Abstract

It is well-documented that health-harming industries and the groups they fund use a range of tactics that seek to interfere with academic research. With the development of scholarship relating to the Commercial Determinants of Health (CDoH), an increasing number of public health researchers are working to examine the activities of health-harming industries and the impacts they have on health and equity. However, there has been limited research investigating the experiences of these researchers and the range of strategies that could be used to support them. This qualitative interpretivist study involved 10 online focus groups with 28 public health researchers (ranging from PhD students to emeritus professors) in Australia and the UK. The researchers worked on issues related to the alcohol, gambling, tobacco or ultra-processed food industries. Participants outlined a range of personal and professional risks relating to their research, including social media attacks, complaints to university personnel and funders, attempts to discredit their research, legal threats and freedom of information requests. Some described the impacts this had on their overall well-being, and even on their family life. They commented that current university systems and structures to support them were variable and could differ between individuals within institutions. This often left researchers feeling isolated and unsupported. Universities should recognize the risks to researchers working on issues relating to health-harming industries. They should proactively develop strategies and resources to inform and support researchers to conduct research that is important for public health and equity.

Contribution to Health Promotion.

Health-harming industries and the groups they fund use a range of strategies and tactics to interfere with academic research.

Public health researchers face a range of challenges related to researching these industries—from social media trolling to attempts to discredit them and their research.

This article demonstrates that universities and professional associations vary in the levels of support they provide these researchers.

Some initial recommendations are provided for universities to establish effective support mechanisms and systems to create safe and protected working environments for researchers working on issues relating to health-harming industries.

BACKGROUND

The Commercial Determinants of Health (CDoH) is a rapidly growing field of research that explores the impacts of corporate and commercial actors on the health and equity of communities (McCarthy et al., 2023; Petticrew et al., 2023; Pitt et al., 2024). A recent Lancet Series (The Lancet, 2023), focus from the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2023) and health promotion agencies such as VicHealth (VicHealth, 2023), as well as national research funding agencies such as the NHMRC in Australia (NHMRC, 2023) and NIHR in the UK (NIHR, 2022), have contributed to an increasing emphasis on the CDoH as an important determinant of health. While commercial entities can contribute positively to health and society (Gilmore et al., 2023, p. 1194), most research to date has focused on exploring and documenting the strategies and impacts that health-harming industries—such as the tobacco (Amul et al., 2021; Watts et al., 2021; Gannon et al., 2023), alcohol (Babor, 2020; McCambridge et al., 2020; Stafford et al., 2020; Dumbili and Odeigah, 2023; Pitt et al., 2023; Roy-Highley et al., 2024), ultra-processed food (Chavez‐Ugalde et al., 2021; Moodie et al., 2021), fossil fuel (Bell et al., 2019; Megura and Gunderson, 2022; Arnot et al., 2024) and gambling industries (Thomas et al., 2023; Constandt and De Jans, 2024; van Schalkwyk et al., 2024)—use to promote their products and shift attention from their own role in creating health risks and harms (Reed et al., 2021). This includes using a range of strategies to influence the development of policies that have the potential to protect the health of the public and potentially negatively impact their profits (Reed et al., 2021; Pettigrew et al., 2022).

Part of this interference has included strategies designed to dispute and discredit the work and character of independent researchers and their research. This has included questioning scientific evidence, attacking study methods, manufacturing doubt about the validity of evidence and intimidating and vilifying critics (Goldberg and Vandenberg, 2021; Lacy-Nichols et al., 2022; Matthes et al., 2022; Carlini et al., 2024). Health-harming industries have also funded research to counter the findings of independent studies (Hong and Bero, 2002), and create an evidence base that emphasizes the benefits, while obscuring or downplaying the harms associated with their products (Fabbri et al., 2018). Bartlett and McCambridge (Bartlett and McCambridge, 2021) examined published responses of alcohol industry funded groups to peer-reviewed research articles, analysing the practices of such groups and the information they provide to the public about alcohol harms. While these responses questioned the accuracy of the findings, none provided what would be considered legitimate academic critique. Concerningly, academic journals, through publishing these responses, may legitimize and inadvertently bolster the credibility of these perspectives. Not all of these activities come from obvious industry actors, front groups or charities. In our experience, individuals who have accepted funding from these industries may also on occasion step into discussions (e.g. on social media or at academic conferences or scientific forums) to defend the industry, undermine industry-critical research and employ industry arguments without declaring their conflicts of interest.

Researchers have documented their own personal experiences of interference, mostly in the area of tobacco control. For example, Daube (Daube, 2015) detailed his experiences in dealing with abuse and attacks from the tobacco industry, noting the similarities he observed from the alcohol industry towards other researchers and raising concerns about increasing social media trolling and attacks. Similarly, Hastings (Hastings, 2015) reported his experience with a freedom of information (FOI) request from the tobacco industry. He described how traumatic and time-consuming these experiences can be, noting that researchers often do not have the time or capacity to dedicate to building cases to refuse requests and are unable to match the vast resources available to these industries (Hastings, 2015). Matthes and colleagues (Matthes et al., 2022) identified that interference was a key challenge for the tobacco control community in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), again highlighting threats experienced through the media and social media. In a later study, Matthes and colleagues (Matthes et al., 2023a) documented a broader range of interference tactics that had been experienced by tobacco control researchers and advocates, including attacks in the media, online harassment, legal threats, non-legal threats including death threats, burglary and theft, FOI requests and perceived or actual surveillance.

The above experiences are, of course, not unique to researchers working in the CDoH and are also present in a range of other areas where researchers are challenging the status quo or powerful actors (Tollefson, 2024). In their aptly titled paper, ‘I’m a Professor, which isn’t usually a dangerous job’, Doerfler and colleagues (Doerfler et al., 2021) argued that impactful research and ideas which upend the status quo often provoke backlash and that threats have been used as a tool to silence academics for centuries (p. 1). Along with social media harassment from a range of groups, researchers had experienced threats and intimidation, including from peers who perceived that their work was an ‘affront’ to the discipline, subsequently ostracizing these researchers (Doerfler et al., 2021). Similarly, studies with scientists who provided expert commentary on the COVID-19 pandemic have also documented a range of negative experiences ranging from attacks on their credibility and reputational damage to threats of violence, including death threats (Lacerda, 2021; Nature, 2021; O’Grady, 2022). Scientists working on climate also report experiencing online abuse relating to their own or their work’s credibility (Vidal Valero, 2023). These experiences can have significant impacts on mental health and well-being. A study investigating the experiences of prominent medical science communicators on public platforms found that 91.9% had experienced abusive behaviour, 69.3% had experienced persistent harassment, 38.6% had received complaints to their employer or professional bodies, or legal intimidation, and the majority (62.4%) reported the negative impacts of public outreach on their mental well-being including depression and anxiety (Grimes et al., 2020).

