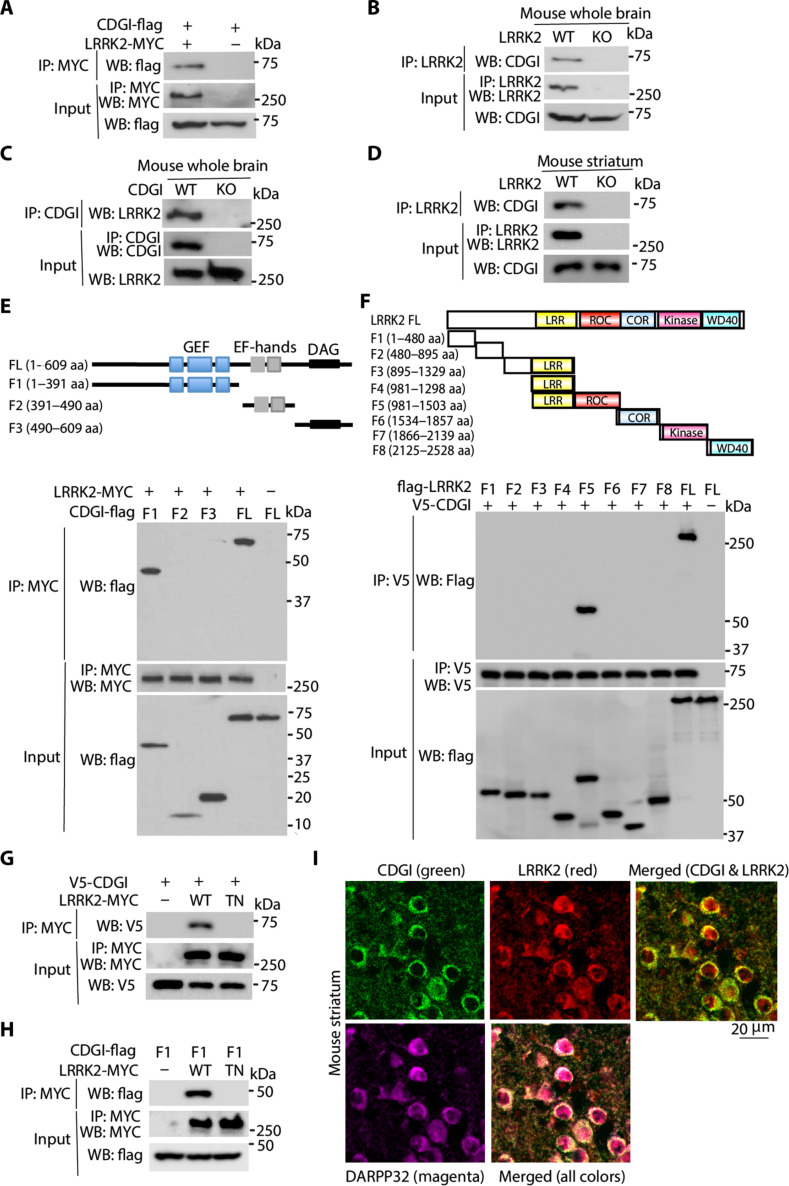

CDGI interacts with LRRK2

To identify LRRK2 interactors, we performed a yeast two-hybrid experiment and identified CDGI [the calcium and diacylglycerol (DAG)–regulated guanine nucleotide exchange factor I] as an interacting protein of LRRK2. To confirm the interaction between LRRK2 and CDGI, we first performed coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) using overexpressed MYC-LRRK2 and CDGI-flag in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells (Fig. 1A) and confirmed that LRRK2 interacts with CDGI in mammalian cells. To determine whether LRRK2 interacts with CDGI in the mouse brain, we conducted co-IP in whole brain lysates from LRRK2 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice using a LRRK2 antibody to pull down CDGI. Endogenous LRRK2 pulled down endogenous CDGI in LRRK2 WT but not KO mice (Fig. 1B). We also conducted co-IP in whole brain lysate from CDGI WT and KO brain tissue using a CDGI antibody to pull down LRRK2. Endogenous CDGI pulled down endogenous LRRK2 in CDGI WT but not KO mice (Fig. 1C). Given that LRRK2 and CDGI were both reported to be enriched in the striatum (39–45), we conducted co-IP in mouse striatal lysate, where a strong interaction between LRRK2 and CDGI was observed (Fig. 1D). To determine the domain of CDGI that interacts with LRRK2, CDGI deletion mutations F1 to F3 were generated. F1 contains the N-terminal GEF domain, F2 contains the Ca2+-binding EF-hands domain, while F3 contains the DAG domain at the C terminus of CDGI. The CDGI deletion mutants were used to examine their interactions with LRRK2 in HEK 293T cells. We found that the F1 mutation, which contains GEF domain of CDGI, interacts with LRRK2 (Fig. 1E). By contrast, both F2 and F3 mutations failed to interact with LRRK2. The binding domain on LRRK2 that interacts with CDGI was determined using a deletion mutation series spanning the entire LRRK2 protein (7, 23). CDGI predominantly bound to the ROC domains of LRRK2 (Fig. 1F). Since CDGI is a GEF, we asked whether CDGI binding to LRRK2 requires guanine nucleotide (GDP/GTP) binding activity of LRRK2. To this end, we used an LRRK2 mutant T1348N (TN), which is located in the P-loop of the ROC domain of LRRK2 and disrupts LRRK2 GDP/GTP binding, to perform co-IP experiments with full-length and the F1 domain of CDGI. Neither full-length nor F1 domain CDGI binds to LRRK2-TN mutant (Fig. 1, G and H). This suggests that the CDGI binding to LRRK2 requires LRRK2 guanine nucleotide binding activity, and the GEF domain of CDGI is positioned close to the LRRK2 GDP/GTP binding site. Given that both CDGI and LRRK2 were reported to be highly expressed in the striatum (39–45) and they bind to each other, we set out to conduct colocalization experiments of LRRK2 and CDGI in spiny projection neurons (SPNs) in the striatum (Fig. 1I). DARPP32 (dopamine- and cAMP-regulated neuronal phosphoprotein) was used as a marker for SPNs. CDGI and LRRK2 highly colocalize in SPNs (Fig. 1I). Together, these findings indicate that LRRK2 interacts with CDGI both in mammalian cells and in brain tissue lysates, where the N-terminal GEF domain of CDGI interacts with LRRK2 and the ROC domain of LRRK2 interacts with CDGI, and CDGI and LRRK2 highly colocalize in SPNs in the striatum.

Fig. 1. CDGI interacts with LRRK2.

(A) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between MYC-tagged LRRK2 and flag-tagged CDGI in cotransfected HEK 293T cells. Co-IP with anti-MYC was followed by anti-flag immunoblotting. (B) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between LRRK2 and CDGI in mouse brain lysates. Lysates prepared from LRRK2 WT and KO mouse whole brains were subjected to IP with anti-LRRK2 followed by anti-CDGI and anti-LRRK2 immunoblotting. (C) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between LRRK2 and CDGI in mouse brain lysates. Lysates prepared from CDGI WT and KO mouse whole brains were subjected to IP with anti-CDGI followed by anti-LRRK2 and anti-CDGI immunoblotting. (D) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between LRRK2 and CDGI in mouse striatal lysates. Lysates prepared from LRRK2 WT and KO mouse striatum were subjected to IP with anti-LRRK2 followed by anti-CDGI and anti-LRRK2 immunoblotting. (E) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between MYC-tagged LRRK2 and flag-tagged F1 (the GEF domain), F2 (the EF-hands domain), F3 (the DAG domain), or full-length (FL) CDGI in cotransfected HEK 293T cells. Co-IP with anti-MYC was followed by anti-flag or anti-MYC immunoblotting. A schematic representation of CDGI F1, F2, and F3 domains is shown. (F) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between V5-tagged CDGI and flag-tagged LRRK2 fragments in cotransfected HEK 293T cells. Co-IP with anti-V5 was followed by anti-flag or anti-V5 immunoblotting. A schematic representation of the different LRRK2 fragments is shown. (G) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between V5-tagged CDGI and MYC-tagged LRRK2-WT and TN mutant in cotransfected HEK 293T cells. Co-IP with anti-MYC was followed by anti-V5 immunoblotting. (H) Co-IP analysis of the interaction between flag-tagged CDGI-F1 domain and Myc-tagged LRRK2-WT and TN mutant in cotransfected HEK 293T cells. Co-IP with anti-MYC was followed by anti-flag immunoblotting. (I) Coimmunostaining of CDGI (green), LRRK2 (red), and DARPP32 (magenta) in mouse striatal sections. aa, amino acid.

CDGI acts as a GEF for LRRK2 to increase LRRK2 GTP binding and GDP release activity

Because CDGI strongly interacts with LRRK2, we next asked whether CDGI functions as a GEF for LRRK2. The steady-state GTP/GDP-loading status of LRRK2 with or without CDGI was evaluated by an in vivo 32P-orthophosphate labeling procedure (46). HEK 293T cells overexpressing MYC-tagged LRRK2 with or without V5-tagged CDGI coexpression were labeled with 32P-orthophosphate. LRRK2 protein was then purified by immunoprecipitation (IP), and LRRK2-associated GTP/GDP was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on polyethylenimine (PEI) cellulose plates. CDGI increased the GTP binding activity of LRRK2 (Fig. 2, A and B). The increase in GTP binding activity was substantially augmented to more than eightfold in the presence of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and the phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (TPA), which could stimulate CDGI GEF function in cells (Fig 2, A and B) (39). ARHGEF7 exhibited a milder effect of about 1.3-fold increase on LRRK2 GTP binding activity, and RanGEF (known as RCC1), a non-LRRK2 GEF, had minimal effects on LRRK2 GTP binding activity (Fig 2, A and B) (25, 39). These results suggest that CDGI increases LRRK2 GTP binding activity in cells.

Fig. 2. CDGI acts as a potential GEF for LRRK2 to increase LRRK2 GTP binding activity and GDP release.

