Abstract

Nucleolar protein 3 (NOL3), as a markedly increased protein across a range of tumors, has been well acknowledged that plays an anti-apoptotic role in malignancies, while some novel impacts of NOL3 on metastasis and chemoresistance are demonstrated recently. In this study, we uncover another role of NOL3 on promoting proliferation in bladder cancer (BLCA). The reduction of NOL3 significantly inhibited cell proliferation, and we detected the stable cell cycle arrest after knockdown of NOL3 in two-type BLCA cell lines. Mechanistically, we present the first evidence that the PI3K/Akt pathway was considerably inhibited with the decrease of NOL3 in BLCA cell lines. In addition, LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor, rescued NOL3 overexpression-mediated activation of the PI3K/Akt axis and the depression of proliferation in BLCA cell lines. In conclusion, our study suggests that NOL3 is upregulated in BLCA cells and promotes proliferation via the PI3K/Akt pathway, indicating that NOL3 may be a potential therapeutic target for BLCA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12957-024-03600-5.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, NOL3, Cell proliferation

Introduction

Bladder cancer (BLCA) is a common malignant tumor of the urinary system, ranks as the sixth most common cancer among men and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths. In recent years, both its incidence and mortality rates have shown an increasing trend [1, 2]. BLCA can be classified into non-muscle-invasive BLCA (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive BLCA (MIBC), with approximately 75% of patients diagnosed with NMIBC. However, MIBC, although less prevalent, poses a greater malignant potential and a higher threat to patient survival. Even with progress in surgical techniques and pharmacological treatments, a considerable number of individuals with BLCA continue to fall victim to the illness [3]. Exploring effective therapeutic targets for BLCA can mitigate the mortality risk associated with this condition.

Nucleolar protein 3 (NOL3) is located on human chromosome 16 and encodes a unique protein known as apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain [4]. This protein was first discovered by screening for Caspase-9’s caspase recruitment domain homologous protein [4] and protects cells from apoptosis induced by multiple stimuli such as hypoxia [5], hydrogen peroxide [6], and Fas ligands [7].However, role of NOL3 in cell proliferation remain poorly understood. For instance, in pulmonary arterial hypertension, NOL3 enhances growth factor-induced cell proliferation [8]. Furthermore, NOL3 facilitates the transition of vascular smooth muscle cells from a contractile phenotype to a proliferative variant, consequently accelerating cellular proliferation [9].

Malignant proliferation is a major characteristic of tumor, and the proliferation of tumor cells is affected by many biological regulatory mechanisms such as heredity [10], metabolism [11] and signaling pathways [12]. The mechanism by which NOL3 regulates the proliferation of malignant tumors is still unclear. Existing studies have shown that the absence of NOL3 promotes the proliferation of stem cells and progenitors by activating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in myeloproliferative tumors [13]. However, there are still no studies on the regulatory mechanism of NOL3 on the proliferation of other tumors such as bladder cancer.

In this study, we investigated the role of NOL3 in bladder cancer, and we found that NOL3 promotes proliferation of BLCA cells through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt) pathway. This research may provide new insights and targets for the treatment of BLCA.

Method

Cell lines and culture

The human BLCA cell lines (T24, UC3) were purchased from the Shanghai Zhonghua Cell Bank. T24 and UC3 cell strains were cultured in DMEM supplied by Procella from Wuhan, China, augmented with an extra 10% of fetal bovine serum (sourced from Procella as well).All cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Bladder cancer (BLCA) patients and clinical specimens

A total of 12 pairs of bladder cancer (BLCA) tissues diagnosed as primary bladder cancer, along with adjacent non-cancerous tissues, were collected for experimentation. This study received necessary ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University and obtained written consent from the patients. After collection, tissue specimens were fixed in formaldehyde and stored at -80 °C until further use for paraffin embedding, RNA, or protein extraction.