There has been some research documenting how researchers working in the CDoH respond to such industry interference (Matthes et al., 2023b). Matthes and colleagues (Matthes et al., 2023a) found that tobacco control advocates and researchers engaged in a range of responses in relation to the strategies of interference they experienced, including ignoring or exposing them. However, perhaps the most concerning finding was the ‘chilling’ effect that these attacks had on some researchers, including withdrawing from or abandoning a project, area or field of research, and what the researchers called defensive adaptation such as self-censorship (Matthes et al., 2023a, p. 8). There have been increased calls for universities and public health organizations to implement a range of support strategies, including specific training, support networks and legal services as a way to retain researchers, particularly those who are earlier in their careers (Lacy-Nichols et al., 2022; Matthes et al., 2023a). Recognizing the impact of intimidation and harassment on researcher self-censorship, SafeScience was launched in the Netherlands to help scientists find the right support in the event of threats, intimidation or hate speech, including an emergency number to call (Nature, 2023; SafeScience, 2024). The Researcher Support Consortium in the USA also recently launched a suite of resources for funders, institutions and researchers, designed to support researchers experiencing harassment and intimidation (Research Support Consortium, 2024). These initiatives are all important in helping to support the broader well-being of researchers who may be vulnerable to a range of risks associated with their research (Nature, 2021), as well as encouraging institutions to provide broader protections for their researchers (Tollefson, 2024).

The present study aims to build on the existing literature and calls for increased support for researchers by exploring the challenges faced by researchers from Australia and the UK who have worked to investigate four health-harming industries (alcohol, gambling, tobacco and ultra-processed food). The research presented in this article also considered awareness of current support systems and structures, and the areas that could be improved to provide more comprehensive support for researchers working in the CDoH. The article was guided by three research questions:

RQ1. What are the challenges experienced by researchers investigating the tactics and impacts of health-harming industries?

RQ2. What support do these researchers currently receive from their teams, colleagues and institutions?

RQ3. How could structures be improved to support these researchers more effectively?

METHODS

Approach

The data presented in this article were part of a broader experiential and interpretive qualitative study investigating the experiences of researchers in Australia and the UK working in four health-harming industries (alcohol, gambling, tobacco and ultra-processed foods). Ethical approval was received from the Deakin University Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAG-H 130_2021).

The study was guided by a reflexive approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2022). Most qualitative research in public health aims to explore, contextualize and understand people’s subjective experiences in the context of their everyday lives. Values-based and non-positivist qualitative research is commonly referred to as ‘Big Q’ qualitative research (Kidder and Fine, 1987), whereby knowledge production is theorized as ‘partial, situated and contextual’ and ‘valuing researcher subjectivity as a resource for research rather than a problem that needs to be managed’ (Braun and Clarke, 2024, p. 2).

In engaging in a reflexive approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2022), we acknowledge that our own lived experiences as researchers working to investigate the CDoH influenced how we designed this study, engaged in conversation with participants during the focus groups and approached the data analysis. As a collective, we have worked on studies across a range of health-harming industries, including but not limited to tobacco, gambling, alcohol, fossil fuels and ultra-processed foods. We are also at different stages of our academic careers (from early career researchers (ECR) to emeritus professor), which provides different perspectives on this issue. We held different roles while conducting this research (including as the Editor-in-Chief of a global health promotion journal). We have all experienced different types of interference from industry actors, those they fund and their allies. These experiences range from online trolling and abuse, including receiving aggressive and harassing emails or direct messages on social media sites, being blogged about by a range of industry actors and sympathizers, being heckled or aggressively approached by industry representatives at conferences, experiencing media attacks, threats and intimidation, funding bodies being pressured to censor research findings, being encouraged to meet or have public debates with industry representatives and having to publicly counter negative commentary about colleagues at conferences and symposiums. We have also experienced varying levels of support from our universities. This has ranged from excellent support from some heads of departments and research supervisors, Vice-Chancellors, media teams and legal departments—to no support at all.

Criteria for recruitment

To be included in this study, participants needed to be individuals who had conducted research related to the alcohol, gambling, tobacco or ultra-processed food industries and who were affiliated with a university in Australia or the UK. Participants were excluded if they had directly or indirectly received funding from any of these industries in the last 5 years. A list of potential participants was compiled based on the research team’s networks and individuals were sent email invitations for the study. Snowball sampling was then used, with researchers asked to share the study details with people who they thought might be interested in participating with a request for those interested to directly contact the team. This contributed to diversifying the sample, particularly in relation to the inclusion of PhD students and ECRs working in the specified areas.

Data collection

Data collection occurred between October and December 2021 and was conducted in two phases (an online survey and participation in a focus group). Once individuals agreed to participate, a time was organized for the online focus group, and participants were also sent a Qualtrics link to a survey to complete before the focus group.

There were two reasons for the online survey before the focus group. First, it was completed anonymously, and these data were not linked to participants’ focus group responses. This allowed participants to freely express any opinions or experiences that they may not have felt comfortable sharing in front of other participants in a focus group setting. Second, the survey included questions to prompt participants’ thinking around questions that they would be asked to elaborate on in the focus group. This also gave participants time to reflect and make an informed choice about their participation in the focus group (participants were able to withdraw from the study at any time before the focus groups had been completed). The survey included a mix of open text and tick box questions about personal characteristics (geographical region, career stage, gender, and industry they had researched), rewards and challenges of working in their field, how well supported they felt by their university and how confident they were that their university would support them if they faced a legal challenge associated with their research.

Online focus groups were chosen because of their ability to create an interactive experience between participants where they could reflect and share ideas and experiences (Marques et al., 2020). Focus groups prompted participants to confirm their own ideas but also to consider things that they might not have thought of during a one-on-one interview. Focus groups were conducted and recorded over Zoom and lasted on average 90 min. Groups were kept small (two to four participants in each, plus two facilitators) so that facilitators could easily manage the discussion, and everyone could have an opportunity to contribute. H.P. conducted all focus groups and was assisted by S.M., S.T., M.D. and M.v.S. For some focus groups, the facilitator was intentionally selected to help enhance discussions about experiences of working on specific industries (e.g. S.T. in gambling and M.D. in tobacco). Where appropriate, during the focus groups, we were also open to sharing our experiences with the participants, to build trust, and develop collective knowledge. People with similar experiences, career stages or industry interests were interviewed together. Before the focus group, the names of other participants were revealed to ensure that everyone was comfortable participating with the other people in their group (noting that this did not result in anyone withdrawing or changing groups). The intentional grouping of certain participants was also used to increase feelings of support, provide a networking opportunity and enhance discussions. The focus groups consisted of verbal discussions as well as questions that called for participants to answer in the Zoom chat function. Participants were then invited to elaborate on their written answers. This helped with facilitating the focus groups as participants did not have to wait for their turn to respond and could do so on the chat. Participants were asked to reflect on any unique challenges they had experienced working in the field, the level of support that universities provided, the current mechanisms that they used for support, and if there was anything else inside or outside the university that could be done to support CDoH researchers. Throughout the interview, participants were asked to think about the potential impacts of these issues on PhD students and ECRs.

