Abstract

Background

Prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is of greater concern in Asians, considering their relatively smaller annular sizes compared with Westerners. However, the prognostic significance of PPM in Asian populations has not been demonstrated.

Objectives

This study aimed to elucidate the prognostic value of PPM after TAVR in Asian patients.

Methods

Patients undergoing TAVR from October 2013 to December 2019 were enrolled from the OCEAN-TAVI (Optimized CathEter vAlvular iNtervention—Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) registry. PPM was classified based on the indexed effective orifice area as severe (≤0.65 cm2/m2) or moderate (0.66-0.85 cm2/m2) in the general population, and severe (≤0.55 cm2/m2) or moderate (0.56-0.70 cm2/m2) in the obese population (body mass index of ≥30 kg/m2).

Results

Of the 7,072 eligible patients, moderate and severe PPM were identified in 742 (10.5%) and 94 (1.3%) patients, respectively. Severe PPM relative to non-PPM was independently associated with higher adjusted risks for 3-year all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.16-2.78; P = 0.009) and heart failure hospitalization (adjusted HR: 1.88; 95% CI: 1.07-3.28; P = 0.027), whereas no significant difference in these outcomes was observed between moderate PPM and no PPM.

Conclusions

Severe PPM following TAVR was observed in only 1.3% of our Japanese cohort, but was associated with an increased risk of mortality and heart failure hospitalization at 3 years. These results warrant the implementation of preventive strategies to obviate severe PPM after TAVR, also in Asian patients.

Key Words: aortic stenosis, heart failure, long-term outcomes, prosthesis–patient mismatch, transcatheter aortic valve replacement

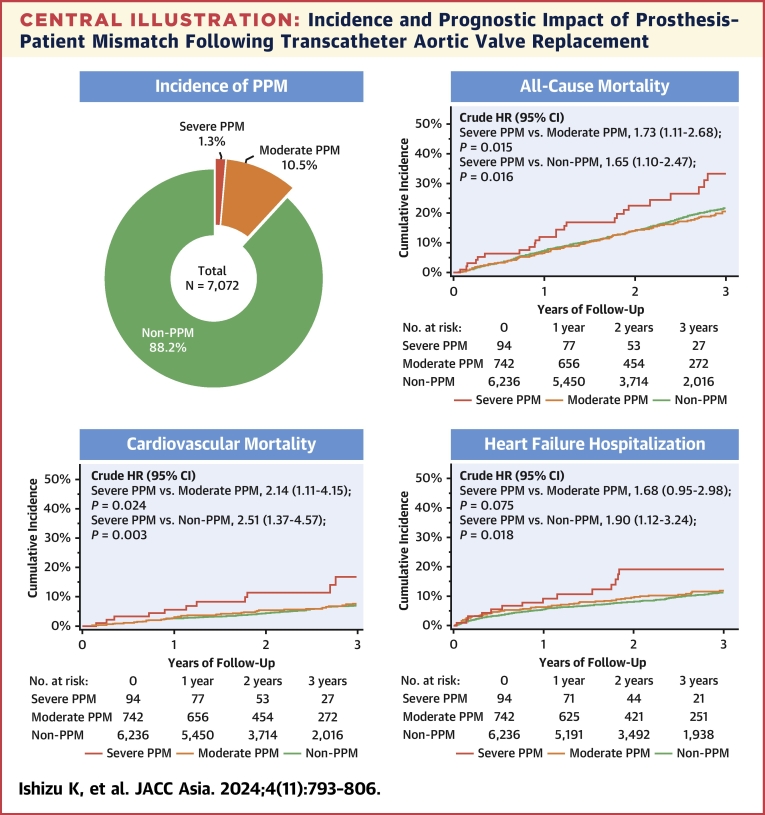

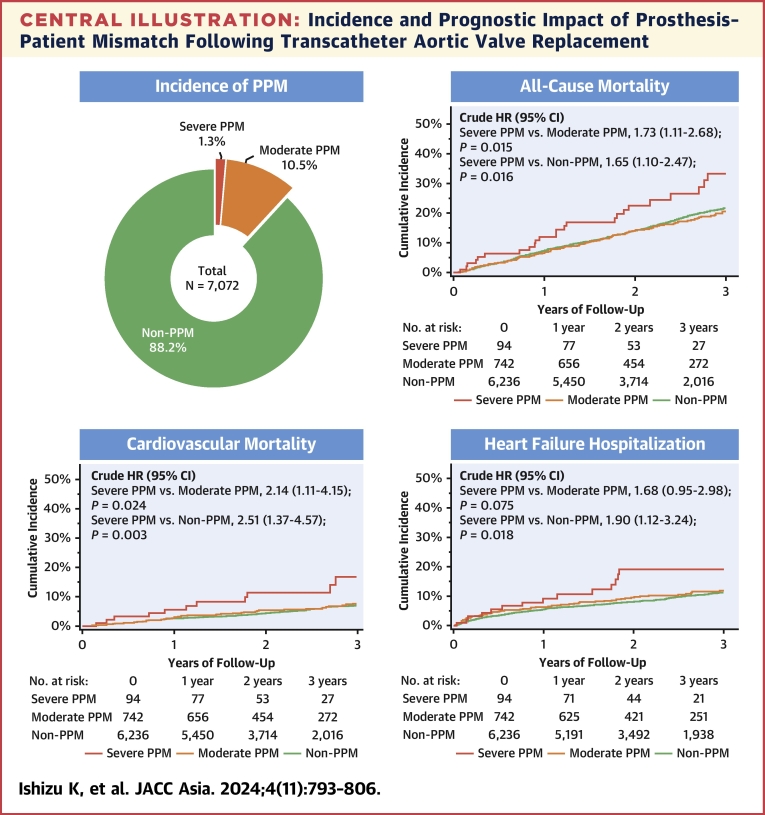

Central Illustration

Prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM), which was first described by Rahimtoola1 in 1978, is currently categorized as a nonstructural valvular dysfunction that occurs when an implanted prosthesis is too small relative to the patient’s body size, causing a smaller indexed effective orifice area (EOA) and a higher residual gradient than expected.2,3 In general, transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) offers superior hemodynamic performance of prostheses compared with surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR);4,5 however, the incidence of PPM after TAVR has widely ranged with its inconsistent clinical impact. A large study including 62,125 patients from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy registry revealed that the rates of moderate and severe PPM following TAVR were at 25% and 12%, respectively, and severe PPM was an independent risk factor of 1-year mortality and heart failure (HF) rehospitalization.6 Conversely, a Japanese multicenter study, including 1,546 patients from our OCEAN-TAVI (Optimized CathEter vAlvular iNtervention-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) registry, identified moderate and severe PPM were identified in only 8.9% and 0.7% of patients in the Asian cohort, respectively, and neither moderate nor severe PPM was associated with an increased risk of 1-year adverse outcomes.7 The study discussed that the lower PPM incidence, which was attributed to the smaller body size relative to the annulus dimensions in Asian populations as compared with non-Asian populations, may have led to insufficient assessment of the prognostic relevance, especially for severe PPM. Moreover, given that the TAVR indications are expanding towards younger populations with a lower surgical risk, robust evidence using larger cohort data with longer follow-up is warranted. Therefore, the present study aimed to re-evaluate the longer-term prognostic value of moderate and severe PPM in patients undergoing TAVR using a larger cohort of data from the Japanese multicenter OCEAN-TAVI registry.