(A) GTP loading analysis of LRRK2 by an in vivo 32P-orthophosphate labeling in HEK 293T cells overexpressing the indicated plasmids. The migration of GTP and GDP is indicated. The Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and TPA were applied. (B) Quantification of LRRK2 GTP binding activity by the ratio GTP to (GTP + GDP). (C) GTP loading analysis of LRRK2 R1441C (RC) and G2019S (GS) with CDG-WT or GW by an in vivo 32P-orthophosphate labeling in HEK 293T cells. TN (T1348N) was a negative control. (D) Quantification of LRRK2 GTP binding activity by the ratio GTP to (GTP + GDP). (E) The levels of LRRK2 bound to GTP were analyzed by pull-down assays with GTP-agarose from HEK 293T cells. (F) Quantification of LRRK2 bound to GTP-agarose beads. Data were normalized to LRRK2-WT alone in (B), (D), and (F). (G) GTP loading analysis of LRRK2 by an in vivo 32P-orthophosphate labeling in WT striatal neurons compared to CDGI KO neurons transduced by LV-CDGI-WT or LV-CDGI-GW. (H) Quantification of LRRK2 GTP binding activity by the ratio GTP to (GTP + GDP). Data were normalized to WT neurons. (I) A diagram of the guanine nucleotide exchange assay is illustrated. Free BODIPY-FL-GDP is quenched with a low fluorescence in the solutions while showing increased fluorescence upon binding to GTPases. GEF catalyzes the exchange of preloaded BODIPY-FL-GDP for GTP causing a decrease in fluorescence. (J) Recombinant LRRK2 preloaded with BODIPY-FL-GDP was incubated with recombinant GST-CDGI proteins in the presence of excess cold GTP. Nucleotide exchange on LRRK2 was monitored by the fluorescence intensity change with different concentrations of CDGI-WT every 36 s for 15 min. Data are the means ± SEM, n = 3. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. n.s., not statistically significant.

To investigate the impact of CDGI on the GTP binding activity of LRRK2 PD-associated familial mutations, CDGI was coexpressed with LRRK2-R1441C (RC), a PD mutant at the pathogenic hotspot of the LRRK2 ROC domain, or with LRRK2-G2019S (GS), the most prevalent PD pathogenic mutation in the LRRK2 kinase domain. GTP binding activity was analyzed by the in vivo labeling procedure as described above. CDGI increases LRRK2-RC and LRRK2-GS GTP binding activity as well but to a lesser content of about half of LRRK2-WT (Fig. 2, C and D). Moreover, a CDGI GEF–deficient mutation, CDGI-G248W (CDGI-GW) (47), markedly impaired CDGI nucleotide exchange activity and concomitantly failed to affect LRRK2 GTP binding activity (Fig. 2, C and D).

To confirm that CDGI functions as an LRRK2 GEF, we performed pull-down assays using GTP-agarose beads from HEK 293T cell extracts expressing MYC-LRRK2 with or without V5-CDGI in the presence of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and TPA. CDGI-WT expression increased the levels of GTP-bound LRRK2 to twofold (Fig. 2, E and F). The specificity of LRRK2 for binding to immobilized GTP was confirmed by control experiments using LRRK2-TN mutant. To ascertain whether CDGI functions as a physiological GEF for LRRK2, we performed GTP binding activity analysis on endogenous LRRK2 in CDGI WT and KO striatal neurons using an in vivo labeling procedure (Fig. 2, G and H) (46). Endogenous LRRK2 protein was labeled with 32P-orthophosphate and purified from CDGI WT and KO striatal neurons in the presence of the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and TPA. LRRK2-associated GTP/GDP was analyzed by TLC on PEI cellulose plates. In CDGI WT striatal neurons, we observed a significant increase of threefold GTP binding activity of LRRK2 compared to CDGI KO neurons. To confirm the specificity of the effects of CDGI on LRRK2, we performed a rescue experiment by transducing CDGI into CDGI KO neurons using lentiviruses expressing WT (LV-CDGI-WT) or mutant CDGI (LV-CDGI-GW). LV-CDGI-WT increased LRRK2 GTP binding activity in CDGI KO neurons but LV-CDGI-GW did not, implicating CDGI as a specific LRRK2 GEF.

It is well known that a GEF activates GTPases by stimulating the release of GDP to allow the binding of GTP. Thus, we examined whether CDGI can stimulate the dissociation of GDP from LRRK2. To this end, we evaluated the CDGI exchange activity of GDP to GTP toward LRRK2 in vitro. Purified recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–CDGI proteins were incubated with recombinant LRRK2 preloaded with a fluorescent analog of GDP, BODIPY-FL-GDP, in the presence of excess cold GTP. Free BODIPY-FL-GDP is quenched with a low fluorescence in the solutions while showing increased fluorescence upon binding to GTPase (Fig. 2I) (48). In this assay, nucleotide exchange on LRRK2 was monitored by the fluorescence intensity change with different concentrations of CDGI-WT.CDGI GEF–deficient mutation CDGI-GW was included to confirm the specificity of CDGI GEF function. As shown in Fig. 2J, upon incubation with a higher concentration at 200 nM CDGI-WT, the fluorescence of preloaded LRRK2 with BODIPY-FL-GDP was rapidly decreased to half in about 3 min, indicating the dissociation of preloaded BODIPY-FL-GDP from LRRK2 (Fig. 2J), while CDGI-GW does not have obvious effects on the GDP release (Fig. 2J). CDGI-WT can also dissociate GDP from LRRK2 at a lower concentration of 20 nM but at a slower speed (Fig. 2J). Together, these data suggest that CDGI is a physiological and specific GEF for LRRK2 and increases LRRK2 GDP to GTP exchange activity.

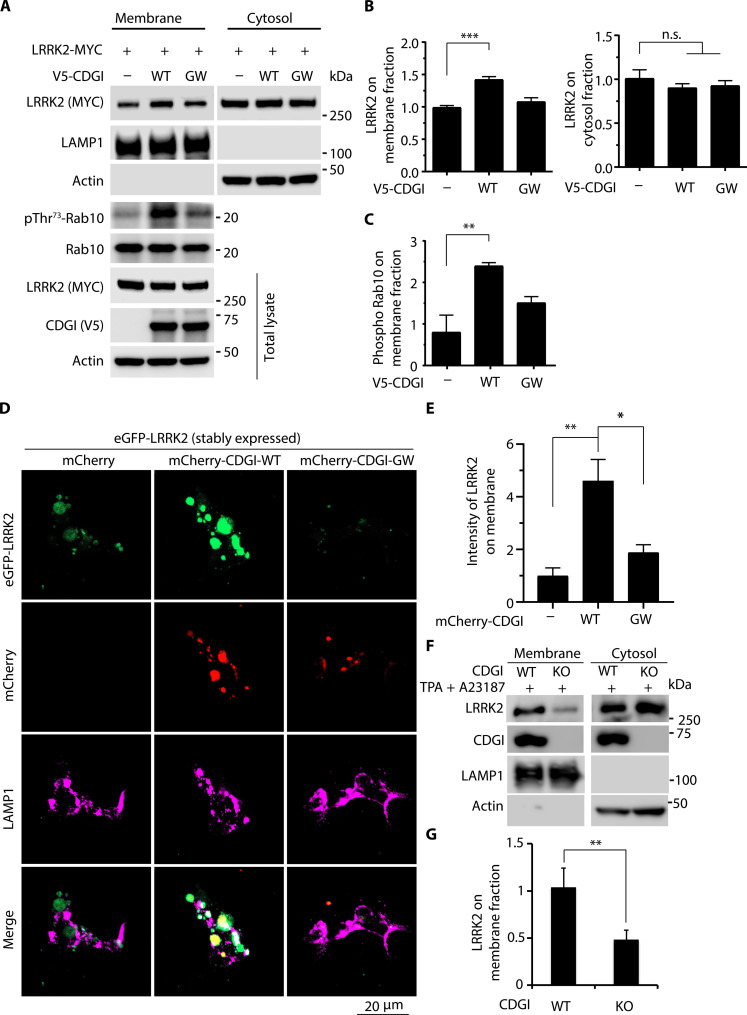

CDGI increases LRRK2 membrane association

It is known that GTP-bound small GTPases are stabilized at the membrane (49). Given our results demonstrating that CDGI increases LRRK2 GTP binding, we asked whether CDGI regulates LRRK2 membrane localization. LRRK2 localizes to both membrane and cytosol fractions (50). Cells coexpressing MYC-LRRK2 with V5-CDGI were fractionated into cytosolic and membrane fractions, and the abundance of soluble and membrane-associated LRRK2 was determined by Western blot (WB) analysis. The CDGI GEF–deficient mutant CDGI-GW was included as a control. CDGI coexpression potentiated LRRK2 membrane localization to 1.5-fold (Fig. 3, A and B). It has been reported that membrane recruitment appears to activate LRRK2 kinase activity (51–57). To further investigate whether CDGI increases LRRK2 membrane association and in turn activates LRRK2 kinase activity, we examined a well-known LRRK2 kinase substrate Rab10 phosphorylation (pRab10) levels. pRab10 level at T73 significantly increased about 2.5-fold in the membrane fraction with CDGI-WT (Fig. 3, A and C). To further confirm the membrane localization of LRRK2 with CDGI expression, cytosolic proteins were depleted using an established liquid nitrogen coverslip freeze-thaw method (23, 52, 58). With this method, we examined membrane-associated LRRK2. As shown in Fig. 3 (D and E), membrane-bound LRRK2 was increased about four to five times when overexpressing mCherry-CDGI-WT but not CDGI-GW in an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)–LRRK2 stable cell line. LAMP1 (lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1) was used as a lysosomal membrane marker. Membrane-bound LRRK2 was partially colocalized with LAMP1 (Fig. 3D). Given that LRRK2 has been reported to be recruited to damaged lysosomes (59, 60), this prompted us to further ask whether CDGI facilitates LRRK2 recruitment to damaged lysosomes. To this end, we treated eGFP-LRRK2 stable cells transfected with mCherry-CDGI-WT or GW with the lysosomal destabilizing agent LLOMe [l-leucyl-l-leucine methyl ester (hydrochloride)] that interacts with the lysosomal membrane and luminal hydrolases. Galectin-3 (Gal3) was used as the marker for damaged lysosomes. We found that overexpression of CDGI does not induce lysosomal membrane damage as indicated by minimal staining of Gal3 upon dimethyl sulfoxide treatment (fig. S1). However, upon LLOMe treatment, CDGI-WT does not significantly cause more LRRK2 on the enlarged lysosomes as shown by the colocalization of LRRK2 with LAMP1 in enlarged lysosomes (fig. S1). To determine whether CDGI regulated LRRK2 membrane association at the physiological level, CDGI-WT and CDGI-KO striatal neurons were fractionated in the presence of Ca2+ ionophore A23187 and TPA, and membrane fractions and the abundance of soluble and membrane-associated endogenous LRRK2 were determined by WB. Membrane-bound LRRK2 was increased about twofold in CDGI-WT neurons compared to CDGI-KO neurons (Fig. 3, F and G). These results suggest that the GEF activity of CDGI potentiates LRRK2 membrane localization.

