Abstract

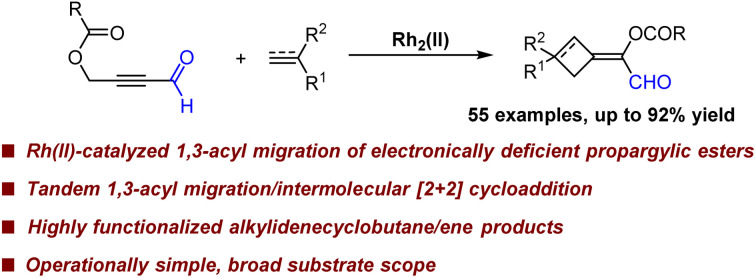

Transition metal-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters represents one of the most straightforward routes to access allene intermediates, which could engage in various fascinating subsequent transformations. However, this process is often limited to propargylic esters with electron-donating groups due to intrinsic electronic bias, and the subsequent intermolecular reactions are quite limited. Herein, we disclosed an unprecedented Rh2(ii)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of electron-deficient propargylic esters, followed by intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition with readily available alkenes and alkynes, and a large array of valuable alkylidenecyclobutane/ene scaffolds could be obtained facilely in one pot. Mechanistic studies revealed that the allene generated from Rh2(ii)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic carboxylates is the key intermediate. Control experiments and NMR data indicated that the formyl group at the terminus of propargylic esters is crucial and the cooperative interactions between the substrate and the carboxylate ligand possibly play significant roles in this reaction.

Herein, we disclosed a tandem Rh(ii)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration/intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient propargylic esters with simple alkenes and alkynes, affording various valuable alkylidenecyclobutane/ene scaffolds.

Introduction

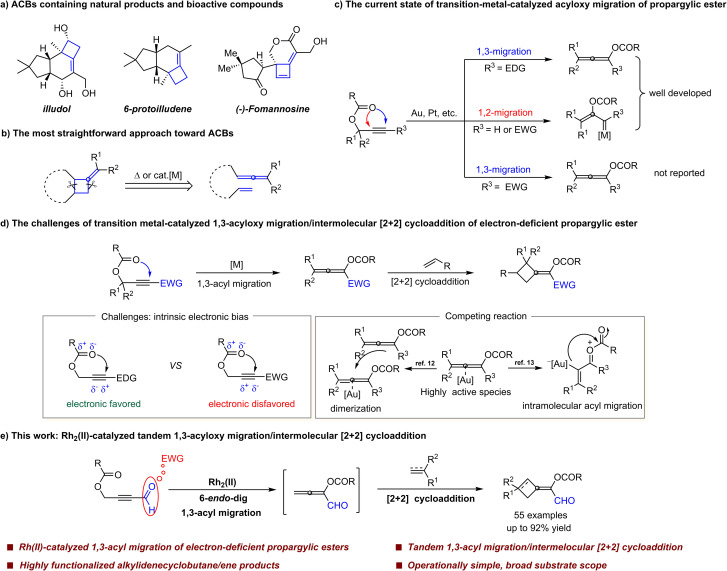

Alkylidenecyclobutane (ACB), an intriguing structural motif containing a double bond and a cyclobutane ring, is widely present in the cores of natural products and bioactive compounds (Scheme 1a).1 Additionally, due to the presence of two reactive groups and their high ring-strain energy, ACB acts as a versatile synthon to participate in a variety of transformations such as ring expansions2 and rearrangements.3 Consequently, the development of efficient access to ACB is of continuous interest to the synthetic community. In this regard, [2 + 2] cycloaddition of allenes with alkenes has proven to be one of the most straightforward and atom-economical approaches (Scheme 1b). Many elegant systems including transition metal catalysis,4 Lewis acid catalysis5 and thermal induced conditions6 have been developed. However, most of these reported strategies required pre-synthesized allene substrates that are sensitive compounds to handle.