Methods

Study population and design

We evaluated the data of 7,393 patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who underwent TAVR from October 2013 to December 2019 that were available from the OCEAN-TAVI registry, an ongoing, prospective, multicenter TAVR registry that includes data reported by 15 institutions in Japan. This trial is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN000020423). Enrolled patients were identified as eligible candidates for TAVR rather than SAVR by a consensus among surgeons at the individual centers and through discussions among cardiologists managing patients with multiple comorbidities. TAVR procedures were performed following the standards of each participating center with the balloon-expandable Edwards SAPIEN XT and SAPIEN 3 valves (Edwards Lifesciences) or the self-expandable Medtronic CoreValve, Evolut R, and Evolut PRO valves (Medtronic). The prosthesis type, size, and approach site were determined based on preprocedural echocardiographic and multidetector computed tomographic findings. The area in the balloon-expandable valve (BEV) and the perimeter in the self-expandable valve (SEV) were used to evaluate the degrees of oversizing relative to the annulus. Clinical data, including patient characteristics, echocardiographic data, procedural variables, and clinical outcomes in terms of mortality and HF hospitalization, were prospectively recorded. The institutional review board of each hospital approved the study protocol, and all patients signed written informed consent before TAVR.

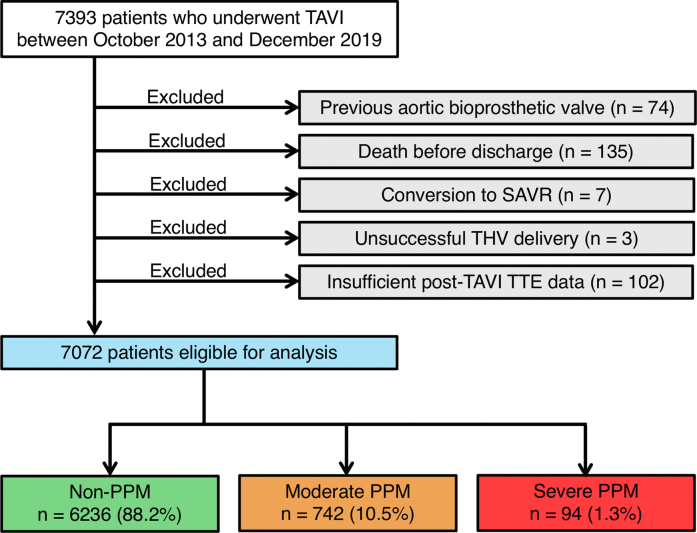

After excluding 321 patients because of a previous aortic bioprosthetic valve (n = 74), death before discharge (n = 135), conversion to SAVR (n = 7), unsuccessful valve delivery (n = 3), and insufficient post-TAVR echocardiographic data (n = 102), we analyzed the remaining 7,072 patients to assess the effect of PPM on clinical outcomes after TAVR (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

The flowchart provides information about the included and excluded patients. Based on the indexed effective orifice area, patients eligible for analysis were categorized into the following 5 groups: non-prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM), moderate PPM, and severe PPM. SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVI = transcatheter aortic valve implantation; THV = transcatheter heart valve; TTE = transthoracic echocardiography.

Echocardiographic assessment and definition

Echocardiography was performed before TAVR and at discharge, and its parameters were evaluated according to the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography.8 Continuous-wave Doppler was used to measure the mean transaortic valve gradient. A multiparametric approach was used to assess postprocedural regurgitation severity, classified as none/trivial, mild, moderate, and severe. EOA was measured by postprocedural echocardiography using the continuity equation and indexed to the body surface area (BSA) to derive the indexed EOA. PPM was classified based on the indexed EOA as severe (≤0.65 cm2/m2) or moderate (0.66-0.85 cm2/m2) in the general population and severe (≤0.55 cm2/m2) or moderate (0.56-0.70 cm2/m2) in the obese population (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2) according to the recommendations for imaging assessment from Lancellotti et al9 and the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-3) criteria.10 AS subtype classification before TAVR was defined according to the guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS).11 Patients were divided into 4 groups based on stroke volume (SV) index and mean aortic gradient, defined as “normal-flow (SV index ≥35 mL/m2), high-gradient (mean aortic gradient ≥40 mm Hg),” “normal-flow (SV index ≥35 mL/m2), low-gradient (mean aortic gradient <40 mm Hg),” “low-flow (SV index <35 mL/m2), high-gradient (mean aortic gradient ≥40 mm Hg),” or “low-flow (SV index <35 mL/m2), low-gradient (mean aortic gradient <40 mm Hg.”

Outcome measures and follow-up

All procedural and clinical outcomes except PPM were defined according to the VARC-2 criteria and were prospectively recorded.12 The primary outcome measures of this study include all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF rehospitalization during the 3-year follow-up period after the index TAVR. The definition of cardiovascular mortality was also applied to the VARC-2 criteria,12 and death due to cardiac causes and noncoronary vascular conditions, such as stroke with neurological events, procedure-related aortic dissection, rupture, or other vascular diseases, were included. All procedure- and valve-associated deaths and sudden, unwitnessed, or unknown deaths were categorized as cardiovascular mortality.

Information on the possible occurrence and/or causes of death was obtained from each hospital team through interviews at the planned hospital visits or by telephone interviews and questionnaires. The cause of death, in particular, was obtained by contacting the bereaved family or a physician at the hospital where the patient died. Clinical research coordinators specifically trained in recording TAVR procedures or experienced physicians confirmed the proper data recording. Data reported on the Internet-based system were evaluated through self-audits performed by the respective sites. The data committee members regularly audited the database for completeness and consistency.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described as number and percentages and were compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables, whose normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, were described as the mean ± SD or median (Q1-Q3), and group differences were evaluated using 1-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis test depending on their distributions. Cumulative event rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier estimation. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to determine predictors with these HRs for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization. To test the predictive ability of the PPM, multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were constructed, which comprised variables known to be associated with poor prognosis based on clinical plausibility13,14 or yielding P values of <0.10 in the univariate analysis. Model 1 assessed the effect of “severe PPM” by taking “not severe PPM” as reference, whereas model 2 assessed the effect of “moderate PPM” and “severe PPM” by taking “non-PPM” as reference. Proportional hazard assumptions for potential risk-adjusting variables were assessed on the plots of log (time) vs log [−log (survival)] stratified by the variable, and the assumptions were verified to be acceptable for all the variables. A restricted cubic spline was used to detect the possible nonlinear dependency of the association between the indexed EOA and HR for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization, using 4 knots at prespecified locations following the percentiles of the distribution of indexed EOA, the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles. The reference value of the indexed EOA was set at 0.85 cm2/m2, which is the boundary line between PPM and non-PPM. Additional subgroup mortality models were constructed to assess interactions between severe PPM and age (dichotomized by the median); sex; Clinical Frailty Scale (4< or ≥4); Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score (<8% or ≥8%); baseline atrial fibrillation; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (<40% or ≥40%); mean aortic gradient (<40 or ≥40 mm Hg); and SV index (<35 or ≥35 mL/m2). Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the predictors of severe PPM. The variance inflation factor was used to check for multicollinearity for each variable, and obtained variance inflation factor value ranged between 1 and 2.

