Abstract

This study examined the efficacy of a 2-year anxiety management intervention integrated with a reading intervention for struggling readers in upper-elementary grades on anxiety outcomes. The study randomly assigned 128 struggling readers to one of three conditions: (a) reading intervention with anxiety management intervention (RANX), (b) reading intervention with math fact practice, an attention control, (RMATH), and (c) business-as-usual comparison (BaU). Findings demonstrated promising results for students in the RANX condition, particularly compared with the BaU condition. However, findings were not always statistically significant suggesting the need for additional adequately powered trials. Secondary analyses among students beginning with average anxiety showed significant reductions in physical symptoms of anxiety at year 1 posttest favoring RANX over RMATH and BAU, as well as between RANX and BAU on reading anxiety at year 2 posttest. Among students beginning with elevated anxiety, significant reductions in social anxiety were found at year 2 posttest favoring RANX over RMATH and BaU. The findings underscore the promise of integrating anxiety management and reading interventions.

Keywords: Anxiety, Reading, School-based intervention

Introduction

Mental health concerns in youth are common, with approximately two in five youth in the U.S. meeting criteria for a mental health disorder at some point in their lives by age 18 (Bitsko et al., 2022). Due to a rise in mental health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association issued a joint declaration of a national emergency in youth mental health, and researchers and clinicians have called for an urgent response to the crisis (Shim et al., 2022). Mental health disorders more commonly affecting children include internalizing disorders such as mood and anxiety disorders, externalizing disorders such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use disorders, and eating disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Anxiety is the most common class of disorders reported by U.S. youth, with 31.9% reporting symptoms at or above the threshold for a diagnosis at some point in their lives (Merikangas et al., 2010b). Further, a recent meta-analysis found that the prevalence of youth anxiety globally doubled during the COVID-19 pandemic, with approximately 20% reporting clinically elevated anxiety (Racine et al., 2021). Even young children are affected by anxiety (see Grills and Ollendick (2013)); for example, among teenagers with an anxiety disorder, the median age of onset was 6 years old, younger than for other classes of disorders (Merikangas et al., 2010b).

Despite the high prevalence and early onset of anxiety, less than one-third of U.S. children ages 8–15 years with an anxiety disorder receive mental health treatment, a rate lower than among children with externalizing and mood disorders (Merikangas et al., 2010a). This appears to be especially pronounced among children below the age of 12 (Merikangas et al., 2010a) and low-income, uninsured, or racial/ethnic minoritized youth (Ghandour et al., 2019). In particular, Hispanic youth are less likely to receive treatment for an anxiety disorder compared with non-Hispanic white youth (Ghandour et al., 2019). Additionally, Merikangas and colleagues (2011) reported that Black and Hispanic youth were less likely than white non-Hispanic youth to receive mental health services for anxiety even when the disorder was severely distressing and/or impairing (Merikangas et al., 2011). Thus, there is a large unmet need for effective anxiety interventions for youth.

School‑Based Mental Health Interventions

In recent years, schools have increasingly been called on to help fill the gap between need and services by providing mental health treatment and supports to children. A meta-analysis examining U.S. youth mental health service utilization found that school-based services were the most commonly accessed, compared with outpatient, primary care, inpatient, child welfare, and juvenile justice services (Duong et al., 2021). There are many advantages to having schools provide mental health services; for example, schools can reach more children than can community sites, which require additional time, transportation, and cost for families to access (Salloum et al., 2016). School-based services are perceived as more accessible and acceptable to families, as they meet children where they are, do not require knowledge of mental health care systems, and do not require parents to spend additional time or money they may not have (Sanchez et al., 2018). School-based services may also be particularly effective at reaching low-income or racially minoritized youth who have historically not been as likely to receive mental health services provided in traditional medical settings (Ali et al., 2019). Schools are also uniquely positioned to widely screen children and identify who may be at risk for mental health problems (Humphrey & Wigelsworth, 2016; Moore et al., 2023).

However, school-based mental health services place additional responsibilities on teachers and administrators who are often already overburdened and may not have expertise in evidence-based mental health treatments (Eiraldi et al., 2015; Weist et al., 2012). Teacher preservice education programs typically do not address student mental health, leaving teachers to rely on in-service professional development to fill in this knowledge (Ohrt et al., 2020). Teachers report concerns about their own lack of training in mental health as a barrier to adequately supporting student mental health (O’Farrell et al., 2023). Further, schools may not receive the additional resources necessary to support the provision of evidence-based mental health interventions, which may require trainings or expert consultations (Eiraldi et al., 2015). School administrators and officials charged with selecting programs to implement also may not have adequate mental health training, and as a result, most school-based mental health programs delivered to children are not evidence-based, and some may even be harmful (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). Adding to the complexity, many districts have recently purchased programs that target broad social-emotional learning outcomes and that are intended for all students in a classroom (i.e., universal implementation; Sanchez et al., 2018). However, there is high variance in the quality of the evidence supporting social-emotional learning programs (Wigelsworth et al., 2022). Further, selective (provided to students at risk for mental health problems) and targeted (provided to students identified as having mental health problems) treatment programs have been found to be more effective than universal programs provided by educators to all students (Sanchez et al., 2018). Unfortunately, selective and targeted programs have had limited uptake in schools to date.

The efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as an intervention for youth anxiety has been extensively researched and compared to both waitlist and active controls, with results indicating that it is the most efficacious behavioral treatment for child anxiety producing no or minimal adverse effects (see Crowe and McKay (2017) and Grills and Ollendick (2013) for review). CBT for anxiety addresses three interrelated response systems: physiological reactions to a perceived threat (i.e., feelings), subjective sense of a lack of control and distorted information processing (i.e., cognitions), and excessive avoidance of a perceived threat (i.e., behaviors). In recent years, CBT-derived programs for anxiety have been adapted and delivered in schools (Chiu et al., 2013; Francis et al., 2021; Haugland et al., 2020; Ruocco et al., 2016). Further, a recent meta-analysis found that school-based interventions for anxiety that utilized CBT had significantly higher effect sizes than school-based interventions not grounded in CBT (Zhang et al., 2023). The current work builds on the successes of CBT for treating child anxiety by integrating commonly utilized cognitive-behavioral techniques into an academic intervention program designed for elementary school-aged struggling readers.

Associations Between Anxiety and Reading

There is now an extensive and growing literature demonstrating significant associations between reading difficulties and increased anxiety symptoms in youth (Francis et al., 2019; Grills et al., 2014, 2022; Grills-Taquechel et al., 2012, 2013; Nelson & Harwood, 2011; Taboada Barber et al., 2022). Anxiety is a broad construct which may refer to a general trait-level construct or specific subtypes (e.g., social anxiety, reading anxiety); and studies have revealed associations with both broad and specific forms of anxiety with poorer reading. For example, Carroll et al. (2005) found that poorer reading was associated with elevations in separation anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder symptoms, whereas Macdonald et al. (2021) found that reading anxiety made unique contributions to reading comprehension. Findings linking reading-specific anxiety with reading achievement are similar to that found with math anxiety, in which domain-specific math anxiety seems to be more strongly associated with math achievement than is general anxiety (Carey et al., 2017). The associations may also differ by the subtype of anxiety or domain of reading being explored. For instance, Grills-Taquechel et al. (2012) found that reading fluency at the beginning of the school year negatively predicted separation anxiety at the end of the school year in first grade students. However, the same study also found that harm avoidance, a facet of anxiety related to perfectionism, was positively associated with reading achievement, indicating the importance of differentiating sub-types when examining anxiety (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2012; Grills et al., 2014). These associations were recently replicated by Grills and colleagues (2022), who also found that students who exhibited persistent reading difficulties across the academic year also reported significantly greater distress. Finally, Francis et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis of studies focused on reading and anxiety revealed a significant effect (d = 0.41). Taken together, findings such as these have suggested that the associations between anxiety and reading can be bi-directional, with reading abilities influencing later anxiety levels and anxiety levels influencing later reading-related performance (Grills et al., 2022; Grills-Taquechel et al., 2012; Ramirez et al., 2019). Anxiety has been proposed to impact academic achievement by influencing mediating factors such as attentional control, self-regulated learning, motivation, and reading engagement (Barnes et al., 2023; Mega et al., 2014; Taboada Barber et al., 2022). Repeated failure experiences in reading have also been suggested to increase anxiety over time (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2012).

Overall, the literature on anxiety and reading has consistently supported an association between these domains, with subtypes of anxiety differentially associated with reading outcomes. Findings also suggest that anxiety difficulties may be creating an additional barrier for success among struggling readers. Given the bi-directional relations, it may be most beneficial to target anxiety management alongside reading skills for struggling readers. The current study presents findings from a 2-year intervention that intended to do just this, by integrating evidence-based practices for anxiety management with those for reading, the program aimed to reduce anxiety and augment reading outcomes. Students in this 2-year study were assigned to one of three conditions: (a) small-group reading intervention with anxiety management instruction (RANX), (b) small-group reading intervention with math fact practice (RMATH), or (c) business-as-usual comparison condition (BaU). Preliminary findings specific to the primary reading outcomes have been reported previously (Vaughn et al., 2021). Overall, these findings were promising with students from the RANX condition making significantly greater gains on a measure of reading comprehension. In addition, students in RANX who reported lower reading anxiety levels prior to intervention also showed greater gains on word reading.