Scheme 1. The significance of ACB skeletons and synthetic methods of ACBs. (a) ACBs containing natural products and bioactive compounds. (b) The most straightforward approach toward ACBs. (c) The current state of transition-metal-catalyzed acyloxy migration of propargylic ester. (d) The challenges of transition metal-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration/intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient propargylic ester. (e) This work.

Propargylic carboxylate is a significant structural motif that has been studied extensively in transition-metal catalysis, allowing access to a variety of functional structures.7 Among them, transition metal-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters to form allene intermediates is one of the most important transformations.8 However, this process is affected profoundly by the substitution pattern of the propargyl moiety due to intrinsic electronic bias.7c,8 In general, sterically and/or electronically unbiased substrates (R3 = alkyl or aryl) undergo reactions via an initial 1,3-acyloxy migration, while biased substrates (R3 = H or EWG) prefer 1,2-acyloxy migration leading to the vinyl carbene intermediate. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of 1,3-acyloxy migration of electron-deficient propargylic esters (Scheme 1c). Although transition metal-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters was discovered several decades ago,9 their synthetic applications in cycloaddition reactions still lag behind.7c In 2005, Zhang and coworkers developed an elegant tandem Au(i)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration/intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of propargyl esters with indoles.10 Subsequently, Chan et al. disclosed a conceptually related transformation of 1,7-enyne benzoates, which regioselectively and stereoconvergently constructed highly functionalized azabicyclo[4.2.0]oct-5-enes.11 Recently, Zhao et al. also reported an intramolecular cascaded reaction of dipropargylphosphonates to deliver bicyclo[5.2.0]-phosphonates under Ag/Co relay catalysis.4e Among these, the substrate scope of 1,3-acyloxy migration is limited to propargylic esters with electron-donating groups due to intrinsic electronic bias (Scheme 1d, left). In terms of reaction type, they are limited to follow-up intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions. In contrast to intramolecular reactions, much less attention was given to tandem 1,3-acyloxy migration/intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions, which, in principle, are more challenging. This could be because the π-acidic metals, such as gold complexes, have the ability to further activate the generated allene intermediate for dimerization12 or intramolecular acyl migration,8,13 which are possibly nonnegligible competing reactions (Scheme 1d, right). Therefore, developing a reliable catalytic system, which can trigger the 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic carboxylates without causing any undesired reactions of allene itself, is highly desirable for a one-pot intermolecular reaction.

In our previous work on Rh2(ii)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of enynal,14 enyone,15 diynal,16etc.,17 we found that the electron-withdrawing group (CHO) in enyne substrates plays dual roles, one is to activate alkyne for the cyclopropanation reaction; the other is to introduce the C–H⋯O interaction between the substrate and the catalyst. DFT studies further indicated that 6-endo-dig cyclization is more favorable than 5-exo-dig cyclization due to the presence of a six-membered ring made up of hydrogen bonding.14a Inspired by this, we wondered whether the versatile formyl group could be introduced into propargylic esters to achieve 1,3-acyloxy migration of electron-deficient propargylic carboxylates. Herein, we disclose an unprecedented Rh2(ii)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration of electron-deficient propargylic carboxylates, followed by intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition with alkenes or alkynes. This method provides efficient access to a diversity of highly desirable highly-functionalized alkylidenecyclobutanes and alkylidenecyclobutenes (Scheme 1e).

Results and discussion

Optimization study

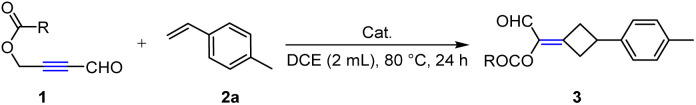

To start this investigation, the propargylic ester 1a and p-methylstyrene 2a were selected as model substrates for optimization of the reaction conditions (Table 1). At the outset, dirhodium(ii) tetracarboxylate Rh2(OPiv)4 was used, and the catalytic reaction occurred smoothly, delivering the desired alkylidenecyclobutane product 3aa in 73% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Then, gold and platinum salts, which are typically effective catalysts for the 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters, were investigated, but they were ineffective (Table 1, entries 2 and 3). Subsequent investigation revealed that lowering the temperature was disadvantageous to this reaction (Table 1, entry 4). The examination of other migration groups indicated that the acetoxyl group was the most effective migration group (Table 1, entries 5–8). The catalyst loading and the amount of p-methylstyrene 2a could be further reduced without loss of the yield albeit with a prolonged reaction time (Table 1, entries 10 and 11).