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 14.2.0 (SAS Institute) and R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All reported P values were 2-tailed, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 7,072 patients eligible for inclusion, moderate and severe PPM were observed in 742 (10.5%) and 94 (1.3%) patients, respectively (Figure 1, Supplemental Figure 1). The baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In total, the median age of patients was 85 years, 32% of patients were male, and the median STS score was 6.1%. Patients with PPM were younger, less likely to be frail, and had a higher BSA compared with those without PPM. The prevalence of NYHA functional class III/IV and chronic kidney disease was also higher in patients with PPM. With regard to echocardiographic data, patients with PPM had a smaller aortic valve area (AVA), smaller indexed AVA, decreased LVEF, lower SV index, and higher systolic pulmonary artery pressure. Subtypes of AS were also significantly associated with the incidence of PPM, with an increased risk of PPM in low-flow patients regardless of high or low mean aortic gradient (Supplemental Figure 2). Concomitant mitral regurgitation ≥ moderate was more prevalent in patients with PPM. Moreover, the computed tomographic data demonstrate that smaller aortic annulus dimensions at baseline were significantly associated with PPM after TAVR.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| All (N = 7,072) | Non-PPM (n = 6,236) | Moderate PPM (n = 742) | Severe PPM (n = 94) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | 85 (81-88) | 85 (81-88) | 84 (81-87) | 83 (80-86) | <0.001 |

| Male | 2,241 (31.7) | 2,002 (32.1) | 210 (28.3) | 29 (30.9) | 0.103 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.40 (1.30-1.57) | 1.40 (1.30-1.56) | 1.48 (1.36-1.60) | 1.50 (1.38-1.63) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale ≥4 | 4,027 (57.0) | 3,618 (58.1) | 362 (48.8) | 47 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class Ⅲ/Ⅳ | 2,859 (40.4) | 2,485 (39.9) | 325 (43.8) | 49 (52.1) | 0.008 |

| STS risk score, % | 6.1 (4.2-9.1) | 6.2 (4.2-8.6) | 5.8 (4.2-8.6) | 6.0 (3.6-9.4) | 0.135 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 5,898 (83.4) | 5,182 (83.1) | 640 (86.3) | 76 (80.9) | 0.067 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3,919 (55.4) | 3,429 (55.0) | 441 (59.4) | 49 (52.1) | 0.056 |

| Diabetes | 1,911 (27.0) | 1,678 (26.9) | 199 (26.8) | 34 (36.2) | 0.149 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1,492 (21.1) | 1,289 (20.7) | 181 (24.4) | 22 (23.4) | 0.057 |

| CAD | 2,314 (32.7) | 2,016 (32.3) | 266 (35.9) | 32 (34.0) | 0.153 |

| Previous CABG | 305 (4.3) | 256 (4.1) | 45 (6.1) | 4 (4.3) | 0.061 |

| PAD | 761 (10.8) | 656 (10.5) | 92 (12.4) | 13 (13.8) | 0.200 |

| CKD, eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 4,935 (69.8) | 4,309 (69.1) | 554 (74.7) | 72 (76.6) | 0.002 |

| Liver disease | 154 (2.2) | 131 (2.1) | 20 (2.7) | 3 (3.2) | 0.486 |

| COPD | 669 (9.5) | 588 (9.4) | 67 (9.0) | 14 (14.9) | 0.226 |

| Previous stroke | 780 (11.0) | 687 (11.0) | 78 (10.5) | 15 (16.0) | 0.319 |

| Previous pacemaker | 387 (5.5) | 327 (5.2) | 54 (7.3) | 6 (6.4) | 0.081 |

| Echocardiographic data | |||||

| AVA, cm2 | 0.63 (0.50-0.76) | 0.64 (0.51-0.76) | 0.58 (0.47-0.70) | 0.54 (0.40-0.68) | <0.001 |

| Indexed AVA, cm2/m2 | 0.42 (0.36-0.50) | 0.44 (0.30-0.51) | 0.40 (0.30-0.50) | 0.38 (0.30-0.41) | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic gradient, mm Hg | 46.8 (37.0-60.3) | 46.0 (37.0-60.0) | 48.0 (38.0-63.0) | 50.3 (37.0-68.3) | 0.025 |

| LVEF, % | 63.0 (54.0-68.3) | 63.0 (54.0-68.3) | 63.0 (54.0-68.7) | 60.9 (46.0-66.0) | 0.038 |

| Stroke volume index, mL/m2 | 44.6 (35.7-53.9) | 45.2 (36.2-54.5) | 40.7 (33.9-49.1) | 38.3 (29.7-46.7) | <0.001 |

| Subtypes of AS | |||||

| Normal-flow, high-gradient | 3,904 (55.7) | 3,466 (56.1) | 397 (53.8) | 41 (44.1) | <0.001 |

| Normal-flow, low-gradient | 1513 (21.6) | 1365 (22.1) | 137 (18.6) | 11 (11.8) | |

| Low-flow, high-gradient | 889 (12.7) | 735 (11.9) | 127 (17.2) | 27 (29.0) | |

| Low-flow, low-gradient | 704 (10.0) | 613 (9.9) | 77 (10.4) | 14 (15.1) | |

| AR ≥moderate | 717 (10.1) | 620 (9.9) | 80 (10.8) | 17 (18.1) | 0.049 |

| MR ≥moderate | 806 (11.4) | 684 (11.0) | 102 (13.8) | 20 (21.3) | 0.002 |

| TR ≥moderate | 624 (8.8) | 538 (8.6) | 74 (10.0) | 12 (12.8) | 0.214 |

| SPAP, mm Hg | 30.0 (25.0-38.0) | 30.0 (25.0-37.0) | 31.7 (26.0-40.0) | 33.0 (27.5-42.0) | <0.001 |

| MDCT data | |||||

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 509 (7.2) | 481 (7.7) | 23 (3.1) | 5 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Annulus area, mm2 | 395.0 (353.0-450.0) | 398.0 (355.0-453.0) | 377.8 (335.5-426.0) | 374.1 (339.0-415.2) | <0.001 |

| Annulus perimeter, mm | 71.9 (67.9-76.6) | 72.1 (68.0-76.9) | 70.3 (66.2-74.7) | 70.7 (67.3-74.2) | <0.001 |

| LVOT calcification ≥moderate | 308 (4.4) | 269 (4.3) | 34 (4.6) | 5 (5.3) | 0.855 |

Values are median (Q1-Q3) or n (%).