The present paper focuses on findings regarding the program’s efficacy at reducing anxiety in struggling readers. Reading intervention effects were reported separately as we were anticipating that we would be able to collect additional follow-up data on the anxiety measures for the participants. However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting school closures, we were unable to finalize further data collection on this cohort and are thus reporting outcomes for anxiety in this paper. We hypothesized that students who received the RANX treatment would show lower levels of anxiety than students in the RMATH and BaU conditions. We anticipated a pattern of positive effects would occur across subtypes of anxiety (i.e., general trait-level anxiety, physical symptoms of anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, and reading anxiety), though we considered the outcomes may be largest on comparison between RANX and BAU. We hypothesized that children with average anxiety at the start of the intervention would show greater response to instruction on anxiety outcomes as clinical research has found that lower levels of anxiety severity at baseline predicted more favorable outcomes (Compton et al., 2014).

Method

Participants

Participants for this study were third and fourth grade students drawn from three elementary schools in a diverse suburban Southwestern U.S. district. Across the three schools, from 34 to 49% (M = 41.2%; SD = 7.6%) of families qualified for free or reduced lunch and from 2 to 39% (M = 26%; SD = 21%) were English language learners (see Table 1). Initially, all third and fourth grade students (n = 495) in the three schools were screened using the Gates-MacGinitie reading comprehension subtest (GMRT-4; MacGinitie et al., 2000). Students were included in the final sample if they (a) performed at or below a standard score of 92 (30th percentile) on the GMRT-4 reading comprehension subtest, (b) their parent provided consent for participation, and (c) the student provided assent.

Table 1.

Sample information

| Demographic variable | RANX |

RMATH |

BaU |

Overall sample |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | N | % | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 18 | 41% | 22 | 51% | 27 | 65% | 67 | 52% |

| Female | 26 | 59% | 21 | 49% | 14 | 35% | 61 | 48% |

| Grade | ||||||||

| Three | 24 | 54% | 25 | 58% | 23 | 56% | 72 | 56% |

| Four | 20 | 46% | 18 | 42% | 18 | 43% | 56 | 44% |

| Ethnicity/race | ||||||||

| African Amer. | 7 | 16% | 09 | 21% | 12 | 30% | 28 | 22% |

| Caucasian | 13 | 30% | 12 | 28% | 7 | 17% | 32 | 25% |

| Latino/a | 22 | 50% | 20 | 47% | 21 | 51% | 63 | 49% |

| Other | 2 | 0% | 2 | 4% | 1 | 2% | 5 | 4% |

| Home language | ||||||||

| English | 37 | 84% | 34 | 79% | 31 | 76% | 102 | 80% |

| Spanish | 5 | 11% | 8 | 19% | 9 | 22% | 22 | 17% |

| Not reported | 2 | 5% | 1 | 2% | 1 | 2% | 4 | 3% |

| Special education | ||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 23% | 5 | 12% | 11 | 27% | 26 | 20% |

| No | 34 | 77% | 38 | 88% | 30 | 73% | 102 | 80% |

The identified study sample included a total of 128 students from 31 different classrooms. This study was implemented as a randomized controlled trial in which students were blocked within classroom teacher and then randomly assigned to condition. The design was partially nested and cross-classified—all students were nested in teachers (within schools), but only treatment condition students were nested in teachers and in interventionists (within schools), and teachers and interventionists were crossed (also within schools). An investigator with no clinical involvement in the study randomized students to treatment and control conditions after screening was completed. Assignment by a computerized random number generator, blocked by classroom, was used to increase the likelihood that similar numbers of children in each classroom were assigned to each condition. The blocked design was used to eliminate the between-groups component of the total variance estimates, which increased statistical power and improved precision. The originally proposed sample size (NIH R01HD087706) of 300 was associated with a minimal detectable effect of 0.20 for pairwise comparisons, assuming fixed treatment effects and moderate amounts of clustering at the classroom level.

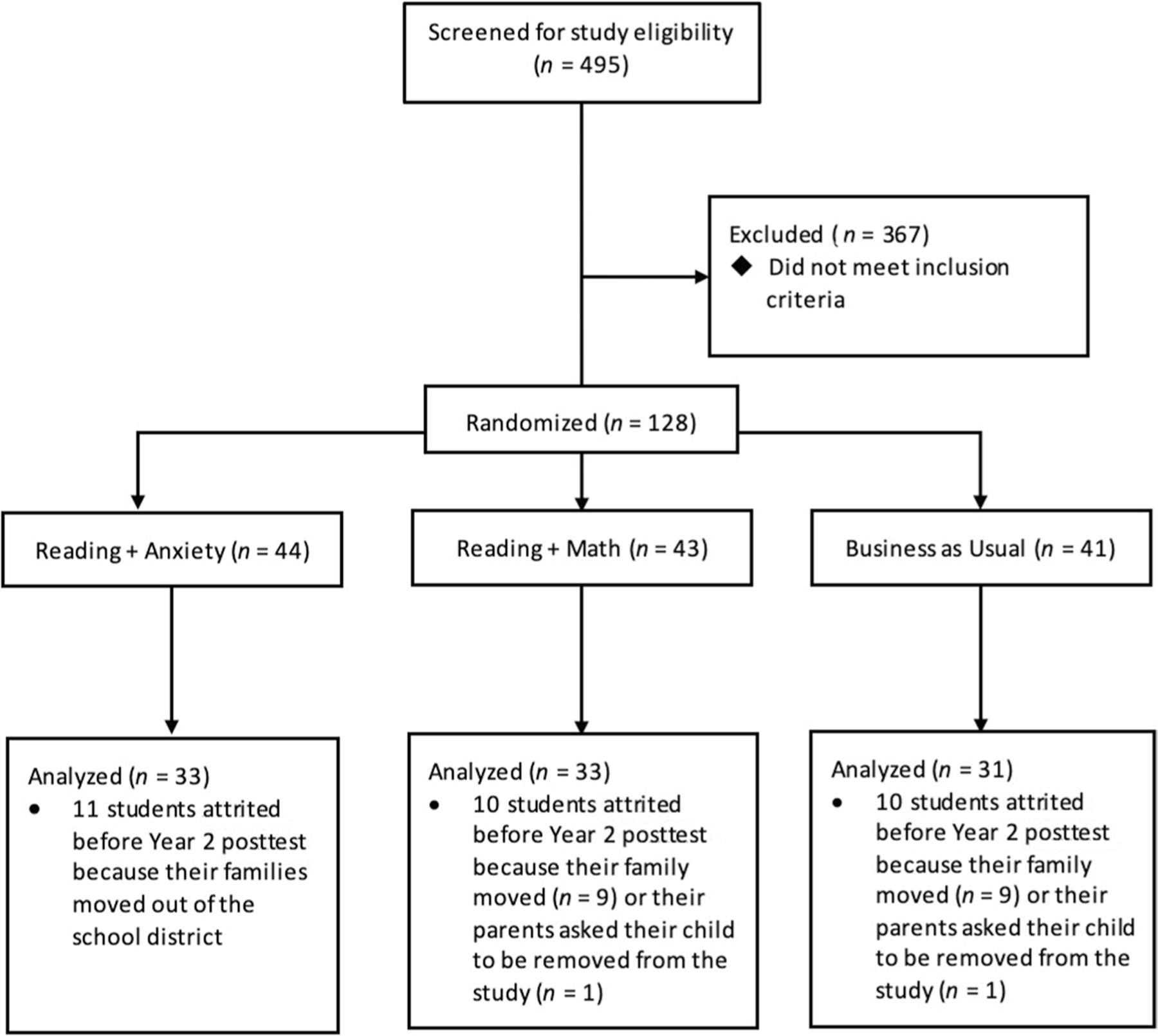

The 128 students included approximately equal numbers of students by sex (male = 52%) and grade (3rd grade = 56%). Students represented diverse racial/ethnic groups (49% Latino/a, 25% Caucasian/white, 22% African-American/Black, and 4% representing all other groups combined; see Table 1). Students were randomized to one of three conditions—reading and anxiety management (RANX; n = 44), reading and math (RMATH; n = 43), or business-as-usual (BaU; n = 41). Of the 128 randomized students, 31 were no longer in the study at the end of year 2 because they no longer attended a participating school (n = 29) or because the parent withdrew them from the study (n = 2). Attrition was similar across conditions (BaU: n = 10; RANX: n = 11; RMATH: n = 10). The flow of participants from screening through outcomes is represented in Fig. 1. Based on What Works Clearinghouse (2020) standards, these rates of overall attrition (24%) and differential attrition (2.9%) represent a low threat to internal validity under optimistic or cautious assumptions.