Data interpretation

The survey data were downloaded from Qualtrics to Excel and the Zoom files from the focus groups (including the transcript and saved chat) were uploaded to NVivo 14 which was used for qualitative data management. The qualitative responses in the survey and anything that was documented in the focus group chat were also included in the qualitative analysis. Frequencies from the quantitative survey data were calculated in Excel. Transcripts were checked for accuracy by a member of the research team and corrected for any inaccuracies. Braun and Clarke’s (Braun and Clarke, 2022) reflexive thematic analysis was used as the methodological approach to guide the qualitative data interpretation. This included familiarization with the data through reading transcripts, understanding the similarities and differences within the data and spending time thinking about the different connections that were being made. Members of the research team (H.P., S.T., S.M.) talked through each focus group after they had been facilitated, which helped with the familiarization process. Coding was led by H.P. and occurred by reading the transcripts and labelling parts of the text with latent and semantic codes in relation to the research questions. Initial themes were constructed relating to the research questions, then themes were refined, finalized and named. Reflection and revision of the themes also continued through the peer review process. The broader team reflected on suggestions from the peer reviewers, including the headings of the themes, and the need to provide more nuance in the descriptions about participants’ responses. Quotes within the body of the manuscript were checked with participants before being included in the article.

RESULTS

General characteristics

Table 1 provides a description of the sample. The sample included 10 focus groups with n = 28 participants. Over half of the participants were female (n = 16; 57.1%), and most participants were based in Australia (n = 20; 71.4%). Just over one-quarter reported feeling unsupported by their university (n = 7; 25.9%). There were six senior academics who reported feeling ‘very supported’, whereas no PhD, ECRs or mid-career participants selected this response. Almost half were not confident that their university would support them if they were to face a legal challenge associated with their research (n = 12, 44.4%), this included all three PhD students and 75% of ECRs (n = 3). Participants reported a range of impacts on their mental health, including stress (n = 20; 74.1%), burnout (n = 15; 55.6%), a lack of work/life balance (n = 13; 48.1%) and impacts on their family life (n = 12; 44.4%).

Table 1:

General characteristics of the sample

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 16 (57.1) |

| Male | 12 (42.9) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 20 (71.4) |

| UK | 8 (28.6) |

| Expertise a | |

| Alcohol | 20 (71.4) |

| Tobacco | 15 (53.6) |

| Ultra-processed food | 15 (53.6) |

| Gambling | 9 (32.1) |

| Career stage | |

| PhD | 3 (10.7) |

| Early | 4 (14.3) |

| Mid | 8 (28.6) |

| Senior | 13 (46.4) |

| Challenges faced a , b | |

| Funding challenges | 24 (88.9) |

| Criticisms from industry or industry front groups | 21 (77.8) |

| Criticisms from other academics | 13 (48.1) |

| Funder influences | 12 (44.4) |

| Trolling on social media | 9 (33.3) |

| Legal challenges | 8 (29.6) |

| Influence from your institution/university | 4 (14.8) |

| Other | 6 (22.2) |

| Impacts a , b | |

| Stress | 20 (74.1) |

| Burnout | 15 (55.6) |

| Lack of work/life balance | 13 (48.1) |

| Impact on family or home life | 12 (44.4) |

| Impact on research (‘the chilling effect’ and willingness to research sensitive topics) | 11 (40.7) |

| Mental health (such as anxiety or depression) | 7 (25.9) |

| Other | 2 (7.4) |

| Supported by the university b | |

| Very unsupported | 1 (3.7) |

| Somewhat unsupported | 6 (22.2) |

| Somewhat supported | 12 (44.4) |

| Very supported | 8 (29.6) |

| Confidence in the university to support against a legal challenge b | |

| Not confident | 12 (44.4) |

| Somewhat confident | 9 (33.3) |

| Very confident | 6 (22.2) |

aCould select more than one.

b n = 27, participant did not complete these questions.

Two overarching themes were constructed from the data.

Theme one: personal and professional risks from health-harming industries and their allies

The first theme related to the range of circumstances that participants perceived created risks for them in the conduct of their research. These included letters of complaint from health-harming industries and their allies to universities, trolling on social media sites, negative media commentary, threatening letters, attempts to discredit scientific evidence from industry funded academics or organizations, legal threats, FOI requests and perceptions or concerns of surveillance.

Complaints to universities and funders

A particular form of interference was when individuals, companies or front groups made complaints about a researcher’s work. This included complaints to a researcher’s university, senior leadership teams or research funders. There were some differences in who these complaints originated from across industries. For example, some alcohol researchers were most concerned about the complaints that they had experienced from front groups (such as those completely or partially funded by the industry), while gambling and ultra-processed food researchers talked about complaints or threats made from other academics who had received funding from these industries. One researcher talked about complaints that were made to a funding body, with a request that their funding be retracted. Senior academics reported that receiving complaints was quite common in their area of work, commenting that it went hand in hand with the work that they did:

I mean that’s just a given isn’t it. It is stressful. But I think it’s really important to sort of put in a box some of the harassment and crap that you get, so that you can still protect enough time for the empirical research you’re actually doing rather than just being diverted to respond to complaint after complaint.

Trolling, media criticism and surveillance

Many participants were concerned about potential trolling or attacks on social media—which led some to not have or close down public accounts on platforms like X (formerly Twitter). Some participants talked about other academics publicly critiquing their work on social media when they thought the issues could be resolved with a direct conversation. Others were wary of industry front groups, employees or accounts that had started to follow them on social media accounts, which made them feel that these groups were reading and monitoring everything they did or said. One participant said that they had ‘come to expect’ that the head of an industry association would comment negatively about any new work that they had published. This was often perceived as an effort to publicly discredit their work.

A few participants mentioned that they felt an expectation from their universities to be on social media and to promote their work. However, they also felt that their university did not understand the potential trolling or backlash that they could face when engaging in public commentary about their work. Some more senior academics discussed being publicly criticized in the media, with journalists and commentators writing specific articles that tried to discredit them. Others reported having to deal with receiving (mostly anonymous) emails or comments about them or their work on social media:

Social media can be extremely toxic, particularly those who attack but do not reveal their true identity.

Some described the changing nature of social media over their career—particularly through platforms like X, and the impact of very personalized direct attacks:

When I first moved into [tobacco] social media wasn’t such a big thing. Like Twitter [X] wasn’t so big. Like that’s quite different because that can be quite immediate and I think it can feel quite personalized.