AR = aortic regurgitation; AVA = aortic valve area; BSA = body surface area; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD = coronary artery disease; CKD = chronic kidney disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT = left ventricular outflow tract; MDCT = multidetector computed tomography; MR = mitral regurgitation; PAD = peripheral artery disease; PPM = prosthesis–patient mismatch; SPAP = systolic pulmonary artery pressure; STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TR = tricuspid regurgitation.

Procedure characteristics and in-hospital outcomes

The procedure characteristics and in-hospital clinical outcomes are presented in Table 2. SAPIEN XT, SAPIEN 3, CoreValve, and Evolut R/PRO were used in 1,399 (19.8%), 4,026 (58.9%), 198 (2.8%), and 1,449 (20.5%) patients, respectively. Compared with patients without PPM, those with PPM received SAPIEN 3 or CoreValve more frequently. The incidence rates of severe PPM in patients treated with BEV were 5.0%, 1.6%, 0.7%, and 1.4% for 20-, 23-, 26-, and 29-mm prostheses, respectively (P < 0.001), whereas those in patients received SEV were 0.5%, 1.2%, and 0.5% for 23-, 26-, and 29-mm prostheses, respectively (P = 0.318) (Supplemental Figure 3). Prosthesis oversizing in relation to annulus for both BEV and SEV tended to be lower in patients with PPM, albeit without statistical significance. No significant group differences were also observed in terms of the prevalence of in-hospital mortality and complications, including acute kidney injury, disabling stroke, bleeding, vascular complications, and new pacemaker implantation.

Table 2.

Procedural Characteristics and Outcomes

| All (N = 7,072) | Non-PPM (n = 6,236) | Moderate PPM (n = 742) | Severe PPM (n = 94) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural variables | |||||

| Local anesthesia | 2,581 (36.5) | 2,269 (36.4) | 275 (37.1) | 37 (39.4) | 0.793 |

| Predilatation | 3,581 (50.6) | 3,177 (51.0) | 362 (48.8) | 42 (44.7) | 0.274 |

| Postdilatation | 1,663 (18.1) | 1,531 (24.6) | 115 (15.5) | 17 (18.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedure time, min | 62 (48-86) | 61 (48-85) | 64 (49-93) | 68 (48-99) | 0.011 |

| Contrast volume, mL | 90 (58-127) | 91 (60-128) | 80 (50-120) | 76 (48-109) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay after TAVR, d | 8 (6-13) | 8 (6-13) | 8 (6-12) | 8 (6-14) | 0.199 |

| Access site | |||||

| Transfemoral | 6,456 (91.3) | 5,681 (91.1) | 690 (93.0) | 85 (90.4) | 0.197 |

| Alternative | 616 (8.7) | 555 (8.9) | 52 (7.0) | 9 (9.6) | |

| Prosthesis type | |||||

| SAPIEN XT | 1,399 (19.8) | 1,265 (20.3) | 121 (16.3) | 13 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| SAPIEN 3 | 4,026 (58.9) | 3,472 (55.7) | 487 (65.6) | 67 (71.3) | |

| CoreValve | 198 (2.8) | 173 (2.8) | 20 (2.7) | 5 (5.3) | |

| Evolut R/Evolut PRO | 1,449 (20.5) | 1,326 (21.3) | 114 (15.4) | 9 (9.6) | |

| Prosthesis size | |||||

| BEV, SAPIEN XT/SAPIEN 3 | |||||

| 20 mm | 279 (5.1) | 183 (3.9) | 82 (13.5) | 14 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| 23 mm | 3,005 (55.4) | 2,582 (54.5) | 375 (61.7) | 48 (60.0) | |

| 26 mm | 1,786 (32.9) | 1,638 (34.6) | 135 (22.2) | 13 (16.3) | |

| 29 mm | 355 (6.5) | 334 (7.1) | 16 (2.6) | 5 (6.3) | |

| Oversizing ratio, % | 12.0 (4.6-19.8) | 12.1 (4.8-19.9) | 11.4 (3.6-19.2) | 9.4 (2.1-18.1) | 0.131 |

| SEV, CoreValve/Evolut R/Evolut PRO | |||||

| 23 mm | 197 (12.0) | 164 (10.9) | 32 (23.9) | 1 (7.1) | 0.001 |

| 26 mm | 851 (51.7) | 782 (52.2) | 59 (44.0) | 10 (71.4) | |

| 29 mm | 599 (36.4) | 553 (36.9) | 43 (32.1) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Oversizing ratio, % | 18.3 (14.1-22.2) | 18.3 (14.2-22.2) | 17.7 (13.5-21.8) | 13.5 (10.3-21.4) | 0.140 |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||||

| New-onset AF | 192 (2.7) | 173 (2.8) | 17 (2.3) | 2 (2.1) | 0.688 |

| Coronary artery occlusion | 40 (0.6) | 36 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0.580 |

| Disabling stroke | 65 (0.9) | 60 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (1.1) | 0.466 |

| Acute kidney injury | 529 (7.5) | 471 (7.6) | 50 (6.7) | 8 (8.5) | 0.672 |

| Major vascular complications | 215 (3.0) | 184 (3.0) | 29 (3.9) | 2 (2.1) | 0.331 |

| Life-threatening and major bleeding | 597 (8.4) | 529 (8.5) | 59 (8.0) | 9 (9.6) | 0.819 |

| Need for pacemaker | 565 (8.0) | 503 (8.1) | 56 (7.6) | 6 (6.4) | 0.740 |

Values are n (%) or median (Q1-Q3).

AF = atrial fibrillation; BEV = balloon-expandable valve; SEV = self-expandable valve; PPM = prosthesis–patient mismatch; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Table 3 shows postprocedural echocardiographic data at discharge. Patients with PPM had a significantly higher mean aortic gradient and higher systolic pulmonary artery pressure. No significant group difference in the rate of paravalvular leakage was observed, albeit with a numerically higher incidence in the severe PPM group. A mean aortic gradient of ≥40 mm Hg was determined for 2 patients only in the severe PPM group.

Table 3.

Postprocedural Echocardiographic Data

| All (N = 7,072) | Non-PPM (n = 6,236) | Moderate PPM (n = 742) | Severe PPM (n = 94) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOA, cm2 | 1.63 (1.37-1.93) | 1.70 (1.47-2.00) | 1.13 (1.05-1.23) | 0.89 (0.77-0.97) | <0.001 |

| Indexed EOA, cm2/m2 | 1.14 (0.96-1.35) | 1.18 (1.02-1.38) | 0.78 (0.73-0.82) | 0.60 (0.56-0.63) | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic gradient, mm Hg | 10.2 (7.9-13.7) | 10.0 (7.3-13.0) | 13.6 (10.1-17.0) | 15.5 (11.9-20.0) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % | 63 (54.0-68.3) | 63.0 (60.0-69.3) | 65.0 (59.7-68.8) | 63.3 (56.8-69.0) | 0.500 |

| Mild PVL | 2,036 (28.8) | 1,768 (28.4) | 239 (32.2) | 29 (30.9) | 0.085 |

| PVL ≥moderate | 141 (2.0) | 116 (1.9) | 20 (2.7) | 5 (5.3) | 0.051 |

| MR ≥moderate | 515 (7.3) | 441 (7.1) | 64 (8.6) | 10 (10.6) | 0.159 |

| TR ≥moderate | 583 (8.2) | 501 (8.0) | 70 (9.4) | 12 (12.8) | 0.142 |

| SPAP, mm Hg | 31.0 (25.0-38.0) | 30.4 (25.0-38.0) | 32.0 (26.0-39.0) | 32.7 (26.0-40.0) | 0.005 |

Values are median (Q1-Q3) or n (%).