RT-qPCR assay

The primers used in the study were designed and synthesized by Tsingke (Beijing, China). The sequences are provided in Table 1. Human ACTB was used as the reference gene. The expression level of NOL3 mRNA was quantified relative to human ACTB using the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) method (2-ΔΔCt method).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for RT–qPCR

| Gene Name | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NOL3 | 5′-GACCGCAGCTATGACCCTC-3′ | 5′-TCGTCAGGGTCTGAAGCTCT-3′ |

| ACTB | 5′-CCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGTC-3′ | 5′-TGATCTCATTGTGCTGGGTG-3′ |

Plasmid and lentiviral transfection

The plasmids used in the study (shNC, shNOL3, OE-NC, OE-NOL3, PAX2, VSVG) were all purchased from Tsingke (Beijing, China). When 293T cells reached approximately 50% confluence in a 10 cm culture dish, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, plasmids were transfected into the 293T cells using Lipofectamine 8000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). After transfection for 8 h at 37 °C, the supernatant was replaced with DMEM medium. Supernatants were collected 48 h later, followed by an additional collection after another 24 h with the same volume of DMEM medium replenished. The collected supernatants were mixed and passed through a cell strainer to remove cells, retaining the supernatant. The obtained supernatant was used for transfection of T24 and UC3 cells.

Cell proliferation assay

The proliferation rate of cells was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (BeyoClick™, Nantong, China, EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 488). In the CCK-8 assay, cells (2 × 10^3 cells/well or 1 × 10^3 cells/well) were evenly seeded into 96-well plates. At 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h, CCK-8 reagent was added and incubated in the dark for 1 h. The absorbance at 450 nanometers was measured using a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) to determine the cell number in each well. For the EdU assay, cells (5 × 10^3 cells/well) were evenly seeded into 96-well plates. After incubation for 24–48 h, cells were subjected to EdU incubation, fixation, and fluorescence staining, followed by observation of fluorescence intensity under a fluorescence microscope.

Flow cytometry

Cell cycle analysis was conducted by the School of Life Sciences, Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China), using flow cytometry. Cells in logarithmic growth phase were collected, fully digested with trypsin, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, supernatant was discarded, and cells were fixed with 75% alcohol overnight. The next day, the cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min, supernatant was discarded, and cells were washed with 3 ml PBS. Then, 400 µl of propidium iodide (PI, 50 µg/ml) and 100 µl of RNase A (100 µg/ml) were added to the cells, followed by incubation in the dark at 4 °C for 30 min. Cell cycle analysis was performed using standard procedures on a flow cytometer. The results are presented as the mean of three independent experiments.

Western blot

Total protein from cells was extracted using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Meilunbio, Dalian, China). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, including anti-NOL3 (Proteintech, Rosemont, Illinois, USA, Cat No: 10846-2-AP), anti-PI3K (Abmart, Cat No. T40064S), anti-p-PI3k (Tyr467/199) pAb (Abmart, Cat No. T40065S), anti-AKT (Proteintech, Cat No. 80455-1-RR), and anti-p-Akt (Abmart, Cat No. T40067S).

Mouse xenograft assays

The experiments were conducted using BALB/c nude mice. T24 cells transfected with OE-NC or OE-NOL3 lentivirus were resuspended in saline, and 2 × 10^6 cells were implanted into the shoulder of nude mice. Tumor size was measured using calipers 7 days post-injection, and the longest and shortest diameters were recorded. Subsequent measurements were taken every 3 days, and tumor volume was calculated using the formula: (L×W^2)×0.5, where L represents the longest diameter and W represents the shortest diameter. At the end of the study, mice were euthanized, and tumors were dissected and weighed [10]. The related experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Chongqing Medical University (IACUC-CQMU-2023-0226).

Bioinformatics analysis

The data for bioinformatics analysis were collected from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga, accessed on March 2, 2024). Annotation was performed using R language (pROC and survivanROC packages) [14].