Fig. 1.

Study sample flow diagram

Procedures

Research staff, unfamiliar with students’ assignment to condition, administered and scored measures implemented to all participating students before and after the treatment instruction that occurred. These measures were administered in quiet areas designated by school personnel. Prior to each testing time point, assessment staff demonstrated 100% accuracy in administration, and scoring on all measures and protocols was double-scored and double-entered by members of the research team. Although all items are written using simplified language, test administrators read aloud all items to students.

The research team hired, trained, and managed interventionists to provide instruction to the small groups of students receiving intervention (nine tutors in year 1 and six new tutors in year 2). All interventionists were former or retired teachers (n = 12) or had prior experience providing school-based interventions (n = 4). The research team provided 3 days of training to the interventionists over the course of each school year to promote fidelity of implementation. Additionally, the research team conducted observations biweekly and met monthly with interventionists to discuss fidelity and instructional quality.

Students assigned to the RANX and RMATH treatment conditions received approximately 30 min of instruction in small groups 4 to 5 days a week with group sizes ranging between two and five students. The research team worked with partnering schools to schedule intervention instruction outside of the students’ core reading instructional block, most often during a time schools devoted to intervention and enrichment instruction. Intervention instruction occurred from October through March each school year. A total of 150 lessons were completed with the students in the treatment conditions over 2 academic school years (75 lessons per year). The reading instruction did not differ between RANX and RMATH. In year 1, students in RANX and RMATH treatment conditions received, on average, 25 min of reading instruction per session. In year 2, treatment sessions lasted an average of 27 min.

Measures

Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth

The Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth (BAI-Y) is a scale from the Beck Youth Inventories—Second Edition (BYI-II; Beck et al., 2005). The 20-item self-report scale assesses children’s fears and worries, and the physiological symptoms of anxiety, with higher scores on the BAI-Y representing higher levels of anxiety. For each item, children describe how frequently a statement is true for them using a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “always.” Previous research demonstrates the strong reliability and validity of the BAI-Y for youth populations (Beck et al., 2005). Alphas ranged from 0.89 to 0.93 while McDonald’s omega similarly ranged from 0.90 to 0.94 across time points in the current study.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., 1997) is a 39-item self-report questionnaire that measures anxiety in children using a 4-point Likert-type scale. For each item, children are asked to indicate their response to a statement according to the following scale: “never true about me,” “sometimes true about me,” “often true about me,” and always true about me.” Developed for students aged 8–19, the MASC yields four subscales. In the present study, three of these subscales were used (Physical Symptoms, Social Anxiety, and Separation/Panic). Previous research shows the MASC has acceptable internal consistency, concurrent and discriminant validity, and diagnostic accuracy for school-aged children (Grills-Taquechel et al., 2008), including students with learning disabilities (Thaler et al., 2010). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.79 to 0.84 on the Physical Symptoms subscale, 0.78 to 0.88 on the Social Anxiety subscale, and 0.64 to 0.75 on the Separation/Panic subscale. McDonald’s omega (ω; Hayes & Coutts, 2020) similarly ranged from 0.79 to 0.84 on the Physical Symptoms subscale, 0.79 to 0.88 on the Social Anxiety subscale, and 0.63 to 0.75 on the Separation/Panic subscale.

Reading Anxiety Scale

The Reading Anxiety Scale (Grills, 2014) is a 6-item self-report questionnaire that assesses students’ feelings of anxiety related to reading, reading instruction, and reading tests. A sample item is “Taking reading tests scares me”. For each item, students are asked to rate how frequently each statement is true for them using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “I never feel this way” to “I always feel this way.” Recently conducted analyses indicate the Reading Anxiety Scale demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency for students with reading difficulties in the upper-elementary grades (Grills et al., 2023). Alphas ranged from 0.76 to 0.86 while McDonald’s omega similarly ranged from 0.77 to 0.88 across time points.

Interventions

Reading Instruction

The reading components of the intervention are based upon the simple view of reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986), which conceptualizes reading comprehension as the product of two related but distinct constructs: decoding and linguistic comprehension. Decoding involves quickly and accurately recognizing words and using phonetic decoding to read words, while linguistic comprehension refers to contextual knowledge such as vocabulary and sentence syntax (Catts et al., 2005, 2015; Vaughn et al., 2020). The simple view of reading has been tested with large, diverse samples of children across grade levels with different outcome measures, and studies consistently confirm that decoding and linguistic comprehension predict reading comprehension (Catts et al., 2005, 2015; Vaughn et al., 2020). Thus, the current intervention provides lessons targeting these reading skills.

In addition, reading instruction targeted multiple components of reading as previous findings suggest that multiple component reading interventions lead to greater improvements than single component interventions for struggling readers in the upper-elementary grades and beyond (e.g., Scammacca et al. (2015)). The primary reading activities included (a) systematic decoding instruction and high-frequency word reading practice; (b) repeated text reading fluency practice with teacher modeling and feedback; (c) targeted comprehension instruction; and (d) text-based “stretch text” reading activities, in which students could practice applying taught word reading, fluency, and comprehension practices to texts that deliberately varied in genres and levels. Interventionists taught these instructional activities explicitly using routines for teacher modeling, guided practice, and independent practice coupled with frequent opportunities to practice and receive specific feedback (Archer & Hughes, 2011). The reading instruction and findings for reading are described extensively in Vaughn et al. (2021).

Anxiety Management Instruction

Students in the RANX condition received the above-described reading instruction with embedded anxiety management instruction using the Strong Students Toolbox (SST; Grills, 2015). SST was created using cognitive-behavioral practices commonly employed with anxious children. Informed by the challenges and benefits of school-based mental health interventions, SST adapts CBT for use in schools, with delivery by laypersons (i.e., teachers without mental health training) and in brief (5–10 min) applied lessons. The use of scripted lessons was intended to facilitate ease of training, implementation, and program integrity and reduces the need for psychological expertise in interventionists. The program focuses on teaching stress/anxiety management skills to students, as well as providing them ample opportunities to apply these skills in the context of reading. SST sessions focus on psychoeducation, normalizing experiences, and teaching anxiety management skills centered upon four core areas: (1) recognizing anxious feelings; (2) relaxation and stress management techniques (e.g., diaphragmatic breathing); (3) recognizing and modifying anxious and other unhelpful/negative thoughts; and (4) recognizing and challenging avoidance behaviors. The skills are taught using developmentally appropriate and engaging instructional practices. For example, interventionists demonstrated how students could act as a “physician’s assistant” when trying to identify physical signs of anxiety in themselves or others and provided students with multiple guided practice opportunities. The SST intervention is described in further detail in (Capin et al., 2023).

Preliminary examination of the SST program demonstrated its feasibility and efficacy when used as an “add-on” at the end of reading instruction lessons. Importantly, for the current project, the content was revised, such that it was woven throughout the reading lessons and with information and practices integrated carefully in reading content (e.g., reading fluency and comprehension activities). During the first year of intervention, SST instruction occurred daily for approximately 5 min per day within the RANX lessons. In year 2, SST instruction occurred in about one-third of lessons and focused primarily on review, maintenance, and transfer of anxiety management information and skills taught in year 1.

Math Facts Instruction

To control for the amount of time students engaged in reading activities and participated in small-group instruction across treatment conditions, students assigned to the RMATH condition spent the same amount of time engaged in math calculation practice as RANX students spent on SST instruction. Math calculation instruction and practice consisted of students working with tutors on grade-level or below math standards (e.g., addition, subtraction, multiplication, division of whole numbers, decimals, and fractions). Interventionists provided brief instruction and then students worked on practice items independently or in pairs as tutors provided feedback. All instruction in the reading intervention was the same in the RANX and RMATH conditions.

BaU Instruction

Students randomized to the BaU condition received typical school-based supplemental reading instruction during the intervention/enrichment time when treatment students received the research-provided treatments (i.e., RANX or RMATH) (see Vaughn et al. (2021) for complete description). None of the teachers reported providing anxiety management instruction during the enrichment/intervention time block.

Treatment Fidelity

Based on previous recommendations for examining treatment fidelity (e.g., O’Donnell (2008)), multiple dimensions of treatment fidelity were measured, including treatment adherence, instructional quality, and program differentiation (overlap between treatment and comparison instruction). All RANX and RMATH treatment sessions were audio-recorded and a sample of BaU instruction was audio-recorded each year. Detailed description of the sampling methods used to evaluate fidelity are provided in Vaughn et al. (2021) and are summarized here. For treatment adherence, ratings from 1 (low) to 4 (high) were made for RANX and RMATH. Adherence to reading instruction for RANX (M = 3.51, SD = 0.82) and RMATH (M = 3.50, SD = 0.74) was similar. Adherence to SST components (M = 3.61, SD = 0.65) and math instruction (M = 3.86, SD = 0.62) was also high. For global quality, ratings from 1 (lowest quality) to 5 (highest quality) were made. Based on a detailed rubric, coders assessed instructional quality, feedback to students, classroom management, pacing, and student engagement. Similarly, high scores were found on all dimensions for RANX (M range = 4.08–4.35), RMATH (M range = 3.97–4.25), and BaU (M range = 4.20–4.45).