EOA = effective orifice area; PVL = paravalvular leakage; SPAP = systolic pulmonary artery pressure; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Clinical outcomes during follow-up

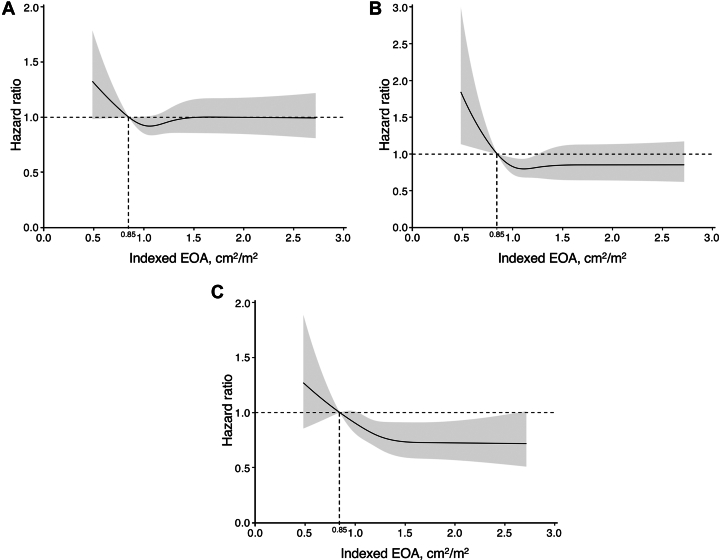

The clinical follow-up rate at 1 year was 96.7% with a median follow-up of 769 days (Q1-Q3: 454-1,229 days). During the follow-up period, a total of 1,173 patients with all-cause death were identified; 363 patients (30.9%) died for cardiovascular reasons, and the remaining 810 patients (69.1%) died for noncardiovascular reasons. HF hospitalization was required in 624 patients. The results of the univariate analysis for the association between these adverse outcomes and clinical findings are presented in Supplemental Tables 1 to 3. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the cumulative 3-year all-cause mortality rates were significantly higher in patients with severe PPM (33.2%) but comparable in patients with moderate PPM (20.5%) and patients without PPM (21.7%) (crude HR for severe PPM vs moderate PPM: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.11-2.68; P = 0.015; crude HR for moderate PPM vs non-PPM: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.78-1.15; P = 0.578) (Central Illustration). Additionally, the cumulative 3-year cardiovascular mortality rates were significantly higher in patients with severe PPM (16.8%) but comparable in patients with moderate PPM (7.8%) and without PPM (7.0%) (crude HR for severe PPM vs moderate PPM: 2.14; 95% CI: 1.11-4.15; P = 0.024; crude HR for moderate PPM vs non-PPM: 1.17; 95% CI: 0.85-1.60; P = 0.332) (Central Illustration). HF hospitalization occurred in 19.1%, 11.9%, and 11.4% of patients with severe, moderate, and non-PPM, respectively (crude HR for severe PPM vs moderate PPM: 1.68; 95% CI: 0.95-2.98; P = 0.075; crude HR for moderate PPM vs non-PPM: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.87-1.42; P = 0.401) (Central Illustration). Even after adjusting for clinical confounding factors, severe PPM as compared with not severe (moderate or non-) PPM was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.16-2.78; P = 0.009), cardiovascular mortality (adjusted HR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.42-5.14; P = 0.002), and HF hospitalization (adjusted HR: 1.88; 95% CI: 1.07-3.28; P = 0.027) (Table 4). In post hoc analyses, the differences in the cardiovascular mortality and in the rate of HF hospitalization tended to diverge later than 1 year (Supplemental Figure 4). On the basis of restricted cubic spline models, a continuous relationship between indexed EOA and adjusted HR for each adverse outcome was drawn, using a reference value of indexed EOA of 0.85 cm/m2 (Figure 2). The adjusted HRs were almost constant as the indexed EOA increased for any of these outcomes, from around the point where it exceeded 1.0 cm2/m2.

Central Illustration.

Incidence and Prognostic Impact of Prosthesis–Patient Mismatch Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

The incidence of prosthesis–patient mismatch (PPM) after transcatheter aortic valve replacement is shown in the left upper panel. The other panels show Kaplan-Meier curves for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and heart failure hospitalization, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier curves were truncated at 3 years.

Table 4.

Event Rates and Association of PPM With 3-Year Endpoints

| Event Rate, % | Crude HR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortalitya | |||||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs not severe PPM | 33.2 vs 21.6 | 1.65 (1.10-2.48) | 0.015 | 1.79 (1.16-2.78) | 0.009 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs non-PPM | 33.2 vs 21.7 | 1.65 (1.10-2.47) | 0.016 | 1.81 (1.16-2.81) | 0.008 |

| Moderate PPM vs non-PPM | 20.5 vs 21.7 | 0.95 (0.78-1.15) | 0.578 | 1.16 (0.90-1.38) | 0.310 |

| Cardiovascular mortalityb | |||||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs not severe PPM | 16.8 vs 7.1 | 2.46 (1.35-4.48) | 0.003 | 2.70 (1.42-5.14) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs non-PPM | 16.8 vs 7.0 | 2.51 (1.37-4.57) | 0.003 | 2.74 (1.43-5.22) | 0.002 |

| Moderate PPM vs non-PPM | 7.8 vs 7.0 | 1.17 (0.85-1.60) | 0.332 | 1.14 (0.79-1.64) | 0.493 |

| Heart failure hospitalizationc | |||||

| Model 1 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs not severe PPM | 19.1 vs 11.4 | 1.88 (1.10-3.19) | 0.020 | 1.88 (1.07-3.28) | 0.027 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Severe PPM vs non-PPM | 19.1 vs 11.4 | 1.90 (1.12-3.24) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.04-3.20) | 0.035 |

| Moderate PPM vs non-PPM | 11.9 vs 11.4 | 1.11 (0.87-1.42) | 0.401 | 0.97 (0.73-1.26) | 0.840 |

CKD was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Adjusted for the following variables: age; sex; BSA; body mass index (BMI); Clinical Frailty Scale; NYHA functional class Ⅲ/Ⅳ; STS risk score; dyslipidemia; diabetes; atrial fibrillation; CAD; PAD; CKD; liver disease; COPD; previous pacemaker; mean aortic gradient; LVEF; stroke volume (SV) index; MR ≥moderate; TR ≥moderate; SPAP; and transfemoral approach.