Statistical analysis

All experiments were independently repeated at least three times. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.0 software and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between two groups were compared using the t-test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for pairwise comparisons among multiple groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

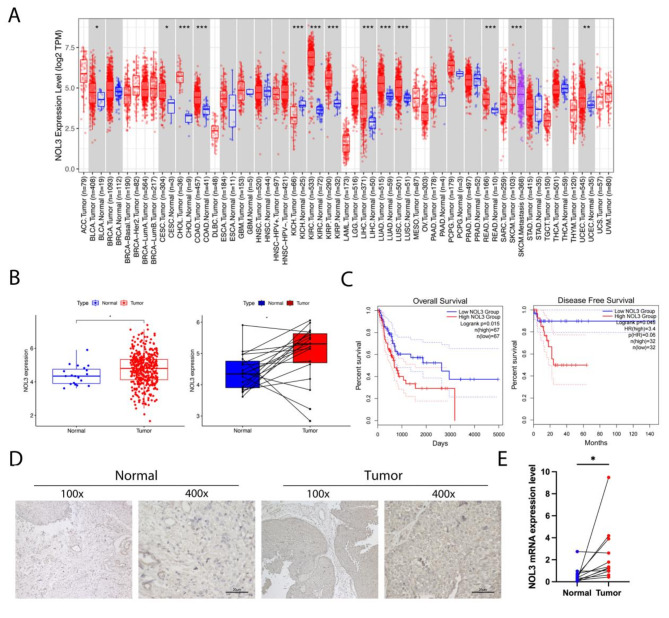

NOL3 is overexpressed in BLCA and closely associated with clinical prognoses

To delve into the mechanistic role of NOL3 in cancers, we conducted extensive analyses utilizing The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) pan-cancer database. The results revealed significant upregulation of NOL3 across various cancers including BLCA, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, colorectal cancer, and renal clear cell carcinoma (Fig. 1A). To validate the expression pattern of NOL3 in BLCA, we further analyzed 412 tumor samples and 19 paired cancerous and adjacent non-cancerous tissues in the TCGA database, and found that NOL3 is highly expressed in BLCA tissues (Fig. 1B). Subsequent analysis indicated that BLCA patients with high NOL3 expression exhibited significantly reduced overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) (Fig. 1C). We collected six clinical specimens of cancerous tissue and adjacent non-cancerous tissue from patients with BLCA to investigate the expression characteristics of NOL3.Immunohistochemistry experiments revealed a significant overexpression of NOL3 in BLCA (Fig. 1D). Meanwhile, mRNA was extracted from 12 pairs of clinical specimens for analysis, showing a significant upregulation of NOL3 in BLCA (p = 0.0249) (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

NOL3 is overexpression in BLCA and associated with poor prognosis. (A) Expression analysis of NOL3 in the TCGA pan-cancer database. (B) Validation of NOL3 expression in the TCGA database. (C) Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) analysis in the TCGA database. (E) Immunohistochemical analysis of NOL3 using collected BLCA cancerous and adjacent tissues. (F) Validation of NOL3 mRNA using collected cancerous and adjacent tissues from 12 pairs of BLCA patients.* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