A few perceived that these challenges were more prominent for specific groups such as women and ECRs. Participants who were women and PhD/ECRs felt that men were more ‘blasé’ or ‘were better at hiding their anxiety’ around these issues. They thought that this could leave women to be more open to attacks because they ‘have more of like an injustice to the way that they talk about things and a frustration that somebody should be doing something’. One woman also said that they thought that women received very specific personalized attacks compared to men:

The way they [men] get attacked is definitely mean. But I don’t feel like they get called like ugly or stupid so much.

Some male participants (mid-career and senior) also reflected on the increased risk social media posed for ‘the generational cohort behind me’, many of whom were women, and discussed that they saw this as a challenge for younger generations who were entering the field. They thought this was contributing to people contemplating their research topic or reducing how much engagement they had online. One senior participant believed that some groups were at a much greater risk of experiencing ‘misogyny’ or abuse:

But it is very, very clear that young female researchers or female researchers of any age get it [attacks and scrutiny] much more, and particularly women of colour.

Legal threats and FOI requests

Some researchers have experienced legal threats and FOIs. This caused significant stress but was also conceptualized by some researchers as an interference strategy designed to deter the researcher from their work. Legal threats and FOIs took up time and financial resources. Some commented that they were worried about potential threats of legal action and talked about a range of strategies they used to consider this when conducting their research. For example, some researchers described being extra cautious about posting on social media and felt they had to be overly careful about any statements that they made in academic papers or reports:

I don’t know how many times I checked and double checked and triple checked that paper because I just knew that I didn’t want it to be really easily torn apart by some lovely person in the [Front group organisation].

A few said they routinely sought legal advice in relation to their research. They had become more cautious about their reporting of research after they had heard about the experiences of other researchers. ECRs and PhD students relied on the advice and expertise of senior researchers in carefully reviewing papers and providing advice about content to help minimize risk:

Sometimes it can feel very like ‘oh I don’t know if I can say that’ or ‘I need to find a softer way of putting that down on paper’.

Navigating industry capture of research spaces

Another challenge related to researchers trying to avoid spaces that they felt had been influenced by industry actors. Some were concerned about establishing collaborations with colleagues who were directly or indirectly funded by health-harming industries. Researchers found this particularly concerning when they knew of the long-lasting reputational damage that could occur if they worked with industry-funded individuals, or accepted funding from industry-funded organizations.

ECRs described the difficulties they experienced having to try and avoid work opportunities that were associated with the industry, when sometimes these relationships were not obvious or clear to them. This included finding journals to publish in that did not routinely publish research funded by health-harming industries, or who would not send their articles out to industry friendly peer reviewers. Some participants commented that they were wary of specific journals that had editors or editorial board members who had received funding from health-harming industries. Some areas of research, such as gambling, appeared to experience more challenges with academic publishing than others. There were comparisons made between challenges with transparency around conflicts of interest in gambling as compared to other areas:

Your experience with gambling doesn’t sound like the experience that I’m familiar with in alcohol. I don’t publish a lot in journals but I think we’re spoiled for choice in terms of where we could publish alcohol work.

Senior academics talked about a broad range of experiences in trying to avoid spaces where there were industry interests. This included trying to explain the importance of implementing conflicts of interest protocols within institutions that had staff with opposing views. Another issue was the lack of formal documentation that systematically monitored people’s funding and affiliations. Although this was an issue across all health-harming industries, gambling was specifically mentioned as being an area where it was difficult to know who had industry links. Others described having to navigate people in positions of power within their university who were linked with health-harming industries or industry funding, and front group members on ethics committees which could cause problems for the successfulness of their careers and projects.

Theme two: building support structures for researchers investigating health-harming industries

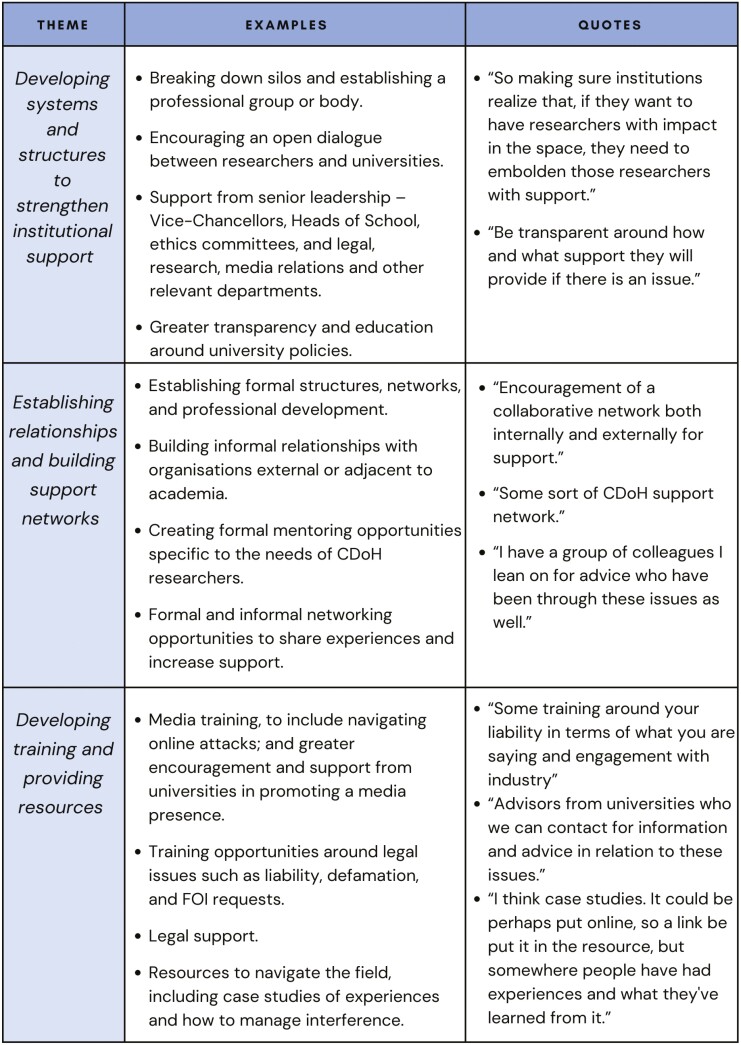

Participants recommended a range of strategies that they thought would be effective in supporting researchers investigating the practices and impacts of health-harming industries. Recommendations from participants are summarized in Figure 1 and expanded in the text below.

Fig. 1.

: Summary of recommendations and quotes.