Optimization of the reaction conditionsa.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Cat. (mol%) | 2 (eq.) | Yieldb |

| 1 | –OCH3 (1a) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | 73% |

| 2 | –OCH3 (1a) | PtCl2 (5) | 5.0 | N.D. |

| 3 | –OCH3 (1a) | PPh3AuCl/AgOTf (5) | 5.0 | N.D. |

| 4c | –OCH3 (1a) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | Trace |

| 5 | –OBn (1b) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | 82% |

| 6 | –tBu (1c) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | 80% |

| 7 | –Ph (1d) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | 74% |

| 8 | –CH3 (1e) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (5) | 5.0 | 94% |

| 9 | –CH3 (1e) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (1) | 5.0 | 84% |

| 10d | –CH3 (1e) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (1) | 5.0 | 97% |

| 11d | –CH3 (1e) | Rh2(OPiv)4 (1) | 2.0 | 95%(82%)e |

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 2a and the catalyst in 2 mL of DCE at 80 °C for 24 h.

NMR yield.

60 °C.

48 h.

Isolated yield. DCE: 1,2-dichloroethane.

Substrate scope evaluation

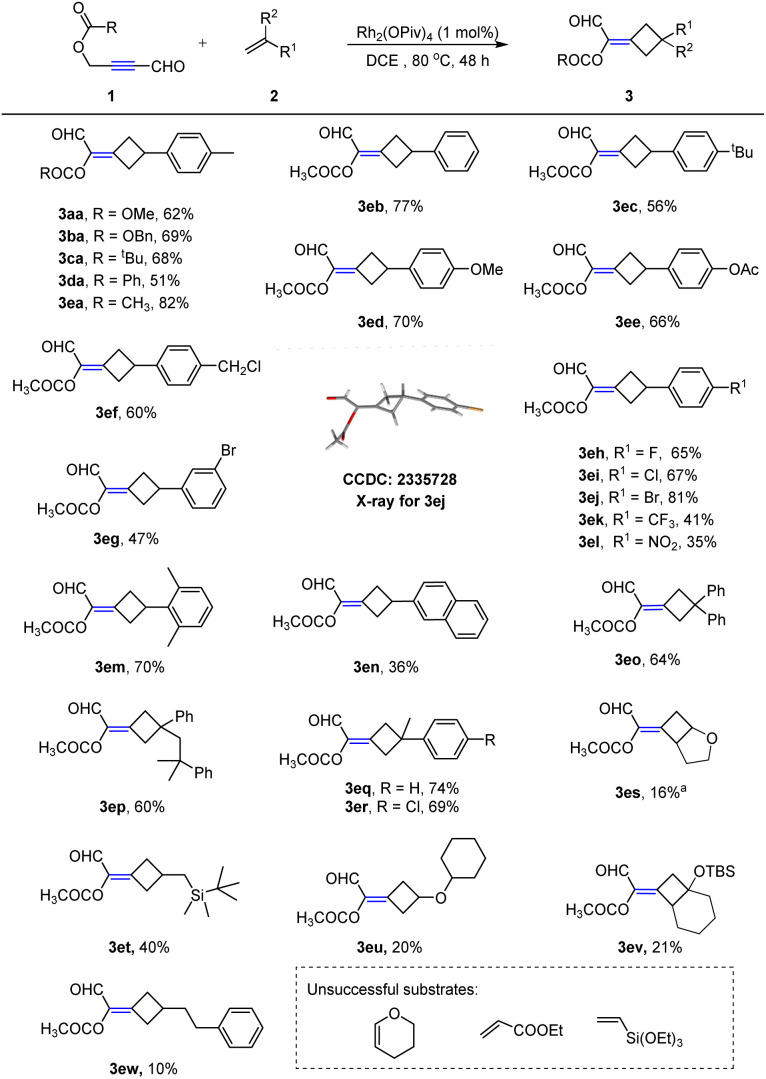

With the optimized reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 11) in hand, we proceeded to evaluate the scope of alkenes. As shown in Scheme 2, the catalytic process could be successfully applied to various alkenes with diverse functional groups. Styrene derivatives with both electron-donating (2a–f) and -withdrawing (2g–j) groups on the phenyl ring could be effectively converted into the desired alkylidenecyclobutane 3ea–ej in good yields. The structure of 3ej was unambiguously confirmed by an X-ray crystallographic analysis. Styrenes with strong withdrawing substituents on the phenyl group also worked well with slightly decreased yields (3ek–el). Notably, the reaction was not sensitive to the steric factor as the 2,6-dimethyl-substituted substrate was also successfully converted to corresponding product 3em in 70% yield. 2-vinylnaphthalene was compatible with this reaction as well, leading to the desired product 3en in 36% yield. In addition to monosubstituted alkenes, 1,1-disubstituted alkenes such as 1,1-diphenylethene and α-alkylethylenebenzenes were also amenable to the reaction, affording corresponding products 3eo–er in 60–74% yields. Other oxyheterocyclic alkenes such as dihydrofuran were also tolerated and the corresponding product 3es was obtained in 16% NMR yield. Notably, allylsilane (3et), vinyl ether (3eu), silyl enol ether (3ev), and simple aliphatic alkene (3ew) were suitable for our system. The regiochemistry of compound 3ev was confirmed on the basis of the NMR bidimensional studies (see the ESI† for details). However, dihydropyran, ethyl acrylate and vinyl siloxane were proved ineffective.

Scheme 2. Substrate scope of propargylic esters and alkenes. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.4 mmol), Rh2(OPiv)4 (1 mol%), 1,2-dichloroethane (2 mL), 80 °C, 48 h. a NMR yield with 4-nitrotoluene as the internal standard. Note: 3es was unstable during purification with silica gel.