Fig. 3. CDGI increases LRRK2 membrane association.

(A to C) Cellular fractionation assay of LRRK2 intensity on membrane and cytosol fractions in HEK 293T cells cotransfected with LRRK2 and CDGI-WT or GW. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and fractionated into cytosol and membrane fractions. Samples were immunoblotted with anti-MYC, V5, LAMP1, Rab10, and phosphor-Rab10. Data were normalized to LRRK2-MYC alone. (D and E) Liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw methods assessing LRRK2 membrane association. HEK 293T cells with stably expressed eGFP-LRRK2 were transfected with or without mCherry-CDGI. After 48 hours, cells were permeabilized by liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw to deplete cytosol and then fixed, immunostained with LAMP1, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 20 μM. Data were normalized to eGFP-LRRK2 stable cells transfected with mCherry. (F and G) Cellular fractionation assay of LRRK2 intensity on membrane and cytosol fractions in CDGI WT striatal neurons compared to CDGI KO neurons. CDGI WT and KO striatal neurons were treated with A23187 and TPA before being harvested and fractionated into cytosol and membrane fractions. Data were normalized to CDGI-WT neurons. Data are the means ± SEM, n = 3. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for the data analysis of multiple comparisons, and Student’s t tests (unpaired, two-tailed) were used for the data analysis of two comparisons. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate retinal neurodegeneration

Given the similar expression pattern of LRRK2 and CDGI in the striatonigral pathway (39–45) and the critical role of LRRK2 in neurodegeneration, the interaction of LRRK2 and CDGI was studied in vivo by investigating the effects of CDGI- on LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration in intact organisms. We first used a LRRK2 Drosophila model to assess the effects of CDGI on LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration. We expressed UAS-LRRK2-WT (LRRK2WT), GS (LRRK2GS), RC (LRRK2RC), or UAS-dLRRK RNAi (dLRRKRI) with UAS-CDGI-WT (CDGIWT) or GW (CDGIGW) in fly eyes, driven by glass multiple reporter (GMR)–GAL4. Retinal degeneration as assessed by eye morphology was monitored by light microscopy (Fig. 4A) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Fig. 4B). Unexpectedly, expression of CDGI-WT alone led to a profound small and rough eye phenotype (Fig. 4, b and b′), which could be partially rescued to a bigger and smoother eye phenotype by the knockdown of fly endogenous dLRRK (dLRRKRI) (Fig. 4, b versus e, b′ versus e′, and C). Coexpression of LRRK2-WT, GS, or RC mutant with CDGI-WT did not have significant effects on the CDGI-WT–induced eye phenotype (Fig. 4, h, k, n, h′, k′, n′, and C). Expression of the GEF-deficient mutant CDGI-GW alone did not induce an obvious eye phenotype (Fig. 4, c, f, i, l, o, c′, f′, i′, l′, o′, and C), and expression of LRRK2 mutants (dLRRKRI, LRRK2WT, LRRK2GS, or LRRK2RC) also did not induce an obvious eye phenotype (Fig. 4, d, g, j, m, d′, g′, j′, m′, and C). These findings suggest that CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 through its GEF function to regulate retinal neurodegeneration.

Fig. 4. CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate retinal neurodegeneration.

(A) Representative images of eye morphology of 1-week-old flies of the indicated genotypes by light microscopy. Drosophila LRRK2 (dLRRK) RNAi knockdown (dLRRKRI), human LRRK2 WT (LRRK2WT), and LRRK2 mutant GS or RC (LRRK2GS or LRRK2RC) were coexpressed with human CDGI WT (CDGIWT) or CDGI-GW (CDGIGW) in fly eyes by a GMR-GAL4 driver (GMR > CDGI/LRRK2). For each genotype, images were taken from at least 10 flies. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Representative images of eye morphology of 1-week-old flies of the indicated genotypes by SEM. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) The fly eye size was quantified by ImageJ for each genotype. n = 10. Data are mean ± SEM, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ****P < 0.0001.

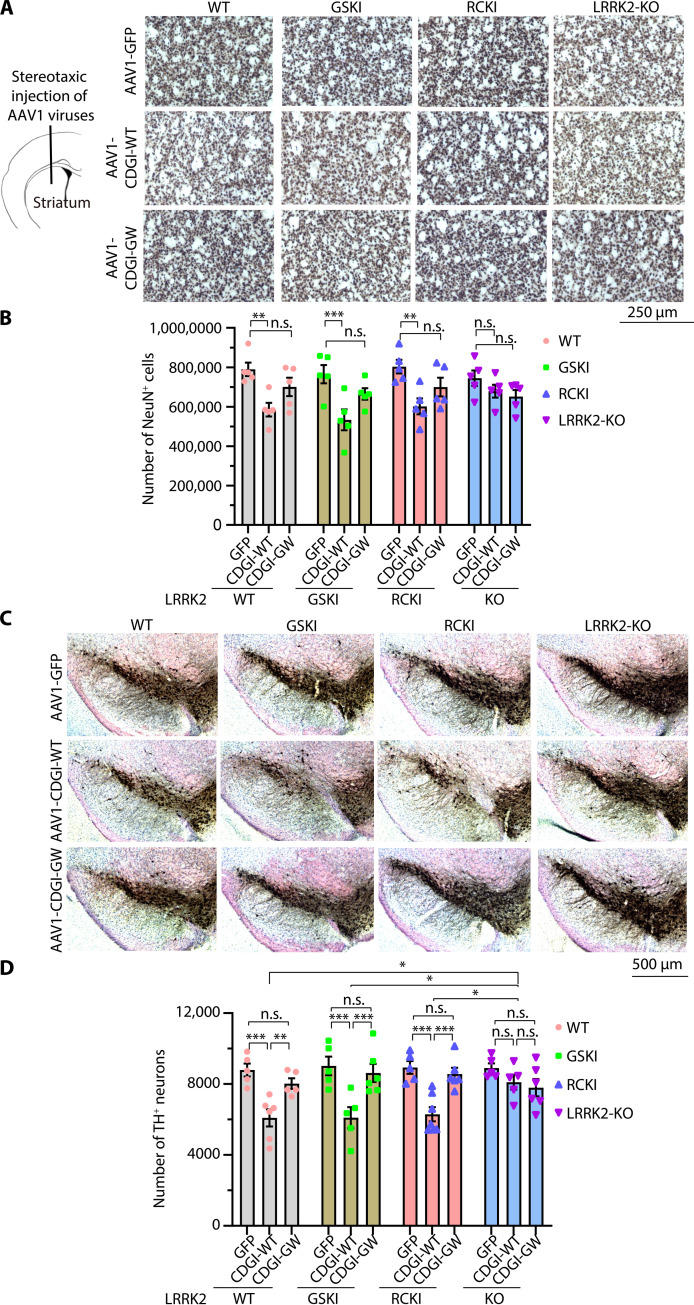

CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate striatal and DA neurodegeneration

To further determine whether CDGI regulates endogenous LRRK2 function in vivo in mammals, the effect of adeno-associated virus (AAV) overexpression of CDGI-WT and the GEF-deficient mutant CDGI-GW was evaluated in LRRK2 knock-in (KI) mice. To establish whether CDGI acts specifically through LRRK2, LRRK2 KO mice were used as controls. Given that both LRRK2 and CDGI are enriched in the striatum, AAV1 carrying CDGI-WT or GW (AAV1-CDGI-WT or GW) with a GFP tag and control viruses (AAV1-GFP) were stereotactically injected into the mouse striatum of WT, LRRK2-GSKI, RCKI, and KO mice at 10 months of age, and striatal pathology was assessed. Two doses of AAV were deposited ventrally along one needle tract at the same rostrocaudal coordinates. We determined the expression efficiency of AAV1-GFP, AAV1-CDGI-WT-GFP, and AAV1-CDGI-GW-GFP 1 month after the stereotaxic injections (fig. S2). Fluorescent images and WB analysis of striatal extracts showed robust and widespread expression of CDGI in the striatum (fig. S2, A and B). GFP signal was also found in the substantia nigra (SN) with very strong signals in the pars reticulata fibers (SNpr) and weaker signals in the pars compacta (SNpc) cell bodies (fig. S2C), indicating retrograde transduction of SN neurons after striatal viral delivery. We did not observe notable pathology 3 months after the AAV injection; thus, the mice were aged 9 to 10 months after the viral injection. Neurodegeneration in the striatum was assessed by counting neurons in the striatum by immunolabeling with NeuN (neuronal nuclei), a neuronal-specific marker for the majority of medium-sized output projection neurons and interneuron subtypes in the striatum. The number of NeuN-positive neurons was significantly decreased by about 25% in WT mice injected with AAV1-CDGI-WT, but not with AAV1-CDGI-GW (Fig. 5, A and B). A similar decrease was also observed in LRRK2-GSKI and RCKI mice injected with AAV1-CDGI-WT but not with AAV1-CDGI-GW (Fig. 5, A and B). No substantial changes of NeuN-positive neuron numbers were observed in LRRK2-KO mice injected with either AAV1-CDGI-WT or AAV1-CDGI-GW (Fig. 5, A and B).

Fig. 5. CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate striatal and DA neurodegeneration.