Developing systems and structures to strengthen institutional support

Participants recommended a range of mechanisms that could break down the silos between researchers studying different health-harming industries, with the aim of developing structures and systems to protect both researchers and their research. It was acknowledged that breaking down silos was a concept often discussed within public health but that there were very few practical strategies to action this. Some recommended the establishment of a professional body or group to overcome this:

A professional body/support groups to provide advice/materials but also to create a more unified and cohesive ‘front’ for the research we do.

Part of this included having an open dialogue with senior university leaders (including ethics committees and legal departments) about the challenges and risks that are faced by researchers working in this space. This included direct conversations with Vice-Chancellors, heads of department, ethics departments, media teams and research offices, as they were often the people who would receive complaints from industry and industry-associated front groups. Support from senior leadership was seen as particularly important for those who had experienced industry interference. For example, one participant spoke about the comfort they felt when their Vice-Chancellor called them personally to ask how they were after experiencing industry interference. Some stated that university support was more than just protecting researchers but also about protecting the research that they were conducting:

It’s not just protecting you as a researcher it’s protecting the research. The industry only want access to data and things like that for their own commercial interest so there’s ethical reasons why universities should protect the research, beyond just protecting its staff.

Participants believed that in order for universities to better support researchers, there needed to be greater transparency in relation to protocols and policies for researchers working in this area. Many researchers did not know what level of support they could expect from their university or senior leaders. Some stated that there needed to be strong formal commitments to protect researchers and for there to be an acknowledgement of the responsibilities of both universities and researchers:

Commitments from universities to protect researchers in the event that they are threatened. Advisors from universities who we can contact for information and advice in relation to these issues.

I think acknowledging the responsibilities the university have. Clarifying what the responsibilities of the researchers are as well. Being aware of what the potential risks are and having consultancy legal advice available within the university.

Establishing relationships and building support networks

Participants discussed the need to establish formal and informal support and mentoring networks for researchers working in areas related to health-harming industries. Some suggested it would be useful to have more formal structures, networks and professional development opportunities to learn about the experiences of and strategies used by researchers working in other areas of scholarship—for example how environmental scientists had dealt with trolling or navigating legal attacks. Some discussed how effective it had been to establish collaborations with colleagues in law faculties who could help them understand defamation or FOIs. Building informal relationships with other organizations adjacent or external to academia including government departments, politicians or advocacy groups was also recommended as a source of additional support, resources or advice when it might be outside the scope of universities:

Greatest support for research in this area - some politicians who get it, senior people outside of the academy, e.g. community leaders, community people who get it.

Formal mentoring structures were also thought to be particularly important for PhD students and ECRs. Participants acknowledged that mentoring programs were common in the university system but were not necessarily focused on understanding issues that might arise when dealing with health-harming industries.

I had a lot of mentoring from [my supervisors] and that was really important. Once I came in [to research], it didn’t put me off, but that was because of the institutional support and the mentoring. I’d like to think it’d be the same for others, but I don’t know. I suspect it varies a lot.

Many senior academics described how useful it had been to have mentors and supportive colleagues who they could talk to about stressors and ways for ‘self-protection’. Participants recalled positive experiences of support when experiencing attacks including when colleagues had called them up to check in on them. Due to the recognized importance of this, they were also very open to being mentors and a source of support for others working in the field to ensure that people did have someone to talk to. Senior academics also spoke of turning to dedicated groups of people for advice and to discuss the issues with like-minded people across research institutions and faculties to build solidarity:

I have a group of colleagues I lean on for advice who have been through these issues as well.

Like mentoring, participants also wanted to see more formal or informal networking opportunities. This was also recognized as something that was already available through universities but was not specific to the needs of researchers working on issues related to health-harming industries. Participants often commented that providing information to researchers was important in raising awareness about the issues that they may face but also to empower them to be able to prevent and navigate any issues that they may encounter:

When shit hits the fan, you need people to rally around you. It’s pretty upsetting having personal stuff in the [newspaper] and you do need that scaffolding. So I think it doesn’t have to be complicated even just FAQs. But I think how to deal with social media, publications, just ways to protect yourself. Because we don’t want to scare people away, we want to empower them.

ECRs and PhD researchers, in particular, thought that having a group that they could call on for support would be effective in building confidence and feelings of morale. Some participants noted that even participating in this study had helped them connect with researchers who were at a comparable career stage and who were going through similar challenges:

A wider support network or better networking activities from year one of PhD. Researching sensitive topics can be incredibly isolating when researchers in your department are not experiencing the same phenomenon. A safe space to share concerns or network of like-minded researchers would provide better support.

Developing training and providing resources

Participants recommended that practical training and resources were needed to help support researchers. Participants thought that more support was needed about how to navigate social media trolling or negative attention online.

I think it would be useful to have some guidance around that and what you need to be careful about saying. And just be mindful because I mean, most of us don’t have legal training we’re researchers. So you don’t maybe always understand what the potential implications are with what you’re putting out there publicly. With social media it’s there in black and white, so people can screenshot it, whatever, and you know you can’t take back what you’ve said.

Some stated that there was a tension between university expectations and the experiences of researchers. For example, many researchers stated that universities now expected their researchers to engage in more media activity and dissemination of their research on social media platforms. However, researchers also felt there was limited support if they received trolling or negative attacks because of their media presence. Some participants, mostly from Australia, discussed that their universities had excellent social media strategies to mitigate some of these risks. These included having designated social media teams who could take over social media accounts, and having policies and agreements within their team or department not to respond to trolls or engage with people trying to discredit their work. One participant recommended having university-level accounts that could be used to post any content that might be considered controversial or sensitive to avoid having a single person as the face of the post.

Participants also wanted more training that explained concepts relating to liability, defamation and FOI requests. Participants stated that this type of training would help researchers understand the risks they were taking. However, there were some researchers who thought that training did not go far enough and wanted a greater commitment from universities to provide legal support if legal threats were made—‘We need extra legal support’. Others were interested in smaller-scale commitments such as a service that could be used to check over the content of publications, help to prepare for government inquiries or public speaking roles and talk through any risks that might be involved in the development of a research project. While some were reported as being available to researchers in the UK, most Australian researchers felt that their universities did not, or would not be willing to provide this level of support:

[The university] provided legal support to legally check articles before we submitted them, and that was really good. [At another university] it was harder to access that kind of support. I can imagine feeling that the support might not exist in the same way and if you haven’t got like someone who’s legally qualified checking what you’re saying before you submit it I feel like you’re more open [to attacks]. When you’re making particular claims about companies, I think you’ve got to be really careful. So I think it’s really important that institutions provide that.

Some felt that a platform or website that contained various resources would help researchers navigate the field. Researchers thought this could include a range of training, case studies on researchers’ experience, and awareness raising through information about mechanisms of industry interference:

I think a simple guide for early career researchers is definitely something that would be useful.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to document the experiences of researchers in Australia and the UK who were studying the practices of four health-harming industries, with a particular focus on industry interference. The study then explored the support mechanisms available to researchers and how they could be improved.