Adjusted for the following variables: age; sex; BSA; BMI; Clinical Frailty Scale; NYHA functional class Ⅲ/Ⅳ; STS risk score; hypertension; dyslipidemia; atrial fibrillation; previous CABG; PAD; CKD; liver disease; COPD; previous pacemaker; mean aortic gradient; LVEF; SV index; MR ≥ moderate; TR ≥ moderate; and SPAP.

Adjusted for the following variables: age; sex; BSA; BMI; Clinical Frailty Scale; NYHA functional class Ⅲ/Ⅳ; STS risk score; hypertension; dyslipidemia; diabetes; atrial fibrillation; CAD; previous CABG; PAD; CKD; COPD; previous pacemaker; AVA; mean aortic gradient; LVEF; SV index; MR ≥moderate; TR ≥moderate; SPAP; and transfemoral approach.

Figure 2.

Spline Curves of Indexed EOA and Adjusted Risks for Outcomes

Continuous relationships between indexed effective orifice area (EOA) and adjusted HR for (A) all-cause mortality, (B) cardiovascular mortality, and (C) heart failure hospitalization at 3 years, based on restricted cubic splines. The reference value of indexed EOA was set at 0.85 cm2/m2. In each panel, the solid line and the shaded area represent the HR and its 95% CI, respectively.

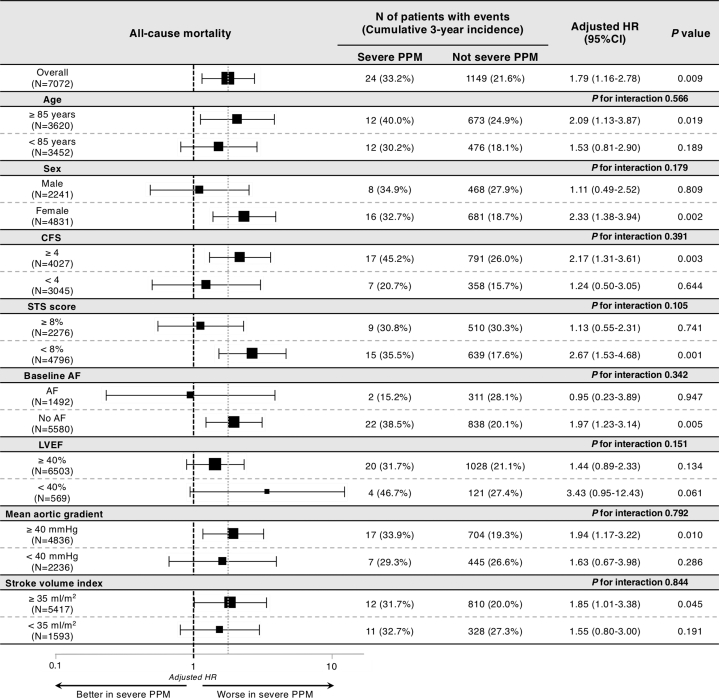

In addition, we dichotomized patients according to the potential risk modifiers of severe PPM for mortality, such as age, sex, Clinical Frailty Scale, STS score, baseline atrial fibrillation, LVEF, mean aortic gradient, and SV index. No significant interaction was observed between the adjusted risk of severe PPM relative to not severe (moderate or non-) PPM and these subgroups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup Analysis of Association Between Severe PPM and 3-Year Mortality

Forest plots for the adjusted HRs of 3-year all-cause mortality. To calculate HRs and interactions, we incorporated the risk-adjusting variables listed in Table 4. AF = atrial fibrillation; CFS = Clinical Frailty Scale; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PPM = prosthesis–patient mismatch; STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

Predictors of the PPM

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was utilized to determine the predictors of severe PPM (Table 5). Independent predictors included larger BSA (OR: 1.44 per 0.1-mm2 increase; 95% CI: 1.26-1.66; P < 0.001), smaller AVA (OR: 1.29 per 0.1-cm2 decrease; 95% CI: 1.11-1.49; P < 0.001), lower SV index (OR: 1.29 per 10-mL/m2 decrease; 95% CI: 1.05-1.57; P = 0.014), aortic regurgitation (AR) ≥ moderate (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.10-3.33; P = 0.021), mitral regurgitation (MR) ≥ moderate (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.01-3.05; P = 0.044), annulus area of <400 mm2 (OR: 3.42; 95% CI: 2.06-5.67; P <0.001), and use of BEV (OR: 2.28; 95% CI: 1.23-4.23; P = 0.009).

Table 5.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Predictors of Severe PPM

| Univariate Analysis |

Multivariable Analysis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age, per 1-y increase | 0.95 | 0.92-0.99 | 0.009 | 0.96 | 0.93-1.00 | 0.062 |

| Male | 0.96 | 0.62-1.49 | 0.861 | — | — | — |

| BSA, per 0.1 m2 increase | 1.20 | 1.07-1.34 | 0.001 | 1.44 | 1.26-1.66 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.14 | 0.71-1.85 | 0.581 | — | — | — |

| LVEF, per 10% decrease | 1.24 | 1.07-1.44 | 0.006 | 1.11 | 0.93-1.31 | 0.244 |

| AVA, per 0.1-cm2 decrease | 1.31 | 1.15-1.48 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.11-1.49 | <0.001 |

| SV index, per 10-mL/m2 decrease | 1.51 | 1.28-1.79 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1.05-1.57 | 0.014 |

| AR ≥ moderate | 1.98 | 1.16-3.37 | 0.012 | 2.05 | 1.17-3.59 | 0.012 |

| MR ≥ moderate | 2.13 | 1.29-3.51 | 0.003 | 1.76 | 1.01-3.05 | 0.044 |

| TR ≥ moderate | 1.52 | 0.83-2.80 | 0.178 | — | — | — |

| Annulus area <400 mm2 | 1.82 | 1.18-2.81 | 0.007 | 3.42 | 2.06-5.67 | <0.001 |

| Prosthesis type: BEV vs SEV | 1.81 | 1.01-3.12 | 0.047 | 2.28 | 1.23-4.23 | 0.009 |

| Predilatation | 0.78 | 0.52-1.18 | 0.246 | — | — | — |

| Postdilatation | 0.72 | 0.42-1.21 | 0.715 | — | — | — |

Discussion

This multicenter study evaluated the long-term prognostic value of PPM in Asian patients who underwent TAVR. The main findings of the study are summarized as follows: 1) the incidence of moderate and severe PPM after TAVR in this cohort was 10.5% and 1.3%, respectively; 2) predictors of severe PPM included larger BSA, smaller AVA, lower SV index, AR ≥ moderate, MR ≥ moderate, annulus area of <400 mm2, and use of BEV; 3) severe PPM, but not moderate PPM, was independently associated with an increased risk of 3-year all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization; and 4) the relevant subgroup analysis according to age, sex, Clinical Frailty Scale, STS score, baseline atrial fibrillation, LVEF, mean aortic gradient, and SV index demonstrated no significant interactions between severe PPM and these variables in terms of 3-year all-cause mortality.