(A) Representative images of NeuN staining of mouse striatum. Ten-month-old WT, LRRK2 GSKI, RCKI, and KO mice were injected with AAV1-CDGI-WT or GW into the striatum. After 9 to 10 months of viral injection, the striatal neurons were immunolabeled by a NeuN antibody. Scale bar, 250 μm. (B) Quantification of NeuN-positive neurons in the striatum using an unbiased stereological method with stereo investigator software from five animals per group. (C) Representative images of DA neuron staining in mouse SNpc. After 9 to 10 months of viral injection, the DA neurons were immunolabeled by a TH antibody. Scale bar, 500 μm. (D) Quantification of TH-positive neurons in SNpc using an unbiased stereological method with stereo investigator software from five to seven animals per group. Data are mean ± SEM, two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

CDGI has a similar low to undetectable expression pattern in the SNpc as LRRK2 (39–45, 61, 62). However, LRRK2 mutations cause dopamine (DA) neurodegeneration in the SNpc. AAVs can be retrogradely transported to DA neurons at SNpc after striatal delivery. AAV1 carried GFP, CDG1-WT-GFP, and CDGI-GW-GFP expression was observed in both SNpr fibers and SNpc cell bodies, although the signal in SNpc cell bodies was much weaker (fig. S2C), Accordingly, the total number of DA neurons in SNpc was monitored at 9 to 10 months after the viral injection. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)–positive neurons were counted using unbiased stereology. There was a ~25% TH neuronal loss following AAV1-CDGI-WT injections into WT, LRRK2-GSKI, or RCKI mice. No significant changes were observed following the AAV1-CDGI-GW injections (Fig. 5, C and D). The AAV1-CDGI-WT injection did not significantly induce TH neuronal loss in LRRK2-KO mice. The density of TH-positive DA nerve terminals in the striatum (63) was also monitored. AAV1-CDGI-WT injection into WT, LRRK2-GSKI, or RCKI mice showed a similar trend to cause the loss of DA nerve terminals but did not reach statistical significance (fig. S3). No changes were observed with an injection of AAV1-CDGI-GW in the different LRRK2 mouse groups (fig. S3). Together, these results suggest that overexpression of CDGI induces striatal and SNpc DA neurodegeneration through its GEF activity on LRRK2.

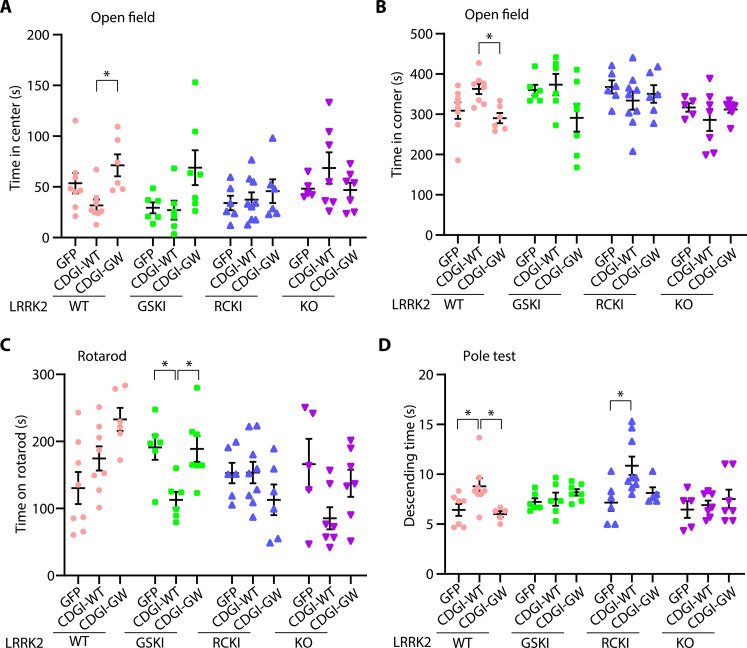

CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate locomotor behavioral deficits

Lesions of the striatal and DA systems in mice have been linked to a variety of behavioral phenotypes (64–67). Open field, rotarod, and pole tests were performed to assess the motor function in AAV-injected mice. In the open field test, AAV1-CDGI-WT–injected LRRK2 WT mice spent significantly less time in the center and more time in the corner compared to AAV1-GFP–or AAV1-CDGI-GW–injected LRRK2-WT mice (Fig. 6, A and B). In the rotarod test, the mean staying time on the accelerating rotarod of AAV1-CDGI-WT–injected LRRK2 GSKI mice was significantly shorter compared to AAV1-GFP–or AAV1-CDGI-GW–injected LRRK2-GSKI mice (Fig. 6C). Other injected mice did not show significant deficits in the rotarod test. The DA-sensitive pole test is a widely used test to assess basal ganglia-related movement disorders in mice (68). The pole test monitors the ability of the mouse to grasp and maneuver on a pole to descend to its home cage. AAV1-CDGI-WT–injected LRRK2 WT and RCKI mice exhibited deficits in climbing down the pole by spending significantly more time on the pole (Fig. 6D). Other injected mice did not show notable deficits in the pole test. Together, these results indicate that CDGI induces DA-sensitive locomotor behavioral deficits in LRRK2 WT and mutant mice but not in LRRK2-KO mice and CDGI-GW–injected mice. The LRRK2 GSKI and RCKI mutants exhibited different sensitivity on the behavioral tests. These data suggest that CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate locomotor behavioral deficits.

Fig. 6. CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate locomotor behavioral deficits.

Ten-month-old WT, LRRK2 GSKI, RCKI, and KO mice were injected with AAV1-CDGI-WT or GW into the striatum. After 9 to 10 months of viral injection, a battery of behavioral tests was performed. (A) Open-field test. The total time spent at the center was analyzed. (B) Open-field test. The total time spent at the corner was analyzed. (C) Rotarod test. The average retention time was analyzed. (D) Pole test to monitor behavioral abnormalities. The total time to descend to the bottom was recorded. Data are mean ± SEM, n = 5 to 9 per group, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

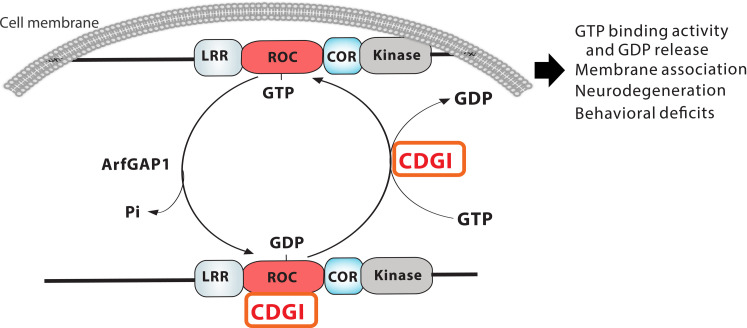

This study identified CDGI as a physiological GEF for LRRK2 that regulates LRRK2 GDP/GTP exchange activity and cellular function. CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate retinal neurodegeneration in Drosophila and striatal and DA neuron degeneration accompanying with behavioral deficits in mice (Fig. 7, the model). These observations provide a further understanding of the LRRK2 GTPase function and suggest that the LRRK2 GTPase function is regulated by the GEF activity of CDGI.

Fig. 7. Model of CDGI regulation of LRRK2 function and LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration.

LRRK2 GTPase cycle is between inactive off GDP-bound state and active on GTP-bound state. CDGI binds to LRRK2 serving as a physiological GEF for LRRK2 to increase LRRK2 GTP binding activity and GDP release, and membrane association and in turn regulates LRRK2-induced striatal and DA neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits.

LRRK2 is a GTPase, and its GTPase activity plays a key role in the pathobiology of LRRK2-mediated neurodegeneration (5, 6, 69–71). Our findings indicate that the LRRK2 GTPase cycle is a canonical G-protein cycle that requires GAPs and GEFs. On the other hand, on the basis of a study from the bacteria C. tepidum and Methanosarcina barkeri protein with a Roc-COR structure (36), the LRRK2 G-protein cycle was proposed to be a GAD cycle where dimerization was proposed to be mediated by the two COR domains that position the GTPase domains in close proximity and thereby lead to exchange via an arginine residue (36). However, this key active site arginine residue does not exist in human LRRK2. In addition, a feature of GADs is that GTP will enhance the dimerization, while GDP will weaken the dimerization. However, the bacterial Roco protein is mainly dimeric in the nucleotide-free and GDG-bound states which it forms monomers upon GTP binding (72). The GAD model is also in contrast to the mammalian LRRK2. The LRRK2 GTPase-COR dimerization was not enhanced by GTP or GTPγS in a LRRK2 GTPase-COR self-binding assay (73). Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that the isolated GTPase domain of LRRK2 is catalytically active in its monomeric form, suggesting that dimerization is not required for LRRK2 GTPase activity (37, 74). Thus, the LRRK2 G-protein cycle is not compatible with the GAD model. On the other hand, studies using human LRRK2 proteins suggest that LRRK2’s GTPase activity requires both GAPs and GEFs due to the low intrinsic catalytic activity but high-affinity binding of GTP/GDP (37, 38). Consistent with this notion is that ArfGAP1 functions as a GAP candidate for LRRK2 where it regulates LRRK2 GTPase hydrolysis and toxicity, while it is reciprocally regulated by LRRK2’s kinase activity (7, 27). The RGS2 GAP also regulates LRRK2 GTP hydrolysis and protects against LRRK2 mutant–induced neurite shortening and neuronal toxicity (26). Another study identified an interaction of LRRK2 with ARHGEF7 (25). Intriguingly, this study showed that ARHGEF7 increases both LRRK2 GTP binding activity and GTP hydrolysis, which suggests that ARHGEF7 has both LRRK2 GEF and GAP functions. Thus, it is not clear whether ARHGEF7 is a GEF or GAP for LRRK2. Further studies are required to answer this question.