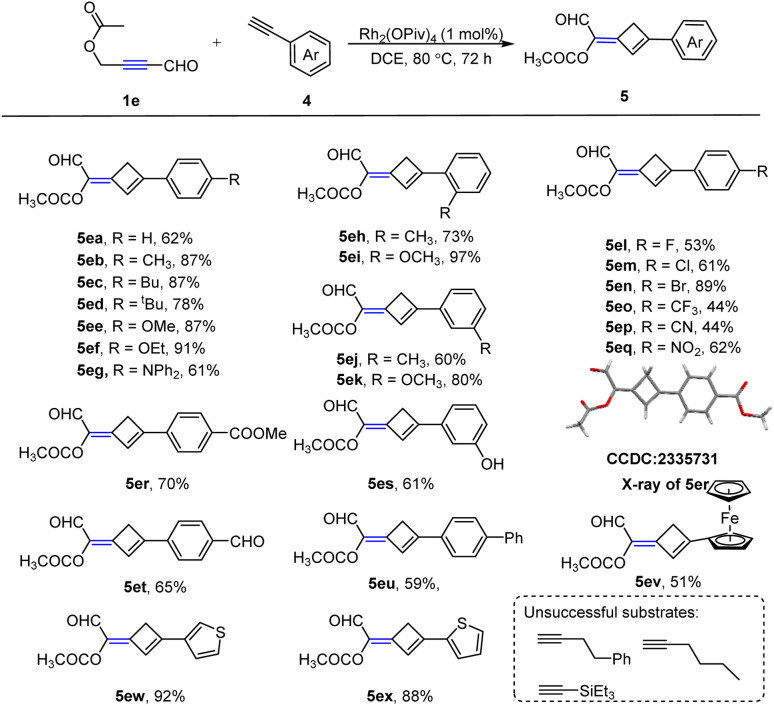

Taking into account the importance of alkylidenecyclobutene, we wondered whether alkyne could be used as the second component in our system. Under the standard conditions, we were delighted to observe the formation of the target product in 55% yield (Table S2,† entry 1). Encouraged by this result, further optimization of the reaction conditions was carried out (more details in ESI, Table S2†). Under the optimized conditions, the substrate scope of the Rh2(ii)-based catalytic system was then investigated (Scheme 3). It was found that the reaction proceeded smoothly with various substituted phenylacetylenes 4, and the corresponding 1,3-dienes 5 were formed in moderate to excellent yields. Phenylacetylenes substituted with electron-donating groups were first examined; these reactions could successfully furnish the desired products 5ea–eg in 61–91% yields. Phenylacetylenes substituted with electron-deficient groups were also applicable with slightly decreased yields (5el–eq, 44–89%) compared to the electron-rich ones. The position of the substituents on the aryl group has a slight effect on yields (5eh–ek). In addition, the diverse functional groups, such as –COOCH3, –OH and –CHO were compatible with our system, leading to the desired products in 61–70% yields (5er–et). The structure of 5er was unambiguously confirmed by an X-ray crystallographic analysis. Besides, biphenyl and ferrocenyl substituted alkynes also performed well (5eu–ev). Furthermore, thiophene-containing substrates could also participate in this reaction well with excellent yields (5ew and 5ex). Aliphatic alkynes and triethyl-(ethynyl)silane were unable to give the desired products.

Scheme 3. Substrate scope of propargylic esters and alkynes. Reaction conditions: 1e (1.0 mmol), 4 (0.2 mmol), Rh2(OPiv)4 (1 mol%), 1,2-dichloroethane (3 mL), 80 °C, 72 h.

Synthetic application

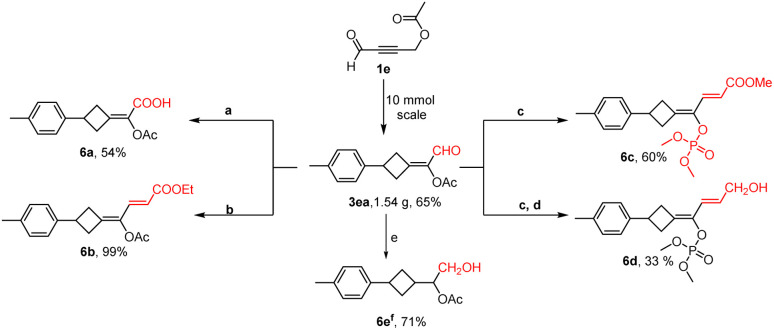

To showcase the robustness of this method, the gram-scale preparation of the alkylidenecyclobutane was then carried out. As shown in Scheme 4, 3ea could be robustly prepared on a 10 mmol-scale in good yield. With functionalized alkylidenecyclobutane 3ea in hand, several further transformations were also performed. For example, carboxylic acid 6a could be produced through the conventional Pinnick oxidation. The Wittig reaction of 3ea gave direct access to conjugated diene ester 6b in quantitative yield. Interestingly, under Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction conditions, the carbon–carbon double bond and phosphate in 6c were formed at the same time. Subsequently, the ester in 6c could be further reduced to a hydroxyl group. In addition, 3ea could be reduced to 6e in 71% yield in the presence of NaBH4.

Scheme 4. Gram-scale reaction and synthetic applications. (a) NaOClO (3.0 eq.), NaH2PO4 (4.0 eq.), 2-methyl-2-butene/tBuOH/H2O (3/3/1). (b) Ph3PCHCOOEt (1.2 eq.), DCM. (c) NaH (1.2 eq.), (MeO)2POCHCOOEt (1.2 eq.), THF. (d) DIBAL-H (1.1 eq.), toluene, −78 °C. (e) NaBH4 (3.0 eq.), CH3OH. (f) Four isomers were observed in the NMR spectra.