Since the conceptualization of PPM originally raised in 1978,1 several studies have investigated the incidence of PPM and its impact on clinical outcomes. Although previous studies have shown superior hemodynamic status with a lower incidence of PPM in TAVR as compared with SAVR, which may derive from the fact that TAVR generally enables larger prostheses implantation due to the thinner strut and the absence of a sewing ring,15, 16, 17 moderate and severe PPM were still identified in 9% to 40% and 1% to 25% of patients, respectively.5, 6, 7,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 There are 2 major potential reasons why the incidence of PPM varies across those reports. The first is the different proportions of prosthesis types used. Reportedly, supra-annular SEVs provide a larger EOA, thereby reducing the incidence of PPM, compared with intra-annular BEVs19 or intra-annular SEVs.17 Additionally, the incidence of PPM appears to be higher with later generation TAVR devices owing to the development of a skirt or external covering to help mitigate paravalvular leakage, thereby reducing the EOA.22 The second is racial differences, mainly in body size. Asian patients have several anatomical and procedural characteristics, including smaller body size, smaller aortic complex size, and accordingly, smaller prostheses selected, compared with non-Asian patients.23 In this context, the increased risk of PPM would be of greater concern for Asians than for non-Asians; however, our group previously reported that the incidence of moderate and severe PPM in Asians is unexpectedly as low as 8.9% and 0.7%, respectively,7 and a recent report from the TP-TAVR (Transpacific Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement) registry directly comparing racial groups demonstrated that significant PPM was less frequent in Asian patients than in non-Asian patients.21 These results indicate that Asians, as compared with non-Asians, have a relatively larger aortic annulus for the body size. Indeed, the current Japanese multicenter study, where the low incidence of moderate (10.5%) and severe (1.3%) PPM was also detected, revealed the ratio of annulus size to BSA (annulus diameter divided by BSA) of 15.7 mm/m2, which is higher than the previously reported ratio of 11.3 to 12.7 mm/m2 in non-Asian cohorts.18,21

Several studies have reported that predictors of PPM after TAVR include larger body size,6,7,21,22,24,25 female sex,6 younger age,6,7,16,22 non-Asian race,21 smaller prosthesis size,6,7,22,26 balloon-expandable prosthesis,19,27 LV dysfunction,6,25 atrial fibrillation or flutter,6 more severe baseline AS,21,22,24 severe mitral or tricuspid regurgitation,6 and no post-dilatation.7,17,21,22 The predictors of severe PPM identified in the present study were all encompassed in those reported in previous studies, whereas we failed to demonstrate the predictive ability of post-dilatation for severe PPM. This should be interpreted with caution, as it may be attributable to the use of BEVs in more than three-quarters of the subjects in our registry and post-dilation is likely to be more selectively performed in those considered high risk for PPM. In discussing preventive strategies for severe PPM, we should highlight that among the predictors shown in our study, BSA and the use of BEV are modifiable factors. Regarding the former, losing weight naturally leads to lower BSA, whereas lower body weight, which is believed to reflect undernourishment, is associated with worse prognosis in patients with heart failure, a phenomenon that is often termed the obesity paradox. Therefore, excessive weight loss may be discouraged. Furthermore, there is a practical concern of whether intentional weight loss is feasible for elderly patients considered to be candidates for TAVR. Regarding the latter, the recently published SMART (Small Annuli Randomized To Evolut or SAPIEN) trial showed that particularly among patients with an annulus area of 430 mm2 or less, an SEV had a lower incidence of PPM than a BEV.28 This result may suggest the effectiveness of using an SEV to mitigate the risk of PPM in Asians because a considerable portion of them have small annuli. On the other hand, it should be noted that the trial was conducted for non-Asians with relatively large body sizes, and further studies including Asian patients are warranted.

Concerning the prognostic impact of PPM in patients undergoing TAVR, several previous studies also have yielded conflicting results. Some studies showed that PPM after TAVR is associated with adverse outcomes, including an increase in mortality17,29 and/or heart failure rehospitalization,6,7 less symptomatic improvement,24 an increased risk for acute kidney injury,30 and less LV mass regression.15,25,30 Of note, reduced overall survival was correlated only with severe PPM, not moderate PPM, in these studies. On the contrary, not a few studies failed to demonstrate the clinical impact of PPM after TAVR. The different results obtained in these studies are probably attributed, not only to the different prostheses used, but also to the various characteristics of the study populations, the size of which seems to be particularly important for illustrating the clinical impact of PPM. Indeed, the 2 studies that have successfully demonstrated the prognostic impact of severe PPM have both involved large populations. The first study has been reported from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy registry and has included 62,125 patients,6 and the second study is a meta-analysis of reconstructed time-to-event data from Kaplan-Meier curves of 23 studies, containing data on 81,969 patients.29 To the best of our knowledge, our study is the largest study on PPM after TAVR in Asian patients, with 7,072 patients included in the analysis, and the first to demonstrate that severe (but not moderate) PPM is associated with higher mortality and HF rehospitalization after adjustment for comorbid risk factors even in Asians. In other words, all the previous studies on Asians have reported that neither moderate nor severe PPM after TAVR was associated with an increased risk of mortality; however, this could have been simply because the lower PPM incidence attributed to the smaller body size relative to the annulus dimensions in Asian populations may have caused insufficient assessment of the prognostic relevance, especially for severe PPM. Moreover, given the results of landmark survival analyses in Supplemental Figure 4, not only the inclusion of a larger number of patients, but also the longer follow-up conducted in the current study than in the previous Asian studies, may have contributed to our success in demonstrating the prognostic impact of severe PPM.

We also conducted a subgroup analysis to determine potential modifiers of the excess risk of severe PPM. However, in terms of mortality, no significant interaction was observed between severe PPM and age, sex, BMI, Clinical Frailty Scale, STS score, baseline atrial fibrillation, LVEF, mean aortic gradient, or SV index. This result is mostly consistent with a large previous study of non-Asian subjects,6 but theoretically, reduced forward flow could modulate the prognostic impact of severe PPM. Indeed, another previous study demonstrated that severe PPM was independently associated with all-cause mortality after TAVR only in patients with LVEF of <40%,27 and our study also showed a tendency toward an increased risk of severe PPM in those with LVEF of <40%, albeit with no significant interaction. On the other hand, it is difficult to determine the reason why stratification by preprocedural SV index did not provide an excess risk of severe PPM, but data on post-procedural SV index may allow for a thorough discussion.