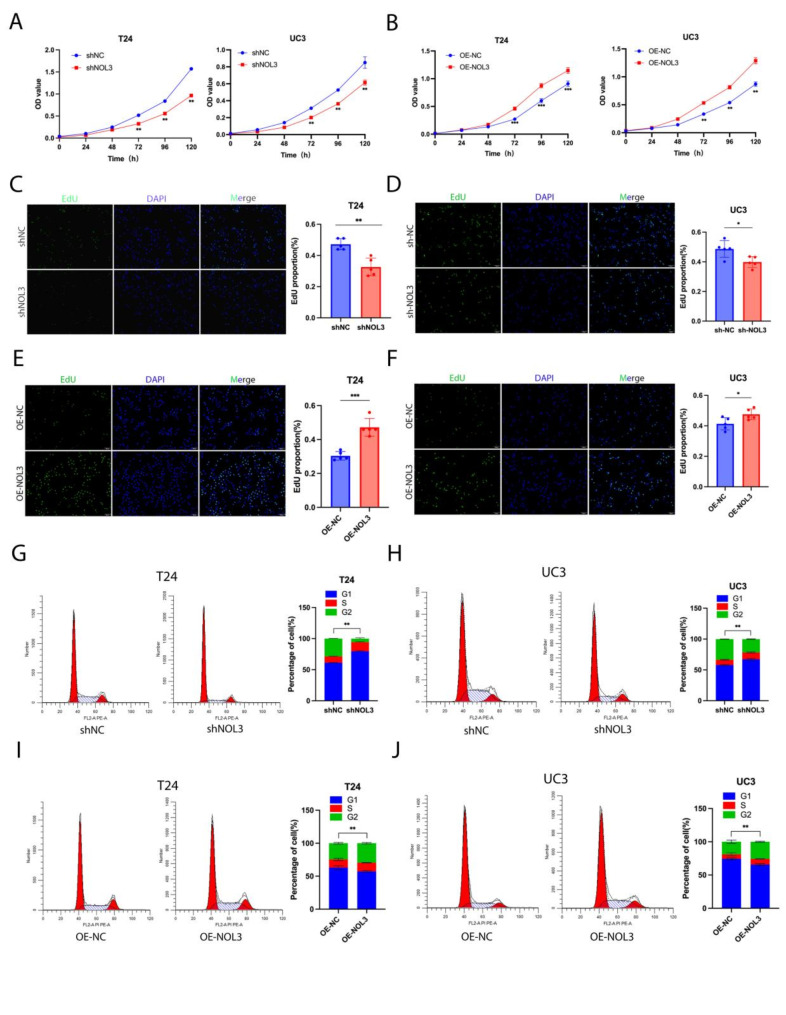

NOL3 facilitates proliferation of BLCA cells

In subsequent experiments, NOL3 was stably knocked down and overexpressed in two-type cell lines, evidenced by the mRNA and protein levels (Figure. S1 A-D). As illustrated in a 6-day CCK8 proliferation assay, we observed a significant decrease in the proliferation rate of BLCA cells upon knockdown of NOL3 in both T24 and UC3 cell lines (Fig. 2A). This effect was particularly pronounced in the T24 cell line, which exhibited higher NOL3 level, whereas overexpression of NOL3 significantly increased the proliferation rate of BLCA cells (Fig. 2B). These findings were further confirmed by EdU experiments (Fig. 2C-F). To elucidate the specific mechanism by which NOL3 affects BLCA cell proliferation, cell cycle analysis was performed on stable transfectants of the two cell lines. We found that knockdown of NOL3 led to cell cycle arrest, with cells accumulating in the G1 phase (Fig. 2G, H), while overexpression of NOL3 activated the cell cycle, resulting in a significant reduction in the proportion of cells in the G1 phase (Fig. 2I, J). Overall, NOL3 regulates BLCA cell proliferation by modulating the cell cycle.

Fig. 2.

NOL3 regulates proliferation and cell cycle of BLCA cells. (A, B) CCK-8 proliferation analysis was performed to validate the effect of NOL3 on the proliferation ability of T24 and UC3 cell lines. (C, D, E, F) EdU analysis was conducted to validate the effect of NOL3 on the proliferation ability of T24 and UC3 cell lines. (G, H) Flow cytometry was performed to validate the effect of NOL3 knockdown on the cell cycle of T24 and UC3 cells. (I, J) Flow cytometry was conducted to validate the effect of NOL3 overexpression on the cell cycle of T24 and UC3 cells.* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