Data Analysis Plan

The data for this study involved four levels of nesting: 128 students were partially nested in 11 tutors, nested in 34 teachers, nested in 3 schools. Accordingly, we fit four-level models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) for all outcomes. For several outcome measures, these models resulted in singular fits, indicating that they were overfit and that random effects at either tutor, teacher, or school-level were not estimable in these data. Thus, for each outcome, we gradually removed random effects at either the school, teacher, or tutor levels and estimated a more parsimonious model. For one outcome measure, BYI, we estimated a four-level model, while for others a three- or two-level model. For MASC separation anxiety and reading anxiety, there was no cluster-level variance; therefore, we estimated a single-level model.

Separate analyses for each dependent variable were run using the mean-centered pretest as a covariate to improve statistical power and adjust groups at pre-treatment as necessary. Effect sizes were estimated as the ratio between the model-derived treatment coefficients and the unadjusted pooled within-group standard deviation across conditions at posttest. Because these data represent the first cohort of what was initially designed to be two cohorts of data, the design is underpowered, per our prospective estimates of statistical power. This resulted from the second cohort being disrupted by school closures in response to the COVID-19 public health pandemic. Despite this, we intend to increase access to preliminary findings and facilitate open access to our data in a time-sensitive and transparent manner aligning with the research reforms aimed at improving scientific rigor and access (Cook et al., 2018).

The main effects of RANX were estimated by contrasting to BaU and by contrasting to RMATH. Separate models were fit for each dependent variable and adjusted for false discovery rates (the probability of Type 1 error) using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). As students were screened only on reading measures, it was expected that student anxiety levels would vary among students assigned to each of the treatment conditions. Given this, subgroup analyses were conducted to explore whether differential outcomes emerged for students who entered the study with lower or higher baseline anxiety. Prior research has shown that those with lower baseline anxiety show greater response to intervention and since the current study delivered low-intensity anxiety instruction, it was expected that this would hold true in our study for those with “average” versus “elevated” anxiety. Students’ reports on the BAI-Y were used to create the two categories based on categorizations provided in the BAI-Y manual. Specifically, “average anxiety” was defined as T-scores < 55 and “elevated anxiety” as those with T-scores of 55 or greater (Beck et al., 2005). Treatment effects were estimated within subsamples of students identified as having elevated levels of anxiety and for students with average levels of anxiety, based on their pretest T-scores on the BAI-Y. The initial unconditional models were run with the “lme4” (Bates et al., 2015), while the single-level models were run using the “emmeans” package (Lenth et al., 2020) in R.

Results

At baseline, the three treatment conditions were equivalent on all measures of anxiety. There was baseline imbalance for several demographic categories known to correlate with the outcome variables, including sex (Mitchison & Njardvik, 2019), special education status (Cowden, 2010; Fisher et al., 1996), and race (Latzman et al., 2011). Therefore, these variables were included as covariates in our analytic models, per What Works Clearinghouse (2020) recommendations. Table 2 summarizes the sample mean and standard deviation for all variables at each of the three time points (pretest, post year 1 intervention, and post year 2 intervention). Additionally, Table 3 summarizes sample mean and standard deviation by treatment condition and level of pretest anxiety.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics by study condition

| Outcome variables | Pretest, year 1 |

Posttest, year 1 |

Posttest, year 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| BAI-Y | |||||||||

| BaU | 39 | 53.18 | 12.29 | 35 | 50.57 | 13.34 | 31 | 54.23 | 13.86 |

| RANX | 41 | 52.80 | 14.35 | 37 | 47.95 | 9.68 | 33 | 48.36 | 12.25 |

| RMATH | 40 | 55.45 | 12.36 | 37 | 50.41 | 12.75 | 31 | 50.77 | 11.52 |

| MASC: Physical Symptoms | |||||||||

| BaU | 38 | 55.87 | 11.39 | 36 | 54.58 | 7.80 | 31 | 51.74 | 10.99 |

| RANX | 37 | 55.92 | 12.38 | 38 | 49.71 | 10.29 | 33 | 49.21 | 8.75 |

| RMATH | 40 | 56.15 | 9.99 | 36 | 51.06 | 11.48 | 30 | 49.27 | 10.45 |

| MASC: Social Anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 38 | 55.79 | 10.14 | 36 | 53.94 | 10.75 | 31 | 56.61 | 11.37 |

| RANX | 37 | 55.32 | 13.12 | 38 | 49.47 | 9.71 | 33 | 49.70 | 11.43 |

| RMATH | 40 | 53.90 | 9.75 | 36 | 50.64 | 11.06 | 30 | 53.40 | 12.20 |

| MASC: Separation/Panic | |||||||||

| BaU | 38 | 59.79 | 11.80 | 36 | 55.83 | 11.24 | 31 | 58.81 | 11.15 |

| RANX | 37 | 58.19 | 10.84 | 38 | 56.53 | 10.88 | 33 | 53.85 | 11.00 |

| RMATH | 40 | 57.63 | 11.00 | 36 | 54.64 | 8.86 | 30 | 55.73 | 10.84 |

| Reading anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 40 | 16.60 | 6.26 | 36 | 15.06 | 6.33 | 31 | 15.68 | 6.28 |

| RANX | 43 | 15.58 | 6.11 | 38 | 13.16 | 4.77 | 33 | 13.55 | 6.44 |

| RMATH | 42 | 15.52 | 5.13 | 38 | 14.82 | 4.64 | 31 | 14.48 | 4.52 |

RANX, reading + anxiety; RMATH, reading + math; BaU, business as usual; BAI-Y, Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth; MASC, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by study condition and anxiety level

| Outcome variables | Pretest, year 1 |

Posttest, year 1 |

Posttest, year 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| BAI-Y | |||||||||

| Average anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 24 | 45.67 | 6.36 | 20 | 46.80 | 12.58 | 18 | 50.50 | 14.71 |

| RANX | 21 | 40.76 | 5.43 | 19 | 43.79 | 7.28 | 16 | 42.50 | 11.01 |

| RMATH | 20 | 46.05 | 5.77 | 19 | 48.26 | 10.24 | 16 | 46.88 | 10.18 |

| Elevated anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 15 | 65.20 | 9.59 | 15 | 55.60 | 13.03 | 13 | 59.38 | 11.15 |

| RANX | 20 | 65.45 | 8.59 | 18 | 52.33 | 10.13 | 17 | 53.88 | 10.95 |

| RMATH | 20 | 64.85 | 9.71 | 18 | 52.67 | 14.92 | 14 | 55.07 | 12.15 |

| MASC: Physical Symptoms | |||||||||

| Average anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 23 | 51.87 | 8.89 | 21 | 52.90 | 8.29 | 18 | 49.06 | 10.64 |

| RANX | 18 | 51.39 | 13.10 | 19 | 44.37 | 7.82 | 16 | 45.69 | 9.95 |

| RMATH | 20 | 52.55 | 9.77 | 19 | 49.63 | 9.95 | 16 | 48.69 | 11.23 |

| Elevated anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 15 | 62.00 | 12.35 | 15 | 56.93 | 6.63 | 13 | 55.46 | 10.77 |

| RANX | 19 | 60.21 | 10.23 | 19 | 55.05 | 9.80 | 17 | 52.53 | 6.01 |

| RMATH | 20 | 59.75 | 9.07 | 17 | 52.65 | 13.11 | 14 | 49.93 | 9.86 |

| MASC: Social Anxiety | |||||||||

| Average anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 23 | 52.35 | 10.22 | 21 | 51.10 | 11.05 | 18 | 54.33 | 10.98 |

| RANX | 18 | 47.06 | 11.13 | 19 | 43.79 | 6.85 | 16 | 45.75 | 11.62 |

| RMATH | 20 | 50.70 | 8.59 | 19 | 49.58 | 9.57 | 16 | 48.88 | 8.61 |

| Elevated anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 15 | 61.07 | 7.62 | 15 | 57.93 | 9.25 | 13 | 59.77 | 11.57 |

| RANX | 19 | 63.16 | 9.70 | 19 | 55.16 | 8.87 | 17 | 53.41 | 10.22 |

| RMATH | 20 | 57.10 | 9.99 | 17 | 51.82 | 12.71 | 14 | 58.57 | 13.88 |

| MASC: Separation/Panic | |||||||||

| Average anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 23 | 58.87 | 12.05 | 21 | 56.00 | 12.61 | 18 | 57.44 | 12.60 |