Participants, typically those who were more senior, had experienced a broad range of interference tactics from health-harming industries and their allies. These experiences were similar to those documented in studies focused specifically on tobacco control advocates (Matthes et al., 2022; Matthes et al., 2023a). Industry interference tactics appear to be similar for those working in a range of academic and non-academic roles related to health-harming industries. Understanding the broader impact of these interference strategies will be essential in CDoH scholarship examining the corporate playbook, and the range of strategies that can be developed to respond. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) explicitly recognizes the covert strategies of the tobacco industry. While there are an increasing number of global reports drawing attention to the CDoH and the tactics of specific industries, there is perhaps not the same emphasis on covert strategies as has been so clearly documented in the FCTC. CDoH (and specific industry) reports rarely consider the experiences of researchers and advocates, and we would argue that this is a significant omission. There is a responsibility for organizations who are promoting increased scholarship and policy attention to the CDoH (including those seeking to attract PhD students and other researchers to this area of scholarship) to ensure that they are also advocating for robust mechanisms to protect and empower the CDoH workforce in the face of powerful vested interests. While our study considered the experiences of researchers in two high-income countries, we note that there is a particular need for skill development and networks for researchers in LMICs who may not have the same support infrastructure to counter powerful vested interests (Matthes et al., 2020).

There were many similarities in researcher experiences across different areas of scholarship. This included social media trolling and attempts to discredit research—which has also been documented in other studies (Vidal Valero, 2023; Nature, 2021). This raises a broader issue for universities. While researchers are increasingly encouraged to engage in public-facing activities to disseminate their research, there are still few structures in place to formally support them in the face of increasingly problematic social media (and media) practices towards researchers and scientists (Nogrady, 2024a). The findings from this study also suggest that concerns relate not only to the amount but also to the type of trolling that individuals receive on social media platforms, with women at particular risk of very personalized comments and abuse. These experiences can be particularly isolating and distressing for women (Vidal Valero, 2023)—especially if they are given messages that these types of attacks are ‘part of the job’. Recognizing different experiences, and how to tailor mechanisms to support those who may be more vulnerable to personalized attacks will be an important part of developing the CDoH workforce moving forward.

In a recent successful employment legal case, microbiologist Siouxsie Wiles argued that the University of Auckland had failed to protect her against social media abuse related to her commentary about COVID-19, and that the university policy was not ‘fit for purpose’ (Nogrady, 2024b). One of the points of contention between Wiles and the university was whether her public commentary was part of her employment or ‘outside activities’. The court ruled in favour of Wiles, however, similar issues were also raised by researchers in this study. Many were unclear about the type of support that they could expect from their university, including legal support. There were also variations across universities about the type and extent of the support provided—which could change according to who were in positions of leadership.

An editorial in the journal Nature (Nature, 2022) recently called for universities to provide increasing support for researchers who had been threatened and targeted online, publishing a toolkit of practical steps that researchers could take to protect themselves. We would argue that universities have a duty of care to protect their researchers and agree that there is an urgent need for universities to ensure that the threats that are made towards researchers and their research are taken seriously. This must include an increased dialogue between universities and researchers working on issues that may have a range of personal and professional risks to develop strategies and policies to prevent and minimize any harm to researchers and their research. Researchers recommended strategies including training and resources, but also that universities have a clear understanding of the specific risks that researchers working on issues related to health-harming industries face. This may include universities increasing transparency around their own funding and conflicts of interest, rethinking some aspects of the systems and structures that currently exist within universities, and investigating why so many researchers feel unsupported by these structures. There may also be a role for professional organizations to provide guidance and resources that can be implemented across universities.

It is also important to recognize the impacts that industry interference can have on the broader mental health and well-being of researchers. Participants in this study reported experiencing stress, burnout and a lack of work/life balance, although many were reluctant to elaborate on these issues in focus groups. While there may be broad narratives about needing to be ‘tough’ in the face of powerful industries, we should not create a narrative that interference, attacks and abuse are an acceptable price that researchers need to pay for this component of their work. Academics already experience high levels of mental stress (Mark and Smith, 2018; Nicholls et al., 2022). We should be conscious that not all researchers want to engage in public advocacy and that while there are many rewards to working in the CDoH, there is also a range of risks that may be stressful for researchers and their families.

One contributing factor to stressors may be that researchers are often uninformed or unaware of risks. While some supervisors may take time to explain and provide guidance about these issues, this research shows this is not always the case. There were suggestions of resources and greater information to specifically support PhD students or researchers who were stepping into the CDoH. Universities should take a more proactive approach which anticipates risk, develops more formal training and educational materials and ensures that researchers have adequate access to legal and wellbeing support. This could help ensure that people feel more prepared before any strategies of interference arise, rather than waiting until something happens. This may also help to alleviate immediate feelings of stress and uncertainty when problems do arise.

We should also remember that the influencing of science is a key industry strategy which aims to promote industry experiences at the expense of public health (Legg et al., 2021). While there is growing research interest in a range of commercial practices, the intimidation and discrediting of researchers is still rarely studied empirically. It is important to shine a spotlight on this area of interference as much as other practices to ensure that the production of independent knowledge is protected in order to promote health and equity.

Limitations

There were three limitations to consider for this study. First, was only including researchers exploring the areas of alcohol, gambling, tobacco, and ultra-processed food. While there were reasons for this, such as the fact that there is a significant crossover between researchers typically working across these areas, it meant that we did not gather experiences from people working on issues related to other industries that have exhibited industry interference such as fossil fuels, pharmaceuticals or the arms industries. Second, researchers were only included from Australia and the UK. Further research should build on already important research conducted by Matthes and colleagues (Matthes et al., 2022) in different cultural and geographic contexts. Third, this study focused on the experiences of academic researchers and how universities could be used as a mechanism for support. There may be a range of further perspectives and experiences from those working broadly in public health advocacy including but not limited to lived experience groups, health promotion organizations, not for profits, and local governments that will also be important to understand.

CONCLUSION

This study outlines the range of challenges faced by Australian and UK researchers working to investigate the tactics and outcomes of health-harming industries, and the range of structures universities could provide to ensure researchers feel protected and supported. Universities need to do more to ensure the health and well-being of their researchers and provide opportunities for researchers at all levels, from PhD and ECRs onwards, to raise concerns and contribute to the development of support structures. This will not only bring direct benefits for the researchers themselves but will also enhance the public health and broader CDoH field by encouraging and retaining researchers who conduct high-quality research that protects and promotes the health of communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the participants for sharing their experiences.

Contributor Information

Hannah Pitt, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria, 3220, Australia.

Samantha Thomas, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria, 3220, Australia.