We found that CDGI physically interacts with LRRK2 and increases LRRK2 GTP binding activity via in vivo labeling in cell cultures and primary striatal neurons. Consistent with the notion that GTP-bound small GTPases are stabilized at the membrane (49), CDGI enhances LRRK2 membrane association and pRab10 by LRRK2. All these phenomena can be enhanced by calcium, which suggests that calcium-related signaling could be important in LRRK2-associated PD (75–80). We found that CDGI acts upstream of LRRK2 to regulate neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits. Striatal delivery of CDGI induces both striatal and SNpc DA neurodegeneration. The SNpc DA neurodegeneration could result from both retrograde transduction of CDGI overexpression in SNpc neuronal cell bodies and the loss of striatonigral input. However, a similar trend caused the loss of DA nerve terminals but did not reach statistical significance, suggesting a compensatory resprouting of the remaining DA axonal processes, a compensatory up-regulation of TH expression or increased DA release from remaining terminals, or the intact projections from the ventral tegmental area diluting the effects of the loss of SNpc DA neurons (81, 82). All this evidence suggests that CDGI acts as a potential physiological GEF for LRRK2. Thus, the LRRK2 G-protein cycle is regulated by the GAP candidates, ArfGAP1 and RGS2, and the GEF, CDGI.

CDGI and LRRK2 both are highly enriched in the striatum and have very low expression levels in the SNpc (39–45, 61, 62). The physiological role of LRRK2 in the striatum remains largely unknown. The LRRK2 protein is first detected at postnatal day 8 (P8) in striosomes and is detectable by P16 in the matrix compartment of the striatum where CDGI is enriched (61). In transgenic WT or R1441C LRRK2 mice, LRRK2 expression increases in the matrix area, compared to nontransgenic animals (61). Thus, PD-associated mutations of LRRK2 may increase the interaction of LRRK2 with CDGI within the matrix, thereby enhancing neurodegeneration. In a similar manner, an increase of CDGI in the striatum would enhance LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits, which is consistent with what we observed in this study. CDGI may regulate neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease where overexpression of CDGI exacerbates the toxic effects of mutant Htt, while the knockdown of CDGI expression is neuroprotective in a brain slice model of HD (83). In a rat model of L-DOPA (levodopa) –induced dyskinesia, CDGI is down-regulated (84). It has been reported that inhibition of LRRK2 induces a significant increase in the dyskinetic score in L-DOPA–treated parkinsonian animals (85). Both down-regulated CDGI and LRRK2 inhibition in L-DOPA–induced dyskinesia could cause a decreased interaction between CDGI and LRRK2. Since striatal DA inputs are differentially regulated in the matrix and striosome (86), it will be important in future studies to explore the interaction of LRRK2 with CDGI, in the neurophysiology and signaling within the matrix and striosomal compartments.

We observed that the LRRK2 GSKI and RCKI mutant mice with AAV-CDGI injection exhibited different sensitivity on the behavioral tests. Divergent effects of GS and RC LRRK2 mutants on downstream pathways including its kinase substrates have been reported (19, 87). We speculate that CDGI as an upstream regulator increases both GS and RC mutant GTP binding activity of LRRK2 and, in turn, activates divergent downstream pathways including LRRK2 kinase activity and its substrates. These divergent effects on downstream pathways ultimately converge on the different responses to the behavioral tests. The exact underlying mechanisms need further investigation.

Some limitations of our work should be investigated in future studies. First, while we demonstrated that LRRK2 and CDGI physically interact and colocalize in striatal SPNs, where the two proteins colocalize at the subcellular level, and whether CDGI facilitates LRRK2 subcellular membrane recruitment are not clear. Super-resolution microscopy or correlative light-electron microscopy studies could help address these questions. Second, it would be important to explore whether and how the interaction of LRRK2 with CDGI within the matrix and striosomes may play a role in disease progression, and whether the interaction is tissue or cell type specific. Third, exploration of how CDGI interaction with LRRK2 GAP candidates orchestrates LRRK2 GTPase function and downstream signaling and the interplay with different LRRK2 mutations would be important. Last, whereas striatal delivery of CDGI induces DA neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits in LRRK2 mutant mice, it would be important to investigate whether these deficits could be rescued by L-DOPA treatment.

Collectively, this study provides evidence that LRRK2’s GTPase activity requires GAPs and GEFs and opens the possibility that the GTPase, GAP, or GEF activities could serve as therapeutic targets for neurodegeneration induced by LRRK2, which is distinct from the direct inhibition of LRRK2 kinase activity or expression levels (88, 89). Here, we demonstrate that the striatum-enriched CDGI could have an important and even determining role in these mechanisms and itself could be a therapeutic target.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

LRRK2 GSKI mice were purchased from Taconic (13940) (90). LRRK2 KO (16121) and LRRK2 RCKI (009346) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (91). CDGI KO mice were from the Graybiel Laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (92). Mice were housed and treated in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of UConn Health (approval no. AP-201000-0826). Animals were housed in a 12-hour dark and light cycle with free access to water and food.

Plasmids

The entry clones carrying human CDGI, RCC1, and ARHGEF7 full-length cDNA were obtained from DNASU plasmid repository (clones HsCD00351718, HsCD00042446, and HsCD00514629). Human CDGI, RCC1, and ARHGEF7 full-length cDNA were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1-3flag-DEST or pcDNA3.1-nV5-DEST (Invitrogen) or pUASTattB-3HA-DEST by Gateway Technology. LRRK2-WT-MYC was from the Dawson lab (Addgene plasmid #17609) (11). CDGI domain fragments (F1, F2, and F3) were cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector with an C-terminal flag tag. Full-length CDGI-WT and GW mutants were cloned into pFUGW or pAAV/CBA-WPRE-bGHpA vectors. Truncated mutants for human LRRK2 were cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 with three flag tags at the N terminus as described previously (7, 23).

Primer sequences

The primer sequences are as follows: CDG1-F1-F: CCAGGTCGACACATGGCGAGCACTCTGGAC; CDG1-F1-R: CCAGGCGGCCGCTTACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCGGTGGGGCTGGTGGGCGA; CDG1-F2-F: CCAGGTCGACATGTCGCCCACC-AGCCCCACC; CDG1-F2-R: CCAGGCGGCCGCTTACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCCATGCGGCCTCCCAGCAC; CDG1-F3-F: CCAGGTCGACATGGTGCTGGGAGGCCGCATG; CDG1-F3-R: CCAGGCGGCCGCTTACTTATCGTCGTCATCCTTGTAATCTAAGTGGATGTCGAACACACCATC; CDGI-G248W (GW)-F: CACGCTGATGGCAGTGGTCTGGG-GCCTGAGCCACAGCTCC; CDGI-G248W (GW)-R: GGAGCTGTGGCTCAGGCCCCAGACCACTGCCATCAGCGTG; pFUGW-CDGI-F: CCAGGGATCCGCCACCATGGCGAGCACTCTGGAC; pFUGW-CDGI-R: ATTCCACCGGTTCTAAGTGGATGTCGAACACACCATC; AAV1-CDGI-F: CCGCTCG-AGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG; AAV1-CDGI-R: CAGGATATCTTACAAGTGGATGTCAAACACCCC.

Antibodies and reagents

Rabbit anti-CDG1 (Graybiel Laboratory), rabbit anti-RasGRP2 (ab137608, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-LRRK2 (clone N138/6, University of California Davis/NIH NeuroMab facility), rabbit monoclonal anti-LRRK2 (D18E12, #13046, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit monoclonal anti-LRRK2 (c41-2, ab133474, Abcam), rabbit anti-TH polyclonal antibody (NB300-109, Novus Biologicals), mouse anti-NeuN (ABN78, Millipore Sigma), rat anti-DARPP32 (MAB4230SP, R&D), mouse anti-EEA1 (68065-1-Ig, Proteintech), sheep anti-TGN46 (AHP500GT, Bio-Rad), rat anti-LAMP1 [D4B, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)], mouse monoclonal anti-LAMP1 (clone H4A3, DSHB), rabbit anti-LAMP1 (ab24170, Abcam), mouse anti-KDEL (NBP1-97469, Novus), rat anti-Mac2 (Gal3) (125401, BioLegend), mouse monoclonal anti-V5 antibody (R96025, Thermo Fisher Scientific), mouse monoclonal anti-MYC (M4439, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti–V5–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (V2260, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti-Flag (F3165, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti–Flag-HRP (A8592, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti–hemagglutinin (HA; H3663, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti–HA-HRP (H6533, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse monoclonal anti-ACTIN (A2066, Sigma-Aldrich), HRP-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; 111-035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch), HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG (115-035-166, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (115-545-166, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG (111-545-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Alexa Fluor 405 anti-rat IgG (A48261, Thermo Fisher Scientific), Alexa Fluor 647 anti-rabbit IgG (A32733, Thermo Fisher Scientific), TPA (P8139, Sigma-Aldrich), A23187 (C7522, Sigma-Aldrich), LLOMe (16008, Cayman), Alexa Fluor 594 Tyramide Reagent (B40957, Thermo Fisher Scientific), BODIPY FL GDP (G22360, Thermo Fisher Scientific), GST tag recombinant human LRRK2 protein (PV4873, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell culture, transfections, and co-IP

HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfection with MYC-LRRK2 and flag or V5-tagged CDGI was performed with PolyJet (Signagen) as per the manufacturer’s introductions. After 48 hours, cells were washed by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) once and lysed in IP buffer [1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 1 mM EGTA, and 1× protease inhibitors (Pierce)] by rotating at 4°C for 1 hour. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants were then incubated with protein-G Dynabeads (Bio-Rad) precoated with anti-MYC, anti-flag, or anti-V5 antibodies followed by rotating overnight at 4°C. The Dynabeads were pelleted and stringently washed five times with IP buffer supplemented with 500 mM NaCl before the immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subjected to immunoblotting.

In vivo 32P-orthophosphate metabolic labeling of GTPase

LRRK2 was cotransfected with GEFs in 60-mm culture dishes in OPTI-MEM media. After 48 hours posttransfection, cells were switched to phosphate-free media and incubated for 30 min in the cell culture incubator followed by labeling with phosphate-free medium containing a 150-μCi 32Pi/60-mm dish for 4 hours or overnight. Ten micromolar A23187 or/and 1 μM TPA treatment was applied for 15 min before harvesting the cells. The cells were washed once with 5 ml ice-cold PBS before lysis buffer [(pH 7.5) 50 mM Hepes, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.05% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors] was added, and plates were maintained on ice for 30 min. Cell lysates were collected and spun for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for IP with antibody-coated Dynabeads for at least 1 hour to overnight. Beads were then washed four times with ice-cold wash buffer [50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.005% SDS]. Nucleotides bound to LRRK2 were released from the beads by denaturing the protein in 20 μl of elution buffer [2 mM EDTA, 1 mM GDP or GTP, 0.2% SDS, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] at 65°C for 5 min. PEI cellulose plates (20 cm by 20 cm) and a chromatography chamber saturated with 0.75 M KH2PO4 (pH 3.4) were used for the TLC separation of nucleotides. Ten-microliter samples were spotted (~0.5 μl at a time) onto plates at least 2 cm from the bottom and 1.5 cm apart under an air stream. The dry TLC plates were placed upright in the chamber and sealed until the solvent had ascended 70 to 100% up the PEI cellulose. The TLC plates were then removed from the chamber and air-dried and processed for autoradiography.