| RANX | 18 | 54.06 | 8.68 | 19 | 52.74 | 8.89 | 16 | 49.13 | 8.47 |

| RMATH | 20 | 55.00 | 9.78 | 19 | 54.05 | 9.47 | 16 | 52.75 | 9.06 |

| Elevated anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 15 | 61.20 | 11.68 | 15 | 55.60 | 9.40 | 13 | 60.69 | 8.88 |

| RANX | 19 | 62.11 | 11.42 | 19 | 60.32 | 11.58 | 17 | 58.29 | 11.47 |

| RMATH | 20 | 60.25 | 11.77 | 17 | 55.29 | 8.35 | 14 | 59.14 | 12.01 |

| Reading anxiety | |||||||||

| Average anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 24 | 14.08 | 5.96 | 21 | 13.24 | 5.96 | 18 | 15.39 | 6.80 |

| RANX | 21 | 12.76 | 4.93 | 19 | 12.11 | 4.69 | 16 | 10.50 | 6.16 |

| RMATH | 20 | 14.35 | 5.28 | 19 | 15.53 | 4.93 | 16 | 14.06 | 4.88 |

| Elevated anxiety | |||||||||

| BaU | 15 | 20.53 | 4.81 | 15 | 17.60 | 6.14 | 13 | 16.08 | 5.74 |

| RANX | 20 | 19.40 | 4.99 | 19 | 14.21 | 4.74 | 17 | 16.41 | 5.41 |

| RMATH | 20 | 17.10 | 4.73 | 17 | 13.88 | 4.55 | 14 | 15.14 | 4.31 |

RANX, reading + anxiety; RMATH, reading + math; BAU, business as usual; BAI-Y, Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth; MASC, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

Main Effects at the End of the 1st Year

Table 4 presents results for the contrasts of RANX versus BaU and RANX versus RMATH. Note that negatively signed values represent lower levels of anxiety (i.e., a desirable outcome). The effect size for students in RANX versus BaU for MASC Physical Symptoms was − 0.49 (95% CI [− 0.97, − 0.01]), for MASC Social Anxiety was − 0.40 (95% CI [ − 0.81, 0.01]), for BAI-Y was − 0.23 (95% CI [− 0.70, 0.24]), and for reading anxiety was − 0.26 (95% CI [− 0.66, 0.14]); however, these were not statistically significant differences after adjusting for false discovery rate. Differences between students in RANX and RMATH generally favored RANX, especially on the Reading Anxiety Scale (− 0.39 (95% CI [− 0.86, 0.08])); however, none of these results was statistically significant. These effect sizes represent the standardized difference between treated and untreated groups. An effect of 0.50, for example, means that students in a treatment group(s) outperformed students in an alternative by one-half of a standard deviation. Effect sizes are useful for indicting the magnitude of a difference when samples are small and statistical power is typically low.

Table 4.

Main effect analysis at the end of year 1 and year 2

| Predictors | Posttest, year 1 | Posttest, year 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | p-value | fdr p | ES [95% CI] | Est. | SE | p-value | fdr p | ES [95% CI] | |

| BYI: anxiety scale | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 49.17 | 2.59 | 0.001 | 53.65 | 2.72 | 0.001 | ||||

| Pretest | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.001 | ||||

| RANX vs. BaU | − 2.62 | 2.71 | 0.34 | 0.43 | − 0.23 [− 0.70, 0.24] | − 6.67 | 2.72 | 0.02* | 0.04* | − 0.57 [− 1.04, − 0.10] |

| RANX vs. RMATH | − 2.25 | 2.80 | 0.43 | 0.43 | − 0.20 [− 0.70, 0.30] | − 1.26 | 2.80 | 0.66 | 0.66 | − 0.11 [− 0.58, 0.37] |

| Race | − 1.07 | 2.51 | 0.67 | 2.92 | 2.57 | 0.26 | ||||

| Gender | 1.80 | 2.21 | 0.42 | 1.91 | 2.30 | 0.41 | ||||

| SWD | 4.47 | 2.63 | 0.09 | − 2.81 | 2.86 | 0.33 | ||||

| Random effects | Var. | ICC | Var. | ICC | ||||||

| Residual | 118.58 | 0.91 | 110.08 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Tutor-level | 6.55 | 0.05 | 0.00 | |||||||

| Teacher-level | 0.38 | 0.00 | 11.86 | 0.09 | ||||||

| School-level | 4.66 | 0.04 | 4.99 | 0.04 | ||||||

| MASC: Physical Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 53.61 | 1.86 | 0.001 | 49.61 | 2.06 | 0.001 | ||||

| Pretest | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.001 | ||||

| RANX vs. BaU | − 4.45 | 2.15 | 0.04 | 0.09 | − 0.49 [− 0.97, − 0.01] | − 2.24 | 2.38 | 0.351 | 0.70 | − 0.23 [− 0.72, 0.26] |

| RANX vs. RMATH | − 1.28 | 2.25 | 0.57 | 0.57 | − 0.12 [− 0.54, 0.30] | 0.11 | 2.43 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.01 [− 0.50, 0.53] |

| Race | 1.46 | 2.05 | 0.48 | 2.12 | 2.18 | 0.33 | ||||

| Gender | − 0.51 | 1.75 | 0.77 | 2.28 | 2.00 | 0.25 | ||||

| SWD | 3.63 | 2.08 | 0.09 | 1.67 | 2.44 | 0.49 | ||||

| Random effects | Variance | ICC | Variance | ICC | ||||||

| Residual | 65.46 | 0.77 | 86.13 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Tutor-level | 11.56 | 0.14 | 0.00 | |||||||

| Teacher-level | 7.63 | 0.09 | 0.00 | |||||||

| School-level | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.01 | |||||||

| MASC: Social Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 52.43 | 1.8 | 0.001 | 53.63 | 2.01 | 0.001 | ||||

| Pretest | 0.47 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.001 | ||||

| RANX vs. BaU | − 4.09 | 2.08 | 0.05 | 0.11 | − 0.40 [− 0.81, 0.01] | − 7.03 | 2.24 | 0.00* | 0.01* | − 0.62 [− 1.03, − 0.22] |

| RANX vs. RMATH | − 1.17 | 2.09 | 0.58 | 0.58 | − 0.11 [− 0.52, 0.29] | − 3.83 | 2.27 | 0.10 | 0.10 | − 0.33 [− 0.72, 0.06] |

| Race | 0.91 | 1.96 | 0.64 | 1.69 | 2.12 | 0.43 | ||||

| Gender | 2.15 | 1.73 | 0.22 | 4.05 | 1.90 | 0.04 | ||||

| SWD | − 1.59 | 2.05 | 0.44 | − 1.34 | 2.36 | 0.57 | ||||

| Random effects | Variance | ICC | Variance | ICC | ||||||

| Residual | 74.81 | 0.94 | 72.21 | 0.83 | ||||||

| Tutor-level | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Teacher-level | 4.88 | 0.06 | 15.23 | 0.17 | ||||||

| School-level | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| MASC: Separation Anxiety | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 56.32 | 2.04 | 0.001 | 57.36 | 2.20 | 0.001 | ||||

| Pretest | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.008 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.001 | ||||

| RANX vs. BaU | 0.81 | 2.42 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.07 [− 0.37, 0.51] | − 3.32 | 2.48 | 0.18 | 0.38 | − 0.30 [− 0.76, 0.15] |

| RANX vs. RMATH | 2.30 | 2.42 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.23 [− 0.26, 0.73] | − 0.01 | 2.52 | 0.99 | 0.99 | − 0.01 [− 0.47, 0.47] |

| Race | 0.13 | 2.23 | 0.95 | − 0.17 | 2.34 | 0.94 | ||||

| Gender | 0.53 | 1.97 | 0.79 | − 0.02 | 2.07 | 0.99 | ||||

| SWD | − 3.32 | 2.35 | 0.16 | 2.93 | 2.59 | 0.26 | ||||

| Random effects | Variance | ICC | ||||||||

| Residual | 88.77 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Tutor-level | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Teacher-level | 14.54 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| School-level | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Reading Anxiety Scale | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 15.01 | 0.93 | 0.001 | 15.6 | 1.33 | 0.001 | ||||

| Pretest | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.001 | ||||

| RANX vs. BaU | − 1.43 | 1.10 | 0.20 | 0.19 | − 0.26 [− 0.66, 0.14] | − 1.84 | 1.40 | 0.19 | 0.36 | − 0.29 [− 0.74, 0.15] |

| RANX vs. RMATH | − 1.81 | 1.09 | 0.10 | 0.19 | − 0.39 [− 0.86, 0.08] | − 1.31 | 1.41 | 0.36 | 0.36 | − 0.24 [− 0.75, 0.027] |

| Race | − 1.68 | 1.01 | 0.10 | − 0.31 | 1.28 | 0.81 | ||||

| Gender | − 0.37 | 0.90 | 0.68 | − 0.03 | 1.17 | 0.98 | ||||

| SWD | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.41 | − 1.00 | 1.44 | 0.49 | ||||