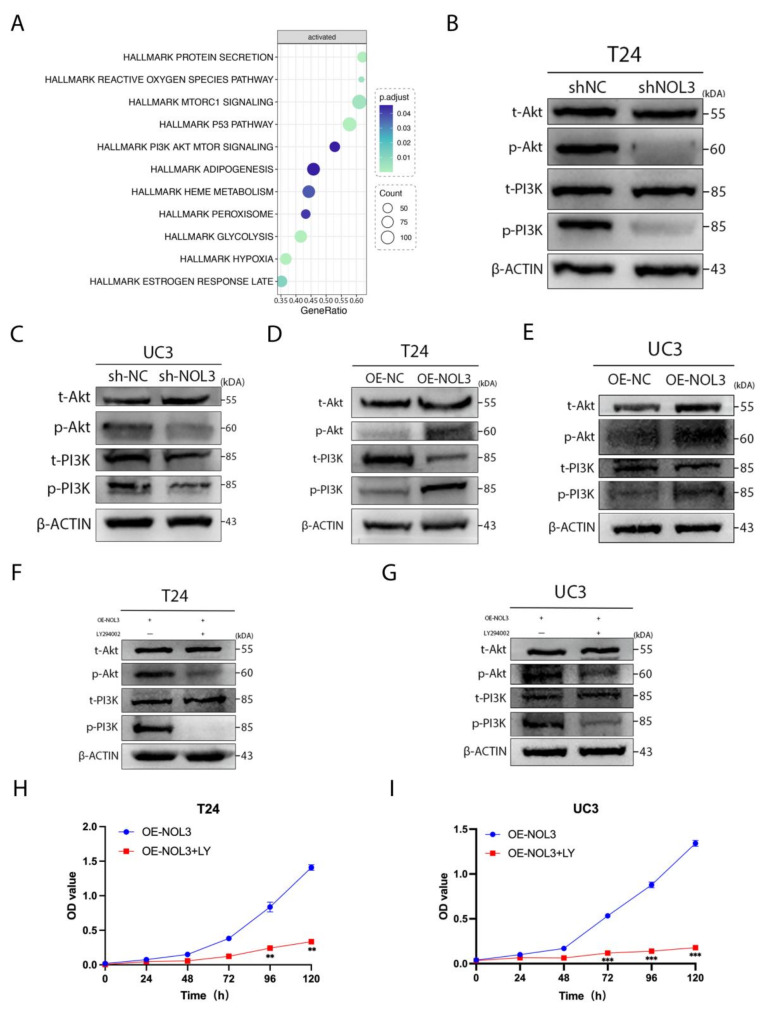

NOL3 promotes proliferation of BLCA cells through the PI3K/Akt pathway

We conducted single-gene KEGG enrichment analysis of NOL3 and successfully identified enrichment of the PI3K/Akt pathway (Fig. 3A). Upon knockdown of NOL3, a significant decrease in the phosphorylation levels of PI3K and Akt was observed (Fig. 3B, C), whereas overexpression of NOL3 took the opposite effects (Fig. 3D, E). Furthermore, LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor, rescued NOL3 overexpression-mediated facilitating roles in PI3K and Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 3F, G), thereby suppressing proliferation in BLCA cells (Fig. 3H, I). Therefore, we speculate that NOL3 promotes BLCA cell proliferation by enhancing phosphorylation of the PI3K/Akt pathway.

Fig. 3.

NOL3 promotes proliferation of BLCA cells through the PI3K/Akt pathway. (A) Single-gene KEGG enrichment analysis of NOL3. (B, C) Effects of NOL3 knockdown on the PI3K/Akt pathway. (D, E) Effects of NOL3 overexpression on the PI3K/Akt pathway. (F, G) Effects of PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) on the PI3K/Akt pathway after NOL3 overexpression. (H, I) CCK-8 proliferation analysis was conducted to evaluate the effect of PI3K inhibitor (LY294002) on the proliferation ability of BLCA cells after NOL3 overexpression.* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Overexpression of NOL3 significantly promotes BLCA proliferation in CDX models. Cell line-derived xenograft