Study Limitations

First, this is a prospective, but observational, registry study and has inherent limitations as it is based on a retrospective analysis. However, the participation of several institutions in the study may have attenuated the potential selection and ascertainment biases. Second, residual confounders may affect the risk of PPM for adverse events, although we conducted extensive multivariable adjustment. Third, although a registry-derived consensus document was shared in each hospital regarding the echocardiographic assessment based on the guidelines,8 the EOA measurement by Doppler echocardiography could have been affected by technical pitfalls or measurement errors, and the accuracy and reproducibility could not be assessed due to the absence of independent core laboratory analysis. However, we believe that measured EOA rather than predicted EOA should be used for our analysis because predicted EOA specifically in TAVR populations was considered incorrect because the final degree of geometric expansion of the TAVR prosthesis may differ between cases. Fourth, procedural and clinical outcomes in our study population were defined according to the previous version of the VARC-2 criteria, because the OCEAN-TAVI registry has been prospectively constructed since 2013. Fifth, the present study did not include echocardiographic follow-up data after discharge; therefore, the effect of PPM on prosthesis durability was not evaluated. Finally, this cohort predominantly consisted of octogenarians. The inclusion of younger patients with fewer comorbidities and longer life expectancies may be required to more definitively investigate the clinical impact of PPM.

Conclusions

In our Japanese multicenter registry, moderate and severe PPM after TAVR were present in 10.5% and 1.3% of patients, respectively. Severe PPM, but not moderate PPM, was independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization at 3 years. These results support the implementation of preventive strategies to minimize the occurrence of severe PPM after TAVR, even in Asian patients with small body sizes. Further investigation regarding devices and techniques that mitigate the risk of PPM after TAVR is warranted.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Moderate and severe PPM after TAVR were present in 10.5% and 1.3% of patients, respectively, in our Japanese cohort. Severe PPM, but not moderate PPM, was independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalization at 3 years.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Results of the present study support the implementation of preventive strategies to minimize the occurrence of severe PPM after TAVR, even in Asian patients with small body sizes. Further investigation regarding devices and techniques that mitigate the risk of PPM following TAVR is warranted.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The OCEAN-TAVI registry is supported by Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Medical, and Daiichi-Sankyo Company. Dr Izumo is a screening proctor for Edwards Lifesciences. Drs Yohei Ohno, Yashima, and Asami are clinical proctors for Medtronic. Drs Naganuma, Ueno, Mizutani, and Takagi are clinical proctors for Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Drs Masanori Yamamoto, Shirai, Tada, Watanabe, and Hayashida are clinical proctors for Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Medical, and Medtronic. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators and institutions that have participated in the OCEAN-TAVI registry.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental figures and tables, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Rahimtoola S.H. The problem of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch. Circulation. 1978;58:20–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pibarot P., Dumesnil J.G. Prosthesis-patient mismatch: definition, clinical impact, and prevention. Heart. 2006;92(8):1022–1029. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.067363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capodanno D., Petronio A.S., Prendergast B., et al. Standardized definitions of structural deterioration and valve failure in assessing long-term durability of transcatheter and surgical aortic bioprosthetic valves: a consensus statement from the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52(3):408–417. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavel M.A., Webb J.G., Pibarot P., et al. Comparison of the hemodynamic performance of percutaneous and surgical bioprostheses for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(20):1883–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodes-Cabau J., Pibarot P., Suri R.M., et al. Impact of aortic annulus size on valve hemodynamics and clinical outcomes after transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(5):701–711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrmann H.C., Daneshvar S.A., Fonarow G.C., et al. Prosthesis–patient mismatch in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(22):2701–2711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyasaka M., Tada N., Taguri M., et al. Incidence, predictors, and clinical impact of prosthesis–patient mismatch following transcatheter aortic valve replacement in Asian patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(8):771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.01.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner H., Hung J., Bermejo J., et al. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.029. quiz 101-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lancellotti P., Pibarot P., Chambers J., et al. Recommendations for the imaging assessment of prosthetic heart valves: a report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Chinese Society of Echocardiography, the Inter-American Society of Echocardiography, and the Brazilian. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17(6):589–590. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Généreux P., Piazza N., Alu M.C., et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(21):2717–2746. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgartner H., Falk V., Bax J.J., et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(36):2739–2791. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kappetein A.P., Head S.J., Genereux P., et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145(1):6–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishizu K., Shirai S., Isotani A., et al. Long-term prognostic value of the society of thoracic surgery risk score in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (from the OCEAN-TAVI registry) Am J Cardiol. 2021;149:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludman P.F., Moat N., De Belder M.A., et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the United Kingdom. Circulation. 2015;131(13):1181–1190. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little S.H., Oh J.K., Gillam L., et al. Self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve replacement versus surgical valve replacement in patients at high risk for surgery: a study of echocardiographic change and risk prediction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(6) doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thyregod H.G., Steinbruchel D.A., Ihlemann N., et al. No clinical effect of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate- and low-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at mid-term follow-up: an analysis from the NOTION trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;50(4):721–728. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leone P.P., Regazzoli D., Pagnesi M., et al. Predictors and clinical impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch after self-expandable TAVR in small annuli. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(11):1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guimarães L., Voisine P., Mohammadi S., et al. Valve hemodynamics following transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with small aortic annulus. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(6):956–963. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okuno T., Khan F., Asami M., et al. Prosthesis-patient mismatch following transcatheter aortic valve replacement with supra-annular and intra-annular prostheses. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(21):2173–2182. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomii D., Okuno T., Heg D., et al. Long-term outcomes of measured and predicted prosthesis-patient mismatch following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. EuroIntervention. 2023;19(9):746–756. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-23-00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H., Ahn J.M., Kang D.Y., et al. Racial differences in the incidence and impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(24):2670–2681. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyasaka M., Tada N., Taguri M., et al. Incidence and predictors of prosthesis–patient mismatch after TAVI using SAPIEN 3 in Asian: differences between the newer and older balloon-expandable valve. Open Heart. 2021;8(1) doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaneko T., Vemulapalli S., Kohsaka S., et al. Practice patterns and outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the United States and Japan: a report from joint data harmonization initiative of STS/ACC TVT and J-TVT. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(6) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ewe S.H., Muratori M., Delgado V., et al. Hemodynamic and clinical impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(18):1910–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pibarot P., Weissman N.J., Stewart W.J., et al. Incidence and sequelae of prosthesis-patient mismatch in transcatheter versus surgical valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: a PARTNER trial cohort--a analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(13):1323–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbas A.E., Ternacle J., Pibarot P., et al. Impact of flow on prosthesis-patient mismatch following transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(8) doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.012364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schofer N., Deuschl F., Rubsamen N., et al. Prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: prevalence and prognostic impact with respect to baseline left ventricular function. EuroIntervention. 2019;14(16):1648–1655. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-18-00827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrmann H.C., Mehran R., Blackman D.J., et al. Self-expanding or balloon-expandable TAVR in patients with a small aortic annulus. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(21):1959–1971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2312573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sa M.P., Jacquemyn X., Van den Eynde J., et al. Impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: meta-analysis of Kaplan-Meier-derived individual patient data. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;16(3):298–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zorn G.L., 3rd, Little S.H., Tadros P., et al. Prosthesis-patient mismatch in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: a randomized trial of a self-expanding prosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(4):1014–1022, 1023.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs2015.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.