| Random effects | Variance | ICC | ||||||||

| Residual | 29.92 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| Tutor-level | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Teacher-level | 0.00 | |||||||||

| School-level | 1.15 | 0.04 | ||||||||

RANX, reading + anxiety; RMATH, reading + math; BaU, business as usual; BAI-Y, Beck Anxiety Inventory for Youth; MASC, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; FDR p, false discovery rate corrected p-value

p < .05

Main Effects at the End of the 2nd Year

When compared to students in the BaU, RANX students reported significantly lower levels of anxiety on the MASC Social Anxiety subscale (β = − 7.03, SE = 2.24, ES = − 0.62 (95% CI [− 1.03, − 0.22]) and the BAI-Y (β = − 6.67, SE = 2.72, ES = − 0.57 (95% CI [− 1.04, − 0.10]). Further, the effect size for the MASC Separation/Panic subscale (ES = − 0.30 (95% CI [− 0.76, 0.15]) and the Reading Anxiety Scale (ES = − 0.29 (95% CI [− 0.74, 0.15]) were moderate, though not statistically significant with false discovery rate correction applied. While RANX students, compared to those in RMATH, reported lower levels of anxiety on the MASC Social Anxiety subscale (β = − 3.83, SE = 2.27, ES = − 0.33 (95% CI [− 0.72, 0.06]), this finding was not statistically significant (p = .05). Further, the difference between RMATH and RANX conditions on the other measures was not statistically significant, though the pattern of findings indicated RANX students reported lower anxiety across measures.

Subgroup Main Effects at the End of the 1st Year

Table 5 summarizes treatment effects for students overall and separated based on pretest levels of anxiety (average or elevated). After the first year of intervention, students who reported average pre-intervention anxiety from the RANX condition reported significantly lower anxiety on the MASC Physical Symptoms subscale than did students in the BaU condition (β = − 10.25, SE = 2.56, ES = − 1.30 (95% CI [− 2.03, − 0.56]). Significantly lower Physical Symptoms were also found when comparing students from the RANX condition to those in RMATH (β = − 6.83, SE = 2.81, ES = − 0.78 (95% CI [− 1.45, − 0.11]). Further, the standardized differences between the groups on several other anxiety outcome measures were sizable but not statistically significant after adjusting for false discovery rate. For instance, the difference between RANX and BaU on MASC Social Anxiety (ES = − 0.70 (95% CI [− 1.48, − 0.07]), as well as between RANX and RMATH on MASC Social Anxiety (ES = − 0.77 (95% CI [− 1.52, − 0.02]) and the Reading Anxiety Scale (ES = − 0.54 (95% CI [− 1.13, 0.04]), was moderately large. For students with elevated levels of anxiety at pretest, there were no significant differences between conditions at the end of year 1; however, the standardized difference between students in RANX and BaU was sizable on several outcome measures (BAI-Y: ES = − 0.37 (95% CI [− 1.22, 0.49]); MASC Social Anxiety: ES = − 0.61 (95% CI [− 1.27, 0.05]); reading anxiety: ES = − 0.56 (95% CI [− 1.24, 0.12]).

Table 5.

Effect sizes for condition comparisons for overall sample, average anxiety subgroup, and elevated anxiety subgroup

| Outcome variables | Posttest, year 1 | Posttest, year 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Average | Elevated | Overall | Average | Elevated | |

| ES [95% CI] | ES [95% CI] | ES [95% CI] | ES [95% CI] | ES [95% CI] | ES [95% CI] | |

| BAI-Y | ||||||

| RANX v BaU | − 0.23 [− 0.70, 0.24] | − 0.31 [− 1.07, 0.46] | − 0.37 [− 1.22, 0.49] | − 0.57 [− 1.04, − 0.10] | − 0.48 [− 1.21, 0.26] | − 0.80 [− 1.49, − 0.11] |

| RANX v RMATH | − 0.20 [− 0.70, 0.30] | − 0.38 [− 1.22, 0.46] | − 0.13 [− 0.89, 0.62] | − 0.11 [− 0.58, 0.37] | − 0.08 [− 1.04, 0.88] | − 0.16 [− 0.90, 0.58] |

| MASC: Physical Symptoms | ||||||

| RANX v BaU | − 0.49 [− 0.97, − 0.01] | −1.30 [− 2.03, − 0.56] | − 0.16 [− 1.07, 0.76] | − 0.23 [− 0.72, 0.26] | − 0.49 [− 1.30, 0.33] | − 0.41 [− 0.83, 1.10] |

| RANX v RMATH | − 0.12 [− 0.54, 0.30] | − 0.78 [− 1.45, − 0.11] | 0.10 [− 0.60, 0.80] | 0.01 [− 0.50, 0.53] | − 0.41 [− 1.22, 0.40] | 0.14 [− 0.83, 1.10] |

| MASC: Social Anxiety | ||||||

| RANX v BaU | − 0.40 [− 0.81, 0.01] | − 0.70 [− 1.48, 0.07] | − 0.61 [− 1.27, 0.05] | − 0.62 [− 1.03, − 0.22] | − 0.58 [− 1.22, 0.07] | − 0.93 [− 1.76, − 0.10] |

| RANX v RMATH | − 0.11 [− 0.52, 0.29] | − 0.77 [− 1.52, − 0.02] | 0.15 [− 0.37, 0.67] | − 0.33 [− 0.72, 0.06] | − 0.26 [− 0.97, 0.44] | − 0.76 [− 1.50, − 0.01] |

| MASC: Separation/Panic | ||||||

| RANX v BaU | 0.07 [− 0.37, 0.51] | − 0.29 [− 0.96, 0.37] | 0.35 [− 0.31, 1.01] | − 0.30 [− 0.76, 0.15] | − 0.61 [− 1.33, 0.11] | − 0.09 [− 0.81, 0.64] |

| RANX v RMATH | 0.23 [− 0.26, 0.73] | − 0.25 [− 1.07, 0.57] | 0.47 [− 0.19, 1.14] | − 0.01 [− 0.47, 0.47] | − 0.43 [− 1.30, 0.45] | 0.06 [− 0.57, 0.69] |

| Reading Anxiety | ||||||

| RANX v BaU | − 0.26 [− 0.66, 0.14] | − 0.12 [− 0.80, 0.56] | − 0.56 [− 1.24, 0.11] | − 0.29 [− 0.74, 0.15] | − 0.99 [− 1.83, − 0.14] | 0.06 [− 0.68, 0.80] |

| RANX v RMATH | − 0.39 [− 0.86, 0.08] | − 0.54 [− 1.13, 0.04] | − 0.39 [− 1.14, 0.36] | − 0.24 [− 0.75, 0.027] | − 0.53 [− 1.27, 0.20] | − 0.08 [− 0.96, 0.79] |

Subgroup Main Effects at the End of the 2nd Year

Among students with average anxiety at pretest, those in the RANX condition reported significantly lower levels of reading anxiety than the BaU condition (β = − 5.21, SE = 2.14, ES = − 0.99 (95% CI [− 1.83, − 0.14]) at the end of year 2. On the other outcomes, differences between RANX and BaU were not statistically significant, but the effect sizes were considered moderately large (ES = − 0.48 to − 0.61; see Table 5). Among students with elevated anxiety at pretest, those in the RANX condition demonstrated significantly lower levels of MASC Social Anxiety than those from the BaU (β = − 9.79, SE = 3.76, ES = − 0.93 (95% CI [− 1.76, − 0.10]) and RMATH conditions (β = − 8.98, SE = 4.16, ES = − 0.76 (95% CI [− 1.50, − 0.01]) at the end of year 2. There were no significant differences between conditions on the other measures, although there was a large effect size favoring RANX compared to BaU on the BAI-Y (ES = − 0.80 (95% CI [− 1.49, 0.11]).

Discussion

This study reports findings on anxiety outcomes from a 2-year, multi-component reading and anxiety management intervention with upper-elementary school struggling readers. This three-arm randomized controlled trial compared students in two treatment conditions—reading with anxiety (RANX) and reading with math (RMATH)—to school-provided supplemental instruction (BaU). At the end of the 1st year, there were no statistically significant differences between students in RANX, RMATH, or BaU conditions on anxiety measures after controlling for multiple comparison. However, multiple effect sizes were moderate, indicating average gains in the expected direction for students in the RANX condition at end of the 1st year with the lack of statistical significance likely affected by limited power. At the end of the 2nd year of the program, students who received the RANX intervention reported significantly lower levels of social anxiety on the MASC and overall anxiety on the BYI when compared to students in the BaU. Other anxiety outcomes were also favorable but not statistically significant. Overall, we interpret these findings as demonstrating promise for the efficacy of integrating anxiety management practices within reading intervention with effect sizes consistently favoring the RANX condition, although not statistically significant. These positive effects are encouraging because they cannot be attributed solely to the reading intervention and were realized with minimal attention to improving students use of anxiety management practices (i.e., several minutes within a lesson).