Subsequently, to investigate the effect of NOL3 on in vivo tumor growth, we conducted in vivo experiments using nu/nu mice. T24 cells stably transfected with either NOL3 overexpression (OE-NOL3) or control vector (OE-NC) were subcutaneously injected into nude mice for tumorigenesis. Results revealed that tumors in the NOL3 overexpression promoted tumor growth in speed and in size compared to the control group (Fig. 4A, B). Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor tissues confirmed elevated levels of NOL3 expression in OE-NOL3-derived tumors were consistence with the highly proliferative activities, evidenced by the increasing Ki-67 expression (Fig,4 C). We also extracted proteins from tumor tissue, and we found significant increases in phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt in OE-NOL3-derived tumors (Fig. 4D). Overall, hyperexpression of NOL3 prominently enhances the proliferation of BLCA tumors.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of NOL3 promotes proliferation of BLCA in vivo. (A) Tumor size after 28 days of subcutaneous tumor growth in nude mice. (B) Tumor growth curve of subcutaneous tumors in nude mice. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of NOL3 and Ki67 in subcutaneous tumors of nude mice. (D) Expression of PI3K/Akt pathway in tumor proteins ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Discussion

In the present study, we found that NOL3 was significantly elevated in BLCA and was strongly associated with active cycles and poor prognosis. Knockdown of NOL3 inhibited BLCA cell proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest, while overexpression of NOL3 had the opposite effect. Mechanistically, these findings indicated that NOL3 knockdown resulted in significant inhibition of PI3K and Akt phosphorylation, while overexpression of NOL3 promoted their phosphorylation. Inhibition of PI3K by LY294006 in NOL3-overexpressed BLCA cells markedly suppresses the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt, thereby reversing the proliferative effects.

NOL3 is widely distributed in tissues such as the heart, skeletal muscles, pancreatic β cells, vascular smooth muscles, and brain [15]. NOL3 has been studied in a variety of diseases. The expression of NOL3 in skeletal muscle not only inhibits muscle cell apoptosis but also suppresses myoblast differentiation, thereby ameliorating muscular degenerative diseases associated with chronic conditions such as infection and cancer [16].In islet β cells, the high expression of NOL3 can improve the islet amyloid-induced β cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes patients by inhibiting the JNK pathway [17]. The decreased expression of NOL3 also promoted the apoptosis of tubular epithelial cells after renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and increased the vulnerability of kidney to ischemia-reperfusion injury [18]. In malignant tumors, NOL3 also plays an important role. In acute myeloid leukemia, the ARC-regulated IL1β/Cox-2/PGE2/β-Catenin/ARC signaling axis enhances tumor microenvironment-mediated chemotherapy resistance [19]. Elevated levels of NOL3 in colorectal cancer have been observed and are significantly associated with patient prognoses [20]. However, the role of NOL3 in bladder cancer is still unknown. Our study shows for the first time that NOL3 is overexpressed in bladder cancer and directly affects the prognosis of patients with bladder cancer, which provides new ideas for the treatment of bladder cancer.