GTP binding assay

LRRK2 were cotransfected with CDGI-WT and GW mutant in 60-mm culture dishes in OPTI-MEM media. After 48 hours posttransfection, cells were pelleted and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer [1× PBS (pH 7.4), 1% NP-40, 1× phosphatase inhibitors, and 1× protease inhibitors (Pierce)] by rotating at 4°C for 1 hour, and lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 17,500g for 10 min at 4°C.Supernatants were incubated with 50 μl of GTP-agarose bead suspension (Sigma-Aldrich) by rotating at 4°C for 2 hours. The agarose beads were sequentially pelleted and washed twice in wash buffer [1× PBS (pH 7.4) and 1% Triton X-100] and twice with PBS alone. GTP-bound proteins were eluted into 50 μl of Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol. GTP-bound proteins or input controls (0.1% total lysate) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to WB analysis.

In vitro guanine nucleotide exchange assay

Nucleotide exchange on LRRK2 was measured using a fluorescence-based assay (48). The GST-tagged recombinant LRRK2 protein (200 nM) was preloaded with BODIPY-FL-GDP (G22360, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in exchange buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.2), 150 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% Triton X-100, and 2 mM EDTA] at room temperature for 1 hour. Loading of BODIPY-FL-GDP was stopped by adding 5 μl of MgCl2. To measure GDP release, preloaded LRRK2 with BODIPY-FL-GDP was quickly mixed with recombinant CDGI-WT at 20 or 200 nM or CDGI-GW at 200 nM in the exchange buffer plus 4 mM GTP and 2 mM MgCl2. Reactions were performed in a black 96-well plate. Real-time fluorescence data were measured every 36 s for 15 min monitoring BODIPY-FL fluorescence by excitation at 488 nm and emission at 535 nm using a microplate reader (BMG Labtech).

Subcellular fractionation

Cells were collected in fractionation buffer [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 1× protease inhibitors (Pierce)] and incubated on ice for 15 min followed by passing through a 27-gauge needle 10 times and leaving on ice for 20 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 8000g for 5 min. The resulting supernatant, which includes the cytoplasm and membrane fractions, was further centrifuged in an ultracentrifuge at 100,000g for 2 hours to produce the pellet (membrane fraction) and the supernatant (cytosol fraction).

Liquid nitrogen coverslip freeze-thaw protocol and immunocytochemistry

Liquid nitrogen coverslip freeze-thaw protocol to deplete cytosol was performed as previously described (23, 58). Briefly, EGFP-LRRK2 stably expressed HEK 293T cells were established by transfecting cells with pLenti-EGFP-LRRK2-Flag-2A-Puro and selected with puromycin (1.5 μg/ml). EGFP-LRRK2 cells were plated on poly-l-ornithine–coated coverslips and transfected with indicated mCherry-N1 and mCherry-CDGI plasmids. After 48 hours, cells were chilled on ice, washed twice with ice-cold PBS, and incubated in ice-cold glutamate buffer [25 mM KCl, 25 mM Hepes, (pH 7.4), 2.5 mM magnesium acetate, 5 mM EGTA, and 150 mM potassium glutamate]. The coverslips were then dipped in liquid nitrogen for 5 s and allowed to thaw for a few seconds, followed by gentle washes with ice-cold glutamate buffer and rehydration for 5 min in ice-cold PBS on ice. Cells were then fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min. Fixed cells were washed with PBS, blocked for 1 hour with PBS containing 5% goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100, then detected with rabbit anti-LAMP1 antibody followed by Alexa Fluor 647 anti-rabbit IgG antibody, and mounted onto slides using VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Imaging was conducted on a Zeiss confocal 800 microscope (Carl Zeiss). The intensity of membrane-associated fluorescence was quantified by ImageJ software (NIH) (93).

Preparations of lentiviral CDGI

The second-generation lentiviral packaging system was used to produce high-titer lentiviruses. Briefly, pFUGW-CDGI-eGFP or pFUGW-V5-CDGI lentiviral plasmids were transfected into HEK 293T cells along with viral packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G). After 48 hours, the culture media were collected, and viral particles were precipitated by centrifugation at 35,000g for 2 hours. Viral particles were resuspended into serum-free media and stored at −80°C.

Primary striatal neuronal cultures and endogenous LRRK2 GTPase assay

Primary striatal neuronal cultures were prepared from embryonic day 15 to 16 CDGI WT and KO fetal mice (5, 94). Briefly, striatum tissues were dissected and dissociated by trypsin (Invitrogen). The cells were seeded into 24-well plates precoated with poly-l-ornithine and were maintained in neurobasal media (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 supplement and l-glutamine. The glial cells were inhibited by adding 5-fluoro-20-deoxyuridine (30 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) at days in vitro 4. Lentiviruses carrying CDGI-WT or GW were transduced into CDGI KO striatal neurons. GTP loading of endogenous LRRK2 was analyzed by the in vivo 32P-orthophosphate labeling as described above.

Drosophila genetics

GMR-GAL4 (stock no. #8605) and dLRRK RNAi (stock no. #35249) fly lines were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center. pUAST-CDGI-WT (CDGIWT) and GW (CDGIGW) and pUAST-attB-LRRK2 RC (LRRK2RC) were microinjected into Drosophila embryos (BestGene Inc.). LRRK2 WT (LRRK2WT) and G2019S (LRRK2GS) fly lines were described in our previous studies (23, 88). The transgenic CDGI flies were crossed with flies carrying LRRK2 different forms. The resulting bigenic flies were crossed with GMR-GAL4 and therefore induced the coexpression of CDGI and LRRK2 different forms in fly eyes (GMR > CDGI/LRRK2). The fly eye size was quantified by ImageJ.

Scanning electron microscopy

SEM was performed on fly eyes at the Bioscience Electron Microscope Laboratory at the University of Connecticut.

Preparations of AAV1 carrying GFP, CDGI-WT-GFP, and CDGI-GW-GFP

CDGI-WT or GW was subcloned into an AAV1 expression plasmid (AAV/CBA-WPRE-bGHpA) under the control of a CBA (chicken β-actin) promoter and containing WPRE (woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element) and bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats. High-titer AAV viruses were commercially generated and purified at Viogene.

Intracranial stereotaxic injection

Ten-month-old WT, LRRK2 GSKI, RCKI, and KO mice were anesthetized by isoflurane gas supplemented with oxygen (0.5 liters/min). A ~1.5-cm incision was made midline on the scalp. Two doses of ventral deposits along one needle tract at the same rostrocaudal coordinate were delivered: anterioposterior = +0.5 mm from bregma; lateral = −2.0 mm from bregma; dorsoventral = −3 and -4 mm. One microliter of ~2 × 1013 GC/ml of AAV1-CDGI-WT or GW with a GFP tag and control viruses (AAV1-GFP) at each ventral deposit were injected at a rate of 0.2 μl/min using a Hamilton syringe with a 26-gauge blunt needle. After injection, the needle was in place for 5 min to minimize backflow. The wound was closed with a monofilament suture. We did not observe notable pathology 3 months after the AAV injection; thus, the mice were aged 9 to 10 months after the viral injection. After 9 to 10 months of viral injection, behavioral tests were performed followed by immunohistochemistry analysis of brain tissues.

Histology

Mice were anesthetized and perfused with 20 ml of ice-cold PBS and then 20 ml ice-cold 4% PFA/PBS. Brains were removed, fixed with 4% PFA at 4°C overnight, and then immersed in 30% sucrose solution for 24 hours for cryoprotection. Once saturated in sucrose, brains were flash-frozen on dry ice and sliced with a freezing microtome at 40 μm.

Immunohistochemistry

For colocalization of endogenous CDGI and LRRK2 in mouse striatum, 40-μm mouse brain slices were prepared from WT mice as described above. After antigen retrieval with 10 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.0) and 0.05% Tween 20 at 37°C for 30 min, the sections were washed three times in PBS for 10 min each time, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS. Since CDGI (rabbit anti-RasGRP2, ab137608, Abcam) and LRRK2 antibodies (rabbit monoclonal anti-LRRK2, c41-2, ab133474, Abcam) worked for immunohistochemistry are from the same species, we used Tyramide conjugates for one antibody. After blocking, the brain slices were incubated with rabbit anti-LRRK2 primary antibody at 1:104 dilution overnight at 4°C and then incubated with anti-rabbit-HRP second antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After three PBS washes, brain sections with LRRK2 staining were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 Tyramide Reagent (B40957, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 7 min. After three PBS washes, brain sections were incubated with rabbit anti-CDGI and rat anti-DARPP32 or mouse anti-EEA1, mouse anti-KDEL, sheep anti-TGN46, and rat anti-LAMP1 antibodies at 1:1000 dilution overnight at 4°C. After three PBS washes, brain sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor Cy5 anti-mouse IgG (or anti-rat-Cy5 and anti-sheep-Cy5) antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours. Brain sections were mounted onto slides using VECTASHIELD mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Imaging was conducted on a Zeiss confocal 800 microscope (Carl Zeiss).

For stereological cell counting, after 9 to 10 months of viral injection, 40-μm mouse brain slices were prepared as described above. After antigen retrieval, the brain slices were blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS, incubated with anti-TH primary antibody overnight at 4°C, and then treated with Biotin-SP goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody or Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG antibody at room temperature for 2 hours. After three PBS washes, brain sections with TH staining were incubated with avidin/biotinylated enzyme complex in PBS (Vector Laboratories, PK-6100) at room temperature for 45 min, washed with PBS, and stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, D4418). Sections at SNpc levels were counterstained with Nissl (0.09% thionin) after TH staining as previously described (95), dehydrated in 100% ethanol, and cleared in xylene (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by mounting with Cytoseal Mountant (Epredia, 83124).