Simone McCarthy, Institute for Health Transformation, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, 1 Gheringhap Street, Geelong, Victoria, 3220, Australia.

May C I van Schalkwyk, Department of Health Services Research and Policy, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Mark Petticrew, Department of Public Health, Environments and Society, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK.

Melanie Randle, Faculty of Business and Law, University of Wollongong, Northfields Avenue, Wollongong, New South Wales, 2500, Australia.

Mike Daube, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Kent Street, Bentley, Western Australia, 6102, Australia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.P.: Conceptualization of the study, data collection and analysis, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions. S.T.: Conceptualization of the study data collection and analysis, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions. S.M.: Data collection and analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. M.v.S.: Conceptualization of the study, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions. M.P.: Conceptualization of the study, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions. M.R.: Drafting and critical revisions. M.D.: Conceptualization of the study, data collection and analysis, drafting of the manuscript and critical revisions.

FUNDING

This project was funded by the Deakin University Cat 1 Seed Funding Scheme and as part of ARC DP210101983. H.P. is funded by a VicHealth Early Career Research Fellowship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

H.P. has received funding for research on the CDoH from the Australian Research Council, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, NSW Office of Responsible Gambling, VicHealth and Deakin University and VicHealth. S.T. has received funding for research on the CDoH from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Scheme, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Healthway and the New South Wales Office of Responsible Gambling, VicHealth and Deakin University. S.M. has received funding for research on the CDoH from Deakin University and VicHealth. M.v.S. was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Fellowship (NIHR3000156) and her research was also partially supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North Thames. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. M.v.S. and M.P. have received funding through and are co-investigators, respectively, in the SPECTRUM consortium which is funded by the UK Prevention Research Partnership (UKPRP), a consortium of UK funders [UKRI Research Councils: Medical Research Council (MRC), Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Natural Environment Research Council (NERC); Charities: British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Wellcome and The Health Foundation; Government: Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office, Health and Care Research Wales, National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and Public Health Agency (NI)]. M.P. has grant funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ‘Three Schools’ Mental Health Programme. M.R. has received funding for research on the CDoH from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Scheme and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. M.D. has received funding for gambling research from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant Scheme, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Grants Scheme and Healthway.S.T. is the Editor-in-Chief for Health Promotion International. H.P. and M.v.S. are on the editorial board at Health Promotion International, M.v.S. is a guest editor on the CDoH special issue. M.D. is the Chair of the Board at Health Promotion International. M.P. is on the Advisory Board of Health Promotion International. S.M. is the Social Media Coordinator for Health Promotion International. None of the authors were involved in the review process nor in any decision-making on the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data are not available.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval was obtained from the Deakin University Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAG-H 130_2020).

REFERENCES

- Amul, G. G. H., Tan, G. P. P. and Van Der Eijk, Y. (2021) A systematic review of tobacco industry tactics in Southeast Asia: lessons for other low-and middle-income regions. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10, 324–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, G., Pitt, H., McCarthy, S., Warner, E. and Thomas, S. (2024) ‘You can’t really separate these risks, our environment, our animals and us’: Australian children’s perceptions of the risks of the climate crisis. Health Promotion International, 39, daae023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor, T. F. (2020). The arrogance of power: alcohol industry interference with warning label research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81, 222–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, A. and McCambridge, J. (2021) Appropriating the literature: alcohol industry actors’ interventions in scientific journals. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 82, 595–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S. E., Fitzgerald, J. and York, R. (2019) Protecting the power to pollute: identity co-optation, gender, and the public relations strategies of fossil fuel industries in the United States. Environmental Sociology, 5, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2022) Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publishing, London. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2024). A critical review of the reporting of reflexive thematic analysis in Health Promotion International. Health Promotion International, 39, daae049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, B. H., Kellum, L. B., Garrett, S. B. and Nims, L. N. (2024) Threaten, distract, and discredit: cannabis industry rhetoric to defeat regulation of high-THC cannabis products in Washington State. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 85, 322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez‐Ugalde, Y., Jago, R., Toumpakari, Z., Egan, M., Cummins, S., White, M.. et al. (2021). Conceptualizing the commercial determinants of dietary behaviors associated with obesity: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretative synthesis. Obesity Science & Practice, 7, 473–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constandt, B. and De Jans, S. (2024) Insights into the Belgian gambling advertising ban: the need for a comprehensive public policy approach. Health Promotion International, 39, daae116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daube, M. (2015). Targets and abuse: the price public health campaigners pay. Med J Aust, 202, 294–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler, P., Forte, A., De Cristofaro, E., Stringhini, G., Blackburn, J. and McCoy, D. (2021) ‘I’m a Professor, which isn’t usually a dangerous job’: internet-facilitated harassment and its impact on researchers. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5, 1–32.36644216 [Google Scholar]

- Dumbili, E. W. and Odeigah, O. W. (2023) Alcohol industry corporate social responsibility activities in Nigeria: implications for policy. Journal of Substance Use, 29, 949–955. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, A., Lai, A., Grundy, Q. and Bero, L. A. (2018) The influence of industry sponsorship on the research agenda: a scoping review. American Journal of Public Health, 108, e9–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon, J., Bach, K., Cattaruzza, M. S., Bar-Zeev, Y., Forberger, S., Kilibarda, B.. et al. (2023) Big tobacco’s dirty tricks: seven key tactics of the tobacco industry. Tobacco Prevention & Cessation, 9, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H.-J.. et al. (2023) Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet (London, England), 401, 1194–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, R. F. and Vandenberg, L. N. (2021) The science of spin: targeted strategies to manufacture doubt with detrimental effects on environmental and public health. Environmental Health, 20, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, D. R., Brennan, L. J. and O’Connor, R. (2020) Establishing a taxonomy of potential hazards associated with communicating medical science in the age of disinformation. BMJ Open, 10, e035626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, G. (2015) We got an FOI request from Big Tobacco—here’s how it went. The Conversation, 31st August https://theconversation.com/we-got-an-foi-request-from-big-tobacco-heres-how-it-went-46457 (last accessed 25 July 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M.-K. and Bero, L. A. (2002) How the tobacco industry responded to an influential study of the health effects of second-hand smoke. BMJ, 325, 1413–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder, L. H. and Fine, M. (1987) Qualitative and quantitative methods: when stories converge. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1987, 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda, M. (2021) ‘I had to be with bodyguards with guns’—attacks on scientists during the pandemic. Nature Medicine, 27, 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy-Nichols, J., Marten, R., Crosbie, E. and Moodie, R. (2022) The public health playbook: ideas for challenging the corporate playbook. The Lancet Global Health, 10, e1067–e1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. (2023) Commercial determinants of health [Online]. Available: https://www.thelancet.com/series/commercial-determinants-health (last accessed 04 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Legg, T., Hatchard, J. and Gilmore, A. B. (2021) The science for profit model—how and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice. Plos One, 16, e0253272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark, G. and Smith, A. (2018) A qualitative study of stress in university staff. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5, 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, I. C. D. S., Theiss, L. M., Johnson, C. Y., McLin, E., Ruf, B. A., Vickers, S. M.. et al. (2020) Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collection in a global pandemic. The American Journal of Surgery, 221, 918–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, B. K., Alebshehy, R. and Gilmore, A. B. (2023a) ‘They try to suppress us, but we should be louder’: a qualitative exploration of intimidation in tobacco control. Globalization and Health, 19, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, B. K., Kumar, P., Dance, S., Hird, T., Carriedo Lutzenkirchen, A. and Gilmore, A. B. (2023b) Advocacy counterstrategies to tobacco industry interference in policymaking: a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature. Globalization and Health, 19, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, B. K., Robertson, L. and Gilmore, A. B. (2020) Needs of LMIC-based tobacco control advocates to counter tobacco industry policy interference: insights from semi-structured interviews. BMJ Open, 10, e044710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes, B. K., Zatoński, M., Alebshehy, R., Carballo, M. and Gilmore, A. B. (2022). ‘To be honest, I’m really scared’: perceptions and experiences of intimidation in the LMIC-based tobacco control community. Tobacco Control, 33, 38-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge, J., Kypri, K., Sheldon, T. A., Madden, M. and Babor, T. F. (2020) Advancing public health policy making through research on the political strategies of alcohol industry actors. Journal of Public Health, 42, 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, S., Pitt, H., Hennessy, M., Njiro, B. J. and Thomas, S. (2023) Women and the commercial determinants of health. Health Promotion International, 38, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megura, M. and Gunderson, R. (2022) Better poison is the cure? Critically examining fossil fuel companies, climate change framing, and corporate sustainability reports. Energy Research & Social Science, 85, 102388. [Google Scholar]