When examining students with average anxiety at pretest, students in the RANX condition reported significantly lower physical symptoms of anxiety as measured on the MASC at the end of year 1 as compared with those in BaU and RMATH conditions. Students in the RANX condition also reported greater reductions in social and reading anxiety symptoms, although these findings were no longer statistically significant when adjusted for false discovery rate. At the end of year 2, students who began the year with average anxiety and were in the RANX condition reported significantly lower levels of reading anxiety than students from the BaU condition. Effect sizes favoring RANX were noted on all outcomes when compared to BaU, although they were not consistently significant. Although these findings are preliminary given the relatively small number of participants, they are consistent with the hypothesis that the combined anxiety management/reading intervention would have beneficial effects on at least some symptoms of anxiety for students with average levels of pretest anxiety. Importantly, these students are unlikely to have been identified for anxiety intervention, but appeared to still benefit from the program in terms of symptom reduction in some subtypes of anxiety.

For students who reported elevated anxiety at pretest, there were no significant differences across groups at the end of year 1. While not significant, effect sizes indicated greater average improvement in social (ES = − 0.61) and reading (ES = − 0.56) anxiety for students in the RANX compared with BaU conditions at the end of year (1). At the end of year 2, students with elevated anxiety at pretest in the RANX condition had significantly lower levels of social anxiety compared to students in the BaU and RMATH conditions. Examination of the subgroup descriptive statistics revealed that students across all 3 conditions who reported elevated anxiety at pretest (i.e., beginning of year 1 intervention) tended to show decreases in anxiety symptoms from pretest to end of year 1; however, for RANX students, these scores generally remained stable or continued to decrease, whereas for BaU and RMATH students, anxiety levels either remained stable or began to increase from end of year 1 to end of year (2). Such a trend suggests that combining anxiety management and reading interventions may have had beneficial effects even in areas (i.e., symptoms of social anxiety and separation panic) not directly targeted by the intervention. While unexpected, this finding suggests that there may be nuance to the types of symptoms that respond to an intervention program like this for those with elevated versus average anxiety; however, a fully powered study is necessary to understand whether these findings are replicable and potentially significant.

One of the most consistent findings pertained to decreases in social anxiety symptoms for students in the RANX condition. In their systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the relationship between poor reading and internalizing difficulties, Francis et al. (2019) found that only 3 out of the 22 studies examined anxiety disorder subtypes, and none of those studies examined social anxiety. Given that reading aloud in front of others frequently occurs in the elementary grades (O’Connor et al., 2013), it is understandable that students struggling to read may have heightened fears about others’ perceptions and judgments of their ability. Indeed, several of the social anxiety subscale items reflected concerns about being laughed at, perceived of as stupid, or called on in class. Studies have shown that exposure to and engagement in or with a feared stimulus is an efficacious component of CBT (Olatunji et al., 2010)—which, if applied to struggling readers, could mean that students who were exposed to reading aloud in the RANX and RMATH conditions would demonstrate decreases in their social anxiety. Given the stronger findings for students in the RANX condition, it may be that the combination of coping and stress reduction skills with the repeated exposure to reading out loud was particularly helpful. It may also be that learning about anxiety alongside other students normalizes the experience of anxiety and helps decrease the fear response.

At the end of the 1st year, students with average pre-intervention anxiety reported significantly lower physical symptoms of anxiety compared to students with average pre-intervention anxiety in the BAU and RMATH conditions. The reduction of physical symptoms of anxiety in the RANX condition is consistent with general findings on the efficacy of CBT for anxiety symptoms (Crowe & McKay, 2017; Grills & Ollendick, 2013) and specific evidence demonstrating the efficacy of CBT on somatic complaints (Warner et al., 2011). Interestingly, students in RMATH also tended to demonstrate decrements in anxiety symptoms over time, suggesting that, perhaps for struggling readers, receiving intervention content for their difficulties may alleviate some symptoms of stress and anxiety. The reading main effects study (Vaughn et al., 2021) indicated that RANX and RMATH differed from BaU in their reading performance on a researcher-developed comprehension measure, and effect sizes on standardized measures of reading suggested RANX and RMATH had a positive effect on reading outcomes relative to BaU. These differences in reading gains may also be a reason why students in RANX and RMATH reported less anxiety than their BaU counterparts.

In all, coupling these results with the previously published reading outcomes findings (Vaughn et al., 2021) provides preliminary support for integrating anxiety management skills into a reading intervention for struggling upper-elementary school readers. As this study is the first longitudinal randomized control study examining the integration of evidence-based anxiety and reading interventions with both a comparable intervention on time and a treatment as usual group, it extends previous findings demonstrating the benefit of integrating CBT and reading interventions (Francis et al., 2021; Grills et al., 2022). For instance, Francis et al. (2021) examined an intervention format conducted outside of the school setting that included three 1-hour sessions per week in-person or online for 12 weeks that combined a tailored CBT intervention, Cool Kids, with a reading intervention compromised of modules from the Macquarie University Reading Clinic. There, participants were seven struggling readers who also had clinically diagnosed anxiety. With consideration for the extremely small sample, post-treatment effects showed significant reductions in anxiety disorder diagnoses and symptoms, as well as improvements on reading measures (Francis et al., 2021), adding support for potential anxiety reduction benefits as well as improved reading outcomes from providing CBT and reading intervention together.

The preliminary positive findings with the RANX intervention also provide further support for adapting cognitive-behavioral interventions for anxiety management within the school setting. Integration of mental health treatment in school may help reduce or eliminate the multiple noted barriers for children to receiving mental health treatment (Salloum et al., 2016). To date, CBT in schools has often focused on providing standard treatment (i.e., provided by a trained mental health professional; delivered in 60-minute sessions) to children who met criteria for an anxiety disorder (Chiu et al., 2013). While these interventions are necessary and important, they may interfere with educational activities given session length and require schools to have or partner with trained mental health professionals, which can be a significant barrier given that many schools lack the recommended number of school-based mental health staff (Whitaker et al., 2019). Further, there remains a lack of mental health professionals trained in evidence-based treatments (Weissman et al., 2006). SST, the anxiety management instruction component of the RANX condition, overcomes these barriers through its shortened delivery (approximately 5 minutes per lesson) and ability to be delivered by individuals with no prior mental health training. SST’s delivery within schools may also make it more accessible and acceptable to families (Sanchez et al., 2018). Furthermore, like the intervention in Ruocco et al. (2016), SST is delivered in small groups, allowing more students to receive intervention at once than in individual CBT. Integrating SST with an educational intervention also allows students to learn skills to manage anxiety without having a diagnosed anxiety disorder. Although beyond the scope of this study, it will be worth examining whether learning these skills early has any protective effect against the later development of an anxiety disorder.

As previously described, differential patterns of results emerged for students who began the year with average versus elevated anxiety. Though preliminary and not significant likely due to the size of the subsamples, overall larger effect sizes were noted for group comparisons favoring RANX for students who began the year with average levels of anxiety. These findings may reflect that, for students with elevated anxiety, a more intensive and individualized implementation of SST may be necessary. However, by not just including kids with diagnosed or subclinical anxiety disorders, as has been done in previous studies where CBT was provided in school settings, the present study was able to demonstrate positive effects for students more broadly. Providing students with evidence-based coping skills to manage anxiety is particularly important given the prevalence (Merikangas et al., 2010b) and chronicity of youth anxiety disorders (Wehry et al., 2015).

It may also be valuable to evaluate whether varying dosage levels correspond with optimal outcomes. For example, in the current study, students in year 2 received considerably less anxiety management training than they had in year 1. It may be beneficial to increase the amount of anxiety management review and practice in year 2, as some research looking at CBT has demonstrated that effectiveness is moderated by treatment duration (Scaini et al., 2016). Thus, it may be that the general pattern of decreasing anxiety observed for students in the RANX condition that was maintained or continued to decrease over the second year of the intervention would be strengthened by increasing the amount of anxiety management training in year 2.

It is important to review the findings of the present study within the context of study limitations. Most notably, the study was limited by sample size and power issues. While the original study was designed to include two cohorts of students participating in the program for 2 years each, the study was disrupted with the onset of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Thus, our sample was limited to just one of the two planned cohorts. The second cohort was contaminated because of the need to stop the study prior to completion in year 1 (cohort 2) given the lockdown and shift to virtual school following the onset of the global pandemic. Given this, we have attempted to depict both clinically meaningful findings but not necessarily statistically significant findings using effect sizes, while also noting statistically significant differences as well. The small sample size in the present study may have increased the potential for Type II error. Nonetheless, effect sizes found in this study are encouraging given their relative size compared to previously reported effect sizes for school-based anxiety interventions (Werner-Seidler et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2023). Further research will be necessary to determine if statistically significant and clinically meaningful findings are produced with a larger study sample.