Mechanistic investigation

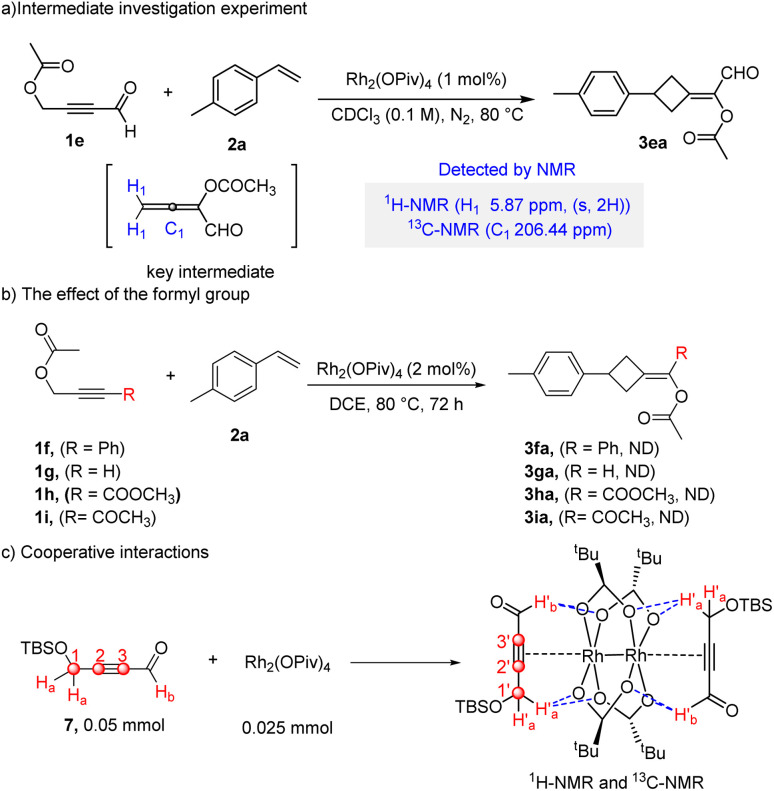

To better understand this reaction, a real-time 1H-NMR study was first conducted (Scheme 5a). As shown in Fig. S1,† with the increase in reaction time, a signal peak (5.87 ppm) increased in the early stage, then decreased and finally disappeared completely. We speculated that this peak might be the characteristic peak of the intermediate. Besides, the unique carbon signal (206.44 ppm) was detected by the 13C-NMR analysis (Fig. S2†). Furthermore, the reaction was performed at room temperature in the absence of alkene 2a for obtaining the key intermediate. The result showed that in addition to the signal peak at 5.87 ppm, other new signal peaks were detected by 1H-NMR analysis at 9.33 ppm and 2.23 ppm (Fig. S3†). It should be noted that such an intermediate was too unstable to be isolated. Based on the reported literature studies,18 we inferred that the NMR signal peaks could be assigned to the allene which serves as the key intermediate.

Scheme 5. Intermediate investigation and cooperative interaction. (a) Intermediate investigation experiment. (b) The effect of the formyl group. (c) Cooperative interactions.

The mechanistic details associated with the [2 + 2] cycloaddition constitute a topic of much study.19 The allene-involved [2 + 2] cycloaddition could be a metal-catalyzed or thermally-induced process in this reaction, but the process was completely different. As we all know, the metal-catalyzed process involves a reaction through head to head addition,4h while the thermal cycloaddition prefers to obtain head-to-tail isomers for steric reasons.19c,20 In this protocol, head-to-tail isomers were obtained, indicating that the thermally induced [2 + 2] cycloaddition was much more possible,21 which is supported by the fact that the reaction occurred only at elevated temperature.