NOL3 plays a vital part in preserving cellular equilibrium by simultaneously impeding the extrinsic apoptosis route via its CARD domain’s interaction with death receptors and upholding mitochondrial integrity to hinder the intrinsic apoptosis route [21]. Research has shown that NOL3 naturally present in regular heart muscle cells can prevent cell death triggered by the cycle of low oxygen and subsequent reoxygenation [22]. Moreover, in malignant tumors, NOL3 can regulate the malignant progression of tumors through a variety of mechanisms. NOL3 has been found to be correlated with several cancer-related genes such as p53 and Bcl-2 [23]. Similarly, higher NOL3 levels are seen in clear cell renal cell carcinoma, where the NOL3 protein intervenes to inhibit cellular demise by hindering the TRAIL-induced extrinsic pathway of apoptosis and the activity of caspase-8 [24, 25]. NOL3 and its translation product regulate the physiological behavior of normal cells as well as malignant tumor progression. However, the role of NOL3 in the proliferation of malignant tumors remains unknown. Although previous studies have shown that NOL3 inhibits tumor cell proliferation in myeloproliferative neoplasms [13], this study is the first to show that NOL3 promotes bladder cancer cell proliferation, which may be relevant to the distinction between bladder cancer as a solid tumor and myeloproliferative neoplasms as a non-solid tumor. We also found for the first time that NOL3 regulates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway plays a crucial role in intracellular cascades and is frequently found to be overactivated in malignant tumors [26]. This pathway regulates various malignant biological behaviors such as cell proliferation [27], apoptosis [28], and angiogenesis [29]. Of particular note, numerous studies have indicated that the overactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway significantly promotes excessive proliferation of malignant tumor cells [30–32]. The phosphorylation levels of PI3K and Akt were significantly affected by NOL3. After the application of PI3K inhibitor in stably transfected cells overexpressing NOL3, the effect of NOL3 on BLCA cell proliferation was inhibited. Our study shows for the first time that NOL3 promotes the proliferation of bladder cancer cells by promoting the phosphorylation of PI3K and Akt.

Conclusion

this study suggests that hyperexpression of NOL3 facilitates the proliferation of BLCA cells through activating PI3K/Akt phosphorylation. This may provide deeper insights into the mechanisms underlying proliferation of tumors and reveals a novel target for treatment of BLCA.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

All authors express their sincere gratitude to the Experimental Research Center and the Department of Urology of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University for their assistance.