Stereological cell counting

An unbiased stereological method was used to count TH-positive neurons in SNpc in a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope equipped with a color camera (MBF Bioscience) and stereo investigator software (MBF Bioscience). Counting regions were delineated using a 5× objective according to the mouse brain stereotaxic coordinates (96). The counting frame was 40 μm by 40 μm with a 200 μm by 200 μm grid size. TH-positive DA neurons were counted in a 63× oil-immersion objective at 20-μm thickness. Total cells were counted from eight serial sections per animal.

Behavioral tests

Open field test

Spontaneous locomotor and exploratory activities were assessed in a square white open field arena. Briefly, a mouse was placed in the center of the open field arena and allowed to explore the area for 10 min. The activities of the mouse were recorded by a computer-based video tracking system (ANY-maze software, San Diego Instruments, USA). Activity measures included distance traveled and time spent in corners versus the center of the arena.

Rotarod performance

Motor coordination of mice was measured as the retention time using a Five Lane Rota-Rod for Mouse (Med Associates, Georgia, VT) equipped with photobeams and a sensor to automatically detect mice that fell from the rotarod. Before testing, the mice were trained on the rotarod at 6 rpm for 60 s and allowed to rest for at least 30 min. The training occurred over three consecutive days and consisted of three test trials. On the day of the test, four mice were placed on separate rods, and the durations on the accelerating rods were recorded automatically by the software installed on a computer connected to the instrument. The setting of the rotarod was the following: start speed, 6 rpm; maximum speed, 56 rpm; acceleration interval, 30 s; acceleration step, 5 rpm; and the setting remained constant throughout all trials. The tests were evaluated in three sessions, and the average retention time and end (falling off) speed were recorded for each mouse. The retention time was used as an estimate of the motor coordination of the mice.

Pole test

The pole consisted of a 2.5-ft (0.762 m) metal rod with a 9-mm diameter that was wrapped with bandage gauze. Each mouse was placed 3 inches (7.62 cm) from the top of the pole facing head-up. The total time taken for each mouse to turn and reach the base of the pole was recorded. Before testing, the mice were trained for three consecutive days, and each training session consisted of three test trials. On the day of the test, mice were evaluated in three sessions with 1-hour intervals in between, and total times were recorded. Results were expressed in total time in seconds (63, 95).

Statistics

Quantitative values were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Data normalization is described in the figure legends. Student’s t test was used for two comparisons. One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. P ≤ 0.05 will be considered statistically significant. *P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. The number of mice proposed was justified by a power analysis of minimum power of 80% (G*Power). Our previous studies and preliminary data (63, 95) showed that no obvious difference was observed between male and female mice. Therefore, both male and female animals were assigned to groups by computer-generated randomization for evaluation. All in vivo studies were performed blinded.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge X. Hu and the Service Center for Neurobehavior at the Department of Neuroscience, UConn Health. We thank the Bioscience Electron Microscope Laboratory at the University of Connecticut for helping perform the EM study.