Additionally, while participants in this study were relatively diverse in terms of race and sex, all participants were drawn from one suburban Southwestern U.S. school district, so it will be important for future participants to be drawn from other parts of the U.S. in order to examine whether findings are replicable in other regions of the U.S. Also as noted in Vaughn et al. (2021), the interventionists, who were not mental health providers, in the study were hired and trained by the research team. Future studies should explore how educators in the classroom can best adopt and deliver an intervention like SST with fidelity. Finally, the anxiety measures included in this study were all self-report instruments, and some had reliability estimates that were lower than expected (e.g., the MASC Separation/Panic subscale). Despite this, all estimates were above the thresholds recommended by the What Works Clearinghouse (alpha > 0.60) and consistent with prior studies using these measures. Future studies may further benefit from inclusion of external evaluator ratings of student anxiety and/or other indicators (e.g., behavioral tasks).

The mental health system in the U.S. cannot adequately provide anxiety interventions for all youth in need due to a host of factors including the fact that internalizing disorders are often overlooked (Merikangas et al., 2010a), there is a lack of mental health providers trained in evidence-based treatment (Weissman et al., 2006), and there remain substantial systemic barriers (Salloum et al., 2016). And yet, research demonstrates that certain treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral interventions, are highly effective for treating anxiety (see Crowe and McKay (2017) and Grills and Ollendick (2013) for review). Schools are often called upon to fill the treatment void, but are not given proper resources to do so (Weist et al., 2012). SST, a program based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, overcomes many of these barriers by being easily integrated into necessary educational interventions, being delivered by non-mental health providers, and demonstrating encouraging effects on various anxiety outcome measures. Overall, findings from the present study are promising and support further investigation of RANX in a large-scale, fully powered efficacy study.

Funding

National Institutes of Health Award Number R01HD087706 (PI, Grills/Vaughn) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

We report our methods related to sample size, data exclusions (if any), manipulations, and measures in the study. All data, analysis code, and research materials are available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- Ali MM, West K, Teich JL, Lynch S, Mutter R, & Dubenitz J (2019). Utilization of mental health services in educational setting by adolescents in the United States. Journal of School Health, 89(5), 393–401. 10.1111/josh.12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Ed.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer AL, & Hughes CA (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. The Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes ED, Grills AE, & Vaughn SR (2023). Relationships between anxiety, attention, and reading performance in children. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS, Beck AT, Jolly JB, & Steer RA (2005). Beck Youth inventories-Second Edition for children and adolescents manual. PsychCorp. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-methodological, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, Danielson ML, Hoenig JM, Jack D, Brody SP, Gyawali DJ, Maenner S, Warner MJ, Holland M, Perou KM, Crosby R, Blumberg AE, Avenevoli SJ, Kaminski S, Ghandour JW, & Meyer LN (2022). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2013–2019. MMWR Supplements, 71(2), 1–42. 10.15585/mmwr.su7102a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capin P, Flynn R, Fishstrom S, Grills A, & Vaughn S (2023). Integrating cognitive-behavioral therapy practices within an evidence-based reading intervention to reduce childhood anxiety and improve reading outcomes. In Margolis AE & Broitman J (Eds.), Learning disorders across the lifespan (pp. 87–108). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-031-21772-2_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey E, Devine A, Hill F, & Szűcs D (2017). Differentiating anxiety forms and their role in academic performance from primary to secondary school. PLOS ONE, 12(3), e0174418. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JM, Maughan B, Goodman R, & Meltzer H (2005). Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: Evidence for comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(5), 524–532. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Hogan TP, & Adlof SM (2005). Developmental changes in reading and reading disabilities. In Catts HW, & Kamhi AG (Eds.), The connections between language and reading disabilities (pp. 38–51). Psychology. 10.4324/9781410612052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catts HW, Herrera S, Nielsen DC, & Bridges MS (2015). Early prediction of reading comprehension within the simple view framework. Reading and Writing, 28(9), 1407–1425. 10.1007/s11145-015-9576-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AW, Langer DA, McLeod BD, Har K, Drahota A, Galla BM, Jacobs J, Ifekwunigwe M, & Wood JJ (2013). Effectiveness of modular CBT for child anxiety in elementary schools. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(2), 141–153. 10.1037/spq0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, Peris TS, Almirall D, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, Kendall PC, March JS, Gosch EA, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, Piacentini JC, McCracken JT, Keeton CP, Suveg CM, Aschenbrand SG, Sakolsky D, Iyengar S, Walkup JT, & Albano AM (2014). Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 212–224. 10.1037/a0035458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, Lloyd J, Mellor D, Nosek B, & Therrien W (2018). Promoting open science to increase the trustworthiness of evidence in special education. Exceptional Children, 85, 104–118. 10.1177/0014402918793138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden PA (2010). Social anxiety in children with disabilities. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37(4), 301. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe K, & McKay D (2017). Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety and depression. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 49, 76–87. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, Cox S, Coifman J, Mayworm A, & Lyon AR (2021). Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48(3), 420–439. 10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraldi R, Wolk CB, Locke J, & Beidas R (2015). Clearing hurdles: The challenges of implementation of mental health evidence-based practices in under-resourced schools. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 8(3), 124–140. 10.1080/1754730X.2015.1037848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BL, Allen R, & Kose G (1996). The relationship between anxiety and problem-solving skills in children with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(4), 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DA, Caruana N, Hudson JL, & McArthur GM (2019). The association between poor reading and internalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 67, 45–60. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Hudson JL, Kohnen S, Mobach L, & McArthur GM (2021). The effect of an integrated reading and anxiety intervention for poor readers with anxiety. PeerJ, 9, e10987. 10.7717/peerj.10987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, & Blumberg SJ (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256–267e3. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough PB, & Tunmer WE (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. 10.1177/074193258600700104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE (2014). Reading anxiety scale. [Unpublished instrument-available from author]. [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE (2015). The strong students toolbox: An intervention program for addressing stress/anxiety in children. [Unpublished manual]. [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, & Ollendick TH (2013). Phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn S, Barth A, Denton CA, & Stuebing KK (2014). Anxiety and response to reading intervention among first grade students. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(4), 417–431. 10.1007/s10566-014-9244-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn SR, & Bowman C (2022). Internalizing symptoms and reading difficulties among early elementary school students. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 10.1007/s10578-022-01315-w. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, Vaughn SR, Roberts G, Daniel J, Bowman C, & Richardson D (2023). The reading anxiety scale for children: Development and psychometric properties. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, Ollendick TH, & Fisak B (2008). Re-examination of the MASC factor structure and discriminant ability in a mixed clinical outpatient sample. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn SR, & Stuebing KK (2012). Anxiety and reading difficulties in early elementary school: Evidence for unidirectional- or bi-directional relations? Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 43(1), 35–47. 10.1007/s10578-011-0246-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills-Taquechel AE, Fletcher JM, Vaughn SR, Denton C, & Taylor P (2013). Anxiety and inattention as predictors of achievement in early elementary school children. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 26, 391–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland BSM, Haaland ÅT, Baste V, Bjaastad JF, Hoffart A, Rapee RM, Raknes S, Himle JA, Husabø E, & Wergeland GJ (2020). Effectiveness of brief and standard school-based cognitive-behavioral interventions for adolescents with anxiety: A randomized noninferiority study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(4), 552–564e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Coutts JJ (2020). Use omega rather than cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But… Communication Methods and Measures, 14, 1–24. 10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N, & Wigelsworth M (2016). Making the case for universal school-based mental health screening. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 21(1), 22–42. 10.1080/13632752.2015.1120051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latzman RD, Naifeh JA, Watson D, Vaidya JG, Heiden LJ, Damon JD, & Young J (2011). Racial differences in symptoms of anxiety and depression among three cohorts of students in the southern United States (Vol. 74, pp. 332–348). Interpersonal & Biological Processes. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R, Singmann H, Love J, Buerkner P, & Herve M (2020). Package ‘ emmeans.’ R Package Version 1.15–15. 10.1080/00031305.1980.10483031. License [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald KT, Cirino PT, Miciak J, & Grills AE (2021). The role of reading anxiety among struggling readers in fourth and fifth grade. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 37(4), 382–394. 10.1080/10573569.2021.1874580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGinitie WH, MacGinitie RK, Maria K, & Dreyer LG (2000). Gates-MacGinitie reading tests–Fourth edition. Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- March J (1997). Multidimensional anxiety scale for children. Multi-Health Systems Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mega C, Ronconi L, & De Beni R (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 121–131. 10.1037/a0033546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, & Koretz DS (2010a). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics, 125(1), 75–81. 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, & Swendsen J (2010b). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, Georgiades K, Heaton L, Swanson S, & Olfson M (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison GM, & Njardvik U (2019). Prevalence and gender differences of ODD, anxiety, and depression in a sample of children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(11), 1339–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]