Author contributions

L.W. and W.H.: conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft; K.Z.,H.Y.: software, validation; H.T. and K.Z.: methodology, formal analysis; T.L., J.Z. and J.C.: visualization, investigation; Y.S., X.Z.: writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (protocol code 2021-085 and 3 March 2021 of approval) for studies involving humans. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Chongqing Medical University (IACUC-CQMU-2023-0226).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lenis A T, Lec P M, Chamie K. Bladder Cancer: a review [J]. Jama-Journal Am Med Association. 2020;324(19):1980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. Ca-a Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding X, Jin Y, Shi X, et al. TDO2 promotes bladder cancer progression via AhR-mediated SPARC/FILIP1L signaling [J]. Biochem Pharmacol. 2024;223:116172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koseki T, Inohara N, Chen S, et al. ARC, an inhibitor of apoptosis expressed in skeletal muscle and heart that interacts selectively with caspases [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(9):5156–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong YM, Jo D G, Lee JY, et al. Down-regulation of ARC contributes to vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to ischemia/hypoxia [J]. FEBS Lett. 2003;543(1–3):170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Z W Ekhterae D, Lundberg M S, et al. ARC inhibits cytochrome < i > c release from mitochondria and protects against hypoxia-induced apoptosis in heart-derived H9c2 cells [J]. Circul Res. 1999;85(12):E70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nam YJ, Mani K, Ashton A W, et al. Inhibition of both the extrinsic and intrinsic death pathways through nonhomotypic death-fold interactions [J]. Mol Cell. 2021;81(3):638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaiman AL, Damico R, Thoms-Chesley A, et al. A critical role for the protein apoptosis Repressor with Caspase Recruitment Domain in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary hypertension [J]. Circulation. 2011;124(23):2533–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu M X, Yu T, Li M Y, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain promotes cell proliferation and phenotypic modulation through 14-3-3ε/YAP signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells [J]. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;147:35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li T D, Huang M W, Sun N et al. Tumorigenesis of basal muscle invasive bladder cancer was mediated by PTEN protein degradation resulting from < i > SNHG1 upregulation [J]. J Experimental Clin Cancer Res, 2024, 43(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Xie B, Lin J T, Chen X W et al. CircXRN2 suppresses tumor progression driven by histone lactylation through activating the Hippo pathway in human bladder cancer [J]. Mol Cancer, 2023, 22(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Rezaei S, Nikpanjeh N, Rezaee A et al. PI3K/Akt signaling in urological cancers: tumorigenesis function, therapeutic potential, and therapy response regulation [J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2023, 955. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Stanley R F, Piszczatowski R T, Bartholdy B, et al. A myeloid tumor suppressor role for < i > NOL3 [J]. J Exp Med. 2017;214(3):753–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong H, Li T H, Gao S et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related long noncoding RNA signature correlates with the prognosis and progression in patients with bladder cancer [J]. Biosci Rep, 2021, 41(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Liu K, Lan D F, Li C Y et al. A double-edged sword: role of apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) in tumorigenesis and ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [J]. Apoptosis, 2023, 28(3–4): 313 – 25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hunter A L, Zhang J C, Chen S C, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) inhibits myogenic differentiation [J]. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(5):879–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Templin A T, Samarasekera T, Meier D T, et al. Apoptosis Repressor with Caspase Recruitment Domain ameliorates amyloid-Induced β-Cell apoptosis and JNK pathway activation [J]. Diabetes. 2017;66(10):2636–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ke YJ, Yan H H, Chen L W, et al. Apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain deficiency accelerates ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced acute kidney injury by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis: the role of AKT/mTOR signaling [J]. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy; 2019. p. 112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Carter B Z, Mak P Y, Wang X M, et al. An ARC-Regulated IL1β/Cox-2/PGE2/β-Catenin/ARC Circuit Controls Leukemia-Microenvironment Interactions and confers Drug Resistance in AML [J]. Cancer Res. 2019;79(6):1165–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He QL, Li Z Q Yin JB et al. Prognostic significance of autophagy-relevant gene markers in Colorectal Cancer [J]. Front Oncol, 2021, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Li Q, Yang J, Zhang J, et al. Inhibition of microRNA-327 ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced cardiomyocytes apoptosis through targeting apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain [J]. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(4):3753–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y Z, Ge X L, Liu X, H. The cardioprotective effect of postconditioning is mediated by ARC through inhibiting mitochondrial apoptotic pathway [J]. Apoptosis. 2009;14(2):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roser C, Tóth C, Renner M et al. Expression of apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) adenomas and its correlation with DNA mismatch repair proteins, p53, Bcl-2, COX-2 and beta-catenin [J]. Cell Communication Signal, 2021, 19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhang F Y, Yu S C, Wu P J, et al. Discovery and construction of prognostic model for clear cell renal cell carcinoma based on single-cell and bulk transcriptome analysis [J]. Translational Androl Urol. 2021;10(9):3540–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang J, Zheng X X, Wang P Y, et al. Role of apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) in cell death and cardiovascular disease [J]. Apoptosis. 2021;26(1–2):24–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su H, Peng C, Liu Y. Regulation of ferroptosis by PI3K/Akt signaling pathway: a promising therapeutic axis in cancer [J]. Front Cell Dev Biology, 2024, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Zhou K L, Wu C L, Cheng W J, et al. Transglutaminase 3 regulates cutaneous squamous carcinoma differentiation and inhibits progression via PI3K-AKT signaling pathway-mediated keratin 14 degradation [J]. Volume 15. Cell Death & Disease; 2024. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Li JK, Jiang X L, Zhang Z, et al. Isoalantolactone exerts anti-melanoma effects via inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT3 signaling in cell and mouse models [J]. Phytotherapy Research; 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Liu H, Zhang J H, Zhao Y J et al. CD93 regulates breast cancer growth and vasculogenic mimicry through the PI3K/AKT/SP2 signaling pathway activated by integrin β1 [J]. J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2024, 38(4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Peng Y, Wang Y Y, Zhou C et al. PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its role in Cancer therapeutics: are we making Headway? [J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Leiphrakpam PD. Are C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway as a target for Colorectal Cancer treatment [J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2024, 25(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Xu Z, Wu S, Tu J, et al. RACGAP1 promotes lung cancer cell proliferation through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [J]. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):8694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.