- Moodie, R., Bennett, E., Kwong, E. J. L., Santos, T. M., Pratiwi, L., Williams, J.. et al. (2021) Ultra-processed profits: the political economy of countering the global spread of ultra-processed foods—a synthesis review on the market and political practices of transnational food corporations and strategic public health responses. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 10, 968–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nature. (2021) COVID scientists in the public eye need protection from threats. Nature, 598, 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nature. (2022) Zero tolerance for threats against scientists. Nature, 609, 220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nature. (2023) Why Dutch universities are stepping up support for academics facing threats and intimidation [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00125-x (last accessed 09 July 2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHMRC. (2023) Targeted Calls for Research: Commercial determinants of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health 2023 [Online]. Available: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/funding/find-funding/targeted-calls-research-commercial-determinants-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-2023 (last accessed 02 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, H., Nicholls, M., Tekin, S., Lamb, D. and Billings, J. (2022) The impact of working in academia on researchers’ mental health and well-being: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PloS One, 17, e0268890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIHR. (2022) Everyone’s business: Understanding the commercial determinants of mental ill health [Online]. Available: https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/news-and-events/blog/everyones-business-understanding-the-commercial-determinants-of-mental-ill-health/ (last accessed 09 July 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Nogrady, B. (2024a) Harassment of scientists is surging—institutions aren’t sure how to help. Nature, 629, 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogrady, B. (2024b) Microbiologist wins case against university over harassment during COVID. Nature, 12th July. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-02256-1 (last accessed 15 July 2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, C. (2022) In the line of fire. Science, 24th March. https://www.science.org/content/article/overwhelmed-hate-covid-19-scientists-face-avalanche-abuse-survey-shows [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M., Glover, R. E., Volmink, J., Blanchard, L., Cott, É., Knai, C.. et al. (2023) The Commercial Determinants of Health and Evidence Synthesis (CODES): methodological guidance for systematic reviews and other evidence syntheses. Systematic Reviews, 12, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, S., Coyle, D., McKenzie, B., Vu, D., Lim, S. C., Berasi, K.. et al. (2022) A review of front-of-pack nutrition labelling in Southeast Asia: industry interference, lessons learned, and future directions. The Lancet Regional Health-Southeast Asia, 3, 100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., McCarthy, S. and Arnot, G. (2024) Children, young people, and the commercial determinants of health. Health Promotion International, 39, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, H., McCarthy, S., Keric, D., Arnot, G., Marko, S., Martino F.. et al. (2023) The symbolic consumption processes associated with ‘low-calorie’ and ‘low-sugar’ alcohol products and Australian women. Health Promotion International, 38, daad184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, G., Hendlin, Y., Desikan, A., MacKinney, T., Berman, E. and Goldman, G. T. (2021) The disinformation playbook: how industry manipulates the science-policy process—and how to restore scientific integrity. Journal of Public Health Policy, 42, 622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Support Consortium. (2024) Researchers increasingly face campaigns of intimidation and harassment. They need your support. [Online]. Available: https://researchersupport.org/ (last accessed 31 October 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Highley, E., Körner, K., Mulrenan, C. and Petticrew, M. (2024) Dark patterns, dark nudges, sludge and misinformation: alcohol industry apps and digital tools. Health Promotion International, 39, daae037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SafeScience. (2024) About ScienceSafe [Online]. Available: https://www.wetenschapveilig.nl/en/about-us (last accessed 09 July 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, J., Kypri, K. and Pettigrew, S. (2020) Industry actor use of research evidence: critical analysis of Australian alcohol policy submissions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81, 710–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S., van Schalkwyk, M. C., Daube, M., Pitt, H., McGee, D. and McKee, M. (2023) Protecting children and young people from contemporary marketing for gambling. Health Promotion International, 38, daac194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, J. (2024) Harassed? Intimidated? Guidebook offers help to scientists under attack. Nature, 20th September https://www-nature-com.ezproxy-f.deakin.edu.au/articles/d41586-024-03104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, M. C., Hawkins, B., Petticrew, M., Maani, N., Garde, A., Reeves, A.. et al. (2024) Agnogenic practices and corporate political strategy: the legitimation of UK gambling industry-funded youth education programmes. Health Promotion International, 39, daad196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VicHealth. (2023) The Next 10 Years 2023-2033. Reshaping Systems Together for a Healthier, Fairer Victoria. VicHealth, VIC, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal Valero, M. (2023) Death threats, trolling and sexist abuse: climate scientists report online attacks. Nature, 616, 421. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01018-9 (last accessed 31 August 2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts, C., Burton, S. and Freeman, B. (2021) ‘The last line of marketing’: covert tobacco marketing tactics as revealed by former tobacco industry employees. Global Public Health, 16, 1000–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2023) Commercial determinants of health [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health (last accessed 02 June 2024). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not available.