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by grants from NIH/NINDS R01 NS112506 (Y.X.), NIH/NIA K01 AG046366 award (Y.X.), William N. & Bernice E. Bumpus Foundation Innovation Awards (Y.X.), Parkinson’s Foundation Stanley Fahn Junior Faculty award PF-JFA-1934 (Y.X.), American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) research grant (Y.X.), UConn health Startup fund (Y.X.), NIH/NINDS P50 NS38377 (T.M.D. and V.L.D.), the JPB Foundation (T.M.D.), NIH/NIMH R01 MH060379 (A.M.G.), and Mr. Robert Buxton (A.M.G.). J.Y. was supported by grants from NIH/NIGMS R01 GM136904 and the National Science Foundation 2115690. We acknowledge the joint participation by the Adrienne Helis Malvin Medical Research Foundation and the Diana Helis Henry Medical Research Foundation through direct engagement in the continuous active conduct of medical research in conjunction with The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the Foundation’s Parkinson’s disease Programs. T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative diseases.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Q.L., J.Y., J.R.C., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X. Investigation: Q.L., B.H., N.G.L.G., S.C., G.M., J.Y., and Y.X. Formal analysis: Q.L., N.G.L.G., J.Y., and Y.X. Methodology: Q.L., B.H., J.Y., J.R.C., A.M.G., T.M.D, V.L.D., and Y.X. Validation: Q.L., B.H., D.Z., J.Y., and Y.X. Resources: X.-M.M., J.R.C., J.Y., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X. Writing—original draft: J.Y., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X. Writing—review and editing: Q.L., N.G.L.G., S.C., G.M., X.-M.M., J.R.C., J.Y., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X. Funding acquisition: J.Y., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X. Supervision: J.Y., A.M.G., T.M.D., V.L.D., and Y.X.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The CDGI-KO mice can be provided by A.M.G. pending scientific review and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for the CDGI-KO mice should be submitted to A.M.G.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Lees A. J., Hardy J., Revesz T., Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 373, 2055–2066 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panicker N., Ge P., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., The cell biology of Parkinson’s disease. J. Cell. Biol. 220, e202012095 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cookson M. R., The role of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 791–797 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mata I. F., Wedemeyer W. J., Farrer M. J., Taylor J. P., Gallo K. A., LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease: Protein domains and functional insights. Trends Neurosci. 29, 286–293 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong Y., Coombes C. E., Kilaru A., Li X., Gitler A. D., Bowers W. J., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Moore D. J., GTPase activity plays a key role in the pathobiology of LRRK2. PLOS Genet. 6, e1000902 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiong Y., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., LRRK2 GTPase dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1074–1079 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong Y., Yuan C., Chen R., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., ArfGAP1 is a GTPase activating protein for LRRK2: Reciprocal regulation of ArfGAP1 by LRRK2. J. Neurosci. 32, 3877–3886 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith W. W., Pei Z., Jiang H., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Ross C. A., Kinase activity of mutant LRRK2 mediates neuronal toxicity. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1231–1233 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West A. B., Ten years and counting: Moving leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 inhibitors to the clinic. Mov. Disord. 30, 180–189 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West A. B., Cookson M. R., Identification of bona-fide LRRK2 kinase substrates. Mov. Disord. 31, 1140–1141 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West A. B., Moore D. J., Biskup S., Bugayenko A., Smith W. W., Ross C. A., Dawson V. L., Dawson T. M., Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16842–16847 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arranz A. M., Delbroek L., Van Kolen K., Guimaraes M. R., Mandemakers W., Daneels G., Matta S., Calafate S., Shaban H., Baatsen P., De Bock P. J., Gevaert K., Vanden Berghe P., Verstreken P., De Strooper B., Moechars D., LRRK2 functions in synaptic vesicle endocytosis through a kinase-dependent mechanism. J. Cell. Sci. 128, 541–552 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belluzzi E., Gonnelli A., Cirnaru M. D., Marte A., Plotegher N., Russo I., Civiero L., Cogo S., Carrion M. P., Franchin C., Arrigoni G., Beltramini M., Bubacco L., Onofri F., Piccoli G., Greggio E., LRRK2 phosphorylates pre-synaptic N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion (NSF) protein enhancing its ATPase activity and SNARE complex disassembling rate. Mol. Neurodegener. 11, 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cookson M. R., LRRK2 pathways leading to neurodegeneration. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 15, 42 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daher J. P., Abdelmotilib H. A., Hu X., Volpicelli-Daley L. A., Moehle M. S., Fraser K. B., Needle E., Chen Y., Steyn S. J., Galatsis P., Hirst W. D., West A. B., Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) pharmacological inhibition abates alpha-synuclein gene-induced neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 19433–19444 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greggio E., Jain S., Kingsbury A., Bandopadhyay R., Lewis P., Kaganovich A., van der Brug M. P., Beilina A., Blackinton J., Thomas K. J., Ahmad R., Miller D. W., Kesavapany S., Singleton A., Lees A., Harvey R. J., Harvey K., Cookson M. R., Kinase activity is required for the toxic effects of mutant LRRK2/dardarin. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 329–341 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herzig M. C., Kolly C., Persohn E., Theil D., Schweizer T., Hafner T., Stemmelen C., Troxler T. J., Schmid P., Danner S., Schnell C. R., Mueller M., Kinzel B., Grevot A., Bolognani F., Stirn M., Kuhn R. R., Kaupmann K., van der Putten P. H., Rovelli G., Shimshek D. R., LRRK2 protein levels are determined by kinase function and are crucial for kidney and lung homeostasis in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4209–4223 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaleel M., Nichols R. J., Deak M., Campbell D. G., Gillardon F., Knebel A., Alessi D. R., LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin at threonine-558: Characterization of how Parkinson’s disease mutants affect kinase activity. Biochem. J. 405, 307–317 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steger M., Tonelli F., Ito G., Davies P., Trost M., Vetter M., Wachter S., Lorentzen E., Duddy G., Wilson S., Baptista M. A., Fiske B. K., Fell M. J., Morrow J. A., Reith A. D., Alessi D. R., Mann M., Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. eLife 5, e12813 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin I., Kim J. W., Lee B. D., Kang H. C., Xu J. C., Jia H., Stankowski J., Kim M. S., Zhong J., Kumar M., Andrabi S. A., Xiong Y., Dickson D. W., Wszolek Z. K., Pandey A., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., Ribosomal protein s15 phosphorylation mediates LRRK2 neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Cell 157, 472–485 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Maio R., Hoffman E. K., Rocha E. M., Keeney M. T., Sanders L. H., De Miranda B. R., Zharikov A., Van Laar A., Stepan A. F., Lanz T. A., Kofler J. K., Burton E. A., Alessi D. R., Hastings T. G., Greenamyre J. T., LRRK2 activation in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, eaar5429 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jennings D., Huntwork-Rodriguez S., Henry A. G., Sasaki J. C., Meisner R., Diaz D., Solanoy H., Wang X., Negrou E., Bondar V. V., Ghosh R., Maloney M. T., Propson N. E., Zhu Y., Maciuca R. D., Harris L., Kay A., LeWitt P., King T. A., Kern D., Ellenbogen A., Goodman I., Siderowf A., Aldred J., Omidvar O., Masoud S. T., Davis S. S., Arguello A., Estrada A. A., de Vicente J., Sweeney Z. K., Astarita G., Borin M. T., Wong B. K., Wong H., Nguyen H., Scearce-Levie K., Ho C., Troyer M. D., Preclinical and clinical evaluation of the LRRK2 inhibitor DNL201 for Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabj2658 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Q., Bautista-Gomez J., Higgins D. A., Yu J., Xiong Y., Dysregulation of the AP2M1 phosphorylation cycle by LRRK2 impairs endocytosis and leads to dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Sci. Signal. 14, eabg3555 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen M., Krainc D., LRRK2 phosphorylation of auxilin mediates synaptic defects in dopaminergic neurons from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5576–5581 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haebig K., Gloeckner C. J., Miralles M. G., Gillardon F., Schulte C., Riess O., Ueffing M., Biskup S., Bonin M., ARHGEF7 (Beta-PIX) acts as guanine nucleotide exchange factor for leucine-rich repeat kinase 2. PLOS ONE 5, e13762 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dusonchet J., Li H., Guillily M., Liu M., Stafa K., Derada Troletti C., Boon J. Y., Saha S., Glauser L., Mamais A., Citro A., Youmans K. L., Liu L., Schneider B. L., Aebischer P., Yue Z., Bandopadhyay R., Glicksman M. A., Moore D. J., Collins J. J., Wolozin B., A Parkinson’s disease gene regulatory network identifies the signaling protein RGS2 as a modulator of LRRK2 activity and neuronal toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 4887–4905 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stafa K., Trancikova A., Webber P. J., Glauser L., West A. B., Moore D. J., GTPase activity and neuronal toxicity of Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2 is regulated by ArfGAP1. PLOS Genet. 8, e1002526 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng X., Dzamko N., Prescott A., Davies P., Liu Q., Yang Q., Lee J. D., Patricelli M. P., Nomanbhoy T. K., Alessi D. R., Gray N. S., Characterization of a selective inhibitor of the Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 203–205 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weygant N., Qu D., Berry W. L., May R., Chandrakesan P., Owen D. B., Sureban S. M., Ali N., Janknecht R., Houchen C. W., Small molecule kinase inhibitor LRRK2-IN-1 demonstrates potent activity against colorectal and pancreatic cancer through inhibition of doublecortin-like kinase 1. Mol. Cancer 13, 103 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garofalo A. W., Adler M., Aubele D. L., Brigham E. F., Chian D., Franzini M., Goldbach E., Kwong G. T., Motter R., Probst G. D., Quinn K. P., Ruslim L., Sham H. L., Tam D., Tanaka P., Truong A. P., Ye X. M., Ren Z., Discovery of 4-alkylamino-7-aryl-3-cyanoquinoline LRRK2 kinase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 23, 1974–1977 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilligan P. J., Inhibitors of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2): Progress and promise for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 15, 927–938 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taymans J. M., Greggio E., LRRK2 kinase inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for parkinson’s disease, where do we stand? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 214–225 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park Y., Liao J., Hoang Q. Q., Roc, the G-domain of the Parkinson’s disease-associated protein LRRK2. Trends Biochem. Sci. 47, 1038–1047 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barr F., Lambright D. G., Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 22, 461–470 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gasper R., Meyer S., Gotthardt K., Sirajuddin M., Wittinghofer A., It takes two to tango: Regulation of G proteins by dimerization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 423–429 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gotthardt K., Weyand M., Kortholt A., Van Haastert P. J., Wittinghofer A., Structure of the Roc-COR domain tandem of C. tepidum, a prokaryotic homologue of the human LRRK2 Parkinson kinase. EMBO J. 27, 2239–2249 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao J., Wu C. X., Burlak C., Zhang S., Sahm H., Wang M., Zhang Z. Y., Vogel K. W., Federici M., Riddle S. M., Nichols R. J., Liu D., Cookson M. R., Stone T. A., Hoang Q. Q., Parkinson disease-associated mutation R1441H in LRRK2 prolongs the “active state” of its GTPase domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4055–4060 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mills R. D., Liang L. Y., Lio D. S., Mok Y. F., Mulhern T. D., Cao G., Griffin M., Kenche V., Culvenor J. G., Cheng H. C., The Roc-COR tandem domain of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) forms dimers and exhibits conventional Ras-like GTPase properties. J. Neurochem. 147, 409–428 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawasaki H., Springett G. M., Toki S., Canales J. J., Harlan P., Blumenstiel J. P., Chen E. J., Bany I. A., Mochizuki N., Ashbacher A., Matsuda M., Housman D. E., Graybiel A. M., A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13278–13283 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biskup S., Moore D. J., Celsi F., Higashi S., West A. B., Andrabi S. A., Kurkinen K., Yu S. W., Savitt J. M., Waldvogel H. J., Faull R. L., Emson P. C., Torp R., Ottersen O. P., Dawson T. M., Dawson V. L., Localization of LRRK2 to membranous and vesicular structures in mammalian brain. Ann. Neurol. 60, 557–569 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galter D., Westerlund M., Carmine A., Lindqvist E., Sydow O., Olson L., LRRK2 expression linked to dopamine-innervated areas. Ann. Neurol. 59, 714–719 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han B. S., Iacovitti L., Katano T., Hattori N., Seol W., Kim K. S., Expression of the LRRK2 gene in the midbrain dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra. Neurosci. Lett. 442, 190–194 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higashi S., Moore D. J., Colebrooke R. E., Biskup S., Dawson V. L., Arai H., Dawson T. M., Emson P. C., Expression and localization of Parkinson’s disease-associated leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 in the mouse brain. J. Neurochem. 100, 368–381 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melrose H., Lincoln S., Tyndall G., Dickson D., Farrer M., Anatomical localization of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 in mouse brain. Neuroscience 139, 791–794 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.West A. B., Cowell R. M., Daher J. P., Moehle M. S., Hinkle K. M., Melrose H. L., Standaert D. G., Volpicelli-Daley L. A., Differential LRRK2 expression in the cortex, striatum, and substantia nigra in transgenic and nontransgenic rodents. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 2465–2480 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castro A. F., Rebhun J. F., Quilliam L. A., Measuring Ras-family GTP levels in vivo—Running hot and cold. Methods 37, 190–196 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lozano M. L., Cook A., Bastida J. M., Paul D. S., Iruin G., Cid A. R., Adan-Pedroso R., Ramón González-Porras J., Hernández-Rivas J. M., Fletcher S. J., Johnson B., Morgan N., Ferrer-Marin F., Vicente V., Sondek J., Watson S. P., Bergmeier W., Rivera J., Novel mutations in RASGRP2, which encodes CalDAG-GEFI, abrogate Rap1 activation, causing platelet dysfunction. Blood 128, 1282–1289 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blaise A. M., Corcoran E. E., Wattenberg E. S., Zhang Y. L., Cottrell J. R., Koleske A. J., In vitro fluorescence assay to measure GDP/GTP exchange of guanine nucleotide exchange factors of Rho family GTPases. Biol. Methods Protoc. 7, bpad024 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nottingham R. M., Pfeffer S. R., Defining the boundaries: Rab GEFs and GAPs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14185–14186 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berger Z., Smith K. A., Lavoie M. J., Membrane localization of LRRK2 is associated with increased formation of the highly active LRRK2 dimer and changes in its phosphorylation. Biochemistry 49, 5511–5523 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu H., Tonelli F., Turk M., Prescott A., Alessi D. R., Sun J., Rab29-dependent asymmetrical activation of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2. Science 382, 1404–1411 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purlyte E., Dhekne H. S., Sarhan A. R., Gomez R., Lis P., Wightman M., Martinez T. N., Tonelli F., Pfeffer S. R., Alessi D. R., Rab29 activation of the Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2 kinase. EMBO J. 37, 1–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z., Bryant N., Kumaran R., Beilina A., Abeliovich A., Cookson M. R., West A. B., LRRK2 phosphorylates membrane-bound Rabs and is activated by GTP-bound Rab7L1 to promote recruitment to the trans-Golgi network. Hum. Mol. Genet. 27, 385–395 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacLeod D. A., Rhinn H., Kuwahara T., Zolin A., Di Paolo G., McCabe B. D., Marder K. S., Honig L. S., Clark L. N., Small S. A., Abeliovich A., RAB7L1 interacts with LRRK2 to modify intraneuronal protein sorting and Parkinson’s disease risk. Neuron 77, 425–439 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhekne H. S., Tonelli F., Yeshaw W. M., Chiang C. Y., Limouse C., Jaimon E., Purlyte E., Alessi D. R., Pfeffer S. R., Genome-wide screen reveals Rab12 GTPase as a critical activator of Parkinson’s disease-linked LRRK2 kinase. eLife 12, e87098 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang X., Bondar V. V., Davis O. B., Maloney M. T., Agam M., Chin M. Y., Cheuk-Nga Ho A., Ghosh R., Leto D. E., Joy D., Calvert M. E. K., Lewcock J. W., Di Paolo G., Thorne R. G., Sweeney Z. K., Henry A. G., Rab12 is a regulator of LRRK2 and its activation by damaged lysosomes. eLife 12, e87255 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unapanta A., Shavarebi F., Porath J., Shen Y., Balen C., Nguyen A., Tseng J., Leong W. S., Liu M., Lis P., Di Pietro S. M., Hiniker A., Endogenous Rab38 regulates LRRK2’s membrane recruitment and substrate Rab phosphorylation in melanocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 105192 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seaman M. N., Cargo-selective endosomal sorting for retrieval to the Golgi requires retromer. J. Cell. Biol. 165, 111–122 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonet-Ponce L., Beilina A., Williamson C. D., Lindberg E., Kluss J. H., Saez-Atienzar S., Landeck N., Kumaran R., Mamais A., Bleck C. K. E., Li Y., Cookson M. R., LRRK2 mediates tubulation and vesicle sorting from lysosomes. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb2454 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]