To figure out the effect of the formyl group, a series of control experiments were carried out (Scheme 5b). While different propargylic esters substituted with –Ph (1f), –H (1g), –COOMe (1h) and –COCH3 (1i) were used as substrates, the desired products were not detected. This implies the crucial role of the formyl group. The above results are consistent with our previous experimental results,14a,b and we speculated that cooperative interactions between the substrate and the carboxylate ligand may be present (Scheme 5c). To get more convincing evidence, the NMR data of a mixture of substrate 7 and catalyst Rh2(OPiv)4 was acquired (for details, see Table S3 and Fig. S4†). There are slight downfield shifts for H′a and C1′ of the mixture in the 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra, which is possibly attributed to the formation of hydrogen bonding.22 In addition, the 13C signals of the alkyne (C2′ and C3′) in the mixture were shifted to a lower chemical shift because of the back-donation of rhodium.23 Simultaneously, the 1H signal of the formyl group (H′b) in the mixture was shifted to a lower chemical shift, and the 13C signal of the formyl group in the mixture was shifted downfield, which was in agreement with our previous results.16 Such results indicated that cooperative interactions between the substrate and the carboxylate ligand may exist and play a significant role in this reaction.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed an unprecedented tandem Rh2(ii)-catalyzed 1,3-acyloxy migration/intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient formyl-substituted propargylic esters with alkenes and alkynes. In this reaction, simple and readily available propargylic esters and alkenes/alkynes were used as starting materials to afford a broad spectrum of highly functionalized alkylidenecyclobutane/ene scaffolds in good yields. This protocol represents the first example of 1,3-acyloxy migration of electron-deficient propargylic esters, which previously preferred to undergo 1,2-acyloxy migration. Control experiments and NMR data revealed that the cooperative interactions between the substrate and the dirhodium catalyst might play a significant role in this reaction. This 1,3-acyloxy migration of propargylic esters catalyzed by dirhodium constitutes a new application of dirhodium complexes, which is a significant advance for both the allene chemistry and the dirhodium catalysis. We believe that the present study could shed light on the chemistry of dirhodium catalysis and inspire further new reactions for organic chemists.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the ESI† of this article.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Z. X. Methodology: Z. X. Investigation: Z. X. Writing (original draft): Z. X. Writing (review and editing): Z. X., D. Z., R. W. and S. Z. Funding acquisition: S. Z., R. W. and D. Z. Resources: S. Z. Supervision: R. W. and S. Z.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22071062, 22271096, 22201079, and 22201078), Natural Science Foundation of Guangzhou City (2023A04J1352), and Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024B1515040027).

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental details and characterization of all compounds, and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra. CCDC 2335728 (3ej) and 2335731 (5er). For ESI and crystallographic data in CIF or other electronic format see DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d4sc06458e

References

- (a) Bray C. D. Pattenden G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:3937–3939. [Google Scholar]; (b) Eisold M. Baumann A. N. Kiefl G. M. Emmerling S. T. Didier D. Chemistry. 2017;23:1634–1644. doi: 10.1002/chem.201604585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hansen T. V. Skattebøl L. Stenstrøm Y. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:3461–3466. [Google Scholar]; (d) Burgess M. L. Barrow K. D. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1999:2461–2466. [Google Scholar]; (e) Marrero J. Rodriguez A. D. Baran P. Raptis R. G. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2551–2554. doi: 10.1021/ol034833g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Siengalewicz P. Mulzer J. Rinner U. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2011;2011:7041–7055. [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhang A. Nie J. Khrimian A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:9401–9403. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Crepin D. Dawick J. Aissa C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:620–623. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liang Y. Jiao L. Wang Y. Chen Y. Ma L. Xu J. Zhang S. Yu Z. X. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5877–5879. doi: 10.1021/ol062504t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shen Y. M. Wang B. Shi Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:1429–1432. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Hulot C. Amiri S. Blond G. Schreiner P. R. Suffert J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13387–13398. doi: 10.1021/ja903914r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hulot C. Blond G. Suffert J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5046–5047. doi: 10.1021/ja800691c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Ding W. Yoshikai N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019;58:2500–2504. doi: 10.1002/anie.201813283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Francos J. Grande-Carmona F. Faustino H. Iglesias-Siguenza J. Diez E. Alonso I. Fernandez R. Lassaletta J. M. Lopez F. Mascarenas J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14322–14325. doi: 10.1021/ja3065446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) González A. Z. Benitez D. Tkatchouk E. Goddard III W. A. Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5500–5507. doi: 10.1021/ja200084a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jia M. Monari M. Yang Q.-Q. Bandini M. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:2320–2323. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08736d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ni Q. Song X. Png C. W. Zhang Y. Zhao Y. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:12329–12335. doi: 10.1039/d0sc02972f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Noucti N. N. Alexanian E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:5447–5450. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Saito N. Tanaka Y. Sato Y. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4124–4126. doi: 10.1021/ol901616b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Suarez-Pantiga S. Hernandez-Diaz C. Rubio E. Gonzalez J. M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:11552–11555. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Conner M. L. Xu Y. Brown M. K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3482–3485. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Snider B. B. Ron E. J. Org. Chem. 2002;51:3643–3652. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhong X. Tang Q. Zhou P. Zhong Z. Dong S. Liu X. Feng X. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:10511–10514. doi: 10.1039/c8cc06416d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Horino Y. Kimura M. Tanaka S. Okajima T. Tamaru Y. Chemistry. 2003;9:2419–2438. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kimura M. Horino Y. Wakamiya Y. Okajima T. Tamaru Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10869–10870. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ohno H. Mizutani T. Kadoh Y. Miyamura K. Tanaka T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:5113–5115. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Marco-Contelles J. Soriano E. Chem.–Eur. J. 2007;13:1350–1357. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Marion N. Nolan S. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:2750–2752. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Shu X.-Z. Shu D. Schienebeck C. M. Tang W. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:7698–7711. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35235d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hashmi A. S. K. Yang W. Yu Y. Hansmann M. M. Rudolph M. Rominger F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;52:1329–1332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Li X. Zhang M. Shu D. Robichaux P. J. Huang S. Tang W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:10421–10424. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shu X.-Z. Li X. Shu D. Huang S. Schienebeck C. M. Zhou X. Robichaux P. J. Tang W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:5211–5221. doi: 10.1021/ja2109097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Zhang G. Zhang L. Synlett. 2010;2010:692–706. [Google Scholar]

- Saucy G. Marbet R. Lindlar H. Isler O. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2004;42:1945–1955. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:16804–16805. doi: 10.1021/ja056419c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Niemeyer Z. L. Pindi S. Khrakovsky D. A. Kuzniewski C. N. Hong C. M. Joyce L. A. Sigman M. S. Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:12943–12946. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao W. Susanti D. Chan P. W. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15248–15251. doi: 10.1021/ja2052304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.-X. Zhu L.-L. Zhou W. Chen Z. Org. Lett. 2012;14:436–439. doi: 10.1021/ol202703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M. Li G. Wang S. Zhang L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:871–875. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wu R. Chen K. Ma J. Yu Z.-X. Zhu S. Sci. China: Chem. 2020;63:1230–1239. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu R. Chen Y. Zhu S. ACS Catal. 2022;13:132–140. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu R. Zhu D. Zhu S. Org. Chem. Front. 2023;10:2849–2878. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhu D. Cao T. Chen K. Zhu S. Chem. Sci. 2022;13:1992–2000. doi: 10.1039/d1sc05374d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu D. Chen L. Fan H. Yao Q. Zhu S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020;49:908–950. doi: 10.1039/c9cs00542k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R. Lu J. Cao T. Ma J. Chen K. Zhu S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:14916–14925. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c07556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu S. Gao X. Zhu S. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:13730–13736. doi: 10.1039/d1sc04961e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari D. P. Pisella G. Wodrich M. D. Tsymbal A. V. Tirani F. F. Scopelliti R. Waser J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021;60:5475–5481. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Pasto D. J. Warren S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:3670–3676. [Google Scholar]; (b) Faustino H. Bernal P. Castedo L. López F. Mascareñas J. L. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:1658–1664. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kimura M. Horino Y. Wakamiya Y. Okajima T. Tamaru Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:10869–10870. [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y. S. Eur. J. Org Chem. 2024;27:e202400041. [Google Scholar]

- Brandi A. Cicchi S. Cordero F. M. Goti A. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:7317–7420. doi: 10.1021/cr400686j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I. and Williams D. H., Spectroscopic Methods in Organic Chemistry, Springer Link, Heidelberg, Berlin, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Sun J. Kozmin S. A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2006;348:2271–2296. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the ESI† of this article.